I

We wear a badge stating unequivocally that we ARE gay, and proud of it… WE INTEND TO BE NOTICED. WE WILL ‘FLAUNT’ OURSELVES.Footnote 1

The Gay Liberation Front (GLF) was one of Britain’s most important twentieth-century gay communities, existing as a focal point for many gay people and informing gay culture during and after its existence. This article uses the purple GLF badge to analyse the movement as a whole, including its principles, community, and long-term impact on the gay movement and its members. This was the most popular GLF badge that was produced and frequently appears in archives holding material on GLF. Despite this, it has received limited scholarly attention. The most significant contribution to the history of the GLF badge is in an appendix in Lisa Power’s detailed account of GLF. Power notes the badge’s emergence from Philadelphia’s GLF, its iconographical features, and how it ‘has subsequently become the most enduring symbol of GLF to later gay activists’.Footnote 2 Elsewhere, Jeffrey Weeks has tied the badge to coming out and ‘asserting your homosexuality’, but does not offer any concrete examples of this.Footnote 3 Brief references to the badge are also present in published collections of oral histories with GLF members.Footnote 4 Clearly significant, but as yet understudied, this article seeks to shed light on the GLF badge and by doing so brings a new understanding of GLF.

Power’s extensive book on GLF gives narrative and conceptual frameworks that have been fundamental to subsequent scholarship. The British GLF first met in autumn 1970 at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), after Aubrey Walter’s and Bob Mellors’s experiences in the American GLF, with nineteen people attending the first meeting.Footnote 5 The American origins of the badge were noted by some of our narrators and corroborated by examples of the same iconography being used on ephemera and badges produced by the American GLF.Footnote 6 This reveals the transnational dimension to the material culture and ideas of GLF. Some scholars have noted the political, social, and cultural context of the 1960s and 1970s in which the British GLF existed. Of particular note was counter-culture, adjacent national and international liberation struggles, and student activism.Footnote 7 By studying the badge, we can understand the long 1960s as an era of outward expression and social protest, as badges were tools of social communication which displayed identities and political stances. GLF’s work was often a result of the national context of Britain, such as when in 1971 GLF marched with trade unions against the Conservative government’s controversial Industrial Relations Bill.Footnote 8 At the same time, GLF in Britain was a product of its transnational connections with the US GLF. As such, whilst the badge was worn within the cultural and political context of 1970s Britain, it was also worn as part of a transnational culture of badge-wearing of the left.

After the establishment of GLF, the group grew and organized events such as gay days, zaps, think-ins, and discos.Footnote 9 For many members, GLF was an all-encompassing part of their lives and identity. One narrator, Nettie Pollard, summarized this by saying that ‘you could be doing something GLF just about every day of the week and I absolutely loved it’.Footnote 10 Gay liberation was a turning point for the gay movement, with its novel liberation politics and non-traditional forms of action.Footnote 11 Part of the distinctiveness of GLF was its rejection of the pre-existing gay scene as GLF sought to forge a new, distinct, and more radically inclined gay community against the contemporaneous gay organizations that focused on reform as well as the gay scene’s secrecy, commercialism, and accommodationism.Footnote 12 Indeed, typifying the sentiments of other narrators, Andrew Lumsden said that after joining GLF he found others like himself who ‘didn’t like the gay world [he] found in London…They didn’t like this world in which the pubs that gays had available to go to…were run by commercial interests, which often were entirely straight interests.'Footnote 13

Power has outlined the tensions and divisions that arose in GLF and led to its fracturing and effective dissolution by 1973.Footnote 14 Other scholars have also highlighted GLF’s diversity of views and tied it to the internal splits, schisms, and impasses that contributed to its fracturing.Footnote 15 GLF’s divisions and eventual disintegration reveals, as Lucy Robinson writes, that GLF was a ‘collective of individual identities’, which highlights the subjectivity of GLF members instead of seeing GLF as a monolith.Footnote 16 This article builds on this emphasis of the subjectivity and individuality in GLF by viewing badge-wearing as an individual choice.

We explore the experience and significance of wearing the GLF badge as a means of coming out and community building. The ethos of GLF lived on through the continued use of its badge and other badges that came in its wake. In doing so, the article reflects more broadly on the role that badges can and have played as a means of social communication within the gay community. Much of the foundational scholarship on GLF was conducted by GLF members or people involved in the gay rights movement shortly after the collapse of GLF.Footnote 17 By conducting this study several decades after the fracturing of GLF, the timeline of GLF can be extended to the present day and its long-term legacy examined, rather than limiting its history to between 1970 and 1973.

The GLF badge shows that the ideas and activities of GLF did not end in 1973. Based on the traditional 1970 to 1973 timeline of GLF, scholars have concluded that GLF was ‘short lived’.Footnote 18 However, there are some references to the post-1973 legacy of GLF and several historians have alluded to the organizations that came out of GLF and its longer-term impact on the gay movement.Footnote 19 The fracturing of GLF was noted by our narrators, twice through celestial imagery. Nettie reflected that GLF ‘was like a shooting star, you know. But a shooting star does go out.’Footnote 20 Tom Robinson described GLF’s break up as ‘like the Big Bang’. His imagery highlights the organizations, groups, and activities that emerged in the wake of GLF, which he called ‘fragments’ and ‘asteroid[s]’.Footnote 21 Angela Mason commented that although the central GLF ‘faded away’, local GLFs ‘did remain quite strong’.Footnote 22 South London GLF was the strongest vestige of London GLF after 1973, existing until 1983.Footnote 23 The involvement of GLF members in gay, feminist, and political groups and activities did not end with the splintering of GLF. Rather, GLF acted as a stepping stone to other work following 1973. Or, as Nettie remarked: ‘[GLF] didn’t really disappear, it’s just, it started doing other things’.Footnote 24

To explore the GLF badge and its significance, this article uses both oral histories and archival research. We interviewed eighteen members of GLF, of which sixteen were part of GLF in London and two in the United States.Footnote 25 Our first three narrators were contacted with the help of the LSE Library and Archives.Footnote 26 After this, both word-of-mouth from these initial narrators, who remain in touch with other GLF members, and online searches brought us into contact with our other narrators.Footnote 27 This article uses the term narrator to describe the people interviewed, as narrator emphasizes the agency of those interviewed.Footnote 28 It also reveals the narratives and emotions that emerge from our oral histories. Similarly, in line with our narrators, usage in GLF, and for consistency throughout the article, we use gay to mean, as Andrew Lumsden remarked, ‘the whole of what LGBTQI+ is supposed to express now’.Footnote 29 Alongside oral histories, we consulted thousands of items held by the Bishopsgate Institute and the Hall-Carpenter Archives (HCA) at the LSE Library and Archives. In these archives, the badge exists alongside other items of ephemera produced by GLF, such as weekly events diaries, photographs, and the newspaper Come Together, all of which this article uses.Footnote 30 This mixed-method of archival research and oral histories produces a holistic understanding of the GLF badge, as we elicit a plurality of narratives and perspectives on badge-wearing.

Oral history has frequently been used to study gay lives and a range of GLF scholarship uses this method. Power’s main source base is extensive oral histories with GLF members and Matt Cook, Hugh David, and Martha Robinson Rhodes also employ oral histories with GLF members to help tell GLF’s history.Footnote 31 Much of the interest in using oral history to capture the history of GLF was prompted by the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the deaths of GLF members.Footnote 32 Outside of studies on GLF, oral history is a common methodology for writing about gay lives.Footnote 33

This article also adds to work that explores or references the material culture of gay people and groups.Footnote 34 Daniel Fountain’s edited collection Crafted with pride: queer craft and activism in contemporary Britain offers several case-studies of material culture being used in British gay groups, underlining the importance of material culture for gay communities.Footnote 35 Badges from other gay movements have also been noted in passing by Stephan L. Cohen and Diarmaid Kelliher in the US and Britain, respectively.Footnote 36 Moreover, Andy Campbell combines oral history and archival research to examine Viola Johnson’s pin sash in the United States and within this focuses on a specific badge.Footnote 37 This article builds on this methodology but uses multiple narrators, which allows for the subjectivities of badge-wearing to be shown. Oral history captures the embodied experience of badge-wearing as it illuminates the lives of the badge through the voices, laughter, tears, and facial expressions of those who wore it. This methodology produces a more complex understanding of the meanings that different people have assigned and continue to assign to the badge. Although the badges themselves cannot speak, as Roz Kaveney, one of our narrators, noted, ‘they’re an heuristic for finding out what happened, they’re not the thing [GLF] itself’.Footnote 38

In considering the badge after 1973, this article engages with Campbell’s work in a second respect: how badges can become a ‘mnemonic’ and, as badge collections, a ‘mobile library/archive’ with time.Footnote 39 The GLF badge demonstrates that badges can acquire new significance as tools to evoke history and memory, especially when collected and cherished by those who wore them. Instead of static objects, badges evolve once they are removed from their original context. By examining the material culture of social movements in their afterlives, this article shows how social movements affect people in personal and political ways in the long term, thus opening new avenues for further study.

This is the first dedicated study of the GLF badge and its long-term significance. To do so, this article is structured around three main sections. It begins by analysing the badge’s origins and semiotics. We then explore how and why the badge was worn between 1970 and 1973, arguing that it was a means for GLF members to come out and build GLF as a community. The final section examines the badge following the fracturing of GLF, when the badge maintained its original purposes whilst also acquiring a new significance. In the wake of GLF, it sustained the memory and zeitgeist of GLF. After 1973, the gay community saw a proliferation of other gay badges and the emergence of a tradition of badge-wearing. Through the analysis that follows, badges are shown to be not just a piece of wearable ephemera, but powerful tools of social communication, asserters of identity, and evokers of memory.

II

The iconography of the badge visually displays GLF’s principles of fighting internal and external oppression (see Figure 1). The variety of interpretations of the badge’s imagery offered by our narrators is indicative of the subjective nature of being a part of GLF, as GLF members wore the badge for reasons that aligned with their personal interpretation of this iconography. One section of issue 12 of Come Together gives readers the opportunity to ‘write your own’ badge and summarizes this idea: ‘Well of course a symbol can mean anything one wants it to mean.’Footnote 40

Figure 1. GLF badge. LSE, HCA/GLF/17. Reproduced with kind permission from the LSE Library and Archives.

The dominant feature of the badge, the fist, was commonly attributed to the Black Power movement.Footnote 41 The overlapping signs of Mars and Venus signal same sex attraction. GLF used both the fist and signs of Mars and Venus in other ephemera, like posters, leaflets, and Come Together, akin to a logo.Footnote 42 Our narrators provided different interpretations of the significance of the badge being purple. Angela Mason associated purple as a gay colour and Mair Twissell Davis saw purple as a general GLF colour.Footnote 43 Philip Rescorla also linked purple and violet with lesbians, suggesting that it was possibly a woman in America who designed the badge.Footnote 44 Martin Edwardes provided a different interpretation, linking purple to the Roman imperial colour, and noted that for him the purple was important as it was neither revolutionary red nor conservative blue.Footnote 45 Our narrators explained the all capital, sans-serif ‘Gay Liberation Front’ that arches over the top of the badge in different ways. For example, Martin interpreted this choice of typeface to mean ‘We’re not interested in the fripperies, you know, we’re interested in direct action.’Footnote 46 Using the word ‘gay’ on the badge was also significant as gay people chose it for themselves, rather than using the then derogatory ‘queer’ and ‘homosexual’. Michael Parkes said that ‘gay is a positive, bright, sunny word’ whilst ‘Queer…encapsulated all that filth, all that oppression, all that guilt, all that sin, all those millennia of bigotry and danger and, and spitting and beatings up and illegality and inhumanity.’Footnote 47

For many GLF members, the badge existed within the general milieu of GLF and the origin and production of the badge was not questioned. As Angela remarked: ‘[the badge] was just sort of there’.Footnote 48 Much of the specific practicalities of how and where the badges were produced remain unknown. However, as Andrew noted, in GLF ‘there were people who knew how to do everything, absolutely everything’.Footnote 49 Therefore, it seems likely that there was someone in GLF who made them, or that someone in GLF knew a company where they could be cheaply produced.Footnote 50 In this way, the production of the badge shows the diversity of individuals in GLF who had different skills and connections. There was also a financial element to the badges, being sold for five or ten pence.Footnote 51 Since the badges were cheap, they were accessible to buy and wear and the money raised from them helped to fund GLF expenses, as shown by financial reports. However, at times producing the badges contributed to GLF debts.Footnote 52 This demonstrates GLF’s grassroots ethos in terms of how it financially supported itself.

The badges are also interesting as material, physical objects. With time, no two badges are alike. Erosion of the metal and scratches remind us that these badges were touched, felt, and worn by people. As the following two sections will demonstrate, the badges were, and are not, static objects. Instead, they were important to the individuals who decided to pin them to their clothes and assign meaning to them.

III

Coming out was central to the ethos of GLF. Weeks puts forward a trinity of stages of coming out in the context of GLF. Individuals came out to themselves, other ‘homosexuals’ (‘coming together’), and the wider public; coming out was done on both a personal and collective level.Footnote 53 The importance of coming out and community in GLF often appears in archival material. In 1972, the LSE-GLF Collective wrote that ‘We emphasised ‘Coming Out’ – openly admitting our homosexuality, thereby committing ourselves to honesty to our true selves.’Footnote 54 Our narrators also spoke of their experiences of coming out and how GLF empowered them to do so. Angela recalled speaking at her first GLF meeting and being asked to identify whether she was gay or straight: ‘I thought ohh God, I finally have to come out…and that, that was a sort of a very liberating moment for me.'Footnote 55 Coming out as tied to community can be seen in the August to September 1973 GLF diary: ‘Only when we are really strong in ourselves can we show our solidarity with others.’Footnote 56 Recognizing the centrality of coming out and community in GLF frames the badge’s roles in these two processes.

Communal badge-wearing was common, which displayed the GLF community to others and reinforced a sense of community amongst GLF members. This community was important given the homophobia experienced by gay people. Indeed, Andrew recalled how before GLF ‘lying was a way of life’ whilst Michael P. noted how according to society of the 1960s ‘[he] was a criminal…Certifiably insane, and looking at electric shock treatments, if [he] wanted to be cured.’Footnote 57 Badges were worn at demonstrations, as Philip recalled, ‘if we went on a march, everyone would bring their badges out and wear them’.Footnote 58 GLF members also wore badges to sell issue 3 of Come Together and at times badges were worn in court in support of GLF members on trial.Footnote 59 On a June 1971 GLF gay day in Victoria Park, GLF members held a kiss-in whilst wearing the badge, as police and members of the public watched on.Footnote 60 At this gay day and these other examples, wearing the badge outwardly expressed one’s allegiance to GLF.

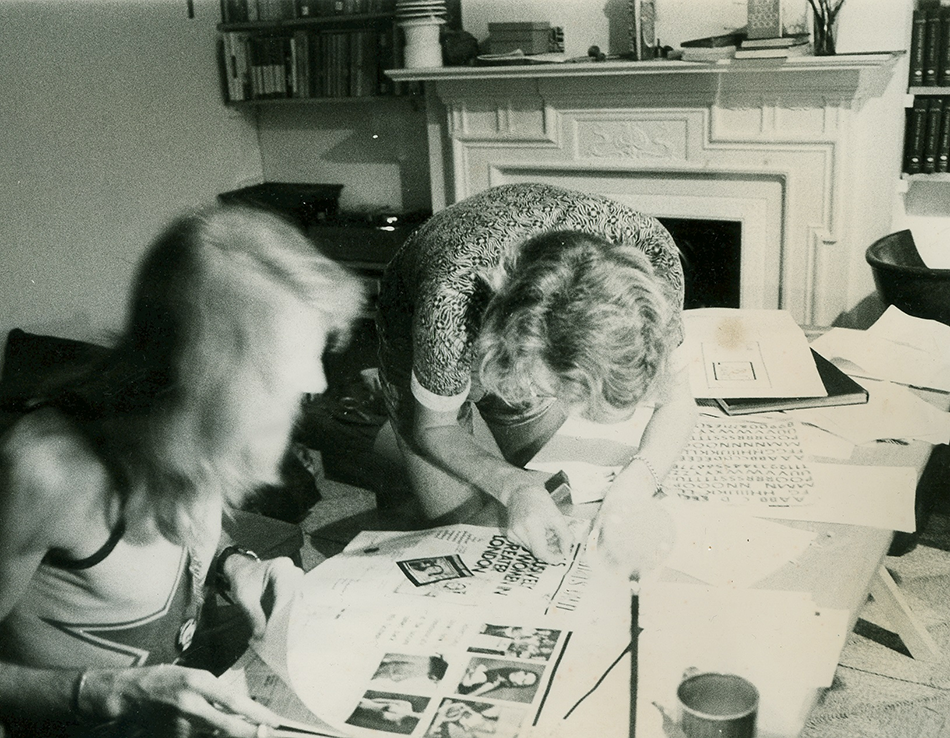

The badge also built, in Andrew’s words, a ‘sense of collegiality with the people that you’re doing a particular campaign with’.Footnote 61 Tom recalled, with tears in his eyes, approaching the door of his first GLF disco with apprehension: ‘as I got closer to this gang of youths, I noticed they were all wearing Gay Liberation Front badges. It’s like my people! This is my people! It’s just, so liberating.’Footnote 62 In this case, the GLF badge communicated to Tom that the youths were part of GLF, making him feel safe, protected, and part of the gay community. In private, badge-wearing still signalled and built a communal GLF identity, such as when a GLF member wore the badge during the production of the first issue of Come Together in Aubrey Walter’s flat (see Figure 2).Footnote 63 Thus, both private and public badge-wearing built community within GLF.

Figure 2. ‘Producing 1st Come Together. Aubrey Walters flat’, 1970. LSE, HCA/CHESTERMAN/6. Reproduced with kind permission from the LSE Library and Archives.

The GLF badge captured the GLF ethos of coming out to oneself. The GLF manifesto emphasized freeing oneself from ‘self-oppression…when the gay person has adopted and internalised straight people’s definition of what is good and bad’.Footnote 64 GLF member Alan Wakeman wrote on the importance of badge-wearing: ‘If you manage to come out completely, and that means be able to wear your badge in any and every situation, you will find that the mere wearing of it will have changed your consciousness.’Footnote 65 Wakeman highlights the connection between individual consciousness, coming out, and wearing a badge. Wearing a badge enabled one to come out and feel comfortable about their sexuality, which in turn freed them from self-oppression. Nettie echoed this view, describing it as ‘a liberation badge, not a rights badge’.Footnote 66 A June 1971 gathering of different gay-related groups at a National Think-In in Leeds also sheds light on badge-wearing as a means of freeing oneself from internal oppression. In response to the more moderate Campaign for Homosexual Equality, GLF cited one reason for wearing a badge as ‘an internal one. If you don’t think that you are being oppressed, ask yourself why you don’t wear a badge. If your only answer is that it is politically ineffective, I suggest you are lying to yourself. No, you are embarrassed and maybe just a little bit afraid.’Footnote 67 In issue 12 of Come Together, John also highlighted how wearing a badge took inner courage by noting the difficulty for some to ‘[wear] the G.L.F. badge in places where we didn’t have the guts to wear it before’.Footnote 68 Moreover, Martin Edwardes wore his GLF badge underneath his coat during the winter season, out of public view.Footnote 69 These examples show individuals wearing the badge for themselves, rather than others, to affirm their personal liberation and identity.

Alongside self-exploration, coming out was also an important outward action. A sheet with ‘cut-out-badges’ highlights the connection between badge-wearing as an inward and outward process, telling the reader to wear a badge and ‘watch their reactions [and] watch your reactions’.Footnote 70 The pamphlet ‘Homosexuals are oppressed’ also demonstrates the connection between coming out inwardly and externally: ‘some concentrate on personal liberation by looking inwards, seeing this as a necessary preliminary to action directed outwards’.Footnote 71 Mike wrote in issue 13 of Come Together how coming out meant being open to other people: ‘Coming out is not just one action or statement. It is different in every situation we are in: work, friends, family, society in general.’ Mike went on to link coming out to badge-wearing: ‘The first and easiest step was coming out to society in general. Wearing a badge, kissing and openly relating to other men.’Footnote 72 Alvin, writing in a Camden GLF newssheet, provided an example of the way in which badges could be used to come out: ‘Telling my flat mates was easier than I thought. They didn’t believe me so I rushed to a suitcase, took out my hidden hoard of GLF material and a badge and threw it at their feet. They were shocked but our relationship is better – I relate more frankly to them.’Footnote 73 Alvin’s anecdote provides an example of the GLF theory that linked overcoming internal oppression to coming out to others.

For many of our narrators, the badge was something they regularly wore in almost all contexts of their life and thus coming out through the badge was a constant process. For Mair, ‘It was a badge of honour…I wore it as part of me.’Footnote 74 John Lloyd ‘wouldn’t go out the door without [the badge]…it was an absolute must’.Footnote 75 Michael James noted that wearing the badge was in some cases a more passive act: ‘It wasn’t the case of putting it on to go somewhere. You put it on your jacket and you forgot about it.’Footnote 76 Similarly, Peter Tatchell remembered: ‘I used to wear the GLF badge pretty much every day. Whether I was going to work, or socializing, or speaking at events.’Footnote 77 The everyday wearing of the badge shows its power as a constant identifier of one’s identity. In this way, the badge demonstrates the links between the personal and political as a principle of GLF in that badge-wearing communicated GLF members’ sexuality in ordinary environments, not just overtly political ones like demonstrations.Footnote 78

Outwardly coming out was also done to fight the dominant assumptions about gay people and normalize their existence. As a GLF leaflet on the Industrial Relations Bill identified: ‘Gay people are coming out against the stereotyped images society gives us.’Footnote 79 Peter highlighted this idea as he said coming out was ‘about informing and educating straight people, to show that we are everywhere’.Footnote 80 The badge was a means to do so. Stuart Feather spoke of his first impressions of GLF: ‘you picked up quickly the fact that, you know, the whole thing was about coming out and [GLF’s] idea was then wearing a badge…[People] think they don’t know any homosexuals, when in fact they do.’Footnote 81 On some occasions, wearing the badge provoked conversation with members of the public and provided the wearer an opportunity to talk about GLF and assert their sexuality.Footnote 82 During the 1971 Leeds Think-In, the other reason GLF cited for wearing a badge was to make the straight population aware of the existence of gay people: ‘the majority of the population will say that they don’t know any homosexuals…Straight society is not forced to recognise our existence.’Footnote 83 The rhetoric of ‘forced’ demonstrates GLF’s use of the badge in their direct action approach to combating oppression. However, in signalling their sexuality to the outside world, wearing a badge was not a wholly positive experience for GLF members. At times, people wearing badges were identified and targeted for being gay. For example, in November 1971 on Remembrance Sunday, ‘around 15 members’ of GLF were told ‘by the Thought Police’ that they could not lay a wreath on the Cenotaph whilst wearing the GLF badge ‘In Memory of the countless thousands of homosexuals branded with the Pink Triangle of homosexuality’ who were murdered by the Nazis.Footnote 84 Later, in 1972 the Chepstow pub in Notting Hill refused to serve anyone wearing the GLF badge.Footnote 85 However, some of our narrators noted that the impact of the badge on the public was limited.Footnote 86 In Nettie’s words, ‘I think a lot of people did not know what Gay Liberation Front meant because they didn’t know what gay meant.’Footnote 87 This further reinforces the idea that badge-wearing was important for self-assertion regardless of whether anyone else was watching.

Although much has been said about individuals wearing the GLF badge, Shân Veillard-Thomas and Roz Kaveney, two of our narrators, did not wear the badge.Footnote 88 Roz said she was probably in the minority of people by not wearing a badge and chose not to wear one as ‘[she had] never been a badge person…[badges] mess up your clothes. I mean I don’t want to go around tearing my jackets, shirts, and t-shirts, because sticking holes in things is not good for the, your clothes.’Footnote 89 Although Michael P. often wore the badge, ‘[he] didn’t wear the Gay Liberation badge in places where [he] didn’t feel safe to do so’.Footnote 90 Nettie also recalled that when she and her girlfriend visited her girlfriend’s mother in hospital they both took off their GLF badges out of respect for her mother.Footnote 91 Michael J. also remembered someone who ‘wouldn’t wear the badge when he went to meet his, meet his mother’.Footnote 92 Those who chose not to wear badges, or remember situations in which they did not wear badges, demonstrate how badge-wearing was not a one-size-fits-all solution to asserting one’s identity but a personal choice; badge-wearing was navigated through different environments and circumstances. These stories underline the individuals behind GLF, their subjective views, decisions, and personal assertion of identity. It also emphasizes how the badge was used to come out as some chose not to wear it so as to conceal their sexuality.

The badge as a means to build community and come out were not mutually exclusive processes. Angela noted the connection between coming out and community building: ‘it was a personal, individual liberation achieved in collective context. And that’s what gave it strength because you didn’t just do it on your own.’ Angela linked this idea to badges: ‘I think the badge…performed a sort of reinforcement of the, well, I’d describe it as solidarity of GLF.’Footnote 93 A 1972 article on the LSE-GLF in the LSE student newspaper, The Beaver, advertising the LSE-GLF, demonstrates the practical community building that could be done by coming out and wearing a badge: ‘We can be contacted in a variety of ways. See the badge and stop anyone of us.’Footnote 94 Even when not physically in a group with other GLF members, people were able to draw on the GLF community when wearing a badge. Julia, writing in Come Together from ‘a small town (200,000), just north of Birmingham’, wore the GLF badge as part of her coming out as ‘trans-sexual’: ‘Wearing the GLF badge is like a shield to me and it feels as if it is protecting me.’Footnote 95 Tom echoed this sentiment: ‘the combination of the badge and the Gay News made me go it’s not a big deal coming out, it’s so simple. And so effective. And so low risk. It’s worth doing.’Footnote 96

Overall, wearing the GLF badge was an inward and outward assertion of identity in the context of an often pernicious environment for gay people in the early 1970s. Wearing the badge likewise affiliated one with and built GLF as a gay community, with its distinct principles and approach to the gay movement.

IV

After 1973 and the fracturing of GLF, the original GLF badge continued to be sold and worn. The wearing of the purple badge also precipitated a longer tradition of gay badge-wearing within the gay community as new badges were designed and worn (see Figure 3). Our narrators recalled how they continued to wear their GLF badge for a number of years after the fracturing of GLF. Peter said that ‘Even though GLF was effectively over in 1974, I kept on wearing the GLF badge well into the late 1970s.’ Asked why, he said that ‘It was the best LGBT+ badge [laughs], and I wanted to keep alive the memory of the Gay Liberation Front.’Footnote 97 Nettie echoed a similar affinity to the purple GLF badge in the years following 1973, telling us that she ‘wore a badge at work for the next like, sort of eighteen years or something’ and that it was always the purple GLF badge as ‘the Gay Liberation Front one was the best I think, and the original’. For Nettie, the badge continued to function as a means to come out to other people, as by wearing the badge ‘anyone that came into the office knew [that she was gay]’.Footnote 98 Stuart determined that he stopped wearing the badge in 1979, although he would wear it at Pride events after that.Footnote 99 Michael J., who had moved to Amsterdam in the years following GLF, continued to wear the badge there, saying that ‘[the badge] was on my clothes…if it’s on my clothes, it would have stayed on my clothes’.Footnote 100 However, the continued wearing of the GLF badge was not universal. Michael P. estimated that he stopped wearing it when he went to work abroad in 1974, whilst Angela stopped wearing the badge ‘Probably when GLF sort of faded away.’Footnote 101 In the same way that not all GLF members wore the GLF badge prior to 1973, wearing the GLF badge was still an individual act that one could choose to do or not.

Figure 3. Queer Liberation Front badge designed by Martin Edwardes. Reproduced with kind permission from Martin Edwardes.

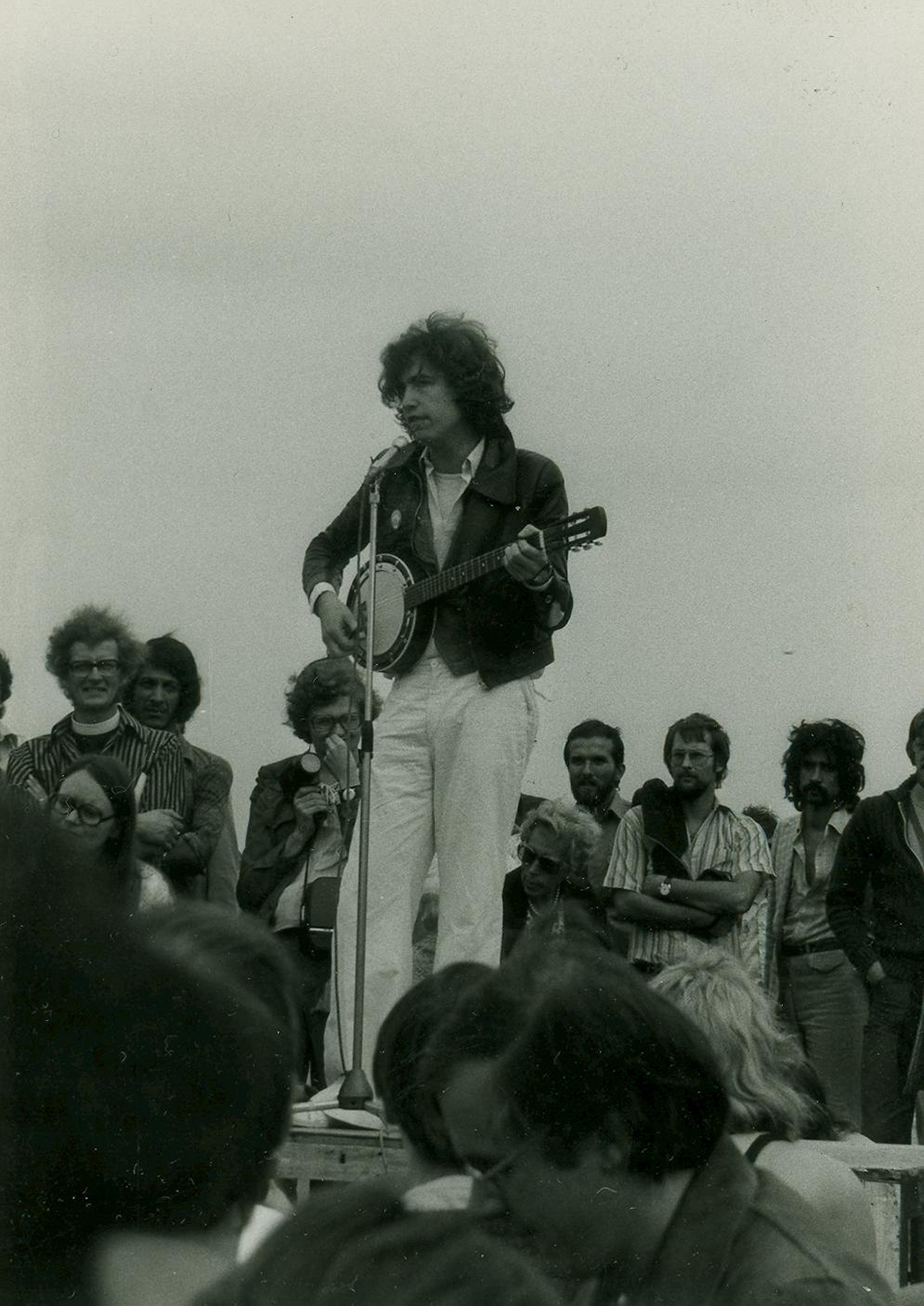

The original GLF badge also frequently appears in archival material in the decades after 1973 and was increasingly referenced alongside other, new gay badges. Just as GLF was a stepping stone to subsequent gay groups and activities, the original GLF badge set a precedent for a proliferation of gay badges. The purple GLF badge was sold by both the GLF’s remaining administration, the Office Collective, and then Gay Switchboard, the latter seeing itself as a ‘clearing house for GLF’.Footnote 102 Other gay badges were also sold by these groups.Footnote 103 In 1975, Gay Switchboard sold the GLF badge and badges saying ‘Glad to be Gay’, ‘Avenge Oscar Wilde’, ‘I am a Homosexual Too’, and ‘Come Out’.Footnote 104 Photographs from the 1976 London Gay Pride March show individuals still wearing the GLF badge, including Tom Robinson singing with a banjo (see Figure 4).Footnote 105

Figure 4. Tom Robinson at 1976 London Gay Pride. LSE, HCA/CHESTERMAN/42/15. Reproduced with kind permission from the LSE Library and Archives.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, South London GLF (SLGLF) was a core for the proliferation of gay badges. Lists of badges available to be bought from SLGLF included the original purple GLF badge, alongside other, newer badges such as ‘Every woman can be a lesbian’.Footnote 106 SLGLF also designed gay badges, like the badges for the 1977 and 1978 Gay Prides, and a ‘Gays Against Fascism’ badge.Footnote 107 Gay badges also appear in newspaper articles, in both photographs and text, concerning SLGLF and the wider post-1973 gay liberation movement’s activities.Footnote 108 Moreover, the Gay Liberation Information Service, working from the old GLF office at 5 Caledonian Road, advertised a variety of badges available into the 1980s, including the original purple GLF badge.Footnote 109

This proliferation of gay badges which derived from the GLF badge was also noted by our narrators. John told us that ‘Gay Liberation exploded and part of that was a badge, Gay Liberation Front. And thereafter, other badges came into being’, in particular from SLGLF.Footnote 110 Ian Townson, who was also part of SLGLF, could recall a number of the badges that SLGLF produced and which he wore, like ‘How dare you presume I’m heterosexual’.Footnote 111 Tom told us that the design for the logo of his band, Tom Robinson Band, which was used on badges and stickers was partly inspired by the GLF’s badge design, namely the central fist and arching letters.Footnote 112 Therefore, in the post-1973 gay movement, badges became an important feature and tool in the gay community. This is a legacy of the wearing of the original GLF badge which initiated this tradition of gay badge-wearing. Moreover, as the words on the newer badges suggest, they asserted one’s sexuality as the original GLF badge had done and so acted as a continued means for people to come out. In this way, the continued wearing of the GLF badge and proliferation of other gay badges was part of the energy and ethos of GLF living on despite its formal fracturing.

In the 1990s and 2000s, the GLF badge continued to be worn by former members of GLF as the time of GLF transitioned into memory and history for those who were part of it. It was then that the badge took on a new role and meaning, becoming a tool to evoke the memory of GLF. Most prominently, the GLF badge was worn at Pride (including its subsequent iterations) and at GLF anniversary events. For example, in 1995, for the twenty-fifth anniversary of the foundation of GLF in Britain, former GLF members recreated the first gay demonstration in Britain in Highbury Fields, London. This was helped by the wearing of GLF badges, with David Pollard writing in Thud newspaper that ‘We did…march behind a GLF banner and wore our Gay Liberation badges with pride’, whilst t-shirts with the GLF badge design on were also worn.Footnote 113 At Gay Pride that year in Victoria Park, London, these t-shirts were again worn by former GLF members, with some also wearing their GLF badges.Footnote 114 For that Gay Pride, John Chesterman produced a badge with ‘25 YEARS OUT’ in the centre and ‘GAY LIBERATION FRONT 1970 1995’ around the edge as part of the twenty-fifth anniversary of GLF.Footnote 115 This captures the importance of badges in the gay movement, in this case to evoke a shared gay heritage. In 2010, for the fortieth anniversary of GLF the LSE held an event which brought together former GLF members at which some wore their GLF badge, including Andrew Lumsden and Julian Hows.Footnote 116 More recently, in 2020 for the fiftieth anniversary of GLF and in 2022 for the fiftieth anniversary of Pride in Britain, some former GLF members put on their GLF badges during these marches, as well as producing a banner with the image of the GLF badge on at the 2020 event.Footnote 117 These examples demonstrate the importance of the GLF badge as a symbol of GLF as a community and a piece of history. The badges were a means to come out whilst they also came to evoke the memory of GLF.

This is also true for examples of the continued wearing of the GLF badge and its subsequent badges in less public and more individual instances. Julian continued to frequently wear the GLF badge in the 1990s. For example, whilst dressed as Oscar Wilde, Julian wore a reproduction GLF badge for a procession marking the centenary anniversary of Wilde’s trial.Footnote 118 After showing Julian this photograph during our interview, he recalled that the GLF badge with a white border in the photograph was possibly made for an anniversary event for GLF at Duckie, a gay club, during which an ‘admission by badge’ policy was implemented.Footnote 119 Martin Corbett, a GLF member who passed away in 1996, had a hat adorned with gay badges, including the purple GLF badge.Footnote 120 This serves as a visual representation of the proliferation of badges and tradition of badge-wearing which emanated from the GLF badge.

Moving further into the long-term wearing of the GLF badge and other badges, at least from the 2000s Julian occasionally wore the ‘How dare you presume I’m heterosexual?’ badge to promote a conversation, and at other times the original GLF badge. He explained that he wore the latter at formal events if decorations were required as a means to communicate that he is ‘somebody who believes in the principle of the GLF’ and say ‘Don’t think you’re doing this for the first time darling. We’ve been here before.’Footnote 121 Here, Julian uses the GLF badge as an emblem of his time in GLF and to demonstrate his allegiance to its history and memory. Moving closer to today, Martin Edwardes recalled that he stopped wearing badges for a time, but then began to wear them again between 2005 and 2012 when he was teaching, whilst Philip told us that he had ‘started wearing them again recently because of all the anniversaries’. Philip went on to say that he wore the GLF badge after its fracturing because ‘[GLF is] more than just the, an organization. It’s a principle. It’s an idea’ and because he is ‘proud to have been part of it, I guess, there’s also a pride in wearing it’.Footnote 122 Nettie said that if she was photographed for a feature on her, she had ‘always made sure [she] had a GLF badge on’.Footnote 123 Moreover, during our archival research at Bishopsgate, we met both Julian and Ian on separate occasions. Julian was wearing his GLF badge whilst Ian was taking out some badges from his collection of badges held at Bishopsgate, including ‘Glad to be Gay’, ‘Gays Against Fascism’, and ‘Keep your filthy laws off my body’ to wear in public and give the last badge to a friend to wear.Footnote 124 Later, when we met Ian for our interview, he was wearing his ‘Glad to be Gay’ badge alongside a badge in support of Palestine. The GLF badge and the badges that followed have continued to be used for their original purpose as a display of one’s sexuality. However, their wearers have increasingly accorded greater retrospective importance on these badges to show that they were part of GLF as a period of gay history and to support its memory.

Both the personal collections of former GLF members and institutional collections attest to the importance of badges in the history of the gay movement. Most of our narrators had a personal collection of badges, varying in extent. For example, Andrew had a small collection, including an original GLF badge that Mary McIntosh had given him and which he kept in a small, felt-lined box.Footnote 125 Martin’s collection of badges was the most extensive collection of our narrators and he called the GLF badges within this collection his ‘crown jewels’ (see Figure 5). Asked why they are so valuable to him, he said that ‘they represent not just a part of my life, they are kind of a part of me’. Martin has also made a recreation of the GLF badge as a ‘Queer Liberation Front’ badge (see Figure 3), which he has given out at Trans Pride and other events.Footnote 126 Some narrators no longer have their GLF badges, including John Lloyd and Mair Twissell Davis. John guessed that he had lost them during a house move and said that he had not taken greater care in keeping them as ‘[he] didn’t know [GLF] were making history in the way we were’.Footnote 127 Mair told us that she wanted to find a reproduction GLF badge as ‘It’s something really nice, I think. A nice memory.’Footnote 128

Figure 5. A selection of Martin Edwardes’s badges, with his ‘crown jewels’ at the bottom centre. Reproduced with kind permission from Martin Edwardes.

GLF badges and other gay badges also feature prominently in archives and museums. As a piece or memento of gay history, older badges, like the purple GLF badge, are a means to connect the present gay community with their past and heritage as the gay badge-wearing tradition continues in the present. Both the HCA and Bishopsgate hold extensive gay badge collections. For example, Ian’s collection of badges held at Bishopsgate discussed above holds over a hundred badges alone, which he amassed by asking his friends, some of whom were GLF members, to donate to the collection.Footnote 129 The HCA likewise holds numerous gay badges and is an important site for the gay community as it preserves their past. Indeed, writing in the 1990s John Chesterman reflected on his journal from 1973 that ‘the evidence of all this activity, the ephemera of our long ago revolution, is now in the Hall-Carpenter Archives at the LSE, where it belongs, slowly turning into history’.Footnote 130 GLF members have contributed much to the collections of both the HCA and Bishopsgate. It is because of these donations that research, such as this article, can be produced. On a more reflexive level, this research has in a way contributed to these collections. During our interview with Stuart Feather, he gave us John Chesterman’s ‘25 YEARS OUT’ badge to deposit in the HCA.Footnote 131 Moreover, the oral histories produced for this research will be deposited in the HCA. These archives help to inform public memory of GLF and the gay movement more broadly. For example, during our research a GLF badge held at the LSE was on loan to Queer Britain in London, a museum dedicated to gay history. The frequency and variety of badges in archives specializing in collecting gay material speaks to their significance and memorability as material objects in gay history and tangible remnants of this past.Footnote 132

For many GLF members today, their badges are precious objects. On one level, they encapsulate the worth that they attributed to them in their original context, being a means to come out and express their identity to themselves and others, which continued and expanded with other badges following the fracturing of GLF. On another level, from the 1990s they came to signal one’s participation in the history of GLF. Today, for many GLF members their identity and outlook is shaped by the history that they were part of, with the GLF badge communicating this to others whilst affirming it to themselves. In this way, the GLF badge was and is in flux as its meanings and uses have evolved over time.

V

When asked when GLF ended, some of our narrators stated that it had not. John Lloyd responded to a question on when his involvement with GLF ended by saying ‘It continues today. No, never. No. As it was radical politics, it never ended.’Footnote 133 Julian Hows echoed a similar sentiment of the longevity of GLF when he said ‘If you think of GLF as the embodiment of a concept rather than the formal network, then, then, then the bottom of the concept goes on and on and on.’Footnote 134 Similarly, Martin Edwardes said ‘I don’t think [GLF] has [ended]…the principles are still there.’Footnote 135 In a similar vein, our narrators often noted the profound impact that GLF has had on their post-GLF activism. Some former GLF members continued and continue to work in the gay movement, as well as in other adjacent political and social struggles. For example, Nettie Pollard listed a range of groups and activities that she has involved herself in following GLF, such as Red Rag, Feminists Against Censorship, squatting, and claimants union work, whilst Peter Tatchell has become a prominent gay activist.Footnote 136

More subtly, GLF greatly affected people in areas outside of political activism, including relationships, work, and one’s outlook on life. This aligns with a principle of GLF, as Andrew Lumsden put it, ‘we [were] not trying to change Parliament, or the law, we [were] trying to change ourselves’.Footnote 137 Often, GLF succeeded in this in not just the short term, but also the long term. GLF members sometimes met their life-long partners in GLF, including Philip Rescorla and Martin Edwardes who met at a GLF disco, and Angela Mason, who met her partner Elizabeth Wilson through GLF.Footnote 138 Martin reflected that his involvement in GLF and other ‘LGBT+ organizations’ made him believe that he could do things, or ‘liberated’ him, including working in computing, getting a Ph.D., and lecturing in linguistics at King’s College London.Footnote 139 Michael Parkes denied being an ‘activist’, but noted the impact of GLF on his work: ‘The gift Gay Liberation gave me was that I could love my neighbours myself. And in all the work I’ve ever done that has been the pretty well sole motivation to do it.’Footnote 140 Andrew described his first experience of GLF as ‘like that sort of thing in Alice in Wonderland, you go through a little door and suddenly you’re in a wonderful garden…so that transformed, completely, my life’, and later, that ‘before [GLF] I was a half-formed individual’.Footnote 141 Julian, with great emotion in his voice, said that

GLF and its structures…taught me everything there was to know about community involvement, community empowerment, community organizing. So the structure of all that, in terms of it being flat, volunteer-led, and those sorts of things, is something which, I’m getting tearful now, is something which actually is still with me today and has prompted and given me the background for every piece of work I’ve ever done.Footnote 142

Although speaking about his experience of GLF in America, Mark Segal epitomized these sentiments when he said that ‘People asked me what university I graduated, and I always like to say Gay Liberation Front.’Footnote 143 As many members of GLF still carry the principles of GLF with them today, although GLF fractured in 1973 it never fully went away. It also highlights the more nuanced view of GLF as an outlook, set of principles, and lifestyle, rather than an organization. Through the badge, the lasting impact of GLF is revealed and our understanding of GLF is broadened.

Finally, the significance and role of badges, not just within the gay community but in society as a whole, must be emphasized, particularly as an avenue for further study. Peter Tatchell said that ‘in that era, the early 1970s, wearing a badge was a major means of social communication’.Footnote 144 Julian reflected on badge-wearing that ‘It’s showing people where you stand and where you’re at. But on a more subtle level, I think it’s also about, about inviting a conversation. Being open to the interchange.’Footnote 145 Similarly, Perry Brass, who was in New York GLF, said that ‘if you were on the left, you would wear [badges]. There was something very alternative about the badges. They, they were a form of communication, they immediately communicated your political or cultural stance’.Footnote 146 These reflections demonstrate the power of badges to communicate one’s beliefs and identity. Moreover, despite differing political contexts in the UK and the US, Peter's and Perry’s similar reflections demonstrate a commonality of badge-wearing in both countries. They also offer a wider perspective on a culture of badge-wearing amongst the left of this period, allowing an individual to openly align themself with a myriad of causes and identities. Emblematic of this is a collection of badges donated by Peter to the HCA which blends gay and non-gay badges, such as ‘OUTRAGE!’, ‘CROYDON CND’, ‘ABOLISH THE MONARCHY 1977’, and ‘solidarity with the people of Chile’.Footnote 147

Looking at the material cultures of social movements and personal collecting practices, in conjunction with oral histories, is a new inroad into understanding the personal impacts of social movements on people’s lives. As such, this article invites historians to apply this methodology to the study of other social movements in different spatial and temporal contexts, such as in rural places. On one level, the design of badges, including any text, symbols, and colours, serve as a statement and visual message that one can wear. On a deeper level, the act of wearing a badge is a personal decision. An individual must obtain and pin on a badge, whether that be publicly or privately, and have the self-assurance to do so. The GLF badge was, and indeed is, a communicator of identity and has left an inheritance of badge-wearing in the gay community that persists today.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Will Mitchell for his constant encouragement, guidance, and kindness. We would also like to thank Tim Hochstrasser, Alex Mayhew, and Richard Saich for their comments on earlier versions of the article, and for their support. Thank you also to the two anonymous reviewers for their invaluable feedback, as well as to the editors of The Historical Journal. Finally, thank you to our narrators for trusting us with their stories.