On June 2, 1931, Leon Fraser, the American vice president of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), arrived by ship in New York City from Europe. He was met by the gentlemen of the press who wanted to know “what had caused the world depression.” To the reporter’s frustration, Fraser’s reply was, “any cause you wish. … I don’t know of any explanation.”Footnote 1 He was not alone.

The European financial crisis of 1931 had begun in Vienna 3 weeks earlier, with the failure of the Austrian Credit-Anstalt, and was still in its early phase when Fraser spoke to reporters in New York. Uncertainty about the future abounded, and there was widespread talk of a crisis of capitalism. “Can we prevent an almost complete collapse of the financial structure of modern capitalism?” asked John Maynard Keynes in 1932.Footnote 2 Over the next 4 months, the world as Fraser and his contemporaries knew it was turned upside down. In June and July, Germany suffered a violent banking and currency crisis, and in September, Great Britain left gold amid another round of bank failures, and a run on the dollar hit the US. The world was in depression.

Five devastating years later, in 1936, it was clear that it was not only the international economy but also the discipline of economics that was in crisis as received wisdom lay in shatters. In his General Theory published that year, Keynes argued that “animal spirits” and speculation motivated financial markets and made the economy unstable: “It is an outstanding characteristic of the economic system … that … it is subject to severe fluctuations in respect of output and employment…”Footnote 3

Also in 1936, Federal Reserve Board economist Winfried Riefler wrote that the times “witnessed the collapse of nearly all the financial arrangements in terms of which banking theorists have been trained to think.”Footnote 4 Reviewing five recent volumes on central banking, Riefler noted that a lack of consensus among central banking experts went far “beyond the bounds of desirable and stimulating intellectual controversy. It approaches an intellectual scandal, with shocking effects of the gravest import upon the formulation of public policies.”Footnote 5 Such statements illustrate the meaning loss linked to radical uncertainty as received wisdom and past operating models are no longer useful, but a new dominant narrative is yet to emerge. Crises lead to an urgent need in society for sensemaking through narrative emplotment. Without a convincing and coherent dominant narrative, there is no explanation of cause and effect, no history to be remembered and used, and no lessons to be made. There is no actionable knowledge and no blueprint for decision-making and actions in future crises.Footnote 6

In this article, I draw on a cultural conceptual framework of sensemaking and narrative emplotment under radical uncertainty. I use this framework heuristically to examine how contemporary central bankers, economists, and observers made retrospective sense of and used their recent experience of the European financial crisis of 1931 to understand what had happened; to legitimize their actions; and to produce memory, lessons, and a blueprint for future actions. On the basis of an “actor’s point of view” approach and writing history forward, I analyze how a select group of contemporaneous organizations and actors searched for an explanation of the European financial crisis of 1931 and, by extension, the Great Depression. In the next section, I present my conceptual framework, analytical strategy, and empirical material. I then analyze how the various actors categorized and made sense of the European financial crisis through emplotment, and proceed to discuss the views of the contemporary actors and those of later historians. A brief conclusion closes the article.

Narratives, Analytical Strategy, and Empirical Material

A few days after Britain left gold on September 21, 1931, the New York Times demonstrated how narratives may construe causality and shape perceptions of events and actors. The newspaper noted how US President Herbert Hoover and Britain’s Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Snowden externalized the causes of their nations’ economic woes. The New York Times construed a causal chain arguing that Britain’s currency crisis “trace directly back to the German crisis of last June, which goes back to the failure of the Credit Anstalt some time before, which goes back to a terrific fall in commodity prices, which goes back to overproduction in raw materials, which goes back to the inflated prosperity in the United States, which was ended as some would have it by the Hatry crash in England.”Footnote 7

The newspaper also shared its own view of a systemic breakdown as the underlying cause, noting: “The break is only the symptom of a run-down condition in a system of which we are a part.”Footnote 8 It hinted at how narratives can be used to assign blame, legitimize actions, and construct causality. Narratives are social and performative. They construe heroes and villains, silence some things, and remember others. They legitimize some actions and states of affairs while marginalizing others, and they contribute to shaping actors’ and communities’ worldviews or cultural and ideological lenses. They provide blueprints for decisions, actions, and practices. Conflicting narratives compete about making sense of events, actors, and social and economic outcomes.Footnote 9

Uses of history and sensemaking through narrative emplotment are everyday occurrences in nations and organizations such as central banks. They are particularly relevant in periods of social and economic transformations and in the wake of events or situations fraught with meaning loss and radical uncertainty about the future, as was the case during and after the European crisis.Footnote 10

When a crisis seems to be over, a need for both prospective and retrospective sensemaking arises. This is because the recent experience calls for understanding, explanation, remembering, and learning; while the uncertainty of the post-crisis situation calls for a new vision, an imagined future for where to go from here, and how to navigate uncharted waters. The two processes are closely intertwined and unfold through the emplotment of past events into a coherent narrative that constructs a shared, or contested, understanding of the experience that may enable learning, new worldviews, and imagined futures that serve as blueprints for decision-making and action.

As reporters asked Fraser to explain the economic distress at the pier in New York, it was clear that without narrative, there can be no explanation, no cause and effect, and no heroes or villains. Narratives are sensemaking instruments that create order and meaning, and cause and effect out of a “murk of chaotic experience.”Footnote 11 Actors and communities deal with meaning loss and uncertainty and enable decision-making and action through emplotment of events and actors into a coherent narrative.

In Seven Crashes, Harold James notes, “There was a pervasive uncertainty about how to interpret news” in the early 1930s.Footnote 12 Sensemaking takes a different approach in that it is not just interpretation but also a “narrative construction of reality.”Footnote 13 Sensemaking is the “active authoring of events and frameworks for understanding, as people play a role in constructing the very situations they attempt to comprehend.”Footnote 14

Narratives are intimately related to interests, ideology, and power as actors are engaged in a narrative struggle about how to make sense of their past and present and what cultural blueprint to follow. During uncertainty, counternarratives may challenge a dominant but contested narrative. As Thomas Piketty argues, “Out of a clash of contradictory discourses … comes a dominant narrative or narratives” to legitimize a state of affairs, decisions, and actions.Footnote 15 Arguably, that was what happened to economics when a Keynesian market failure narrative overtook the neoclassical government failure narrative during the great transformation of the 1930s.

Granted, viewing economic theory as narrative, ideology, and a cultural blueprint is not how realist mainstream economists see the world. However, a somewhat alternative view is emerging under the umbrella term “narrative economics.” Beginning with Deirdre McCloskey’s work in the 1980s, a few economists began taking the role of language, metaphors, and rhetoric in economics seriously.Footnote 16 Robert Shiller’s work, in particular, has received much, if partly undeserved, attention.Footnote 17 George Akerlof and Dennis Snower argue that narratives influence decision-making and actions through “simple mental models whereby we can identify causal relations that enable us to account for past and present events in terms of antecedent events.”Footnote 18 Rather than models in the minds of individuals, I argue that narratives are social semantic devices with a beginning, a middle, and an end. Narratives also have a plot that assigns meaning to events and actors, and shapes the cultural lens and blueprint through which we see and act in the world—past, present, and future. Importantly, it is possible to emplot and narrate the same event in several ways without contradicting the empirical material.

Thus, economist Evelyn Forget argues that “any two or more points in time can be linked in a very large number of ways. Multiple histories are not only conceivable but usual, and no amount of fact checking will eliminate them.”Footnote 19 Writing history, she notes, “lies in … establishing beginnings and endings, and building narrative bridges between the relevant events in such a way as to establish meaning.”Footnote 20 That was exactly what the New York Times and the actors and organizations did in 1931.

The analytical strategy in this article is driven by the conceptual framework and processes described above. Like Natalie Zemon Davis in her Fiction in the Archives about sixteenth-century pardon-tale tellers, I am not looking for the “real facts” but for how central bankers and other contemporaneous actors “through narrative … made sense of the unexpected and built coherence into immediate experience.”Footnote 21 The focus of this article is how contemporaneous actors narrated the European financial crisis of 1931, shaped early memory and perceptions of its causes, and produced potential lessons. I use thick description “light” to present my close reading of each text. As part of this analytical strategy and to capture the actors’ point of view, I deliberately quote and paraphrase the actors quite extensively.

My evidence consists of texts by contemporaries who, similar to Fraser, struggled to account for past and present and make sense of events and the radical uncertainty they were facing. Matters were only made worse as Germany and Great Britain were hit by multiple forces they did not fully understand and could not control, no matter how hard they tried. What all observers did understand, however, was that the monetary and financial events in the summer and fall of 1931 were wreaking havoc in Europe and the US. Even before Credit-Anstalt’s failure in early May, radical uncertainty was widespread. In April, Bank of England’s governor Montagu Norman wrote to the Federal Reserve’s George Harrison that “conditions are perplexing, abnormal and beyond understanding.”Footnote 22 A few weeks later, upon learning about the outbreak of the Austrian Credit-Anstalt crisis, Bank of England’s Harry Siepmann shared his imagined future with Frederic Leith-Ross at the Treasury in London. This, Siepmann said, “may well bring down the whole house of cards in which we have been living.”Footnote 23 About 4 months later, he was proved right as Britain left gold, and the currency crisis spread to the US.

Below, I trace how Fraser’s and Siepmann’s colleagues from the BIS, the Federal Reserve, and the Bank of England explained the crisis after the fact. These texts, as well as texts from the Banque de France and the German Reichsbank, from the economist Ralph Hawtrey, and a few others, and from the historian Arnold Toynbee together constitute the empirical material in my analysis of retrospective sensemaking and narrative emplotment of the crisis. I have selected these specific actors because of their direct involvement during the 4 months between May 11—when the Austrian crisis broke out—and September 21—when Great Britain went off gold. The texts from the BIS, the Federal Reserve, and the Bank of England were all written after the crisis and most of them within the first year after the breakdown of the gold standard.

In the case of the noncentral bankers’ narratives of the crisis, the first is Hawtrey’s The Art of Central Banking, published in 1932 as a direct response to the European crisis. Hawtrey was trained as a mathematician and economist. A highly respected Treasury expert, he was part of the British delegation at the Genoa Conference in 1922 and had published extensively on money and central banking. I also consider the view of the renowned American economist, money doctor, and expert on financial crises, O. M. W. Sprague. Another observer was the previously mentioned Toynbee, a prominent London School of Economics (LSE) professor of history, who, from 1925 and well into the 1950s, wrote the annual Survey of International Affairs. In “Annus Terribilis 1931,” Toynbee applied his historical civilization perspective to the European crisis.

So, why these central banks and these observers? First, I do not lay claim to any form of representativeness in the nomothetic statistical sense of the term. This article is an idiographic study of how important actors struggled to understand the financial crisis of 1931 after the fact. Still, considered as a case, the process analyzed here is not an isolated occurrence. It contributes to an understanding of how actors make sense through narrative emplotment, and how they may use recent history in the aftermath of crises in which uncertainty dominates. These actors’ contributions and struggles to understand their world are important in their own right. To be clear, I am not in search of any “true” causes of the European crisis but of the coherence and meanings assigned to it after the fact by important actors. This article contributes to our understanding of how some important actors and organizations dealt retrospectively with and construed causal explanations of the crisis in 1931. Second, it contributes to the problematization, recently opened on the US by Mary O’Sullivan, of the dominant historiographical narrative blaming central banks for the European financial (twin) crisis of 1931.Footnote 24

Central Bankers Making Sense of the European Financial Crisis of 1931

Since Walter Bagehot’s Lombard Street in 1873, central bankers have seen it as part of their job description to contribute to financial stability by acting as lenders of last resort during a financial panic. As central bankers faced the Austrian, German, and British crises, they stepped up armed with Bagehot’s operating model and their own experiences and analogies. All of it proved inadequate. The scale and scope of the European crisis was unprecedented, and they struggled to make sense of it.Footnote 25

While the Bank of England, founded in 1694, was still the most prestigious and influential central bank, two newcomers had joined it as important players: The Federal Reserve Bank of New York (established in 1914 as part of the Federal Reserve System) and BIS (set up in 1930 under the Young Plan) were to facilitate German reparation payments and act as a central bank for central banks. These three organizations were at the center of the efforts in 1931 to halt contagion from the Austrian crisis to other countries. How, then, did these actors narrate the financial crisis and its effects after the fact? What causal chains did they establish, what causes did they see as the most important, who and what were to blame, and what lessons did they construe from the recent crisis? In other words, which narrative came to dominate?

The BIS and Learning from the Crisis

In contrast to other central banks, the BIS did not have a national mandate and could intermediate but not create money. It was owned by a number of central banks and a few American commercial banks and managed by two Americans—Gates McGarrah as president and Leon Fraser as vice president. Other positions were occupied by central bankers posted by national central banks, among them the Austrian economist Hans Simon, who worked for Fraser as an advisor.Footnote 26 Here, I discuss Simon’s and the BIS’s narratives about the European crisis. Two texts written by Simon are of particular interest because they aimed at using the recent experience to produce lessons and memory for future central banking practices. Using and learning from history requires an account that can be used to remember some version of the past and imagine an uncertain and unshaped future.Footnote 27 Hans Simon produced such an account.

On June 2, as Fraser arrived in New York City, Simon finished a memo on the “Lessons of the Austrian Crisis.” Simon was directly involved in the struggle to halt the Austrian crisis. He spent weeks from May through June in Vienna working with his British colleague Francis Rodd and the Austrian National Bank. Although the worst was still to come, Simon believed “that the first storm is over” and wanted to “deal with certain features which seem to be of typical importance far beyond the individual case.”Footnote 28 In a letter to the American economist Walter Stewart, Simon explained that he wanted “to draw attention to some of the problems which have arisen in the case of the Credit Anstalt and which I believe will be inherent to all similar situations, as well as to the methods by which possibly at least a partial solution could be found.” Stewart called the note “a first attempt at drawing some conclusions from the Austrian episode.”Footnote 29

Simon wanted to provide a blueprint for uncertain “future contingencies” and presented a “too big to fail” doctrine for capital-importing countries with universal banking systems. With a large bank failure in a debtor country, such as the Credit-Anstalt’s, intervention might avoid a “sudden stoppage of the economic process of the country.” In a later note, Simon stressed that the international financial system had become increasingly interconnected and burdened with “an enormous superstructure of private credit … superposed on a comparatively small basis of gold.”Footnote 30

Confidence in the system was under threat, and “a panic among the foreign creditors … and perhaps even in Germany” was the worst-case scenario. “Only quick and energetic action like a wholesale guarantee for the liabilities of the institutions, would appear to lead to the requisite results.”Footnote 31 Simon then returned to the question of central bank intervention. The Austrian National Bank had followed “the time-honoured rule … of paying out at once any sum withdrawn in order to stop the run.”Footnote 32 This action had increased the note circulation and led to fear of inflation, but in the case of the failure of a big bank, the central bank must not “shrink from rapidly increasing the circulation in order to prevent the catastrophe.”Footnote 33

In the case of the Credit-Anstalt, “free discounting and increasing the circulation, had to be followed.”Footnote 34 The National Bank had not raised the bank rate for fear of increasing “the apprehension of the public,” but Simon’s lesson from the Austrian situation was that central banks should increase the money supply, but “only at considerably increased interest rates.”Footnote 35 The Austrian experience with an exodus of capital also “teaches an important lesson.”Footnote 36 It called for central bank assistance from abroad and from the BIS, which would need foreign exchange deposits from national central banks to be able to act faster.Footnote 37

Then, 4 months later, when the house of cards had fallen and the gold standard was abandoned, Simon wrote a new note on what to do in a future crisis of confidence in the financial system. The note addressed systemic problems, including the deflationary bias of the gold exchange standard and the problematic role of governments in monetary matters. Without a change, he stated, the world was “doomed to go through even worse experiences than those with which it has already been stricken.”Footnote 38

Simon’s notes demonstrate the BIS’s ambition to remember and draw lessons from the recent crisis in a financial system more internationalized and interdependent than ever before. The rapid expansion of national and international finance and short-term credits had dramatically increased the fragility of the financial system. Simon’s focus on these structural problems as well as international political problems meant that securing future international financial stability could not be left to central banks alone.

The BIS’s second general meeting took place in Basle on May 10, 1932, 1 year after the Credit-Anstalt failure first became public. That year’s annual report was partly based on Simon’s notes and told the story of a turbulent second year at the new organization. Short-term capital flows and the interconnected financial system that had emerged after the Great War had led to the fragile financial system and expansion of credit, also mentioned by Simon. Austria and Germany in particular had faced uncertainty and loss of confidence, exacerbated by their weak positions as deficit countries.

The massive credit expansion and short-term cross-border capital flows were signs of instability, and short-term debt and foreign exchange withdrawals had “threatened an immediate severe dislocation of the international credit system.”Footnote 39 But the depression must not be reduced to a monetary phenomenon, the BIS noted. “Fundamental reasons for the conditions, and the possible correctives, lay far deeper in the economic system than those involving only immediate monetary steps or normal credit methods.”Footnote 40 The monetary and financial system had become international and interdependent, but “the menace of this situation did not appear as self-evident as it does today.”Footnote 41 In retrospect, the BIS noted, it was only a matter of time before a “breakdown of confidence” would also “break the system.”Footnote 42 The tipping point was the failure of the Credit-Anstalt in Austria in May 1931. From there, a “tidal wave of uncertainty and fear” spread to Hungary, Germany, Great Britain, and Scandinavia “sweeping down their currencies, and then, backwashing into the United States.”Footnote 43 It was a “crisis of confidence of almost panic proportions.”Footnote 44

The BIS narrative was one of inevitability and uncertainty resulting from systemic issues in the political economy combined with severe fault lines in the financial and monetary system. BIS’s management felt that uncertainty and financial problems had reached new levels and left them without any relevant historical analogies or experiences to provide a clear blueprint for intervention. The world of finance, credit, and money had changed fundamentally, along with everything else. Increasing the bank rate, the usual tool, had “proved inoperative in checking the withdrawal of foreign funds,” the BIS noted.Footnote 45 As the crisis set in, so did risk aversion, with “mobile capital … seeking security, with little or no return, rather than high interest rates coupled with currency and credit risks.”Footnote 46

Central banks had not failed. In fact, they made a “mutual effort to hold together the fabric of the international credit system” during the “rising tide of monetary and financial difficulties.”Footnote 47 They had been in closer contact than ever before and exchanged information and views.Footnote 48 Still, central bank cooperation alone could not deal with structural, political, and economic issues. Echoing Simon, the report noted that future monetary stability would require that “international relations in the economic field are radically improved.”Footnote 49 Central bank cooperation was helpful, but “the real solution of the problems involved requires the determined and concerted action of the governments.”Footnote 50

What emerges from the BIS story is a picture of a heavily interdependent transatlantic financial system destabilized by massive short-term capital flows and debt as well as underlying structural economic and political problems. This new unstable financial architecture had developed since the Great War without notice, or if noticed, not taken seriously. In the perfect storm of 1931, it led to a crisis, a breakdown of confidence, and the failure of the gold standard. The frozen credits and exchange controls that followed in the wake of the 1931 crisis only made things worse. Just how close capitalism had been to a complete breakdown shined through the BIS’s comment that the “most remarkable thing is that the economic system has been able to withstand such dislocating forces.”Footnote 51 Still, though capitalism had been severely tested by the 1931 crisis, it had not broken down.

“The Match and the Powder”: The Federal Reserve Bank of New York

On September 12, as the Bank of England was struggling to stabilize sterling, W. R. Burgess, a statistician and deputy governor at the New York Federal Reserve, wrote a note on “the general situation and Federal Reserve policy.”Footnote 52 Burgess observed that the “public both in this country and abroad has become unwilling to make future commitments. … In a civilization so highly depending upon credit, this state of discredit, as Bagehot calls it, might easily lead to disaster and to an overturn of the existing social and economic order.”Footnote 53

Imagining a breakdown of capitalism, Burgess called for restoring public confidence, but there were other serious problems. Reparations, commodity prices, foreign loans, and the tariff wall were problems that called for political solutions, but “if no constructive move is made until these problems are solved it may be too late, because economic disintegration may have gone too far.”Footnote 54 His concern about lack of confidence, structural fault lines, the legacy of the Versailles Treaty, and (dis)credit both expanded and intensified the BIS’s view. The New York Federal Reserve had to act because “without … real financial leadership … a continuous economic disintegration might occur.”Footnote 55 Uncertainty was increasing by the day, and Burgess feared what the future would hold; hence, his call for financial leadership by the Federal Reserve.Footnote 56

Allan Sproul, a lawyer by training and assistant deputy governor at the New York Federal Reserve, shared Burgess’s concerns and needed to make sense of what had happened. On November 30, he wrote a report entitled The Credit Crisis of 1931 and sent it to all Federal Reserve governors.Footnote 57 The global credit mechanism was strained, Sproul wrote. “A world-wide economic depression, of a magnitude probably never before experienced, has multiplied international financial problems. Weak points in the credit structure, whether the product of unwise financial policy in immediately preceding years or a delayed legacy of the world war, have been severely tested.”Footnote 58

Foreign short-term debt was “a constant threat to financial stability in some countries,” and the “first acute threat came in May 1931” when the Credit-Anstalt fell into trouble as short-term funds were withdrawn from the country and “domestic confidence was severely shaken.”Footnote 59 The abandonment of the gold standard and instability spreading to other countries would be inevitable unless the run was checked by “such a display of strength that confidence is quickly restored and funds again flow in as well as out.”Footnote 60 Confidence was not restored, and the Austrian crisis spread to Hungary and Berlin, where it was reinforced by “a disturbed political situation” and an “exaggeratedly large volume of foreign short-term funds.”Footnote 61 Despite President Hoover’s call for a debt moratorium on June 20, capital flight accelerated, and foreign credits quickly disappeared. When the German Danatbank failed on July 13, Germany introduced exchange controls and the continental crisis crossed the channel to Britain, where “an international run on the London money market” took place.Footnote 62 Despite huge credits from the US and France, Great Britain left gold on September 21.

Next, Sproul considered the “world-wide repercussions.”Footnote 63 The BIS credit to Austria had failed to halt the flight of capital. Despite this perceived “too little, too late” problem, Sproul stressed the role of the BIS in organizing the aid to central banks and acting as a “clearing center” for information.Footnote 64 Without the BIS, “such emergency relief would have been impossible.”Footnote 65 The narrative established a direct causal link between the Austrian, German, and British crises and the centrality of the gold standard and an overstretched credit structure. The negligence by some central banks of the perceived rules of the gold standard (i.e., sterilization by France and the US) had further increased the destabilizing effect of short-term capital flows. The note emphasized the role of “weak points in the credit structure,” such as the huge short-term cross-border capital flows, a problematic financial policy, and the legacy of the Great War (i.e., war debts and reparations as well as a tense international political climate).

On May 14, 1932, Sproul gave a talk to the New York State Bankers Association. He told the bankers that the depression needed to be explained—that is, emplotted—before any “attempt to devise ways and means of preventing a recurrence of the experience” could be made.Footnote 66 Using powerful if somewhat mixed metaphors, he traced the beginning to Austria in May 1931, when the “match and the powder came together.”Footnote 67 Despite “vigorous efforts made to localize the infection, the credit crisis soon spread … endangering the financial existence of one of the leading commercial and industrial countries of the world”: Germany.Footnote 68 Uncertainty and lack of confidence in business, banks, and the dollar as well as an unstable credit structure caused the credit crisis to spread from Austria, and the “normal functioning of the credit system became impossible.”Footnote 69 The Federal Reserve’s annual report published a few weeks earlier also stressed the role of uncertainty and fear in destabilizing the massive volume of foreign short-term funds.Footnote 70

The Bank of England and the Crisis of 1931

Similar to Fraser, Bank of England’s Siepmann struggled to make sense of the European financial crisis and the Great Depression. The day before Fraser arrived in New York, Siepmann wrote a letter to Per Jacobsson, a Swedish economist who had noted problems with the “financial machinery.” Was the depression, Siepmann asked, really “a problem of financial engineering?”Footnote 71 Jacobsson replied that governments and central banks usually did more harm than good when intervening in the economy and they should not sterilize gold inflows, which increased deflationary pressure on deficit countries such as Austria and Germany.Footnote 72 LSE professor of economics Lionel Robbins agreed with the government failure worldview that the depression was “due to monetary mismanagement and state intervention.”Footnote 73

The Bank of England did not publish annual reports, and its sensemaking efforts were less public. Still, in mid-June, Francis Rodd, a Bank of England official stationed at the BIS, wrote a scathing report blaming the French government for obstructing the efforts to halt the Austrian crisis. Rodd wanted the French government’s obstruction to be known and remembered, and he sent his narrative of the endgame in the Austrian crisis to a group of influential people and the Bank of England, of course. In Rodd’s story, only Bank of England’s loan to the Austrian National Bank on June 16 avoided a complete breakdown in Austria. Many contemporaries agreed with him.Footnote 74

British animosity against the French—and vice versa—was nothing new, and when, in 1943, the Bank’s management asked the economist Lucius Thompson-McCausland to write “an accurate secret report” about the sterling crisis of 1931, the report left no doubt that the memory about French obstruction in 1931 was alive and well. Thompson-McCausland had no firsthand experience from 1931 and relied instead on the bank’s archive. In terms of genre, the report came close to that of later historians’ work, but it was told by an insider with the purpose of legitimizing the Bank of England’s actions and decisions during the 1931 crisis.Footnote 75

“The crisis of 1931 came and went within the space of a few weeks,” Thompson-McCausland wrote.Footnote 76 It began with the Credit-Anstalt crisis and loss of confidence, and the BIS “calling for that international co-operation between central banks which the Bank of England had been at pains to foster ever since the Genoa Conference.”Footnote 77 Rodd’s narrative had become part of the Bank’s institutional memory, and McCausland did not disappoint. France had been strongly opposed to the plans for an Austro–German customs union announced in March 1931, and used “her economic advantage in the pursuit of diplomatic aims.”Footnote 78 Despite the threat to the economic fabric of Austria, “France made no haste to the rescue,” and only Bank of England’s loan on June 16 averted “the final collapse” in Austria.Footnote 79

The crisis nevertheless spread to Germany—despite Hoover’s plan for a moratorium and a joint central bank credit of US $100 million to the Reichsbank—when German bank holiday “decided the issue of the European financial crisis.”Footnote 80 The Bank of England had chosen international cooperation for “systems of self-regarding, self-sufficient, financial defense. … But obstruction had tipped the scale the other way.”Footnote 81 Despite a £50 million credit in August to the Bank of England from the New York Federal Reserve and the Banque de France, the drain of sterling soon resumed, and the pound was “forced off gold” in September.Footnote 82 As “in every other crisis of this eventful summer, the immediate cause was the mass movement of capital under the impulses of speculation or of fear.”Footnote 83 Cooperation had failed. With the benefit of writing in 1943, Thompson-McCausland linked the crisis to the rise of “inward looking elements of nationalism or isolationism.”Footnote 84

The Bank of England’s narrative has a clear hero and villain and an unmistakable plot in which France obstructed Bank of England’s hard work for central bank cooperation. In this narrative, Britain and sterling were at the center of the world and future prosperity, but the system was falling apart because of lack of cooperation and the rise of nationalism in Germany, France, and the US. Thompson-McCausland did identify capital flows, speculation, fear, and a breakdown of confidence as underlying causes of the exchange crises in summer 1931, but lack of central bank cooperation decided the issue. Nationalism and self-interest ruined Great Britain’s world leadership and the gold pound’s assurance of the international system and prosperity.

Banque de France

The Banque de France and the German Reichsbank were in quite different situations before, during, and after the financial crisis. They were also in bad standing with each other, with France the most insistent country in terms of reparation payments and Germany the country most against them. Germany’s economy was weak, with huge amounts of short-term foreign debt and political polarization, not least because of the reparation payments required by the Versailles Treaty. In summer 1931, the financial and monetary system fell apart as capital left the country at catastrophic speed, and Danatbank—one of Berlin’s big banks—failed on July 13. The German government called a national bank holiday, and it de facto left gold. France was in a much better position as a surplus country with large gold reserves from an undervalued franc and the sterilization of the gold inflow. As explained above, observers such as Jacobsson and McCausland blamed France and the Banque de France for being uncooperative, disregarding what Keynes called the “rules of the game” and increasing the deflationary pressure on deficit countries such as Germany.

In its annual report for 1931, the Banque de France established the familiar chain of causality. In 1931, an economic crisis was turned into a “banking and monetary crisis which first broke out in Vienna, then spread to Germany. … London was also affected. In spite of the powerful support it received, in September the Bank of England was forced to suspend the convertibility. … [A]nd the American market itself temporarily felt the after-effects.”Footnote 85 According to the Banque, “purely technical causes,” a likely reference to sterilization, could not explain the financial crisis.Footnote 86 In fact, an “abuse of credit” and a mistaken “artificial policy of easy, cheap money” had led to “the birth and spread of the crisis,” which was exacerbated by political uncertainty and lack of confidence, which had “purely psychological causes.”Footnote 87

Looking toward the future, the Banque stressed the need to fight the pessimism, and deflation was a necessary part of the process: “Every crisis, however great or long, is eventually overcome, and the suffering which is the price of past excesses and mistakes sooner or later opens the way to recovery and prosperity.”Footnote 88 The Banque de France had “pursued a policy of broad international cooperation” with other central banks.Footnote 89 When the run on sterling began, Banque de France responded to a request from the Bank of England to assist in accordance with a historical “spirit of collaboration.”Footnote 90 Despite American and French credits to the Bank of England and the UK Treasury, “the outflow of gold could not be stopped. … This commitment to international cooperation is reflected not only in the funds allocated, but also in the principles underlying our foreign exchange policy.”Footnote 91

Several other observers contested that foreign exchange policy, but the Banque insisted that its actions were based on “the harsh lessons of experience” and a determination to maintain the stability of the franc.Footnote 92 The Banque had cooperated but also made clear: “We regard convertibility into gold not as an outdated constraint, but as a necessary discipline.”Footnote 93 This is a discipline other central banks (e.g., the Bank of England) should have observed as well. The gist of Banque de France’s counternarrative to Bank of England’s narrative was that the Banque did cooperate, and the Bank of England had itself only to blame for its failure to remain on gold. Easy money and abuse of credit outside of France had broken the disciplinary constraints of the gold standard, which led to excessive pessimism and a breakdown of confidence in the system.

The German Reichsbank

Germany, perhaps the main “victim” of the financial crisis, emplotted things differently. Germany had suffered from the deflationary bias stemming from the gold standard and the sterilization of gold inflows, in contrast to the US and France. Most importantly, however, in the Reichsbank’s narrative, the entwined legacy of the Great War and the Versailles Treaty was the single most important cause of the economic, monetary, and financial problems that peaked in summer 1931.

The Reichsbank’s annual report for the year 1931 began: “An unprecedented crisis is shaking the world. … The reporting year saw the onset of a devastating crisis of confidence that senselessly tore apart old credit relationships both nationally and internationally.”Footnote 94 Similar to the other central banks, the Reichsbank viewed the crisis of confidence as a significant factor in the financial breakdown in 1931. However, the “true causes of the economic catastrophe” was the war and the “gigantic complex of political debts … the reparations burden imposed on Germany is of particular importance.”Footnote 95 Because of reparations, foreign creditors realized that Germany was “heading for a collapse” and, as they lost confidence, they withdrew money from Germany.Footnote 96 A new system was needed to avoid further economic and social catastrophes. The collapse of the Credit-Anstalt had increased uncertainty and led to the “crisis of confidence of a kind and magnitude never before experienced.”Footnote 97

The combined internal and external drain left the Reichsbank with the “dual task” of ensuring the reichsmark and the German banking system at the same time, but the run on both the short-term foreign debt and the banks “simply exceeded the … Reichsbank’s ability to support them.”Footnote 98 Deflation and credit restrictions followed—and when the BIS and central banks declined to assist, the closure of banks and the stock exchange was inevitable. The Reichsbank had no options but to acknowledge that it was beyond its “power to eliminate the internationally induced credit crisis.”Footnote 99

A small hope had appeared on June 20 as President Hoover announced his plan for a debt moratorium. However, “due to the resistance” against the plan, mistrust increased in Germany and abroad.Footnote 100 As noted earlier, a US $100 million credit from the Bank of England, the Federal Reserve, and the Banque de France proved insufficient as well.Footnote 101 The Reichsbank report did not say explicitly what resistance it referred to, but it was clear that the bank had the French in sight. The inadequacy of foreign assistance and the emplotment of the credit crisis as “internationally induced”—and most of all the blame of the legacy from the Great War, war debts, and in particular, the imposition of massive reparations on Germany—all served to make Germany a victim and externalize the causes of the financial crisis.

A Few Economists and a Historian Make Sense

Economists and historians think differently. As Hans Simon made clear, his ambition was to generalize from the evidence provided by the European crisis and to use it to draw lessons for the future. Simon put less emphasis on context and actors than a historian would. These disciplinary differences also came out clearly in Hawtrey’s and Toynbee’s texts.

Ralph Hawtrey and the Art of Central Banking

In the British Treasury, Ralph Hawtrey shared Simon’s interest in central banking, but not his view of central banking proper. In The Art of Central Banking, published in 1932, he explained his aim along the same lines as Simon, “In view of the experience which has been obtained … the principles of the art require reconsideration at the present day.”Footnote 102 Also similar to Simon, Hawtrey emphasized how “the crisis of 1931 differed from earlier crises in its international character.”Footnote 103 The Art of Central Banking was Hawtrey’s contribution to the sensemaking process after the financial crisis. In a section tellingly titled “The Inherent Instability of Credit,” he noted how vicious circles of credit expansion and contraction drove the business cycle. “It sometimes happens that the situation gets out of hand,” he wrote, but “the vicious circle of deflation can always be broken, however great the stagnation of business and the reluctance of borrowers may be.”Footnote 104

Breaking the circle was the responsibility of central banks that had allowed first the boom and then bust and deflation to spin out of control, resulting in “the industrial depression and unemployment, the insolvencies, bank failures, budget deficits, and defaults.”Footnote 105 Many other prominent contemporary economists, including Keynes, Bertil Ohlin, and Irving Fisher, debated the causes of the world depression. Fisher viewed the Austrian, German, and British crises as “international accelerators of the vicious spiral–1931.”Footnote 106 Wesley Clair Mitchell, Fisher, and Ohlin each focused more on the business cycle as endogenous to capitalism and less on the specifics of the 1931 crisis and the role of central banks.Footnote 107

Despite the phrase “the inherent instability of credit,” Hawtrey saw the business cycle as a purely monetary phenomenon driven by central banks. He used the depression and the 1931 crisis to produce lessons for monetary policy and the lender of last resort, and he was unforgiving of central banks. The “calamities of the past 3 years have been caused not by the mere absence of co-operation, but by the disastrously synchronized unwisdom.”Footnote 108 Similar to the Austrian School, Hawtrey explained the business cycle as a result of commercial banks’ credit creation. “But bankers are human,” he noted, excusing them of any wrongdoing and blaming commercial banks’ credit creation on central banks.Footnote 109 Thus, the narrative was set for central bank failure, and Hawtrey delivered by arguing that the depression was caused by central bank “action … taken not weeks or months, but years too late.”Footnote 110

The result was “the sinister disorders of a financial crisis” in 1931.Footnote 111 The financial crisis was uncharted territory because of its international character. Hawtrey coined a new concept “international lender of last resort,” and called on the BIS to be that lender, a task it was unable to fulfill, as also noted by Simon.Footnote 112 As a result of the novelty of the crisis’ international and interdependent character, central banks had no useful analogies and no adequate cultural blueprint for how to act. Since the BIS could not create money or act as an international lender of last resort “if many countries were suffering from extreme discredit,” it would have to cooperate with central banks in creditor countries.Footnote 113

This was Hawtrey’s too little, too late story. His narrative silenced the uncertainty, the lack of confidence, the fear of contagion, the time pressure, and the speculative short-term cross-border business practices of banks. Instead, in the same manner as Friedman and Schwartz after him, he put all the blame in one place: central banks. Hawtrey’s ideas of counter-cyclical bank-rate setting meant that central banks were to blame for the “inherent instability of credit.” Despite suggesting that central banking was an art, his narrative was a story of exogenous government failure.

The American economist O. M. W. Sprague, too, noted how the increasing interconnectedness and dependence on massive short-term capital flows of the international financial system had changed the way capitalism worked.Footnote 114 But he took a different view of the crisis. Sprague, who worked as an adviser to the Bank of England, shared the view of markets as sovereign. Yet, he did not subscribe to Hawtrey’s narrative and cultural lens. In fact, he fundamentally disagreed with Hawtrey, arguing that monetary policy could not bring about a recovery: “I do not believe that the depression is primarily due to monetary causes.”Footnote 115 In May 1932, Sprague gave a talk on short-term capital movements across borders. Foreign funds “have been at least a symptom—if not a cause—of disturbance. … The amounts are now far greater than formerly, and there is every reason to believe that short-term funds are far more unstable than they were in the past.”Footnote 116

This new characteristic of finance led to problematic investments, for example, from lack of information in “the case of the Credit-Anstalt.”Footnote 117 Investors and banks would not have lent money to Credit-Anstalt, Sprague argued, “if there had been current figures month by month showing its position.”Footnote 118 He also noted that the world had become too “unwilling to liquidate bad positions,” and central banks continuing to extend credit was not helpful.Footnote 119 He appealed to rational man and argued that it was more important than ever “if we are to avoid acute periods of depression, that in periods of activity a maximum of wisdom and caution be exercised in the placement of capital.”Footnote 120

Unlike Hawtrey, Sprague argued that “central banks through their own operations cannot make this workaday world an earthly paradise.”Footnote 121 Instead, he called for more transparency in bank and company balance sheets and suggested that the BIS should act as a “sort of international clearinghouse for such information.”Footnote 122 Weary of central bank and government intervention, Sprague saw the crisis through the lens of economic orthodoxy, with a focus on “the market,” not money. He imagined a future in which market failure and, by extension, depressions, would be corrected through more transparency. The problem was not capitalism or central bank failure; it was market failure from what economists today call asymmetric information.

Hawtrey’s and Sprague’s narratives had similarities but nevertheless differed. Both men were free-market economists, but they disagreed on the causes of the crisis and over-indebtedness and on the character of the business cycle. Sprague did not subscribe to the view that it was entirely a monetary phenomenon but to the idea of the rational investor. In contrast, the financial crisis inspired Fisher, the “inventor” of the formal quantity theory of money, to make a partial U-turn to a narrative of endogenous over-indebtedness driven by innovation and new-era thinking.Footnote 123

Arnold Toynbee’s Survey of 1931

One of the first public histories of 1931 was Toynbee’s Survey of International Affairs, published in late 1932. The main section of the book, “Annus Terribilis 1931,” dealt at length with the Credit-Anstalt crisis and its repercussions. Toynbee was a professor at LSE and director of studies at the Royal Institute of Foreign Affairs. Inspired by his classics training, Toynbee was particularly interested in the rise and fall of civilizations. This perspective was evident in his history of the 1931 crisis. Toynbee argued that “the catastrophe … which Western minds were contemplating in 1931 was not the destructive impact of any external force but a spontaneous disintegration of society from within.”Footnote 124

Not unlike W. R. Burgess, Toynbee argued that the British “economic world order was in danger of breakdown and disintegration; and that … the existence of Western society itself was at stake.”Footnote 125 He argued that “the very beauty of the economic world order, which consisted in the subtle interdependence of all its architectural members, enhanced the danger of catastrophe now that the strain had come so near to breaking-point.”Footnote 126 In contrast to most of the other storytellers at the time, Toynbee was explicitly thinking in terms of emplotment into “a unitary narrative of outstanding events in a chapter of history which is comprehensible only as a unity if it is comprehensible at all.”Footnote 127 The beginning and the end of that narrative was clearly set out. The British departure from gold was the denouement of the chain of events that began in Austria and ended when Britain left gold, resulting in a “transference of pressure from the United Kingdom to the United States.”Footnote 128

This plot point that the financial crisis spread from Austria to Germany to Great Britain and then to the US was a mainstay of all attempts to make sense of the 1931 financial crisis. So is the plot point of central banks’ and governments’ “international efforts to salvage the Credit Anstalt and to prevent the havoc caused by its failure from spreading.”Footnote 129 Similar to most of his contemporaries, Toynbee saw Bank of England’s loan of US $21 million to the Austrian government on June 16 as “historic, as marking the last occasion … on which the Bank of England was able to play its traditional role of helping to keep the world-wide machinery of international finance in working order,” a sign of the fall of a civilization.Footnote 130

Toynbee’s Survey contained a section titled “Nemesis: The Financial Outcome of the Post-War Years,” written by Harry V. Hodson, an economist and fellow at All Souls College at Oxford University. This section did not alter Toynbee’s narrative but added an economic perspective. Hodson stressed that both the BIS credit to the Austrian National Bank and the June 16 Bank of England credit “probably saved Austria, in the nick of time, from complete financial collapse.”Footnote 131

According to Hodson, two issues stood out in the postwar period’s attempt to return to normalcy. The first was international cooperation, including “the attempt to arrest the collapse of monetary standards in 1931” by central banks and the BIS.Footnote 132 The second feature was political distrust, lack of confidence, and “the insistence of the former Allies on extravagant scales of reparation payments [which] sapped public faith in Germany’s economic and political stability.”Footnote 133 Similar to most others, Hodson also emphasized the destabilizing significance of international capital flows and the resulting freezing of foreign indebtedness, which played an “essential part in determining the course and the violence of the 1931 crisis.”Footnote 134

Toynbee’s “breakup from within” of British centered capitalism and Hodson’s narrative resonated with the recurrent theme of the disintegration of an increasingly unstable and interdependent global financial system and civilization of capitalism. It was a story about an unsustainable fragile credit structure ultimately broken by instability of finance and the legacy of Versailles.

Competing Narratives about 1931

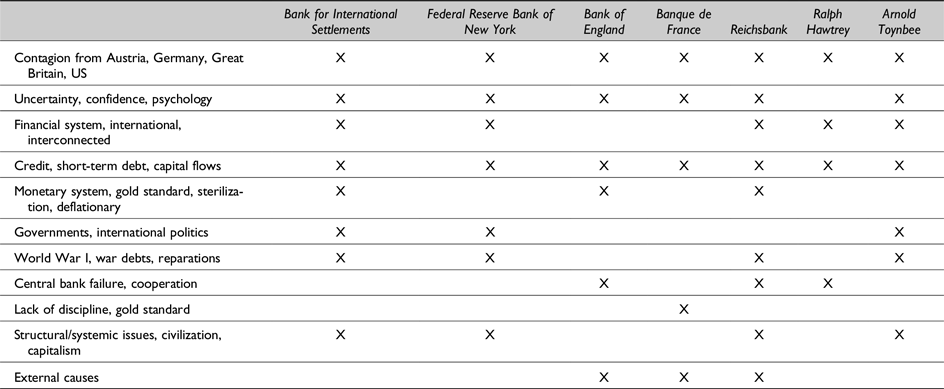

So far, I have examined how a group of contemporaneous central bankers, economists, and a historian made retrospective sense of the dramatic financial and economic events of 1931 they had just lived through. The purpose of their sensemaking through narrative emplotment was to understand and explain what had just happened, to frame a specific view of what caused the crisis, and to use history to produce lessons for the future. My aim is to understand how these narratives gave meaning and coherence to the worst financial crisis the world had ever experienced. All narratives shared some causal claims, but there were also important differences at which point two main competing narratives emerge. In Table 1, I present the most important explanations the seven actors used to give meaning to the European financial crisis of 1931.

Table 1: Causes of the European Financial Crisis of 1931

All actors agreed on the basic chronological and geographical spread of the crisis. Their narratives linked important events the same way and with the same beginning (the Credit-Anstalt failure in Austria) and end (Britain’s departure from gold and the spillover to the US). Except for Hawtrey’s, all narratives pointed to uncertainty, public psychology, and the resulting breakdown of confidence as the cause of contagion. What made the breakdown of confidence and the contagion across borders both possible and so deeply problematic was the changes in the financial architecture since the Great War. Finance had become international, interdependent, short-term-ish, and fragile.

This interconnected “financial machinery,” as Jacobsson called it, featured prominently in most narratives of the crisis. The Bank of England and the Banque de France were the only players who did not point to the role of the financial architecture and its development in causing the financial crisis of 1931; after all, they were busy blaming each other. A clear majority of the examined contemporaneous actors framed the financial crisis as a direct outcome of a fragile international financial system that had come to rely on destabilizing short-term cross-border capital flows and an “enormous superstructure of private credit,” to quote Hans Simon.Footnote 135

Other factors contributing to this systemic fragility were stressed in particular by the Reichsbank but also pointed to by the BIS, the New York Federal Reserve, and Toynbee. These were the role of governments, international politics, and the legacy of the Great War, but first and foremost the reparations. This was an area in which some actors wanted to tread cautiously. The BIS, for example, as an international organization with many stakeholders, noted the problem of international politics and only alluded to the role of war debts and reparations without explicitly mentioning it.

In a competing narrative, the Bank of England and the Reichsbank went all in and blamed France, in particular, for obstructing the rules of the game and for selfishly pursuing its own national interests at the expense of the world economy. The sterilization of gold inflows by France (and the US) put the perceived gold standard mechanism out of order; with France obstructing central bank cooperation (and the Hoover plan), it proved impossible to stop the financial crisis from spreading.

Hawtrey also blamed the crisis on central bank failure but for somewhat different reasons. His “inherent instability of credit” theory of business cycles framed the crisis as a purely monetary phenomenon and blamed central banks for not halting the credit boom.Footnote 136 Then, when the bust and deflation hit, for not reflating the economy. “Bankers are human,” wrote Hawtrey.Footnote 137 But rather than using this insight to include “animal spirits” and uncertainty in his theory, as Keynes, Fisher, and later Minsky and Kindleberger did, he used it to excuse commercial bankers while putting the blame on the central banks for commercial banks’ increasingly risky transnational lending behavior. The role of the changing financial machinery, superstructure of credit, and short-term capital movements were written out of Hawtrey’s narrative.

Sprague disagreed with Hawtrey. Similar to the BIS, he argued that the 1931 crisis and the depression was not a monetary phenomenon, and central banks could not be expected to solve the problems unilaterally. The financial crisis was the result of too much cross-border capital flows and credit granted to bad borrowers, such as the Credit-Anstalt, because of a lack of transparency, or—in today’s words—asymmetric information.

The Banque de France did not buy any of it. The Banque had lived up to the rules of the game and protected the gold standard while other countries and their central banks had not. “Purely technical causes,” for instance, sterilization, had not led to the financial crisis.Footnote 138 Instead, an “artificial policy of easy, cheap money” resulting from a lack of discipline had led to the cycle of boom and bust.Footnote 139 Uncertainty and loss of confidence then caused “the birth and spread of the crisis.”Footnote 140 This was clearly directed at the Bank of England and the Reichsbank, both of which had caved in rather than discipline their economies.

Finally, the BIS, Burgess, and Toynbee, in particular, had concerns about systemic issues and that the “financial machinery” might threaten capitalism. Burgess feared a breakdown of the economic and social orders, and several other actors also stressed structural and systemic fault lines, including the destabilizing influence of an interconnected financial system and short-term capital flows of hot money. Toynbee’s historical perspective saw the crisis as the decline of the British Empire and therefore Western civilization from within. In the end, only the gold standard was brought down, but to most contemporaries that amounted to the same thing.

The central bank failure and the fragile international and interdependent financial system narratives align with one of two grand narrative about the market economy and capitalism.Footnote 141 One narrative is that of neoclassical (and Austrian) economics, in which the economy and the market is in equilibrium and populated by rational, atomistic agents and can take care of itself as long as governments and central banks do not intervene and disturb the incentive structure in the finely tuned “machinery.” In this government failure narrative, crises are exogenous to the market economy and capitalism.Footnote 142

The other grand narrative focuses on an inherent instability in capitalist economies. This approach is often centered on institutional embeddedness, unstable financial markets, and actors prone to group think and animal spirits. Economic and financial instability comes from within the economy operating in “a historical, not a mechanical system.”Footnote 143 This is the endogenous market failure narrative of Keynes, Mitchell, and Minsky. In this narrative, crises are inherent to capitalism, which needs stabilizing intervention to avoid the occasional breakdown.Footnote 144

These two grand narratives see the world through different cultural lenses and serve conflicting ideological positions and interests. They imply different imagined futures and blueprints for decisions, actions, and practices. Enter the concept of performativity. The narrative that comes to dominate at a given point in time, and in particular in cases of meaning loss and radical uncertainty, will also shape the memory, uses of history, and imagined futures. That was what happened in the European financial crisis of 1931 and the Great Depression. This, in turn, will frame how we understand a crisis such as the European financial crisis of 1931 and hence shape imagined futures and related policy responses. It is not surprising that the 1931 crisis led to stricter financial regulations and capital controls from the 1930s and well into the social state of the postwar period.Footnote 145

Enter Historians: Historiography and Lessons from History

The historiography on the topic is massive.Footnote 146 On December 10, 2011, The Economist published an article on the lessons of the 1930s:

In 1931 the failure of Austria’s largest bank, Credit Anstalt, triggered a loss of confidence in the banks that quickly spread [to Germany as] country after country faced capital flight. The effort to defend against bank and currency runs prompted rounds of austerity and plummeting money supplies in pressured economies, helping generate the collapse in output and employment that turned a nasty downturn into a Depression.Footnote 147

The article also mentioned the absence of a lender of last resort, French hostility toward Germany, and the sterilization of gold inflows by the US and France.

The article was uses-of-history in action. The lessons produced corresponded quite well with Bank of England’s “government failure” narrative of the 1931 crisis, which has paradoxically become the dominant narrative. The article’s purpose in 2011 was to use the perceived historical analogy and lessons from the 1930s on the post-2008 financial crisis recession. The magazine invoked Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz’s A Monetary History of the United States, published in 1963, which framed the “Great Contraction” as a monetary phenomenon that could have been avoided had the Federal Reserve acted as a lender of last resort. Friedman and Schwartz did not explicitly refer to Hawtrey’s work, but it is clear that Friedman and probably Schwartz as well built on that tradition.Footnote 148

With time, Friedman and Schwartz’s monocausal monetary explanation silenced other narratives and became the dominant narrative of the Great Depression in the US. Two decades later, Ben Bernanke joined this narrative, arguing for rational man assumptions and blaming “exogenous shocks or policy mistakes” as drivers of the Great Depression.Footnote 149 A few years later, a group of prominent economic historians went all in and argued with supreme hindsight that “what happened in 1931 was that the world saw the consequences of central bankers not understanding central banking.”Footnote 150 In 2002, this central bank failure narrative was elevated to a Federal Reserve-authorized lesson from history when Bernanke gave his much advertised “thanks to you, we won’t do it again” speech at Milton Friedman’s 90th birthday.Footnote 151

Though less monocausal and more contextually embedded, most of the historiography has developed on the shoulders of this framing about government failure and the financial crisis as a monetary phenomenon. In 1992, Harold James explicitly argued that the “assertion that there was too much international capital movement … was highly misleading as analysis.”Footnote 152 Instead, it was the problem of public deficits (i.e., government failure) that led to the crisis of confidence.Footnote 153 Barry Eichengreen notes there is a “mainstream narrative of the Great Depression emphasizing the failure to use monetary and fiscal policies in stabilizing ways.”Footnote 154 Thus, within a decade after the publication of A Monetary History, Stephen V. O. Clarke and Charles Kindleberger agreed that central banks’ failure to act as lenders of last resort was the reason for contagion from Austria to Germany to Great Britain.Footnote 155 Kindleberger further argued that the problem was exacerbated by the lack of a hegemon, another topic of a recent lessons from history article by The Economist.Footnote 156

James and Eichengreen, while each aware of the contemporary context, have followed in the tradition of narrating the crisis as a result of a failure of central bank cooperation and acting as a lender of last resort, while Peter Temin and Eichengreen have expanded the monetary narrative to the deflationary effect of the asymmetrical gold exchange standard.Footnote 157 James argues that the “major failure of the BIS was the mishandling of the Austrian crisis,” and central bank cooperation “proved itself decisively to be a failure” in the 1931 crisis.Footnote 158 Eichengreen agrees that the BIS proved “singularly ineffectual,” but also attributes the perceived lack of central bank cooperation to “domestic political constraints, international political disputes, and incompatible conceptual frameworks.”Footnote 159

Gianni Toniolo, in his history of the BIS, argues that it “made a difference” in the Austrian case, but he ultimately agrees with the too little, too late position.Footnote 160 More recently, James confirms that central bank assistance was “unviable or had failed,” and that France and the US did not want to step in despite their ability to do so. He also suggests that fiscal deficits were an underlying cause of the crisis.Footnote 161 Nathan Marcus, in contrast, argues that central bank cooperation in the Credit-Anstalt crisis was “a successfully coordinated attempt at stemming and insulating a crisis from spreading internationally.”Footnote 162 He turns causality on its head and argues that it was the German crisis of July 1931 that recoiled back to Austria and then onward to the UK. This view contrasts with that of contemporaries; in any case, the end result was the same—the breakdown of the gold exchange standard and the Great Depression.

Finally, a few voices have been more sympathetic to the French point of view while not really changing the central bank failure narrative in relation to 1931. Kenneth Mouré and Robert Boyce both point out that France was in a precarious situation with legitimate security concerns, and that a strong French belief in the “gold standard illusion” meant that their sensemaking differed from that of Great Britain and the US.Footnote 163 In his rather detailed analysis of the 1931 crisis, Boyce shows that, in contrast to the French administration, the Banque de France did in fact cooperate in the rescue efforts.Footnote 164

Then and Now

Several things stand out when comparing the historiography on the European financial crisis of 1931 and the narratives emplotted in the aftermath of the crisis. For one, the Bank of England’s narrative about central bank failure and French obstruction is in some ways the one most aligned with current historiography. Ralph Hawtrey’s monetary “inherent instability of credit” theory also frames stability as the responsibility of central banks and their ability and readiness to break the cycle of boom and bust. Though less popular in 1931, it is the narrative that fits most with later historiography, not least Friedman and Schwartz’s.

Still, one does not have to look long for contemporaneous evidence that central bank failure was not considered an important cause of the financial breakdown. For instance, on June 1, 1931, Merle Cochran, the American Consul in Basle and a close observer of the BIS during the crisis, argued, “If the whole story could be made public, the praise which the B.I.S. would be seen to merit would be even greater.”Footnote 165 A few weeks later, The Economist wrote that Bank of England’s credit to Austria on June 16 provided “substantial relief” and the BIS might “have played a great role in staving off financial disaster.”Footnote 166

Gijsbert W. J. Bruins, a Dutch adviser to the Austrian National Bank, agreed that the Bank of England’s loan to Austria “put the acute crisis to an end.”Footnote 167 The New York Times reported that the BIS had become a “clearinghouse for financial information” and was “continually engaged in promoting the cooperation of central banks.”Footnote 168 And Eleanor Lansing Dulles argued in 1932 that “the quick and efficient arrangement of credits” to the Reichsbank and the Austrian National Bank, among others, was an “outstanding contribution” of the BIS.Footnote 169

From the view of contemporaneous actors, it was crucial to look somewhere else to make sense of and learn from the crisis. In fact, the dominant narrative in the 1930s and well into the Bretton Woods period was the one told by actors whose belief in the financial system and economic theory had suffered a severe blow. To them, the 1931 crisis demonstrated that the international and interdependent financial machinery, massive credit creation, and short-term capital flows were each a fragile and destabilizing part of capitalism.

Their narratives construed a world in which inherent financial instability and uncertainty was a bad mix that led to a breakdown of confidence and to contagion and panic. To the contemporaries examined here, this was a coherent and convincing narrative that made retrospective sense of the crisis and answered the question Fraser dodged on the pier in New York City. It was also a narrative that resonated with the view of the 1931 crisis as a systemic and a potential threat to capitalism. This concern was directly related to the narrative about financial instability, international politics, and the legacy of the Treaty of Versailles.

The rise of this grand narrative of market failure in the wake of the European financial crisis of 1931 was performative. It legitimized and paved the way for exchange controls and restrictions on capital mobility. In addition, it shaped the great transformation of the interwar period and the introduction of the social state after World War II. In 1944, League of Nations economist Ragnar Nurkse pointed to the problem of “hot money” and wrote that “short-term credits … was not a feature that contributed to the stability of the system; in fact, the sudden withdrawal of these credits in the liquidity crisis of 1931 led to the breakdown of the system.”Footnote 170 It was the end of finance capitalism and globalization version 1.0.

Harry Dexter White’s and Keynes’s plans for the Bretton Woods conference were based on a similar market failure worldview. What they learned from the Great Depression was that the global economy and capitalism were not self-regulating, and “exchange rates and international capital movements would both have to be closely controlled and could not be left to the market.”Footnote 171 As Keynes told the House of Lords, “The plan accords to every member government the explicit right to control all capital movements. What used to be a heresy is now endorsed as orthodox.”Footnote 172

For some years, this market failure story was the dominant narrative. It legitimized the idea that capitalism was unstable if left alone, and it marginalized the narrative of government failure. However, as Mary Morgan and Thomas Stapleford argue in “Narrative in Economics,” “the creation of a counternarrative is one common strategy … for reopening an existing narrative explanation.”Footnote 173 That is what Milton Friedman and his compatriots in the Mont Pelerin Society set out to do. In 1953, Friedman dismissed Nurkse’s conclusions that “hot money” and speculation were destabilizing. Speculators in the 1930s were simply anticipating the depreciation of currencies and were proved right, he argued.Footnote 174

From a narrative and performativity perspective, the future that proved speculators right had not yet been shaped when they bet their money. It did not exist. Rather, their anticipation or expectations went through narrative emplotment and prospective sensemaking that itself shaped the imagined future of capital flight and the breakdown of the gold exchange standard in September 1931. But Friedman’s worldview did not allow for a fragile financial system and market failure or the role of narratives. Friedman carried this view into his and Schwartz’s A Monetary History, which relied on the same idea of efficient markets, rational atomistic agents, equilibrium, and stability that came to dominate financial economics in this period.Footnote 175

Friedman and Schwartz’s view was part of a social movement counternarrative shaping the great transformation toward neoliberalism that took place during the stagflation crisis of the 1970s and the radical uncertainty that followed. The great transformation toward neoliberalism gained momentum in the 1970s, and accelerated in the 1980s and 1990s. The endogenous market failure view of financial crises and business cycles was marginalized, and a new dominant narrative based on the exogenous government failure view rose to prominence. As markets were liberalized and globalization version 2.0 caught on, finance once again came to dominate the global economy, this time under the concept of financialization. To quote Lawrence Summers, “Financial markets do not just oil the wheels of economic growth. They are the wheels.”Footnote 176 There was a new dominant narrative in town that, with Piketty, legitimized a new state of affairs.

What happened to the 1931 market failure narrative of the inherent instability of finance, the boom-and-bust cycle, the “enormous superstructure of credit,” and the destabilizing short-term capital movements? And what happened to the concerns about systemic issues and capitalism? It was silenced or marginalized as Bank of England’s, Hawtrey’s, and Friedman and Schwartz’s narratives and neoliberalism came to dominate. Nothing lasts forever, though. The financial crisis of 2008 was a flashback to 1931 as a new wave of radical uncertainty called for sensemaking through narrative emplotment that challenged the narrative of government failure. In their 2009 review of six books on the political economy of finance, Richard Deeg and Mary O’Sullivan argue that the financial crisis has “stimulated a new skepticism about the benefits that a liberalized regime was supposed to bring. … This evidence renders suspect the claims that financial liberalization promotes an efficient allocation of capital across the global economy.”Footnote 177

As we are witnessing the third great transformation in 100 years, the meaning since the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 has once again forced actors and historians to reconsider the past and the present contexts and how they play out. The view that “on the absence of governmentally imposed obstacles, capital flows freely and efficiently to where it can be used most effectively” lost traction while deglobalization became the new buzzword.Footnote 178 In 2014, in contrast to 1992, James now appears to share the concern of the 1931 actors. In 2014, he argued that the interwar period was “more and more dominated by volatile hot money flows”; “in particular, the mediation by large financial institutions of capital movements became profoundly destabilizing” and produced a “systematic vulnerability.”Footnote 179

Conclusions

“Why were capital controls orthodox in 1944, but heretical in 1997?” asks Rawi Abdelal.Footnote 180 The short answer is because the world changes and context matters. In this article, I have argued that sensemaking and narratives played, and always play, a significant role in shaping change and context. Historians’ search for true causality “out there” is a Sisyphean task. Instead, I have given voice to the search by contemporaneous central bankers, economists, and one historian for meaning through retrospective sensemaking and narrative emplotment of the European financial crisis of 1931.

The majority of actors examined here shaped narratives that explained the crisis as a result of an inherently unstable financial system, short-term capital flows, hot money, and the legacy of the Great War. This narrative contributed to shaping the postwar social state and 40 years without financial crises. The result was what mainstream economists call financial repression but which could just as well be called financial stability thanks to government intervention. As the postwar world changed, social and ideological networks regrouped, and the stagflation crisis of the 1970s led to a new search for meaning and the rise to dominance of the government failure narrative. This shaped the great transformation of the 1980s and 1990s and discredited the market failure narrative explanation of the financial crisis of 1931.

In her recent article, Mary O’Sullivan suggests that Friedman and Schwartz’s “ideologically loaded” money-based interpretation marginalized the idea that “a capitalist economy is inherently unstable.”Footnote 181 It was not just an interpretation, however. It was a narrative construction of the causes of the Great Depression. In the postwar years, this counternarrative gradually came to dominate as it replaced the cultural lens and blueprint of contemporaries who blamed an unstable financial system and geopolitical conflicts for the European financial crisis of 1931.

Author Biography

Per H. Hansen is Professor of History at Copenhagen Business School. His most recent publications are There Will Be the Devil to Pay: Central Bankers, Uncertainty and Sensemaking in the European Financial Crisis of 1931 (2025) and Danske Bank. A History of the Bank Through 150 Years (2024, can be downloaded from https://danskebank.com/about-us/our-history).