Introduction

A total of 442 million people worldwide live with diabetes, and type 2 diabetes (T2D) com- prises 90% of the burden (Huffman and Vaccaro, Reference Huffman and Vaccaro2012; World Health Organization, 2016). India is referred to as the ‘Diabetes Capital of the World’ since the International Diabetes Federation has stated that the number of diabetics is expected to rise from 40.9 million to 69.9 million by 2025 (Madaan et al., Reference Madaan, Agrawal, Garg, Sachdeva, Patra and Nair2014). Besides genetic predisposition to diabetes, studies have also shown strong linkage to four key behavioral risk factors, viz., tobacco consumption, physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, and increased use of alcohol (World Health Organization, 2016). Although the pandemic of physical inactivity causes 7% of the burden of disease from diabetes and is attributed to 9% of premature mortality (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Shiroma, Lobelo, Puska, Blair and Katzmarzyk2012), the rising prevalence of diabetes largely driven by physical inactivity among other factors has become a major concern for healthcare in India (World Health Organization, 2014).

Physical activity (PA) not only contributes to prevention or delay in development of other long-term diabetes complications, such as neuropathy, retinopathy, and nephropathy, but also may slow the progression of existing complications (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Alder and Leese2004). Additionally, it also includes positive impact on insulin action, glycemic control, and metabolic abnormalities associated with T2D (Paffenbarger et al., Reference Paffenbarger, Hyde, Wing, Lee, Jung and Kampert1993; Pate et al., Reference Pate, Pratt, Blair, Haskell, Macera, Bouchard, Buchner, Ettinger, Heath, King, Kriska, Leon, Marcus, Morris, Paffenbarger, Patrick, Pollock, Rippe, Sallis and Wilmore1995; Hayes and Kriska, Reference Hayes and Kriska2008). Thus based on clear evidences that PA is essential for the management of T2D (Pan et al., Reference Pan, Li, Hu, Wang, Yang, An, Hu, Lin, Xiao, Cao, Liu, Jiang, Jiang, Wang, Zheng, Zhang, Bennett and Howard1997; Tuomilehto et al., Reference Tuomilehto, Lindstrom, Eriksson, Valle, Hamalainen, Illane-Parikka, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi, Laakso, Louheranta, Rastas, Salminen and Uusitupa2001; Knowler et al., Reference Knowler, Barrett-Connor, Foweler, Hamman, Lachin, Walke and Nathan2002), physicians treating diabetes patients generally advise uptake or increase in PA levels, consumption of a healthy diet, and, if needed, tablets and/or insulin to control blood glucose levels (Lawton et al., Reference Lawton, Ahmad, Hanna, Douglas and Hallowell2006). Thus, for self-management beyond clinical treatment, the onus lies on the patient. However, studies have reported that individuals with diabetes engage in less PA than non-diabetics, live more sedentary lifestyles, and have poor metabolic control (Ford and Herman, Reference Ford and Herman1995; Olivarius et al., Reference Olivarius, Beck-Nielsen, Andreasen, Horder and Pedersen2001; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Reiber and Boyko2002). This perhaps can be attributed to various personal, environmental, psychosocial factors that may interfere with following exercise recommendations, thus making diabetes manage- ment difficult (Huffman and Vaccaro, Reference Huffman and Vaccaro2012). The principles of Alma-Ata declaring ‘Health for All’ though not directly, but indeed signify major importance with context to control and management of diabetes as well (World Health Organization, 1978). Thus, our study aims to assess the pattern and proportion of PA among T2D patients, and the associated enablers and

barriers for management of diabetes in Eastern India. The iden- tified enablers and barriers then in turn can be examined at patient, community, and perhaps even at policy-level for adopting changes for management of the diabetes pandemic.

Methods

A cross-sectional, facility-based study with 341 T2D patients recruited from specialist clinics at a private hospital in Bhuba- neswar, Odisha from June to August 2014 was conducted. The facility selection was done by purposive sampling due to high case load and study feasibility.

Using OpenEpi version 3, the minimum required sample size was calculated as 321 by means of the formula

where n = the required sample size; population size (N) = 100,000; p = hypothesized frequency - 25%; d = confidence limits - 5%; DEFF = design effect - 1.

From the above formula the sample size selected was 289. Considering 10% non-response rate, the sample size calculated was 289/(1 - 0.1). Hence the sample size finalized was 321.

Face-to-face interviews were conducted using a semi- structured questionnaire whose domains included socio- demographic details as well as information related to diabetes, and pattern of PA. Each participant (patient) was included only once in the study during the study period, after obtaining verbal consent for participation.

Data entry and analysis was done with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20, to obtain descriptive sta- tistics. Categorical data were presented as frequency (%). x 2-test was used to identify the association between socio-demographic factors and pattern of PA.

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Indian Institute of Public Health Bhuba- neswar (IIPH-B). Patient anonymity was maintained through assigning of unique codes and data were kept confidential.

Results

Patient demographics and characteristics

As depicted in Table 1, among the 321 T2D patients interviewed, above 60% patients were between 35 and 60 years (n = 196) with mean age of 51 years with 12.8 SD. Similarly, 64% (n = 204/321) were males and proportion ofgraduates was the highest (44%), while 54% contributed to family income. Table 1 also shows 61% patients (n = 195) consumed non-vegetarian food as their primary diet, while 8% reported smoking and 28% consuming smokeless tobacco; 55% patients admitted to family history of diabetes, while 69% patients reported spouse suffering from diabetes. Almost 70% of diabetes patients (69%, n = 220) reported co-morbidities: hypertension, arthritis, gastritis, asthma, and cardiovascular diseases.

Table 1. Patient profile (N = 321)

1 Some patients reported more than one co-morbid condition

Diet and PA

From the entire cohort of T2D patients, 45% (n = 144/321) reported strict control of their diet, 44% patients reported con- trolling their diet moderately, while 11% did not practice any form of diet control.

Further almost 60% patients reported (n = 190/321; 59%) performing PA frequently. These patients were categorized as

active and the remaining 41% were categorized as inactive since they reported of not performing any kind of PA. Gender differ- ences showed that 62% males (n = 127/204) performed PA compared to 54% females (n = 63/117) (data not shown).

Regarding the forms of PA undertaken, as seen in Figure 1, almost 80%, that is, 150 (79%; n = 150/190) patients undertook walking - either morning or any time of the day, 7% reported cycling, 5% each reported gardening and yoga, four patients undertook outdoor sports, and two patients preferred jogging.

Figure 1. Frequently undertaken physical activities as reported by 190 type 2 diabetes patients. The figure depicts various types of physical activities undertaken by the ‘active’ patients in the cohort, with walking as the most preferred activity

Of the 190 ‘active’ patients, three-fourths stated that they started exercising after being diagnosed with diabetes (n = 142/ 190; 75%), while the remaining 25% reported that they were in the habit of exercising before their diabetes diagnosis (n = 48) (data not shown).

Further as seen in Table 2, more than 50% patients reported that they were exercising 2-3 times per week (51%; n = 97/190), while 41% patients were exercising daily, and <5% patients were exercising once a week or less. Duration of PA was variable between patients, with almost two-thirds of patients (59%, n = 112) performing PA for <30 min per session compared to almost similar number of patients that performed PA for more than 30 and 45 min, respectively.

Table 2. Frequency and duration of performing physical activities for diabetes management and control as reported by T2D patients (N = 190)

Perception regarding own weight

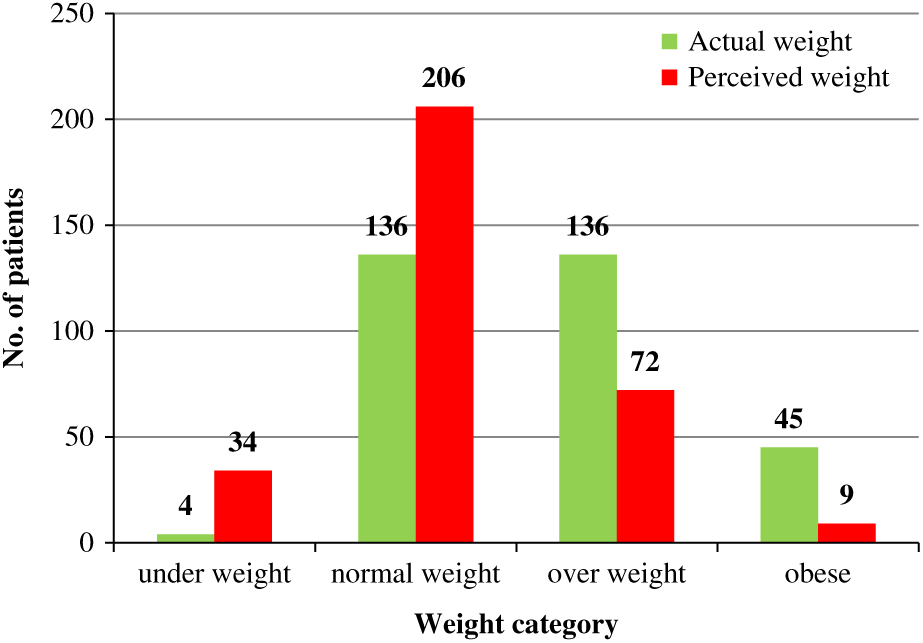

After patients were weighed, each patient was questioned to assume their weight category. Of the total 321 patients, a com- plete mismatch of individual perceived and actual weights was seen. As seen in Figure 2, though only four patients were underweight, 34 patients perceived themselves as being under- weight. Similar observations were seen for normal weight patients (136 versus 206). While for the overweight and obese categories, fewer patients underestimated their actual weight categories (72 versus 136 and 9 versus 45).

Figure 2. Distribution of perceived and actual weight of the 321 type 2 diabetes patients. The figure represents the mismatch of ‘perceived’ versus ‘actual’ weight of the entire cohort. The assumption of weight category by each patient was done prior to measuring individual weight

Barriers and enablers to PA

Barriers and enablers, that is, reasons for not performing or performing PA were captured during the study. These reasons were divided into personal or internal reasons that could be controlled or dependent on the patients (Korkiakangas, Alahuhta and Laitinen, Reference Korkiakangas, Alahuhta and Laitinen2009), while external reasons were related to infrastructure, weather, and so on, or independent (Serour et al., Reference Serour, Alqhenaei, Al-Saqabi, Mustafa and Ben-Nakhi2007). Our study documented both personal and external reasons contributed to enabling patients to perform PAs (Table 3).

Table 3. Reasons for performing physical activity, viz., barriers and enablers

1 Some patients may have given more than one reason as an enabler or barrier

The key personal reasons for barriers of not performing PA included unwillingness by patients, laziness, illness, and tiredness/ discomfort. Among the four patients that cited their age as a barrier for PA - all were above 70 years. Only two patients ‘felt fit’, but did not perform any PA. The most common external barriers included lack of time or workload and other engagements in majority of the patients. Five patients cited lack of safe road and place to exercise as well, as seen in Table 3.

Personal enablers included control of diabetes, ‘to feel good’ and stay active, while external enablers included doctors’ advice and company for exercise featured as prominent enablers. Patients also stated other important reasons for exercising such as controlling other illnesses, including hypertension and joint pain, along with weight management.

Discussion

Our study describes the pattern of PA by T2D patients, and the enablers and barriers that influence their practice and preferences. The study conducted in the private sector of Eastern India adds value to the relative dearth of published data on the topic and the region. Since PA plays an integral part in diabetes management (American Diabetes Association, 2004), findings from the study related to PA by T2D patients are in concordance to the recent studies in India and globally (Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Sun, Cai, Liu and Yang2012; Anjana et al., Reference Anjana, Pradeepa, Das, Mohan, Bhansali, Joshi, Joshi, Dhandhania, Rao, Sudha, Subhashini, Unnikrishnan, Madhu, Kaur, Mohan and Shukla2014).

Personal or internal barriers for self-management of diabetes as stated by patients are among the common reasons as seen in previous studies. These include lack of time, laziness, weakness (Mier et al., Reference Mier, Medina and Ory2007; Korkiakangas et al., Reference Korkiakangas, Alahuhta and Laitinen2009; Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Chin, Cottrell, Duckies, Fernandez, Garces, Keyserling, McMilin, Peters, Samuel-Hodge, Tu, Vu and Fitzpatrick2010; Miller and Marolen, Reference Miller and Marolen2012; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Vos, Lozano, Naghavi, Flaxman, Michaud, Ezzati, Shibuya, Salomon, Abdalla, Aboyans, Abraham, Ackerman, Aggarwal, Ahn, Ali, Alvarado, Anderson, Anderson, Andrews, Atkinson, Baddour, Bahalim, Barker-Collo, Barrero, Bartels, Basáñez, Baxter, Bell, Benjamin, Bennett, Bernabé, Bhalla, Bhandari, Bikbov, Bin Abdulhak, Birbeck, Black, Blencowe, Blore, Blyth, Bolliger, Bonaventure, Boufous, Bourne, Boussinesq, Braithwaite, Brayne, Bridgett, Brooker, Brooks, Brugha, Bryan-Hancock, Bucello, Buchbinder, Buckle, Budke, Burch, Burney, Burstein, Calabria, Campbell, Canter, Carabin, Carapetis, Carmona, Cella, Charlson, Chen, Cheng, Chou, Chugh, Coffeng, Colan, Colquhoun, Colson, Condon, Connor, Cooper, Corriere, Cortinovis, de Vaccaro, Couser, Cowie, Criqui, Cross, Dabhadkar, Dahiya, Dahodwala, Damsere-Derry, Danaei, Davis, De Leo, Degenhardt, Dellavalle, Delossantos, Denenberg, Derrett, Des Jarlais, Dharmaratne, Dherani, Diaz-Torne, Dolk, Dorsey, Driscoll, Duber, Ebel, Edmond, Elbaz, Ali, Erskine, Erwin, Espindola, Ewoigbokhan, Farzadfar, Feigin, Felson, Ferrari, Ferri, Fèvre, Finucane, Flaxman, Flood, Foreman, Forouzanfar, Fowkes, Fransen, Freeman, Gabbe, Gabriel, Gakidou, Ganatra, Garcia, Gaspari, Gillum, Gmel, Gonzalez-Medina, Gosselin, Grainger, Grant, Groeger, Guillemin, Gunnell, Gupta, Haagsma, Hagan, Halasa, Hall, Haring, Haro, Harrison, Havmoeller, Hay, Higashi, Hill, Hoen, Hoffman, Hotez, Hoy, Huang, Ibeanusi, Jacobsen, James, Jarvis, Jasrasaria, Jayaraman, Johns, Jonas, Karthikeyan, Kassebaum, Kawakami, Keren, Khoo, King, Knowlton, Kobusingye, Koranteng, Krishnamurthi, Laden, Lalloo, Laslett, Lathlean, Leasher, Lee, Leigh, Levinson, Lim, Limb, Lin, Lipnick, Lipshultz, Liu, Loane, Ohno, Lyons, Mabweijano, MacIntyre, Malekzadeh, Mallinger, Manivannan, Marcenes, March, Margolis, Marks, Marks, Matsumori, Matzopoulos, Mayosi, McAnulty, McDermott, McGill, McGrath, Medina-Mora, Meltzer, Mensah, Merriman, Meyer, Miglioli, Miller, Miller, Mitchell, Mock, Mocumbi, Moffitt, Mokdad, Monasta, Montico, Moradi-Lakeh, Moran, Morawska, Mori, Murdoch, Mwaniki, Naidoo, Nair, Naldi, Narayan, Nelson, Nelson, Nevitt, Newton, Nolte, Norman, Norman, Donnell, Hanlon, Olives, Omer, Ortblad, Osborne, Ozgediz, Page, Pahari, Pandian, Rivero, Patten, Pearce, Padilla, Perez-Ruiz, Perico, Pesudovs, Phillips, Phillips, Pierce, Pion, Polanczyk, Polinder, Pope, Popova, Porrini, Pourmalek, Prince, Pullan, Ramaiah, Ranganathan, Razavi, Regan, Rehm, Rein, Remuzzi, Richardson, Rivara, Roberts, Robinson, De Leòn, Ronfani, Room, Rosenfeld, Rushton, Sacco, Saha, Sampson, Sanchez-Riera, Sanman, Schwebel, Scott, Segui-Gomez, Shahraz, Shepard, Shin, Shivakoti, Singh, Singh, Singh, Singleton, Sleet, Sliwa, Smith, Smith, Stapelberg, Steer, Steiner, Stolk, Stovner, Sudfeld, Syed, Tamburlini, Tavakkoli, Taylor, Taylor, Taylor, Thomas, Thomson, Thurston, Tleyjeh, Tonelli, Towbin, Truelsen, Tsilimbaris, Ubeda, Undurraga, van der Werf, van Os, Vavilala, Venketasubramanian, Wang, Wang, Watt, Weatherall, Weinstock, Weintraub, Weisskopf, Weissman, White, Whiteford, Wiebe, Wiersma, Wilkinson, Williams, Williams, Witt, Wolfe, Woolf, Wulf, Yeh, Zaidi, Zheng, Zonies, Lopez, AlMazroa and Memish2012; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Sun, Cai, Liu and Yang2012). These internal barriers are individuals choices and attitude that need to be identified in order to change. Thus interventions must be planned in order for patients to first assess their areas and readiness to change, and then accordingly motivate the patient based on their acceptance of the disease and their intention to change (Fort et al., Reference Fort, Alvarado-Molina, Pena, Mendoza Montano, Murrillo and Martinez2013). Furthermore, our study highlighted important enablers such as social support by means of family and friend’s suggestions along with company for exercise, which plays an important role in self-management of diabetes. The presence of social support in the form of emotional encouragement can also help overcome laziness, tiredness, and so on, which in turn can be improved by PA. These support systems have shown to improve diabetes control, knowledge, and psychosocial func- tioning (Van Dam et al., Reference Van Dam, Van Der Horst, Knoops, Ryckman, Crebolder and Van Der Borne2005), similar to multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis patients (Aghaei et al., Reference Aghaei, Karbandi, Gorji, Golkhatmi and Alizadeh2016; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Zhao, Xue, Fu, Liu, Zhang, Huang and Zhang2017).

Higher number of males were ‘active’ than females, with no association between gender and PA uptake. A total of 27 female patients stated that ‘they had enough work at home and felt was comparable to physical activity, hence did not perform any additional PA. Similar gender-based barriers have also been reported in other studies (Lawton et al., Reference Lawton, Ahmad, Hanna, Douglas and Hallowell2006; Mier, Medina and Ory, Reference Mier, Medina and Ory2007; Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Chin, Cottrell, Duckies, Fernandez, Garces, Keyserling, McMilin, Peters, Samuel-Hodge, Tu, Vu and Fitzpatrick2010).

The findings of our study showed enabling factors that motivated patients to participate in regular PA, which included ‘doctor’s advice’ as cited by 55 patients, while one patient com- plained lack of knowledge of exercise as a barrier. These findings further strengthen the need for counseling by treating physicians during routine visits that perhaps could also be tailored according to patients’ requirements (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Reiber and Boyko2002; Van Dam et al., Reference Van Dam, Van Der Horst, Knoops, Ryckman, Crebolder and Van Der Borne2005; Haskell et al., Reference Haskell, Lee, Pate, Powell, Blair, Franklin, Macera, Heath, Thompson and Bauman2007). The harnessing of physicians to facilitate counseling recommends an imperative need for engagement of private sector providers as well as strengthening capacity of physicians across sectors.

In concordance to the principles of the Alma-Ata declaration, at primary care level for early control of a lifestyle disorder such as diabetes, adopting strategies that include inter-sectoral colla- boration (of providers) and community engagement are highly recommended. Thus for achieving Health for All, use of patient- centered models for diabetes care such as the modified 3 x 3P rubric (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Chin, Cottrell, Duckies, Fernandez, Garces, Keyserling, McMilin, Peters, Samuel-Hodge, Tu, Vu and Fitzpatrick2010) along with encouragement for weight monitoring and control by use of wearable technology (Chiauzzi, Rodarte and DasMahapatra, 2015) needs to be considered, especially for a developing country like India.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the patients who participated in this study. They also thank the physicians for their support toward data collection.

Financial support

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The study was done in partial fulfillment toward the Post Graduate Diploma Program in Public Health Management.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.