Introduction

Self-harm, defined in this study as intentionally hurting oneself in any way with or without suicidal intent, is a global public health concern. There is evidence that rates of self-harm are rising, and it is one of the strongest predictors of later suicide (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Hall, Simkin, Bale, Bond, Codd and Stewart2003; McManus et al., Reference McManus, Gunnell, Cooper, Bebbington, Howard, Brugha and Appleby2019). Understanding the causal antecedents of self-harm is important in reducing risk and developing effective treatments. One of the strongest risk factors for self-harm is experiencing adversity early in life (Björkenstam, Kosidou, & Björkenstam, Reference Björkenstam, Kosidou and Björkenstam2016, Reference Björkenstam, Kosidou and Björkenstam2017; Cha et al., Reference Cha, Franz, Guzmán, Glenn, Kleiman and Nock2018; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart, Mikton and Dunne2017). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are commonly conceptualised as indicators of abuse, child maltreatment or household dysfunction (Björkenstam et al., Reference Björkenstam, Kosidou and Björkenstam2016, Reference Björkenstam, Kosidou and Björkenstam2017; Dube, Felitti, Dong, Giles, & Anda, Reference Dube, Felitti, Dong, Giles and Anda2003), including sexual, physical and emotional abuse as well as parental psychopathology and witnessing domestic violence. Studies exploring the role of ACEs in relation to health outcomes commonly consider the multiple types of adversity an individual has experienced, rather than focussing on individual adversities (Enns et al., Reference Enns, Cox, Afifi, De Graaf, Ten Have and Sareen2006). Because adversities rarely occur in isolation and some, such as sexual abuse, are less common, it is difficult to disentangle the role of an individual adversity on child outcomes in population-based samples.

Understanding the pathways that link ACEs to an increased risk of later self-harm could improve the identification of those most at risk and may lead to novel intervention targets. However, the mechanisms linking ACEs to self-harm in adolescence and adulthood are unclear (Cha et al., Reference Cha, Franz, Guzmán, Glenn, Kleiman and Nock2018). One possible mechanism is through an earlier onset of puberty in children exposed to ACEs, since early puberty is associated with an increased risk of self-harm in adolescence and young adulthood in both sexes (Cha et al., Reference Cha, Franz, Guzmán, Glenn, Kleiman and Nock2018; Deng et al., Reference Deng, Tao, Wan, Hao, Su and Cao2011; Larsson & Sund, Reference Larsson and Sund2008; Michaud, Suris, & Deppen, Reference Michaud, Suris and Deppen2006; Roberts, Fraser, Gunnell, Joinson, & Mars, Reference Roberts, Fraser, Gunnell, Joinson and Mars2020; Wichstrøm, Reference Wichstrøm2000). There is some evidence that childhood adversity is associated with an earlier age at onset of puberty in both females and males (Henrichs et al., Reference Henrichs, McCauley, Miller, Styne, Saito and Breslau2014; Lei, Beach, & Simons, Reference Lei, Beach and Simons2018; Mendle, Reference Mendle2014) but empirical findings are mixed (Zhang, Zhang, & Sun, Reference Zhang, Zhang and Sun2019). Adverse experiences that have been found to be associated with early pubertal timing in females include physical abuse, sexual abuse, parental mental illness, parent drinking, father absence, parental unemployment, frequent relocation and family violence (Arim, Tramonte, Shapka, Dahinten, & Willms, Reference Arim, Tramonte, Shapka, Dahinten and Willms2011; Barrios et al., Reference Barrios, Sanchez, Nicolaidis, Garcia, Gelaye, Zhong and Williams2015; Bogaert, Reference Bogaert2005; Boynton-Jarrett et al., Reference Boynton-Jarrett, Wright, Putnam, Hibert, Michels, Forman and Rich-Edwards2013; Boynton-Jarrett & Harville, Reference Boynton-Jarrett and Harville2012; Clutterbuck, Adams, & Nettle, Reference Clutterbuck, Adams and Nettle2015; Henrichs et al., Reference Henrichs, McCauley, Miller, Styne, Saito and Breslau2014; Hulanicka, Gronkiewicz, & Koniarek, Reference Hulanicka, Gronkiewicz and Koniarek2001; Kelly, Zilanawala, Sacker, Hiatt, & Viner, Reference Kelly, Zilanawala, Sacker, Hiatt and Viner2017; Li, Denholm, & Power, Reference Li, Denholm and Power2014; Magnus et al., Reference Magnus, Anderson, Howe, Joinson, Penton-Voak and Fraser2018; Romans, Martin, Gendall, & Herbison, Reference Romans, Martin, Gendall and Herbison2003). However, studies have also reported a later age at menarche (AAM) for females affected by abuse, domestic violence, family conflict and maternal alcohol abuse (Boynton-Jarrett et al., Reference Boynton-Jarrett, Wright, Putnam, Hibert, Michels, Forman and Rich-Edwards2013; Boynton-Jarrett & Harville, Reference Boynton-Jarrett and Harville2012; Li et al., Reference Li, Denholm and Power2014). In males, there is evidence that low parental education and father absence (Arim et al., Reference Arim, Tramonte, Shapka, Dahinten and Willms2011; Bogaert, Reference Bogaert2005) are associated with earlier age of puberty.

Mechanisms and intervention potential

The developmental origins of health and disease theoretical framework proposes that environmental stress impacts the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to elevated levels of stress hormones that are involved in the regulation of pubertal timing (Belsky & Shalev, Reference Belsky and Shalev2016). HPA axis dysregulation and other stress-related physiological and epigenetic pathways have also been found to be associated with a greater risk of suicide and self-harm (Berardelli et al., Reference Berardelli, Serafini, Cortese, Fiaschè, O'Connor and Pompili2020; Turecki & Brent, Reference Turecki and Brent2016).

Understanding if there are biological pathways that underpin the relationship between childhood adversity and self-harm will increase our understanding of factors that contribute to the aetiology of self-harm. Understanding this, and the relative contributions of biological and psychological mediators will highlight potential targets for psychosocial interventions. For example, early pubertal timing may lead to self-harm via adolescent social maladjustment, where those with early pubertal timing may associate with older peers, engaging in more risky behaviours such as alcohol use sooner than their same-age peers, increasing risk of self-harm (Patton et al., Reference Patton, Hemphill, Beyers, Bond, Toumbourou, McMorris and Catalano2007). Interventions could promote adaptive coping skills, social negotiation skills, assertiveness and emotion regulation. The timing and quality of puberty education in schools (an ideal setting for such an intervention) could be improved to ensure those who have an earlier puberty are supported adequately; positive psychosocial adjustment at this point could reduce risk of later self-harm. Psychosocial interventions may also intervene on the pathways from ACEs to pubertal timing by using stress-tolerance techniques or by supporting families and children to maintain good mental health in the face of adversity and to reduce children's experiences of adversity.

Given these hypothesised common causal mechanisms from adversity to earlier onset of puberty and self-harm, we investigated whether pubertal timing lies on the causal pathway from ACEs to self-harm. Specifically, we aimed to assess whether pubertal timing mediated the association between the cumulative types of adversity a young person has experienced and risk of self-harm in adolescence and young adulthood, using data from a longitudinal birth cohort. We hypothesised that ACEs would be associated with earlier pubertal timing (measured as a continuous variable), and that pubertal timing would lie on the causal pathway between adversity and self-harm.

The current study

To our knowledge, there is no published research investigating whether early pubertal timing is a mediator of the relationship between ACEs and risk of self-harm. We used data from a large UK birth cohort to investigate the relationship between ACEs (assessed from birth to 9 years), pubertal timing and self-harm, and we specifically examined whether early pubertal timing is a mediator of the relationship between ACEs and self-harm at 16 and 21 years.

Methods

Sample

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) is a birth cohort that originally recruited pregnant women in what was previously the county of Avon, UK with expected dates of delivery 1st April 1991 to 31st December 1992. We included individuals from the initial enrolment sample: the initial number of pregnancies was 14 541. Of these, there were a total of 14 676 foetuses, resulting in 14 062 live births and 13 988 children who were alive at 1 year of age (Boyd et al., Reference Boyd, Golding, Macleod, Lawlor, Fraser, Henderson and Davey Smith2013; Fraser et al., Reference Fraser, Macdonald-Wallis, Tilling, Boyd, Golding, Davey Smith and Lawlor2012; Northstone et al., Reference Northstone, Lewcock, Groom, Boyd, Macleod, Timpson and Wells2019). Twins are usually highly similar due to growing up in the same environment and therefore their data are not independent. Including twins in our study sample may therefore inflate any population-level association found. To mitigate this risk, we excluded the second-born of each twin pair. The study sample comprised of those who had data on any of the putative pubertal timing mediators (N = 6689): multiple imputation using chained equations was utilised to impute missing data on exposure, outcome and covariates. Data were collected via questionnaires and research clinics. The ALSPAC study website contains details of all the data that are available through a fully searchable data dictionary and variable search tool (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/researchers/our-data/).

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the ALSPAC Ethics and Law Committee and the Local Research Ethics Committees.

Measures

Childhood adversity

Nine domains of childhood adversity from birth to 9 years old were assessed using parent and child reports (Houtepen, Heron, Suderman, Tilling, & Howe, Reference Houtepen, Heron, Suderman, Tilling and Howe2018; Russell et al., Reference Russell, Heron, Gunnell, Ford, Hemani, Joinson and Mars2019). We assessed adversity up to age 9 to ensure that our exposure variable preceded onset of menarche (only 12 participants reported onset of menarche prior to age 9 in the study sample). These domains of adversity have been widely used in other studies of childhood adversity (Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner, & Hamby, Reference Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner and Hamby2013; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart, Mikton and Dunne2017) and include physical, sexual or emotional abuse, parental mental health problems or suicide attempt, child being bullied, violence between parents, parental separation, parental criminal conviction and parental substance use (online Supplementary Table 1). Exposure to adversity was conceptualised as a continuous score of the number of different adversities experienced (range 0–9), as existing evidence shows a dose–response relationship between the number of types of adversity experienced and a range of negative health outcomes in later life (Anda et al., Reference Anda, Felitti, Bremner, Walker, Whitfield, Perry and Giles2006; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart, Mikton and Dunne2017).

Self-harm

At age 16, young people provided self-reports of their lifetime history of self-harm in response to the question ‘Have you ever hurt yourself on purpose in any way (e.g. by taking an overdose of pills, or by cutting yourself)?’

Mediators: pubertal timing

We used age at peak height velocity (aPHV) and AAM as indicators of pubertal timing. aPHV is an objectively measured indicator of pubertal timing in both sexes that indicates the age at which the adolescent ‘growth spurt’ is at its most rapid (Demirjian, Buschang, Tanguay, & Patterson, Reference Demirjian, Buschang, Tanguay and Patterson1985). The distribution of aPHV is normal in the general population and correlates well with other measures of pubertal timing (e.g. 0.79 with AAM in ALSPAC) (Demirjian et al., Reference Demirjian, Buschang, Tanguay and Patterson1985; Marshall & Tanner, Reference Marshall and Tanner1969, Reference Marshall and Tanner1970). aPHV was calculated from multiple height measurements recorded at research clinics across childhood and adolescence using Superimposition by Translation and Rotation (SITAR), a mixed effects growth curve analysis described in detail elsewhere (Frysz, Howe, Tobias, & Paternoster, Reference Frysz, Howe, Tobias and Paternoster2018).

AAM was assessed using data from nine postal questionnaires relating to pubertal development that were administered approximately annually from age 8 to 17. The questionnaires asked whether menstruation had started, and if so at what age (in years and months). The first-reported AAM was used to minimise recall error (Joinson, Heron, Araya, & Lewis, Reference Joinson, Heron, Araya and Lewis2013).

Confounders and covariates

Participant sex, father absence during pregnancy, maternal education, housing tenure, material hardship and financial difficulties were treated as confounders of all paths in our models. We included body mass index (BMI) at age 9 as an intermediate confounder, because it could potentially be affected by childhood adversity and causally influence pubertal timing and self-harm.

Sensitivity analyses

We examined associations with four secondary dichotomous outcomes: lifetime history of self-harm with suicidal intent at age 16, multiple self-harm in past year (i.e. reported >1 episode) at age 16, self-harm at age 21 and lifetime history of self-harm with suicidal intent at age 21. We considered suicidal intent to be present if young people indicated that they ‘have ever seriously wanted to kill [themselves] on any occasion where [they] have hurt [themselves]’ or the ‘last time [they] hurt themselves it was because [they] wanted to die’. Self-harm and suicidal intent at age 21 were measured with the same questions asked at age 16. We conducted sensitivity analyses to explore whether effects were independent of psychopathology by excluding those with a psychiatric disorder assessed using the Development and Wellbeing Assessment (DAWBA) at age 15. DSM-IV diagnoses were generated using information from parents and young people via a computer algorithm (Goodman, Ford, Richards, Gatward, & Meltzer, Reference Goodman, Ford, Richards, Gatward and Meltzer2000; Goodman, Heiervang, Collishaw, & Goodman, Reference Goodman, Heiervang, Collishaw and Goodman2011). The primary results presented are from the imputed sample (N = 6698) with complete case results presented in the online Supplementary material.

Analysis

We treated aPHV and AAM (in months) as continuous variables. We used multiple imputation by chained equations (separately for males and females; 50 imputations) in order to mitigate the potential for bias due to missing data (N = 6698), and compared this with results obtained from analyses in complete case data (n = 2373). Results were largely consistent across the imputed and complete case samples.

We conducted mediation analyses using structural equation modelling to implement Poisson regression (because self-harm was not a rare outcome) with robust standard errors, partitioning effects into direct and indirect effects using the products of coefficients approach (conducted using the gsem package in Stata v15). In complete case data, we used bootstrapping (n reps = 1000) to generate bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs). In the aPHV model, there was no interaction between sex and aPHV (p > 0.1), therefore we included males and females in a single model, with sex as a covariate. We ran sensitivity analyses to explore whether findings were consistent when excluding those with psychiatric disorder at age 15, and for the secondary outcomes (self-harm with suicidal intent at age 16, multiple self-harm in past year at age 16, self-harm at age 21 and self-harm with suicidal intent at age 21).

Results

Description of sample

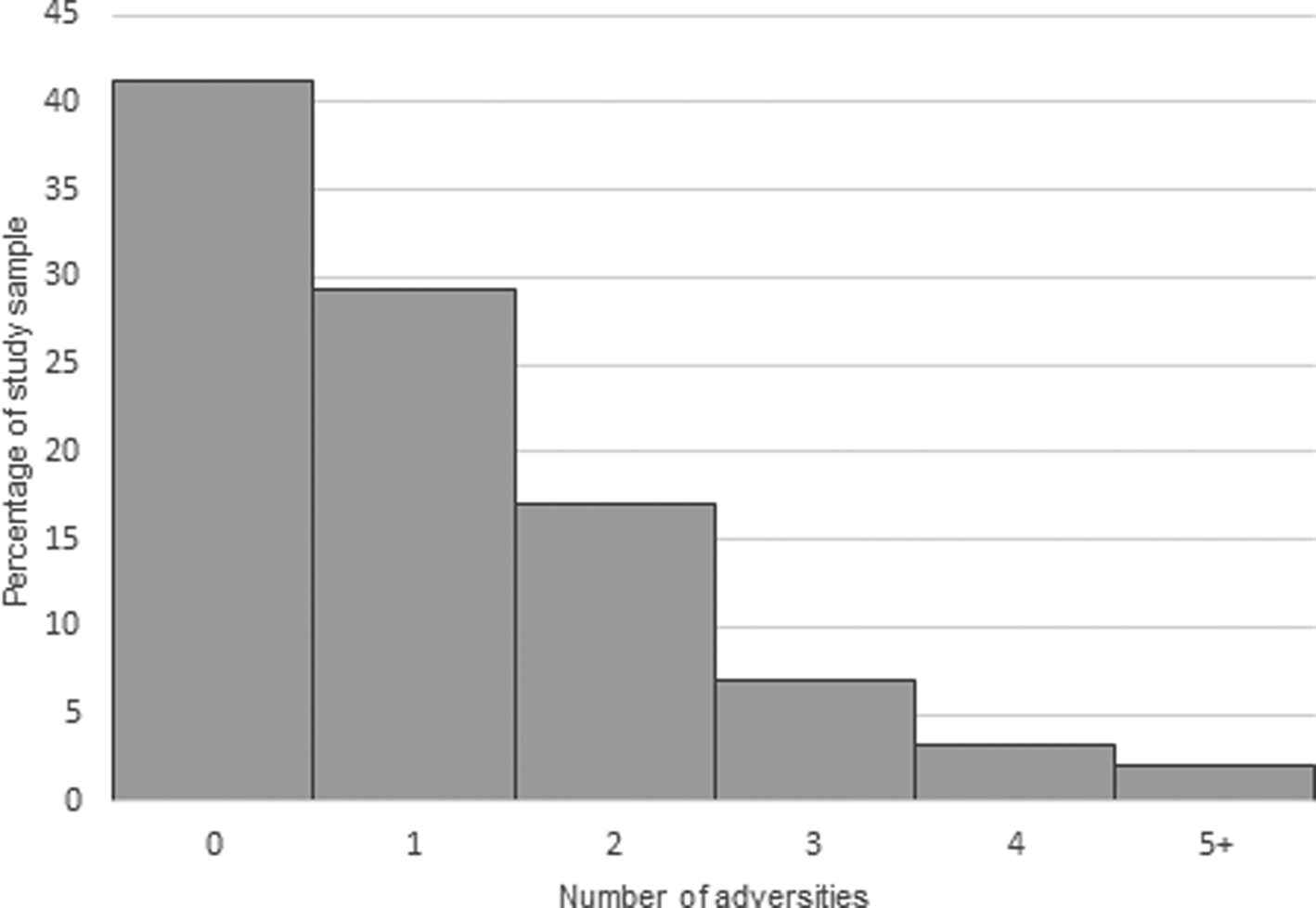

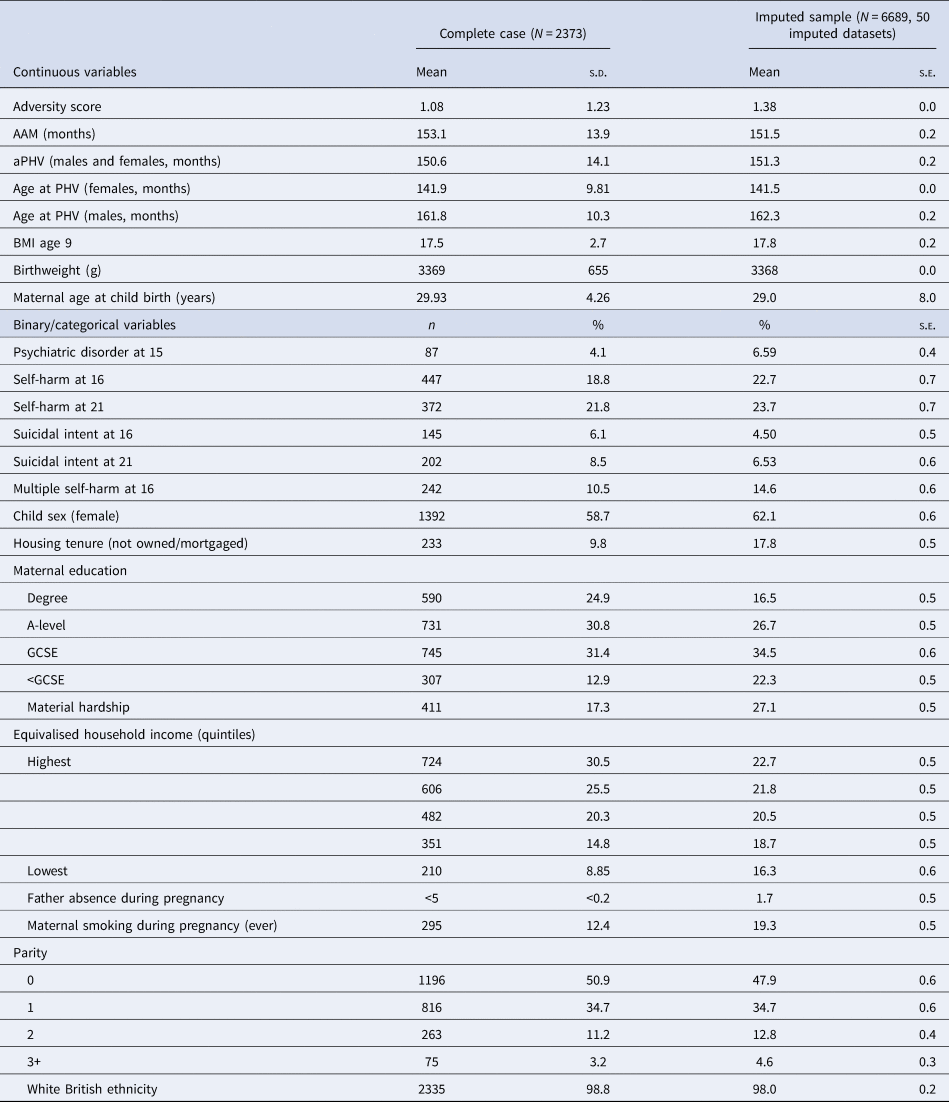

Descriptive statistics for the imputed sample and complete cases are shown in Table 1. The study sample comprised of young people from more socioeconomically advantaged families compared with those not included in the study sample (online Supplementary Table 2). Of the nine adversities measured, parental mental health problems or suicide attempt were the most frequently experienced (39.3%), followed by parental separation and violence between parents (21.9% and 21.2% respectively; online Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). Figure 1 shows the number of adversities experienced across the sample, and online Supplementary Figs 1–4 show the distribution of pubertal timing measures by gender, as well as plots indicating the mean aPHV by number of ACEs and gender.

Fig. 1. Number of ACEs per child (complete case data N = 2373).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics: complete case and imputed sample

Mediation results

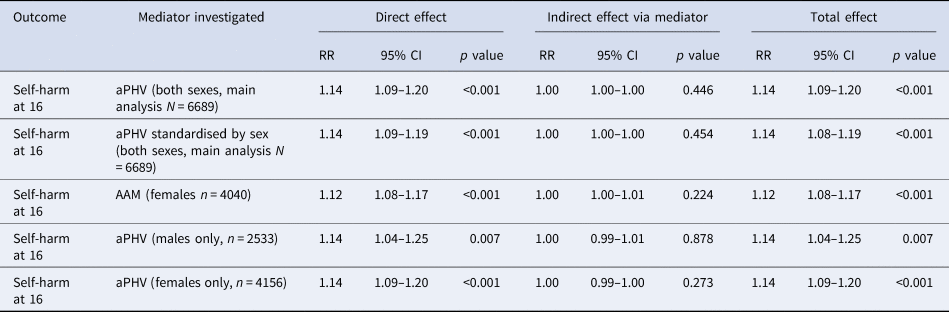

There was robust evidence for direct effects of childhood adversity on risk of self-harm. For every additional type of adversity experienced; participants had on average a 12–14% increased risk of self-harm by age 16 (Table 2). The relative risk (RR) for the direct effect was 1.14 (95% CI 1.09–1.20) in the model with aPHV as the mediator, while in the model with AAM as the mediator the RR was 1.12 (95% CI 1.08–1.17). RRs were stronger for direct effects when outcomes were restricted to those who self-harmed with suicidal intent at 16 or 21 years. There was no evidence that pubertal timing (assessed using aPHV or AMM) mediated the association between childhood adversity and self-harm (indirect effect RR 1.00, 95% CI 1.00–1.00 for aPHV and RR 1.00, 95% CI 1.00–1.01 for AAM). On examining model results, we found evidence for associations between pubertal timing (aPHV and AAM) and self-harm, and between childhood adversity and self-harm. There was no evidence, however, of an association between childhood adversities and pubertal timing. RR estimates were marginally larger for complete case data, with wider CIs (online Supplementary Table 5).

Table 2. Results of mediation analyses assessing the relationship between number of adversities experienced by age 9, pubertal timing and later self-harm

RR: relative risk; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval. RRs can be interpreted as the average percentage increase in risk (if >1) of the outcome for each additional type of adversity experienced prior to age 9 i.e. for row 1 direct effect, for every additional type of adversity experienced, participants were on average 14% more likely to report self-harm at age 16.

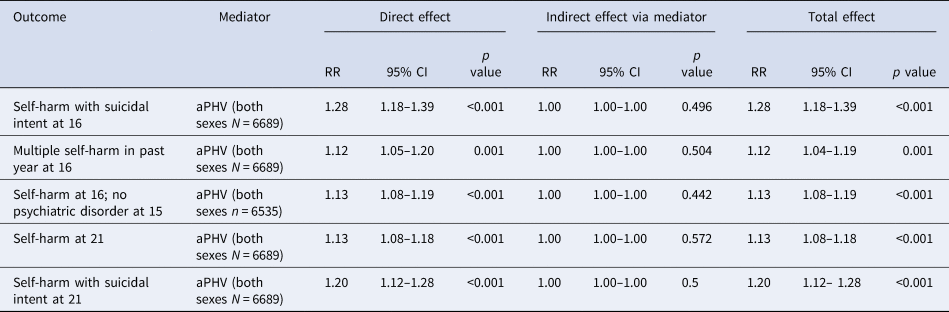

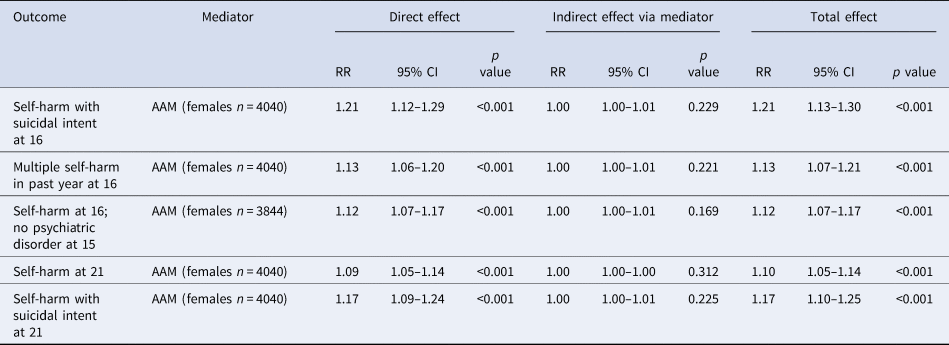

Sensitivity analyses

In sensitivity analyses utilising outcomes of self-harm at age 21, self-harm with suicidal intent at ages 16 and 21, past-year multiple self-harm at age 16 and excluding those with psychiatric disorder at age 15, results for each mediator were consistent with the main findings (Tables 3 and 4). The direct effects were larger for self-harm with suicidal intent at 16 and 21 (aPHV model: RR at age 16 = 1.28, 95% CI 1.18–1.39; RR at age 21 = 1.20, 95% CI 1.12–1.28).

Table 3. Sensitivity analyses results of mediation analyses assessing the relationship between the number of adversities experienced by age 9, aPHV and later self-harm

RR: relative risk; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval. RRs can be interpreted as the average percentage increase in risk (if >1) of the outcome for each additional type of adversity experienced prior to age 9 i.e. for row 1 direct effect, for every additional type of adversity experienced, participants were on average 28% more likely to report self-harm with suicidal intent at age 16.

Table 4. Sensitivity analyses results of mediation analyses assessing the relationship between the number of adversities experienced by age 9, AAM and later self-harm

RR: relative risk; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval. RRs can be interpreted as the average percentage increase in risk (if >1) of the outcome for each additional type of adversity experienced prior to age 9 i.e. for row 1 direct effect, for every additional type of adversity experienced, participants were on average 21% more likely to report self-harm with suicidal intent at age 16.

Discussion

We found that childhood adversity and early timing of puberty are independent risk factors for later self-harm in both males and females. There was no evidence in this study for an association between total childhood adversities and pubertal timing, and no mediating effect of early pubertal timing on the relationship between childhood adversity and self-harm. Our findings are consistent with a large study (n = 14 000 adolescents) that found no evidence for a mediating effect of pubertal timing on the relationship between childhood adversity and depressive symptoms in adolescence (Strong, Tsai, Lin, & Cheng, Reference Strong, Tsai, Lin and Cheng2016). Just over one-in-five young people in our sample reported self-harm at age 16 (18.8% in complete case data and 22.7% in the imputed data). This is higher than the prevalence of self-harm in adolescents aged 13–18 in the community reported in a recent meta-analysis (16.9%, 95% CI 15.1–18.9), although estimates vary across samples due to differences in population and methodology (Gillies et al., Reference Gillies, Christou, Dixon, Featherston, Rapti, Garcia-Anguita and Christou2018). The prevalence of ACEs in our sample (58.7% reported at least one ACE) was consistent with estimates from a recent meta-analysis of over 250 000 participants and in a similar UK-based cohort assessing ACEs from age 0 to 5 years (57% and 50% respectively reported at least once ACE), while 5.0% in our sample reported four or more ACEs, compared with 13% with at least four ACEs in the meta-analysis and 1.4% in the Millennium Cohort (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart, Mikton and Dunne2017; Straatmann et al., Reference Straatmann, Lai, Law, Whitehead, Strandberg-Larsen and Taylor-Robinson2020). We measured ACEs between the ages of 0 and 9 years whereas the meta-analysis largely includes data from adult samples. Differences in socioeconomic disadvantage across populations might also explain the difference in those accumulating more than four ACEs (Straatmann et al., Reference Straatmann, Lai, Law, Whitehead, Strandberg-Larsen and Taylor-Robinson2020). Our estimates of the distribution of AAM and peak height velocity are also in line with other studies (e.g. Granados, Gebremariam, & Lee, Reference Granados, Gebremariam and Lee2015; Parent et al., Reference Parent, Teilmann, Juul, Skakkebaek, Toppari and Bourguignon2003).

There are currently fewer studies of adversity and pubertal timing in boys than girls, although research in this area is increasing (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Hall, Simkin, Bale, Bond, Codd and Stewart2003; Lei et al., Reference Lei, Beach and Simons2018; Mendle, Reference Mendle2014; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Zhang and Sun2019). Existing studies reporting null findings may also be subject to publication bias. Regarding females, our study found no association between cumulative adversity and AAM. A study of the ALSPAC mothers' cohort found that only sexual abuse was associated with earlier menarche (Magnus et al., Reference Magnus, Anderson, Howe, Joinson, Penton-Voak and Fraser2018). One study found evidence for differing dose–response relationships between several forms of abuse with AAM, with sexual and physical abuse predicting earlier AAM, and physical abuse also being associated with later AAM (Boynton-Jarrett et al., Reference Boynton-Jarrett, Wright, Putnam, Hibert, Michels, Forman and Rich-Edwards2013). Exposure to specific types of adversity may also impact differentially on physiological development during puberty, with findings for sexual abuse being particularly strong (Zabin, Emerson, & Rowland, Reference Zabin, Emerson and Rowland2005). Puberty and developmental maturational processes are largely controlled by biological systems, however there is evidence that environmental factors such as diet, nutrition and the presence of a step-father in the household (Zabin et al., Reference Zabin, Emerson and Rowland2005) contribute to pubertal timing. We controlled for BMI and father absence during pregnancy, however there may be other factors that were not accounted for in our models.

Strengths and limitations

We utilised data from a large sample of young people, who are broadly representative of the UK population although slightly more socioeconomically advantaged and less ethnically diverse. The most disadvantaged participants were more likely to drop-out (Wolke et al., Reference Wolke, Waylen, Samara, Steer, Goodman, Ford and Lamberts2009), but our findings were similar across imputed and complete case analyses. The longitudinal nature of the mediation analysis is a key strength of the study design, allowing us to draw inferences about the direction of effects with measures of adversity occurring before puberty, and pubertal timing prior to measures of self-harm. We used an objective measure of pubertal timing, aPHV, as our primary mediator. This was based on repeated measures of height taken during research clinics, rather than self-reported height, and allowed us to investigate associations for males as well as females. Males are underrepresented in research on puberty, and much of the existing studies that link adversity and puberty, and puberty and self-harm, are based on females. Our estimates of prevalence of ACEs and self-harm were in line with other studies, which gives confidence in the potential generalisability of our findings.

There are limitations to our study; there may be bias in reporting of adversity, as much of the information was collected from questionnaires to parents. The outcome data are now 10 years old, and rates of self-harm are now higher than 10 years ago (McManus et al., Reference McManus, Gunnell, Cooper, Bebbington, Howard, Brugha and Appleby2019; Sadler et al., Reference Sadler, Vizard, Ford, Goodman, Goodman and McManus2020). Parents may under-report adversities due to perceived stigma or social desirability. However, estimates of adversities in ALSPAC are in line with similar studies. Similarly, self-harm was self-reported by individuals, and the prevalence is similar to other non-clinical samples. We did not account for the severity of adversities in our model, beyond including multiple forms of adversity. It is likely that exposure to severe and repeated adversity or multiple adversities will have differential impacts on pubertal timing, compared with brief exposure to one adversity. This was not adequately captured by our measures and future work could explore this further. We utilised a cumulative index of number of adversities experienced, which is common in the scientific literature as exposure to a range of ACEs has been shown to have associations with a range of health outcomes across the lifecourse (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart, Mikton and Dunne2017) and because ACEs do not often occur in isolation it is difficult to disentangle the impact of a single ACE on a single outcome.

Our sample was more socioeconomically advantaged and less ethnically diverse than the UK population. Socioeconomic disadvantage is associated with a higher burden of ACEs in studies from a range of countries (Straatmann et al., Reference Straatmann, Lai, Law, Whitehead, Strandberg-Larsen and Taylor-Robinson2020; Walsh, McCartney, Smith, & Armour, Reference Walsh, McCartney, Smith and Armour2019). In our sample this may mean that exposure to ACEs was underestimated and may explain why we have a smaller proportion of participants with four or more ACEs compared with other studies (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart, Mikton and Dunne2017) and therefore associations between adversities and self-harm would be attenuated towards the null. To some extent, this should be accounted for by our including several indicators of socioeconomic disadvantage as covariates in our models. Interestingly, studies have found that adversity confers additional risk of negative mental health outcomes after accounting for socioeconomic disadvantage and ethnicity of participants (Nurius, Logan-Greene, & Green, Reference Nurius, Logan-Greene and Green2012), as seen in our findings also. There is also evidence that ethnic background or race may be differentially associated with likelihood of experiencing adversity. Most data on this come from the USA (e.g. Putnam-Hornstein, Needell, King, & Johnson-Motoyama, Reference Putnam-Hornstein, Needell, King and Johnson-Motoyama2013) however studies based in UK populations have shown that ACEs were lower in those of Asian ethnicity, while those who were non-white and non-Asian had higher levels of adversity (Bellis, Hughes, Leckenby, Perkins, & Lowey, Reference Bellis, Hughes, Leckenby, Perkins and Lowey2014). Our analysis may therefore either under or over-estimate associations between ACEs and self-harm in those with ethnic backgrounds that are not well represented in ALSPAC.

Implications

Further research should also explore the relationship between the severity and timing of exposure to adversity, and the role of specific types of adversity, on pubertal timing in both males and females in order to extend current understanding of how this relationship may impact on future health and wellbeing. Given the recent evidence for an increasing rate of self-harm in adolescence (Sadler et al., Reference Sadler, Vizard, Ford, Goodman, Goodman and McManus2020), and the relationship with childhood adversity, research is needed to understand mechanisms that explain why adverse exposures in childhood increase the risk of self-harm. Identifying modifiable mediators could inform the development of prevention and intervention efforts. Adversity is known to have multiple impacts on development, and mediating mechanisms could include cognitive, behavioural, emotional, social and biological factors (Dube et al., Reference Dube, Felitti, Dong, Giles and Anda2003). Potential mediators that could be studied further include mental health problems (Enns et al., Reference Enns, Cox, Afifi, De Graaf, Ten Have and Sareen2006) adolescent drinking and drug use (Dube et al., Reference Dube, Anda, Felitti, Croft, Edwards and Giles2001; Turecki, Ernst, Jollant, Labonté, & Mechawar, Reference Turecki, Ernst, Jollant, Labonté and Mechawar2012), family support (Cassels et al., Reference Cassels, van Harmelen, Neufeld, Goodyer, Jones and Wilkinson2018), immune functioning and stress reactivity (Berens, Jensen, & Nelson, Reference Berens, Jensen and Nelson2017). Biological mechanisms may also include dysregulated stress-response systems, or cognitive deficits that impact ability to regulate behaviour and emotions (Turecki et al., Reference Turecki, Ernst, Jollant, Labonté and Mechawar2012). As with many complex traits, it is likely that there are multiple interacting causal pathways from adversity to self-harm.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that both childhood adversity and early pubertal timing are risk factors for later self-harm in both males and females. However, we found no evidence that the effect of adversity on self-harm is mediated through earlier pubertal timing. There is a need to identify mechanisms that explain why childhood adversity is associated with an increased risk of self-harm in order to inform the development of prevention and intervention efforts. School-based and psychosocial interventions targeting adolescent risky behaviours and social adjustment, as well as improved quality of puberty education in schools, are needed. Interventions should be targeted prior to and during pubertal onset, given that those who enter puberty earliest are at highest risk of later self-harm.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721000611.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them, and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists and nurses. We would like to thank Lotte Houtepen for her work on the ACE constructs in ALSPAC.

Author contributions

Study conception and design, revising work critically for important intellectual content: all authors; acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data: AER, BM, JH, DJ, CJ; drafting manuscript: AER; final approval: all authors.

Financial support

This study was funded by the Medical Research Foundation and Medical Research Council (Grant ref: MR/R004889/1) Pathways to self-harm: Biological mechanisms and genetic contribution PI: Dr Becky Mars. The UK Medical Research Council and Wellcome (Grant ref: 217065/Z/19/Z) and the University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC. This publication is the work of the authors and Abigail Russell and Becky Mars serve as guarantors for the contents of this paper. A comprehensive list of grants funding is available on the ALSPAC website (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/external/documents/grant-acknowledgements.pdf); this research was specifically funded by the Wellcome Trust (Grant ref: GR067797MA).

DG, PM, CR and BM are supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol, England. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Matthew Suderman and Caroline Relton work in the Medical Research Council Integrative Epidemiology Unit at the University of Bristol which is supported by the Medical Research Council and the University of Bristol (grant number MC_UU_00011/1, MC_UU_00011/4 and MC_UU_00011/5).

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.