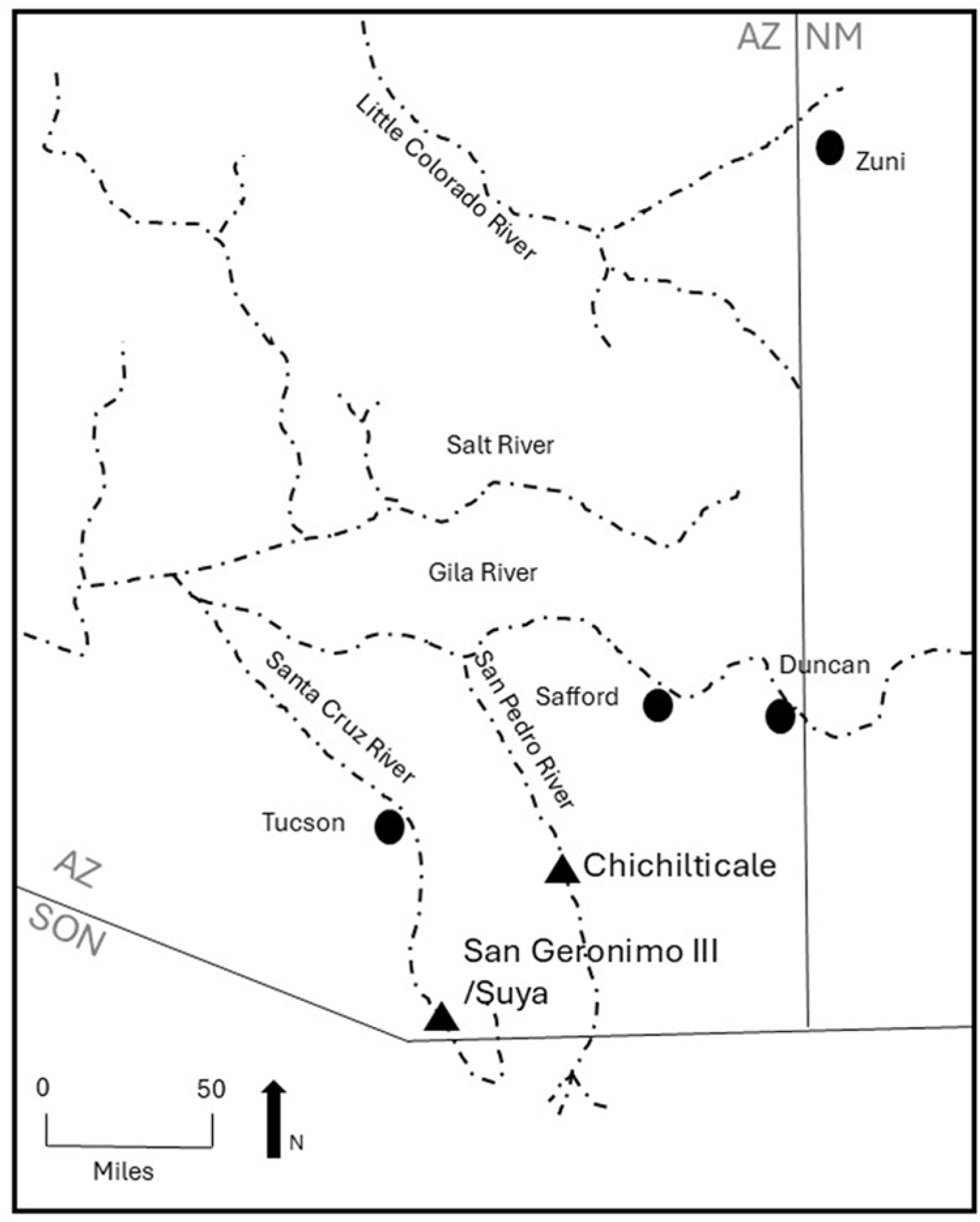

The aphorism “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence” is certainly appropriate for the discovery and interpretation of evidence surrounding the first Coronado expedition site in Arizona. The first site is the largest, with the greatest number and highest diversity of artifacts of any of the 11 others that have since been found (Figure 1). This is one of many reasons this site is inferred to be the incipient Spanish villa (townsite) of San Geronimo III, which was established in 1541 in the Suya Valley—as mentioned in period documents—and destroyed as a result of the first successful Native American uprising in the continental United States. But this extraordinary claim for an early European settlement in the modern-day Santa Cruz Valley, which would be the Southwest’s first, and among the three earliest in the continental United States, requires an in-depth look at and presentation of the evidence.Footnote 1 Its presence much farther west and north than many scholars have expected, and its character, also require discussion of the ways in which evidentiary sources have been scrutinized within an archaeologically based methodological and theoretical framework to arrive at the most parsimonious conclusion regarding the identity of this historically referenced place.Footnote 2

Figure 1. Map of southern Arizona showing the approximate location of Suya (San Geronimo III) and Chichilticale. Map courtesy of Deni J. Seymour.

The Coronado Expedition in Arizona

The Coronado expedition was the first sizeable entrada into what is now the American Southwest, and it consisted of several important phases, which might be viewed as a multifaceted series of ventures instigated by Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza between 1539 and 1542. First among these was Fray Marcos de Niza and his entourage. They crossed through southeastern Arizona and into the final despoblado (wilderness, or unsettled area) toward Zuni/Cíbola in May 1539. It is thought that he had a relatively small contingent of porters and other Native allies (or Indios Amigos), but a sufficient number for the viceroy to feel confident in the exploration of the New Land (or Tierra Nueva). With him was the Black Moor, Esteban, who was one of the four survivors of the failed Pánfilo de Narváez expedition in Florida. He and two others were with Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca in 1536 as they traveled through this region on their way back to Nueva España. Esteban was the spearpoint of this first probe north, moving several days in advance of Fray Marcos, following Native pathways while flanked by local residents, who chose the route. After trespassing at Zuni/Cíbola, Esteban lost his life. Fray Marcos wrote that he went to an overlook and saw the Zuni pueblo of Hawikku before turning back.Footnote 3

Something about Marcos’s reports prompted Viceroy Mendoza to check on the legitimacy of this information. Accordingly, in November 1539, he sent another reconnaissance north under Melchior Díaz, along with Captain Juan de Zaldívar, 16 horsemen and their slaves, domestic servants, and Indios Amigos who served as auxiliary warriors, among other roles (Castañeda and Mendoza in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:235, 391; Zaldívar in Flint Reference Flint2002:253). They reached Chichilticale on the periphery of the despoblado, probably in mid-December 1539, and stayed for about two months before returning south. Archaeological evidence indicates that their departure was prompted, at least in part, by an attack on the encampment by the Sobaipuri O’odham, ancestors of the modern O’odham, who were settled nearby (Seymour Reference Seymour2024, Reference Seymour2025a). The Sobaipuri O’odham represented the easternmost settled villagers in the region at this time before entering the despoblado (Seymour Reference Seymour2024, Reference Seymour2025a).

By the time Díaz’s southbound company reached Chiametla in Nueva España, the main expedition was already underway, expedition members having coalesced at that location. By the time word reached the viceroy, Captain General Francisco Vázquez de Coronado had already set out from Culiacán with the advance guard. Coronado passed through southern Arizona in June of 1540, but even this group was broken into subgroups, with would-be chronicler Juan Jaramillo seemingly days ahead of Coronado.

The main body of the expedition, consisting of perhaps another 2,000 people and thousands of head of livestock and horses, would follow, leaving Culiacán after a delay of about 15 days (Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2019:3). This main contingent of the expedition, with Captain Tristán de Arellano at the helm, would remain first at Los Corazones (San Geronimo de Los Corazones, aka San Geronimo I) in Sonora, Mexico. They then settled into Señora (often referred as San Geronimo II) for a season, until after the summer rains, before proceeding slowly north to Cíbola in the fall of 1540 (Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:393–394). Señora (or San Geronimo II) was placed under the captaincy of Melchior Díaz.

At first, 80 Europeans (horsemen) occupied the settlement at Señora (Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:394), along with their support people (Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:394)—that is, after the main expedition departed. After Díaz’s death by his own lance while on a reconnaissance to the west, the settlement came under the oversight of the villainous Captain Diego de Alcaraz. The population shrank thereafter: two European residents were condemned to hang, so they fled; a man-at-arms was killed with an arrow; and 17 additional men-at-arms (presumably Europeans) were killed in battle near Señora (San Geronimo II; Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:406). This left a total of 60 or so Europeans other than Alcaraz. Following nearby violent encounters between the Europeans and the local Natives—presumably the O’odham—the settlement was deemed unviable (see Seymour Reference Seymour2024, Reference Seymour2025b).

Probably in the early summer of 1541, Captain Pedro de Tovar arrived at Señora to assess the situation and then moved the townspeople north, 40 leagues (200 km) closer to Cíbola, before leading half of the group (presumably, about 30 European men and their supporters) to the Tiguex Province in New Mexico (Albuquerque/Bernalillo). In doing so, he established what is often called San Geronimo III in the Suya Valley, in what would become the Santa Cruz River Valley in southern Arizona. This is inferred to be the first Coronado expedition site discovered south of Cíbola as part of the Arizona Coronado Project, and it is the subject of this article. Alcaraz remained in charge of the 30 or so remaining Spanish/European men, leading to the disastrous collapse of the settlement (Anonymous in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:500; Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:406, 424).

The small Suya settlement of probably 30 Spanish/European men and their slaves, domestic servants, families, and Native allies was troubled from the start as Alcaraz meted brutal punishment on the Native population, hoarded resources, and disrespected (raped) the local women and girls (Flint Reference Flint2002:145; Obregón in Hammond and Rey Reference Hammond and Rey1928:163, 168). Soon after, half, or perhaps 15 European men and their entourages mutinied and returned south to Culiacán, likely in protest of the brutality shown to the Sobaipuri O’odham, among whom they had settled (Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:426–427). They were also disgruntled by the fact that they were forced to stay in the south while others reaped the potential rewards of the larger undertaking farther north in Cíbola and beyond. With 15 or fewer horsemen remaining (and those who had settled with them), the Sobaipuri O’odham seized the opportunity to overtake the settlement.

Understanding the vulnerability of the small townsite, in the late fall or early winter of 1541, the Sobaipuri O’odham attacked and killed most of the population—including Captain Alcaraz, three other European men, and around 100 of the townspeople—leaving few alive to escape and report the incident (Obregón in Hammond and Rey Reference Hammond and Rey1928:163, 168). Documentary sources convey that Suya was attacked when Natives from throughout the land fell upon them (Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:426–427; Obregón in Hammond and Rey Reference Hammond and Rey1928:163, 166–169; Tello Reference Tello1891:438–439). The attack began at dawn. The Spaniards rallied briefly, saving a few residents, who then escaped to the south.

Later documents state that 100 men were killed (Obregón in Hammond and Rey Reference Hammond and Rey1928:166, 168), four of whom, it seems, were Spaniards (European men), including the captain (see Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:605, 607, 608; Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2019:294; Tello Reference Tello1891:438). This suggests that the population as a whole—including non-European men, as well as women and children, and perhaps even additional European men of lower status—had exceeded 100, with the total perhaps around 125 or 150, including women and children not mentioned in the muster roll. Some of those who did not return to Nueva España were kidnapped rather than killed, according to a later account (Obregón in Hammond and Rey Reference Hammond and Rey1928:163, 168; Obregón Reference Obregón1988 [1584]:148). Another document records that according to one of the survivors, only a priest and five soldiers (i.e., Europeans) escaped (Obregón in Hammond and Rey Reference Hammond and Rey1928:168–169). This would mean that six Europeans and perhaps some of their support people and families may have survived. The common practice of not mentioning anyone other than European men leaves open the possibility that other non-Europeans—and in particular, women and children—escaped with them or were not killed but were taken as war captives. In fact, the differing numbers of survivors reported seems to be reconciled in part by distinguishing between European men (some of whom were mentioned in the muster roll or other sources) and others who tended not to be mentioned in the muster roll and in most other accounts—that is, non-Europeans, including Indios Amigos, Native domestic servants and those of other ethnic backgrounds from the south, African slaves, and then European and non-European women and children who were simply not mentioned (women and children were later noted in Obregón in Hammond and Rey Reference Hammond and Rey1928:163). These population numbers will be relevant to the arguments presented below. The reason these sums seem appropriate is that the expedition-related archaeological evidence at the Santa Cruz Valley site is spread over a wide, 1 km long area and is characterized by numerous distinct habitation areas, each with artifact arrays sufficiently dense and diverse to indicate that each was the focus of distinct households or the equivalent. Continuing research is revealing additional habitation features in these areas that should eventually characterize the nature of these groupings more clearly.

Along with the successive groups of northward-moving expeditionary forces, there were messengers who traveled back and forth between the north and places to the south, including Mexico City and to and through the townsite of San Geronimo III. There were also scouting detachments to adjacent areas, such as the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River, and perhaps to the San Bernardino Valley and in the surrounding mountains for prospecting.

Available records indicate that the Coronado expedition was the only large-scale authorized expedition to enter this area at this time. As will be discussed in more detail below, other expeditions, entradas, and forays that might have made their way north would have stayed for only a limited time and then moved on, and they would have been in relatively small groups that would have left but a fraction of the evidence found at this largest site. Yet, all available evidence indicates that only a subset of potential travelers made their way this far north, and those that did enter Arizona’s boundaries represent various stages of the Coronado expedition. Of these, some stayed for longer periods of time than did others. They occupied and used “places” for different purposes, such as (1) residing overnight while moving along the trail, (2) pausing for two months when impeded by weather with the intent of moving on, and (3) establishing a permanent settlement that served as a base of operations for the expedition. If unrecorded entradas occurred, these would look much like overnight or short-term encampments owing to their small size, short duration of use, and lack of intent to stay, and resulting from the activities involved in scouring the landscape for minerals or bodies to enslave. Consequently, each type of these entradas can be subdivided based on the number of people, the length of their stay, and the intent of their presence. All of these factors have archaeological correlates that allow distinctions between each type of use and that therefore present expectations for different site types. All of these considerations were evaluated when assessing whether the Santa Cruz Valley site was Suya, and they will be explicitly discussed below in light of the site types that have been defined in Arizona.

Three Classes of Archaeological Sites

Throughout the 260 km (160 linear mi.) of the current project area, three classes of expedition sites have been found. These classes correspond to widely recognized archaeological site types that reflect (1) length or duration of stay, visible in the density and diversity of artifacts and character of features identified; and (2) the size of the group, reflected in the spatial extent of the site footprint. Site types include (1) short-term, limited-use camps; (2) a longer-term but still short-lived camp; and (3) a large habitation site.Footnote 4 All but two archaeological sites are consistent with the first classification of short-term camps, and each of the two other site-type categories are represented by a single site. As will be discussed in a subsequent section, this distribution is also consistent with expectations for types of places presented by the documentary record.

Archaeological Traits of Short-Term Camps

Of the three classes of archaeological sites found along the Arizona portion of the Coronado expedition route, most represent relatively short-term encampments where features and artifacts have been found. As a class, these types of sites represent intermittently used short-term camps by moderately large groups, and they conform with archaeological models of mobile group encampments, with few artifacts and only a limited range of feature types, where spatially separated areas may convey social distinctions within a larger group (Binford Reference Binford1980; Cribb Reference Cribb1991, Reference Cribb, Barnard and Wendrich2008; Eder Reference Eder1984; Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, Poyer and Tucker2005, Reference Kelly, Poyer, Tucker, Sellet, Greaves and Yu2006; O’Connell Reference O’Connell and Heppell1979; Reher Reference Reher and Davis1983; Savishinsky Reference Savishinsky1974; Seymour Reference Seymour2010, Reference Seymour2015a, Reference Seymour and Seymour2017; Woodburn Reference Woodburn, Ruth Tringham and Dimbleby1972; Yellen Reference Yellen1977). Because of the overall size of the expeditionary force and each of its components, these sites may cover a substantial area—perhaps a couple hundred meters across—but with discrete, spatially distinct loci visible; low densities of artifacts; and no or few artifacts and features in intervening areas. These encampments utilize the natural terrain as encountered, with few and minimal modifications.

Among the features are faint extant or improvised clearings that required little effort to create and that are consistent with occupational rings used by Apache, Jocome, and other mobile peoples in the area (Seymour Reference Seymour2009a, Reference Seymour2009b, Reference Seymour2010, Reference Seymour and Deni2012, Reference Seymour2013, Reference Seymour2016). Among mobile Natives and for the Coronado expedition, these represent where the surface was cleared of rocks so that temporary shelters could be erected or where travelers could sleep directly on the ground surface. These are the types of limited-use and special-use sites used by people whose lifeways are defined by moving across the landscape after only a short stay in any one location. This also characterizes movements of travelers, including the Coronado expedition, when en route as a sizable transient group. The main differences between a site used only once and a site that was used repeatedly (for short periods of time or for a limited range of activities) is that, with time, the features may become somewhat more clearly defined, a wider range of feature types may be present (e.g., tent clearings, firepits, rock art), and there may be slight increases in artifact density and diversity.

The number of artifacts found at these short-term camps is consistent with a short-term stay. Mostly defined by systematic metal detecting, these artifacts generally range from one or two to a half dozen metal artifacts that are clearly diagnostic of the Coronado expedition, along with a series of potentially related metal items, and often many others that were deposited at a later time.

A range of life-related activities occurred at these campsites, which were undertaken by sizable numbers of people, who presumably came through at different times for a limited number of days within a limited number of years and who stayed for only a short duration of time (overnight or possibly two or three nights, perhaps successively). Consequently, the low frequencies of metal artifacts reflect this short duration of stay at the site, where only a few items from a subset of activities were lost or discarded. These classes of artifacts and the inferred activities from which they resulted tend to be fairly limited. Classes of artifacts other than metal that are not detectable may also be present but in low enough occurrences that they are not visible from surface inspection. Here in the Southwest, the ground surface in many settings is sufficiently exposed and eroded such that artifacts present in any quantity would be expected to be represented in the surface assemblage. This is not the expectation, however, for encampments situated in floodplain settings.

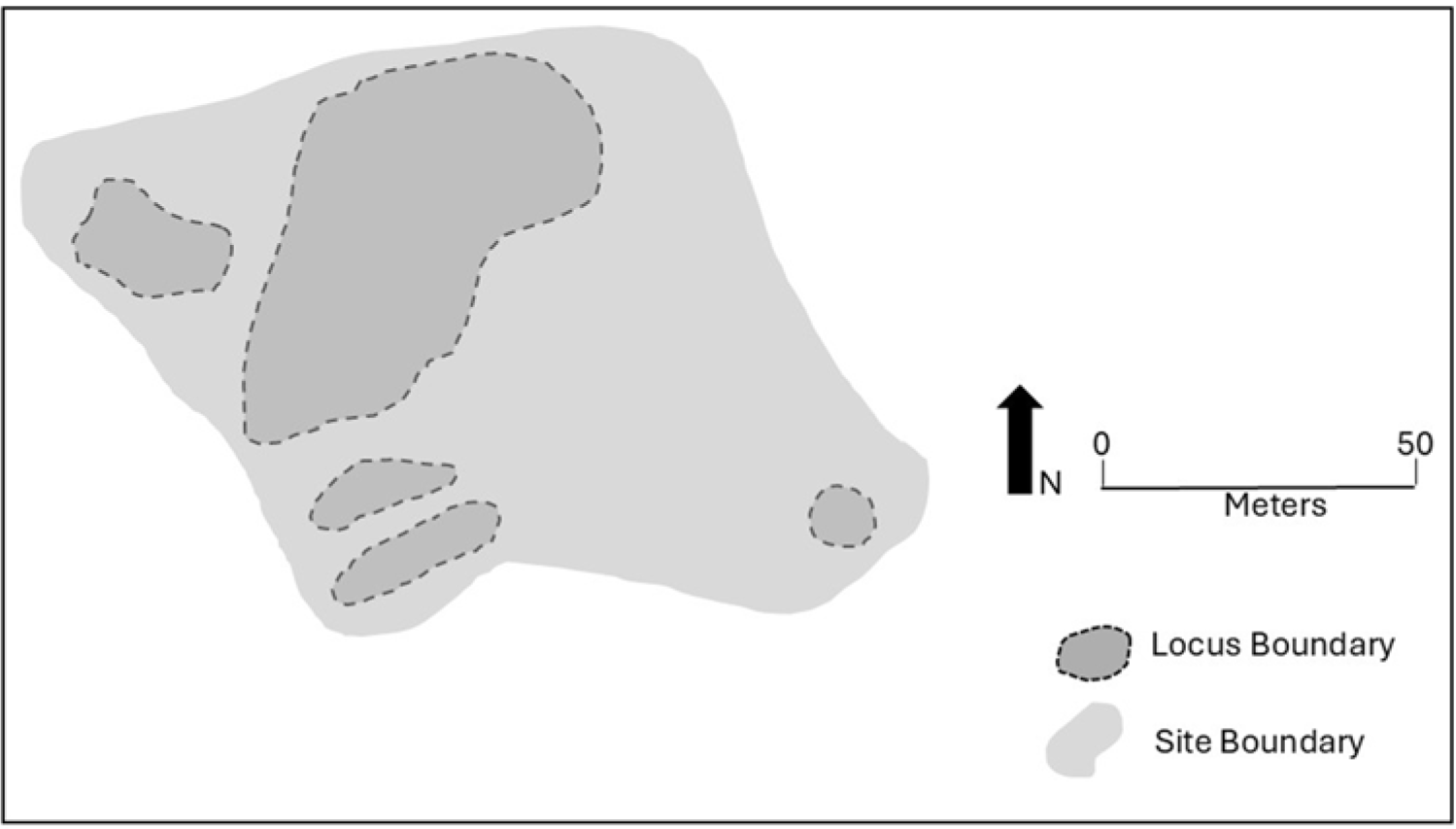

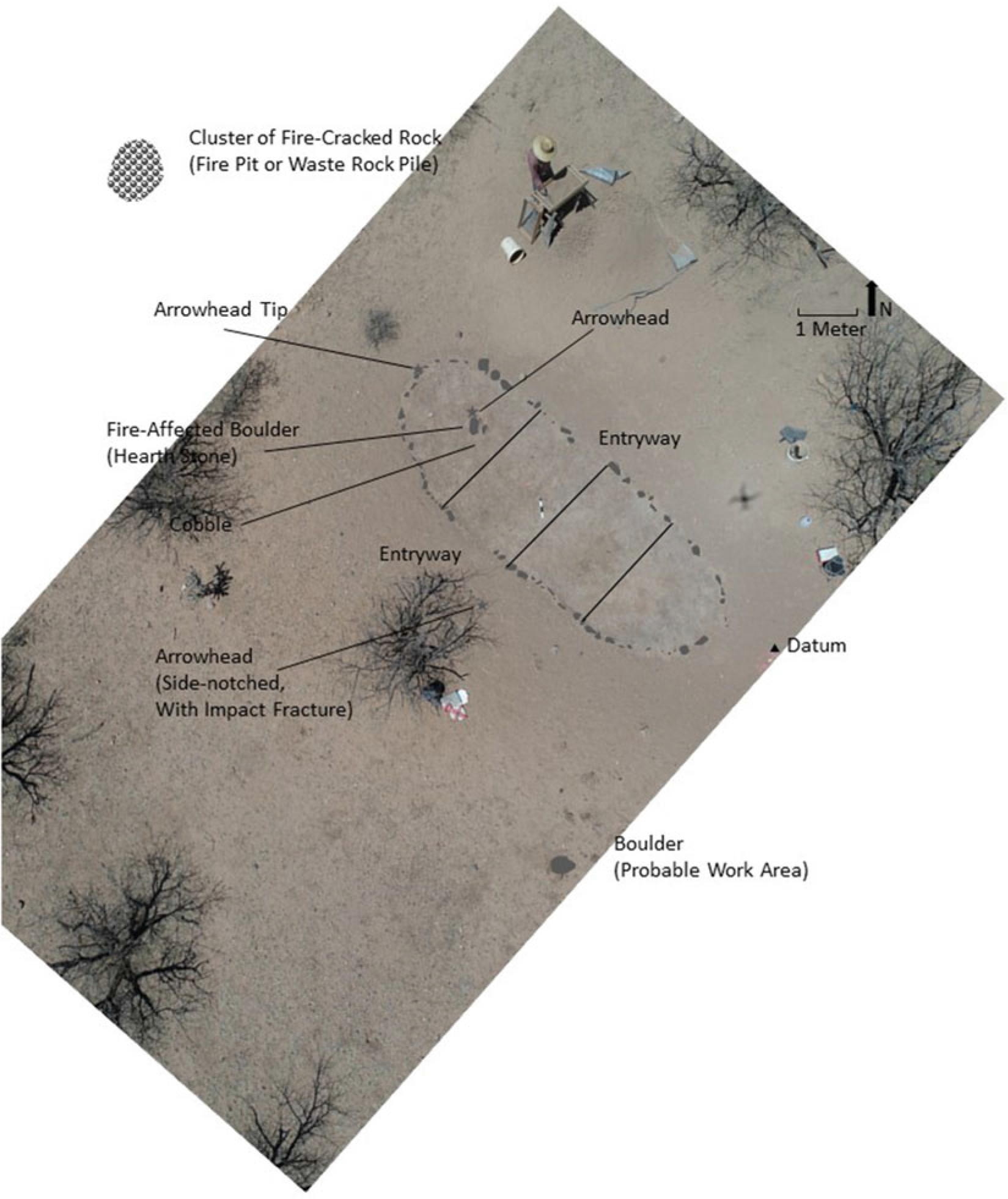

An example of this type of site was recorded along the Babocomari River, on the route segment between Suya and Chichilticale (also see Paraje del Malpais in Seymour Reference Seymour2023). Campo Cascabeles (Bell Camp) has been mapped, and a systematic metal detector survey was undertaken on each locus. The outer site boundary is spatially expansive, measuring 100 × 235 m, although the actual occupational area (4,400 m2) consists of five variably sized loci, some of which are separated by open or unmodified rocky or sloped spaces (Figure 2). The camping zones, which are inferred to represent tent clearings or sleeping areas, consist of flats with either an absence of rocks or deliberately placed rocks, including definable features such as firepits. There may have been additional loci once included within a larger site boundary that are no longer visible owing to disturbance from later activities, including trampling during cattle grazing, washouts along the river, bulldozing, and removal of diagnostic artifacts by later visitors.

Figure 2. Plan drawing of Campo Cascabeles—a short-term, limited-use camp used as an overnight trailside camp. Image courtesy of Deni J. Seymour.

Within each of the defined loci, at least one Coronado-expedition-specific diagnostic artifact was recovered to justify the expansion of the site to include that portion of the landform. Earlier, later, and Coronado-expedition-specific artifacts (and in some instances, features) are present in each locus, consistent with the recognition that all good camping areas tend to be reused through time (few, if any, sites are truly single component; see Seymour Reference Seymour2010). Artifacts specifically diagnostic of the Coronado expedition include only six items: a bolt head or conical nonferrous point base, three complete and fragmentary copper bells, a medieval horse or mule shoe fragment, and a Nexpa-style ferrous point. In addition, numerous other artifacts that are not considered especially diagnostic may very well relate to this component, including a key, cut copper, nail shanks, lead shot, knife blades and tips, scissors, needles, fishhooks, tacks, curb bit fragments, a button, and more. Artifact densities and frequencies are low, conforming to expectations resulting from a limited stay or a series of limited visitations. Consequently, although the space encompassed by the site is sizable and the footprint of the activity areas is large—indicating many people or expansive space needs—the artifacts left (lost or discarded) by the travelers are few.

Short-term camps are the most commonly occurring site type, both expected (see below) and found. This class of sites is consistent with expectations for this expedition presented in the documentary record and, more generally, with expectations for expeditions involving sizeable groups of people traveling through an area on the way to a predetermined place. These types of sites also align with existing archaeological precepts for trailside encampments.

Archaeological Traits of a Longer-Term Encampment

Any sites encountered where there would be a longer-term stay than exhibited at the overnight trailside camps are expected to possess greater frequencies, a higher density, and a greater diversity of artifacts. Expectations based on an expansive array of archaeological theory are that the longer people stay, and the more people who stay, (1) the greater range and intensity of activities there will be, (2) the greater the number and higher density and diversity of artifacts there will be, and (3) the more distinct the feature footprints will be (e.g., Binford Reference Binford1980; Lightfoot Reference Lightfoot1986; Reid Reference Reid and Reid1982:196). Even so, people did not expect to stay for an extended period of time, so there was no plan for permanency along certain portions of the trail. It is important here to point out that the expectation of a longer-term occupation rather than (but also coupled with) the actual duration determines the amount of investment in features, degree of modification to the landscape, formality of spatial layout, and range of artifacts present (Kent Reference Kent, Kroll and Price1991; Seymour Reference Seymour2009a). In circumstances where there is an expectation for long-term occupation, as at Suya, there should be more permanent and therefore more substantial housing than at the other two types of Coronado expedition sites along this portion of the trail. Consequently, features may be clearer than at shorter-term camps, but they may or may not exhibit a somewhat greater investment in modifications to the terrain or built environment, depending on whether people expected to stay.

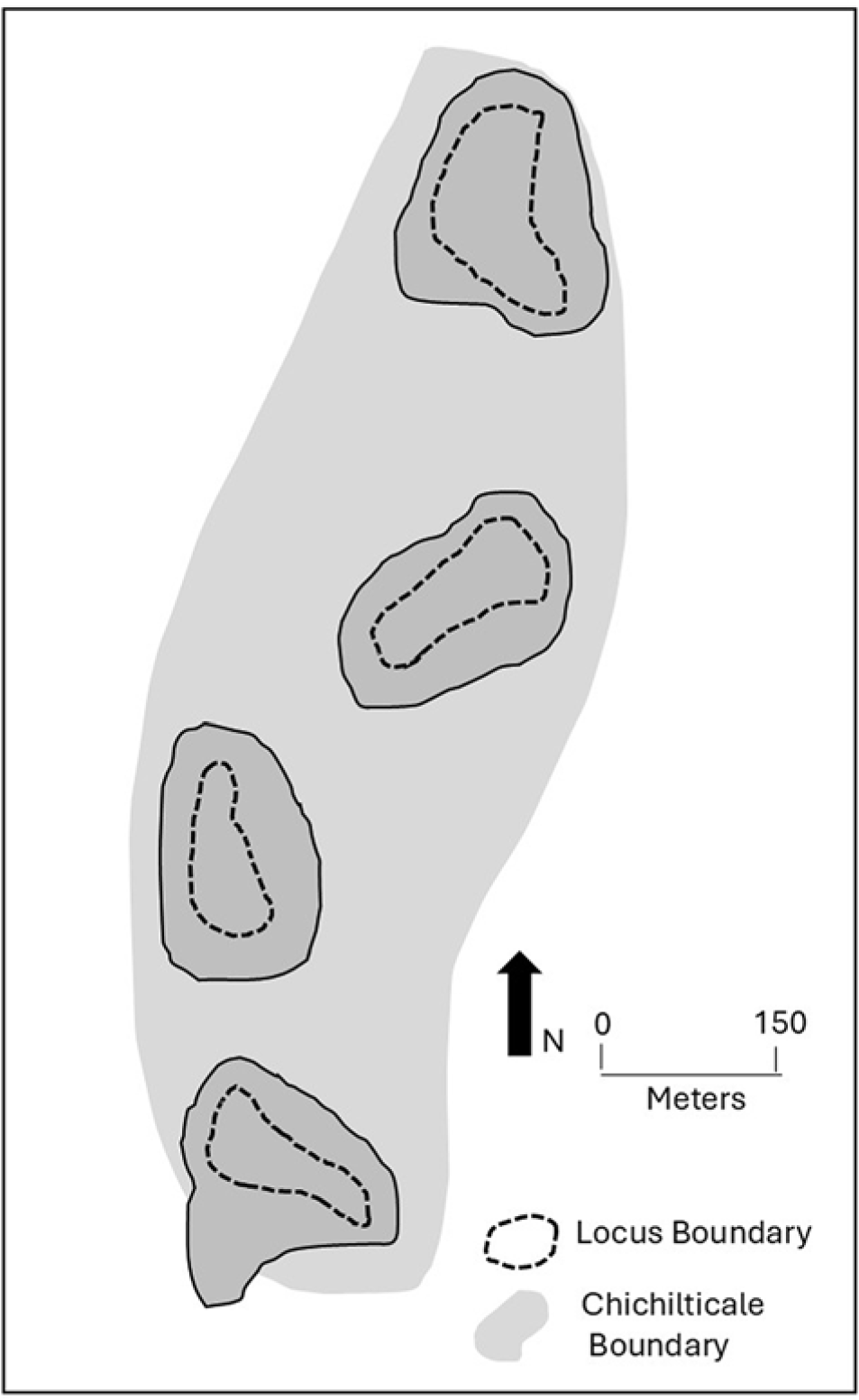

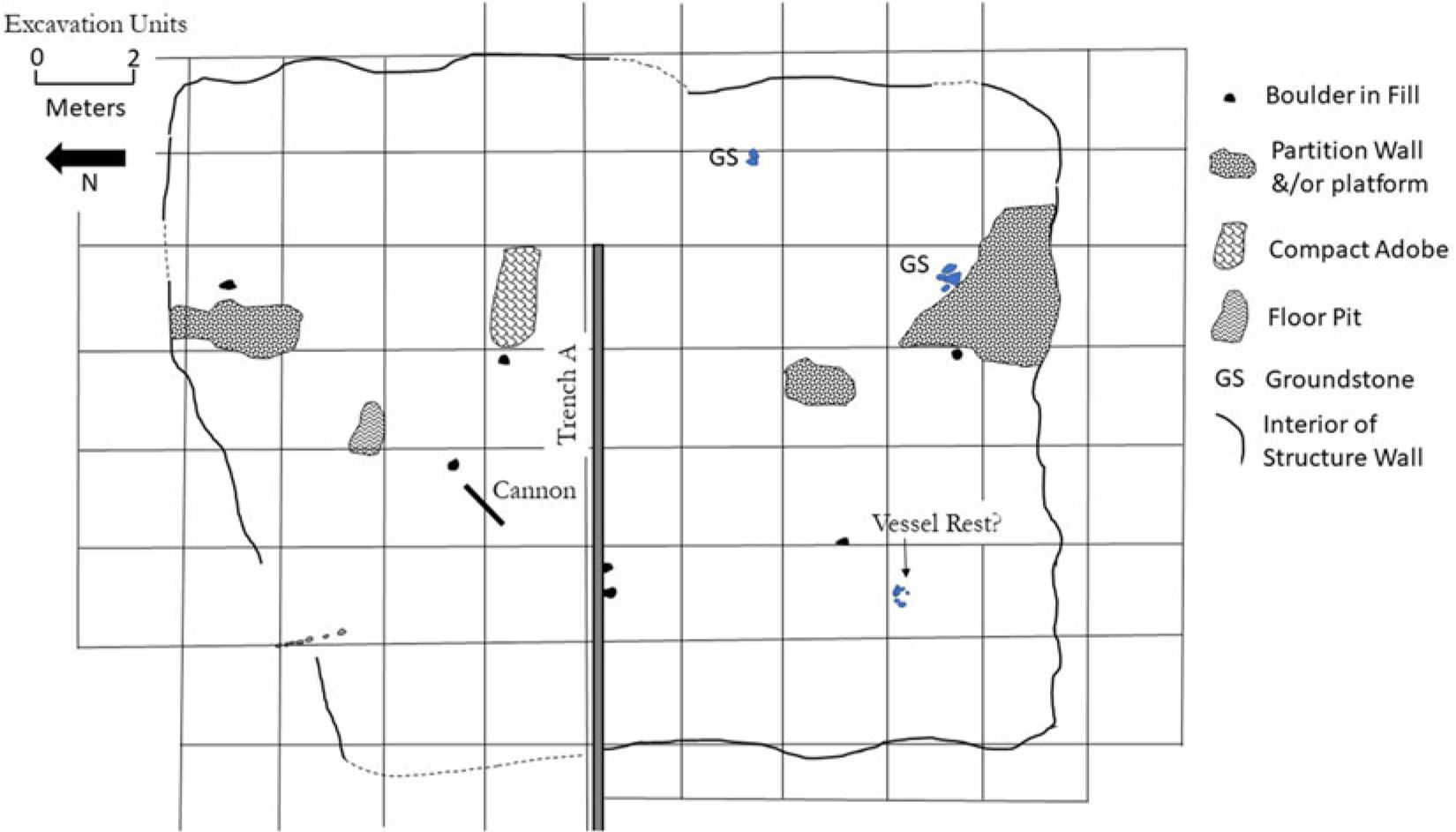

A single locale (encompassing four site designations) is representative of this site category (Figure 3). This is inferred to be the two-month winter encampment at Chichilticale—based on its location, size, association with a ruined roofless house, and other factors (Seymour Reference Seymour2025a). The locale was recognized archaeologically because of the density and diversity of Coronado-expedition-specific metal artifacts, which was much higher than at any of the shorter-term encampments. Systematic metal detecting resulted in the recovery of 400–500 expedition-related metal artifacts (many of which were small metal flakes and tiny tacks, as well as iron projectile points from an undocumented battle that occurred at this time; Seymour Reference Seymour2024, Reference Seymour2025a, Reference Seymour2025b). Among the diagnostic Coronado-expedition artifacts are gable-headed (caret-headed) nails, copper bells, iron boltheads and other projectiles, and copper lace aglets.

Figure 3. Plan drawing of Chichilticale, showing the distinct loci across a larger site boundary. This is inferred to be the two-month 1539–1540 winter encampment occupied by Díaz and is therefore consistent with a longer-term but still short-lived camp. Image courtesy of Deni J. Seymour.

As with shorter-term encampments, features consist of simple clearings on an otherwise rocky surface. These represent tent clearings and workspaces that are clustered in different areas on each of the four landforms with unmodified space separating them. Among these clearings are firepits, waste rock and ash spoil piles, dumping areas or small middens where debris was deposited, and work areas with evidence for equipment repair where discarded or lost items—such as nail shanks and small tacks—were left in place. Forge working areas are evident, which include hammer scale, raw stock and waste iron, fire areas, and cobbles/boulders that seem to have been used as anvils and perhaps bellows shield stones.

The expansive size of this encampment may be explained by the fact that it is positioned on four distinct landforms that are separated by lower, uninhabited space. When the collective lengths of the inhabitable portion of these landforms themselves are added together, the occupational space is only about a half a kilometer long or so, which left about 400–600 m of area used by each European, excluding rocky space between tent areas.

Site structure is clearly visible. The tent clearings are spatially separated, as at short-term camps, suggesting that social distinctions are represented by physical spacing, which is likely related to the number of Europeans present, their rank, and the size of their contingent. Replication of other feature types, both on individual landforms and across all four landforms, indicate that a set of activities by specific mess groups or household units were likewise duplicated.

All of these attributes clearly differentiate this site from those used on a more limited basis. The abundance, density, and diversity of artifacts and the hardened nature of structured space within the site point to a longer-term occupation than a mere overnight trailside camp. A similar level of difference is noticeable between this and the final site type.

Archaeological Traits of a Large Habitation Site

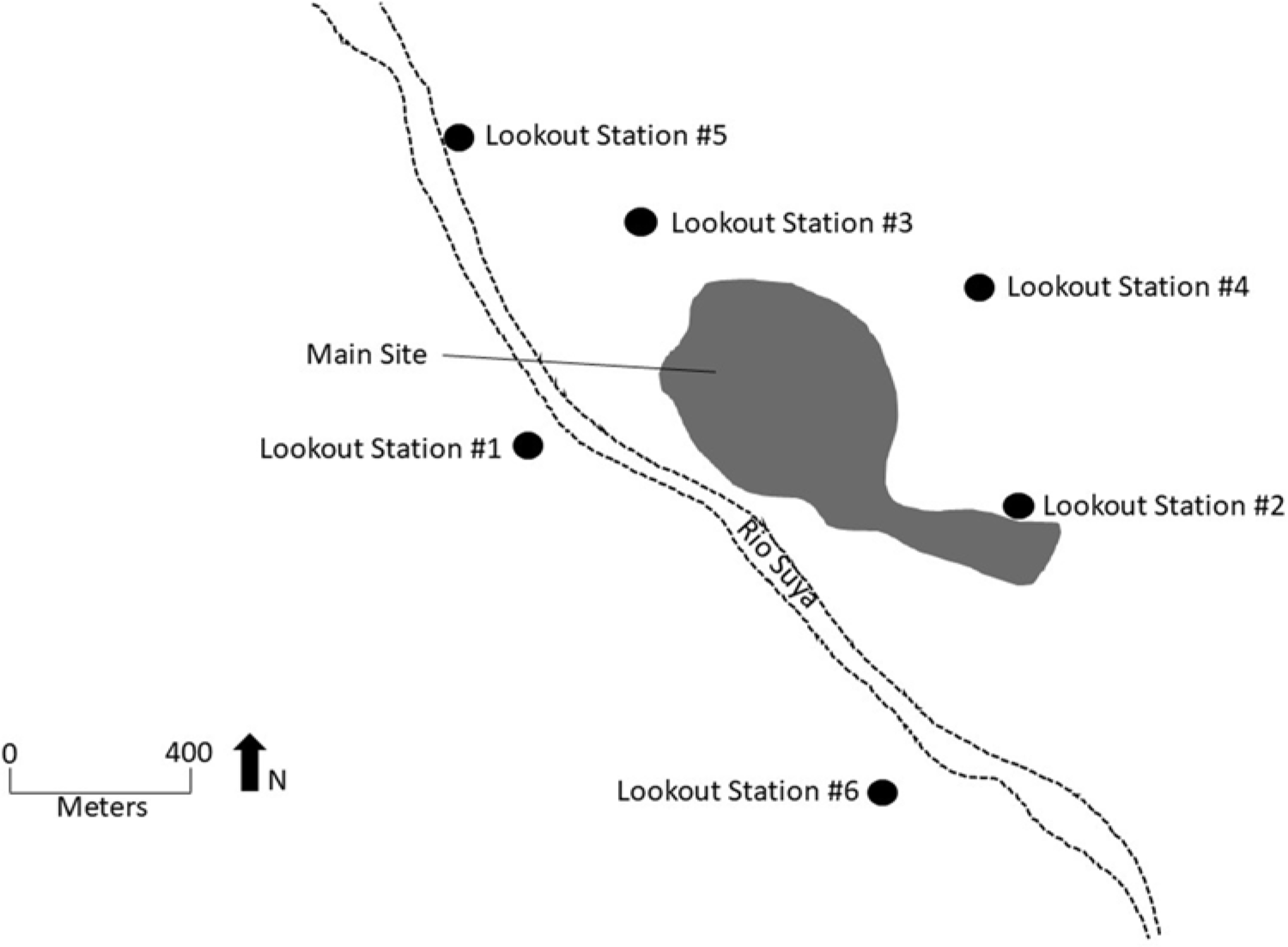

Patterning in Coronado expedition artifacts across the 1 km long, 600 m wide expanse that is inferred to be the townsite of Suya indicate a formally organized site structure (see Figure 4). Discrete areas have been noted across the terraces, as well as in the surrounding hills and high points where six lookout stations have been identified. Occupational areas are indicated by relatively dense concentrations of Coronado expedition artifacts, including items related to household activities and a range of subsistence activities. Sizable artifact concentrations are positioned on flats on either side of the main arroyo in the heart of the site, with other clusters discernible on the terraces to the north and south.

Figure 4. Plan drawing of Suya, a large habitation site intended as a permanent settlement or townsite. Drawing shows the site outline and its relationship to the lookout stations. Image courtesy of Deni J. Seymour.

The amount of accumulated debris—consisting of over 2,000 mostly metal artifacts collected so far (work continues) during systematic metal detecting (not including those from excavated contexts)—is consistent with a substantial habitation site, a settlement. For an archaeologist, density and diversity of material items are measures by which occupational size, intensity, and duration are assessed. A sizable subset of the overall assemblage consists of household-related artifacts that indicate not only a diversity of activities and a longer duration of occupation than a limited-use camp but also an expectation to stay even longer. Some of these include needles, awls, thimbles, scissors, ferrous and copper fishhooks and a line weight, ball and flower buttons, clothing fasteners, copper and ferrous lace aglets, ear and snuff spoons, pewter lice-catcher lids, copper pot fragments, green glaze and majolica sherds, various colored glass shards, Early Ming Dynasty porcelain, nonlocal plainware pottery, possible Mexican orange ware, decorative items, a pearl, a glass bead, belt buckles, scalpels, nails, box latches and nails, and a butcher knife/cleaver. In addition, blade-cut faunal material from domesticated and wild species is represented. Rather than representing “an overturned wagon of expeditionary goods,” as one anonymous historian suggested, these are spread out across the 1 km landscape in clusters indicative of household and activity areas, with replication of certain items across areas, accompanied by an overlay of battlefield evidence. Household artifacts are concentrated in areas where features are present, indicating household clusters and work areas.

Activities outside the home are represented by metal working, including forging, as indicated by raw iron and lead stock, iron hammer scale, and lead dross. One possible farrier’s or nail smithing area produced over 40 gable-headed nails along with an equal number of other nail types and shanks mostly concentrated in a 100 m2 area. A worn butcher’s knife or cleaver at the extreme south end of the site may indicate that butchering and tanning was conducted downwind, at a distance from the residential areas, as was often the case for smelly trades at that time (e.g., Jørgensen Reference Jørgensen, Krampl, Beck and Retaillaud-Bajac2013:302).

In addition, a range of horse gear and tack was recovered, including horseshoe fragments, gable-headed nails, spur rowels, spur or bridle buckles, copper bells and jingles for harnesses and rump covers (anqueras), bridle bit fragments, rosettes, coscojos (decorative pendants or jingles for bridle bits) and jingle bobs, and a rasp. Some of the gable-headed nails are crimped as if they were still in structure walls or perhaps in the hoof when the horse died, consistent with the documentary record that indicates many horses and livestock were killed (Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:427).Footnote 5

The frequencies, densities, and diversity of household and industry-related artifacts clearly indicate a more intensive presence than a short-term camp and represent an even richer assemblage than at the two-month-long occupation inferred to be Chichilticale. The richness and character of this assemblage is consistent both with a longer-term stay than any encampment found to date and with a population that moved as permanent residents to this location, expecting to stay rather than travel farther along the trail. Moreover, the presence of especially nice, fragile, and bulky items is not expected on long terrestrial expeditions (e.g., Mathers Reference Mathers and Mathers2020:7). Items found at Suya—such as Ming porcelain, green glaze, majolica, and glass—have not been found at other locations along the route. This suggests that some of these residents were either prepared to stay in one location for an indeterminate amount of time—that is, in this permanent settlement, referred to as a villa—or that once they settled into this location, additional items were transported north to meet more enduring needs. This might be expected given that Suya seems to have been planned as a supply center and the primary base of operations for the expedition, where residents apparently (1) intended to raise livestock and grow and gather other supplies to transport to the north (hence their need to take two-thirds of the resources gathered from the local O’odham; e.g., Flint Reference Flint2002:145) and (2) consistently—if perhaps unpredictably—received supplies and messengers from the south. This was a settlement, so it is expected to have somewhat different items from those that have been recovered from battlefields that are not located at European settlements and from limited-use campsites. The question remains as to whether such items will also be recovered from longer-term campsites farther north in the Tiguex Province (e.g., Railey Reference Railey2007; Vierra Reference Vierra1989, Reference Vierra and Bradley1992) when such sites are eventually intensively investigated, although documents convey that the Europeans evicted Natives from their pueblos and used those buildings as winter quarters.

Excavations underway at this site have exposed expedition-related features. Substantial structures indicate that the occupants perceived this as an enduring settlement rather than an encampment that would soon be abandoned. Knowing they were relegated to this southern outpost with no hope of continuing on to the north, Castañeda’s account indicates that half of Suya’s residents mutinied (Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:426). Those that remained continued to settle in, constructing permanent housing rather than remaining in tents as they had at Chichilticale.

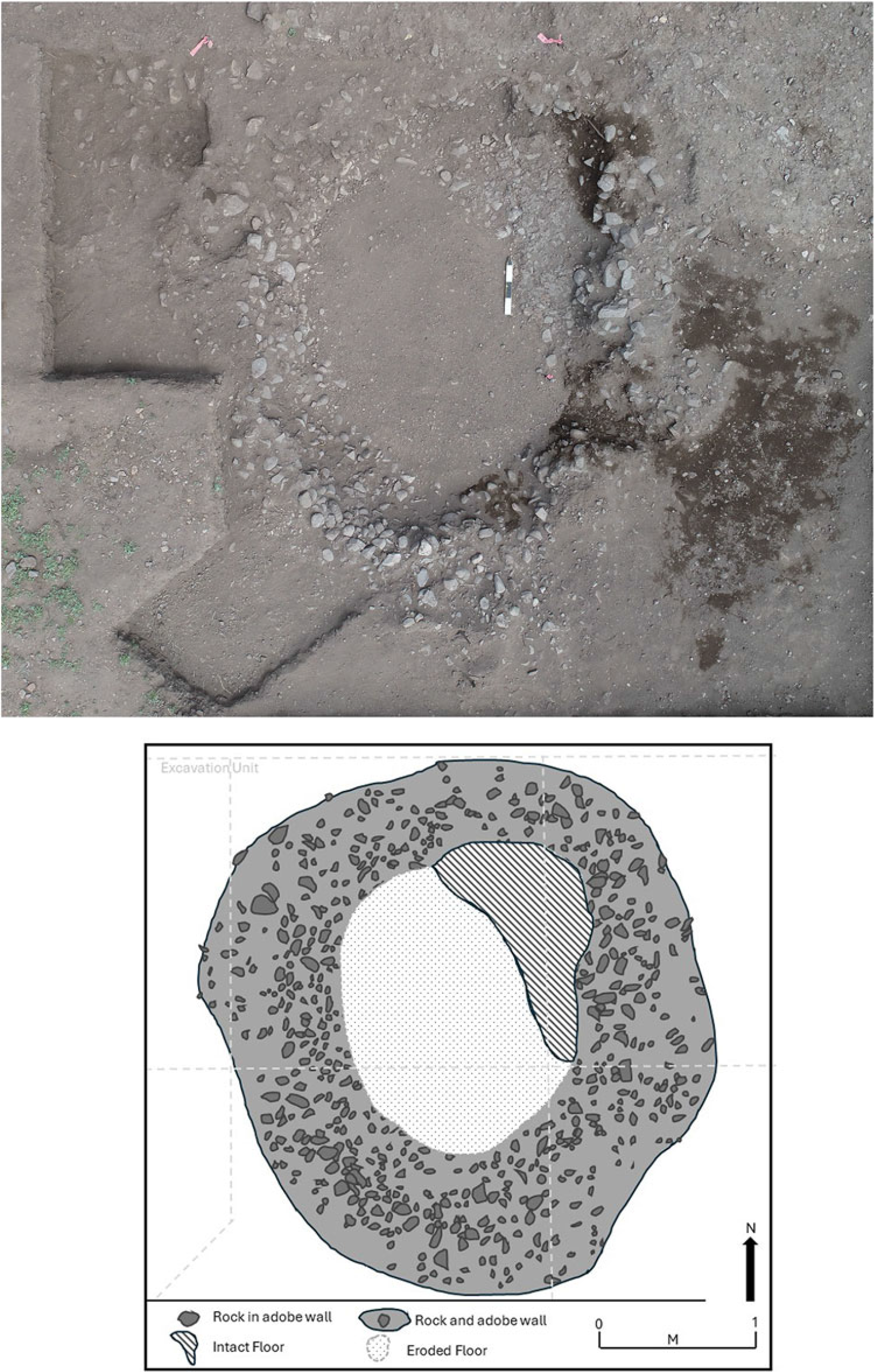

Evidence of two or three types of Coronado period structures have been unearthed and chronometrically dated, which provides evidence that this was a settlement rather than a short-term encampment. One type consists of oversized Native structures (Figure 5). An excavated Sobaipuri O’odham–style house associated with this expedition is more than 2 m longer than is typical. Chronometric dates obtained from within the burned structure are consistent with the Coronado expedition, including a radiocarbon date that, at 95.4% probability, has two intercepts (common for this period): (49.9%) 1540–1634 cal AD, (45.5%) 1456–1529 cal AD (Beta-593375). A luminescence date on a burned stone from the house hearth also produced a result consistent with the expedition (AD 1500 ± 80, [1420–1580 CE]; UW4191).

Figure 5. This extra-large Sobaipuri house is shown with a plan drawing overlying a photograph. Excavation revealed projectile points, burning, and chronometric dates consistent with the Coronado expedition, indicating that the feature was likely occupied by expedition members and that those members were probably not European. Image courtesy of Deni J. Seymour.

A west or central Mexican stone arrowhead situated nearby prompted the excavation of this structure, as did its lone position, which did not conform to the traditional pattern of paired structures in rows in the formal Sobaipuri site layout. Excavations revealed fragmentary Sobaipuri arrowheads inside the structure and in its walls, as if discharged into the house, suggesting this burned structure was involved in the final battle. Its placement at the outer fringe of the Spanish townsite and the absence of metal and other European artifacts may suggest that these types of structures were occupied by Indios Amigos. Further research may confirm this.

The initial main excavation area exposed a 220 m2 burned Spanish structure with collapsed stone-and-adobe perimeter walls that were more than 3 m high (Figures 6 and 7). Tentatively referred to as “the barracks,” this large structure was bisected by three segments of a stone-and-adobe partition wall. The incomplete partition wall indicates that construction was still underway, or that it may have been destroyed at the end of the battle. An abundance of fallen wall materials, but an absence of roof fall, suggests that the under-construction structure was likely covered with temporary roofing, as does the pattern of gable-headed nails that were linearly arranged and may have been used to hold a roof tarp in place. Burn patterns and an upright stone suggest that a perishable platform furnished the west side of the room. A small bronze cannon, a gable-headed nail, green glaze, ground stone, and other items on the floor confirm association with the Coronado expedition. Many more expedition-specific diagnostic artifacts were found in (and around) the structure, but not in direct contact with the floor. A radiocarbon date from floor context under a pestle produced a date consistent with the expedition: (69.3%) 1495–1602 cal AD (455–348 cal BP), (26.1%) 1610–1656 cal AD (340–294 cal BP); Beta-615762. A floor sherd from a Native-made, nonlocal brownware pot break produced a luminescence date of AD 1550 ± 30 (1520–1580; UW4195). This substantial Spanish-style rectangular stone-and-mud structure and the major construction underway clearly indicate its intended permanency. This structure is vastly different from the Native-made structures of the local Sobaipuri O’odham. This structure alone fits the criteria for a settlement, exhibiting attributes that show that this formally constructed structure was intended to be long term.

Figure 6. This large rectangular stone-and-adobe walled structure is referred to as “the barracks” owing to its excessive size. Artifacts, chronometric dates, the unusual nature of construction for the area, and its placement within the overall site indicate that this burned feature was constructed during the Coronado expedition. Image courtesy of Deni J. Seymour.

Figure 7. This large rectangular feature is outlined by a stone-and-adobe wall that collapsed and is mostly eroded. The circular features include an intrusive Sobaipuri O’odham trash-filled pit and Archaic pithouses that underlie the Coronado expedition structure. Image courtesy of Deni J. Seymour. (Color online)

It is widely thought that Suya was intended as a supply station, so its population was likely dedicated to building up livestock herds, intensifying crop production, and exacting tribute. Tribute levels were especially burdensome for the Native population, as indicated by one reason given for the attack: Alcaraz “was not content with what the Indians provided to the Spaniards, which was two shares of the supplies they gathered” (Escobar in Flint Reference Flint2002:145). Given that the Spaniards were hording provisions, it is not unreasonable to expect construction of specialized storage features to securely hold supplies and resources until they could be transported. One of the excavated later trash-filled contexts was a small 1.5 m diameter feature with adobe-and-stone walls and a hardened plastered floor fragment (Figure 8). Other similar features are present elsewhere on the site, including a partially excavated one adjacent to the barracks. These are interpreted as possible specialized storage features as a result of a conversation with a Mexican archaeologist, who stated that if this feature were found in his area, it would be considered a cuexcomate, or maize storage feature (David Carballo, personal communication 2024). Given that such features were likely built by or under the oversight of Indios Amigos, this interpretation is not unreasonable. If it is not a storage feature, it may be a small habitation structure for perhaps one or two people. We will probably excavate another one of these features, but the assumption is that the Natives would not have destroyed and burned the food and other resources contained within it, so there is not likely to be direct evidence of their use. In fact, the timing of the attack may have corresponded with the time of year the O’odham were preparing for storage of winter goods and were confronting dire shortages.

Figure 8. This photograph and plan drawing show a small stone-and-adobe walled circular structure that may have been used for storage, or perhaps a one-or two-person habitation feature. Images courtey of Deni J. Seymour. (Color online)

Suya’s occupants may have been attempting to make up for their predicament of being left in the south by mining local ore and placer deposits. The town was placed in one of the best locations in modern Santa Cruz County for gold deposits. Prior to the battle, as Castañeda recorded (in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:427), “sources of gold had been discovered, but because they were in the tierra de guerra and there was no possibility [of working them], they were no longer being worked.” Analysis indicates that Suya was at the northern end of the tierra de guerra (war zone; see Seymour Reference Seymour2024), so Castañeda’s statement, mentioned in the context of the battle, suggests that it was Suya’s European residents who were now prohibited from working the gold deposits in the surrounding area (Seymour Reference Seymour2025a), if for no other reason than there were no other European residents in this tierra de guerra north of Culiacán, although prospectors likely ventured north. Archaeological recovery of a specimen of processed silver (if, with continued work, this can be definitively connected to this early component) indicates that silver was being extracted and processed as well. An effort may have been made to protect one mining operation in the mountains just north of the townsite, which may have been attacked, explaining the presence and attempted destruction of the third of three bronze cannon now known from the Coronado expedition in southern Arizona. Its placement after apparent ritual destruction on a sacred mountain may reflect the Natives’ desire to safely cache this instrument of thunder and lightning in the high-elevation home of thunder and lightning (e.g., Obregón in Hammond and Rey Reference Hammond and Rey1928:167; Seymour Reference Seymour2022).

Archaeological evidence of a pitched battle at Suya, with an especially high concentration of fragmentary metal and stone projectile points in the main arroyo, which partially bisects occupational areas, is what initially prompted the search for the identity of this site in documentary sources. Accounts indicate that this attack was sustained and intensive. Both residents and attackers were engaged in substantial combat. The widespread nature of battle evidence including the number of projectile points, lead shot, and the two cannon indicate that this was a prolonged fight that focused on the heart of the townsite and at least three of the spatially separated lookout stations. Sobaipuri-style housing in lookout areas with diagnostic Coronado artifacts suggest that these features sheltered those who kept watch. At Lookout Station #1, the men seem to have found shelter in or between the Native-style structures as they fired at attackers coming from two directions: north and south. They defended themselves with a musket that fired at close range, like a shotgun with small lead rounds, and with bows and arrows—and, likely, atlatl darts—tipped with ferrous projectiles. A sword-blade tip embedded upright in the ground provides another eerie indication of the battle. This was more than just a skirmish, as might have characterized Captain Gallego’s 1542 storm through the countryside (Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:430–431; also see below).

Previous studies indicate the types of evidence expected in battlefield contexts. Some of the correlates of conflict include widespread burning and high frequencies of clustered and fragmented projectile points, including fragmentation in specific ways (Seymour Reference Seymour2014, Reference Seymour, William and James2015b). Mathers and Marshall (Reference Mathers and Mathers2020:27–28) have proposed similar battlefield correlates that are specific to the Coronado expedition—including the presence and predominance of sixteenth-century military artifacts indicative of loss in combat and high levels of artifact fragmentation, among other factors.

Among the battle-related items recovered from this site inferred to be Suya are copper and iron crossbow bolt heads, copper and iron projectile points, a sword tip and sword guards (quillons), complete and fragmentary daggers, a possible pike fragment, chainmail, jack-of-plate armor, an armor rosette, sword belt buckles, lead shot of various calibers, matchlock and wheel lock parts (springs, hammer, trigger guard, wheel lock axle shaft), gun cleaning worms for muskets and pistols, decorative pieces for musket and crossbow stocks, and possible sling stones. Dozens of Sobaipuri O’odham arrowheads, once probably coated with poison (Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:406, 429; Obregón in Hammond and Rey Reference Hammond and Rey1928:162; Tello Reference Tello1891:438–439), are clustered in areas with the densest concentrations of Spanish military items. In addition, two bronze cannon have been recovered from the site. As noted, the first was on the floor of a securely dated Coronado expedition structure. The other exploded during the battle, as inferred from the cavity in the side of the barrel and its context along the main arroyo in the heart of the settlement where artifact densities and conditions suggest the most intensive portion of the battle took place.

Together, the evidence indicates that this was an early sixteenth-century settlement. The only credible option for this settlement is that it is Suya—also referred to by scholars as San Geronimo III. The distinctions are substantial between this site and Chichilticale and all the other known Coronado expedition sites in Arizona that are limited-use sites used as trailside camps, making this the most viable explanation, as the next section will discuss.

Places Denoted in Narrative Accounts

Three types of “places” are distinguishable in and can be inferred from documentary sources that relate to the Coronado expedition and other potential entradas and group types that are therefore expected as archaeological “sites” along this portion of the Coronado expedition route. Each place class is characterized by the expectation of very different material culture patterns based on length of use or occupation, group size, range and intensity of activities, and other factors, which, in turn, permits distinctions within the archaeological record as classes of sites. Specifically, the documentary record describes behavior and places that provide hints about the presence of a settlement, a two-month-long encampment, and many overnight trailside camps.

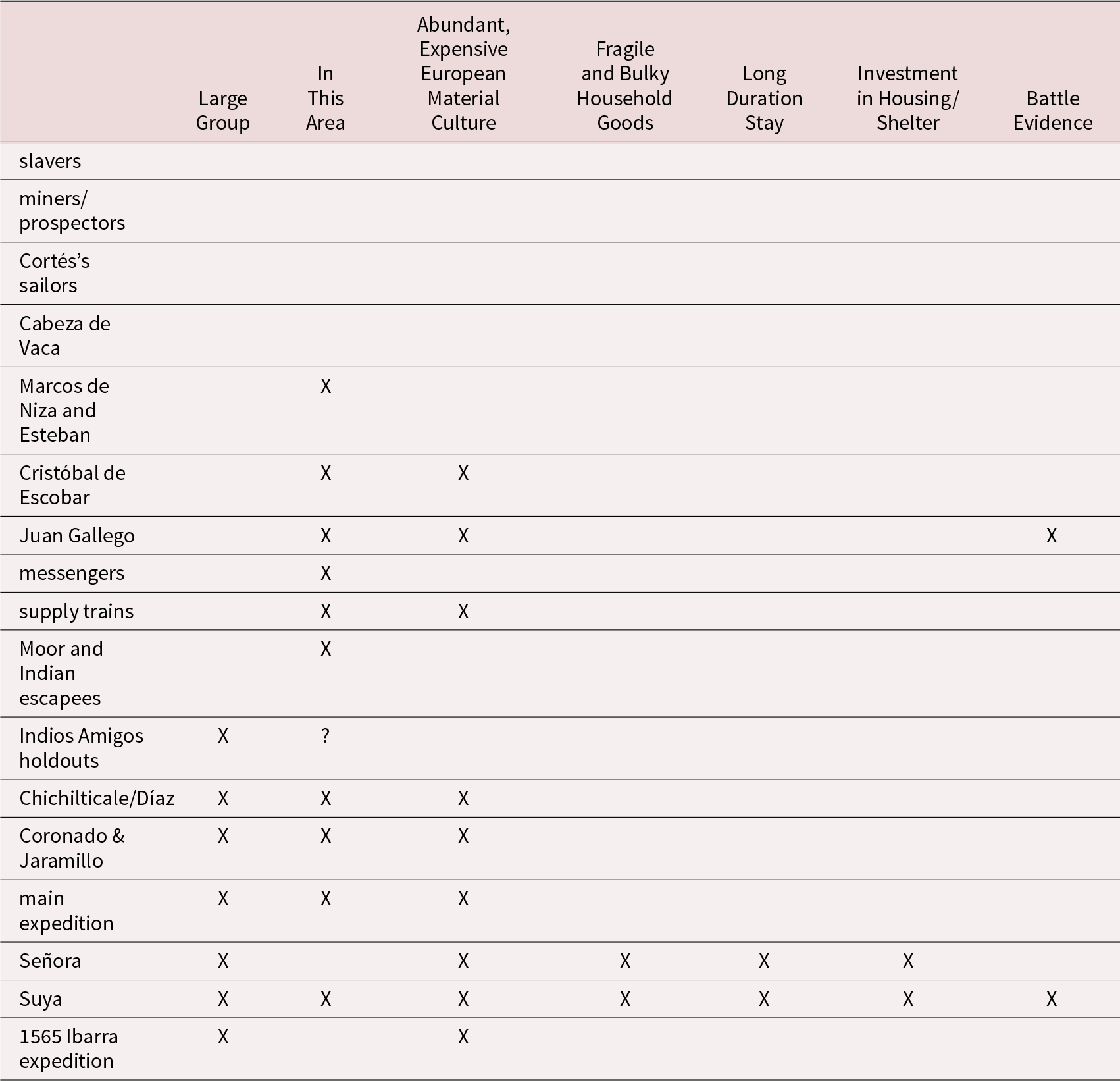

Most of the “places” expected for the Coronado expedition qualify as trailside camps, as would the “places” expected from other entradas that potentially ventured into this area. These sixteenth-century European expeditions and the smaller undertakings, jornadas, and entradas into this general region were merely passing through and therefore can be further evaluated for their match to the evidence by whether they (1) were this far north, (2) constituted a large enough group to leave temporally appropriate and abundant evidence, (3) had a stay of sufficiently long duration, (4) were able to access expensive European material culture, (5) were in possession of fragile and bulky household goods, (6) were able to invest in labor and materials for permanent housing, and (7) produced evidence of a pitched battle. Each of these conditions has clear material-culture correlates that can be studied in the archaeological record. These conditions pertain to the evidence found at the largest site in the Santa Cruz Valley (inferred to be Suya) and are consistent with the documentary record regarding Suya. As shown in Table 1, Suya is the only historically referenced place where all of these conditions apply. For this reason, we can rule out many of the smaller entradas because they have no possibility of accounting for the site referenced here as Suya.

Table 1. Criteria for Distinguishing and Explaning this Site and Its Characteristics.

Most of the activities in the sixteenth century in this region were undertaken by small groups that can be immediately eliminated from consideration as an explanation for this Santa Cruz Valley site. None of the other entradas into this area would have resulted in a site of the character indicated. The physical size of the Santa Cruz Valley site, as well as the density and diversity of material culture, indicates that the settlement resulted from an official expedition occupied by a sizable population of residents who had substantial European belongings and weaponry, including cannon supplied by the viceroy. Another such presence does not occur until 150 years later, in or after the 1690s, when Father Kino and the Jesuits began accessing the area, but that presence still did not approximate the size of the Coronado expedition.

Evidence for the intensive nature of the occupation at the Santa Cruz Valley site also eliminates the many smaller official trips within the auspices of the Coronado expedition, including messengers and supply trains that passed along the trail—between Mexico City and Tierra Nueva—individually or collectively. Their sites would look much like trailside camps, involving relatively few people and short, though repeated, stays. As one example, Cristóbal de Escobar brought livestock north to Coronado before the main expedition left for Cíbola, but his passage, although impactful, was still fleeting (Escobar in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:540, 564). Captain Juan Gallego carried messages and supplies back and forth on the trail, presumably on a routine basis, but again, this would have involved relatively small groups and comparatively short stopovers. For example, when northbound, Gallego and 22 reinforcements encountered the expedition as it retreated south in early AD 1542. Before arriving there, he had moved fast throughout the tierra de guerra and attacked and pillaged settlements along the way (Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:431). He had no intention of staying for any length of time or of settling there.Footnote 6 He even took revenge on the O’odham residents around Suya (Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:431), an act that would have made any small European settlement there especially vulnerable. He did propose establishing a new settlement just north of the tierra de guerra (Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:428), in the despoblado between Suya and Chichilticale, but this never materialized (Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:428; Seymour Reference Seymour2025a).

Even the smaller subsets of the expedition members who decided to stay as the expedition was withdrawing in 1542 (Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:429, 430) would not likely have established residence in the middle of the war zone that included Suya (200 leagues [965 km] from Culiacán). Some of these people were invited to stay at Cíbola, but the danger inherent once entering O’odham territory and beyond to the south seems clear from the devastation of Suya and also from documentary content. Texts record the shrieks from enemy Indians, deaths of horses, the wounding of a Spaniard with a poison arrow, and the lack of rest and food because Natives were up in arms all the way south through this area until reaching Petlatlán (or Petatlán; Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:429).

Small trips and ventures of other types are immediately eliminated as candidates for this exceptionally large site in the Santa Cruz Valley because of the low frequency of temporally relevant artifacts and features expected for small forays. These slave-trading and wildcat-mining operations, had they occurred, would have resulted in an archaeological signature consistent with short-term camps. This inference can be gleaned from the Cabeza de Vaca account, in which he noted that Christian slavers “were moving about over the country” and that he was able to follow the trail to the Christian slavers, traveling 10 leagues (50 km) and passing three Native villages where they had slept (Hodge and Lewis Reference Hodge and Lewis1990:112). The objective of finding minerals and slaves meant they were moving between locations as they searched. Had those types of entradas accessed southern Arizona, they would have passed through quickly, moving regularly along the route and therefore would have left scant evidence, which is consistent with short-term camps. If they had stayed a bit longer, their footprint would look more like Chichilticale than Suya in our sample, and the assemblages might be more specialized. They are therefore disqualified as explanations for the Santa Cruz River site.

The abundant and expensive, difficult-to-obtain items of European material culture found at the site inferred to be Suya disqualifies many more potential explanations that might involve non-Europeans. The occupants of the Santa Cruz River site clearly had access to the full range of European household goods and weaponry, including some of the most expensive firearms of the time (matchlocks, wheel locks, and bronze cannon, as well as crossbows). The occurrence of these in the assemblage eliminates any of the many ethnic subgroups that might have splintered off from the expedition, including slaves and domestic servants—that is, “Moors and Indians” who departed the expedition in Sonora in the spring of 1540 (e.g., Coronado in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:255) or anytime thereafter. Others would have lacked access to these types of items in any quantity, including the Indios Amigos who may have moved independently along the route and some who later remained in the Tierra Nueva at or near Cíbola after the termination of the expedition (“some of our [Indian] allies stayed behind among [the settlements]”; see Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:428). The assortment of artifacts found at the Santa Cruz River site and the character of features present assist in understanding the general identity of the people residing there and eliminate people who would not have had access to the full range of European goods.

Although Fray Marcos de Niza and Esteban may have traveled along this route, they would have left only light material-culture traces, so their reconnaissance does not account for the evidence at the Santa Cruz River site. Their presence is likely indistinguishable from—and their camping areas along the same routes subsumed by—those of later travelers, including at the impressive townsite of Suya. Perhaps evidence would be visible north of where their trail might have diverged from that taken by the main expedition (Seymour Reference Seymour2024). Fray Marcos’s return trip would have been even less distinguishable owing to the fast rate of travel, avoidance of occupied places, and previous dispersal of most if not all of his trade items.

Cabeza de Vaca, his three companions, and their sizable Native escort might have veered this far north, yet there is no definitive evidence of this in the documents. However, there is evidence that they passed through Corazones (what would become San Geronimo I) in 1536 (see Castañeda and see Jaramillo in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:409, 512), which is 50 leagues (240 km, or 150 mi.) from Suya. Yet, Cabeza de Vaca and his three companions were naked and barefoot and had little or no European material culture items that would identify them as Spaniards. Seeing archaeological evidence of this group would require identifying unusual rock art or evidence of the Natives with them. In this case, and in each of these instances just reviewed, evidence of their transit would be consistent with a trailside camp, the attributes of which were discussed previously.

The sheer abundance and the clear patterning of European artifacts at the Santa Cruz Valley site indicates a large and differentiated group, as do the permanent Spanish-built structures, which eliminates many of the smaller trips and shorter stays through the area as viable explanations. Consequently, slavers, prospectors, wayward sailors, and Cabeza de Vaca can be eliminated from the possibilities of explaining the Santa Cruz Valley site on the basis that they did not get this far north this early. Even if they did, the size of their group, the shortness of the stay, and the visibility of their material culture would be insufficient to account for the character of this Santa Cruz Valley site.

The two-month winter camp at Chichilticale established during the 1539 reconnaissance by Díaz and Zaldívar could potentially have explained this first site, or at least muddied the claim for Suya. However, that place has now been identified (Seymour Reference Seymour2025a) and is an order of magnitude different from the Santa Cruz Valley site. A useful comparison is made between Chichilticale, which was occupied for about two months but where they had no intention of staying, and the Santa Cruz Valley site, inferred to be Suya, which was established as a permanent townsite whose occupation was only a few months longer. As noted, it is the expectation of permanency rather than the actual length of stay that influences the amount of investment in features, modifications to the terrain, and the nature of the associated artifacts.

Four months after the Díaz reconnaissance, Coronado passed through this region, perhaps with hundreds of people. Nonetheless, in his own hand, he conveyed that they were moving along at a fairly rapid pace—rather than lingering—because food was giving out. They could not even stop long enough to spell the horses (Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:256). He waited for only two days at Chichilticale, reaching Cíbola 73 days after leaving Culiacán (Anonymous in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:497). Consequently, his encampments and those of the people with him should look like trailside encampments, reflective of short layovers by a sequence of captains and their enourages under his command.

All available evidence indicates that none of the other known expeditions supported or undertaken by Guzmán, Cortés, or Ibarra reached this far north. According to Cabeza de Vaca, Native residents had not heard of Christians until they were 80 leagues (385 km, or 240 mi.) north of the Río Petután (Petatlán), which was also the northernmost river to which Guzmán came (Hodge and Lewis Reference Hodge and Lewis1990:111; this may be the Río Yaqui or Río Sonora near Hermosillo, which is at least 240 km [150 mi.] south of the international line). This observation was repeated by Marcos de Niza, who wrote, “I found other Indians who marveled to see me because they had heard nothing about Christians, on account of not having dealings with those back across the unsettled area” (Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:68), indicating at a minimum that there were pockets of terrain that had not encountered Europeans.

Cortés-sponsored voyages from AD 1532 and 1533 ventured north along the Gulf of California, and according to Cabeza de Vaca’s account, some sailors traveled inland to the area near Corazones and interacted violently with the residents before leaving (see Seymour Reference Seymour2024), but this may have been considerably south of the international line. Some of the marooned men from one of these ill-fated voyages may have traveled inland, but, even if they had reached this latitude, they would not have had the equipment and supplies found at this Santa Cruz Valley site.

Following the Coronado expedition, no official expeditions are known to have passed through or near this area, unless the 1565 Francisco de Ibarra expedition made it this far north, which does not comport with the evidence. According to Obregón, they were at Señora, and although the stories conveyed relate to the events that transpired at Suya—including a battle and the death of Alcaraz—the expedition was likely at Señora. Details supporting this notion are that no attack was recorded at the settlement of Señora, whereas the Santa Cruz Valley site has clear evidence of a battle, consistent with information conveyed in documents. Castañeda’s report of events at Señora indicates that a battle that killed 17 men-at-arms did not take place at the villa of Señora but rather some distance away at a pueblo on a height at the Valle de Bellacos (Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:406). This indicates that unless he neglected to report a battle, in a discussion about battles, then our Santa Cruz Valley site cannot be Señora because the site inferred to be Suya has clear evidence of a battle. Regardless, and importantly, even if Ibarra had visited the Santa Cruz Valley area of southern Arizona, they did not stay long enough to create more than a trailside camp. They remained among the locals for only a few days and demonstrated their muskets and versos (a cannon type that can be either breach or muzzle loading; see Seymour and Mapoles Reference Seymour and Mapoles2025) by blasting trees to impress the Natives into submission (Hammond and Rey Reference Hammond and Rey1928:167; Obregón Reference Obregón1988 [1584]:152).

Sufficient information is provided in Obregón’s (Reference Obregón1988 [1584]), Hammond and Rey’s (Reference Hammond and Rey1928:162, 163, 166, 168) and Tello’s (Reference Tello1891:438–439) discussions to indicate that Ibarra’s expedition was in fact at Señora but that Obregón was telling stories about Suya. Among this evidence—that they were farther south and that they turned toward the east before reaching southern Arizona—is that the destination of the Ibarra expedition was Paquimé (e.g., Casas Grandes), situated to the east (Seymour Reference Seymour2024). This eastward turn is indicated by the fact that a clear culture area boundary is mentioned, with occupied villages to the east of Señora (Obregón in Hammond and Rey Reference Hammond and Rey1928:163, 173), which is consistent with settlement distributions at the time in that region. However, at that time, there was no such culture area boundary to the east of Suya that was characterized by occupied villages of rectangular structures, which is why the Europeans referred to the area beyond (east of) Chichilticale as the despoblado (see discussion in Seymour Reference Seymour2025a).

How do we, as archaeologists, see this culture boundary in the documentary record? First of all, I understand that the Spanish sense of cultural manifestations in Indigenous America do not map well onto our own or onto Native senses of cultural borderlands, as one reviewer noted and as Sauer (Reference Sauer1932) suggested. But this is an irrelevant argument, because this archaeologist, at least, has not assumed that these early Europeans were ethnographers or that they observed scientific evidence consistent with modern constructs. Instead, they were describing manifestations they observed, and they sometimes captured the essence of certain aspects of material culture and their physical environment in a way that can now be used to distinguish between ways of life and physiographic features. Geographers and other scholars do the same with geographic attributes. When a pass or river is described, their attributes are incorporated into the search criteria, and attempts are made to map them onto the modern landscape. The same is done in archaeological analysis, but we further understand that housing type, for example, provides information equivalent to the mention of a distinctive physiographic feature.

Housing type can be one of these distinctive material-culture categories that captures considerable information that can then be translated into cultural boundaries, such as degree of mobility and therefore adaptation, climate, and social-organizational attributes. Differences in housing types can be obvious to the untrained explorer’s eye, and these features convey considerable information to the archaeologist. Consequently, this is one area where we do not need to trust that Obregón, Ibarra, Jaramillo, or Castañeda understood what they were looking at from a modern scientific perspective (that is, the way we as anthropologists might). We must, however, incorporate into our argument the assumption that their descriptions of what they were seeing were sufficiently accurate to have some relation to the real world, as they seem to be. For example, Obregón’s house-type descriptions can be demonstrated to be valuable in this way. He described rectangular adobe-walled structures with flat roofs (Obregón in Hammond and Rey Reference Hammond and Rey1928:173) versus (elongate oven-shaped) houses made of mats or those made of grass (Obregón in Hammond and Rey Reference Hammond and Rey1928:163; also see Jaramillo in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:512, 519: “At this pueblo of Los Corazones. . . . They have their dwellings, which are several huts [ranchos]. After setting up poles very much in the manner of ovens, though much larger, they cover them with mats”). House types and other material culture categories represent indices useful for distinguishing between culture groups (see Seymour Reference Seymour, Flint and Flint2011), just as passes and arroyos mentioned are useful in identifying key landscape features to look for on the ground when searching for the route, especially those that are distinctive and not widespread. The intermediate step in the analysis involves creating material, spatial, and physical correlates for relevant historical observations, which can be recognized in the archaeological record. Culture groups are not equivalent to ethnic groups, political or social groupings, or biological groups. Nonetheless, when historical chroniclers pass from one culture area to another, clear culture area distinctions are sometimes obvious in their descriptions. Stated another way, these early observers commented on the types of houses they were seeing based on distinctive construction attributes that archaeologists may use to distinguish between culture groups by recognizing their archaeological correlates.

Rendering “casas de terrado, de estado y medio, de tapia” (Obregón Reference Obregón1988 [1584]:156–157) as roofed houses with high adobe walls and thus rectangular houses (Obregón in Hammond and Rey Reference Hammond and Rey1928:173, 174) and “casas de terrado y esteras de cañas” as roofed houses of cane (reed) mats that were likely elongate (Obregón in Hammond and Rey Reference Hammond and Rey1928:163; Obregón Reference Obregón1988 [1584]:148) is another layer of interpretation.Footnote 7 Yet, even the mention of a different housing type is a basis for considering that a boundary, a difference, may be indicated. This is especially the case when they say that these people with houses of adobe walls “were more advanced than those met before” (Obregón in Hammond and Rey Reference Hammond and Rey1928:173). This is one of the ways archaeologists define culture groups. Archaeologists use the spatial, physical, and material attributes conveyed in documentary sources to derive inferences about cultural practices that may have relevance to adaptation, behavior, and culture and therefore may be preserved in consistent and predictable ways in the archaeological record. Current understandings and interpretations based on archaeological data are consistent with reed mat–covered houses being used by the O’odham (and perhaps other groups once occupying Sonora). It also seems that flat-roofed, rectangular, adobe-walled structures are consistent with the Ópata and presumably other contemporaneous groups. So, although we are handicapped in that we do not know specifically what Ópata housing was like or that of other contemporaneous groups (other than what the archaeological record has divulged), we do know from extensive archaeological work what various early lowland O’odham housing looked like, so at one level, this distinction is useful. One way that it is useful is that Obregón recorded a change in his description of housing type, layout, and density as the Ibarra expedition traveled between different biomes and physiographic settings. They were describing cultural and environmental attributes that are also used by archaeologists to distinguish culture areas. Adding strength to this inference that people using one kind of housing were different from those using another is the additional information provided: they dressed differently, ate different foods, or interacted differently with their neighbors while living in different climates with specific types of terrain characterized by distinct vegetation.

In comparison, another documentary source discussed the similarity of people who shared certain housing types. For example, Castañeda observed that the people of Suya and Señora were the “same,” stating that the people of Suya (San Geronimo III) were “of the same quality as those of Señora [with the same] dress, language, rituals, and customs, as with everyone else up to the depopulated area of Chichilticale” (my translation; Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Cushing Flint2005:472). These are the people with the reed mat–covered houses. In addition, what these sources described in the documents for Señora is consistent with what has been found archaeologically at Suya, Chichilticale, and elsewhere in the O’odham area (Seymour Reference Seymour2024, Reference Seymour2025a). Given that we now know that one subset of the O’odham (Sobaipuri) was at Suya and Chichilticale (Seymour Reference Seymour2024, Reference Seymour2025a), and we know that the people and practices at Señora were the same or similar, we therefore know what to expect. One expectation (of many) that is met by the available evidence is for reed-mat houses that occur along the presently defined route corridor.

Three Classes of Places

Places identified in (e.g., Suya and Chichilticale) or inferred from (e.g., trailside camps) documentary sources present expectations for the attributes that should characterize archaeological sites. These classes of places are sufficiently distinct in terms of length and intensity of use that there should be measurable physical, spatial, and material differences between them. In fact, they are discernable. These define the site types expected within the Coronado-expedition landscape in Arizona. Site typologies are useful because they convey information about the site in a condensed form that has larger interpretive implications. Each archaeological site class has specific attributes that provide data useful for distinguishing sites within that class from those in other classes on the basis of length of stay, size of occupying group, and other behaviorally relevant factors.

Using the modeled attributes and expectations based on documentary content and behavioral properties, we can assess the nature of the archaeological sites actually encountered, and, in turn, evaluate their relationships to places referenced in the documents. The differences conveyed in documentary accounts are clearly discernable in the archaeological sample and, as noted, three site types were differentiated on the basis of expectations for length of stay using the types of places indicated in the documents: short-term trailside camps, a two-month-long encampment, and a large habitation site that was intended to be “permanent.”

Trailside Camps

Expeditionary members were moving from place to place with the objective of going from point A to point X, which, of course, resulted in numerous encampments along the way—the number depending on the rate of travel and route chosen. Trailside camps are inferred to have been used for a one- to two-night stay on the way north and perhaps on the way south by the expedition, and also as messengers, supply trains, and others moved repeatedly and periodically along the route. But importantly, travelers had no intention of remaining for any length of time in each location, so these camps also represent limited-use (a limited range of activities or a wider range of activities over a short period of time) sites. Many, if not most, of these trailside camps would have been used repeatedly for short periods throughout the expedition, resulting in a gradual accumulation of evidence and a hardening of camp footprints. These are expected to nonetheless exhibit patterns characteristic of short-term occupancy and a limited range of uses. As with Campo Cascabeles described above, Paraje del Malpais—a published example of this site type—has surficial tent clearings or sleeping circles, rock art, and artifacts, one of which is diagnostic of the Coronado expedition (Seymour Reference Seymour2023). These two sites are entirely consistent with expectations derived from the documentary record.

Chichilticale / Longer-Term Encampment

The relatively longer-term nature of up to two months at the winter encampment of Chichilticale was inferred from documentary content (see Seymour Reference Seymour2025a). A two-month stay would result in more intensive use and a greater range of activities—and, therefore, the loss, breakage, repair, and discard of a greater number of artifacts than at an overnight encampment. As a greater range of activities took place over the weeks, a greater number of artifacts would find their way into the archaeological record. Feature footprints should be more visible, if for no other reason than surfaces became more compacted and ash and fire-cracked rock accumulated. Although investigations and visitation throughout the San Pedro Valley were likely undertaken by the stranded Díaz contingent, the tedium of waiting in an indeterminate circumstance caused by the snow and cold is often visible in evidence of equipment repair and cleaning, as well as crafting—tasks that might be kept to a minimum at overnight encampments and saved for longer stays.

The number of people inhabiting a location will increase the density of artifacts and features and may result in marked spatial patterning, as is seen at Chichilticale. Discrepancies in the documents regarding the number of Spaniards was resolved by using Captain Juan de Zaldívar’s (Flint Reference Flint2002:253) own testimony; he was captain with 16 horsemen, along with Díaz. How many domestic servants, slaves, family members, and Indios Amigos might have been present is up for debate. It seems, however, that an average of six to eight extra people per European (that is, European head of household or male European) is a reasonable guess, balancing the fact that many were young and had few if any support staff, whereas others were of high rank and likely had many. This master-to-servant and Indio Amigo ratio inference is based on the figures provided in later documentary accounts about the number of people killed and the number of survivors at Suya in relation to the inferred number of people who remained at the townsite (see above). This exercise indicates how to interpret the patterning found at this and other archaeological sites with reference to subsets of the detachment, and how this conveys social information. The social dynamic and environmental impact presented with perhaps 100–150 people is much different from the one presented if there were only 18 European men (and all their horses). The extensive spatial layout at Chichilticale is likely explained by the possibility that there may have been 100–150 people, if retainers and domestic servants and Indios Amigos had accompanied the 18 Europeans. This is about the same size as the Suya population.

There had been no expectation within the group that the detachment would be staying at Chichilticale. The goal was to proceed as far as Cíbola and then to return with a report of what had been found. Time was of essence, because the expedition was coalescing in the south. The Díaz detachment was stopped a little over halfway to its intended destination by excessive snow and cold weather. The travelers had not planned to remain in place, nor did they intend to remain at Chichilticale for an extended period, even after they determined that their northward progress was barred. The lack of preparation and the absence of intent to stay for an extended period suggests that modifications to and investment in the terrain would have been low and on par with those anticipated for trailside encampments, although perhaps a bit more visible. On-the-spot measures to keep warm in what was judged to be excessively cold conditions might include increased evidence of firepits and spoil-rock and ash piles and their placement closer to tent clearings than might be the case in more favorable weather. Perhaps there would be evidence of constructions that were more substantial than simple tents—even semi-subterranean floors, as may be indicated by a deeply buried (40 cm) ferrous froe—or use of Sobaipuri O’odham structures, as is apparent in one instance. Placement on the tops of landforms took advantage of direct sunlight rather than being subject to cold-air drainage in low-lying areas.

Researchers had expected that the two-month-long winter encampment at Chichilticale would eventually be found in Arizona. In fact, one reason Chichilticale was sought with such determination was because it was a named place, so it became important owing to the fact that certain people, including Coronado, were known to have been there. It was thought to be the only expedition-named place in Arizona. Sufficiently distinctive attributes (e.g., a ruined roofless house, at the edge of the wilderness, among settled people) were noted in documentary accounts that there was hope that it could be found on that basis (e.g., Seymour Reference Seymour2025a) and then verified and distinguished from other sites by other forms of evidence. Yet the primary reason it was so specifically sought is that scholars thought that because of its longer-term use by the expedition, there might be hope of actually finding it. The assumption was that overnight encampments might be invisible owing to their minimal use and therefore few artifacts, whereas Chichilticale might have more definite features and a greater frequency and wider range of artifacts, including some that were specifically diagnostic of the expedition. There is considerable truth to this, because finding Coronado expedition campsites is like finding a needle in a haystack: the longer the stay, the more people stayed there; and the more times people (and the chance storm or attack) went through, the greater the likelihood of tangible evidence being left, and the lower the likelihood that disturbance processes would have removed all evidence. Consequently, although archaeologists expected to find longer duration trailside camps, there was a lower expectation that those types of limited-use, trailside sites would leave preserved evidence that could be distinguished as relating to the expedition. Fortunately, those expectations were wrong.

Suya: A Large Settlement