Introduction: ritualizing the domestic sphere

Domestic architecture has long been recognized as representing more than a passive backdrop to everyday life (e.g. Carsten & Hugh-Jones Reference Carsten, Hugh-Jones, Carsten and Hugh-Jones1995; Hillier & Hanson Reference Hillier and Hanson1984; Parker Pearson & Richards Reference Parker Pearson and Richards1994) and houses as ‘living participants in prehistoric social action’ (Bailey Reference Bailey and Samson1990, 20). This is particularly true in later prehistoric Britain, where specialized ritual monuments are extremely rare and the domestic sphere becomes the focus for ritualized action in ways which are not characteristic of earlier periods (e.g. Bell Reference Bell1992; Bradley Reference Bradley2003; Hill Reference Hill1995). Far from reflecting zones of activity undertaken in the course of daily life, many artefacts recovered from Iron Age roundhouses were not the result of casual loss or abandonment, but were deliberately deposited in highly structured ways (e.g. Webley Reference Webley2007). These so-called structured deposits (cf. Hill Reference Hill1995; see Garrow Reference Garrow2012 for a full discussion) are often associated with the foundation and abandonment of buildings, though I will demonstrate that they also occur at important ‘transitional’ moments within the life of the household. It is thus the selective deposition of material by Iron Age communities (rather than the products of casual loss and discard) that we often observe in the archaeological record (Bradley Reference Bradley2005, 208–9). Brück (Reference Brück1999a) has demonstrated the pitfalls of drawing distinctions between ritual and rationality, sacred and profane, in pre-modern and non-western societies, but notwithstanding these arguments, it becomes clear that in many cases roundhouses reveal more to us about their social and cosmological role in people's ontological understandings of the world than the ‘practicalities’ of everyday life: a reversal of Hawkes’ (Reference Hawkes1954) ‘Ladder of Inference’.

‘The living house’: houses as ancestors

It [the Maori meeting house] was simultaneously regarded as a living being and as a way of representing the passage of time. (Bradley Reference Bradley2005, 51)

The study of houses in terms of their ‘life histories’ (e.g. Tringham Reference Tringham and Samson2000, 127), ‘life cycles’ (Bailey Reference Bailey and Samson1990, 28; Brück Reference Brück1999b) and later, their ‘biographies’ (e.g. Sharples Reference Sharples2010), is well established. This has grown from an understanding—based, for example, on ethnographic evidence from the Batammaliba of Togo and Benin Republic (e.g. Blier Reference Blier1987) or the Zafimaniry of Madagascar (Bloch Reference Bloch, Carsten and Hugh-Jones1995a), and archaeological evidence such as ‘single phase’ Middle Bronze Age roundhouses in southern Britain (Brück Reference Brück1999b) or the wandering settlements of the later prehistoric Netherlands (Gerritsen Reference Gerritsen1999)—that, in many societies, a close temporal affiliation exists between the development of a physical ‘house’ and the natural cycles of the social ‘household’. In New Ireland (Küchler Reference Küchler1987), as Gerritsen points out, ‘the house does not survive its inhabitant’ (Reference Gerritsen1999, 82) and in this way, ‘house and inhabitants are commensurable’ (Reference Gerritsen1999, 81). More recently, however, with the material turn and more symmetrical frameworks of interpretation regarding human and non-human actants (e.g. Latour Reference Latour2005), biographical approaches have been criticized as over-anthropocentric (Joyce & Gillespie Reference Joyce and Gillespie2015), with a move towards concepts such as ‘itinerary’ (Joyce Reference Joyce, Joyce and Gillespie2015). These criticisms of biography are valid in many cases, especially in relation to artefact studies where the approach was first and is perhaps most widely employed (e.g. Gosden & Marshall Reference Gosden and Marshall1999; Joy Reference Joy2009). As Joyce (Reference Joyce, Joyce and Gillespie2015, 28) points out, ‘objects … are not actually much like people’, and the study of their biographies necessitates multiple ‘reincarnations’ or cycles of life and death. Nevertheless, one could say that people are not much like people either, if one takes, for example, the circulation after death of plastered skulls in Neolithic southwest Asia or the Christian relics of Medieval Europe: these ‘people’ too outlive such constrained implementations of biography.

Turning back to domestic architecture, we know from ethnographic accounts that houses can be perceived as human bodies. In the Maori meeting house (van Meijl Reference van Meijl and Fox1993), for example, veranda=face, porch=brain, ridge-pole=spine etc., while amongst the Batammaliba of Africa (Boivin Reference Boivin, Boivin and Owoc2004a), the clay used to make houses is akin to flesh and the clay-based plaster applied to the surfaces of walls is referred to as ‘skin’. Similarly, Eriksen's (Reference Eriksen2016) study of Viking longhouses reveals etymological origins for architectural elements in human body parts (‘window’=vidauge=‘wind eye’, ‘gable’=gavl/geblan=‘head, skull’, etc.), and ‘footprint’ is still used today in English to refer to the ground-plan of a building. Taken together with the apparent ‘cremation’ and ‘burial’ of some high-status halls (which may well have had names), Eriksen argues that we should not perceive houses in these societies merely as representations of bodies but actual bodies. She prefers to see Viking longhouses as ‘house-bodies’, in much the same way as, for example, Alberti & Marshall (Reference Alberti and Marshall2009) describe ceramic vessels in first-millennium ad northwest Argentina as ‘body-pots’. Indeed, perceiving only representation and metaphor risks viewing the past through a post-Enlightenment, Cartesian lens which separates humans from their material world. As such, the biographical study of a house (and particularly the house(s) which I present below) is not in conflict with a flat ontological framework and in fact enhances our understanding of the relational identities of house and inhabitants. Biographical approaches place buildings at centre-stage, rather than relegating them to supporting roles in anthropocentric narratives.

‘Nested’ and ‘cyclical’ biographies

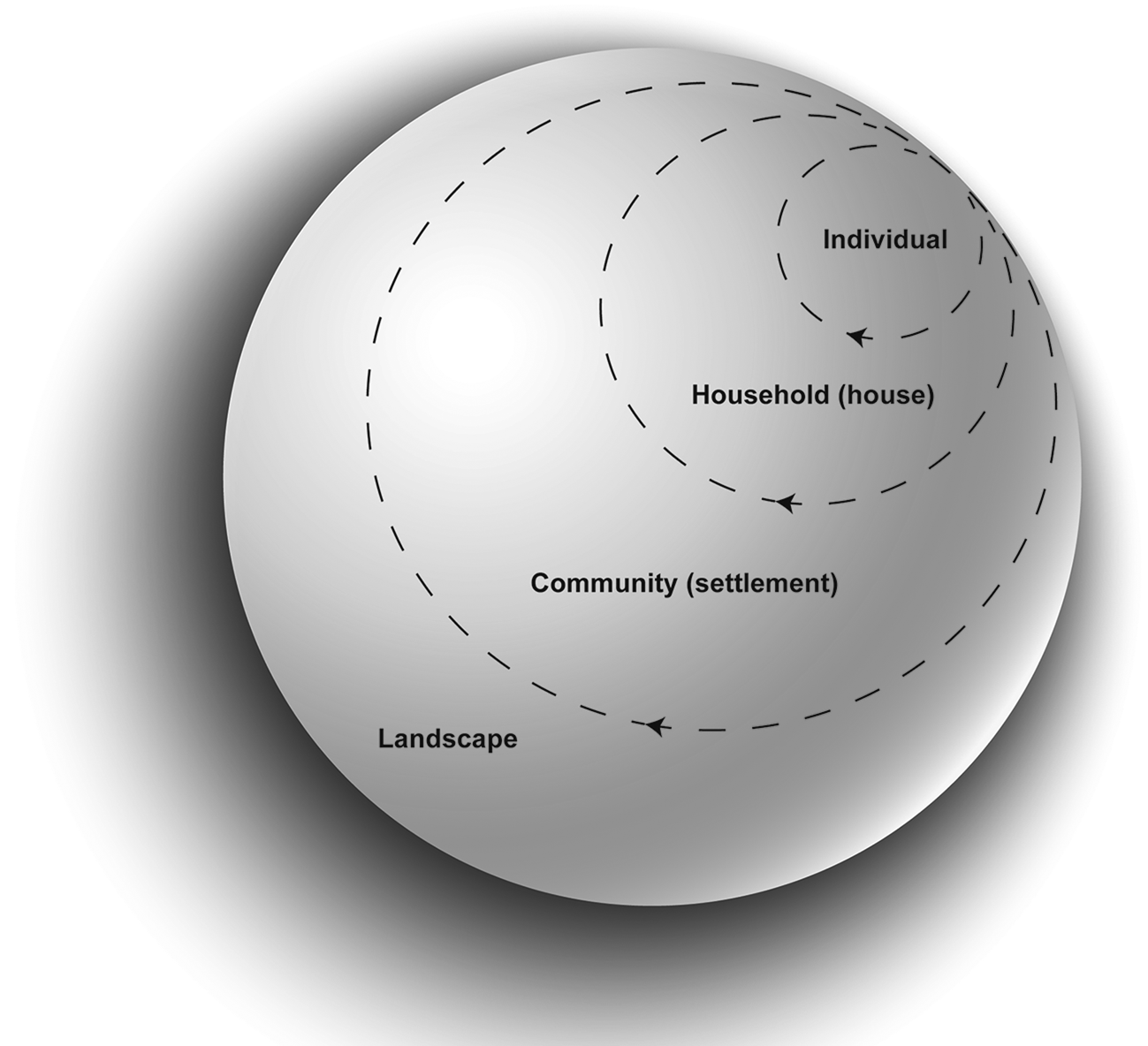

On long-lived sites, choices by one generation of inhabitants would have been constrained and shaped by the decisions of their predecessors (cf. Gosden & Lock Reference Gosden and Lock1998, 3); their presence would be continually felt and reflected upon, not least through the material remains encountered (frequently and unintentionally) in the course of everyday life. The partial subsidence of House 2 at the Late Neolithic site of Opovo in Serbia due to its construction over a former infilled well (Tringham Reference Tringham and Samson2000, 123) is just one example, and is mirrored at the Iron Age hillfort of Broxmouth in southeast Scotland (see below) by the slumping of a series of Middle Iron Age roundhouses into the infilled ditch over which they were built (Armit et al. Reference Armit, Kershaw, McKenzie, Armit and McKenzie2013, 93). Such frequent encounters with the past (in the past) highlight that the division of continuously occupied, long-lived sites (whether they be whole settlements or individual house-stances) into distinct ‘phases’ of activity artificially divides their biographies into discrete episodes, conceptually severing these intimate ties between generations. Instead, we might think of biographies operating simultaneously at a variety of scales, from settlements and their surrounding landscapes stretching back into ancestral or ‘mythical’ time to (in a British Iron Age context) ramparts or gateways refurbished every few decades, and smaller features such as grain-storage pits or animal byres having annual cycles, and so on. Any inhabitant living within this settlement may draw, perhaps simultaneously, on all of these temporal and spatial references in the formulation of their own social identity. In order to reflect this adequately, we must replace single overarching biographical frameworks with concepts of ‘nested’ biographies which can simultaneously situate the individual, the household and the community at various scales in space and time (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Biographies, like identities, are nested, and different aspects of the archaeological record can inform us about identities at different social scales. Although depicted as a series of circles, in reality the categories are far more blurred, and ultimately relational to one another. The use of a sphere is designed to indicate that each scale of biography has both a spatial and temporal dimension.

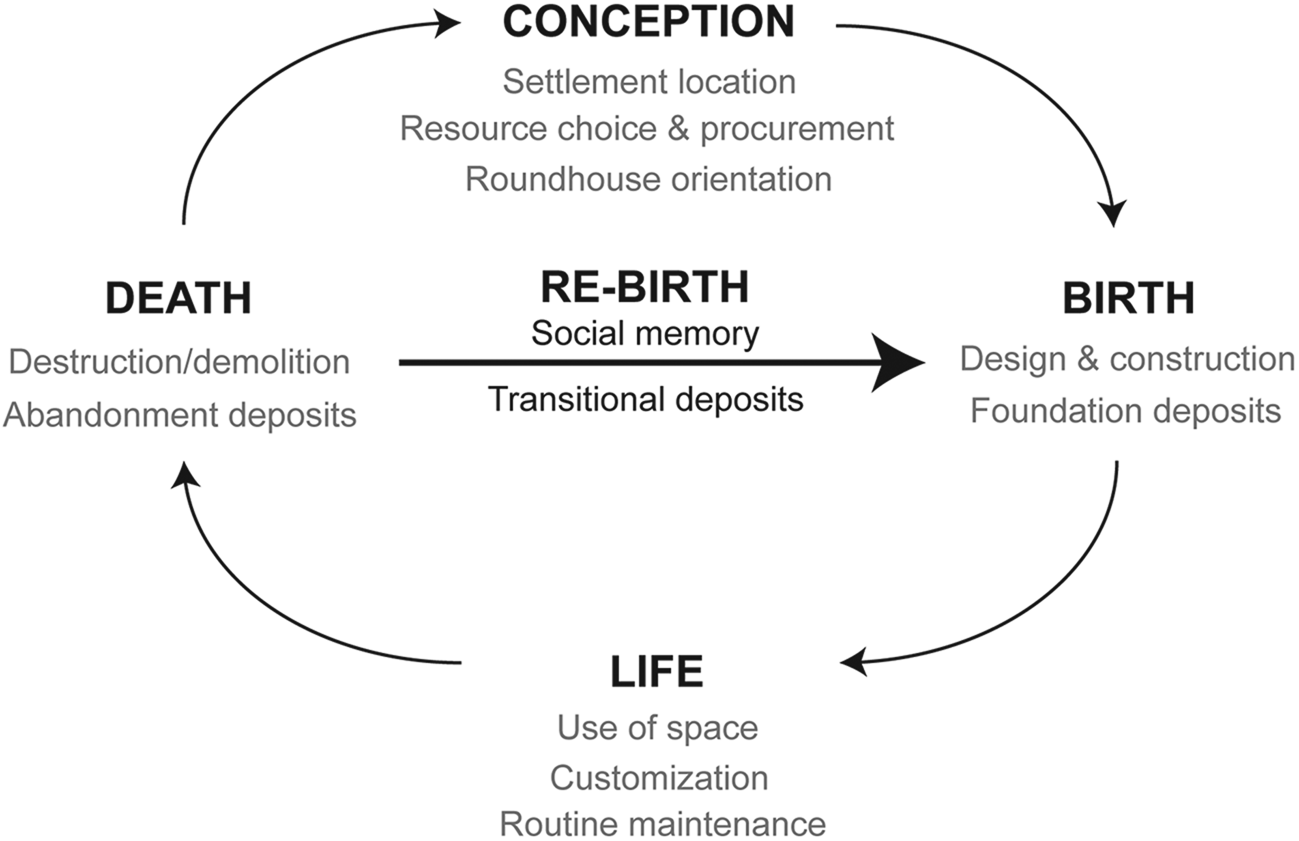

Furthermore, since the ‘conception’ of a structure draws on a pre-existing settlement landscape, can we really think of biographies as linear phenomena with distinct beginnings and ends? With careful maintenance, individual houses can often ‘outlive’ their human occupants; analysis of Neolithic houses at Çatalhöyük, Turkey, for example, indicates that the use-lives of individual house posts could extend over several generations (Hodder Reference Hodder2012, 194, fig. 9.8). As such, houses themselves can become central figures in the biographical narratives of successive households, and may have been vehicles through which people articulated relationships with past, present and future (Gerritsen Reference Gerritsen and Jones2008, 148–9; Gosden Reference Gosden, Gwilt and Haselgrove1997, 304). The biography of these buildings is therefore not only nested, but also cyclical (Fig. 2). Each re-birth would have imbued the structure, and its household, with ever deeper layers of social memory, onto which the identity of the new household was grafted.

Figure 2. The cyclical nature of roundhouse biographies, with increasing layers of social memory added with the completion of each successive cycle (after Büster Reference Büster2012). The actions accompanying each ‘stage’ are illustrative rather than exhaustive.

Having said this, focusing on the conventional biographical stages of conception, birth, life and death will, of course, obscure the smaller episodes of transformation which a building (and its inhabitants) may undergo during its/their lifetime (many of which will be invisible archaeologically). Ethnographic evidence, and rare archaeological cases where finer-grained resolution is possible, alert us to these more subtle episodes of change. At Çatalhöyük, for example, micromorphological analysis of house walls has identified up to 700 re-plastering episodes, over a period of roughly 70 years; that is, around one per month (Hodder & Cessford Reference Hodder and Cessford2004, 22; Matthews Reference Matthews and Hodder2004). In rural Rajasthan, certain parts of the Balathal roundhouse are re-plastered not only to purify the building upon the birth or death of an individual, but also on a more frequent basis, for example, when visitors are expected, or to demarcate a change in function of particular areas (Boivin Reference Boivin, Boivin and Owoc2004b, 172).

Closely linked to concepts of biography, and hardly divisible from any biographical approach to prehistoric architecture, is the material of the structures themselves (e.g. Bille & Sørensen Reference Bille and Sørensen2016). In many societies, certain substances and materials are perceived to be not only physically, but conceptually and symbolically, more or less appropriate for certain uses (Boivin & Owoc Reference Boivin and Owoc2004; Hurcombe Reference Hurcombe2007; Meskell Reference Meskell2005). Among the Ma'ohi of eastern Polynesia, for example, certain tree species, such as the breadfruit, were restricted to the construction of elite residences and sacred houses, and trees cut from sacred woods or those grown in temple precincts could only be worked by high-status specialists (Kahn & Coil Reference Kahn and Coil2006, 342). Other construction materials may have been seen in a similar light. Returning to the Balathal houses of rural Rajasthan, the type of soil selected for re-plastering events is based on the nature of the space to be demarcated or the type of event referenced (Boivin Reference Boivin, Boivin and Owoc2004b); red-coloured soils are, for example, particularly auspicious and are used for sacred places within the home (such as areas around the hearth and places for prayer), as well as on special occasions such as weddings and festivals (Boivin Reference Boivin, Boivin and Owoc2004b, 171).

Renewal of structural fabric may also be necessary for cosmological as well as social reasons. The dulling and darkening of rock carvings through weathering is considered by both the San peoples of South Africa and Aboriginal communities in Australia to represent the reclaiming of the images by the spirit world, with frequent re-carving and re-painting required to maintain contact with the world of the living (Ouzman Reference Ouzman2001; Taçon Reference Taçon, Boivin and Owoc2004, 39). As such, periodic replacement by past societies of various structural elements of the house may have been considered necessary to ensure the continued vivacity of structures and to renew conceptual links with previous generations in the maintenance of social identity.

Transitional deposits

Structured deposits are ubiquitous features of later prehistoric architecture, and appear to be associated with specific moments in the biography of buildings and their inhabitants. These deposits often seems to have accompanied either the foundation or abandonment of structures (e.g. Armit Reference Armit2006, 247; Bender et al. Reference Bender, Hamilton and Tilley2007, 150, fig. 6b, col. pl. 3b; Webley Reference Webley2007), as is particularly clear, for example, in the ‘wandering settlements’ of the later prehistoric Netherlands (Gerritsen Reference Gerritsen1999) and single-phase roundhouses of the southern British Bronze Age (Brück Reference Brück1999b). It is at these same sites that a traditional biographical framework of analysis has been relatively unproblematic. In Iron Age Britain, however, roundhouses can also be re-built on the same house-stance, blurring the division between one house biography (one household) and the next. In these cases, the idea of ‘nested’ and ‘cyclical’ biographies becomes more useful for their interpretation, and alerts us to the fundamentally different relationship between house and household in these communities. Furthermore, these extended biographies are necessarily reflected in less formal distinction between foundation and abandonment deposits, with the two being synonymous in a continual process of decay and renewal (see, for example, Nakamura & Pels’ Reference Nakamura, Pels and Hodder2014 discussion of deposits at Çatalhöyük). These may be better understood as transitional deposits, marking significant moments of transformation within the life of a structure and its household (just as we might understand rites of passage throughout the life of an individual). Thinking about deposits as transitional also helps us to overcome the building/living dichotomy and to acknowledge that the construction of architecture is never really ‘finished’, but is an ongoing process (Harris Reference Harris, Bille and Sørensen2016; Ingold Reference Ingold2013).

Ancestral homes: the Broxmouth roundhouses

Having outlined the potential of biographical approaches in the study of later prehistoric architecture, I now want to apply the concept to the well-preserved Late Iron Age (Phase 6) roundhouses at Broxmouth hillfort in southeast Scotland. Though biographical frameworks have been commonplace, for example, in the study of tell sites of Neolithic southwest Asia (e.g. Bailey Reference Bailey and Samson1990; Kay Reference Kay2020), the timber architecture of later prehistoric roundhouses across much of the British Isles does not lend itself easily to such approaches. The exceptional survival of several structures at Broxmouth, due largely to their construction in stone (at least in later iterations), thus presents a rare opportunity to examine the social and cosmological role of the roundhouse in prehistoric identity over time.

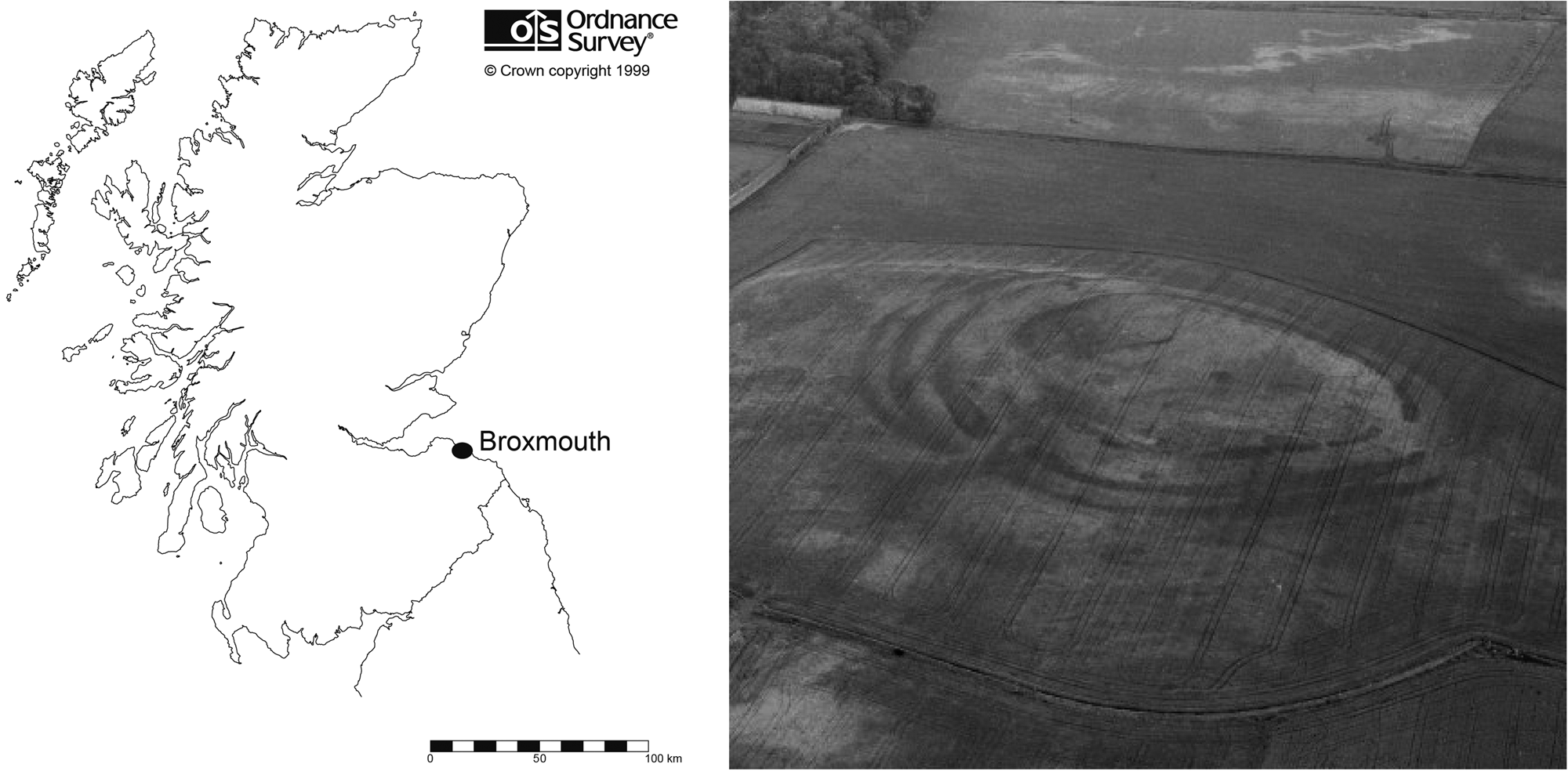

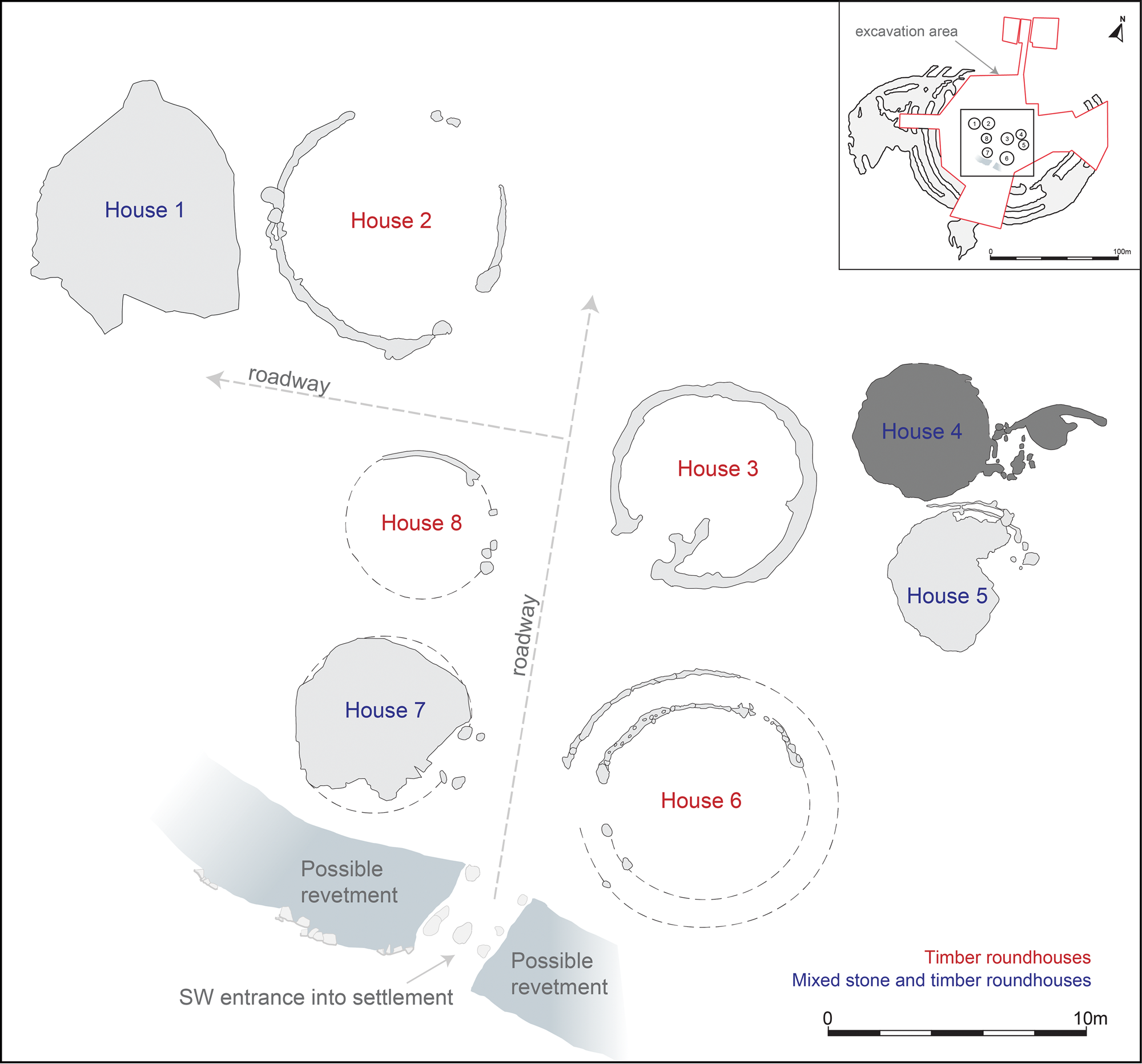

The settlement at Broxmouth, which lay on the East Lothian coastal plain roughly 600 m from the coast (Fig. 3), was occupied (apparently continuously) for around eight centuries (c. 600 bc–cal. ad 200) over some 32 generations (Armit & McKenzie Reference Armit and McKenzie2013, 513). Although the site is known as a hillfort, it began as an unenclosed settlement, and the multiple ramparts and ditches that developed later were maintained for only a couple of centuries. When the Phase 6 settlement (Fig. 4)—the last phase of occupation, with Bayesian modelled dates of c. 100 cal. bc–cal. ad 155—was established, some 20 generations after the site was first inhabited, it is likely that Broxmouth was a well-known place in the landscape, with its own ‘history’ and its own stories. Around a third of the 158 AMS dates indicate the presence of redeposited material across various phases of the site (Hamilton et al. Reference Hamilton, McKenzie, Armit, Büster, Armit and McKenzie2013). This, together with the progressive truncation of features belonging to Phases 1–5 (with the exception of several Middle Iron Age houses surviving in sunken ditch fills or under ramparts), points to frequent encounters with the material remains of the past by the Late Iron Age inhabitants; not least, in the digging of scooped house-stances, wall-slots, pits and post-holes during construction and maintenance of the Phase 6 roundhouses. Burials within the settlement interior were apparently respected and protected by successive generations, and even appear to have influenced the location of some of the Phase 6 buildings, such as House 2, whose northernmost entrance post-hole was aligned on/located adjacent to a Phase 1 crouched inhumation. This demonstrates that the ‘conception’ of the Late Iron Age settlement (though ultimately erasing the material remains of its predecessors) was very much dictated by the material traces of the past.

Figure 3. Broxmouth location map and aerial photograph of the site as a crop-mark. (SC 1323319 ©Historic Environment Scotland/John Dewar Collection.)

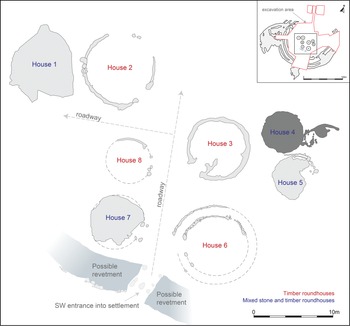

Figure 4. The surviving Phase 6 settlement, showing those roundhouses constructed in timber and those that included both timber and stone elements at some point during their life. It is likely that House 1 had a turf wall which did not survive later plough truncation.

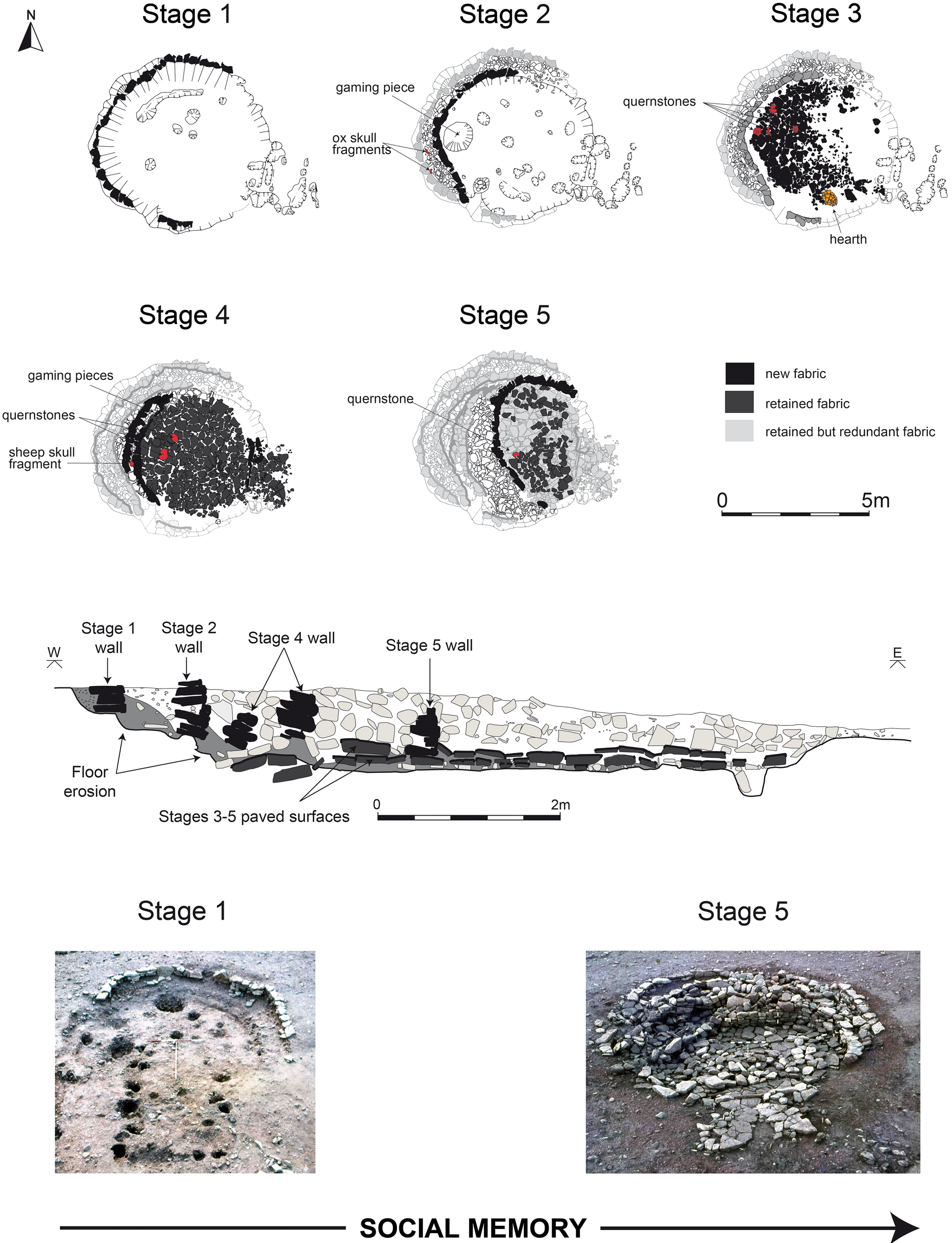

The near-complete obliteration of features associated with the Phase 1–5 inhabitants of the hillfort lies in stark contrast to the Phase 6 roundhouses themselves, in which the retention and referencing of earlier occupation of house-stances (through several biographical cycles) became a central feature of their evolution. Several of the Phase 6 roundhouses (Houses 4, 5 and 7) displayed complex developmental sequences which saw them begin life as timber or partial timber structures with earthen floors and become slowly encased by stone walls and paved floors (Büster & Armit Reference Büster, Armit, Armit and McKenzie2013). Crucially, these modifications do not appear to have been structurally necessary: there is no evidence for instability in the existing roundhouse fabric. Furthermore, new walls (and later, paved surfaces) were not dismantled and replaced, but were built in front (and on top) of one another. There appears to have been no attempt to re-use the previous structural fabric, with the acquisition of new raw materials and re-building inside existing footprints not only requiring large investments of labour and materials, but ultimately compromising useable space within the roundhouse interior. In the case of House 4, which underwent the most (five) re-builds, the structure more than halved in size, from 38.5 sq. m to a mere 15.2 sq. m in its final iteration (Fig. 5); this must have had a significant impact on its functional capabilities and the number of individuals and activities that it could accommodate. Furthermore, the sealing of large pits must also have had a profound effect on the functions performed within the building, with activities presumably having to be undertaken in new ways or moved to different buildings (see Kay Reference Kay2020 for a similar discussion at Çatalhöyük).

Figure 5 (opposite). Plans and sections illustrating the biography of House 4 and the gradual decrease in its internal area over time (as indicated by the photographs of the stage 1 and stage 5 roundhouse).

Generational turnover

What is remarkable, at least in a British Iron Age context, is the resolution of the chronological framework for occupation at Broxmouth, as provided by AMS dating and Bayesian modelling of the site, and what this tells us about the tempo and rhythm of the changes taking place over its roughly 800-year history. Significantly, for the Phase 6 roundhouses, it tells us that the replacement of walls and paved surfaces appears to have taken place on a generational or bi-generational basis (i.e. roughly every 40–60 years: Büster Reference Büster2012, 148; Büster & Armit Reference Büster, Armit, Armit and McKenzie2013, 151); the inherent error ranges of even Bayesian modelled AMS dates do not allow us to be more specific than this (Hamilton et al. Reference Hamilton, McKenzie, Armit, Büster, Armit and McKenzie2013). This suggests that physical ‘re-structuring’ of the roundhouse was central to the negotiation and communication of new identities at significant times in the life of the household, perhaps upon the loss (death) or addition of new members to the group, as Brück (Reference Brück1999b) and Gerritsen (Reference Gerritsen1999) have suggested in the respective studies discussed earlier.

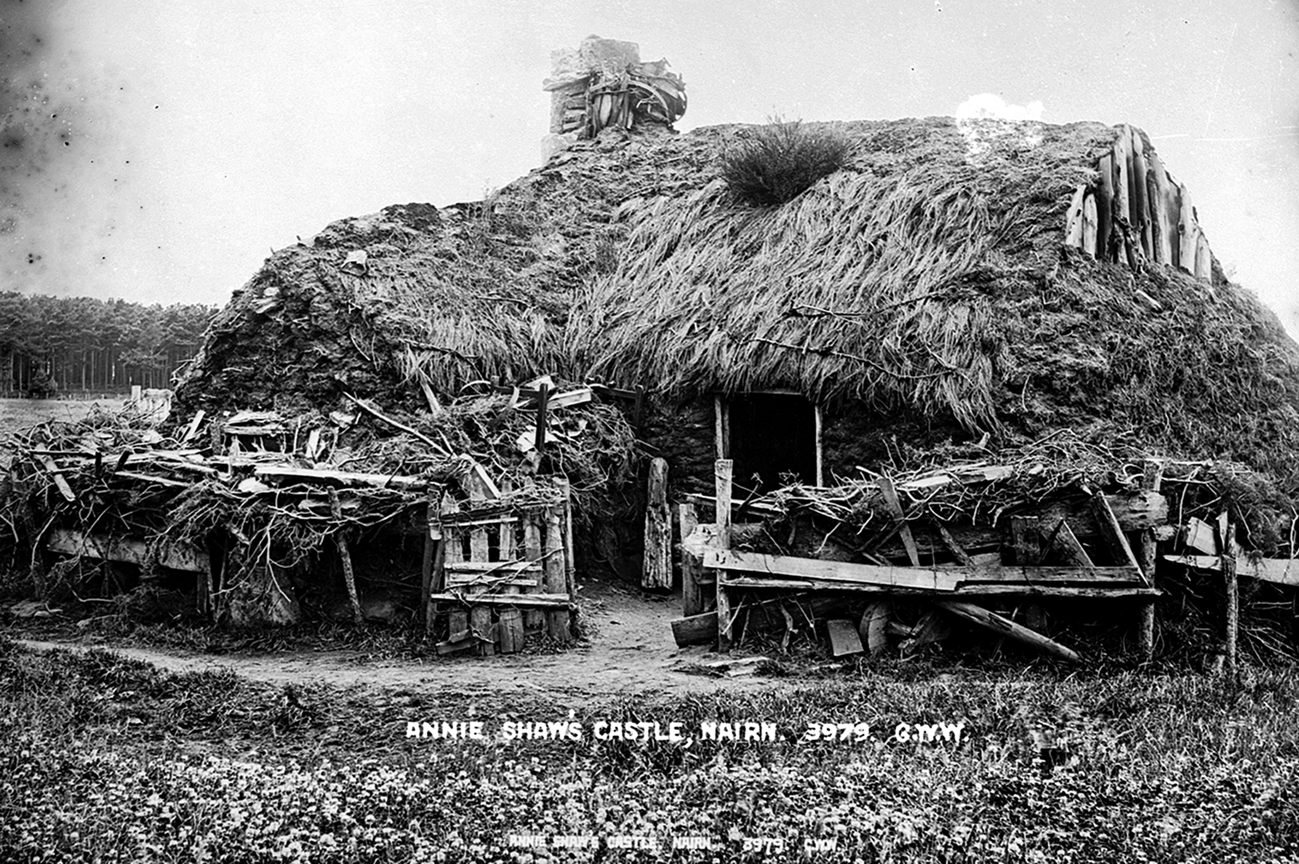

What is also significant is that the material manifestation of the Broxmouth roundhouses appears to have been integral to this identity building. We have already noted that when each successive modification took place—when each new skin was grafted onto the roundhouse—the previous structural fabric was left intact. In this way, the stone walls of previous generations of Broxmouth inhabitants not only metaphorically, but physically, territorialized the assemblages of inhabitants (people, animals, objects, ancestors) within (cf. Harris Reference Harris, Bille and Sørensen2016; Maxwell & Oliver Reference Maxwell and Oliver2017; Normark Reference Normark2009). This piecemeal approach to maintenance has been noted in the vernacular architecture of more recent times, and has created visible cumulative biographies: ad hoc repair (with the retention of earlier structural fabric) undoubtedly provided ‘Annie Shaw's Castle’ with a visible ancestry and elevated its status to recognized and important local landmark (Fig. 6); note here the bipartite name of house and occupant (one giving identity to the other).

Figure 6. ‘Annie Shaw's Castle’, Nairn. (MS 379/E05211, University of Aberdeen.)

We have also noted that several of the Broxmouth roundhouses (e.g. Houses 4, 5 and 7) began their life in timber, or partially in timber, and gradually became encased in stone (Büster & Armit Reference Büster, Armit, Armit and McKenzie2013). As such, prehistoric communities may have shared similar attitudes towards the affordances of stone and timber to those witnessed among ethnographically documented societies in Madagascar. In these societies, wood is used to build houses of the living while stone is reserved for the tombs and standing stones of the ancestors (cf. Parker Pearson & Ramilisonina Reference Parker Pearson and Ramilisonina1998, 311), reflecting a cosmology in which biological and social ageing is conceptualized as a kind of ‘hardening’ (Bloch Reference Bloch, Carsten and Hugh-Jones1995a; Reference Bloch, Hodder, Shanks, Buchli, Carman, Last and Lucas1995b, 215). Through periodic and successive transformation (through their multiple ‘lives’), the Broxmouth roundhouses may thus have served as the material manifestations of the history of lineages: epitaphs and memorials for the many generations of inhabitants which had called them home. This is perhaps particularly pertinent in a society which had no normative funerary tradition of formal cemeteries or grave monuments, instead choosing to incorporate the dead into the communities of the living, frequently within the fabric of roundhouses themselves (Armit & Ginn Reference Armit and Ginn2007; Brück Reference Brück1995). In this sense, a structure like House 4, with both old and new skin, may have been considered as a physical and conceptual bridge between past and present, between the world of the living and the world of ancestors.

Family ties and continuing bonds

The [Maori meeting] house was not a surviving trace of the ancestor's existence and agency at some other, distant, coordinates, but was the body which he possessed in the here and now, and through which his agency was exercised in the immediate present. (Gell Reference Gell1998, 253)

As is characteristic of many Iron Age roundhouses, structured deposits were abundant within the fabric and features of the Phase 6 buildings at Broxmouth, whose earthen floors had been deeply eroded by frequent sweeping-out of any casual or accidental debris: erosion which appears to have prompted the laying of the first paved floors in Houses 4, 5 and 7. Cached objects of this kind have often been described in terms of foundation and abandonment deposits, but the successive re-building of structures on the same house-stances at Broxmouth, and the nesting of buildings inside one another, necessitates that we conceptualize them as transitional deposits between one roundhouse (or one household) and the next, and as marking the careful negotiation of past and present.

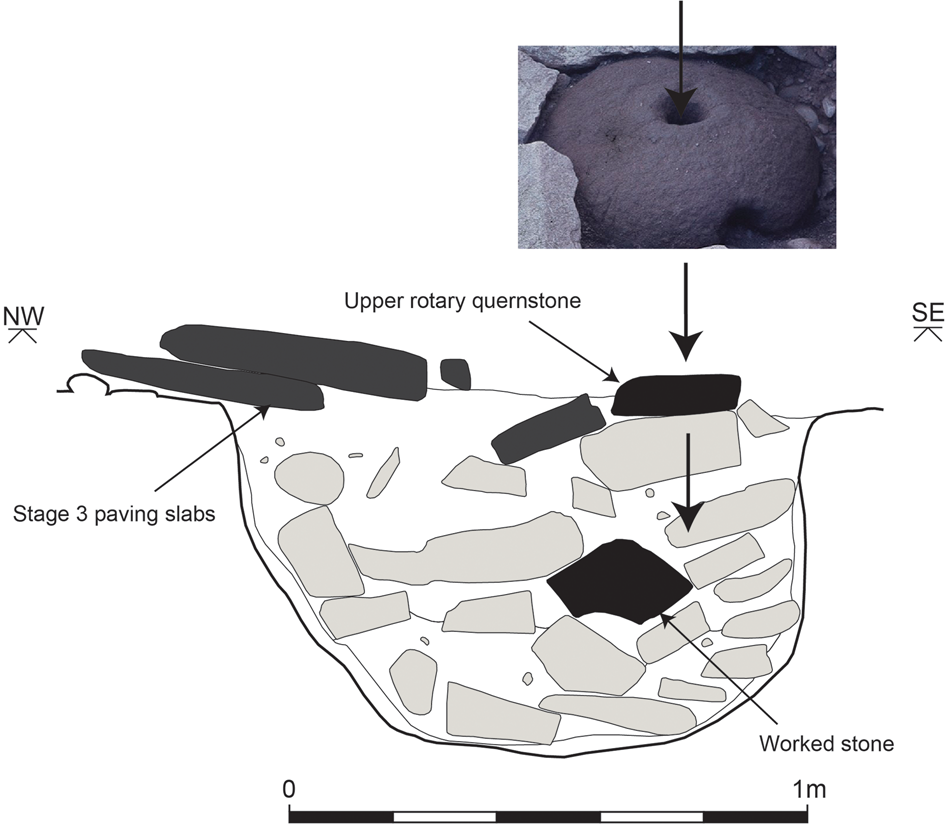

Links between past and present at Broxmouth are further demonstrated by a) the types of material chosen for deposition and b) the locations of these materials. These attest to the careful referencing (or citation: Borić Reference Borić2003) of previous structures (and households) by successive inhabitants. Ox-skull fragments placed at the base of the wall during the initial construction of House 4 are, for example, mirrored by the deposition of a sheep skull at the base of the wall in the fourth iteration of the roundhouse (Büster & Armit Reference Büster, Armit, Armit and McKenzie2013, 141–7; Fig. 7). Another mechanism for linking past and present in House 4 can be seen in the incorporation of deliberately broken quernstones into the paved surface of the stage 3 roundhouse, and their placement over the largest of the stage 2 pits (Büster & Armit Reference Büster, Armit, Armit and McKenzie2013, 143–7). Old and broken quernstones represent an obvious raw material for paving slabs, but (as is common with this particular artefact type) the deliberate fragmentation in some of the Broxmouth examples (McLaren Reference McLaren, Armit and McKenzie2013, 317), and their deposition over earlier features, suggest that they were being used in a more deliberate way. The upper rotary quernstone overlying the large stage 2 pit may even have provided a more direct and tangible bond between past and present, in that the feeder-pipe would have facilitated, for example, the pouring of votive libations into the feature below (Fig. 8); a similar interpretation has been proposed by Campbell (Reference Campbell1991, 133) at Sollas wheelhouse in North Uist. Another example of this phenomenon (albeit in a more conventional funerary context) is provided by the first-century bc cemetery complex at Goeblingen-Nospelt in Luxembourg, where a large ceramic vessel known as a dolium was (having had its base removed) placed over the grave chamber of a high-status female and formed a focus for offerings for at least 175 years (Metzler & Gaeng Reference Metzler, Gaeng, Le Brun-Ricalens, Brou, Valotteau, Metzler and Gaeng2009, 501–8; Fernández-Götz Reference Fernández-Götz2016, 175, fig. 9).

Figure 7. Fragments of ox skull (top) and sheep skull (bottom) deposited between wall facings during construction of the stage 2 and stage 4 modifications to House 4.

Figure 8. Upper rotary quernstone overlying a large stage 2 pit in House 4.

A more overt physical tie between successive generations of inhabitants of House 4 is represented by three antler gaming pieces (Fig. 9). These artefacts are unique to House 4 and are likely to have belonged to the same set. One of the gaming pieces was deposited during the infilling of the large pit (mentioned previously) which dominated the interior of the stage 2 roundhouse, while the other two were deposited during construction of the wall in the fourth iteration of the structure, some considerable time (and several generations) later. Presumably, these latter pieces were deliberately kept and cherished, possibly even played with. The playing of games is a recreational activity—literally ‘recreating the world through the reordering of reality’ (Hall Reference Hall2007, 1). These highly personal and tactile items (perhaps associated with a known, named individual) would thus have been particularly powerful as visual prompts for stories surrounding previous households and/or specific individuals, and in this tangible way would have created ‘continuing bonds’Footnote 1 between the living and the dead.

Figure 9. Group of three antler gaming pieces (probably belonging to the same set). The bottom piece (now very fragmentary) was deposited in the large pit shown in Figure 8, while the upper two were deposited several generations later at the base of the stage 4 wall. (Photographs courtesy of National Museums Scotland.)

Finally, we must consider two apparently ‘ordinary’ but no less significant items: two bone ‘spoons’ that were deposited during construction of the stage 1 and stage 5 walls of House 4 (Fig. 10). These represent the first and last deliberately deposited artefacts in House 4 (at least in terms of what we can recognize archaeologically), and they mirror each other not only in form but in the context of their deposition: tucked under successive walls of the roundhouse, at least five generations apart, and thus bracketing the use of this long-lived structure. As with the gaming pieces, it is interesting that these are small, personal and tactile objects. We cannot know the period of time over which specific oral traditions survived, but these paired deposits must be more than mere coincidence, and the deposition of the latter example appears to make deliberate reference to the former. Implying the retention of memories over such a long period of time in non-literate societies might seem like a stretch, but ethnographic evidence tells us that genealogical histories can persist for up to around 500 years (Ballard Reference Ballard1994), and similar time-depths are suggested for Maori oral traditions concerning the identity of particular houses (cf. Best Reference Best1927, 96). We can similarly envisage that the recounting of stories concerning household identity would have been ubiquitous in prehistoric communities, perhaps aided by similar objects to those described above (cf. Ahmed Reference Ahmed2004; Harris Reference Harris2010).

Figure 10. Two bone ‘spoons’ (deposited some five or more generations apart) at the base of the stage 1 and stage 5 walls during their construction. (Photographs courtesy of National Museums Scotland.)

We are forced to consider, then, whether the Phase 6 roundhouses at Broxmouth (or at least some of them), and House 4 in particular—which experienced the most re-builds and saw deposition of the most structured transitional deposits within its fabric—gradually took on the role of epitaph for particular households or genealogies: transformed over time into a ‘memory-box’ for the Broxmouth community. It is not insignificant that many of the artefacts deposited so deliberately and with such careful referencing of one another were hidden from view as the roundhouse was built up around them; this may have necessitated and reinforced the need to tell and re-tell stories to keep their memory (and the memory of their owners) alive; to know these stories was to be part of the community.

During final abandonment of the Phase 6 settlement, the scooped house-stances were deliberately infilled. Since they represented the last settlement activity at Broxmouth, infilling presumably did not take place to level the site for future occupation; the houses appear to have been deliberately ‘buried’ (cf. Eriksen Reference Eriksen2016). Significantly, AMS dates suggest that some of the infill material pre-dated the Phase 6 settlement by several hundred years and must therefore have been dug from older middens on the site, either for the deliberate infilling of these structures at the end of their lives, or incorporated into the original structural fabric, which subsequently collapsed or was deliberately toppled (Büster Reference Büster2012, 144; Büster & Armit Reference Büster, Armit, Armit and McKenzie2013, 150). In this final act of infilling we see the unification of the various generations of the Phase 6 inhabitants of Broxmouth into the realm of ancestors, and the transfer of the whole community into an agglomerated past where individual and communal, recent and mythical identities were united.

The social role of later prehistoric architecture

Consideration of the animated nature of domestic architecture in many societies around the world today, and archaeological evidence pointing to the close temporal association of house and household in the past, has demonstrated the continued value of biographical approaches in understanding the central role that these structures played in the lives of prehistoric communities. Analysis of the Late Iron Age roundhouses (and House 4 in particular) at Broxmouth has, however, demonstrated the limitations of conceptualizing biographies as unilinear trajectories moving through distinct categories from birth to death. Instead, we are confronted with the indivisibility of temporal scales (from deep, mythical past to everyday life) and the nested, cyclical and relational nature of biographies with blurred categorical horizons. The Broxmouth roundhouses have demonstrated that the very fabric of people's homes, and the deposition of emotionally and mnemonically charged objects (cf. Harris Reference Harris2010) within them, was central to the maintenance and negotiation of social identities at a number of scales. Furthermore, detailed consideration of the location and composition of such deposits has demonstrated that the spatial referencing and curation of objects was central to the creation and maintenance of enduring ties with the past, and the fundamental role of oral tradition in the communication and negotiation of identity across generations.

Though the specific nature of roundhouse construction and survival at Broxmouth lends itself to detailed biographical study, these buildings are by no means unique. Where stone superstructures survive, such as in the roundhouses of Atlantic Scotland, structured deposits are ubiquitous (e.g. Armit Reference Armit2003; Reference Armit2006; Campbell Reference Campbell1991; James & McCullagh Reference James and McCullagh2003) and remind us that complex, long-lived biographies were far more common than the floor plans of long-decayed and plough-truncated contemporary timber structures suggest. In a period lacking formal funerary monuments, and with a close physical relationship between the living and the dead in the domestic sphere, it comes as no surprise that houses played important roles in the formation of social identities for households and communities, and bound one generation to the next. Only by taking a more nuanced biographical approach, within high-resolution Bayesian frameworks, can we begin to unlock any real understanding of what it meant to call a roundhouse a home for the communities of Iron Age Britain.

Acknowledgements

The doctoral research upon which this paper is based was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and was undertaken as part of the Broxmouth Project, funded by Historic Environment Scotland. Thanks to Agni Prijatelj, Barbora Wouters, Ian Armit and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.