Highlights

What is already known?

-

• Traditional meta-analysis (MA) is resource-intensive, struggles with scalability, and suffers from reproducibility issues, limiting its efficiency and reliability.

-

• Automated MA (AMA) has advanced with machine learning and specialized tools, improving data extraction, statistical synthesis, and expanding beyond medical research.

-

• Integration challenges remain, including workflow fragmentation, analytical limitations, and interoperability barriers, hindering full automation.

What is new?

-

• This study presents a timely systematic and comparative analysis of AMA research progress and applications across medical and non-medical domains to reveal distinct patterns in implementation challenges and opportunities.

-

• This study introduces a structured analytical framework to systematically evaluate the alignment between technological solutions and specific meta-analytical tasks, ensuring more effective automation implementation.

-

• This study identifies gaps in current AMA capabilities and presents a roadmap for advancement, taking recent progress in AI, and specifically breakthroughs in large language models, into account.

Potential impact for RSM readers

-

• For researchers, it maps AI-enhanced AMA tools, boosting efficiency in MA and inspiring cross-disciplinary innovation through AI’s transformative power.

-

• For tool developers, it highlights gaps in AI-driven heterogeneity and bias assessment, urging advanced AI integration for scalable, interdisciplinary tools.

-

• For policymakers, it emphasizes the vitality of AI-powered AMA for evidence-based decisions and the need for standardization and investment in comprehensive systems.

1 Introduction

Automation has become integral to modern life; it is driving efficiencies across industries and is now transforming knowledge-intensive domains such as academia.Reference Schwab 1 While businesses have long leveraged automation for operational gains,Reference Brynjolfsson and Mitchell 2 scholarly research is now accelerating the adoption of AI-driven tools to enhance both efficiency and scalability in evidence synthesis.Reference Marshall and Wallace 3 Systematic literature reviews (SLRs) are a cornerstone of academic research and are also among the most resource-intensive academic endeavors, whose workflows stand to be revolutionized by recent advancements in natural language processing (NLP, a field of AI focused on enabling computers to understand and generate human language),Reference Kwabena, Wiafe, John, Bernard and Boateng 4 machine learning (ML, algorithms that learn patterns from data to make predictions or decisions),Reference Tsafnat, Glasziou, Choong, Dunn, Galgani and Coiera 5 , Reference Nedelcu, Oerther and Engel 6 and large language models (LLMs, a type of ML model trained on massive text corpora to perform advanced language tasks).Reference Khraisha, Put, Kappenberg, Warraitch and Hadfield 7 These technologies are accelerating automation in literature curation, data extraction, and synthesis, and thereby addressing the growing challenge of processing vast and rapidly expanding volume of scientific outputs.Reference Van Dinter, Tekinerdogan and Catal 8

Meta-analyses (MAs) represent a key methodology within the context of SLRs for aggregating quantitative findingsReference Cooper 9 , Reference Deeks, Higgins and Altman 10 for which the current technological advancements present both opportunities and challenges for further automation.Reference Van Dinter, Tekinerdogan and Catal 8 Conducting MAs is resource-intensive, often spanning months or years. With the explosion in the number of papers being published in academic databases, researchers have estimated that the average time to complete and publish a systematic review requiring five researchers is 67 weeks, with an approximate cost of US$140,000.Reference Borah, Brown, Capers and Kaiser 11 Moreover, robust MA reviews tend to require an engagement with 3–5 domain experts to ensure its thoroughness, reliability, and accuracy.Reference Higgins, Thomas and Chandler 12 Such heavy demands on time, human resource, and financial investment pose barriers toward getting timely evidence-based synthesis, particularly in disciplines where rapid and accurate decision-making is essential. Consequently, automation has gained traction across various MA stages to mitigate these constraints. Studies have applied AI-driven techniques to enhance efficiency in literature screening,Reference Xiong, Liu and Tse 13 – Reference Feng, Liang and Zhang 15 data extraction,Reference Michelson 16 – Reference Schmidt, Hair and Graziosi 19 risk-of-bias assessment,Reference Cheng, Katz-Rogozhnikov, Varshney and Baldini 20 and heterogeneity reduction.Reference Rodriguez-Hernandez, Gorski, Tellez-Plaza, Schlosser and Wuttke 21 Despite these gains, automation efforts remain fragmented, with uneven progress across stages, particularly in those requiring complex reasoning and synthesis tasks.

While these advancements contributed toward progress in streamlining various stages of MAs in isolation, no comprehensive undertaking has been made recently to assess the current state of research on the automation of MAs and to situate the existing gaps within the significant and evolving breakthroughs in AI and LLMs, which are increasingly capable of performing complex reasoning.Reference Ofori-Boateng, Aceves-Martins, Wiratunga and Moreno-Garcia 22 The only dedicated reviewReference Christopoulou 23 synthesizing automated MA (AMA) focused narrowly on clinical trials and identified 38 approaches across 39 articles that applied ML techniques to various stages of MA. However, it concluded that automation remains “far from significantly supporting and facilitating the work of researchers.Reference Christopoulou 23 ” Clinical trials generally involve standardized procedures and well-defined outcomes that enable automation, while other domains, such as education and social sciences, exhibit more heterogeneous study designs and data formats, making automation more complex. While informative, this clinical trial-focused review has limited relevance for broader AMA research, as it overlooks recent methodological developments and predates advances in LLMs that could transform automation opportunities. Aside from this work, semi-AMA (SAMA) has also emerged as an interim solution, shortening MA timelines while maintaining rigor through expert.Reference Ajiji, Cottin and Picot 24 However, SAMA depends on human intervention in key steps, such as study selection and results interpretation, which limits its scalability. Given these shortcomings, a comprehensive review of AMA progress across domains is urgently needed to harness AI’s full potential and address persistent limitations in evidence synthesis automation.

Therefore, this study critically examines the current state of automation in MA research, identifying existing approaches and challenges in preparation for the next wave of AI-driven breakthroughs that are poised further transform the field. It addresses a critical gap by providing the first comprehensive and systematic synthesis of AMA applications across both medical and non-medical domains using a structured analytical framework. Through this analysis, we highlight key challenges and opportunities in AMA and offer insights into its evolving role in quantitative evidence synthesis. Our study therefore makes three meaningful contributions to AMA:

-

• First, it presents a timely systematic and comparative analysis of AMA research progress and applications across medical and non-medical domains to reveal distinct patterns in implementation challenges and opportunities.

-

• Second, it introduces a structured analytical framework to systematically evaluate the alignment between technological solutions and specific meta-analytical tasks, ensuring more effective automation implementation.

-

• Third, it identifies critical gaps in current AMA capabilities—such as the need for deeper analytical integration and enhanced evidence synthesis—and presents a roadmap for advancement taking the recent AI, and specifically LLM breakthroughs into account.

2 Background

The following section explores the history and evolution of MA, tracing its development from a relatively nascent statistical technique to its current prominence in evidence synthesis across disciplines. The second section discusses our analytical framework that informs on technology adoption and task characteristics for conducting the AMA research process. These have helped lay out the research questions for this study.

2.1 History and evolution of meta-analysis

MA originated from the pioneering work by GlassReference Glass and Smith 25 in the late 1970s, who developed a statistical framework for synthesizing research findings across educational and psychological studies, formally coining the term “MA.”Reference Glass and Smith 25 The methodology expanded significantly into medicine and other scientific domains during the 1980s–1990s, particularly for analyzing randomized controlled trials (RCTs). This expansion was driven by the growing demand for evidence-based decision-making, enabling researchers to address contradictory results and overcome limitations of small sample sizes.Reference Egger, Smith and Altman 26 One landmark application in cardiovascular medicine evaluated statin use in reducing cholesterol levels by pooling data from numerous clinical trials to demonstrate clear benefits in lowering heart disease risks, which ultimately provided compelling evidence. 27 The field advanced further through more sophisticated statistical models and refined effect size estimation techniques,Reference Hedges and Olkin 28 enhancing the robustness of quantitative synthesis. The development of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines,Reference Takkouche and Norman 29 – Reference Page, McKenzie and Bossuyt 32 with its most recent 2020 update, established rigorous reporting standards that minimize bias and improve finding reliability. MA has become instrumental in healthcare research, and as the highest level of evidence synthesis,Reference Sackett 33 MA provides critical insights for clinical guidelines and public health policies.

However, the exponential growth in published research—exemplified by ScienceDirect (https://www.sciencedirect.com/) with 16 million papers from 2,500 journals serving 25 million monthly researchers—has challenged traditional MA approaches. The growing volume of literature has necessitated the development of automation tools to streamline and expedite the review process. Scholars anticipate that automated systematic reviews will revolutionize evidence-based medicine through real-time analysis capabilities and optimized workflows.Reference Tsafnat, Glasziou, Choong, Dunn, Galgani and Coiera 5 , Reference Van Dinter, Tekinerdogan and Catal 8 While various software packages (RevMan,Footnote 1 Comprehensive Meta-Analysis,Footnote 2 Stata,Footnote 3 and SPSSFootnote 4 ) support MA through features like effect size calculation and heterogeneity assessment, they are better characterized as “computer-assisted” rather than truly automated. For instance, RevMan, despite its user-friendly interface for MA, still requires substantial manual data extraction. Similarly, while Comprehensive Meta-Analysis offers advanced statistical modeling, and Stata and SPSS provide flexible analysis capabilities, they all demand significant user intervention and statistical expertise. In addition, the commercial nature and high licensing costs of them limit accessibility for researchers with limited funding.

Recent advancements in AI-driven techniques, including NLP, ML, and LLMs, have markedly improved the efficiency of MA. Automated processes now condense tasks—once requiring months and multiple authors—into days, leveraging enhanced computational methods. For instance, LLMs have demonstrated sensitivity approaching human performance in the initial screening of systematic reviews,Reference Matsui, Utsumi, Aoki, Maruki, Takeshima and Yoshikazu 34 illustrating their potential to streamline early AMA stages. Despite these improvements, full deployment of AMA remains in development, with current efforts limited in scope. Research has primarily focused on clinical trialsReference Christopoulou 23 and SAMA,Reference Ajiji, Cottin and Picot 24 where SAMA reducing timelines while relying on human oversight for rigor. This narrow emphasis restricts AMA’s broader deployment across diverse domains, highlighting an ongoing challenge in achieving comprehensive automation. Emerging AI “thinking models,”Reference Brown, Mann, Ryder, Larochelle, Ranzato, Hadsell, Balcan and Lin 35 – Reference Huang and Chang 37 capable of performing complex reasoning, offer a promising avenue to bridge this gap. These models could automate sophisticated synthesis tasks, such as heterogeneity assessment and statistical integration, thereby enhancing AMA’s precision and scalability. For instance, their ability to adapt reasoning to varied research contexts holds potential for wider application, which points to a critical opportunity to advance evidence synthesis automation.Reference Ofori-Boateng, Aceves-Martins, Wiratunga and Moreno-Garcia 22

2.2 Analytical frameworks for technology evaluation

Having a robust analytical framework is crucial to synthesizing data drawn from pertinent studies and in drawing meaningful conclusions. The choice of framework for technology evaluation depends on the relevancy of data collected and the research questions that have been posed to analyse this data for understanding aspects related to technology’s usage and its overall performance. Two analytical frameworks that can provide us with a comprehensive assessment on the usage of various information systems (ISs)/information technology (IT) systems are unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT), proposed by Venkatesh et al.Reference Venkatesh, Morris, Davis and Davis 38 , Reference Venkatesh, Thong and Xu 39 (for explaining user attitudes, their behavioral intentions, and overall acceptance of the technology in use) and task–technology fit (TTF), proposed by Goodhue and ThompsonReference Goodhue and Thompson 40 (for interpreting technology alignment with the proposed tasks that can lead to high-performance impacts). However, a key element missing in UTAUT is the disposition of the users, namely, users’ computer self-efficacy or their innovativeness in making best use of the technology; therefore, user expectancy (performance expectancy and effort expectancy) and contextual factors (facilitating conditions and social influences) have been proposed as extensions to UTAUT.Reference Dwivedi, Rana, Jeyaraj, Clement and Williams 41 TTF, on the other hand, posits that the effectiveness of technology adoption and its usage depends on how well the technology supports the specific needs of a given task. It emphasizes on characteristics of both the task and the technology to make a statement on task–technology fitness. If there is a good fit between task and technology, it increases the likelihood of technology utilization and leads to increased performance impact.

TTF explains technology adoption (e.g., data locatability, data quality, data accessibility, timeliness, technology reliability, and ease of use) by focusing on the actual usage of the technology which can in turn offer valuable insights on technology design and improvement strategies. We can delve deeper into the functional match between technology and tasks, which is particularly relevant for complex, multistage process like AMA, where task demands vary significantly at different stages. It lays a strong foundation to understand how technology characteristics would influence task behaviors and consequently the utilization of that technology for the given purpose, and finally to provide a measure of the performance impacts. These impacts could lead to further development of more tools and services already in the marketplace or lead to redesigning of tasks to take better advantage of the technology or to further embark on training programs to better engage users in using the technologies.Reference Goodhue and Thompson 40

In this study, TTF is applied at the task level, focusing on concrete AMA tasks at each phase rather than abstract task attributes.Reference D’Ambra, Wilson and Akter 42 , Reference Ali, Romero, Morrison, Hafeez and Ancker 43 By applying TTF to AMA, we can evaluate the suitability of automation tools across various stages of AMA and assess how well available technologies support the specific tasks and user needs at each stage.

-

• Task demands and technology support across AMA stages: The distinct stages of AMA involve different types of tasks with varying demands and levels of complexity. For instance, in the data extraction phase, automation tools must handle unstructured data from diverse sources, ensuring accuracy in identifying relevant studies and variables. In the synthesis stages, the technology needs to support complex statistical computations while ensuring methodological rigor. In the reporting phase, automation tools must generate clear, interpretable results that comply with reporting standards. At each stage, TTF is applied to examine how effectively technologies meet these task requirements.

-

• TTF across AMA stages: TTF emphasizes the alignment of technology with the specific tasks to be performed. In AMA, this approach ensures that automation technologies remain well-suited to the requirements of each task, leading to improved performance and greater user satisfaction.

The application of TTF in AMA allows for a richer understanding of how automation technologies can improve efficiency, accuracy, and user satisfaction. For instance, while UTAUT may evaluate whether researchers will intend to use automated tools in MA, TTF assesses whether these tools will improve accuracy and reduce time and labor requirements. Specifically, TTF in AMA helps enable evaluation across three critical dimensions: data quality assessment (reliability of automated extraction), system effectiveness (enhancement of the MA process), and user satisfaction (accessibility across expertise levels). This analytical framework has therefore been used in this study to share insights for optimizing AMA tools, advancing task–technology research, and improving user experience and performance outcomes.

2.3 Research questions

Having laid out the background of history and evolution of MA, this article applies TTF constructs to better inform on aspects related to AMA deployment, such as the current approaches in use, challenges being faced, future trends, and the overall impact on evidence synthesis. We provide a comprehensive review of the development of AMA over the past decade. Our review highlights how various tools are being applied across different disciplines and how they have developed over time to provide a comprehensive understanding of AMA in evidence synthesis. Accordingly, we have posed four research questions that will be addressed in this review. These are:

-

• RQ1 (Descriptive): What are the current landscape and key characteristics of AMA approaches?

-

• RQ2 (Analytical): How does our analytical framework illuminate the strengths and limitations of current AMA approaches within each information processing stage?

-

• RQ3 (Comparative): What are the distinct patterns in AMA implementation, effectiveness, and challenges observed across medical and non-medical domains?

-

• RQ4 (Future-oriented): What are the critical gaps and future directions for AMA development, and what obstacles need to be addressed to realize its full potential for evidence synthesis?

3 Methodology

This section details the methodologies that provide a prelude to the review process and for the presentation of our results. The review follows the PRISMA criteria in providing answers to the four research questions. Next, we introduce our information processing-centric model to evaluate the alignment between AMA tools and the specific tasks they are designed to support.

3.1 PRISMA process

Our investigation of automation in MA followed PRISMA guidelines, employing a systematic search strategy. The database search was restricted to “MA” terms to enhance precision. Broader terms, such as “systematic review,” were not included, as pilot testing indicated they mainly retrieved irrelevant records. Accordingly, the initial search employed the string (“meta-analysis” OR “meta analysis”) AND (automation OR automated OR “machine learning” OR “artificial intelligence” OR AI OR “natural language processing” OR “large language model” OR LLM), with title, abstract, and keyword field filters applied where available (e.g., TITLE-ABS-KEY in Scopus; [Title/Abstract] in PubMed), across PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, IEEE Xplore, and ACM Digital Library databases. This presented a preliminary overview of research activities within the stated field of interest, offering a broad yet comprehensive summary of the general characteristics of MA prevalent in existing literature. Next, we established clear inclusion criteria and practical constraints: (1) published from January 2014 to August 2024; (2) focus on explicitly MA-specific automation tools; (3) full-text availability with sufficient methodological detail (e.g., at least four pages with technical descriptions); and (4) shorter records (e.g., abstracts and posters) were excluded due to insufficient information and empirical or quantitative evaluations in automation techniques of MA. Table 1 details the eligibility criteria. Furthermore, to enhance coverage and overcome potential oversights from database-centric searches, we conducted bidirectional citation chaining “snowball” methods.Reference Goodman 44 , Reference Parker, Scott and Geddes 45 This involved both backward tracing (reviewing references cited in the retrieved studies) and forward tracing (identifying later works citing the selected papers) through Scopus and Google Scholar, expanding our temporal scope to 2006–2024. This approach not only expanded coverage by incorporating relevant gray literature and emerging frameworks but also established thematic linkages between foundational methodologies and their contemporary implementations.

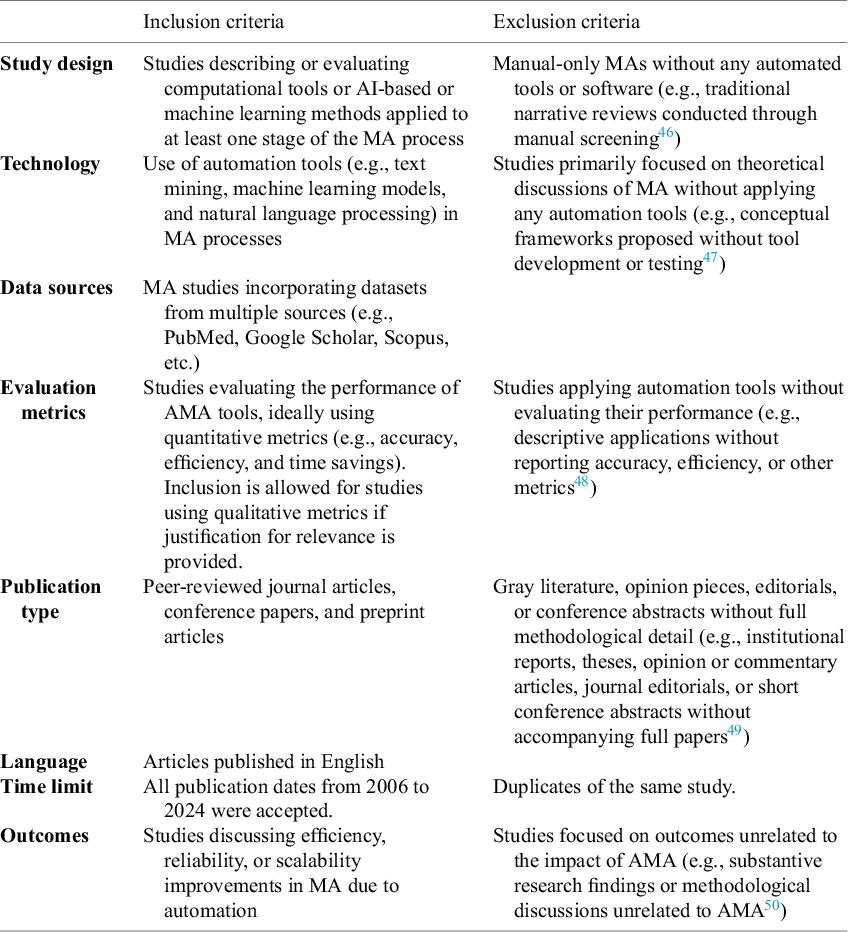

Table 1 Criteria for study selection using PRISMA

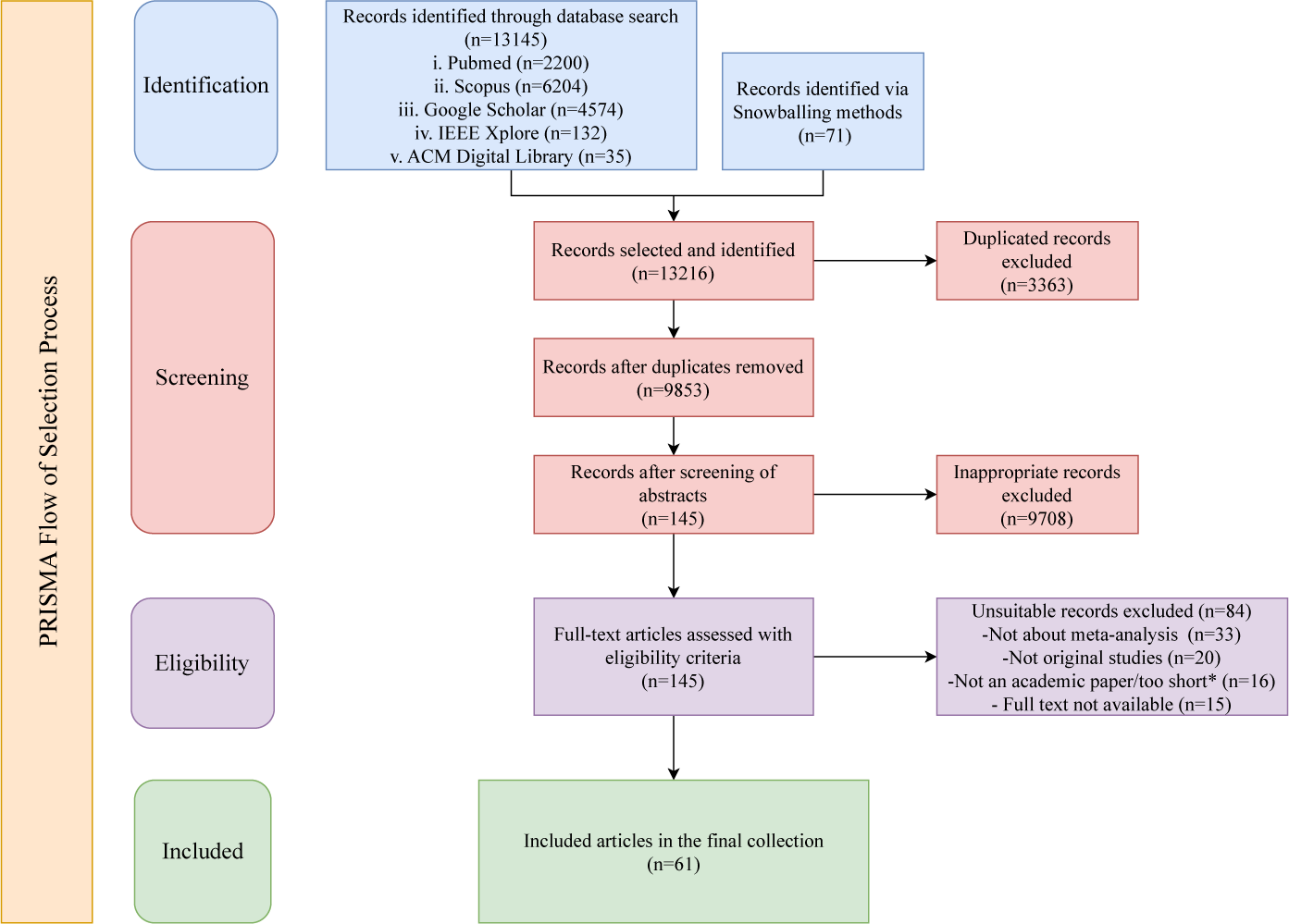

The systematic review process, managed through Zotero 7, began with duplicate removal followed by a two-phase screening. One reviewer (L.L.) conducted the initial screening of titles and abstracts to exclude irrelevant records, while two additional reviewers (A.M. and T.S.) independently checked and confirmed the results. The same procedure was applied for the full-text review and any discrepancies in selection were resolved through consensus discussions among the reviewers. The PRISMA flowchart (shown in Figure 1) details the selection process. Data were analyzed and narratively summarized, with descriptive statistics presented in tables or graphs based on each study’s aim. This process identified 13,145 initial studies (2,200 PubMed, 6,204 Scopus, 4,574 Google Scholar, 132 IEEE Xplore, 35 ACM Digital Library, and 71 snowball), which were refined to 61 studies (see the Supplementary Material) after removing 3,363 duplicates and excluding 9,708 studies through screening. The whole visual illustration of our systematic review (shown in Figure 2) outlines the key steps, addresses four research questions, highlighting key contributions, current challenges, and future trends in AMA.

Figure 1 PRISMA workflow.

Note: “Too short” = records with fewer than four pages, excluded for lacking methodological detail.

Figure 2 Holistic framework for this review.

3.2 Progressive phase structure in TTF

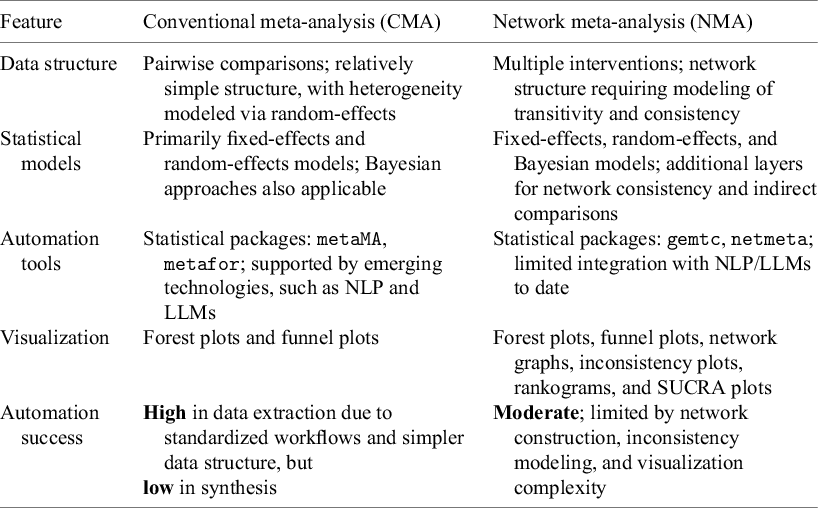

AMA streamlines the traditional resource-intensive process of MA by integrating automation for data extraction, analysis, and synthesis, enhancing efficiency while reducing human error and statistical expertise requirements. MAs can be categorized along multiple dimensions, including network structure, data type, statistical framework, update approach, and purpose. Among these, this review focuses on widely used and methodologically distinct approaches: conventional MA (CMA) for direct pairwise comparisons and network MA (NMA) for integrating both direct and indirect evidence across multiple interventions.

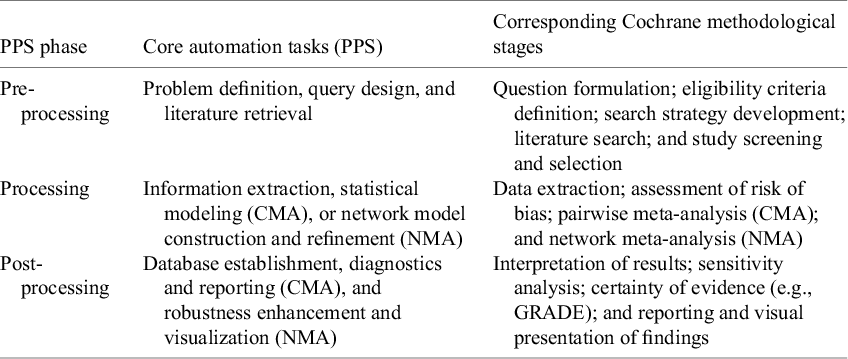

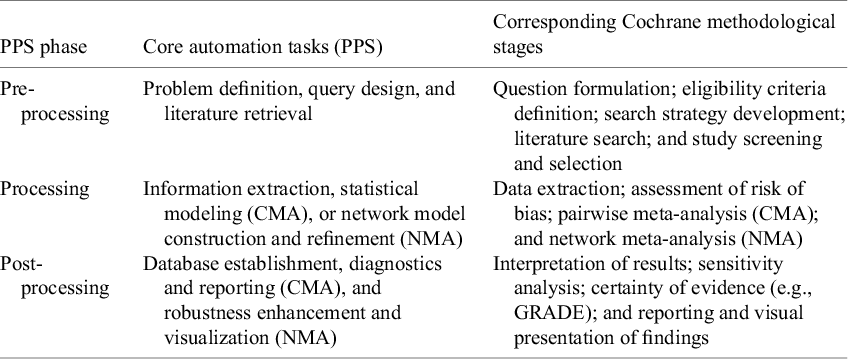

While MA methodologies (e.g., the Cochrane Handbook) provide a comprehensive set of methodological stages, these frameworks were not originally designed with automation in mind. Existing automation tools target isolated stages of the process; however, there remains no overarching framework to systematically organize and align automation efforts across the full MA workflow. To address RQ1 (What are the current landscape and key characteristics of AMA approaches?), we introduce the progressive phase structure (PPS), an automation-oriented framework that complements existing methodologies by structurally organizing automation tasks across the entire process. Figure 3 illustrates the PPS framework, which categorizes automation processes into three distinct phases across both CMA and NMA:

-

• Pre-processing stage: Encompasses problem definition, query design, and literature retrieval. NLP, ML, and LLMs can significantly reduce time spent on these labor-intensive tasks.

-

• Processing stage: Involves information extraction (IE) and statistical modeling in CMA or network model construction and refinement in NMA. Automated tools leveraging NLP, ML, and LLMs help extract required datasets and other relevant information and achieve high efficiency.

-

• Post-processing stage: Focuses on database establishment, diagnostics, and reporting in CMA, and robustness enhancement and visualization in NMA. Different automation tools can enhance reproducibility through standardized reports and dynamic visualizations, thereby improving transparency.

Figure 3 Progressive phase structure with TTF model.

Note: “PreQ”, “ProcQ”, and “PostQ” denote analytical questions from the pre-processing, processing, and post-processing stages, respectively. Assessment ratings (H = High, M = Moderate, L = Low) are defined above.

PPS does not aim to replace existing methodological taxonomies but to provide a complementary, automation-oriented structure. It organizes the workflow into three high-level phases that correspond to established MA tasks outlined in the Cochrane Handbook (see Table 2), ensuring methodological completeness while offering a streamlined and automation-compatible perspective on the review process. To assess automation effectiveness, we also integrate the TTF model with PPS, providing a structured approach to evaluating alignment between specific MA tasks and available automation tools. This approach systematically deconstructs the automation process into granular components and assesses technological fit at each stage, which operationalizes this alignment by defining:

-

• Tasks: Fundamental, well-defined tasks performed at each PPS phase (e.g., problem definition, query design, and literature retrieval). These tasks represent the concrete units of analysis for evaluating technology alignment.

-

• Technology characteristics: Functional capabilities (e.g., IE, document classification, and text generation) enabled by current automation tools, such as NLP models, ML algorithms, and LLMs.

-

• TTF assessment: Structured evaluation questions designed to systematically assess the degree to which available automation tools support the defined tasks, using a three-level qualitative scale (high/moderate/low).

Table 2 Task-level mapping between PPS automation phases and Cochrane methodological stages

The three-level TTF assessment questions were developed through iterative pilot coding and team discussions to enhance conceptual clarity and ensure coverage across all AMA stages. For the actual application of these assessments, one reviewer (L.L.) initially extracted data from each included study (e.g., tool name, application stage, functionality, methodological approach, reported performance, and limitations). Two additional reviewers (A.M. and T.S.) independently checked and confirmed the extracted information. The extracted data were then mapped to the PPS framework. TTF ratings were assigned using the same process: L.L. provided initial judgments based on the predefined scale (H-high, M-moderate, and L-low), and A.M. and T.S. independently reviewed the ratings. Any discrepancies in data extraction or assessment were resolved through structured consensus discussions. By structuring AMA through PPS and rigorously applying the TTF model (all details were fully provided in Figure 3), this framework provides a robust methodological foundation for evaluating automation effectiveness in AMA.

4 Results

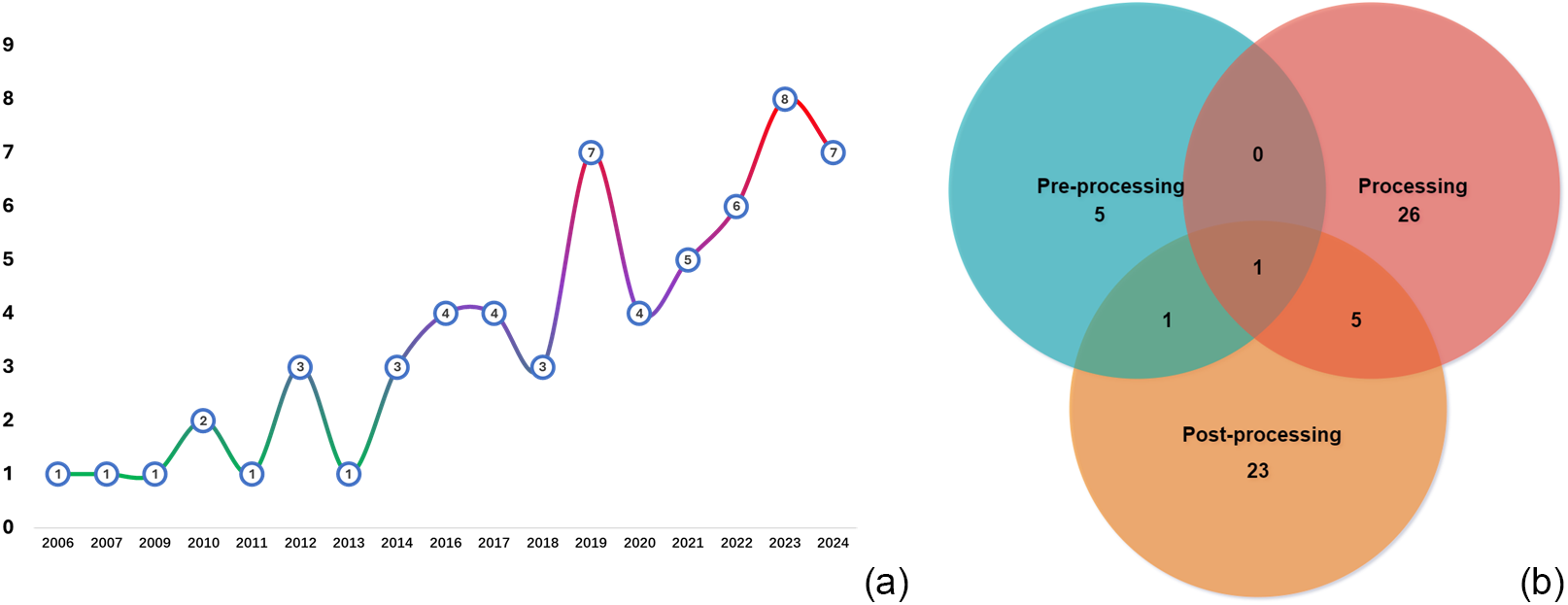

Our review identified AMA publications primarily from journals (72%), conferences (25%), and preprints (3%). Figure 4(a) illustrates the temporal trends showing growth from a single publication in 2006–2009 to seven in 2024. This acceleration, particularly from 2018 onward, coincides with broader AI advancements and increased availability of computational resources. Despite the growth, the relatively low publication volume indicates AMA remains an emerging field with substantial exploration potential. Besides, analysis of PPS implementation revealed that 89% of studies focused on automating a specific MA step, while only 11% addressed multiple stages. Notably, just one study (2%) attempted full integration across all MA stages, highlighting a significant methodological gap. This indicates that while isolated automation tools have advanced considerably, creating seamless multi-stage workflows remains challenging. Figure 4(b) shows that the processing stage dominates AMA research efforts. This concentration likely stems from the technical feasibility and maturity of NLP and ML tools for IE. As IE represents a fundamental prerequisite for all MAs, automation in this area yields substantial efficiency gains. In contrast, the later MA stage involves complex, context-dependent synthesis, which raises further automation challenges, limiting the broader adoption of the system throughout the process.

Figure 4 Temporal patterns in AMA publications (a) and proportional discrepancies across different stages (b).

To address RQ2 (How does our analytical framework illuminate the strengths and limitations of current AMA approaches within each information processing stage?), we provide a comprehensive task breakdown aligned with our analytical framework (refer Figure 3). Automation requirements and success rates vary significantly due to differences in data structure, synthesis models, and computational complexity. Our analysis examines automation strategies and tools employed in both CMA and NMA, identifying distinctive characteristics in each approach. The following sections detail automation processes across PPS stages within the TTF model.

4.1 Automation of data pre-processing

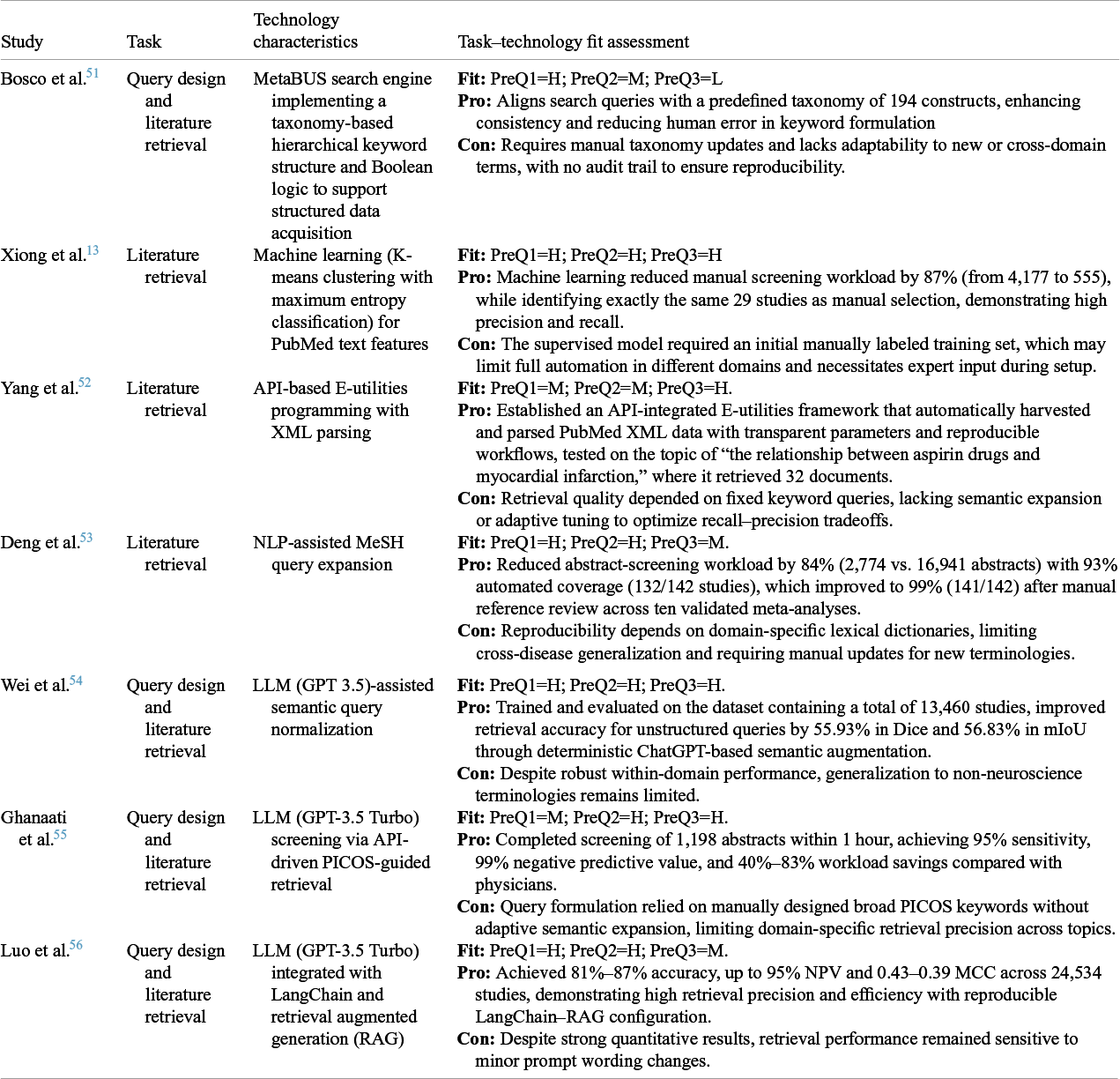

Pre-processing in MA comprises problem definition, query design, and literature retrieval, which are all critical for refining datasets for subsequent analysis. The quality of research questions and query design directly influences the relevance and comprehensiveness of retrieved literature. With increasing data volumes, automation has become essential for managing meta-analytic datasets while minimizing bias, as MA performance fundamentally depends on the retrieved literature. In this study, automation is defined for each stage of the meta-analytic workflow. In pre-processing, it refers to algorithmic or rule-based methods that minimize human involvement in problem formulation, query design, and literature retrieval. Our review shows that AMA studies on pre-processing have been developed and tested only within pairwise (CMA) frameworks. Although the procedures are conceptually identical for CMA and NMA, no studies have explicitly adapted automation to accommodate NMA-specific practical considerations, such as capturing all relevant interventions and comparators so that studies form a connected treatment network. Accordingly, current automation efforts in pre-processing remain limited to the CMA context. Table 3 presents a structured evaluation of studies focused on automating this phase, applying TTF to assess alignment between technologies and specific pre-processing tasks.

Table 3 Task–technology fit assessment for pre-processing in AMA

Note: PreQ = pre-processing question (1: alignment with domain-specific query requirements; 2: balance of comprehensiveness and precision; and 3: reproducibility of automated retrieval and screening).

Traditional MA requires researchers to craft search strategies that balance breadth and specificity, an inherently complex process that is dependent on researcher expertise.Reference Higgins, Thomas and Chandler 12 Automation tools have progressively reshaped this stage. Early systems, such as MetaBUS and MeSH-based expansion frameworks, standardized query formulation within domains, capturing up to 99% of eligible studies while reducing screening workloads by over 80%.Reference Bosco, Uggerslev and Steel 51 , Reference Deng, Yin and Bao 53 ML approaches, exemplified by K-means classification, achieved comparable precision to manual screening while drastically cutting dataset size.Reference Xiong, Liu and Tse 13 LLM-based methods further advanced retrieval efficiency and comprehensiveness, reporting sensitivities up to 95% and workload reductions of 40%–83%.Reference Wei, Zhang and Zhang 54 – Reference Luo, Sastimoglu, Faisal and Deen 56 Despite these gains, reproducibility remains a limiting factor, whereas ML and LLM pipelines, though reproducible within fixed configurations, are sensitive to domain shifts and prompt variation. Overall, automation in pre-processing in CMA has evolved from static keyword expansion to semantically enriched retrieval, improving coverage and efficiency but still lacking in cross-domain generalizability and standardized reproducibility.

4.2 Automation of data processing

Our review highlights the critical role of automation in the data processing phase for both CMA and NMA methodologies. While both approaches aim to enhance meta-analytic efficiency and reliability, they involve distinct automation requirements. CMA prioritizes IE and statistical modeling for synthesizing individual study data, whereas NMA focuses on network model construction and refinement, addressing challenges in inconsistency detection and network connectivity assessment. The following sections provide an in-depth examination of these tasks and their automation potential.

4.2.1 Automated data processing in CMA

Following the pre-processing stage, the next critical task in CMA is IE and statistical modeling. IE techniques transform unstructured text into analyzable, structured data—a fundamental prerequisite for CMA. Key subtasks include named entity recognition (NER) for identifying critical variables and relation extraction (RE) for determining relationships between entities across research articles. Automated IE substantially reduces manual data entry, although performance often varies by domain complexity and terminology. For statistical modeling, automation increasingly relies on algorithmic and workflow-level standardization, enabling reproducible computation of effect sizes and model estimation across meta-analytic datasets. However, model selection must align with specific data types and research objectives: some statistical frameworks offer specialized capabilities for particular data structures (e.g., binary or time-to-event outcomes), while others provide broader applicability across diverse datasets and contexts. Table 4 summarizes studies on automating the data processing phase in CMA using the TTF model, assessing alignment between technologies and tasks requirements while providing insights into their effectiveness and limitations.

Table 4 Task–technology fit assessment for automated data processing in CMA

Note: ProcQ = processing question (1: extraction of complex patterns and contextual relationships; 2: enhancement of structure and interpretability of unstructured data; and 3: reliability of automated standardization and statistical consistency).

Table 5 Task–technology fit assessment for automated data processing in NMA

Note: ProcQ = processing question (1: extraction of complex patterns and contextual relationships; 2: enhancement of structure and interpretability of unstructured data; and 3: reliability of automated standardization and statistical consistency).

Information extraction: Across reviewed studies, automation in IE has evolved from rule-based NER toward deep learning and LLM-driven RE. Early NLP pipelines, such as EXACT,Reference Pradhan, Hoaglin, Cornell, Liu, Wang and Yu 61 achieved 100% data accuracy and a 60% reduction in extraction time, demonstrating high data precision and complete structural mapping. However, reliance on domain-specific vocabularies constrained generalization, limiting interpretability beyond predefined contexts. Hybrid and deep learning methods, such as BERT-based PICO extraction, improved both structural accuracy and semantic clarity, though they still required carefully curated training data to ensure consistent interpretation across studies.Reference Mutinda, Yada, Wakamiya and Aramaki 17 , Reference Mutinda, Liew, Yada, Wakamiya and Aramaki 65 More recent LLM-based frameworks, such as MetaMateReference Wang and Luo 70 and GPT-3.5-powered systems,Reference Kartchner, Ramalingam, Al-Hussaini, Kronick, Mitchell, Demner-fushman, Ananiadou and Cohen 67 , Reference Shah-Mohammadi and Large 68 further enhanced contextual linking and conceptual coherence. However, they show only moderate reliability due to sensitivity to prompts and inconsistent XML parsing. Overall, IE automation has advanced in structural precision and interpretability, but continues to face challenges in achieving stable, cross-domain reproducibility.

Statistical modeling: Automation in statistical modeling primarily enhances computational reproducibility and standardization. Early probabilistic frameworksReference Choi, Shen, Chinnaiyan and Ghosh 71 , Reference Marot, Foulley, Mayer and Jaffrézic 72 automated effect-size estimation and variance moderation, achieving high precision and structural completeness and strong interpretability in small-sample analyses. However, assumptions of study homogeneity and computational intensity limited robustness in large-scale applications. R-based automation tools like metafor,Reference Viechtbauer 73 METAL,Reference Willer, Li and Abecasis 74 and MetaOmics Reference Wang, Kang and Shen 75 established computational pipelines, incorporating parameter and varied heterogeneity estimators, resulting in high reproducibility. These systems ensured reliable model fitting across datasets but still required domain expertise to ensure valid inferences. Subsequent tools, including metamisc,Reference Debray, Damen and Riley 77 AMANIDA,Reference Llambrich, Correig, Gumà, Brezmes and Cumeras 80 and NeuroQuery,Reference Dockès, Poldrack and Primet 78 extended automation to predictive and cross-domain contexts. These frameworks integrated heterogeneous data types and automated statistical evaluations, achieving high data precision and semantic interpretability while maintaining reproducibility through transparent algorithms and standardized output. Overall, statistical modeling automation now provides stable and fully reproducible computational workflows, supported by R-based and algorithmic frameworks. Nonetheless, model selection, sensitivity analysis, and interpretation of complex heterogeneous data remain reliant on expert judgment.

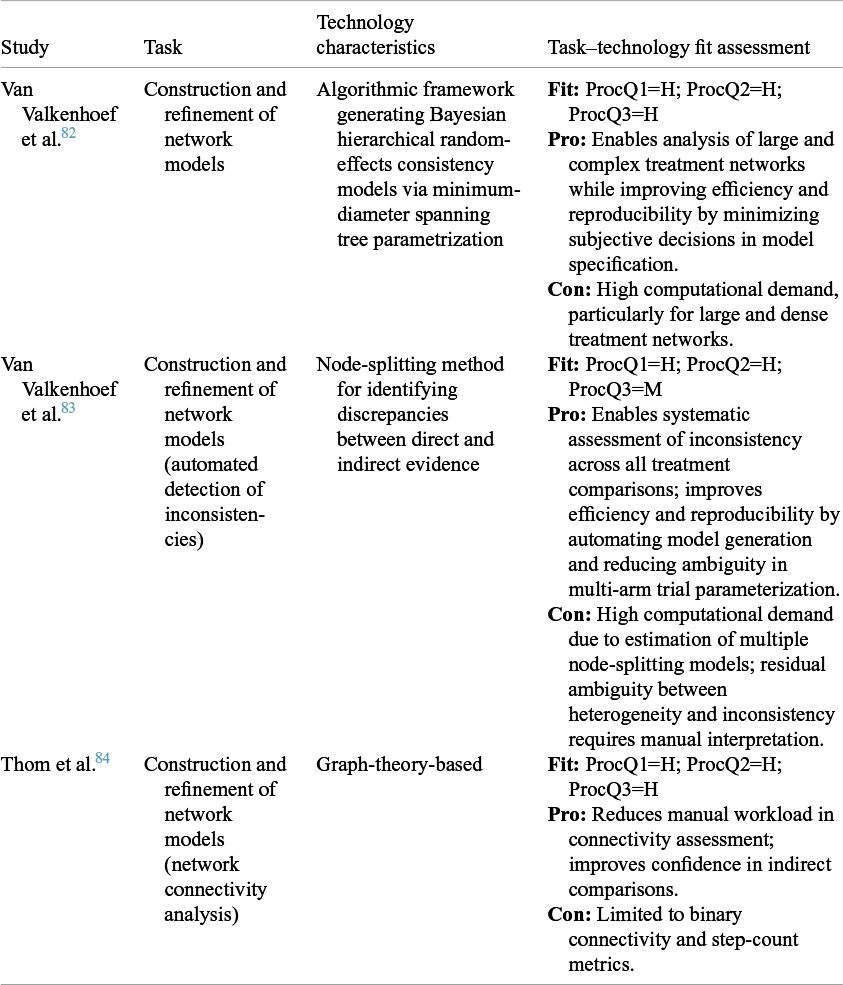

4.2.2 Automated data processing in NMA

In NMA, constructing and refining network models represents a critical challenge distinct from CMA. While CMA primarily extracts information and develops statistical models, NMA must integrate both direct and indirect evidence across multiple interventions through complex network structures. Automation in this domain enhances model consistency, computational efficiency, and reduces manual intervention. Table 5 provides an overview of the included studies in NMA through the TTF model. Van Valkenhoef et al.Reference Van Valkenhoef, Lu, De Brock, Hillege, Ades and Welton 82 pioneered this progress by developing a Bayesian consistency model generation framework that transformed what was previously a manual process requiring subjective parameter decisions. Extending this work, they introduced an automated node-splitting procedure for systematic inconsistency detection, further strengthening analytical transparency and comparability across treatment networks, though reproducibility was moderately limited by residual ambiguity between heterogeneity and inconsistency.Reference Van Valkenhoef, Dias, Ades and Welton 83 More recently, Thom et al.Reference Thom, White, Welton and Lu 84 applied graph-theoretical metrics to automate network connectivity analysis, reducing manual workload and reinforcing confidence in indirect comparisons across complex networks. Collectively, these advances reducing researcher subjectivity and enabling reproducible, scalable evaluation of increasingly intricate treatment networks.

4.3 Automation of data post-processing

Having examined automation in data pre-processing and processing for both CMA and NMA, we now focus on data post-processing, a critical phase involving result refinement and synthesis to ensure reporting accuracy and clarity. This increasingly important area of AMA research enhances analytical precision and advances evidence synthesis. The following sections will provide a detailed characteristics of CMA and NMA post-processing automation.

4.3.1 Automated data post-processing in CMA

Our examination categorizes CMA automated post-processing into three domains: (1) database establishment for structured data organization; (2) diagnostics and extensions for bias or heterogeneity assessment; and (3) reporting synthesis and result interpretation for standardized findings presentation. In this context, automation refers to the use of computational systems (e.g., AI-assisted reporting frameworks and visualization tools) to perform data consolidation, interpretive synthesis, and result presentation with minimal human intervention. Table 6 presents the TTF alignment for CMA post-processing studies.

Table 6 Task–technology fit assessment for automated data post-processing in CMA

Note: PostQ = post-processing question (1: accuracy and completeness of database construction and bias correction; 2: reliability and transparency of AI-assisted interpretation; and 3: clarity and robustness of visualization for decision-making).

Database establishment: Automated database establishment in CMA has evolved from structured text-mining to dynamic web-integrated systems that enhance data accessibility and error correction. Early tools, such as Neurosynth,Reference Yarkoni, Poldrack, Nichols, Van Essen and Wager 85 achieved strong domain accuracy by constructing a MySQL-based database of 3,489 studies with 84% sensitivity and 97% specificity, but lexical coding inconsistencies limited interpretive precision and reproducibility. CancerMAReference Feichtinger, McFarlane and Larcombe 86 and CancerESTReference Feichtinger, McFarlane and Larcombe 87 integrating up to 80 curated datasets in oncology from multiple experiments and standardizing normalization pipelines, improving structural reliability but remaining constrained to specific platforms and outdated repositories. Subsequent frameworks, such as ShinyMDE,Reference Shashirekha and Wani 88 enhanced accessibility through R-based integration of GEO studies, while RetroBioCatReference Finnigan, Lubberink and Hepworth 96 further advanced reproducibility via real-time data updating and open-access deployment. Across these systems, automation demonstrated strong error control and data standardization but still required domain-specific validation and frequent manual curation to maintain interpretive consistency and update coverage.

Diagnostics and extensions: Automation in diagnostics and extensions has significantly improved bias detection, heterogeneity assessment, and interpretive transparency in CMA. Craig et al.Reference Craig, Bae and Taswell 89 employed web crawlers and NLP-based inference engines to extract effect sizes and detect cross-study inconsistencies, achieving high domain precision and interpretability, though reproducibility was limited by system complexity and lack of visual diagnostics. Cheng et al.Reference Cheng, Katz-Rogozhnikov, Varshney and Baldini 20 introduced causal inference diagnostics for bias detection in RCTs, enabling adjustment for hidden confounders but requiring manual causal graph interpretation. Recent frameworks demonstrate marked advances in reproducibility: metaGWASmanagerReference Rodriguez-Hernandez, Gorski, Tellez-Plaza, Schlosser and Wuttke 21 standardized over 130 genome-wide association study (GWAS) workflows, achieving high stability across analyses, while BiNDiscoverReference Bremer, Wohlgemuth and Fiehn 97 and MetaExplorerReference Kale, Lee, Goan, Tipton and Hullman 98 further integrated bias quantification and visualization for metabolomics data, reaching high consistency across 350 datasets. Overall, diagnostic automation now exhibits uniformly high domain precision and interpretive clarity, with reproducibility advancing from low to high through modular, transparent pipeline architectures.

Result synthesis and interpretation: Automated result synthesis and interpretation have progressed from conventional random-effects modeling to fully integrated AI- and LLM-driven systems. Michelson et al.Reference Michelson 16 and Yang et al.Reference Yang, Tang, Dongye and Chen 52 laid the groundwork with random-effects and R-Meta-based synthesis, achieving moderate to high interpretability but limited reproducibility due to scalability constraints. Subsequent frameworks, such as MetaCyto,Reference Hu, Jujjavarapu and Hughey 90 MetaMSD,Reference Ryu and Wendt 91 and RICOPILI,Reference Lam, Awasthi and Watson 92 improved integration accuracy and automation depth, reaching high reproducibility and interpretive precision across large datasets. In parallel, web-based platforms, such as CogTaleReference Sabates, Belleville and Castellani 94 and PsychOpen,Reference Burgard, Bosnjak and Studtrucker 95 introduced semi-automated reporting pipelines that produced standardized, dynamically updated outputs. Recent advancements, including Text2BrainReference Ngo, Nguyen, Chen and Sabuncu 93 Chat2Brain,Reference Wei, Zhang and Zhang 54 have integrated LLMs and visualization modules to enhance semantic synthesis. Overall, CMA post-processing remains dominated by conventional synthesis pipelines. LLM-based synthesis is still in its early exploratory stage, offering conceptual promise but limited practical adoption so far.

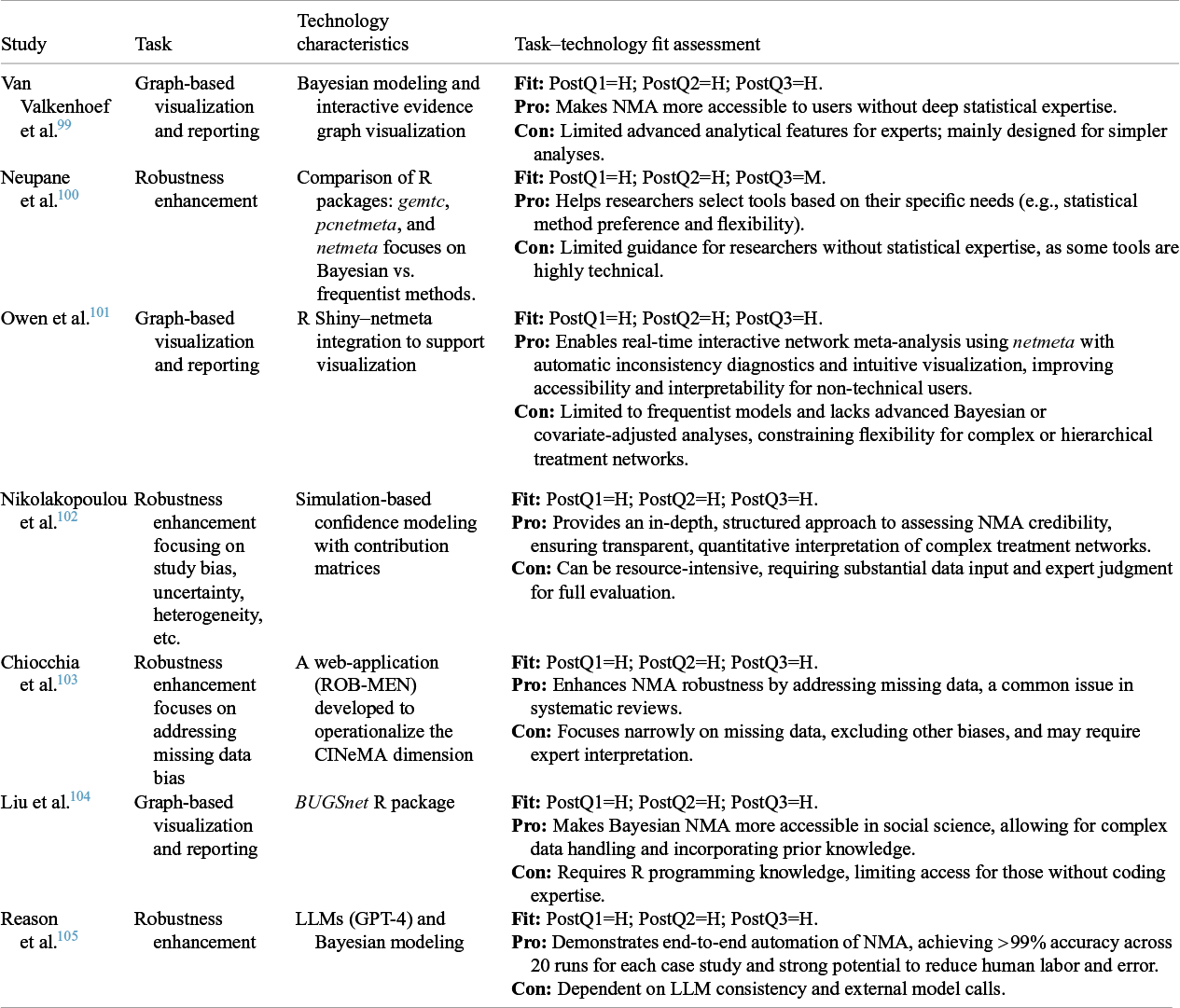

4.3.2 Automated data post-processing in NMA

In contrast to CMA, automated post-processing in NMA focuses on two primary areas: (1) robustness enhancement to ensure network model validity and stability and (2) graph-based visualization and reporting to facilitate complex treatment network interpretation. Table 7 presents studies relevant to NMA post-processing.

Table 7 Task–technology fit assessment for automated data post-processing in NMA

PostQ = post-processing question (1: accuracy and completeness of database construction and bias correction; 2: reliability and transparency of AI-assisted interpretation; 3: clarity and robustness of visualization for decision-making).

Robustness enhancement: Automation for robustness enhancement in NMA has evolved from traditional statistical comparisons toward integrated credibility frameworks. Neupane et al.Reference Neupane, Richer, Bonner, Kibret and Beyene 100 compared three major R packages—gemtc, pcnetmeta, and netmeta—evaluating their efficiency and flexibility across Bayesian and frequentist models. This comparison achieved high domain fit by clarifying methodological options but required statistical expertise for practical use. Nikolakopoulou et al.Reference Nikolakopoulou, Higgins and Papakonstantinou 102 developed CINeMA, a simulation-based framework providing quantitative credibility assessments for complex treatment networks, addressing uncertainty, bias, and heterogeneity. ROB-MENReference Chiocchia, Holloway and Salanti 103 automated the evaluation of missing data bias, further strengthening analysis reliability. Most recently, Reaon et al.Reference Reason, Benbow, Langham, Gimblett, Klijn and Malcolm 105 explored the integration of LLMs (GPT-4) with Bayesian modeling to achieve near end-to-end automation. However, as in CMA, LLM use in NMA remains preliminary, showing clear potential but lacking solid support at this point.

Graph-based visualization and reporting: Graph-based visualization is essential for interpreting complex treatment networks in NMA. Van Valkenhoef et al.Reference Van Valkenhoef, Tervonen, Zwinkels, De Brock and Hillege 99 pioneered this direction with ADDIS, a Bayesian graph-based platform that visualized evidence networks and treatment effects through standardized analysis and transparent output. Subsequently, MetaInsightReference Owen, Bradbury, Xin, Cooper and Sutton 101 combined R netmeta with a Shiny interface, enabling real-time network visualization, automatic inconsistency diagnostics, and simplified workflows for non-technical users, though limited to frequentist models. Extending accessibility to new fields, Liu et al.Reference Liu, Béliveau, Wei and Chen 104 developed BUGSnet, a Bayesian R package designed for psychology and social sciences. Nevertheless, current visualization and reporting systems remain dominated by rule-based and R-based architectures, AI- or LLM-assisted visualization has not yet been applied in NMA practice representing a promising direction for future development.

4.4 Patterns of AMA across domains

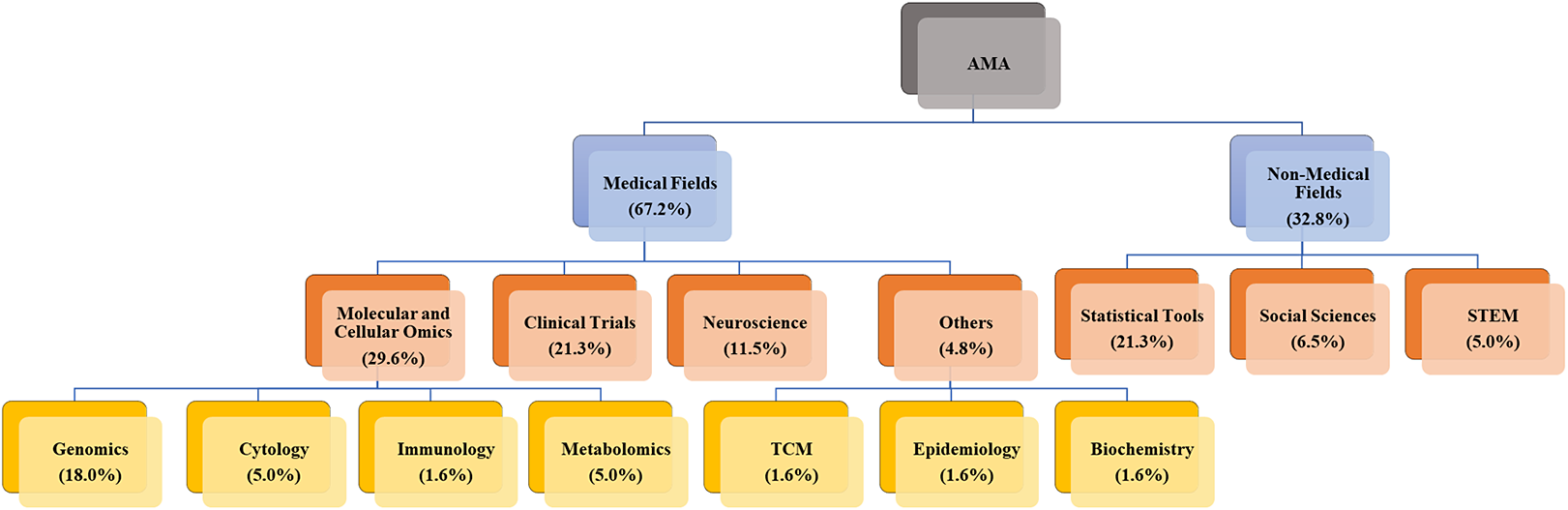

The PPS with TTF model provides a comprehensive framework for AMA by automating each process step. To answer RQ3 (What are the distinct patterns in AMA implementation, effectiveness, and challenges observed across medical and non-medical domains?), our analysis revealed significant domain-specific variations.

A primary distinction lies in the predominant data characteristics and their implications for automation adoption. Medical domains more frequently utilize standardized, structured data from clinical trials, healthcare records, and standardized literature (e.g., CONSORT-compliant reports and structured abstracts). This prevalence of standardization creates a stronger TTF for automated tools, such as NLP, ML, and LLMs, which can efficiently process consistent terminology with minimal human intervention. While medical research certainly includes unstructured elements (such as clinical notes and narrative case reports), the presence of substantial standardized components has enabled earlier and more widespread adoption of AMA. Conversely, non-medical fields (social sciences, management, education, and STEM) predominantly present heterogeneous, less structured data with varied reporting styles and terminologies. Although pockets of standardization exist (e.g., large-scale survey data in the social sciences or structured experimental datasets in STEM), the relative lack of universal standardization frameworks creates greater challenges for current automated tools. This helps explain the lower adoption rates observed in our review (Figure 5). Methodological traditions further differentiate these domains. In the medical domain, established protocols, statistical methods, and data collection guidelines support automation through more predictable, uniform data formats. The greater methodological diversity in non-medical fields, while valuable for exploratory research, complicates the application of automated tools.

Figure 5 Interdisciplinary applications of AMA across various domains.

Figure 6 Cross-domain mapping of AMA applications, data types, and methodological approaches.

Our systematic review provides empirical evidence for these domain-specific distinctions. Figure 5 illustrates the disparity: medical applications account for 67.2% of reviewed studies (

![]() $n=41$

), compared to 32.8% in non-medical domains (

$n=41$

), compared to 32.8% in non-medical domains (

![]() $n=20$

), with clinical trials alone comprising 21.3% of all AMA implementations. This marked imbalance highlights differences in the maturity of TTF across domains. To complement this proportional view, Figure 6 offers a quantitative mapping of cross-domain linkages among domain applications, data types, and computational methods, with line thickness reflecting application frequency. The visualization reveals a clear pattern: medical AMA primarily draws on structured or semi-structured data sources (e.g., public databases and abstracts) that align closely with NLP- and ML-based automation pipelines. In contrast, non-medical AMA remains centered on statistical and methodological tool development, with social science and STEM studies still at early stages of practical adoption. Taken together, these findings reveal a maturity gradient across domains: medical fields exhibit dense, stable connections between standardized data and well-established computational methods, whereas non-medical domains display more fragmented, exploratory linkages that are still evolving toward systematic automation. Notably, the emergence of LLMs marks a new trend across domains, but their practical applications remain limited in both medical and non-medical fields. Current studies are largely exploratory, focusing on assessing feasibility rather than achieving full automation. Detailed analysis in the following sections illustrates how these differences translate into distinct task–technology alignment dynamics, tool specialization trajectories, and varying levels of automation maturity across medical and non-medical subfields. Importantly, our dual-perspective analysis highlights reciprocal learning opportunities that bridge traditional disciplinary divides. These opportunities for cross-disciplinary collaboration emphasize that advancing AMA requires not only innovation within each domain but also purposeful knowledge exchange across the medical-non-medical divide.

$n=20$

), with clinical trials alone comprising 21.3% of all AMA implementations. This marked imbalance highlights differences in the maturity of TTF across domains. To complement this proportional view, Figure 6 offers a quantitative mapping of cross-domain linkages among domain applications, data types, and computational methods, with line thickness reflecting application frequency. The visualization reveals a clear pattern: medical AMA primarily draws on structured or semi-structured data sources (e.g., public databases and abstracts) that align closely with NLP- and ML-based automation pipelines. In contrast, non-medical AMA remains centered on statistical and methodological tool development, with social science and STEM studies still at early stages of practical adoption. Taken together, these findings reveal a maturity gradient across domains: medical fields exhibit dense, stable connections between standardized data and well-established computational methods, whereas non-medical domains display more fragmented, exploratory linkages that are still evolving toward systematic automation. Notably, the emergence of LLMs marks a new trend across domains, but their practical applications remain limited in both medical and non-medical fields. Current studies are largely exploratory, focusing on assessing feasibility rather than achieving full automation. Detailed analysis in the following sections illustrates how these differences translate into distinct task–technology alignment dynamics, tool specialization trajectories, and varying levels of automation maturity across medical and non-medical subfields. Importantly, our dual-perspective analysis highlights reciprocal learning opportunities that bridge traditional disciplinary divides. These opportunities for cross-disciplinary collaboration emphasize that advancing AMA requires not only innovation within each domain but also purposeful knowledge exchange across the medical-non-medical divide.

4.4.1 Medical field

AMA in the medical field is rapidly evolving across clinical trials, molecular and cellular omics, neuroscience, and specialized domains.

Clinical trials: AMA in clinical trials has progressed from abstract-based data extraction to complex full-text analysis, propelled by NLP, ML, LLMs, and other enhanced computational tools. This development has enabled automation across critical tasks, including literature selection, data extraction, publication bias evaluation, and results synthesis. Early efforts established foundational synthesis capabilities,Reference Michelson 16 while subsequent research improved literature selectionReference Xiong, Liu and Tse 13 and significantly enhanced data extraction efficiency.Reference Mutinda, Yada, Wakamiya and Aramaki 17 , Reference Yang, Tang, Dongye and Chen 52 , Reference Pradhan, Hoaglin, Cornell, Liu, Wang and Yu 61 , Reference Mutinda, Liew, Yada, Wakamiya and Aramaki 65 , Reference Kartchner, Ramalingam, Al-Hussaini, Kronick, Mitchell, Demner-fushman, Ananiadou and Cohen 67 – Reference Yun, Pogrebitskiy, Marshall, Wallace, Deshpande, Fiterau, Joshi, Lipton, Ranganath and Urteaga 69 Progress also extends to mitigating publication bias.Reference Cheng, Katz-Rogozhnikov, Varshney and Baldini 20 However, achieving fully AMA remains elusive due to persistent challenges, including data inconsistency, incomplete datasets, and limitations in processing complex full-text content. LLMs also require refinement to interpret intricate analytical demands effectively. Domain-specific applications illustrate both potential and constraints: ChatGPT has been adapted for screening radiology abstracts,Reference Issaiy, Ghanaati and Kolahi 55 and general LLMs have improved NMA for binary and time-to-event outcomes.Reference Reason, Benbow, Langham, Gimblett, Klijn and Malcolm 105 This trajectory highlights AMA’s promise while underscoring the need to address technical barriers for broader applicability. This trajectory illustrates that in structured and protocol-driven clinical environments, automation advances in depth and complexity, yet remains bounded by the limits of text understanding and data completeness.

Molecular and cellular omics: This subdomain exemplifies the structured-data and integration-oriented pattern of AMA, where automation can also build on large-scale, standardized repositories and statistical synthesis frameworks. Unlike literature-based clinical trials, omics AMA leverages structured datasets from public repositories like Genevestigator,Reference Zimmermann, Hirsch-Hoffmann, Hennig and Gruissem 106 GEO, and ArrayExpress,Reference Parkinson 107 emphasizing statistical analysis and integration. Key tasks include data processing, multi-omics integration, and differential expression analysis, a range of specialized tools supports these efforts: RankProd,Reference Hong, Breitling, McEntee, Wittner, Nemhauser and Chory 108 alongside frameworks by Boyko et al.Reference Boyko, Kaidina and Kim 57 and Devyatkin et al.,Reference Devyatkin, Molodchenkov and Lukin 60 facilitates gene expression dataset processing; METALReference Willer, Li and Abecasis 74 enables GWAS MA; ShinyMDEReference Shashirekha and Wani 88 aids in detecting differentially expressed genes; MetaGWASManagerReference Rodriguez-Hernandez, Gorski, Tellez-Plaza, Schlosser and Wuttke 21 handles large-scale GWAS data; MetaCytoReference Hu, Jujjavarapu and Hughey 90 analyzes high-dimensional cytometry data; and AmanidaReference Llambrich, Correig, Gumà, Brezmes and Cumeras 80 detects study discrepancies. These tools have enhanced data processing and integration, with MetaCyto notably improving efficiency in high-dimensional analysis,Reference Hu, Jujjavarapu and Hughey 90 yet challenges like dataset heterogeneity, platform variability, and incomplete data persist. Domain-specific adaptations address some of these issues, such as Amanida’s focus on metabolomics data gapsReference Llambrich, Correig, Gumà, Brezmes and Cumeras 80 and MetaGWASManager’s automation of GWAS analysis,Reference Rodriguez-Hernandez, Gorski, Tellez-Plaza, Schlosser and Wuttke 21 but broader application remains limited by these constraints. Overall, the trajectory in molecular and cellular omics shows that AMA is still constrained by inter-platform heterogeneity.

Neuroscience: The coexistence of quantitative brain-imaging outputs and narrative research reports illustrates the challenge of aligning heterogeneous data modalities within a single automation framework. Neuroscience AMA synthesizes brain-related data using NLP, ML, LLMs, and predictive modeling to identify patterns in cognitive and neural states. This approach targets tasks, such as brain activation mapping, cognitive intervention analysis, and event-related potential (ERP) analysis. Progress in brain mapping tools has evolved from NeuroSynthReference Yarkoni, Poldrack, Nichols, Van Essen and Wager 85 to NeuroQuery,Reference Dockès, Poldrack and Primet 78 Text2Brain,Reference Ngo, Nguyen, Chen and Sabuncu 93 and Chat2Brain,Reference Wei, Zhang and Zhang 54 while predictive modeling has advanced through NPDS 0.9Reference Craig, Bae and Taswell 89 and cognitive intervention repository via CogTale.Reference Sabates, Belleville and Castellani 94 Despite these developments, challenges persist, including limited data availability, variability in experimental design, and difficulties in processing large volumes of unstructured text. Domain-specific adaptations, such as probabilistic ERPs literature analysisReference Donoghue and Voytek 64 and neural networks linking text queries to brain activation in Chat2Brain,Reference Wei, Zhang and Zhang 54 demonstrate potential but highlight the need to address these constraints for broader application. Therefore, this mixed-structure in AMA demonstrates that the coexistence of structured and unstructured data both drives methodological innovation and constrains full automation.

Specialized domains: AMA applications extend to specialized domains, including traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), epidemiology, and biochemistry, demonstrating adaptability across diverse research contexts. In these fields, AMA focuses on data processing and evidence synthesis, employing tools, such as logistic regression, ML, and NLP. Notable successes include automated logistic regression for epidemiological individual participant data (IPD) MAs, which reduces processing time and errors.Reference Lorenz, Abdi and Scheckenbach 59 However, the specialized nature of these systems restricts their generalizability. Domain-specific adaptations, such as TCM literature synthesis for splenogastric diseasesReference Zhang, Wang and Yao 66 and the RetroBioCat Database for biocatalysis data exploration,Reference Finnigan, Lubberink and Hepworth 96 reveal a pattern of constrained generalization. Automation performs exceptionally well in targeted, well-defined contexts but faces challenges when extending beyond these specialized frameworks.

4.4.2 Non-medical field

AMA applications remain limited outside medicine, with only nascent adoption in three key domains: statistical tools, social sciences, and STEM. This scarcity reflects both challenges and opportunities for expanding AMA beyond medical contexts.

Statistical tools: This category illustrates a cross-domain methodological pattern of AMA, where automation focuses on enhancing statistical modeling, consistency checking, and computational reproducibility. Although inherently applicable across both medical and non-medical contexts, these tools are typically introduced in the literature as methodological contributions rather than domain-specific applications. For this reason, we present them here at the beginning of the non-medical section. These tools encompass Bayesian random-effects models, graph theory, web-based platforms, and decision rules. Statistical packages, such as metafor,Reference Viechtbauer 73 Meta-Essentials,Reference Suurmond, Van Rhee and Hak 76 and metamisc,Reference Debray, Damen and Riley 77 have improved analysis accessibility, while NMA tools, including gemtc, pcnetmeta, and netmeta,Reference Neupane, Richer, Bonner, Kibret and Beyene 100 support complex modeling. Semi-automated systems ADDISReference Van Valkenhoef, Tervonen, Zwinkels, De Brock and Hillege 99 and analytical frameworks for consistency checks and bias assessment such as Bayesian random-effects models,Reference Van Valkenhoef, Lu, De Brock, Hillege, Ades and Welton 82 – Reference Thom, White, Welton and Lu 84 CINeMA,Reference Nikolakopoulou, Higgins and Papakonstantinou 102 and ROB-MENReference Chiocchia, Holloway and Salanti 103 further refine precision. Web platforms MetaInsightReference Owen, Bradbury, Xin, Cooper and Sutton 101 enhance usability for researchers without extensive statistical expertise. Nonetheless, challenges remain, including limited multi-modal data processing and the growing complexity of modern meta-analytical frameworks. Domain-specific adaptations, such as ADDIS, CINeMA, ROB-MEN, and MetaInsight, address specialized NMA needs but reflect the persistent tension between tool sophistication and broad applicability. Therefore, these developments show a methodological pattern emphasizing statistical rigor and reproducibility.

Social science: Social sciences have begun adopting AMA tools for synthesizing diverse data types across disciplines, such as human resource management, psychology, and education, focusing on tasks like data synthesis and predictive modeling. Tools, such as Bayesian methods and LLMs, underpin these efforts. Notable advances include MetaBUS, which streamlines MA across extensive literature volumesReference Bosco, Uggerslev and Steel 51 ; Bayesian NMA opens new possibilities for quantitative analysisReference Liu, Béliveau, Wei and Chen 104 ; and MetaMate leverages few-shot prompting for data extraction in education.Reference Wang and Luo 70 However, the diversity of data types, particularly qualitative data and complex models, poses significant challenges to automation, highlight the ongoing difficulty of achieving broad applicability across heterogeneous datasets. AMA in the social sciences remains in an exploratory stage, these early attempts mark an important foundation for future integration of LLM-based synthesis, suggesting a gradual but steady shift toward more systematic automation in social research.

STEM: AMA in STEM shows progress in literature retrieval and data extraction, leveraging ML-based tools and deep transfer learning. Tools like MetaSeer.STEMReference Neppalli, Caragea, Mayes, Nimon and Oswald 58 streamlines data extraction from research articles, enhancing literature analysis efficiency, while deep transfer learning systems improve retrieval processes.Reference Anisienia, Mueller, Kupfer, Staake and Bui 62 AMA adoption in STEM remains in its early stages, with automation primarily targeting specific tasks like information retrieval rather than comprehensive evidence synthesis. The lack of consistent data standards and the wide-ranging diversity of STEM research hinder scalability. However, the presence of structured experimental data makes STEM a promising area for future advancements as methodological and integration frameworks evolve.

5 Challenges and future potential for AMA

Despite increasing adoption of AMA techniques, significant challenges remain that must be addressed to realize its full potential for evidence synthesis. To answer RQ4 (What are the critical gaps and future directions for AMA development, and what obstacles need to be addressed to realize its full potential for evidence synthesis?), this section examines key barriers and future directions to enhance AMA’s credibility and utility. These challenges span multiple dimensions: enhancing analytical capabilities while mitigating automation biases; maintaining methodological rigor and transparency; adapting to evolving research technology developments; gaining broader acceptance among stakeholders; and ensuring reliability of synthesized evidence. Prior to presenting our proposed roadmap for AMA development, we assigned values to the “Difficulty” and “Priority” based on a structured methodological framework, grounded in a qualitative assessment of technical, methodological, organizational, ethical, and data-related factors, as well as their anticipated impact on AMA’s development. “Difficulty” reflects the complexity of implementation, considering factors, such as technical barriers (e.g., algorithm complexity and data availability), methodological challenges (e.g., validation rigor), organizational constraints (e.g., interdisciplinary collaboration), and ethical considerations (e.g., transparency). Ratings range from “Low” to “High,” with “Medium” indicating moderate challenges requiring moderate effort or expertise. “Priority” evaluates the urgency and impact of each research direction, integrating immediate practical needs (e.g., addressing current gaps), high-impact potential (e.g., improving validity or scalability), and long-term benefits (e.g., credibility and broad applicability). Ratings are categorized as “Immediate,” “Medium,” or “Long-term,” often combined with qualitative descriptors (e.g., “High Impact and” “Trust”) to reflect multifaceted outcomes. This approach ensures a balanced, evidence-based assessment, and Table 8 presents a prioritized roadmap for AMA development according to this assessment framework. This analysis aims to reveal that advancing AMA requires not only technical innovation, but also methodological refinement and strategic implementation approaches to improve its credibility and utility in diverse research contexts.

Table 8 Future research directions for AMA

5.1 Advancing analytical depth and balancing efficiency in AMA

A critical and persistent limitation in AMA remains the automation of advanced analytical methodologies, including sensitivity analyses, heterogeneity assessments, publication bias evaluations, and stratified subgroup analyses. While preliminary data processing has advanced significantly, sophisticated analytical automation remains underexplored, compromising the reproducibility and scientific validity of AMA findings. Future research should prioritize three critical areas: (1) Algorithm advancement. Developing frameworks that execute complex analytical functions with minimal human intervention while maintaining methodological rigor, including automated sensitivity analysis and bias detection tools. (2) Methodological balance. Creating frameworks that enhance efficiency without compromising analytical depth and integrity, with strategic human oversight at critical analytical stages. (3) Multi-modal data integration. Incorporating heterogeneous data types (numerical data, medical images, tables, and raw data) through adaptable extraction techniques for comprehensive, statistically sound evidence synthesis. These advancements would elevate AMA beyond basic automation to deliver both sophisticated analytical capabilities and enhanced efficiency, strengthening its credibility in high-impact research domains.

5.2 LLMs with fine-tuning and complex reasoning in AMA

LLMs, including those with advanced “thinking” capabilities capable of complex reasoning, offer transformative potential for AMA by efficiently processing unstructured text and extracting critical variables (effect sizes and confidence intervals) from research articles. These “thinking models” in LLMs extend beyond basic data extraction, enabling genuine knowledge synthesis and methodological reasoning, potentially revolutionizing evidence synthesis by integrating statistical and semantic understanding. They function as methodological thought partners, assessing heterogeneity between studies, and adapting analytical strategies to the specific characteristics of included studies, thereby enhancing AMA’s precision, scalability, and adaptability across diverse research contents. However, several challenges hinder their full-scale deployment of LLMs in AMA. These include hallucinations that fabricate results, which is unacceptable in high-stakes applications like healthcare; propagation of implicit biases from training corpora into synthesized outputs; and limitations with extensive context windows when processing journal articles, dissertations, and complex figures/tables.Reference Liu, Lin and Hewitt 109 To maximize this potential opportunity, future research should prioritize developing specialized “thinking LLMs” for analyzing long-form academic content with multi-modal capabilities; enhancing transparency through explainable AI (XAI) techniques to facilitate expert validation of automated extractions; and designing benchmarks and protocols to ensure the accuracy, reliability, and reproducibility of LLM-generated results. These advancements will significantly enhance the reliability and interpretability of LLM-assisted AMA workflows, potentially reshaping the foundations of evidence synthesis methodology and positioning “thinking LLMs” as a cornerstone of future AMA innovation.

5.3 Living AMA

Current AMA implementations primarily automate discrete stages of MA but lack mechanisms for continuous, real-time evidence updates. This limitation is particularly evident in Cochrane MAs, which require periodic updates to maintain clinical relevance. A “living AMA” addresses this gap by envisioning a system that can automatically and continuously scan databases for new studies, extract relevant data, and integrate fresh evidence into existing analyses. Realizing this vision should focus on three key aspects. First, designing robust AI-driven mechanisms to identify and validate new studies as they emerge. Second, developing algorithms to make a version control and reconcile conflicting data across studies while preserving analytical transparency. Third, creating efficient alert mechanisms that update researchers without overwhelming them with excessive information. Living AMA approaches have already emerged in related domains, such as “living literature review,”Reference Wijkstra, Lek, Kuhn, Welbers and Steijaert 110 COVID-19 living MAs,Reference Boutron, Chaimani and Devane 111 MetaCOVID project,Reference Evrenoglou, Boutron, Seitidis, Ghosn and Chaimani 112 and SOLES system.Reference Hair, Wilson, Wong, Tsang, Macleod and Bannach-Brown 113 Building on these foundations, future work must refine the methodological framework for Living AMA to ensure delivery of up-to-date, high-quality evidence synthesis.

5.4 Fostering multidisciplinary collaborations

The success of AMA depends on requiring seamless collaborations between statisticians, computer scientists, domain experts, and policymakers. However, interdisciplinary cooperation remains a bottleneck due to differences in methodologies, terminology, and research priorities. Addressing this challenge requires three strategic approaches: (1) interdisciplinary training programs to familiarize researchers with AMA methodologies and computational techniques; (2) joint funding initiatives to support large-scale, collaborative AMA projects; and (3) shared platforms and community to promote cross-disciplinary integration. These approaches leverage complementary expertise: statisticians ensure methodological rigor, computer scientists develop the technical framework, and domain experts provide contextual knowledge to interpret findings meaningfully. Through effective communication and trust-building, AMA can evolve into a widely adopted tool bridging computational power with domain-specific expertise.

5.5 Interpretability and transparency in AMA

As AMA tools become more sophisticated, transparency in their decision-making processes becomes increasingly paramount, particularly in high-stakes domains such as medical research where evidence synthesis directly influences clinical decisions. The integration of XAI methods into AMA represents a critical frontier in ensuring credibility and adoption. The challenge of interpretability in AMA extends beyond mere technical performance. While automated systems can significantly reduce the time and effort required for MA, their value diminishes if end-users cannot understand or trust their outputs. This is particularly crucial during the evidence synthesis phase, where complex algorithms process and integrate diverse evidence sources. Recent researchReference Luo, Sastimoglu, Faisal and Deen 56 highlights the delicate balance required between efficient automation and maintaining the depth and accuracy of evidence synthesis. Future research should prioritize the standardization of XAI integration within AMA workflows, ensuring automated processes remain transparent, reproducible, and trustworthy. Various XAI techniques, such as rule-based explanations, visual explanations, and sensitivity analysis, may integrate into AMA findings with more accessible and easier adjustments. Through these approaches, AMA can evolve into robust and widely accepted tools that enhance the quality of evidence synthesis.

6 Discussion

AMA has emerged as a transformative innovation in quantitative evidence synthesis, driven by exponential growth in literature that demands efficient, scalable, and reproducible quantitative research methods. Advanced AI, particularly “thinking models” with the capable of complex reasoning, has become a cornerstone of this evolution. This review has provided an evaluation of AMA via a descriptive lens (RQ1), analytical lens (RQ2), comparative lens (RQ3), and a future-oriented lens (RQ4). Despite AMA offering significant benefits compared to traditional MA, full automation remains aspirational rather than becoming a standard. This gap underscores the urgent imperative to harness “thinking models,” bridging technical and methodological barriers to position AMA as a critical frontier for future evidence synthesis innovation.

6.1 Methodological disparities between CMA and NMA