Introduction

Ochre is one of the most enduring forms of symbolism known in the archaeological record and has been associated with some of the earliest human burials (Bar-Yosef Mayer et al. Reference Bar-Yosef Mayer, Vandermeersch and Bar-Yosef2009). Its use in mortuary contexts extends across continents, throughout human history, with ethnographic and archaeological evidence demonstrating uses ranging from symbolic to utilitarian applications, often simultaneously (Beckett & Nelson Reference Beckett and Nelson2015; Brown Reference Brown1922; Marshal Reference Marshal1976; Rifkin Reference Rifkin2015; Zegwaard Reference Zegwaard1959). At Khok Phanom Di, a predominantly cemetery site in central Thailand, ochre was found in burials dating from ∼4000–3500 years ago. Ochre was used widely across the population; however, a significant exception to this pattern is evident among perinatal individuals, where only 61 per cent of burials contained ochre. Perinate burials without ochre were also unusual in other ways, as they lacked grave goods, and were interred in shallow, irregularly cut ‘scoop’ graves, marking a clear differentiation in burial treatment (Paris Reference Paris2021; Reference Paris2024).

This study investigates the differential treatment of perinatal burials at Khok Phanom Di, examining whether ochre use correlates with developmental age. Following this, it considers whether the presence or absence of ochre reflects distinctions between stillbirths and neonatal deaths. Two main hypotheses are considered:

-

1. Neonate hypothesis: All perinate individuals buried at the cemetery are neonates (live births), dying after birth. Ochre was applied to individuals who survived for a culturally defined period after birth.

-

2. Perinate hypothesis: Perinates at the cemetery represent both stillbirths and neonatal deaths (dying in the first few weeks of life). Ochre was used exclusively for individuals surviving birth, while stillborn infants were excluded from this mortuary practice.

Among the wider assemblage ochre appears to be a broadly unifying feature, with factors such as the size of grave and grave goods being used to mark personal differences (Paris Reference Paris2021; Reference Paris2024). The presence of non-ochred perinatal burials within the community cemetery suggests a complex interplay between inclusion and exclusion in funerary treatment. This study contextualizes these findings within bioarchaeological, cross-cultural and statistical frameworks, examining ochre use as a potential marker of personhood and social acknowledgement. Through comparisons with other burial sites and modern mortality patterns, this research aims to refine our understanding of how early societies responded to perinatal mortality.

Background and context

Ochre in archaeology and mortuary practices

Ochre research has focused on symbolism and colour theory, with powdered ochre having been reported as a cosmetic or body paint (e.g. Knight et al. Reference Knight, Power and Watts1995; Power et al. Reference Power, Sommer and Watts2013); utilitarian uses as a hafting adhesive, hide tanner, preservative, medicine, sunscreen and insect repellent (e.g. Audouin & Plissan Reference Audouin and Plisson1982; Rifkin 2011; Reference Rifkin2015; Zipkin et al. Reference Zipkin, Wagner, McGrath, Brooks and Lucas2014); evidence for processing (e.g. Clark & Williamson Reference Clark and Williamson1984; Salomon et al. Reference Salomon, Vignaud and Coquinot2012); rock art (e.g. Marshack Reference Marshack1981; Surinlert et al. Reference Surinlert, Auetrakulvit, Zeitoun, Tiamtinkrit and Khemnak2018); and geological sources (e.g. Newman & Loendorf Reference Newman and Loendorf2005; Velliky et al. Reference Velliky, Porr and Gonard2018). The earliest associations of ochre pieces with burials are found in western Asia dating to ∼92,000 bp (Bar-Yosef Mayer et al. Reference Bar-Yosef Mayer, Vandermeersch and Bar-Yosef2009). The association of ochre with burials comes in two forms: burials where the ochre has been powdered, often concentrated on and around the skeleton, referred to as ‘ochred burials’, and burials that contain ochre in a lump and/or powdered form, encompassing the former, known collectively as ‘ochre burials’. The use of ochre in burial contexts varies significantly across time and place, with some cultures using it extensively, while others appear to have applied it more selectively.

In East Asia, ochre is found in China from the early Neolithic burials (Marinova Reference Marinova2021; Norton & Gao Reference Norton and Gao2008). In Southeast Asia, ochre is found in both powdered and nodule form associated with Hòabìnhian burials. In mainland Southeast Asia, ochre burials have been recorded at Con Moong, Vietnam, dating to ∼12,000 to 11,000 bp (Thong Reference Thong1980). On Borneo, at Niah Cave, traces of powdered ochre were found in Hòabìnhian levels (∼13,000–7000 bp) associated with several inhumations (Bellwood Reference Bellwood1997, 175). At the Gua Cha site in Malaysia several burials were uncovered in Hòabìnhian deposits (∼9000 bp), with a single individual recorded as having been sprinkled with ochre (Bellwood Reference Bellwood1997, 163). Pigment was recorded at Da But and Con Co Ngua, Vietnam, from ∼7000–6500 bp (Higham Reference Higham2013). At Con Co Ngua ochre was recorded covering a single burial, but found to be staining patches of sediment in two others (Oxenham Reference Oxenham2006). The most well-documented Thai ochre burial site from the Hòabìnhian is Doi Phan Kan, dating to ∼13,000 bp, where one of three individuals (DPK E-5) was covered in ochre, with ochre pieces and grinding tools, thought to have been used for rock art, found within the grave (Imdirakphol et al. Reference Imdirakphol, Zazzo and Auetrakulvit2017; Lebon et al. Reference Lebon, Gallet and Bondetti2019). The evidence from the Hòabìnhian indicates that pigment use was not universal and may have been selective within groups. At the later site of Khok Phanom Di, ochre use was similarly widespread but not absolute, raising questions about its role in distinguishing individuals within the burial population.

Khok Phanom Di

The site of Khok Phanom Di spans ∼500 years of continuous use, during which there were periods of agricultural transition alongside environmental change. The excavation report for the site was published as seven volumes covering the excavation, chronology, and burials; the biological remains; material culture (part I and II); the subsistence and environment; and the human remains (Higham & Bannanurag 1990; Reference Higham and Bannanurag1991; Higham & ThosaratFootnote 1 Reference Higham and Thosarat1993; Reference Higham and Thosarat2004; Thompson Reference Thompson1996; Tayles Reference Tayles1999; Vincent Reference Vincent2004). The intensity of site use fluctuates over time, with higher numbers of burials in mortuary phases (MP) 2–4 (Higham Reference Higham1989). The spatial organization of the cemetery was denoted by clusters A–I; these are thought to relate to familial groups. The clusters are further broken down into stages, interpreted as ‘successive generations of the same lineage’ (Higham & Bannanurag Reference Higham and Bannanurag1990, 21). Higham and Thosarat (Reference Higham and Thosarat2004) proposed a genealogy, representing around 20 generations, within each cluster using the spatial patterns from the site, relative grave wealth and osteological features. Isotopic analysis demonstrated that adults from the initial phase were new to the region, with a patrilocal migration pattern in the most populous phases, which appears to have stopped from MP5 onwards (Bentley Reference Bentley, Higham and Thosarat2004; Bentley et al. Reference Bentley, Tayles, Higham, Macpherson and Atkinson2007).

Bioarchaeological studies indicate that the population at Khok Phanom Di faced significant health challenges. The dominant palaeopathological osseous changes observed in the assemblage were suggestive of anaemia, possibly associated with malaria or thalassaemia (Tayles Reference Tayles1999, 201). The demography of the assemblage fluctuated through the mortuary phases (MP), with high rates of infant mortality when compared with similar sites, but with lower rates of child mortality (Halcrow et al. Reference Halcrow, Tayles and Livingstone2008; Tayles Reference Tayles1999). The site had an unusually high proportion of perinates (∼0 years), but all estimated to be greater than 34 foetal weeks. The absence of younger perinates, despite preservation conditions that should have allowed their discovery, suggests intentional exclusion or alternative disposal practices (Halcrow et al. Reference Halcrow, Tayles and Livingstone2008).

A quantitative investigation of ochre presence or absence in association with demographic factors at Khok Phanom Di reported by Paris (Reference Paris2021; Reference Paris2024) demonstrated that ochre was used selectively in 82 per cent of burials throughout the site’s ∼500-year history. The initial phase contained six burials of which only a single individual, a perinate, was buried with ochre. From MP2 onward, pigment use became the predominant funerary practice at the site, with ochre coverage patterns differing among individuals. Burials that were absent of ochre after MP2 were strongly linked to a decrease in burial complexity (including grave depth and grave goods) and the individual’s age. Perinatal burials without ochre were most commonly interred in shallow, irregularly cut ‘scoop’ graves and lacked grave goods, in contrast to their pigmented contemporaries.

Of the 23 individuals without pigment, from MP2 onwards, only six were post-perinatal. Four of those were infants, all of which had poor levels of preservation when compared to the rest of the assemblage. Three of these, B10; B97; B135, were arguably difficult to age as they were highly fragmented and without grave goods. The grave goods associated with the fourth individual, B7, indicate a burial that would typically be associated with ochre; it is possible that the poor preservation of this individual prevented pigment from being identified. The two adults buried without ochre were from MP4 (one female and one male). Both had strikingly simple graves with only a single pottery vessel in each. This contrasts with others from this phase, for example the heavily beaded burials 29 and 33. The male burial, B22, was unique amongst the assemblage as the only individual buried without a skull. Analysis of his postcranial skeleton suggests that this was removed some time after death, as only the atlas (first cervical vertebrae) is missing (Tayles Reference Tayles1999). This individual was spatially isolated within MP4 and interred without ochre and without the turtle carapace ornament that characterizes male burials in MP4 and 5. His lack of burial wealth and ochre coupled with the lack of cranium suggests that this individual was singled out from the rest of the population—separation beyond the absence of ochre.

The conclusion drawn from this evidence is that the absence of pigment was reserved for a select group, dominated by perinates. Of the 47Footnote 2 perinatal individuals available for study, 29 (61 per cent) demonstrated evidence of ochre in their burial and had funerary treatment consistent with the wider assemblage; demonstrating that there is a further division within this age group. Here perinates are examined further to establish whether any additional distinctions can be made between ochred and non-ochred groups.

Perinatal mortality and personhood

Archaeological and ethnographic evidence indicates that ochre has long served as a symbol of both personal and group identity (Brown Reference Brown1922; Henshilwood et al. Reference Henshilwood, d’Errico and Watts2009; Knight et al. Reference Knight, Power and Watts1995; Rifkin Reference Rifkin2015; Watts et al. Reference Watts, Chazan and Wilkins2016). Exploring its potential role in the context of perinatal mortality necessitates an understanding of the theories surrounding the personhood of perinates. The treatment of perinates in mortuary contexts is influenced by cultural perceptions of personhood and social acknowledgement, often relating to the developmental stage of the individual. These perceptions are closely tied to the language used to describe stages of development. In bioarchaeology, the term ‘perinate’ typically refers to individuals who died around the time of birth, with some authors choosing to extend this to include seven postnatal days (Lewis Reference Lewis, Cox and Mays2000; Scheuer & Black Reference Scheuer, Black, Cox and Mays2000). The average gestation period for humans is typically 40 weeksFootnote 3 /10 lunar months. Prior to birth individuals are referred to as a ‘foetus’. ‘Neonate’ is used to describe individuals known to have been born alive, up to their first month, with ‘stillborn’ used to describe individuals who have died in the womb or during birth after 24 weeks’Footnote 4 gestation, described as a ‘miscarriage’ before this point. However, identifying these phases in the archaeological record is particularly challenging as gestational age estimates are often based on skeletal development rather than direct evidence of live birth. A distinction is made between osteological age (developmental age of the skeleton) and chronological age (age since birth). Thus, in archaeological contexts the age for perinatal individuals, of whom the point of birth is uncertain, is often described in foetal weeks. Here the term ‘perinate’ will be defined as individuals around the time of birth, and is the dominant and inclusive term used to define individuals estimated to be ∼0 years of age, with ‘neonate’ and ‘stillbirth’ used to distinguish a specific developmental stage at death. Infant is used to describe individuals from birth up to 2 years of age.

Burials reflect the identity of the dead through the eyes of the living, often dictated by cultural frameworks. This is particularly evident in the case of children and infants, who have not had the time to define their identity or personhood through their social roles or actions during life and are therefore shaped by those memorializing them in death. Yet personhood or individuality can be ascribed to those yet to be born, conceptualized through the term ‘social birth’—the knowledge of pregnancy gives rise to assigned identity by those who acknowledge the foetus (Sanger Reference Sanger2012). This identity is shaped by presumed sex, anticipated ambitions and character traits—a perception of the foetus’s ‘potential’ (Scott & Betsinger Reference Scott, Betsinger, Han, Betsinger and Scott2018). In cultures where abortion is prohibited, then arguably social birth is from the point of fertilization; or even, in the extreme, the prohibition of contraceptives implies that social birth begins with the potentiality of personhood. Yet there are often practical rites of passage that place barriers on the social and legal recognition of the individual. These can create a clear gap between personhood defined by the immediate family and social acknowledgement—a community-based identity. For example, in the Amhara and Oromiya regions of Ethiopia, traditionally neonates have not been socially acknowledged until the 40th day of life. If they die before this point, they are buried discreetly without formal mourning rites. Sisay et al. (Reference Sisay, Yirgi, Gobezayehu and Sibley2014) found that, while the older generations continue to uphold this tradition, younger individuals expressed a growing desire for greater visibility of neonatal death. Similarly, in some Taiwanese communities, where burials provide safe passage to the next life, stillborn babies are not formally acknowledged as individuals, and there are no established mourning or burial ceremonies. However, this lack of ritual does not diminish the emotional distress or feelings of loss for the immediate family (Tseng et al. Reference Tseng, Hsu, Hsieh and Cheng2017). A review of post-miscarriage care in British nursing describes a similar tension: while parents grieve their loss, there is often a lack of social acknowledgement due to legal definitions of personhood (Evans Reference Evans2012). These modern examples demonstrate an observable juxtaposition between the personal bereavement of those acknowledging the deceased’s personhood and wider social acknowledgement. By exploring perinatal mortality as a social issue, it is possible to understand how this manifests in the archaeological record.

Cross-cultural studies have shown that responses to foetal/perinate death vary widely, ranging from segregation, which Lewis (Reference Lewis, Cox and Mays2000, 42) refers to as ‘infant migration’, to elaborate displays of inclusion. One of the youngest known archaeological foetuses, estimated to be no older than 18 weeks gestation, was discovered in a miniature coffin in Ancient Egypt (Fitzwilliam Museum 2016). Archaeologically, pre-third-trimester foetuses are rarely recorded, likely due to excavation and/or preservation bias (Cunningham et al. Reference Cunningham, Scheuer and Black2016; Halcrow et al. Reference Halcrow, Tayles, Elliott, Han, Betsinger and Scott2018). However, in this case, the foetus—which would be classed as a miscarriage in modern society—was afforded the same burial traditions as adults, suggesting that their status may have been determined by family lineage rather than individual achievements. The practice of segregation of infants from the wider community is similarly well documented. A striking example is the infant cemetery of Kylindra, Greece. This cemetery contained miscarried foetuses, stillbirths and neonatal deaths, as well as a small number of infants up to 2 years old, predominantly interred in jars (Hillson Reference Hillson, Shepartz, Fox and Bourbou2009). The cemetery at Kylindra demonstrates both a clear spatial segregation of infants from the broader population and a structured, deliberate funerary tradition. The inclusion of some older infants at this site suggests a socially derived meaning behind their burial location, rather than it being dictated solely by age. These infants occupied a liminal space—on the peripheries of society, both spatially and symbolically—but the effort expended in their burial shows a distinct acknowledgement. Like the non-ochred perinates at Khok Phanom Di, infant migration reflects a carefully mediated distinction between inclusion and exclusion, reinforcing the idea that personhood and social belonging were not automatically granted at birth, but shaped by cultural norms. By considering Khok Phanom Di in the wider context of personhood and social acknowledgement, this research aims to provide insights into how past societies treated perinatal individuals in death and what this reveals about perceptions of identity and belonging.

Methods

Sample selection

This study examines a subset of 47 perinatal individuals from the 152 burials analysed for the presence of ochre as part of a broader investigation into funerary practices at Khok Phanom Di (Paris Reference Paris2021). Secondary bioarchaeological data was obtained from Higham and Bannanurag (Reference Higham and Bannanurag1990); Higham & Thosarat (1993; Reference Higham and Thosarat2004); Tayles (Reference Tayles1999); and Vincent (Reference Vincent2004). A more detailed methodology of the wider study is reported in Paris (Reference Paris2021) and Paris and Foley (in review). In the wider investigation the age of all perinatal individuals was recorded as ‘0’ years. In this study foetal weeks are used to provide greater granularity to differentiate between perinatal individuals, enabling a further investigation of the relationship between age and ochre use in burials.

Age estimation

Gestational age was estimated using maximum diaphyseal length measurements obtained from Halcrow et al. (Reference Halcrow, Tayles and Livingstone2008) and Tayles (Reference Tayles1999). These largely overlapped; however, not entirely. To calculate age in foetal weeks for the maximum number of perinatal individuals it was desirable to combine the datasets, which were then statistically compared to ensure compatibility. There are multiple methods available for calculating age in foetal weeks, all of which use different bones in their calculations. Similarly, to ensure the maximum number of individuals could be included in the study, multiple methods were used to estimate age in foetal weeks. A total of 20 calculations were used, from Scheuer et al. (Reference Scheuer, Musgrave and Evans1980), Scheuer and Black (Reference Scheuer, Black, Cox and Mays2000), Sherwood et al. (Reference Sherwood, Meindi, Robinson and May2000), Carneiro et al. (Reference Carneiro, Curate and Cunha2016) and Gowland and Chamberlain (Reference Gowland and Chamberlain2002). Individuals who were estimated to be fewer than 50 weeks by any of the 20 methods were included in the study. To achieve a single estimate for age in foetal weeks imputation was carried out using the Bayesian procedure developed by Gowland and Chamberlain (Reference Gowland and Chamberlain2002) as a baseline and filling in gaps with regression equations for missing data. The number of weeks gestation are relative and are only used for comparison within the Khok Phanom Di assemblage. The method calculated estimates for 46 of the 47 perinates (the method and justification can be found in the Supplementary Appendix).

Ochre identification

All individuals in the assemblage were laid out anatomically and an inventory taken of identifiable bones. Each bone was visually assessed and recorded for the presence of ochre, as well as an overall description of the distribution of pigment across the individual skeleton. Ochre was identified based on colour, texture and staining patterns, thereby distinguishing naturally occurring sediment discolouration from the transfer of ochre introduced to the grave. In addition to written accounts, photographs were taken of the whole skeleton and individual bones to document the ochre distribution across each individual. The presence of ochre for the most part was explicit; however, where trace amounts of ochre were observed, or ochre inclusions in sediment, the individuals were accessed combining information from the primary skeletal analysis and the literature (Higham & Bannanurag Reference Higham and Bannanurag1990; Tayles Reference Tayles1999).

Statistical analysis

A data summary was used to get a descriptive overview. A Mann-Whitney test was performed to investigate the relationship between the presence or absence of ochre and age in foetal weeks. This test was selected due to the small sample size (n=46) and the non-normal distribution of the gestational age estimates. The confidence level was set at 95 per cent, with terms with a p-value of less than 0.05 considered to have a significant influence and terms with a p-value of less than 0.0005 as highly statistically significant on the dependent variable.

The results were then compared across 20 different gestational age estimation methods, ensuring that the observed pattern was consistent regardless of the formula applied. All data were gathered in Microsoft Excel and statistical analyses were conducted in RStudio (RStudio Team 2016).

Results

Frequency of ochre use across perinate burials

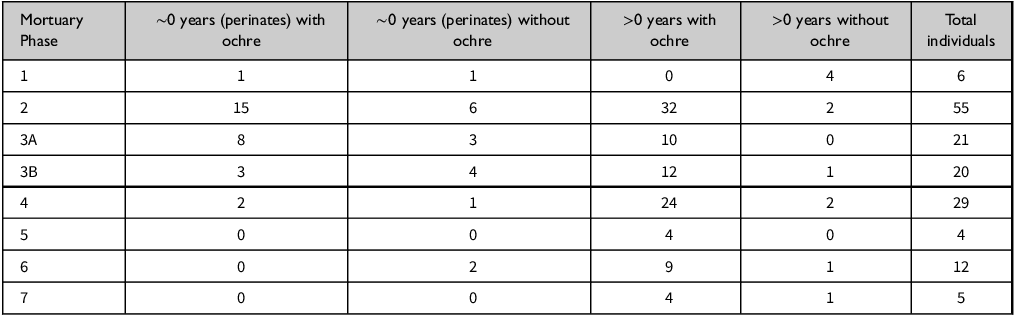

Of the 47 perinatal individuals analysed, 29 (61 per cent) showed evidence of ochre application, significantly lower than the ∼93 per cent ochre presence observed in adult burials and ∼92 per cent in children over ∼0 years of age (Paris Reference Paris2021; Reference Paris2024). Across the entire assemblage the number of burials varied across mortuary phases, with the percentage of perinates (ochred and non-ochred) also fluctuating (Table 1). The earliest burials in MP1 contained little evidence of ochre use, with only one individual showing pigment traces. In contrast, in MP2–MP4, ochre use among perinates increased but remained selective, with some individuals receiving pigment while others did not. The number of burials per phase declines after MP5, from which point there are no ochred perinates, although MP5 and 7 have no perinates at all. These findings demonstrate that ochre use was not universal within the perinatal category, raising the question of whether its application correlated with factors such as developmental age, mode of death, or social recognition.

Table 1. Distribution of presence or absence of ochre by mortuary phase, separating perinatal individuals from the broader burial population.

Relationship between age and ochre

To examine the relationship between ochre use and perinatal age, foetal week estimates for 46 perinates were compared against the presence or absence of ochre. The results indicate a statistically significant difference in age between the two groups. A Mann-WhitneyFootnote 5 test based on foetal weeks calculations from Gowland and Chamberlain (Reference Gowland and Chamberlain2002) revealed a significant difference: perinates with ochre have a mean gestational age of 40.5 weeks, compared to 39.2 weeks for those without (w=145.5, p=0.02). A traditional multi-method averaging approach showed an even greater statistical difference, with ochred individuals averaging 40.1 weeks and those absent of ochre averaging 37.2 weeks (w=160, p=0.003). This trend was consistent across all 20 methods used to estimate age in foetal weeks (Fig. 1). The data suggest a significant correlation between gestational age and ochre use. When the two MP1 perinates were excluded, accounting for the phases’ distinct ochre-related practices, the statistical significance increases, but only marginally (imputed: w=123, p=0.01; method means: w=140, p=0.002). The consistency of this pattern across different estimation models suggests that ochre was more commonly applied to individuals who had reached full term (40 weeks) or beyond, while those who died at earlier stages of development were less likely to receive ochre treatment.

Figure 1. A plot demonstrating perinatal individuals with (red) and without ochre (blue) across different age estimation methods. In all cases, while the ranges overlap, there is a significant difference in age between those with and without ochre. Those with ochre are typically older than those without. (C) Carneiro et al. (Reference Carneiro, Curate and Cunha2016); (GC) Gowland & Chamberlain (Reference Gowland and Chamberlain2002); (Sc) Scheuer et al. (Reference Scheuer, Musgrave and Evans1980); Scheuer & Black (Reference Scheuer, Black, Cox and Mays2000); (Sh) Sherwood et al. (Reference Sherwood, Meindi, Robinson and May2000). Equations for each method in Supplementary Appendix.

The overlap in the range of foetal weeks between the ochred and non-ochred perinates suggests that the distinction between the two groups was not solely developmental. Whether ochred individuals were chronologically ‘older’ remains uncertain, as it was not possible to determine whether the perinates at Khok Phanom Di were live births, stillbirths, or a combination. While ochred individuals were on average osteologically older, this does not necessarily indicate chronological age.

Discussion

The results demonstrate that ochre use in perinatal burials at Khok Phanom Di was selective and more specifically associated with osteological development and broader burial treatment. On average, burials without ochre were developmentally younger, with previous studies showing they were also predominantly (14/17) interred in shallow, irregularly cut ‘scoop’ graves, which lacked clear structural definition or grave goods (Paris Reference Paris2021; Reference Paris2024). Ochred perinates were generally found in deeper graves, with a defined rectangular shape, some containing grave goods—resembling adult burials.

This gives rise to two avenues of discussion: firstly, whether ochre use relates to biological or socially determined milestones; and secondly, whether ochre use can be associated with personal identity and/or social acknowledgement. The first point of discussion considers whether all of the perinates buried at the site were neonates who survived birth, with those buried with ochre surviving a greater number of days than those without pigment, referred to as the ‘neonate hypothesis’, which stands in opposition to the ‘perinate hypothesis’, which suggests individuals buried with ochre were live births, while those without pigment were stillborn. These hypotheses are explored in relation to known ethnographic uses of ochre. This is followed by a discussion of how the presence of ochre reflects or reinforces concepts of personhood and social acknowledgement at Khok Phanom Di.

Neonate hypothesis: ochre as a milestone marker of social acknowledgement

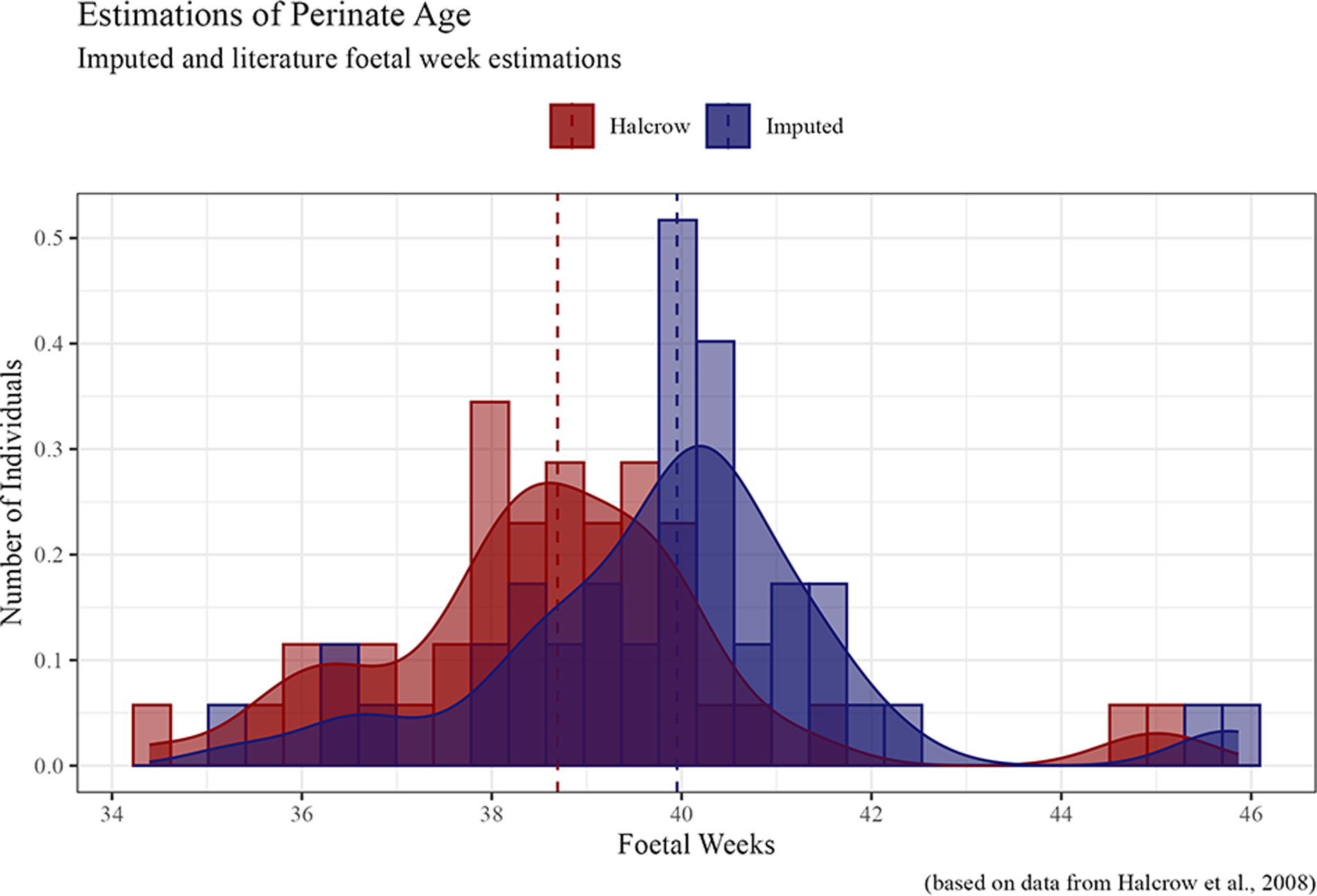

There are a number of potential differences within a group of neonates that could provide an explanation for different burial treatment: chronological age; sex; origin or status of the parents or family. The separation based on chronological age is supported by an investigation into infant death in prehistoric Thailand by Halcrow et al. (Reference Halcrow, Tayles and Livingstone2008). Across seven sitesFootnote 6 all individuals had reached at least 29 weeks’ gestation, indicating survival into the third trimester. Among this group Khok Phanom Di has a significantly different age-at-death distribution, lacking perinates fewer than 34 foetal weeks. The study also highlighted clustering around 38–40 weeks and suggested that age estimates may have been slightly overestimated due to a reliance on European standards. These findings led Halcrow and colleagues (Reference Halcrow, Tayles and Livingstone2008, 387) to argue that the Khok Phanom Di perinates were neonates who may have lived for days or weeks after birth; and that miscarriages and stillbirths were treated differently and disposed of elsewhere. The imputed foetal week values presented here also cluster around the 40-week mark (Fig. 2), the argument being that a longer gestation corresponds to a greater likelihood of surviving for several days after birth (Dance Reference Dance2020). This implies that individuals buried with ochre were, on average, both chronologically and developmentally older than those without ochre. This interpretation helps to explain the overlap in the ages of the ochred and non-ochred burials (Fig. 1), as these values reflect foetal developmental rather than time since birth. Consequently, the presence of ochre may be linked to factors associated with survival in the days following birth—a milestone event.

Figure 2. Histogram showing the density of individuals and estimations of perinate age in foetal weeks, comparing the imputed values used in this paper (blue) and values from Halcrow et al. (Reference Halcrow, Tayles and Livingstone2008) (red). The imputed values suggest age in foetal weeks was older than that previously described in the literature and clusters around the 40-week (full-term) mark. Dashed lines represent the mean.

Rites of passage are deeply embedded in both historic and modern cultural practices worldwide. In cases of perinatal mortality, these rites often dictate differential burial practices. In Ireland, Cilliní were cemeteries designated for unbaptised infants, whom the Roman Catholic Church deemed unsuitable for burial in consecrated ground (Murphy Reference Murphy2011). While burials at the Cilliní resembled those in Roman Catholic cemeteries, they lacked normative religious rituals. This differential treatment extended to certain marginalized older individuals (possibly like B22 and B27 at Khok Phanom Di), those who were deemed unworthy by the Church such as strangers or criminals, and stillborn infants (Murphy Reference Murphy2011). If the non-ochred individuals at Khok Phanom Di did not qualify for the customary burial afforded to the vast majority of post-MP1 society, this raises the possibility that ochre absence was a deliberate social marker rather than a purely age-related factor. This further suggests that the use of ochre was symbolic rather than utilitarian, although practical functions of ochre, such as being a preservative or sunscreen, would not be precluded by age. This implies that the presence of non-ochred perinates in the main cemetery granted a degree of social inclusion.

This is further supported by ethnographic examples of ochre used as a body paint for culturally mediated activities. The Ovahimba have gender- and role-based ochre practices (Rifkin Reference Rifkin2015); the San of Botswana historically used ochre in puberty and marriage rituals (Marshal Reference Marshal1976, 276–7); the Andamanese use ochre for both medicinal and ceremonial purposes, symbolizing both blood and fire (Brown Reference Brown1922, 125, 318); the Asmat of New Guinea cover their skin and that of their dead in ochre at specific events, including funerary practices (Zegwaard Reference Zegwaard1959). Evidence for ochre use in the past has likewise been associated with symbolic or ritual behaviour (e.g. Henshilwood et al. Reference Henshilwood, d’Errico and Watts2009; Hovers et al. Reference Hovers, Ilani, Bar-Yosef and Vandermeersch2003; Knight et al. Reference Knight, Power and Watts1995; Watts et al. Reference Watts, Chazan and Wilkins2016). If the perinates at Khok Phanom Di were all live births, it appears that those with ochre qualified for pigment soon after birth, explaining its prevalence in the assemblage. However, this rite was not conferred at birth, as the absence of ochre is largely restricted to the least developed individuals. This suggests that from MP2 onwards, there was an acknowledgement of neonate personhood—one that non-ochred individuals did not survive long enough to experience.

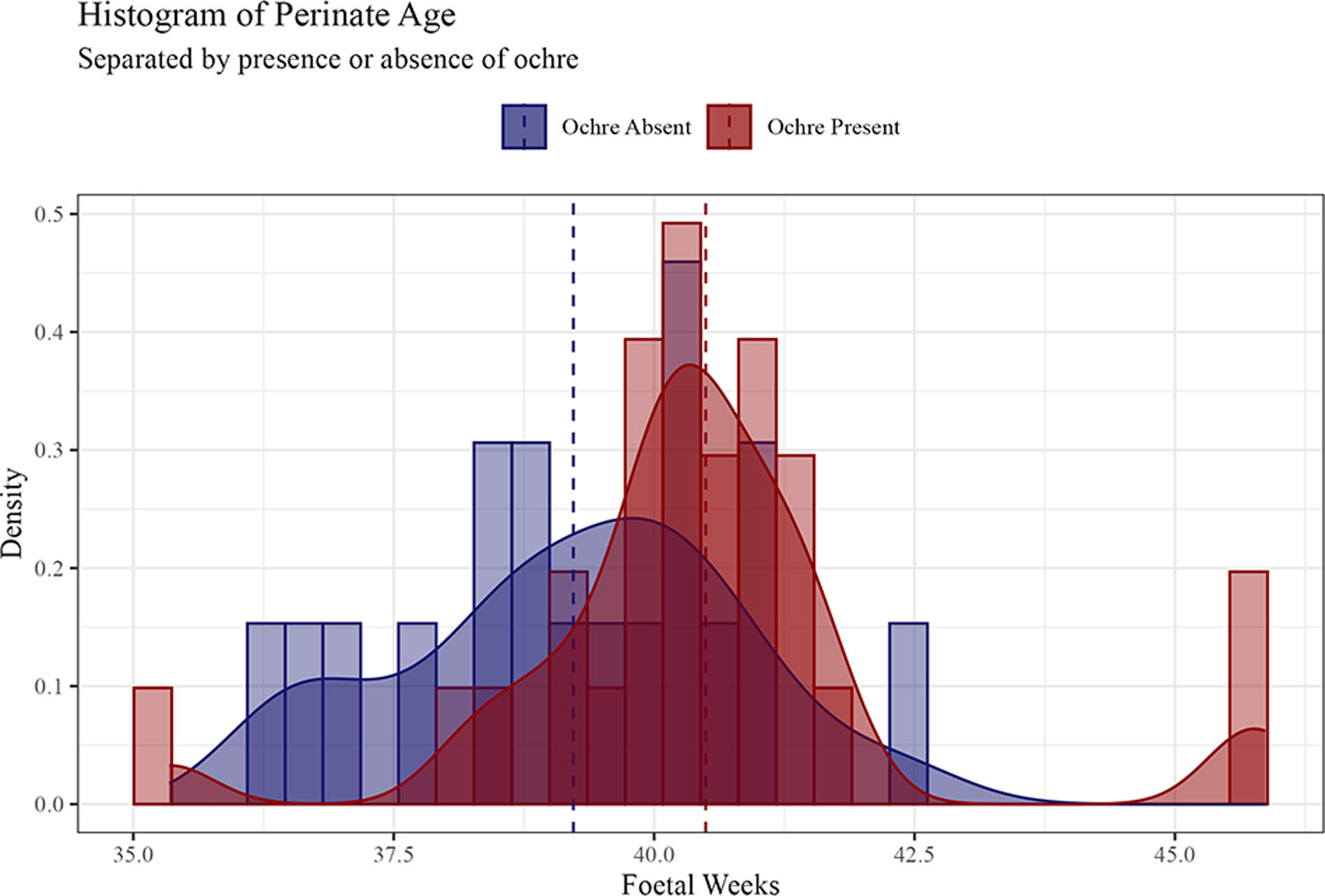

Perinate hypothesis: ochre as a marker of live births

An alternative interpretation is that ochre was applied exclusively to individuals who had been live births, while those who were stillborn were excluded from this practice. Today, the leading cause of stillbirth and neonate death is premature birth, with half of stillbirths occurring during labour. The stage of pregnancy which poses the greatest risk of stillbirth is the intrapartum period, 37–40 weeks (WHO 2021). The mean gestational age for non-ochred perinates falls within this range, whereas ochred perinates falls just outside it (Fig. 3). However, confidence in the adjusted or imputed values used in this research face similar problems described in Halcrow et al. (Reference Halcrow, Tayles and Livingstone2008), in that the population is incomplete. Waldron (Reference Waldron1994) describes the difficulty of calculating perinate mortality accurately, as it requires the total number of births—an archaeologically indeterminable figure. Additionally, as with Halcrow et al. (Reference Halcrow, Tayles and Livingstone2008), the age estimations here are based on calculations from European standards, which typically result in higher age estimates for Southeast Asian perinates. While this may affect the absolute values, it does not alter the overall distribution of ochred versus non-ochred individuals. Thus, rather than looking at the foetal week data in absolute terms, analysing the shape of the distribution and comparing it to known modern perinate mortality rates reveals potential correlations with ochre use.

Figure 3. Histogram of ochre presence and absence based on age in foetal weeks. Dashed lines represent the mean. The mean for the absence of ochre falls within the most risky stage of pregnancy, 37–40 weeks, whereas the mean for those with ochre falls just outside of this range.

Figure 4 presents death rates by foetal week of stillbirths, neonatal deaths and their combined total, from modern British data. Except for an outlier at 35 weeks, the combined curve of stillbirth and neonatal death aligns more closely with the pattern of ochre presence and absence than either category alone (UKGov 2017). It must be acknowledged that no directly analogous dataset exists for Khok Phanom Di in terms of historical period or cultural context. While modern medical interventions significantly influence survival rates, the overall shape of the curve potentially has bioarchaeological relevance, reflecting general trends in survivorship by gestational age and supporting the perinate hypothesis. It remains unclear whether the increase in perinate survival rates from prehistory to the present has been evenly distributed across the gestational weeks—maintaining a similar curve—or whether medical advancements have reshaped the curve by targeting specific phases of development. For instance, cervical cerclage, used between 12 and 24 weeks, has been shown to reduce the risk of preterm birth by 30 per cent and decreases perinatal mortality by 35 per cent, yet has no effect on the perinatal mortality of those who naturally reach later stages of development (Berghella et al. Reference Berghella2011). Furthermore, at Khok Phanom Di stillbirth rates in the later phase of pregnancy were likely high relative to comparable communities, given the presence of both malaria and thalassaemia (Tayles Reference Tayles1999). Genetic forms of thalassaemia, which are prevalent in Southeast Asia today, have been shown to commonly cause stillbirth, particularly in the third trimester (Weatherall Reference Weatherall2010). The neonatal line on teeth could provide more definitive evidence for post-birth survival (Booth Reference Booth, Gowland and Halcrow2020; Canturk et al. Reference Canturk, Atsu, Aka and Dagalp2014; Hurnanen et al. Reference Hurnanen, Visnapuu, Sillanpää, Läyttyniemi and Rautava2017; Janardhanan et al. Reference Janardhanan, Umadethan, Biniraj, Vinod Kumar and Rakesh2011); the destructive nature of this technique prevented its application in this study.

Figure 4. The bars show the percentage of perinatal individuals from Khok Phanom Di buried with (red) and without ochre (blue) by age in foetal weeks, overlain with modern perinate mortality data from UKGov (2017). The curve created by the presence of ochre (red) follows the general trend of the modern data excluding the outlier born at 35 weeks, but most closely aligns with that for perinate death (palest green), which has a sharper incline than either still birth or neonatal death alone.

The perinate hypothesis links ochre to life, aligning with interpretations of ochre as a symbol of blood and its extension in burial customs to represent life after death (Brown Reference Brown1922, 125, 318; Jones Reference Jones2018). At Khok Phanom Di, Higham (Reference Higham, Renfrew, Boyd and Morley2015, 286) suggested that the use of ‘blood-red ochre’ and pottery vessels containing consumables hinted at ‘a belief in immortality and rebirth beyond death’. However, rebirth presupposes life, which may explain the absence of ochre in stillborn burials. If ochre symbolized the potential for life after death, its exclusion from the graves of individuals who never lived suggests a fundamental distinction in how society perceived them. Similarly, the absence of ochre in certain older individuals’ burials may indicate a societal decision against their rebirth. This perspective aligns with broader anthropological observations on burial practices. Härke (Reference Härke2014) observed that grave goods in some societies served as a means of disposing of ‘polluted items’ to protect the living. Extending this idea to Khok Phanom Di, stillborn infants may not have been buried with ochre or artefacts because they had not lived long enough (or at all) to ‘contaminate’ objects. This interpretation further underscores the selective and socially significant role of ochre in burial customs.

Ochre’s utilitarian functions provide another layer of interpretation in support of the perinate hypothesis. Ochre has been shown to function as a preservative, having antibacterial qualities (Audouin & Plisson Reference Audouin and Plisson1982; Rifkin Reference Rifkin2011). In a purely utilitarian sense this explanation does not apply here, as decomposition would affect stillbirths and live births alike. However, if ochre’s preservative properties were symbolically linked to concepts of spiritual preservation or transition, its selective application becomes more comprehensible. For instance, among the Anga of Papua New Guinea ochre is employed in both ritualistic and practical preservative roles within the secondary funerary treatments and mummification processes (Beckett & Nelson Reference Beckett and Nelson2015), reinforcing concepts associating ochre with life and continuity beyond death.

From a strictly utilitarian perspective, ochre may have been used as a mosquito repellent or sunscreen, particularly in an estuarine environment with a humid, sunny climate. This suggests that ochre was not necessarily a deliberate component of mortuary practices but was instead part of daily life, with its presence in burials resulting from a lack of removal before burial. For stillborn individuals, the application of ochre for medicinal purposes would have been unnecessary, potentially explaining its absence from their burials. While this interpretation aligns with ethnographic and experimental evidence for ochre use, the substantial quantities found and the widespread distribution of pigment across various bone types suggest that ochre was not merely a passive element of funerary practices (Paris Reference Paris2021; Paris & Foley in review).

Ochre personhood and social acknowledgement

The two contrasting hypotheses presented above cannot be resolved without further investigation; however, the absence of individuals younger than 34 foetal weeks suggests a normative exclusion of younger perinates from traditional burial rites, reinforcing the role of developmental markers in determining burial treatment. While the precise qualifying developmental stage for ochre use cannot be established without destructive methods, the role of ochre as a marker of identity can still be considered.

Cemeteries serve as unified spaces for collective commemoration; however, the diversity of individuals and practices within them provides valuable insights into social organization, and the relationships between personal and group identity. The inclusion of perinates without ochre within the cemetery boundaries, albeit with simple mortuary treatment, implies a partial social acknowledgement. They appear to be on the fringe of society, spatially included, if not culturally. Historical and archaeological research into the aforementioned Cilliní suggests that the relatives of the dead viewed them in the same way as those buried in consecrated ground, and it was only the Roman Catholic Church that sought to marginalize them (Murphy Reference Murphy2011). This highlights how burial practices can conform to societal conventions of inclusion or exclusion while simultaneously reflecting deeper social divides. Despite the differential treatment of the non-ochred individuals at Khok Phanom Di, their inclusion in the main cemetery suggests that those burying them perceived them as part of the broader society, even if that society did not grant them full burial rites.

Globally, the social acknowledgement of a person—and therefore their inclusion in society—is often bound by culturally specific conventions, which are frequently reflected in, and sometimes limited by, language. Age-related terminology evolves based on social or academic developments and the context in which they are being used (Scheuer & Black Reference Scheuer, Black, Cox and Mays2000). In medicine, medico-legal studies, forensic anthropology, osteology, and archaeology, the criteria and evidence used can vary, leading to inconsistencies (Blake Reference Blake, Han, Betsinger and Scott2018; Halcrow et al. Reference Halcrow, Tayles, Elliott, Han, Betsinger and Scott2018; Lewis Reference Lewis, Cox and Mays2000; Scheuer & Black Reference Scheuer, Black, Cox and Mays2000; Reference Scheuer and Black2004). The perception of sub-adults, including foetuses, and their rights is constantly shifting due to societal change. For example: is a stillbirth or miscarriage considered a death? In the United Kingdom, a neonatal death is recorded like any other, requiring both a birth and death certificate, recognizing the life of the infant—an acknowledgement of personhood. In contrast, stillborn babies receive a single and separate form of registration, and until 22 February 2024, there was no formal provision for registering miscarriages; even now, registration remains optional (RCOG 2005; UKGov 2024). This legal framework categorizes infant loss into three distinct groups. Further complicating matters, under the Human Tissue Act 2004, a miscarriage is legally classified as ‘tissue from a living person’—not of the foetus, but of the mother. As such, no formal permission is required for disposal (HT Act 2004; HTA 2015). Only since 2015 did the Human Tissue Authority issue guidance recommending that women should be offered the choice of burial, cremation or incineration following miscarriage (HTA 2015). This shift allows women to move beyond the legal linguistic framework of infant personhood and make a personal choice about whether to acknowledge a foetus’s individual identity. The fluid boundaries of personhood—whether individual acknowledgement or societal recognition—highlight why burial practices, and in this case ochre use, are invaluable for understanding social organization in ways that cannot be seen through osteological markers alone.

At Khok Phanom Di the variation in ochre application across individuals suggests it signified personhood, reflecting broader complexities of identity within society. The absence of ochre among certain perinates implies anonymity, yet their inclusion within the cemetery indicates some level of collective recognition. Cannon and Cook (Reference Cannon and Cook2015) argue that responses to infant death are shaped by past community experience, social constraints and individual psychology, rather than attachment or detachment and mortality rate. Similarly, Cobb and Croucher (Reference Cobb and Croucher2020) describe how human experiences, including grief, are assemblages of personal and societal influences, applicable in both contemporary and historical contexts. While we cannot infer emotion from bioarchaeology, the evidence for fertility identifies physiological changes that are fairly uniform in the human experience. The evolving discourse on perinatal loss underscores its shifting visibility. Moulder (Reference Moulder1998) noted that stillbirth remained largely unspoken about until women began sharing their experiences in the last quarter of the twentieth century. Decades later, high-profile figures such as television personality Chrissy Teigen and footballer Cristiano Ronaldo have used their social platforms to articulate their grief publicly, challenging longstanding taboos (Valenti Reference Valenti2020). Teigen’s candid account in 2020 ignited global conversations about miscarriage, while Ronaldo’s 2022 announcement of perinatal loss resonated particularly in male-dominated spaces. His public mourning was met with an unprecedented display of solidarity, as rival football fans united in commemoration, illustrating the potential for paternal grief to receive broader social acknowledgement. Perinatal loss has historically been framed through a gendered lens, centring the experience of the child-bearer and often excluding others affected, such as fathers, siblings and extended families. Public expressions of grief serve not only to validate individual mourning but also establish a form of social recognition enabling the deceased to enter the public consciousness and achieve social acknowledgement. At Khok Phanom Di, the deliberate restriction of ochre use and personal items among the youngest perinates suggests a denial of personal identity, yet their burial within the cemetery signifies collective belonging. This controlled funerary practice reflects broader societal structures of inclusion and exclusion, offering insight into the community’s conceptualization of identity and personhood.

Conclusion

At Khok Phanom Di, ochre appears to function as a marker of identity. Burials lacking ochre were predominantly those of perinates, though approximately 38 per cent of perinate burials did include ochre. Further analysis of these burials revealed that non-ochred perinates were generally smaller in skeletal size, suggesting a younger age. This was accompanied by simpler, smaller scoop graves, in contrast to the more elaborate graves of ochred individuals. The absence of ochre in perinate burials has been discussed in terms of two hypotheses. The ‘neonate hypothesis’, which posits that all the perinates were neonates (dying days or weeks after birth), is supported by archaeological and ethnographic examples of identity-based milestones. In contrast, the ‘perinatal hypothesis’, that ochre distinguished neonatal deaths from stillbirths, is supported by modern mortality data, which show that rates of neonatal death and stillbirth across foetal weeks align with ochre presence or absence.

A secondary examination of ochre use at Khok Phanom Di reveals its role in reinforcing individual identity, with its absence amongst perinates suggesting a lack of recognition of their personhood. In this culture, ochre appears to have been an essential part of marking a person’s life, whether for symbolic or practical reasons. For non-ochred perinates they had sufficient recognition to allow spatial inclusion not afforded to those under 34 weeks, but not enough acknowledgement to permit the full funerary practices afforded to the vast majority, including 62 per cent of perinates. The inclusion within the conventional burial place, but distinctly simple mortuary practices, in contrast to more elaborate funerary practices, suggest that the infants without ochre sit on the fringes of social acknowledgement, without personal identity.

The profound physical and psychological toll that such high rates of perinate mortality would have on a community cannot be ignored, nor how that might influence funerary treatment of infants. Expressions of perinatal loss reflect a desire for the deceased to be acknowledged, and when these are formalized through funerary treatment or public declaration, they become acts of commemoration embedded in social memory. The complexities of personal identity at Khok Phanom Di should be explored further, particularly in the differential use of ochre among individuals. Halcrow and colleagues (Reference Halcrow, Tayles and Livingstone2008, 372) note that bioarchaeology has been underutilized in exploring perinatal mortality as a social issue. They argue that inclusion and exclusion in cemeteries, along with the analysis of age distribution, can aid in understanding of burial practices. The use of ochre at Khok Phanom Di clearly illustrates the tension between cultural exclusion and spatial inclusion, revealing a distinction between personal identity and social recognition—an important contribution to understanding personhood and social acknowledgement in Neolithic Thailand.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Appendix with figures may be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774325100097

Acknowledgements

I express sincere gratitude to the 1985 excavation team and The National Fine Arts Department and the Regional Office in Nakhon Ratchasima for permission to access the human remains from Khok Phanom Di, especially Janaung Supassy and Jaruk Wilaikeaw. Further thanks to Professor Robert Foley for his supervision; and Professor Charles Higham and Dr Rachanie Thosarat who facilitated my work in Thailand. This research was carried out under the research permit of the University of Otago and supported by University of Cambridge fieldwork funding from the McDonald Institute, Department of Archaeology.