Introduction

Different aquatic environments are influenced by various factors that can favour the proliferation of macrophytes (Lacoul and Freedman, Reference Lacoul and Freedman2006), aquatic plants that are essential for maintaining the ecological balance of freshwater systems (Chambers et al., Reference Chambers, Lacoul, Murphy, Thomaz, Balian, Lévêque, Segers and Martens2008). Their abundant presence not only provides structural complexity, offering shelter and food for a wide range of aquatic organisms (Thomaz and Cunha, Reference Thomaz and da Cunha2010; Montiel-Martínez et al., Reference Montiel-Martínez, Ciros-Pérez and Corkidi2015; Diniz and do Nascimento Moura, Reference Diniz and do Nascimento Moura2022), but also contributes to water oxygenation, nutrient cycling, pollutant filtration, and margin stabilisation, ultimately enhancing environmental quality (Thomaz, Reference Thomaz2023).

Moreover, macrophyte cover can significantly alter habitat conditions and species composition (Thomaz et al., Reference Thomaz, Dibble, Evangelista, Higuti and Bini2008) and can cause significant variations in different ecological indices (Diniz et al., Reference Diniz, Dantas and do Nascimento Moura2023), promoting an increase in some (such as diversity and richness) and a reduction in others (such as equitability and functional structure). Overall, multiple studies indicate a positive relationship between macrophytes and increased species richness, largely due to the environmental heterogeneity (e.g., Maia-Barbosa et al., Reference Maia-Barbosa, Peixoto and Guimarães2008). In tropical regions, floating aquatic plants often dominate shallow lakes and play a key role in shaping trophic interactions involving zooplankton and their predators (Dos Santos et al., Reference Dos Santos, Stephan, Otero, Iglesias and Castilho-Noll2020). Crustacean zooplankton demonstrate high resilience through various adaptive strategies, such as vertical migrations within the water column (Gabriel and Thomas, Reference Gabriel and Thomas1988), and their capacity to resist adverse conditions is a key survival mechanism (De Meester, Reference De Meester1996; Ringelberg, Reference Ringelberg2009; Kiørboe et al., Reference Kiørboe, Saiz, Tiselius and Andersen2018). In adverse conditions, zooplankton tend to prioritise the preservation of their genotypes, which may lead to behavioural, morphological, or life cycle changes aimed at ensuring reproductive success and population continuity (Arenas-Sánchez et al., Reference Arenas-Sánchez, López-Heras, Nozal, Vighi and Rico2019; Sha et al., Reference Sha, Tesson and Hansson2020; McKnight et al., Reference McKnight, Jones, Pearce and Frost2023).

Beyond their adaptive capacity, zooplankton also play a fundamental ecological role and occupy a central position in aquatic food webs, as their interactions with primary producers influence the overall functioning of aquatic ecosystems and they are also useful indicators of trophic status (Pociecha, Reference Pociecha, Bielańska-Grajner, Kuciel and Wojtal2018; Sterner, Reference Sterner and Likens2009). Furthermore, the abundance, diversity, and community dynamics of these organisms help reveal key physical and chemical processes in aquatic environments, shaping the structure of biological communities (Winder and Schindler, Reference Winder and Schindler2004). These processes drive environmental heterogeneity, both in artificial reservoirs (e.g., Nogueira, Reference Nogueira2001) and in natural lake systems (e.g., Simões et al., Reference Simões, Nunes, Dias, Lansac-Tôha, Velho and Bonecker2015), which contribute directly to zooplankton diversity by harbouring specific and varied species compositions (Cabral et al., Reference Cabral, Guariento, Ferreira, Amado, Nobre, Carneiro and Caliman2019). Moreover, zooplankton richness may also differ between these two types of systems due to their distinct environmental conditions (Cabral et al., Reference Cabral, Diniz, da Silva, Fonseca, Carneiro, de Melo Júnior and Caliman2020).

The Paranapanema River has been intensively studied in limnological terms since the 1970s, but studies have intensified since 1990 (Henry, Reference Henry2014). Certain sections of this river host marginal lagoons, formed through geological and paedological interactions, such as erosion, depressions, sand deposition, and dam modifications, occurring mainly in the region where the reservoirs begin (upstream). These features promote both water input and retention, enabling the formation of lentic habitats adjacent to the river. Such environments are ecologically rich and diverse, due to their high structural and functional heterogeneity (Stephan, Castilho-Noll, and Henry, Reference Stephan, Castilho-Noll and Henry2017). Although often undervalued, these freshwater lagoons play a crucial role in tropical ecosystems. Characterised by calm, shallow waters, they maintain a dynamic connection with the river channel and exhibit seasonal variability in ecological conditions (Rodrigues et al., Reference Rodrigues, Train, Roberto and Pagioro2002).

In tropical regions, seasonal climatic shifts between rainy and dry periods exert strong influence on aquatic communities, promoting significant ecological variations (Alves et al., Reference Alves, Pinheiro-Silva, Schuster, Matthiensen and Petrucio2022; Santana et al., Reference Santana, Weithoff and Ferragut2017). These environmental fluctuations directly affect the distribution and abundance of microcrustaceans (Blettler and Bonecker, Reference Blettler and Bonecker2007), and their responses can occur over short temporal scales, highlighting their ecological plasticity in adapting to changing habitats (Sarma, Nandini, and Gulati, Reference Sarma, Nandini and Gulati2005).

Despite the recognised influence of limnological factors and habitat structure on zooplankton, few studies integrate the roles of seasonality, macrophyte presence, and limnological variables in shaping microcrustacean communities in tropical lake systems. While many studies explore the influence of abiotic conditions or macrophyte habitats in isolation (Navarro Law et al., 2006; Alahuhta et al., Reference Alahuhta, Kanninen, Hellsten, Vuori, Kuoppala and Hämäläinen2013; Manolaki and Papastergiadou, Reference Manolaki and Papastergiadou2013; Reference Manolaki and Papastergiadou2016), and also assess seasonality in isolation (Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Albuquerque, Aguiar and Catarino2001; Mormul et al., Reference Mormul, Esteves, Farjalla and Bozelli2015; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Yan, Wang, Zhang and Wang2020), very few studies adopt an integrative approach capable of disentangling their effects under seasonal regimes, especially in conjunction with other biological groups, such as zooplankton.

It is essential to understand how these factors interact, as macrophytes and seasonal variation do not operate independently. Macrophyte presence alters habitat complexity and resource availability for zooplankton (Thomaz and Cunha, Reference Thomaz and da Cunha2010), while seasonal shifts influence macrophyte biomass (Meng et al., Reference Meng, Yu, Xia, Zhang, Ma and Yu2023), hydrology (Sahoo et al., Reference Sahoo, Guimarães, Souza-Filho, Silva, Silva Júnior, Pessim, Moraes, Pessoa, Rodrigues, Costa and Dall’agnol2016), and water quality (Travaini-Lima et al., Reference Travaini-Lima, Milstein and Sipaúba-Tavares2016). These changes can affect the structure and dynamics of zooplankton communities. Zooplankton responds not just to individual drivers but to the combined effects of vegetation cover and seasonal limnological conditions, which together define, for example, the availability of refuge (Meerhoff et al., Reference Meerhoff, Mazzeo, Moss and Rodríguez-Gallego2003). Therefore, assessing these components in an integrated framework is key to capturing the ecological processes that shape zooplankton diversity and composition in tropical freshwater systems.

In this context, the present study aimed to investigate the influence of seasonality (dry and rainy periods), presence of aquatic macrophytes and limnological variables on the composition, richness and diversity of microcrustaceans (Cladocera and Copepoda) in a tropical lake. Based on these considerations, we expected that: (1) microcrustacean richness would be higher during the rainy season compared to the dry season, due to expanded aquatic habitats that provide more ecological niches and resources for colonisation and (2) the presence of macrophytes would increase zooplankton richness and abundance, as these environments offer shelter from predators, greater environmental stability, and the formation of microhabitats, expanding the diversity of ecological niches available.

Material and methods

Study area

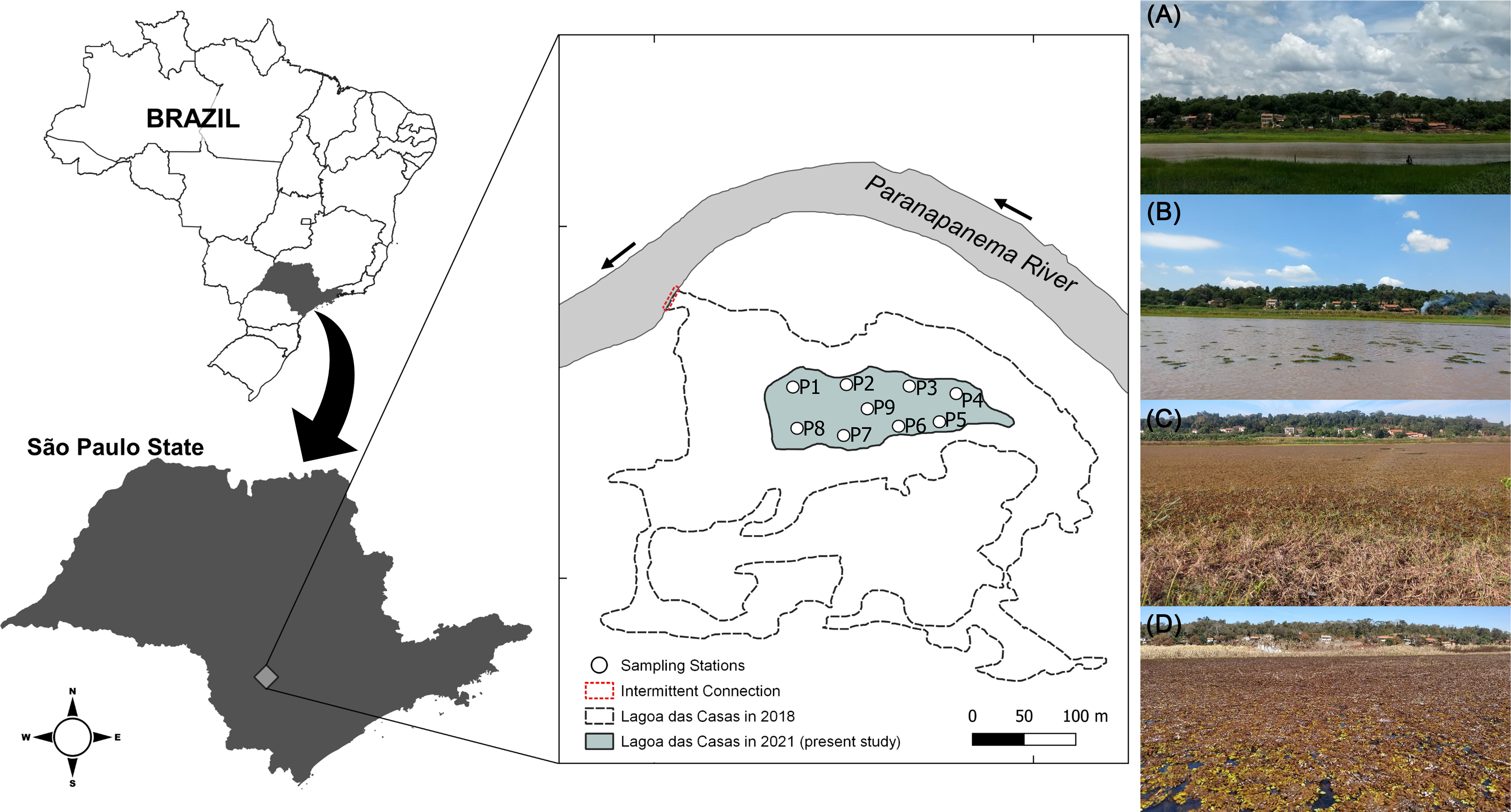

This study was conducted in the Lagoa das Casas (Angatuba, São Paulo State, Brazil), a small and shallow marginal lake to the Upper Paranapanema River, size of approximately 400 X 200 metres, which during our study remained disconnected and isolated from the main river (Figure 1). We randomly selected nine sampling stations (P1–P9) within the lake during four campaigns: November 2020 (Figure 1a), February 2021 (Figure 1b), May 2021 (Figure 1c), and August 2021 (Figure 1d). November and February correspond to the rainy season, while May and August represent the dry season. In the dry season, total macrophyte coverage was observed in the lake (as Figure 1c, d) as the depth decreased. These nine sampling stations were established to cover the full extent of the lake and capture any potential spatial gradients in environmental conditions or community structure.

Figure 1. Study area location and sampling site distribution in a lake marginal to the Paranapanema River (−23°28.370’, −48°38.280’) in Angatuba, São Paulo State, Brazil. A. November/2020, B. February/2021, C. May/2021 and D. August/2021.

Furthermore, the average temperatures during the rainy months (November and February) are 21.1°C and 22.9°C, with average precipitation of 135 mm and 181 mm, respectively. During the dry months (for example, May and August), the average temperatures are 17.8°C and 17.6°C, and the average precipitation is 64 mm and 39 mm, respectively (Climate-data.org, 2025).

The macrophyte colonisation did not vary across the nine sites. All sites were located with similar depths and exposure to sunlight, providing relatively uniform conditions for macrophyte development. This consistent presence allowed us to compare the zooplankton community under similar vegetative cover conditions throughout the lake in months with the presence of macrophytes (May and August).

Field samplings

Sampling (P1-P9) was conducted using a conical zooplankton net with a 68 µm mesh opening. Each sample involved filtering 200 litres of the sub-surface (20 cm) with the assistance of a 10-litre container to control the water volume. At each sampling occasion, samples for one quantitative (for abundance) and one qualitative analysis (for species richness and composition) were obtained. The samples were fixed with 4% formaldehyde buffered with calcium tetraborate.

All samples were collected in the morning, between 9:00 and 11:00 AM. The sampling stations were selected to cover the ecological variability within the lake, including differences in depth and macrophyte cover.

Limnological variables

Sub-surface water samples from each site were collected for analysis of some physical and chemical variables (temperature using a thermometer and electrical conductivity, turbidity, dissolved oxygen, and pH using an MS Tecnopon probes®). Water transparency was measured using a Secchi disk and the concentrations of chlorophyll-a were obtained according to Talling and Driver (Reference Talling and Driver1963).

All limnological variables were measured at the same nine stations, on the same days and with the same frequency as the zooplankton sampling, during each campaign.

Zooplankton analysis

The zooplankton samples were transferred to acrylic chambers and visualised in a stereoscopic Zeiss Stemi 305. Adult individuals (cladocerans and copepods) were identified using an Olympus CS microscope with specialised bibliographies such as Damborenea et al. (Reference Damborenea, Rogers and Thorp2020), Elmoor-Loureiro (Reference Elmoor-Loureiro1997), Sousa and Elmoor-Loureiro (Reference Sousa and Elmoor-Loureiro2019), Perbiche-Neves et al. (Reference Perbiche-Neves, Boxshall, Previattelli, Nogueira and Rocha2015), and the Cladocera do Brasil website (2025).

For the nauplii quantitative analyses (separated in the orders Calanoida and Cyclopoida), each sample was individually homogenised and extracted using a 1 mL Stempel pipette, transferred to Sedgwick-Rafter chamber and on an optical microscope. Cladocerans, copepodites and adult copepods were quantified in stereoscope Zeiss Stemi 305 by square acrylic chambers following the same subsampling process. A minimum of 100 individuals from each group per sample were quantified until the stabilisation of richness. The final abundance was expressed in individuals per cubic metre (m3) and expressed in individuals/L for boxplot graphs.

Data analysis

Box plots were used to visualise spatial and seasonal patterns of variation in limnological variables, microcrustacean richness, and abundance, providing an overview of data distribution.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used to organise physical and chemical data standardised using Pearson’s correlation. This was followed by Non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS), which assessed the spatial and temporal ordination of microcrustacean community composition using the metaMDS() function with Bray-Curtis distance on an abundance matrix. Finally, a distance-based redundancy analysis (db-RDA) using the balanced component of Bray-Curtis dissimilarity (beta.bray.bal) via the beta.pair.abund() function was performed to investigate the influence of environmental variables on community structure.

Kruskal-Wallis (KW) tests were used due to non-normal distribution of the data and determined significant differences in microcrustacean richness and abundance between dry and rainy periods, between sampling months, and in relation to the presence or absence of macrophytes, and also compared environmental variables. When significant results were found, Dunn’s post-hoc test was applied using the dunnTest() function. To enhance these analyses, Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA) was performed using the adonis() function from the vegan package to assess whether microcrustacean community composition varied significantly between time periods. No prior transformation was applied, and assumptions of dispersion homogeneity were verified using betadisper().

A Pearson correlation matrix was used to explore potential relationships between environmental variables and community composition to aid in the interpretation of ecological patterns. Shannon and Simpson diversity indices were calculated to assess the alpha diversity of microcrustaceans (Cladocera and Copepoda) during the sampled months and across seasonal periods.

All statistical analyses were performed in R (version 4.4.2, R Core Team 2024) using the packages vegan (Oksanen et al., Reference Oksanen, Simpson, Blanchet, Kindt, Legendre, Minchin, O’Hara, Solymos, Stevens, Szoecs, Wagner, Barbour, Bedward, Bolker, Borcard, Carvalho, Chirico, Caceres, Durand, Evangelista, FitzJohn, Friendly, Furneaux, Hannigan, Hill, Lahti, McGlinn, Ouellette, Cunha, Smith, Stier, Braak, Weedon and Borman2025), ggplot2 (Wickham, Reference Wickham and Wickham2016), ggfortify (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Horikoshi and Li2016), dunn.tests (Dinno, Reference Dinno2024), ggcorrplot (Kassambara and Patil, Reference Kassambara and Patil2023), and betapart (Baselga et al., 2021).

Results

Spatial-temporal trends in microcrustacean community

The microcrustacean community was composed of seven species of Copepoda and 24 species of Cladocera (Complete list in Supplementary Material 1). Seasonally, the abundance of Cladocera decreased, particularly in May and August (Figure 2a) during the dry season, and an increase in Cladocera richness was observed in May (Figure 2b). In November and February, the Sididae family dominated, particularly Diaphanosoma spinulosum Herbst, 1975 and Diaphanosoma fluviatile Hansen, 1899. Diaphanosoma fluviatile was also more frequently recorded at sites with greater water transparency. In the other sampling periods, the Chydoridae family was predominant, exhibiting higher species richness and abundance. A variation between sampling points was observed, with Cladocera showing consistently lower abundance at all points compared to Copepoda (Figure 2c), and spatial richness with variation between sampling points (Figure 2d), but without a clear pattern, as some sites had higher values while others had lower richness.

Figure 2. Seasonal and spatial variation in microcrustacean (Cladocera - blue and Copepoda - yellow) community structure in a lake marginal. A. Seasonal variation in total abundance. B. Seasonal variation in species richness. C. Spatial variation in total abundance. D. Spatial variation in species richness.

For copepod species, abundance varied over time (Figure 2a), peaking in February (wet), followed by a sharp decline in May and August, during the dry season. The most abundant species were Notodiaptomus henseni (Dahl F., 1894) and Thermocyclops decipiens Kiefer, 1929. Richness remained relatively stable over the months (Figure 2b), with a reduction from May (wet). Spatially, Copepoda abundance varied between sampling points (Figure 2c), presenting generally higher values compared to Cladocera. Richness also varied between sites (Figure 2d), with lower values at P1 and P7. Among the immature stages of copepods (nauplii and copepodites), the Cyclopoida order was dominant.

The presence of macrophytes significantly influenced the microcrustacean community, as indicated by the KW test, which showed significantly higher species richness (X 2 = 4.50, p = 0.033) and abundance (X 2 = 22.22, p < 0.00001) in samples with macrophytes in different seasons, results were confirmed by Dunn’s post-hoc test (p = 0.016 and p = 0, respectively). PERMANOVA further supported these findings, showing that macrophyte presence and sampling month together explained 60.15% of the variation in community composition (R 2 = 0.60, F = 16.097, p = 0.001), highlighting their strong structuring role.

When analysed individually by month, species richness varied significantly across the four sampled months (X 2 = 14.62, p = 0.002). Dunn’s post-hoc test confirmed significant differences between these months compared to May and November (p = 0.0001). Regarding abundance, even more pronounced differences were detected among the months (X 2 = 26.28, p < 0.00001), with peak values in August and November, both significantly higher than in May (August vs. May, p = 0.022; November vs. May, p = 0.011), and November also significantly higher than August (November vs. August, p < 0.001), suggesting a population surge particularly marked in November.

Although some fluctuations were observed across the months, overall cladocerans’ richness was higher in periods with macrophyte coverage. The abundance of copepods suffered a strong reduction during the period with macrophytes. As for cladocerans, the reduction in abundance occurred in the period without macrophytes, followed by an increase in the following collection, already with the presence of macrophyte cover, but with a new decrease observed in the last sampling.

Spatially, copepods were the most abundant group across all sampling sites, with particularly high values observed in the central and northern regions of the lake (P1 to P6). In contrast, cladocerans showed much lower and relatively uniform abundances throughout all points. Regarding species richness, both groups exhibited more spatially homogeneous values. However, cladocerans showed slightly higher richness at some central sites (P3 and P4), while copepods showed greater richness at sites P1 and P2, near the northern margin. In contrast, the southernmost sites (P7 to P9) displayed lower abundance and richness for both groups. Overall, the central portion of the lake (P3 to P5) concentrated the highest richness values. The macrophytes were uniformly present throughout the entire study area, indicating that the observed spatial differences are not directly attributable to variations in aquatic vegetation cover.

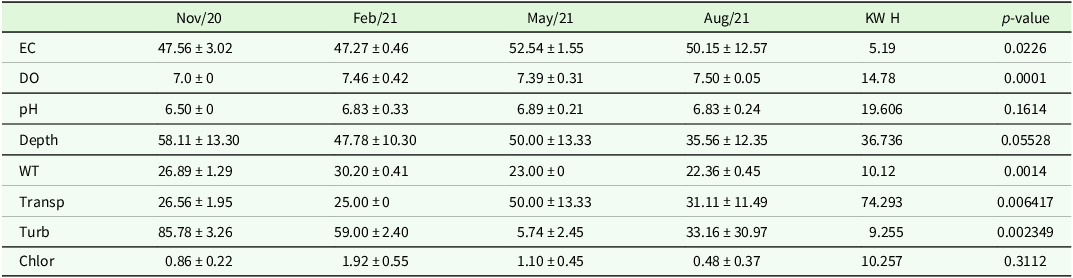

Spatial-temporal trends in environmental variables

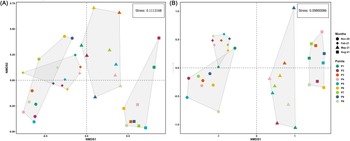

According to the PCA (Figure 3), the lake exhibited a more pronounced temporal structure than the spatial one. The first principal component (PC1) explained 33.62% of the total variation, while the second principal component (PC2) accounted for 21.33%, totalling 54.95% of the variation in the physical and chemical data. Dissolved oxygen and electrical conductivity showed strong positive loadings on the PC1, while water transparency and pH were also positioned in this quadrant but in opposition to depth and chlorophyll-a, respectively. A separation is observed, with samples from November (wet) and February (wet) clustering on one side of the plot, and those from May (dry) and August (dry) on the opposite side.

Figure 3. Biplot of PCA trends for spatial and temporal ordination of limnological variables in a lake marginal. Legend and measurement units: Cond = Electrical Conductivity (µS cm−1), DO = Dissolved Oxygen (mg L−1), pH = Hydrogen Potential, Depth = Depth (m), Temp = Water Temperature (°C), Transp = Water Transparency (cm), Turb = Turbidity (NTU), and Chlor = Chlorophyll-a (µg L−1).

Thus, the variables that most strongly contributed to the ordination axes were dissolved oxygen, electrical conductivity, water transparency, depth, and pH. For different seasons and the presence of macrophytes, it was possible to observe that the variables of turbidity, temperature and chlorophyll-a were more associated with the rainy period without macrophytes, while dissolved oxygen, electrical conductivity, pH, transparency and depth with the dry period with macrophytes.

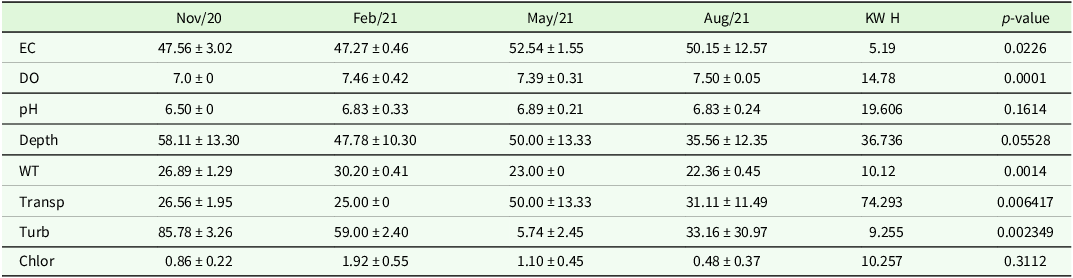

Limnological variables (Table 1) also exhibited significant differences according to the presence of macrophytes, as indicated by KW and Dunn’s post-hoc tests. Electrical conductivity was significantly higher in the presence of macrophytes (KW, p < 0.05; see Supplementary Material 2 for full test statistics). Water temperature was considerably lower in samples without macrophytes (KW, p < 0.05). Dissolved oxygen also showed highly significant differences, with higher values in the presence of macrophytes (KW, p < 0.0001). Transparency and turbidity also differed significantly between periods; transparency was higher and turbidity lower in the presence of macrophytes (KW, p < 0.01). On the other hand, pH (KW, p > 0.05), depth (KW, p > 0.05), and chlorophyll-a (KW, p > 0.05) did not show significant differences in relation to macrophyte presence.

Table 1. Mean and standard deviation of the sampling stations of the physical and chemical variables of the four collections in Lagoa das Casas, municipality of Angatuba/SP. Legend and measurement units: EC: Electrical Conductivity (µS cm−1), DO: Dissolved Oxygen (mg L−1), pH: Hydrogen Potential, Depth: Depth (cm), WT: Water Temperature (°C), Transp: Water Transparency (cm), Turb: Turbidity (NTU), Chlor: Chlorophyll-a, (µg L−1).

Relationship between environmental variables and microcrustacean community

The NMDS (Figure 4) showed a similar pattern observed in the PCA in limnological variables, revealing distinct groupings between the months also for the species. November and February (wet), which lacked macrophyte coverage, were characterised by more homogeneity, showing greater proximity between samples. In contrast, May and August (dry), when macrophyte coverage was present, showed higher variability and greater dispersion. The complete NMDS, including specific taxa per site, can be found in Supplementary Material 3.

Figure 4. NMDS plot of seasonal and spatial distribution of microcrustaceans (A) Copepoda and (B) Cladocera in a lake marginal.

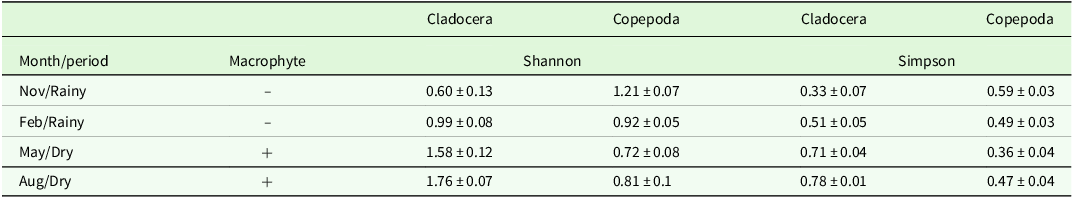

According to Table 2, in November 2020, the Shannon and Simpson index values are the lowest for Cladocera, indicating low diversity during the rainy season without macrophytes. From February 2021 onward, the values increase progressively, reaching their highest levels in August 2021, which reflects high diversity during the dry season with macrophytes. For copepods, Shannon diversity was higher during the rainy season, showing a decreasing trend in the dry period. In contrast, Simpson’s index remained relatively stable.

Table 2. Mean ± Standard error (SE) Shannon and Simpson diversity indices for Cladocera and Copepoda across rainy and dry periods (2020–2021) and presence (+) or absence (–) of macrophytes. KW test results (H and p-value) compare periods with (+macrophytes) and without (–macrophytes) aquatic macrophyte cover.

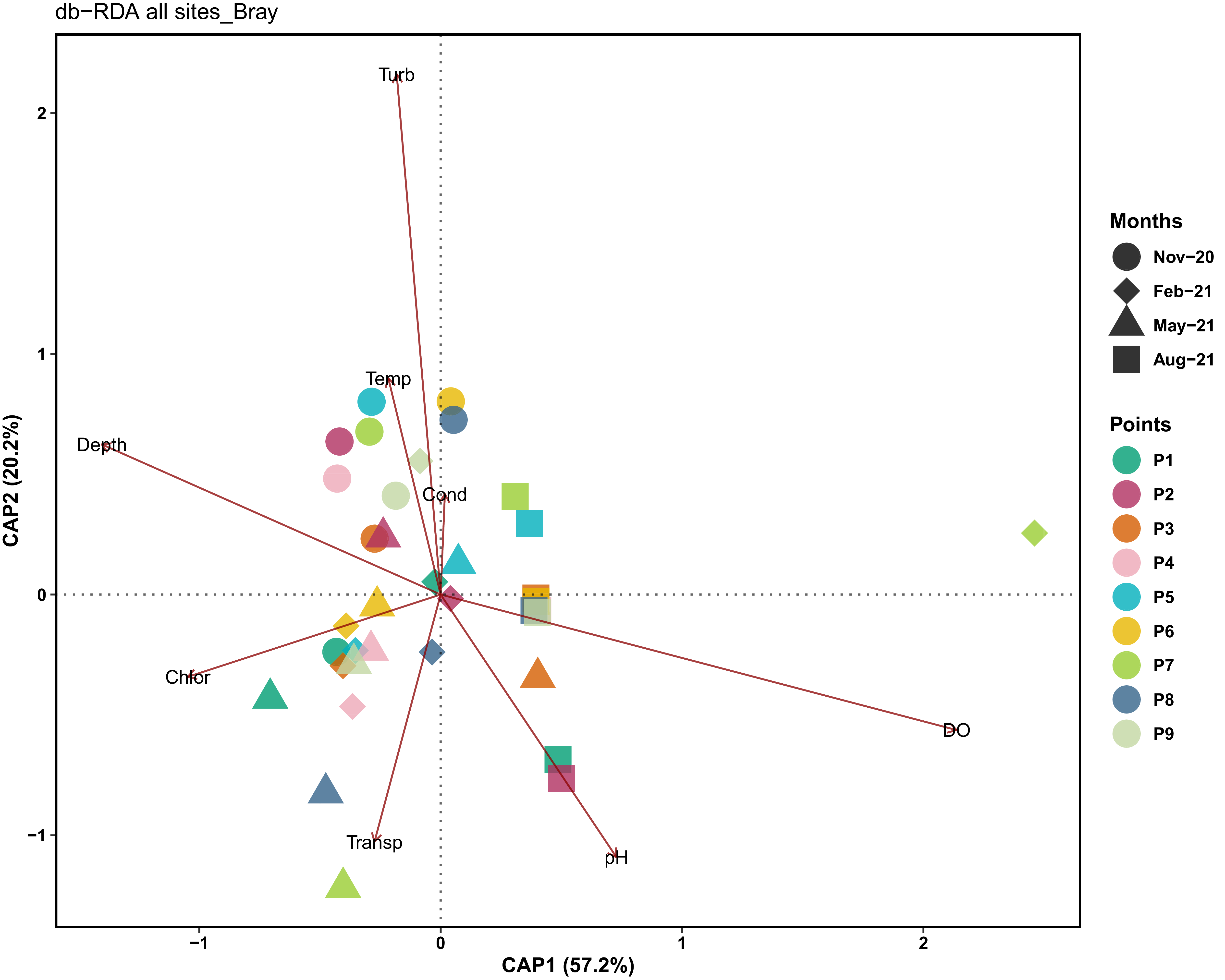

The db-RDA analysis (Figure 5) also revealed a seasonal effect of environmental variables, with turbidity, depth and dissolved oxygen being the main factors. Other variables, such as temperature, conductivity and pH, were determinant in sample differentiation over time. The first principal component (CAP1) explained 57.2% of the variation, while the second principal component (CAP2) explained 20.2%, totalling 77.4% of the variation.

Figure 5. db-RDA analysis relating the zooplankton community to limnological variables in seasonal and spatial contexts in a lake marginal. Cond = Electrical Conductivity (µS cm−1), DO = Dissolved Oxygen (mg L−1), pH = Hydrogen Potential, Depth = Depth (m), Temp = Water Temperature (°C), Transp = Water Transparency (cm), Turb = Turbidity (NTU), and Chlor = Chlorophyll-a (µg L−1).

Dissolved oxygen and conductivity were strongly correlated with the (CAP1), indicating their influence on samples positioned at this end. In contrast, turbidity and temperature were the main drivers along the (CAP2). An inverse relationship was observed between depth and water transparency was also observed as was the PCA, with greater depths associated with lower transparency and pH values.

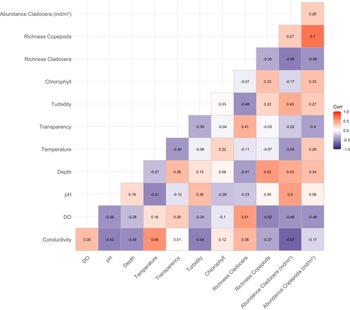

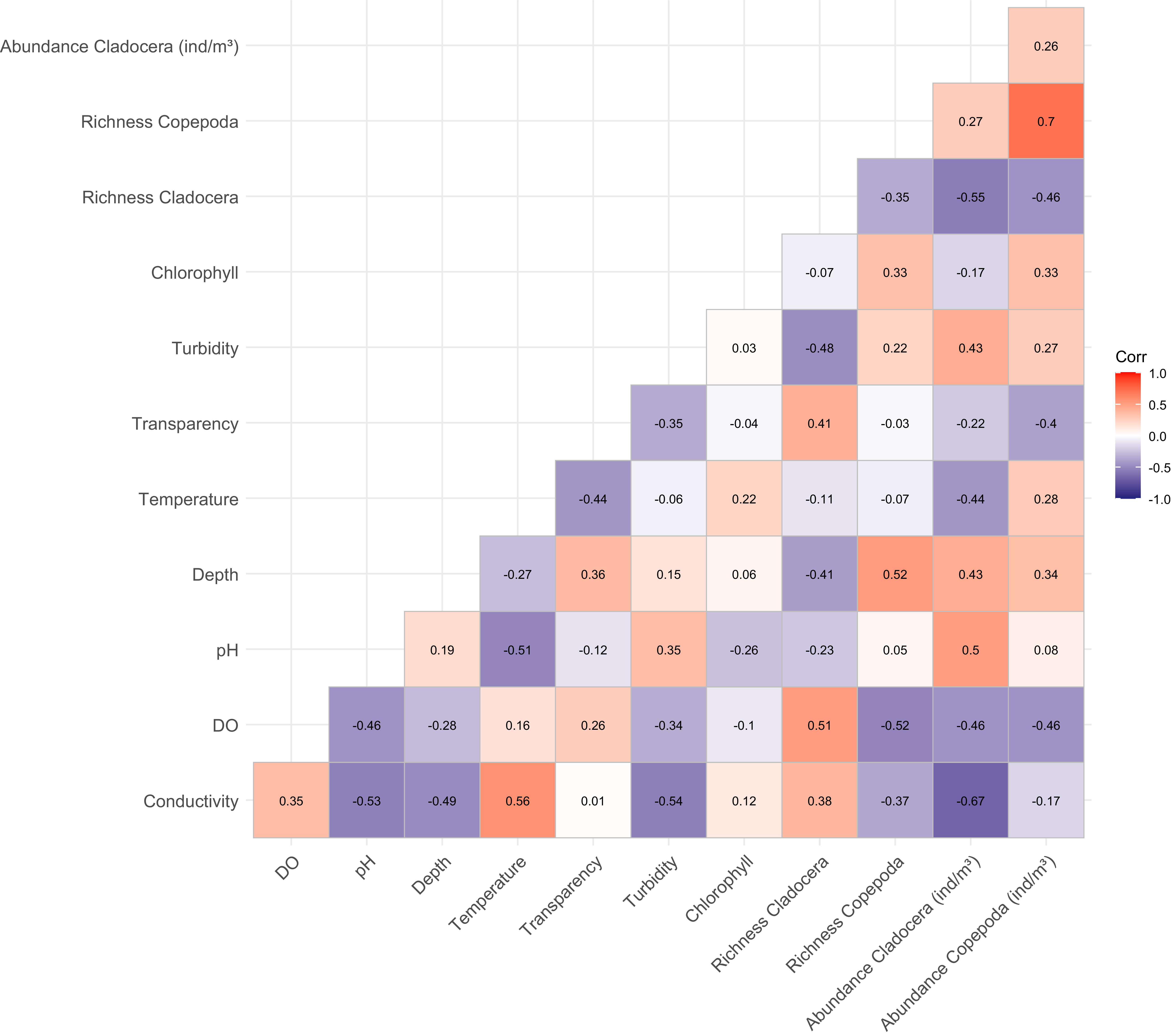

The correlation matrix (Figure 6) showed that conductivity was positively correlated with temperature (r = 0.56) and negatively correlated with Cladocera abundance (r = −0.67). Dissolved oxygen was negatively correlated with both abundances (r = −0.46). Depth showed contrasting relationships with abundance, being negatively correlated with Cladocera abundance (r = −0.41), but positively correlated with Copepoda abundance (r = 0.52). Transparency was positively correlated with Cladocera richness (r = 0.41), but showed a weak negative correlation with Copepoda richness (r = −0.03). A strong positive correlation was found between copepod richness and cladoceran abundance (r = 0.70), and cladoceran richness was also positively correlated with their abundance (r = 0.55). Finally, chlorophyll-a showed weak correlations with all biological variables.

Figure 6. Pearson correlation matrix relationships between environmental variables and microcrustacean community metrics (abundance and richness) in a lake marginal.

Discussion

Influence of environmental variables on microcrustacean community

The results obtained in this study show that the temporal structuring of the microcrustacean community in the tropical lake studied was more pronounced than the spatial structuring, probably because the small size and depth of the environment promote spatial homogeneity, reducing local environmental gradients and, consequently, spatial variation in community composition. Multivariate analyses showed a clear separation between the dry periods with macrophyte cover and the rainy period without such cover for both limnological variables and species structure. This seasonal pattern is characteristic of tropical environments, where variations directly affect limnological conditions (Kondowe et al., Reference Kondowe, Masese, Raburu, Singini, Sitati and Walumona2022), such as temperature, nutrient availability, and macrophyte coverage, which in turn drive pronounced temporal variation in species composition and abundance.

The limnological variables most strongly associated with community structuring were dissolved oxygen, electrical conductivity, turbidity, and depth. Electrical conductivity showed significantly higher values in samples during the dry season and macrophytes, possibly related to the concentration of low water level, continuous sewage input that favours the macrophytes increase, and the release of ions by the decomposition of biomass (Bottino, Cunha-Santino, and Bianchini, Reference Bottino, Cunha-Santino and Bianchini2016). The correlation matrix revealed a negative correlation between conductivity and abundance of Cladocera, suggesting that ionic changes may affect microcrustacean groups differently (Ermolaeva and Fetter, Reference Ermolaeva and Fetter2021). This pattern is also supported by Matsumura-Tundisi and Tundisi (Reference Matsumura-Tundisi and Galizia Tundisi2003), where fluctuations in water electrical conductivity were found to significantly affect the composition of calanoid copepod species. Dissolved oxygen also showed highly significant differences, with higher values in the presence of macrophytes, attributable to the photosynthesis of aquatic vegetation (Desmet et al., Reference Desmet, Van Belleghem, Seuntjens, Bouma, Buis and Meire2011).

Cladocerans showed greater richness in periods with vegetation cover, especially in May (dry season), which aligns with the understanding that structural complexity provided by macrophytes creates heterogeneous habitats (Ferreiro et al., Reference Ferreiro, Feijoó, Giorgi and Leggieri2011; Thomaz et al., Reference Thomaz, Dibble, Evangelista, Higuti and Bini2008). Considering that some species tend to have greater biomass during this season (Meng et al., Reference Meng, Yu, Xia, Zhang, Ma and Yu2023), likely benefiting from the structural complexity provided by macrophytes (Thomaz et al., Reference Thomaz, Dibble, Evangelista, Higuti and Bini2008; Meerhoff and de los Ángeles González-Sagrario, Reference Meerhoff and de los Ángeles González-Sagrario2022). In contrast, copepods showed lower richness in vegetated periods, likely due to their preference for open water habitats, mainly for Calanoida order (Geraldes and Boavida Reference Geraldes and Boavida2004). This highlights how habitat complexity, especially structures associated with the presence or absence of macrophytes, influences niche differentiation within microcrustacean communities, determining which taxa dominate each microhabitat (Debastiani-Júnior et al., Reference Debastiani-Júnior, Elmoor-Loureiro and Nogueira2016).

Our results indicate high and low abundances of cladocerans in the rainy and dry seasons, respectively. This seasonal taxonomic alternation suggests specific adaptations to fluctuating environmental conditions, as also observed by Ji et al. (Reference Ji, Havens, Beaver and Fulton2017) in studies in Florida, where similar fluctuations in biomass were associated with the negative effects of cyanobacterial blooms and omnivorous fish presence, during the dry period. Other studies have also observed this pattern of greater abundance during the rainy season in tropical and subtropical ecosystems (Okogwu, Reference Okogwu2010; Silva et al., Reference Silva, Barbosa, Medeiros, Rocha, Lucena-Filho and Silva2009).

The analysis of alpha diversity indices revealed divergent patterns between the groups. For Cladocera, the Shannon and Simpson indices showed minimum values in November (rainy season without macrophytes), increasing progressively until August, indicating greater diversity during the dry season with macrophytes, due to the increased habitat complexity and availability of refuge and food resources provided by macrophytes, which may support a more diverse community (Thomaz et al., Reference Thomaz, Dibble, Evangelista, Higuti and Bini2008). In contrast, Copepoda exhibited greater Shannon diversity during the rainy season, with a decreasing trend in the dry period, while the Simpson index remained relatively stable. This differential dynamic reinforces the importance of considering the specific taxonomic composition in ecological studies, since each group responds differently to environmental variations (Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Kelso and Rutherford1998; Galir Balkić and Ternjej Reference Galir Balkić and Ternjej2018; Perbiche-Neves et al., Reference Perbiche-Neves, Saito, Simões, Debastiani-Júnior, Naliato and Nogueira2019).

The significant reduction in copepod abundance during the period with macrophytes may be related to their pelagic lifestyle, since pelagic copepods may be more abundant outside vegetated areas (Geraldes and Boavida, Reference Geraldes and Boavida2004), as more mobile species tend to be less influenced or even negatively affected by structurally complex environments, which can restrict their movement (Lucena-Moya and Duggan, Reference Lucena-Moya and Duggan2011) or their feeding habits may have been affected (Stephan et al., Reference Stephan, Beisner, Oliveira and Castilho-Noll2019). In contrast, cladocerans demonstrated a reduction in abundance in periods without vegetation cover, followed by an increase in subsequent sampling with the presence of macrophytes, highlighting their preference for more heterogeneous habitats (Genaro et al., Reference Di Genaro, Sendacz, Moraes and Mercante2015; Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Elmoor-Loureiro, Mendonça-Galvão and Simões2025). These results corroborate previous studies that identified that vegetated environments favour the increase of richness and diversity of organisms (Crowder, McCollum, and Martin, Reference Crowder, McCollum, Martin, Jeppesen, Søndergaard, Søndergaard and Christoffersen1998) as well as the zooplankton community in general (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Jeong, Kim, La, Chang and Joo2014; Mimouni et al., Reference Mimouni, Pinel-Alloul, Beisner and Legendre2018; Razak and Sharip, Reference Razak and Sharip2019).

The consistent dominance of the order Cyclopoida among the immature stages of copepods (nauplii and copepodites), even with seasonal fluctuations, suggests a resilience of this group in the face of environmental changes, likely supported by their short generation time and high reproductive capacity (Wyngaard et al., Reference Wyngaard, Taylor and Mahoney1991). This stability may be related to the supply of food resources, high productivity, and nutrient availability, as suggested by Perbiche-Neves et al. (Reference Perbiche-Neves, Saito, Previattelli, da Rocha and Nogueira2016, Reference Perbiche-Neves, Pomari, Serafim-Júnior and Nogueira2021). It is noteworthy that, despite the different external factors (drought and macrophyte blooms), the young stages of copepods maintained stable distribution patterns.

The spatial distribution of the community in all months, although less structured than the temporal one, also showed significant variations between the sampling points for both groups, without a clearly defined pattern. This suggests that local factors, such as the heterogeneous distribution of macrophytes, can modify different types of environments (Gantes and Caro, Reference Gantes and Caro2001). Havens et al. (Reference Havens, Fulton, Beaver, Samples and Colee2016) highlight that in shallow lakes, precipitation and runoff can significantly impact zooplankton communities and potentially alter the entire local biodiversity, contributing to this spatial heterogeneity (Simões et al., Reference Simões, Dias, Meerhoff, Lansac-Tôha, Bini and Bonecker2022).

Influence of macrophyte cover on microcrustacean community

The presence of aquatic macrophytes occurred as a crucial and structuring factor for the community, as confirmed by the KW statistical tests and PERMANOVA analysis.

The positive correlation found between copepod richness and cladoceran abundance suggests a possible relationship between these groups. One possibility is that diversification of one group may favour the establishment of populations of the other (Sommer et al., Reference Sommer, Sommer, Santer, Jamieson, Boersma, Becker and Hansen2001; Sommer and Sommer, Reference Sommer and Sommer2006), potentially due to niche complementarity or the structuring of more. Alternatively, both groups may respond similarly to favourable environmental conditions, without a direct ecological interaction.

Our results partially support the expectation that microcrustacean richness increases during the rainy season. This pattern was evident for Copepoda, whose richness peaked in the rainy period (February 2021), whereas Cladocera showed higher richness during the dry season (May 2021), coinciding with the presence of macrophytes.

In contrast, for the other expectation, Cladocera richness was indeed higher in the presence of macrophytes, although its abundance declined. For Copepoda, both richness and abundance decreased in macrophyte-covered habitats, suggesting that macrophyte presence may have variable responses in microcrustacean communities and that group-specific responses are important to consider.

These contrasts between Cladocera and Copepoda may reflect their marked differences in life history strategies and ecological preferences. The higher richness of Cladocera during the dry period, especially in macrophyte-rich areas, may be related to their preference for structured habitats that provide refuge from predators and access to suspended food particles (Castilho-Noll et al., Reference Castilho-Noll, Câmara, Chicone and Shibata2010). Their short life cycles (Cortez-Silva et al., Reference Cortez-Silva, Souza, Santos and Eskinazi-Sant’Anna2022) and high colonisation ability (Louette and De Meester, Reference Louette and De Meester2005) favours the coexistence of multiple species in stable and heterogeneous environments. In contrast, the greater abundance of Copepoda during the rainy period and in areas without macrophytes may reflect their higher mobility and preference for open habitats, as well as increased food availability, since phytoplankton can also increase during the rainy season (Silva and Jati, Reference Silva and Jati2024). This differentiation provides a clear context for understanding how environmental variability structures tropical lake communities. Our findings reinforce the idea that seasonality and habitat heterogeneity act as ecological filters that determine the dynamics of biodiversity in tropical lakes, shaping the structure of the community over time (Astorga et al., Reference Astorga, Death, Death, Paavola, Chakraborty and Muotka2014; Tonkin et al., Reference Tonkin, Bogan, Bonada, Rios-Touma and Lytle2017). NMDS demonstrated that periods without macrophyte cover (November and February) presented more homogeneous groupings among the samples, while periods with macrophytes (May and August) exhibited greater variability and dispersion, highlighting the role of aquatic vegetation in niche diversification (Thomaz and Cunha, Reference Thomaz and da Cunha2010; Vejříková et al., Reference Vejříková, Eloranta, Vejřík, Šmejkal, Čech, Sajdlová, Frouzová, Kiljunen and Peterka2017).

Finally, the results highlight the ecological importance of macrophytes as zones of high local biodiversity and their potential function as refuge and reproduction areas for microcrustaceans, particularly cladocerans. The conservation of these ecosystems must therefore consider the maintenance of aquatic vegetation and recognise seasonality as a fundamental structuring element, since these factors directly influence the diversity, composition and functionality of tropical continental aquatic ecosystems. Therefore, management should protect macrophyte areas, maintain natural flood cycles, limit vegetation removal, and include these zones in monitoring programmes. Seasonal dynamics must be incorporated, as they are key to balancing ecosystem processes and community structure.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467425100370

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to Dr. Francisco Diogo Rocha Sousa for verifying some cladoceran species and to Prof. Raoul Henry for his special contribution during the campaigns and for his valuable suggestions in the text and to Hamilton Rodrigues for his help during some campaigns.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) (C.M.S., grant number 125476/2020-5) and the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) (C.M.S., grant number 2020/08071-8) for the scholarship of the first author; and by CNPq PQ (G.P.N., grant number 305295/2025-0).

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.