When a group of Soviet opera singers arrived in the railway town of Harbin, Manchuria, in September 1927, diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union and the Republic of China (RoC) had reached an all-time low. Zhang Zuolin, the self-proclaimed Warlord of Manchuria,Footnote 1 had rekindled tensions over the Chinese Eastern Railway (CER), a key transportation infrastructure that cut through the middle of the contested region. At stake was the practice of extraterritoriality in the settlements of the railway exclusion zone, which, much like the Shanghai International Settlement, exempted foreigners from the jurisdiction of local Chinese law and impinged on the sovereignty of the RoC.Footnote 2 Though the Soviet government had officially agreed to suspend its extraterritorial privileges, it continued to exert undue authority in the region and Warlord Zhang began to retaliate with violence. Five months before the opera tour began, he helped orchestrate a brutal raid on the Soviet embassy in Beijing, which resulted in the arrest and torture of Soviet diplomats.Footnote 3 Just as top Soviet officials were fleeing the RoC, the opera singers entered the zone of conflict.Footnote 4 Tensions intensified throughout the tour, punctuated by the assassination of Warlord Zhang in June 1928.Footnote 5 The Soviet opera singers remained in Manchuria until mid-February 1929, shortly before 300,000 Soviet and Chinese soldiers flooded the border and a full-scale military clash erupted, killing several thousand people.Footnote 6

In the context of intense political violence preceding the Sino-Soviet War of 1929, it is tempting to view the Soviet opera tour to Manchuria as little more than a musical propaganda campaign. The group provocatively called themselves ‘the Soviet Opera of the Chinese Eastern Railway’, as if to stake a claim for Soviet authority over the railway line.Footnote 7 Seeing this title printed on posters, programmes tickets – even repeating it out loud in conversation – forced the public to acknowledge a direct connection between the Soviet government and the railway. Performances took place at the Railway Assembly Hall (Zhelsob), a venue rooted in the history of Russian colonialism and extraterritorial exploitation in Manchuria. The troupe received funding for the trip from the All-Union Trade Union of Arts Workers (RABIS), and permission for the tour hinged on the prospect of spreading Soviet sympathies in the region.Footnote 8 Considering these factors, it is all too easy to pigeonhole the touring opera singers as dutiful agents of the Soviet state, mobilised in a textbook example of early Soviet ‘soft power’ on the border with the RoC.Footnote 9

Recent scholarship has set a precedent for examining Soviet musical performance as an instrument of state power, especially in the realm of cultural diplomacy.Footnote 10 It is important to remember, however, that the opera tour to Manchuria was arranged well before the standardisation of Soviet cultural diplomacy efforts. As the historian Michael David-Fox has shown, the All-Union Society for Cultural Ties Abroad (VOKS) harboured several ‘conflicting impulses’ in its early cultural diplomacy efforts in the late 1920s.Footnote 11 Only later during the Cold War did policies coalesce around the aim and means of Soviet musical participation in international competitions, exhibitions and other cultural exchanges.Footnote 12 The Soviet opera tour to Manchuria occurred amidst several monumental transitions in the Soviet Union: the establishment of ‘socialism in one country’, the end of the New Economic Policy, the implementation of the first Five Year Plan and the birth of Glaviskusstvo, the centralised organ for arts administration in the USSR.Footnote 13 Amidst these changes, the Soviet opera tour appeared somewhat disorganised, representing less a carefully crafted political manoeuvre than an ad hoc response to the railway crisis.

Several aspects of the opera tour resist framing as a mere projection of Soviet power. The musical works on display aligned more with the upper-class tastes of local audiences than they did with Sovietised artistic trends in Moscow or Leningrad.Footnote 14 Throughout their time in Harbin, the touring Soviet singers constantly rubbed shoulders and formed meaningful relationships with their supposed ideological adversaries: White Russian émigrés with monarchist convictions and Chinese workers who implemented Warlord Zhang’s hostile policies. These alleged foes staffed the venue where the visiting Soviet artists sang, designed their props and costumes, and provided musical accompaniment for them in the symphony and choir. The Soviet opera singers were fraternising – even harmonising – with the enemy. When the American record label Victor Talking Machine sent recording scouts to Harbin, this musical collusion was permanently inscribed in the shellac grooves of dozens of 78 rpm recordings. By the end of the tour, Russian émigrés in the city adopted the visiting vocalists to be a part of the local community – not representatives of the Soviet government, but Kharbintsy (Harbinites), despite having travelled to the region as part of a Soviet state-sponsored campaign.Footnote 15

How the travelling Soviet opera singers experienced the tour and understood themselves in relation to it – whether as extraterritorial agents, complicit propagandists, open-minded collaborators or assimilated converts of Harbin’s émigré community – cannot fully be answered with the language of Soviet statecraft alone. Neither can their actions be explained within the general framework of ‘railway imperialism’, which has influenced recent scholarship on the history of Manchuria.Footnote 16 These top-down perspectives risk effacing personal agency by attributing power to abstract systems like governments and infrastructures, while neglecting the localised spaces where power was embodied and negotiated by individual actors. To zoom in and reimagine the opera stage as a site where power relations and identities crystallised, enables a more flexible understanding of musicians as political subjects and how music intervened in an international crisis.

This article examines the seemingly contradictory politics of the tour of the Soviet Opera of the Chinese Eastern Railway, paying close attention to moments that apparently defied the logic of the ongoing conflict. Drawing on memoirs and other firsthand accounts of the tour, alongside reports from the local Harbin and All-Union Soviet press, I show how the interpersonal relationships that formed during the tour temporarily shifted focus away from the strained political atmosphere in Manchuria. The experiences of the touring musicians and audience members illustrate how operatic performance served as a site for negotiating ideology and identity in the Sino-Soviet border zone. Against the backdrop of antagonistic rhetoric that instigated the tour, I contend that the Harbin opera stage functioned as an unregulated space of informal extraterritoriality, where unpredictable and meaningful collaborations took place. This is not to say that the shows performed by the Soviet opera troupe were somehow removed from the fraught political landscape of Manchuria in the late 1920s – rather, that the tour cannot be reduced to a stable set of political relations.

I should stress that the Soviet opera tour to Manchuria ultimately did little to alleviate the ongoing crisis; a brutal war began in the immediate aftermath of the singers’ departure from Harbin. This is not a utopian tale of the power of music to cross insurmountable social divides or remedy political rivalries. Nor is it an example of musicians acting in defiance of their government or resisting state control. Rather, it is an attempt to tune into early Soviet opera on the move, to elucidate its spatial and affective registers, namely in the contexts of extraterritoriality and armed conflict in Manchuria. This is an exploration of how the experience and memory of musical performances rattles already unstable notions of wartime propaganda, diplomacy and state ideology. It is a call to take seriously the cultural excess of armed conflict and contested borders, and to interrogate the real experience of musicians who have acted in service of state-sponsored initiatives.

What follows is a critical assessment of the tour of the Soviet opera of the Chinese Eastern Railway from multiple methodological angles, beginning with a discussion of the colonial legacy of Russian extraterritoriality and the Railway Assembly Hall, the venue where the troupe performed. Next, I turn to contemporaneous accounts of the tour, probing issues of funding and recruitment, musical programming and cross-cultural collaboration, and the violent dissolution of the tour. These perspectives are then contrasted with personal accounts of the tour, delving into the politics of remembering and publishing about the performances, and the globally distributed media afterlives of the recordings made during the tour. I conclude with a reappraisal of the agency and intentionality of Soviet musicians on the opera stage and the thorny ethical concerns of studying musicians in politically volatile regions.

Russian extraterritoriality and the Railway Assembly Hall (Zhelsob)

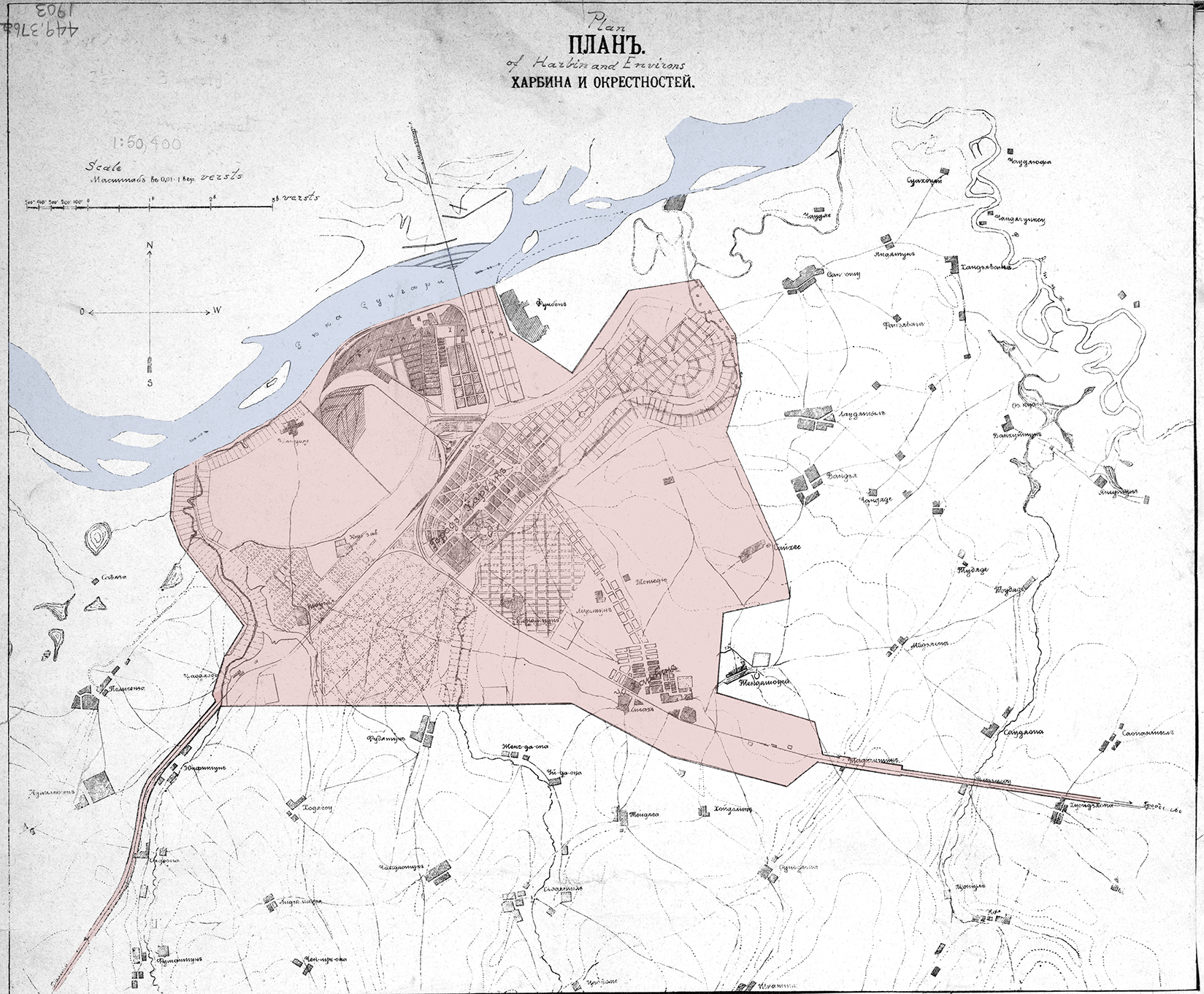

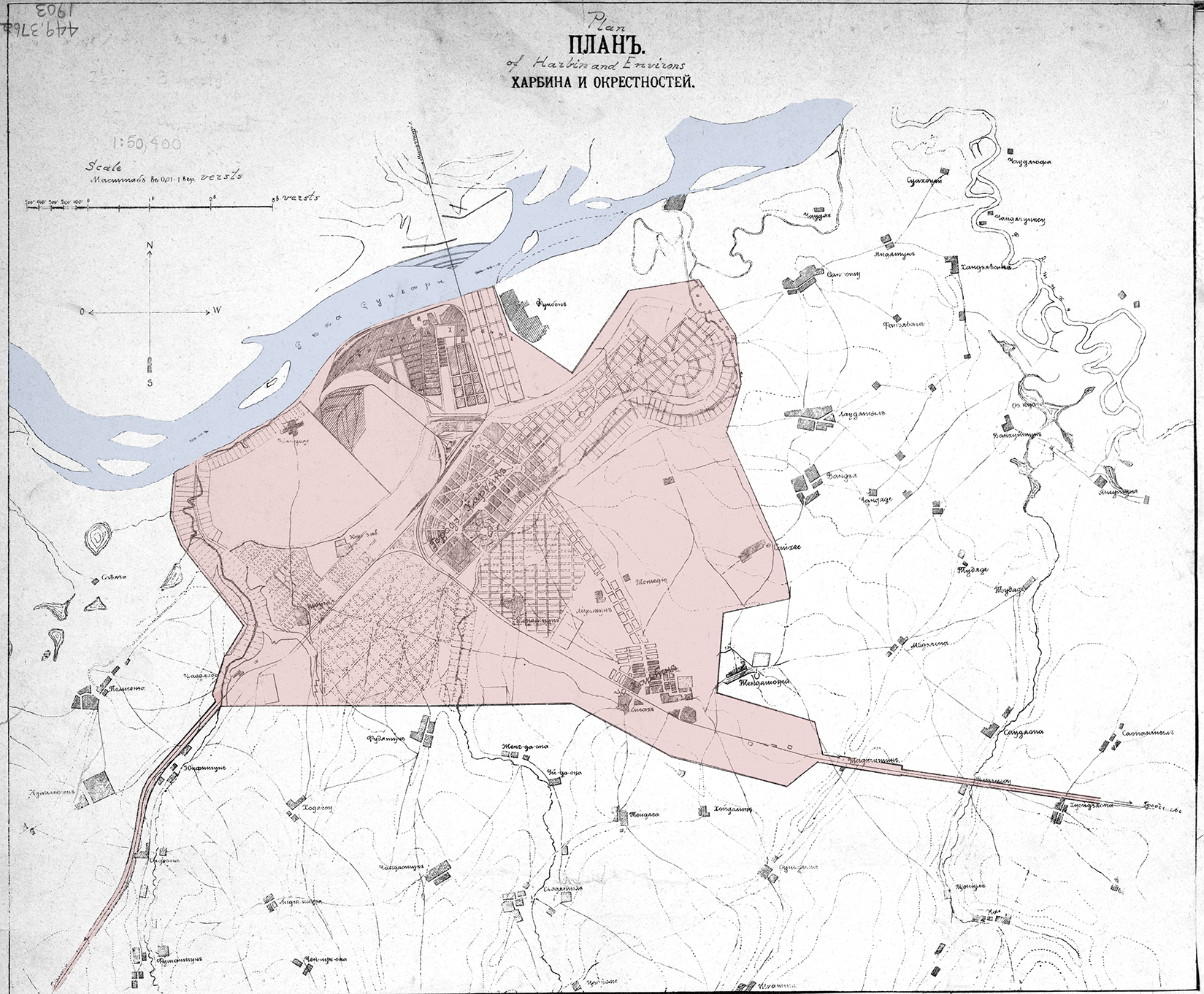

The Soviet claim to extraterritorial authority in the RoC derived from the colonial projects of the Russian Empire in Manchuria at the turn of the twentieth century. Through a series of unequal treaties signed by Chinese Grand Secretary Li Hong Zhang, Russian Imperial Finance Minister Sergei Witte secured permission to build the eastern extension of the Trans-Siberian Railway through the middle of Qing territory, called the Chinese Eastern Railway (CER).Footnote 17 Though it primarily concerned the construction of the railway, the treaty effectively conferred a legal basis for Russian settler colonialism in Manchuria. Russian imperial authorities received full administrative control over the railway exclusion zone, which consisted of a strip of land 220 feet wide around the tracks and jutted outward at railway stations (Figure 1).Footnote 18 The main railway line opened in 1903 and major stations like Harbin rapidly grew into frontier towns and cities, where settlers from the Russian Empire exercised full extraterritorial privileges.Footnote 19

Figure 1. Map of the Railway Exclusion Zone in Harbin (in red), bounded to the north by the Sungari River (in blue), c.1903. Colour overlay added by author. Adapted from the inset of ‘Plan Kharbina i okrestnostei: v predielakh polosy otchuzhdeniya Kitaiskoy vostochnoy zhelieznoy dorogi’. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, G7824.H3G46 1903. C4.

As a legal practice, extraterritoriality grants immunity from the jurisdiction of a state within its own territorial bounds.Footnote 20 These privileges have often been enjoyed by diplomats and by foreign nationals within the premises of consular missions and within certain territorial concessions. Scholars have shown that in both the Qing Dynasty and the RoC extraterritoriality functioned as a colonial formation – a practice that some have claimed instituted ‘a greater intensity of oppression and greater neglect than a formal colony’.Footnote 21 The CER exclusion zone was in large part administered by Russian imperial subjects, who acted on the authority of the Russian Empire. The railway catalysed Russian commercial activity throughout the surrounding region of the ‘Russian Far East’ (Дальний восток) – itself a territory that had been annexed from the Chinese Empire half a century earlier.Footnote 22 Over the following two decades, northern Manchuria grew into a bustling Russian colonial dependency that was gradually incorporated into Tsar Nicholas II’s domain.Footnote 23 A wide range of ethnic groups from across the Russian Empire migrated to the railway settlements of the exclusion zone in search of lucrative economic prospects.Footnote 24

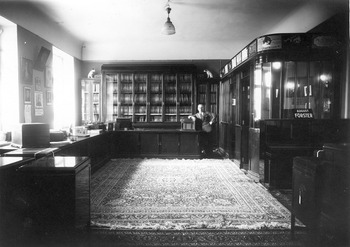

From the very beginning, the musical life of Harbin was tied to the CER. Every musician and concert-goer, musical instrument and gramophone passed through Harbin Station, located in the centre of New Town. The most important concerts and events took place in the auditorium of the Railway Assembly Hall – Zheleznodorozhnoye sobranie, or Zhelsob for short (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Railway Assembly Hall (Zhelsob) in Harbin, 1929. Photograph by Vladimir Pavlovich Ablamskii. World Digital Library Collection, Library of Congress, no. 2018687658. Original image at Irkutsk Municipal History Museum.

Following Suzanne Aspden, we might consider how the Zhelsob operated as a forum for the performance of Russian imperial power in Manchuria – not simply a ‘mere receptacle for operatic events’ but an active ‘participant in negotiations of (urban) territory’.Footnote 25 Established as a recreation space for railway workers in 1899 (the year following the founding of the town of Harbin itself), the Zhelsob grew with the arrival of Russian engineers, settlers and merchants to northern Manchuria. Many of the first amateur musical performances took place at its original location in Old Town – years before regular passenger service on the railway began and Harbin’s grand boulevards were built.Footnote 26 As the population of the city swelled, the Zhelsob relocated closer to the Railway Station in New Town and eventually settled in a grand neoclassical building across the street from the railway administration in 1911 (Figure 2).Footnote 27 The musical programming at the hall upheld the cultural standards of the Russian imperial aristocracy, largely comprising operas, symphonies and ballets from the Russian and European canon. Until the Russian Revolution, the Zhelsob not only symbolised Russian imperial hegemony, but also became its cultural mouthpiece – a space where extraterritorial privilege was made manifest on stage.

Amidst the chaos of the Russian Civil War in 1920, Chinese presidential decrees ceased recognition of the Russian government, re-established control over the CER and, most importantly, abolished Russian extraterritoriality in the region.Footnote 28 Current Russian residents in Harbin suddenly found themselves subject to Chinese law – effectively becoming accidental émigrés cut off from their homeland by a new border thrust upon them.Footnote 29 Even without the authority they once had, an additional 100,000 former Russian imperial subjects crossed the border and resettled in Manchuria during the conflict.Footnote 30 The newly formed Bolshevik government immediately advocated for its railway inheritance, while attempting to distance itself from the exploitative practices of the imperial Russian government.Footnote 31 It would take four years, however, for the Soviets to resume any semblance of authority over the railway.

Throughout the political upheaval of the early 1920s, the Zhelsob developed into a nexus of Russian émigré activity. As tens of thousands of former Russian imperial subjects poured across the Chinese border, they found refuge in the grand hall. For many, the Zhelsob represented the survival of Russian imperial culture against the backdrop of Bolshevik destruction. Olga Koreneva, a pianist born in Harbin, warmly remembered all the amenities that the building had to offer:

The auditorium could accommodate 1200 peopleFootnote 32 and had excellent acoustics. The stage was excellently equipped; there were comfortable rooms for the actors to change clothes and apply makeup; there were rich wardrobes and a music library. In addition to the auditorium, there were two huge foyers for the public, where you could sit in comfortable chairs during the intermission, talk, and smoke. There was also a restaurant, where you could stay for dinner and drink tea or coffee.

The entire premises were luxuriously decorated: stucco ceilings, beautiful sconces on the walls, crystal chandeliers, panels of beautiful wood, burgundy velvet curtains with gold accents; paintings by famous artists hung on the walls in the foyer. The public always came elegantly dressed.Footnote 33

Looking back on the hall several decades later, she declared ‘we can proudly say that our Zhelsob could have been the crowning jewel of any capital city’.Footnote 34

Many residents shared Koreneva’s fondness for the Railway Hall. For the violinist Georgiy Sidorov, the Zhelsob represented a ‘nursery for musical culture’ (питомник музыкальной культуры), where he regularly listened to concerts and developed his musical taste.Footnote 35 In a similar vein, Georgiy Melikhov recalled running to catch the opera rehearsals during his lunch break between classes in the early 1920s:

At the Polytechnic Institute there was a long break at about 12 noon (between the 3rd and 4th lectures). Having eaten quickly, I would hurry to the Railway Assembly Hall for the opera singers’ rehearsals. The Zhelsob was two blocks away from the Institute, and I managed to spend 15–20 minutes at the rehearsal. I was already well known at the Assembly and was allowed to attend the rehearsal without hindrance. I watched, listened, and sometimes talked with the choristers, a few of whom I got to know well. Incidentally, it should be said that the opera choir of 40 people consisted of very experienced singers, if not full professionals, who were well acquainted with music, having sung for many years in Harbin’s church choirs.Footnote 36

For many living in Harbin, visiting the Zhelsob was a core part of their weekly, if not daily routine. Tickets for the symphony, the opera and foxtrot dances were not expensive, and railway workers could purchase a season pass at a significantly discounted rate of up to 75%.Footnote 37

Though local ensembles filled much of the hall’s schedule, the Zhelsob was perhaps best known for the visiting musicians who performed on its stage in the 1920s. Recalling the many musical tours that passed through the hall, the pianist Natalia Stal’nova wrote: ‘The cultural life in Harbin was rich, but somehow connected more with touring Russian performers.’Footnote 38 The renowned violinists Mischa Elman and Jascha Heifetz (both Jewish performers who were claimed as part of the greater Russian diaspora) drew massive audiences to their concerts at the Zhelsob during the summer 1921 and winter 1923 seasons respectively.Footnote 39 These tours and others helped position Harbin as part of a larger, global Russian diaspora that emerged in the wake of the Russian Revolution.

At the same time that Harbin developed as a centre for Russian emigration, it became the target of Soviet intervention. The Soviet authorities managed to broker a provisional agreement for the joint operation of the CER on 31 May 1924 in Beijing, which coincided with the diplomatic recognition of the USSR by the RoC.Footnote 40 Though the agreement promised to split management of the railway equally, the railway board heavily favoured the Soviet side – stacked as it was with Soviet representatives and Chinese workers sympathetic to the USSR.Footnote 41 In effect, the Soviet Union managed to denounce the practice of extraterritoriality in public, while retaining the same rights and privileges that such a practice afforded.Footnote 42 The aggressive Soviet claim to the railway was ultimately a reflection of the very imperial logics of territorial expansion that communist ideology officially renounced. I am adopting the phrase ‘informal extraterritoriality’ to describe how the Soviet government attempted to encroach upon the CER and impose its preferred cultural values in Harbin while maintaining the pretence of sincere collaboration with the Chinese government. As tensions built over the railway throughout the late 1920s, the Soviet government doubled down on their neocolonial project in the RoC, ostensibly disregarding the core principle of Stalin’s policy of ‘socialism in one country’.Footnote 43

In an attempt to absolve itself for its stubborn imperialist impulses, official Soviet discourse portrayed the ensuing conflict over the railway as one of ‘defending the border’ (защита границ) and enforcing the terms of the 1924 Beijing Agreement.Footnote 44 This vague political stance reflected an emergent, distinctly Soviet image of Manchuria, which began to reconceptualise the railway and the settlements along it as the very border itself.Footnote 45 The border needed to be policed and reaffirmed in moments of contention, but it was also a porous boundary where musical performance – and the opera stage of the Zhelsob in particular – became a site of unscripted encounter between distinct social groups. Importantly, the lack of clearly defined policies and strict oversight that had enabled the Soviet project in Manchuria in the first place limited its efficacy. The Soviet musicians who were sent to live and work in Harbin largely practised informal extraterritoriality on their own terms.

The Beijing Agreement effectively created a loophole for Soviet citizens to legally work within the former imperial railway exclusion zone. As a result, the Zhelsob became an attractive destination for Soviet musicians, an autonomous space partially removed from the watchful gaze of the All-Union Trade Union of Arts Workers (RABIS) and the Manchurian authorities. Dozens of touring Soviet artists began to make the trek to Harbin in the mid-1920s and the legal ambiguity of their tours became an administrative headache for the Soviet authorities. Some visiting Soviet artists only stayed in Harbin for a few days; others lingered for months or decided never to return to the USSR, effectively emigrating from the country.Footnote 46

To combat this problem, RABIS began to deny permission for artists based outside the Far Eastern provinces to travel to Harbin.Footnote 47 Nevertheless, the local Soviet authorities allowed musicians to regularly cross into Manchuria on the pretext of ‘combating unemployment’.Footnote 48 RABIS even opened an office in Harbin, though many touring artists failed to register at the office upon arrival in the city.Footnote 49 Miscommunication from the Harbin authorities regarding Soviet musical tours caused several scandals.Footnote 50 In late spring 1926, RABIS introduced a ‘passport tax’ to cross the border and new customs regulations, which began to stifle the laissez-faire atmosphere.Footnote 51 To avoid the fee, some Soviet musicians began to cross the Chinese border illegally.Footnote 52 As geopolitical tensions began to rise in March 1927, the central office of RABIS in Moscow (TsentroPoSredRABIS) instituted strict requirements for artists to enter the border zone.Footnote 53 Soviet extraterritoriality in Manchuria – even enacted on an informal level – would subsequently be subject to official approval.

‘A fertile bud for Soviet art’: arranging the Soviet opera tour to Harbin

The Soviet Opera of the Chinese Eastern Railway was one of the first officially sanctioned ensembles to perform in Harbin following the 1927 restrictions, and this designation came with increased state support. The central RABIS office reportedly provided a sum of over 200,000 rubles for their performances at the Zhelsob – an exceptionally large amount, which could easily fund several months of a theatrical season with top-notch performers, including custom-made sets and costumes, a 40-person choir, a 36-person string orchestra and sixteen ballet dancers.Footnote 54 Another source listed the even greater budget of 300,000 dollars.Footnote 55 Regardless of the exact amount, it is clear that RABIS thought the opera tour to be an important investment. ‘A budget was allocated to Harbin that exceeded the size of the budget for the Paris Grand Opera and the Moscow Bolshoi Theatre. A lot of money was spent unproductively, though a lot was achieved’, relayed a local Harbin reporter.Footnote 56

That such an exorbitant budget had been allotted for a single tour indicated a high level of confidence in the ability of the participating musicians to exhibit Soviet artistic superiority and win the hearts of Harbin’s audiences. ‘One could suggest that the funds and effort to be spent have not been wasted, and that the Soviet opera in Harbin has been presented at a necessarily high level’ declared a correspondent of the official magazine for RABIS; ‘It is even more important here, just beyond the border, that Soviet art displays its true character. The interest in opera from the local Soviet colony and the foreign residents is notable.’Footnote 57Another Soviet reporter in Harbin offered a similar justification: ‘Harbin is the only place abroad where Soviet art can be widely cultivated and is the most fertile bud for the development of Soviet art.’Footnote 58 In all but name, the Soviet opera tour was intended to discreetly reassert extraterritorial privileges – to act as a spearhead for Soviet cultural encroachment in Manchuria.

It is striking, however, that given such liberal financial support and lofty goals, the tour did not garner much attention in the Soviet press. Though local émigré newspapers in Harbin such as Gun Bao (Гун Бао 公報) and Zarya (Заря) featured many reviews and advertisements regarding the visiting Soviet musicians, the tour received only brief mentions in All-Union Soviet publications, perhaps because it was considered little more than a provincial (and therefore relatively unimportant) topic.Footnote 59 When the Soviet press did report on the tour, they often focused on the strained political atmosphere of the region rather than the music.Footnote 60 For instance, a ‘Letter from Harbin’ published in the Soviet magazine Sovremenniy teatr exclaimed that the visiting Soviet artists had ‘to operate in a hostile atmosphere under the supervision of Chinese theatre censors incited by the White Guards’.Footnote 61 This sort of combative language characterised much of the official Soviet writing about the tour and the performing arts in Manchuria in general.

Several well-established figures from the former Imperial Russian opera scene were chosen to lead the tour. The conductor Yakov Pozen, who recently completed several seasons at the opera in Novosibirsk joined the troupe for the first winter season 1927–8.Footnote 62 For the second winter season of 1928–9, Ariy Pazovsky joined the tour, having just left his post as a conductor at the Bolshoi Theatre amidst a massive reorganisation campaign.Footnote 63 Vladimir Kaplun-Vladimirskiy, a conductor who had emigrated during the Revolution and worked with the Harbin symphony, assisted during both seasons.Footnote 64 The directors of the tour, Ivan Varfolomeev and Pavel Grigoriev, similarly brought plenty of expertise to the Harbin stage.

Most of the singers chosen for the tour, however, had far less experience. Several were promising young hotshots who had recently finished a season in Sverdlovsk, among them 26-year-old tenor Sergei Lemeshev and 24-year-old mezzo-soprano Anna Zelinskaya. Other vocalists on the tour included Odarka ‘Daria’ Sprishevskaya and Sofia Baturina (sopranos), Sergei Streltsov and Vladimir Briginevich (tenors), Vasily Ukhov (baritone) and Konstantin Knizhnikov and Alexander Shchur (basses).Footnote 65 While it is unclear if the organisers of the Soviet tour intended for it to be a pedagogical crash course, the pairing of novice vocalists with an accomplished tour leadership certainly made it an effective one. Following the tour, both Lemeshev and Zelinskaya would go on to develop illustrious careers at the Bolshoi Theatre.

Administrative mismanagement and the tense political atmosphere in Manchuria resulted in a stilted rhythm of performances throughout the eighteen-month tour. The first season ran from September 1927 to February 1928 and was followed by a lull in performances.Footnote 66 During the break between the seasons, the Soviet opera singers continued to rehearse in Harbin and a few found alternative work in the meantime. Baturina taught courses at the Harbin Music College and was described by one of her former students as an enthusiastic instructor who instilled the importance of both vocal technique and stage presence.Footnote 67 Many of the vocalists participated in recording sessions with travelling scouts from Victor Talking Machine in May (which I will discuss in a moment). By autumn 1928, the organisation of a second season for the visiting Soviet opera troupe had begun to fall apart. Budgeting at the Zhelsob had been mismanaged, and much of the funding provided by RABIS had simply ‘gone down the drain’ (ушли на ветер) by the end of the first season.Footnote 68 The second season did not open until October 1928 and only lasted until 13 February 1929, when funding ran out and violence over the railway escalated.Footnote 69

Issues of taste and tact: emplacing Soviet opera in Manchuria

By and large, the selections performed by the Soviet Opera of the Chinese Eastern Railway represented the musical tastes of the former imperial Russian bourgeois class.Footnote 70 Though a comprehensive list of all the works staged by the troupe was never published, advertisements and personal recollections attest to an ambitious repertoire: Eugene Onegin, Khovanshchina, Prince Igor, Russlan and Ludmila, Sadko, The Snow Maiden and The Tsar’s Bride from the Russian canon, alongside Aida, Il barbiere di Siviglia, Carmen, Faust, La juive, La traviata and Les contes d’Hoffmann from the larger European canon. None obviously embodied the spirit of working-class revolution. Neither Valentinov’s ‘mosaic opera’ The Fire Priestess (Жрица Огня) nor Yurasovsky’s opera Trilby based on the bestselling novel by George du Maurier – two relatively obscure works composed in 1914 and 1919 respectively – seemed to express Soviet values either.Footnote 71

Émigré audiences in Harbin, especially those with monarchist convictions, appreciated the staging of what they considered to be authentic imperial Russian culture – that is, music from the pre-revolutionary canon, and not the ideologically charged agitational music promoted by radical groups like the Proletkult.Footnote 72 Despite what Harbin’s émigré audiences might have imagined opera in the USSR to be, it is important to remember that the Soviet programming at the Bolshoi did not stray far from the pre-revolutionary canon. The same ‘great works’ were constantly rehabilitated and reinterpreted through a revolutionary lens and eventually became enmeshed in the Soviet system.Footnote 73 The ‘search for Soviet Opera’ (as Phillip Ross Bullock put it) continued well through the 1930s, and canonical Russian imperial works continued to function as a mainstays of musical prowess.Footnote 74 The Soviet state could not easily do away with the musical legacy of its predecessor state, just as Harbin’s opera fans could not easily be estranged from the imperial Russian canon, even if it was performed by Soviet representatives (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3. Khovanshchina performed by the Soviet Opera of the Chinese Eastern Railway at the Railway Assembly Hall (Zhelsob), c.1928. Emanuel Sztein Collection, Amherst Center for Russian Culture, Amherst College, b. 17, f. 1.

Figure 4. The Fire Priestess performed by the Soviet Opera of the Chinese Eastern Railway at the Railway Assembly Hall (Zhelsob), c.1928. Emanuel Sztein Collection, Amherst Center for Russian Culture, Amherst College, b. 17, f. 1.

The Soviet troupe was exceptionally busy during its time at the Zhelsob – a venue that might otherwise be considered a second-tier opera house given its remote location. Under the direction of Pazovsky during the second season (1928–9), the vocalists put on as many as four simultaneous productions.Footnote 75 Harbin’s avid opera-goers could watch The Tsar’s Bride on Saturday followed by Faust on Tuesday, The Fire Priestess on Wednesday and Eugene Onegin on Thursday – all within the same week!Footnote 76 Given the large budget and significant demand from local audiences in Harbin, the tour was able to expand to stages at nearby venues; the newspaper Gun Bao began grouping advertisements for productions at the Zhelsob and the Mechanical Assembly Hall (Mekhsob) together, since the same singers appeared on both stages during the same week.

Notably, the productions enlisted a wide range of participants from a wide range of racial and ethnic backgrounds in Manchuria. Photographs from backstage at the opera attest to the key contributions of the non-Russian residents in Harbin in creating the sets, props and costumes displayed on stage. Rosters of the Harbin Symphony that accompanied the opera performances also included several non-Russians (Figures 5 and 6).Footnote 77 The number of classically trained Chinese and Japanese instrumentalists and vocalists grew significantly following the establishment of the Shanghai Conservatory in November 1927 – which, incidentally, had been co-founded by Vladimir Shushlin, an émigré bass who performed on stage alongside his Soviet compatriots during the Soviet opera tour.Footnote 78 Still, while non-Russians certainly helped to make the tour possible, Russian émigré and Soviet participants remained in charge and dominated leading musical roles.

Figure 5. The Staff of the Opera at the Railway Assembly Hall creating props backstage, c.1926–9. Emanuel Sztein Collection, Amherst Center for Russian Culture, Amherst College, b. 17, f. 2.

Figure 6. The Staff of the Opera at the Railway Assembly Hall, c.1926–9. There is a potential reference to the Soviet symbol of the crossed hammer and sickle in the staging of this photograph. Note, however, that the symbol of the Chinese Eastern Railway similarly comprised two crossed sickles. Emanuel Sztein Collection, Amherst Center for Russian Culture, Amherst College, b. 17, f. 2.

Beyond the opera stage, however, the power relations were less clear; émigré and Soviet residents of Harbin were technically subject to Manchurian rule, even if they managed to circumvent some regulations through informal extraterritoriality. The legacy of Russian imperialism in northern China only added to the peculiarity of this social hierarchy, leading the American columnist Olive Gilbreath to describe Harbin notoriously as a place ‘where yellow rules white’.Footnote 79 The historian Blaine Chiasson has dubbed this social hierarchy one of ‘administering the colonizer’, showing how the story of Harbin has often been narrated from extreme vantage points: as a victim of Russian imperialist exploitation or the beneficiary of Russian cultural influence, a tale of suppressed Chinese nationalism under Russian rule or Chinese culture that ignored Russian influence altogether.Footnote 80 He prefers to acknowledge the anomalies, ambiguities and discontinuities in the historical record – and to recognise that, especially in moments of geopolitical rupture, border zones such as Harbin tend to produce emergent, informal and fragile kinds of social connection. These kinds of connections are not always most productively accounted for via the frameworks of political opposition, ethnonationalist difference or the binary of colonised and coloniser.

The touring Soviet opera did little to appeal to Chinese audiences, though there was certainly reason to be cautious. A production of The Mandarin’s Son by César Cui and The Geisha by Sidney Jones staged at the Zhelsob in 1924 caused an uproar over essentialised depictions of Chinese characters that audience members found insulting.Footnote 81 Representatives of Warlord Zhang’s government reportedly stormed out in protest, and the Chinese press wrote a scathing review that led to a protest involving several hundred people.Footnote 82 In a similar vein, the first Soviet ballet, The Red Poppy, composed by Reinhold Glière in 1927, spectacularly managed to denigrate the Chinese on stage in Moscow in the name of anti-imperialism, worsening the strained political relations between the nations.Footnote 83 Amidst the indiscriminate arrest and harassment of Soviet citizens in Harbin, the touring Soviet opera troupe avoided staging similar works that might have risked angering the local Manchurian population. Though treading so lightly may have undercut the goal of promoting détente or cross-cultural understanding amidst the calls for war, it did demonstrate a measured response to the shifting political ground upon which they stood.

In that regard, the Soviet opera tour to Manchuria did not represent ‘sounds of crossing’, to use the phrase with which Alex Chávez has described the militarised US–Mexico border,Footnote 84 as much as it did the mission of upholding the ambiguous Soviet vision of the border. The Soviet opera performances did not engage with themes of crossing into Manchuria, nor did its performers set out with the goal of promoting solidarity between communities on either side of the border. Instead, the tour reflected a tenuous collaboration in which Soviet cultural supremacy and territorial domination was upheld.

Considering these exceptional social circumstances, we might think of the opera stage in Harbin as an exceptional space where collaborative musical performances supplanted – if only temporarily and tenuously – the prescribed social hierarchies and ideological frames imposed by the ruling forces in Manchuria. This is not to suggest that the Zhelsob somehow existed outside the realm of Warlord Zhang Zuolin’s political influence, but rather that the complex sociality of Manchuria in the late 1920s was constantly negotiated in the hall. If at times the Soviet opera singers and conductors wielded a certain power over the opera stage at the Zhelsob, it was at least partially diffused by the desires of local émigré and Chinese participants who contributed to the performances. The large number of musicians and staff needed to stage as many as ten different operas in a single season required close collaboration across perceived ideological and ethnic lines. In that regard, the opera stage itself represented a peopled domain within the larger jurisdictional framework of Soviet informal extraterritoriality – a space in which the rules and norms imposed outside the hall could be temporarily bent or rewritten.

The curtain call becomes a call for war

As the political and financial circumstances of the Soviet opera tour to Manchuria deteriorated, the troupe gradually disbanded; the visiting vocalists did not all leave Harbin at the same time. Following the premature end of the second season in February 1929, a few vocalists performed pared-down productions and solo concerts at other performance venues in Harbin like the Mechanical Assembly Hall (Mekhsob), the Hotel Moderne and the Atlantic Theatre.Footnote 85 Zelinskaya and Baturina held farewell concerts in March and April respectively.Footnote 86 By May 1929, all the remaining Soviet opera singers from the tour had departed from Harbin.

The émigré press in Harbin was naturally upset to see many of their best vocalists abandon their city for good. ‘If this summer we can’t listen to symphonic concerts, then it is obvious that this winter, we won’t be able to watch any operas’ lamented a reporter for Zarya, fuming at the lack of concerts after the untimely end of the tour. ‘But that’s the entire system of building communism’, he continued: ‘First, they put on theatrical productions… then they institute a “five-year plan” and so on. But the result is always the same: In a short amount of time, they manage to destroy something that somehow still managed to exist.’Footnote 87 In other words, the Soviet singers had come to Harbin and put on a good show but ended up impairing the city’s opera in the process. ‘Never take advice from Soviet experts of the theatre and music business’, the paper warned.Footnote 88

As geopolitical tensions continued to rise, the Manchurian authorities began to take bold action against Soviet citizens in Harbin. Visiting Soviet theatre troupes, whose works tended to be more agitational and ideologically charged, became easy targets. ‘The Chinese censor turned out to be so merciless that not a single play from the contemporary repertoire was allowed to see the limelight’ barked the Soviet magazine Sovremenniy teatr on 18 May 1929; ‘The suspicion of the Chinese authorities reached the point that the commissar would burst into rehearsals when classes were taking place in the workers’ drama club and stop the rehearsal, believing that they were engaging in propaganda.’Footnote 89 In a sudden assertion of power on 26 May 1929, the Manchurian authorities indiscriminately closed all the musical venues in Harbin for several days to honour the reinterment of the ashes of the Chinese revolutionary Sun Yat Sen at a mausoleum in Nanjing.Footnote 90 Nevertheless, this sort of aggressive action did not deter the Soviet authorities from continuing to send their artists to the zone of conflict. Amidst active armed combat in the following months, the newly formed Alexandrov Red Army Ensemble and the Blue Blouse agitational theatre troupe performed for audiences across Manchuria.Footnote 91

When Soviet and Manchurian soldiers began to shoot at one another in August 1929, neither the Republic of China nor the Soviet Union had officially declared war. Both countries had ratified the Kellogg–Briand Pact on 24 July 1929, an agreement that ‘denounced recourse to war for the solution of international controversies’ and sought to resolve all conflicts through ‘pacific means’.Footnote 92 When an armed confrontation began a few weeks later, neither party wished to antagonise the other countries in the League of Nations that had signed the pact.Footnote 93 There was little time to judge or protest the armed clash, however, as Stalin’s Special Far Eastern Army secured a swift victory after just four months of fighting.Footnote 94 The Khabarovsk Protocol signed on 22 December 1929 re-established the scheme of joint administration over the railway, which in effect provided the Soviet authorities with de facto control.Footnote 95

In recent years, scholars have made the argument that the military clash was a legitimate war, underscoring the thousands of casualties and severe destruction that it caused; as the historian Michael Walker put it, it was ‘the war that nobody knew’.Footnote 96 Nevertheless, many popular sources continue to refer to the series of events as a ‘conflict’ or a ‘dispute’ due to its limited duration and geographic reach; this has been especially true in Russian-language historiography.Footnote 97 Still, whether war or conflict, the sustained fighting was plainly a product of internalised Soviet Russian imperialism – an instance of what the historian Lauren Benton calls ‘imperial small wars’: the kinds of ‘violence at the threshold of war and peace’ in which empires specialise to ‘keep and produce order’.Footnote 98 For Benton, the label ‘small wars’ speaks to ‘the staccato rhythm’ of imperial violence and its ad hoc justifications; sporadic armed conflict was an integral, rather than exceptional, aspect of the culture of policing the imperial frontier.Footnote 99 As a clear example of an ‘imperial small war’, the Sino-Soviet War of 1929 demonstrated the reluctance of the Soviet government to relinquish the colonial dependencies and extraterritorial privileges of its imperial predecessor state.

The informal extraterritoriality enacted by Soviet citizens in Manchuria in the late 1920s was short-lived. Less than two years after the Soviet army forcefully secured these privileges, the Kwantung Army of Imperial Japan staged the Mukden Incident in September 1931, a false-flag operation that served as the pretext for a full-scale invasion and occupation of Manchuria. The consequence was the establishment of the puppet state of Manchukuo, which maintained a range of new administrative, economic and cultural connections with the Japanese Empire.Footnote 100 Far fewer Soviet musicians crossed the Manchurian border, though local Harbin musicians began frequently to tour the Japanese mainland. By 1935, the Soviet government was forced to sell the CER to Imperial Japan, which put an official end to any special privileges enjoyed by Soviet subjects in the region.

Radishes and friendships: (mis)remembering the Soviet opera tour

Looking back, several eyewitnesses have written that the operas performed by the visiting Soviet opera troupe were among the most memorable and important musical experiences during their several decades living in Harbin. In many ways, the two seasons of the tour represented the last hurrah of opera in Harbin before the period of Imperial Japanese occupation. Not only were the productions well funded and cast with outstanding vocalists, but they offered audiences and performers temporary reprieve from the tense political atmosphere in Manchuria. Behind the scenes, the informal extraterritoriality of the opera stage engendered cross-cultural collaborations – and in some cases, enduring friendships – between Soviet, émigré and Manchurian musicians amidst the backdrop of geopolitical conflict. As I have already indicated, several of the visiting Soviet opera singers became deeply enmeshed in the local community during their time in Harbin. Even Sergei Lemeshev (Figure 7), who went on to become one of the Soviet ‘tenor cults’ at the Bolshoi and ‘a middlebrow mainstay of Soviet musical life in the Stalin period’, was claimed by the Harbin émigré community as one of their own.Footnote 101 Notably, however, Lemeshev himself never publicly admitted to feeling the same way about Harbin. A critical comparison of personal accounts of the tour reveals inconsistencies in the ways that different populations remembered the Soviet Opera of the Chinese Eastern Railway and interpreted its legacy, and how later political issues came to shape writing about the tour.

Figure 7. Tenor Sergei Lemeshev in Harbin, c.1928. Emanuel Sztein Collection, Amherst Center for Russian Culture, Amherst College, b. 16, f. 2.

In his memoir published in the USSR, Lemeshev described his first day in Harbin through the curious eyes of a Soviet subject in Manchuria for the first time. When confronted with his own Soviet identity by a local émigré taxi driver, however, the tone of his writing shifted abruptly:

I remember it was a warm moonlit evening when we arrived in the capital of Manchuria. It was a marvellous golden autumn in the capital. They took us from the station in cars. I noticed we drove on the left-hand side, and while I was wondering about the strange traffic pattern (later I learned that this was the rule for many foreign cities), we reached the Palace Hotel, so I never got to see the city. Only in the morning could I get better acquainted with it.

The theatre was in a recently built part of Harbin, the so-called ‘New Town’. The structures were almost all single-storey cottages in which Soviet railroad workers lived. The main street reminded me of Tverskaya Street [the main boulevard] in Moscow. The city was completely European with all the urban contrasts. Well-built houses, luxury shops and stores, banks and other commercial enterprises in the centre of the city and terrible poverty in the suburbs, overcrowded to the limit; in every room of these little crowded houses lived fifteen to twenty people, mainly Chinese. The centre of Harbin was populated mainly by foreign businessmen.Footnote 102 A special and quite significant group were White Russian émigrés (белоэмигранты), who had their own newspapers, entertainment establishments, etc. The very first morning I was convinced of their blind hatred of everything Soviet.

As soon as I managed to step outside the hotel, a taxi pulled up and the driver offered his services to me in perfect Russian. I sat in the car, and my attention turned to the city, whose daily life differed drastically from ours in the USSR. The driver started up a conversation. He was thirty years old, wearing an unkempt, greasy coat and hat. Having heard that I was from Moscow, he asked:

‘Well, how is life there?’

‘Very good’, I answered, without a second thought.

My words shot through him like bullets. His face changed and became as angry as a wild boar. My taxi driver turned out to be a former officer; I felt the rage of the White émigrés, fuelled by the Russian nobility led by Prince Kirill.Footnote 103 From Paris he [Prince Kirill] had congratulated his fugitive countrymen on Christmas Day, promising to celebrate the next New Year in Russia. At that time, the White émigrés lived in anticipation of the collapse of Soviet power and the hope of returning. Seemingly, my words upset the ghostly balance of the émigré driver’s soul and drove him into a frenzy.

The encounter put me on guard. I understood how difficult it would be to work here and carefully tried to avoid similar incidents.Footnote 104

Lemeshev’s account underscores how strained Soviet–émigré relations were in Harbin during the tour. It is true that many Russian émigrés in Harbin were openly hostile to anything Soviet; the local press constantly ridiculed Soviet policies, and many held firm to their monarchist convictions (hence their name ‘white émigrés’ in reference to the Tsar’s White Army). In turn, the Soviet press framed Harbin as a hornet’s nest of anti-revolutionary activity.Footnote 105

There is good reason to believe that Lemeshev was not free to publish his feelings about the tour in the Soviet press, however. Vladimir Serebryakov, a local Harbin student, played second violin at the opera while Lemeshev was in town. Recalling his conversations with the tenor many years later, Serebryakov noted that Lemeshev had many fond memories of his time in Harbin, which the censors had forbidden him from including in his memoir.Footnote 106

For instance, it is telling that Lemeshev neglected to mention his participation in the production of Halévy’s La juive in his memoir, despite the fact that it was staged during both seasons, and appeared in two different theatres.Footnote 107 The opera’s topical theme of religious tolerance resonated with Harbin’s large Jewish population, numbering over 13,000 people in 1927.Footnote 108 Antisemitic views were already widespread in the USSR in the late 1920s and had become a point of contention in Manchuria.Footnote 109 When the Harbin branch of RABIS forbid their opera singers to put on a concert of Jewish folk music at the Zhelsob in May 1928, the émigré press went into an uproar; the Soviet authorities defended their actions by claiming that the concert would have promoted Zionism.Footnote 110 It is reasonable to believe that Lemeshev strategically avoided mentioning his participation in La juive in his memoir, given the delicacy of the subject.

Lemeshev also omitted the fact that several of his colleagues fell victim to Stalin’s purges. The Soviet musicians who returned from Manchuria had to worry about accusations of collusion with Chinese nationalists and former White Army officers during their time in Harbin. Among those who were indiscriminately repressed was the assistant conductor Kaplun-Vladimirskiy. He served a lengthy sentence at the GULAG in the Komi Republic from 1936 to 1944 and was only fully cleared of the charges levied against him in 1957.Footnote 111 The Harbin émigré press sincerely empathised with the Soviet operatic vocalists who suffered upon returning to the USSR. One reporter harped on about the unfair treatment of the conductor Pazovsky upon his return, accusing the Soviet authorities of antisemitism.Footnote 112 Others, like Lemeshev, managed to keep quiet about their time in Manchuria until they felt it was safe to discuss it; Serebryakov himself did not publish anything about his own experiences in Harbin until 1997, several years after the collapse of the USSR.

The politics of identity among the émigré population in Manchuria was more complex than Lemeshev’s memoir and the Soviet press made it out to be. Following the normalisation of relations between China and the USSR in 1924, the émigré population in Manchuria was forced to make a choice. In the eyes of the Chinese government their imperial passports had become invalid – they could either become Soviet citizens or effectively remain stateless; a relatively small number were granted Chinese citizenship.Footnote 113 For those who were stateless, it was difficult to find work and almost impossible to travel abroad. Many who applied for Soviet citizenship called themselves ‘radishes’ – owners of a red Soviet passport who remained loyal to the aims of the Tsar’s White Army and the Russian Empire: red on the outside, white on the inside.Footnote 114

I conducted interviews with former residents of Harbin to get a better sense of the political tension between Russian émigrés and Soviets in the city. One interlocutor told me that during her childhood in the late 1920s, she attended a Soviet school in Harbin. Alongside their daily lessons, the teachers would impart Soviet propaganda to the schoolchildren. When she came home at the end of the day, she would tell her father about what the teachers said. Her father was a monarchist and would work himself into a frenzy proving to her how everything that they taught her was wrong.Footnote 115 Another interlocutor, whose family was staunchly anti-Soviet, told me how he loved listening to the Soviet radio growing up in Harbin in the late 1920s and early 1930s. He didn’t see any problem in listening to Soviet broadcasts, especially music from the Russian repertoire, because it was felt to be less politicised than other programming filled with more overt propaganda.Footnote 116 A third interlocutor told me how her émigré family often hosted visiting Soviet artists for dinner in the late 1920s, and how they would exchange gifts. She remembered how her father hung a poster of Zelinskaya, one of the visiting Soviet opera artists, in his doctor’s office.Footnote 117 By and large, the ideological divide between Soviet and émigré residents did not necessarily shape the musical inclinations of the former Harbin residents with whom I spoke.

Outside observers also seemed to suggest that the opera at the Zhelsob was a relatively neutral political space. In a feature length article for Harper’s Monthly Magazine published at the end of the tour in March 1929, Gilbreath wrote:

The Chinese Eastern Railway dispenses its stupendous profits with a gesture of true Russian magnificence. It has built a smart railway club with a delicious cuisine, charming gardens, an opera. Last year it spent three hundred thousand dollars on the opera, with artists out from Leningrad and Moscow. At these playgrounds of the railway Red and White mingle. At one table in the gardens a group of the Old Regime the women marked by their thin faces and fragile skulls, the men in well-cut clothes are watching the sunset over the Sungari. At the next table is the shaven head and thick neck of a good Siberian bourgeois, tucking away a Gargantuan Russian meal: he wears a Russian shirt, his boots smell of oil. He is probably a profiteer in furs; the woman with him wears a pink silk blouse and many bangles. A few Chinese faces here and there give the scene the strange flavour of the Far East and the Far North. But mainly the scene is Russian: Russia old and mellow; Russia new and masterful. The railway – that great power which sustains, overshadows, and rules Harbin – is their common meeting ground. But there the line is drawn.Footnote 118

The slippage between the railway and the opera in Gilbreath’s description is telling. The railway is a space in which émigrés employed by the Manchurian government and Soviets worked side by side, and its opera, as a subsidiary organisation, promoted the same ethos. Both were surely sites in which disagreements arose and emotions ran high, but they compelled unpredictable forms of interpersonal proximity and exchange that seemed to model and even produce alternative modes of sociality.

Despite the fraught political climate of the tour, it appeared to proceed without increasing any tensions or provoking a backlash. By all accounts, the most memorable moments in the tour seem to have been unintentionally comic ones, undisturbed by the Soviet–émigré divide amongst the performers and audience. In private conversations outside the Soviet press, Lemeshev retold a light-hearted anecdote about the opening night in Harbin:

We put on a production of Gounod’s Faust. The orchestra played the introduction and the prologue began. Old Faust (sung by the excellent bass Alexander Shchur) had the line: ‘I’m here, why are you surprised?’ Before Shchur had time to finish singing the last word of the line, the lights went out in the entire building. As you know, in old theatres there was a booth for the prompter on the stage near the ramp. In the darkness, the singer moved forward and fell into the booth, right on the shoulders of the prompter. At that moment the light flashed back on, and the confused conductor Ariy Pazovsky, not finding Faust in place, shouted: ‘Sasha! Where are you?!’ From the prompter’s booth, in tense silence, a rich bass sounded: ‘I’m here! Why are you surprised?’ There was a still deathly silence in the hall for some time, and then a long, Homeric laugh broke out. Everything turned out all right, the performance went well and was a phenomenal success.Footnote 119

Stories such as these point to a conception of the Soviet opera tour that diverged from an overtly politicised diplomatic campaign. What transpired during the tour was less an aggressive exhibition of Soviet musical prowess than a jovial collaboration in which meaningful relationships formed on stage.

The mentorship of experienced conductors helped make the tour a success for Soviet and émigré participants alike. Lemeshev described his work with conductors Pozen and Pazovsky as crucial to the development of his vocal technique and ‘realising the necessary range to fulfil my artistic concepts’.Footnote 120 What Lemeshev may have lacked in technique he reportedly made up for in looks and charisma; he was something of a heartthrob, as the émigré ballerina Nina Kozhevnikova recalled:

With regard to the Russian tours, the performances of Lemeshev and KozlovskyFootnote 121 were, of course, always like a holiday. How many hearts fluttered, and how many different names we gave them behind the curtains – all this is evidence of how much they dominated our moods and that of the entire Harbin audience.Footnote 122

Despite his success, Lemeshev noted that ‘the white guard newspapers frequently gave our productions bad reviews’.Footnote 123 Certainly not all were negative; among those published in the émigré newspapers Zarya and Gun Bao that I examined, all were overwhelmingly positive. Even if more staunchly anti-Soviet publications offered more severe criticism of Lemehsev’s developing vocal ability, they seemed to have little effect on his popularity: as he noted, ‘even the foreigners paid no attention to them and received us very warmly, not to mention the Soviet railroad workers’.Footnote 124

During their time in Harbin, the conductors Pozen and Pazovsky also became acquainted with many up-and-coming émigré musicians in the city. Georgiy Sidorov, then a violin student, recalled how Pozen would often visit his home and listen to 78 rpm recordings with him. He noted the maestro’s reaction to listening to a recording of Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 6 conducted by Leopold Stokowski with the Philadelphia Orchestra – an American recording by Victor Talking Machine, impossible to come by in the Soviet Union:

In the corner of the dining room there was an old plush sofa, big and wide. Having made himself comfortable, he [Pozen] prepared to listen. He sat in the corner and froze, full of attention. He closed his eyes and immersed himself entirely in the sounds of the orchestra. I sat next to the Radiola,Footnote 125 opposite, and also listened attentively. Back then, there were no long-playing records, and after each one you had to wind up the mechanism again. I accidentally glanced at my guest and realised that he was crying, sitting with his eyes closed… They were stifled male tears.Footnote 126 How one must feel, and empathise, so that they suddenly roll down the cheek.Footnote 127

Here, a shared affective moment, activated by music, comes to stand for the intimate connections that elude the adversarial frames of the surrounding geopolitical conflict. And, to be sure, many young musicians had a reason to be grateful. Pazovsky took a chance on Vladimir Serebryakov and offered him his first paying gig as a violinist – something that he recalled with real warmth:

Only now can I realise what immeasurable benefit my communication with Pazovsky – his professionalism, talent, and organisational skills – brought me. Ariy Moiseyevich’s exactingness towards himself and the performers was unique, hence the high quality of the performances at the Harbin Opera House.Footnote 128

RABIS may well have intended the tour as propaganda – a demonstration of Soviet cultural might – but from the perspective of the actors who performed and embodied this propaganda, it had less legible, less governable effects: like the railway itself, perhaps, the opera enforced close contact and collaboration between actors who were often disinclined to think of their interactions as political in the first place.

Overall, it seems that the goal of promoting Soviet soft power in Manchuria through the opera backfired. Rather than wooing émigrés in Harbin to Soviet ideology, local audiences befriended the visiting singers and even adopted them as their own. A review of the second opera season described the participants as a ‘friendly, thoughtful ensemble in which all performers – from the lead roles to the most insignificant – performed their parts and contributed their touch to the overall picture’.Footnote 129 Looking back on the tour several years later, Zarya went so far as to describe the visiting Soviet vocalists as Karbintsy (Harbinites) – not Soviet representatives, but beloved artists who had become integrated into the community despite their relatively brief stay.Footnote 130 When the Soviet opera singers returned to Moscow, the newspaper reported that they instigated an artistic ‘war from Harbin’ at the Bolshoi Theatre; the soft power of their tour apparently flowed in both directions.Footnote 131 Years later, when rumours spread that the mezzo soprano Zelinskaya might return to Harbin, the émigré press warmly welcomed her back home.Footnote 132 Whether or not the touring vocalists thought of themselves as agents of the Soviet state or as repatriated émigrés from Manchuria, they were seen by different audiences as both.

Deterritorialised media: recording the Soviet opera tour

Perhaps the most surprising feature of the Soviet opera tour was that its performances in Harbin reached audiences across the globe as part of the prestigious Victor Red Seal gramophone recording series – a distinction reserved for the likes of Caruso, Chaliapin, Horowitz and Toscanini. Throughout 1929, the record label issued a total of thirty-seven shellac records made by the Soviet singers on the tour for listeners in Manchuria and the United States; later in 1937, the records were also reissued by Victrola for the Latin American market.Footnote 133 The records appeared in Victor’s Russian supplements and catalogues around the world and received praise in magazines like The Phonograph Monthly Review and The American Music Lover. Footnote 134 Zelinskaya’s popular record with arias from Rusalka and The Snow Maiden even made it into Victor’s general catalogue for 1930.Footnote 135 It is uncertain whether artists received permission from RABIS to work with a foreign company, or whether the Soviet authorities were even aware that they did; the recordings were never officially issued in the USSR. Likewise, the discs that circulated in the Americas were never marketed as having been recorded in Manchuria, let alone by touring Soviet artists. Most listeners of the recordings at the time were oblivious to the fact that the recordings were made amidst an ongoing geopolitical conflict; the political and geographical context of the tour was obfuscated, deterritorialised by the media form of the shellac gramophone record.

During the Soviet opera tour, the American businessman Roy Burdin served as the director of Victor Talking Machine’s head office in the RoC.Footnote 136 While stationed in Shanghai, Burdin introduced the ‘orthophonic’ electrical recording technology.Footnote 137 The ease of producing electrical recordings spurred a new wave of ‘ethnic recordings’ made by recording scouts sent across the world, and Burdin was in charge of organising the sessions in the RoC.Footnote 138 Ethnic recordings circulated essentialised musical tokens from various parts of the world, which helped introduce American ears to tango from Argentina, hula from Hawaii, kroncong from Indonesia and more. Michael Denning has famously described this explosion of musical diversity in the recording industry in the late 1920s as a ‘noise uprising’ – a sonic premonition of the political decolonisation efforts in later decades.Footnote 139 In contrast to the highly localised musical styles that Denning discusses, however, it was Russian music (and opera in particular) that Burdin’s recording scouts chose to record as the sole representative of Manchuria.

Though opera was certainly popular in Manchuria, the recording scouts could have easily chosen to record regional Chinese styles instead. Whether they realised it or not, this choice had political implications for the Chinese struggle for sovereignty. If there was any backlash, however, it did not stop Victor from selling thousands of recordings of Soviet and Russian émigré musicians in Manchuria across the globe. Burdin must have understood what a rare opportunity it was to record talented Russian musicians from their homeland who were otherwise inaccessible. The Bolshevik government had seized all of Victor’s gramophone production facilities in Russia in 1918 without compensation, forcing the company to abruptly curtail its business in the country.Footnote 140 Even amidst violence in a contested semi-autonomous zone, there was money to be made in filling in Victor’s operatic offerings. The 1929 edition of The Victrola Book of the Opera featured several of Victor’s recordings of Soviet artists in Harbin, which were slotted in alongside those by Feodor Chaliapin, Nina Koshetz and Albert Coates conducting the London Symphony Orchestra to flesh out each Russian opera in the company’s catalogue.Footnote 141

The recording engineers enlisted to make recordings in Manchuria came from the company’s factory in Japan and had recently returned from a recording expedition in Korea.Footnote 142 Unfortunately, the documentation of the recording trip to Harbin was sparse; the names of the recording scouts have likely been lost, as have many of the logistical details.Footnote 143 What is apparent, however, is that the scouts made an initial trip to Harbin on 15 April 1928, where they made a few test recordings of Zelinskaya: the aria ‘Dear Friends’ from Tchaikovsky’s Queen of Spades (Victor Matrix XVE-01829) and Mussorgsky’s arrangement of the folk song ‘Gopak’ (Victor Matrix XVE-01879) (Figure 8).Footnote 144 They returned to Harbin the following month and made a total of 126 recordings. The recording sessions occurred 12–29 May, with a few breaks scattered in between, and were split between Red Seal sessions in which opera was recorded, and the ‘ethnic’ black label sessions, in which local émigré artists from Harbin recorded Russian folk tunes and songs in the popular ‘romance’ (романс) genre.Footnote 145

Figure 8. ‘Gopak’ by Anna Zelinskaya (Soviet), accompanied by Alexander Slutzky (émigré) on piano. Arrangement of a folk song attributed to Modest Mussorgsky. Victor 4117, Side B, Matrix XVE-01879, take 1. Recorded 15 April 1928, during the initial scout mission to Harbin. Reissued in Buenos Aires as Victrola 4117 in 1937. Collection of Recorded Sound, Museum-Archive of Russian Culture, San Francisco, b. VIC-5.16.

Soviet and émigré artists collaborated on the majority of the Red Seal sessions. Whereas the visiting Soviet vocalists performed the lead vocal parts, émigré artists performed in the opera chorus and symphony that accompanied them. The émigré conductor Alexander Slutzky directed the opera chorus and played the piano on more stripped-down tracks (Figure 8). Victor only credited the main vocalists on the tracks, simply printing vague text like ‘Russian Opera Orch’. or ‘Russian Opera Chorus’ when necessary, with no mention of Harbin or anything to differentiate the recordings from those with Soviet artists (Figure 9). If there was an ideological divide between the visiting Soviet vocalists and the local musicians in Harbin, it was not seen or heard on Victor’s recordings.

Figure 9. ‘Lullaby’ by Daria Sprishevskaya (Soviet), accompanied by ‘Russian Opera Orchestra’ (émigré). From Sadko by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, scene 7. Victor 4112, Side B, Matrix XVE-01875, take 2. Recorded 26 May 1928. Issued by RCA Victor Co. of China, Shanghai, c.1929. Collection of Recorded Sound, Museum-Archive of Russian Culture, San Francisco, b. VIC-5.16.

The finalised shellac records made their way to Harbin in three shipments, the first of which arrived in mid-February before most of the visiting Soviet artists returned to the USSR. Lemeshev wrote that after returning to the USSR, he used his personal copies of the recordings that he made in Harbin as evidence of his vocal abilities.Footnote 146 His Harbin records surely helped him as he went on to a build a prolific recording career, despite their restricted circulation in the USSR. It is quite possible that the tenor’s interest in gramophone records began during the Soviet opera tour to Manchuria; he later admitted that he spent hours in the gramophone shop in Harbin listening to Caruso, Gigli, Schipa and McCormack.Footnote 147 Like Pozen, Lemeshev took inspiration from the immense selection of recordings produced outside of the USSR that were available for purchase in the city.

As the records circulated, they quickly lost any indication of the strained political context in which they were created. In Harbin, the recordings were primarily distributed by the department store Churin & Co., which served as the official representative of Victor and its sister company His Master’s Voice in the region (Figure 10). Nowhere in Churin’s advertisements did they mention that the operatic works were technically recorded by Soviet artists – they were simply marketed as ‘records of Harbin tunes’ (пластинки Харбинскаго напѣва) (Figure 11).Footnote 148 Elsewhere for the Russian diaspora in New York, the records were marketed as ‘straight from Russia’ (непосредственно из России) and having ‘arrived from Europe’ (получен из Европы), with no mention of Manchuria or the Soviet tour.Footnote 149 The politically ambiguous circumstances of the Soviet opera tour to Manchuria and Victor’s Harbin recording sessions helped facilitate a multitude of origin stories, local interpretations and marketing opportunities.

Figure 10. Gramophone Department at Churin & Co. in Harbin, c.1930s. Photograph by Ablamskiĭ, Vladimir Pavlovich. Harbin, 1929. World Digital Library Collection, Library of Congress, No. 2018687679. Original image at Irkutsk Municipal History Museum.

Figure 11. Advertisement for the Soviet Opera tour records at Churin & Co. in Harbin. Gun Bao (17 February 1929), 5. Russia Abroad Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Archives.

Reassessing agency and intentionality on the early Soviet opera stage

In the introduction to an oft-cited volume of the same name, the historian Ronald Robinson famously popularised the term ‘railway imperialism’ to describe the relationship between infrastructure and colonial expansionism.Footnote 150 ‘The railroad’, he wrote, ‘was not only the servant but also the principal generator of informal empire’; put another way, ‘imperialism was a function of the railroad’.Footnote 151 Building on this thesis, R. Edward Glatfelter argued that ‘the decades of Russian imperialism in northeast China had essentially been years of railway imperialism’, noting that ‘when the empire fell, its successor state, the Provisional Government, despite a burning desire to be liberal, did not allow the Russian national interests to be sacrificed to ideological purity’.Footnote 152 More recently, Bruce Elleman and Stephen Kotkin dedicated an entire volume to the tale of imperial expansion in Manchuria as a function of ‘railway power’ – a constellation of competing railway imperialisms by the Russian, Chinese and Japanese empires, which generated ‘grey areas’ of ‘semi-colonial’ rule.Footnote 153

Notably absent from these otherwise detailed political accounts of railway imperialism and power in Manchuria, however, are the vibrant cultural practices that developed with and through extraterritoriality. To subsume all of Russian imperialism in Manchuria under the umbrella of a railway infrastructure – even one as salient to daily life as the Chinese Eastern Railway – risks generalising the complex perspectives and daily experiences of those who participated (willingly or not) in such a project.Footnote 154 There’s no denying that the railway was critical to paving the way for the creation and eventual Soviet reclamation of a colonial dependency in Manchuria. Nevertheless, music did not simply accompany the imperial might of the railway but helped constitute a culture of the railway itself. The musicologist Francesca Vella developed a similar idea in her study of ‘railway operatic mobility’, arguing that the locomotive power afforded by the railway helped to standardise and unify distinct operatic scenes in Bologna, Florence, Milan and other towns under the guise of a single Italian aesthetic.Footnote 155 Applied to informal extraterritoriality in Manchuria and a deadly war, however, the stakes of such ‘railway operatic mobility’ extend beyond questions of aesthetic style and technological modernity.

While there is no denying that, in specific circumstances, Soviet musicians toed the official party line and wholeheartedly supported efforts dictated ‘from above’, it is important to remember that this was not always the case. There is a risk of effacing the agency and personal intentions of musicians when describing their actions through the lens of a state apparatus; even in the context of war, the touring Soviet musicians did not simply become pawns of foreign policy. As the musicologist Richard Taruskin famously argued in the case of Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony, there is an even greater danger in mapping the intentions of Soviet musicians onto simplistic narratives of martyrdom or heroism that reflect how we ourselves might have liked them to act. In his words, ‘We can learn a great deal from the cultural artefacts of the Stalinist period, but only if we are prepared to receive them in their full spectrum of greys.’Footnote 156 Especially in the context of war, when the stakes are high and it is easy to assign and absolve guilt, we would do well to heed Taruskin’s warning.

There is an ethical imperative not to simplify the complexities and excesses of war, even if it disrupts our own worldview. The tour of the Soviet Opera of the Chinese Eastern Railway is just one of many cases in which musicians were mobilised in the name of a certain political cause, but whose actions did not always align with or fully embody the ethos of that cause. We must, I believe, take extra care to address the agency of those, like Sergei Lemeshev, who were subject to strict censorship and could not express their true feelings about their performances in the Soviet press. Though he may have become a prototypical example of a Soviet tenor under Stalin, his actions as a young musician in Harbin show that his personal values did not always align with those of the state.

The intimate and fragile interpersonal relationships fostered by the informal extraterritoriality of the opera stage in Harbin far exceeded – and at times, perhaps even negated – the official goals set by the Soviet Arts Union for the tour. Whether friendships with the ‘enemy’ truly indicated a betrayal of Soviet values was a matter of perspective. Moreover, whether the Soviet artists themselves internalised their acceptance into the Harbin émigré community remains to be seen. Several musicians from the tour were repressed or discriminated against upon their return to the USSR and were not free to write about their experiences. Those who made it back relatively unscathed had few avenues to speak out against the mistreatment of their colleagues and sometimes waited decades before publishing anything about their time in Harbin.

We also should take care when evaluating the musical residue of war, be it gramophone records that circulated far beyond the site of conflict, or set decorations made in collaboration by people on opposing sides of the conflict. It should go without saying that such cultural artefacts cannot (and should not) be reduced to a simplified narrative of ‘us versus them’ or explained away as mere products of a state agenda. The case of the Soviet Opera of the Chinese Eastern Railway is a stark reminder of how quickly the theatre of opera can slip into the theatre of war, of how even lavish operatic fantasy might remain essential to the quotidian business of survival and self-definition during wartime, and so of our duty to carefully evaluate the intentions of musicians whose lives (and livelihoods) have become entangled in conflict.

Acknowledgements

The idea for this article developed out of a long-term gramophone digitisation project at the Museum-Archive of Russian Culture, San Francisco, where Yves Franquien, Margarita Meniailenko and the rest of the staff offered tireless support. Supplementary research trips to the Amherst Center for Russian Culture, the Rogers and Hammerstein Archives of Recorded Sound and the Hoover Institution and Libraries were funded by the Institute of Slavic, East European and Eurasian Studies and the Institute of East Asian Studies at UC Berkeley. I benefitted from scintillating discussions of this research at the annual meeting of the Society for Music Theory in 2023 and at the Global Western Art Music Symposium at the University of Chicago in 2024, where David Fanning encouraged me to dig deeper into the Soviet press. Many thanks to the 2024–5 cohort of fellows at the Townsend Center for the Humanities, alongside Marié Abe and Edward Tyerman, who affectionately dissected early drafts. I am especially indebted to Nicholas Mathew, Maria Sonevytsky, Mary Ann Smart and the anonymous reviewers who offered insightful feedback in the final stages.