Introduction and objectives

This paper outlines the history of teaching Vulgar and Late Latin (LVLT) at universities in a single European country, Finland, from the mid-19th century to the present. In the latter half of the 20th century, LVLT grew into a relatively prominent part of Finnish university syllabi. We show how these syllabi aimed to transmit both theoretical and practical knowledge of LVLT to Latin students, and which texts and authors they actually studied.

We begin with a brief background to Finnish Latin teaching (Section 2). In the largely chronological Sections 3–7, we examine, on the basis of archival scrutiny, teaching at the University of Helsinki from 1853 to the present, the official Latin degree requirements at the same university from 1878 to the present and the impact of LVLT teaching, measured by the number of LVLT-themed master’s and doctoral theses. We focus on the University of Helsinki because it was Finland’s only university until 1919 and has been the most active site of LVLT teaching.

While extensive studies have been conducted on the history of learning in Finland (e.g. Tommila Reference Tommila2000–2002), LVLT research and teaching have received only sporadic attention in studies primarily focusing on other topics, most systematically in a study by Aalto (Reference Aalto1980). This oversight is all the more surprising since the view has prevailed in Finland and, apparently, in some scholarly circles abroad that Finnish Latin studies have been perceivably oriented towards LVLT. This image is probably largely due to the role played by epigraphy – particularly the many Vulgar Latin funerary inscriptions – in Finnish classical studies (Sihvola Reference Sihvola, Suvikumpu, Setälä, Sihvola and Keinänen2004, 210–217), to the international influence of Veikko Väänänen (e.g. Henry Reference Henry1998) and to the relatively strong presence of Finnish Latinists at the international Latin vulgaire – latin tardif conferences. Nor can one exclude the possibility that Finnish scholars benefitted from the collective prestige that – according to Hofmann and Szantyr (Reference Hofmann and Szantyr1965, 1) – accrued to the ‘Nordic countries’ in Latin historical linguistics in the first half of the 20th century, ‘under the aegis of E. Löfstedt’ (i.e. the Swedish scholar Einar Löfstedt the Younger, 1880–1955; see also Lindberg Reference Lindberg1987, 257; De Stefani Reference De Stefani2024–2025, 63).

We aim to assess to what extent such perceptions are warranted. Although the topic is primarily national, several points should resonate with other countries’ academic traditions and help clarify the global status quo of LVLT teaching, thereby paving the way for a better appreciation of its current and future challenges.

Background

Although located beyond the Roman world, Finland entered the Latin-literate European cultural sphere in the later Middle Ages. From that time, Latin has been taught in Finland, albeit always on a modest scale, reflecting the small proportion of the population with formal education. Finland – that is, the region long under Swedish and then Russian rule – remained demographically small, with few urban centres. With the rise of nationalism in the 19th century, the search for national identity turned to the Finnish-speaking past: unlike many countries in Southern and Western Europe, Finland had no Roman heritage to draw on, and the ancient Roman past (and at times later Latin cultural achievements) could not be woven into a national historical narrative.

Until 1630, Finland’s only educational institutions were town schools and the Cathedral School in Turku, which in that year became a gymnasium. In 1640, the gymnasium was transformed into a university, the Royal Academy of Turku, largely for the purpose of educating clergy and civil servants. Before then, higher education was pursued in Uppsala, Sweden, or at German universities. In the Middle Ages, when Catholic connections were strong, it was also fairly common to study in places such as Paris, though the numbers were small (Nuorteva Reference Nuorteva1997). The Chair of Latin (or eloquentiae) was among the original chairs created at the Academy of Turku in 1640. From the outset, Latin was subordinate to theology, and the chair often served merely as a stepping stone for ambitious professors to more prestigious posts within the Faculty of Theology. Furthermore, Latin instruction was primarily practical – teaching students to write and speak correctly – and for much of the university’s history the chair remained free from philological ambitions (Aalto Reference Aalto1980, 15–17). In the aftermath of the great fire that destroyed Turku in 1827, the Academy was closed and a new university, the Imperial Alexander University, was founded in Helsinki in 1828; Helsinki had been Finland’s capital since 1812.

Academic teaching and research in classical philology were also closely tied to the status of the classical languages in schools. The 1843 School Act divided schooling into primary schools, secondary schools and gymnasiums. In 1872, secondary schools and gymnasiums were merged into lyceums, where Latin and Greek were taught as the primary foreign languages. By 1914, however, only six classical lyceums remained (Aalto Reference Aalto1980, 28–29). The syllabi of urban schools largely resembled those in Central Europe until the 20th century, but the corresponding number of students studying Latin and Greek declined already in the 19th century. Nonetheless, the absolute number of those knowing Latin may have increased towards the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century as enrolments grew. At the university, all students in the Historical–Linguistic Department (Faculty of Humanities) studied Latin. It also remained a mandatory subject for theologians, alongside Greek and Hebrew, until quite recently, as university-level education is required for clergy in Finland. Until the 1850s, Latin was also the common language of theses. After independence in 1917, new universities were founded. Today, Latin is taught, in one form or another, at the universities of Helsinki, Turku, Jyväskylä and Tampere, the Åbo Akademi and the University of Eastern Finland; until recently it was also taught at the University of Oulu.

The origins: from eloquence to modern philology

This section examines the development of Latin teaching at the University of Helsinki from a rhetorically oriented study of literature to scientific classical philology. The period runs from 1853 – when the new and more scientific statutes of the university took effect and the first printed teaching programmes appeared – through the retirement of Professor Fridolf Gustafsson (1882–1920).

The university was initially small. In the early 1850s, it comprised five faculties and only 52 teaching posts; the Historical–Philological Faculty had eight professors, three lecturers and 10 docents. As the country developed economically and socially, the university grew significantly, especially from the 1880s onwards. Student and teacher numbers rose; by 1910, for example, the staff list already recorded 173 names. Latin, however, remained thinly staffed – usually a professor and a docent, the latter teaching the less advanced courses. Only around 1900 were two or more docents present annually. When such a title existed, the docent of Classical Philology (or Ancient Antiquities), taught lower-level courses in both Greek and Latin.

Johan Gabriel Linsén (1828–1848), the first professor eloquentiae et poeseos at the University of Helsinki, worked entirely within the traditional paradigm. Finland’s first internationally significant scholar of ancient studies was Professor Edvard Jonas Wilhelm af Brunér (1851–1870), who gained recognition for his research on Catullus (Väisänen Reference Väisänen and Brunér2016; Solin Reference Solin, Canfora and Cardinale2012b, 357). He improved Latin instruction both quantitatively and qualitatively, bringing Latin teaching at the University of Helsinki to an internationally competitive level (Aalto Reference Aalto1980, 174–175). Across the 19th century, the study of LVLT took shape in German-speaking universities: Vulgar Latin texts were initially the prerogative of Romance philology and Late Latin authors the focus of (reform-minded) classical philologists. However, although af Brunér followed international research, Finnish Latin instruction and research long focused exclusively on classical authors, accompanied by Plautus and Terence, and on instrumental training in Latin prose composition. The only exception were af Brunér’s 1868–1869 lectures on Cicero’s Letters to Friends (epistulae ad familiares), whose vulgar features necessarily invited comment in class.

Af Brunér wrote a new Latin grammar for schools and, with the professor of Greek literature, drew up plans for a philological seminar on the German (and Swedish) model; the seminar, however, was not established at the time (Väisänen Reference Väisänen and Brunér2016; Lindberg Reference Lindberg1987, 236–238). Ambitious degree requirements were recorded for the first time in the 1860s, including the complete works of most major classical authors. With such a small teaching staff, independent study must have played a significant role. The degree requirements prescribed only af Brunér’s own grammar for formal grammar instruction and included no history of the language (Aalto Reference Aalto1980, 38). After af Brunér, the professorship was held for 10 years by extraordinary professor Fredrik Julius Petersén (1871–1881), whose text-critical thesis De Martiano Capella emendando (1870) was among the first Finnish studies to focus on a Late Latin text.

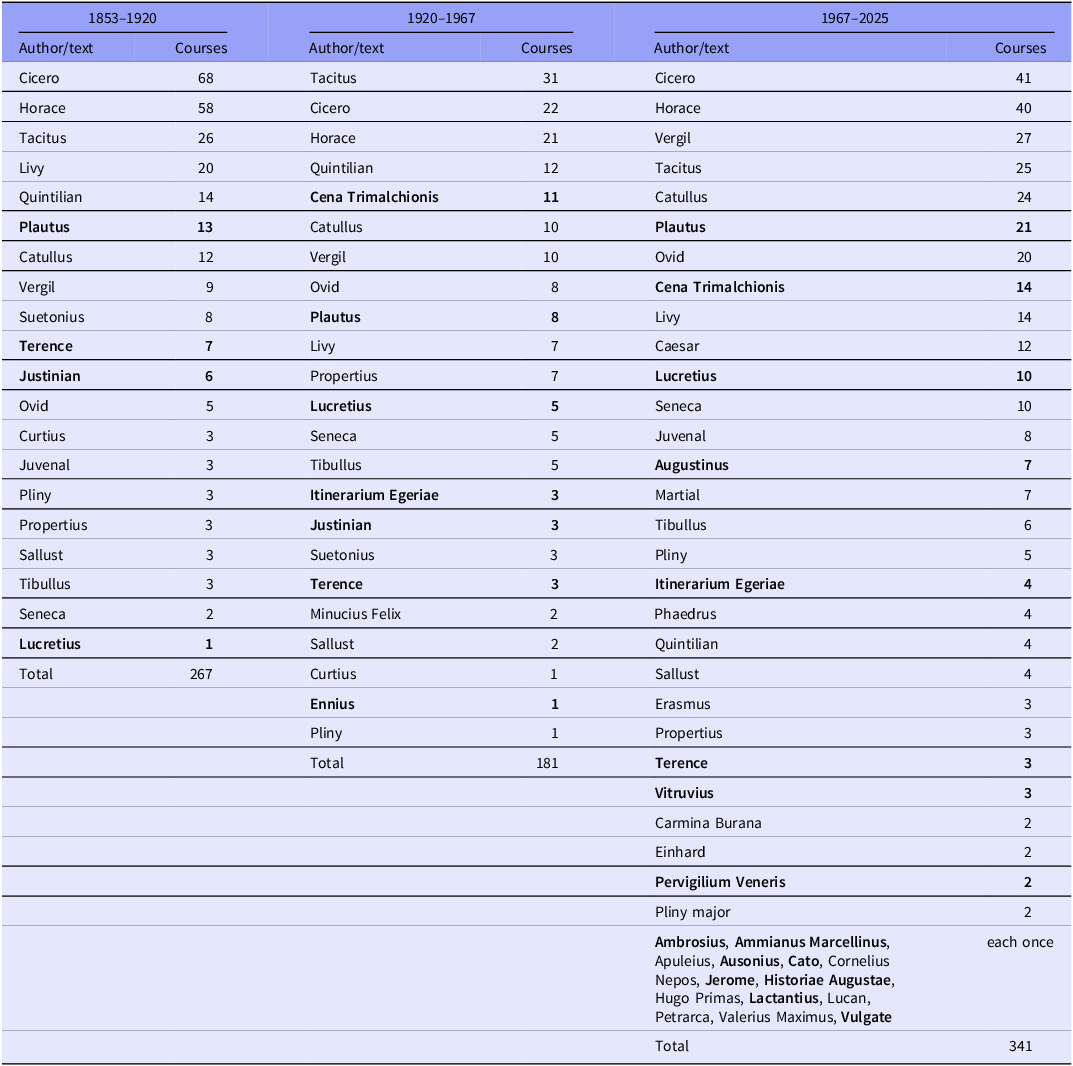

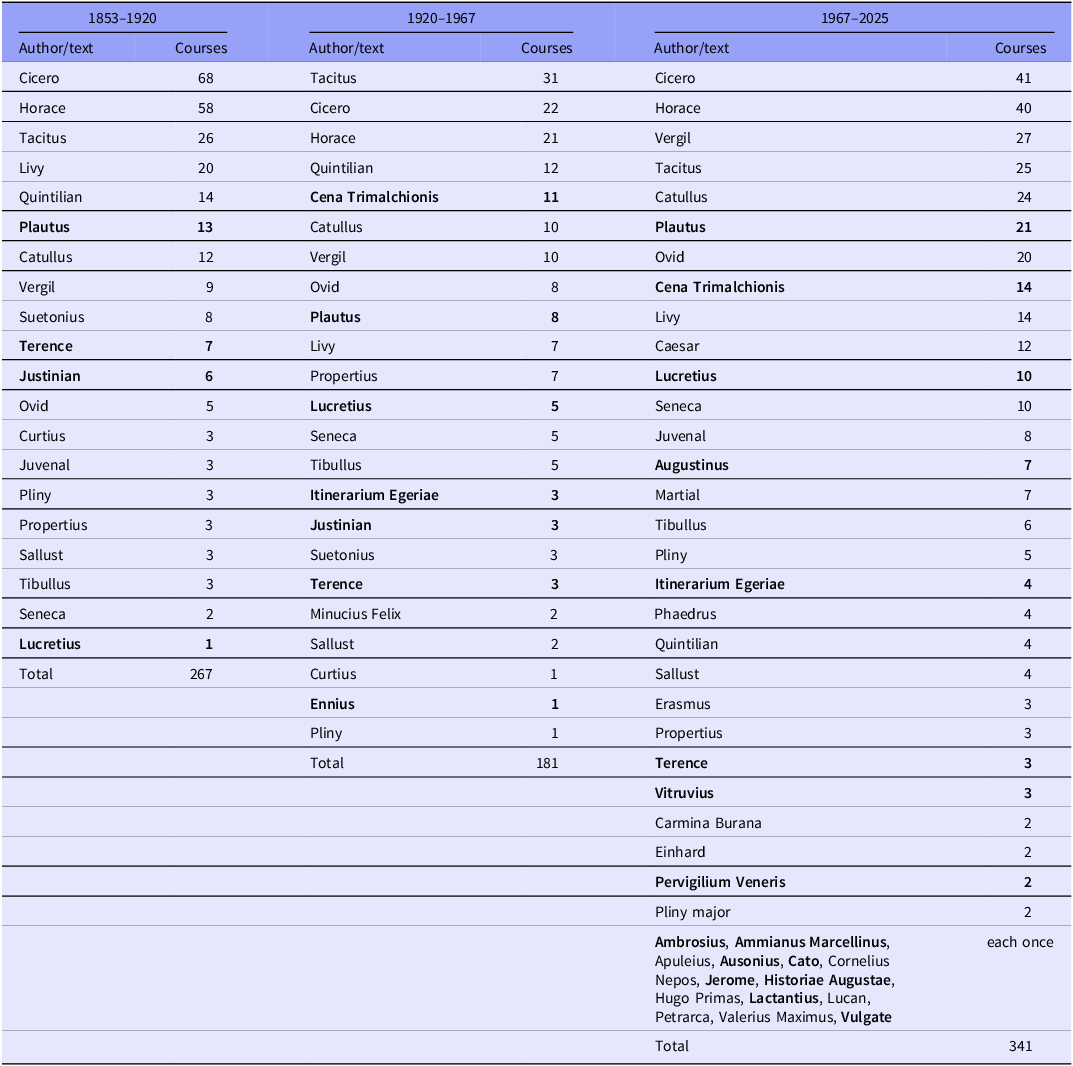

Table 1 reports how often particular authors are mentioned in the Roman literature teaching programme at the University of Helsinki from 1853 to 2025. Not all occurrences represent lecture courses; philological seminars sometimes also listed authors to be discussed. Conversely, not all authors actually studied were necessarily mentioned in the programme. For instance, docents sometimes lectured on authors requested by the students. It is also clear that the contents of the printed programme did not always materialise as planned.

Table 1. Authors mentioned in the Roman literature teaching programme at the University of Helsinki, 1853–2025

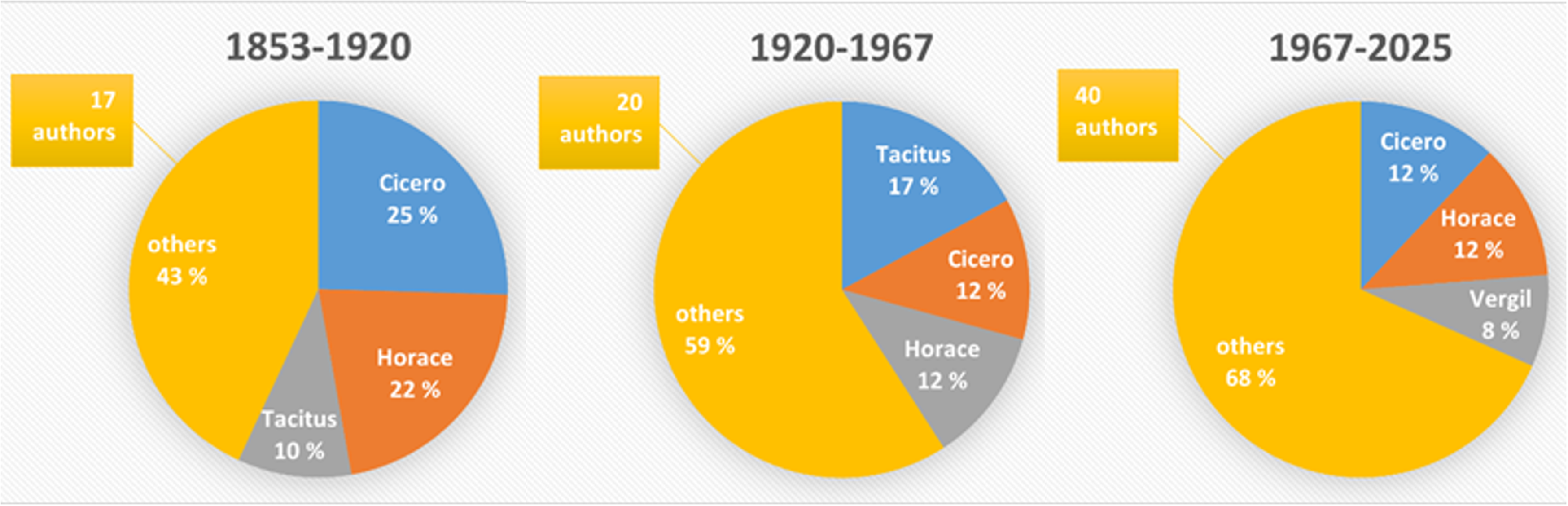

The first two columns of Table 1 list the 20 authors taught between 1853 and 1920. In prose, the perennial favourite was Cicero (68 mentions); in poetry, Horace (58). Representatives of historical prose included Tacitus (26) and Livy (20). Book 10 of Quintilian’s Institutio oratoria was offered 14 times over roughly 70 years, Plautus’ plays 13 times and Catullus’ poems 12 times. Owing to the rhetorical character of the discipline, the rhetorical and other scholarly works of Quintilian and Cicero were emphasised. However, Cicero’s speeches were the subject of only nine lecture courses, as students were expected to read them independently on the basis of their secondary-school education. By contrast, Plautus was probably lectured on frequently at the university, precisely because he was not included in the secondary-school curriculum.

It is useful to compare teaching programmes with degree requirements, which outline the ideal scope and content of the field. While the Helsinki degree requirements present a more rigid and prescriptive view of the canonical authors, they also reveal themes not taught as independent courses – such as literary history, grammar and, later, language history – the last of which was, along with (comparative) linguistics, a de facto condition for serious study of LVLT. The oldest known systematically structured and printed degree requirements date from 1878. Degree requirements also indicate to what level of the three-tier degree system (basic, intermediate and advanced studies) each author or area of knowledge was ideally assigned.

Until the 1901 requirements were implemented, all texts – apart from one play each by Plautus and Terence and the works of Tacitus – were strictly classical. In the 1901 requirements, excerpts from Justinian’s Institutiones appear in the basic studies, and they were regularly taught from the 1899–1900 academic year onwards. The law examination included selections from Justinian’s Institutiones (Aalto Reference Aalto1980, 61), and instruction in this text fell to Roman literature. For a long time, it was the only Late Antique text taught regularly.

From 1903, advanced studies included a ‘short course’ on epigraphy or palaeography, and from 1906 an alternative course on the Italic languages. A significant shift for the future of LVLT teaching occurred in 1914, when Latin historical phonology and morphology (according to Niedermann and Ernout) were included in the intermediate studies requirements, together with explicit mentions of syntax and stylistics. The first separate course on historical Latin phonology and morphology was taught by Docent Einar Heikel in 1915–1916. From 1914 onwards, the advanced studies requirements also included Rudolf Meringer’s Indogermanische Sprachwissenschaft and Friedrich Stolz’s Geschichte der lateinischen Sprache. However, Wallace Martin Lindsay’s comprehensive historical-comparative study of Latin morphology and syntax, Die lateinische Sprache: ihre Laute, Stämme und Flexionen in lautgeschichtlicher Darstellung (originally published in English in 1894, 660 pages), was recommended in a supplementary guidebook called Neuvoja (‘Advice’), which clarified the degree requirements as early as 1900, suggesting that students were expected to learn language history even before it was introduced in the printed requirements.

Alongside general study guidelines, Neuvoja detailed which authors, editions and commentaries were most suitable for students specialising in different fields, such as Classics, law or theology. For example, the 1907 Neuvoja recommended Minucius Felix’s Octavius and other Christian authors for theology students; for those in other disciplines, it suggested Pliny the Elder and (rather surprisingly) Celsus from the early Imperial period and Boethius from the 6th century – the last two probably for medicine and philosophy, respectively. These recommendations show that individual preferences have always been taken into consideration: alternative authors could be substituted by agreement with the examiner. Thus, the actual scope of study was broader and more varied than that reflected in formal degree requirements and teaching programmes.

The integration of linguistics and late non-classical and non-literary texts into the syllabus

The first texts outside the canon of classical authors – and, more broadly, the first non-literary texts – entered Finnish university research on Roman literature in the late 19th century and the classroom in the early 20th century. As international research increasingly emphasised a more comprehensive understanding of the ancient world, Finnish classical scholars also turned to previously marginal source types, such as inscriptions and, in Greek studies, papyri – sources that later became central to Finnish research on antiquity (Solin Reference Solin and Solin1998, Reference Solin, Härmä and Castrén2012a; Lindberg Reference Lindberg1987, 230). Because these sources demand sensitivity to linguistic variation, their rise in research – and, a little later, in teaching – led to systematic courses in historical Latin phonology and morphology.

The first stand-alone course on Latin inscriptions was taught by the docent of Roman antiquities in 1903–1904. In Greek Literature, however, inscriptions had already been treated in philological seminars in 1891–1892 and continued to appear occasionally thereafter. They may also have entered Latin teaching earlier than the official programmes indicate (Aalto Reference Aalto1980, 36; Solin Reference Solin and Solin1998, 5–9).

Inscriptions draw attention to the linguistic variation of ancient languages – something easily overlooked when focusing solely on canonised literary authors, especially in Latin. That said, the Latin inscriptions taught at Helsinki at an early stage were not necessarily late or vulgar, nor were such features always analysed explicitly in classes when present.

As noted above, the first university course in historical Latin phonology and morphology was offered in 1915–1916. Comparative Indo-European linguistics – covering contrastive analysis of Latin and Greek phonology, morphology and syntax – had, however, been offered annually since 1871–1872, thanks to Docent (later Professor) Otto Donner (1835–1909), a specialist in Sanskrit and comparative linguistics.

The linguistic approach took root in ancient Greek studies earlier than in Roman literature. The first Finnish study in historical phonology was Frans W. G. Hjelt’s (1819–1883) thesis De digammate (1844), inspired by comparative linguistics (Aalto Reference Aalto1980, 81; Solin Reference Solin and Solin1998, 3). Even Professor of Greek Literature Nils Abraham Gyldén (1847–1866), who otherwise focused on classical authors, wrote a study on absolute constructions in Greek and Latin and, in 1857–1858, lectured on general linguistics based on Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Heyse’s recently published System der Sprachwissenschaft (1856).

More significant in this respect was Jacob Johan Wilhelm Lagus (1821–1909), who served first as Professor of Oriental Languages and then of Greek Literature from the 1850s to 1880s. As early as 1854–1855, he lectured on the influence of other languages on Greek, and in subsequent years, he occasionally taught the history of the Greek language as well as syntax and morphology. In the 1878 Greek degree requirements, special emphasis was placed on syntax, and by the 1880s, knowledge of syntax was required, based on Einar Löfstedt the Elder’s Grekisk grammatik (1868), later superseded by other works. Textbooks in comparative linguistics were also introduced, including a volume on dialectal inscriptions in 1892.

At Helsinki, professors of Roman Literature up to Edwin Linkomies (1923–1963), together with Assistant Professor of Classical Philology Päivö Oksala (1953–1971), were primarily specialists in literature and aesthetics. The discipline was not renamed as Latin Language and Roman Literature until 1979, which helps explain why earlier teaching focused almost exclusively on literary exegesis. Even so, most Finnish Latinists of the 19th and early 20th centuries also published on topics that would now be classified as linguistic. Such questions appear particularly in theses, though this does not necessarily imply a sustained interest in linguistics or familiarity with its methods.

Gustafsson’s tenure (1882–1920) sought to bring Latin teaching up to European standards. Together with Professor of Greek Literature Heikel, he established a philological seminar and introduced the laudatur thesis, which became mandatory from the 1884 degree requirements onwards. The classical seminar enabled Latin students to benefit from the expertise of Heikel and other scholars in historical linguistics. Most students read both Greek and Latin, with some adding comparative linguistics and Romance philology – channels through which methods and perspectives from other language disciplines entered Latin research. Even so, seminar texts remained primarily classical and pre-classical (Plautus). According to Aalto (Reference Aalto1980, 152), Gustafsson’s dismissive attitude towards LVLT delayed its integration into Latin philology and meant that the field’s breakthrough came in Romance philology instead.

Only in the 1920s, after Gustafsson, did LVLT gain real prominence in Finnish Latin studies. The shift is reflected, for example, in Linkomies’s work on the ablative absolute and Karl Julius Hidén’s (1867–1925), docent of Roman Literature, research on case syntax in Arnobius (1921–1923). An important early LVLT scholar was Aarne Henrik Salonius (1884–1930; professor of Greek, 1929–1930), who published on the syntax, vocabulary and textual history of the Vitae patrum (1920), Passio Perpetuae (1921), Martyrium Petri (1925) and Petronius (1926, 1927). His research influenced university teaching during Linkomies’s early years. Finnish Latinists also closely followed advances in LVLT studies in Sweden, where Einar Löfstedt the Younger raised the field to international renown during the 1910s and 1920s.

Romance philology as a promoter of LVLT research and teaching

Romance philologists played a crucial role in launching and establishing the study and teaching of Vulgar Latin at universities beginning from the early 19th century onwards (Varvaro Reference Varvaro1968, ch. II–IV). The same was true in Finland, though the development took place later, towards the end of the century. The first explicit mention of Vulgar Latin in the University of Helsinki’s teaching programme appears in the academic year 1901–1902, within Romance philology. Docent Axel Wallensköld (professor of Romance philology 1915–1929) lectured on Vulgar Latin from the perspective of the Romance languages, presenting it as an introduction to the earliest Old French texts. From 1912–1913 through the 1930s, Docent of Southern Romance Languages, Oiva Tallgren-Tuulio (1878–1941) continued offering similar introductory courses. Romance philologists were therefore assumed to possess adequate Latin, and many studied at least some Roman literature.

Following German and French models, Finnish Romance philologists focused on linguistic history and the editing of mediaeval Romance texts. In this vein, Carl Gustaf Estlander (1834–1910), who had studied in Germany and France in the 1850s, introduced Romance philology to Finland. Later, Werner Söderhjelm, professor of Romance and Germanic Philology from 1898 to 1913, consolidated the field in the 1890s, establishing Romance philological research and teaching at Helsinki (Merisalo Reference Merisalo, Merisalo and Sovijärvi2023, 180–183). For a long time, Romance philology remained closely tied to Vulgar Latin, a link that weakened only after Väänänen’s tenure (1951–1972), as focus shifted gradually towards modern language usage.

Veikko Väänänen (1905–1997) remains the most internationally recognised Finnish LVLT scholar. His textbook Introduction au latin vulgaire (1st ed. 1961; later translated into Italian and Spanish) has served as a standard introduction for generations of students worldwide. Within the scholarly community, he is best known for his thesis Le latin des inscriptions pompéiennes (1st ed. 1937; 3rd expanded ed. 1966), as well as for numerous other publications on LVLT, historical linguistics and mediaeval French texts. His role as both researcher and teacher has been widely acknowledged (see, e.g. Solin Reference Solin, Härmä and Castrén2012a, Reference Solin, Canfora and Cardinale2012b). As professor of Romance Philology, Väänänen regularly taught historical Romance grammar in addition to more modern literary topics, though according to student accounts (Löfstedt Reference Löfstedt, Härmä and Castrén2012, 106) all his courses were at heart about LVLT. During his two directorships of the Finnish Institute in Rome in the 1960s, he also had a significant impact on the career paths of many Latin students and junior scholars.

The Finnish LVLT boom

The first Vulgar Latin texts to enter the Roman literature degree requirements – Itinerarium Egeriae (Peregrinatio Aetheriae) and Petronius’ Cena Trimalchionis – were introduced after Linkomies succeeded Gustafsson as professor in 1923. The requirements devised by Linkomies, which remained largely unchanged until his death in 1963, were the first to divide advanced studies into a literary and a linguistic track, a structure later expanded with additional tracks. This initial division seems to have been a public acknowledgement of the consolidation of language-historical and LVLT themes in the curriculum during Gustafsson’s final decades.

Training linguistically oriented advanced students required exposure to a maximally varied corpus of texts. In this way, the creation of the linguistic track contributed to the institutionalisation of LVLT courses within the teaching programme. At the same time, it also prepared the ground for the later expansion of LVLT in the 1960s and 1970s, since already in 1928 the track included the Itinerarium Egeriae, with Einar Löfstedt the Younger’s commentary, Diehl’s Altlateinische Inschriften (1909, 3rd ed. 1930), Ferdinand Sommer’s Handbuch der lateinischen Laut- und Formenlehre (1902), Carl Buck’s Elementarbuch der oskisch-umbrischen Dialekte (1905) and either Löfstedt’s Syntactica I (1928) or the Latin-related sections of Jacob Wackernagel’s Vorlesungen über Syntax (2nd ed. 1926) – all providing students with solid preparation for LVLT research. Under Professor Kajanto, some of these works were replaced by such texts as Friedrich Stolz, Albert Debrunner and Wolfgang Schmid’s Geschichte der lateinischen Sprache (4th ed. 1966), Alfred Ernout’s Recueil de textes latins archaïques (2nd ed. 1957), Väänänen’s Introduction au latin vulgaire and Löfstedt’s Late Latin (1959).

Petronius’ Cena Trimalchionis was included in intermediate studies, which lacked separate tracks, so all students were expected to read it. It was also the first LVLT-related text taught in the Roman literature curriculum, beginning in 1928–1929 with Linkomies’s lectures. Early in his professorship, Linkomies also incorporated inscriptions into his teaching, and from the 1920s–1930s, many Finnish classical scholars had experience with epigraphic material (Solin Reference Solin and Solin1998, 21–26). In addition to Linkomies, Edvard Rein, extraordinary professor of Greek literature (1925–1930), taught inscriptions in 1927–1928, and Docent of Classical Philology Magnus Hammarström lectured on them from 1929–1930 onwards. Linkomies also taught Minucius Felix’s Octavius, which he had previously studied, and even offered a course on Latin historical phonology and morphology in 1932–1933.

In Linkomies’s time, Roman literature still maintained some distance from Romance philology. While Cena Trimalchionis fit the discipline’s profile, the Vulgar Latin texts of Late Antiquity did not enter the lecture programme until the 1960s. The Itinerarium Egeriae – already listed in the degree requirements – and courses entitled ‘Selections of Vulgar Latin texts’ were introduced into Roman literature teaching only then, and they remain in the curriculum today, except for a brief interruption between 2017 and 2025.

Linkomies’s political and administrative commitments kept him frequently on leave during the 1940s and 1950s. The war years brought major downsizing at the university: many students and younger scholars served at the front, and resources were scarce. Figure 3 in the following section illustrates the sharp decline in Latin faculty numbers in the 1940s, a situation that only began to improve in the late 1950s. Throughout the early 1950s, Roman literature courses were taught almost exclusively by Linkomies and Assistant Professor Päivö Oksala. Only in 1955 was a teaching assistant post created and funds for docent teaching restored.

Staffing gradually improved in the following years. A lectureship was established in 1963, but teaching resources continued to fluctuate. From 1956 to 1963, while Linkomies served first as rector and then as chancellor of the university, the professorship was held by Oksala, who continued to emphasise the discipline’s literary and aesthetic orientation. Much teaching time was devoted to preparatory courses for the mandatory pro exercitio examination, required of all students in the Historical–Linguistic Department of the Faculty of Humanities. In the 1960s, 1,500 to 2,000 students enrolled in these courses annually, as enrolments at the university soared with new educational policies and the postwar baby boom – in stark contrast to the small number of faculty members (Pekkanen Reference Pekkanen1997).

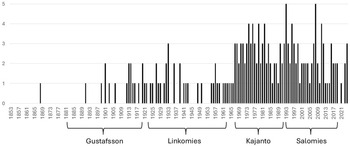

The appointment of Iiro Kajanto as professor in 1967 marked the moment when the potential for LVLT studies, long building, took concrete form in both teaching and research. Kajanto himself did not specialise in LVLT as such, but he knew the field well and integrated it into his epigraphic and onomastic research. He also actively supported LVLT teaching, frequently lecturing on Vulgar Latin texts and linguistic history. According to Solin (Reference Solin and Kajanto2019), Kajanto’s most lasting contribution to Finnish classical studies was his investment in doctoral training, which had previously received little attention. His efforts were crucial in expanding LVLT research, leading to what might be called an academic boom from the late 1960s to the 1990s. Students at the time recall that Helsinki was widely regarded as the place to study Vulgar Latin (p.c. Martti Leiwo and Outi Merisalo). Figure 1 illustrates the rise in LVLT courses from 1967 onwards. As a result, Finland gained an active pool of researcher-teachers with significant LVLT expertise, which shaped university teaching for decades (Figure 3).

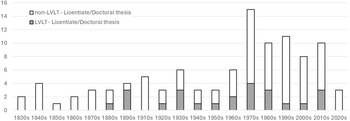

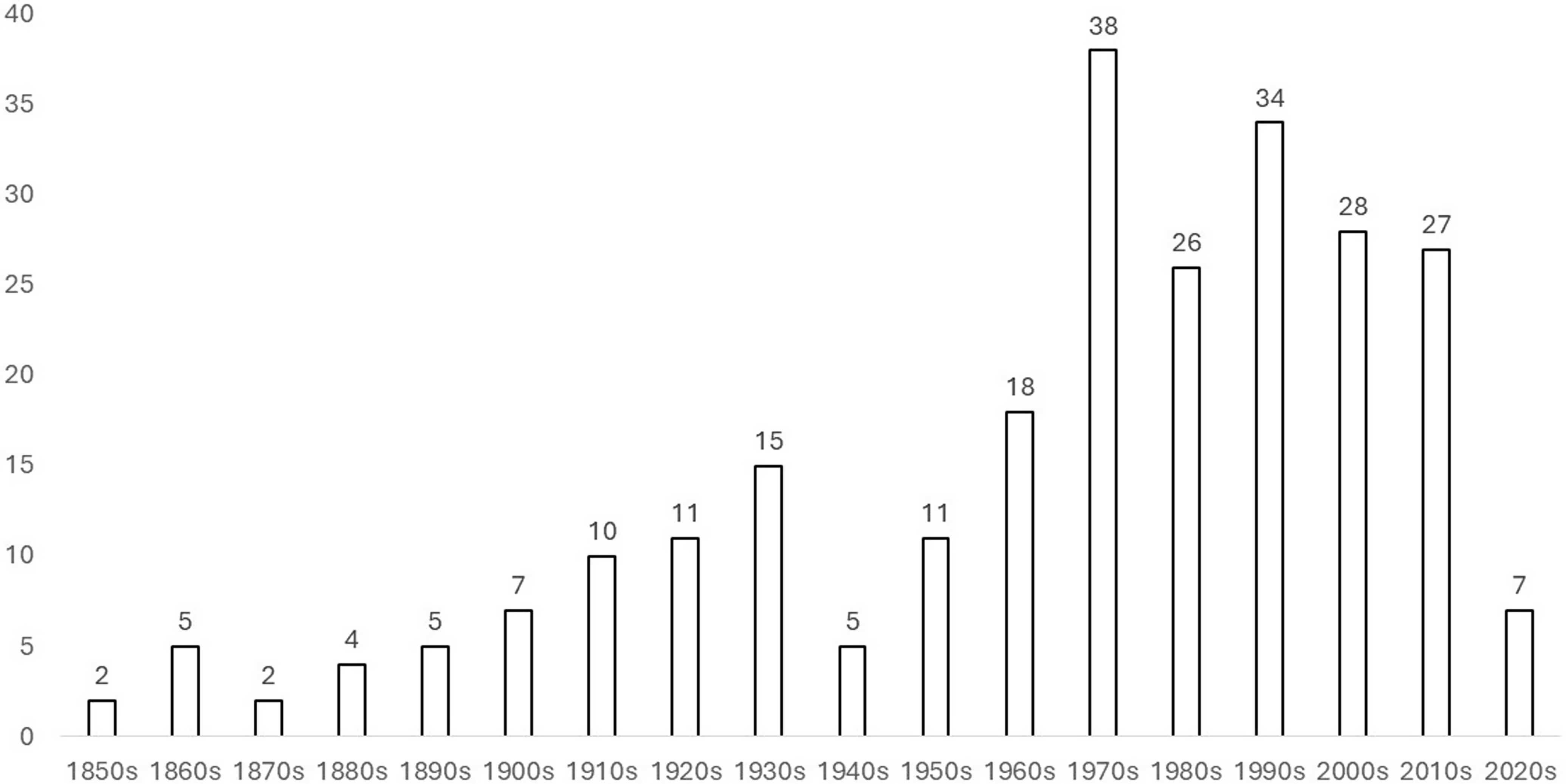

Figure 1. LVLT courses (excluding Plautus, Terence and Lucretius) taught at the University of Helsinki between 1853 and 2025, by academic year, and the tenures of long-term professors.

This boom was partly due to a large recruitment base. In the 1960s, the number of Latin students at Helsinki was at its peak: 400–500 active students annually. Numbers fell sharply in the early 1970s, however, after the compulsory pro exercitio examination – which had directed students to Latin – was abolished for most subjects. This change also reduced the popularity of Latin in schools. In the 1960s, approximately 100 students completed basic studies annually, around 10 progressed to the intermediate grade, and only a handful reached the completion of the advanced studies (Pekkanen Reference Pekkanen1997). Latin thus functioned mainly as a popular minor subject. In later decades, the proportion of major students increased, although minors have always been the majority. A similar declining trend can be observed in many other countries, driven by comparable societal pressures and educational reforms.

From the 1950s onwards, and especially during the 1960s and 1970s, many young scholars emerged at the University of Helsinki whose research was tied, directly or indirectly, to LVLT. Their interest and expertise ensured that LVLT teaching continued not only in Helsinki but also at other Finnish universities – for example, in Anne Helttula’s work in Turku and Jyväskylä. After Kajanto, the chair of Latin Language and Roman Literature passed in 1993 to Olli Salomies (b. 1951), who, like Kajanto, specialised in epigraphy and onomastics. From the 1980s, he taught courses on classical and post-classical authors, Plautus and epigraphy, and occasionally Late Latin texts, though not with a primary focus on Vulgar Latin or linguistic history. He did, however, teach Italic languages in 2001–2002 and 2009–2010. Some scholars active during the boom period, such as Heikki Solin (b. 1938) – arguably Finland’s most internationally renowned classical scholar today, also specialising in epigraphy and onomastics – continue their research to this day.

During Kajanto’s tenure and the early years of Salomies’s professorship, Helsinki’s degree requirements continued to diversify, reflecting the increasingly pluralistic nature of classical studies. By the 1990s, the advanced studies had expanded to six specialisation tracks. The core LVLT-related content and course literature, however, remained largely unchanged. Instead, the breadth of teaching expanded, with courses on, for example, Vitruvius, Augustine and the Historia Augusta added alongside the now traditional LVLT texts, such as Cena Trimalchionis and Itinerarium Egeriae.

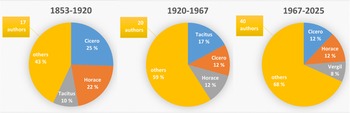

Figure 2 presents three pie charts illustrating the distribution of courses devoted to specific authors or texts in Helsinki’s Latin teaching programme from 1853 to 2025. The first chart represents the period from 1853 to the end of Gustafsson’s term, the second corresponds roughly to Linkomies’s professorship, and the third covers the professorships of Kajanto, Salomies and Anneli Luhtala (2020–2024). The most striking feature is the increasing diversity of authors and texts taught. While the top three – Cicero, Horace and Tacitus (and even the top 10 authors, see Table 1 above) – have remained fairly stable, a wide range of additional authors and texts has emerged alongside these canonised figures.

Figure 2. Distribution of courses dedicated to specifically named authors or texts in the University of Helsinki’s teaching programme in the years 1853–2025, across three time periods (top three authors vs. others).

No discussion of the Finnish LVLT boom would be complete without acknowledging the role of the Finnish Institute in Rome (Institutum Romanum Finlandiae, founded in 1954), which has been pivotal in Finnish classical research and teaching. This foundation-based institute played a central role in promoting LVLT research, particularly in the latter half of the 20th century, as many of its directors specialised in epigraphy, an area that often intersects with LVLT studies. From its very inception, the institute has complemented and enriched university research and teaching, providing a dynamic environment where scholars and students from different fields and career stages can engage in dialogue. In addition to leading annual introductory and advanced courses, each director forms a research group of Finnish students who spend about a year investigating a broad research topic set by the director and then publish their findings collectively.

With the support of the institute, epigraphy and onomastics – a closely related field – became core areas of Finnish classical scholarship, along with the philological skills required to study ancient languages and writing practices. Their prominence was further facilitated by the fact that Finland already had scholars with expertise in epigraphy from earlier decades, who were able to commit to longer research stays in Rome (Sihvola Reference Sihvola, Suvikumpu, Setälä, Sihvola and Keinänen2004, 210–213; Merisalo & Vainio Reference Merisalo, Vainio, Merisalo and Vainio2007; Solin Reference Solin and Solin1998).

Epigraphy gained a strong foothold at the institute early on, thanks especially to the research projects of its directors in the 1950s and 1960s: Henrik Zilliacus, professor of Greek Literature at the University of Helsinki, director in 1956–1959; Veikko Väänänen, director in 1959–1962 and in 1968–1969; and Jaakko Suolahti, professor of General History at the University of Helsinki, director in 1962–1965. Later directors also pursued epigraphic projects, among them Heikki Solin (1976–1979) and Anne Helttula (1989–1992) (see Solin Reference Solin and Solin1998, 26–43; Sihvola Reference Sihvola, Suvikumpu, Setälä, Sihvola and Keinänen2004, 210–222, 237–245, 266–267). By contrast, Veikko Litzen’s term (1983–1985) focused on the cultural transformations of Late Antiquity, with participants working on Late Antique literature. Of these terms, Väänänen’s two proved particularly formative for Finland’s LVLT research and teaching boom: his courses at the institute directly shaped the careers of many classical philologists. Helttula (1942–2024) went on to make lasting contributions to LVLT teaching in Finland at the universities of Helsinki, Turku and Jyväskylä (Merisalo & Vainio Reference Merisalo, Vainio, Merisalo and Vainio2007). Similarly, Reijo Pitkäranta (b. 1945) – who taught numerous LVLT-related courses at Helsinki from the 1970s to the 2010s – was part of Väänänen’s research group during his second directorship.

From boom to decline? Developments in recent decades

Between the late 1960s and mid-1980s, the University of Helsinki offered at least two, and often three or four, LVLT-related courses each year. Thereafter provision became more uneven, though it fell significantly only in the last few years (Figure 1). Since 2020, the permanent teaching staff has consisted of only one professor and one university lecturer. In years when no doctoral students or postdocs with teaching duties have been available, it has been difficult even to organise basic grammar courses and core text courses on major authors.

Until the end of the 20th century, degree requirements and teaching were largely determined autonomously by the staff. In the 21st century, however, efficiency-driven education policies have increasingly shaped Finnish universities. In the interest of shortening graduation times, degree requirements have been significantly reduced and staff numbers adjusted accordingly. The first major educational reform to affect Finnish university curricula was the pan-European Bologna Process, initiated in 1998. At the University of Helsinki, the most significant changes to the Latin degree requirements came into force in 2005. The process aimed to standardise European higher education degrees by defining the abilities they convey in terms of competences to be taught. This led to a restructuring of Latin studies at Helsinki: several basic-level courses (such as morphology and syntax exercises, metrics and all text courses) were moved to intermediate and advanced studies, while some previously required advanced-level material was eliminated altogether. Similar reductions in curricula and staff are reported from many countries traditionally strong in Latin. In Germany, for example, where Latin is still widely taught in schools, the total number of professorships in Latinistik and Mittel- und Neulatein sank by 23% (74 to 57) between 1997 and 2025 (Portal Kleine Fächer 2008–2025).

A far more radical reform than the Bologna Process was the University of Helsinki’s own streamlining programme, the infelicitously named Big Wheel programme (Iso pyörä), carried out in 2015–2017. Officially, the reform aimed to harmonise degree programmes, speed up student throughput and enhance graduate employability. In practice, however, when coupled with major education budget cuts at the time, the Big Wheel has functioned largely as a cost-saving measure (Scott Reference Scott2017; Metsäaho Reference Metsäaho2017). More recently, in 2022, the Faculty of Arts further reduced the degree requirements for advanced Latin studies from 95 to 75 credits, citing the same justifications as for the Big Wheel.

As a result of the reforms, the master’s degree in Latin today requires only 24 exams, compared with 53 before the Bologna Process – a 55% reduction. Previously, students had to take exams on at least 16 different Latin texts/authors, often more depending on their study track; now only six text courses are mandatory, with the option to take up to nine. Since the contents of a single course leading to an exam has remained essentially unchanged, it is fair to conclude that completing a master’s degree in Latin at the University of Helsinki now entails roughly half the work required in the early 2000s. Inevitably, everything beyond the core subject matter has been dropped from the requirements and from teaching. The impact of these reductions on students’ Latin competences and their ability to learn LVLT is discussed in Korkiakangas [Reference Korkiakangasforthcoming].

No compulsory course dedicated to LVLT remains in the post-Big Wheel degree requirements, although Hilla Halla-aho still lectured on Cena Trimalchionis in 2017–2018 under the title ‘Post-Classical Latin’. Peregrinatio Egeriae was last taught in 2009–2010, and the final survey course on selected Vulgar Latin texts in 2008–2009. Additionally, Martti Leiwo, university lecturer in Classical Philology and a specialist in historical sociolinguistics, regularly included Vulgar Latin texts in his courses on Latin historical phonology and morphology until his retirement in 2018. More recently, Timo Korkiakangas has incorporated Vulgar Latin texts into courses on the history of Latin in 2020, 2024 and 2025. Since LVLT has not recently been a central research focus of the professor or university lecturer, its teaching has largely depended on externally funded doctoral students and postdocs. The new 2026–2030 degree requirements, however, reintroduce an optional advanced course on ‘Latin texts reflecting social and diachronic variation’, with a literature list including Cena Trimalchionis and Itinerarium Egeriae.

Thanks to its long tradition in Helsinki, LVLT nonetheless remains partially embedded in the curriculum. The two extant Latin history courses – on the social history of Latin and on its historical phonology, morphology, syntax and lexicon – continue to include LVLT sources. Students taking these courses as independent exams must also read, among other works, József Herman’s Vulgar Latin (translated from French by Roger Wright, 2000). LVLT may also be, and occasionally has been, included in survey courses on non-classical, Mediaeval and Christian Latin.

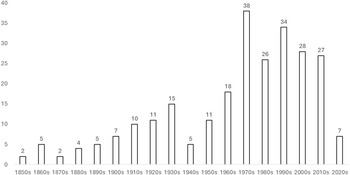

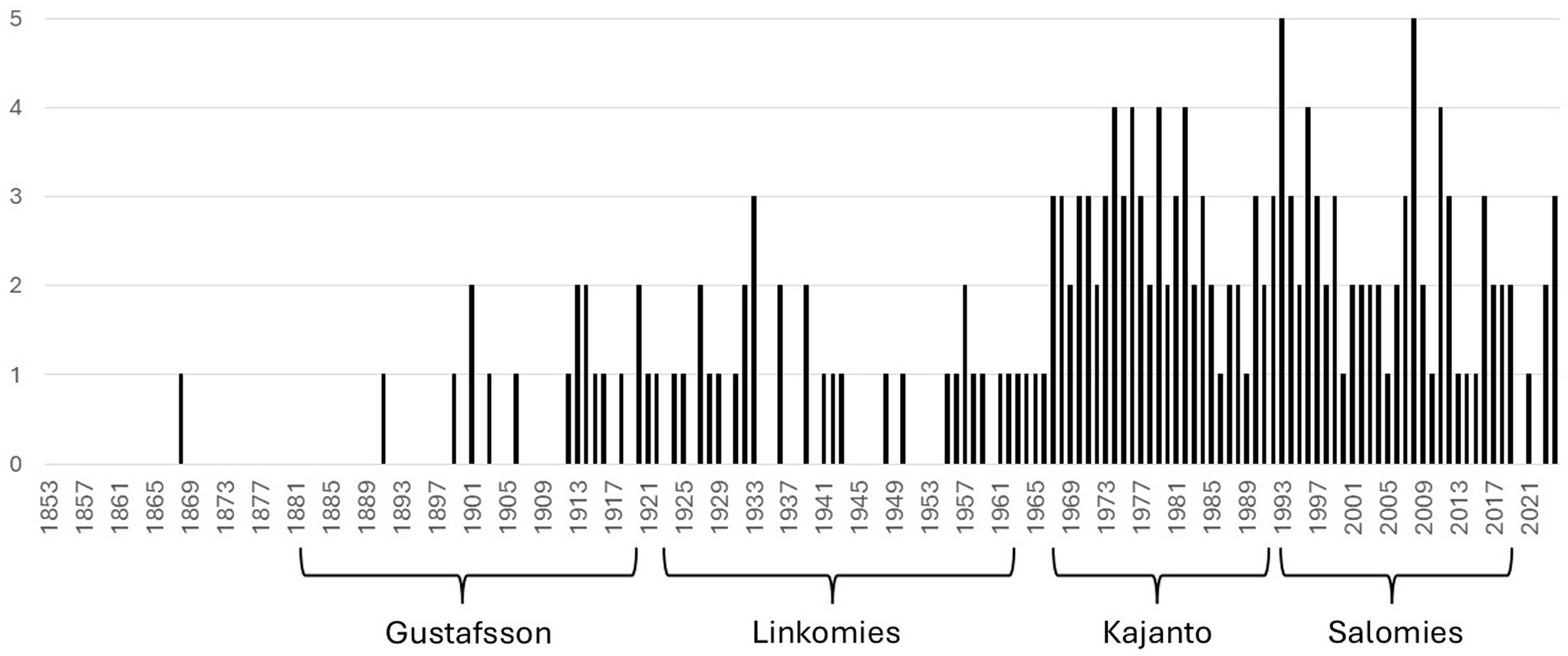

This ‘submerged’ continuity is possible because Finnish Latin scholars still generally possess solid competences in LVLT, even if it is not their research focus. From the 1960s through at least the 1990s, LVLT seems to have been so thoroughly integrated into Latin instruction at the University of Helsinki that it could hardly be ignored. As Figure 3 shows, since the 1970s, a strikingly large number of researcher-teachers have offered LVLT-related courses: in that decade alone, as many as 38 different individuals taught at least one such course. This high level of involvement continued into the 2010s. For the 2020s, the data extend only to the academic year 2024–2025, but current and expected staffing levels suggest that the total number of LVLT instructors for the decade will not exceed 10.

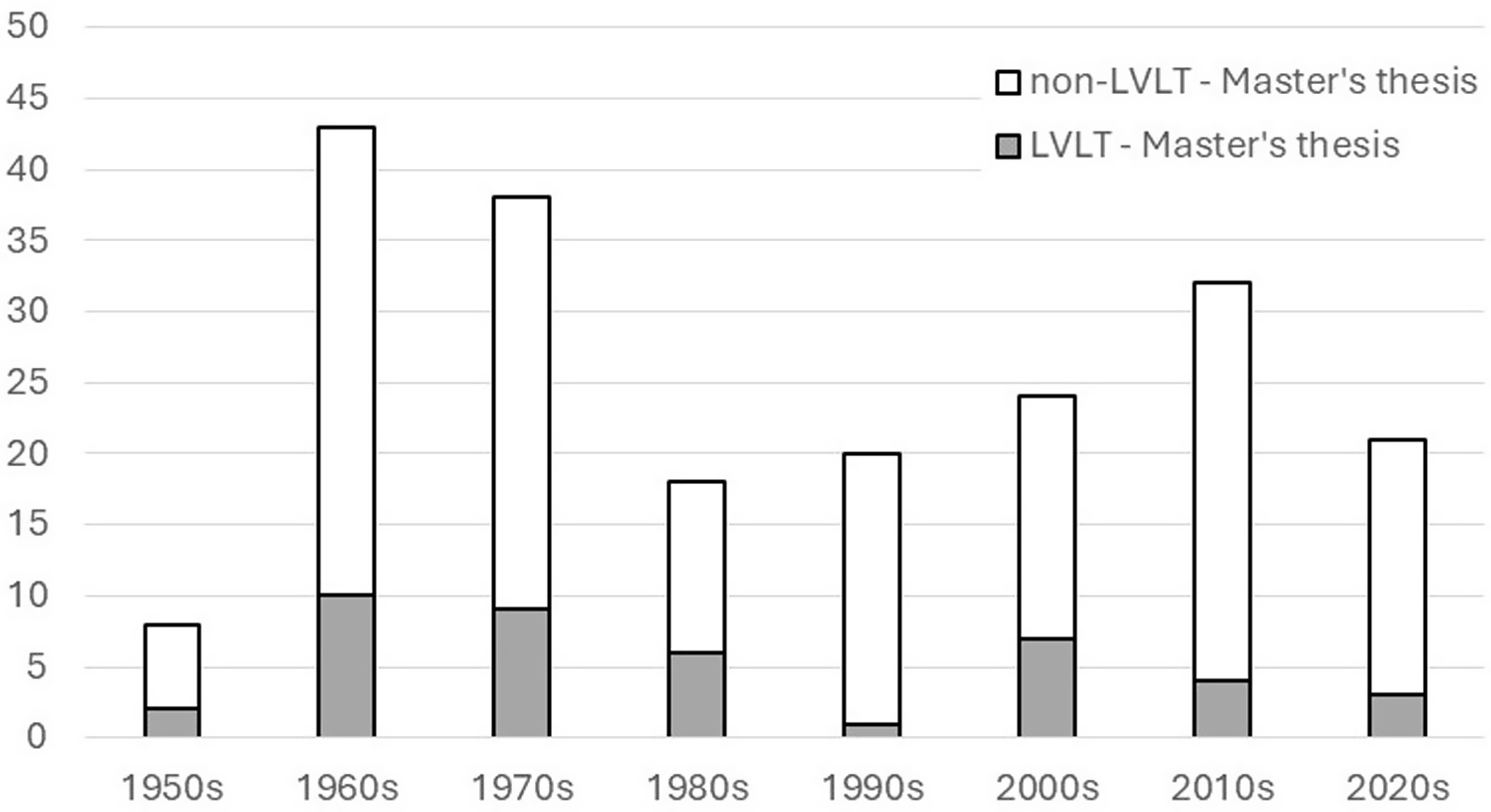

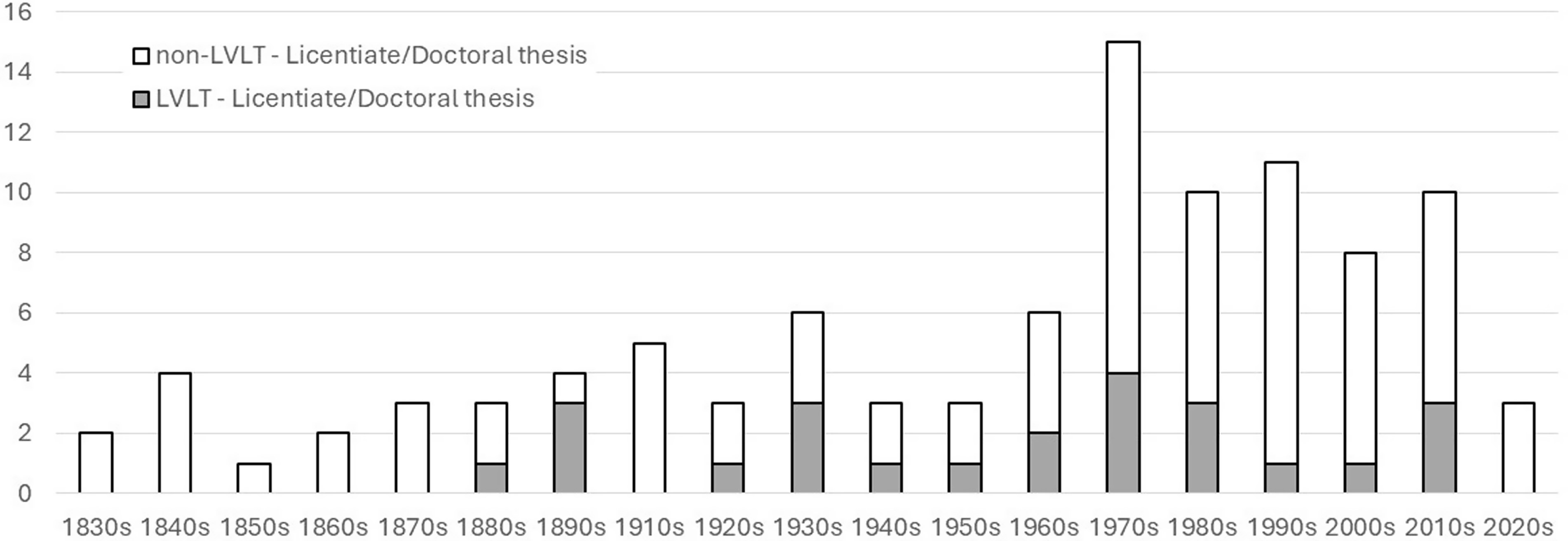

LVLT themes also continue to appear in academic theses, though it is too early to evaluate developments in the 2020s. Figures 4 and 5 show the numbers of all Latin-related theses completed at the University of Helsinki per decade, distinguishing between those that address LVLT topics and those that do not. A total of 306 theses from 1832 to 2024 have been recorded in the Helka catalogue of the University of Helsinki Library. This figure includes 102 doctoral theses (24 of them licentiate theses from the 1960s to 1990s) and 204 master’s theses (including 26 so-called laudatur theses by students minoring in the subject). The master’s thesis (pro gradu) system was introduced in the 1950s. No comprehensive records exist for the previous Candidate of Arts (filosofian kandidaatti) theses from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, so these are excluded from this analysis.

Figure 3. Number of researcher-teachers teaching at least one LVLT-related course at the University of Helsinki per decade.

Figure 4. Number of doctoral and licentiate theses on Latin at the University of Helsinki per decade (LVLT vs. non-LVLT).

Figure 5. Number of master’s theses (pro gradu theses, including laudatur theses) on Latin at the University of Helsinki per decade (LVLT vs. non-LVLT).

Although LVLT scarcely appeared in the official Roman literature curriculum of the late 19th century, it was nonetheless well represented in doctoral research: four out of seven theses published in the 1880s to 1890s treated LVLT topics, and – except for the 1910s – roughly one-third of theses per decade addressed LVLT until the 1980s (Figure 4). Professor Gustafsson encouraged linguistic themes in his seminars, which often required the use of LVLT texts; some seminar papers later evolved into doctoral theses. However, overall doctoral output at Helsinki was modest, and, as with course provision (Figure 1) and staffing levels (Figure 3), the promising growth of the 1930s was disrupted by the war years and their aftermath.

The rise in doctoral training and student numbers in the 1960s directly increased both doctoral and master’s theses. Not all master’s theses completed in the 1950s, however, have been duly catalogued in the University Library database, so the 1950s bar in Figure 5 may slightly underestimate the total. Conversely, the 2020s bar is unusually high because students who had begun their studies under the pre-Big Wheel requirements were obliged to finish by autumn 2020. In that year alone, a record 16 Latin-related master’s theses were completed. Since then, only four master’s theses have been submitted, reflecting the decline in student enrolments. Admission policies were revised in the 2010s, reducing the intake of students in Classical Languages. In some years, only a handful of new Latin majors were admitted, and in no year has the number exceeded 10.

The proportion of LVLT-related master’s theses is lower than at the doctoral level, which is understandable given that LVLT requires specialised linguistic expertise. Since every student must write a master’s thesis, many opt for less demanding, non-linguistic topics. Despite LVLT’s presence in teaching, many students likely feel more comfortable with Classical Latin literature, which has always formed the core of Latin instruction (Figure 2). Moreover, ancient cultural history and even material culture are part of Latin degree programmes in Finland and thus appear in theses as well. Of the 306 Latin theses completed at Helsinki, 66 (22%) address LVLT, but the share rises to 60% (50 out of 84) when only linguistic theses are counted.

For comparison, at the University of Jyväskylä, where LVLT instruction was especially prominent during Anne Helttula’s term as university lecturer (1997–2007), 11 of 36 Latin-related master’s theses (30%) and 7 of 15 linguistic theses (50%) concern LVLT themes. Only one of Jyväskylä’s five licentiate theses and none of its seven doctoral theses address LVLT. The number of Latin majors at Jyväskylä has always been small. At the University of Turku, where full records of Latin theses exist only from 1972, 4 of the 65 master’s theses (6%) pertain to LVLT, and no licentiate or doctoral theses do. These figures suggest that the strong LVLT focus in Helsinki influenced students’ later research choices. In Jyväskylä, the effect was likely even stronger: as sole Latin teacher, Helttula’s research interests probably influenced student work directly – much as Professor Tuomo Pekkanen’s (1975–1999) interest in Neo-Latin is reflected in the theses written during his tenure at Jyväskylä.

No clear long-term trend can be seen in the relative proportion of LVLT theses to all Latin theses completed at Helsinki since the 1960s. However, LVLT-related doctoral theses were few in the 1990s and 2000s and LVLT-related master’s theses in the 1990s and 2010s. Drawing definitive conclusions is complicated by the exceptionally high number of theses completed in 2020, noted above. At present, at least two doctoral theses on LVLT themes are underway in the Latin and Roman Literature discipline at the University of Helsinki, while no master’s theses on the topic are currently being prepared. The coming years will show to what extent Helsinki’s LVLT tradition will endure.

Conclusions and international comparison

This article has outlined the history of LVLT teaching in Finnish universities, focusing on the University of Helsinki, the largest and oldest existing university in the country with its reputedly LVLT-oriented Latin Language and Roman Literature discipline. Archival sources on teaching programmes, degree requirements and theses were examined alongside previous studies on the history of learning in Finland. Our international comparison remained more limited than initially hoped, as we did not find archival studies of similar depth elsewhere.

As in most countries, Latin instruction in Finland centred heavily on classical authors until the end of the 19th century, with an emphasis on rhetoric and literary analysis. The gradual incorporation of linguistic approaches, non-classical texts and epigraphic material – closely following international models – marked a shift towards a more scientific, historical–philological curriculum. This transition laid the foundation for the later expansion of LVLT studies at the University of Helsinki.

The broadening of the canon beyond the ‘golden’ authors occurred at different times across Europe. In many European universities, the division between the newly emerging Romance philology and the literary and rhetorical Latin studies, which evolved into scientific Classical philology during the 19th century, determined the extent and timing of the inclusion of LVLT texts – initially regarded as the domain of Romance studies – into Latin curricula. In some universities, this inclusion never occurred, as their Latin studies kept a focus on classical literature.

Because extensive archival work on teaching programmes and degree requirements would be required, precise information about the timing of this change is often lacking. In Helsinki, it seems to have occurred almost simultaneously with Sweden, perhaps because Finnish Latinists, all of whom spoke Swedish as either their mother tongue or their second language, closely followed Swedish developments. Alongside Sweden, the countries that most strongly influenced Finnish Latinists and Romance philologists were Germany and France. Both played a central role in the development of modern Classical and Romance philology and, for this reason, also pioneered LVLT instruction (Swiggers Reference Swiggers, Burkhardt, Steger and Wiegand2001, 1274–1279). At the University of Bonn, Friedrich Diez (1794–1876), the founder of Romance philology, was teaching Vulgar Latin as an individual course as early as 1836–1837, and it can be assumed to have become a regular part of courses and seminars on the earliest Romance literature at all universities (Baum Reference Baum and Hirdt1993, 893; Christmann Reference Christmann1985, 24–25).

In Sweden, LVLT texts – especially Late Latin literature – became a subject of keen interest during the tenure of the Latinist and Indo-Europeanist Per Persson, professor of Latin language and literature at the University of Uppsala from 1895 to 1922 (De Stefani Reference De Stefani2024–2025, 62–63). With Einar Löfstedt the Younger’s (1880–1955) long career in research and teaching (professor in Lund, 1913–1945), the linguistic study of LVLT texts became a hallmark of Swedish Latin scholarship, with several LVLT researchers remaining active until the 1960s. The emergence of this ‘Swedish school’ is reflected in doctoral dissertations on Latin authors published in Sweden: while only four Swedish dissertations between 1855 and 1890 dealt with Late Latin authors, the figures rise to 5 out of 33 in 1890–1910 and 40 out of 60 in 1910–1940 (Josephson Reference Josephson1897, 307–309; Nelson Reference Nelson1911, 109–110; Tuneld Reference Tuneld1945, 260–262). However, the heyday of the Swedish school was largely over by the time of the Finnish LVLT boom, although it ensured that LVLT was established in most Swedish university Latin curricula. Yet, as far as we know, in recent decades little LVLT teaching has been offered in Swedish universities, except at Uppsala, where Professor Gerd Haverling continued the teaching of Late Latin until recently.

In Finland, as in Germany and France, Romance philologists initiated both the research and teaching of LVLT. In Sweden, however, Romance philology was not similarly connected to the bloom of LVLT studies. At the University of Helsinki, the first mention of Vulgar Latin appears in the teaching programme for Romance philology in the academic year 1901–1902, while it entered the degree requirements for Roman Literature in the 1920s and was taught with varying frequency thereafter. A notable step was the creation of the linguistics track in 1928 as part of the advanced studies requirements, which included several foundational works of LVLT scholarship.

After the nadir of the wartime and postwar years, the latter part of the 20th century saw a remarkable increase in LVLT teaching and research in Finland, culminating in what may be described as a boom from the late 1960s to the 1990s. Key figures such as Veikko Väänänen and Iiro Kajanto were central to integrating LVLT into the Finnish academic landscape – Kajanto within the Roman Literature discipline at Helsinki and Väänänen, a professor of Romance Philology, largely through his role as the director of the Finnish Institute in Rome, which became an epicentre of Finnish research on epigraphy and LVLT.

This period also saw the expansion of doctoral training, with many young researchers emerging from Finnish universities to contribute to LVLT scholarship. The boom coincided with, or slightly postdated, a comparable phase of rapid growth and institutionalisation in many European and some American universities – except in Sweden, where the development had been precocious. LVLT was regarded as a new field that took shape over the course of the 20th century and found its institutional niche in certain universities, as suggested by the establishment of the Latin vulgaire – Latin tardif conferences in 1985 and a dedicated publication series (https://dlfc.unibg.it/it/ricerca/strutture-ricerca/associazioni-accademiche/societe-internationale-pour-letude-du-latin). However, the degree to which LVLT became embedded in the Latin curricula often depended on individual faculty members’ academic backgrounds and personal scholarly networks. The Finnish boom would probably not have occurred without the contributions of Väänänen and Kajanto, which in turn seem to have been made possible by the LVLT emphasis during Linkomies’s early tenure.

Despite this strong tradition, the 21st century has brought significant challenges to LVLT instruction in Finland. Structural changes in higher education, particularly the University of Helsinki’s Big Wheel reform and staff reductions, have led to cuts in course offerings and degree requirements. The shift towards efficiency-driven educational models, combined with budget constraints, has limited universities’ ability to maintain specialised courses such as LVLT. With reduced requirements, students’ opportunities to acquire highly specialised knowledge, including LVLT, have also diminished on average.

Although LVLT content remains embedded in certain aspects of Latin instruction in Helsinki, dedicated courses have become rare, and the university increasingly relies on externally funded researchers rather than permanent faculty to teach them. In some European universities with only a few staff responsible for Latin, the retirement or departure of an LVLT specialist has nearly ended instruction in the field – as appears to have happened in some Swedish universities and, in a sense, also at the University of Jyväskylä after the retirement of lecturer Helttula.

Nevertheless, at the University of Helsinki, LVLT continues to be represented in theses, albeit less frequently than in earlier decades. The continued production of doctoral theses on LVLT-related topics suggests that, despite institutional constraints, scholarly interest remains. How far this tradition will persist depends on future academic priorities, funding and the commitment of individual scholars.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank, in alphabetical order, the following persons: Josef Eskhult, Gerd Haverling, Martti Leiwo, Lotte-Maria Maasalo, Outi Merisalo, Raija Sarasti, Heikki Solin, Jaana Vaahtera and Jyri Vaahtera. Any remaining errors or misinterpretations are our own responsibility.

Archival sources

The Archives of the Faculty of Humanities Student Services, Metsätalo Student Services.

-

Teaching programmes 2004–2018

-

Degree requirements 2011–2020

The Archives of the University of Helsinki, Publications Archives, Teaching programmes (1853–1979), archival unit 176:III https://yksa.disec.fi/Yksa4/id/152663830096700

The Archives of the University of Helsinki, Archives of the Consistory, Degree requirements (1878–1923), archival unit Hf:15 https://yksa.disec.fi/Yksa4/id/152413375342100/?rd=0#tab/basic