Background

Disparities in access to and quality of healthcare services between remote and rural areas and large metropolitan centers constitute a global challenge. Countries such as Australia, Canada, and the United States have reported that these disparities result in significant inequities in access to healthcare services and treatment outcomes (Reference Dixit, Malladi, Shankar and Shah1;Reference Rechel, Džakula and Duran2). Data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare indicate that the prevalence of disease in remote and very remote areas is 1.4 times higher than in urban regions (3). Moreover, the risk of premature mortality is 1.3 times higher for men and 1.5 times higher for women living in these areas compared with their urban counterparts. These inequalities align with findings from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States, demonstrating that rural residents face a higher risk of preventable deaths due to limited access to specialized and emergency care (Reference Thomas, Wakerman and Humphreys4).

Traditional models of healthcare delivery often fall short of ensuring equitable services in geographically remote areas, where shortages of medical infrastructure, trained specialists, and advanced diagnostic equipment prevail. As a result, rural and remote populations experience higher rates of preventable diseases, avoidable hospitalizations, and mortality compared to urban populations (Reference Kumari, Wani, Liem, Boyd and Khan5). For instance, in the United States, rural communities exhibit an overall mortality rate 20 percent higher than urban populations, and one in five rural adults suffers from multiple chronic conditions, contributing to increased rates of preventable hospitalizations and deaths (6).

The advent of virtual healthcare services, including virtual clinics, has emerged as a promising solution to bridge healthcare gaps in remote and underserved regions. Virtual health, supported by digital technologies, has transformed primary, secondary, and tertiary care delivery. By leveraging virtual health solutions, healthcare institutions have enabled advanced treatments, specialist consultations, multidisciplinary team discussions, and hospital-at-home models, thereby improving patient access to complex medical interventions. Virtual clinics, through telehealth and telemedicine technologies, offer a comprehensive range of remote healthcare services, including consultations, diagnostics, treatment planning, and hospital-level care at home. These clinics represent a form of telemedicine that enables physicians and clinical staff to provide healthcare services through virtual communication platforms (Reference Vas, North and Rua7;Reference Campbell, George and Guha8).

The rapid advancement of information and communication technologies has prompted many health systems worldwide to adopt virtual clinics as a strategy to address chronic physician shortages and promote equitable access to healthcare. Although virtual health technologies have existed for decades and efforts to implement virtual clinics span over thirty years, widespread adoption remains incomplete. Despite the widespread use of digital health record systems by physicians and healthcare facilities, as well as household access to the internet, full integration of digital technologies into universally covered healthcare services is still a work in progress (Reference Duncan, Smith and Watcyns9).

Interest in the development of virtual clinics has grown substantially. Key drivers of this trend include challenges in timely and convenient access to healthcare and rising patient demand. Additional pressures to improve accessibility, ensure equity in care delivery, and reduce healthcare costs have further fueled the focus on virtual clinics. Enhancing accessibility, promoting equity, democratizing health information, and delivering cost reductions represent core objectives of virtual clinic models. Furthermore, providers in virtual clinics seek to ensure that patient, family, and caregiver expectations, experiences, equity, and safety are integrated into the design of environments that support virtual care delivery (Reference McKinstry, Watson, Pinnock, Heaney and Sheikh10).

Given the importance of equitable healthcare access and the potential role of virtual clinics in reducing health disparities, a systematic examination of their benefits and implications in remote and underserved regions is essential. Research in this domain can illuminate both operational advantages and potential limitations, thereby offering valuable guidance for policymakers and healthcare providers. Accordingly, the present study was conducted to assess the benefits and consequences of implementing virtual health clinics in remote and underserved areas.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted as a scoping review following the six-stage methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley. The stages included: (i) identifying the research questions, (ii) systematically searching relevant studies from reputable databases and grey literature, (iii) selecting eligible studies, (iv) extracting and presenting the data, (v) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results, and (vi) optional expert consultation to validate findings (Reference Arksey and O’malley11). The reporting of results adhered to the PRISMA guidelines (Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin12), and the selection process was illustrated using a PRISMA flow diagram (Reference Diagram13).

The review addressed two core questions:

-

(1) What are the outcomes and benefits of implementing virtual health clinics in remote and underserved regions?

-

(2) What types of health services have been delivered through virtual clinics in these settings?

A comprehensive and iterative search strategy was developed in collaboration with a medical information specialist librarian. The main search was conducted across PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus, supplemented by Google Scholar and Google to capture relevant grey literature and policy documents. Searches covered the period until 1 August 2025. Studies specifically focused on COVID-19 during January 2020–December 2022 were excluded to minimize bias from pandemic-driven adaptations, whereas studies from the same years not related to COVID-19 were retained. In Google, only the first 100 results sorted by relevance were considered, focusing on official health portals and institutional reports, and in Google Scholar, only peer-reviewed journal articles were included.

The finalized search string was first developed in MEDLINE and adapted to other databases using the Systematic Review Accelerator Polyglot Search Tool (14). Search terms included both MeSH and free-text keywords, such as (Supplementary Material 1):

“virtual clinic” OR “online visit” OR “online clinic” OR “virtual visit” OR “e-visit” OR “e clinic” OR “electronic visit” OR “virtual care” OR “virtual healthcare” OR “virtual health care” OR “virtual outpatient clinic” OR “online outpatient clinic” OR “virtual ambulatory care facility” OR “outpatient online clinic” OR “online primary care visit” OR “virtual hospital” OR telemedicine OR telehealth OR telemonitoring OR “remote consultation” OR eHealth OR mHealth AND “deprived areas” OR “remote rural areas” OR “underserved areas” OR “rural health services” OR “rural health” AND advantages OR benefits OR outcome

All records were imported into EndNote and then transferred to Rayyan for screening and organization.

Study selection involved three stages: (i) title and abstract screening, (ii) full-text review, and (iii) reference list examination (snowballing). Three reviewers independently assessed each record for eligibility, with disagreements resolved through discussion and unresolved cases reviewed by a fourth researcher.

Inclusion criteria comprised English-language, peer-reviewed studies examining the outcomes and benefits of virtual healthcare services for rural or remote populations. Exclusion criteria included: (a) studies without accessible full text, (b) studies focused on urban or suburban populations with full healthcare access, (c) publications in languages other than English, (d) works published after 1 August 2025, (e) theses, books, or conference abstracts without full text, and (f) studies conducted exclusively during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The term full healthcare access referred to populations with consistent, in-person access to primary healthcare facilities within a 10 km radius and without documented socioeconomic or infrastructural barriers. This was determined based on study descriptions and cross-checked with national healthcare accessibility indices. Studies limited to COVID-19 were excluded because their findings reflected temporary emergency models rather than sustainable virtual clinic frameworks.

Data extraction were conducted using a predesigned standardized form aligned with the study objectives. Extracted information included author(s), year of publication, country or setting, study design, population characteristics, type of health services delivered, and reported benefits or outcomes of virtual clinics. For included review articles, each review was decomposed into the primary studies it reported whenever possible. When primary studies were identifiable, data were extracted at the level of the individual study; when not, review findings were coded as summary data. Categories such as study design, type of health services, and reported outcomes were assigned based on the original descriptions within each study or review, ensuring consistent categorization across all included evidence. Details of the extraction template are provided in Supplementary Material 2.

Thematic analysis was conducted following Braun and Clarke’s six-step approach (Reference Braun and Clarke15), supported by MAXQD A (version 10) software. Three trained qualitative reviewers participated in the process. Each reviewer independently coded the data, and inter-coder reliability was evaluated using Cohen’s Kappa (κ = 0.81). A preliminary codebook was inductively developed during the familiarization phase and refined through iterative team discussions. Regular consensus meetings were held to review emerging themes and ensure analytic validity, transparency, and reflexivity.

All ethical standards relevant to scoping reviews were observed. The researchers maintained objectivity throughout the data collection, analysis, and reporting stages.

Results

The initial database search yielded 1,687 scientific articles. In the first screening stage, 798 articles were excluded due to duplication. During the second stage, after reviewing titles and abstracts, 605 articles were removed as they were not relevant to the research focus. In the third stage, a detailed assessment of the remaining studies led to the exclusion of 223 articles that did not report on the benefits or outcomes of interest. Moreover, an additional review of search engines identified and included five relevant reports. Consequently, a total of sixty-six articles and reports were included in the final review, forming the evidence base for evaluating the advantages and implications of implementing virtual health clinics in remote and underserved areas (Supplementary Material 2).

Figure 1 presents the frequency distribution of published studies on virtual clinics in underserved regions, both by year and by country. The data show a gradual increase in the number of studies beginning in 2002, with a consistent upward trend through 2025. The year 2021 stands out as the peak of research activity, with the highest concentration of studies published during this period.

Figure 1. Frequency distribution of published studies on virtual clinics in remote and underserved regions based on year and country.

In terms of geographic distribution, the studies were conducted across thirty-six countries. A relatively larger proportion of publications originated from Australia, the United States, and Canada, which may reflect differences in research capacity, digital infrastructure, or reporting accessibility.

A variety of research methodologies were employed. Approximately 35 percent of the studies adopted a qualitative approach, whereas 29 percent were systematic or narrative reviews, and 24 percent employed quantitative methods. This diversity in methodology highlights the multifaceted nature of research in the field of virtual health clinics and reflects efforts to capture both empirical outcomes and conceptual insights.

Table 1 presents the categorization of care services delivered by virtual clinics in remote and underserved regions, organized according to the type of service and its level of complexity. These services are broadly classified into two main categories: primary and basic care and specialized and advanced services. Some studies addressed multiple types of services, reflecting the multifaceted nature of virtual health clinic implementations. This classification highlights the diversity and scope of digital health services available in such settings.

Table 1. Classification of care services delivered by virtual clinics in remote and underserved areas

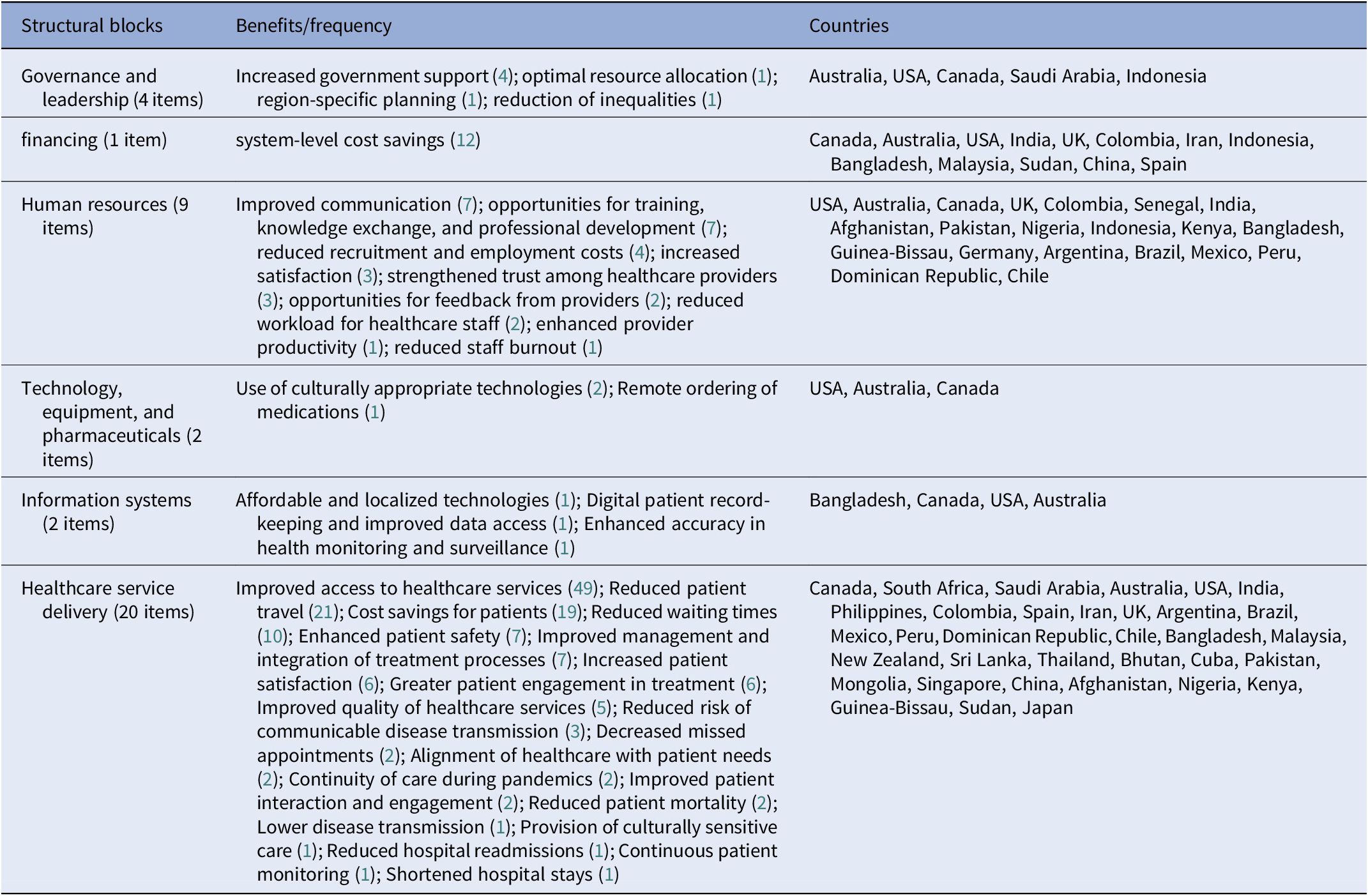

Based on the findings presented in Table 2, a total of thirty eight benefits and outcomes associated with the implementation of virtual health clinics in remote and underserved areas were identified. The largest proportion of benefits was related to the service delivery block, accounting for twenty items. Within the governance and leadership block, the most frequently reported benefit was increased government support, with four cases identified. Notably, a reduction in health inequities was reported only in Indonesia, a middle-income country. In the domain of financing, a single benefit was reported—cost savings—which was observed in both high- and middle-income countries, including Canada, Australia, the United States, the United Kingdom, and India, as well as in Bangladesh, Sudan, and Guinea-Bissau.

Table 2. Benefits and outcomes of implementing virtual health clinics in remote and underserved areas

Benefits related to the health workforce included nine items, among which the most prominent were improved communication (seven reports) and opportunities for training, knowledge exchange, and professional development (seven reports). These advantages were reported in both high-income countries (Canada, the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom) and middle-income countries (India, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nigeria, Indonesia, Kenya, Bangladesh, and Guinea-Bissau). Additional workforce-related outcomes, such as reduced burnout and enhanced productivity, were reported primarily in high- and middle-income contexts.

In the area of technology, equipment, and pharmaceuticals, the use of culturally appropriate technologies and remote drug ordering was mostly observed in high-income countries, such as the United States, Australia, and Canada. Regarding information systems, the most frequently reported benefits were the digitalization of patient records and the use of cost-effective technologies, particularly in Canada, the United States, Australia, and Bangladesh.

The service delivery block demonstrated the highest concentration of reported benefits. These included improved access to health services (forty nine reports), reduced need for patient travel (twenty-one reports), and cost savings for patients (nineteen reports). Such benefits were documented across high-income countries (Canada, Australia, the United States, the United Kingdom, Spain, New Zealand, Japan, Germany, and Saudi Arabia), upper-middle-income countries (South Africa, India, the Philippines, Colombia, Iran, Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, Chile, Malaysia, Thailand, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, and Mongolia), and lower-middle-income countries (Indonesia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nigeria, Kenya, Bangladesh, Guinea-Bissau, and Sudan). Additional reported outcomes, such as reduced waiting times, enhanced patient safety and quality of care, integrated care management, and increased patient engagement, were also observed across all income groups.

Discussion

This study aimed to identify the benefits and outcomes of implementing virtual health clinics in remote and underserved areas. A total of sixty-six relevant studies were analyzed. The increasing trend in publications in this field reflects growing attention from researchers to virtual clinics as a practical strategy for improving healthcare access in disadvantaged regions. This gradual increase not only highlights the progressive acceptance of digital health technologies within healthcare systems but also underscores the importance of evaluating the advantages and limitations of virtual clinics in delivering both primary and specialized care. Such a research trajectory provides a scientific basis for optimal planning and the identification of opportunities to enhance the development of virtual health services.

Geographical analysis revealed that virtual health clinics in remote and underserved areas have been studied across thirty-six countries, with the majority of research concentrated in Australia, the United States, and Canada. This pattern suggests that in these countries, both research and implementation of virtual clinics are more structured and established compared to other regions. Variations in the number of studies among countries may reflect differences in infrastructure, technology access, and digital health policies, indicating that nations with greater resources and defined national frameworks are better positioned to evaluate and develop virtual health services.

Methodologically, approximately one-third of the studies were qualitative, nearly one-third were review studies, and about one-quarter employed quantitative approaches. This methodological diversity highlights researchers’ attention to various dimensions of virtual clinics—from examining patient and provider experiences (qualitative studies) to synthesizing existing evidence (review studies) and quantitatively measuring service impacts and outcomes (quantitative studies). The integration of these approaches enables a comprehensive, multidimensional analysis of the benefits and limitations of virtual clinics in underserved regions, supporting evidence-based decision-making for policymakers and health planners.

The services provided by virtual clinics in remote areas fall into two main categories: primary/basic care and specialized/advanced services. This classification demonstrates the capacity of virtual clinics to address a wide spectrum of healthcare needs. Virtual clinics can deliver fundamental services such as preventive care, initial consultations, and simple follow-ups while simultaneously offering advanced services, including precise diagnoses, complex treatments, and continuous patient monitoring. This flexibility underscores the potential of virtual clinics to reduce healthcare access gaps in underserved regions and enhance equity and quality of care.

The findings of this scoping review align well with those reported in other recent systematic reviews of virtual health services, which emphasize improvements in access, cost reduction, and patient satisfaction (Reference Beheshti, Kalankesh, Doshmangir and Farahbakhsh16;Reference Agarwal, Fletcher, Ramamoorthi, Yao and Bhattacharyya17). Our study, focused on underserved regions, confirms these benefits and also highlights variations attributable to different regional infrastructure and policy environments, consistent with Tricco et al. (Reference Tricco, Langlois and Straus18). This comparison supports the robustness of our results and contextualizes them within the global literature on virtual health service implementation.

Governance and leadership play a critical role in the success of innovative healthcare delivery models. Experiences from virtual clinics in remote areas indicate that such programs can enhance government support (Reference Toll, Moullin and Andrew19;Reference Robinson20).

Conversely, lack of policy support often leads to uncertainty, resistance to change, and weakened accountability, limiting long-term sustainability (Reference Howland, Tennant and Bowen21). Moreover, limited policymaker knowledge regarding the value, roles, and applications of virtual clinics may result in inefficient planning (Reference Johnston, Smith and Preston22). Strong policy support and cohesive leadership frameworks are therefore essential to overcoming these barriers and facilitating virtual clinic adoption. Governments should develop evidence-based policies, regulations, and clinical guidelines tailored to the needs of underserved areas, clearly define stakeholder roles, and ensure active participation in decision-making processes.

In terms of financing, findings indicate that virtual clinics can significantly reduce healthcare system costs (Reference Khan, Galea and Mendez23;Reference Jong, Mendez and Jong24). For example, a pilot study by Kuperman et al. (Reference Kuperman, Linson, Klefstad, Perry and Glenn25) showed that virtual clinic implementation reduced patient transfers by 6 percent, hospital admissions by 17 percent, and hospital length of stay by 3.7 percent, leading to substantial savings in hospital resources and operational expenses. Similarly, Vindrola-Padros et al. (Reference Vindrola-Padros, Singh and Sidhu26) reported that virtual clinics for home-based patients decreased emergency department visits by 29 percent and readmission rates by less than 36 percent, while lowering long-term hospitalization costs. These findings suggest that virtual clinics not only improve clinical efficiency but also optimize limited resource allocation. For instance, at Beaumont Hospital, the cost per patient for general surgery in traditional clinics was €158.92, totaling €553,995 annually. Including administrative and clinical staff salaries, the average cost per patient visit in a virtual clinic was estimated at just €14 (Reference Rutherford, Noray and HEarráin27).

Long-term sustainability is another critical concern. Many pilot projects have demonstrated early success but failed to maintain funding, workforce motivation, and technical functionality once external support or research grants concluded. Ensuring sustainability requires stable financing mechanisms, ongoing staff engagement, and integration into national health systems (Reference Bradford, Caffery and Smith28;Reference Ahmed, Wahab, Othman and Balasubramanian29).

A significant human resource advantage identified in this study is the facilitation of training, knowledge exchange, and professional development (Reference Nataliansyah, Merchant and Croker30;Reference Allan, Webster, Chambers and Nott31). Prior studies have similarly emphasized that well-designed educational programs, particularly those tailored to underserved and indigenous populations, can reduce negative attitudes, enhance professional competence, and foster adoption of new technologies. Integrating digital health and telemedicine skills into medical curricula has been proposed as a sustainable strategy for preparing the future workforce and ensuring long-term viability of virtual care models (Reference Hosseini, Boushehri and Alimohammadzadeh32;Reference Haleem, Javaid, Singh and Suman33). In addition to education, improved communication among care team members emerged as a notable benefit (Reference Howland, Tennant and Bowen21;Reference Reid, Church, Jeffery, Tse and Phillips34). Virtual clinics enable staff in remote areas to consult online with specialists elsewhere, share patient information, and collaboratively coordinate treatment plans, which enhances interdisciplinary collaboration and overall care quality (Reference Kuperman, Linson, Klefstad, Perry and Glenn25;Reference Haleem, Javaid, Singh and Suman33;Reference LeBlanc, Petrie, Paskaran, Carson and Peters35).

However, digital literacy remains a fundamental barrier to the optimal utilization of virtual clinics. Studies have shown that limited familiarity with technology among both healthcare providers and patients—particularly in older or less educated populations—reduces the effective use of telehealth tools and hinders confidence in virtual interactions (Reference Fujioka, Budhwani and Thomas-Jacques36;Reference Du, Zhou and Cheng37). Targeted digital training and user-friendly interfaces are essential to overcome these limitations in rural settings.

Beyond the technical and organizational aspects, human factors play a critical role in the adoption and long-term success of virtual clinics. Patient satisfaction and trust strongly influence the perceived legitimacy and acceptability of remote care models. Studies have shown that when patients experience clear communication, empathy, and continuity of care through virtual interactions, their satisfaction and willingness to reuse such services significantly increase (Reference Reid, Church, Jeffery, Tse and Phillips34;Reference Sutarsa, Kasim and Steward38;Reference Mah, Pawlovich and Aldred39). Likewise, trust between patients and providers is shaped by transparency, cultural sensitivity, and consistent follow-up, which are essential for fostering engagement and adherence (Reference Babatunde, Abdulazeez, Adeyemo, Uche-Orji and Saliyu40). From the provider perspective, workload management remains a major determinant of adoption. Although virtual clinics can reduce travel and administrative burdens, they may also generate new responsibilities related to digital documentation, follow-up scheduling, and multi-platform communication (Reference Howland, Tennant and Bowen21). Balancing these factors through supportive organizational policies, adequate training, and equitable workload distribution is crucial to sustaining provider motivation and service quality in virtual care delivery.

In the domains of technology, equipment, and medication, two key advantages were identified: the use of culturally adapted technologies (Reference Rabbani, Al Amin and Tarafdar41) and remote medication ordering (Reference Bradford, Caffery and Smith28). Research shows that aligning digital health technologies with local socio-cultural contexts is critical for adoption and effectiveness. Studies indicate that using technology without considering social and cultural contexts can reduce efficiency and increase the risk of project failure. Conversely, culturally adapted technologies encourage greater acceptance by both providers and patients (Reference Blocker, Datay, Mwangama and Malila42). Experiences with telepharmacy have also demonstrated that remote medication services significantly improve access in underserved regions. Telepharmacy programs in rural US areas, for instance, allowed patients to consult pharmacists via video, ensuring high-quality medication services while reducing travel and enhancing sustainable access (Reference Perdew, Erickson and Litke43). These findings illustrate how virtual clinics can reduce health disparities and improve care quality by deploying context-appropriate technologies and facilitating medication access.

In addition to technological adaptation, cultural acceptability plays a crucial role in the adoption of virtual clinics. Research indicates that patients’ trust in technology-driven healthcare varies across cultural and social contexts, and incorporating community beliefs and local communication styles enhances engagement and satisfaction (Reference Giroux, Hagerty and Shwed44;Reference Pullyblank45).

Regarding health information systems, virtual clinics have proven advantageous in digital patient record-keeping and cost-effective technology use. For example, the Institute of Medical Sciences (IMS) in Varanasi India, implemented a locally developed, affordable digital imaging and hospital information system, providing free digital radiology services. The initial cost of the system was approximately ₹2.5 crore, with 10-year usability and negligible maintenance, projected to save over ₹2 crore annually for the healthcare system (46). Cost-benefit analyses of digital hospitals using frameworks such as eHealth-CBA further support optimal investment decisions in electronic health record implementations (Reference Nguyen, Comans and Nguyen47). These findings demonstrate that investment in digital technologies and virtual clinics enhances service quality, accelerates patient access, and generates significant financial savings for healthcare systems.

Despite these advances, connectivity and infrastructural limitations remain major challenges in remote and underserved regions. Unstable internet coverage, lack of reliable hardware, and limited technical support frequently disrupt service continuity and diminish the quality of virtual consultations (Reference Babatunde, Abdulazeez, Adeyemo, Uche-Orji and Saliyu40;Reference De La Torre, Diaz and Perdomo48).

In the healthcare delivery domain, virtual clinics offer multiple advantages, including improved access (Reference Mah, Pawlovich and Aldred39;Reference Koenig, Ko and Upadhyay49), reduced patient travel, and cost savings (Reference Toll, Moullin and Andrew19;Reference Schröder, Flägel, Goetz and Steinhäuser50). They expand patient access to primary and specialized care, enabling connections with previously inaccessible physicians (Reference Weinstein, Lopez and Joseph51). Remote consultations allow patients to benefit from high-level expertise without long-distance travel, while physicians can efficiently utilize their skills. Field studies show that virtual clinics significantly reduce patient travel; for example, in two general surgery centers in Dublin, the average one-way travel time was 43 minutes, with travel costs averaging €12.5, and patients lost on average 0.85 working days for in-person visits. Reduced travel saves patient time and alleviates pressure on transportation and hospital infrastructure (Reference Rutherford, Noray and HEarráin27). Additionally, virtual clinics reduce consultation time—averaging 5 minutes 19 seconds compared to 14 minutes for in-person visits—and lower costs, with each virtual visit averaging €14 versus higher costs in traditional settings (Reference Rutherford, Noray and HEarráin27). These efficiencies improve access, reduce travel, cut expenses, enhance healthcare system efficiency, and promote equity, making virtual clinics an effective tool for improving services in underserved areas (Reference Kaspar52).

Limitations of this study include methodological diversity and variability in study objectives, complicating the synthesis and generalization of findings. Most studies focused on short-term outcomes, with limited evidence on long-term effects and the sustainability of virtual clinics in underserved regions. Limited access to precise local data, along with cultural, economic, and infrastructural differences across countries and regions, also restricts result generalizability. Additionally, the review was limited to English-language, peer-reviewed studies with accessible full texts, which may have excluded relevant evidence from non-English publications, book chapters, or studies without available full texts.

Identified knowledge gaps and future research directions:

Despite the growing body of literature on virtual health clinics, several important knowledge gaps remain. Most studies focused on short-term benefits, with limited evidence on the long-term sustainability, cost-effectiveness, and health equity impacts of virtual clinics, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. There is also a lack of standardized outcome measures and insufficient exploration of patient and provider experiences across diverse cultural and socioeconomic contexts. Moreover, few studies have examined policy, ethical, and infrastructural challenges related to integrating virtual clinics into existing health systems. Future research should address these gaps through longitudinal, comparative, and context-specific studies to strengthen the evidence base for effective implementation in underserved areas.

Conclusion

Evidence from the included studies indicates that virtual clinics are an effective and practical solution for enhancing equity, quality, and continuity of healthcare in remote and underserved areas. By reducing geographic, economic, and workforce barriers, they facilitate improved care and specialist collaboration. However, realizing these benefits requires appropriate technical infrastructure, strong policy support, user acceptance, and effective training for optimal utilization.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462325103310.

Data availability statement

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their most sincere gratitude and appreciation to the esteemed reviewers of the article

Author contribution

PI participated in the design of the study. PI, MP, VE, and AB undertook the literature review process. All authors drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.