I. Introduction

In the wake of the 1759 Conquest of New France, the Catholic Church fought hard to become the preeminent spokesman for and representative of newly conquered French-Canadians.Footnote 1 By reluctantly accepting some abrogation of its power, such as (initially) ceding its right to pick its own bishops and instituting prayers on behalf of the British royal family, the Church had succeeded in achieving what to many seemed unthinkable: toleration of the public practice of Catholicism in Canada while this was still illegal in England itself.

Indeed, by the 1830s, some seven decades after the Conquest, the Church had managed to parlay its mere toleration into an enviable position as something of a virtual shadow state, or state within a state, by offering its services as the purveyor of education, healthcare, and poverty relief throughout Lower Canada: functions that were normally seen as prerogatives of governments, whether regional or federal, creating a weighty institutional presence, manned by flourishing vocations for the religious life,Footnote 2 across la belle province by the turn of the twentieth century. Even as it insisted upon its prerogative of confessional education, the Church took heavy financial and administrative burdens from the newly created state. More importantly (from its own perspective), the Church ensured that it was omnipresent: there to educate, to cure, and succor French Canadians from cradle to grave.Footnote 3 The Church had maneuvered itself so as to be indispensable to both the state and the people. The former regarded the Church as a useful guarantor of French-Canadian’s ongoing pacific acceptance of defeat, whereas the latter saw it as the incarnation of their defiantly different confessional and linguistic identity.

But how could the Church preach the necessity of pragmatically accepting defeat at the same time as it promised the glory of future triumph? By translating the very meaning of victory into terms that were at once spiritualized and deeply conservative. Arguably, one of the reasons why the Catholic Church was resurgent in nineteenth-century Canada was because of the ingenious and emotionally satisfying theological answer it had crafted to answer the burning question of why God had allowed the Conquest to happen. Decades in the making (as, of necessity, it could be formulated only in the aftermath of the French Revolution), the favored clerical explanation of the Conquest proposed that God, in his omniscient foreknowledge of the brutal apostasies of the coming French Revolution, effectively used the English as his unwitting tool proactively to sever the pure people of New France from the mendacious influence of its faithless mother country. This elegant, if complex, explanation of New France’s defeat allowed Québécois prelates to contradict other logical, if deeply unpopular, theological arguments that speculated, darkly, that the colony had been punished for its sinfulness, or the unthinkable thesis that God in fact favored English heretics. The explanation also provided the Church with a means simultaneously to strike out at both its free-thinking French and its British Protestant foes by suggesting that it was the folly of the former that had imposed on the divinity such a painful duty, and by reducing the latter from powerful victors to mere cogs in a deus -ex -machina whose ultimate aim was not their short-lived victory, but a far more glorious goal: the preservation of the French Canadian people as purveyors of a pure and pristine Catholicism.Footnote 4

But the true genius of this new explanation of the Conquest was its redefinition of victory to suit the circumstances of defeat. For, by the nineteenth century, triumph over both of these foes – freethinking revolutionaries and British “heretics” – meant nothing so obvious, crude, or short-lived as triumph on the battlefield. Ultimate victory, it was now discerned, lay in surviving – even thriving – as a coherent, united Catholic collective, despite the vastly altered circumstances. Those who failed to stand with and for the Church undermined its ultimate victory, signaling their status as foe, rather than friend. Those who dared to question the Church’s program and prerogatives could thus be tainted through association with either – or both – of these pernicious enemies: described as atheistic freethinkers sharing in the perverted philosophies that had led inevitably to the Terror, or as “race traitors” who, by foolishly eschewing obedience to right-thinking religious authority for anarchic individualism, shared the ideals of the British Protestants.

Playing this double game, in which both state and people saw the Church as being on their side, required it to adopt an authoritarian mien. In its relationship with the government, the Church had to be able to deliver – and be seen to deliver – on its promise of pacifism by ruthlessly stamping out any smoldering embers of rebellion that still smoldered in French Canadian hearts. But the maintenance of a top-down model of Church governance and ensuring perfect internal discipline was also central to the Church’s interest in remaining the sole representative of the French-Canadian collective. Accordingly, the Church lost no occasion to telegraph its might and its unity to audiences both internal and external.

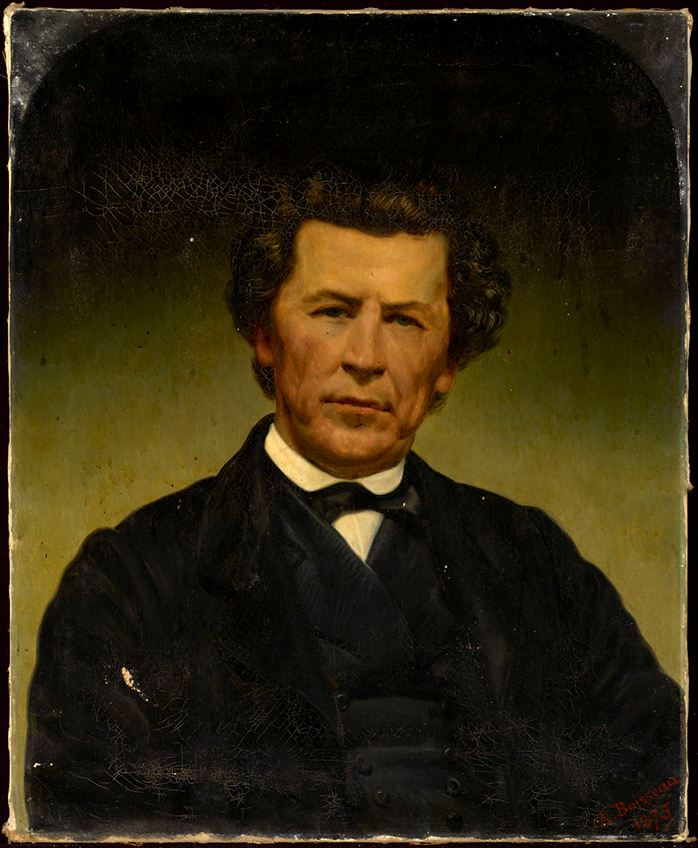

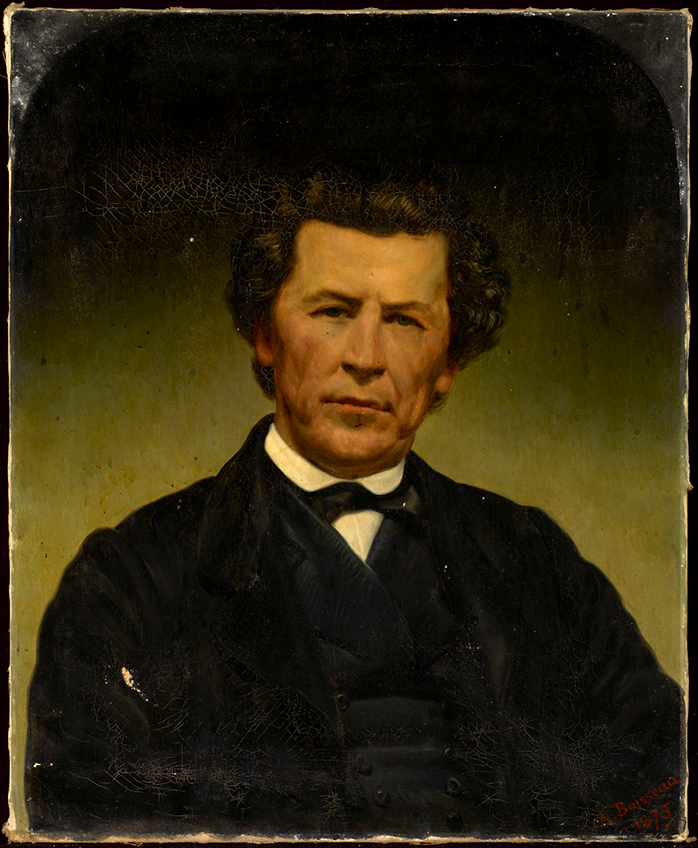

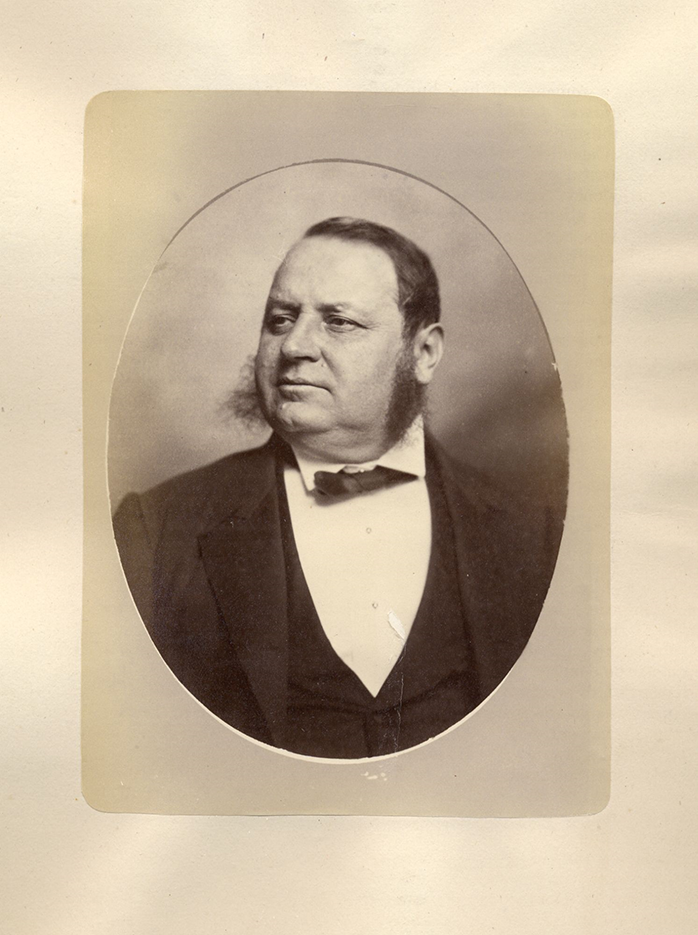

Nineteenth-century trends in international Catholicism proved to be a boon for French-Canadian prelates, as the wider Catholic ethos of the age itself increasingly stressed top-down authoritarianism and the power of Rome: a tendency which found its ultimate expression in the declaration of papal infallibility at the First Vatican Council in 1870. The degree of influence enjoyed by this international movement, known as “Ultramontanism” – a term derived from deference to the power of the pope, “over the mountains” – varied from country to country.Footnote 5 In French Canada, it would find one of its most enthusiastic and long-standing spheres of influence: for while its putative focus was upon the mighty spiritual power of the pope, the “trickle down” of his holy authority through the multi-leveled hierarchy of the Church also burnished the credentials of those on lower rungs of the ecclesiastical ladder. In a much-repeated aphorism attributed to the influential, charismatic, and long-reigning bishop of Montreal, Ignace BourgetFootnote 6 (Fig. 1), Ultramontanism was concisely expressed as: “I listen to my priest, my priest listens to the bishop, the bishop listens to the pope, and the pope listens to Our Lord Jesus Christ.”Footnote 7 Under his episcopate, which endured almost four decades, from 1840 to 1876, Catholic Quebec saw the immigration of a number of new religious orders and undertook a massive building campaign in which the dominance of the Church expressed itself through the creation of new churches, convents, schools, and hospitals, which materialized, during these seminal decades, like undersea coral. It also experienced a lengthy craze for all things Roman, from the widespread wearing of the jaunty Roman-style biretta by the province’s priests to the sending of the largest international contingent of Papal Zouaves – some 507 volunteer soldiers – in an ill-fated attempt to protect that pope’s traditional territories,Footnote 8 to the provocative construction of a smaller-scale replica of St. Peter’s Basilica in the heart of what was then Montreal’s prominently Protestant business district (Fig. 2). The provocation was redoubled by the church’s deeply confessional name – “Marie, Reine du Monde” or “Mary, Queen of the World.” Triumphalist and militant, theatrical and ritualistic, emotive and devotional, but above all, unapologetically authoritarian and paternalistic, the spirit of Ultramontanism proved the perfect fit for the emergent ethos of the Catholic Church in post-Conquest Quebec and, it can be argued, for the psychological needs of many of the men and women whom it served.

Figure 1. Ignace Bourget, the second bishop of Montreal and a lion of Ultramontanism.

Photo courtesy of the City of Montreal Archives.

Figure 2. Façade of Marie, Reine du Monde Church in Montreal, a smaller scale replica of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. The statue in the foreground, gesturing with his right hand, represents Bishop Ignace Bourget.

Image courtesy of Marie, Reine du Monde.

Excommunication – being summarily cut off from the sacraments of the Catholic Church – was the logical, if extreme, expression of Ultramontanism and of the paternal metaphor enshrined at its heart. Each level of the Church hierarchy expected submissive obedience from the ranks underneath it, from the Pope on down. Laymen and women, at the bottom of this hierarchy, were expected to know and to embrace their position as “children of the church:”Footnote 9 children subject to paternal “correction” when they erred. Excommunication was the ultimate weapon in the church’s battle with critics who sought to undercut or challenge its chosen and established role as privileged mediator between the state apparatus and the people, whether this came in the form of open rebellion against said state, or in the demand for individual intellectual freedom, or both.

Excommunication was much feared in nineteenth-century Canada, and for good reason. Spiritually, it cut off a “vitandus” or excommunicant from the sacraments: the tangible streams of God’s grace in a fallen, sinful world. Excluded from communion and confession, an excommunicant was likewise denied the consolation of last rites as their final hours dimmed to darkness. Surviving family members, moreover, were denied even the bleak comfort of consigning their loved one’s mortal coil to consecrated ground with all the dark magnificence of a Catholic internment. Worse yet, burial outside sacred space, unaccompanied by the rites of the church, was firmly linked in the popular imagination with eternal damnation.

Excommunication also had a real-world teeth designed to punish those rebels whose reasoning had led them far beyond the Catholic pale, into agnosticism or even atheism, leaving them indifferent to spiritual threats. It was costly to one’s status in the community and posed real danger to one’s economic survival, particularly for entrepreneurs, as Catholics in good standing were instructed both to eschew social contact with the vitandus and to boycott his or her business. Following these admonitions became the way that the obedient distinguished themselves from these disruptive and “rebellious children of the church.” Clerics, then, were able to leverage their parishioners’ fear of themselves being excommunicated to create a powerful system of peer pressure, which redoubled the already heavy weight of top-down condemnation. The everyday encounters of daily life – the unmet glance, the unreturned “bonjour,” the unshaken hand, were thereby freighted with weighty new meaning: transformed into mute lessons of remonstrance.

And yet excommunication was a double-edged sword, presenting considerable risks even to those who dared to wield it. When excommunication “worked,” cowing high-profile targets into a shame-faced contrition, the Church’s prestige was burnished and its powers affirmed. But what happened when excommunication “failed?” What happened when those so targeted didn’t back down, but stubbornly persisted in their errors? What happened when they used the notoriety of their public exclusion to prompt lengthy, passionate public debate over the relationship between church, state, and individual, the nature and degree of licit authority, and the value and scope of free thought and free speech? What happened when they not only refused to accept the opprobrium with which the church painted them, but cast it back onto the Church itself?Footnote 10 Is it possible to discern what circumstances enabled excommunication to “work” as a weapon of Catholic unity in nineteenth-century Quebec, and which led it to backfire? Why did Church officials react so strongly – and often against their own best interests – to instances of individual dissent? And how was the Church able to harness the passions of rank-and-file Québécois Catholics, such that the Church, so valued as an agent of popular pacification, actively fermented unrest, and even condoned rioting?

In response to these important questions, this essay will explore three prominent episodes of excommunication in nineteenth-century Canada, instances which we might characterize as a draw, a loss, and a win, from the perspective of the excommunicators. Having sketched in the instigating case of the mass excommunication of the Patriote rebels of the 1830s as something of a prologue, the essay will unpack in detail two cases from later in the nineteenth century that have a more individual focus: the infamous “Guibord Affair” of the 1870s, and the excommunication of the well-known Métis rebel Louis Riel in the 1880s. These excommunication dramas arguably have much to teach us about Canadian Catholicism in the golden age of Ultramontanism. Perhaps more unexpectedly, what we can glean from them about psychology of authority, the power of rhetoric, and the danger of mutual demonization is sadly pertinent to our own fractured and fractious age.Footnote 11

II. Prologue: Patriarchs and Patriotes

The Catholic Church of the erstwhile New France first unsheathed the sword of excommunication against the Patriote rebels in a desperate bid to undermine the size and vitality of their abortive uprisings against the federal government in the late 1830s. Driven to armed revolt by lack of government responsiveness to their desire for greater representation, the Patriote movement gave voice to widespread political frustration and the deprivations caused by economic hardship.

The Patriotes represented a clear and perfect danger to the position of the Catholic Church in 1830s Quebec both ideologically and practically. Their collective veneration of the trio of secular values – liberté, égalité, fraternité – of the French Revolution alarmed conservative Canadian clerics, both because they represented a potential rival ideological basis for Québécois collective identity and because the Church strongly associated these values with anarchic violence. Horrified by the harrowing stories of the many priestly refugees they had received and sheltered, fresh from France, since the 1790s, the Québécois hierarchy held revolutionary ideology responsible for the anarchic Terror and the orgy of bloodletting it unleashed. Always alert for signs of its pernicious germination on New World soil, the clergy sought to eradicate revolutionary ideology from Canada, root and branch, by banning the dazzling, subversive works of Voltaire and his fellow philosophes. The troubling espousal of these values by a popular movement bent on overthrow of what the Church considered to be a God-ordained and thus licit, if little-loved, government caused consternation and alarm in clerical ranks.

But the threat that the Patriotes posed for the Church was more than simply ideological. It also menaced the Church’s preferred role of acting as a privileged intermediary between the government and the French-Canadian people. In the unlikely event that the Patriotes had succeeded in their Quintoxic aspirations, claiming power, the Church would have lost much of its clout and relevance. Moreover, if the Church failed convincingly to demonstrate its authority by quashing participation in the revolt, then the reigning government would likely renege on their sweetheart deal with the Church on the grounds it had failed to control French-Canadians and ensure their submission to British rule.

From the first intimation of trouble in 1837, then, the Church sought to arrest the momentum of the Patriote cause by wheeling out the biggest weapon in its arsenal: excommunication. Bishop Jean-Jacques Lartigue of Montreal, a Sulpician, issued a dark promise: that not just the fighters but anyone who supported or financed the Patriote cause would heretofore be considered an excommunicate: a vitandus. Footnote 12 Such a threat upped the ante of participation considerably. For non-combatants, there was the uncomfortable prospect of pledging their reputation and their livelihood on what might prove to be a fool’s errand, only to be left holding the bag as a public enemy of both Church and State should the infant populist movement falter. But for those who risked their blood and their lives in what promised to be an ill-armed, David-and-Goliath battle, the threat was yet more dire. Even those influenced by revolutionary philosophies might privately baulk at the prospect of extreme unction being withheld from them in their dying moments, and perishing unshriven, without the comfort of the bland, sacred flavor of the holy sacrament on their tongues. And if they were unmoved for their own plight, what about the shame of their families, to whom they would bequeath not just mourning, but humiliation: the shame of being unable to bury their loved one in consecrated ground, or to have a Latinate word said against the grave’s encroaching darkness.

It was not in the instigation of this policy that the Church demonstrated its true determination, but in its implacable enforcement of it even in the grimmest of circumstances, when the population could easily have turned against them for their unbending harshness. The Church’s resolve was certainly tested following the battle of Saint-Eustache. On December 13, 1837, the outnumbered and outgunned Patriotes, facing an onslaught of government troops, sought refuge in the parish church named for the early Christian saint best known for his unusual vision of a white stag that bore a crucifix in his antlers. Their sanctuary abruptly turned into a hell on earth, however, as the unscrupulous government army set the building alight (Fig. 3). Many Patriotes died in the resultant inferno or succumbed to smoke inhalation. Those who attempted to escape through the church’s broken stained-glass windows, including their leader, Jean-Olivier Chénier, a doctor, were gunned down by snipers.

Figure 3. The Battle of Saint-Eustache by Charles Beauclerk. Note the flaming church and its outbuildings in the background.

Image courtesy of McCord Museum, Montreal.

The dynamics of the battle are evident in its uneven death toll. The Patriotes, already a small host, lost some 70 men. Government forces, by contrast, had only three casualties. Despite strong public sympathy for the fallen: their horrifying choice of death by fire or death by bullet and the searing irony that their holy sanctuary had been turned into an auto-da-fé, the Church remained firm: refusing to bury in consecrated ground those who had, despite their warnings, taken up arms against what they deemed a licit earthly authority.

But despite the ultimate failure of their movement, the Patriotes, who had dared to defy not just their state but also the worst threat of their Church had succeeded, however briefly, in articulating an alternative basis for French-Canadian collective identity: one based not on confessional identity but on the values of revolutionary France. The failure of their abortive uprisings was due to many complex factors. But one was doubtless that the Church’s threats had depressed the number of those willing to risk not just blood and treasure, not just life and limb, but eternal life itself on a chancy venture. The Church’s success in suppressing the number of Catholics willing openly to defy its power would provide a valuable blueprint for its actions in the decades to come. Even if excommunication had failed to achieve a total victory, it had nonetheless managed fatally to weaken a rival movement, leaving only a small, radicalized remnant that could be thwarted by other means. This lesson would be put to good use by the Church when it next unsheathed the sword of excommunication, provoking the infamous “Guibord affair,” three decades later.

III. The “Guibord Unpleasantness”Footnote 13

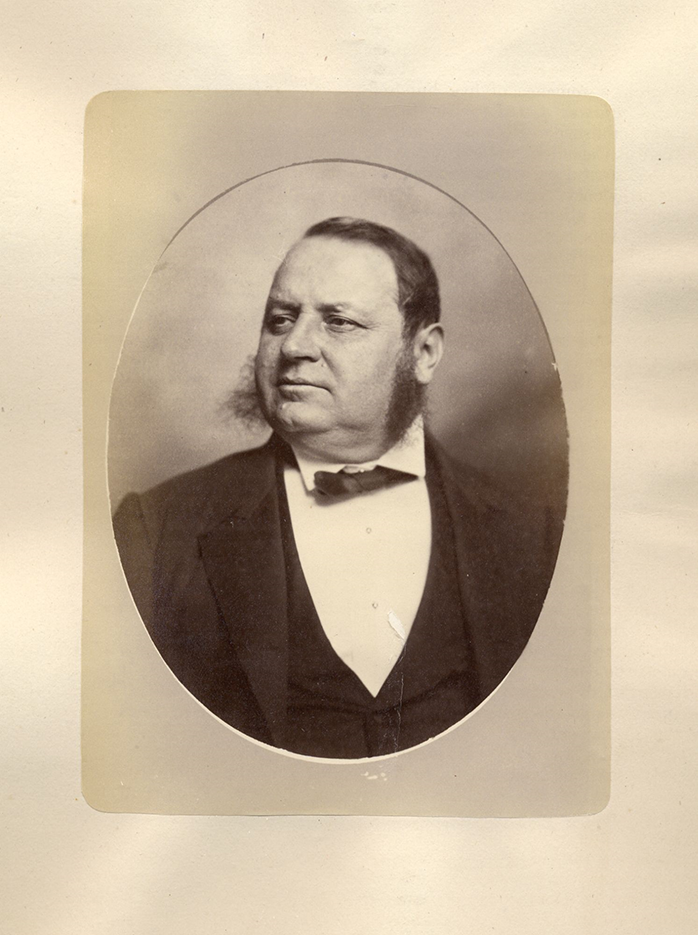

The Guibord affair of the 1870s was arguably the most famous – or infamous – case of excommunication in nineteenth-century Canada. It pitted a small group of radicalized liberals, members of a group called the Institut Canadien, a club devoted to literary and intellectual pursuits, against the full power of the Ultramontane Church as incarnated in the charismatic, leonine Bishop of Montreal, Ignace Bourget. Joseph Guibord (Fig. 4), the titular protagonist of the Affair, was destined because of its many peculiarities to be better known in death than he ever had been in life. And yet, living, this ordinary, married Catholic: a self-educated, working-class man – a printer by trade – engaged Bishop Bourget in hand-to-hand intellectual combat, together with his peers, for many years, first as a founding member of the Institut Canadien, and then as a member of its increasingly radicalized executive counsel. Guibord’s hard-won literacy, satisfying intellectual life, and consequent civic engagement were due in no small part to the resources and the inspiration of the Institut, to which he was forever faithful.

Figure 4. Joseph Guibord, the man at the heart of the 6-year-long “Guibord Unpleasantness.”

Image courtesy of Library and Archives Canada.

Ironically, given the extremes to which it would later drive him, Bourget, the episcopal successor of Lartigue, excommunicator of the Patriotes, had initially smiled upon the Institut Canadien when it was founded in 1844. A driven, ambitious bishop, whose big dreams for his city and his Church limited his sleep to an austere five hours a night, Bourget had launched a number of vigorous initiatives designed to spark a devotional renaissance upon ascending to the episcopate in 1840. A fervent adept of Ultramontanism and a firm believer in the messianic destiny of the French-Canadian people as the providential embodiment of the True Church, Bourget’s goal as Montreal’s second bishop was to expand the Church’s reach both within and outside his natal province. Within, he aimed to ensure that every French-Canadian had easy access to Catholic education and Catholic-run health care. Under Bourget’s leadership, Catholic Quebec embarked on a remarkable building campaign. Catholic schools, churches, convents, and hospitals arose, proclaiming in stone the mighty message of the Church’s ascendent power and presence. But Bourget’s outsized aspirations also outstripped the terrestrial limits of his episcopate. He enticed many French religious orders, including the Oblates of Mary Immaculate,Footnote 14 the Jesuits, and the Holy Cross Fathers to come to Canada in the 1840s. This was partly to ensure a large enough corps of religious to serve the needs of French Canadians in la belle province. But Bourget also sought to forge a dauntless cohort of religious who could continue the work of the fallen Jesuit martyrs of the seventeenth century in converting the Indigenous peoples of the far West and distant North.

Initially, then, the Institut’s aim of furthering the intellectual and cultural development of Montreal’s francophone population,Footnote 15 through its lending library and programme of public debates and speakers,Footnote 16 seemed a laudable goal to Bourget, one congruent with his own desire to elevate his people, particularly given the ongoing absence of a francophone university. But the Institut’s immense success, during its first decade, and its opening of many satellite chapters throughout the province prompted Bourget’s renewed episcopal scrutiny. By 1858, Bourget’s nagging disquiet had turned to outright alarm. The Institut, he felt, was taking the same disastrous route as had the Patriotes decades earlier in embracing and disseminating radical, anticlerical, and revolutionary views. Immediately, the agitated bishop inaugurated a determined campaign to bring the Institut to heel or, failing this, to shut it down.Footnote 17

Though the increasingly small and radicalized kernel of surviving members, including Joseph Guibord, continued energetically to battle Bourget at every turn, the powerful and popular bishop’s manifest disapproval proved devastatingly effective. Membership in the Institut had dropped by two-thirds, and all the Institut’s sixty branch chapters, arrayed across the province, were shuttered. By 1869, only the original Montreal foundation endured.

That same year, Bourget further upped the ante: placing the Institut’s yearbook or “annuaire,” which contained an eloquent defense of religious toleration, on the Vatican’s Index of forbidden booksFootnote 18 and publishing a letter in the Ultramontane newspaper, Le Nouveau Monde, warning that reading the banned tome or associating with the disgraced Institut would result in immediate excommunication:

These two commandments of the Church are of a serious nature and consequently it will be a mortal sin to violate them knowingly. Consequently, he who persists in wishing to belong to the said Institut, or who in reading, or even merely in keeping the abovementioned yearbook without permission of the Church, deprives himself of the sacraments, even the sacrament of the dead, for to be worthy of approaching it one must detest sin that kills the soul…Footnote 19

Cowed, a further 138 members of the Montreal Institut Canadien immediately quit, while the small remainder desperately appealed both rulings to the Vatican.

IV. Death Comes for Joseph Guibord

But as they waited, “God knocked.”Footnote 20 In the early morning hours of November 18, 1869, the then 60-year-old vice-president of the Institut, Joseph Guibord, suddenly collapsed and died of an apparent aneurism.Footnote 21 His widow, Henrietta, and his friendsFootnote 22 – many of them fellow members – planned his funeral for three days later at Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery, where they planned to inter Guibord in the modest single plot the prudent printer had pre-purchased to ensure the seemly burial of his own mortal remains, and those of his wife.

As scheduled, that Sunday,Footnote 23 the remaining die-hard members of the Institut, some two hundred strong,Footnote 24 walked behind the handsome funeral cortège of jet-black horses, their tossing heads topped with plumes of silky black feathers, as they drew the dark carriage bearing Guibord’s coffin down the quiet Montreal streets. But at the gates of Notre -Dame, the progress of the black-clad assembly was blocked by one Monsieur Desroches, a representative of the Fabrique, the corporation which ran the rambling hilltop city of the holy dead. Cooly, Desroches told the mourners that there was could be no possibility of Guibord’s internment in the plot of land he had purchased. His status as a vitandus, or excommunicate, forbade it.

Appalled, the assembled members of the Institut protested. Surely the excommunication could not be in effect whilst the appeal of Bourget’s ruling remained unheard in Rome? Desroches, however, was adamant. He had his orders. Should they wish to inter Guibord at Notre-Dame-des-Neiges, he would take them to the section of the cemetery that could licitly receive Guibord’s remains: the strip of unconsecrated no-man’s-land derisively known as “les gémonies,” where the unrepentant Institut member could rest eternally alongside criminals, suicides, and the unbaptized: others deemed unfit for burial in consecrated ground.Footnote 25

Their “tears and supplications”Footnote 26 being to no avail, Guibord’s mourners withdrew in confusion. The cortège made an unscheduled stop at the nearby Protestant cemetery, Mount Royal, where arrangements were hastily made to deposit Guibord’s casket temporarily in their stone vault or “charnier”Footnote 27 as his widow and friends contemplated their bleak options.

But before the funeral meats were even cold, his widow Henrietta and his Institut compatriots, radicalized by a decade of fighting with Bourget and the Ultramontane powers that be,Footnote 28 had made an unprecedented decision: to take the Fabrique de Montréal (and thus, by implication, Bourget and the Catholic diocese of Montreal) to court. Their argument? That the church’s refusal to allow Guibord to be buried in his pre-paid plot, in the regular section of Notre-Dame-des-Neiges violated the deceased’s basic civil rights.Footnote 29

V. Six Years of Controversy, Contention, and Division: “The Affair” Proper

Thus began the infamous “Guibord Affair” proper: a raging 6-year long legal battle full of dizzying twists and turns, narrow victories, and tense appeals. The original case was decided in favour of the deceased Guibord and his living plaintiffs on May 2, 1870. But their victory was short-lived, as the ruling was reversed on appeal only four months later.Footnote 30 And there the matter would have rested, had not the Institut decided to send one of its members, the indomitable lawyer Joseph Doutre (Fig. 5), to London to appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, then Canada’s highest court.Footnote 31 On November 21, 1874, the matter came full circle, as this court of last resort upheld the original decision, finding for the plaintiffs and ordering the Catholic Church to bury Guibord in his family plot at Notre-Dame-des-Neiges (Section N, number 873) and pay the plaintiff’s not inconsiderable court costs.Footnote 32

Figure 5. Joseph Doutre, a Montreal lawyer and member of the Institute, who served as its lead council for much of the Guibord Affair.

Photograph courtesy of the Bibliothèque et Archives Nationals du Québec.

From its inception, the Guibord Affair was deeply divisive. As it dragged on, year after weary year, it only became more so.Footnote 33 Both sides of the debate, predictably, tended to see their own position as the only reasonable one. To backers of the Institut, the Guibord Affair represented a particularly egregious case of overweening clerical arrogance and an outrageous expansion of Bourget’s petty persecution of a brave band of free thinkers: persecution which was now all the more deplorable for being directed against a dead man, helpless to defend himself against the heartless, unchristian treatment of his mortal remains.

Guibord’s allies and spokesmen often stressed the deceased’s modest means in life and his careful provision for himself and his wife in death: casting the Church’s refusal to bury him in the plot he had scrimped and saved to pay for as a mean-spirited, small-minded attack on one of the “little guys,” a model citizen who had lived (by civic, if not by episcopal standards)Footnote 34 an upstanding, blameless, and admirable life.

The Daily Witness cast the contest in David-and-Goliath terms, with working-class printer Joseph Guibord as a latter-day David and Bourget as a hulking Goliath: “Who but blind Ultramontanes will say that the will of the imperious Bishop should triumph rather than that justice should be done to the poor printer?”Footnote 35 For its part, The Canadian Illustrated News described the late Monsieur Guibord as “a man of irreproachable morals, of the steadiest habits, of rigid honesty, and altogether a model workman”Footnote 36 who had labored his entire 36-year career for a single employer, Louis Perrault and Sons, a print-shop.Footnote 37

A loyal husband and solid citizen, Guibord had displayed no scandalous vices and had no criminal record. Though he had assiduously paid his taxes to the government and his tithes to the church, he had nevertheless managed to leave his widow, Henrietta, unencumbered by debt. Moreover, despite his membership in the Institut Canadien, Joseph Guibord had been “born a Catholic, baptised and married in the Catholic church, and had always been a Catholic up to the hour of his death.”Footnote 38

For those who agreed with his cause, then, Guibord’s life thus told the quietly inspiring, though not unusual story of a working-class kid who had used the Institut Canadien, of which he was a founding member, to address the educational deficits of his childhood, bettering himself. The Institut had awakened his intellectual curiosity and fueled his political activism: allowing him the dignity of participating in the great debates of his time as an informed, engaged citizen. Hadn’t this very outcome been what Bishop Bourget at one time had himself envisioned, in initially backing the Institut at its founding in 1844?

But conservative Catholics, who backed the Church, saw the case very differently. For them, the Guibord case represented an outrageous usurpation of the church’s special powers and prerogatives by a fundamentally intrusive, alien, and hostile State. No other parties, Ultramontanes asserted, had any business whatsoever involving themselves in “the Affair” – which was a strictly religious matterFootnote 39 – particularly not a civil court. For by what right could any authority outside the Catholic Church presume to judge, or meddle in, its internal affairs? If left unchecked and unchallenged in this case, where would such interference of the secular state end? With the total erosion of the Church’s dignity, power, and rights, throughout the entire province of Quebec?

For loyal Ultramontanes, questioning of the Catholic Church’s powers and prerogatives was experienced emotionally as adding latter-day insult to the still throbbing injury of Conquest and their continuing subjugation to a foreign, hostile power bent on its linguistic and confessional assimilation. Because they saw the Catholic Church as the exemplar, the guarantor – indeed, as the very soul of French-Canadian collective identity – perceived disrespect for its prerogatives, even when they were made in the name of yet more universal causes, such as that of human dignity, were felt as unbearable slights on an entire people’s honor.Footnote 40

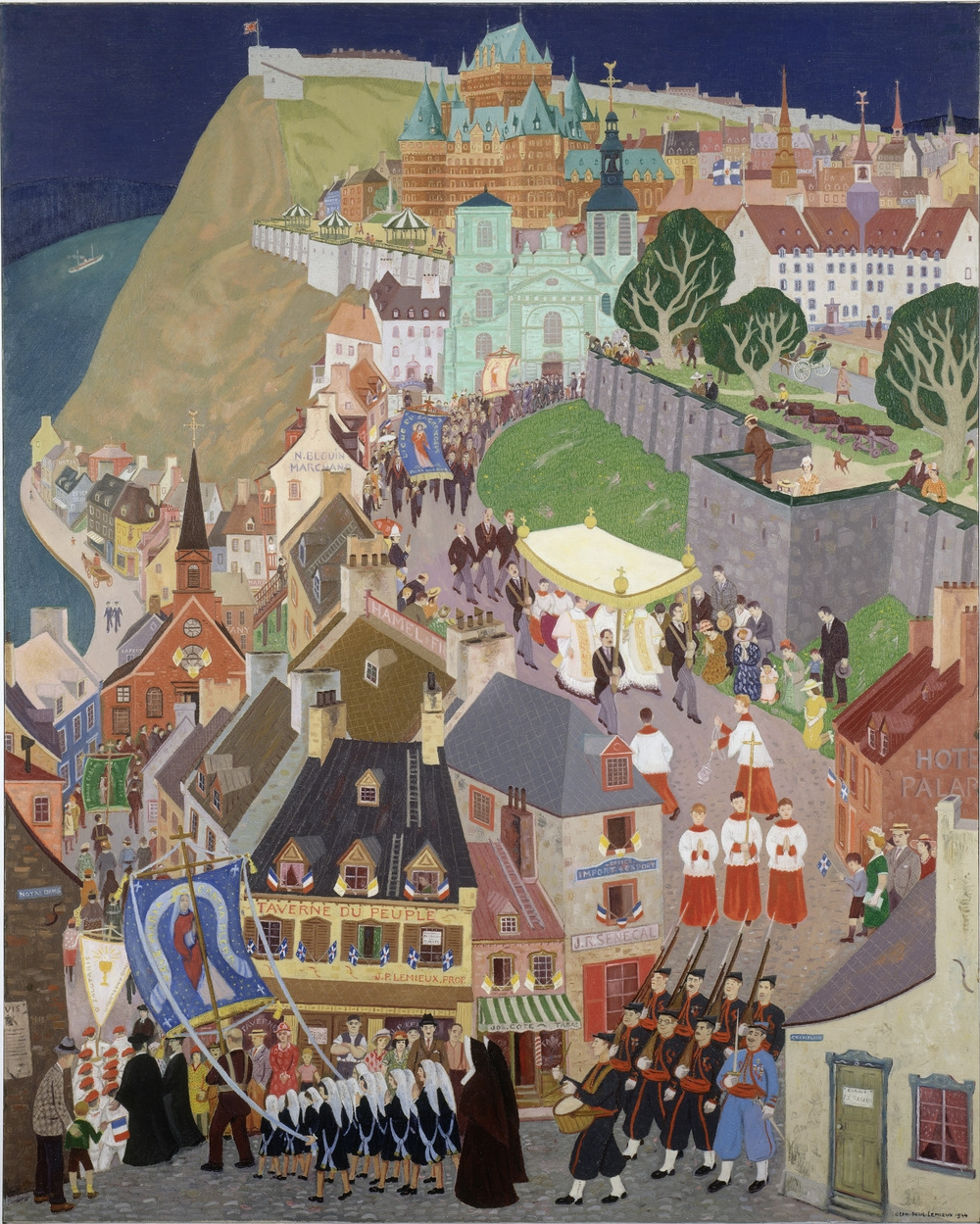

Bourget and his allies in the Ultramontane press lost no time in using the Guibord Affair to draw the clearest possible rhetorical lines between themselves and their opponents, using a series of stark dyads: us and them, good and evil, sacred and secular, purity and danger, faithfulness and apostasy, heaven and hell, truth and falsehood, light and darkness.Footnote 41 Or, in the parlance of the time, “bleu et rouge,” as in the famous political slogan, “Le ciel est blue, l’enfer est rouge,”Footnote 42 where bleu represented piety and conservatism, and infernal red the Rouge party and the Institut Canadien, united in their faithless, anticlerical liberalism. For themselves and their “imagined community”Footnote 43 (Fig. 6) of compliant French-Canadian Catholics: obedient and united under the aegis of their bishop, the Ultramontanes appropriated the flattering half of each dyad, simultaneously assigning their infernal opposites to their antagonists: the small, determined band fighting for liberalism, secularism, and the ghost of Guibord.

Figure 6. Jean-Paul Lemieux’s La Fête-Dieu à Québec. Although this painting was executed in 1944, it still gives a wonderful sense of the deeply Catholic “us” imagined by Ultramontaine Catholics in the 1870s, during the height of the Guibord Affair.

Image courtesy of the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec.

The Ultramontanes’ rhetorical strategy, particularly their decision to mobilize public opinion around the citadels of “us and them” – the beloved familiar and the foreign menace – demonstrates that they had quickly grasped that what was really at stake in the Affair. For the court case was fundamentally about not simply the burial of Guibord’s remains, but the Institut’s proposal of a different kind of “us:” one which might establish French Canadian identity on something other than confession: a vision that fundamentally challenged the central place that the Catholic Church had claimed for itself as the guarantor and the animating esprit of les habitants, using the complex, ingenious, and improbable scaffolding of clerico-nationalism.Footnote 44

But for this to work, the Guibord plaintiffs – all of whom were French Canadian and Catholic – had to be presented as menacingly and unwholesomely “other.” This explains the ubiquitous insinuation – sometimes yelled, sometimes whispered – that Guibord and his living legal representatives were “traitors to their race,”Footnote 45 by which they meant, in the parlance of the time, French-Canadians. Joseph Doutre, the Institut’s lawyer, was characterized as an apostate, an atheist – even a Protestant! – in an illogical and contradictory harangue that shows that these terms were chosen more for their ability to shock, alienate, and offend faithful French-Canadian Catholics than for any inherent accuracy.Footnote 46

This “scarlet P” branded the dead as well as the living. The fact that Guibord’s coffin had been forced to take temporary shelter in a vault at the Protestant Mount Royal cemetery was milked for maximum innuendo in the Ultramontane press: disingenuously ignoring that the Bishop’s purported excommunication of Guibord had barred reception of his corpse from all potential Catholic entities, whether cemeteries or funeral homes, within the Diocese of Montreal.Footnote 47

A similar “otherness” was intuited in the fact that the Guibord faction had taken the Church to civil court. Such a move suggested that they accepted the heresy that Church and State were and should be separate. Particularly after Doutre appealed the case to the Privy Council in London, the Ultramontane press capitalized upon their antagonists’ dependency upon the intervention of a foreign crown and country to aid their cause. Its ruling in their favor was seen as signaling not the righteousness of their plea, but the victorious plaintiffs’ craven identification with Quebec’s Anglophone Protestant oppressors.Footnote 48 And the Guibordists certainly didn’t help their own cause by cheekily placing the Union Jack over Guibord’s casket.

VI. Guibord’s “Anti-Relics”

But perhaps the most devastating allegation of an essential and uncanny otherness ranged like an excluding wall against Guibord and his party were the consistently dehumanizing references to his mortal remains, the fate of which were at the heart of the case. Articles in Ultramontane dailies such as La Minerve and Le Nouveau Monde routinely referred to Joseph Guibord simply as “le mort” or “Doutre’s [ e.g. Guibord’s lawyer’s] mort.”Footnote 49 Death became Guibord’s defining feature, effectively erasing his name, his beliefs, his very identity as a human being.

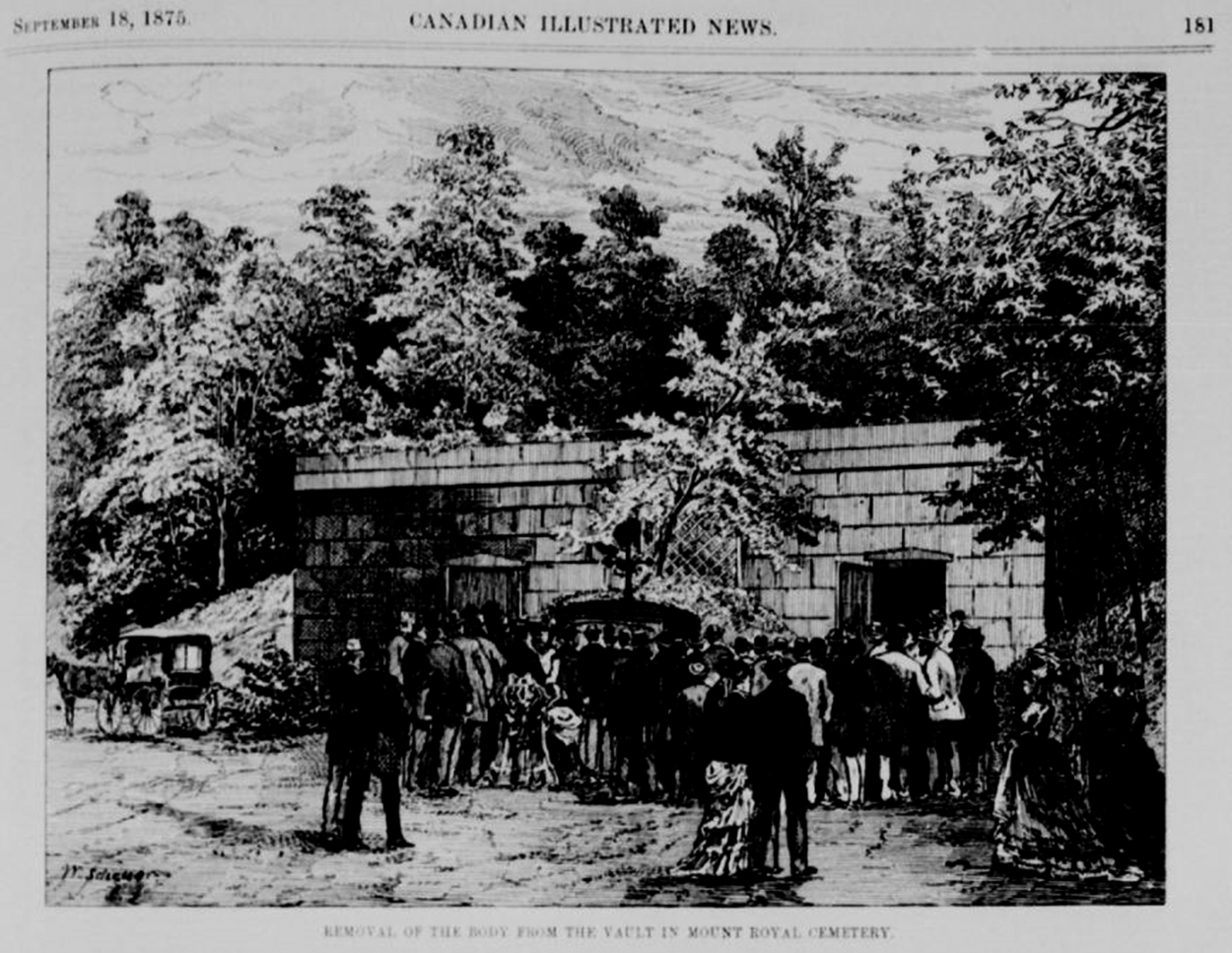

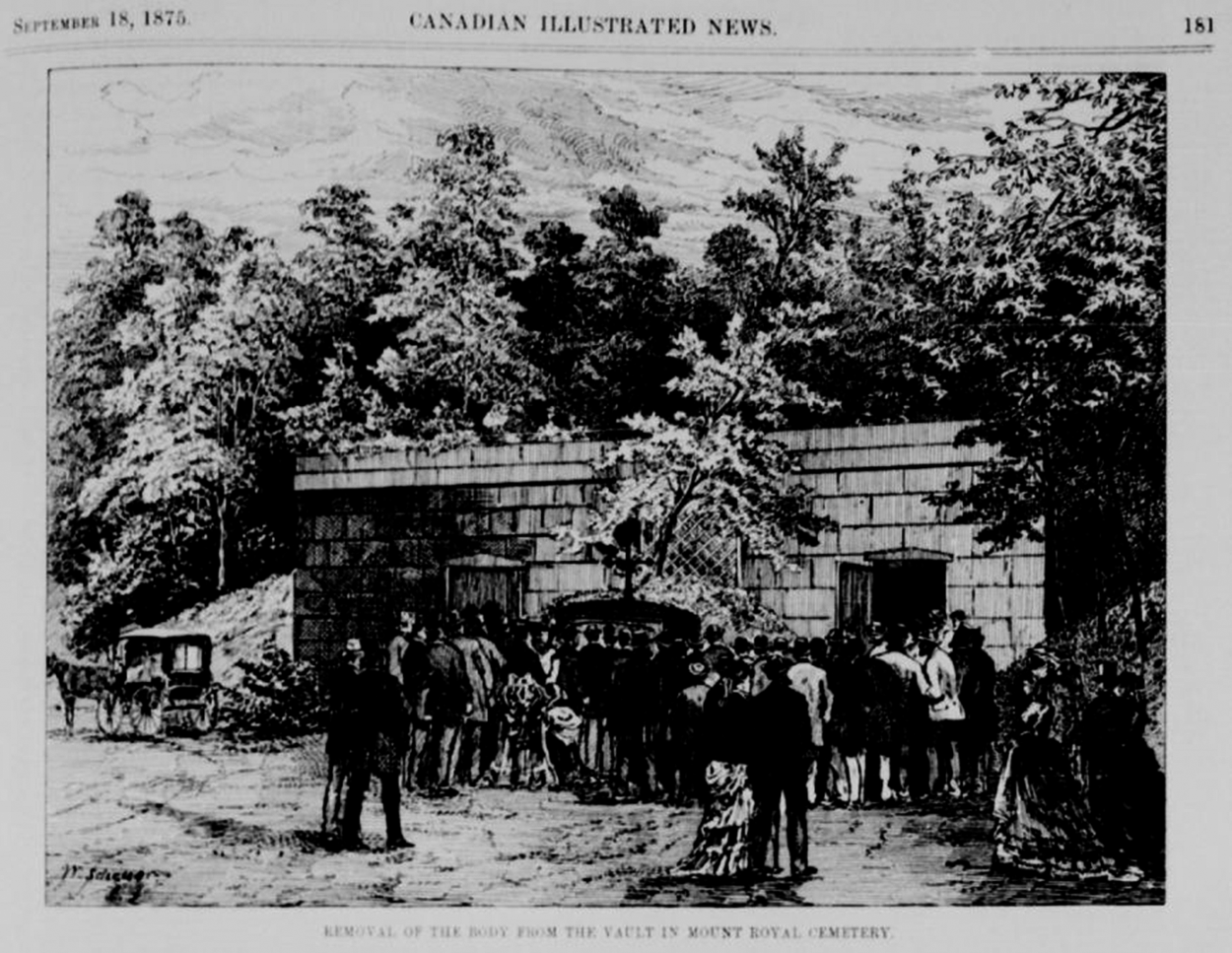

Guibord’s strong rhetorical association with death need not have been a bad thing, had his corpse been presented as being, like everyone’s, subject to the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to. But instead, his unburied body was presented as something uniquely disgusting that intimated a great deal about his postmortem fate. Much was made of the apparently “sickening odor” which floated from the “gloomy recesses”Footnote 50 of the Protestant vault where his collapsing coffin was finally retrieved, so well did this inevitable physical decay align with their insinuations of Guibord’s moral opprobrium (Fig. 7). Such an analysis, of course, conveniently ignored the fact that his body had been forced to molder above-ground for some 5 years, waiting for his friends and foes, caught up in their “grave” battle, finally to cede to one another ground enough to inter his bones of contention.

Figure 7. Joseph Guibord’s coffin being retrieved from the mausoleum at the Protestant Mount Royal cemetery. Guibord’s Ultramontaine opponents made much of the corpse’s condition, insinuating that his altogether natural post-mortem physical corruption signaled his spiritual and moral shortcomings.

Image courtesy of the Canadian Illustrated News.

The larger spiritual context of the late nineteenth century only reinforced the Ultramontane’s gothic association between physical and moral putrescence. For this period was a veritable golden age of saintly incorruption: part of the larger phenomenon of romantic Marianism that dominated Catholicism for a century. Bookended by the proclamation of two Marian dogmas, that of the Immaculate Conception in 1854 and that of the Assumption in 1950, this period featured an upsurge in the frequency, popularity, and complexity of Marian apparitions. Across Europe, Mary’s seers – often women and children, the poor, and the illiterate – brought the Virgin, however briefly, to earth to numinize the very rocks, soil, and water her flowery feet deigned to touch.Footnote 51

Through a kind of holy alchemy, these visionaries themselves – most famously Saint Bernadette of Lourdes – came to incarnate many of the Virgin’s own prerogatives, including the alleged incorruption of their bodies after death (Fig. 8). Even the same verse of Thessalonians that would later buttress the Doctrine of the Assumption was employed to explain the miraculous post-mortem preservation of her chosen messengers: “Thou shalt not suffer thy holy one to see corruption.” At least as they were unflatteringly depicted by the Ultramontane press, poor Guibord’s festering remains could not have presented a starker contrast to the luminous, if eerie beauty of these sleeping saints.Footnote 52

Figure 8. The implication that Guibord’s moral state echoed his body’s corruption was only underlined by the late nineteenth century fascination with the phenomena of incorruption. Above: the unearthly beauty of St. Bernadette of Lourdes in her glass coffin at Nevers. St. Bernadette is still, arguably, the most famous incorrupt.

Image courtesy of The Catholic Herald.

VII. Riot at a Funeral

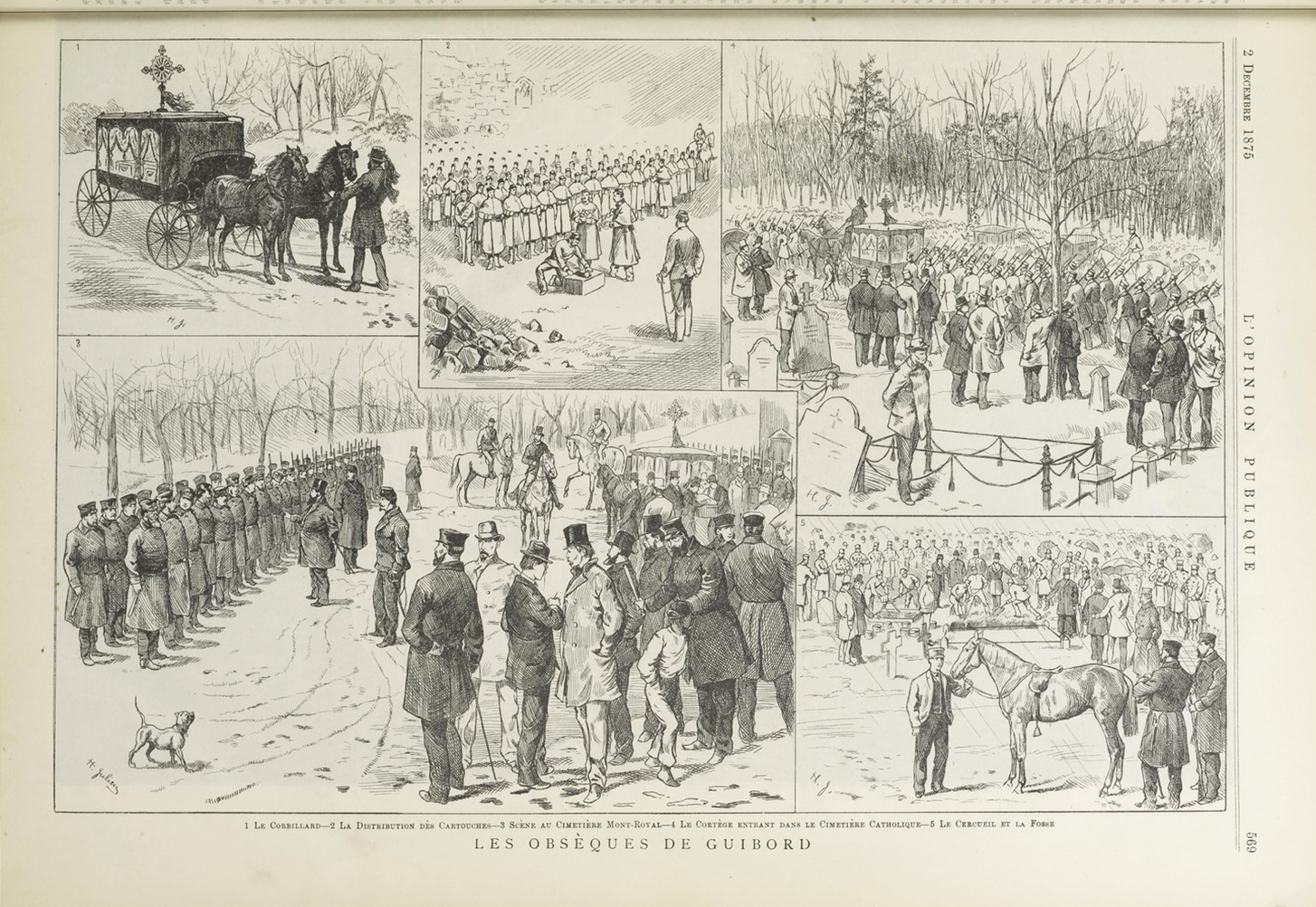

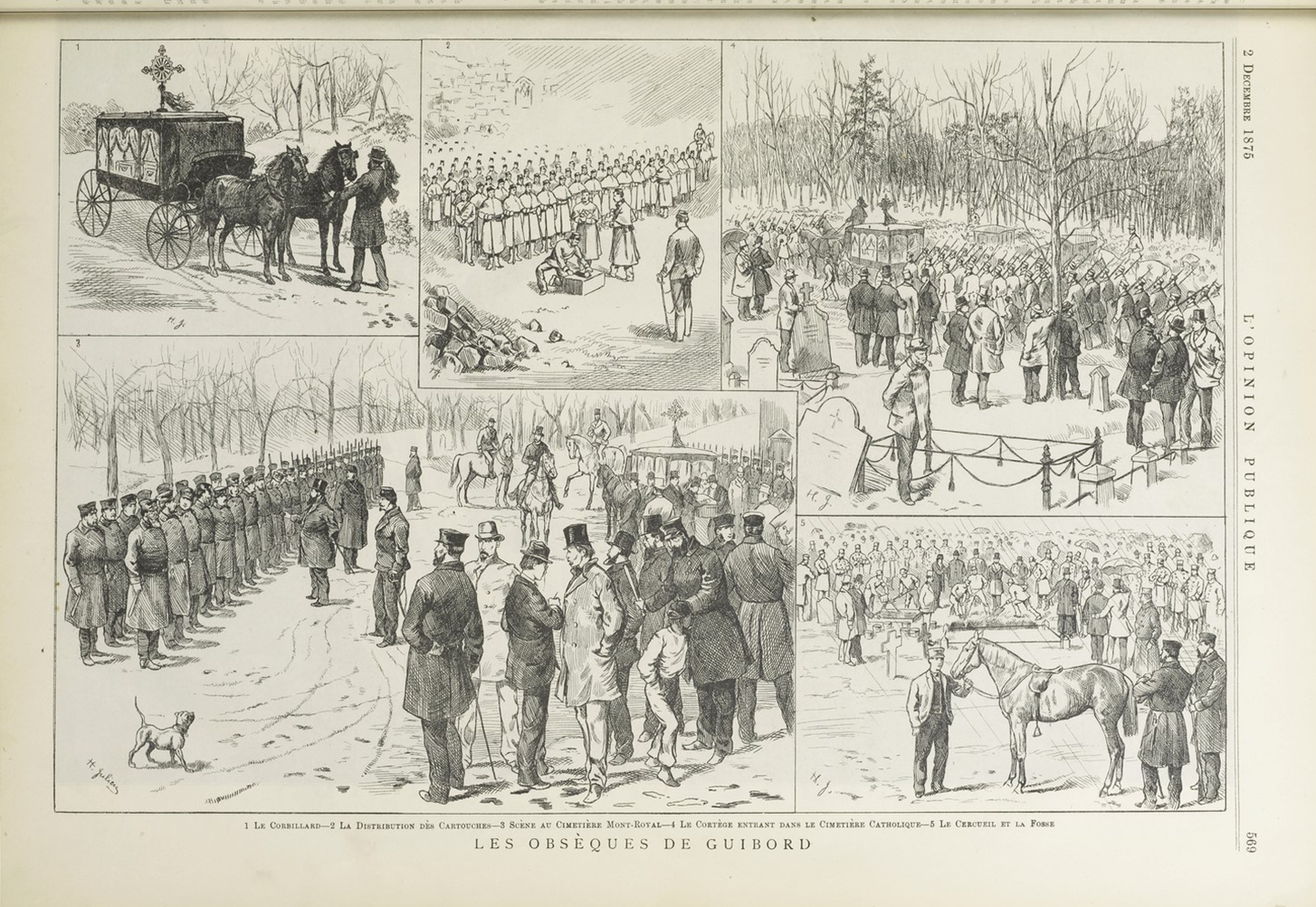

This incendiary characterization of Guibord’s body as a kind of evil “anti-relic” helps to explain the hysteria and riotous violence that greeted the second of the three attempts necessary to bury him. On September 2, 1875 – une journée dramatique Footnote 53 – Guibord’s mourners effectively re-enacted their ritual actions of almost 6 years earlier. Out came the solemn black carriage. Out came the black-bedecked horses and their dark, cross-topped carriage.Footnote 54 Out came the black armbands.

But out, too, came hostile crowds, “very violent in both language and gesture.”Footnote 55 An estimated 1000 people,Footnote 56 encouraged by the Ultramontane press to associate Guibord’s remains with danger, sin, and moral contagion, were determined to prevent this decaying interloper from contaminating the sanctified resting place of their own sleeping dead. They quickly shut and braced the cemetery’s iron gates: manning them to deny the cortège entry (Fig. 9). Loudly, they shouted their battle cries: “God damn Guibord,”Footnote 57 “Take the cursed Guibord away, he shall never be allowed to enter,”Footnote 58 “Jésus Christ, ils n’entrent pas; Mon Dieu, ils n’entrent pas; Vierge, ils n’entrent pas.”Footnote 59 Alcohol circulated freely, and a few pistols were seen amongst the brandished pick handles.Footnote 60

Figure 9. This image gives a vivid sense of the tension and the press of the crowd around the shut gates of Notre-Dame-des-Neiges during Guibord’s second, abortive funeral on September 2, 1875.

Image courtesy of the Canadian Illustrated News.

When the funeral procession appeared, it was met with a chorus of boos and a shower of rocks:Footnote 61 injuring several mourners and prompting others to remove their black mourning bands, the better to blend in with the angry crowd.Footnote 62 The black-trapped horses, unnerved by the shouting and sudden movements, began to buck, threatening to bolt. Despite their vain appeals to the “angry mob” massed at the gate, the Guibordists were unable to prevail. Fearing that the panicking horses could not withstand much more provocation, they retreated at speed, Guibord’s coffin in tow, to the relative safety of Mount Royal cemetery. Their second attempt to inter their friend, like the first almost 6 years earlier, had ended in similarly ignominious failure. Guibord’s hapless bones were still above ground.Footnote 63

VIII. Why this Strong Reaction?

What are we to make, as latter-day observers, of this riotous behavior on the part of a crowd that had gathered expressly to prevent a funeral from taking place? Why did Guibord’s presence so unnerve the crowd that they were prepared to lock the gates against him, and attempt to intimidate, by their words and actions, the black-clad mourners who had come to bury him? Is it possible, at this far remove, to recreate some of their thoughts and feelings, and discern something of their motivations?

We might start by noting that the boundaries of belonging, strongly enforced by the clerical top, were generally accepted, even embraced, by those at the laic bottom. Hence the ferocious overreaction to dissenters, whether living and dead, who inconveniently insisted upon on their individual right to think and to choose for themselves: themselves to weigh the great issues of the day, rather than falling into automatic lockstep with the self-described people of God. For ecclesial authorities, freethinkers represented a public defiance of their paternal powers and an affront to the top-down model of submission to authority that Ultramontanism promoted. For ordinary parishioners, such individuals’ audacious insistence on their own individualism and freedom seemed to shirk the collective burden that all must together bear for the greater good. Thus, rather than prompting admiration and emulation, in many cases principled dissent prompted only resentment from their fellow rank-and-file laic pew-fillers. Why did they believe themselves above the common lot: “to pay, pray, and obey?” How dare they be ungrateful for the paternal direction provided them by the better-educated clergy? Wasn’t such hubris a sign of infection, either by the reckless, Godless radicalism of the French Revolution, or the heretical individualism of anglophone Protestant culture?

Certainly, fear of assimilation and eradication as a distinct people loomed large in the hearts and minds of French-Canadians in the nineteenth century. And, in the 1870s, confessional identity, rather than more diffuse, linguistic identity, seemed the best bulwark against the encroaching waves of anglicization for a variety of practical, political, and ideological reasons.

For one, the performance of Ultramontane Catholicism and the definition of one’s collective identity in confessional terms meant that one could claim membership in an ancient, international collective, with its own venerable traditions that both transcended and dwarfed the Johnny-come-lately, Canadian confederation. Ostentatiously bending one’s knee to the Church and its many layers of hierarchy offered a perfect way of implicitly defying the assimilationist ambitions of the federal state. Performing obedience to one set of authority figures – religious superiors – was the perfect way to telegraph defiance of another: political overlords. Elaborate submission to the Church and its dictates, as loyal “children of the Church” became a favored way, then, for nineteenth-century Quebecers to perform their distinctiveness and their determination to endure as a people. Strength in numbers and representation by ecclesiastical spokesmen gave the collective their best chance of enduring as a “distinct society” or, as it was often parsed in the parlance of the time, as the French-Canadian “race.”

But this tactic could only work if everyone observed it. The unyielding façade of an otherworldly, triumphant Catholicism was only impressive and intimidating (for those both within and outside the church), if it was not beset by factionalism or riven by questioning. Only unbroken and perfect unity would telegraph the undeterred sense of higher purpose and the holy virtue of a chosen, if suffering people.

But the “carrot” of contributing, by their beliefs and behavior, to a new definition of belated victory, French-Canadian survivance, was always accompanied by the “stick” of threatened isolation. Even for those lay Catholics predisposed to interpret it as an offensive example of Church overreach, the Guibord affair presented an unnerving, real-time illustration of the Church’s incredible power to shape an individual’s reputation and treatment, both in life and in death. Excommunication, and its heavy burden of exclusion from the beloved community: exclusion that had social, spiritual, and economic implications, was communicable. Those who associated with excommunicates, or expressed sympathy for their plight, themselves risked the same fate. Could some of the crowd’s behavior come from the desire performatively to distinguish themselves from these sinners: underlining their own righteousness?

Whatever their motives, the excited crowd, having chased off the funeral cortège (with some following it all the way to the imposing gates of the rival Mont Royal), then cemented their victory by promptly filling in the hapless printer’s yawning grave, closing the earth itself against his unwanted presence.Footnote 64 But their rage, though abated, was not yet fully assuaged. Sometime between Guibord’s second and third funerals, a person or persons unknown belatedly attacked the only mourner who had been unable to flee: Guibord’s widow, Henrietta Brown.

IX. Henrietta Brown: The Woman in the Middle

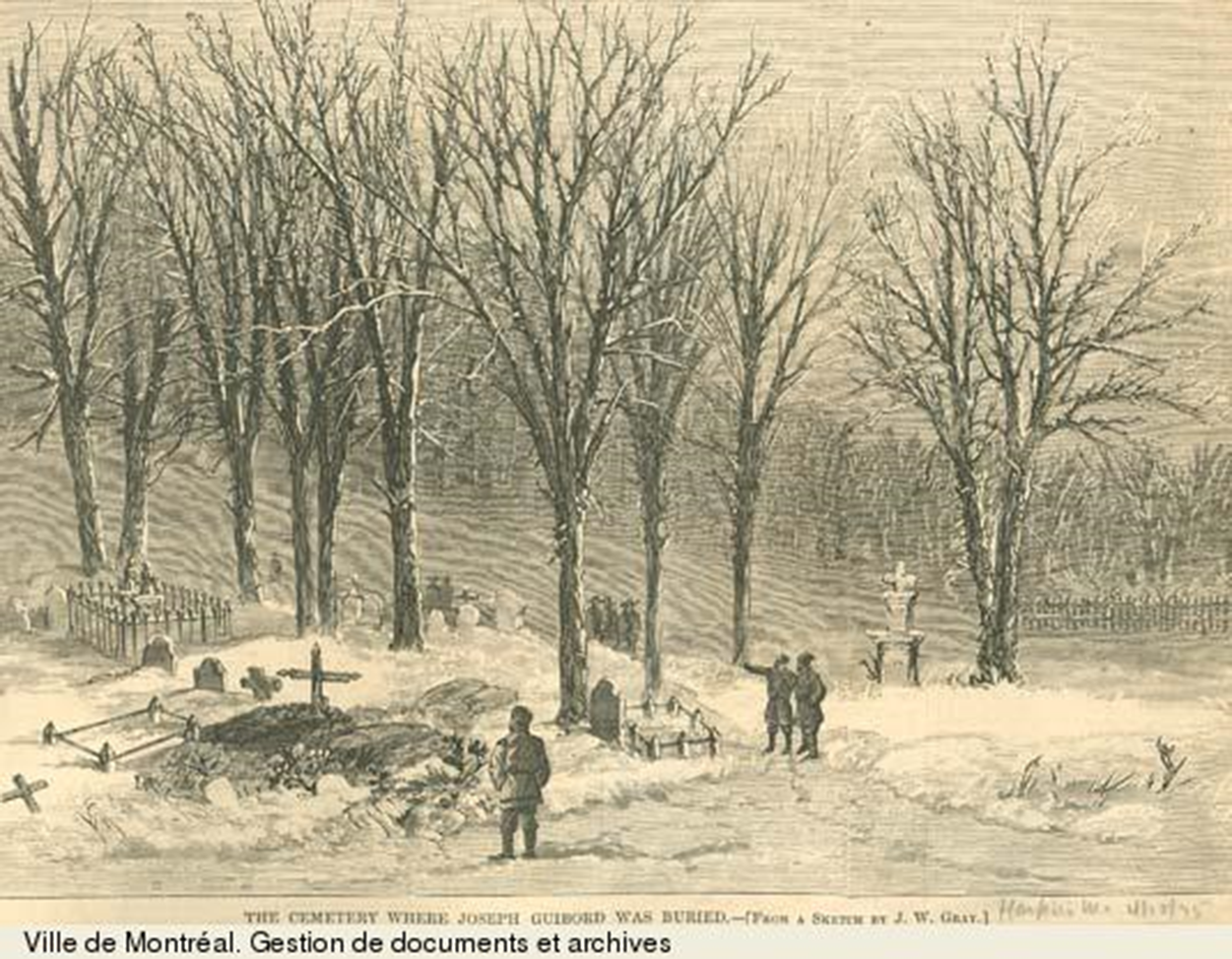

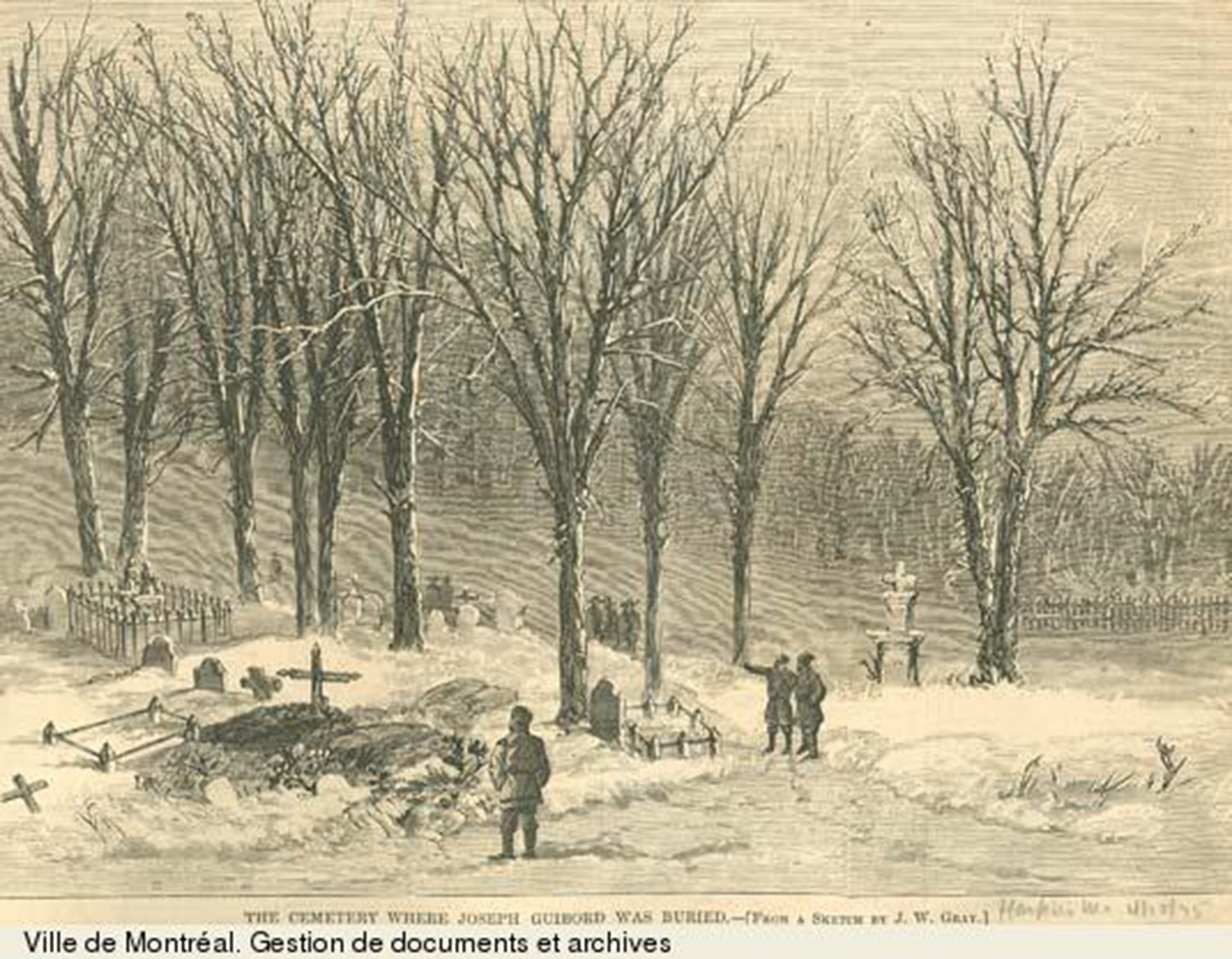

Henrietta Guibord, despite being the unmoved “first mover” of the Guibord Affair – for, had she not agreed to fight the Church for the right to bury her husband in the family plot, the Affair would never have happened – remains an essentially mysterious figure. Unlike her husband, her lawyer, and her bishop, Brown does not enjoy her own entry in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Her face did not become familiar, as theirs did, from newspaper illustrations. Moreover, the unlucky Brown, as she was consistently known in court proceedings (as the French civil law system retains a woman’s maiden name as her legal name) did not live to see her party’s hard-won victory. She had passed away some 4 years earlier, on March 24, 1873,Footnote 65 having survived only the first two of what would become the Affaire’s 6-year span. Though she did live to see her husband’s first victory, she also witnessed its reversal on appeal, and expired years before his final vindication. And then, in perhaps the crowning irony of her hidden life,Footnote 66 Henrietta’s body was placed in the very grave into which she had fought so hard to inter her husband’s remains (Fig. 10). The couple’s relative penury meant that the humble printer had only been able to afford to buy a single plot – lot N873Footnote 67 – to serve as the resting place for both himself and his wife. Their plan for a vertical burial – with one coffin stacked on top of the other – rather than the more conventional (but also more expensive) side-by-side internment, by no means unusual for the time, nevertheless provides a poignant reminder of their modest means.Footnote 68

Figure 10. Henrietta Brown’s humble wooden grave-marker, in the form of a cross was smashed and shredded by vandals or curiosity seekers. Though herself a faithful lifelong Catholic, Brown was seen as guilty by association with her infamous husband.

Image courtesy of the Archives of the City of Montreal.

Sadly, it seems all too likely that the unremitting stress, uncertainty, and notoriety of the Guibord Affair hastened Madame Guibord’s demise. She was, after all, a woman whom fate had put in the middle.Footnote 69 Married to a self-made intellectual firebrand, she was herself a faithful Catholic. The circumstances of her husband’s death trapped her between what she likely saw as her duty to him and his memory and the dictates of her faith. A contemporary chronicler put it poignantly:

…Guibord’s widow was distracted at what she regarded as a dishonor to her husband’s memory, and by her vain attempts to secure his remains Christian burial. She was, moreover, surrounded by people who tried to persuade her that if she had recourse to law against the clergy, there would be no salvation for her. Finally the unhappy woman’s reason almost gave way, and soon after she died.Footnote 70

Now, however, Henrietta Brown should finally have been safe, and at peace. And not just because she had been rightfully interred in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery. Mme. Guibord should have been safe from the mob because, by all of the measures used to determine “us” and “them,” she was on the Catholic side. Unlike her husband, Brown was not a vitandus, but a faithful and obedient Catholic of good standing. She was not even a member of the infamous Institut, for despite its fulsome and idealistic calls for the intellectual development of the French Canadian “race,” it did not accept female members. Moreover, though long married to the self-educated Joseph, Henrietta herself remained illiterate. Unable to read, Brown could not even sign her own name. In the many legal documents that she had to sign as a plaintiff, Henrietta could only mark an “X” to signal her understanding and assent.Footnote 71

Despite this, her 41-year-long-marriage had given her an unlikely bedfellow in her liberal husband. Her decision to put her spouse – even in death – over the rulings of her Church, and her audacious decision to take said Church to court, had turned her, in the eyes of some, into “one of them.” Accordingly, then, the plain wooden cross that symbolized her soul and marked her final resting place was upended and “found lying in the snow, torn apart” in an act of desecration.Footnote 72 The humble marker, moreover, “bore marks of the knives of relic-hunters, and was well whittled up.”Footnote 73

X. Guibord’s Final Funeral

Sadly, this was only the first of several odd post-mortem ordeals that Brown’s unique place in the Affair – as a faithful Catholic married to unrepentant vitandus – would force her to endure as her husband received his third – and final – funeral. This time, in view of the riotous events that had transpired several months earlier, on September 2, and amidst rumours of planned bombings and body snatching,Footnote 74 Guibord’s funeral cortège was escorted by “une petite armée:”Footnote 75 “horse, foot, and artillery,” in an “imposing demonstration”Footnote 76 comprised of firefighters,Footnote 77 950 militiamen and soldiers and “almost the entire Montreal police force.”Footnote 78 For the first time, the twin dark horses and their solemn load were able to enter the imposing gateway of Notre-Dame-des-Neiges Cemetery) as this time, prudently, its heavy iron gates had been removed from their hinges as a precaution against their being once again shut and braced against the cortège by an unruly foule. Footnote 79 And then, for the second time in three months, the family plot was opened, so that Joseph Guibord’s coffin could finally be “superimposed…over that of his wife.”Footnote 80

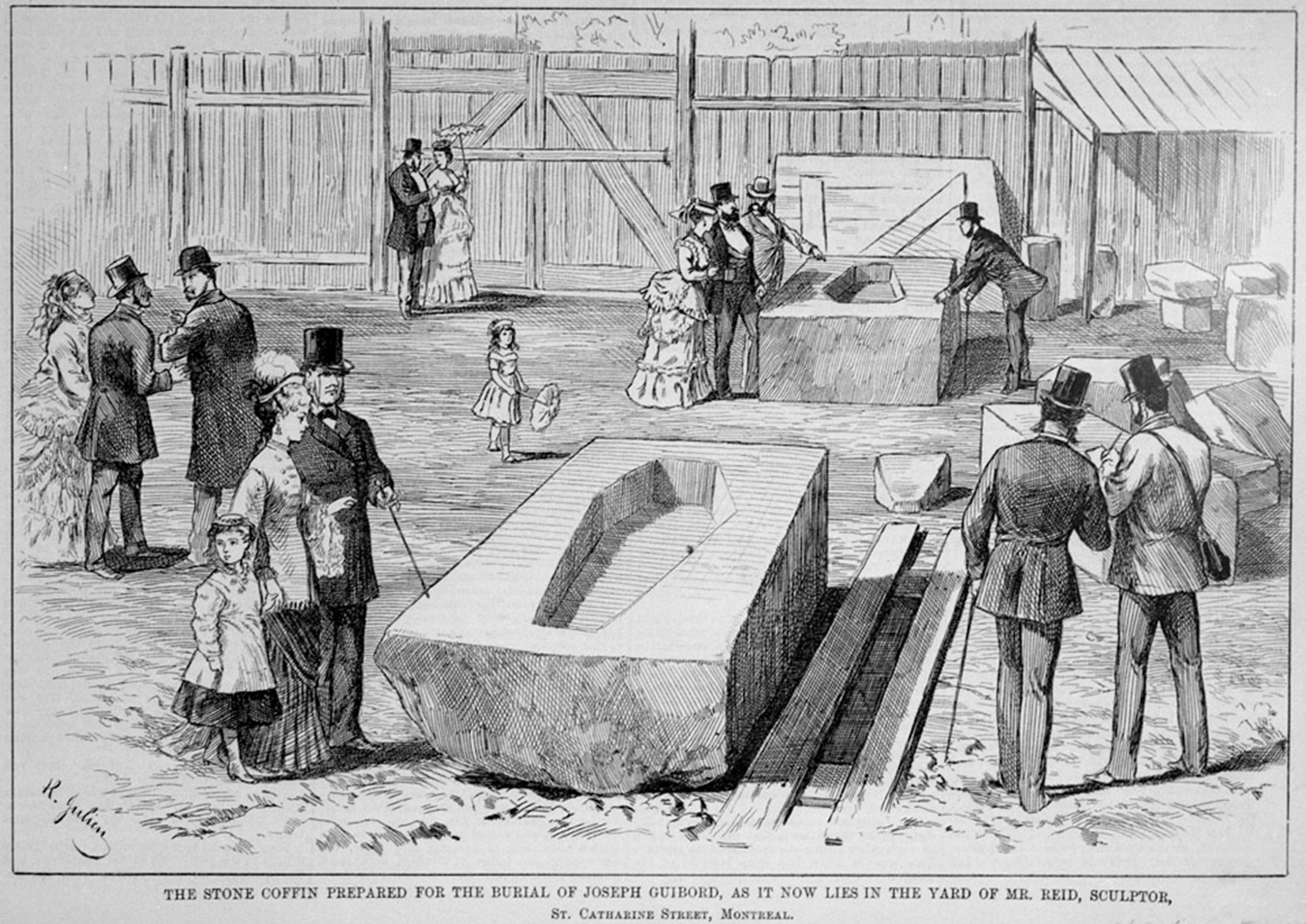

Even with Guibord finally on the brink of his grave, security concerns remained paramount. For, in the charged atmosphere surrounding the controversial internment, what would stop determined grave-robbers, convinced that Notre-Dame-des-Neiges had been profaned by Guibord’s presence, from simply removing his offending corpse, under the cover of a conspiring darkness? And perhaps that of his wifely accomplice, as well? For had her grave-marker not already been targeted: either by those who resented her role in the affair or due to the too-avid curiosity of souvenir-hunters?

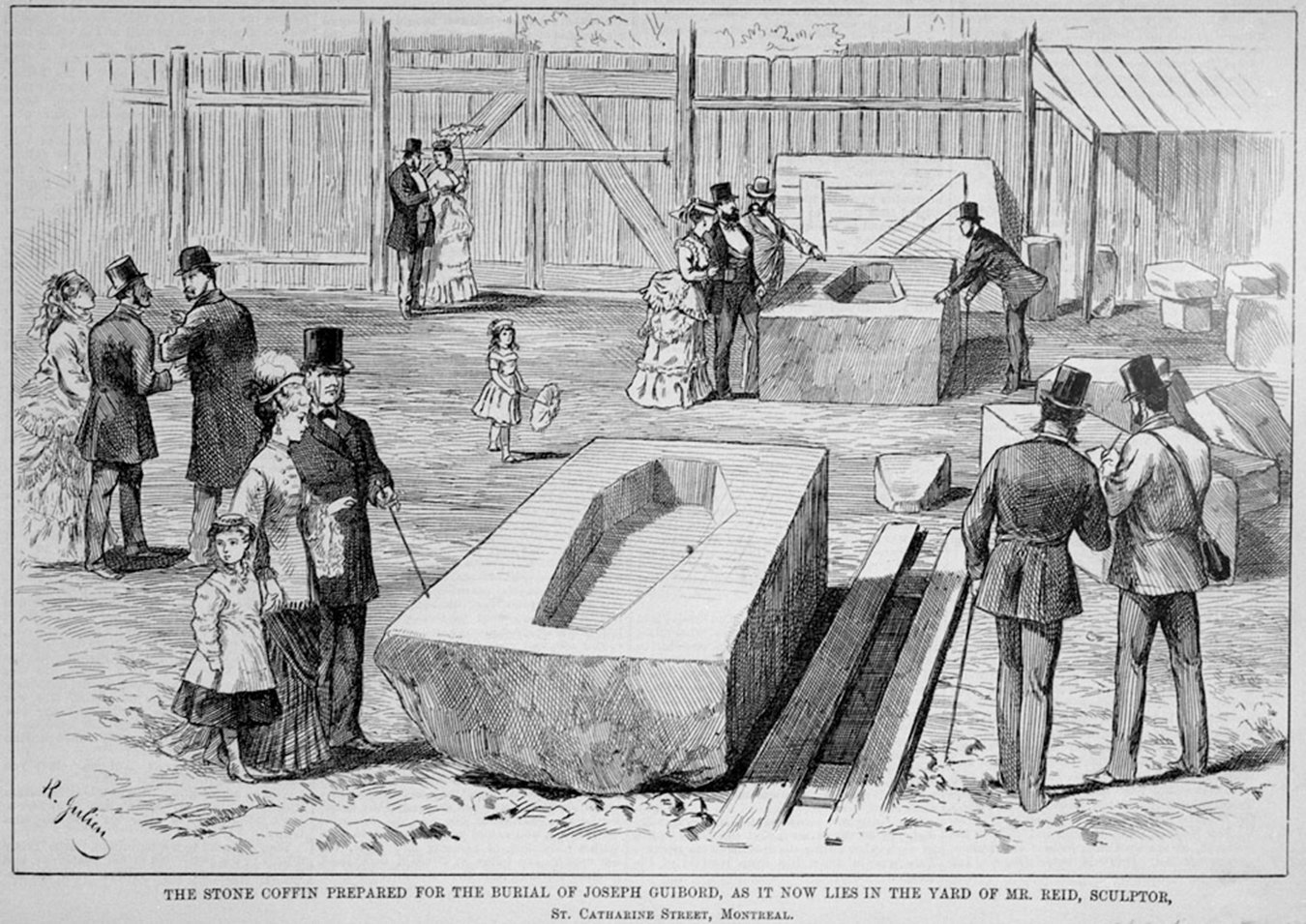

To thwart such nefarious plans, the Institut had commissioned a heavy stone sarcophagus to protect Guibord’s now-battered coffin, which they had provocatively painted rouge Footnote 81 (Fig. 11). But Montreal’s mayor nervously objected to its use on the grounds that the technical requirements of including such a heavy, unwieldy object would unduly complicate and further delay Guibord’s interment, an unwelcome risk given the eggshell-thin peace.Footnote 82 So instead it was decided that both caskets, that of the “heretic husband” and his “orthodox wife”Footnote 83 would be thoroughly encased in cement, reinforced with bits of scrap metal, to deter their would-be profaners. Accordingly, prior to the arrival of Guibord’s funeral cortège, the family grave was re-opened: “the coffin of the late Mad. Guibord was reached without difficulty, and an opening made on each side and at the ends, in order to admit of a thick layer of the Portland cement being introduced (Fig. 12).”Footnote 84 When Guibord’s coffin had finally been laid to rest in its hard-won patch of earth, it received the same treatment.Footnote 85

Figure 12. Joseph Guibord’s third and final funeral on November 16, 1875. Note the imposing black carriage and strong military presence. Though there was no religious ceremony at his internment, one of the young printers that Guibord had mentored made the sign of the cross over his casket.

Image courtesy of the Canadian Illustrated News.

Figure 11. A heavy stone sarcophagus was commissioned by the Institut Canadien to deter would-be grave robbers, but it was never used, becoming, in the aftermath of the affair something of a tourist attraction.

Image: Canadian Illustrated News, courtesy of the National Archives of Canada.

The ritual that accompanied the internment, though “bare bones,” was strangely appropriate. Though the local curé, Père Rousselot, was present, he was there only in his “civic capacity.” As the bishop’s man through and through, Rousselot, in the memorable words of his mentor, though

forced to be present, could perform no religious ceremonial, nor offer up any prayer for the repose of his soul, nor say even a single requiescat in pace; over whom he could not sprinkle one drop of holy water, whose virtue it is to moderate and quench the flames of the terrible fire which purifies the soul in another life.Footnote 86

Be that as it may, a more apt benediction, perhaps, was given by young Monsieur Camyre:

a French-Canadian printer, related to Guibord…stepped forward during the ceremony, and said if there was nobody to say a word for deceased he would like to do so. Guibord had taught him his trade, and he would like to make the sign of the cross for him, which he did and retired.Footnote 87

For their part, Guibord’s mourners, most noted for their anticlerical skepticism, were turned by the funeral’s unprecedented circumstances into relic-hunters: “Members of the Institut picked up little pieces of the scrap iron as mementoes of the unnatural way in which they had been compelled to carry out the interment.”Footnote 88 And then, clutching their sopping hats in the icy rain, and stamping their feet against the cold, the mourners dispersed.

But the couple, reunited in their single grave, were not yet alone. All through that first night, four soldiers kept a lonely watch above them to prevent any attempt to despoil their final resting place before the cement had hardened to an adamantine strength.Footnote 89

XI. De-consecration by Fiat

And yet, though her grave-marker had been slashed to splinters and her casket opened and filled with cement, the post-mortem ordeal of Henrietta Brown was still not over. To these physical insults would now be added a spiritual injury: the official de-consecration of the grave she now shared with her husband. Bishop Bourget, in a final show of defiance, finally did what he had long threatened, announcing: “the place in which has been laid the body of this rebellious child of the church is actually separated from the consecrated cemetery, as to be henceforth only a common or profane place.”Footnote 90 The lifelong Catholicity of Henrietta Brown, who shared her husband’s grave, does not seem to have been uppermost in the thoughts of her bishop. Bourget does not seem to have considered her plight or made any provision for Brown’s remains, now figuratively as well as literally overshadowed by the contested bones of her husband.Footnote 91

XII. Who “Won” the Guibord Affair?

Despite his ritual “last word,” there is a strong case to be made that Bishop Bourget emerged from the protracted Guibord Affair as the loser in the moral as well as in the legal sense: that he was roundly thrashed by Guibord’s vengeful ghost.Footnote 92 Indeed, even at the time, Bourget’s prestige took a serious hit, particularly in the international press. The bishop’s de-consecration-by-fiat of the Guibords’ hard-won final resting place received particularly widespread excoriation as an act unbefitting a prince of the Church. The New York Post wrote that his behavior “would be rather melancholy, were it not absolutely laughable,” and opined that Bourget had acted out of “petty spite.”Footnote 93 The Globe went even further, stating that this was “more like the proceeding of a weak bigot than of a large-minded, charitably disposed, Christian prelate.”Footnote 94 Both at the time and ever since, commentators have speculated that Bourget’s abrupt retirement only two months after the ignominious conclusion of “the Guibord Unpleasantness” was a direct result of this self-inflicted wound.Footnote 95

However, in the shorter term – and from the necessarily foreshortened perspective of people at the time – Bourget’s blustering proved to be a great success. For although the interminable Affair left him badly wounded, it had wholly finished off the Institut Canadien, rendering its victory over the Church wholly pyric.Footnote 96 In fighting its long battle to bury their friend, the members of the ever-shrinking Institut had completely depleted their funds. Bourget’s energetic and unrelenting intimidation had dramatically culled their numbers, and the popular opprobrium in which the organization was held discouraged new membership.Footnote 97 Though waspishly expressed, the analysis of Ultramontane newspaper, La Minerve, was fundamentally correct: “The Rouge party and the Institute have dug their own grave in digging that of Guibord.”Footnote 98 Bourget had succeeded in making his vision of French Canadian collective identity – his bleu “us” – so normative that “when French Canadian women quarrel, and wish to enrich their ordinary billingsgate, in the most extreme possible manner – one reviles the other as a Guibord.”Footnote 99 The behavior of the crowds on September 2 and November 16, 1875 show that Bourget had been wildly successful in framing the Guibord Affair as a Godless, senseless attack upon the powers and prerogatives of the Roman Catholic Church, which remained, to most French Canadians, their own symbolic soul, and their tireless defender against all enemies. His people had proven their loyalty to their bishop by passionately affirming his right paternally to control them in this life, and even in the next. And their bishop had reciprocated by surreally addressing them as his “very dear brethren,” and dismissing the bloody, drunken riot of September 2 as “a mere popular protest in favor of the reverence due the dead who have slept in the Lord and subject to the Sacred Laws of His Church.” Surreally, Bourget was effectively congratulating, rather than reprimanding, the very rioters he himself had instigated: saluting their “zeal,” and commending their relative “docility”Footnote 100 given the extent of their “just indignation.”Footnote 101

XIII. 1885: The Sword Is Unsheathed Again

But there was another, more pragmatic reason why, despite the Institut’s successful challenge to its ultimate enforceability, excommunication continued to be widely used across Ultramontane Canada: when used against the right kind of rebel, it actually worked! Invoked against one of the most famous – or infamous – figures of the tumultuous 1880s, excommunication forced this high-profile target’s contrite and public volte-face within a matter of months. Returning to the Catholic fold, he ostentatiously submitted his neck to the Catholic yoke. “Renouncing…all the special interpretations that I have made of my mission which my confessor and director does not approve,” the erstwhile rebel expressed his wish to “re-enter the bosom of the Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman Church,”Footnote 102 and to live and to die with, in, and for it. And so he did: succumbing to death only three and a half months after his penitent readmission and as a veritable martyr in the eyes of many of his Canadian coreligionists.

Who was this man? This famous rebel, whom excommunication contrived to tame?

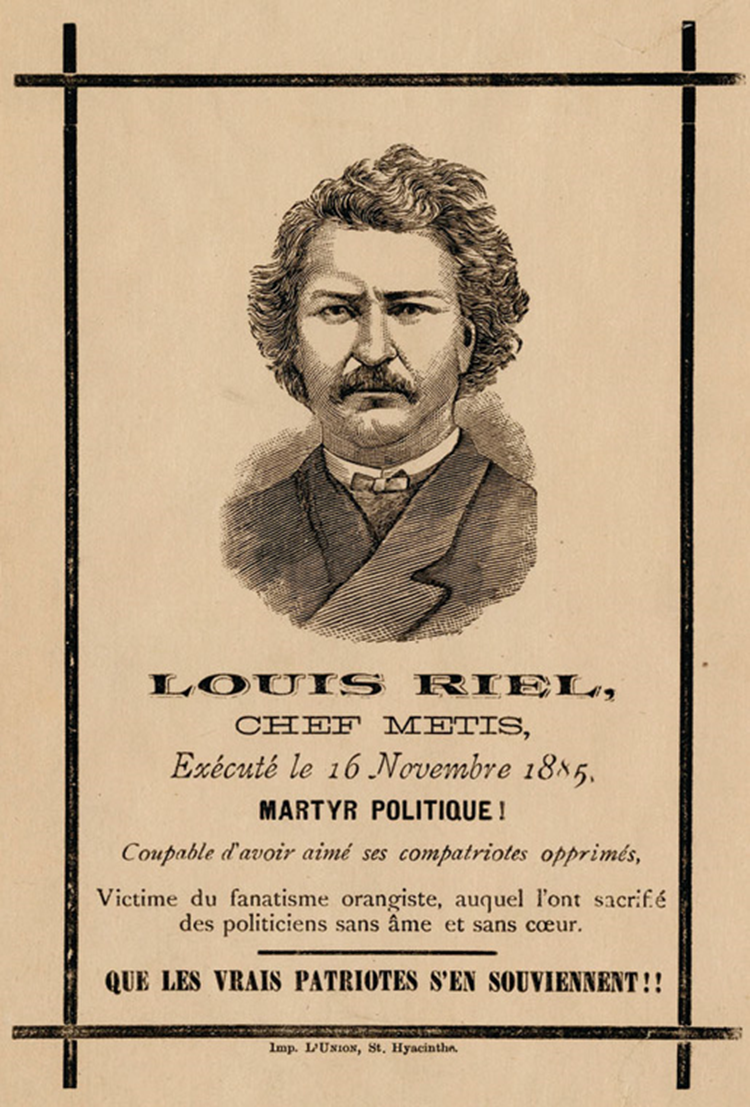

It was none other than Louis Riel (Fig. 13).

Figure 13. Louis Riel in 1875, reading a letter and looking pensive.

Image courtesy of Library and Archives Canada.

XIV. Louis Riel: A Revolutionary Life

In contrast with Joseph Guibord, who is largely forgotten today, Louis Riel is likely at least a vaguely familiar figure for many readers. A lawyer, poet, and eloquent orator, particularly in his native French, Riel was a thoughtful, shy, and deeply devout Roman Catholic. An unlikely revolutionary in many ways, he nevertheless spearheaded two armed uprisings in a last-ditch effort to protect Métis territory from federal encroachment: the Red River Rebellion of 1869–1870, and the North-West Rebellion of 1885. Sensitive yet charismatic, bold yet fragile, Riel was a passionate advocate for the land-rights of his people, the Métis: heirs to both European and Indigenous ancestry who had long made the Western Plains their home. Conscious of his privilege in receiving a top-flight education at the Sulpician’s Grand Séminaire in Montreal, Riel drank deeply of the era’s Ultramontane piety. Mentored during his childhood and adolescence by none other than Bishop Bourget, the instigator of the Guibord Affair, Riel, because of his evident intelligence and piety, was groomed to be the first Métis priest:Footnote 103 a path he evaded to consecrate his considerable eloquence and imagination to furthering the Métis cause.

Seeing his people railroaded, both literally and figuratively, by the aggressive westward expansion of the Canadian federal state under its first Prime Minister, John A. MacDonald, Riel snowed Ottawa with a blizzard of objections, petitions, letters, and other licit means of protest Métis dispossession. But when these objections went unacknowledged, this unlikely rebel led his people in an open revolt against the state, not just once, but twice. Though Riel did eventually get his day in court, it was not in a tribunal investigating Métis land claims, but his trial for high treason: a hanging offense.

Riel was a polarizing figure in Canada, both during the 41 short years of his “revolutionary life,”Footnote 104 and in the lead-up to and aftermath of his dramatic death. Perceptions of Riel, however, depended largely on the native tongue and confessional identity of the perceiver. In both the pre- and post-Confederation era, Quebecers jostled fiercely with their Anglophone Protestant competition to make the opening West proudly French and devoutly Catholic. In a messianic Catholic iteration of the American doctrine of Manifest Destiny, French Canadians supported immigration drives, rallied behind missionary orders who consecrated themselves to the missionization of the Canadian hinterlands – such as the Oblates of Mary Immaculate – and championed the cause of the French Catholics already resident in the West: les Métis. Though lionized by francophone Catholics as a symbol of their hopes for an Ultramontane West, Riel was generally perceived as a pest at best or a dangerous lunatic at worst by anglophone Protestants. The 140 years since his death have elevated and unified perceptions of Riel, who is now recognized as a Canadian “founding father” because of his role in the establishment of Manitoba’s first provisional government and because of his early and passionate advocacy for Métis and Indigenous rights.Footnote 105

But Riel continues to fascinate and to haunt us at least as much because of what we don’t know about his dramatic life and troubling death. His celebrated biography encompasses many unresolved issues, from the thorny question of his possible mental illness to the many questions raised concerning the fairness – and even the legality – of his trial, sentencing, and execution.Footnote 106 Riel’s dramatic, short-lived excommunication from the Roman Catholic Church, to which he was otherwise so devoted, represents another little-known but illuminating episode from the final year in the life of this enigmatic Canadian icon. For, on April 30, 1885, Riel was officially cut off from the sacraments of the Church.Footnote 107

XV. Why Was Louis Riel Excommunicated?

In short, because his actions left the Church no other choice. By the time that wary Western clergy finally took this step, Riel had already made a number of incendiary first moves, both politically and theologically. Barely a month before, he had launched a formal rebellion against the federal government of Canada – his second – establishing his own provisional provincial government of Saskatchewan. He then had himself declared a prophet by this newly formed body, the Exovedate – meaning, significantly, “those who have left the fold,”Footnote 108 and formally changed the weekly day of worship from the traditional Catholic Sunday back to the Jewish Sabbath. Finally, in a move designed both to signal his view that the corruption of the Old World must yield to the freshness and vitality of the New, Riel unilaterally elevated a “Pope of the New World.”Footnote 109 Who did Riel have in mind for this newly minted post of his own creation? None other than the long-retired bishop, Ignace Bourget!Footnote 110 Riel had long regarded Bourget as an important supporter of his unorthodox spiritual questing because of an 1875 letter in which the bishop had stated, vaguely if affirmatively: “God, who has always led you and assisted you until the present hour, will not abandon you in the dark hours of your life, for He has given you a mission which you must fulfill in all respects.”Footnote 111 Though meant to honor him, Riel’s announced appointment doubtless horrified the Ultramontane prelate.

And yet, despite all this, Riel had not yet been excommunicated! Indeed, things had gone so far by the end of April 1885, that those priests who belatedly wielded the sword of excommunication against the man they bitterly called “the tyrant”Footnote 112 did so as his prisoners of war. So tense had relations between the Métis rebels and the Catholic Church become that the Exovedate feared that, should these Catholic religious be released, they would immediately divulge important strategic information about the Métis’ numbers, position, and materiel to their far more numerous federal enemy.Footnote 113

So perhaps a better question is “Why was Riel not excommunicated earlier?”

He had, in fact, narrowly escaped excommunication on many earlier occasions. On December 3, 1884, three months before the uprising began, angry Saskatchewan clerics did consider taking this fateful step. Again on March 15, 1885, the virtual eve of the revolt, a frustrated Père Jean-Vital Fourmond, pushed to his limits in a run-in with Riel, again publicly threatened him. Two weeks later an equally irate priest, Père Moulin, called him a “heretic” and an “apostate.”Footnote 114

Why did Louis Riel clash so frequently, in 1885, with the Catholic clergy he normally revered? Because he was frustrated that the priests who lived and worked among the Métis, out West, were not using their literacy and prestige to gain sympathy for their cause in the citadels of Eastern power. Not unjustly, Riel unfavorably compared their arm’s-length indifference to his own not inconsiderable sacrifices for God’s new chosen people: the biblical meek who sought to inherit their earth before it could be cruelly prised from them by MacDonald’s unscrupulous Federalists. Riel’s impassioned public questioning of cleric’s commitment to the Métis cause does not seem to have been simply for show, or for strategic advantage in winning the battle for his people’s loyalty. Rather, it was genuine cri du coeur: a real expression of disillusionment with the clergy’s failure to recognize Métis oppression and to rise up, in righteous wrath, in support of them.

Riel’s popularity meant that use of excommunication, the pastoral “nuclear option” was always postponed. Local clergy were all too aware that, should they excommunicate Riel – or even too sharply reprimand him – they risked alienating his many followers, Métis, white, and Indigenous alike, and possibly jeopardizing their ongoing fidelity to the Church.Footnote 115 Not wanting to make an already challenging situation worse, and perhaps hoping to retain what little sway they had over their embittered and rebellious flock, they had long bitten their tongues and endured Riel’s increasingly bitter tirades.

XVI. Riel’s Religion: Ultramontaine Prophesy

The belated nature of Riel’s excommunication leads to perhaps the most apropos question of all, in speaking of this part of Riel’s religious life: “Can you truly eject someone from an institution that they have already left?” The many audacious innovations that Riel had pioneered prior to his excommunication, and the fact that the basic components of his theo-political program changed little after it had occurred suggest that Riel had effectively already left Catholicism long before he was formally cast out of it.

What were the key pillars of Louis Riel’s emergent theo-political worldview during the last year of his life? Though they were many, and fascinating, this article will consider only two: prophesy and ecumenicalism. Throughout much of his adulthood, Riel was convinced that God had chosen him to fulfill a divine mission. Following a series of profound mystical experiences in December 1875Footnote 116 (a mere month after Joseph Guibord received his final funeral), Riel took the name “David” to signal that he, like his new namesake, was a latter-day prophet-king divinely ordained to uphold Métis claims to their promised lands in the Canadian West.

Riel’s application of Old Testament themes and ideas to nineteenth-century North America was both wildly original and strikingly familiar. Much like Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, Riel sought both to resurrect the Old Testament role of the prophet and to reframe Christian salvation history to give North America a far more dominant and vital role (hence his would-be elevation of an appalled Bourget to his New World papacy).Footnote 117 But whereas Smith had accomplished this latter goal by effectively appending a crucial American chapter to the life of Christ, teaching that Jesus had come to convert Indigenous peoples after his resurrection but prior to his ascension, Riel’s (North) American exceptionalism struck distinctively Catholic notes (which, strikingly, persisted – or even intensified – following his excommunication). While it is true that on March 18, 1885, the first day of the Métis revolt, Riel pronounced the enigmatic words, “Rome has fallen,” this was not a renunciation of the papacy so much as its putative rebirth as a North American institution.Footnote 118

Indeed, throughout this most crucial and consequential period of his life, Riel’s religious imagination was a striking mixture of audacity and conservativism. In the words of his most recent biographer, M. Max Hamon, Riel “steered between the Scylla of liberal revolution and the Charybdis of Catholic counter-revolution.”Footnote 119 Even in revolt, Riel’s formation by Ultramontane Catholicism is still very evident, both in his religious psychology and in the different roles he created for himself and his followers. Riel’s rebellion, then, didn’t so much question Catholic patterns of authority and obedience it appropriated them for himself. An obedient “child of the church” until his excommunication, Riel now demanded unswerving submission as an authoritarian prophet-messiah.Footnote 120 This is in no way contradictory or hypocritical in an Ultramontane Catholic context, where these roles were, effectively, two sides of the same coin. As we have already seen, in a kind of spiritual “trickle-down economics,” Ultramontanes stressed the flow of inspiration and grace from God downward to his anointed leaders, pope, cardinals, archbishops, bishops and priests (to which Riel added inspired prophets) and from them to the faithful. Much like his spiritual mentor Ignace Bourget, then, Riel believed that everyone on this scale – with the sole exception of God – thus had both the duty of obedience to his superiors, and the right to unswerving obedience from his inferiors. Though many of the spiritual crises of Louis Riel’s tumultuous life stemmed from questions of where precisely he fit on this scale, his inherent conservativism meant that, even in rebellion, the scale itself went unquestioned.

Louis Riel’s spiritual authoritarianism is most obvious when we explore his relationship with Gabriel Dumont (Fig. 14), the Métis “Adjutant General” and “head of the Army.”Footnote 121 As a seasoned hunter, horseman, and warrior, Dumont was purportedly in charge of all matters related to Métis military strategy.Footnote 122 But in practice, Riel frequently usurped Dumont’s prerogatives, particularly his ability to decide when to launch attacks, and when to hold the line. Riel justified his behavior on basis that, as the group’s holy prophet, a role that he could not evade, foreclose, or delegate, he was duty-bound prayerfully to discern God’s will, even when this required crucially important hours, or even days. Moreover, throughout the conflict, Riel was preoccupied with keeping casualties on both sides to a bare minimum, and himself never shouldered a rifle, nor fired a shot in combat, choosing to bear a crucifix, rather than a firearm.Footnote 123 Mounted, and thus “very exposed,” Riel bore this cross aloft, before the eyes of his rag-tag army. His voice, raised in loud prayer and supplication of the saints, was clearly audible over the volleys of sporadic gunfire.Footnote 124 Riel’s scruples about bloodshed, his prevarications and delays, and his frequent imposition of religious exercises, even for on on-duty soldiers, often cost Métis insurrectionists the valuable strategic advantages of speed and surprise.Footnote 125

Figure 14. Riel’s right-hand man, Gabriel Dumont, was purportedly in charge of military strategy. In practice, however, Riel’s prophetic role often superseded Dumont’s tactical decisions.

Image courtesy of Parks Canada.

The response of his underlings to Riel’s behavior reveals both their shared formation in Ultramontane Catholicism and their apparent acceptance of his startling claim: “Who speaks through my mouth when I speak to you? It is God.”Footnote 126 For, though often frustrated by the delays imposed upon them by Riel,Footnote 127 neither Dumont nor any other members of Riel’s Exovedate ever engaged the enemy without their spiritual leader’s explicit say-so. Reflected Dumont: “I yielded to Riel’s judgement although I was convinced that…mine was the better plan: but I had confidence in his faith and his prayers and that God would listen to him.”Footnote 128 Riel’s deputies were thus as obsequiously obedient to him as the most cowed Montréalais was to Ignace Bourget.

XVII. A Precarious Ecumenicalism