Introduction

Ever since the mid‐2000s, scholars and practitioners have discussed vigorously whether the authoritarian backlash and the rise of popularity of authoritarian leaders in seemingly consolidated democracies is a sign of a crisis of democracy or a natural development in their life cycles (Diamond, Reference Diamond2021; Foa & Mounk, Reference Foa and Mounk2016; Howe, Reference Howe2017; Lührmann & Lindberg, Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019). The debate has concerned not only how these authoritarian tendencies occur but also whether they spread and evolve (Ambrosio & Tolstrup, Reference Ambrosio and Tolstrup2019; Diamond et al., Reference Diamond, Plattner and Walker2016). Although the research on authoritarianism has a long history with many substantial theoretical and empirical contributions, ranging from seminal works on authoritarian personality (Adorno, Reference Adorno1950; Altemeyer, Reference Altemeyer1996), theories on the nature and stability of authoritarian regimes (Linz & Stepan, Reference Linz and Stepan1996; Svolik, Reference Svolik2012), or the more general regime characteristics (Dahl, Reference Dahl1973; Sartori, Reference Sartori1987) and the way we operationalize them (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Henrik Knutsen, Krusell, Medzihorsky, Pernes, Skaaning, Stepanova, Teorell and Tzelgov2019; Freedom House, 2023a), the problem of measuring authoritarianism and similarly latent political concepts is still considered a challenge. As a result, it fuels the uncertainty about trends, patterns and developments of these concepts and how they manifest themselves in everyday politics. Speaking specifically about authoritarianism, the challenge is most obvious when it comes to political elites and their behaviour. How can the authoritarian discourse of political elites be monitored more dynamically? How can we address the fact that these elites can effectively balance their authoritarian acts with democratic episodes in a short period of time depending on the audience? How can we detect early signs of authoritarianism in democratic elites and track their development? The paper proposes a new approach to detecting authoritarian narratives in political discourse and discusses its potential for measuring a positional dimension of authoritarianism in political elites. It also outlines a new strategy for tracing latent political concepts with a primary focus on political language.

Advancements in natural language processing (NLP) and natural language understanding (NLU) have proved the robust capabilities of language modeling and its potential for intelligent processing of vast quantities of textual data. In combination with supervised machine learning and principles of transfer learning (Laurer et al., Reference Laurer, Atteveldt, Casas and Welbers2023), large language models (LLM) have been shown to be highly efficient in capturing the semantic space of latent concepts with applications ranging from sentiment and opinion mining (Pipalia et al., Reference Pipalia, Bhadja and Shukla2020) to hate speech (Corazza et al., Reference Corazza, Menini, Cabrio, Tonelli and Villata2020), fake news (Jwa et al., Reference Jwa, Oh, Park, Kang and Lim2019), but also populism (Klamm et al., Reference Klamm, Rehbein and Ponzetto2023), nationalism and authoritarianism (Bonikowski et al., Reference Bonikowski, Luo and Stuhler2022). Despite successful applications utilizing language modelling across fields and domains, applications in political science are still comparatively scarce. However, the potential these models have for political science is undeniable.

The paper introduces a machine‐learning model for detecting authoritarian discourse in political speeches trained on 77 years of data from the UN General Assembly (Baturo et al., Reference Baturo, Dasandi and Mikhaylov2017). Training design combines the transcripts of political speeches in English with a weak supervision setup under which the training data are annotated with the V‐Dem polyarchy index (i.e., polyarchic status) as the reference labels (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Henrik Knutsen, Krusell, Medzihorsky, Pernes, Skaaning, Stepanova, Teorell and Tzelgov2019). The model is trained for predicting the index value of a speech, linking the presented narratives with the virtual quality of democracy of the speaker's country (rather than with the speaker himself). The corpus quality ensures robust temporal (1946–2022) and spatial (197 countries) representation, resulting in a well‐balanced training dataset. Although the training data are domain‐specific (the UN General Assembly), the model trained on the UNGD corpus appears to be robust across various sub‐domains, demonstrating its capacity to scale well across regions and contexts.

What sets the model apart from similar applications (Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Pullan and Wäckerle2024; Laurer et al., Reference Laurer, Atteveldt, Casas and Welbers2024) is that the training is done on contextually rich sentence trigrams rather than full documents, allowing the model to learn the semantic patterns of a specific discourse. In this context, the setting allows training a model that can learn the differences in discourse defined by authoritarians on the one hand and democrats on the other. The model is then able to detect the authoritarian discourse of authoritarians and the democratic discourse of democrats but also the democratic discourse of authoritarians and the authoritarian discourse of democrats. This is one of the first attempts to build a robust classifier for studying the representation of latent political concepts in political language that is easy to use, scale up and replicate for different use cases. The paper makes two main contributions. First, it presents a robust model for detecting authoritarian narratives in political discourse, validates its robustness and outlines the potential applications in political science. These include both qualitative and quantitative applications which rely on the model's ability to annotate a lot of textual data and use it for answering research questions such as whether populists are the main champions of authoritarian discourse in democracies or what is the role of conservative political parties in the surge of authoritarianism globally. Second, the paper outlines a novel approach for training machine‐learning models focused on mapping latent political concepts in general with political language at the forefront. To facilitate interest and further development, the paper is accompanied by all training scripts as well as an easy‐to‐follow tutorial for using the final model in an inference pipeline with tips and suggestions for validation and further fine‐tuning.

What authoritarianism to measure?

When it comes to research on authoritarianism, at least three traditions are conceptually relevant to the paper's scope focused on detecting authoritarian discourse – political theory and its notion of authoritarianism as a regime type (Arendt, Reference Arendt2017; Friedrich & Brzezinski, Reference Friedrich and Brzezinski1968; Linz, Reference Linz2000; Schmitter & Karl, Reference Schmitter and Karl1991), comparative politics with its focus on authoritarian practices (Geddes et al., Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014; O'Donnell, Reference O'Donnell1979; Svolik, Reference Svolik2012) and political psychology with its focus on personality traits (Altemeyer, Reference Altemeyer1996; Stenner, Reference Stenner2005). The paper approaches these traditions as mutually complementary parts that can be arranged to connect system and individual‐level characteristics of political discourse into one unified framework.

What makes authoritarianism a vividly discussed concept in political theory comes from the fact that as a form of paternalistic rule, it is often discussed in terms of a residual category for regimes that do not meet established criteria for democracy (Glasius, Reference Glasius2018). Those criteria can range from a truly minimalist notion of free and fair election (Schumpeter, Reference Schumpeter1950) to a complex, value‐oriented and culturally grounded political regime (Dahl, Reference Dahl1971). Furthermore, the modern notion of democracy almost universally requires the fulfilment of additional fundamental democratic criteria (Przeworski & Maravall, Reference Przeworski and Maravall2003; Schmitter & Karl, Reference Schmitter and Karl1991; Urbinati & Warren, Reference Urbinati and Warren2008). This creates an amorphous category of regimes unified, more often than not, only by the common denominator of failure to meet one or more criteria for democracy (Svolik, Reference Svolik2012, 20). However, as a residual category, its conceptualization often fundamentally derives from what democracy is and is not (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish and Gastaldi2023; Freedom House, 2023a; Sartori, Reference Sartori1987; Schmitter & Karl, Reference Schmitter and Karl1991).

Research in comparative politics builds on these regime‐centric debates and develops a strong empirical perspective focused on understanding regional variations, power dynamics and stability of authoritarian rule. This tradition is rooted in the early works on authoritarianism in Latin America by Guillermo O'Donnell (Reference O'Donnell1979) and David Collier's (Reference Collier1980), Finer's (Reference Finer1962) and Nordlinger's (Reference Nordlinger1977) research of military politics, or Eisenstadt's work on informal politics (Reference Eisenstadt1983). The most recent pool of comparative studies concerns mostly works on institutionalism in authoritarian regimes (Brownlee, Reference Brownlee2007; Levitsky & Way, Reference Levitsky and Way2010; Magaloni, Reference Magaloni2006; Schedler, Reference Schedler2006) and actor‐centric perspective on authoritarian rule and its stability (Acemoglu & Robinson, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2005; Geddes et al., Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014; Svolik, Reference Svolik2012). The main contribution of this research stream comes from its focus on regime dynamics that are studied from a cross‐country perspective. Similar to the body of literature on regime type, the level of aggregation, however, remains high. This means that everyday authoritarian politics is structurally flattened into regime‐centric patterns, with less focus on the day‐to‐day dynamics of authoritarian elites’ activities and behaviour.

Finally, political psychology approaches authoritarianism as an individual‐difference variable emphasizing social conformity (Adorno, Reference Adorno1950; Altemeyer, Reference Altemeyer1981) or a value disposition (S. Feldman, Reference Feldman2003; Stenner, Reference Stenner2005). These approaches see authoritarianism primarily as a personal trait that manifests itself in both everyday life and political preferences. The concept is operationalized as a degree of authoritarian personality traditionally measured through a battery of survey questions designed to detect the authoritarian preferences of survey respondents. Different scales focus on preferences such as anti‐intellectualism and exaggerated concerns over sexuality ([F]ascist scale; Adorno, Reference Adorno1950), submission to authorities, adherence to social norms and hostility to those who deviate from these norms ([R]ight‐[W]ing [A]uthoritarianism scale; Altemeyer, Reference Altemeyer1981) and a predisposition emphasizing conformity and uniformity ([C]hild‐[R]earing scale; S. Feldman, Reference Feldman2003). Although insightful for understating personal motivations and how they may translate to political actions, these strategies have limitations. Critics argue that the scales used to measure authoritarianism actually capture something else instead. For instance, Altemeyer's RWA scale is accused of measuring conservative attitudes, while Feldman's CR scale measures social conservatism (Duckitt, Reference Duckitt, Osborne and Sibley2022). Additionally, some critics point out existing issues with the design of surveys and various cultural and political biases (such as a strong focus on the United States) (Mullen et al., Reference Mullen, Bauman and Skitka2003; Pérez & Hetherington, Reference Pérez and Hetherington2014; Peterson & Zurbriggen, Reference Peterson and Zurbriggen2010). Despite these criticisms, authoritarian scales have gained popularity in political psychology as they help identify latent signals of authoritarianism in otherwise complex personality traits (Duckitt, Reference Duckitt, Osborne and Sibley2022).

Although both empirically and conceptually relevant, all three of the discussed streams of research do not usually sufficiently address the disaggregated dynamics of authoritarian behavior in leaders and political elites. In the context of political discourse, this might refer to its intensity (e.g., how often or when authoritarian narratives prevail) or the content (e.g., changes in framing). While expert surveys (Arana Araya, Reference Arana Araya2021; Stevens et al., Reference Stevens, Bishin and Barr2006) or archival research (Brewer‐Carías, Reference Brewer‐Carías2010; Zimmerman, Reference Zimmerman2014) provide valuable insights into the profiles and actions of political figures, they offer a mostly static picture that captures either authoritarian episodes or patterns that are difficult to scale up. Additionally, expanding and re‐evaluating these insights can be too expensive or impossible. This is not to invalidate the existing approaches and their scientific merits but to highlight their empirical limitations that are hard to overcome without conceptual innovation. Computational text analysis can provide the necessary toolkit to do so.

The paper aims to address the above mentioned limitations and proposes a new approach to studying authoritarian practices through the use of political language. It combines all three theoretical areas discussed above and reassembles them in a way that embeds the theoretical advances of the discussion about the regime types (Dahl, Reference Dahl1971; Linz, Reference Linz2000; Sartori, Reference Sartori1987), strong comparative perspective and empirical variability (Geddes et al., Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014; Svolik, Reference Svolik2012) and a take on personality traits of political leaders (Altemeyer, Reference Altemeyer1996; Clifford, Reference Clifford2013; S. Feldman, Reference Feldman2003). In this context, I approach the authoritarian practice as a matter of political discourse defined by the speakers themselves. Although the approach focuses on a particular type of authoritarian practice (i.e., authoritarian discourse), it is one of the strongest observable signals in the spectrum of authoritarian practices (e.g., actions, behaviour, language). It builds on the tradition of personality traits and lexical analysis with the notion that most socially relevant and salient personality characteristics have become encoded in the natural language (John, Reference John, John and Robins2021). What makes this approach feasible is the fact that the scope is fairly generalizable with potential application to many political concepts with latent natures that are equally hard to measure.

Although the research of political language has a long tradition in many academic disciplines, studies about the specifics of authoritarian political discourse have started to appear relatively recently (Bonikowski et al., Reference Bonikowski, Luo and Stuhler2022; Dowell et al., Reference Dowell, Windsor and Graesser2016; Maerz, Reference Maerz2016, Reference Maerz2018; Maerz & Schneider, Reference Maerz and Schneider2020; Schafer, Reference Schafer2023; Windsor et al., Reference Windsor, Dowell, Windsor and Kaltner2018; Windsor et al., Reference Windsor, Dowell and Graesser2014). The common denominator of this stream of research is embedded in the notion that authoritarian discourse is a form of qualitatively unique political language. The paper adheres to this tradition and approaches narratives used by authoritarians and democrats as distinguishable political traces that can be studied systematically (Maerz, Reference Maerz2019; Maerz & Schneider, Reference Maerz and Schneider2020). Political discourse in this context refers to a range of different types of talk and text that tell us what politics talk about and how. In this context, language is seen as inherently political (Blommaert, Reference Blommaert2005; Joseph, Reference Joseph2006; O. Feldman & de Landtsheer, Reference Feldman and Landtsheer1998), having the capacity to mediate how the world appears to the public (Blommaert & Verschueren, Reference Blommaert and Verschueren1998; van Dijk, Reference Dijk2009; Wodak & van Dijk, Reference Wodak and Dijk2000).

Rather than trying to define what an authoritarian and democratic discourse is, the paper takes a step back and looks at how authoritarians and democrats talk first. This approach deviates from many research strategies existing in the research of authoritarianism, which is grounded in deductive reasoning. The proposed strategy comes from the tradition of studying political discourse inductively but with a mostly quantitative outlook. The strategy can be summarized as a combination of macro structural characteristics of the regimes speakers represent and the speech acts they author. In this context, the basic assumption is that the official narratives of political elites are the embodiment of the regimes they originated from. This inductive reasoning then allows us to model the language of those who are associated with authoritarian regimes and those who are not. If the basic assumption holds, the language should differ among the groups, and the indices existing in the narratives should detect prevailing discourse associated with authoritarian/democratic leaders across regions and time. In this context, authoritarianism as a discourse is approached as a discourse championed by authoritarians. ‘How much authoritarian’ is conditioned by overall loading in authoritarian discourse, which we might not know much about yet, but we know those who define it. In this context, the proposed approach is predominantly data‐driven, focused on learning the representation of discourse championed by authoritarian and democratic elites.

Training data

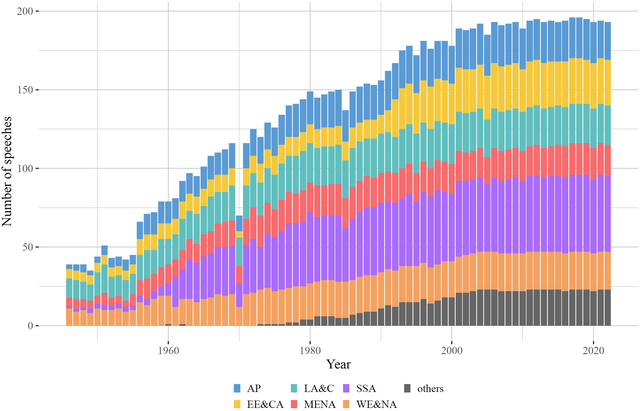

The core idea of the paper focuses on training a deep learning model utilizing an existing large language model (LLM) pre‐trained on a masked language modelling (MLM) objective that is fine‐tuned on a downstream research task (Raffel et al., Reference Raffel, Shazeer, Roberts, Lee, Narang, Matena, Zhou, Li and Liu2020). This is a supervised machine‐learning problem with a transfer learning approach for which training, testing and evaluation data are required. For the training and testing part, the paper utilizes a corpus containing 10,568 speeches in English presented by world leaders at the annual meetings of the United Nations General Assembly (Baturo et al., Reference Baturo, Dasandi and Mikhaylov2017). The speeches are a testimony of political positions from political leaders of all countries around the world in the past 77 years (see overview of frequencies of speeches per region in Figure 1). As most of the speeches were presented by the highest state representatives, such as presidents, prime ministers and ministers of foreign affairs, their nature often captures position‐taking meant for both domestic and international audiences (Jankin et al., Reference Jankin, Baturo and Dasandi2023; Proksch & Slapin, Reference Proksch and Slapin2015).Footnote 1 This is a robust database for training a machine‐learning model that aims to have a global scope and be versatile enough when it comes to contexts, regions and topics.Footnote 2

Figure 1. Distribution of speeches per geopolitical region in the UNGD corpus. Note: AP (Asia‐Pacific); EE&CA (Eastern Europe and Central Asia); LA&C (Latin America and the Caribbean); MENA (Middle East and North Africa); SSA (Sub‐Saharan Africa); WE&NA (Western Europe and North Africa); see the full description of the referred geopolitical regions in the V‐Dem codebook v13 (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish and Gastaldi2023).

Rather than using whole speeches as input data for training, I utilize a sliding window of sentence trigrams splitting the raw transcripts into uniform snippets of text mapping the political language of world leaders. As the goal is to model the varying context of presented ideas in the analyzed speeches rather than the context of the UN General Assembly debates, the main focus is on the particularities of the language of reference groups (authoritarian/democratic leaders). As the analyzed text is a high‐dimensional data source with high variability in terms of vocabulary and semantics, the approach multiplies the input data by a factor of one hundred (see section A2 in the Supporting Information Appendix for details on constructing the sentence trigrams).Footnote 3

As speeches are associated with speakers representing their countries, the speeches are inherently linked to them. This link can be used for extracting meaningful surrogate labels that are then used as training classes in a machine‐learning setup. To test the overall theoretical expectation about discourse differences, the speeches are merged with variables from the V‐Dem dataset, and each speech is populated with indicators characterizing the regime they represent. Although the V‐Dem dataset is not without flaws, it is the most robust attempt to resolve democracy's ambiguity problem (Boswell & Corbett, Reference Boswell and Corbett2021). Other indexes are of an inferior quality, either because of conceptualization, methodology or time period coveredFootnote 4 or their combination (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Henrik Knutsen, Krusell, Medzihorsky, Pernes, Skaaning, Stepanova, Teorell and Tzelgov2019), including systematic expert bias which is hard to eliminate entirely (Bergeron‐Boutin et al., Reference Bergeron‐Boutin, Carey, Helmke and Rau2024; Little & Meng, Reference Little and Meng2024). To train a machine‐learning model, the paper utilizes the electoral democracy index [EDI] (v2x_polyarchy), which addresses the question of to what extent is the ideal of electoral democracy, in its fullest sense, achieved in a country (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish and Gastaldi2023). As a continuous variable (0–1), it provides a broad enough scope for capturing specific political regime nuances associated with the contexts presented speeches come from. Although other variables might provide similar scope, the paper opts for a variable that bears the least cultural and ideological baggage (e.g., liberal or egalitarian values) yet includes the very essence of democratic systems with a high level of aggregation (i.e., the democratic context). It is important to stress that the variable does not operationalize authoritarianism per se but conceptually positions it on a continuum defined by a polyarchic status (polyarchy – non‐polyarchy).

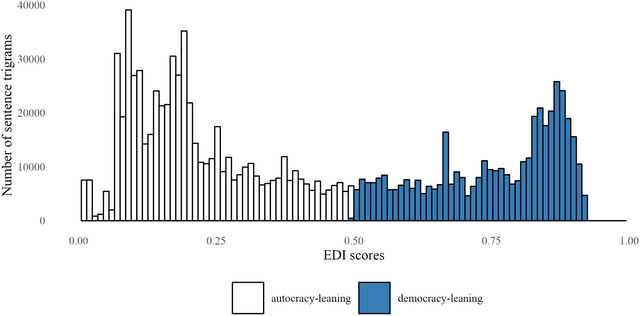

The logic of preprocessing textual data for the machine‐learning setup follows the outline under which each sentence trigram inherits the EDI score of the original speech associated with a specific country. In this setting, the model does not care who is the actual author of the speech but from which country (and regime) it comes. It solely focuses on the task of learning the approximated EDI scores based on the textual input associated with them. The final dataset counts 1,062,286 sentence trigrams annotated with EDI scores inherited from the parent documents (μ = 0.430, 95 per cent CI [0.429, 0.430]). The distribution of scores of all sentence trigrams used for the training is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Distribution of EDI scores across the corpus of sentence trigrams (UNGD corpus).

Methods: Weak supervision and deep learning

The following section summarizes the modelling pipeline for mapping authoritarian narratives and formalizes it as a feature extraction task. In this context, I use pre‐trained transformer models (LLMs) and fine‐tune them on a regression task that aims to approximate representation associated with values of the electoral democracy index [EDI] (v2x_polyarchy). The paper relies on a setup characterized as weak supervision under which sentence trigrams are the input data for the learning task, and the EDI scores act as surrogate labels that link the raw text to speakers and then to the regimes they represent. It means the labels/values assigned to individual trigrams do not necessarily reflect upon the actual content but rather the context they come from (authoritarian and democratic speakers and their discourse). This approach alleviates some of the burdens of producing a high‐quality annotation for training data which is both an expensive and time‐consuming task. The setup for this paper relies on a form of weak supervision that assumes that information about assigned labels is not always ground truth and there is an acknowledged but generally unknown noise (random error) in the quality of used labels (Zhou, Reference Zhou2018, pp. 49–50).Footnote 5

Rather than trying to correct the imperfect labels, the analytical pipeline uses them as they are and relies on the tuning effect of the applied machine learning algorithm. More specifically, a sentence trigram that is assigned an index with a lot of noise (i.e., an authoritarian leader using a common phrase from democratic discourse but still having a label for being authoritarian) is processed in combination with other semantically similar instances existing in training data but having substantially less noise (i.e., text excerpt from democratic discourse presented by a democratic speaker). This is the practical implication of the hypothesis that there is a meaningful difference in the political discourse of democrats and authoritarians. When the model is then applied to the same or similar text excerpt, the inferred index will be a generalized approximation of the prevailing value as represented in training data. This allows us to identify text segments in speeches made by authoritarians that are common in narratives of democratic leaders but also vice versa. In plain terms, the model can learn the prevailing representation of modelled discourse, which weighs in the overall dominance of labels in training data.

In order to train a well‐performing model, the training setup works with an optimization procedure for tuning the hyperparameters. The procedure aims to find a model that performs best on the evaluation datasets, simulating the performance of a model in a real‐world setting. First, the full corpus of sentence trigrams counting 1,062,286 instances is split into training (80 per cent) and testing (20 per cent) datasets (sampling is done on the level of documents). The testing dataset is used primarily for monitoring the inference capacity of the model during the training and not for actual assessment of the model's performance. The reason for this comes from the overall learning task, which aims to learn the prevailing index value [EDIn] rather than the exact value that might be noisy. Moreover, the decision also addresses the potential issue of cross‐contamination coming from a relatively closed system of UNGD debates and the potential spill‐over effect that is hard to control (e.g., one country can talk about same or similar agenda more often).

The training setup starts with the set of four LLM models – BERT‐base‐cased (Devlin et al., Reference Devlin, Chang, Lee and Toutanova2019), RoBERTa‐base (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ott, Goyal, Du, Joshi, Chen, Levy, Lewis, Zettlemoyer and Stoyanov2019), XLM‐RoBERTa‐base (Conneau et al., Reference Conneau, Khandelwal, Goyal, Chaudhary, Wenzek, Guzmán, Grave, Ott, Zettlemoyer and Stoyanov2020) and ELECTRA‐base (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Luong, Le and Manning2020). The goal is to select a model architecture that might perform the best on the learning task and then find the best hyperparameters for minimizing the error rate. All examined models are based on the transformer architecture, powering many of the state‐of‐the‐art text classification models (Laurer et al., Reference Laurer, Atteveldt, Casas and Welbers2023; Merritt, Reference Merritt2022; Vaswani et al., Reference Vaswani, Brain, Shazeer, Parmar, Uszkoreit, Jones, Gomez, Kaiser and Polosukhin2017). Technical aspects of the training process and the detailed results are summarized in the Supporting Information Appendix, section A3. The final model, henceforth referenced as the authdetect model, is made available to the public via the HuggingFace hub as well as the accompanying data repository. The evaluation of the model is performed on two external evaluation datasets – Maerz & Schneider Corpus (MS Corpus) and Internet Archive Corpus (IA Corpus). These datasets have formally nothing to do with the training data apart from being speeches of a political nature presented by world leaders and the highest state officials. The evaluation setting simulates the real‐world applications of the model many political scientists can relate to (i.e., using the model for inference on their own data). Technical aspects of the evaluation datasets are introduced in the Supporting Information Appendix, section A4. All replication scripts and referenced datasets are available in the online repositories accompanying the paper.Footnote 6 A walkthrough tutorial for experimenting with the model right away is presented in a Google Colaboratory notebook that comes with a free GPU runtime.Footnote 7

Results

Evaluation dataset #1: Maerz & Schneider corpus

The model's predictive power can now be fully evaluated in more detail on data collected by Maerz and Schneider (Reference Maerz and Schneider2020) (see Appendix, section A4 for more details). I cleaned up the dataset of entries that appear to be very short fragments of speeches, so only texts with more than six sentences (or four trigrams)Footnote 8 are kept for classification. Additionally, I had to filter out speeches collected from Poland and Turkey due to systematic inconsistencies in their content, probably caused during the scraping process.Footnote 9 The final number of analyzed documents is thus 3,777. Each speech is pre‐processed for sentence trigrams and analyzed for EDI scores. The scores are then aggregated into a ratio of sentence trigrams per document being classified as loaded in authoritarian discourse (where EDI ≥ 0.5: sentence trigram is more loaded in democratic discourse [0]; EDI < 0.5: sentence trigram is more loaded in autocratic discourse [1]). Unfortunately, there is no objective reference that would tell us how well the documents’ scores describe reality. We just assume they reflect upon the complexity of authoritarian and democratic discourse.

To evaluate the above‐mentioned assumption, the scores are validated using two scenarios. First, ratio of authoritarian sentence trigrams is re‐coded into binary categories and evaluated on the task of detecting the source of the speeches and classifying it as either associated with authoritarian or democratic leaders. As the model is trained for detecting authoritarian and democratic discourse, it should be able to distinguish the predominant source of authoritarian/democratic signals in the processed data. This is a crude binary classification task that is very common in validation tests in computer science. Furthermore, it mirrors the binary classification framework that Maerz and Schneider rely on in their paper. Finally, it reflects upon still relevant debate in democratic theory about what democracy is and is not (Sartori, Reference Sartori1987; Schmitter & Karl, Reference Schmitter and Karl1991). The second validation scenario relies on continuous values, introducing more granularity into the data and aligning with the argument that polyarchic status exists on a continuous scale (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Henrik Knutsen, Krusell, Medzihorsky, Pernes, Skaaning, Stepanova, Teorell and Tzelgov2019). Both approaches tell a slightly different story about how we study authoritarian and democratic regimes. The most important thing is they are mutually congruent.

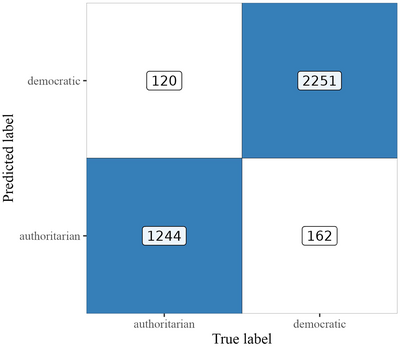

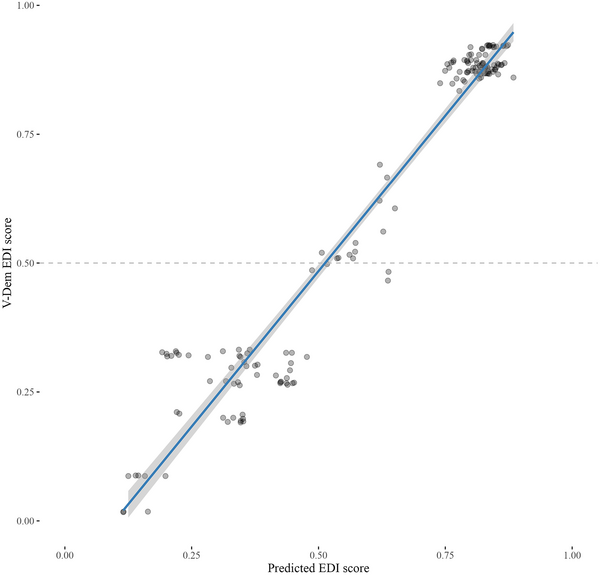

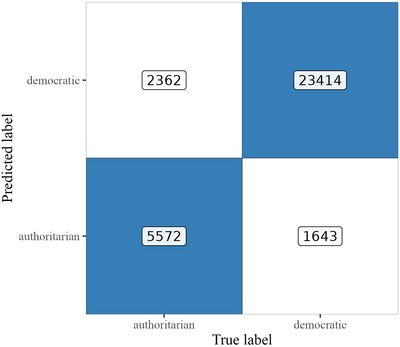

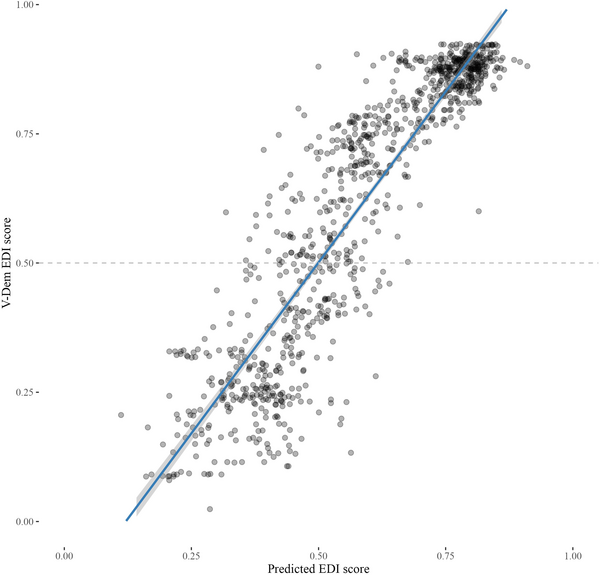

Figure 3 (confusion matrix) summarizes the performance of the final model on the binary classification task using the reference categories for democracy (true negative) and autocracy (true positive) from the original dataset by Maerz and Schneider hand‐coded as a binary variable. The evaluation is done against the re‐coded EDI values as an autocracy loading [AL] (ALn ≤ 0.5: democracy; ALn > 0.5: autocracy). The performance of the model is high, substantiating its capacity to pick up discourse associated with democratic leaders on the one hand and autocratic leaders on the other: Accuracy = 0.925; macro F1 = 0.941, Precision = 0.933 and Recall = 0.949. Again, this result comes from a dataset that has nothing to do with the training data and the model should not have seen it before. Apart from this traditional binary classification logic, Figure 4 presents the performance of the model on the task of predicting the correct country‐level EDI score as a mean value of the scores of individual documents on a yearly basis. The results are equally robust (ρ = 0.971, SE = 0.019, adj. R2 = 0.942, p < 0.001). Supporting Information Appendix section A4, Figure A4.2 provides a disaggregated country‐level overview, offering much more detail on the model's predictive power for each country and year. Finally, it is crucial to acknowledge that many of the identified misclassifications are expected and desirable as they empirically reflect upon the hypothesis that democratic leaders can engage in authoritarian discourse and authoritarian leaders in democratic discourse. The model can indicate when this happens (see discussion on false positives and false negatives below).

Figure 3. Confusion matrix with binary classification results on evaluation dataset #1 (M&S Corpus). Note: Numbers in the confusion matrix depict counts of classified documents per category.

Figure 4. Visualization of predicted and real EDI scores (M&S corpus).

Evaluation dataset #2: Internet archive corpus

Although the first evaluation dataset has shown that the model can accurately detect discourse associated with authoritarian and democratic leaders outside its main domain (the UN debates), the character of the corpus and the way the speeches were collected might positively affect the performance of the model. In order to validate the robustness of the model on a more global scale, I have collected 32,991 English speeches from 100 countries using Internet Archive archiving service (see Supporting Information Appendix, section A4 for more details). Although the dataset is not balanced and is skewed toward English‐speaking countries and those that see English as simply a useful language for communication, the model's predictive power can be explored in the same way as the speeches collected by Maerz and Schneider are. True labels are obtained from country–year EDI scores and speeches inherit them based on the source (the website of the world leaders) and their timestamp. The validation setup follows the outline presented in the previous section (binary classification and regression). Figure 5 (confusion matrix) summarizes the performance of the model on the binary classification task, and Figure 6 visualizes the predictive power of the model when it comes to the aggregated country‐level data (i.e., a comparison of the mean EDI scores per country per year against the real V‐Dem EDI scores). Reference categories of positives and negatives are identical to the previous section. The predictive power is again high, although a bit lower than what I reported before: Accuracy = 0.879; macro F1 = 0.921, Precision = 0.934 and Recall = 0.908 for the binary classification task; and ρ = 0.907 (SE = 0.013) and adjusted R2 = 0.822 for the EDI country level inference (p < 0.001). The decrease (in comparison to the previous dataset) can be explained by the character of the dataset as well as more noise in the data itself. That, however, does not mean the model performs poorly. Similar to the previous evaluation dataset, misclassifications are expected and much desired. They further substantiate the argument that leaders of democratic countries can routinely engage in authoritarian discourse while authoritarian leaders can sound like any Western democratic leader. Similar to the M&S corpus, Supporting Information Appendix Section A4, Figure A4.3 presents a disaggregated country‐level overview of the model's performance for each country and year.

Figure 5. Confusion matrix with binary classification results on evaluation dataset #2. Note: Numbers in the confusion matrix depict counts of documents per category.

Figure 6. Visualization of predicted and real EDI scores (IA corpus).

Although the statistical analysis and presented tests show the model performs well, confusion matrices and performance indicators tell us very little about what the model does under the hood. The following sections address that and present an exploratory data analysis of the most typical classification outputs. The discussion is accompanied by the analysis of integrated gradients as an additional check of the model's internal logic (Janizek et al., Reference Janizek, Sturmfels and Lee2020). Due to limited space, the analysis is placed in the Supporting Information Appendix, section A5. Although this cannot be considered an exhaustive account of what the model considers to be democratic/authoritarian discourse, it provides important anecdotal evidence on the integrity of the model and unveils a little bit of the black box the model is considered to be.Footnote 10

Discourse of authoritarians and democrats: True positives and true negatives

Out of 3777 speeches in the Maerz & Schneider corpus, 3,479 were classified in the reference category defined by the regime they originate from. In the Internet Archive corpus, 27,290 out of 32,991 analyzed speeches were correctly assigned to their natural reference categories either as true positives or true negatives. True positive can be simply understood as a speech classified by the model as coming from a leader of an authoritarian country matching the (true) reference category (authoritarian context). The same goes for true negatives referring to the matching classification of (true) referenced category for democratic discourse presented by democrats. What are these classifications about? Section A5 in the Supporting Information Appendix presents snippets of text from correctly classified documents that can be considered prime examples of their reference categories (Examples 1–12; three per category in each corpus). In other words, it means their respective scores are strongly embedded in the reference categories (i.e., the upper and lower bounds of the scale) and can be considered to be the most typical cases. These are explored manually, and the most representative examples are further discussed.

Although any kind of discourse summarization is primarily bound to the evaluation datasets, which cannot be considered fully representative of the political discourse of authoritarians and democrats on a global scale (due to the strategies by which they were collected; see Supporting Information Appendix, Section A4), at least preliminary insights can be gathered from the overview. One key observation is that references to strong religious, national and political authorities often act as important markers of authoritarian discourse represented in both the M&S and IA Corpora (true positives). The examples include discourse on almighty God and its will as well as religious references in general (Example 1: […] with the help of Allah, to support and strengthen our security capabilities by all means […]; Example 2: We must resort to the Quran), commemoration practices focused on past struggles and sacrifices and the glorification of the nation (Example 3: Our people accomplished the immortal feat of saving their homeland; Example 4: […] the cure is inside the country, and the problems can only be solved by the people) and finally, direct references to authority and power (Example 5: […] an outstanding leader guarantees the self‐respect and prosperity of a country and nation; Example 6: […] the invaluable heritage of the great scholars has become a priority of our national policy).

The examples above stand in sheer contrast to the prime examples of democratic discourse that is often filled with goodwill (Example 7: We in the Nordic countries must safeguard our openness to the world around us; Example 8: Our two countries are partners who share fundamental values, and we closely cooperate in the international community), support and development (Example 9: The overall goals of this programme are to support sustainable development in the region; Example 10: It will come through technology and innovation and the entrepreneurship of our industry leaders […]) and positive signalling (Example 11: The Danish Presidency will make an all‐out effort during the next six months to ensure that the EU continues to produce tangible results; Example 12: […] the chance to host a nine‐day event featuring 21 different sports is a thrill for everyone […]).

These examples can be considered the usual suspects in terms of what the model considers to be part of democratic and authoritarian discourse. However, not every sentence trigram must be as intuitive. It is important to emphasize again that the model is trained for the identification of authoritarian discourse, not authoritarianism itself. It means that topics, issues and references primarily associated with speeches presented by authoritarians but with no apparent authoritarian attribution will still be considered as a discourse of authoritarians and vice versa. The following section presents the overview of misclassifications which demonstrates it in more practical terms. The argument is further developed in the Supporting Information Appendix, section A6.

Mislabelling analysis: False positives and false negatives

Although the quality of the model is primarily judged based on its capacity to predict true reference categories, false predictions can be equally informative. This is especially relevant for supporting the argument that democrats can engage in authoritarian discourse and vice versa. It means the model ought not to discriminate based on the explicit source of the signal. Out of 3,777 speeches in the M&S corpus, 282 were misclassified for being either false positives or false negatives. In the IA corpus, 4,005 out of 32,991 texts were flagged as misclassifications. The category of false positive refers to speeches made by democratic leaders that are labelled as more aligned with authoritarian discourse (in a binary sense). False negative refers to the opposite setting – a speech made by authoritarian leaders being more in line with what is expected in the democratic discourse. The examples discussed below are speeches with the highest error rate and the biggest difference between predicted and surrogate labels. They are selected manually from a ranked list of misclassified speeches, with the ratio of error defining the rank. In this context, they can be understood as the most typical examples per the discussed categories.

When we explore false positives in the M&S corpus, 162 speeches coming from supposedly democratic leaders are assessed as being more associated with authoritarian discourse. Interestingly, 139 (85.8 per cent) of these misclassified cases come from Edi Rama, Prime Minister of Albania, and 19 (11.7 per cent) from Viktor Orban, Prime Minister of Hungary. Both can be considered controversial leaders known for authoritarian practices and many corruption scandals (Freedom House, 2022; Freedom House, 2023b). Section A5 in the Supporting Information Appendix presents three excerpts illustrating examples of authoritarian discourse coming from supposedly democratic leaders. Some fit the profile of authoritarians discussed in the previous section (Example 13: […] we must not forget those who contributed to its [WWII] ceasing; Example 14: […] opening the Socialist Party to everyone who want to see their power of change and join us to enhance our joint power of change), but the model sees authoritarian discourse also in references to collaboration that has some historical baggage (Example 15: Here in Vietnam there are three thousand honoured citizens who completed their university education in Hungary).

When it comes to false negatives, 120 speeches in the M&S corpus are classified as coming from democratic leaders while being presented by speakers representing authoritarian regimes. The majority of the misclassifications (101 speeches; 82 per cent) come from the President of the Russian Federation, Vladimir Putin. This is an interesting finding as it aligns well with the long‐perceived notion of Vladimir Putin as a strategist who can skilfully adapt his discourse to the audience he speaks to (Dyson & Parent, Reference Dyson and Parent2018; Galeotti, Reference Galeotti2019). In general, many of the misclassified speeches in the list are formal addresses at business fora, gallery openings and galas and routine occasions where international and business actors are either present or are considered part of the target audience. This is not symptomatic only to Vladimir Putin. Many authoritarians can engage in a similar discourse easily. An overview of examples in the Supporting Information Appendix, section A5, supports this assessment. These speeches often share the notion of praise (Example 16: We applaud the efforts of chairman Peter Savill and the British Horseracing Board in attempting to put the sport on a sounder financial footing), positive signalling (Example 17: […] we all have great respect and admiration for you both as the wife of the first president of Russia and, of course, as an unfailingly kind and very considerate person […]) and vague diplomatic cheap‐talk that is probably more common among democratic leaders (Example 18: Today's visit is a fitting symbol of the growing bonds of friendship, shared interest and mutual understanding between our two peoples.).

The IA corpus is very similar. When it comes to false positives, the above‐mentioned patterns often repeat (Example 19: […] it is also important for us to recall and revive our more immediate past which has bequeathed to us the heroic values of patriotism […]; Example 20: […] we must renew that crusading impulse on which we entered the war and met its darkest hour […]). Interestingly, the role of a strong leader is also demonstrated in the manifestation of political authority. As a more common feature among authoritarian speakers, it translates to flagging many of such narratives as leaning more towards authoritarian discourse, even though there is objectively very little authoritarian substance (Example 21: […] the Executive Order blocks all property and interests in property of DAB that are held in the United States by any United States financial institution).

Regarding false negatives in the IA corpus (i.e., authoritarians talking like democrats), most speeches concern business, international cooperation and cultural events, the patterns I have already discussed above. There is very little of what can be called an apparent authoritarian discourse. Probably the best example is a group of speeches presented by Viktor Orban, the Prime Minister of Hungary, with the discourse falling within the standard European cultural and political tradition, yet coming from somebody that is considered to have an authoritarian leaning (Example 22: […] we in the V4 seek cooperation with Europe's other countries). The same goes for references considering ordinary things such as family (Example 23: Families are the natural grouping where we find love, support and fulfillment), or simple positive signalling (Example 24: […] we hope to see the realization of a sovereign, independent, united and viable Palestine, co‐existing peacefully with Israel).

Conclusion

All models are wrong, but some are useful (Box, Reference Box, Launer and Wilkinson1979). The paper presents a model trained for detecting authoritarian narratives in political discourse. It is not intended to say whether somebody is an authoritarian or not but whether the discourse produced by a person aligns more with a discourse championed by leaders of democratic countries or known authoritarians. That does not imply an explicit authoritarian or democratic rhetoric but rather patterns in discourse combining lexis, semantics, syntax, issues, topics and frames that are substantially associated with a specific political group. In other words, what is considered to be associated with authoritarian discourse does not have to be explicitly authoritarian in a political sense. Even authoritarian discourse can be acceptable, morally correct and in line with democratic values. However, the fact that certain narratives are championed by authoritarians in a more substantive way makes them a natural part of their discourse. Even authoritarians can talk about human rights without a hard‐line authoritarian outlook (Ignatieff, Reference Ignatieff2001). That discourse is, however, still a discourse of authoritarians.

Building on the advancements in the field of natural language processing, the paper outlines a strategy for training machine‐learning models in political science utilizing weak supervision with surrogate labels on top of LLMs. The discussed tests show the approach works when applied to a straightforward classification problem, aggregating more fine‐grained outputs of the trained model. However, the model is not a universal classifier and needs to be applied carefully with regard to the character of training data and the kind of biases that exist there (see section A6 for more details). Although the model is trained on a fairly representative corpus of speeches, the corpus has its intrinsic limitations. Language of the UN debates and topics being discussed translate into what the model considers to be an authoritarian discourse on the one hand and a democratic discourse on the other. Despite this cautious remark, the performance, stability and robustness of the authdetect model indicate that a specific environment of the training data defined by the UN General Assembly travels well across countries, topics and issues. The paper shows that large language models can effectively learn at least some of the latent concepts in political science and infer them effectively over large corpora of unseen data.Footnote 11

The overall contribution of the paper can be summarized around multiple points. First, the model does a very good job of detecting authoritarian discourse, especially when it comes to high‐abstract aggregation on the level of documents and in a context where straightforward alignment with democratic or authoritarian discourse is expected. This translates to an easy‐to‐use processing pipeline that can empirically analyze authoritarian loading in a large number of political speeches across contexts and time. Although trained on a very specific dataset, the evaluation has shown how robust the model is in real‐life settings. A wide range of stakeholders, including NGOs, governmental agencies and media, can use the model in their analytical work and monitor public discourse for authoritarian signals. It can be integrated into an automated pipeline that will continuously collect textual data and analyze trends in real time, creating a form of early‐warning system for monitoring authoritarian discourse.

When it comes to the potential use cases of the authdetect model, the strategies are flexible. The most promising scenario concerns extracting authoritarian loading from political speeches measured as a ratio of sentence trigrams loaded in authoritarian discourse, an average EDI score across the whole document or set of documents, or different weight‐based aggregation formulas. These indexes can then be used in all sorts of regression models social scientists are well accustomed to. Among other things, the setup allows us to answer important research questions about drivers of authoritarianism, such as whether populist parties are the main champions of the authoritarian wave globally, whether authoritarian discourse is genderized, what is the role of conservative political parties in normalizing authoritarian discourse among mainstream political parties, how much left‐wing political parties from Central and Easter Europe manifest their Communist (authoritarian) heritage, what drives authoritarian discourse in democratic politicians, or what topics do activate it. For more qualitatively oriented scholars, the most interesting application includes detecting and extracting excerpts loaded in a specific type of discourse (democratic/authoritarian) and analyzing them with qualitative methods. This is crucial for understanding how traditional political parties adapt to new situations and narratives and how this manifests in their political preferences or whether and how authoritarian discourse differs in left‐ and right‐wing political parties. The model allows studying political discourse both synchronously and asynchronously.

The model's notable potential lies in its capacity for near real‐time monitoring of political elites within highly dynamic contexts. We should be able to track authoritarian and democratic discourse on the level of single speeches and on a daily basis of any political leader producing written records on her/his political activities. We should be able to identify segments of authoritarian discourse in democrats and democratic discourse in autocrats. And finally, we should manage to trace the development of leaders and understand what makes them democratic and authoritarian as a part of an early‐warning system. We can envision an analytical pipeline that annotates textual data in real time and maps the authoritarian trends in discourse. The model can be served as an online service being fetched with data automatically producing scores that can be further processed. In a retrospective setup, the model can annotate 20 years of the political discourse of a leader who started as a liberal and turned authoritarian and explore when this happened and what the early signals were. Finally, the model can be helpful in situations when not enough data for high‐quality assessment is available. Typically, micro‐states or small political parties can be analyzed as an aggregated set of speeches that then position the discourse along the predefined polyarchic scale. This approach is embodied in the assumption that democratic and authoritarian discourse is not a strong binary category but a continuous scale that is situational and dynamic (Glasius, Reference Glasius2018).

When it comes to methodological advancements, the paper is one of the first demonstrations of transfer learning in political science utilizing LLMs and training data, which can be considered big in terms of traditional social science research. The discussed strategies and tests showed that transfer learning is viable and a promising strategy for machine learning applications in political science. As a proof‐of‐concept, the paper further demonstrates the potential of fine‐tuning large language models on downstream tasks focused on latent concepts, such as authoritarianism (see a note on fine‐tuning in the Supporting Information Appendix, section A6). However, the advancement does not stop here. Similar models could be potentially trained for many political science concepts, including populism, nationalism or liberalism. Moreover, using the principles of transfer learning, the model can get more specialized both in terms of field of application (i.e., policy) and focus (e.g., regional differences or cultural context). Future applications can easily incorporate more up‐to‐date data or more data in general and train the whole model from scratch for even better performance (see the Supporting Information Appendix, section A6 for more details). Unlike many machine learning applications in political science, the authdetec model can be considered to be a dynamic model that can evolve and be developed with new data without the need for extensive resources (e.g., the final model took approximately 3 h and 44 min to train).

The paper shows how beneficial language modelling can be for mapping political concepts. It argues that with a little theoretical innovation, political scientists can tackle complex problems with machine‐learning solutions that would otherwise require substantial resources and time. The authdetect model is a proof‐of‐concept example that this is possible. Moreover, as a stand‐alone model, anybody can use it out‐of‐box for inference or further fine‐tuning. The paper facilitates it by publishing all training and inference scripts as well as the final model under a Creative Commons license. It is also accompanied by a walkthrough tutorial for a quick and easy inference pipeline (i.e., automated annotation of user's own data) using Google Colaboratory with free GPU runtime (see footnotes 6–8 for details).

Funding

This work was supported by the Excellence Fellowship of Radboud University [grant number 2702184].

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my colleagues Haley Sedlund, Andrej Zaslove, Maurits Meijers, Reinout van der Veer and Nikola Ljubešić for their invaluable feedback and insightful discussions throughout the development of this paper. I also extend my appreciation to the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful and constructive comments. Their careful reading and suggestions have helped to refine the arguments and improve the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Replication code, notebooks and all data for this article are published in the Zenodo data repository: https://zenodo.org/records/13920400. The final model is also uploaded to the Hugging Face Hub: https://huggingface.co/mmochtak/authdetect. The paper is also accompanied by a video tutorial on how to use the model on users' own data: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CRy9uxMChoE.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: