Introduction

Visual stimuli are comprised of many features competing for representational priority given limited attentional resources (e.g. Desimone & Duncan, Reference Desimone and Duncan1995; Kastner & Ungerleider, Reference Kastner and Ungerleider2000). For example, emotionally salient stimuli are often associated with rapid temporal region activation (Luo et al. Reference Luo, Holroyd, Majestic, Cheng, Schechter and Blair2010). However, if other stimulus features are more task relevant, those features receive more attentional resources, while emotional aspects are seemingly de-emphasized (e.g. Ochsner & Gross, Reference Ochsner and Gross2005). In other words, visual attention can amplify specific stimulus features, which affects activation across brain areas critical to representing those particular properties. Attention allocation is generally task driven, and studies show that even emotionally salient stimuli can be associated with reduced activity in regions like the amygdala if emotional properties of the stimuli are not task relevant (e.g. Blair et al. Reference Blair, Smith, Mitchell, Morton, Vythilingam, Pessoa, Fridberg, Zametkin, Nelson, Drevets, Pine, Martin and Blair2007; Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Nakic, Fridberg, Kamel, Pine and Blair2007).

Many psychological disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), are associated with aberrant attention allocation patterns and altered stimulus representations across brain regions (Blair et al. Reference Blair, Vythilingam, Crowe, McCaffrey, Ng, Wu, Scaramozza, Mondillo, Pine, Charney and Blair2013). For example, PTSD is associated with attentional perseverance to threat, which can lead to hyper-processing of emotional aspects of stimuli (e.g. increased activation in the amygdala; e.g. Rauch et al. Reference Rauch, Shin and Phelps2006). The elevated emotional activation noted in PTSD does not appear to dissipate as much as it does in healthy individuals (Blair et al. Reference Blair, Vythilingam, Crowe, McCaffrey, Ng, Wu, Scaramozza, Mondillo, Pine, Charney and Blair2013); instead, emotional representations within the amygdala and similar regions abnormally persist even when attention appears to be allocated to other stimulus features (Luo et al. Reference Luo, Holroyd, Majestic, Cheng, Schechter and Blair2010; Todd et al. Reference Todd, MacDonald, Sedge, Robertson, Jetly, Taylor and Pang2015). Alternatively, prefrontal areas typically guiding attentional selection and emotional regulation may not be properly engaged in PTSD patients (e.g. Leskin & White, Reference Leskin and White2007; Aupperle et al. Reference Aupperle, Melrose, Stein and Paulus2012; McDermott et al. Reference McDermott, Badura-Brack, Becker, Ryan, Bar-Haim, Pine, Khanna, Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson2016a ). Of course, both of these factors may be involved (Pannu Hayes et al. Reference Pannu Hayes, Labar, Petty, McCarthy and Morey2009; Cisler et al. Reference Cisler, Wolitzky-Taylor, Adams, Babson, Badour and Willems2011). A key barrier to better characterizing these alterations in PTSD is that the neural timing of attentional allocation and emotional regulation during stimulus processing is not understood. For example, individuals with PTSD may have heightened and/or sustained activity within emotional processing regions as compared with those without PTSD. Alternatively, PTSD may be associated with relatively less activity within emotional regulation areas, and/or this activity may not be sustained over time.

The emotional Stroop task (EST) has been used to monitor attention allocation during processing of emotionally charged stimuli (e.g. Williams et al. Reference Williams, Mathews and MacLeod1996), specifically because participants are asked to attend to non-emotional aspects of the stimuli. The EST is a variant of the classic Stroop task in which participants name aloud the ink color of printed words (Stroop, Reference Stroop1935). However, in the EST, words vary in emotional salience. For example, words may be neutral (e.g. ‘file’) or negative (e.g. ‘bomb’). Individuals with attention allocation alterations resulting from anxiety disorders often respond later (i.e. delayed latency) to negative words compared with other words (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Mathews and MacLeod1996; Metzger et al. Reference Metzger, Orr, Lasko, McNally and Pitman1997; McNally, Reference McNally1998), and this especially is true when negative words are personally relevant (e.g. combat-related words for veterans with PTSD; Riemann & McNally, Reference Riemann and McNally1995; Becker et al. Reference Becker, Rinck, Margraf and Roth2001; Phaf & Kan, Reference Phaf and Kan2007). Metzger et al. (Reference Metzger, Orr, Lasko, McNally and Pitman1997) suggested that patients’ longer color-naming latencies for threat-related words arise because emotional aspects of words draw attention and dominate representations, even when the emotionality of the words is task irrelevant. Healthy individuals typically do not produce different color-naming latencies for the various EST list types (e.g. Compton et al. Reference Compton, Banich, Mohanty, Milham, Herrington, Miller, Scalf, Webb and Heller2003), probably indicating that they engage emotional regulation areas and focus on task-relevant word dimensions (Phaf & Kan, Reference Phaf and Kan2007; White et al. Reference White, Costanzo, Blair and Roy2015). Regarding neural correlates, recent functional neuroimaging studies indicated that the EST elicits activation within the prefrontal cortex (PFC), cingulate areas, emotional processing centers in medial temporal areas, and in other brain regions (e.g. Mitterschiffthaler et al. Reference Mitterschiffthaler, Williams, Walsh, Cleare, Donaldson, Scott and Fu2008; Ovaysikia et al. Reference Ovaysikia, Tahir, Chan and DeSouza2011; Dresler et al. Reference Dresler, Attar, Spitzer, Lowe, Deckert, Buchel, Ehlis and Fallgatter2012; Hwang et al. Reference Hwang, White, Nolan, Sinclair and Blair2014). However, the temporal dynamics across this circuit have not been determined, and such data are imperative to understanding the precise functional contribution of these brain regions to EST processing, especially in those with PTSD.

Therefore, in the current study, we examined the dynamic time course of neural activity across this circuitry by collecting magnetoencephalography (MEG) data while combat veterans with and without PTSD performed an EST. The spatiotemporal sensitivity of MEG makes it uniquely suited for probing emotional processing during the EST (Engdahl et al. Reference Engdahl, Leuthold, Tan, Lewis, Winskowski, Dikel and Georgopoulos2010; Georgopoulos et al. Reference Georgopoulos, Tan, Lewis, Leuthold, Winskowski, Lynch and Engdahl2010; James et al. Reference James, Engdahl, Leuthold, Lewis, Van Kampen and Georgopoulos2013, Reference James, Belitskaya-Lévy, Lu, Wang, Engdahl, Leuthold and Georgopoulos2015; Anders et al. Reference Anders, Peterson, James, Engdahl, Leuthold and Georgopoulos2015; Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Heinrichs-Graham, Proskovec and McDermott2016), because MEG allows the amplitude and duration of neural activity to be precisely quantified during task performance. Our primary goal in this study was to identify the spatiotemporal dynamics of attentional control and emotional regulation during the processing of neutral and emotionally salient stimuli (both personally relevant and personally irrelevant) in combat veterans with and without PTSD. We hypothesized that veterans without PTSD would initially activate emotional representations of threatening stimuli (e.g. Luo et al. Reference Luo, Holroyd, Majestic, Cheng, Schechter and Blair2010; Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Gonsalvez and Johnstone2013), but that such activity would dissipate and emerge in executive control regions during early processing, and then be largely sustained until task completion. This overall pattern of activation would be consistent with White et al. (Reference White, Costanzo, Blair and Roy2015), who examined a sample of combat veterans without PTSD using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and a similar task. Thus, we predicted veterans without PTSD would show sustained responses in prefrontal cortices during combat-related and general threat word processing compared with neutral words, mainly reflecting executive control during EST processing. We hypothesized that veterans with PTSD would engage emotional processing areas such as the amygdalae and other medial temporal regions during initial processing of threatening stimuli, and that activity would be sustained in these regions throughout the task. Finally, we hypothesized that veterans with PTSD would show reduced neural activity in prefrontal cortices relative to veterans without PTSD while processing combat-related words, but not general threat or neutral words. Depending on the time course, such findings would indicate aberrant attention allocation and/or emotional regulation in veterans with PTSD.

Method

Participants

We recruited male combat veterans from the Omaha area; 31 had PTSD and 20 did not; healthy veterans did not have any psychiatric or neurological condition by history and evaluation with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; Sheehan et al. Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs, Weiller, Hergueta, Baker and Dunbar1998). PTSD was diagnosed or ruled out using the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; Blake et al. Reference Blake, Weathers, Nagy, Kaloupek, Gusman, Charney and Keane1995) and the F1/I2 rule (Weathers et al. Reference Weathers, Ruscio and Keane1999). For the F1/I2 rule, one is diagnosed with PTSD if they experienced trauma-related symptoms on the standard CAPS scale once or more in the past month and the severity of the symptoms was moderate, severe or extreme. Veterans with PTSD were not excluded for depression or anxiety symptoms frequently co-morbid with PTSD, but were free of other diagnoses according to the MINI (Sheehan et al. Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs, Weiller, Hergueta, Baker and Dunbar1998). Participants with and without PTSD were matched on age, ethnicity, education level and handedness. The two groups were matched on education level, but we did not administer a specific measure of general intelligence. General exclusionary criteria included medical diagnoses affecting central nervous system function, known brain neoplasm or lesion, history of significant head trauma, and ferromagnetic implants. Written informed consent was obtained and the Institutional Review Board of Creighton University approved the study.

EST

Participants completed the EST while seated in the MEG chamber. Task stimuli included three word lists: a combat-related threat list, a general threat list, and a neutral list. Each list contained 30 monosyllabic words. The combat-related threat list was intended to be personally relevant to combat veterans and was comprised of words related to things encountered in a war zone (e.g. ‘bomb’, ‘seize’); the general threat list contained words that were negative in valence, but not related to combat (e.g. ‘tax’, ‘witch’). The neutral list contained words that were non-threatening (e.g. ‘self’, ‘flour’). We determined list inclusion based on our judgements, and we asked a recent US military veteran to verify that words were included on the appropriate lists (e.g. that ‘bomb’ is a combat-related threat word). The three word lists were equated on various lexical features including: length, Hyperspace Analogue to Language (HAL) frequency (Lund & Burgess, Reference Lund and Burgess1996), orthographic and phonological neighborhood size. We balanced these lexical features across lists based on guidelines provided by a previous meta-analysis of the EST in behavioral studies (Larsen et al. Reference Larsen, Mercer and Balota2006). We used the English Lexicon Project database to determine average naming latency, naming accuracy, lexical decision time, and lexical decision accuracy for each word and equated the word lists (Balota et al. Reference Balota, Yap, Cortese, Hutchison, Kessler, Loftis, Neely, Nelson, Simpson and Treiman2007), so that the three lists did not differ from one another (all Fs < 1.09, p > 0.34). However, as expected, the lists did differ according to their emotional arousal and valence ratings (F 2,89 = 233.406, within-groups mean square = 0.111, p < 0.0001; F 2,89 = 273.218, within-groups mean square = 0.283, p < 0.0001, respectively). Arousal and valence ratings used Estes & Adelman's (Reference Estes and Adelman2008) normative ratings derived from healthy adults’ ratings of emotional arousal (1 being not arousing to 7 being highly arousing) and emotional valence (1 for the most negative to 7 for the most positive) for individual monosyllabic words. By design, our combat-related threat list words had higher arousal and lower valence ratings than neutral words (both t’s > 20.4 and p’s < 0.0001), but did not differ from the general threat words in arousal or valence (all t’s < 1.45 and p’s > 0.152). General threat words also had higher arousal and lower valence ratings than neutral words (both t’s > 19.22 and p’s < 0.0001).

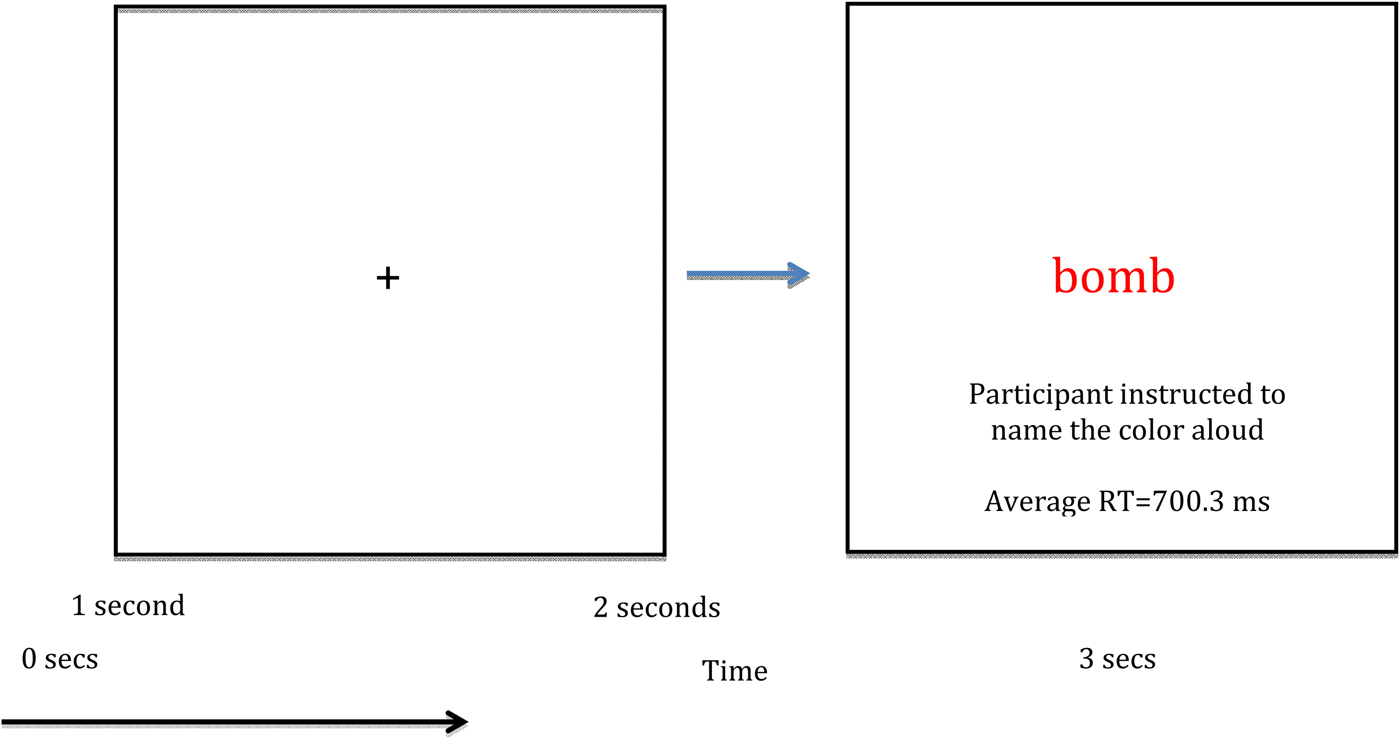

During a single MEG session, each 30-word list was presented three times, resulting in 270 total trials (90 neutral, 90 general threat, 90 combat related) separated into nine experimental blocks. A blocked design was selected because, as previous research noted, blocked designs are associated with more robust EST responses (Cisler et al. Reference Cisler, Wolitzky-Taylor, Adams, Babson, Badour and Willems2011). Participants were naïve to the existence of different word lists per block. We randomized word order within each list across presentation blocks. Within each EST trial, participants first viewed a fixation cross for 1 s, then viewed a list item (e.g. ‘bomb’) for 2 s. Participants were instructed to vocally respond as soon as possible to the list item (Fig. 1). An experimenter scored participant responses as correct (i.e. named the color correctly), incorrect, or as a noise trial (e.g. the participant coughed, etc.) using a keyboard attached to the stimulus presentation computer. Each word was centered on a screen at eye level approximately 110 cm from the head. Items were presented in red, blue, or green font, and item color was randomly assigned. Reaction times were measured using a dual-plane accelerometer attached to the lower lip and digitized at 1 kHz with the MEG data. Voice onset was determined by a sharp increase in the accelerometer signal amplitude for each person. This approach produces response time accuracy near 1 ms. Total MEG recording time was about 14 min per person.

Fig. 1. Single trial design and overall layout of the emotional Stroop task. RT, Reaction time.

MEG data acquisition and co-registration

With an acquisition bandwidth of 0.1–330 Hz, neuromagnetic responses were sampled continuously at 1 kHz using an Elekta MEG system with 306 magnetic sensors (Elekta, Finland). Using MaxFilter (v2.2; Elekta), MEG data from each participant were individually corrected for head movement and subjected to noise reduction using the signal space separation method with a temporal extension (Taulu & Simola, Reference Taulu and Simola2006). MEG data were then co-registered with structural T1-weighted MRI data using BESA MRI (V2.0; BESA GmbH, Germany).

MEG time-frequency transformation and statistics

Cardio-artifacts were removed from the data using signal-space projection, which was accounted for during source reconstruction (Uusitalo & Ilmoniemi, Reference Uusitalo and Ilmoniemi1997). The continuous magnetic time series was divided into epochs of 3.0 s duration (−1.0 to 2.0 s), with 0.0 s being the onset of the word and the baseline being the −0.2 to 0.0 s time bin. Epochs containing artifacts were rejected based on a fixed threshold method, supplemented with visual inspection.

Artifact-free epochs were transformed into the time-frequency domain using complex demodulation (resolution: 2.0 Hz, 25 ms), and the resulting spectral power estimations per sensor were averaged over trials to generate time-frequency plots of mean spectral density. Sensor-level data were normalized by dividing the power value of each time-frequency bin by the respective bin's baseline power, which was calculated as the mean power during the −0.2 to 0 s time period. We then used a data-driven approach to derive the time-frequency windows of interest. Briefly, windows of interest were determined by statistical analysis of sensor-level spectrograms across the array of gradiometers during the first 1 s of stimulus processing (mean reaction time: 700.3 ms). To reduce risk of false positives, while maintaining sensitivity, we followed a two-stage procedure involving non-parametric permutation testing to control for type 1 error (Ernst, Reference Ernst2004; Maris & Oostenveld, Reference Maris and Oostenveld2007). This method has been extensively described in previous publications (Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Heinrichs-Graham and Becker2014, Reference Wilson, Heinrichs-Graham, Becker, Aloi, Robertson, Sandkovsky, White, O'Neill, Knott, Fox and Swindells2015; Heinrichs-Graham & Wilson, Reference Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson2015). Based on these analyses, the time-frequency windows containing significant oscillatory events across all participants were selected for imaging.

MEG source imaging and statistics

Cortical networks were imaged through an extension of the linearly constrained minimum variance vector beamformer, which employs spatial filters in the frequency domain to calculate source power for the whole brain volume (Gross et al. Reference Gross, Kujala, Hamalainen, Timmermann, Schnitzler and Salmelin2001; Hillebrand et al. Reference Hillebrand, Singh, Holliday, Furlong and Barnes2005). The single images were derived from the cross-spectral densities of all combinations of MEG gradiometers averaged over the time-frequency range of interest, and the solution of the forward problem for each location on a grid specified by input voxel space. Following convention, the power in these images was normalized per participant using a separately averaged pre-stimulus noise period of equal duration and bandwidth (Hillebrand et al. Reference Hillebrand, Singh, Holliday, Furlong and Barnes2005).

Normalized source power was computed for the selected time-frequency bands in each participant at 4.0 × 4.0 × 4.0 mm resolution. Prior to statistical analysis, each participant's functional images were transformed into standardized space and spatially resampled. The resulting three-dimensional maps of functional brain activity were statistically evaluated using a three-way mixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA), with group (two levels) as a between-subjects factor, and condition (three levels) and time (four levels; see below) as within-subjects factors. Follow-up t tests were conducted on significant interaction effects using a two-stage approach similar to the sensor-level analysis to control for type 1 error. Briefly, two-sample t tests were used to examine group effects per word list, whereas paired-samples t tests were conducted to probe word-list effects per group in each time-frequency bin of interest. In the first stage, t tests were conducted on each voxel and the output was thresholded at p < 0.05 to create statistical parametric maps (SPMs) showing clusters of potentially significant differences between groups (e.g. PTSD < controls) or conditions (e.g. neutral < general threat). In stage 2, a cluster value was derived for each cluster surviving stage 1, and permutation testing was used to test the significance of the observed clusters. For each comparison, at least 10 000 permutations were computed to build a distribution of cluster values.

Ethical standards

All procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Results

Behavioral performance

A part of this EST behavioral performance data was previously reported in a study of how attention training affects EST performance (Khanna et al. Reference Khanna, Badura-Brack, McDermott, Shepherd, Heinrichs-Graham, Pine, Bar-Haim and Wilson2016). Note that the current study includes 10 participants who were not in the previous study. For the 51 participants included in the current study, the mean age and educational levels did not differ between groups (p = 0.55 and p = 0.49, respectively). Mean and s.d. data are shown in Table 1. Consistent with enrollment criteria, veterans with PTSD had higher CAPS scores than veterans without PTSD even after controlling for combat exposure (t 38 = 10.95, p < 0.001).

Table 1. Demographic information and RTs for the two participant groups across the three lists

Data are given as mean (standard deviation) unless otherwise indicated.

RT, Reaction time; CAPS, Clinician Administered PTSD Scale; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Reaction time data were lost for nine participants (five with PTSD) due to a technical error. For the remaining 42 participants, a mixed-model ANOVA comparing naming latencies for each group across the three lists revealed an interaction (F 2,80 = 4.18, p = 0.019). There was no main effect of group or list, although both were suggestive (F 1,40 = 3.27, p = 0.078 for group, and F 1,40 = 2.61, p = 0.114 for list). To interrogate the interaction effect, we examined color-naming latencies for the three lists using paired-samples t tests in each group. We found veterans without PTSD showed no difference in color-naming latencies across lists (all p’s > 0.20), while veterans with PTSD displayed longer color-naming latencies for combat-related lists than neutral (t 25 = 2.58, p = 0.016) and general threat lists (t 25 = 2.23, p = 0.035). Color-naming latencies were marginally slower for general threat words as compared with neutral words (t 25 = 1.99, p = 0.058). The mean color-naming latencies and s.d.s per list for each group are reported in Table 1.

MEG sensor-level analysis

Sensor-level spectrograms were examined statistically using non-parametric permutation testing to derive precise time-frequency bins for follow-up beamforming analyses. These analyses indicated a significant cluster of sustained theta oscillatory activity (4–8 Hz) that began shortly after onset of the word and continued to the onset of the vocal response (p < 0.001, corrected). To evaluate the dynamics, we split this significant theta response into four non-overlapping time bins of 0.2 s duration (i.e. 0–0.2, 0.2–0.4, 0.4–0.6, and 0.6–0.8 s), and each time window was imaged for statistical analyses.

MEG imaging analysis

We initially conducted a 2 × 3 × 4 mixed-model ANOVA, with group as a between-subjects factor and condition and time as within-subjects factors. The results indicated a significant three-way interaction in multiple brain regions (F 6,588 = 2.12, p < 0.05; Fig. 2), group x condition (F 2,588 = 3.01, p < 0.05), group × time (F 3,588 = 2.62, p < 0.05), and condition x time (F 6,588 = 2.12, p < 0.05) two-way interactions and main effects of time (F 3,588 = 2.62, p < 0.05) and condition (F 2,588 = 3.01, p < 0.05). Note that these F values correspond to the threshold for a significant effect and not the peak voxel or cluster, and that multiple brain regions were significant for each interaction and main effect. To probe interaction effects, two-sample (between-group) and paired-sample (within-group) t tests were performed, with non-parametric permutation testing used to correct for multiple comparisons.

Fig. 2. Three-way interaction of group × condition × time. All three panels show brain regions exhibiting a significant three-way interaction effect (p < 0.05). Significant neural areas included the right inferior frontal, ventral frontal, and superior temporal regions, as well as the left amygdala (top panel). In addition, the three-way interaction was significant in the left inferior frontal gyrus and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex region (middle panel), as well as the cingulate cortices and superior frontal (bottom panel). All three panels have been thresholded at p < 0.05 and are displayed in radiological convention. The three-way interaction effect consisted of group (two levels; veterans with and without post-traumatic stress disorder), condition (three levels; combat-related threat words, general threat words, and neutral words) and time (four levels; 0.0–0.2 s, 0.2–0.4 s, 0.4–0.6 s, and 0.6–0.8 s). R, Right; L, left.

Between-group effects

For combat-related words, significant differences between veterans with and without PTSD emerged in the right ventral PFC in the 0.4–0.6 s time period and extended into the 0.6–0.8 s window. Differences in the latter window also included the right superior temporal cortices. In all cases, findings reflected significantly stronger theta activity in veterans without PTSD relative to those with PTSD (p < 0.05, corrected; Fig. 3). No other between-group comparisons were significant. To examine the relationship of these data with PTSD symptomatology, we conducted Spearman correlations using the peak voxel value in the right ventral PFC (RVPFC) cluster for the 0.4–0.6 s time window and individual CAPS scores, separately for the PTSD and the non-PTSD groups. Briefly, the strength of theta activity in the RVPFC was marginally correlated with CAPS in the non-PTSD group (r 20 = 0.402, p = 0.079). There was no correlation in the PTSD group.

Fig. 3. Group comparison for combat-related words. Veterans without post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) exhibited significantly stronger theta activity in the right ventral prefrontal cortex (PFC) during the 0.4–0.6 s time window relative to veterans with PTSD (p < 0.05, corrected). This group difference in the ventral PFC was sustained into the 0.6–0.8 s time window, and this latter window also included the right temporal cortices (not shown). All images are displayed by radiological convention (R = L) and have been thresholded at p < 0.05 (corrected). R, Right; L, left.

Within-group effects

Given our hypotheses, we were also interested in the neural dynamics serving EST performance in each group, which we examined through paired-samples t tests using the different words lists (e.g. combat-related threat v. neutral words) in each group.

General threat v. neutral words

Veterans without PTSD exhibited stronger left dorsolateral PFC theta activity during general threat words in the 0.2–0.4 s time window (p < 0.05, corrected), which spread to include areas of the left inferior frontal, superior and middle temporal, and the VPFC, as well as the right supramarginal gyrus during the 0.4–0.6 s time period (Fig. 4). Greater theta was sustained in the right supramarginal gyrus to the 0.6–0.8 s time bin in veterans without PTSD (p < 0.05, corrected; Fig. 4). In contrast, veterans with PTSD exhibited greater theta responses during the 0.6–0.8 s time window for general threat compared with neutral words in the left hippocampus and amygdala, along with the opposite pattern (neutral > general threat) in the left medial prefrontal cortices (Fig. 4). No other time period per group contained significant effects.

Fig. 4. Word list (conditional) effects in each group. Top panel: general threat compared with neutral words. During early processing (0.2–0.4 s), veterans without post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) exhibited significantly stronger theta activity in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortices (PFCs) during general threat compared with neutral words, and this activity spread to the left inferior frontal, superior temporal, and ventral PFC, as well as the right supramarginal gyrus later in the time course. In contrast, veterans with PTSD exhibited significant differences between general threat and neutral words during only the 0.6–0.8 s time window, and these differences reflected greater theta for the general threat words in the left hippocampus and amygdala, as well as less theta within the left medial PFC. Bottom left panel: combat-related threat compared with neutral words. Veterans without PTSD exhibited greater theta in left fronto-temporal cortices during combat-related words relative to neutral words in the 0.4–0.6 s time window. Slightly later, veterans without PTSD had significantly stronger theta activity in the right ventral PFC and medial temporal areas, including the amygdala, in response to combat-related words. Veterans with PTSD had significantly stronger theta activity during neutral relative to combat word processing in the parieto-occipital (0.4–0.6 s) and cingulate cortices (0.6–0.8 s). Bottom right panel: combat-related compared with general threat words. There were no significant differences between combat and general threat words in veterans without PTSD in any time window. In the 0.4–0.6 s time bin, theta activity was weaker for combat-related compared with general threat words in the right ventral PFC and medial temporal structures (hippocampus/amygdala), extending into more lateral temporal cortices, as well as the cingulate cortices. All images are displayed following radiological convention (R = L) and have been thresholded at p < 0.05 (corrected). R, Right; L, left.

Combat-related v. neutral words

Veterans without PTSD had stronger theta activity in the left inferior frontal cortices during combat-related relative to neutral word processing from 0.4 to 0.6 s (p < 0.05, corrected; Fig. 4), which dissipated thereafter. In the 0.6–0.8 s time period, theta was stronger for combat words in the RVPFC stretching into right medial temporal structures (hippocampus and amygdala; p < 0.05, corrected; Fig. 4). In veterans with PTSD, theta activity was greater for neutral compared with combat words in the parieto-occipital (0.4–0.6 s, Fig. 4) and cingulate cortices (0.6–0.8 s; p < 0.05; corrected; Fig. 4). No other time periods contained significant effects in either group.

Combat-related v. general threat words

There were no significant differences between these word types in any time bin for veterans without PTSD. In those with PTSD, stronger theta activity was observed for general threat words from 0.4 to 0.6 s in the cingulate and the RVPFC, extending into the right superior temporal gyrus and into right medial temporal structures (hippocampus/amygdala; p < 0.05, corrected; Fig. 4).

Discussion

Our overall pattern of results indicated that veterans with and without PTSD process and represent threatening stimuli differently. Specifically, our key results indicated reduced theta activity in the right PFC of veterans with PTSD compared with those without PTSD during the processing of combat-related words, but not other types of words. This finding suggests that veterans with PTSD have impaired attentional control during the processing of personally relevant emotional stimuli.

Our main findings supported the central hypotheses of the study regarding neural activity in veterans with PTSD during the EST. Specifically, veterans with PTSD exhibited activity within emotional processing medial temporal areas that persisted through the task, while also displaying lower levels of activation within attention and emotional regulation areas of the PFC, especially during combat-related words. This suggests an emotional representation bias for those with PTSD, originating from aberrant attentional processes or dampened emotional regulation. In addition, we observed the predicted pattern of activity for combat veterans without PTSD. Essentially, healthy veterans showed relatively high levels of sustained activation within prefrontal regions throughout stimuli processing in most conditions, and significantly stronger activity in the PFC relative to those with PTSD during combat-related words. Interestingly, these results support recent findings suggesting that individuals exposed to combat who do not develop PTSD display impressive frontal activity that may reflect emotional regulation in the face of threatening stimuli (e.g. New et al. Reference New, Fan, Murrough, Liu, Liebman, Guise, Tang and Charney2009; Blair et al. Reference Blair, Vythilingam, Crowe, McCaffrey, Ng, Wu, Scaramozza, Mondillo, Pine, Charney and Blair2013; White et al. Reference White, Costanzo, Blair and Roy2015).

Critically, the most important evidence supporting this model in the current study was revealed by group comparisons of combat-related word processing. Veterans without PTSD had greater theta activity in the RVPFC, which is often implicated in emotional regulation (e.g. Hariri et al. Reference Hariri, Mattay, Tessitore, Fera and Weinberger2003; Ochsner & Gross, Reference Ochsner and Gross2005; Heatherton & Wagner, Reference Heatherton and Wagner2011; Veit et al. Reference Veit, Singh, Sitaram, Caria, Rauss and Birbaumer2012; Buhle et al. Reference Buhle, Silvers, Wager, Lopez, Onyemekwu, Kober, Weber and Ochsner2014), as it mediates activity in the amygdalae and neighboring medial temporal structures, which are associated with emotional stimuli processing (e.g. LaBar & Cabeza, Reference LaBar and Cabeza2006; Kober et al. Reference Kober, Barrett, Joseph, Bliss-Moreau, Lindquist and Wager2008). Additionally, participants without PTSD displayed greater activation in the hippocampus and amygdala when processing combat-related as compared with neutral words, consistent with the personal relevance of these words. However, this elevated limbic activation was paired with increased RVPFC activation, suggesting that healthy veterans may engage prefrontal regions to down-regulate medial temporal activity, contributing to their healthy adaptation after combat trauma. Perhaps individuals able to recruit these emotional regulation areas develop the balance needed to suppress emotional biases and persevere in the face of trauma, as suggested by New et al. (Reference New, Fan, Murrough, Liu, Liebman, Guise, Tang and Charney2009).

On the other hand, our neurodynamic findings indicate that veterans with PTSD did not show effective prefrontal activation in the face of trauma-related words (across all list-by-list comparisons). In addition, these findings align with those of Thomas et al. (Reference Thomas, Gonsalvez and Johnstone2013) in their event-related potential examination of panic disorder patients who were unable to adequately recruit anterior regions during threatening stimuli processing. These neural findings are also consistent with our behavioral observations that veterans with PTSD displayed longer color-naming latencies for combat-related words compared with other words. Importantly, veterans with PTSD displayed relatively greater theta activity in attention allocation and emotion regulation areas such as the RVPFC, right superior temporal gyrus, and areas of the cingulate while processing generally threatening words as compared with combat-related words. Thus, veterans with combat-related PTSD may be limited in their engagement of attention allocation and emotional regulation areas in the face of combat-related threatening stimuli, but they can engage these executive areas in response to other types of threatening (generally negative) stimuli. This suggests that patients with PTSD may not necessarily have a global impediment in attention allocation, response inhibition and emotional regulation, but that their overall representation of personally threatening stimuli is dominated by the emotional salience of the stimuli, even when task demands should direct attention and representational activity to other features (e.g. ink color) of the stimuli.

These findings suggest both altered attention allocation and perseverance of threat processing in PTSD. Alterations in these mechanisms were suggested in a recent meta-analysis of behavioral EST effects in PTSD (Cisler et al. Reference Cisler, Wolitzky-Taylor, Adams, Babson, Badour and Willems2011) and by previous fMRI examinations of veterans with PTSD performing different, but similar, affective tasks (Pannu Hayes et al. Reference Pannu Hayes, Labar, Petty, McCarthy and Morey2009; Blair et al. Reference Blair, Vythilingam, Crowe, McCaffrey, Ng, Wu, Scaramozza, Mondillo, Pine, Charney and Blair2013; White et al. Reference White, Costanzo, Blair and Roy2015). However, our findings extend these data by providing the time course of neural activity in veterans with PTSD, and suggest both hypoactive attentional control and emotional regulation networks, and enhanced threat detection processing. Our results also support models suggested by White et al. (Reference White, Costanzo, Blair and Roy2015) and New et al. (Reference New, Fan, Murrough, Liu, Liebman, Guise, Tang and Charney2009) for combat-exposed veterans without PTSD, in that resilience may be partly attributable to the ability to recruit attentional control and emotional regulation areas even in the face of personally relevant threat.

Although our results are compelling, they should be interpreted with caution. First, a larger sample of veterans with and without PTSD would have been ideal. Second, although we equated our participant groups on education level and other demographic factors, directly measuring general intelligence would have enhanced the study. Future work should explore the degree to which personal relevance mediates the impediment in attention allocation and emotional regulation, perhaps by adding a word list personally selected by the participant as connected to their traumatic event. Future studies could also test whether computer-mediated attention training such as attention bias modification treatment, and/or attentional control treatment (e.g. Bar-Haim, Reference Bar-Haim2010; Schoorl et al. Reference Schoorl, Putman and Van der Does2013, Reference Schoorl, Putman, Van Der Werff and Van Der Does2014; Kuckertz et al. Reference Kuckertz, Amir, Boffa, Warren, Rindt, Norman, Ram, Ziajko, Webb-Murphy and McLay2014; Badura-Brack et al. Reference Badura-Brack, Naim, Ryan, Levy, Abend, Khanna, McDermott, Pine and Bar-Haim2015; McDermott et al. Reference McDermott, Badura-Brack, Becker, Ryan, Bar-Haim, Pine, Khanna, Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson2016b ) normalizes these observed neural aberrations associated with PTSD. Recent behavioral findings on a subset of this PTSD group who completed attention training treatment and then a second EST, found symptom suppression and color-naming performance indistinguishable from veterans without PTSD (Khanna et al. Reference Khanna, Badura-Brack, McDermott, Shepherd, Heinrichs-Graham, Pine, Bar-Haim and Wilson2016); however, it remains unknown if these behavioral changes were linked with modulations in threat detection (e.g. medial temporal) and/or emotional regulation (e.g. ventral PFC) networks. Finally, this work could be improved by a prospective study examining the attention allocation patterns of those who experience a new traumatic event but do not develop PTSD. Perhaps some individuals are resilient to PTSD because they have a superior ability to engage emotion regulation areas in the face of threat, or perhaps some are better able to quickly adapt once traumatic events occur such that when faced with threat, they are able to direct stimuli representations away from emotional dimensions.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the non-profit organization At Ease, USA (A.S.B.-B.), by a Creighton University College of Arts and Science Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (T.J.M.), the Kinman-Oldfield Award from the University of Nebraska Foundation (T.W.W.), grant no. R01-MH103220 from the National Institutes of Health (T.W.W.), and award no. 1539067 from the National Science Foundation (T.W.W.). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of Interest

None.