These are just a few lines of the 46-page dialogue of Bikram yoga, a form of hot postural hatha yoga and the context of an empirical, ethnographic study I carried out in a Bikram yoga studio in Oslo, Norway, from 2018 to 2020. Although the Bikram script is referred to as a “dialogue,” it is more of a monologue, as students are not allowed to speak in class and respond with “the most basic mechanism of embodied agency” (Bucholtz and Hall Reference Bucholtz2016, 184) such as eye gaze, gesture, and bodily movements without talk to perform a particular social action, that is, elicit assistance from an instructor. The linguistic, embodied, and thus also performative style of this dialogue and social practice no doubt unsettle embodied discourse and social and cultural ideologies of this activity and perhaps even the particular kinds of people who engage in it, since it is often described as “military” and “stringent,” consisting of quick directives primarily by means of orders and commands requiring practitioners’ undivided attention. While all types of yoga work on a physical and discursive level since the body is considered both discursive and material, Hauser (Reference Hauser2013) argued that the style and practice of Bikram in particular challenges socially learned cultural attitudes toward personal limits and pain that she found in her study of speech patterns. In line with the themes of this special issue, I analyze the semiotic links between embodied, linguistic, and nonlinguistic signs found in a Bikram yoga studio in Oslo and on its website, which are informed by other hegemonic sites of yoga circulation on a more global level, which include the Bikram franchise and Lululemon. I draw on the analytical concepts of both enregisterment (Agha Reference Agha2007) and mediatization (Agha Reference Agha2011) in my analysis of these three institutional sites to explore the relation between linguistic and nonlinguistic signs in enregisterment processes of Bikram yoga through the analysis of multimodal images both offline and online, where mediated messages of flexible, embodied, and highly commodified practices that are culturally and socially valued and dialectally embedded in bodily, material, and technological environments. As such, this study responds to Pennycook’s (Reference Pennycook2018a, Reference Pennycook2018b) work on posthumanism, which asks us to question the boundaries between what is seen as inside and outside, where thought occurs, and what role a supposedly exterior world may play in thought and language.

The analysis of enregistered and mediated processes of embodied practices and their circulation in both online and offline spaces and places resonates with posthumanism theory in that it considers the “relevance of materialism, an insistence on embodiment, and reassessment of the significance of place” (Pennycook Reference Pennycook2018a, 449). As such, this study aims to contribute to integrational approaches to linguistics (Toolan Reference Toolan1996; Harris Reference Harris1998) as an “alternative conceptual framework for linguistic inquiry” (Harris Reference Harris1998, 4) and posthumanists’ theoretical agenda to “broaden an understanding of communication to relocate where social semiotics occurs” (Pennycook Reference Pennycook2018a, 446). With this in mind, it asks the following research questions:

What is the relation between linguistic and nonlinguistic signs in enregisterment processes of Bikram yoga through the analysis of multimodal images in both online and offline space?

What semiotic activities contribute to the enregisterment of a successful Bikram yoga persona on a local level that are ideologically influenced and informed by mediatized practices and other hegemonic sites of yoga circulation such as Lululemon?

Following an introduction to yoga in general and Bikram yoga in particular, I discuss the setting of my study, my methodological approach, and the theoretical framework used. Afterward, I present examples from my findings and analysis with the aim of contributing to posthumanist theorization through an informed semiotic analysis of Bikram yoga’s enregisterment and mediatization in Norway, while also exemplifying internal contradictions in the metadiscourses promoted by both the Lululemon brand and the Bikram script.

Yoga and the Commodification of “Self-Care”

The practice of yoga, a trifecta of physical, mental, and spiritual disciplines involving specific movements has its origins in ancient India. Over the last 150 years it has been shaped and highly influenced by European and American body cultures and sports like bodybuilding and women’s gymnastics (Hauser 2013; Schnäbele Reference Schnäbele2013). Contemporary posture-based yoga resulted from a new emphasis on physical culture in the twentieth century, which became both popularized and also appropriated in the West (Bailey et al. Reference Bailey2022). This happened when major political-economic transformations were taking place, such as the shift to post-Fordist forms of work and production, where discourses of flexibilization, competition, and fragmentation of employment relations emerged, resulting in individuals’ constant need to adjust to changing work and therefore also life conditions (Schnäbele Reference Schnäbele2013). This is perhaps not surprising considering the advent of neoliberalism in the late 1970s, which constitutes cultural and economic ideology with an emphasis on free markets, economic deregulation, privatization, and individualism (see Rosen [Reference Rosen2019] for a discussion of yoga, neoliberalism, and second-wave feminism in the United States).

Within contemporary Western societies, individuals are increasingly expected to be both self-reliant and self-disciplining. Dominant discourses emphasize rights—defined in a very individualized way, where choice becomes inevitably equated with freedom. Given the existing connections between neoliberalism and capitalism, individuals are encouraged to enact this freedom through their participation first and foremost in the market economy. Citizenship is therefore no longer understood as participation in a collective sphere, but rather individually (Laverence and Lozanski Reference Laverence2014). For Guthman and DuPuis (Reference Guthman2006, 443), “the citizen consumer whose contribution to society is mainly to purchase the products of global capitalism” and remain flexible. This connects to the writing of feminist anthropologist Emily Martin (Reference Martin1994), whose work theorizes how models of the body reflect models of society within American culture, where ideologies of health and immunity strongly influenced the way individuals worked as well as the values they had regarding physical well-being, one of which was flexibility (Bailey et al. Reference Bailey2022). This resonates with the neoliberal project, where the refinement and enhancement of the self was key, determined through self-discipline and constantly being pursued by means of acquiring skills, such as physical strength, ability, and flexibility both at work and beyond.

By the turn of the century, yoga had become commercialized, and today it is considered to be a mainstream activity embedded within popular culture, exemplifying processes of commodification and material production, on the one hand, while emitting how (Western) ideologies of health, fitness, beauty, and bodies are represented, packaged, and circulated for reasons of cultural consumption and, ultimately, economic profit. For Antony (Reference Antony2018, 5), yoga is considered an appropriated and reappropriated indigenous cultural artifact that has been resignified by mainstream media for contemporary global audiences through symbolic rearticulation within processes of commodification, mass consumerism, and social values within a neoliberal context. In fact, Antony found that yoga’s resignification and reappropriation not only complements but also sustains neoliberalist frameworks, individualism, and personal accomplishment resonating with Bailey et al.’s (2021, 3) claim of how yoga has become a flexible biopedagogical practice shaped, in part, by gendered, raced, abled, and neoliberal ideologies and systems. Indeed, shifts to what Foucault (Reference Foucault1998) has termed “the technologies of the self” rather than within the technologies of the government place particular emphasis on individuals’ management of their lives, including their health, via means of self-care, self investment, and self-optimization (Rose Reference Rose2007). For Rosen (Reference Rosen2019, 296), “yoga plays an important role in this ensemble of activities, as a commoditized ‘technique of the self’ (Godreij Reference Godrej2017) primarily disseminated to an audience of middle-class white women in the United States.” But this dissemination extends well beyond the United States to other Western nations, including Norway, as well as online commercial spaces, where discourses of self-care and flexibility are framed through the consumption of yoga within an imaged global community of practice where mediatized representations of authentic yoga personas are engaged in mediated embodied practices that are circulated and instantly distributed. For Giroux (Reference Giroux2004), the spaces in which digital information operates may be regarded as sites of “public pedagogy,” where the learning and teaching of particular embodied practices and social behaviors regarding gendered bodies, health, and capabilities are showcased (Bailey et al. Reference Bailey2022, 7). For these authors, such practices are “indicative of how power operates in neoliberal, turbo-capitalist, post-feminist political economies that conflate freedom with having the income needed to choose from a range of commodities (e.g., products and practices to achieve a desired body)” (6–7). Indeed, by placing value on and consuming yoga as a practice that is often circulated under the metalinguistic label “self-care” (Michaeli Reference Michaeli2017; Rosen Reference Rosen2019, 296), individuals ultimately enact the metadiscourse of flexibilization and neoliberalism by having both the time and socioeconomic privilege to invest in yoga and in themselves. As will be shown, offline and online images of flexible and capable bodies are also coded as economically privileged, beautiful, and worthy.

There is no denying that yoga has been and continues to be both commodified and framed in the name of spirituality, lifestyle, flexibility, and health. In fact, yoga is part of the growing and very lucrative global health care industry, which in 2015 had a market value of US$87 billion and a revenue of US$9 billion, which was expected to increase along with the number of its practitioners by 2020 (Bhalla et al. Reference Bhalla2022).

While yoga is recommended for individuals with various symptoms and diseases associated with the modern lifestyle, including stress, depression, sleep disorder, muscle tension, migraine, obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, and back and neck pain (Hauser 2013, 111), it has not escaped negative commentary from social critics and twenty-first-century bloggers, who have mocked it as a form of “post-secular spirituality” and even a cliché (Hauser 2013). In fact, it has been included in Lander’s (Reference Lander2011) best-seller titled Stuff White People Like: the Definitive Guide to the Unique Taste of Millions—a satire aimed at the interests of North American left-leaning, city-dwelling White people, where in addition to coffee, multilingual children, and Noam Chomsky, yoga is also listed (see Jaffe [Reference Jaffe2016] for a thorough analysis). Most recently, the cultural politics of yoga, also known as “yoga wars,” taking place between North America (especially the United States) and India, have been investigated by scholars with regard to the controversy of cultural appropriation, which draws on questions of (neo)colonialism, capitalism, and racism (Kale and Novetzke Reference Kale2021). According to Schnäbele (Reference Schnäbele2013), contemporary yoga is practiced mainly by the middle class in urban areas of Europe, North America, and Australia, if not worldwide. In the United States, both Parks et al. (Reference Parks2015) and Rosen (Reference Rosen2019) found that yoga’s demographics are female, educated, middle-aged, and White, resonating with popular media representations of the practice,Footnote 1 which have “largely emphasized thin, white female practitioners donning expensive apparel and accessories, exemplifying many aspects of a commercialized and objectified fitness culture” (Bhalla et al. Reference Bhalla2022, 6).

Bikram Yoga: “A Demanding Form of Yoga”

Bikram yoga, “a demanding form of yoga” (Hauser 2013, 109) was invented by Bikram Choudry, a Bengali Indian who migrated to the United States in the 1970s. Unlike other forms of hatha yoga, Bikram is a set sequence of 26 postures comprised of 24 asanas and two pranayama breathing exercises that is fixed and does not allow for variation. In fact, in 1994, the Bikram sequence was copyrighted (Hauser 2013, 115) allowing Choudry to tap into and capitalize on this form of yoga on a global scale. For Bikram practitioners, this means that regardless of one’s physical place and the language used for instructive purposes, the embodied sequence takes precedence. There are several characteristics of Bikram that differentiate it from other forms of hatha yoga. For example, Bikram classes are conducted over a 90-minute period in a room heated to 40 degrees Celsius, with 40 percent humidity, to ensure the release of “toxins” and individuals’ ability to stretch deeper with the aim of avoiding injury. Bikram also relies primarily on verbal instruction from teachers, and while there is considerable variation in terms of gesture use among teachers, teachers do not simultaneously practice and teach. As such, instructors do not serve as embodied examples for students to follow. Rare exceptions to this rule are when “silent courses” are offered, when the only word uttered by the instructor is “change,” informing practitioners when to begin and end a posture. Due to the lack of embodied instruction, Bikram yoga rooms are equipped with floor-to-ceiling mirrors so that students can constantly check their alignment and posture (see fig. 1). Another difference is that there is just one type of Bikram class offered to students regardless of individuals’ level. While this may at first appear to index inclusivity and diversity, status differences become apparent and are also visually manifested in a hierarchical order, with more experienced and advanced practitioners (who also happen to be wearing less clothing) located in the front and intermediate and beginners located toward the back, as can be shown in figure 1. The objective of this hierarchy is for beginners to look and learn from more experienced students, as can be seen in figure 1.

Figure 1. Bikram yoga room and the visual hierarchy

At the time of my fieldwork in 2018, there were over 600 studios worldwide (Hewett et al. Reference Hewett2015); however, in recent years, Bikram has come under considerable scrutiny due to allegations of sexual assault and discrimination from former students. As such, many studios have changed their names and studio branding.Footnote 2 The rise and fall of Bikram can be observed in a recent documentary titled Bikram: Yogi, Guru, Predator, which was released in 2019 on Netflix.

Embodied Ethnography at Bikram Yoga Oslo: The Site of Study

Bikram Yoga Oslo (BYO) is located in central Oslo (an elite neighborhood), just a five-minute walk from the royal palace. BYO was established in 2011 by an Indian Australian migrant to Norway. At the time of my data collection in 2018–20, the studio had 4,000 students (including drop-ins) and 7 teachers, including 1–2 traveling staff. My interest in this studio as a research site had to do with the mobile and international staff, languages, and gestures used in class, teaching, and spatial style, as well as the consumption of material and thus embodied culture of the practice. Similar to other researchers who have investigated sports within sociolinguistics (Madsen Reference Madsen2015), my preresearch knowledge of Bikram as a long-time practitioner and certified hot yoga instructor was a major impetus for carrying out this ethnographic study. Drawing on ethnography was crucial as it allows for a rich and deep understanding of local semiotics, where the sociocultural meaning of embodiment can be recognized and “thick description” made (Geertz Reference Geertz1977). For this study, I collected diverse data sets consisting of spoken, written, and visual data over a two-year period from 2018 to 2020, as listed in table 1. I began my Bikram practice at BYO in 2017 and had been engaged in a regular practice there for an entire year before beginning my research. The reasons for this had to do primarily with gaining trust from prospective participants, many of whom were part-time instructors at BYO. It was only after being personally invited by an instructor to participate in a “private advanced class” that was not officially advertised that I asked permission from BYO’s owner to carry out my project, which she granted.Footnote 3 As such, “long-term and open-ended commitment, generous attentiveness, relational depth, and sensitivity to context” could be “properly” and “rigourously” guaranteed (Ingold Reference Ingold2014, 384).

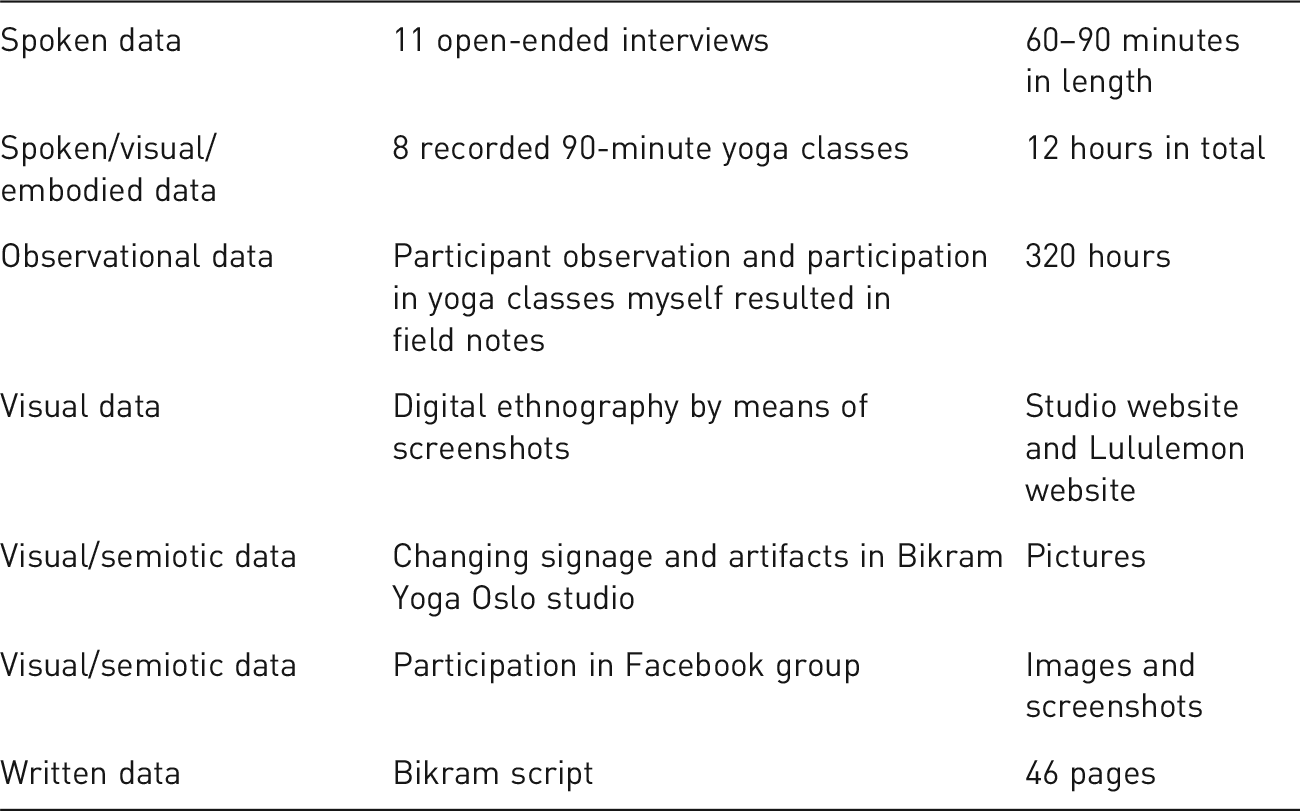

Table 1. Diverse Data Sets

Embodied Sociocultural Linguistics and Posthumanist Theorization of Communication

Studies focusing on communication and the body are not new in research on language and social interaction (Streek et al. Reference Streeck2011; Nevile Reference Nevile2015), gesture studies (McNeil Reference McNeill1981, Reference McNeill2005; Kendon Reference Kendon1990, Reference Kendon2004; Gullberg Reference Gullberg1998, Reference Gullberg2011); interactional sociolinguistics (Keevalik Reference Keevallik2010, Reference Keevallik2013; Mondada Reference Mondada2014, Reference Mondada2016, Reference Mondada2019; Canagarajah and Minokova Reference Canagarajah2022) or social semiotics (Murray Reference Murray2005; Beilharz Reference Beilharz2011; McDonald Reference McDonald2013). They have nevertheless received a renewed interest within the field of sociolinguistics prompted by the call from Bucholtz and Hall (Reference Bucholtz2016). According to these authors, “embodiment is enlisted in a variety of semiotic practices that endow linguistic communication with meaning ranging from the indexicalities of bodily adornment to gesture, gaze, and other forms of movement. And just as bodies produce language, language also produces bodies” (Reference Bucholtz2016, 173). Scholars have analyzed the body from different theoretical perspectives, including performativity (Goffman Reference Goffman1959; Butler Reference Butler1990, Reference Butler1993), sexuality, “bio-politics,” “anatomo-politics” (Foucault Reference Foucault1977; Reference Foucault1984), social class (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1984), and feminism (Douglas Reference Douglas2017). Questions surrounding the human body and humans in general have also been posed by scholars of posthumanism aiming to find out why we think about humans in specific ways, “with particular boundaries between humans and other animals, humans and artefacts, humans and nature” (Pennycook Reference Pennycook2018a, 445). For Barad (Reference Barad2007, 136), posthumanism “doesn’t presume the separateness of any-‘thing,’ let alone the alleged spatial, ontological, and epistemological distinction that sets humans apart.” In these ways, scholars of posthumanism are interested in undoing binaries of the self/other and identity and intersubjectivity “by attending to sensorial, affective, placed-based, political forces” (Toohey et al. Reference Toohey2020, 3).

For Pennycook (Reference Pennycook2018a), drawing on posthumanism has implications for the ways in which we understand language in relation to people, objects, and place. Spaces, both physical and virtual, are also material and an integral part of how communication and social arrangements are negotiated and, in the case of online spaces, also rapidly disseminated. In his work on posthumanism and world Englishes, Wee (Reference Wee2021, 7) maintains that in addition to language resources “media technologies disseminate popular culture which is no longer being done via physical interactions between people, but through textually mediated encounters.” In many ways, this resonates with Pennycook’s notion of spatial repertoires of offline contexts that are not that different from virtual spatial repertoires despite online activities dispersion of specific resources (Reference Pennycook2018a, 452).

Enregisterment and Mediatization in Three Institutional Sites

In order to present an informed semiotic analysis of Bikram yoga’s mediatization at BYO, I draw on Agha’s notions of enregisterment (2005) and mediatization (2011). I do this by exploring the relation between linguistic and nonlinguistic signs within processes of enregisterment (Agha Reference Agha2007) in indexing social meaning and the performance of Bikram yoga practitioners. Enregisterment is the process whereby distinct forms of speech come to be socially recognized as indexical of speaker attributes by a population of language users. It will be shown that the linguistic repertoire found within the Bikram yoga script as well as Lululemon’s branding inform the ways in which Bikram practitioners speak about their practice as a socially recognized register that indexes speaker status and cultural values within the Bikram community on a local level that resonates with Bikram yoga practitioners on institutional and more global scales. Indeed, the ways in which such processes occur are through different means of mediatization and institutional sites of yoga circulation. According to Agha (Reference Agha2011, 163):

To speak of mediatization is to speak of institutional practices that reflexively link processes of communication to processes of commoditization. Today, familiar institutions in any large- scale society (e.g., schooling, the law, electoral politics, the mass media) all presuppose a variety of mediatized practices as conditions on their possibility. In linking communication to commoditization, mediatized institutions link communicative roles to positions within a socioeconomic division of labor, thereby expanding the effective scale of production and dissemination of messages across a population, and thus the scale at which persons can orient to common presuppositions in acts of communication with each other. And since mediatization is a narrow special case of mediation, such links also expand the scale at which differentiated forms of uptake and response to common messages can occur, and thus, through the proliferation of uptake formulations, increase the felt complexity of so-called “complex society” for those who belong to it.

From this quote, several points arise that assist us in our understanding of how communication functions in terms of its emission, how it is received (uptake), and how it is circulated at different scales. In our contemporary globalized world, most institutions are involved in heavily mediatized practices where a range of commodities—in this study, yoga products and yoga experiences, with the aim of achieving a certain kind of body—are imbued with specific values and available for consumption. A major and powerful institutional site that disseminates a specific (Bikram) yoga register is Lululemon.

Lululemon is a Canadian athletic apparel brand that generated roughly US$3.98 billion in net revenue worldwide in 2019 (Tighe Reference Tighe2022). Although the company originally sold only women’s yoga apparel, it has expanded to include gear for running, cycling, and other athletic activities. By 2024, it is estimated that there will be approximately 600 Lululemon stores worldwide, indicating the increased consumption of material culture on a global scale (Schwab Equity Ratings 2023). Given its global reach within the yoga industry as well as its local significance within BYO, I would argue that Lululemon is a prime site of metacommunication, where communicative resources are used to talk, discuss, write about, promote, and also visually represent other forms of communication. These include material objects in the form of yoga apparel and embodied practices in the form of yoga postures, all of which are heavily mediatized and specifically branded for women on a global scale that informs particular practices within BYO on a local level. Lululemon is therefore highly involved in the value production of yoga as an embodied material practice, which when consumed may contribute to the enregisterment of the successful Bikram yoga persona. The ideological messages of (Bikram) yoga and its practitioners, which are mediated on Lululemon’s website, trickle down into the physical spaces of the BYO studio. This is where recontextualization processes concerning symbolic and material values exemplifying how a local yoga studio becomes a place where layered communicative and multimodal resources are used and exchanged for a range of commodities may prosper.

Within this study, three main institutional sites emerge as relevant, namely, Bikram yoga, Lululemon, and the BYO studio. It is within the space of the BYO studio that the promotion, dissemination, circulation, and commodification of a specific kind of yoga practice is taken up and repeated with practitioners and students in complex ways and through various degrees of semiosis on a local scale that are ideologically influenced and informed by mediatized practices on a more global scale. In these ways and for the purpose of my analysis, this includes investigating the institutionalized roles of all three sites, the mediated messages of a specific embodied practice identified as “Bikram,” the Bikram yoga register, and, ultimately, the transformation of social meaning through communicative and semiotic processes within different social and mediatized spaces (both online and offline). In other words, how the semiosis of a Bikram yoga studio is linked to and simultaneously informed by other (hegemonic) sites of yoga circulation, namely, Lululemon, will be investigated.

Analyzing Script and the Register of Bikram Yoga

The language used within the Bikram script has been carefully chosen and is also ideologically loaded. Unlike other styles of yoga, Bikram invites practitioners to go beyond their limits and embrace sensations of acute discomfort, nausea, dizziness, and even pain (Hauser 2013). An example of this comes directly from the Bikram script in its description of the pada hastasana (hands to feet) pose. The script reads:

According to Kaminoff and Matthews (Reference Kaminoff[2007] 2012, 80–81) this pose is classified as a symmetrical standing forward-bending pose where skeletal joint actions take place in the spine (mild flexion) and lower limbs (hip flexion and knee extension) where concentric and eccentric contraction occurs while passively lengthening various muscles, including hamstrings, gluteus maximus, soleus, and others. The authors caution practitioners that “if hamstrings are tight, slightly bending the knees helps release the spine” (81). These cautionary instructions are very different from “the pain sensation” Bikram practitioners should aim for. In fact, the feelings of pain within this posture should result in greater physical benefits such as spine release and lengthening and overall flexibility. Such “pain sensation” resonates well with the 1980s English proverb “No pain, no gain” as an exercise motto that promises greater value rewards for the price of hard physical work. Individuals’ ability to endure and voice pain on both a physical and mental level indexed ambivalent feelings of exhaustion, happiness, and cleansing, processes that appeared to be highly valued among practitioners and therefore also enregistered by them.

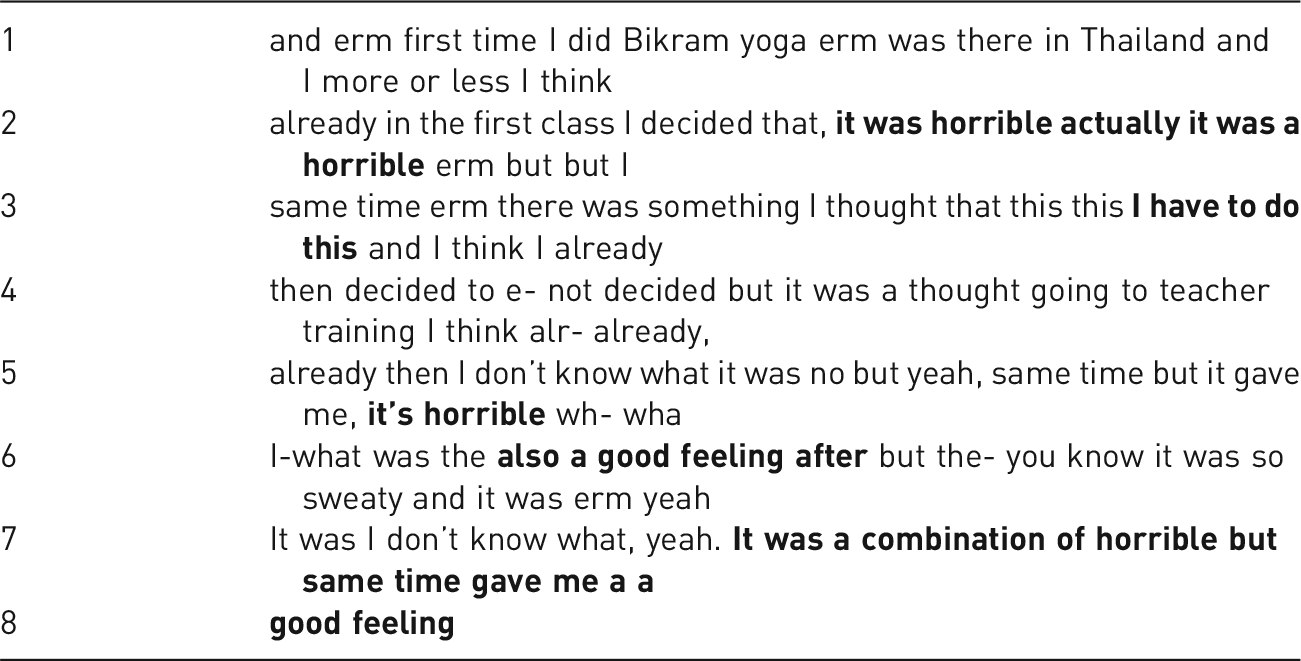

In my interviews with participants, the distinct forms of speech that came to be socially recognized were those of both pleasure and pain that were often talked about simultaneously, as in the following example of Martin, a yoga instructor, who described his first experience of a Bikram class in 2011.

The contradictory embodied feelings of both pleasure and pain (lines 2, 6, 7–8) that Martin experienced during his first class eventually led him to complete the teacher training, which he later describes “like a boot camp yeah it’s, it’s, a it’s taken to the taking you to the limit.” Speaking of Bikram teacher training as a “boot camp” denotes stringent military-like experiences of immense suffering while at the same time being a sign of social class distinction and exclusivity, since not all teachers complete the training nor is this training available to everyone due to its high costs, approximately US$12,000 dollars for a two-month course located in Los Angeles. Martin was not the only practitioner who discussed the mixed embodied sensation of this practice, but it appeared to be part of the register of local Bikram yoga practitioners and an example of what has been referred to in sociolinguistic studies as indexical iconization, influenced by the work of Eckert (Reference Eckert1990) in her seminal study of jocks and burnouts. According to Bucholtz and Hall (Reference Bucholtz2016, 180), indexical iconization means that in order for individuals “to make semiotic sense of themselves and others, individuals link specific ways of being in the world to ideological expectations regarding specific ways of speaking.” For the practitioners I spoke with conquering the agony of Bikram seemed to legitimize their authentic yogi identities in this local community of practice while resonating with Bikram practitioners globally that were also informed by mediated messages on Lululemon’s website and its Fringe Fighter Headband in figure 2.

Figure 2. Lululemon’s Fringe Fighter Headband

With the Fringe Fighter Headband, we have an example of Lululemon as an institutional site disseminating and circulating a yoga register that resonates with the Bikram script and practice, including mixed body sensations of pain, struggle, and success, where the saliency of the visual, linguistic, and material come to the fore, indexing social meaning and the performance of an authentic and serious yoga practitioner. The message incorporated within this mediatized exchange is also involved in an imaginary commercial exchange between Lululemon and their prospective consumers (primarily privileged White women) and where the purchase and consumption of the mediatized object (the headband) takes on a relevant and even altering role within one’s practice by potentially enhancing it. The use of fringe fighter to depict a headband could be interpreted as combating someone’s fringe so they can focus first and foremost on their practice but contributes to a yogi’s style production by means of bodily adornment and self-presentation that center on aspects of color and materiality. By attributing human characteristics to something nonhuman like a headband exemplifies how the linguistic and the material interact. It also exemplifies how the “semiotics of style includes all dimensions of language as well as material and embodied resources of self-presentation, which together yield ideologically cohesive semiotic packages available for interpretation by others” (Bucholtz and Hall Reference Bucholtz2016, 180). It appears therefore that the fringe fighter is not your average headband but rather is produced with Luon fabric, described on the website as “seriously light.” Within the context of Bikram, headbands became a metasemiotic index capturing Silverstein’s (Reference Silverstein2003) principle of the double arrow of indexicality, where every sign is understood to presuppose something and entail something when it is used. Within the studio, headbands indexed physical ability, personal style, but, from my experience, also seriousness. The stylistic and semiotic practice of physically sporting a headband to index seriousness and talking about one’s practice through means of pleasure and pain contribute to the enregisterment of the successful Bikram yoga persona as a distinguished form of advanced and perhaps even superior yoga practitioner. In these ways, the semiotic processes of enregisterment demonstrates that linguistic features make up only a part of larger sets of nonlinguistic signs that index how semiosis unfolds and produces recognizable social types (Telep Reference Telep2021, 235). The Luon fabric, in addition to being sweat-wicking and supportive, is also known for its material flexibility. Physical flexibility is also a characteristic or sign quality highlighted on BYO’s website, which emerges as both a sign-token and metasign that organizes a range of object signs across different institutional sites, including Lululemon’s and BYO’s websites, as well as in BYO’s physical studio.

Enregisterment of Bikram Yoga through Embodied and Nonlinguistic Signs

In “Meet Our Team” (fig. 3), we are introduced to three teachers at BYO via its website. The background is white with bits of green plants, and it is not exactly clear where these people are. This setting may be considered somewhat “decontextualized,” but according to Ledin and Machin (Reference Ledin2018), a greater symbolic role is played here with these individuals in order to symbolize an idea or concept such as natural, minimalist, and diverse in terms of race, gender, and flexible body shapes. While race and gender are examples of metasigns, physical flexibility also emerges as an important metasign regardless of one’s gender. Although metasigns are not always linked to verbal production, the visual representation of physical flexibility depicted by Susanne and Martin on BYO’s website surface as relevant nonlinguistic signs that are historically informed by political economic policies, which laid the ground for contemporary neoliberal discourses of the consistently improved self as a flexible individual. Such mediated messages are taken up and valued not only in the local Bikram studio but also globally (Bailey et al. [2021]; see Rosen [Reference Rosen2019] for a discussion in a US context).

Figure 3. Meet Our Team

Resh, the owner of BYO and a teacher, is perhaps not the stereotypical figure of an avid Bikram yoga practitioner, which has largely been in line with culturally dominant but slowly changing discourses of the body as strong and lean (Bhalla and Moscowitz Reference Bhalla2020). There is evidence of this in diverse academic fields that investigate the politics of embodiment with regard to bodily differences on the basis of various factors, including gender assignment, racial categorization, physical normativity, or physical acceptability (Kleese Reference Kleese2007; Hall et al. Reference Hall2019). In figure 4, we see how the presentation of physical diversity on BYO’s website is also informed by mediated representations of yoga practitioners from Lululemon’s website, where globally circulated metasigns of racial categorization and diversity in terms of body sizes have recently been included into their online advertising campaigns.

Figure 4. Recent advertisement of Lululemon apparel with an array of racial categorization and body size

These images are in line with contemporary changes in the media that focus on an appreciation of the so-called real female body as unmodified, which has been both informed and critiqued by postfeminist discourse (Tsaousi Reference Tsaousi2017).Footnote 4

A closer look at figure 3 gives us further insight into the visual categorization of advanced practitioners and their bodies (especially when analyzing Susanne and Martin), which are also heavily informed by prefigured, mediatized representations from hegemonic institutions like Lululemon as well as their in situ practices within the actual BYO studio. With Susanne and Martin, we find a minimum of sportswear is used, possibly due to the heat, humidity, and sweating. I would argue, however, that it has to do with body shape, body size, individual, social, and advertising style, raising issues of the politics of embodiment and pointing to a further instance of nonlinguistic enregisterment and the ways in which this is circulated and taken up. As such, it appears that minimal clothing is determined not only in terms of who can wear what in a Bikram class but who wears what in a Bikram class. These decisions may be based on physical distinctions, such as bodily differences and even racial categorization (Resh, the Indian Australian, is fully clothed), but also on biological categorizations, including toned arms, legs, and stomachs, which are themselves determined largely by ideologies of aesthetics, health, physical ability, and the seriousness of practitioners. Such mediated and in situ nonlinguistic signs and examples of enregisterment are widely circulated on Lululemon’s website and are also found within the physical studio of BYO (fig. 5). In figure 5, we encounter two barely clothed practitioners performing the inverted vertical position of a handstand with bent knees. Within yoga, the handstand pose (adho mukha vrksana) is considered one of the most difficult and advanced postures requiring strength, flexibility, and awareness of the body and one’s breadth. By encountering these large images upon the studio’s entrance, individuals are confronted with imagined ways of both enacting and embodying this practice, where flexible and capable bodies are highly valued and may be coded as worthy, beautiful, strong, and even economically privileged (Bailey et al. Reference Bailey2022), especially if they are paired with Lululemon apparel, which is also conveniently displayed at the studio’s entrance on the right-hand side.

Figure 5. Entrance of BYO with images of strong, flexible, and half-dressed bodies and Lululemon yoga apparel for sale

In each posture of Bikram individuals are forced to stretch, squeeze, compress, twist, bend, and release. Such embodied acts are also found on Lululemon’s website where the combination of tanned and toned bodies with minimal to no clothing indexes physical ability, as seen with Martin and Susanne on BYO’s website (fig. 3) and the studio’s entrance (fig. 5). At the same time, the minimal clothing also parallels the marginal written language used to convey social meaning, as seen in figure 6.

Figure 6. Lululemon advertisement of tanned and toned yoga bodies with minimal language and minimal clothing

In figure 6, we encounter two mediated and highly stylized representations of different yoga postures where the use of minimal clothing becomes another example of nonlinguistic enregisterment of the successful yoga persona. According to Ledin and Machin (Reference Ledin2018), the use of unmodulated color of the skin creates a perspective of cleanliness, naturalness, health, and certainty, all of which are relevant to contemporary consumerism and capital accumulation. The words “hugged and held in” found within circles next to these postures hone the viewer into a complex semiotic assemblage shaped by textual, physical, and a corporeal regime of signs following Deleuze and Guattari (Reference Deleuze1987), where language is embodied, embedded, and in this case, also enacted and performed. How yoga bodies are represented online are connected to a number of design choices, hegemonic ideologies of idealized aesthetics and flexibility, as well as indexing codes of ability, beauty, health, and economic privilege. In this example, wearing expensive form-fitting yoga apparel to visually reveal muscle tone and length also serve to signal socioeconomic advantages (e.g., Vinoski Thomas et al. Reference Vinoski2017; Strings et al. Reference Strings2019; Bailey et al. Reference Bailey2022, 8) of fit White female yoga practitioners (and possibly those aspiring to be labeled as such).

As spaces of “public pedagogy” (Giroux Reference Giroux2004), institutional sites like Lululemon’s website and the commodified practices of yoga representation become digital realms where individuals learn from one another in terms of the ways of enacting and also embodying the yoga persona, which socially condition the way such practices (and commodities) are further circulated, taken up, and consumed. As previously stated, Lululemon has been very successful and currently dominates the contemporary yoga apparel industry globally.

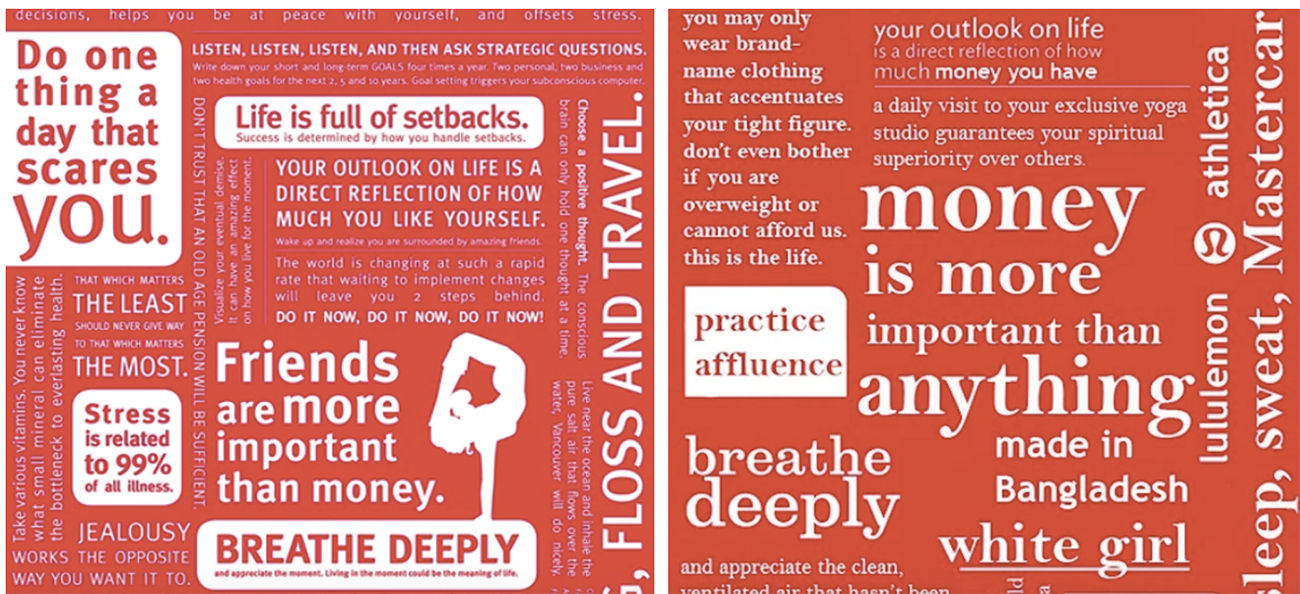

Semiotic Displays of a Characterological Figure: The Case of Lululemon’s Bags

In their study of Lululemon branding strategies via its “manifesto,” Laverence and Lozanski (Reference Laverence2014, 77) claim that the company “appropriates yogic practice into a consumerist model of discipline and self-care linked with neoliberal hyperindividualism and broader self-help discourses that define health and wellness as a personal and moral achievement” on individual, community, and societal levels. Interestingly, the company’s corporate and philosophical vision are printed as one-liners on their reusable bags indexing contemporary environmental and ecological concerns of sustainability while simultaneously exemplifying the ways in which their brand identity is linguistically and materially indexed “through appeals to self-betterment” (77) by means of bodily adornment and physically sporting such a bag. In fact, these one-liners are often found in the forms of imperative clauses associated with directives, commands, orders, and instructions such as “Breathe deeply,” “Do one thing a day that scares you,” “Listen, listen, listen,” and “Do it now, do it now, do it now,” as seen in figure 7.

Figure 7. Lululemon manifesto printed as one-liners on their reusable bags and class in sports “cultural jam” (2015)

Similar to the actual Bikram script, which consists largely of grammatical parallelism in the form of repeated directives, the embodied and verbal repetition of this practice in class as well as the linguistic repetition on these reusable bags function to reinforce certain sociocultural values and validate specific ideologies of yoga practitioners. One could argue that the socially reified conceptualizations of yoga practitioners are in fact the primary source of the meanings attributed to the activities (Esposito and Gratton Reference Esposito2020, 7). In the words of Agha (Reference Agha2007, 177), these could be a characterological figure and thus “an image of personhood that is performable through a semiotic display or enactment.” This manifesto found on Lululemon’s bags has been criticized and displayed as a cultural jam by “class in sports,” which has altered the printed messages to reflect the image and classism Lululemon actually portrays, as seen in figure 7.

In figure 7, the messages that reflect Lululemon’s image are one of exclusivity based on social class distinctions, race, gender, body size, and “people who have access to organic food.” Sporting Lululemon gear and/or carrying around one of its reusable bags is no doubt a semiotic display of a characterological figure (Agha Reference Agha2011) as well as a sign of social distinction following Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1984) and perhaps even a sign of “conspicuous consumption,” in Veblen’s words (Reference Veblen1899), which exhibits an important internal contradiction in the actual metadiscourses endorsed by the Lululemon brand itself. While simultaneously promoting sustainability and flexibility, Lululemon also participates in a highly exclusionary political economy of consumption. Moreover, the yoga images that Lululemon presents online promote feelings of softness and intimacy, while the actual Bikram script and practice is considered “military” and stringent, where practitioners report contradictory feelings of both “horrible” and “good.”

Conclusion

This article analyzed the semiotic links between embodied, linguistic, and nonlinguistic signs found in a Bikram yoga studio in Oslo and on its website, which I argued are highly informed by other hegemonic sites of yoga circulation on a more global level, which include the Bikram franchise and Lululemon. Drawing on both onsite and digital ethnographic data, I employed the analytical concepts of both enregisterment (Agha Reference Agha2007) and mediatization (Agha Reference Agha2011), in order to trace these interlocking processes within three institutional sites that disseminate and transmit a (Bikram) yoga register by analyzing multimodal images both offline and online. The mediated messages found consisted of flexible, embodied, and highly commodified practices that were also dialectally embedded in physical, material, and technological environments. Such findings contribute to posthumanist theorization on how we understand language in relation to people, objects, and place, with the aim of broadening our understanding of communication to relocate where social semiotics occurs (Pennycook Reference Pennycook2018a, Reference Pennycook2018b).

The familiar, repetitive, monotonous, and thus mundane embodied practice of Bikram is an extremely intense sensory experience and illustrates how the body participates in a wide array of semiotic acts and processes within diverse material contexts. As such, it makes little sense to distinguish discourse and embodiment from other aspects of materiality. Material objects, including media platforms, bags, expensive yoga gear, and fringe fighting headbands, “cannot remain distinct or separated from the bodies that deploy them but in turn become relevant participants in and of themselves that are intricately intertwined in the coproduction of activities and meaning-making” on different levels (Bucholtz and Hall Reference Bucholtz2016, 187). The embodied, linguistic, and nonlinguistic signs investigated in these three sites, which consisted of the Bikram script, images, and yoga paraphernalia within BYO’s studio as well as the online images and text mediated on BYO’s and Lululemon’s website, worked together in creating a coherent semiotic register of the successful Bikram yoga persona, which is enregistered as a form of socially, culturally, physically fit, and flexible individual that also appears to be predominately White, female, and middle-class.

Indeed, my findings revealed that the ideological messages of physical fitness, flexibilization, self-discipline, and self-care were all linguistic and nonlinguistic signs indexed by (Bikram) yoga and its practitioners that resonate with neoliberal and capitalist values of the market economy. These registers were also mediated, disseminated, and circulated on Lululemon’s website, which trickled down into the physical spaces of the BYO studio, where recontextualization processes concerning symbolic and material values flourished. Such processes exemplified how a local yoga studio becomes a place where layered communicative and multimodal resources are used and exchanged for a range of commodities and capital. The register of Bikram yoga that emerged through embodied, linguistic, and nonlingustic signs offline in the studio and online on their website and Lululemon’s website co-construct and help create this style of yoga as an embodied global practice and thus global aesthetic grounded in twenty-first-century consumer capitalist pursuits, what Thurlow and Aiello (Reference Thurlow2007) refer to as global semioscapes. It appears therefore, that both BYO and Lululemon have been successful in captivating consumers through discursive, visual, and thus semiotic promotion and mediation of bodies in different ways that when appropriately consumed and trained may transcend physical and mental limits regardless of race, gender, age, and physical ability or at least give prospective customers this impression. By analyzing communicative and mediated messages, this study also shows the relevance of taking different materials, people, and places into consideration, which inevitably accounts for the diverse ways that and spaces where social semiotics occurs.