Throughout the nineteenth century, South America suffered not just from fraudulent elections but also from recurrent political violence. The French political scientist Alexis de Tocqueville ([Reference de Tocqueville1835] 1945, 251) remarked in 1835 that “the turmoil of revolution is … the most natural state of the South American Spaniards at the present time.” Two decades later, Bolivian President Manuel Belzú summarized the plight of many statesmen in the region when he complained of “[s]uccessive revolutions, revolutions in the south, revolutions in the north, revolutions fomented by my enemies, directed by my friends, put together in my house, arising from my side … holy God! They condemned me to a state of perpetual war” (cited in Aranzaes Reference Aranzaes1918, 158). The revolts took a terrible toll. They devastated economies, undermined national unity, and led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people.

The widespread revolts in South America also hindered the prospects for democracy in the region. Revolts sometimes led to the overthrow of elected leaders, thus interrupting constitutional rule. Between 1830 and 1899, rebels toppled South American presidents seventy-three times. Moreover, even when the rebels did not directly overthrow the government, they often destabilized it, leading to the eventual resignation and replacement of the president. Revolts also frequently interrupted elections. Opposition groups that sought to overthrow the government often tried to disrupt elections, attacking polling places, destroying ballot boxes, and driving off potential voters.

Revolts typically provoked repression from the state. Latin American governments facing rebellions often declared states of siege and suspended civil and political rights. They shut down or censored the independent media. They disqualified, harassed, and arrested opposition candidates, leaders, and supporters. Sometimes, they even suspended elections or banned opposition parties altogether. The widespread prevalence of revolts in South America thus led to a deepening of authoritarian rule in the region.

This chapter shows that the nineteenth-century revolts in South America were made possible by the weakness of the region’s militaries. The small, untrained, and poorly equipped South American armies of the nineteenth century could neither deter, nor easily suppress, revolts. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, however, most South American countries took important steps to strengthen and professionalize their militaries. Governments modernized their armed forces to deal with both external and internal threats, but it was the export boom of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century that provided the resources that made the military professionalization efforts possible. The export boom enabled South American governments to contract foreign military missions, create mass armies, import large numbers of sophisticated weapons, establish new military schools, and overhaul the basic organization, training, and procedures of the armed forces.

The strengthening of the military led to a dramatic reduction in revolts in South America at the outset of the twentieth century. A few countries that were slow to professionalize their militaries, such as Bolivia, Ecuador, and Paraguay, continued to experience frequent rebellions in the early twentieth century, but the other countries enjoyed an unprecedented degree of internal peace. To be sure, not all types of revolts came to an end. Insider revolts, especially military coups, remained prevalent throughout the twentieth century, but the most common type of revolt in the nineteenth century, the elite-led outsider rebellion, declined precipitously.

The decline in revolts brought tremendous benefits to the region. Increased political stability not only stimulated economic growth and investment, it also strengthened the rule of law, reduced state repression, and increased respect for civil and political liberties. As Chapters 5–6 show, the decline of revolts even paved the way for the emergence of democracy in a few countries in the region. Since they could no longer overthrow governments by force, opposition parties began to focus on the electoral path to power, pushing for democratic reforms that would level the electoral playing field.

This chapter is organized as follows. The first section documents the decline in revolts using LARD, an original and comprehensive data set on revolts in the region from independence onward.Footnote 1 It also presents a typology of revolts and shows how the frequency of different types of revolts changed over time and across countries. The second section discusses the theoretical literature on civil war and assesses to what extent it can explain trends in revolts. The third and fourth sections examine the evolution of state coercive capacity in South America from independence to 1929. These sections argue that the weakness of the region’s militaries encouraged outsider revolts during the nineteenth century but that the professionalization of the military at the turn of the century dramatically reduced these rebellions. The fifth section presents a statistical test of this argument, showing that indicators of military strength and professionalization are correlated with the number of outsider revolts, but not insider revolts, in South America. The concluding section briefly summarizes the arguments made in this chapter.

The Decline in Revolts in South America

How frequent were revolts in South America during the nineteenth and early twentieth century? How did they vary over time and across countries? Existing studies have lacked the data to answer these questions with any precision. Indeed, the sheer number of revolts has led some scholars to despair of the possibility of counting them all (Centeno Reference Centeno2002, 61; Loveman Reference Loveman1999, 43). To come up with a comprehensive count of revolts for LARD, we drew on more than 250 historical sources that cover rebellions in the region from 1830 to 1929.Footnote 2 We define a revolt as an instance of the use or the credible threat of violence by an identifiable domestic political group that defies the authority of the state. We use the terms revolts and rebellions interchangeably.

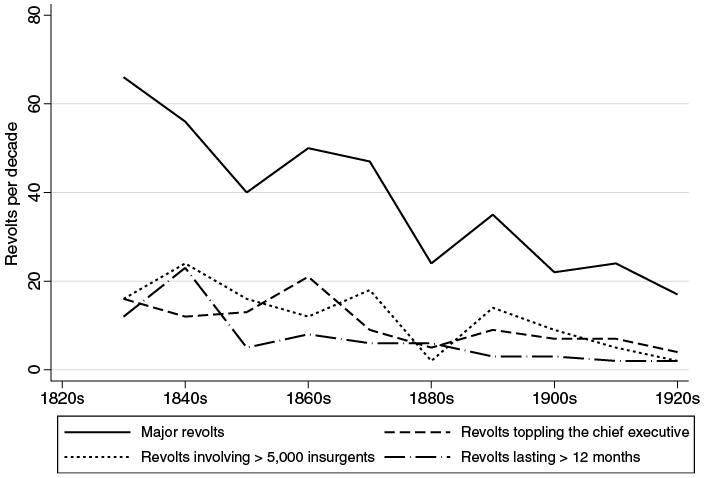

LARD reveals a dramatic decline in major revolts in South America from the nineteenth to the twentieth century, as Figure 3.1 indicates.Footnote 3 This chapter focuses on major revolts, defined as those involving at least 500 rebels, because they are the most important types of rebellions. Moreover, data on them are more plentiful, which reduces measurement and identification error. From 1830 to 1899, there were on average forty-five active major revolts per decade, meaning that each country had an almost even chance of facing an important rebellion in any given year. By contrast, in the first three decades of the twentieth century, this average declined to twenty-one, or an approximately one-fifth chance of seeing a major rebellion in any given year. While the decline is partly due to the longer duration of revolts in the nineteenth century, the finding holds when we look at revolt onsets alone: An average of thirty revolts were initiated per decade in the nineteenth century, as opposed to only fifteen per decade in the early twentieth century. Similar trends are apparent if we focus on especially large, lengthy, or impactful rebellions. As Figure 3.1 shows, revolts that involved more than 5,000 rebels, lasted for more than one year, and led to the overthrow of the chief executive all declined dramatically during the early twentieth century, amounting to only a handful of cases by the 1920s.

Figure 3.1 The decline of major revolts in South America by decade, 1830–1929

The frequency of major revolts varied across countries as well as time. Argentina, with an average of eight major revolts per decade, was the most rebellious country between 1830 and 1899. By contrast, Chile and Paraguay had the fewest major revolts during this period. All South American countries experienced a decline in the number of revolts during the first three decades of the twentieth century, with the sole exceptions of Ecuador and Paraguay.

Not all types of revolts declined at the same rate, however. To explore variation across different types of revolts, we identified four distinct categories based on whether the leader of the revolt came from inside or outside the national state apparatus, and whether the rebel leader hailed from the elites or the masses.Footnote 4 Our typology, which is depicted in Table 3.1, is based to a large degree on previously conceptualized revolt types, such as coups, but it also introduces an important additional type of revolt, elite insurrections (i.e., revolts led by elites based outside the state apparatus), that had not previously been conceptualized by political scientists.Footnote 5 Alternative categorizations which focus on the consequences of the revolts cut across our categories. Civil wars, for example, typically refer to revolts by nonstate actors that exceed a battle-death threshold of 1,000 – any of our revolt types may become civil wars if they escalate (Fearon Reference Fearon2004).

Table 3.1 A typology of revolts based on the origins of their leaders

| Position of rebel leaders vis-à-vis the national state apparatus | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Insiders | Outsiders | ||

| Socioeconomic position of rebel leaders | Elites | Coup | Elite insurrection |

| Masses | Mutiny | Popular uprising | |

In line with extant databases, we define coups as “illegal and overt attempts by the military or other elites within the state apparatus to unseat the sitting executive” (Powell and Thyne Reference Powell and Thyne2011, 252). The vast majority of coups originate in the military, although coups may also be undertaken by high-ranking government officials, such as cabinet ministers. We identify sixty-six major coup attempts between 1830 and 1929.

Elite insurrections are revolts led by elites from outside of the state apparatus. They may consist of local elites attempting to secede or opposition parties or politicians taking up arms to overthrow the government. Elite insurrections were by far the most common type of major revolt between 1830 and 1929: We record 152 of them during this period.

Popular uprisings refer to rebellions led by subalterns who are located outside of the state, which would include indigenous revolts, violent labor protests, and slave rebellions. We identify thirty-four major popular uprisings during this period.

Finally, mutinies consist of revolts from within the state by nonelites, such as rank-and-file soldiers or noncommissioned officers. Mutinies typically did not meet our threshold of 500 rebels required to count as major revolts, so we do not discuss them at length.

The leadership of revolts matters for at least two reasons. First, the leaders help determine the likelihood of success of the revolts. Revolts led by insider elites, such as coups, are more likely to succeed because insider elites tend to have greater access to resources, including troops, weaponry, financing, and the media. Between 1830 and 1929, almost 71 percent of coup attempts in South America overthrew the government, as opposed to only 30 percent of elite insurrections and 3 percent of popular uprisings.Footnote 6 Second, the origins of the rebel leaders also impact the size and costs of the revolts. Whereas insider rebellions tend to be resolved quickly and with minimal bloodshed, outsider revolts are usually more prolonged and more violent. Between 1830 and 1929, 21 percent of popular uprisings and 14 percent of elite insurrections in South America lasted more than one year, as opposed to 6 percent of coups. Similarly, 29 percent of outsider revolts led to more than 1,000 battlefield deaths in comparison to only 10 percent of coups.

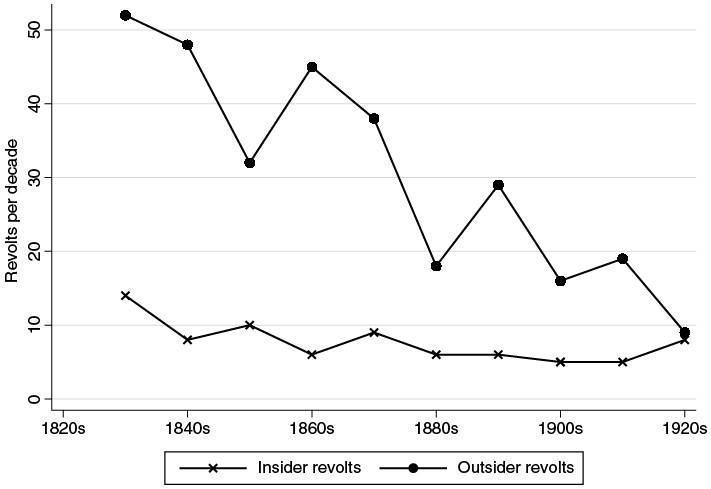

Even more important for our purposes, disaggregating revolts by the origins of their leaders helps shed light on the decline in revolts from the nineteenth to the twentieth century. As Figure 3.2 shows, the decline was driven by a sharp drop in the number of outsider revolts – that is, revolts from outside the state apparatus. During most of the nineteenth century, there were three times as many outsider rebellions as insider revolts, but by the 1920s their numbers were roughly the same.

Figure 3.2 The frequency of major insider and outsider revolts in South America, 1830–1929

In sum, LARD shows that during the early twentieth century there was a sharp decline in revolts in South America, and the large, bloody, and lengthy internal conflicts that plagued the region during the nineteenth century mostly came to an end. Outsider revolts drove the decline in political violence – they declined precipitously, whereas insider revolts remained relatively stable. As we shall see, the divergent trends in insider and outsider revolts can be explained by the modernization of South American militaries at the beginning of the twentieth century since the growing strength of the region’s armies discouraged outsider revolts but not military coups.

Explaining the Decline in Revolts

The historical literature has stressed that nineteenth-century revolts in South America were complex and had a wide variety of causes, but most of most of this literature focuses on the motivations of the rebels. Scheina (Reference Scheina2003, xxiii), for example, argues: “The causes for wars in in Latin America during the nineteenth century are numerous and create a vivid, plaid tapestry … The most vivid threads have been the race war, the ideology of independence, the controversy of separation versus union, boundary disputes, territorial conquests, caudilloism, intraclass struggles, interventions caused by capitalism, and religious wars.” Safford (Reference Safford1992; Reference Safford and Earle2000), meanwhile, identifies five types of explanations for these revolts, including cultural factors, economic structures, fiscal weakness, changing power relations among elite groups, and conflicting ideologies and interests. Various scholars have also shown how electoral fraud, or allegations of it, often triggered revolts. (Malamud Reference Malamud and Earle2000c; Posada-Carbó Reference Posada-Carbó1996b; Alonso Reference Alonso2000). Indeed, during the nineteenth century, revolts were considered a legitimate response to electoral manipulation and other forms of despotism (Sabato Reference Sabato2018, 112–115; Earle Reference Earle and Earle2000a, 3–4).

Much of the general social science literature on political violence similarly focuses on the motivations of the rebels, or what the literature has sometimes referred to as grievances and greed. The conflict literature, for example, has extensively explored the role that economic factors (Blattman and Miguel Reference Blattman and Miguel2020, 45; Bell Reference Bell2016, 1170), ethnic and religious cleavages (Cederman and Girardin Reference Cederman and Girardin2007; Roessler Reference Roessler2011; Bormann, Cederman, and Vogt Reference Bormann, Cederman and Vogt2017; Esteban, Mayoral, and Ray Reference Esteban, Mayoral and Ray2012), and regime type (Fearon and Laitin Reference Fearon and Laitin2003, 84–85; Powell Reference Powell2012, 1035; Hegre et al. Reference Hegre, Ellingsen, Gates and Gleditsch2001) have played in revolts.

Although rebel motivations are important, they cannot fully explain long-term trends in South American revolts. Rebel motives do not explain why insurgents were able to assemble their armies and fend off or defeat government troops, irrespective of their motivations. Moreover, an emphasis on rebel motivations cannot easily account for the dramatic decline in revolts that occurred at the outset of the twentieth century, since authoritarian regimes, ethnic cleavages, electoral fraud, interstate rivalries, and economic hardships continued to be widespread.

Another approach in the conflict literature focuses on the weakness of the state, rather than the motivations of rebels, as the main cause of revolts (Fearon and Laitin Reference Fearon and Laitin2003; Hendrix Reference Hendrix2010; Fearon Reference Fearon2010). Stemming in part from the study of revolutions (Skocpol Reference Skocpol1979), this approach “has become the dominant explanatory paradigm in the civil war literature” (Cederman and Vogt Reference Cederman and Vogt2017, 1997). The weak state approach suggests that motivations for rebellion (grievances and greed) are widespread, but they only tend to result in significant revolts where the state lacks the ability to prevent or suppress rebellions. Revolts occur, in the words of one influential study, because “financially, organizationally, and politically weak central governments render insurgency more feasible and attractive due to weak local policing or inept and corrupt counterinsurgency practices” (Fearon and Laitin Reference Fearon and Laitin2003, 75–76).

Building on this approach, as well as on the work of historians, we focus on a specific dimension of state capacity: military strength. We define military strength as not simply the number of troops but also the degree of its professionalization – that is, the sophistication of the weaponry, training, and leadership that the military possesses. We argue that revolts occurred frequently during the nineteenth century because South American countries had small armies that were poorly equipped, trained, and led. Once these states expanded and professionalized their armed forces in the early twentieth century, the number of revolts in the region declined precipitously. Strong militaries could defeat uprisings before they became major revolts, but, even more importantly, military strength discouraged rebellions. Would-be rebels were unlikely to revolt if they believed that the rebellions would be quickly suppressed by a powerful military.

To be sure, this is not the first study to suggest that military professionalization reduced revolts in South America in the twentieth century.Footnote 7 Nevertheless, we go well beyond existing studies in documenting how increased military strength led to the regionwide decline. In addition, we show that increased military strength explains not only why revolts diminished in South America from the nineteenth to the twentieth century but also why this happened more rapidly in some countries than others, since not all states expanded and professionalized their militaries at the same time or to the same degree. Of equal importance, we demonstrate that growing military strength explains why outsider revolts decreased in South America at the outset of the twentieth century while insider revolts did not.

Although military professionalization is supposed to marginalize the military from politics and establish clear civilian control over the military (Huntington Reference Huntington1957), it did not achieve these aims in South America. As Stepan (Reference Stepan and Stepan1973) has argued, militaries in this region have traditionally been responsible for maintaining internal as well as external security, which provided them with a rationale to intervene in politics.Footnote 8 The armed forces overthrew civilian leaders not just to resolve perceived threats to national security but to safeguard their own interests as well as those of allied political elites. According to Rodríguez (Reference Rodríguez and Rodríguez1994, xiii), “professionalization had the long-term effect of politicizing the armed forces to defend their corporate interest, which they identified as synonymous with those of the nation.” Military professionalization may have even encouraged some coups by enhancing the confidence and autonomy of military officers and persuading some officers that they could do a better job of governing than civilian leaders (Rouquié Reference Rouquié1987, 102–104; Fitch Reference Fitch1998, 6–7). Increases in military budgets and personnel also increased the influence of the armed forces and the number of potential coup conspirators, thereby complicating coup-proofing efforts. As a result, insider revolts, in contrast to outsider revolts, did not decline significantly in the wake of the professionalization of South American militaries.

The Weak Armies of Nineteenth-Century South America

The weakness of South America’s militaries during the nineteenth century stemmed from a variety of factors, including: the small size of the region’s armies, their rudimentary weaponry, the paucity of military discipline and training, and the politicization of the officer corps.Footnote 9 In addition, South American states decentralized security, creating militias which sometimes turned against the national government. All these shortcomings fostered outsider revolts.

South American governments could not afford to invest in their militaries for most of the nineteenth century because they were starved of funds, especially foreign currency. The wars of independence disrupted trade and destroyed Latin American economies; and political instability, combined with a lack of infrastructure and inefficient policies, slowed economic recovery in the decades that followed. Per capita GDP grew at a rate of less than 0.6 percent annually between 1820 and 1870 in South America (Bértola and Ocampo Reference Bértola and Ocampo2013, 62). The small size of South American economies and their low rates of growth meant that their governments generated little tax revenue and could not afford to spend much on their armed forces.

Even though military expenditures were relatively low, they typically accounted for a large share of state spending, reducing the ability of South American governments to address other needs (Centeno Reference Centeno2002, 119–121). After the wars of independence, South American governments reduced the size of their militaries to alleviate these fiscal burdens. Most armies remained quite small throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century, particularly compared to their European counterparts. According to Centeno (Reference Centeno2002, 224–225), less than 0.5 percent of the population usually participated in the militaries of South American countries. Bolivia’s army typically numbered fewer than 2,000 men during the nineteenth century (Dunkerley Reference Dunkerley2003, 71). The Colombian military never exceeded 4,000 troops before the 1880s and it often had fewer than 2,000 men (López-Alves Reference López-Alves2000, 138; Payne Reference Payne1968, 120).

When a foreign or domestic threat required it, South American militaries usually swelled, but in a rather ad hoc way. During wartime the military would sweep through urban neighborhoods and rural villages, press-ganging whatever able-bodied men they could find. A popular saying of the time was: “If you want more volunteers, send more chains” (cited in Johnson Reference Johnson1964, 54).

As might be expected, the discipline and training of the troops were poor. The troops’ wages were miserable, the government sometimes fell into arrears on payments, and soldiers frequently deserted despite severe punishments for doing so (Rouquié Reference Rouquié1987, 65). Soldiers came overwhelmingly from the poorest sectors of the population and typically had little, if any, education. Most of the soldiers were illiterate and many were vagrants and even criminals: Colombia reported in 1882 that only 30 percent of its troops could read (Deas Reference Deas and Dunkerley2002a, 92). Moreover, the armed forces provided little military training to the troops. As Resende-Santos (Reference Resende-Santos2007, 121) notes: “Prior to the 1880s, none of the regional militaries had a standardized system of enlistment, training, and reserves.”

Military officers in South America also lacked proper training and organization during this period. According to Loveman (Reference Loveman1999, 30), the nineteenth-century armies “were not organized under an operational general staff, did virtually no planning for diverse military threats, carried out few military exercises, and were unprepared for sustained combat.” Army officers rarely attended military schools: In 1893 the Argentine War Ministry reported that only 30 of its approximately 1,400 army officers had received advanced training or graduated from a military academy (Resende-Santos Reference Resende-Santos2007, 122). Some South American governments founded military academies during the nineteenth century, but these typically operated irregularly, and their curriculums were woefully outdated. Political connections, rather than military expertise, determined ascent in the officer ranks (Johnson Reference Johnson1964, 52–53; Resende-Santos Reference Resende-Santos2007, 122; Loveman Reference Loveman1999, 42–43; Philip Reference Philip1985, ch. 4; Rouquié Reference Rouquié1987, 64–65). In many South American countries, widespread promotions led to an excess of officers, particularly at the higher ranks. Bolivia, for example, had one general for every 102 soldiers and one officer for every six soldiers in 1841 (Scheina Reference Scheina2003, 263; Dunkerley Reference Dunkerley2003, 18). Venezuela’s officer ranks were even more bloated: A census of the state of Carabobo in 1873 counted 3,450 commissioned officers, including 627 colonels and 449 generals, out of a population of 22,952 (Philip Reference Philip1985, 87).

South American militaries also lacked sophisticated weaponry for most of the nineteenth century, relying on pointed weapons, such as the lance, the pike, the sword, and the machete, rather than on firearms (Scheina Reference Scheina2003, 427). Arráiz (Reference Arráiz1991, 151) writes that during the revolts: “Combat took place in a series of personal encounters in which people attacked each other with lances, swords, bayonets, fists and whatever was at hand.”Footnote 10 Both sides typically had some firearms, but these were primitive weapons with limited range and accuracy. Even when South American militaries did obtain more sophisticated weapons, they often had problems repairing and servicing them, and sometimes let them slip into the hands of the rebels (Arráiz Reference Arráiz1991, 157; Somma Reference Somma2011, 236; Scheina Reference Scheina2003, 427).

During the nineteenth century, most South American governments reorganized and expanded their civic guards or urban and provincial militias, which had existed since colonial times (Sabato Reference Sabato2018, 90–96). These militias were less expensive to maintain than the regular army, but they did little to enhance the authority of the central state. First, militia members typically had little training or equipment, although there were exceptions, such as in Brazil where the state militias, especially those of São Paulo and Minas Gerais, gradually became better trained and armed than the federal army (Resende-Santos Reference Resende-Santos2007, 124). South American governments usually required members of the militias to provide their own weapons and training, but the members often did not own firearms and drilled rarely if at all. In the Rio de la Plata region, the members of militias only trained one or two days per month during peace time (Rabinovich and Sobrevilla Perea Reference Rabinovich and Perea2019, 784).

Second, militias could not be counted on to support the government. Indeed, they often formed the main base of rebel armies, which was particularly problematic given that in most countries the militia troops vastly outnumbered the army.Footnote 11 In Argentina, provincial militias typically supplied both the troops and the weapons that were used in revolts during the nineteenth century (Forte Reference Forte2002; Gallo Reference Gallo and Bethell1986, 379), and in Brazil the local militias of southern states sustained a ten-year campaign against the imperial army during the Ragamuffin War (Ribeiro Reference Ribeiro2011, 271). In some cases, the militias were set up or expanded to counterbalance the regular army. In Uruguay, for example, the Blanco Party built up a civic guard to offset the Colorado Party-dominated army (López Chirico Reference López Chirico1985, 29–30; Somma Reference Somma2011, 150). Despite periodic efforts to centralize control, in most countries the militias remained under the leadership of provincial or local authorities (Sabato Reference Sabato2018, 98–99).Footnote 12 In many rural areas, local leaders controlled unofficial militias, which often participated in rebellions and guerrilla warfare (Rabinovich and Sobrevilla Perea Reference Rabinovich and Perea2019, 785).

It is not a coincidence that the two South American countries that had perhaps the highest coercive capacity during much of the nineteenth century (Chile and Paraguay) also had the fewest revolts. Chile did not avoid internal revolts all together – it experienced numerous revolts prior to 1860 and a civil war in 1891, but its military prowess, demonstrated in the War of the Pacific (1879–1883), deterred most domestic rebels in the late nineteenth century. Chile developed a strong military during this period, not by expanding its size, but rather by making early investments in foreign training – the Chilean government sent officers to study in France beginning in the 1840s and hired a small French training mission in 1858 – as well as in tactics and weaponry (Ramírez Necochea Reference Ramírez Necochea1985, 39–40; Hillmon Jr. Reference Hillmon1963, 76; Valenzuela Reference Valenzuela1985, 182). Early on, Chile also asserted centralized control of its national guard, which played an important role in squashing rebellions as well as turning out votes for the ruling party (Sabato Reference Sabato2018, 107, 110–111; Valenzuela Reference Valenzuela and Posada-Carbó1996, 228–231). As discussed later in this chapter, the Chilean military grew even stronger after a large German military mission arrived in 1885.

Paraguay also initially enjoyed relative political stability thanks to its considerable military strength. During the mid-nineteenth century, Paraguay developed one of the largest and strongest militaries in the region. The Paraguayan government imported massive quantities of weapons, overhauled the training of the troops, and brought in foreign officers, most notably the Hungarian Lieutenant Colonel Francisco Wisner, to modernize and discipline its army (Williams Reference Williams1979, 110–111, 179; Whigham Reference Whigham2002, 182; Hanratty and Meditz Reference Hanratty and Meditz1988, 24). It even built up an important domestic arms industry. By 1864–1865, the Paraguayan army had 30,000–38,000 troops, including thirty infantry regiments, twenty-three cavalry regiments, and four artillery regiments, and the military could count on an additional 150,000 men in its reserves (Hanratty and Meditz Reference Hanratty and Meditz1988, 205; Casal Reference Casal, Kraay and Whigham2004, 187). The country’s military strength effectively deterred revolts prior to the War of the Triple Alliance (1865–1870). In this war, however, the combined forces of Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay destroyed the Paraguayan military. Consistent with our theoretical expectations, in the decades that followed, Paraguay was plagued by revolts.

Military Strengthening

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, South American nations undertook major efforts to professionalize their militaries, often with the assistance of foreign military missions. They expanded the size of their armies, upgraded their weaponry, established new military schools, adopted meritocratic criteria for officer recruitment and promotion, and banned private arms imports and local militias. As a result, the military strength of South American countries increased and outsider revolts declined significantly, both in number and intensity, during the first few decades of the twentieth century. The only countries that continued to have numerous outsider revolts were those with the weakest militaries.

South American countries expanded and professionalized their militaries during this period for two main reasons: the export boom and the continuing threat of interstate war. The export boom was the permissive condition (i.e., it provided the necessary resources to invest in the military) and the threat of interstate war was the productive condition, because it made military strengthening a pressing necessity.

South American countries experienced a significant amount of international conflict in the nineteenth century, which put pressure on their governments to build up their militaries. The War of the Triple Alliance (1864–1870), with an estimated 290,000 casualties, was the bloodiest interstate war of that period, exceeding even the Crimean War (Clodfelter Reference Clodfelter2017, 180).Footnote 13 The other major South American war of this period, the War of the Pacific (1879–1883), had casualty levels similar to the average European conflict of the time. Although there were no major wars in the region between 1884 and 1929, the region continued to suffer from numerous militarized conflicts (Ligon Reference Ligon2002; Hensel Reference Hensel1994). Mares (Reference Mares2001, 77) reports that between 1884 and 1918 alone, South American countries had thirty-one militarized interstate disputes, in which military force was used, threatened, or displayed. Holsti (Reference Holsti1996, 153) notes that in the region, “one sees patterns of peace and war, intervention, territorial predation, alliances, arms-racing, and power-balancing quite similar to those found in eighteenth-century Europe.”

These conflicts provided two type of exogenous shocks affecting military strength. First, the threat of war forced every country to expand, modernize, and often mobilize its armed forces. South American countries may not have risked annihilation in international conflicts, but they certainly risked losing territory and lives. For this reason, once one country strengthened its military, its neighbors and rivals felt compelled to do the same. As Resende-Santos (Reference Resende-Santos2007, 37) puts it, “[i]ntensifying military competition and war, in turn, prompted a chain reaction of large-scale military emulation,” resulting in military modernization that was “of a scale, intensity and duration not previously known in the region.”

Second, war outcomes had an independent effect on military strength since defeat in war typically resulted in military downsizing, which was often imposed by the winners. Victory in war, meanwhile, frequently led to military expansion, either for the purposes of manning occupations or because of the newly acquired legitimacy and popularity of the military. Of these two types of shocks, the threat of war had the most important and longest-lasting effects, since the threat of conflict was more pervasive in South America than actual war.

Military strengthening was costly, but the export boom of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century brought new revenues to South American governments.Footnote 14 The real value of exports increased almost tenfold, from less than $1.3 billion in the early 1870s to $12.4 billion in the late 1920s in constant 1980 dollars, thanks in part to infrastructure improvements, technological developments, more liberal economic policies, and growing world demand (Bértola and Ocampo Reference Bértola and Ocampo2013, 86, 97; Coatsworth Reference Coatsworth, Coatsworth and Taylor1998, 39–42). At the same time, foreign investment flowed into the region, climbing from $1.1 billion in 1880 to $11.2 billion in 1929 (Bértola and Ocampo Reference Bértola and Ocampo2013, 124). Foreign investment helped capitalize the export sector and build infrastructure, such as railroads and ports, which made the exports possible. The expansion of foreign trade and investment not only provided the foreign currency to pay for weapons imports and foreign military missions, it also provided incentives to build up the military, since the export boom depended on the ability of South American states to control the areas where export commodities were produced. Export booms also fueled conflict by creating incentives to wrestle land from neighboring states and by bringing miners, farmers, and speculators into disputed areas. The War of the Pacific, for example, originated in a dispute between Bolivia and Chile over nitrate-rich lands in the Atacama Desert.

Military competition was more intense where the threats of war were more pressing and where resources were more readily available (Resende-Santos Reference Resende-Santos2007). Wealthier South American countries, especially those in the midst of export booms, such as Chile and Argentina, could more easily afford to make large investments in their armed forces. Indeed, Chile and Argentina engaged in a formidable arms race in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and nearly went to war on several occasions between 1898 and 1902.Footnote 15 The victories of Argentina and Chile in foreign wars during the late nineteenth century contributed to the arms race by strengthening their militaries, energizing nationalist sentiments, and stiffening their positions on territorial disputes.

Surrounded by foes, Chile was the first mover in the turn-of-the-century process of military modernization, engaging a German mission headed by Captain Emil Körner in 1885. Argentina responded by hiring military advisers in the 1880s, and in 1899 it, too, engaged a German military mission. Bolivia and Peru, which continued to claim the land Chile had conquered in the War of the Pacific, responded in kind. Peru hired a French mission in 1895, bringing in thirty-three French officers to teach in Peruvian military schools between 1896 and 1914 (Nunn Reference Nunn1983, 114–117; Hidalgo Morey et al. Reference Hidalgo Morey, Montoya, Ortíz and Ríos2005, 349–352). The Bolivian military also hired various foreign officers to teach in its military schools during the 1890s, and in 1905, its first French military mission arrived, followed by a German mission in 1910. The foreign missions gradually spread outward from Chile and its neighbors to the other South American countries. Some of these countries, such as Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay, engaged European missions or advisers, but others, such as Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela, hired Chilean military advisers to impart the Prussian model and sent their own military officers to train in Chile (Arancibia Clavel Reference Arancibia Clavel2002).

With the support of the foreign missions, most South American countries moved to expand the size of their militaries by enacting laws that mandated military service. Chile was the pioneer again, instituting universal obligatory military service in 1900 (Resende-Santos Reference Resende-Santos2007, 135–138). In response, Argentina enacted a similar conscription law in 1901, and by 1910 it could field a standing force of 250,000 men, if needed (Resende-Santos Reference Resende-Santos2007, 201–202; Nunn Reference Nunn1983, 128–129). Meanwhile, Uruguay doubled and Peru and Venezuela tripled the size of their respective armies (Moore Reference Moore1978, 40; Klarén Reference Klarén and Bethell1986, 601).

South American militaries also sought to improve the training of officers and troops by opening new military institutes and adopting meritocratic criteria for the promotion of officers. In Chile, Körner revamped military training along Prussian lines: The government created highly selective military academies for junior officers as well as noncommissioned officers in 1887, and subsequently established specialized schools for the infantry, cavalry, and engineers (Sater and Herwig Reference Sater and Herwig1999, 44). In addition, 130 Chilean officers were sent to Germany for further training between 1895 and 1913 (Resende-Santos Reference Resende-Santos2007, 138–141). The Argentine military similarly modeled its educational curriculum on Germany’s war academy, employing various German officers as instructors and sending between 150 and 175 officers to train in Germany (García Molina Reference García Molina2010, 47–65; Potash Reference Potash1969, 4; Resende-Santos Reference Resende-Santos2007, 203–206; Schiff Reference Schiff1972). With the support of its Chilean mission, the Colombian government established several institutions to train military officers and adopted meritocratic criteria for promotion (Arancibia Clavel Reference Arancibia Clavel2002, 385–386; Atehortúa Cruz and Vélez Reference Atehortúa Cruz and Vélez1994, 60–63; Cardona Reference Cardona2008, 88–91).

Most South American countries also imported a massive amount of foreign weaponry during this period. In the 1890s, for example, Chile undertook a major purchase of Krupp artillery, along with 100,000 Mauser rifles (Resende-Santos Reference Resende-Santos2007, 134). In 1889, Argentina acquired 60,000 German Mauser rifles, and in 1894, when tensions with Chile were high, it purchased so much equipment that, according to one high-ranking military official, it could “burn half of Chile” (Ramírez Jr. Reference Ramírez1987, 183; Resende-Santos Reference Resende-Santos2007, 198). During the early 1900s, Brazil also purchased several hundred thousand Mauser rifles as well as Krupp cannons from the Germans (McCann Reference McCann1984, 746; Nunn Reference Nunn1972, 35; Resende-Santos Reference Resende-Santos2007, 252–253), whereas Uruguay imported Krupp cannons, Colt and Maxim machine guns, and enough Mauser and Remington rifles to arm 50,000 men (Somma Reference Somma2011, 160; Vanger Reference Vanger1963, 89, 95; López Chirico Reference López Chirico1985, 42). Venezuela similarly strengthened its military by purchasing Mauser rifles, Krupp artillery, and Hotchkiss machine guns, among other weapons (Scheina Reference Scheina2003, 248; Straka Reference Straka, Irwin and Langue2005, 103; Schaposnik Reference Schaposnik1985, 20).

South American governments also took steps to gain a monopoly on the use of force by restricting the ability of nongovernmental entities to import arms and by asserting control over or eliminating regional and private militias. These measures were also driven in part by international competition, which put pressure on military organizations to become more centralized and cohesive to prevent autonomous forces from being co-opted by foreign foes and used as fifth columns. As part of a process of centralization of the armed forces that started during the War of the Triple Alliance, the Argentine government passed a law in 1880 that prohibited “provincial authorities from forming military forces” (Sabato Reference Sabato and Moreno2010, 137). It also dissolved the national guard and integrated it into the army as a reserve force, boosting its numbers by 65,000 men (Nunn Reference Nunn1983, 48). Countries that were further away from the intense competition of the Southern Cone were slower to centralize military power, but they would eventually implement similar reforms. The Colombian government initiated a program in the early 1900s to gain control of the many weapons its citizens had stockpiled during the War of a Thousand Days and earlier. By 1909, this program had collected 65,505 guns and 1,138,649 bullets, making it more difficult for potential rebels to arm themselves (Bergquist Reference Bergquist1978, 225; Esquivel Triana Reference Esquivel Triana2010, 265; Atehortúa Cruz Reference Atehortúa Cruz2009, 21). Similarly, Venezuela restricted the extent of weapons available to private citizens and subnational states in the early twentieth century (McBeth Reference McBeth2008, 6, 79–80), and in 1919 it abolished state militias (Blutstein et al. Reference Blutstein, Edwards, Johnston, McMoriss and Rudolph1985, 248; Schaposnik Reference Schaposnik1985, 21).

Table 3.2 displays the ten South American countries’ average scores between 1870–1899 and 1900–1929 on three different indicators of military strength and professionalization. These indicators are: the number of military personnel (in thousands), which is from the Correlates of War Project (2020); the number of military academies, which was compiled by Toronto (Reference Toronto2017); and a variable from V-Dem that measures the degree to which appointment decisions in the armed forces are based on merit (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge2020).Footnote 16 The data on merit-based promotions and the number of military academies should be viewed with some caution, but they represent the best available quantitative measures on military professionalization for this period.

Table 3.2 Indicators of military strength and professionalization in South America, 1870–1929

| Country | Military size (1870–1899) | Military size (1900–1929) | Military academies (1870–1899) | Military academies (1900–1929) | Merit-based promotions (1870–1899) | Merit-based promotions (1900–1929) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong militaries | ||||||

| Argentina | 11.6 | 29.0 | 1.93 | 2.60 | 3.34 | 3.34 |

| Brazil | 28.3 | 38.1 | 2.00 | 2.37 | 2.73 | 2.73 |

| Chile | 9.4 | 24.9 | 2.00 | 2.57 | 1.59 | 2.92 |

| Middle militaries | ||||||

| Colombia | 3.6 | 6.3 | 2.00 | 2.30 | 0.76 | 0.76 |

| Peru | 6.5 | 7.8 | 0.13 | 1.63 | 1.32 | 1.32 |

| Uruguay | 3.2 | 8.5 | 1.00 | 1.90 | 0.87 | 1.28 |

| Venezuela | 5.3 | 8.7 | 2.00 | 2.33 | 0.71 | 0.85 |

| Weak militaries | ||||||

| Bolivia | 2.4 | 4.2 | 0.30 | 1.00 | 1.25 | 1.25 |

| Ecuador | 2.9 | 5.6 | 2.00 | 2.33 | 2.01 | 2.01 |

| Paraguay | 1.4 | 2.7 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.23 | 0.99 |

| Regional average | 7.5 | 13.6 | 1.34 | 1.90 | 1.58 | 1.75 |

Note: Military size refers to the number of soldiers in thousands.

The indicators show that the strength and degree of professionalization of the military increased appreciably throughout South America from the late nineteenth century to the early twentieth century. Collectively, the data also indicate that by the early twentieth century, Argentina, Brazil, and Chile had the strongest militaries in South America, whereas Bolivia, Ecuador, and Paraguay had the weakest armed forces.Footnote 17 Not surprisingly, the larger and wealthier countries of the region tended to have stronger militaries since they could afford to spend more on their militaries than could smaller and poorer nations.

Although the strengthening of South American militaries was mostly driven by international threats, it discouraged internal revolts because would-be rebels knew that they had little chance of prevailing over strong, professional militaries. In 1911, for example, some leaders of the opposition Blanco Party in Uruguay sought to carry out a revolt, but the party blocked them, stating that the rebels would be at a “notorious disadvantage,” given the strength of the military which was evidenced by the disastrous failure of previous revolts (Vanger Reference Vanger1980, 151–152). Similarly, in 1917, the Blanco leader Basilo Muñoz persuaded the party to sign a pact with the government and compete in elections because armed revolt would be futile (Vanger Reference Vanger2010, 232). In Colombia as well, the professionalization of the military at the outset of the twentieth century deterred revolts that had been commonplace during the nineteenth century. Many Liberals wanted to rebel in response to the widespread fraud in the 1922 elections, but General Benjamín Herrera, the Liberal leader and presidential candidate that year, dissuaded them in part because the strength of the country’s military gave them little hope of success (Maingot Reference Maingot1967, 165–166).

As a result of the strengthening of the military, the number of outsider revolts fell from twenty-two per decade between 1830 and 1899 to nine per decade between 1900 and 1929. Revolts from outside the state apparatus declined in large part because political outsiders recognized they had little chance of defeating professional militaries. Popular uprisings had always been highly unlikely to overthrow governments in South America and none did so between 1900 and 1929, but elite insurrections also became increasingly unlikely to prevail. During the 1900–1929 period, only five elite insurrections succeeded in overthrowing a government, whereas thirty-eight had done so between 1830 and 1899. Moreover, four of the five successful elite insurrections between 1900 and 1929 occurred in the South American countries with the weakest militaries.

As Table 3.3 indicates, the strengthening and professionalization of the military helped bring political stability to many South American countries in the early twentieth century. Between 1900 and 1929, countries with strong militaries experienced fewer outsider revolts and executive overthrows than did countries with militaries of medium strength. And countries with militaries of medium strength experienced far fewer outsider revolts and executive overthrows than did countries with weak militaries.

Table 3.3 The varying stability of regimes in South America, 1870–1929

| Major outsider revolts (1870–1899) | Major outsider revolts (1900–1929) | Executive overthrows (1870–1899) | Executive overthrows (1900–1929) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong militaries (1900–1929) | ||||

| Argentina | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Brazil | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Chile | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Medium militaries (1900–1929) | ||||

| Colombia | 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Peru | 4 | 2 | 6 | 2 |

| Uruguay | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Venezuela | 6 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Weak militaries (1900–1929) | ||||

| Bolivia | 9 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Ecuador | 7 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Paraguay | 5 | 7 | 3 | 8 |

Outsider revolts almost entirely disappeared in the nations that developed the strongest militaries post-1900. Partly as a result of its military professionalization efforts, Chile experienced no outsider revolts during the first three decades of the twentieth century, although it did have a couple of military coups in the 1920s. Argentina suffered the most revolts of any South American country during the nineteenth century, but its enormous military buildup during and after the War of the Triple Alliance helped deter outsider revolts in the twentieth century. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, it only experienced one elite insurrection, the Radical revolt of 1905, and this was quickly squashed.Footnote 18 Outsider revolts also gradually diminished in Brazil in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century as the government gradually strengthened its military. Nevertheless, Brazil’s vast size and the ruggedness of its terrain made it difficult to stifle outsider revolts when they did occur. Between 1912 and 1916, for example, the Brazilian military struggled to defeat a popular uprising, dubbed the Contestado War, by poor settlers in the remote frontier area bordering Argentina. This rebellion posed no real threat to the national government, however; nor did the few insider revolts Brazil experienced in the early twentieth century.

The countries with medium-strength militaries also experienced a dramatic decline in outsider revolts during the late nineteenth century. Colombia, for example, suffered no major outsider revolts in the first three decades of the twentieth century, after experiencing six between 1870 and 1899. Nor were there any major outsider revolts in Venezuela after 1903 or in Uruguay after 1910, thanks in large part to their efforts to strengthen their armed forces. Peru also experienced a decline in outsider revolts after 1895 when it began to professionalize its military, although it did experience a successful insurrection by an opposition presidential candidate in 1919 as well as a failed indigenous uprising in 1923–1924. The 1919 revolt resembled a coup in many respects, however, and its success was only made possible by the participation of military and police officers.

As we have seen, the poorest South American countries, namely Bolivia, Ecuador, and Paraguay, failed to develop strong militaries during the early twentieth century. Their armed forces remained small, politicized, poorly trained, and underequipped, and, partly as a result, these countries continued to be plagued by revolts.

Paraguay suffered the most revolts, experiencing seven elite rebellions and seven military coups between 1900 and 1929, several of which were successful. Overall, the number of revolt onsets and revolt-years more than tripled in Paraguay compared to the nineteenth century. The explanation for this reversal is straightforward: The Paraguayan military was destroyed in the War of the Triple Alliance (1864–1870). Whereas Paraguay had some 40,000 soldiers before the war and mobilized 70,000 troops at the height of hostilities, by the time occupation forces left in 1876, its army had declined to a mere 400 men (Kallsen Reference Kallsen1983, 33). The conflagration also affected the country’s territory and demographics – some historians estimate it lost half of its territory and up to 60–70 percent of its population (Whigham Reference Whigham2002; Whigham and Potthast Reference Whigham and Potthast1999). In the decades that followed, the country lacked the will and the resources to rebuild a severely factionalized military. At the outset of the 20th century, Paraguay still had the lowest level of exports in South America (Bértola and Ocampo 2012: 86). Not surprisingly, it also had the region’s smallest army, and its officers and troops often lacked even the most basic training and equipment. Paraguay did not take important steps to strengthen its military until the mid-1920s when a growing conflict with Bolivia prompted the Paraguayan government to purchase foreign weapons, reorganize its general staff, and hire first a French and then an Argentine military mission (Bareiro Spaini Reference Bareiro Spaini2008, 76–77; Lewis Reference Lewis1993, 142).

The Ecuadorian government, meanwhile, downsized its military considerably after its defeat in the Ecuadorian–Colombian War (1863). Only in the 1930s would Ecuador muster a force of 6,000 soldiers, equivalent to the one that preceded the 1863 conflict (Henderson Reference Henderson2008, 85). Ecuador undertook some efforts to professionalize its military at the turn of the century, hiring a Chilean military mission to train Ecuadorian officers – it also created some new military schools and began to send officers to Chile for training (Arancibia Clavel Reference Arancibia Clavel2002, 190–196). In addition, the Ecuadorian government made military service obligatory, enacted new laws governing promotions and salaries, and purchased military equipment from Chile as well as France and Germany (Moncayo Gallegos Reference Moncayo Gallegos1995, 155; Fitch Reference Fitch1977, 15; Arancibia Clavel Reference Arancibia Clavel2002, 212). Nevertheless, the reforms took a while to bear fruit, and Arancibia Clavel (Reference Arancibia Clavel2002, 267) and Romero y Cordero (Reference Romero y Cordero1991, 380–383) suggest that the long-term influence of the Chilean mission was relatively superficial. The Ecuadorian military remained highly politicized and senior Ecuadorian officers continued to be promoted, demoted, and discharged based on their personal and political affiliations (Fitch Reference Fitch1977, 16). Moreover, military budgets were reduced significantly between 1908 and 1913: The size of the standing army was slashed, and military salaries fell behind those of civilian employees (Fitch Reference Fitch1977, 16; Rodríguez Reference Rodríguez1985, 225). The weakness of the military encouraged the opposition to continue to carry out rebellions and some of these revolts were successful. Rebels overthrew the government in 1906 and 1911, and nearly did so again in the bloody 1911–1912 civil war. The military also had a very difficult time suppressing a rebellion that ravaged the province of Esmeraldas from 1913 to 1916.

Of the three small and poor South American countries, Bolivia took the most important steps to professionalize its military, hiring a small French mission and then a larger German one in the early twentieth century. With the assistance of these missions, the Bolivian government purchased foreign weaponry, created a military conscription system, overhauled the military schools and training system, and tried to establish a professional military career (Bieber Reference Bieber1994; Díaz Arguedas Reference Díaz Arguedas1971; Dunkerley Reference Dunkerley2003). These reforms initially appeared to work, and outsider revolts disappeared in the first two decades of the twentieth century. Nevertheless, the transformation of the Bolivian military was largely illusory: The country’s armed forces remained small, poorly trained, and heavily politicized. Outsider revolts resumed in the 1920s and the Bolivian military struggled to contain them. Indeed, an opposition revolt overthrew the government in 1920 and major indigenous rebellions destabilized the country in 1921 and 1927. Bolivia’s military deteriorated even further after the country’s stunning defeat in the 1932–1935 Chaco War, which led to further revolts, culminating in the 1952 Bolivian revolution.

Thus, the poorest South American countries made less progress in strengthening and professionalizing their armed forces. As a result, they remained highly politically unstable. By contrast, the other South American countries significantly strengthened their armed forces in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, which led to a sharp decline in outsider revolts and executive overthrows in these countries, as Table 3.3 indicates. Nevertheless, the professionalization of the military during this period did not lead to a reduction in insider revolts, such as military coups. Indeed, there were approximately six onsets of insider revolts per decade between 1900 and 1929, down only slightly from an average of seven per decade between 1830 and 1899. Many of these insider revolts succeeded in taking power, which encouraged military officers to continue to undertake them.

A Statistical Test of the Argument

To further explore the impact of military variables on the number of outsider revolts in a given country year, we carry out a statistical test using panel data from ten South American countries from 1830 to 1929. Because our outcome of interest is a count variable, we use a series of Poisson regressions with two-way fixed effects and clustered standard errors, following established procedures (Angrist and Pischke Reference Angrist and Pischke2009).

As Table 3.2 indicated, we measure military strength and professionalization using three variables: the number of military personnel (in thousands) from the Correlates of War Project (2020); the number of military academies from Toronto (Reference Toronto2017); and a measure of the degree to which appointment decisions in the armed forces are based on merit from V-Dem (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge2020). The coverage of these variables is limited for most countries between 1830 and 1845, resulting in an unbalanced panel. However, except for Uruguay, all countries enter the panel by 1854, and no observations drop due to attrition after a country enters the sample. When we include additional confounders in Models 2 and 3, we lose only fifteen additional observations.

Model 1 includes only the military variables, uses two-way fixed effects to control for time- and country-invariant confounders, and reports standard errors clustered by country. However, our military variables are related to other variables – such as economic growth and international conflict – which vary over time and across countries and could shape the likelihood of revolts. It is therefore key to control for these confounders, which we do in Model 2. Since export booms can affect the size and quality of the military, as well as the propensity of outsiders to rebel, we include a variable measuring total exports in current US dollars from Federico and Tena-Junguito (Reference Federico and Tena-Junguito2016). Relatedly, the expansion of railroads and telegraphs might have facilitated both economic growth and military recruitment, and increased the reach of state authorities, narrowing opportunities to rebel. We therefore account for the miles of railway track and telegraph lines in each country (Banks and Wilson Reference Banks and Wilson2014). To measure the potential impact of international conflict, we include a yearly count of the militarized interstate disputes each state was involved in (Palmer et al. Reference Palmer, McManus, D’Orazio, Kenwick, Karstens, Bloch, Dietrich, Kahn, Ritter and Soules2022), as well as a dummy variable capturing whether the country lost an international war in the past fifteen years (Schenoni Reference Schenoni2021). In addition, we include a series of controls that are common in the political violence literature. To control for the effect of hybrid regimes on political violence we use the Electoral Democracy Index (v2x_polyarchy) from V-Dem (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge2020) and its squared term. We also use an urbanization rate variable (e_miurbani) and the log of the population from Coppedge et al. (Reference Coppedge2020), since outsider revolts and many of the aforementioned variables (e.g., military size) would presumably be affected by socioeconomic modernization and population size. Finally, we include the years elapsed since independence – and drop year-fixed effects – in Model 3 to test if revolts declined simply as a function of time.

Unfortunately, the scarcity of data for nineteenth-century Latin America precludes controlling for other potential confounders. For example, there are no comprehensive time-series data on inequality or economic performance for this period. Nor are there reliable time-series data on the time-varying ethno-racial composition of South American countries or the relative strength of liberal and conservative parties during the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Nevertheless, we trust that our use of country-fixed effects should control for most of these unobservable characteristics that change slowly over time. The roughness of the terrain, which is also a prominent confounder in the civil war literature, is one of these time invariant factors. Similarly, we trust that our year-fixed effects will control for international shocks that affected all countries equally, such as global financial crises and changes in commodity prices. In Model 4 we make an exception and test the robustness of our results to an important remaining confounder, GDP per capita, which we measure using data in real 2011 dollars (cgdppc) from the Maddison Project (Bolt et al. Reference Bolt, Inklaar, de Jong and van Zanden2018). GDP per capita is perhaps the most significant predictor of political violence in the literature, but data on this variable are missing for numerous years, so Model 4 should be viewed with some caution.Footnote 19

Table 3.4 presents the results. In almost all models, the size of the military, the number of military academies, and the extent to which appointment decisions in the armed forces are meritocratic have a negative and statistically significant impact on the number of revolts in each year. The only exception is Model 4. When GDP per capita is included in the analysis, the number of military academies ceases to be significant, but this could be explained by the reduced number of observations in this model. Most of the other variables have the expected sign, but do not achieve statistical significance in any of our models. The minimal change in the r-squared statistics when confounders are included in Model 2 suggests that military variables explain most of the variance in the outcome. With observational data, endogeneity issues will inevitably remain a concern, but this should be taken as a strong indication that military strength might be mediating the impact of more structural geopolitical and economic variables. Further model specifications confirm this intuition. For example, when we drop all three military variables, one of the confounders, total exports, becomes significant (at p < 0.05). This suggests the effect of export booms runs through military strength.Footnote 20

Table 3.4 Determinants of outsider revolts in South America, 1830–1929 (Poisson regressions on number of revolts per year)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Military personnel (in 10,000) | −0.358Footnote * | −0.368Footnote * | −0.350Footnote * | −0.309Footnote * |

| (0.16) | (0.17) | (0.16) | (0.13) | |

| Number of military academies | −0.390Footnote * | −0.427Footnote * | −0.381Footnote * | −0.299Footnote ** |

| (0.16) | (0.21) | (0.18) | (0.09) | |

| Military appointments by skills and merit | −0.549Footnote * | −0.581Footnote ** | −0.336Footnote * | −0.395 |

| (0.23) | (0.23) | (0.16) | (0.32) | |

| Urbanization rate | −0.049 | 0.032 | −0.522 | |

| (0.56) | (0.47) | (0.55) | ||

| V-Dem Electoral Democracy Index | −0.466 | −0.320 | −0.534 | |

| (0.38) | (0.44) | (0.38) | ||

| V-Dem Electoral Democracy Index2 | 0.106 | 0.092 | 0.121 | |

| (0.09) | (0.10) | (0.10) | ||

| Militarized interstate disputes | 0.178 | 0.178 | 0.194 | |

| (0.17) | (0.16) | (0.16) | ||

| Defeat in international war (15-year period) | −0.106 | 0.166 | −0.137 | |

| (0.26) | (0.42) | (0.29) | ||

| Total exports | −0.178 | −0.666 | −0.150 | |

| (0.33) | (0.54) | (0.31) | ||

| Hundreds of miles of telegraph lines | 0.279 | 0.095 | 0.353 | |

| (0.21) | (0.23) | (0.24) | ||

| Hundreds of miles of railway track | −0.052 | 0.067 | −0.091 | |

| (0.12) | (0.15) | (0.13) | ||

| Population (log) | −0.005 | 0.008 | 0.060 | |

| (0.09) | (0.08) | (0.11) | ||

| Years since Independence | −0.010 | |||

| (0.01) | ||||

| GDP per capita | −0.000 | |||

| (0.00) | ||||

| Constant | −3.761 | −1.317 | 12.938 | −7.160 |

| (6.34) | (13.99) | (6.96) | (8.62) | |

| Pseudo r-squared | 0.2252 | 0.2344 | 0.1371 | 0.2540 |

| Fixed effects | Two-way | Two-way | Country | Two-way |

| Standard errors | Clustered | Clustered | Clustered | Clustered |

| No. of observations | 800 | 775 | 775 | 695 |

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. Country and year dummies not shown.

* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

Overall, this statistical analysis of the determinants of revolts in South America between 1830 and 1929 provides support for the argument that military size and professionalization reduced the prevalence of outsider revolts. Military strength does not have an impact on the likelihood of insider revolts such as coups and mutinies, however. As expected, when we switch the dependent variable from major outsider revolts to major insider revolts, such as coups, the military variables lose statistical significance in most of the models. Although military strength effectively deterred regime outsiders from mounting rebellions in South America pre-1930, it clearly did not have the same impact on regime insiders.

Conclusion

This chapter shows that the expansion and professionalization of the military significantly reduced revolts by political outsiders in the region. The importance of this decline is clear: It vastly reduced the number of lives lost to violence, brought greater political stability to the region, and helped pave the way for a lengthy period of economic growth and state building. As we shall see, military professionalization also laid the groundwork for the first wave of democratization in the region by encouraging opposition parties to abandon the armed struggle and focus on the electoral path to power.