Premarital sex was a criminal offence in eighteenth-century Sweden, and young unmarried women were expected to guard their chastity.Footnote 1 The households that housed these unmarried people, who were often in positions of service, allowed for few private spaces. This was especially the case in the cities. Shared rooms, even shared beds, were the norm.Footnote 2 Yet, a growing number of people still met, courted and had intercourse before marriage.Footnote 3 Where in the city did these unmarried people meet for intimacy and sex?Footnote 4

The Swedish countryside had a long tradition of nattfrieri, a popular custom that allowed female domestic servants to sleep in the outbuildings away from the main farm building. Here courting young men visited and stayed the night – theoretically the couple remained completely chaste, with their clothes on and sleeping on top of the covers. But this was primarily a rural custom, prosecuted by the church and, by some reports, in decline by the eighteenth century.Footnote 5 Meanwhile, in the eighteenth century new arenas for courtship emerged in the city in the form of public dances and informal parties on the city’s outskirts. These developments were coupled with growing concerns around increasing sexual depravity among rich and poor alike.Footnote 6 Were these concerns signs of new emergent areas for courtship and sex in the early modern cities?

In this article, we use a dataset of baptismal records of illegitimate children from mid-eighteenth-century Stockholm where not only the birth, but also the place of the children’s conception is recorded. Through these records, we can provide a broad overview of the places in the city where unmarried, and probably also soon-to-be-married, people could meet for illicit sex.

We show that people, somewhat counter-intuitively, did not seek seclusion and privacy either outside of the city or on its outskirts, but rather that illicit sexual activity took place towards the city centre. We also reveal the importance of the household and workplace as a meeting place for courtship and sex, as well as the difficulty in discerning any clear emergent areas for sexual activity or any new sexual institutions such as brothels in the early modern city.

Illicit sex

Premarital sex was a criminal offence in eighteenth-century Sweden, but times were slowly changing. During the seventeenth century, legislation on sexual matters from both church and state had become increasingly repressive. In 1686, church law stated that fornicators had to stand on a special stool of repentance during the sermon, awaiting public reconciliation with the parish, which was seen as highly stigmatizing. By the 1741, this practice was abolished and instead fornicators could go through the ceremony of re-entering the congregation in private.Footnote 7

The civil code of 1734 likewise outlawed fornication (lönskaläge). Any man who had slept with a woman without being married to her was made to pay 10 riksdaler, while the woman paid five riksdaler. Anyone who could not pay would be committed to prison on a diet of bread and water.Footnote 8 If the perpetrator chose instead to marry the woman, the fines would be reduced to two riksdaler, offered to the church. The legislation was therefore geared towards guiding perpetrators to formal marriage. In practice, physical intimacy and even sex were tolerated once a couple was betrothed.Footnote 9

The eighteenth century saw an increase in illegitimate births. Some have argued that when laws were liberalized, men were less likely to take responsibility for their sexual liaisons, resulting in an increase of illegitimate births.Footnote 10 Others have argued that urbanization and proletarianization were the driving causes of the labouring poor avoiding marriage and instead opting for more informal cohabitation in the city.Footnote 11 Some of these illegitimate births might also be understood as births that took place before a marriage, reflecting common premarital sexual practices whereby the mother and father would eventually marry; they might also perhaps have been the results of failed courtships.Footnote 12

Courtship and meeting places

Where and how could singles meet? The Swedish rural custom of nattfrieri has been traced back to the seventeenth century, when the custom was already reportedly widespread. The practice strongly resembled courtship customs popular throughout Europe, in which young men visited women in their homes, often sitting by their bedsides.Footnote 13 Sometimes young men would – more or less secretively – climb in through the window to visit the women they were courting. In other cases, they might stay up talking and then make the excuse that the hour was late, they were far from home and ask to stay the night.Footnote 14

These customs, which often prevailed until the nineteenth or twentieth century, were recorded by folklorists in Sweden and beyond, who often described them as essentially chaste.Footnote 15 One account of ‘bundling’ describes the practice as taking place between a couple who had been courting with serious intent for some time. The man could visit the woman and sleep with her in her bed, sometimes tucked in by her parents, and they would be separated by a plank or cloth to prevent any sexual activity.Footnote 16 The Swedish version is recorded as having been more open, with less strict parental control. However, the chastity of this custom is underscored – men and women only talked, and lay on the bed with their clothes on, never under the blankets.Footnote 17

There are reasons to suspect that these prevailing customs, which were recorded, described, named and probably subtly systematized in the nineteenth century, differed from the customs of earlier centuries. The historical evidence for them remains elusive, often limited to the rare mention, allusion or complaint.Footnote 18 The earliest observations of the Swedish nattfrieri can be found as far back as the seventeenth century, when the custom seems already to have been quite widespread. It was not seen as chaste or proper by local clergy, who did their best to discourage the custom with condemnation and fines. Neither was it deemed appropriate to be seen courting on Saturday night before Sunday mass, and there was concern that the custom would lead to a rise in promiscuity and illegitimate children.Footnote 19 These clerical efforts were not in vain, at least not according to one priest in Dalarna, who reported that the custom had become extinct by the mid-eighteenth century.Footnote 20 Though he might have overstated the case a little, it is plausible that the custom was in decline by the mid-eighteenth century. We therefore argue that there is a strong possibility that these customs might have had long early modern roots, but that their structure and norms might have differed from the rigidly chaste customs recorded in the nineteenth century. The recorded customs do, however, share important characteristics and some tendencies of a shared north-western custom of early modern courtship: single people met in the vicinity of a household overnight, with the parents’ implicit or explicit knowledge, which provided an opportunity for privacy and intimacy between a couple. In addition, some argue that these courtship customs lacked any sexual stigma, and that one young woman could be courted by several suitors.Footnote 21

Urban space

If single people could meet in the outbuildings around the farmstead in rural areas, where could they meet in an early modern city? Kirsi Ojala, studying domestic servants in eighteenth-century Turku and Odense, observes how single people met and talked in public, under the implicit supervision of the local community and their household.Footnote 22 Julie Hardwick, studying early modern Lyon, observes how most couples met through work, and took romantic walks together around the city and out into the surrounding countryside. However, by the eighteenth century, formal gatherings such as dances started to play a larger role in courtship.Footnote 23 In eighteenth-century Stockholm, Rebecka Lennartsson observes something similar. While the seventeenth-century tavern was a space reserved for homosocial male drinking, the eighteenth century seems to have seen a rise in krogbaler or pub-balls. These were simple gatherings that took place in and around public houses, where men and women met, drank and danced together.Footnote 24 Other such gatherings could be used as thinly veiled venues for the sex trade, where customers pretended to be suitors and the women pretended to be domestic servants.Footnote 25

While Lennartsson describes the Stockholm eighteenth-century sex trade as informally organized, Marion Pluskota, mapping prostitution in the eighteenth-century port cities of Bristol and Nantes, notes that the sex trade centred on neighbourhoods close to customers such as the harbour and middle class areas that were still able to provide affordable lodgings for the prostitutes themselves.Footnote 26

Viewing late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Stockholm through the lens of its police, Tobias Osvald discusses the contested areas of the city, noting that the early modern city was filled with sheds, fences, gates and yards: spaces that blurred the line between someone’s household and a public place. These areas proved difficult for the police to govern and control. In time, as the households became smaller and more clearly defined and drinking establishments were distinguished from private homes, a less porous urban geography appeared.Footnote 27

As Stockholm grew, as the number of children born out of wedlock increased, as new arenas for courtship emerged and as the sex trade increased, where did people turn for sex? Were there specific areas where illicit sex was more likely to take place? Were there any types of places that were used more often, or any neighbourhoods that can be linked to an emergent sex trade in the city?

These questions will be answered through examining a database built on the places of conception noted in the parish records of baptisms of illegitimate children. After presenting our findings, the article gives an overview of the most likely places for fornication throughout the city, followed by a discussion of different methods of courtship within the workplace. The last section discusses the evidence of sex trade in mid-eighteenth-century Stockholm.

The dataset and sources

From 1686 onwards, each Swedish parish had to keep records of every baptised child, noting its name, its parents and godparents.Footnote 28 Normally, these records were divided between legitimate children and children born out of wedlock. In some parishes, priests not only recorded the parents and godparents of these illegitimate children, but also took note of where the child had been conceived, who the alleged father was and where the mother had given birth. The results read almost like short stories:

The 6th of February 1738, an Illegitimate child was baptised and called Henning, his mother, who said she was born in Österhaninge parish, called Maria Johansdotter, said the present coachman Henning Walt was the father of the child. The fornication was said to have taken place on Norrmalm at the red sheds at chancellor count Ture Bielkes house, where they both had been in service together.Footnote 29

The dataset used in this study derives from 270 of these baptismal certificates from two parishes in Stockholm – Maria Magdalena and Katarina – from the years 1738–39 and 1764–65. Through these baptismal records, we will be able to provide an overview of where, when and under what circumstances single people met for intimacy and sex in early modern Stockholm.

While baptismal records were kept for all children, the records of illegitimate children also served as a tool for policing illicit sexuality: once the child was baptised, the priest would send the information relating to the parents’ names and the place of conception to the lower city courts and the cathedral chapter. It is, of course, possible that the mothers were not always completely truthful in their accounts of where the child had been conceived. We have worked on the assumption that the statements given to the priest reflect something that would be, if not true, then at least probable, perhaps even something that might have been seen as somewhat respectable given the circumstances.

The period under investigation precedes the time of rapid population increase and also the radical increase in numbers of illegitimate children from the end of the eighteenth century, continuing into the nineteenth century.Footnote 30 However, even by the mid-eighteenth century, recorded illegitimate births represent a large proportion of total births. During the eighteenth century, Stockholm experienced slow but continuous growth, from an estimated population of about 55,000 in the late 1730s to close to 70,000 in the late 1760s.Footnote 31 In the years 1738–39, the parishes on Södermalm recorded 945 legitimate and 108 illegitimate births. By 1764–65 the records show an increase to 1,349 legitimate and 162 illegitimate births.Footnote 32 The illegitimate births recorded for this dataset thus account for around one-tenth of all children born.

Both parishes in the study were located on the large island of Södermalm (Figure 1), south of the then city centre. Maria Magdalena parish, on the western side of the island, contained both urban affluent households close to the city island, as well as poorer neighbourhoods and larger manor houses in the south, where the city gradually transitioned into rurality. Katarina, located on the eastern side of the island, was considerably poorer, and its population was dominated by small households of sailors, labourers and seamstresses.Footnote 33

Figure 1. Map of Stockholm, marking its districts, 1751. Source: SSA, kartsamling NS 442, Charta Öfwer Stockholm Med des Malmar och Förstäder, Georg Biurman 1751.

The choice of period and parishes reflects the limitations of the sources. Not all parishes recorded the place of conception, and the records from 1738 are the oldest possible for Maria Magdalena parish, while from the mid-1760s it seems to have become increasingly uncommon for the priest in either parish to note down the place of conception.Footnote 34 The records from both parishes differ in some details. For example, in Maria Magdalena in the 1730s, the priest recorded whether the father of the child was present or not at the baptism. This was not recorded in Katarina; instead the priest included in what household the mother had given birth to the child. In other words, while the practice of noting the place of conception was connected to legal practices, each parish had its own rules regarding which details should be included in the records.

In some instances, we have traced the baptismal records to other sources. Sex outside of marriage was not legal and, as we have seen, when an illegitimate child was baptised, the local courts (kämnärsrätten) were notified, as well as the cathedral chapter. In some cases, the records of these proceedings contain valuable contextual information that expands upon the brief notations of the baptismal records. However, most records in the courts add little of substance.

The dataset captures a wide variety of relationships, although it skews towards the labouring lower strata of the city. The title of the fathers of the illegitimate children was usually recorded, which hints at their social standing or profession.Footnote 35 A large proportion of the fathers in the dataset were quite proletarian:Footnote 36 55 (20 per cent) of them were journeymen, 50 (18 per cent) had the title of servant (dräng) or one associated with unskilled labour, 28 (10 per cent) were sailors and 29 (11 per cent) were soldiers or low level non-commissioned officers.Footnote 37 However, the dataset also contains fathers from the middling professions and those from the higher strata as well. Several craftsmen, merchants, skippers and students appear in the records, as well as higher officers and even two barons.Footnote 38

Were these illegitimate children the result of betrothed couples having sex before their union was sacralized in church? In seven cases, the mother reported that a promise of marriage had been made at the time the child was conceived.Footnote 39 These claims could possibly have been made to protect the mothers’ reputations, but might very well have been directed at the father, to ensure that the promise of marriage could now be fulfilled, since the union had been consummated, or that the father would have to take responsibility for his illegitimate offspring.Footnote 40 In five further cases, sexual intercourse was said to have taken place while the couple was formally betrothed.Footnote 41 One child was born to parents who were not only engaged, but whose banns had already been read twice in church and were presumably soon to be wed.Footnote 42 The parents, a coachman and his fiancée, must have decided to have the banns read when the pregnancy was already well under way.

During the first part of the study, 1738–39, the majority of the fathers (who were still alive) were recorded as being present at the baptism in the records of Maria Magdalena. Of 53 baptisms, the father was present in 28 of them; in four of them the father was reported as being dead; in another four, the presence of the father is unclear; and in 17 he was recorded as being absent.Footnote 43

Some of the baptised illegitimate children were not a result of sexual encounters that took place in the city, but were born to mothers who had moved to the city while pregnant. Seven of the children born in Maria Magdalena were conceived beyond the city limits. In Katarina, five children were a product of a sexual encounter that occurred outside the city in 1738–39, while 23 children had been conceived outside of Stockholm but were born in Katarina in the period 1764–65.Footnote 44 The fathers could be high-born, such as the Baron Wrangel, who had impregnated one Lisa Berg on an estate outside of Stockholm. Others were army captains, lieutenants and master artisans.Footnote 45 Many were also from the lower strata: journeymen, servants, farmhands and sailors.Footnote 46 We assume that these fathers were not in a position to marry, or perhaps they were just not willing to do so. Whatever the case, the single mothers might have been drawn to Stockholm, and especially Katarina, in the 1760s by the opportunity to make a living either through spinning in the manufactories or by participating in the city’s informal economy.Footnote 47

In conclusion, the dataset captures all kinds of premarital and extramarital relations that led to the birth of a child: some mothers who gave birth came to the city alone, one imagines, almost like fugitives. Others baptised their child together with their betrothed in church. Most of the couples can be said to have belonged to the labouring poor of the city. The dataset is thus fairly representative of the relationships of the majority in early modern Stockholm.

Where they met

In theory Stockholm offered many opportunities for outdoor courtship, especially in the southern districts on Södermalm. Located on an island just south of the city centre, it was only partially inhabited. Dominated by larger mansions, gardens and greenery, it was perfectly situated for outdoor courtship, for romantic walks in the countryside, and offered seclusion from prying eyes. Yet, none of the mothers mentioned any of these possible outdoor areas as the place of conception of their child. Depending on how the records are interpreted, one might even argue that there was no mention of sexual activity outdoors at all.

The baptismal records can be vague at times in their description of places of conception. Some are simply inexact, especially in the 35 cases of baptisms where the child had been conceived far from the city, where only the father’s name and the parish, county or village was noted.

In 16 cases, the locations were noted in a less precise manner, which might indicate an outdoor rendezvous in the streets. The mother of one child was recorded as having had sex with a merchant in an alley in the city,Footnote 48 and a woman and a manservant reportedly had intercourse at the intersection of Hornsgatan and Hornskroken streets.Footnote 49 Another manservant had sex with a woman ‘in the city, on the street lilla Ugglegatan’Footnote 50 and one overseer had had sex with a woman in ‘little Maria alley’.Footnote 51

In a further 39 baptisms, the child was said to have been conceived in someone’s gård, which can refer to a yard, a farm or a larger building, with connected outdoor facilities such as gardens and yards. It is not always possible to know if this term was meant to suggest that intercourse happened in the yard, or simply at a property large enough to be designated as a gård. In one instance, it seems clear that it was the yard itself that had been used for sex: Anna Falander said that she had had intercourse with a clerk at ‘the church wall over the church, in the widow Maria Bergs yard (gård)’.Footnote 52 These yards constituted exactly those open house buildings that blurred the line between pubic and private, hidden and open, governable and ungovernable.Footnote 53

In most cases that included someone’s gård – 201 out of 270 – the statements in the records were formulated in such a way that it can be understood that the sexual act could be connected to someone’s home. One woman, for example, stated that the child had been conceived ‘within the city, on Lilla Nygatan at the wigmaker Mandelberg’,Footnote 54 while another gave the location as ‘at merchant captain Ahlström at Hornsgatan’.Footnote 55 The overall impression from the material is that exclusively outdoor environments were rare, almost non-existent, as places for sexual activity. Maybe outdoor encounters were considered to show promiscuous behaviour, and mothers therefore chose to suggest more respectable locations for the conception of their babies. It is possible, but even so, that interpretation would still imply that parks, gardens, woods and alleys were seen as disreputable environments for courtship and sex.

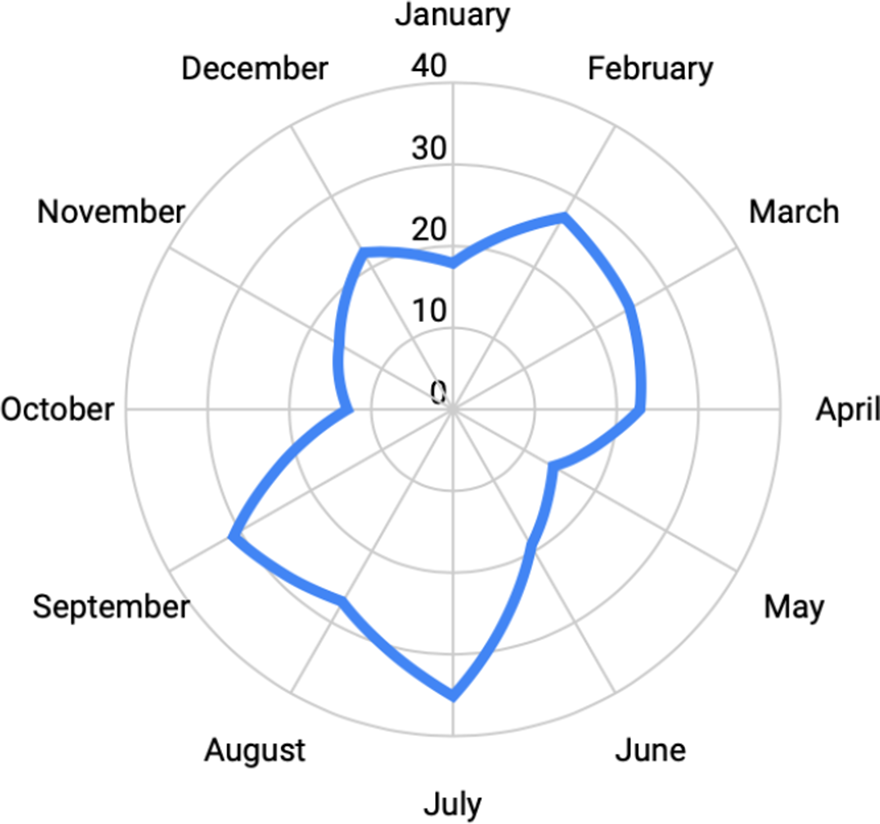

The baptismal dates of the illegitimate children provide further evidence to suggest that sexual encounters outdoors were rare. Stockholm can be lovely in the summer, but in other seasons the city can be cold, wet and windy, hardly the kind of weather to encourage courtship outdoors. This would have been even more the case in a century without electric lights during the long dark hours of the winter. So, if people met for flirting and sex in the outdoors, the likelihood is that more babies would have been conceived in the summer months than in the winter. Were there?

The 270 baptisms in the database were spread quite evenly through the months of the year (Figure 2). Some patterns can be discerned, but none are strong enough to indicate a clear connection between the seasons and sexual activity. Counting nine months backwards,Footnote 56 to calculate an approximate month of conception, we see that there is indeed a slight pattern: the most prevalent months are July (35 instances), August (27) and September (31), and sexual activity seems to have tapered off in the autumn, with October (13) and November (16) as the low point, picking up again during winter and spring, with December (22), January (18), February (27), March (25) and April (23) seeing nearly as much sexual activity as the summer and autumn, followed by May (14) and June (19).Footnote 57 With high points in late summer to early autumn and late winter to early spring, it is clear that if sexual activity had a seasonal pattern, it was definitely not because of the weather. There may be a correspondence to access to food, during harvest in autumn and the slaughtering of cattle in winter. It could also, more likely, be that variations in the data should be primarily attributed to chance due to the small sample size. Whatever the reason, the data do not suggest any obvious seasonal pattern in sexual activity. Further, this suggests that sexual activity was not dependent on available outdoor spaces.

Figure 2. Approximate month of conception of illegitimate children in eighteenth-century Stockholm. Source: SSA, Katarina, Födelse och dopböcker över oäkta barn, vols. 1 and 3; and SSA, Maria, Dopböcker för oäkta barn, vols. 1 and 2.

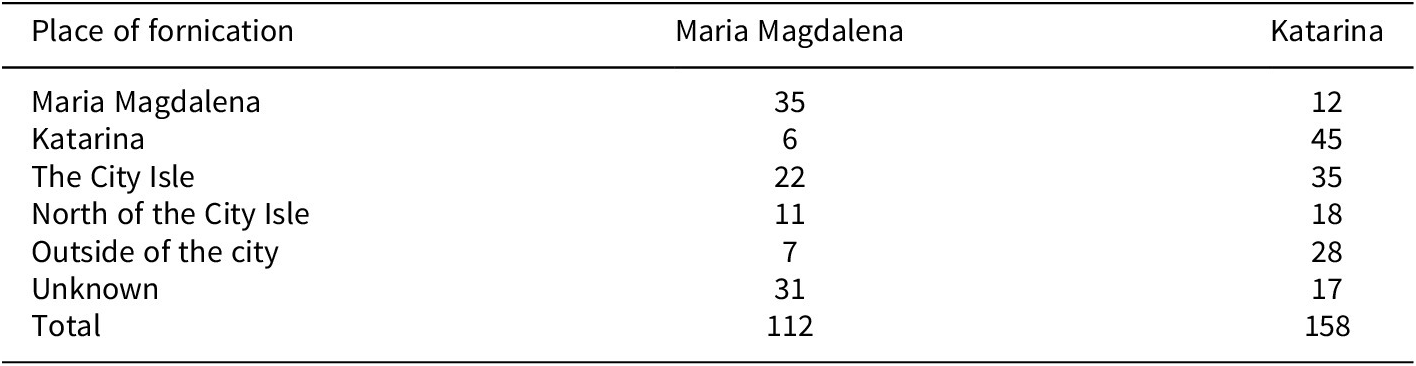

The baptismal records also enable a general overview of the geographic spread of the sexual encounters. Pinpointing precise addresses has not been possible, but Table 1 shows the spread of sexual encounters throughout the districts of the city.

Table 1. Places of fornication mentioned in baptismal records, 1738–39 and 1764–65. Source: SSA, Katarina, Födelse och dopböcker över oäkta barn, vols. 1 and 3; and SSA, Maria, Dopböcker för oäkta barn, vols. 1 and 2

Most of the children born in Maria Magdalena or Katarina were conceived in the same parish as that in which they were baptised. The second most common district was the city island itself, which is not surprising since this was the most densely populated part of the city. What is surprising, however, is how uncommon it was for mothers to cross the parish lines on Södermalm. Only six of the illegitimate children born in Maria had been conceived in Katarina, and only 12 of the children born in Katarina had been the result of a sexual encounter in Maria. The mothers in Maria Magdalena and Katarina were more likely to walk to the city island, and continue north of it, than they were to meet someone from across Södermalm. Why was that?

The city island, together with the northern part of Stockholm, were the areas with the most expensive real estate, with the largest palaces and with the highest proportion of domestic servants registered in the city.Footnote 58 Their prevalence in the sources can therefore have two explanations: one is that many of the mothers of illegitimate children lived on Södermalm, but were employed in the central and northern part of the city – perhaps by peddling wares or by working as live-out domestic servants – and that it was in this context that they had courted and conceived a child. Another explanation is that they had previously lived in the northern part of the city, but had to leave their employment when they became pregnant and move to the poorer Södermalm.

In summary, couples could perhaps find shelter and privacy in small alleyways, in outbuildings connected to the larger manor houses, in the shrubberies of a garden or in other outdoor spaces in the city. However, the data shows that courtship and sex were not dependent on these outdoor environments. Sexual activity was closely tied to built-up environments in the city; sex was not something that was sought and found outside of it. Further, the data on mobility throughout the city suggest that sexual encounters were somehow tied to the workplace.

The household and the workplace

In April 1738, a woman named Anna Nilsdotter gave birth to a daughter, christened Anna Helena. The child must have been conceived sometime around July, in the summer of 1737. Anna said that the father was the customs officer (besökaren) Anders Ek, who was present at the baptism. She said that they had conceived the child in a baker’s stall on the eastern quay in the city (Skeppsbron). Was the baker’s stall just a convenient location for an impromptu meeting as they happened to pass by? Or was it perhaps the stall where Anna worked, selling bread when Anders passed by, inspecting the cargo of ships on the quay?Footnote 59 In another instance, one Anna Häll admitted having conceived her child with the butcher boy, Jockom, at the abattoir.Footnote 60 The workplace was a convenient meeting place, which could also provide some seclusion to a courting couple. Hardwick notes that the workplace could function as a community safeguard: it provided a meeting space, but also social control.Footnote 61

People did, and do, spend a lot of time at work. It is only natural that the workplace was a recurring meeting place. Meeting at work in the early modern city could encompass several things: it might have meant meeting while doing work somewhere in the city or that the mother and father lived and worked together in the same household. For the latter, in the first years of the study, in Maria Magdalena parish, the priest would sometimes notice if the couple had met in the same place of service: in 10 out of 53 baptisms the child had parents who worked in the same household. Co-working might have provided opportunities to get to know each other in a relatively safe environment, where the woman’s virtue could not be called into question. Since servants could change households periodically, service not only provided opportunities for networking in general, but for dating and courtship in particular. In all but one of these 10 cases, the father was also present at the baptism. The exception was Anna Margareta, who had given birth to a little girl, also baptised Anna Margareta. She said that the father of the child was Jonas Loos, a carpenter apprentice, and that they had slept with each other while serving in the same household. However, it seems likely that Anna Margareta then left the household and gave birth somewhere else.Footnote 62

Although during the later periods of investigation, and for the entire period in Katarina parish, no special note was taken if the couple had met when they served together, the place of conception can still be tied to the home or workplace in almost a fifth of the baptismal records – in 57 cases out of a total 270.Footnote 63 In some instances, the place of work could have been outside the household, such as a market stall. The household itself could also be used in several ways for more – or less – accepted forms of intimacy and sex.

One case, where the woman’s claim of paternity was questioned, gives several examples of how courtship could have been conducted from the household.Footnote 64 One Maria Elisabet Walberg from the lower town court on Södermalm said that the servant Raphael had promised to marry her, and had intercourse with her in the spring of 1737. At the time she was serving at the baker, Lund, and Raphael had visited with his master. The servant denied it, and Maria Elisabet had no proof that he had promised to marry her. She could only prove, through witnesses, that Raphael had come and talked to her a couple of times after she had left the service of the baker to work for a porter. The baker and his mistress themselves testified to not having noticed anything suspicious between Raphael and Maria Elisabet. However, witnesses described Maria Elisabet as having led a quite promiscuous life during her period of service at the baker. In the winter months, between Christmas and Easter, witnesses claimed that Maria Elisabet had been running around in the night, several times climbing over the fence and through the window of Lund’s house. Others testified that she was accustomed to having male visitors, late at night. One of them, the journeyman Jacob Hagman, had slept with Maria Elisabet previously, and had been found by his master and mistress ‘late at night, in a quite intimate circumstance’.Footnote 65

The short report contains details of several opportunities and strategies for courtship in an early modern household. For one, Maria Elisabet said she had met, received a promise to marry and had sex with Raphael when he and his master had visited her master, presumably in the course of a couple of nights. Close co-sleeping arrangements, and extended periods during which guests and their servants intermingled with household staff, surely provided opportunity for courtship, intimacy and maybe even sexual encounters. Another mode of courtship was when Raphael came to visit Maria Elisabet, to talk to her, in her new place of service at the porter’s. Both had the advantages of being supervised by the master of the household: the master’s supervision lessened the risk of being accused of any wrongdoing, of having one’s reputation called into question or of having to take care of an illegitimate child. The master of the household could provide accountability. The most suspect form of courtship Maria Elisabet was involved in was the secrecy of it all. The running around at night, and the climbing in and out of the window. Where had she been? To the journeyman Hagman? Wherever it was, it could not have been honourable, since it was done in secret under cover of darkness. The witnesses against Maria Elisabet underscore one of the patterns observed throughout the dataset – secrecy and seclusion seem to have been avoided in favour of environments that provided some accountability.

Hitherto, we have focused on voluntary meetings within the household. Some relationships were likely to have been more coercive. There were many opportunities for masters to sexually abuse maidservants within their household as well, and indeed many entries in the baptismal records give the impression that there had been a relationship with the employer, or other persons of authority in the household, and that the mother had to leave and bear the consequences of the liaison. One of them was Anna Greta, who gave birth to a child in the house of a journeyman in Katarina parish on Södermalm. She claimed that the father was Baron Knorring, who had had sex with her at Drottninggatan on Norrmalm.Footnote 66 Another woman, Anna Maria Hökenstedt, said she had had sex with a student in Uppsala in the house of a professor, but had given birth to the child on Södermalm.Footnote 67 Ultimately, the nature of these relationships rely on guesswork. What can be said here is that they happened, quite frequently, and the fathers may not have been present for the baptism of their illegitimate offspring.

In conclusion, the household and workplace provided several opportunities for intimacy and sex: they could both provide semi-secluded spaces for intimacy, but also be used for illicit meetings between couples at night, or enable abusive masters to take advantage of their servants. In all cases, these places were used in an ad hoc manner, creating temporary seclusion and pockets of privacy.

Ahlström and the Stockholm sex trade

Rebecka Lennartsson argues in her study of the emergent sex trade in eighteenth-century Stockholm that the ‘geography of sin’ was still fluid in the city: the nightlife moved between the city’s outskirts, public environments and improvised meeting places. While inns, taverns and theatres might have had a reputation for promoting loose morals and promiscuity, the really suspicious places were the secluded rooms, behind locked doors, where people could let the mask of public decency slip. The public woman was, in a manner, not yet public.Footnote 68 Therefore, Lennartsson argues that the sex trade in Stockholm was more connected to individuals than specific places. Is there any evidence of this sex trade in our database of illegitimate births?

One recurring name in the records of illegitimate children is the merchant captain Magnus Ahlström. Between April of 1764 and December of 1765 Ahlström’s properties on Södermalm are mentioned no less than eight times.Footnote 69 Captain Ahlström was a notorious procurer in eighteenth-century Stockholm. His brothel Ahlströms Jungfrubur on Baggensgatan 23 in central Stockholm was said to contain ‘nymphs’ over three floors and was immortalized in eighteenth-century songs. When the diet assembled in Gävle, instead of Stockholm as was the custom, it was rumoured that Ahlström had supplied his noble customers with a delegation of no fewer than 60 prostitutes.Footnote 70 However, looking at the poll tax registers, there are no signs of any prostitution taking place at the address: in 1765 the property housed a couple of widows, one tobacco worker, a clerk, a porter, a domestic servant and a journeyman.Footnote 71 Lennartsson concludes that the notorious address on Baggensgatan contained no more suspicious tenants than any other address in the city.Footnote 72

However, prostitution was often conducted informally in people’s homes, embedded in social codes of decency. In his erotic memoirs, Gustav Hallenstierna remembered a visit to the brothel of Lovisa von Plat in Stockholm sometime in the 1760s. After dinner, he and a friend took a coach to the northern outskirts of the city, to visit two ladies. When they entered, they were shown into a room, where the ladies were waiting for them. The room was shabby, they were dressed in negligees and Hallenstierna was surprised to be visiting ladies without any male company. They sat down, started talking, drinking and flirting. The older of the women began to complain how her husband had gambled away all their money and implied the sum that they needed. Hallenstierna’s friend said that he could lend her the sum. Once the payment had been made, the women fetched more wine and now appeared ‘merry and willing’.Footnote 73 Although to the participants, the purpose of the visit was clear, they still maintained a thinly veiled façade of two men visiting and helping a woman in distress in her home. This façade might have been transparent to the eighteenth-century Stockholmers, but provides a challenge for historians today. Can the birth records of illegitimate births be used to unveil an eighteenth-century sex trade? Recurring names and places could be a hint of some institutionalized sexual activity.

Captain Magnus Ahlström did indeed own several properties in and around Stockholm and might have supported himself in part as a landlord. While the address at Baggensgatan is not mentioned in the dataset, three of his properties were in Maria, in the Rosendal quarter by Hornsgatan, and it was here that all the eight incidents of sexual intercourse connected with Ahlström’s properties took place. Can this concentration of sexual encounters in one single block in the city be taken as a sign of a brothel?

In some of the cases, Ahlström’s houses were the places where women could be found after they had given birth. Anna Christina Wahlberg, for example, was born in Katarina on Södermalm, and had met and slept with a clerk at his house in the same parish. After having her child, the priest noted that she could be found in one of Ahlström’s properties.Footnote 74 Was Anna Christina in Ahlström’s employ, and was the clerk in Katarina her customer? It is of course possible. In another case the mother, Maria Scherin, housed at one of Ahlström’s properties, said she became pregnant in Turku, Finland, after relations with a learned man there.Footnote 75 It is possible that both women had, perhaps during their service as domestic servants, had sex with their masters and had to leave their household when it became apparent that they were pregnant. Another two of the cases recorded in Ahlström’s properties were between long-established couples. One couple – the coachman Nils Hellström and Christina Berg – had already had the banns read twice in church in preparation for marriage;Footnote 76 the other was a soldier and his fiancée.Footnote 77

All in all, Ahlström may very well have been engaged in the sex trade of early modern Stockholm, but the evidence provided by the baptismal records provides no conclusive proof of it. The eight illegitimate children who can be traced to his properties on Södermalm in some ways had little in common except for the humble background of their parents: one father was a sailor, another a soldier, a third a journeyman.Footnote 78 Ahlström seems to have been a landlord for the poor rather than anything else, even if nothing can be ruled out, given his notoriety as a procurer in the city. What can be said is that the dataset provides no evidence of a brothel.

Conclusions

The baptismal records of the parishes of Södermalm give us a broad overview of sexual relations among mostly the working poor of eighteenth-century Stockholm. The 270 baptismal records in the database are dominated by fathers who were journeymen, sailors and labourers, interspersed with some noblemen, clerks and artisans who might have fathered an illegitimate child with their domestic servant. These people rarely had much private space in the city, so where did they meet and how did the city shape their relationships?

Our main findings are that, despite an increase in illicit sexual activity, Stockholm was still a city characterized by porous boundaries, with no obvious new areas emerging for sexual activity. Single people still met in houses, in households, while working together or running errands, climbing through windows at night or maybe, sometimes, finding places of seclusion in alleyways or behind a fence in the yard.

We have found that a majority of mothers said that they had conceived their child in someone’s household, or in a place connected to it, and there is reason to believe that these households were often tied to the workplace of either the mother or the father. Similar to the ethnological records of nattfrieri, there is evidence of single people having met in the household, or in outbuildings close to the household. To what extent these meetings were the equivalent of the bundling and nattfrieri customs recorded elsewhere is not possible to determine from this source material. We do, however, believe that this underlines that in the middle of the eighteenth century, Stockholm was still a city characterized by blurred lines between households and public space, where single people could find and use nooks and crannies, corridors and rooms, yards and alleys in an ad hoc manner to establish pockets of privacy for illicit sex.Footnote 79

The parks and dances on the city outskirts that could have been plausible arenas for courtship, intimacy and sex are not visible at all in the baptismal records. Rather than taking place out of the city, intimacy and sex seem to have been found mostly within the city. Pluskota notes, in chronicling the emergence of red-light districts in eighteenth-century towns, how the sex trade coalesced around central yet affordable districts near the city ports. While we have not found any convincing evidence of the sex trade in our source material, the sexual activity apparent in the baptismal records of illegitimate children still took place in the same central, dockside areas as those Pluskota studied.Footnote 80

Competing interests

The authors declare none.