Introduction

Citations of scientific journal articles are often used as a measure of both scholarly attention and scientific impact. Across disciplines (Aksnes et al. Reference Aksnes, Rorstad, Piro and Sivertsen2011; Ferber and Brün Reference Ferber and Brün2011), including political science (Maliniak et al. Reference Maliniak, Powers and Walter2013; Dion et al. Reference Dion, Sumner and Mitchell2018), there is evidence indicating the presence of a gender citation gap between articles authored by women and men.Footnote 1 The gender citation gap is defined by research of men being more frequently cited, on average, than comparable research authored by women. The gender citation gap represents an imbalance in the journal publishing domain that is likely to be perpetuated as it contributes to gender imbalances in hiring, promotion and funding decisions (van den Besselaar and Sandström Reference van den Besselaar and Sandström2016).Footnote 2 The central role of journals could allow them to serve as a hub for addressing biases in citation behavior and gender imbalances more generally. This could be achieved through different means, such as editors asking reviewers to pay attention to gender imbalances in the citations of manuscripts; alerting authors of manuscripts to the gap and asking them to go through their references; the use of a gender balance assessment tool for accepted authors, and encouragement to increase the share of citations of articles by women (Sumner Reference Sumner2018).

In this paper, we review the submission guidelines of 102 journals from the field of political science.Footnote 3 The review is guided by a descriptive research question: How many journals address gender imbalances in citations in their guidelines? The collection and analysis of journal policies with a focus on gender are important. They indicate how salient the issue is and the degree to which journal editors contribute to addressing gender imbalances in citations according to their guidelines (Maliniak et al. Reference Maliniak, Powers and Walter2013). There is evidence that gender balance and citation statements by journals are seen favorably by researchers and that they can have a positive effect on the citation of women (Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Maliniak, Parajon, Peterson, Powers and Tierney2023).

We present the results of a mixed-methods content analysis. It combines a computational text analysis with the manual, qualitative coding of journal information. We find that 16 author guidelines out of 102 discuss gender in the context of a gender citation gap. These guidelines point the reader’s attention to gender imbalances in citations and encourage authors to be attentive to the gender distribution in the reference list. Our analysis indicates that higher-ranked journals are more attentive to the gender citation gap, with seven journals out of the 25 highest-ranked outlets (see below) addressing the issue. The analysis of American Political Science Association (APSA) section journals shows two out of 17 discuss gender in the context of citations, with none of the four (APSA) association journals mentioning this topic. One journal out of three that are run by the European Consortium of Political Research (ECPR) discusses gender and citations in its guidelines. In absolute terms, the results indicate that gender and citation go largely unnoticed in journal instructions. The numbers that we report must be seen as a lower bound because more editors may pay attention to gender and citations than is reflected in formal guidelines.

Data and analysis

The starting point of the exploratory empirical analysis was the list of all journals categorized as focusing on political science in the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) database.Footnote 4 At the time of our search, these were 294 journals for which we downloaded journal titles and journal metadata. The submission guidelines and author instructions were downloaded directly from the journal websites, mostly in spring 2022 (see reproduction material for details). The files were transformed into a machine-readable format to make them available for a computational text analysis.

The computational analysis was based on queries derived from an initial, qualitative reading of the author instructions to determine formulations with which journals may refer to gender and citations. In the computational content analysis, we identified journal instructions for further analysis by searching for any reference to "gender", "women", and "female." These broad terms were deliberately chosen to minimize the chances that we miss a journal guideline in this stage of the analysis. The instructions for which we got at least one hit for any search term were forwarded to the second, qualitative part of the design.

A submission guideline with at least one hit was read by one coder to determine the context in which the instructions refer to the search term. The codes were later validated by a second member of our team. An example of a guideline that discusses gender imbalances comes from the journal Political Communication: "The journal encourages submitting authors (and reviewers) to consider the composition of the cited authors or suggested works with respect to gender and minority representation. The journal encourages the use of, e.g., the (searchable by topic/expert) WomenAlsoKnowStuff and PeopleOfColorAlsoKnowStuff data bases." The term "gender citation gap" is not used, but the excerpt makes clear the gap is of concern to the editors. An example for a guideline that is gender-sensitive with regard to the research topics that are addressed in submissions reads (from Politics & Society): "[we] welcome papers proposing radical visions and alternatives, as well as those interrogating class, racial, national, and gender inequalities [in politics and society]."Footnote 5 While the journal explicitly invites research about gender inequalities, it does not have a gender provision in relation with citations.

We focus on the submission guidelines of the top-102 ranked and top-25 highest-ranked journals according to the 2020 Clarivate 5-year journal impact factor (IF).Footnote 6 On average, for the designated period, the articles in higher-ranked journals, as defined by the IF, get more attention citation-wise, compared to articles published in lower-ranked journals. It is likely that the cited work in articles of higher-ranked journals also get more attention than those in lower-ranked journals. If correct, gendered citation practices in journals with higher impact factors would have a greater potential to perpetuate a gender citation gap because future authors may draw their citations from men-biased references lists (on citation behavior, Bornmann and Daniel Reference Bornmann and Daniel2008; Bornmann and Leydesdorff Reference Bornmann and Leydesdorff2015). This reasoning implies that the inclusion of gender clauses in submission guidelines may influence researchers’ citation behavior beyond their own journal.Footnote 7 Higher visibility of work by women makes it more likely that their work is cited again by women and, to a lesser degree because of gendered citation practices, by men (Lerman et al. Reference Lerman, Yulin, Morstatter and Pujara2022). Another reason for the focus on higher-ranked journals is that they are likely to attract more submissions than lower-ranked journals that usually appeal to smaller scientific communities with a smaller pool of potential authors.Footnote 8 A higher number of submissions means that more researchers read the journal instructions. If they discuss gendered citation behavior, they are potentially more impactful because the number of researchers who may become sensitized to this topic.

The analysis of the top-100 and top-25 highest-ranked journals is supplemented by an analysis of three ECPR-run journals, four association journals of the APSA, and 17 journals maintained by APSA sections. The APSA noticed that women are disadvantaged in the pursuit of an academic career and acknowledges the importance of publications and citations of work by women (American Political Science Association 2005). Without the intent of casting blame, we find it interesting to determine how many section journals and association journals discuss gender imbalances in citations and possible counter-strategies in their guidelines. We understand that the section and association journals are managed by independent editorial teams. This makes it an open question as to how many journal instructions reflect explicitly the association’s goal to support the advancement of women in academia.

Findings

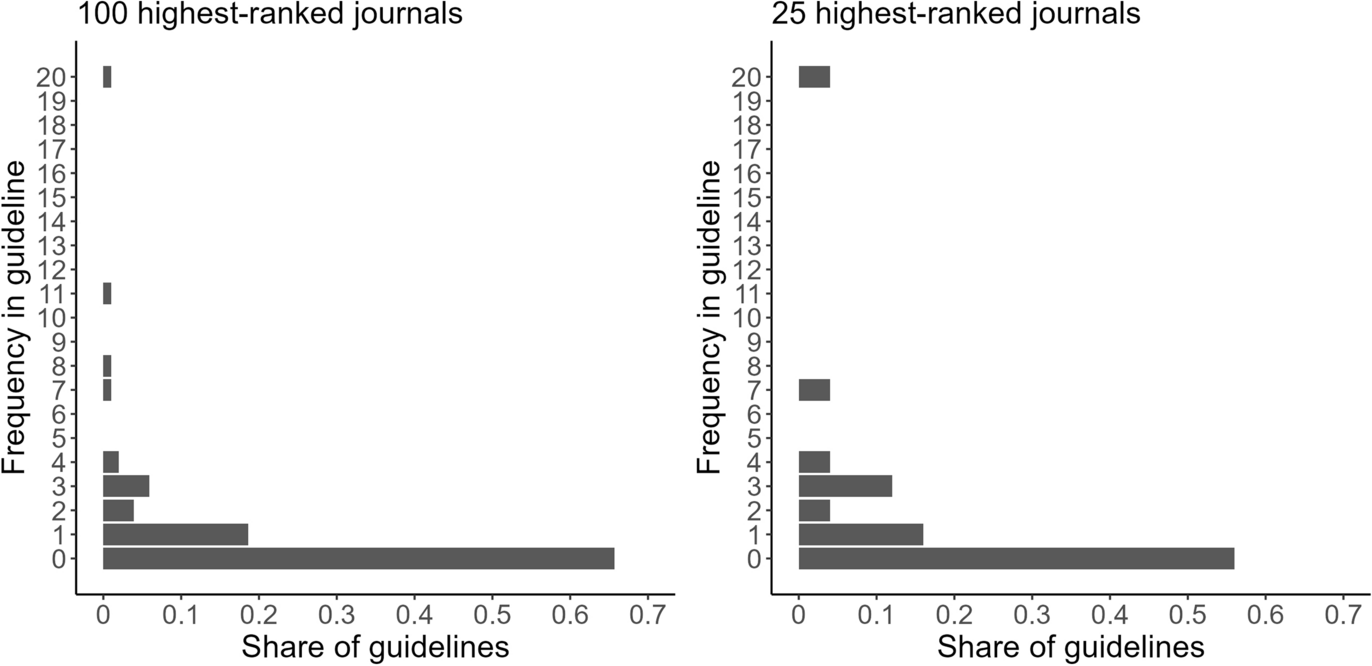

We first present the results for the computational keyword search for the 102 journals (left chart in Fig. 1) and 25 journals (right chart) that have the highest IF in 2020.

Fig. 1 References to ’female’, or ’gender’ or ’women’ in journal submission instructions

For the 102 highest-ranked journals, 67 (share of 0.66) do not contain any of the three keywords. The number of references to at least one search term varies across the remaining 35 journals (share of 0.34). The share of journals among the 25 highest-ranked with at least one mention of a search term increases to 0.44, equaling 11 journals in absolute terms. For the 17 APSA section journals (not visualized), seven include one of the search terms, while no association journal has any of the search terms in its guidelines. Two of the three ECPR-run journals mention one keyword at least once.

In the qualitative part of the analysis, the submission guidelines were read to determine in what context they refer to ’female’, ’gender’ or ’women’. From the 35 journals with at least one hit, we find that 16 discuss gender imbalances in citations and encourage authors to take the cited authors’ gender into account. The other 19 journals are false-positives for our research interest because they refer to the keywords in the context of research questions and topics. For the eleven journals among the top 25 with at least one keyword, we find that seven discuss gender in regard to citations. In total, about 16 percent of the 102 highest-ranked journals and 28 percent of the top 25 journals bring gender and citations to the attention of the submitting authors. From the seven APSA section journals that have at least one keyword in the guidelines, two discuss ’female’, ’gender’ or ’women’ in relationship with citations.Footnote 9 The two ECPR-run journals identified in the quantitative analysis include one discussion of gender in relation with citationsFootnote 10 and one false positive discussing gender in a different context.

These numbers should be taken as a conservative, lower estimate of the incidence of editorial practices that intend to reduce gender imbalances in citations. It is possible that editors encourage authors to reflect upon their citation practices without stating it in the submission and publishing guidelines. Editors may ask authors to calculate the share of referenced women and, possibly increase the share as part of a conditional-acceptance decision. However, we believe that editors would explicitly mention in the instructions if gender and citations were salient to them in the publishing process for the sake of transparency. Moreover, we assume that editors want to signal formally that they take action against a gender citation gap in the journal for which they are responsible if they have identified gender-imbalanced citations as a problem.

Another reason for taking this as a conservative estimate is that editors may address gender and citations on a web page other than the one on which they provide submission guidelines. We have not systematically checked all websites that belong to a journal because we assume that the topic has to be covered by the author instructions, as it concerns the citations and reference list of accepted articles. These assumptions could be wrong and the true incidence of editorial policies promoting gender-sensitive citation behavior could be higher than our numbers indicate.

Discussions and Conclusion

A gender citation gap implies that the research of women is less visible than the work of men and likely disadvantages women in the pursuit of an academic career. Journal editors have the means to at least encourage submitting authors to reflect upon whom they cite, to be more sensitive to gender imbalances, and to enhance the visibility of research by women. Our review of journal submission instructions indicates that at least 16 journals out of 102 that had the highest impact factor in 2020 discuss gender in relation with a citation gap. The analysis of the 25 highest-ranking journals show that seven of them discuss a gender citation gap, suggesting that the editors of higher-ranked journals are more attentive to gender and citation behavior.

The total numbers that we find in our analysis are low. They should be seen in the context of a discussion about gender, citations and publishing that only intensified over the last years in the field of political science (for example, Breuning and Sanders Reference Breuning and Sanders2007; Hancock et al. Reference Hancock, Baum and Breuning2013; Maliniak et al. Reference Maliniak, Powers and Walter2013; Teele and Thelen Reference Teele and Thelen2017; Breuning et al. Reference Breuning, Gross, Feinberg, Martinez, Sharma and Ishiyama2018; Brown et al. Reference Brown, Horiuchi, Htun and Samuels2020). If this discussion continues and more research about gender and citations is published across disciplines, the number of journals that adjust their submission guidelines is likely to increase. A replication of our analysis five or more years from now would show whether the low numbers that we found mark the beginning of a diffusion process, with more journals discussing gendered citations in their instructions. At present, the low share of guidelines with gender-and-citation provisions reflects a large potential of increasing the awareness for gender imbalances in citation practices. The absence of a gender provision does not necessarily mean that journal editors weighed the inclusion of a gender clause and decided against it. This is possible, but we believe it is more likely that editors have not considered yet whether to modify the submission guidelines. We encourage editors to evaluate the gender distribution of cited authors in their journals. In addition, we suggest considering the inclusion of gender provisions in their submission guidelines as a low-level intervention that may contribute to the reduction of gender imbalances in citations.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

An appendix and reproduction material - PDFs of submission guidelines, spreadsheets and R scripts - are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15045631.