Introduction

Eastern England is a region rich in Early Neolithic material culture, causewayed enclosures and other elements of this period’s lifeways (Abbott & Smith Reference Abbott and Smith1910; Warren et al Reference Warren, Piggott, Clark, Burkitt, Godwin and Godwin1936; J. Clark et al. Reference Clark, Higgs and Longworth1960), yet it is marked by the near total absence of long barrows, so central to life in Wessex and elsewhere. This demands explanation, and this article provides a step in this direction.

To begin with a clarification, in this paper we follow Frances Healy et al. (Reference Healy, Bayliss, Whittle, Pryor, French, Allen, Evans, Edmonds, Meadows, Hey, Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, fig 6.1) and define the boundaries of eastern England as the watersheds and immediate peripheries of the broadly easterly flowing rivers of East Anglia and the southern East Midlands (Figure 1), features more relevant to potential Neolithic groupings than modern county boundaries. Its integrity as a region is supported by the distribution of three distinctive ‘elements’: Mildenhall-style Early Neolithic decorated bowl pottery, causewayed enclosures with close-spaced ditch circuits, and geometrically squared (Bi) type cursus monuments (Healy Reference Healy and Barringer1984, 99–102; Pryor Reference Pryor1998, 209–12; Palmer Reference Palmer1976; Loveday Reference Loveday2006a), and indeed by the noted absence of long barrows.

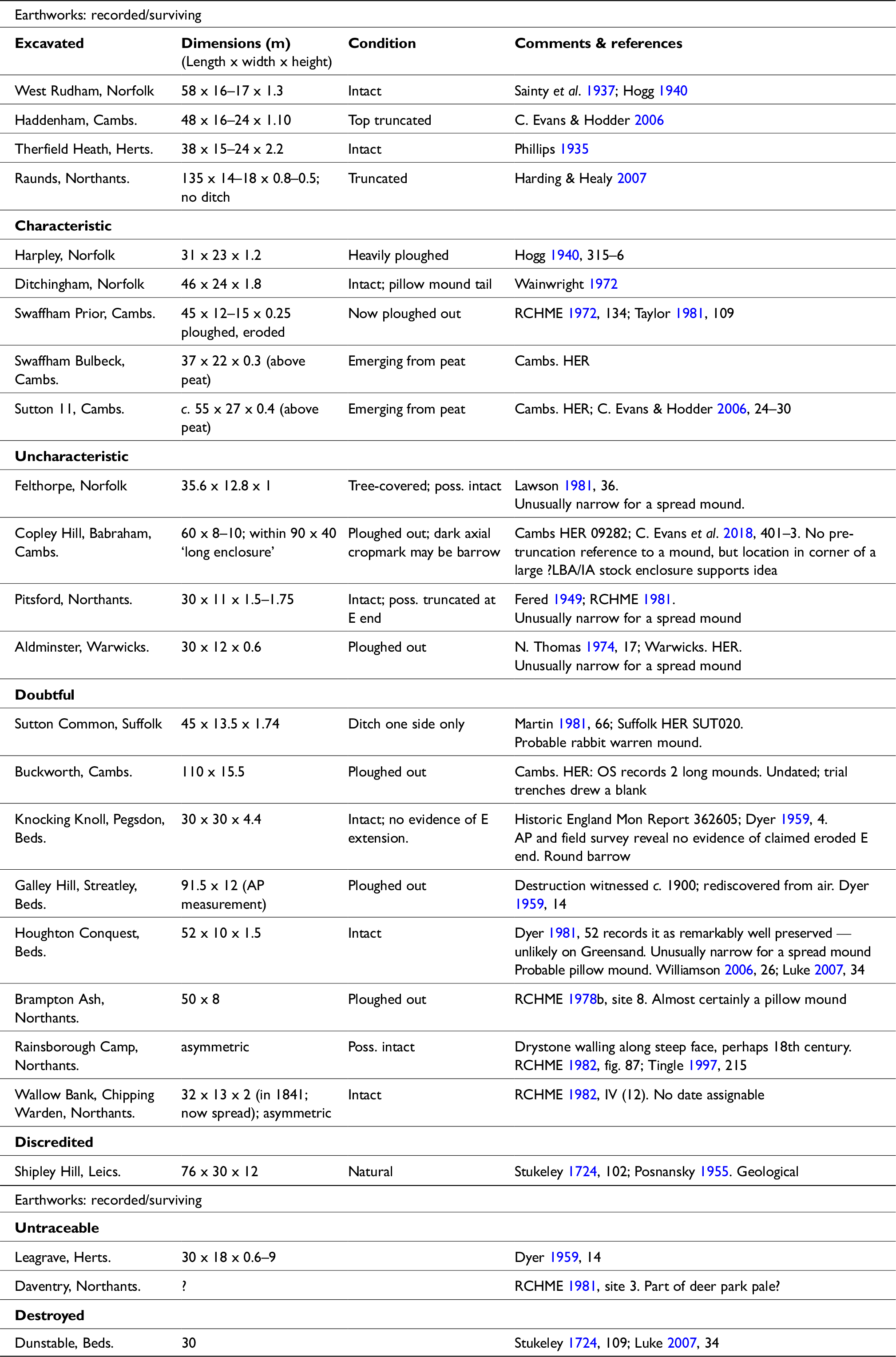

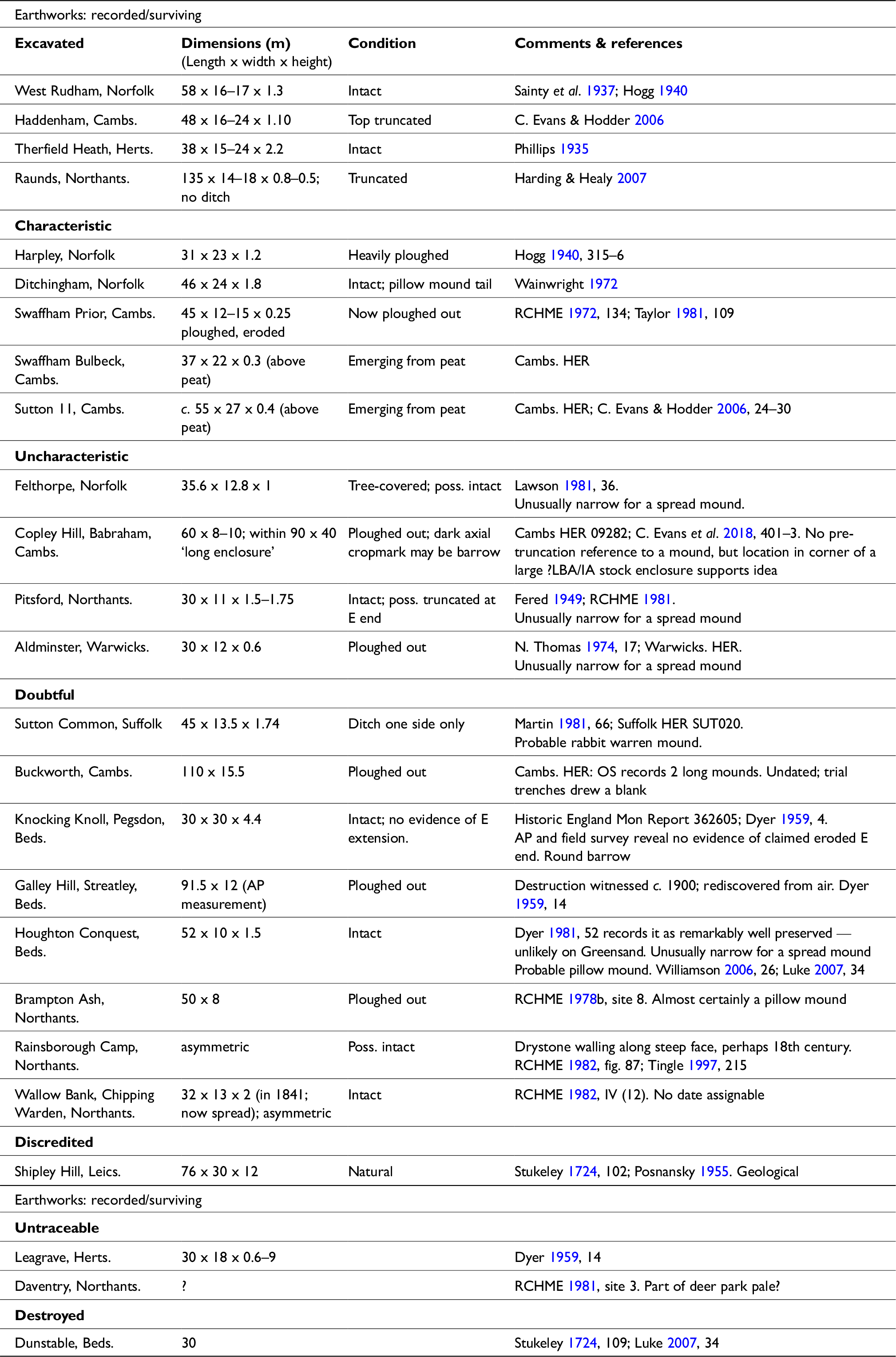

Figure 1. Distribution of site types in eastern England within 13–25 m normative width range. Red: surviving earthwork. Unexcavated fenland sites omitted due to uncertainty of form. Sites mentioned in the text: 1 Pitsford; 2 West Rudham; 3 Harpley; 4 Ditchingham; 5 Therfield Heath, Royston. See Figure 3 for an explanation of types.

Rarity of earthwork survival is, of course, immediately explicable in terms of the very different agricultural regimes practised over the last two millennia: pasturing on chalklands, cereal growing in eastern England. That does not, however, explain an absence of sites captured by aerial reconnaissance: continuous cropping regimes across significant areas of permeable soils should have delivered a rash of sites comparable to those of ploughed-out quarry-ditched long barrows on the chalk downs (eg, RCHME 1979a), and increasingly in their valleys (eg, Gill & Field Reference Gill and Field2019), if they existed. This has failed to happen. As Healy (Reference Healy2012, 9) stated with reference to Neolithic Essex, ‘[s]ustained aerial photographic reconnaissance and excavation have done nothing to alter the effective absence of classic long barrows’. Other site types, notably long enclosures, have been regularly recorded from the air in this region, however (Figures 1–2).

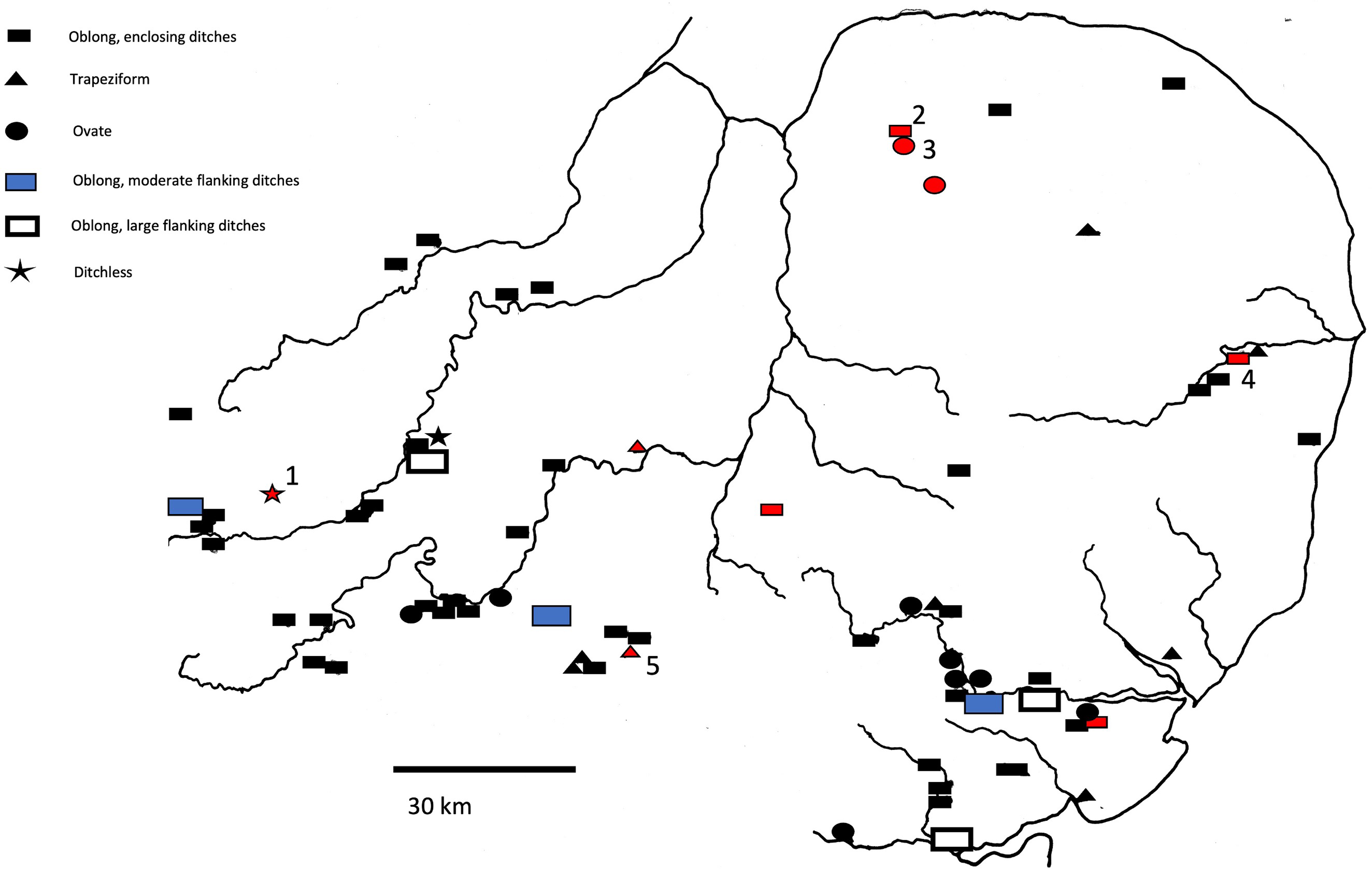

Figure 2. Examples of enclosing ditch sites. Top: Haddenham; West Rudham; middle: Eynesbury; Giants’ Hills 2, Skendleby; bottom: Broome; Roughton (with thanks to Chris Evans and David Robertson; redrawn by F. Gorke).

An answer could lie in differing structural traditions: whereas Wessex chalkland long barrows were largely created by spoil from two flanking quarry ditches that leave remnant signatures even when mounds have been levelled, excavation of rare upstanding East Anglian long barrows has revealed the use of turf (West Rudham, Norfolk; Royston, Hertfordshire; Haddenham, Cambridgeshire; Phillips Reference Phillips1935; Hogg Reference Hogg1940; C. Evans & Hodder Reference Evans and Hodder2006). Its gathering leaves no subsoil signature. Ditches of these barrows were comparatively slight, since they simply furnished capping material for the turf mound and were, unusually, of totally enclosing plan. If ploughed out they would closely resemble the long enclosures common across the region (Erith Reference Erith1971; Loveday Reference Loveday1985; Buckley et al. Reference Buckley, Major and Milton1988). Although these are commonly interpreted as open ‘long mortuary enclosures’ (assumed pre-long mound excarnation enclosures, based on bisection of an example (Site VIII) at Dorchester-on-Thames by a cursus ditch: Atkinson Reference Atkinson1951; Vatcher Reference Vatcher1961), interruption of ridge and furrow scarring across the interior of the example excavated at Charlecote, Warwickshire (W. Ford Reference Ford2003; Loveday Reference Loveday2006a, 56) leaves no doubt that there, as at Swaffham Prior, Cambridgeshire (RCHME 1972, 134; Shell Reference Shell, Bewley and Raczkowsku2002), a mound formerly filled the site.

Two developments have recently called the equation of turf mound and slight enclosing ditch into question as a blanket explanation for the region’s missing long barrows. First, excavation has revealed a levelled long barrow with typical flanking ditches at Redlands Farm, Raunds, Northamptonshire (P. Bradley Reference Bradley2007, 73–83), and another, less certainly, at Slough House Farm, Heybridge, Essex (Wallis & Waughman Reference Wallis and Waughman1998). Second, accumulating dates for cropmark long enclosures across southern Britain point to a Middle Neolithic (c. 3500–2900 BC) structural horizon, rather than an Early Neolithic (c. 4000–3500 BC) one (Harding & Healy Reference Harding and Healy2007, 98; Mudd & Brett Reference Mudd and Brett2012). It is possible then that these were indeed open enclosures — small versions of cursuses — rather than long barrows (Healy Reference Healy2012, 15). This would accord with the evidence of the long enclosure at Site VIII Dorchester-on-Thames, and a similar site at Raunds, set immediately adjacent to a partially preserved, ditchless long mound (Atkinson et al. Reference Atkinson, Piggott and Sandar1951, 60; Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Atkinson, Chambers and Thomas1992; Harding & Healy Reference Harding and Healy2007, 94–8). Yet the evidence from Charlecote is unassailable and traces of former mounds have also been recorded within long enclosures protected by alluvium at Manor Farm, Old Wolverton, Buckinghamshire (Hogan Reference Hogan2013), and Brampton, Cambridgeshire (Malim Reference Malim1999, 80; pers. comm.). The picture then has become more confused since assessment three decades ago (Loveday & Petchey Reference Loveday and Petchey1982; Loveday Reference Loveday1985; Reference Loveday and Gibson1989). Yet if we are to understand the monumentality of Early and Middle Neolithic eastern England, such questions demand a resolution.

Whilst total excavation of a significant sample is one solution, that would present a challenge given the expense of sampling sufficient long enclosures to draw valid conclusions, the renowned cleanliness of their ditches, a near total absence of earthwork evidence, and lack of an archaeological subsoil signature for the utilisation of turf. Equally, fieldwalking holds little hope: the programme instigated at Cardington, Bedfordshire, recorded very little flint directly over the long enclosure, a finding explicable either in terms of the blanking effect of a former mound, or a sacrosanct, open interior (R. Clark Reference Clark1991, 10; Malim Reference Malim and Dawson2000, 75). The handful of possible long barrows in the region which have survived by virtue of inclusion in heath or common land, however, furnish an invaluable resource. Establishment of their ditch plans by geophysical survey has the potential to produce a secure database against which cropmark enclosures can be compared.

This was the premise of the Characterising survivors, explaining absence project (Loveday et al. Reference Loveday, Harris, Carey and Ashby2018), and this article presents the results of this study. We begin by setting out our methodology for the selection of sites and our terminology. We then review the evidence from potential long barrows to justify the sample selection, before summarising the results of our geophysical surveys (full details are available in the supplementary materials). Having done so we can then employ our generated evidence to assess the aerial photography, and morphological, orientation, and dating considerations. This provides us with a comprehensive picture from which we can return to our research questions: do these ploughed-out sites represent long barrows, and if so, what can we say about their specific forms of architecture and comparanda?

Site selection

Site selection proved an immediate problem. While West Rudham and Ditchingham have substantial mounds, how were lesser sites such as Pitsford and Houghton Conquest to be regarded? The variety of mound/long enclosure structures encountered during excavation at Raunds (flanking quarry ditches, ditchless turf, and open long enclosure: Harding & Healy Reference Harding and Healy2007) demonstrate the dangers of simply transposing classic chalkland models to a region that is as close to the Continent as it is to Wessex. Yet acceptance of lower/slighter mounds (eroded or simply different?) opened up the danger of sample contamination by post-medieval warrens, or pillow mounds as they are known. However, pillow mounds rarely exceed 8 m in width, while spread long barrow mounds fall overwhelmingly between 12–25 m (Williamson & Loveday Reference Williamson and Loveday1988; Kinnes Reference Kinnes1992, 66–8; Field Reference Field2006, 66).

The methodology adopted was therefore:

-

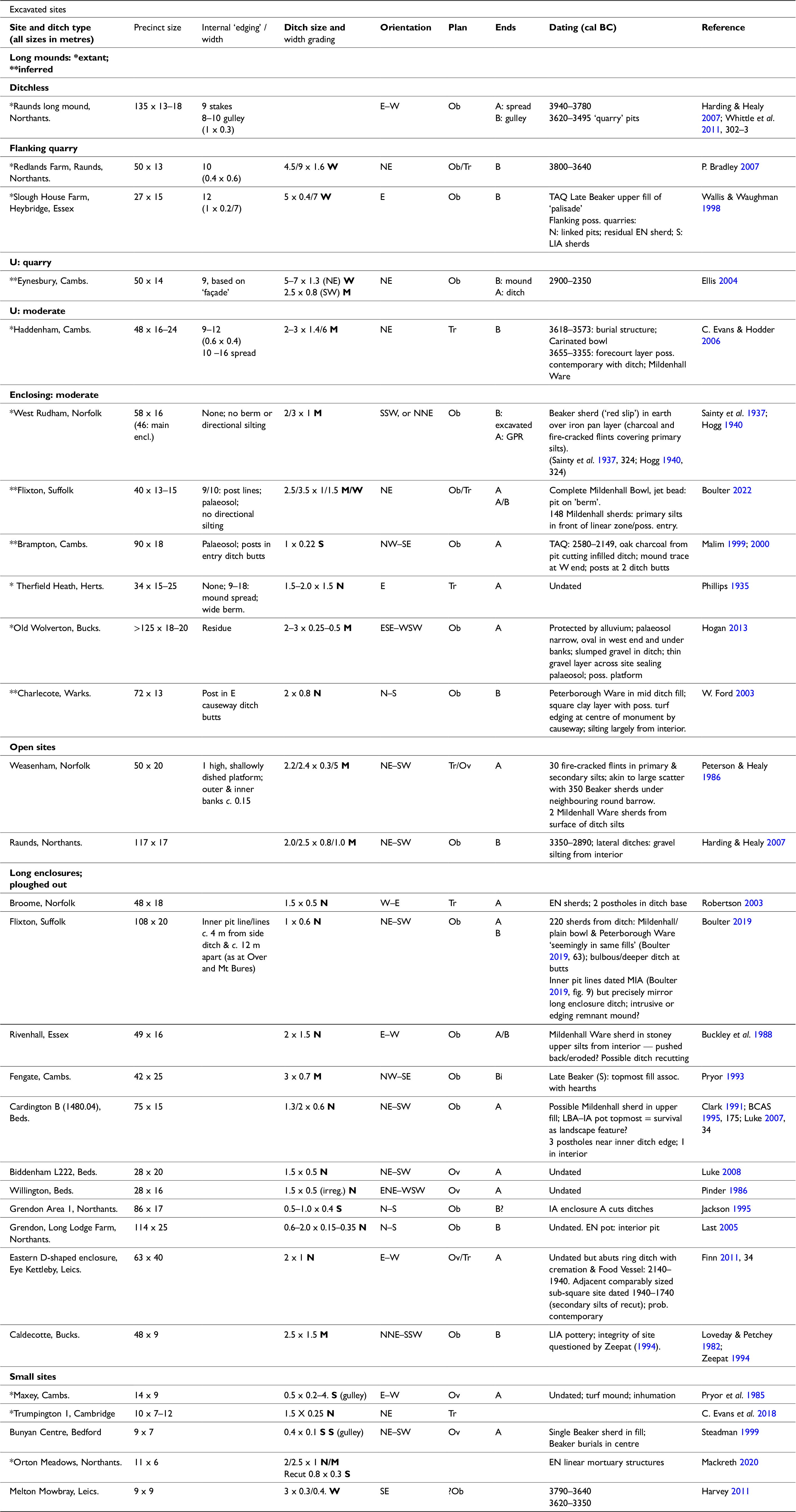

1. To establish the dimensional parameters of proven Neolithic long mound and long enclosure sites in eastern England (Table 1).

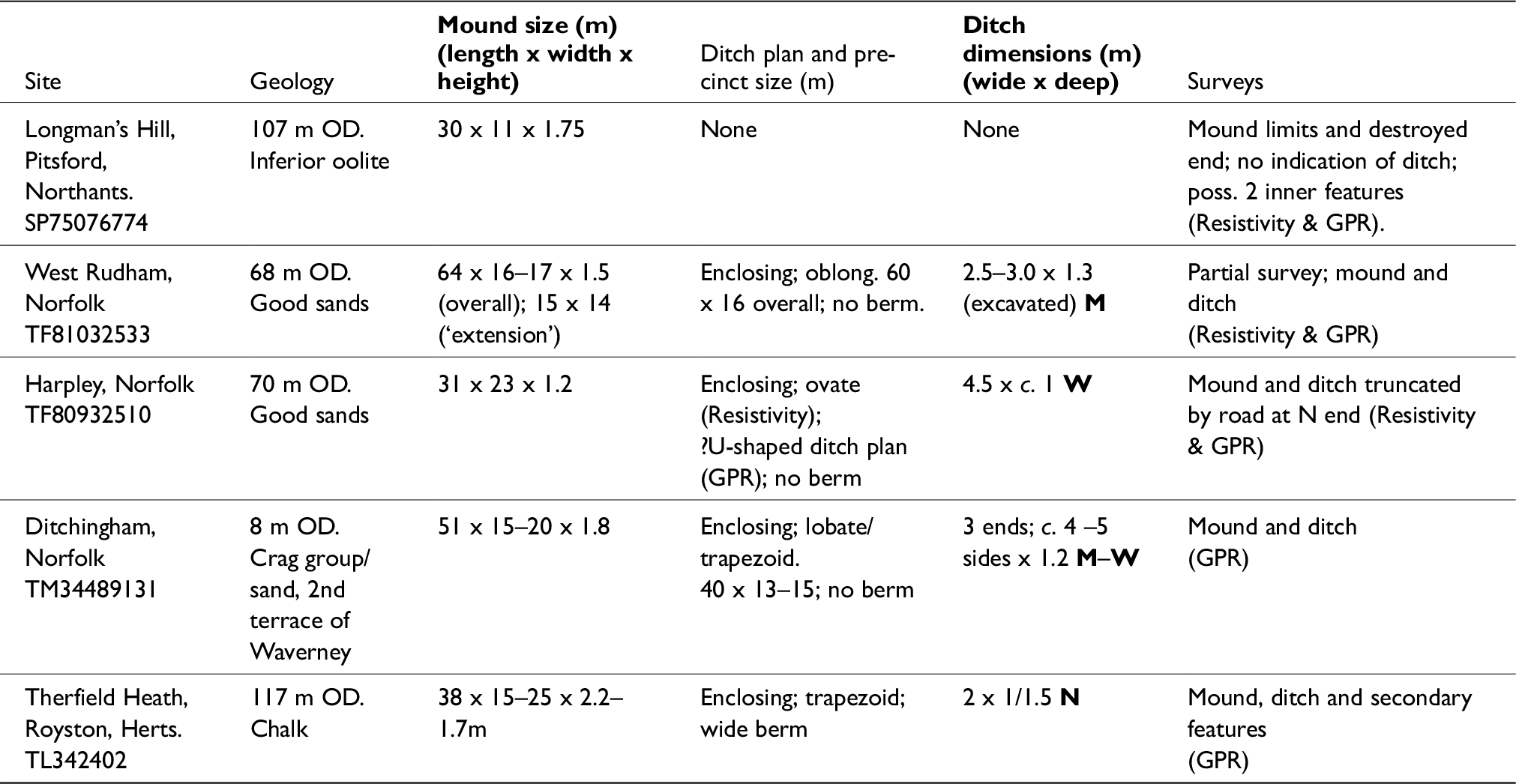

Table 1. Excavated sites in eastern England: long mounds, long enclosures, and small elongated to ovate sites. Abbreviations: Ob – oblong; Tr – trapezoid; Ov – ovate; A – convex end; B – straight end; Bi – precisely squared; S < 1 m (slight); N 1–2 m (narrow); M 2–3 m (moderate); W >3–4 m (wide). Abbreviations: AP – aerial photography; OS – Ordnance Survey; U – U-shaped. Single orientations are employed where a façade, burial structure or mound height indicate a clear ‘front’ end.

-

2. To use these data to assess sites that have been claimed as surviving long barrows (Table 2), and to select examples for geophysical survey.

Table 2. Long mound earthworks in eastern England. Oval barrows (eg, Lawson Reference Lawson1981, 21) have been excluded. HER – Historic Environment Record.

-

3. To compare the results of the surveys (Table 3) with the features of unexcavated cropmark long enclosures (Table 4) that broadly conform to the width parameters established in Table 1.

Table 3. Geophysical surveys. Alphabetical parish labels as in Loveday (Reference Loveday1985).

Table 4. Unexcavated sites (data from Loveday Reference Loveday1985; Buckley et al. Reference Buckley, Major and Milton1988; Deegan & Foard Reference Deegan and Foard2007; Luke Reference Luke2008; Edwards Reference Edwards2013; D. Knight et al. Reference Knight, Last, Evans and Oakey2018; Boulter Reference Boulter2019; Reference Boulter2022; Martin Reference Martin1981; Suffolk & Herts HER). Terminals determined by plan: A – convex; B – straight; A/B – flattened centre; Bi – precisely square. Note: short Bi sites (eg, Fengate) omitted due to difficulty of differentiation from Romano-British sites.

-

4. To consider the implications of the findings for structural interpretation and wider issues of date and possible origin. Do long enclosures represent the missing long barrows?

Terminology

To ensure clarity, we employ the following terminology, suitable for both earthwork and plough-razed sites:

-

• Long enclosure: ditch of varied plan enclosing a site. The label ‘mortuary’ is omitted, as unproven.

-

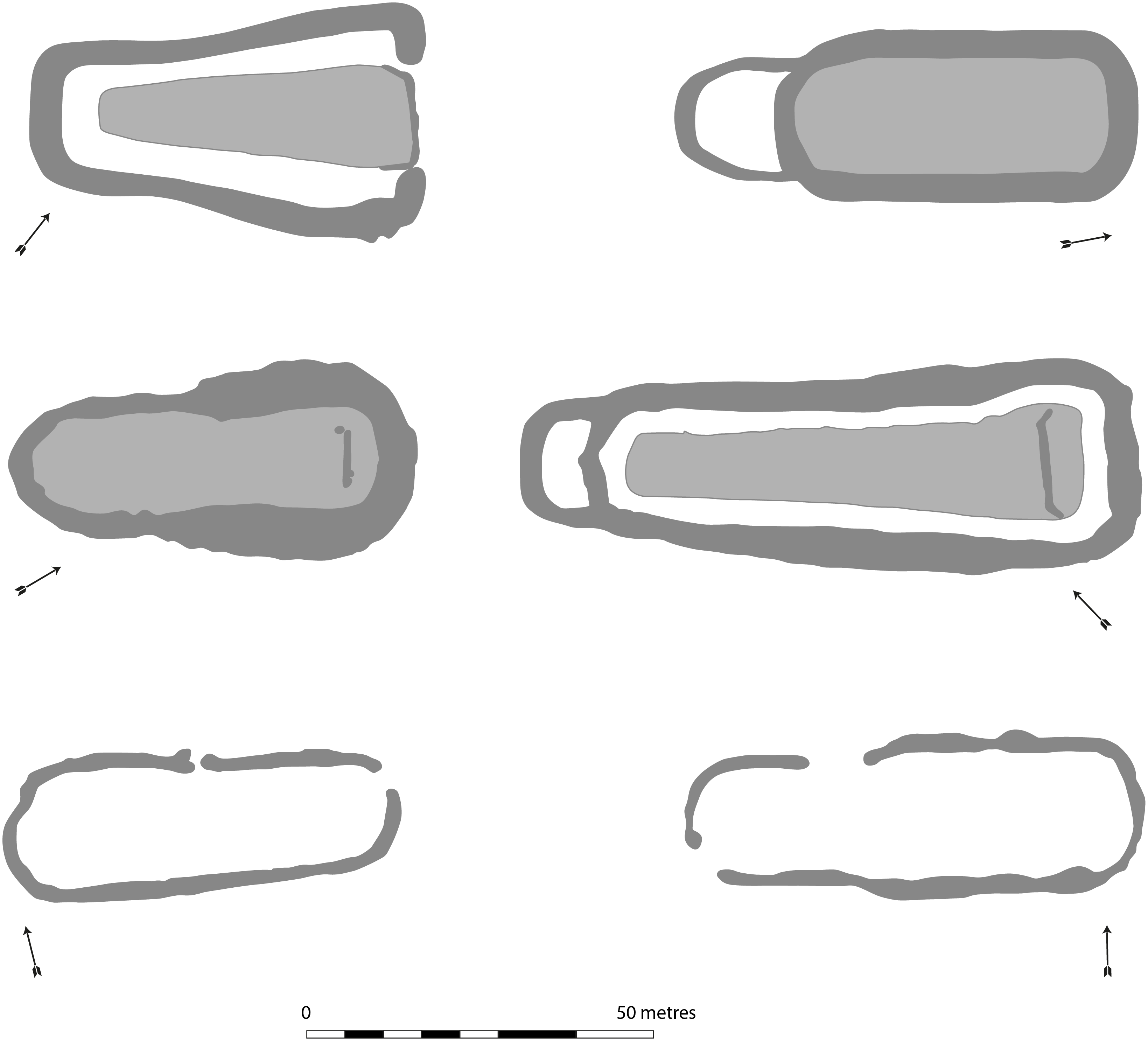

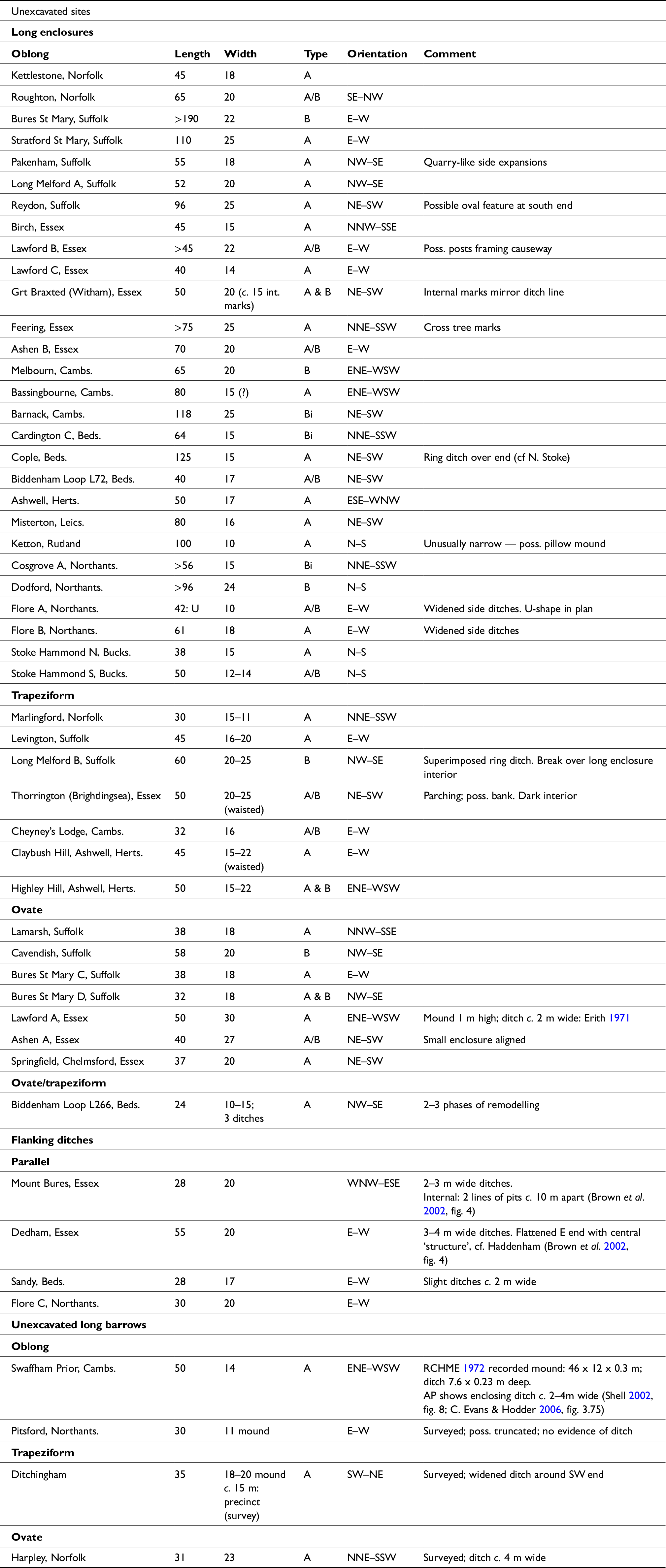

• Oblong, Trapeziform, and Ovate: terms describing the ditch plan along the sides of a site, whether these fully enclose, partially enclose, or simply flank the site (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Long enclosure forms.

-

• Types A, B, and Bi: shorthand for convex, straight, and precisely squared ends/terminals of enclosing or U-plan sites. These designations arise from classification of cropmark sites (Loveday Reference Loveday1985; Reference Loveday2006a) — the principal focus of interest here — and are distinct from Ian Kinnes’ (Reference Kinnes1992, 65–6) alphabetic classification of long barrow ditch plans.

-

• Edging devices: gullies, post lines, and façade trenches recorded by excavation or aerial photography within site precincts.

-

• Precinct: the area between the inner edges of ditches.

-

• Ditch widths: approximately divided as: slight <1 m; narrow c. 1–2 m; moderate c. 2–3 m; wide > c. 3 m. These divisions are intended as rough aids for monitoring broad trends; ditch digging and erosion are too variable to allow for precision.

None carry implications of date or function.

Excavated long barrow/long enclosure sites in the east of England

Broad conclusions that can be drawn from Table 1 are that most surviving, or evidenced, long mounds in the region are 13–18 m wide, comparable to the 12–23 m range recorded nationally (Field Reference Field2006, 66); measurements of 9–10 m relate to the distal ends of trapezoid mounds. Where evident, edging devices recorded beneath mound skirts or within ditch cropmarks conform to the tight 9–12 m southern British long barrow norm (Loveday Reference Loveday2020, tab. 7.1). That dimensional range has been recognised more widely (western France: Laporte Reference Laporte, Laporte and Scarre2016, 25, fig. 2.8; Denmark: Midgley Reference Midgley1985, tab. 2e), suggesting it had broad conceptual significance. Precinct widths in the oblong series, however, contrast with the national norm of 20–25 m, clustering instead between 13–20 m. A few, along with trapezoidal and ovate precinct widths, are greater, suggesting an upper width limit of around 25 m. Sizing outside this range likely denotes difference of age (eg, Eye Kettleby, Caldecotte). A small grouping below 10 m represent embanked mortuary structures, akin to initial phases at Nutbane, Hampshire (Morgan Reference Morgan1959), or Haddenham (C. Evans & Hodder Reference Evans and Hodder2006, fig. 3.28), rather than fully-fledged long barrows. That two of them lay beneath round mounds reinforces the point.

The normative precinct width range of 13–25 m established from excavated sites has therefore been employed as the standard for aerial photograph site identification and is reflected in Figure 1.

Claimed surviving long barrows in eastern England

Applying the spread mound width norm to surviving sites in eastern England reveals nine, possibly 13, extant or recorded mounds with good claims to be long barrows (Table 2). Of these sites Harpley, Ditchingham, and West Rudham in Norfolk and Therfield Heath in Hertfordshire were deemed characteristic and worthy of survey; the latter two in order to establish the ditch plan beyond the prior keyhole excavation. Swaffham Prior, recorded as a barrow but now ploughed out, was omitted, since it seemed unlikely that geophysical survey could improve upon very clear aerial photographic data (Shell Reference Shell, Bewley and Raczkowsku2002; C. Evans & Hodder Reference Evans and Hodder2006, fig. 3.75). Barrows emerging from the peat were excluded due to uncertainty about ground-penetrating radar’s effectiveness at depths potentially in excess of 2 m. Felthorpe, Norfolk, could not be surveyed due to dense tree cover, but might anyway be questioned given its relative narrowness. Similar dimensional reservations applied to Aldminster, Warwickshire (c. 12 m), and to Longmans Hill, Pitsford, Northamptonshire, but since the latter was already recorded as an antiquity in 1712, it is unlikely to be a pillow mound. Knocking Knoll, Pegsdon, Hertfordshire, has long been included amongst the region’s long barrows (Dyer Reference Dyer1959, 14; Ashbee Reference Ashbee1970, 169) but, after study of aerial photographs, we agreed with the Ordnance Survey field investigators that it represents a round barrow. Details and summary assessment of all sites still upstanding or recorded as such are given in Table 2.

The geophysical surveys thus sampled all accessible proven and characteristic long barrows where full details of ditch morphology were lacking, and one uncharacteristic site, Pitsford.

Geophysical surveys

Here we summarise the outcome of the geophysical surveys. For details, please see online Supplementary S1.

Longman’s Hill, Pitsford, Northamptonshire (SP 7507 6774)

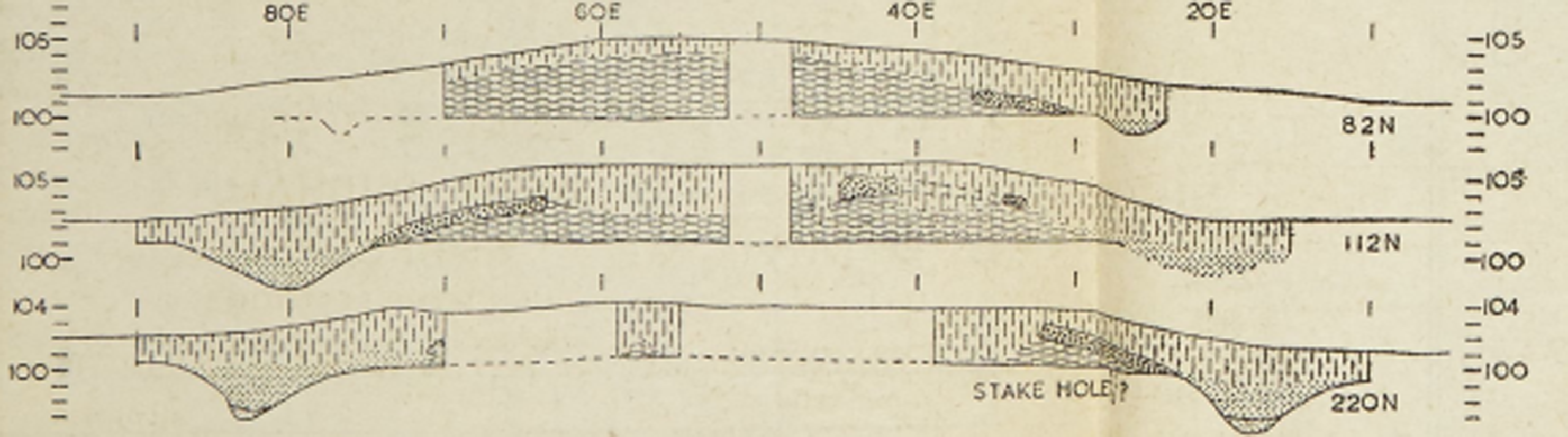

This unexcavated flat-topped, sub-rectangular mound measures 30 x 11 m. It is tightly constrained on all but its east side by modern development (Fered Reference Fered1949; RCHME 1981, 161). GPR survey (Figure 4) indicated probable stone construction. Two possible air voids at approximate ground level (1.5 m below the mound surface) in western and eastern central areas may mark cists. Absence of a ditch signal could be explained by the closely adjoining road and gardens, but lack of evidence at the eastern end, where GPR recorded possible superficial remains of the truncated mound, suggests the site lacked an enclosing ditch, as John Morton recorded (Reference Morton1712, 548).

Figure 4. Pitsford survey GPR results. The eastern levelled strip in A broadly corresponds to the base of mound readings in C.

The flat-topped form of the mound is atypical of long barrows, as is its width; while erosion along the flanks cannot be excluded, 11 m is closer to defined/built barrow widths than to spread mounds. Early recording (Morton Reference Morton1712), however, excludes interpretation as a pillow mound. If the two anomalies indicate cists, these could relate to the Saxon burials recorded in 1882 (Fered Reference Fered1949), almost certainly from the site, but their depth is greater than expected of secondary burials. Even spacing and depth rather suggest two small round mounds of Notgrove type. In that context the apparent twin lobate form of the signals from the levelled east end is suggestive (Darvill Reference Darvill2004).

West Rudham, Norfolk (TF 81032533)

Excavation of this substantial heathland barrow in 1937 and 1938 (Sainty et al. Reference Sainty, Watson and Clarke1937; Hogg Reference Hogg1940) established that the mound was composed of turf, thinly capped by gravel from a moderate enclosing ditch close to the mound edge. Disturbance by warreners had spread the mound over the ditch. Vegetation restricted our geophysical survey to the northern half of the site.

Resistivity survey (Figure 5) confirmed the form of the enclosing ditch, which exhibits a small possible causeway at the north-east ‘corner’, although that could result from infill of Hogg’s trench (M. Gill pers. comm.). The low-resistance ditch signal presents as a ‘spread’ on the mound’s eastern side, extending beyond the area surveyed. Its form appears more disturbed on the western flank, where there are several high-resistance anomalies. Together these give the appearance of possible double ditches (cf. Radley: R. Bradley Reference Bradley1992), a reading belied both by GPR and excavation data.

Figure 5. West Rudham surveys, GPR and Resistivity.

GPR survey identifies the mound as high-amplitude material, consistent with turf. The ditch shows as a single feature some 3 m wide at 1.5 m below present ground level (bpgl), consistent with Hogg’s (Reference Hogg1940) findings.

Both surveys reveal that the northern terminal ditch was curved, not flattened as assumed in Hogg’s projections (Reference Hogg1940, fig. 2). Feature width at that point broadly agrees with his three sections, as does its greater depth: registering by GPR at 2.00–2.10 m below present ground level (bpgl) when lateral ditch-line signals are absent. This, coupled with the equation of ditch and turf mound capping volumes (Hogg Reference Hogg1940, 323–4), confirms the accuracy of Alexander Hogg’s sections over those of J.E. Sainty et al. (Reference Sainty, Watson and Clarke1937).

Both surveys hint at irregularity of the outer edge of the ditch, not recognised in Hogg’s sections. That on the east side may in part register soil build-up in a depression just to the east of the ditch (Hogg Reference Hogg1940, 316) that contained a ‘cooking site’, while on the west side one of the outer resistivity readings likely registers the ‘hollow in the heath’ investigated as a possible spoil pit for the barrow, but dismissed in view of its steep sides (Sainty et al. Reference Sainty, Watson and Clarke1937, 326).

Harpley, Norfolk (TF 8093 2510)

This unexcavated, sub-oval long barrow stands on former heathland, similarly aligned and just 190 m south of the West Rudham barrow. Before ploughing in 1938, a ditch-hollow 4.5 m wide was recorded around the mound except at the north end, where the site had been damaged by a road (Hogg Reference Hogg1940, 315–6). Today the severely truncated remains are protected by roadside pasture.

Resistivity survey revealed the mound as an ovate high-resistance anomaly (Figure 6). GPR survey reveals the mound as high-amplitude material, consistent with turf. It is encircled by the ditch evident as a low-amplitude response. At a depth of 0.50 m bpgl this appears to be c. 4 m wide, narrowing to c. 2 m at a depth of 0.80–1.40 m bpgl. It becomes difficult to identify below c. 1.50 m bpgl. Greatest precinct width is recorded as 25–26 m.

Figure 6. Harpley surveys, GPR and Resistivity.

The GPR and resistivity surveys at Harpley have provided a ditch plan and indicated survival of intact mound material, albeit severely truncated. Topographic and LiDAR data support the idea that construction of the road cut the north end of the monument, impacting the ditch (whether of encompassing or U-shaped plan) rather than the mound.

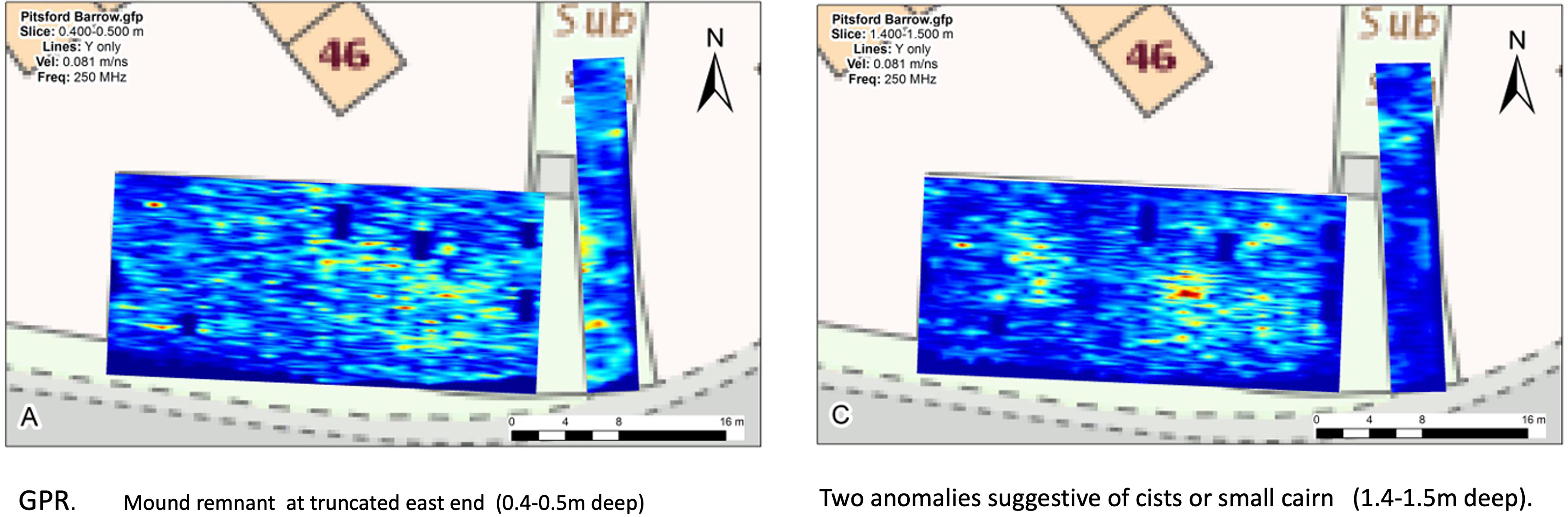

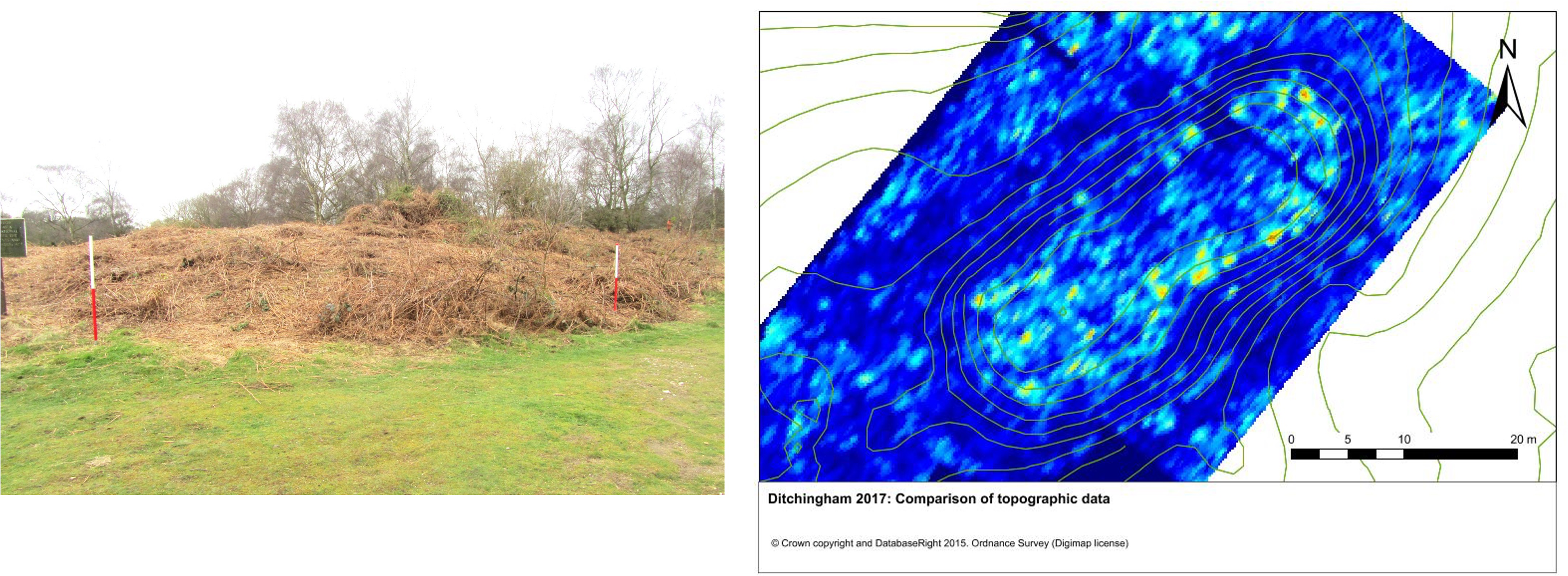

Ditchingham, Norfolk (TM 3448 9131)

This unexcavated, intact long barrow was first recognised by Rainbird Clarke in 1941. Healy (Reference Healy and Barringer1984, 86, 101) records Carinated Bowl sherds from the mound surface, identical to those from the adjacent settlement, arguably inclusions in turf used for mound construction.

In topographic survey the long barrow mound appears wedge-shaped with possible ditch depressions on its east and west flanks. An earthwork tail, 42 x 3 m, joins the south end of the long barrow slightly to the west of centre. Of note are two hollows on either side of the tail, suggesting that it is a later addition. It is within the dimensional range of a pillow mound (Williamson & Loveday Reference Williamson and Loveday1988).

GPR survey (Figure 7) reveals the ditch as a low-amplitude response, fully surrounding the irregular, lobate mound. The north-east end the ditch is of regular, convex-ended plan and 2.5–3 m wide. Further south it widens on both sides, recalling quarrying activity at Eynesbury, Cambridgeshire (Ellis Reference Ellis2004). The ditch appears to abut or underlie the edges of the mound, defining a precinct c. 15 m wide. The spaced flanking earthwork depressions extending beyond the ends of the barrow are therefore not ditch features, but — as shown by LiDAR — rather relate to footpath wear. No clear-cut responses are evident which might represent features within the barrow mound.

Figure 7. Ditchingham (Broome Heath). Left: north end of long barrow; right: GPR and topographic data.

The GPR survey has demonstrated that the ditch closely mirrors the mound and, as at West Rudham, is not separated by a berm. Lobate mound and ditch form can be paralleled in the region (eg, Eynesbury (Ellis Reference Ellis2004, fig. 12), Ashwell (Wilson Reference Wilson1982, fig. 47b)) and beyond on the Lincolnshire Wolds (Drury & Allen Reference Drury and Allen2020, figs 9.2–3), notably Ulceby, with Fordington dated 3635–3340 cal BC from an antler pick in the primary silts (Jones Reference Jones1998, 106: site 5). Alternative explanation as an imposed round barrow would have to accommodate the lack of a ditch signal crossing the mound — conceivable if dug at a high level through turf.

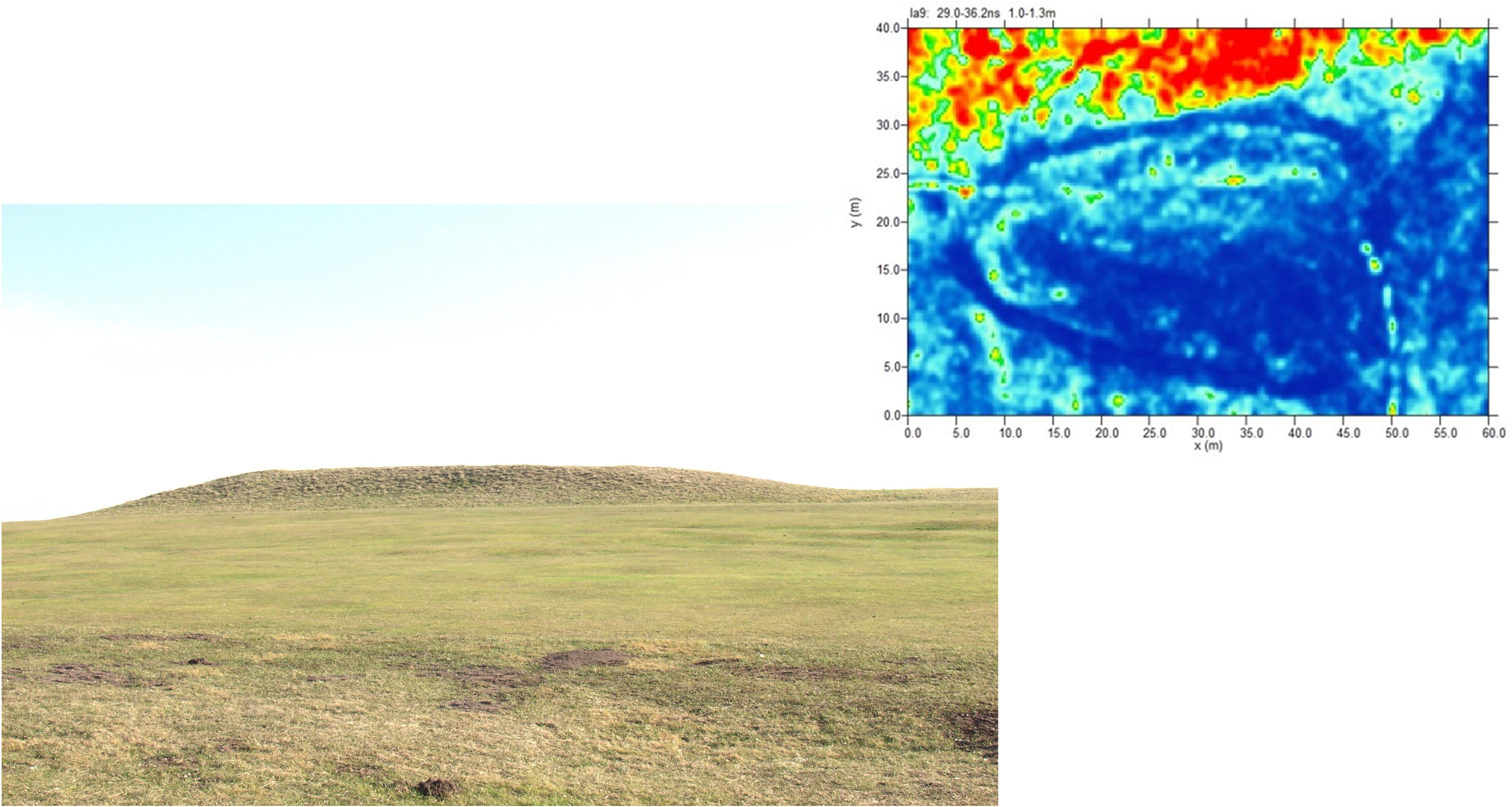

Therfield Heath, Royston, Hertfordshire (TL 342402)

This trapezoidal long barrow stands just below the highest point of the chalk down, where it would be skyline-sited from the Cam Valley to the north. The southern ditch can be traced on the ground, but along the northern flank it is less clear.

Digging by Edmund Nunn in 1855 recorded two ‘cysts’ (pits containing ‘ashes’) 5.5 m apart just west of the centre of the barrow with an adjacent heap of bones. Excavation by Charles Phillips in 1935 recorded, against expectations for a chalkland site, a turf mound capped from a slight, ovoid enclosing ditch. That has remained the accepted ditch plan despite aerial photographic evidence (eg, NMR 23354/34: Field Reference Field2006, pl. 29) suggesting a more trapezoidal plan similar to Haddenham (C. Evans & Hodder Reference Evans and Hodder2006).

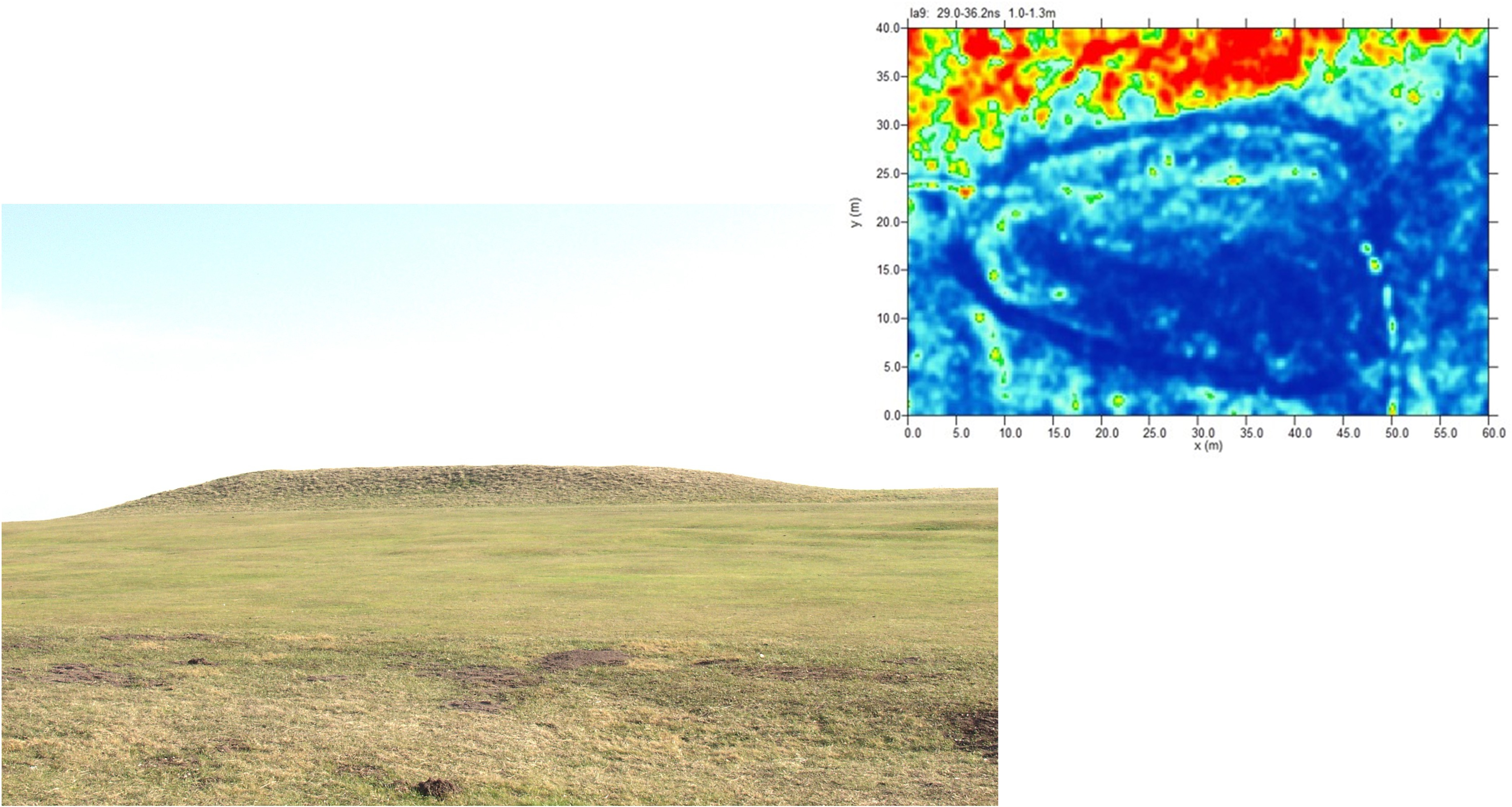

In GPR survey, the long barrow ditch is clear from a depth of 0.2–0.3 m bpgl to about 2 m, consistent with Phillips’ sections (Reference Phillips1935, fig. 3) (Figure 8). Absence of field evidence raised questions about its presence at the east end of the site, but deep pass 0.8–1.0 m shows it curving south. From the southern flank, it appears as a slighter feature, curving northwards (see Supplementary S1). With the possible exception of a causeway at the south-east ‘corner’, the ditch encompasses the trapezoidal barrow with minimally curved sides.

Figure 8. Therfield Heath, Royston. The photo shows the view from the north and the GPR plot 1.0–1.3 m below present ground level.

Ditch readings are consistent with Phillips’ excavated sections (Reference Phillips1935, fig. 3), although stronger readings and field evidence suggest incipient quarry-like digging along the southern flank. The trapezoidal/heart-shaped plan revealed by GPR survey finds no close parallels regionally. Only three sites closely correspond: Levington, Suffolk (co.no. 134), Purley A, Berkshire (co.no. 138), and Latton, Wiltshire (co.no. 136) (Loveday Reference Loveday1985). While too great an emphasis should not be placed on precise convergences of ditch morphology, there seems no doubt that the Therfield Heath ditch was laid out with care.

Assessing the aerial photography evidence from eastern England in the light of the earthwork surveys

The long barrow geophysical surveys (Table 3) reveal that:

-

1. All, apart from Pitsford, have enclosing ditches;

-

2. Precinct widths are comparable to those of excavated cropmark long enclosures (Table 1);

-

3. All ditch plans (oblong, trapeziform, and ovate) are represented;

-

4. All have convex (type A) ends;

-

5. Ditches are principally of moderate width, although expansion along site flanks is evident at Ditchingham and Harpley, and recorded by excavation at Eynesbury.

Each of the sites — bar the West Rudham extension — can be paralleled within the regional corpus of cropmark long enclosures, based on an earlier national survey (Loveday Reference Loveday1985) updated and supplemented with additional data (Table 4). The degree and extent of correlation needs to be established for secure aerial photograph interpretation.

While not exhaustive Tables 1, 3, and 4 (excluding sites outside the 10–25 m width norm) furnish a corpus of 72 long barrows/long enclosures, of which only six have separate flanking ditches (only three classifiable as quarry-like). This is a sample large enough for reasonable statistical security, but with necessary caveats regarding the difficulty of precise measurement from aerial photographs. Caution is also needed in interpreting distribution (Figure 1): sites in the Stour Valley reflect ideal conditions for cropmark production, while those in the Waverney Valley result from rare monument survival (Ditchingham) and quarrying.

Morphology and dimensions

Morphology

The fact that only three sites certainly have terminals of differing types at opposing ends (a fourth, West Rudham, has been disproved above) confirms either intent, or that the practices carried out by the builders often resulted in similar outcomes.

Tables 1, 3, and 4 demonstrate that type A (convex) ends are overwhelmingly dominant regionally, with a substantial number of A/B type terminals with rounded corners but straight centres. If these represent imprecise ‘squaring’, A and B types are fairly evenly divided. Amongst long enclosures with type A terminals, ditch line regularity is particularly evident at wider/longer examples such as Feering and Stratford St Mary, where size would have imposed the greatest challenge to accurate layout. This strongly suggests the plan had encoded significance. Sites of Bi type send a similar signal, but are likely to be underrepresented in the present sample due to the difficulty of differentiation from Romano-British sites. They, and other less regular square-ended sites, grade into the numerous expanded sites of proto- and minor cursus types in eastern England (cf. Tabor Reference Tabor2023). Sites with type A terminals are more consistently associated with mound evidence than those with type B, suggesting the form can be taken as a barrow signature, albeit not exclusive (eg, Haddenham, Charlecote).

Oblong plans predominate at 70%. This contrasts with neighbouring Lincolnshire, where trapeziform plans are most common (44%, versus 32% oblong and 23% ovate (Jones Reference Jones1998, fig. 2)), and the Cotswolds, where it overwhelmingly dominates (Corcoran Reference Corcoran, Powell, Corcoran, Lynch and Scott1969, 41–68; Darvill Reference Darvill2004). The contrast is arguably even greater, since tapering is often slight (eg, Broome, Marlingford, Levington) and may in some cases, as at Haddenham, result from multiphase construction (eg, Long Melford B, Claybush Hill, Ashwell, Ditchingham; see above).

Causeway placement within the oblong group varies according to terminal shape: frequently broadly central within terminals of type A; at a corner or just offset from it amongst type B. Whilst not exclusive, this pattern is echoed amongst full-scale cursus sites (Loveday Reference Loveday2006a, figs 14, 56). A causeway in the centre of one long side is also quite common.

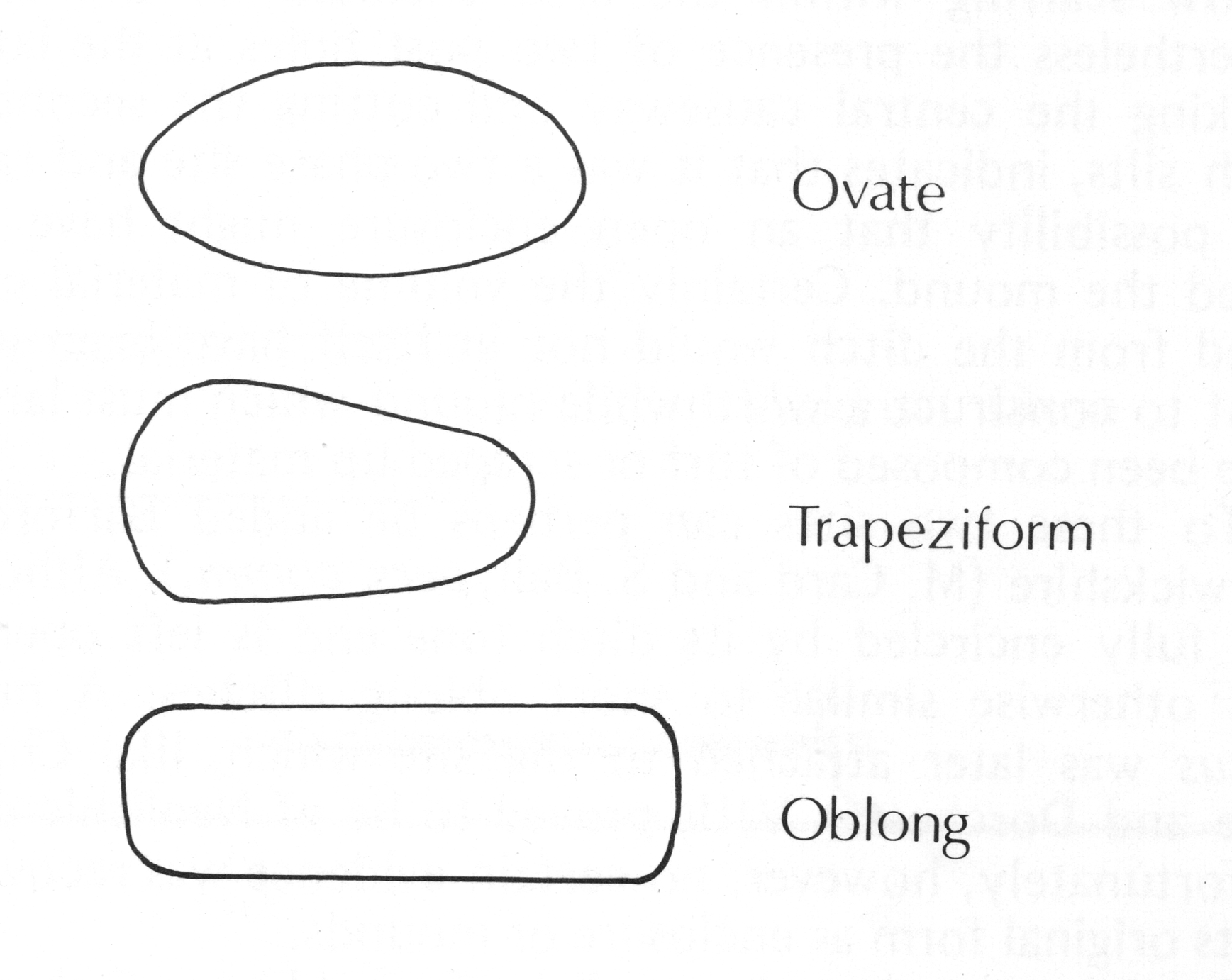

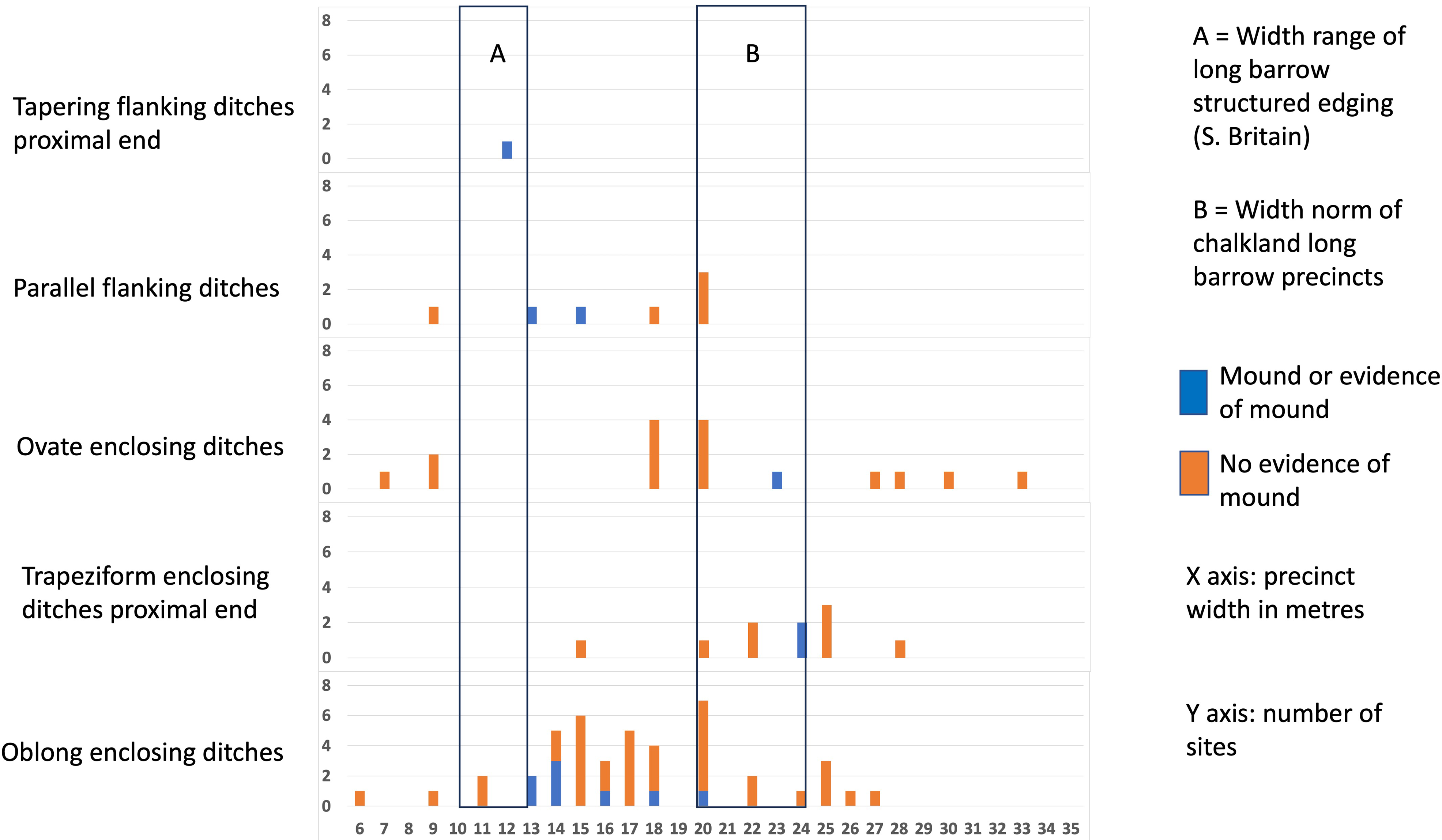

Site (precinct) dimensions

An unusual feature of the oblong series is the dominance of sites with precinct widths of 13–20 m (Figure 4), a significant contrast with the 20–24 m range recorded on the chalklands of southern England (Kinnes Reference Kinnes1992). It could be that mounds were narrower in the east of England. Yet where the edging features of presumed former mounds have been recognised they conform to the southern British norm centred around 10–12 m (Loveday Reference Loveday2020, tab. 7.1) (Table 1), whatever their outer ditch type. Mound width, it seems, was determined by a widespread concept (see Laporte Reference Laporte, Laporte and Scarre2016, 25), however approximately achieved. While narrower precinct widths in eastern England could record a different, open, enclosure tradition, they are repeated at West Rudham (16–17 m) and Ditchingham (c. 15 m), where they are accompanied by an absence of berms. These are usually about 3 m wide (Field Reference Field2006, 73–4), sufficient to explain the discrepancy. We discuss possible reasons for their omission below.

A small number of oblong sites exceed 20 m in precinct width (Figure 9), and most also exceed the 30–70 m length norm, often by a considerable margin (Tables 1 & 4). They could be classed as proto- or minor cursuses.

While distal widths of trapeziform cropmark sites broadly correspond to the oblong group norm, proximal dimensions (as recorded in Figure 9) are considerably greater. Ovate sites demonstrate some overlap with the other two groups, but are generally considerably wider, such as the Harpley long barrow, but more dramatically the Eye Kettleby enclosure of probable second millennium BC date (Finn Reference Finn2011). Record of a former c. 1.0 m raised interior at the 30 m wide Lawford A site is noteworthy (Buckley et al. Reference Buckley, Major and Milton1988, tab. 5).

Figure 9. Long enclosure precinct widths by morphological form.

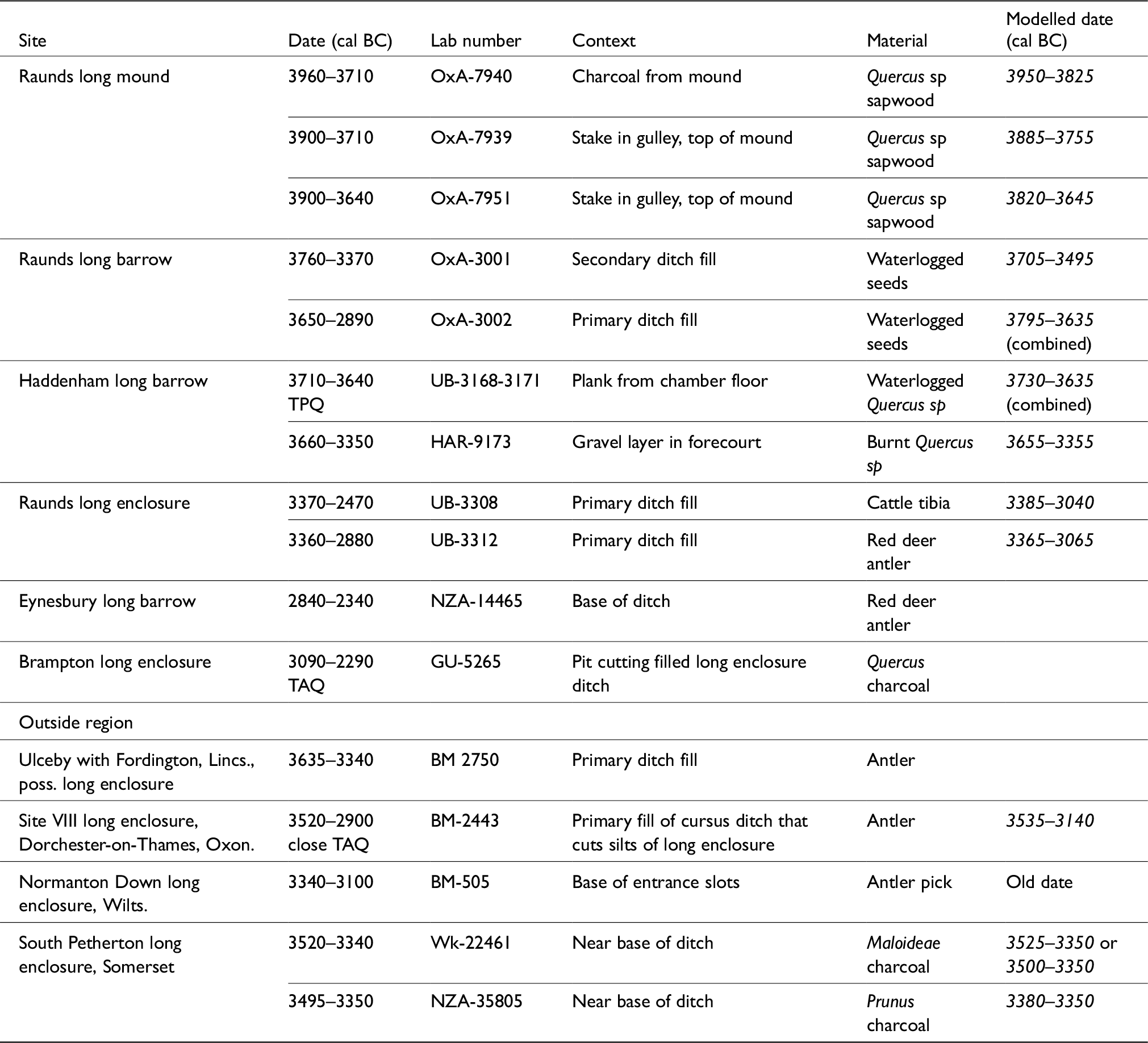

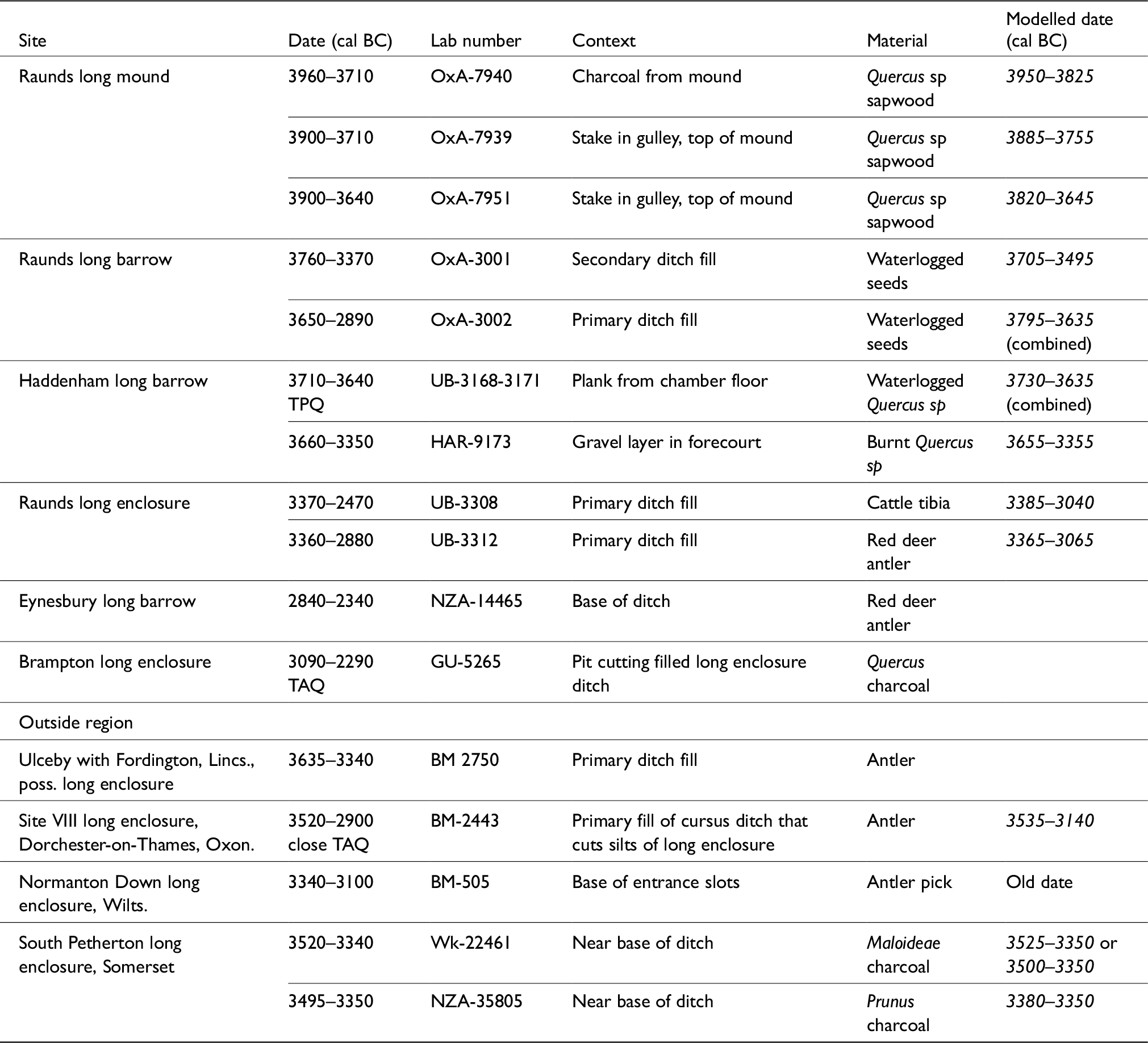

Table 5. Radiocarbon dates from long mound and long enclosure sites in eastern England, and wider comparanda (all from Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, except Ulceby (Jones Reference Jones1998, 106; Field Reference Field2006,172) and South Petherton (Mudd & Brett Reference Mudd and Brett2012)).

Ditch types

Overwhelmingly, crop mark long enclosures are delimited by moderate-sized ditches, c. 2–3 m wide, closely comparable to the excavated sample (Table 1) where recorded depths cluster between 0.5–1.5 m. Ditch widening is visible at Flore A and B, and at Swaffham Prior (cropmarks at the latter arguably degraded by agricultural erosion: RCHME 1972; Shell Reference Shell, Bewley and Raczkowsku2002), but typical quarry-like dimensions are only achieved at Pakenham, Eynesbury, and Ditchingham — the latter two of U-shaped plan. This corresponds with evidence from the neighbouring Lincolnshire Wolds where most sites had ditches 3 m wide or less, contrasting sharply with those of long barrows like Giants’ Hills I and II, and Hoe Hill (Jones Reference Jones1998; Drury & Allen Reference Drury and Allen2020). Amongst a clustering of slighter ditches (1–1.5 x 0.5 m), including ‘mound edging’ at Slough House Farm, several reveal evidence of posts at causeway butt ends, hinting at lighter removed/decayed intervening elements.

Pit lines set around 10 m apart within the Mount Bures parallel ditches, the Flixton long barrow and long enclosure, and Over long enclosure/minor cursus 2 (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Knopp and Strachan2002, fig. 4; Boulter Reference Boulter2019; Reference Boulter2022; Tabor Reference Tabor2023) link these disparate oblong sites through the common thread of long barrow-edging. But were real turf/scrape mounds being demarcated within these comparatively lightly ditched sites?

Earthwork reconstruction

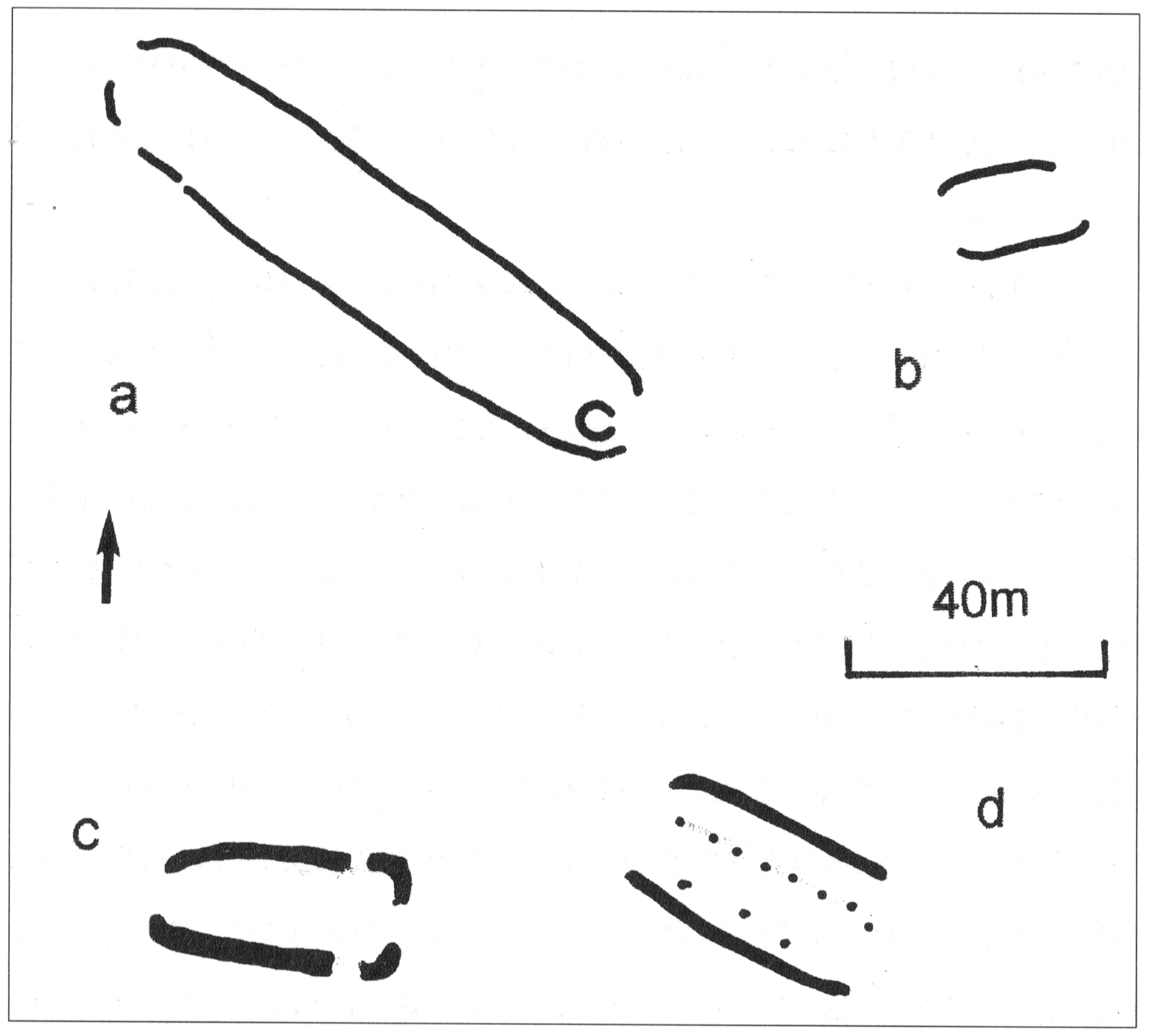

The geophysical surveys show a clear association of long barrows with enclosing ditches comparable to the aerial photograph record, yet bisection of Site VIII at Dorchester-on-Thames by the cursus ditch (Atkinson Reference Atkinson1951) leaves no doubt regarding its open nature. Elsewhere, evidence for open enclosures is, perhaps inevitably, scanty. Unlike former mounds disclosed by interruption of overlying features (eg, Charlecote, Claybush Hill, Ashwell, Long Melford B), banks offered little long-term resistance to plough erosion. Nor is ditch size a secure indicator: 1 x 0.5 m examples edged the 3 m high turf-built mound at Dalladies in Tayside, for example (Piggott Reference Piggott1972). That ditches of comparably moderate width demarcated both long enclosure and flanking parallel ditch sites (eg, Mount Bures) is particularly noteworthy, since the latter are improbable as embanked monuments (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Flanking ditch sites: a) Brampton; b) Sandy; c) Dedham; d) Mount Bures.

Nevertheless, the ditch defining an open enclosure at Weasenham was relatively slight (Table 1), although plough destruction there spanned decades rather than centuries (Peterson & Healy Reference Peterson, Healy and Lawson1986). At the long enclosure at Raunds (Harding & Healy Reference Harding and Healy2007), ditch size was comparable to West Rudham and Charlecote (Table 1); its claim to open status rests primarily upon its proximity (15 m) to a surviving long mound. Differential erosion cannot be entirely excluded though: the mound lay beneath the less intensively ploughed tofts of the Saxon village, while within the long enclosure ‘any shallow negative feature had been lost to later lowering of the ground surface’ (Harding & Healy Reference Harding and Healy2011, 104).

At Eynesbury, cropmarks revealed a U-plan quarry ditch interconnected with a long enclosure. This seemed to confirm Richard Atkinson’s (Reference Atkinson1951) hypothesised long enclosure to mound sequence, yet targeted excavation revealed no evidence of the ‘enclosure’ ditch having been cut. Rather, a series of pit-like recuts cut the primary levels of the quarry ditch (Ellis Reference Ellis2004; pers. comm.). Since these apparently extended the ‘long enclosure’ ditch alignment, we might conclude against expectations (but see R. Bradley Reference Bradley2007, fig. 2.21) that the quarry ditch was the slightly earlier element. Beyond the region, similar ditch reconfiguration is indicated by a jet slider of Middle Neolithic type just 0.60 m from the base of the shallow, eastern convex terminal ditch at Giants’ Hills I (Phillips Reference Phillips1936). If enclosing ditches had been pre-mound features, their spoil would not cover barrow surfaces, as at West Rudham, Haddenham, and Therfield Heath (Figure 10).

The problem may not be reduceable to a simple binary structural model, however. Excavation of an oblong site at Old Wolverton (‘cursus/long enclosure 4’), buried beneath alluvium, revealed protected buried soil in the middle of its western end and as patches along the inner edges of the ditches, from which gravel silting was recorded (Hogan Reference Hogan2013; pers. comm.). At Brampton a mound seems to have stood just within the west end of the, probably palisade-defined, long enclosure, while a small penannular site within its eastern end points to open accessibility (Malim Reference Malim1999; pers. comm.; French pers. comm.). Similarly, cropmark evidence of medieval windmill cross-trees axially located within the end of the Feering long enclosure indicate survival, and later utilisation, of a low mound (Buckley et al. Reference Buckley, Major and Milton1988, 89). These c. 20 m wide sites could be examples of expanded smaller mounds, encompassing a process of redefinition and perhaps even re-orientation.

Beyond morphology

Orientation

Oblong and ovate long enclosures rarely provide any hint of directionality. Focus on the eastern sector of the horizon has been assumed in Tables 1 and 3 based on evidence from excavated sites (C. Evans & Hodder Reference Evans and Hodder2006, fig. 3.73; Boulter Reference Boulter2022, fig. 3.2), but the West Rudham barrow is highest near its south-south-west end, and the Ditchingham long barrow and nearby Broome long enclosure widest at their westerly ends. North-easterly orientations dominate amongst securely identified long mounds and to a lesser extent amongst long enclosures, but regional tendencies are evident: broadly east–west in southern East Anglia, north–south in the western part of the region (eg, Charlecote, Stoke Hammond, Dodford). This may partly reflect topography: sites are often set broadly parallel to, but a variable distance back from, rivers or streams, suggesting alignment alongside terrace-edge routeways (cf. Raunds: Brown et al. Reference Brown, Knopp and Strachan2002, 18; Harding & Healy Reference Harding and Healy2007, 201). There is also a tendency for the longer sites to cluster around broad north–south axes, as beyond the region (eg, North Stoke, Oxfordshire; Long Low, Staffordshire). These sites often contrast in size and orientation with smaller sites in the same area, hinting at temporal or functional depth. Terminal form appears to have little significance.

Dating

The cleanliness of long enclosure ditches alongside their heavily eroded interiors renders dating extremely difficult, while potential problems of residuality bedevil turf construction (cf. long mound at Raunds (Chapman et al. Reference Chapman, Baker, Windell and Woodwiss2007, 62–4; Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, 301–3)). The meagre evidence is summarised in Tables 1 and 5.

Bearing these severe limitations in mind — and putting aside the anomalous date from Eynesbury — a sequence can nevertheless be suggested. The preferred date for the ditchless long mound at Raunds (3930–3770 cal BC; note that throughout the text, italics are used for statistically modelled date estimates) broadly precedes that of the quarry-ditched long barrow (3795–3635 cal BC). That in turn appears to predate construction of the ditched long mound extension to the small c. 3600 BC wooden-chambered mortuary mound at Haddenham (probably 3655–3355 cal BC). A closely similar date (3635–3340 cal BC) was returned by antler from the primary silts of a long enclosure at Ulceby, with Fordington in Lincolnshire broadly comparable in ditch plan to the Ditchingham long barrow (Jones 1988, 106; Field Reference Field2006, 172). These sites in turn precede the Raunds long enclosure (3350–2890 cal BC) (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, 288–91, 304, 310–13).

The concentration of Mildenhall Ware in the closed forecourt of the Haddenham long barrow, from which the dated material derived, points to a ceramic association (M. Knight & Shand Reference Knight and Shand2006, fig. 3.60). This is reinforced by placements at Flixton: a large part of a Mildenhall bowl on the ditch base in front of the ‘mortuary’ structure of a long barrow, and a complete bowl with a jet bead in a pit on the narrow lateral berm (Boulter Reference Boulter2022, 17, 21; Percival Reference Percival and Boulter2022, 67–9). These instances, coupled with occasional sherds from upper ditch levels at Rivenhall and Weasenham, seemingly tie Mildenhall Ware to the enclosing ditch series, but the possibility remains that the sherds on the ditch floor at Flixton arose from disturbance of a deposit placed, as at Haddenham, at the entry to the presumed mortuary structure. Such deposits may prefigure those associated with Peterborough Ware at Cotswold-Severn tombs (Ard & Darvill Reference Ard and Darvill2015).

Elsewhere, by contrast, dating of long enclosures points to the Middle Neolithic: the two statistically consistent dates from the primary silts of the long enclosure at Raunds (3360–2880 cal BC on antler, and 3360–2470 cal BC on cattle tibia) are comparable to those associated with Peterborough Ware from the ditch of a similar oblong site at South Petherton, Somerset (modelled 3380–3350 cal BC at 78%: Mudd & Brett Reference Mudd and Brett2012), and a date from the Normanton Down long ‘mortuary’ enclosure, Wiltshire (3340–3100 cal BC: Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, 199). Peterborough Ware was also found at unusually deep levels in the ditch at Charlecote (W. Ford Reference Ford2003), while at Dorchester VIII Atkinson (Reference Atkinson1951, 57) recorded that ‘[s]herds of Ebbsfleet-Peterborough type occurred in the later silting of the ditch only’ (see also Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Atkinson, Chambers and Thomas1992). Given the small size of the ditch (c. 2 x 0.6–0.9 m) and the mobility of the soils (0.76 m of silting recorded in just 13 weeks at Site IV: Atkinson et al. Reference Atkinson, Piggott and Sandar1951, 42), the time frame for accumulation seems likely to be one of decades rather than centuries.

At Flixton, initial findings from the attenuated long enclosure — 100 m distant from the long barrow and commonly aligned (cf. West Rudham and Harpley) — record Mildenhall Ware and Peterborough Ware occurring ‘seemingly often in the same fill’ (Boulter Reference Boulter2019, 63), attesting to continuity. The site has flattened rather than clearly convex terminals, as do all other sites dated to the Middle Neolithic except Normanton Down. This suggests A–B terminal form may have broad chronological application.

Secure dates are lacking for ovate enclosures in eastern England. The excavators of the Weasenham enclosure linked the 30 fire-cracked flints from its primary and secondary silts to the larger quantity on the old land surface under a neighbouring round barrow along with 350 sherds of European Beaker (Peterson & Healy Reference Peterson, Healy and Lawson1986, 80). If correct, whether residual or deriving from immediately post-construction activity, they would suggest a mid-third millennium BC date at the earliest. Plan equivalence to Beaker almond-shaped structures in northern France (Nicolas et al. Reference Nicholas, Ripoche and Gibson2019, 335–40) is noteworthy here. Ditch plan parallels beyond the region include the Latton Lands enclosure, Wiltshire (Powell et al. Reference Powell, Laws and Brown2009), dated 1820–1690 cal BC. The large enclosure at Eye Kettleby (Finn Reference Finn2011) strongly suggests that sites over 30 m in width might also be of second millennium BC date.

In sum, current, slim, evidence suggests rare, quarry-ditched and ditchless turf mounds in eastern England date to the Early Neolithic, oblong long enclosures from the end of the Early through the Middle Neolithic (probably changing from convex to squared ends across that time), and many ovate sites to the second millennium BC or later.

Implications and discussion

In eastern England, then, the morphological and dimensional correlation of cropmark long enclosures and long barrows (surviving or demonstrated by excavation) is clear. Whilst some of the cropmark sites may have been open enclosures, evidential balance — albeit weighted against minimal banks — points toward those of oblong and trapeziform type having defined former turf-built barrows. Thus, the answer to our initial research question is clear: the absence of long barrows is explained by their construction through a very different architectural tradition, one that emphasises turf. Indeed, given the manner in which we traditionally differentiate between earthen long barrows and chambered cairns, we might suggest a third tradition — turf long barrows — as well.

Yet issues remain. When we try to situate these sites in the wider southern British context, several questions with progressively larger implications arise.

-

1. Why is convex terminal plan (type A) the most common amongst surviving long barrows in eastern England?

-

2. Why do the West Rudham and Ditchingham barrows lack the berms seemingly fundamental to chalkland long barrows?

-

3. How can evidence of late dates be accommodated? Do long enclosures record an exceptionally late series of Middle Neolithic long barrows?

-

4. How do these sites link to open cursus monuments, which appear to be simple dimensional exaggerations of long enclosures?

-

5. Are there regional or Continental parallels that might be instructive?

While the first question could simply be a matter of isolated regional development, this still begs the question of origin. Where evidence of façades has been recovered in eastern England (Haddenham, Eynesbury, and quarry-ditched Raunds and Heybridge) they are straight. That, or concavity, is the norm. Defined convex ends are restricted to mound edging at the Beckhampton Road long barrow in Wiltshire and the U-shaped quarry ditch plans of Cranborne Chase (Ashbee et al. Reference Ashbee, Smith and Evans1979; Barrett et al. Reference Barrett, Bradley and Green1991). Derivation from convex-ended houses has been advanced to explain both long enclosure and cursus form (Loveday Reference Loveday2006a; J. Thomas Reference Thomas2006), but houses of that plan are rare even in Scotland and Northern Ireland (Brophy Reference Brophy2007; Smyth Reference Smyth2014), and absent from southern Britain (Barclay & Harris Reference Barclay and Harris2017; Bullmore Reference Bullmore2024). An alternative source lies in gable end collapse, a mechanism suggested by Chris Evans and Ian Hodder (Reference Evans and Hodder2006, 75–6, 88) for the complex convex deposits fronting the façade at the Haddenham long barrow. This may also apply for the ditchless turf mound at Raunds and convexity is a familiar feature of spread mounds more widely (eg, RCHME 1979a). Evans and Hodder (Reference Evans and Hodder2006, 201) suggested that the post-collapse appearance of such mounds may have inspired subsequent convex-ended barrow/long enclosure forms. While this accords well with the mid to late fourth millennium BC dates of long enclosures, these sites are mostly of square-ended plan. Neither does it answer why Early Neolithic long barrows are largely absent from the region. Flanking ditch sites (generally with ditches of ‘moderate width’ rather than ‘quarry’ type) are still very few (Table 4, Figure 10). Additionally, the surviving mounds within convex-ended enclosing ditches at West Rudham, Ditchingham, and Therfield Heath are of ‘classic’ type, very different to small mounds like Harpley that often characterise late long barrows (Drewett Reference Drewett1975; but see Kinnes Reference Kinnes1992, 72; Roberts et al. Reference Roberts and Wortley2018, section 5.3).

Rather than a very late flowering of long barrow construction in the region, might an answer lie in the lack of berms noted at West Rudham and Ditchingham? At the former, Hogg (Reference Hogg1940, 320–1) records: ‘No berm was left, and the surface of the mound and inner edge of the ditch must have formed a continuous convex surface’ (Figure 11). This, coupled with the fact that the mound was some 16–17 m wide — considerably beyond the 10–12 m range of structured mounds — suggests that the ditch, from which the capping material came, was dug after the turf-built mound had weathered and spread. That was also postulated at Haddenham (C. Evans & Hodder Reference Evans and Hodder2006, 74), where it was determined that capping material could only have derived from the deeper digging of the ditch potentially at a later phase. There, however, it seems the façade was still upstanding at that point, so the ditch was aligned to respect it; with fully spread mounds such redefining ditches are likely to have been convex at the extremities. Outside the region the small, late long barrow at Radley, Oxfordshire (R. Bradley Reference Bradley1992), with its double ditch circuit may demonstrate the process: its inner, square-ended ditch representing original mound structuring (achieved with turf elsewhere, cf. Holdenhurst: Piggott Reference Piggott1937), the convex-ended outer ditch, dated to the end of the fourth millennium BC (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, fig 8.29), acting as a redefinition of the spread monument.

Figure 11. West Rudham: excavated cross-sections (Hogg Reference Hogg1940, fig. 2), reproduced curtesy of the Norfolk and Norwich Archaeological Society. Scale in feet. Note: gravel from the ditch running up onto the disturbed barrow, not placed as a pre-mound enclosure bank.

Absence of berms may reveal more than simply late-stage ditch digging. Normal berm width — in the region of 3 m — exceeds the structural need to avoid mounds weathering into ditches. This suggests instead the requirement of access to barrow perimeters, most plausibly for ritual purposes (Field Reference Field2006, 73–4). Close enclosure and capping, by contrast, suggests closure, or at least containment, of earlier ditchless turf mounds like the fortuitously preserved example at Raunds; lack of clear directional silting at West Rudham and Flixton certainly points to stabilised mounds. Such referencing/delimiting imperatives accord with wider patterns of Peterborough Ware placement at earlier sites (Ard & Darvill Reference Ard and Darvill2015) and restructuring, albeit in ovate form, at Horton (S. Ford & Pine Reference Ford, Pine and Preston2003).

Instead of the pre-mound definition of a funerary enclosure (Atkinson Reference Atkinson1951), long enclosure construction would be an exceptional process of later architectural addition. Arising perhaps ad hoc, to refurbish spread mounds or to isolate them, ditch plans could have become increasingly formalised by repetition to emerge as an entity in their own right. Vicki Cummings and Colin Richards’ (Reference Cummings and Richards2017, 238) concept of architectural wrapping is of importance in furnishing a rationale and mechanism. ‘Wrapping’ of martyrs’ tombs by Constantinian basilicas records how external additions to ritual sites can generate new forms in which earlier core elements are reduced to symbolical expressions. Progressive formalisation of long enclosure ditches around spread mounds likely traces their emergence as an independent symbolic signifier — a sacromorph — that could be expanded, according to societal circumstance, to less tightly enclose its focal site.

That process might explain the combination of axial mounds and distanced long enclosure edging at Old Wolverton 4 and Brampton (banks at the former; presumed fencing at the latter: Hogan Reference Hogan2013; pers. comm.; Malim Reference Malim1999; pers. comm.). Feering and the much larger (90 x 40 m) Copley Hill, Babraham, Cambridgeshire (CUC BFC 69–70), seem to be further examples. Similarly, recent work at Over, Cambridgeshire (Tabor Reference Tabor2023), has revealed stake fence lines set c. 10 m apart (the ‘standard’ width of long mound edging) within a seemingly exaggerated long enclosure/minor cursus (90 x 28 m).

Questions remain, nonetheless, regarding the drivers of such a hypothesised regional development. Redefinition of earlier long mound sites, as against ‘respectful’ deposition in ditches or forecourts elsewhere, appears all but unique; even more so the emergence of the form as an independent sacromorph, refined and expanded to cursus dimensions (eg, Feering, Stratford St Mary, Fornham All Saints). Additionally, we should ask why such development was restricted to nationally less common oblong mounds.

With the exception of the Lincolnshire Wolds, where concave forecourts and enclosing ditches point to mixed northern and southern influences (J. Evans & Simpson Reference Evans and Simpson1991; Jones Reference Jones1998; Drury & Allen Reference Drury and Allen2020), these elements contrast markedly with neighbouring regions; oblong enclosures are comparatively rare amongst the mixed traditions of the Thames Valley (Loveday Reference Loveday1985; Hey & Barclay Reference Hey, Barclay, Morigi, Schreve, White, Hey, Garwood, Robinson, Barclay and Bradley2011). This hints at wider influence. As noted above, framing of earlier ‘halls’ has been advanced to explain the genesis of convex-ended cursuses in Scotland (Loveday Reference Loveday2006b; J. Thomas Reference Thomas2006; Brophy Reference Brophy2016), but this tradition seems independent of long barrows and much earlier. Across the Channel, convex-ended elongated form characterised the reframed Passy-type monuments of northern France, but comparative irregularity of ditch definition coupled with early to mid fifth millennium BC dates again makes them unlikely sources (Kinnes Reference Kinnes1999; Chambon Reference Chambon2020).

The process of framing perhaps finds closest echo amongst Danish long mounds: monuments of modest height, overwhelmingly rectangular plan, and commonly 9–10 m wide (Midgley Reference Midgley1985, tab. 2e, 85–91, fig. 20). Storgård IV exemplifies the type: a turf-built mound flanked by shallow non-functional ditches. After the latter had silted up, the mound was framed some 2–3 m out by a palisade enclosing just a very thin layer of sand and gravel (Kristensen Reference Kristensen1989). While the structural sequence immediately recalls Wayland’s Smithy I and II, in having a minimally mounded second phase it more closely resembles Old Wolverton long enclosure/cursus 4 (Hogan Reference Hogan2013; pers. comm.).

Although most Danish sites have squared ends (Midgely Reference Midgley1985), two convex-ended sites in the environs of the Sarup causewayed enclosures may be significant. Sarup Gamle Skole A4 was a convex-ended palisade 58 x 7–11 m in size that enclosed a small dolmen. It is dated c. 3400 BC by Fuchsberg pottery placed against its side (Andersen Reference Andersen, Laporte and Scarre2016, 130–1). Sarup Frydenlund structure B is a smaller (30 x 8 m) convex-ended palisaded site that closely resembles the long enclosure at Brampton (Malim Reference Malim1999). It framed a former Mossby-type house (12 x 6 m) with a burial between its aisle posts. Dating of the complex is insecure but probably mid fourth millennium BC (Andersen Reference Andersen, Brink, Hydén, Jennbert, Larsson and Olausson2015a). Since neither site produced evidence of either a former mound or associated quarry sources, they have been assigned to the so-called Barkaer or Neidzwiedz groups (Rzepecki Reference Rzepecki2011; Andersen Reference Andersen, Brink, Hydén, Jennbert, Larsson and Olausson2015a), structures of diverse plan likely to represent the structural edging of regionally varied, ploughed-out turf/scrape long barrows, rather than open monuments. Like Storgård IV they likely ‘framed’ earlier structures within minimal mounds. Such reconfiguration was the driving mechanism behind monument histories in the region, as confirmed by close dating of the monument at Flintbek: eleven phases of activity, within three successive ‘frames’, enacted almost wholly within the 35th century cal BC (Mischka Reference Mischka2011; Whittle Reference Whittle2018, 119–22). Unlike the major structural transformations witnessed elsewhere (eg, Notgrove, Sales Lot, Ty Isaf: Darvill Reference Darvill2004, 62–70; Prissé-la-Charrière: Laporte Reference Laporte, Laporte and Scarre2016), reconfiguration on the Danish pattern seems to be largely metaphorical. Just such concepts seem to echo through the broadly contemporaneous evidence from eastern England, whether in the form of ditches closely set to spread mounds as at West Rudham, distanced and extended as at Old Wolverton 4, or by palisades as at Brampton. Might the ultimate origin for convex-ended form then lie in lightly built, probably turf-jacketed, Mossby-type houses (Loveday Reference Loveday2006b; Larsson Reference Larsson, Debert, Larsson and Thomas2016), a type unlikely to survive intensive cultivation in eastern England?

The potential transmission of ideas and practices across the North Sea may also find support in the scatter of Scandinavian axes across eastern England and the lower Thames Valley (Walker Reference Walker and Müller2010; Reference Walker2018), the introduction of transverse arrowheads (Cleal Reference Cleal, Jones, Pollard, Allen and Gardiner2012), and the adoption of novel artefacts with possible continental antecedents (Loveday Reference Loveday, Brophy and Barclay2009). A shared preference for vertically incised pottery is also notable: Satrup, Fuchsberg, Virum (Müller & Peterson Reference Müller and Peterson2015, 576–7), Mildenhall (J. Clark et al. Reference Clark, Higgs and Longworth1960). Further dating on both sides of the divide is required to test credibility, but the atypically late dates for the causewayed enclosures at Orsett and Haddenham, both defined by close-set ditch circuits in the contemporary Danish idiom, command attention (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011; Andersen Reference Andersen2015b, fig. 42.2).

Whether the distinctive convex-ended oblong series results from formalisation of ad hoc regional demarcation or is a conceptual import from Scotland or across the North Sea, we must avoid a unitary explanation for the region’s long enclosures, a fact underscored by the parallel series of square-ended (B type) sites. Significant difference in causeway placement strongly suggests real difference of origin and/or function. Association of the opposed types at several Barford-like groupings of small cursus sites (Loveday Reference Loveday and Gibson1989) could signal choice on the part of the builders, but spatial arrangements often suggest that convex-ended long enclosures were the focal element (eg, Stratford St Mary, Springfield). This is stratigraphically confirmed at Old Wolverton and underscored by the centrality of type A cursus sites to the great complexes at Fornham All Saints, Maxey, and most strikingly, Dorchester-on-Thames. The subsequent multiplicity of Bi type — long enclosures to cursuses — across the region points to a changed dynamic (Loveday Reference Loveday1999; Reference Loveday, Barnwell and Darvill2023).

Conclusion

The geophysical surveys reported here have demonstrated near 100% association of surviving eastern long barrows with convex-ended enclosing ditches; their absence at Pitsford might suggest it is an outlying cairn of the Cotswold-Severn series (cf. Whitwell, Derbyshire; Vyner & Wall Reference Vyner and Wall2011). The balance of probability therefore is that most comparable cropmark, convex-ended long enclosures record missing long barrows.

The unifying feature of mounding small Early Neolithic mortuary structures in the region — whether long as at Haddenham, or round as at Orton Meadows or Trumpington (C. Evans et al. Reference Evans, Lucy and Patten2018, 82) — is an almost total absence of quarry ditches. Even rare, separate flanking ditches of classic plan occur more often as moderate defining elements than as full-scale quarries (Tables 1, 4, Figure 10). This reflects choice of materials: turf rather than structurally mobile sands and gravels. Just as ditch size amongst round barrows need not influence mound size when turf was employed (cf. Corcoran Reference Corcoran1963), there is no reason to assume a ditch size to mound size correlation in the long ‘enclosure’ series, as the neighbouring surviving long barrows at West Rudham and Harpley demonstrate. Evidence from Haddenham and West Rudham, suggesting that ditches were later, re-delineation features for ditchless turf barrows, helps us understand the form’s subsequent magnification as an independent Middle Neolithic entity — the open, or symbolically mounded, long enclosure/cursus.

Monument dimensions instead appear critical: sites under about 20 m in precinct width were likely former long barrows, wider sites in the oblong series greatly enlarged symbolic framing structures. Thus, rather than two parallel traditions of turf-built barrows and long enclosures, monuments reveal different moments of making and remaking, and perhaps through this process paved the way for the emergence of a new form of architecture: cursus monuments.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ppr.2025.10072

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to estate owners and their tenants for permission to carry out the surveys, to David Robertson, Michael Gill, Charly French, Frances Healy, and Jonathan Last for advice, to Emily Banfield, Stu Eve, and Dom Escott for assistance with the work, and to the Universities of Leicester and Winchester for loan of their equipment. We are particularly grateful to the Prehistoric Society for their award of a research grant, without which the work could not have been undertaken. The text here has been greatly improved by the comments of the editors and three anonymous peer reviewers.