Introduction

The dominant conceptual model behind many behavioral interventions such as nudges and choice architecture is consequentialist, in which successful top-down outcomes are presumed to adhere to individuals’ stated preferences and result in more rational behavior (Kuehnhanss, Reference Kuehnhanss2019). More recently, however, calls for increased attention to heterogeneity have recognized that this view often fails to address variances and instability of context that can lead to seemingly inconsistent, but genuinely held, preferences during judgment and decision-making (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Tipton and Yeager2021). In addition, the emphasis on pursuing rational outcomes unmoored from context can encourage a paternalistic ‘view from nowhere’ approach to policy that fails to reflect a true plurality of values (Schmidt and Stenger, Reference Schmidt and Stenger2021; Diener et al., Reference Diener, Northcott, Zyphur and West2022).

These issues have lent credence to an alternative contractarian model, which conceptualizes decision-making more as an activity of exchange within established social institutions imbued with communally shared legitimacy: a conceptual marketplace that enables participants to pursue opportunity and freely satisfy their individual values and fluid preferences (Sugden, Reference Sugden2018). However, this approach is predicated on the assumption that all comers have faith in the institutional legitimacy of this marketplace or can participate equally, a view that can overlook instances of double-bind tradeoffs and valid reasons for self-imposed exclusion, and which therefore presents its own limitations.

This indicates behavioral public policy (BPP) would benefit from considering an alternative approach to consequentialist paternalistic tendencies and contractarian presumptions of equal access, acceptance and participation in a marketplace of exchange. In this paper, we propose a dialogical mindset and approach – which suggests that behavioral approaches to policy must not just satisfy a plurality of values, but also a plurality of frames that inform what choices seem viable or preferable and what outcomes qualify as successful – as such an alternative. This view prioritizes discursive reflection to elicit excluded perspectives of those on the traditional receiving end of policy as well as non-traditional collaborators, countering tendencies toward ‘othering’ with the good-faith pursuit of understanding alternative perspectives. On behalf of policy recipients, this also suggests promoting a behavioral justice lens that supports a broader range of potential frames, recognizing the existence of varied ‘or/rationalities’ in place of the false binary of rational vs irrational choice. For policy-making partners, we posit that employing dialogism in the form of behavioral boundary objects both laterally (cross-disciplinarily) and bottom-up (across policy recipients and experts) during problem framing and solution development can support more effective collaboration during solution development.

A behavioral starting point: the consequentialist model for welfare economics

Traditions of normative economics presume that decision-making and actions in pursuit of well-being are driven by the deliberate application of clearly held preferences, characterized by stability (persistence and immutability), context-independence (disconnection from circumstance or presentation), internal consistency (adherence to the transitive property of preferences) and non-tuistic qualities (driven by personal self-interest) if they are to be considered rational (Sugden, Reference Sugden2018). The emergence of behavioral science has called this view into question, upending assumptions of context-independence and consistency by demonstrating that how choices are framed can radically alter how they are perceived and acted upon, that preferred choices may vary from setting to setting, and further that differences in choice-making conditions may result in preferences that stray from expected transitive properties (Whitman and Rizzo, Reference Whitman and Rizzo2015; Rizzo and Whitman, Reference Rizzo and Whitman2019). The assumption that preferences are stable has also proven questionable given numerous time-based distortions surfaced by behavioral research. For example, subjective reports and judgments of utility have been shown to be inconsistent across past, present and future timescales (Kahneman et al., Reference Kahneman, Wakker and Sarin1997; Hausman, Reference Hausman2015; Oliver, Reference Oliver2017), resulting in tensions between planner/doer motive and actions, and a general inability to recognize the degree to which our personal preferences will change or persist over time (Quoidbach et al., Reference Quoidbach, Gilbert and Wilson2013).

Specific behavioral strategies to address these findings in the form of asymmetric or libertarian paternalistic interventions such as nudges and choice architecture are by now familiar across international policy and civic contexts (Camerer et al., Reference Camerer, Issacharoff, Loewenstein, O'Donoghue and Rabin2003; OECD, 2017). In general, these consequentialist strategies work by redesigning choice environments to correct for the fact that individuals’ cognitive heuristics systematically introduce bias into deliberative judgment. More recently, tactics known as ‘boosts’ have served a complementary and less overtly paternalistic role by bolstering individuals’ internal decision-making and increasing their ability to act more reflectively, rather than simply correcting for the perceived inadequacies of their internal heuristics (Hertwig and Grüne-Yanoff, Reference Hertwig and Grüne-Yanoff2017). Where nudges require at least a reasonable guess at a rational preference to inform intervention design, boosts elide this issue somewhat by cultivating decision-making capabilities rather than optimizing for a specific decision-making moment (Grüne-Yanoff and Hertwig, Reference Grüne-Yanoff and Hertwig2016).

Although differing in their approaches and mechanics, both nudges and boosts have historically been motivated by aligning actual behaviors with the subject's preferred choice while preserving autonomy and free will (Hertwig and Grüne-Yanoff, Reference Hertwig and Grüne-Yanoff2017). In addition, while both approaches recognize that specific preferences may vary, they also presume that preferred choices in support of personal well-being are aligned with classic notions and normative standards of economic rationality. This reflects an intention to deliver significant benefits to those who would otherwise choose poorly (i.e., non-rationally) while imposing minimum harm or hassle for rational actors (Camerer et al., Reference Camerer, Issacharoff, Loewenstein, O'Donoghue and Rabin2003; Loewenstein et al., Reference Loewenstein, Brennan and Volpp2007). Regardless of method, in other words, the goal of consequentialist policy is predominantly focused on helping people maximize their capacity to act rationally in order to improve their well-being (Grüne-Yanoff and Hertwig, Reference Grüne-Yanoff and Hertwig2016; Kuehnhanss, Reference Kuehnhanss2019).

Limitations of the consequentialist approach

However, centering on preferences creates several issues. Preferences are notoriously slippery and difficult to determine with any confidence (Slovic, Reference Slovic1995; Loewenstein and Haisley, Reference Loewenstein and Haisley2007), and efforts to isolate and purify true preferences tend to strip out the noisy hard parts and oversimplify predilections (Infante et al., Reference Infante, Lecouteux and Sugden2016). The expectation that preferences can always be confidently determined also presumes that decision-making is always rigidly deliberative, whereas perceived inconsistencies might simply reflect contextual variation or the improvisational nature of decision-making under certain circumstances (Chater, Reference Chater2022). Finally, a recurrent challenge with taking a consequentialist approach to preference lies in using individuals as the unit of decision-making and preference satisfaction. While this makes good sense from a practical or intervention-level standpoint, the implication that aggregating individual-level preferences satisfaction will naturally ladder up to communal well-being strains credibility in practice (Chater, Reference Chater2022).

Despite professing to support free will and agency, policy interventions that employ choice architecture also cannot avoid positioning the policymaker as a benevolent social planner whose view of outcomes and desired competencies (e.g., greater financial literacy, the importance of adhering to a healthcare regimen) shape which choices are available or set as defaults (Sugden, Reference Sugden2013). As a result, the position taken by the policymaker may or may not be shared by the policy recipient or may asymmetrically reward some participants over others, and subsequently may interfere with satisfying a full plurality of value and personal preference even when target behaviors or outcomes seem non-controversial. For example, in focusing on rebates as the policy instrument, the U.S.'s Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 may asymmetrically benefit wealthier homeowners who can finance home improvements despite its explicit intent to target lower- and middle-income populations, who are more likely to rent. Finally, while normative behavioral economics tackles issues of consistency, context-dependence and stability, the non-tuistic principle of classical economics – in which individual self-interest is presumed to be the primary driver for decision-making – demands greater attention. The notion of choosing in one's own best interest still looms large, for example, in suggestions that adopting nudges will ‘make choosers better off, as judged by themselves’ (Thaler and Sunstein, Reference Thaler and Sunstein2009, p. 5).

A potential alternative: The contractarian approach

To combat the paternalistic, preference-based policymaker-as-benevolent-planner and satisfy a greater plurality of value, some have proposed contractarianism as an attractive alternative model (Oliver, Reference Oliver2017; Chater, Reference Chater2022). Rather than attempting to tackle the fool's errand of construing preferences, contractarianism suggests that a plurality of values can be better satisfied through a marketplace of agreed-upon and mutually advantageous rules within trusted social institutions in the form of a ‘community of advantage’ (Sugden, Reference Sugden2018). In this model, a shared belief in established communal values grounds exchanges as a kind of social contract with the material conditions, commitment and consent of those with whom they conduct those exchanges (Hobbes, Reference Hobbes1914; Buchanan, Reference Buchanan1964). In place of consequentialism's view from nowhere, in which policy-making authority sits outside and agnostic of the decision-making context and stakes, contractarianism positions policy as a means to enhance and cultivate opportunity from within based on bonds of trust in other participants and in the market's ability to support mutually beneficial exchanges (Sugden, Reference Sugden2018). This sidesteps the need to define preferences or presume individuals’ welfare requirements, and instead positions participants’ free will to pursue personally relevant choices as the mark of market success (Hayek, Reference Hayek1945; Sugden, Reference Sugden2018). Allowances for farmers markets in urban environments, for example, provide new avenues for exchange that directly benefit both individual producers and consumers, while also adhering to municipal values such as public health and safety and increasing civic good (Project for Public Spaces, 2020).

However, while the notion of this marketplace of opportunity to support mutually beneficial exchange sounds promising as a counterpoint to top-down paternalism and a means to satisfy a plurality of values, the contractarian view also has limitations. While maximizing opportunity sounds desirable, for example, it can remain detached from actual or eventual well-being (Hausman, Reference Hausman2022). Perhaps more worryingly, however, this notion of shared belief and institutional legitimacy assumes that social institutions in question are indeed seen as legitimate, despite data that indicate trust in government are far from assured (OECD, 2022) and that perceptions of institutional validity often become strained as populations become politically polarized (Carothers and O'Donohue, Reference Carothers and O'Donohue2019). Further still, even social institutions that are widely seen as credible or neutral are often built upon ideological conventions that advantage certain people, perspectives and choices over others (Harding, Reference Harding1992; Bone, Reference Bone2003). In summary, power – both in terms of who does policy-making and who has proximity to policymakers – can embed bias (Buchanan and Tullock, Reference Buchanan and Tullock1962).

This can take several forms. For example, institutional rules of engagement are often the result of normalized characteristics that are not merely WEIRD (western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic (Henrich et al., Reference Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan2010)) but also frequently white, heteronormative, ableist and male, which contributes to the continued overrepresentation of a narrow group and an implicit reference point for defining normalcy (Wynter, Reference Wynter2003). This absence of alternative perspectives and lack of data on ‘other’ groups also tends to result in data-driven conclusions that confirm traditional norms and power dynamics, resulting in asymmetrical treatment that nevertheless appears objective. Examples abound in healthcare policy, as when Black people are judged by white dermatological standards (Ebede and Papier, Reference Ebede and Papier2006), Black patients are assumed to have higher pain tolerance than white patients (Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Trawalter, Axt and Oliver2016), and women's tendencies to experience heart attack symptoms that don't jibe with public service announcements emphasizing chest pain puts them at higher risk (Canto et al., Reference Canto, Goldberg, Hand, Bonow, Sopko, Pepine and Long2007). Interrogating these presumptions that institutions are universally seen as legitimate or equipped to provide equal access, acceptance and standing within marketplace communities is therefore both essential and urgent.

Even when non-conforming individuals or populations persist in attempts to engage in market activities, they often face barriers to participation in the form of pressure to subvert their true selves or interests, as when women and minoritized individuals feel obliged to tone down personal presentations such as gray and/or Black hair to pass muster (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Karl and Peluchette2019; Cecil et al., Reference Cecil, Pendry, Salvatore, Mycroft and Kurz2022) or when women feel compelled to demonstrate nurturing characteristics that are not expected of their male counterparts (Eagly and Karau, Reference Eagly and Karau2002). This effort can be further compounded by the need to continually respond to others’ preconceptions of one's status or role, such as presumptions that women are assistants or that Black or brown individuals cannot be doctors (Clair et al., Reference Clair, Humberd, Caruso and Roberts2012). Countering these presumptions and microaggressions can be incrementally minor but collectively exhausting, particularly when accompanied by advice that addressing them is a question of personal accountability rather than recognizing how systemic norms and structures reinforce asymmetric expectations (Cialdini and Trost, Reference Cialdini, Trost, Gilbert, Fiske and Lindzey1998). As a result, individuals who deviate from presumed norms often have to pay a form of emotional ‘market tax’ simply to access the opportunities promised by the community of advantage (Kuehnhanss, Reference Kuehnhanss2019). These examples demonstrate the legitimization and limitation of power in the status quo, showing how existing approaches are fundamentally non-consensual (Meadowcroft, Reference Meadowcroft2014); taken to an extreme, the cost of entry to pursue so-called rational ends and goals – as defined by those who pay no such tax – may seem both logistically and psychologically prohibitive. In addition, while some have recognized the entrepreneurial urge naturally present in the marketplace of opportunity as a means to cultivate an understanding of diverse values and needs of consumers and producers (Lavoie, Reference Lavoie, Grube and Storr2015), this view does not recognize that some – perhaps by choice – remain excluded from participation altogether; as such, a marketplace that is well equipped to address a plurality of value may not be sufficient to recognize a plurality of frames.

Frame plurality

All this suggests that evaluating choice is not just context- or value-dependent, but frame-dependent; while contractarianism ably accommodates a plurality of values, it may not sufficiently account for the fact that individuals perceive choice situations and weigh options through very distinct and endogenous conceptual schemas, and further that these frames determine how individuals perceive and act on options (Cooper, Reference Cooper1988; Schön and Rein, Reference Schön and Rein1995; Bacharach, Reference Bacharach2006). Given that these different frames may limit the perceived – if not actual – availability of options and opportunities to act, this presents a counterpoint to contractarianism's implicit presumption that satisfying a diverse range of values is sufficient to address decision-making in complex environments (Ewert, Reference Ewert2019).

Personal frames represent the ‘sets of descriptions that players use to represent the problem to themselves’ (Bacharach, Reference Bacharach2006, xvi), through which people perceive and make sense of their own experiences. This notion reinforces Schön and Rein's insight that different frames do not simply suggest different interpretations about what to do, but constitute different mental models about the very nature of things, and therefore even what might qualify as a problem in the first place (Schön and Rein, Reference Schön and Rein1995). While frames may be informed by lenses of gender, race and ethnicity, they can also take other less obvious forms that reflect different versions of reality seen through a range of functional (e.g., being a lefty in a world built for the right-handed), circumstantial (e.g., first-generation university students) or disciplinary worldviews. As a result, people with different frames may experience the same situation or policy radically differently; for example, data collection that may seem beneficial, or at worst benign, by privileged populations who see it as a route to personalization may be perceived or experienced as surveillance by more vulnerable audiences who worry how that data might be used against them (Madden et al., Reference Madden, Gilman, Levy and Marwick2017).

As such, frames do not merely shape what options we might prefer but limit our ability to conceptualize what is even possible in ways that constrain our capacity and well-meaning efforts to fully conceive of others’ contexts of choice. For example, women seeking professional advancement are frequently required to internalize or modify their natural behavioral or personal inclinations to adopt more acceptable – traditionally ‘masculine’ – postures. However, adopting these modifications still often fails to achieve inclusion by male peers (Naoum et al., Reference Naoum, Harris, Rizzuto and Egbu2020); in addition, substantial evidence that taking advice to negotiate like a man, presented as a path to achieve greater gender parity, can instead result in backlash (Dannals et al., Reference Dannals, Zlatev, Halevy and Neale2021) only amplifies this double-bind. Playing by the rules therefore either forces women to expend extra investment with little guarantee of success or opt out by behaving ‘irrationally’ (e.g., not negotiating or pursuing promotions) from the perspective of men who face no such market tax.

In other words, while welfare economists’ views on which characteristics qualify as irrelevant are presumed to be non-controversial, and simply a means to reduce decision-making distractions that contribute to reasoning errors (Infante et al., Reference Infante, Lecouteux and Sugden2016), what qualifies as irrelevant may be naturally inconsistent across different frames. Further still, the expectation that actions like pursuing promotions are incontrovertibly appealing fails to reflect that the societally dominant frame of movin’ on up is not necessarily universal. For example, while recent research indicating that opt-out mechanisms – such as automatically entering women into competitive contexts rather than relying on self-promotion – can demonstrably reduce gender disparities is undeniably good news (He et al., Reference He, Kang and Lacetera2022), these positive results remain predicated on the presumption that traditional notions of success, like promotion and managerial advancement, are de facto desirable.

As such, accepting that different frames contribute to substantially different perspectives on judgment and choice-making also requires recognizing how actions that seem misguided from the outside may be fully coherent to the person acting. In extreme cases, people may intentionally remove themselves from participation in marketplaces altogether to reduce their perceived risk of harm, leading to further inequity. Women's choice to disengage from social media during Gamergate, for example, may have seemed an overreaction to men who did not face the same vitriol or threats of violence (Massanari, Reference Massanari2017) but their self-imposed removal only amplified the imbalance of whose voice is heard or considered valid.

The fact that behavioral interventions are typically designed to encourage conventionally rational behaviors, rather than considering alternative perspectives about what makes sense given a wider range of frames and lived experiences, presents several challenges for BPP. The recognition that policymakers and policy designers tend to represent a fairly narrow segment of lived experiences is not new; while more participatory processes may encourage the inclusion of more diverse frames, traditional policy-making models that prioritize expert knowledge may still rely on outdated or limited conceptions of rational behavior. For example, assuming that the underbanked do not take advantage of certain financial offerings because they are not sufficiently thoughtful about their long-term solvency may overlook that the reality of their situation demands the use of different – but not irrational – rules of thumb (Bertrand et al., Reference Bertrand, Mullainathan and Shafir2006).

In addition, evidence-based practice may not include frames that are deprioritized or missing from the official record, leading to incomplete reflections of lived experience. For example, data that capture job loss or departures from academia obfuscate women's higher tendencies toward ‘presenteeism’ – showing up but performing only the required minimum, sometimes as a means to retain employment benefits – or downstream implications on promotion and tenure given decreased authorial productivity during Covid-19 (Yavorsky et al., Reference Yavorsky, Qian and Sargent2021). In other words, while job data continue to be useful, they are incomplete unless the operational frames that shape judgment and decision-making – such as the need to prioritize insurance benefits or recognizing that the burden of childcare often falls to women – are also considered.

Proposing a dialogical approach: behavioral justice and collaborative engagement

Addressing frame plurality is therefore likely to benefit from an approach that sidesteps both consequentialist paternalistic tendencies and potentially questionable assumptions of equal access and participation in contractarianism's social institutions. A dialogic ethic and mindset, capable of supporting varied conceptual frames to inform more equitable market conditions, presents one such alternative by allowing a wider set of populations to flourish within a context that is just for all rather than advantageous for some.

Both consequentialism's qualified paternalism, with its pursuit of well-defined preference and rational behavior, and contractarianism's somewhat patriarchal notions of faith in structured social institutions and self-interested competition are firmly grounded in individualist, traditionally masculine traditions. Dialogism, in contrast, positions dialogue not merely as a literal conversation between individual standpoints, but as a relational exercise that continually grounds exchange as an active opportunity to understand others’ frames rather than solely as a transactional mechanism to elicit answers (Koehn, Reference Koehn1998; Arnett and Cooren, Reference Arnett and Cooren2018). As such, it is reflexive and discursive, countering consequentialism's binary dichotomy of ‘rational vs irrational’ with ‘or/rationality’ and contractarianism's presumptive alignment on belief in social institutions with inquiry into genuinely held and experientially informed alternative positions and an openness to questioning in whose best interest institutions tend to operate.

Deliberately establishing conditions for dialogue in the form of public ‘communication ethics architecture’ (Arneson and Arnett, Reference Arneson and Arnett1999) shifts the purpose of understanding others from a technical act of exchanging information in pursuit of a solution (e.g., what is their preference?) to one focused on eliciting interpersonal insight (e.g., what might cause them to prefer this?), in part by embracing rather than eliding difference and actively acknowledging how power imbalances influence dynamics, behaviors and tastes (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1996). As such, dialogism demands promoting and acknowledging positionality, or the specific and grounded stance, informed by experience, that shapes each individual stakeholder's operational frame during engagement with policy (Rowe, Reference Rowe, Coghlan and Brydon-Miller2014). This requires both recognizing how policy recipients uniquely see their situation, opportunities and potential outcomes, but also how traditional policy-making (and policymaker's) frames shape the goals and processes of policy development: which outcomes and challenges are prioritized, whose voices are excluded, and even what is considered worthy of policy-making attention. Just as importantly, a dialogic approach seeks to break down notions of ‘otherness’ that can lead to or reinforce in-and-out group classifications (Arnett and Cooren, Reference Arnett and Cooren2018).

For example, greater acceptance of practice-based evidence to augment evidence-based practice when crafting policy can feed both a fuller understanding of frames (Green, Reference Green2008; Ammerman et al., Reference Ammerman, Smith and Calancie2014) and a means to address disparities in data that inform policy, compensating for publication and null-result biases to reassert the importance – even the existence – of contexts left unremarked upon or data not collected. The importance of discovery as fundamental to the practice of dialogism also aligns with theories of situated learning, which suggest that knowledge and skills are socially co-constructed and embedded within the social and physical environment of a community of practice (Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky1978; Lave and Wenger, Reference Lave and Wenger1991). In the context of policy, positioning dialogic communicative exchanges as active learning environments can therefore broaden this activity of inquiry from policy recipients and end users to include other crucial perspectives – including community leaders, interdisciplinary allies, clients, scholars and practitioners – who might not otherwise be invited into policy framing conversations, but who can each uniquely contribute a different but equally valuable form of insight and expertise (Schwoerer et al., Reference Schwoerer, Keppeler, Mussagulova and Puello2022). Rather than maintaining a focus predominantly shaped on developing effective solutions – the ‘what’ – this allows practitioners to equally prioritize a broader set of relevant people and frames – the ‘who.’

From a practical standpoint, these practices can benefit from strategic design traditions that contribute human-centered methodologies and perspectives, which are increasingly employed during policy development. Where the practice of ‘design science’ focuses primarily on evidence-based design as a means for optimization, exploratory ‘design thinking’ and participatory alternatives seek to reframe policy through discursive practices, whether through iterative refinement of problem framing and solution development in the former or by actively cultivating relational, dialogic engagement to inform policy design in the latter (van Buuren et al., Reference van Buuren, Lewis, Guy Peters and Voorberg2020). These more abductive approaches can augment traditional policy development processes by contributing an in-depth understanding of user contexts, personal narratives and mindsets, involving policy recipients in design processes and treating them as experts of their own experiences. As a result, these activities serve a dual role by both countering paternalism inherent in more top-down practices and legitimizing resulting policy outputs (Einfeld and Blomkamp, Reference Einfeld and Blomkamp2021), a stance further bolstered by findings that authentic communication and dialogue can mitigate reactance even to policy or individuals with which one disagrees (Johnson and Johnson, Reference Johnson and Johnson2000). In doing so, these practices intentionally question presumptions of power and value systems and foster efforts to achieve interpersonal understanding through reframing and continually decentering the notion of a singular right or rational perspective in ways highly aligned with a dialogic stance (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, McGann and Blomkamp2020).

Despite these potential benefits, dialogism's emphasis on discursion may inadvertently imply replacing practical policy-making with endless questions that have no answers, in which the centrality of dialogue as a mechanism for understanding runs the risk of being taken overly literally or conjuring notions of all talk and no action. In addition, the more participatory and open-ended nature of dialogic inquiry that is familiar to design for policy and strategic ‘design thinking’ circles may feel unsettlingly elliptical and non-pragmatic in the evidence-based world of policy-making. These concerns, while valid, also fail to recognize that the value of dialogic theory potentially lies more in its ability to instill a mindset of continual inquiry that is not linked to a particular phase, recipient or outcome of policy-making, but which is rather expressed in the good-faith effort to both understand others’ lived experiences while simultaneously interrogating assumptions borne from one's own ground and positionality.

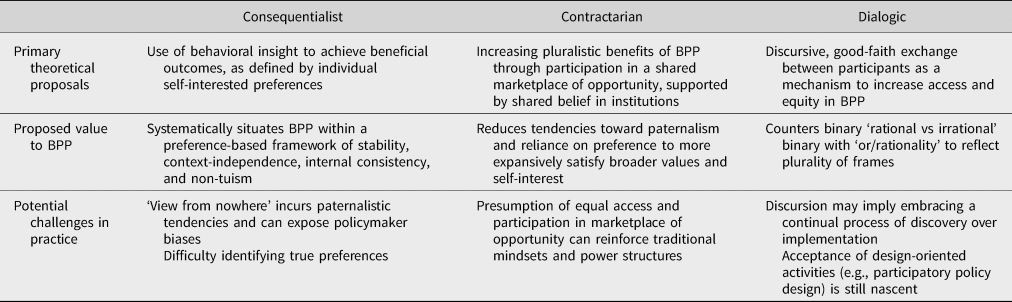

Key characteristics of these three philosophies of BPP – consequentialist, contractarian and dialogic – are summarized below (Table 1).

Table 1. A summary of consequentialist, contractarian and dialogic proposals for characterizing approaches to the behavioral state

Enacting a dialogical stance with policy recipients and amongst practitioners

More concretely, we propose that dialogism can inform the practice of conceiving and developing BPP approaches in two ways: first, by employing a behavioral justice lens that informs engagement with policy recipients to support diverse frames and exchanges more fully; and secondly, by turning that same lens on transdisciplinary work to identify dialogical artifacts or models that can help translate between disciplines.

Behavioral justice

The traditional notion of justice as an objective process of administering through authority has more recently been reclaimed as a redistributive activity, less interested in delivering moral judgments than in addressing inequities. The Design Justice Network, for example, situates justice within a set of guiding principles that prioritize empowering and liberating communities from exploitative norms and seats of power rather than ones that deliver punitive or transactional measures (Constanza-Chock, Reference Constanza-Chock2020). A dialogical stance on marketplace functions as a form of ‘behavioral justice’ therefore might build off notions that while individuals can and should be empowered to engage in beneficial behaviors, they cannot be held truly accountable unless they have adequate access and resources to do so (Adler and Stewart, Reference Adler and Stewart2009). Achieving this form of justice, in essence, requires that individuals are entitled to equal entry to and benefits from options, are free from asymmetric applications of any ‘market tax’ that extracts extra investment to fit in, and – perhaps most importantly – that justice is not achieved through individual bootstrapping but through infrastructural and systems-level design.

This view aligns with emergent feminist and antiracist stances that recognize the degree to which power and privilege are often embedded into hard and soft infrastructures supporting decision-making and choice (Dombrowski et al., Reference Dombrowski, Harmon and Fox2016; Constanza-Chock, Reference Constanza-Chock2020; Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Gordon, Hancock, Stenger and Turner2022), such as the ‘view from nowhere’ common to social planner approaches that positions an all-knowing, all-seeing, but unsituated perspective as a mechanism to judge rational choice (Koehn, Reference Koehn1998). While at best, this can be benignly paternalistic, at worst, it can yield perverse solutions, as when Robert Moses embedded privilege into New York City's hard infrastructure to prevent bus-reliant – and typically lower-class – populations from traveling to the seashore by making bridge clearances en route too low for buses to pass (Winner, Reference Winner1980).

This suggests that justice in the context of BPP requires attention at the level of system conditions within which choices are perceived and pursued and which support a plurality of frames in addition to a plurality of values, rather than at the level of discrete interventions. The notion of solving for conditions expands upon the field's traditional orientation toward choice architecture by also attending to ‘choice infrastructure’, which focuses less on perfecting specific behavioral change outcomes than on indirectly enabling behaviors through the design of physical, technological, social and procedural infrastructures (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2022). As such, the design of infrastructural conditions can provide room for multiple viable solutions to emerge, which align with more generalized design principles rather than attempting to optimize for a single frame or intervention. For example, research in child welfare settings has shown that collaborative arrangements allowing for flexibility, while still prioritizing children's well-being, can yield more effective and humane results than adherence to a strict, inflexible model (van der Bijl-Brouwer and Malcolm, Reference van der Bijl-Brouwer and Malcolm2020).

Additional examples can be seen in ‘universal design’ principles – such as curb cuts – that outline characteristics of accessible solutions without overdetermining their actual form (Story et al., Reference Story, Mueller and Mace1998) or in notions of system stewardship that allow citizens to self-moderate policy in accordance with their community's specific needs (Hallsworth, Reference Hallsworth2011). Policy conditions might therefore ‘satisfice’ multiple – sometimes seemingly contradictory – frames rather than optimizing for one, with a preference for reducing potential misfit solutions over centering on a single perfect one (Simon, Reference Simon1957; Alexander, Reference Alexander1964). This approach recalls Ostrom's governing rules of commons, in which commons establish their own governance while still recognizing the value of functioning within a larger system model to address broader or more complex requirements (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990). Given that even self-governance requires coordination at the level of systems-level networks, a dialogic approach to informing shared, system-level design principles that ensure interoperability and coordination while also allowing for emergent or multi-faceted needs represents a potentially powerful contribution to policy.

Dialogic design methods that investigate relationships, rather than individual unit needs and aspirations, have already been positioned and used as an alternative to user-centeredness in systems design (Jones, Reference Jones and Metcalf2014). These approaches allow interventions to emerge from the participants, using self-organization as a means to foster healthier outcomes rather than relying on top-down, one-size-fits-all solutions. Taking a dialogic stance in policy-making processes can also leverage familiar engagement policy design methods such as co-design, which emphasizes the relational nature of policy design and positions citizens and residents as co-equal to policymakers (Blomkamp, Reference Blomkamp2018; Schwoerer et al., Reference Schwoerer, Keppeler, Mussagulova and Puello2022). While still recognizing policymaker expertise, these approaches reposition policy recipient perspectives and experiences as equally important factors in determining conditions that align with a range of values, frames and desired outcomes. BPP methodologies such as Nudge+ (Banerjee and John, Reference Banerjee and John2021) that already encourage reflection and reflexivity may be naturally inclined toward dialogic principles. Finally, in addition to delivering valuable insight to inform principles for effective policy conditions, adopting dialogical approaches also reflects evidence that successfully implementing policy relies as much on its perceived legitimacy and trust in those doing the implementing than on the potential outcomes of those policies (Metz et al., Reference Metz, Jensen, Farley, Boaz, Bartley and Villodas2022).

Dialogical ‘boundary objects’ and transdisciplinarity

It is increasingly recognized that the field of BPP can benefit from partnering more actively with other disciplines from both inside and outside the traditional behavioral sciences (Feitsma and Whitehead, Reference Feitsma and Whitehead2022). However, interdisciplinary collaboration also heightens the potential for miscommunication and friction between definitions, methodologies and measures of success that may inhibit the effective translation and exchange of relevant content across practitioners. Dialogic approaches to frame plurality are therefore as relevant to policy design collaborators and cross-disciplinary partners as they are to policy recipients.

Whereas engaging with citizens might employ dialogism to better surface and understand the reality of lived experiences, transdisciplinary activities can benefit from adopting translational methodologies that honor the depth and rigor of various specialist frames and disciplinary expertise during collaborative activities. This suggests the value of dialogic artifacts known as ‘boundary objects’, defined as symbolic or tangible structures that are meaningful to diverse domains while still maintaining their integrity within individual disciplines (Star and Griesemer, Reference Star and Griesemer1989; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Ballie, Thorup and Brooks2017); and which share a characteristic ability to ‘not suppose an epistemological primacy for any one viewpoint’ (Star and Griesemer, Reference Star and Griesemer1989, p. 389). For example, a geological map can be collectively used and enhanced by diverse stakeholders with an assortment of lenses, concerns, interests and contributions; where a surveyor might use that artifact to perform or document analyses, a hiker might use it to choose a route and a geologist might contribute perspectives on how characteristics of the current terrain might change in the future. While often informed by theoretical or empirical interests, the purpose of a boundary object is typically pragmatic, focused on furthering the goals of applied work through its ability to support the capture and exchange of knowledge even when individual disciplines or practitioners do not themselves share perspectives, goals or experiences.

In a BPP context, boundary objects can play a useful dialogical role as a medium for transdisciplinary work by supporting collaboration and conversation between disciplines during policy-making activities, through shared structure and learning mechanisms of identification, coordination, reflection and transformation (Akkerman and Bakker, Reference Akkerman and Bakker2011). For example, while there may be conceptual agreement that understanding context is important when developing interventions, academic researchers and on-the-ground practitioners may focus on very different facets or conceptions of context in their actual practice. Boundary objects such as frameworks can externalize both what content is captured (or not) and how it is articulated, allowing practitioners to productively question assumptions, establish cross-disciplinary connections that might otherwise go unremarked upon and serve as a center of gravity for sense-making and further inquiry. In such cases, boundary objects provide a shared ground through which insights can be captured, interrogated and shared, despite the fact that individual fields are likely to focus on different data or phenomena.

Just as dialogic practice to understand policy recipients’ frames is not intended to prioritize or establish the primacy of any one view, boundary objects in transdisciplinary practice should not be seen as mechanisms for achieving consensus or checkpoints to ensure alignment. Instead, these shared structures should be viewed as a means to more fluidly surface and support many different goals and processes rather than optimizing for a single disciplinary perspective, allowing participants to cultivate diverse frames simultaneously. The creation of behavioral boundary objects can therefore support discursive communication and collaboration across disciplinary experts, practitioners in the field and community members who can provide deep insight into germane issues, enabling exchange without watering down contributions or force-fitting practices into a single disciplinary concept. Rather than being seen or used as a stage in a problem-solving process, the dialogic value of boundary objects derives from their ability to continually navigate conceptual transitions that naturally result from actively crossing disciplinary boundaries throughout policy design.

In addition to their value to policy design and development processes, the multi-faceted and dialogical value of boundary objects can also be seen in their applied use, with some suggesting that novel or innovative situations, or complex contexts that reflect competing agendas, interests and values, may gain particular benefit (Mengiste and Aanestad, Reference Mengiste and Aanestad2013; Terlouw et al., Reference Terlouw, Kuipers, Veldmeijer, van ‘t Veer, Prins and Pierie2022). In the context of public health, for example, Covid-19 vaccination record cards provided by the US Center for Disease Control (CDC) early in the pandemic served as a form of boundary object; not only did they provide a simple and low-tech mechanism for individuals to keep track of boosters, but they also furnished service providers such as restaurants and airlines with proof of vaccination when restrictions were still in force and allowed clinicians to confirm the information required to confidently deliver medical advice or interventions. Electronic health records (EHRs) can also function as boundary objects by supporting patient-, clinician-, caregiver- and administrative-facing interfaces and mechanics, in which users with radically different needs or motivations can still benefit from a shared body of knowledge. For example, an Ethiopian public health care digital information system functioned as a boundary object by actively highlighting, even foregrounding, contradictions and differences between stakeholder needs that revealed a need for dialogic exchange to explicate (Mengiste and Aanestad, Reference Mengiste and Aanestad2013).

Despite their potential value as a dialogical device to support disciplinary collaboration, boundary objects – like any socially constructed structure – are never entirely agnostic. Rather, boundary objects are ideological and social artifacts that have the power to shape meaning, such as defining what qualities are considered important enough to include in the first place (Huvila, Reference Huvila2011; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Pye and Correia2017). Just as scientific disciplines and practices reflect embedded belief systems and social norms while appearing outwardly objective, boundary objects similarly can run the risk of instantiating and channeling existing positions of power if not continually interrogated for potential bias (Latour, Reference Latour1986). If used unreflectively or with the presumption of truth rather than a case of pragmatic ‘good enough’, therefore, boundary objects can enforce a kind of inadvertent paternalism; as such, while boundary objects are themselves dialogic devices in the hands of practitioners, employing a frame of continual dialogic inquiry also requires turning that lens toward the structure and use of these objects as well.

Conclusion

Dialogism presents an alternative theory of the behavioral state, in the form of an approach that can overcome the paternalism inherent in top-down consequentialist policy-making while also questioning the underlying contractarian principle that opportunity knocks equally for everyone. This proposal is grounded in the fundamental reality that each of us experiences the world differently, and what may seem normal or rational to one person may be alien to others, including those responsible for creating policy. As a result, the dialogic purpose and practice of BPP are less concerned with correcting for ostensibly suboptimal choice-making to support a best or preferred choice than on supporting discursive questioning of what ‘good’ outcomes look like in the first place, and crafting conditions for policy development and policy itself that can support seemingly contradictory perspectives. In a practical context, this suggests the importance – even the necessity – of integrating tools, methods and practices that support cross-perspective- or disciplinary-dialogues when designing policy, and the value of encouraging a good-faith understanding of the plurality of frames held by all stakeholders. Achieving this is not just a matter of policy effectiveness but of ‘behavioral justice’ – decentering the traditional loci of expertise and power to reflect the value and perspective inherent in lived experience.

Embracing a dialogic approach therefore also prompts new questions about the use of paternalism and rational choice as paradigmatic framing devices for behavior and behavioral interventions. The urge to encourage rational choice tends to presume a fixed point of view, one which may fail to recognize how rationality is both situated and embodied in ways that may not be easily understood by policymakers or others faced with similar choices. As such, the dialogical characteristics proposed here – a focus on recognizing, even cultivating, difference rather than presuming alignment; listening as a mechanism to learn rather than to complete transactions; and encouraging all to flourish equally – are proposed with the desire to reframe the conversation away from whether policy is paternalistic or not, or to what degree, and more toward how recognizing a plurality of frames can help us collectively achieve the diversity of experience, and by creating conditions that support a wider range of possible, desirable public policy outcomes.

In addition, where contractarianism contributes useful rejoinders to three of consequentialism's four normative economic pillars of rational choice – stability, internal consistency and context-independence – it has less to say on the fourth criterion: the primacy of a non-tuistic, self-interested lens on rational choice. Despite reciprocity's role in contractarian motives and market forces (Oliver, Reference Oliver2019), focusing exclusively on individual self-interest may underemphasize the necessity of interdependence. Relational and tuistic motives for action, often grounded in caretaking and tending, are typically coded as feminine; at the same time, critics of feminist theory struggle against too heavily ascribing women's motivations to relational urges, which rob them of the right to their own self-interested behavior by positioning women primarily as caregivers (Koehn, Reference Koehn1998). Yet applied public policy is inescapably relational; aggregating personal best interests rarely results in outcomes for collective or non-human benefit, and motives for behavior may function differently within communal, family or organizational environments. Indeed, arguably the largest challenges of our time – combating climate change to ensure the lasting sustainability of our planet, maintaining viable democracies, public health crises – are wicked problems, characterized by a plurality of frames and ‘or/rationalities’ that cannot be solved through self-interest alone. As such, a dialogic approach that moves beyond reciprocity and personal welfare as a market factor to promote interdependence of individuals and entities as co-equal to independence seems worthwhile.

Just as consequentialism and contractarianism are useful, but imperfect, conceptual models, dialogism's discursive, reflexive approach will no doubt introduce new issues that further theories will attempt to address. The potential perception of endless circularity and lack of resolution posed by dialogism – or the perception of dialogic policy design as a process of being slowly but surely talked to death – may face resistance in a world often predicated on efficiency and cost-effectiveness. However, the value of positioning BPP within any theoretical framework lies less in finding a perfect fit than in illuminating the assumptions that theory takes for granted. Where the consequentialist theory presumes stable, consistent and decontextualized preferences in one's best interest may shape a working definition of rational behavior, for example, contractarianism provides a counterpoint to its tendencies toward paternalism and positioning different values as deviant rather than simply different. Similarly, while contractarianism's market-based community of advantage frees decision-making from a view from nowhere, the premise that the legitimacy of social institutions required for these mechanisms of exchange is de facto shared must be interrogated in the light of a need to support not just diverse values, but a plurality of frames. But perhaps, in these times of fake news and misinformation, when opposing constituencies increasingly take intractable positions simply for the sake of being antagonistic, a healthy dose of dialogism held in good faith to achieve more communal well-being is more necessary than ever.

Competing interest

The author(s) declare none.