Introduction

In modern representative democracies, elections are the principal mechanism through which citizens hold their leaders to account and prevent abuses of power. Yet recent research has revealed a perplexing version of the age‐old ‘Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?’ problem: electoral institutions themselves are highly vulnerable to manipulation by interested parties. It is in the nature of democratic institutions that the conduct of elections is ultimately under the control – direct or indirect – of politicians and political parties who have a strong interest in their outcome. In recent years, the most commonly proposed solution to this problem has been the establishment of independent electoral commissions that are insulated from political control and thus in theory immune to partisan manipulation (Hartlyn et al. Reference Hartlyn, McCoy and Mustillo2008; López‐Pintor Reference López‐Pintor2000; Magaloni Reference Magaloni2010; Mozaffar Reference Mozaffar2002; Rosas Reference Rosas2010; Trebilcock & Chitalkar Reference Trebilcock and Chitalkar2009). Most states that have democratised over the past 25 years have adopted independent electoral commissions, and this model is now the most common worldwide (International IDEA 2006, 2014; López‐Pintor Reference López‐Pintor2000).

Yet even when electoral management bodies (EMBs)Footnote 1 are formally independent, de facto independence from political influence and impartial electoral administration are often difficult to achieve, particularly in new and fragile democracies and hybrid states. There are a number of ways in which partisan actors can exert pressure on electoral administrators. EMBs are typically funded out of the state budget, which is virtually always under the control of politicians. Moreover, in many contexts, elected representatives play a role in the selection of the EMB members who will be in charge of running the electoral contests at which politicians’ jobs will be on the line. Unsurprisingly, political actors often seek to exploit this conflict of interest to their advantage. Lack of impartial electoral management has been found to be a serious threat to electoral integrity in many states (Hamberg & Erlich Reference Hamberg and Erlich2013; Hartlyn et al. Reference Hartlyn, McCoy and Mustillo2008; Kelley Reference Kelley2012; Norris Reference Norris2015; Trebilcock & Chitalkar, Reference Trebilcock and Chitalkar2009), and several empirical studies have found formal EMB independence to be of considerably less importance than the de facto impartiality of electoral officials (Birch Reference Birch2011; Hartlyn et al. Reference Hartlyn, McCoy and Mustillo2008; Norris Reference Norris2015; Opitz et al. Reference Opitz, Fjelde and Höglund2013). This suggests that though formal EMB independence may help in maintaining electoral integrity, other actors may be equally – if not more – important in fostering impartiality. Up to now, the rigorous testing of alternative pathways to good electoral governance has been hampered by lack of comprehensive cross‐national data on electoral governance. The recent release of the Varieties of Democracy (V‐Dem) dataset provides a solution to this problem, opening the way for more detailed analysis of electoral management body impartiality than has heretofore been possible (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge2016).

Situating itself in a growing body of work that analyses relationships among the disaggregated components of democracy (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge2011), this article offers a novel theoretical account of electoral oversight that views electoral integrity as being shaped by an array of institutional influences. The core theoretical contribution of the article is to show that elections of high integrity can be achieved even in the absence of impartial electoral management, if and when alternative formal and informal oversight institutions are present.

The article tests the presence of such substitution effects on a global set of elections held between 1990 and 2012 using the new V‐Dem data on election integrity and de facto EMB autonomy (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge2016). The argument advanced is that there is a core group of electoral oversight institutions that can – provided they are robust – serve as relatively effective checks on electoral conduct. It is argued that while an impartial EMB is one of those important oversight institutions, other formal and informal institutions can serve as effective substitutes when the independence of EMBs is threatened by partisan pressure. These institutions include the judiciary, the media and civil society, which can help maintain election integrity by compensating for lack of electoral administrator accountability.Footnote 2 Contrary to the mainstream view, which places emphasis on the inherent formal and informal characteristics of EMBs as the principal instruments of accountability, this alternative account sees an EMB as but one of a number of agents of accountability and shows that other institutions can effectively carry out the role of electoral oversight.

Given the central role that these alternative accountability agents can play in checking electoral abuse, the principal hypothesis to be tested in this article is that these institutions can largely compensate for deficiencies in electoral administration independence.Footnote 3 If this is true, it means that states can achieve acceptable levels of electoral integrity – understood here in terms of adherence to internationally accepted norms of electoral conduct during the pre‐electoral, electoral and post‐electoral components of the electoral cycle (Norris Reference Norris2014) – even in the absence of impartial electoral administrators. This hypothesis is tested on a cross‐national time‐series dataset of 1,047 national‐level elections held in 156 electoral regimes between 1990 and 2012. The results of the analyses demonstrate that when de facto EMB independence is low, media independence, independence of the judiciary and active civil society can, as predicted, compensate for the lack of administrative checks on electoral conduct. These novel findings have considerable implications for research on electoral integrity, as well as for practical electoral assistance activities.

How accountable electoral governance is maintained

Since the publication in 1748 of Montesquieu's L'Esprit des lois, political theorists and commentators have sought to invoke the idea of divided powers and the attendant checks they are seen to entail in order to argue that political accountability is best achieved through institutional oversight. As Montesquieu phrased it:

To prevent the abuse of power, ‘tis necessary that by the very disposition of things power should be checked by power. A government may be so constituted, as no man shall be compelled to do things to which the law does not oblige him, nor forced to abstain from things which the law permits. (Montesquieu Reference Montesquieu, de and Wallace Carrithers1977: 200)

To this type of ‘horizontal’ accountability, which is a guarantor of rule of law, needs to be added the ‘vertical’, or political, accountability exercised in contemporary democracies by the citizenry over those who rule them (O'Donnell Reference O'Donnell1994, Reference O'Donnell, Diamond, Plattner and Schedler1999). Schmitter (Reference Schmitter, Diamond, Plattner and Schedler1999: 62, Note 4) suggests a third variation: ‘oblique accountability’, which refers to ‘efforts by non‐state or semi‐state institutions that seek to wield countervailing powers in order to hold rulers accountable, not just for their legal transgressions but also for their political misdeeds, but depend on their oblique capacity to enhance citizen awareness and collective action in order to back up their actions’. Understood in this sense, the oblique accountability exercised by extra‐state institutions can be seen as a supplementary form of accountability that works to ensure that state actors refrain from abusing the powers they hold.

Within this framework, electoral administration institutions can be seen as ‘agents of accountability’ (Diamond et al. Reference Diamond, Plattner and Schedler1999: 3),Footnote 4 but also as objects of accountability. Elections are the primary mechanism through which the citizenry exercises vertical (political) accountability, which it does retrospectively by sanctioning unsatisfactory performance (Manin et al. Reference Manin, Przeworski and Stokes1999; Mulgan Reference Mulgan2003: 41). At the same time, electoral administration institutions must be subject to a degree of simultaneous horizontal (legal) accountability if they are to retain their character as institutions that guarantee a level playing field and impartial conduct in the elections.

Independent electoral commissions are one manifestation of the principle of horizontal accountability, in that they are designed to ensure that electoral rules and legislation shaped by partisan lawmakers are implemented in an impartial manner, such that those who framed the law are nevertheless subject to it in the same way as other actors. From the point of view of electoral governance, the problem with this set‐up is that electoral institutions rarely have the constitutional standing of the other branches of power, and they are ultimately reliant on politicians and politicised administrators who typically agree their budgets, appoint their members and are in a position to exert forms of subtle pressure. In some cases, partisan actors also offer illicit inducements to electoral officials to help facilitate particular electoral outcomes. This opens a vulnerability which even formally independent EMBs are often powerless to resist. Thus statutory guarantees of political independence do not always translate into de facto impartiality, and electoral commissions can fall under the sway of incumbent political forces. The most commonly proposed remedy in this context is to bolster formal EMB independence, and the establishment of independent, professional EMBs has been a core aspect of the set of tools used by electoral assistance providers and advisers to newly democratic states (Goodwin‐Gill Reference Goodwin‐Gill1994; López‐Pintor Reference López‐Pintor2000; Ottoway Reference Ottoway2003; Pastor Reference Pastor, Diamond, Plattner and Schedler1999). Yet absent a means of overcoming the fundamental structural problem of vulnerability to political pressure, many formally independent EMBs have failed to perform professionally (Bader Reference Bader2012; Elklit & Reynolds Reference Elklit and Reynolds2002; Hamberg & Erlich Reference Hamberg and Erlich2013; Norris Reference Norris2015; Pastor Reference Pastor, Diamond, Plattner and Schedler1999; Schaffer Reference Schaffer2008). Not only does lack of professionalism have a negative impact on electoral integrity, but it can also lower voter confidence in the electoral process (Atkeson & Saunders Reference Atkeson and Saunders2007; Bowler & Donovan Reference Bowler and Donovan2014; Bowler et al. Reference Bowler2015; Hall et al. Reference Hall, Monson and Patterson2009; Kerr Reference Kerr2013; McAllister & White Reference McAllister and White2011; Norris Reference Norris2014, Reference Norris2015; Schedler Reference Schedler2013).

Professionalism requires both impartiality and capacity. It should be stressed that independence of EMBs from partisan influence entails impartial decision making, though it does not necessarily require complete disassociation from partisan actors. Indeed, electoral commission members are in many contexts appointed by political parties; this does not in and of itself mean that they behave less professionally, and the academic jury is still out on whether the involvement of political parties in the selection of EMBs members has a negative impact on overall election quality (Birch Reference Birch2011; Estévez et al. Reference Estévez, Magar and Rosas2008; Rosas Reference Rosas2010; Hartlyn et al. Reference Hartlyn, McCoy and Mustillo2008; Opitz et al. Reference Opitz, Fjelde and Höglund2013).

This is where additional accountability agents are helpful in maintaining professional electoral management. O'Donnell (Reference O'Donnell, Diamond, Plattner and Schedler1999: 41) remarks that ‘to a large extent the effectiveness of horizontal accountability depends not just on single agencies dealing with specific issues but on a network of such agencies that includes courts committed to supporting this kind of accountability’.Footnote 5 Whitehead (Reference Whitehead2006) also highlights the complementary role of different formal and informal institutions in the electoral context.

Dunn (Reference Dunn, Przeworski, Stokes and Manin1999: 337–339) notes that there are two broad ‘surveillance’ approaches through which citizens can hold public officials accountable between elections: the criminal justice system, and regimes of freedom of information. The traditional means of checking executive abuse of power has been the judiciary, which in many contexts enjoys relative autonomy by virtue of the professional training and role socialisation of judges, and also due to the fact that judges generally control recruitment to this branch of the state. Judges often enjoy greater popular confidence and trust than elected politicians, despite the lack of formal popular control over this branch of power; independent judiciaries can therefore help to bolster horizontal accountability and protect democracy (Eisenstadt Reference Eisenstadt, Helmke and Levitsky2006; Gibler & Randazzo Reference Gibler and Randazzo2011; Moraski Reference Moraski and Lindberg2009). In the electoral sphere, the judiciary plays a formal role in adjudicating disputes in most contemporary states (International IDEA 2010: 62–80). Even in contexts where the judiciary is subject to considerable political pressure, it can still be an effective venue for addressing electoral disputes (Popova Reference Popova2006). More recently, separate electoral courts and independent dispute resolution bodies have become more common as part of the general trend toward the ‘judicialisation’ of electoral administration (International IDEA 2010: 43). There is some empirical evidence that independence of judicial bodies is associated with better quality elections (Van Ham Reference Ham2012).Footnote 6

The ‘network’ of accountability relevant to electoral governance also includes the media and civil society, which exert oblique accountability, or in Lindberg's (Reference Lindberg2013: 215) terminology, ‘societal accountability’. Unlike the judiciary, the media do not have formal powers in adjudicating electoral disputes. Yet the broadcast, print and – increasingly – social media nevertheless play important roles in virtually all aspects of the electoral process.Footnote 7 As O'Donnell (Reference O'Donnell, Diamond, Plattner and Schedler1999: 30) notes, the media in new democracies ‘tend to become surrogate courts’ in that they ‘expose alleged wrongdoings, name those supposedly responsible for them, and give whatever details they deem relevant’. The media play a role in informing the public about misconduct, which is a necessary precursor to popular mobilisation against abuse (Fearon Reference Fearon2011; Norris et al. Reference Norris, Frank and Martínez i Coma2015). By monitoring EMBs and political actors and publicising evidence of electoral abuse during the election campaign, on election day and after the election, the media serve to expose misconduct and condemn it. It is rare that public figures do not feel obliged to address allegations of electoral impropriety exposed in the media, and rare also that such allegations do not affect popular attitudes toward the electoral process. Indeed, previous research has found that media freedom is a strong predictor of electoral integrity (Birch Reference Birch2011; Van Ham Reference Ham2012; Schedler Reference Schedler2013: 225; Simpser Reference Simpser2013: 54–56).Footnote 8

Civil society organisations are the third oversight institution that we might anticipate would serve to keep EMBs on the straight and narrow. These organisations often engage in domestic election observation to monitor electoral processes and are typically pivotal in pushing for electoral reform once elections are over (Grömping Reference Grömping, Norris and Nai2016). Civil society organisations that seek to promote election integrity work in concert with the media to monitor electoral processes and publicise allegations of abuse. They typically employ more systematic and rigorous information‐collection techniques than journalists, and a well‐staffed organisation normally has a larger grassroots presence than any media organisation could hope to achieve. Civil society organisations are thus an excellent source of potentially newsworthy information for journalists, and they are usually all too happy for the media to help publicise their findings. In addition, these organizations are pivotal in signaling areas that need electoral reform and promoting such reform once elections are over. The promotion of reform can occur via various pathways, ranging from informal channels of communication with EMBs in order to alert them to problems as they are identified, to lobbying politicians and political parties and organising citizen protests to promote (and if needed, demand) reform, as well as seeking change through formal institutions of electoral justice by lodging complaints about the electoral process and by collecting evidence that can be used in legal proceedings stemming from election‐related crimes (Bjornlund Reference Bjornlund2004; Grömping Reference Grömping, Norris and Nai2016).Footnote 9

Though the institutional autonomy of EMBs undoubtedly has a range of historical causes that vary from state to state (Mozaffar Reference Mozaffar2002; Gazibo Reference Gazibo2006), the above considerations suggest that at any given point in time, electoral management bodies are subject to pressure from various sources, and in the absence of effective oversight by other institutions, they are largely accountable to political actors. Under these circumstances, EMBs risk succumbing to political pressure and deviating from professionalism. Yet, our core argument in this article is that when there are other effective oversight institutions, including the formal institution of the judiciary and the informal institutions of the media and civil society, relatively high electoral integrity can still be achieved, even if de facto EMB independence is lacking.

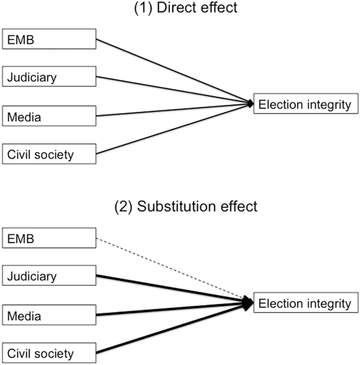

The analysis in subsequent sections is designed to test the following hypotheses: (1) that robust oversight by the judiciary, the media and civil society contribute directly to electoral integrity; and (2) that there is a substitution effect whereby these oversight mechanisms provide compensating checks on electoral conduct if de facto EMB independence is lacking. These hypothesised relationships are represented schematically in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Hypothesised relationships: Oversight institutions and election integrity.

Data and methods

These hypotheses are tested on a cross‐national time‐series dataset of 1,047 national‐level elections held in 156 electoral regimes between 1990 and 2012, using data from the Varieties of Democracy project, a new comprehensive dataset on democracy that includes data on almost 400 indicators of democracy in 173 countries around the world from 1900 to 2012 (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge2016).Footnote 10 The country‐expert data is combined into country‐year estimates using Bayesian ordinal item‐response theory models developed by a set of methodologists (Pemstein et al. Reference Pemstein, Tzelgov and Wang2015). In this article we use the V‐Dem v6.1 data (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge2016) on election integrity, the autonomy and capacity of electoral management bodies, and the presence of domestic observers. Our other variables are derived from International IDEA (2006, 2014), the World Development Indicators, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Creditor Reporting System dataset, the National Elections across Democracy and Autocracy (NELDA) dataset (Hyde & Marinov Reference Hyde and Marinov2012) and the Cingranelli‐Richards Human Rights dataset (Cingranelli et al. Reference Cingranelli, Richards and Clay2014; Teorell et al. Reference Teorell2016). Each variable is described in more detail below. We include all states that held multiparty national elections between 1990 and 2012. The elections included are national‐level presidential and parliamentary elections that allowed for de jure multiparty competition.

Electoral integrity

As overall measures of electoral integrity often include evaluations of EMB autonomy and media independence, we use a measure of electoral integrity that explicitly excludes those aspects, taking the average of a number of specific problems that can occur in elections and that signal compromised electoral integrity (Birch Reference Birch2011; Norris Reference Norris2014). We include the following: vote buying, government intimidation, election violence and other irregularities such as the use of double identification and ballot‐stuffing. Country experts were asked to evaluate for each election to what extent these irregularities were present. Responses varied on a five‐point ordinal scale from 0 to 4, ranging from widespread presence of irregularities to the absence of irregularities.Footnote 11 We validate our measure of electoral integrity with the overall measure of electoral integrity included in the V‐Dem dataset.Footnote 12 The correlation between our measure and this overall measure is 0.86, indicating that our dependent variable captures electoral integrity well while avoiding overlap with our key independent variables.Footnote 13

De jure EMB independence

De jure EMB independence was coded using IDEA cross‐sectional data on electoral management institutions (International IDEA 2006). IDEA distinguishes three models of electoral management: governmental, mixed and independent. Under the governmental model, ‘elections are organized and managed by the executive branch through a ministry (such as the Ministry of the Interior) and/or through local authorities’ (International IDEA 2006: 7). The independent model implies that ‘elections are organized and managed by an EMB that is institutionally independent and autonomous from the executive branch of government’ (International IDEA 2006: 7). This means that EMBs manage their own budget and are not accountable to the executive, though they are in practice often accountable to the legislature, the judiciary or the head of state. Finally, in the mixed model, the organisation of elections and implementation of electoral legislation generally lies with a government department and/or local government, while policy, monitoring and supervisory functions are located in an organisation independent of the executive (International IDEA 2006: 8).Footnote 14 Since we are interested in the potential causal relationship between EMB independence and electoral integrity, we use the IDEA data from 2006 (instead of the updated data from 2014).Footnote 15

De facto EMB independence

De facto EMB independence is measured using the Varieties of Democracy dataset indicator of EMB autonomy. EMB autonomy was measured by asking experts to evaluate ‘Does the Election Management Body (EMB) have autonomy from government to apply election laws and administrative rules impartially in national elections?’. Answers could vary on a five‐point ordinal scale, ranging from full EMB partiality to full EMB impartiality.Footnote 16 We again use the transformed item response theory variable (Pemstein et al. Reference Pemstein, Tzelgov and Wang2015), resulting in a continuous variable of EMB autonomy that varies from low to high autonomy, and rescale it so as to vary from 0 to 4.

Independence of the judiciary, media and civil society

Data on the independence of the judiciary, the media and civil society were taken from the Cingranelli and Richards Human Rights dataset (Cingranelli et al. Reference Cingranelli, Richards and Clay2014), as provided in the Quality of Government dataset (Teorell et al. Reference Teorell2016). Independence of the judiciary indicates ‘the extent to which the judiciary is independent of control from other sources, such as another branch of the government or the military’. Independence of the media indicates ‘the extent to which freedoms of speech and press are affected by government censorship, including ownership of media outlets’. Both variables are coded on a three‐point scale ranging from not independent to independent.Footnote 17 Independence of civil society is measured by the Cingranelli and Richards indicator on freedom of assembly and association. This variable indicates ‘the extent to which the freedoms of assembly and association are subject to actual governmental limitations or restrictions (as opposed to strictly legal protections)’ (Teorell et al. Reference Teorell2016), and provides a good indication of the de facto freedom of civil society organisations to operate as checks on electoral conduct. It is also coded on a three‐point scale ranging from not free to free.Footnote 18 As a robustness check, we run analyses using measures of judiciary, media and civil society independence based on V‐Dem data that are reported in the Online Appendix.Footnote 19

Control variables

EMB capacity, international and domestic observers and democracy aid

Given the likely importance of EMB capacity in shaping the degree to which EMBs operate autonomously and professionally in practice, we include EMB capacity as a control variable using the V‐Dem indicator for EMB capacity that varies from 0 to 4, indicating low to high capacity.Footnote 20

International observers and democracy aid

Since the international community has been increasingly active in monitoring and supporting elections in new democracies, we include two control variables that measure the involvement of international actors. The first is whether or not international election observers were present, based on data from the NELDA dataset (Hyde & Marinov Reference Hyde and Marinov2012). The second is the degree to which countries received democracy and election assistance from the international community, based on data from the OECD Creditor Reporting System.Footnote 21

Domestic observers

In addition to international observers, domestic observers are likely to contribute positively to election integrity. We measure the presence of domestic election observers using data from the V‐Dem dataset and check the robustness of results using the indicator for domestic observers from the Quality of Elections dataset (Kelley & Kolev Reference Kelley and Kolev2010).

Economic, institutional and regional control variables

Finally, we control for a number of variables that have been found to explain cross‐national variation in election integrity, such as gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (current US$) and GDP per capita growth (annual percent) (Birch Reference Birch2011; Norris Reference Norris2015; Schedler Reference Schedler2013; Simpser Reference Simpser2013), legislative electoral system type (Birch Reference Birch2011; Lehoucq & Kolev Reference Lehoucq and Kolev2015), as well as type of election (legislative, executive or concurrent) and region.Footnote 22 Data for the economic variables derive from the World Development Indicators,Footnote 23 and data for legislative electoral system type are based on coding by V‐Dem and the Database of Political Institutions data available in the Quality of Government dataset (Teorell et al. Reference Teorell2016).

Estimation strategy and robustness checks

The initial estimation strategy is time‐series cross‐national analysis with random effects for our model including de jure EMB independence (Table 1, model 1). A Hausman test indicates fixed effects should be used; this means that invariant variables including de jure EMB independence must be excluded from the model. As de jure EMB independence does not affect election integrity significantly, all our subsequent models are estimated using time‐series cross‐national analysis with fixed effects (Table 1, model 2 and Table 2). To check the robustness of our results, the Online Appendix reports results for (1) models specifying the judiciary, media and civil society variables as categorical variables instead of continuous and specifying these variables using V‐Dem data; (2) models with jackknife standard errors to check whether the results might be shaped by specific countries in our sample; and (3) models with a smaller sample excluding Western liberal democracies and models with a larger sample including election years before 1990. The results do not change substantively in these alternative model specifications.Footnote 24

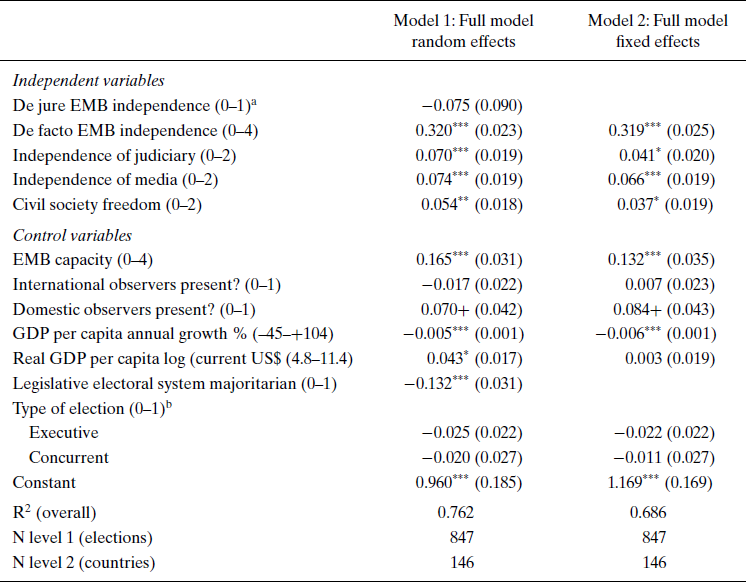

Table 1. De jure and de facto EMB independence and election integrity

Notes: Time‐series cross‐sectional analyses, random effects model 1, fixed effects model 2. P‐values: +0.1; *0.05; **0.01; ***0.001. Standard errors in parentheses. aDe jure EMB independence is coded as a dummy variable where 0 includes governmental and mixed types and 1 includes independent EMBs. bLegislative elections are the reference category. In model 1, regional dummies were also included as controls (coefficients not shown).

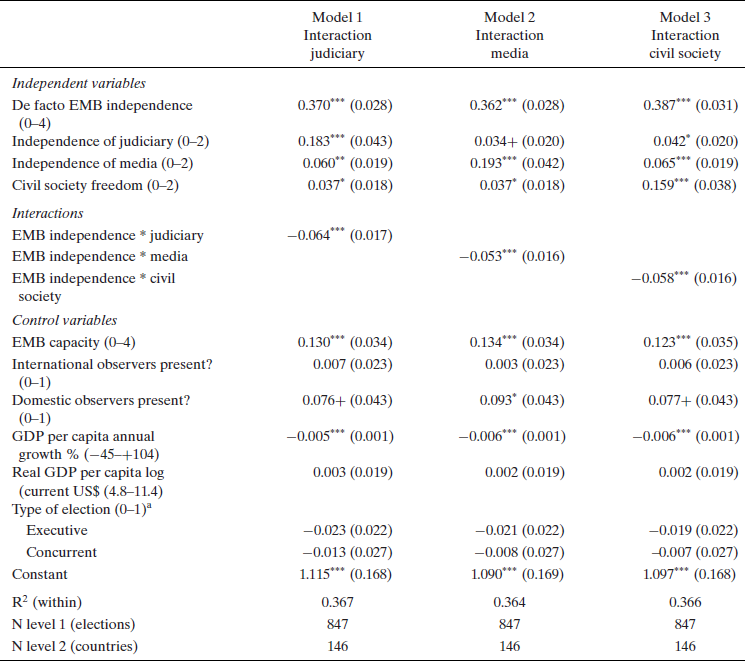

Table 2. Oversight institutions and election integrity

Notes: Time‐series cross‐sectional analyses, fixed effects. P‐values: +0.1; *0.05; **0.01; ***0.001. Standard errors in parentheses. aLegislative elections are the reference category.

Results

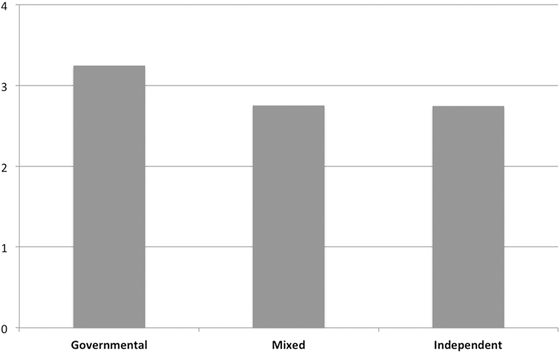

Regarding formal, de jure EMB independence, only 25 (16.5 per cent) of the countries in our sample have an EMB that is governmental, 24 (16 per cent) have EMBs that have a mixed model and 102 (67.5 per cent) have formally independent EMBs (International IDEA 2006).Footnote 25 Figure 2 shows the descriptive relation between formal EMB independence and election integrity in our sample of third and fourth wave regimes. Clearly, the descriptive relation between formal EMB independence and election integrity is the reverse of what one would hope to find: in countries with governmental models, election integrity appears to be higher than in countries with formally independent EMBs and mixed models.Footnote 26

Figure 2. Formal EMB independence and election integrity.

This suggests, in line with previous research, that what may really matter for securing electoral integrity is the way EMBs function in practice – that is, their degree of de facto independence. Although establishing formally independent EMBs is undoubtedly a step in the right direction, in many of the countries studied here, EMBs acquired formal independence as a response to problems with electoral conduct, which are unlikely to be resolved unless de facto independence is achieved in addition to de jure independence. Indeed, there is considerable variation in the degree of de facto EMB autonomy in the countries in our sample: the 1,047 elections for which we have data on EMB autonomy, the EMB was considered to act in an independent and impartial manner in 29 per cent of them, and 31 per cent of EMBs were scored as being ‘almost’ impartial. EMB autonomy was ambiguous in 16 per cent of cases; in 12 per cent of cases electoral authorities exhibited some partiality; and in another 12 per cent electoral authorities were manifestly under the political control of the incumbent government.Footnote 27

To test the effect of de facto EMB independence as well as the other oversight mechanisms on election integrity, we carried out time‐series cross‐sectional analyses shown in Table 1. In line with the descriptive results presented above, the effect of de jure EMB independence is negative and insignificant. However, de facto EMB independence has a strong and significant effect on election integrity. A shift from the lowest to the highest value of de facto EMB autonomy corresponds to an increase in election integrity of about 32 per cent – that is, an increase of 1.3 on the electoral integrity scale (Table 1, model 2). As predicted, the presence of independent media and freedom for civil society organisations to operate also contribute significantly and positively to election integrity, as does the presence of an independent judiciary.

As regards the control variables, EMB capacity is, as expected, highly relevant to improving election integrity, even once de facto EMB autonomy is accounted for. The effect of international observers is insignificant, while the effect of domestic observers is positive and significant one‐tailed. However, when analyses are done using the Kelley and Kiril (2010) measure for domestic observers, the effect is insignificant, suggesting that this effect might not be very robust. Effects for the remaining control variables are in line with previous findings in the literature: higher economic development is associated with higher levels of election integrity, and higher economic growth undermines election integrity. Likewise, majoritarian electoral systems negatively affect election integrity.Footnote 28 Results using fixed effects shown in model 2 indicate that most of these findings are robust also when using fixed effects, with the exception of the level of economic development, which appears better to explain differences in election integrity between countries than change within countries over time.

Summarising the initial findings, de facto EMB independence appears to be more important than de jure EMB independence for electoral integrity, confirming the results of previous research. Apart from de facto EMB independence, the other formal oversight institution – the judiciary – as well as informal oversight institutions of media and civil society also contribute directly to strengthening electoral integrity, as predicted by our theoretical model.

Our core theoretical argument proposes that oversight institutions may be even more important for electoral integrity when EMBs fail in their task of administering elections impartially. Indeed, the fact that even in contexts of lacking EMB autonomy a significant proportion of elections was considered to be free and fair by expertsFootnote 29 suggests the existence of alternative routes to achieving elections with high integrity. To test this hypothesis, Table 2 models the interaction effects between EMB autonomy and each of the three oversight mechanisms: judiciary, media and civil society.Footnote 30 The table demonstrates that the main effects found in Table 1 are confirmed: de facto EMB independence, judicial independence, media independence and civil society freedom exert strong direct effects on election integrity. The effects of control variables are also consistent with the results reported in Table 1.

Turning to the interaction effects, all run in the expected direction: as de facto EMB independence increases, the effects of the other oversight mechanisms on electoral integrity weaken, resulting in negative coefficients. To better interpret the interaction effects, as well as significance levels, Figure 3 shows the marginal effects of oversight mechanisms at different levels of de facto EMB independence.

Figure 3. Marginal effects of oversight mechanisms on election integrity.

As all three figures clearly show, when de facto EMB autonomy is very low, the effects of the other oversight mechanisms are strong and positive, only to decline as EMB autonomy increases. The effect of independent judiciaries on electoral integrity is strongest at the lowest levels of EMB autonomy, and declines as EMBs become more independent. At about 2 on the EMB autonomy scale (which corresponds to the transition from EMBs with ambiguous autonomy to EMBs that are considered almost and fully autonomous), the effect of the judiciary on electoral integrity is no longer significant. Turning to the other oversight mechanisms, there is also a clear conditional effect on electoral integrity: the presence of independent media and civil society appear to be most important for electoral integrity when de facto EMB independence is low. The pattern for civil society follows that of the judiciary, though the effect is somewhat less strong: civil society exerts a strong positive influence on election integrity at low levels of EMB autonomy and becomes insignificant at about 2, when EMBs move from ambiguous autonomy into being almost and fully autonomous.

The effect of independent media on election integrity is stronger: while also here the positive effect of independent media on electoral integrity is clearest when EMB independence is lower; it is only when EMBs become almost fully autonomous (at about 3 on the EMB autonomy scale) that the effect of media on election integrity becomes insignificant. By that point the EMB can guarantee clean elections without requiring vigilant media. Clearly, our second hypotheses is confirmed by the empirical analyses: it is when EMB independence is most severely lacking that other oversight mechanisms such as independent judges, independent media and active civil society can compensate and still secure free and fair elections.Footnote 31

Robustness checks for the analyses reported here demonstrate that these results remain substantively similar under different model specifications (see the Online Appendix). Analyses modeling the CIRI variables as categorical variables demonstrate that what really matters is that the judiciary is fully independent and media and civil society are fully free for these oversight institutions to function as compensating checks on electoral conduct when EMB autonomy is low. Partial civil society freedom and partial judicial independence do not significantly strengthen electoral integrity. Partial media freedom still strengthens electoral integrity, however, indicating it is indeed a very important oversight institution that can compensate for failing EMB autonomy. Results modeling judicial, media and civil society independence using V‐Dem measures confirm our findings for independence of the judiciary and the media. However, the conditional effect of civil society on election integrity is no longer significant. Results excluding Western liberal democracies do not affect our findings; all the results presented here are confirmed in this smaller sample. Finally, models with jackknife standard errors confirm the results presented here, as the interaction effects for independence of the media and civil society remain strong and significant, whereas the effect of independence of the judiciary is still significant but somewhat weaker in these models.Footnote 32

Illustrating causal mechanisms: Case studies of The Gambia, Madagascar and Guinea‐Bissau

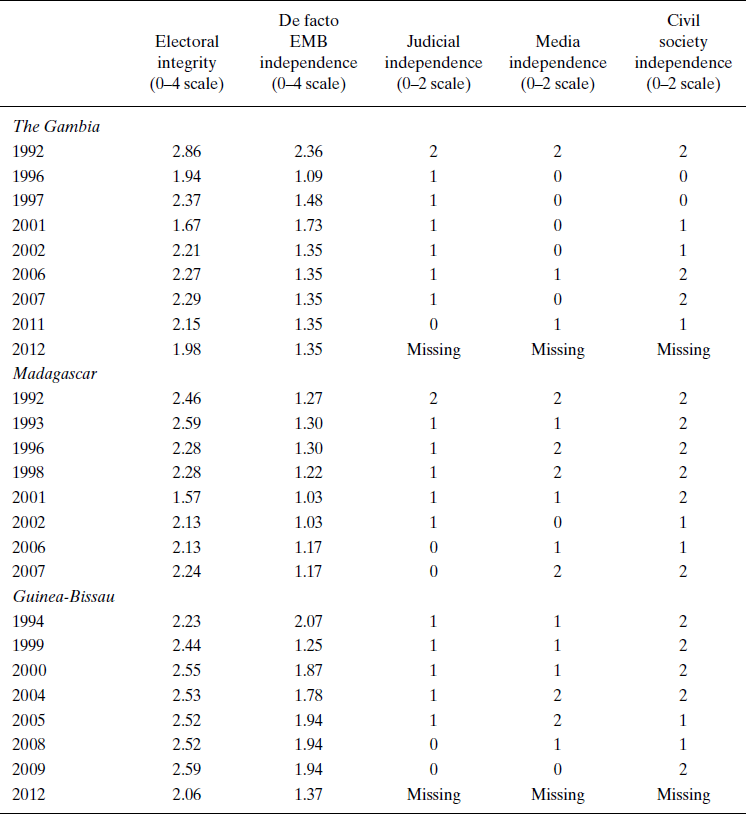

The Gambia, Madagascar and Guinea‐Bissau are cases that exemplify the phenomenon described in this article and serve to probe the causal mechanisms behind it. In all three cases, independent and/or semi‐independent accountability institutions helped to compensate for serious failings in election management, and in all cases the result was a reasonable level of election integrity for extended periods of time. The Gambia represents an example of judicial independence serving to prevent electoral abuse, Madagascar is provided as an example of the role of the media and Guinea‐Bissau offers a useful case to illustrate how civil society can help to protect electoral integrity. Table 3 displays the development of key indicators over time for these three cases.

Table 3. Scores for key variables in The Gambia, Madagascar and Guinea‐Bissau

Judicial independence in The Gambia

The Gambian experience shows that, under the right conditions, relative judicial independence can serve to maintain electoral integrity in the absence of a de facto independent EMB. The Gambia is one of the few African states to have retained multiparty competition virtually intact since independence, having held regular competitive elections since independence in 1965 (Bendel Reference Bendel, Nohlen, Krennerich and Thibaut1999). Gambian elections in the 1970s and 1980s were not without their problems however (Bratton & Van de Walle Reference Bratton and de Walle1997: 69), as the dominant People's Progressive Party regularly won in excess of four‐fifths of the vote.

After elections of relatively high integrity in 1992, a 1994 coup d’état brought Colonel Yayah Jammeh to power. Jammeh then retired from the military and won the presidential election in 1996 as the leader of the newly formed Alliance for Patriotic Re‐orientation and Construction (APRC); his party also won parliamentary elections – in which pre‐coup parties were banned – the following year. Though the ban on pre‐coup parties was lifted in 2001, the APRC nevertheless won the 2001, 2002, 2006 and 2007 elections comfortably. As Table 3 shows, election integrity fluctuated between 1992 and 2002, but remained relatively high from 2002 onwards.

While the 1996, 1997 and 2001 elections were deemed largely ‘fair and orderly’ (Saine Reference Saine1997: 555; Bendel Reference Bendel, Nohlen, Krennerich and Thibaut1999; Wiseman Reference Wiseman1998), competition was restricted in the 1996 and 1997 elections, and other problems such as high monetary barriers to candidacy, mal‐apportionment and abuse of state resources affected election integrity (Hughes Reference Hughes2000; Saine Reference Saine1997; Wiseman Reference Wiseman1998). Most ominous, perhaps, was the fact that the party of the former military junta maintained a paramilitary posture throughout the campaign, engaging in voter intimidation and sporadic acts of violence (Hughes Reference Hughes2000; Wiseman Reference Wiseman1998). Yet, from 2002 onwards, election integrity improved and remained relatively stable, attesting to the fact that elections afforded relatively open competition.

At the same time, de facto EMB autonomy was very low throughout the entire period, with the exception of the 1992 elections. From 1996 onwards, the electoral management body received markedly lower scores, rarely higher than 1.5. Though nominally independent, the Gambian electoral commission remained under the de facto control of the government throughout this period. According to the new 1996 constitution, the members of the electoral commission are chosen by the president and they have since been under de facto government control (Hughes Reference Hughes2000: 40; Saine Reference Saine2003: 337; Wiseman Reference Wiseman1998).

Throughout this period, The Gambia's civilianised military government has engaged in extensive repression of alternative voices. The independent media was beset by costly license fees, harassment and the threat of closure throughout the late 1990s and 2000s (Commonwealth 2012; Saine Reference Saine2003, Reference Saine2008; Senghore Reference Senghore2012). Civil society has also suffered from suppression; Hughes (Reference Hughes2000: 48) argues that ‘the relative underdevelopment of society and the historic dominance of the state have had a stultifying effect on associational life’.

In this context of widespread political manipulation and harassment of state and non‐state institutions, scholars agree that the judiciary has consistently stood out as a bulwark against total incumbent control and has remained relatively unpoliticised (Wiseman Reference Wiseman1998: 65; Hughes Reference Hughes2000: 43; Senghore Reference Senghore2012: 51). In a thorough set of analyses, Senghore details the ways in which judicial independence have served to preserve relatively high levels of electoral integrity. He recounts that in 2005,

leaders of the four opposition parties in the country obtained a crucial victory in an important court case they filed against the state shortly before the 29 September 2005 bye‐elections scheduled to be held in four constituencies. The Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) made a decision that it was going to allow voters whose names did not appear on the list of the main register of voters to vote at the bye‐election if they came with valid voters’ cards. The opposition cried foul and argued that such a practice would not ensure genuine elections and, therefore, took the matter to court. On 28 September 2005, just a day before the bye‐elections, the High Court gave a landmark ruling on the practice. While nullifying the practice, the High Court in Banjul ruled against the electoral commission on the grounds that their practices could enable fraud. (Senghore Reference Senghore2012: 516–517)

This evidence suggests that the fiercely protected independence of the judiciary has enabled it to challenge government‐backed actors seeing to skew the electoral process in their favour. While since 2012, election integrity has deteriorated again, between 2002 and 2011 the judiciary appears to have been able to function as an alternative accountability institution, guaranteeing relatively high levels of election integrity in the absence of impartial electoral management.

Media independence in Madagascar

The case of Madagascar shows that media can play a crucial role in publicising electoral misconduct and mobilising calls for electoral reform, helping to maintain relatively high levels of election integrity in a context of lacking EMB autonomy. Media activism has long characterised the politics of Madagascar. The island state maintained a multiparty regime for 14 years following independence in 1960 – longer than most other African states (Bratton & Van de Walle Reference Bratton and de Walle1997: 145). In 1975, the country adopted a state socialist system built on an alliance with the Soviet Union. Like many African states, Madagascar (re‐)democratised at the end of the Cold War, though the Malagasy transition was turbulent. A loose coalition of media organisations and church‐linked activists collectively called forces vives demanded opposition representation, staging demonstrations starting in 1991 and culminating in 1992 in a month‐long strike that brought to a (temporary) end the 17‐year authoritarian rule of Admiral Didier Ratsiraka. A transitional government was put in place prior to the adoption of a new constitution by referendum in 1992 and a presidential election in 1993 in which Ratsiraka lost to Albert Zafy.

President Zafy oversaw a period of relative media freedom between 1993 and 1996 (Randrianja Reference Randrianja2003) before being impeached amid corruption allegations and economic crisis. Ratsiraka subsequently won the 1996 election and ruled for another six years in what became an increasingly one‐party state (Randrianja Reference Randrianja2003). Towards the end of the century, media and civil society experienced a revitalisation in opposition to Ratsiraka's rule (Marcus & Ratsimbaharison Reference Marcus and Ratsimbaharison2005: 504) and Malagasy politics once again entered an unstable period. The 2001 presidential election resulted in a contested outcome, with the challenger Marc Ravalomanana proclaiming victory after the first round and the incumbent Ratsiraka insisting on holding a second round of voting. There followed several months of protests and violent demonstrations against electoral manipulation before Ratsiraka finally fled abroad (Randrianja Reference Randrianja2003; Thompson & Kuntz Reference Thompson, Kuntz and Schedler2006). In 2009, Ravalomanana was in turn ousted in what was effectively a coup by Andry Rajoelina, which heralded the start of a four‐year period of greater authoritarianism.

Throughout the 1990–2009 period, de facto EMB independence in Madagascar scored below 1.3 on the 0–4 scale employed here, indicating that electoral authorities remained under considerable partisan control (see Table 3). Yet, during this time, the country held seven elections (1992, 1993, 1996, 1998, 2002, 2006 and 2007) that, while not perfect, nevertheless exhibited reasonable levels of electoral integrity: on the 0–4 scale employed here, the scores for these elections were all higher than 2, the midpoint of the scale.

While the judiciary has increasingly fallen under political control in this period, media and civil society have generally been able to operate freely and independently. Throughout the 1990s, the media received a score of 2 (free) in all but the 1993 election, when its CIRI score was 1 (intermediate). Media independence was bolstered significantly by the establishment and vigorous use of private radio stations by the opposition from 1991 onwards, and these media played a large role in the movement that overthrew Ratsiraka at that time (Andriantsoa et al. Reference Andriantsoa2005; 1945). Freedom of expression was codified in the 1992 constitution, ushering in a new era of media openness that sustained elections of relatively high integrity. Independent media have also been credited with helping to spur Ratsiraka's ultimate acceptance of electoral defeat in 2002 (Andriantsoa et al. Reference Andriantsoa2005; Randrianja Reference Randrianja2003; Thompson & Kuntz Reference Thompson, Kuntz and Schedler2006). The link between electoral integrity and media diversification is demonstrated in a detailed study by Andriantsoa and colleagues, who conclude that diversity within the privately owned national media has assisted competition and democratisation (Andriantsoa et al. Reference Andriantsoa2005: 1954). In another study, Moser (Reference Moser2008) finds that radio and television access enable voters to resist vote‐buying attempts. All three forms of media (i.e., radio, television and newspapers) thus safeguarded electoral processes by maintaining spaces for dialogue and opposition voices. In the Madagascar case, it has thus been the collaboration between media, (church‐based) civil society organisations and the opposition that created the forces vives that have been crucial in sustaining relatively high levels of election integrity throughout this period.

Civil society independence in Guinea‐Bissau

Guinea Bissau is one of the poorest and most ethnically diverse societies in Africa. In recent years it has also been plagued by civil‐military conflict, drug‐trafficking and weak state institutions. The small West African country won independence from Portugal in 1974, following a 13‐year war of liberation. The liberation movement PAIGC (African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde) subsequently went on to rule the country through the 1980s and 1990s, initially under a state socialist system and, after 1994, in a more competitive and open environment. Violence continues to figure prominently in Guinean politics, with coups occurring in 1998, 2003 and 2012. However, since 1994, Guinea Bissau has regularly held multiparty elections that have, despite some failings, been recognised as generally fair (EUEOM 2005, 2009; Fistein Reference Fistein2011; Ostheimer Reference Ostheimer2001: 46). Indeed, the elections in Guinea Bissau score consistently above 2 in terms of election integrity throughout the 1990–2012 period (Table 3).

One of Guinea Bissau's main problems is the extreme weakness of its state institutions, which enables political actors to harass their opponents and critical media outlets, often with impunity (Ferreira Reference Ferreira2004: 48; Ostheimer Reference Ostheimer2001: 51–52). Judicial independence has been severely lacking throughout the post‐transition period (Ferreira Reference Ferreira2004; Ostheimer Reference Ostheimer2001: 52). Likewise, the electoral management body has been criticised for being partisan (EUEOM 2005: 15; EUEOM 2009: 17). As evidenced by the data presented in Table 3, EMB autonomy was slightly above the midpoint of the 0–4 scale in 1994, after which it fell to the lower half of the scale and remained there for the rest of the period under analysis. At the same time, the score for electoral integrity remained firmly in the upper half of the scale throughout the period, with an election year average of 2.43 on the 0–4 scale.

One of the clues to this discrepancy lies in the strength of Guinean civil society. Five of seven election years in the period under analysis have received a score of ‘2’ on the 0–2 civil society index, indicating that there are few obstacles to grassroots organisation and activity. In the context of weak elite institutions, civil society has on several occasions provided a rough‐and‐ready means of holding political actors to account and preventing the worst forms of abuse of power. Trade unions and religious groups were involved by the government in postwar reconstruction in the 1990s as well as in forming the transitional government after the 2003 coup (Ferreira Reference Ferreira2004: 47–49).

Though the activity of such organisations is at times not as ‘civil’ as is the norm in fully democratic settings (Fistein Reference Fistein2011), the evidence suggests that civil society has played a prominent role in helping to maintain electoral integrity, particularly in recent years. The report of the 2005 European Union electoral observation mission to Guinea Bissau commends the activities of a coalition of 40 several civil society organisations that undertook activities to promote peaceful elections and engaged in informal election observation (there being no formal provision in the law for domestic election observers) (EUEOM 2005: 30–31). The report of the 2009 EU election observation mission likewise notes that:

Despite this restriction on domestic observation, civil society organizations have developed a positive and pro‐active attitude towards supporting actions to reduce instances of violence or of lack of material during the election period. (EUEOM 2009: 33)

Guinea Bissau is thus an example of a country where lack of state capacity represents a significant challenge for electoral administration; in this context, pressure from a forceful civil society has helped to ensure that elections are carried out in a relatively free and fair manner.

These three cases have demonstrated the causal mechanisms at play according to the core argument advanced by this article, illustrating how independent judiciary, media and civil society can compensate for lacking EMB autonomy. In The Gambia, the judiciary fought hard and with at least partial success to maintain its independence in the context of a dominant party regime that succeeded in repressing both civil society and the media. This relative independence served to bolster electoral integrity at key junctures. In Madagascar, election management was highly politicised, and in recent years the judiciary also has fallen under political control, but a robust media – in close collaboration with civil society organisations – has worked to help maintain passable levels of electoral integrity in the period under analysis. Finally, in Guinea‐Bissau, lack of state capacity generated an electoral governance vulnerability that civil society has in part addressed.

Conclusion

This article has argued that deficiencies in electoral management can to a great extent be compensated for via other institutional and societal checks: an active and independent media and/or an active and independent civil society and independent judiciary. Flawed elections are most likely to take place when all three institutional checks fail in key ways. In the electoral sphere, the electorate holds the government to account, and EMBs hold electoral actors to account for the actions they undertake as part of the electoral process. Yet all too often, this formal mechanism is vulnerable to political manipulation, which is why the other accountability agents analysed here are so important in promoting electoral integrity.

The findings presented here show that the presence of independent media, civil society and judiciary are especially important for electoral integrity through their direct effects on enhancing electoral integrity, as well as providing compensating checks on electoral conduct if EMB independence is low. Even if administrative institutions of oversight are failing, other institutions can provide substitutes and help ensure that elections are relatively clean.

Our finding that alternative oversight institutions can compensate for poorly performing administrative institutions has important implications for electoral assistance, demonstrating that in circumstances of limited EMB independence, strengthening other oversight institutions may be helpful to improve electoral integrity. Hence, when emphasis is laid exclusively on EMB independence while ignoring the role of the media, the judiciary and civil society in providing checks on electoral conduct, assistance efforts may be of limited success. A more joined‐up approach that integrates the entire spectrum of relevant actors stands a far greater chance of sustainably improving electoral integrity.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix “Getting away with foul play”