Introduction

The process of the European Union's political integration has long struggled with the development of a common foreign policy, the assumption being that such a development would help the EU to enhance its international role. This is explicitly mentioned in successive EU strategic documents, from the 2003 European Security Strategy to the 2022 Strategic Compass, that refer to the indispensability of a common foreign policy outlook and to outreach, that would help the EU to ‘punch above its weight’. After all, to a large extent, the institutional novelties in the Lisbon Treaty – with the establishment of both the double-hatted High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and Vice-President of the European Commission (HR/VP) and the European External Action Service (EEAS) – were envisaged for this purpose. The underlying idea has been to portray the EU as a cohesive foreign policy actor, enhancing its visibility in world affairs and especially in international organizations (IOs).

Setting aside the feasibility or even desirability of such a development, the fact is that this quest evolves in parallel with the national foreign policies and priorities of the EU member-states. Thus, unsurprisingly, EU member-states continue to be active as independent entities in IOs. Even in cases where the EU manages to articulate a single position in an IO, EU member-states often take the floor to make statements of their own, and occasionally even vote in less than full alignment with the officially expressed EU position on an issue. What drives such a course of action by EU member-states, and why do some member-states opt to differentiate themselves more than others?

This is an interesting research question which contributes to the theoretical discussion on differentiation in the EU's external interactions (Amadio Viceré & Sus Reference Amadio Viceré and Sus2023; Klose et al., Reference Klose, Perot and Temizisler2022; Grevi et al., Reference Grevi, Morillas, Soler i Lecha and Zeiss2020). The terms ‘differentiated cooperation’ and ‘differentiated integration’, although not identical in content and conceptualization, capture the essence of the differentiated foreign policy cooperation between member-states that supplements or complements the initiatives of EU institutions, leaving space for the expression of national sensitivities (Alcaro & Siddi, Reference Alcaro and Siddi2021). This approach adopts a more positive stance towards the reality of member-states’ heterogeneity and their divergence in foreign policy preferences and priorities. Differentiation is not necessarily perceived as undermining the much-fought-for ‘generated coherence’ of EU foreign policy action (Blavoukos et al., Reference Blavoukos, Bourantonis and Galariotis2017; Gebhard, Reference Gebhard, Hill, Smith and Vanhooonacker2017), but rather as enabling member-states to voice their concerns rather than blocking the adoption of a common EU foreign policy stance altogether.

In this article, we address differentiation in EU foreign policy by focusing on the UNGA and the presence of EU member-states in this ‘town square of international politics’ (Abbott & Snidal, Reference Abbott and Snidal1998, p. 24). We operationalize ‘differentiation’ through an analysis of individual oral interventions by EU member-states in the deliberations that occur at the UNGA Plenary and the Main Committees.

Most empirical studies pertaining to the EU's role in UNGA look at the voting records of the EU member-states in order to examine the EU's consistency as a regional bloc in various voting contexts (Burmester & Jankowski, Reference Burmester and Jankowski2014; Galariotis & Gianniou, Reference Galariotis, Gianniou, Blavoukos and Bourantonis2017; Jin & Hosli, Reference Jin and Hosli2013; Luif, Reference Luif2003; Panke, Reference Panke, Blavoukos and Bourantonis2017a; Rees & Young, Reference Rees and Young2005). More recent studies have shifted attention to the EU's oral interventions in UNGA, (Baturo et al., Reference Baturo, Dasandi and Mikhaylov2017, Blavoukos et al., Reference Blavoukos, Bourantonis, Galariotis and Gianniou2016; Galariotis & Gianniou, Reference Galariotis, Gianniou, Blavoukos and Bourantonis2017). This methodological approach sheds light on the pre-voting stage in UNGA debates during which the EU and EU member-states articulate and promote their official objectives prior to the final voting procedures. However, these studies place their emphasis on the impact on EU coherence, whereas our research focuses on and accounts for the motives underlying such differentiation by examining the drivers of individual EU member-states’ activity in UNGA.

Analytically, we identify four types of drivers: structural, institutional, political and thematic. The first type refers to structural features of an EU member-state, operationalized through its size (in terms of population) and its financial resources (captured through states’ Gross Domestic Product [GDP]). The institutional parameter captures the effect of a country's fulfilment of an institutional role, such as holding the EU rotating Council Presidency (henceforth Presidency). Given the mandate of the chairmanship institution, it is natural that the country-holder of this office will take the floor by default more often than the other members of the group during its period in office. However, the question is whether the country in office is taking advantage of its institutional role to be more assertive and issue more statements in an individual capacity, thus differentiating more than the other member-states. The political parameter is associated with the political status and aspirations of a country, operationalized through its candidacy for the UN Security Council (UNSC) and eventual membership of it. The underlying logic is that permanent and non-permanent UNSC members become more vocal at UNGA prior and upon their election, reflecting their special status as members of the most significant UN political body. Finally, despite its temporality, ad hoc nature, and high degree of variability, thematic assertiveness is also included in our analysis. Exogenous crises, like regional security imbroglios, fluctuations in migration flows, critical junctures in global environmental governance and others that trigger intensive and extensive debates at UNGA cannot be accounted for in a systematic way. However, we can and do include the agenda item parameter in our analysis by means of UNGA Main Committees’ thematic differentiation. In the three-layered structure of our multilevel data, our third data layer is the five UNGA Main Committees, each of which deals with different issues.Footnote 1 Methodologically speaking, if variation in the number of oral interventions per country across Committees is identified and is shown to be statistically significant, we can then deduce that agenda items affect EU member-states’ decisions to take the floor at UNGA.

In the next section, we elaborate first on the concept of differentiation in EU foreign policy and the exact modus operandi of the EU in the UNGA. Following that, we analyse the four drivers of states’ international political engagement and articulate the derived hypotheses. Then we present the dataset and the model that will be used, discussing the results of our statistical analysis. We conclude by revisiting the drivers and highlighting pathways for future research.

EU Member-states’ differentiation in UNGA

EU foreign policy is the outcome of a single institutional framework involving member-states and EU institutions in either an ‘intergovernmental’ or ‘Community’ policy-making method (Keukeleire & Delreux, Reference Keukeleire and Delreux2022, pp. 77–79). However, often convoluted by decision-making bottlenecks and preference heterogeneity, this by no means suggests the emergence of a single EU foreign policy identity. External-representation-wise, the modalities vary significantly across policy domains in accordance with the related intra-EU division of competences, as well as across IOs and their internal modus operandi (Dijkstra & Van Elsuwege, Reference Dijkstra, Van Elsuwege, Blockmans and Koutrakos2018). Early accounts of EU foreign policy rejected its ‘singleness’ on the assumption that the EU is more appropriately analyzed as a non-unitary or disaggregated entity in world politics (White, Reference White, Tonra and Christiansen2004, Reference White1999). The gradual build-up of the EU foreign policy acquis, and especially the pursuit of the ‘single voice’ mantra from the 2003 European Security Strategy onwards, reinvigorated the discussion about EU foreign policy ‘singleness’. However, this turn did not come without critiques that focused inter alia on the problematic universal applicability and normative appropriateness of such ‘singleness’, highlighting cases in which orchestrated polyphony can deliver better results (Gstöhl, Reference Gstöhl, Mahncke and Gstöhl2012; Macaj & Nicolaidis, Reference Macaj and Nicolaidis2014; Smith, Reference Smith2017). Needless to say, what is gained by polyphony in terms of effectiveness is lost in terms of political imagery, since it dilutes the impression of the EU as a unitary foreign policy actor. This is especially true in cases of converging, rather than diverging views: after all, the constituent EU member-states enjoy an undeniable right to the latter.

‘Differentiated cooperation’ and ‘differentiated integration’ imply a given level of cooperation or integration that serves as the benchmark from which member-states may deviate (Lavenex & Križić, Reference Lavenex and Križić2019). The positive assumption underpinning this particular phraseology is that some member-states opt in to enhanced cooperation, which, in the field of EU foreign and security policy, may help overcome in-built institutional shortcomings related inter alia to unanimity decision-making rules (Alcaro & Siddi, Reference Alcaro and Siddi2021). At the same time, though, ‘negative differentiation’ may also occur, with member-states following the opposite course of action and diverging from the policy acquis, either in a potentially penalizable breach of existing EU legislation or in a politically criticizable act of differentiation in thematic fields where no legal acquis exists – foreign and security policy, for example (Howorth, Reference Howorth2019; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2019). Setting aside analytical and conceptual contributions to the impact of differentiation on the EU's global role (Rieker, Reference Rieker2021), studies have focused on the effectiveness, accountability and legitimacy of differentiation in EU foreign and security policy (Siddi et al., Reference Siddi, Karjalainen and Jokela2022), as well as the external factors that generate it (Onderco & Portela, Reference Onderco and Portela2023). We contribute to this literature by looking at the inner (i.e. member-state-related) drivers of foreign policy differentiation.

Our empirical focus is on the UNGA political setting, and more specifically the individual oral interventions of EU member-states in that context. Prior to the 2009 Lisbon Treaty amendments, the Presidency primarily represented the EU in UNGA. The Commission was responsible for topics for which it had exclusive competence, such as economic and trade issues. The double nature of the EU representation in UNGA was clearly established and structured in such a way as to maximize the EU's influence. By UNGA custom, state representatives that take the floor on behalf of regional groupings, such as the EU, enjoy preferential speaking rights, leading the discussions and intervening in the first speaking slots, typically before any other UN member. This is a very important feature because, by speaking at an early phase, the EU had the opportunity to take the lead and significantly influence the scope and tone of UNGA political debates. However, the Lisbon Treaty unintentionally annulled these advantageous rights enjoyed by the Presidency and downgraded the EU as a result. Since the EU spokesperson was an official from the EU delegation and not a member-state diplomat, (s)he would be among the last subscribed speakers in the order of the interventions, as entailed by the observer status bestowed on the European Community in 1974. This would have had a significant negative impact on the EU's visibility as a regional bloc in the UN setting (Serrano de Haro, Reference Serrano de Haro2012, pp. 8–11). To redress that, the EU orchestrated an attempt to preserve its privileged status by means of Resolution 65/276 bestowing specific rights on the EU. After a first failed attempt, the EU was eventually successful in creating conditions conducive to the EU enhancing its political status in UNGA (Blavoukos et al., Reference Blavoukos, Bourantonis and Galariotis2017; Guimarães, Reference Guimarães, Koops and Macaj2015).

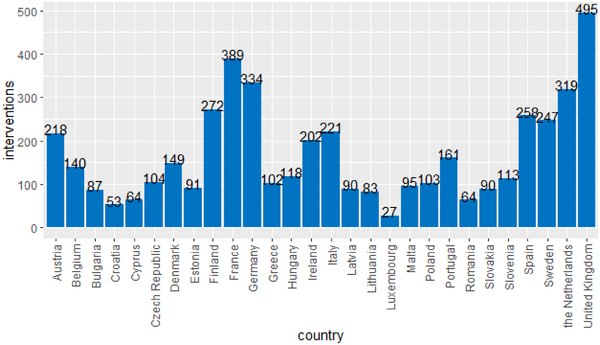

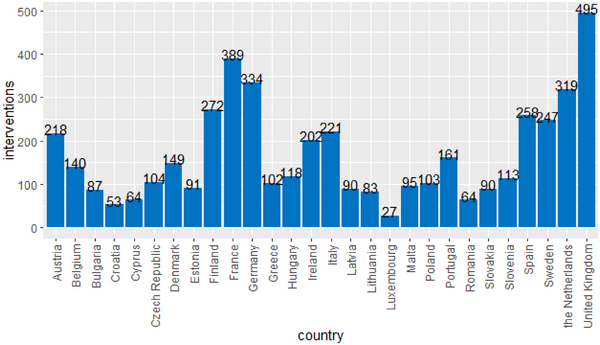

Although more than 10 years on from this development, EU coherence and visibility in the UNGA continues to fluctuate, there is no denying the fact that the EU – as a collective political entity – is more active in UNGA than before the Treaty of Lisbon and Resolution 65/276. This is mainly due to the increasingly important role played in New York by the EU delegation, which has become – not uncontestedly– the EU's main institutional interlocutor and representative at the UNGA (Gatti, Reference Gatti2021). At the same time, though, EU member-states do not refrain from exercising their individual right of speech. Looking at the numbers of individual interventions from 1998 to 2017, it is easy to discern considerable variance in the frequency of oral statements delivered by individual EU member-states, with a few being far more vocal than others (Figure 1). The UK (pre-Brexit) and France are the states with the highest number of interventions, followed by Germany, the Netherlands and Finland. The fact that EU member-states continue to treasure and exercise their individual right to speak in UNGA requires a closer look.

Figure 1. The number of oral interventions made by EU Member-States in the UN General Assembly (1998−2017)

Drivers of states’ international political engagement: Why some states are more active than others in UNGA?

Does size matter?

Both liberal and realist accounts of international relations ascribed a mostly significant role to size in determining a state's influence in international politics (Keohane, Reference Keohane1969; Vasquez, Reference Vasquez1998). Without ignoring several caveats and conditions that exist in the literature, size – in terms of territorial scope, demographics and national product – is a prerequisite for the more efficient supply of the public good of security. It also generates economies of scale, increases the endogenous growth potential of a state, and contributes to the internalization of negative externalities (Alesina & Spolaore, Reference Alesina and Spolaore2003).

In IOs, the legal organizational principle of the ‘equality-of-states’ ensures the formal right of participation, but does not remedy the asymmetry between states of different size and resources. IOs mirror the global state stratification, helping larger states to transform their structural – political and economic – power into influence in international politics (Clark, Reference Clark2011). However, even the smallest members can shape the agenda of IOs and impact on their course of action. Their influence relies on the IOs’ need to be inclusive in order to boost their international legitimacy and relevance. An illustrative example is the role played by small, developing island states in environmental negotiations (Corbett et al., Reference Corbett, Yi‐Chong and Weller2021). Even at the UNSC, small states can have an impact based on their internal competence, which derives from high expertise and issue knowledge, and from their perceived neutrality or reputation as norm entrepreneurs in particular policy fields (Thorhallsson, Reference Thorhallsson2012).

In the UNGA context, size-related variables have a clear impact on a country's ability to actively participate in the deliberations and negotiations held therein, although they do not automatically guarantee success. Bigger and wealthier states can afford more resources to support larger delegations, monitor the ongoing diplomatic interactions better, provide up-to-date information back to their capitals and respond swiftly to any issues raised in situ (Panke, Reference Panke2014). For example, large and powerful states on the UNSC, and permanent members in particular, can grasp the opportunity provided by UNGA public debates to claim legitimacy for the UNSC and restate the appropriateness of the current institutional architecture that serves their own interests and their role in it (Binder & Heupel, Reference Binder and Heupel2015, Reference Binder and Heupel2021).

In that respect, our first set of hypotheses is based on the assumption that influence in international relations and the intention to exercise it are linked – to a significant but not exclusive degree – to size and resources. The more populous and richer a country is and the more structurally powerful it is, the more active we can expect it to be in international affairs, with this activity manifesting inter alia in more intense participation in UNGA deliberations.

1a Hypothesis

The higher the GDP of an EU member-state, the higher the number of individual oral interventions this country makes in UNGA debates.

1b Hypothesis

The larger the population of an EU member-state, the higher the number of individual oral interventions this country makes in UNGA debates.

Representing regional organizations in UNGA

Regional organizations (ROs) are no newcomers to the UN architecture. At the UN founding conference in San Francisco in 1945, there was already considerable pressure to accommodate them within the UN universal framework. The exact conditions of this interrelationship are outlined in Chapter VIII of the UN Charter, testifying to the supremacy of universalism over regionalism (Fawcett, Reference Fawcett, Fawcett and Hurrell1995). Today, ROs constitute fundamental pillars of the key deliberative process at the UNGA. Several factors have contributed to their growing relevance, including interest homogeneity among their constituent member-states, a sense of collective identity, similar views on the norms of governance of the international system, and the existence of a hegemon or a group of states that can provide leadership through moral and material resources (Barnett, Reference Barnett1995, pp. 420–3). Unless explicitly provided for otherwise, the RO Presidency assumes the role of a collective institutional representative of the group of states that form the RO on a rotational, permanent or hybrid basis. In this way, the chairmanship institution provides a functional response to the collective action problem of representation failure (Tallberg, Reference Tallberg2006, pp. 27–40).

Following the Lisbon Treaty, as an RO, the EU has changed the form of its institutional representation at the UNGA, introducing the HR/VP alongside the Presidency at the top of a hierarchical pyramid that includes the EEAS and the EU Delegations around the world. In practice, this has meant that a new EU port parole has partly replaced the EU member-state holding the Presidency in its role of expressing the formal EU position at the UNGA. However, the Presidency has not disappeared from the picture and still remains part of the EU institutional representation in UNGA (Blavoukos et al., Reference Blavoukos, Bourantonis, Galariotis and Gianniou2016).

Our second hypothesis is linked to the rotating EU Presidency. More specifically, we wonder whether holding the 6-month Presidency has an effect on the assertiveness of the country in office in UNGA, resulting in an increase in the number of statements made individually, that is, not in the country's official Presidency capacity. We anticipate that the member-state holding the Presidency will leverage the opportunity it provides to make more oral interventions. Hence:

2 Hypothesis

When a member-state holds the Presidency, the number of oral interventions it makes on its own account will increase compared to those periods in which it is not in office.

Political aspirations

IOs are not only convenient arenas for states to pursue their material interests in, but also fora that bestow symbolic power and international prestige on their members. Being elected to one of the non-permanent seats on the UNSC entails that the state is interacting with the ‘top players in the game’. Prestige and status-seeking are frequently mentioned by diplomats as the primary reasons that are assumed to underlie other countries’ pursuit of non-permanent status (Ekengren et al., Reference Ekengren, Hjorthen and Möller2020). Besides the Charter-enshrined powers of UNSC, it is its high social status, based on its deep pool of ‘social capital’ and the deriving acknowledgment from the international community, that makes this organ such a significant actor in international politics. A seat on the Council is a ‘source of authority-by-association’, reflecting some of the authority the UNSC possesses by virtue of its perceived legitimacy onto the non-permanent member that occupies the seat in question. Even temporary UNSC membership allows states to advance their status by associating themselves with the aura of the Security Council (Hurd, Reference Hurd2002).

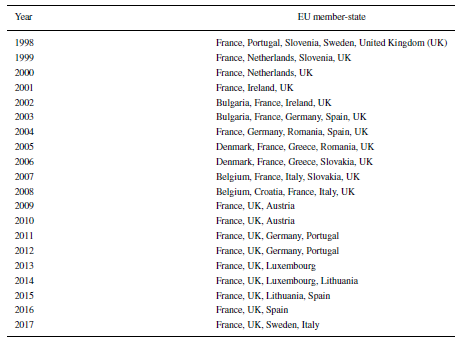

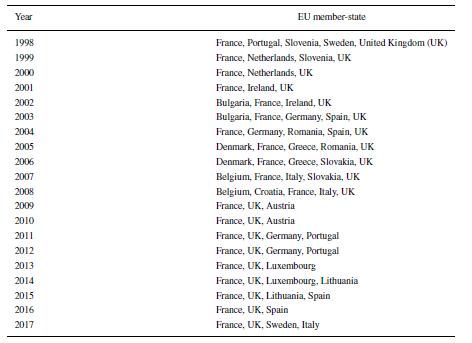

For these reasons, states invest heavily in these non-permanent seats, entering into lengthy and costly electoral campaigns to ensure the necessary support. Jockeying is much more intense in the Western European and Other Group (WEOG);Footnote 2 the competition for the two UNSC seats allocated to this Group is so fierce that many would-be members announce their candidacies well in advance to pre-empt competition. In these campaigns, many factors play a role, including the country's reputation, the campaigning platform, whether the seat is contested or not, but also the diverse strategies of the candidates, their active courting of the electors, and the commitment of financial and other resources (Malone, Reference Malone2000). Other explanatory factors include the peace norm, a state's relationship to powerful countries, as well as population size and the norm of turn-taking. The role of foreign aid and cultural traits are also considered to influence the final electoral outcomes, though the evidence here is inconclusive (Dreher et al., Reference Dreher, Gould, Rablen and Vreeland2014). Table 1 presents the list of EU member-states that occupied a permanent or non-permanent seat on the UNSC for the period under study (1998–2017).

Table 1. EU Member-states on the UNSC (permanent and non-permanent) (1998-2017)

In an effort to raise their visibility and maximize their chances of election, candidates for a UNSC non-permanent seat tend to take the floor at UNGA more often. Electoral success and the deriving higher status acquired puts additional pressure on states to engage actively in UNGA deliberations. Hence, we hypothesize that, for an EU member-state, non-permanent membership of UNSC will positively correlate with the state's oral interventions in UNGA during their period in office. The same holds on a continuous base for the two permanent members (France and the United Kingdom, the latter being treated as a full member of the EU, given that the period under examination ends just 1 year after the Brexit referendum). In this respect, the third set of hypotheses we will be testing are the following:

3a Hypothesis

The participation of a country in UNSC is positively associated with the number of oral interventions made by that country.

3b Hypothesis

A country being a candidate for UNSC membership is positively associated with the number of oral interventions made by that country.

Thematic differentiation

Superpowers and states with a global outreach have a say on all agenda items. However, most UN members are small or medium-size states that prioritize their resources to have an impact on the issues that matter most to them. These issues can be regionally focused or have a global dimension but be of particular interest to these states: climate change, the Responsibility to Protect or human rights, for example. This is especially true of the General Debate that occurs every September in New York, at which states freely express their perspectives on issues deemed important, including the most contentious ones (Baturo et al., Reference Baturo, Dasandi and Mikhaylov2017, Hecht, Reference Hecht2016). This is equally true of special debates organized at UNGA, like the two formal debates on the Responsibility to Protect, in 2009 and 2018, in which states participated in varying degrees according to their own perceptions and endorsement of the norm (Ercan, Reference Ercan2019).

Stemming from the above, it is reasonable to expect that, when such issues are included in the UNGA agenda, they will attract the attention of those countries mostly affected by or interested in them. These states will most probably intervene in the discussions, taking the floor and expressing national or even regional views on the topic. In an interesting quote by a diplomat involved in UN politics, ‘[w]e are a peacekeeper country, so we will be following peacekeeping-related meetings but then there will be a whole other range of things, that are priorities of other countries so we let those countries shepherd the processes or be active in those processes’. Another diplomat commented on the importance of the agenda item under discussion and the state's need to prioritize participation in the evolving deliberations and negotiations, saying that ‘…[f]or my country it's climate change … I don't care about Sudan or Responsibility to Protect, I don't care about anything else’, (as quoted in Panke, Reference Panke2017b, pp. 246–247). Hence, the thematic differentiation of the deliberation will affect the number of oral interventions by states at UNGA. In that respect, our fourth hypothesis is the following:

4 Hypothesis

EU member-states will vary significantly in the number of oral interventions they make in the different UNGA Main Committee and Plenary debates.

Dataset and model

Dataset

The ‘EU oral interventions’ comprise the full set of statements delivered by both the EU Delegation in New York and EU member-states during UNGA Plenary and Main Committee meetings. They are clustered into five different groups: (a) EU Delegation interventions; (b) Presidency interventions; (c) interventions by the EU member-state holding the Presidency, but in an individual capacity; (d) interventions by EU member-states – other than the Presidency – in the presence of an official EU position which they align with or notFootnote 3; and (e) EU member-states’ statements made in the absence of an EU common position. Of these five clusters, the last three comprise the empirical base of this article and the first two the benchmark upon which differentiation is assessed.

There have been several efforts in the broader field of politics to apply innovative methodological techniques and develop computational tools for content analysis. These have mostly been used in the analysis of party manifestos, in which case they extract policy positions from political texts (indicatively, see Laver, Reference Laver2014; Laver et al., Reference Laver, Benoit and Garry2003; Slapin & Proksch, Reference Slapin and Proksch2008). However, in the field of International Relations (IR) and Foreign Policy Analysis (FPA), these techniques have seen only marginal use, and the same holds for EU foreign policy analysis with a very few – albeit notable – exceptions (Baturo et al., Reference Baturo, Dasandi and Mikhaylov2017; Chelotti et al., Reference Chelotti, Dasandi and Mikhaylov2022).

We rely on a recently developed dataset that mines data from the debates held in UNGA from 1998 to 2017. More specifically, this dataset compiles all the verbatim records for the UNGA Plenary and Main Committee meetings between the 53rd and 72nd sessions. It covers all UN member-states, as well as legal entities that participate in UNGA debates without having a state status. For our analysis, we shall focus only on the EU member-states’ oral interventions. It is enabled by the availability from 1998 onwards of data in an electronically readable format compatible with automated text-analysis techniques.

Our dependent variable is the total number of oral interventions per year per EU member-state. In total, our dataset consists of 2802 country-year observations and has the structure of a time-series cross-sectional dataset, since each unit (i.e. country) is fixed and followed for several years. The starting period for the oral interventions of each EU member-state is the year of its official accession to the EU. We control for five different independent variables in our study: the GDP of each EU member-state, the population size of each EU member-state, the effect of holding the Presidency, the participation (or membership) of an EU member-state in the UNSC, and the candidacy of an EU member-state for the UNSC. The participation in UNSC, the candidacy in UNSC, and the Presidency constitute binary variables. The GDP and population size for each country have been gathered by the World Bank database.Footnote 4 Finally, the effect of thematic differentiation is captured by the five Main Committees dealing with specific thematic policy agendas in the UNGA. Thematic identification is usually addressed by means of topic modelling employed to identify clusters of ‘topics’ from text as data, such as speeches from the United Nations General Debate (Chelotti et al., Reference Chelotti, Dasandi and Mikhaylov2022) or the European Parliament (Greene & Cross, Reference Greene and Cross2017). Such identification is inherent in our data structure through the topics discussed in each Committee, which enables us to capture thematic differentiation through the three-level model that will be presented in the following section.

Model

There is a rich debate in political science and the statistical literature about which modelling approach is the most appropriate and robust to fit data which are structured as time-series cross-sectional or panel data (Beck, Reference Beck2001; Bell & Jones, Reference Bell and Jones2015). The dataset we have at our disposal is a typical case of a time-series cross-sectional dataset, since we have a fixed number of units (i.e., countries) with repeated annual observations. The dataset is also characterized by a nested structure with the following logic: repeated annual observations on countries (level 1) are nested within countries (level 2), and the countries are nested within the Main Committees of the UNGA (level 3). Hence, the dataset has both a longitudinal and multilevel structure. In this respect, to fully capture the variability across time and between the different levels of the dataset structure, we construct a three-level longitudinal multilevel random intercept model with the following specification:

The level-1 equation is as follows:

where

![]() ${\mathrm{Intervention}}{{{\mathrm{s}}}_{tij}}$ are the oral interventions at time t for each country i nested within each Committee j;

${\mathrm{Intervention}}{{{\mathrm{s}}}_{tij}}$ are the oral interventions at time t for each country i nested within each Committee j;

![]() ${{b}_{oij}}$ is the initial number of oral interventions by country i in Committee j: that is, the expected number of oral interventions for country i in Committee j when the time point is zero;

${{b}_{oij}}$ is the initial number of oral interventions by country i in Committee j: that is, the expected number of oral interventions for country i in Committee j when the time point is zero;

![]() ${\mathrm{GD}}{{{\mathrm{P}}}_{tij}}$ is the predictor of the gross domestic product with the attached

${\mathrm{GD}}{{{\mathrm{P}}}_{tij}}$ is the predictor of the gross domestic product with the attached

![]() ${{b}_{1ij}}$ GDP effect coefficient;

${{b}_{1ij}}$ GDP effect coefficient;

![]() ${\mathrm{Populatio}}{{{\mathrm{n}}}_{tij}}$ is the predictor of the population size with the attached

${\mathrm{Populatio}}{{{\mathrm{n}}}_{tij}}$ is the predictor of the population size with the attached

![]() ${{b}_{2ij}}$ population effect coefficient;

${{b}_{2ij}}$ population effect coefficient;

![]() ${\mathrm{Presidenc}}{{{\mathrm{y}}}_{tij}}$ is the predictor of the Presidency with the attached

${\mathrm{Presidenc}}{{{\mathrm{y}}}_{tij}}$ is the predictor of the Presidency with the attached

![]() ${{b}_{3ij}}$ presidency effect coefficient;

${{b}_{3ij}}$ presidency effect coefficient;

![]() ${\mathrm{UNSC\_membershi}}{{{\mathrm{p}}}_{tij}}$ is the predictor of the participation in the UN Security Council with the attached

${\mathrm{UNSC\_membershi}}{{{\mathrm{p}}}_{tij}}$ is the predictor of the participation in the UN Security Council with the attached

![]() ${{b}_{4ij}}$ the UNSC membership effect coefficient;

${{b}_{4ij}}$ the UNSC membership effect coefficient; ![]() ${\mathrm{UNSC\_candidat}}{{{\mathrm{e}}}_{tij}}$ is the predictor of the candidacy in the UN Security Council with the attached

${\mathrm{UNSC\_candidat}}{{{\mathrm{e}}}_{tij}}$ is the predictor of the candidacy in the UN Security Council with the attached ![]() ${{b}_{5ij}}$ the UNSC candidacy effect coefficient; and

${{b}_{5ij}}$ the UNSC candidacy effect coefficient; and ![]() ${{e}_{1ij}}$ is the residual associated with a country's oral intervention at a specific time point, which is assumed to be normally distributed with a mean of 0 and variance

${{e}_{1ij}}$ is the residual associated with a country's oral intervention at a specific time point, which is assumed to be normally distributed with a mean of 0 and variance ![]() ${\mathrm{Var}}({{e}_{1ij}})\sigma _e^2$.

${\mathrm{Var}}({{e}_{1ij}})\sigma _e^2$.

The level-2 equation is as follows:

where the ![]() ${{a}_{00j}}$ represents the mean initial number of oral interventions for Committee j and

${{a}_{00j}}$ represents the mean initial number of oral interventions for Committee j and ![]() ${{u}_{0ij}}$ is the variation in the initial number of oral interventions among countries within Committees. The

${{u}_{0ij}}$ is the variation in the initial number of oral interventions among countries within Committees. The ![]() ${{u}_{0ij}}$ is assumed to be normal distribution, with a mean of 0, and some variance Var(

${{u}_{0ij}}$ is assumed to be normal distribution, with a mean of 0, and some variance Var(![]() ${{u}_{0ij}}$) =

${{u}_{0ij}}$) = ![]() $\sigma _{u0}^2$. The variance of

$\sigma _{u0}^2$. The variance of ![]() ${{u}_{0ij}}$ indicates the extent to which countries within a specific Committee vary from this specific Committee mean initial status of oral interventions.

${{u}_{0ij}}$ indicates the extent to which countries within a specific Committee vary from this specific Committee mean initial status of oral interventions.

The level-3 equation is as follows:

where ![]() ${{b}_{000}}$ is the grand mean of the initial status of oral interventions, and

${{b}_{000}}$ is the grand mean of the initial status of oral interventions, and ![]() ${{u}_{00j}}$ is the variation in the initial status of oral interventions across Committees. The

${{u}_{00j}}$ is the variation in the initial status of oral interventions across Committees. The ![]() ${{u}_{00j}}$ is assumed to follow a normal distribution, with a mean of 0, and some variance Var(

${{u}_{00j}}$ is assumed to follow a normal distribution, with a mean of 0, and some variance Var(![]() ${{u}_{00j}}$) =

${{u}_{00j}}$) = ![]() $\sigma _{v0}^2$. The variance of

$\sigma _{v0}^2$. The variance of ![]() ${{u}_{00j}}$ indicates the extent to which Committees vary with the respect to the grand mean initial status of oral interventions.

${{u}_{00j}}$ indicates the extent to which Committees vary with the respect to the grand mean initial status of oral interventions.

The combined model is as follows:

This model combines the longitudinal and multilevel features, since the level-1 designates each country's oral interventions over time (i.e., the longitudinal aspect), the level-2 captures the variation across countries in oral interventions within Committees, and the level-3 depicts the variation in the initial status of oral interventions among the Committees (i.e., the multilevel aspects).

Most published studies with a longitudinal and multilevel dataset structure, similar to the one in our study, are based on growth curve analysis models that combine longitudinal and multilevel features including, typically, a time predictor in level-1 equations. These methodological approaches appear more often in the biological, ecological and educational sciences (Betsy McCoach et al., Reference Betsy McCoach, O'Connell and Levitt2006; Hswen et al., Reference Hswen, Qin, Williams, Viswanath, Brownstein and Subramanian2020; Lee & Hong, Reference Lee and Hong2021; de Jong et al., Reference De Jong, Moerbeek and van der Leeden2010; Peugh & Heck, Reference Peugh and Heck2017). Unlike those modelling techniques, we do not include a time predictor in our level-1 equation, but, to grasp any longitudinal dimensions of our level-1 residuals, we account for any heteroscedasticity the level-1 residuals may have and adopt an autocorrelation-moving average correlation structure of order (0, 2). As a result, this model has enough flexibility to fit both the fixed and random variation that may exist across the different levels of the longitudinal and multilevel structure of our dataset.

Results and discussion

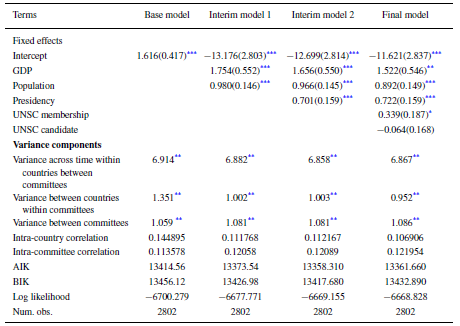

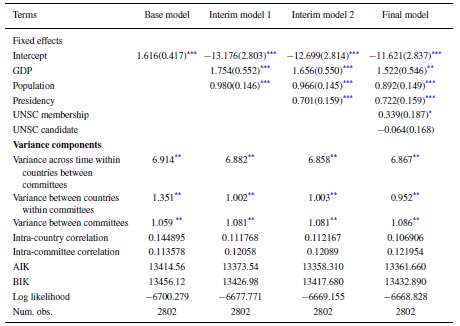

In Table 2, we present the results after running four different versions of the three-level longitudinal multilevel random intercept model. The first version is a baseline model that does not include any level-1 covariate, only an intercept. This base model is useful because it gives us a first feel for an explanation of the variability at the different levels of the nested structure of the dataset. After that, we proceed sequentially by adding covariates. Interim Model 1 has two additional covariates (i.e., the GDP and Population) in addition to the base model. Interim Model 2 adds the Presidency covariate to Interim Model 1. The final model contains all the covariates: GDP, population size, the Presidency and the UNSC participation and candidacy of EU member-states.

Table 2. Models’ results

Note: p = 0.10*, p = 0.05**, p = 0.01***

As far as our first set of hypotheses is concerned, the size of a country, as operationalized through the GDP and population factors, has a positive effect on the number of oral interventions made by states in UNGA throughout the period. Both hypotheses 1a and 1b are therefore modestly confirmed: the GDP and population of EU member-states correlate positively with their tendency to intervene orally in the UNGA debates.

The Presidency has also a positive effect on the individual oral interventions made by EU member-states, although the effect is weak. The country holding the Presidency does tend to make more oral interventions on its own behalf compared to when it does not hold the Presidency. Therefore, hypothesis 2 is also confirmed.

Equally important, the participation of a country in the UNSC is positively – albeit weakly – correlated with the number of oral interventions the country makes in UNGA. However, a country's UNSC candidacy has a negative sign and is not statistically significant. This indicates a misalignment with the expectation of hypothesis 3b, which indicates that a country's candidacy for the UNSC does not actually affect how EU member-states intervene orally in the UNGA. Thus, our third hypothesis is confirmed only partially, since the participation of a country in the UNSC is positively associated with the same country's oral interventions, whereas its candidacy is not. This is counter-intuitive, in the sense that being active in the UNGA debates might be expected to increase the country's visibility in pursuit of a non-permanent seat on the UNSC. However, this is not confirmed by our analysis. Further qualitative research is required to corroborate this finding, but two plausible explanations exist: first, pre-electoral campaigns in UNGA for a UNSC seat usually take place through bilateral diplomatic channels; and second, open and public debates require extra caution to avoid the ‘hot potatoes’ of international politics and may even become counterproductive, alienating the potential supporters of a candidacy rather than bringing them on board.

The effect of thematic differentiation, as operationalized through varying engagement in the UNGA's Main Committees and Plenary, is also significant, based on the results of our analysis. Unsurprisingly, all the variance components are statistically significant, which suggests that there is significant variance at all three levels of analysis. Looking at the ratio of each variance component to the total variance, already in the base model, more than three-fourths of the total variability is due to differences over time for each country, with the rest of the variance being due to differences between countries within committees (14.4 per cent), that is, intra-country correlations in Table 2, and between committees themselves (11.3 per cent), that is, intra-committee in Table 2. The latter is already a strong indicator of the validity of our argument. The incorporation of level-1 covariates reduces the time component of variability and further increases the variability between committees about 10 per cent. Thus, hypothesis 4 is also confirmed.

Conclusion

Despite the systematic efforts made by the EU to articulate a single voice in UNGA after the Lisbon Treaty, the EU member-states continue to take the floor on an individual basis, either reinforcing or undermining the common EU message. This indicates a considerable degree of differentiation among EU member-states. We have accounted for the motivation behind member-states’ behaviour by controlling the significance of structural, institutional, political and issue-specific factors. Our analysis confirms the significance of structural factors as well as the positive but weak effect of the Presidency. Furthermore, our analysis supports the argument that UNSC membership is also positively correlated with a country's oral statements in UNGA, but does not provide evidence that the UNSC candidacy of an EU member-state can potentially increase its oral interventions in the UNGA. Finally, thematic differentiation plays a role, with EU member-states being more vocal individually on specific issues – judging at least from their varying assertiveness in the Main UNGA Committees.

Our analysis provides useful insights on the member-states component of EU foreign policy. The complicated modus operandi of the EU foreign policy system, especially in IOs and multilateral fora, constitutes a puzzle for many EU international interlocutors. The line between the EU and member-states component is often blurred and hard to identify, let alone account for. Although the relationship between the two components is generally symbiotic, the underlying dynamics of the relationship are often incomprehensible to those who are not Brussels micro-cosmos insiders. This is even more confusing when the two components deliver the same core message. Our study has contributed to a better understanding of the drivers behind individual EU member-states’ interventions in UNGA by identifying structural, institutional, political and thematic drivers.

Of the four drivers, the structural ones are the least amenable to change, given that they entail constitutive features of a state. The other three, however, provide food for thought and areas for action and improvement in terms of EU foreign policy differentiation. Institutional amendments to the Presidency system and the curtailment of its role as an external representative of the EU, which could be taken over fully by the HR/VP and the EEAS, would eliminate one of the identified drivers of differentiation. Far bolder politically, though not feasible in practice, having a single EU voice in UNSC would also largely curtail the individual interventions made by EU member-states in pursuit of their own international aspirations and in fulfilment of their institutional role. Issue specificity highlights the necessity of a far more intense osmosis in the EU foreign policy-making process that would ensure that national preoccupations and priorities are reflected in the EU foreign policy acquis and expressed through the EU single voice.

Mutatis mutandis, the analysis of these drivers also holds for other IOs in which the EU claims a single voice while its member-states are also simultaneously present. Needless to say, of course, the elephant in the room in any such discussion is the heterogeneity between member-states vis-à-vis the extent of EU political integration they would like. Any lack of progress on this front will hamper the chances of a single EU voice in international fora.

Acknowledgements

The manuscript has been greatly improved thanks to Panagiotis Konstantinou for his help with econometric modeling and data management, and Stamatis Stasinos for his assistance with the data cleaning process. We would also like to give special thanks to Dr. Harris Papageorgiou and Dr. Maria Pontiki for their invaluable feedback on data mining the UN verbatim records. Additionally, we benefited from the comments and suggestions of the reviewers and editors.

Open access publishing facilitated by European University Institute, as part of the Wiley - CRUI-CARE agreement.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in article online supplementary material

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: