Between the late 1950s and the early 1970s, the Irish education system experienced a period of unprecedented change. Various reforms were implemented across all levels, which altered the ways that education would be provided and delivered.Footnote 1 Given the scale of these changes, it is regrettable that few studies have expanded their focus beyond the ‘official narrative’. The ‘official narrative’ in this case refers to the approach taken by academics whose analysis is derived solely from official government records. Traditionally, historians of the reform period in Irish education have tended to favour an examination of the official history, documenting many of the changes which occurred through the public lens of the Department of Education and its respective ministers. Although such accounts usually consult a plethora of sources like reports, circulars, memoranda, Dáil debates and personal communications from government officials, the approach is arguably very one-sided. Generally, such studies fail to consider the range of stakeholders involved or other external factors which could impact on policy formation and implementation.Footnote 2 More recently, some academics have extended their analysis to provide an insight into the impact and legacy of particular reforms, specifically the free education scheme of 1967.Footnote 3 While free education is often considered ‘one of the most important developments in the history of independent Ireland’, the level of academic interest in this scheme has largely overshadowed other reforms which were introduced during this period.Footnote 4 There remains a need to develop more nuanced understandings of the individual schemes and initiatives which shaped the course of reform during the long 1960s.

One particular scheme which has been largely overlooked in recent scholarship is George Colley's plans for a comprehensive system within the post-primary sector. Colley was a trained solicitor and an Irish language enthusiast. He was first elected to government in 1961 and served for a brief period as parliamentary secretary to the minister of lands.Footnote 5 But Colley's main interest lay in education and, according to Seán O'Connor, he ‘had made no secret of the fact that he had hoped one day to become Minister for Education’.Footnote 6 On 21 April 1965, that day finally arrived and he approached this role with a clear determination to bring about equality of educational opportunities for all Irish children.Footnote 7 Colley believed this could be achieved through the creation of a nationwide comprehensive system of post-primary education. Colley's plans were based around two central ideas: co-operation and rationalisation. Co-operation required existing secondary and vocational schools working together to pool their resources in order to provide the broadest possible curriculum to all students. Rationalisation involved assessing existing post-primary provisions and removing duplication of services, which in simple terms meant that in a locality wherein two or more schools provided the same level of education, co-operation would have to be introduced or, alternatively, one of the schools would be required to close. In theory, Colley's plans for a comprehensive system seemed practical but, in reality, they were met with much hesitation and confusion, not least because it was the first time in the history of the state that post-primary school authorities were expected to work together.Footnote 8 Colley's decision to establish a Development Branch to assess the existing system in a bid to remove duplication and rationalise resources further hampered progress in the comprehensive scheme as school authorities became increasingly concerned with the future viability of their individual schools. While some academics, most notably Eileen Randles and John Walsh, have provided detailed accounts of Colley's term as minister for education, their analysis of his reforming measures are heavily couched in the language of official government records.Footnote 9 Walsh's study does examine the role and response of the Catholic hierarchy but this top-down approach offers little consideration of how Colley's measures were received or implemented by those who would be most affected by the scheme, namely individual school authorities.

Writing in 2010, Marie Clarke drew attention to the ‘imbalance in the analysis of education policy’. In particular, Clarke cited ‘the lack of attention paid to the role played by the Catholic Hierarchy’ in educational reform and policy decision-making during the 1960s.Footnote 10 However, a further imbalance in existing discourses surrounding the history of Irish education, particularly during the era of reform (c.1957–72), lies in the invisibility of the role played by individual school authorities in shaping and implementing change within the post-primary sector. This is peculiar given that until the mid 1960s the majority of second-level schools were private, voluntary, denominational institutions operated by male or female religious. For example, of the 586 second-level schools in operation in Ireland in 1965, 424 (72 per cent) were owned and managed by Catholic religious teaching orders that were predominantly independent of the Irish government and its Department of Education.Footnote 11 This position of autonomy stemmed from the Free State period. In 1924, the newly formed Department of Education outlined its role in second-level education as limited to curricular reform and laying down specific conditions which schools were required to comply with in order to gain recognition or avail of state grants.Footnote 12 As a result, for the first four decades following independence, secondary school authorities were essentially free to conduct their own affairs. However, this autonomy came under increasing pressure during the 1960s when the government introduced a series of new policy initiatives which altered the traditionally voluntary and independent nature of second-level schooling. Among these initiatives were building grants for secondary schools (1964), the establishment of comprehensive schools (1966), the introduction of free post-primary education (1967) and the development of community schools (1970).Footnote 13 Despite the apparent paradigm shift in departmental policy, few studies have examined how this change in approach impacted on and was experienced by individual school authorities, particularly the large number of religious orders who had been involved in the provision and delivery of Irish education, many since the nineteenth century. This lacuna in scholarship is highlighted by Deirdre Raftery who recently stressed that ‘Research is … … needed into how nuns accommodated the significant changes that were heralded by other changes in Irish social and public life’.Footnote 14

One of the primary reasons that religious orders have been largely absent from discussion of the history of Irish education is because their archives are private. As Raftery et al. explain, ‘only recently have congregations begun to employ trained archivists to catalogue their records and prepare them for researchers’.Footnote 15 The opening of private convent and monastic collections to academics is undoubtedly a welcome development which has the potential to generate a plethora of new research, particularly in the field of the history of education. Another reason why the experience of teaching congregations has not informed recent scholarship is because they simply have not been invited to contribute. Writing in 2009 about the significant absence of teaching sisters from historical scholarship, Bart Hellinckx and colleagues noted that ‘the educational contribution of women religious has received only limited scholarly attention’ and even within that limited space, ‘the “ordinary” teaching sister is almost completely ignored’.Footnote 16 In a recent examination of historical developments since the publication of Margaret MacCurtain, Mary O'Dowd and Maria Luddy's ‘Agenda for women's history in Ireland, 1500–1900’ (1992), Raftery noted how ‘Oral history has made a contribution to our understanding of the lives and work of women religious in the twentieth century … [but] there is scope for further work, gathering the testimonies of sisters’.Footnote 17 However, the task of conducting ethically sound oral history interviews with members of religious orders is a particularly time-sensitive issue due to the ageing population within these communities. Undoubtedly, there is an urgency to record the experiences of religious, particularly of those who lived and worked through some of the most profound changes in Irish society. According to Paul Thompson, oral testimonies enable the historian to investigate a wider scope, compile evidence from an alternative viewpoint and raise new questions that previously were unanswerable.Footnote 18 Perhaps more significantly, Lynn Abrams has argued that oral accounts are a means of ‘subverting the dominant narrative or at least suggesting an alternate one’.Footnote 19 Not only do oral history testimonies add a corroborative element to the archival research process, but more importantly they provide access to an attitudinal and motivational narrative that is not present in official records and documents.Footnote 20 Only though the large-scale and systematic examination of convent and monastic school archives and the careful and sensitive compilation of oral history testimonies with members of teaching congregations can a more nuanced understanding of the history of Irish education be achieved.Footnote 21

In order to address this gap in current scholarship, this article uses the Presentation Sisters as a case study to explore how some independent and voluntary school authorities received, responded and reacted to Colley's announcement regarding co-operation and rationalisation. The Presentation Sisters are a group of native Irish female religious who were founded by Nano Nagle in 1775 for the sole purpose of providing primary education to the poor and labouring classes. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the mission of the Presentation Sisters developed and flourished, and they soon came to offer both primary and secondary education.Footnote 22 At the time of Colley's announcement, the Presentation Sisters were the second largest cohort of female religious involved in the delivery of girls’ second-level education in Ireland, with a total of forty-one secondary schools in operation.Footnote 23 Through a systematic, historical analysis of government files, private Presentation convent archival collections and oral history testimonies with members of the Presentation Order, this article provides a unique insight into how co-operation and rationalisation in the post-primary sector was reconciled at local school level. The analysis exposes the previously hidden history of voluntary secondary school authorities and the role they played in educational reform during the 1960s. The evidence presented will show that, to a large extent, the success of co-operation and rationalisation depended on the willingness of school authorities to accept and comply with departmental directives. This research contributes in no small way to existing discourses regarding the history of the Irish education system and, in particular, provides a new lens through which the narrative of the reform period (c.1957‒72) can be understood.

I

As already noted, for a long time following independence, the government's role in the provision and delivery of post-primary education in Ireland was extremely limited, mostly to outlining specific guidelines which schools were expected to adhere to in order gain recognition as a post-primary school. The government was also responsible for making small grants available for post-primary education and for implementing curricular reforms. However, the state was not involved in founding or financing school buildings, nor was it concerned with major structural or administrative reform within the sector.Footnote 24 Until the 1960s, Irish second-level schools were, therefore, largely autonomous institutions, free to operate within a system which had no universal governing authority. This situation led to the development of a number of issues within the education system. One major problem was the manner in which second-level education was delivered. Until the 1930s, second-level education was primarily only available in traditional secondary schools. These schools, for the most part, were established by voluntary agencies and were generally linked to a specific religious denomination. The type of education provided in these institutions was academic in orientation with a strong religious ethos. Following the passing of the Vocational Education Act in 1930, a separate strand of post-primary education emerged in Ireland. From the outset, the vocational school was seen as an option for those who would enter employment directly upon completion of their second-level education.Footnote 25 As a result, instruction in vocational schools was decidedly more practical and the focus was on developing manual skills which would enable students to gain employment. By the late 1950s, Irish post-primary education was characterised by an apparent separation between the traditional academic orientation of the secondary school and the more practical approach of the vocational school. In 1960, there were 526 secondary schools and 289 permanent vocational schools in operation in Ireland.Footnote 26 At the time, there was virtually no room for co-operation between these two distinct approaches to second-level instruction and ultimately what emerged was a two-tiered system of education.Footnote 27

Another problem associated with the Irish education system at this time was the geographical imbalance in the location of recognised secondary schools. Because the development of secondary schools was largely dependent on the private initiative of individual organisations, there was no specific planning for building in the sector. By 1951, for example, there were 184 recognised secondary schools operating in Leinster and 156 in Munster compared to just sixty-two in Connacht.Footnote 28 Lack of national-based planning meant that there was no means to address the uneven distribution of post-primary schools, an issue which was particularly acute in rural areas throughout Ireland. Moreover, post-primary schools, for the most part, were small: in 1951, there were just fifteen schools in the country which catered for 300 pupils or more, while 247 schools provided education to 100 pupils or fewer.Footnote 29 The size of secondary schools also had an impact on the range of subjects offered and the overall quality of education being provided.Footnote 30 These issues were made more significant by the high levels of pupil withdrawals, which by the early 1960s amounted to more than 3,000 boys and 3,000 girls leaving full-time education annually prior to completing their intermediate certificates (the state-validated examination taken at around age 15–16, at the end of three to four years of secondary education: some pupils then progressed to the leaving certificate, taken at the age of 17–18 following an additional two years of secondary education).Footnote 31

By the late 1950s, these kinds of issues became a growing concern for the government, particularly following the publication of the White Paper on Economic Expansion in 1958, which was quickly followed by the first official programme for economic development.Footnote 32 These reports stressed the importance of investing in education in order to create a stable and profitable economy. The idea that the ‘prosperity of a modern technological society depended on the availability of an educated workforce’ was something which was heavily supported by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (O.E.C.D.), which Ireland joined in August 1961.Footnote 33 Following an O.E.C.D. conference in Washington that October, the Irish government was invited to undertake a pilot study of education in Ireland.Footnote 34 On 29 July 1962, the then minister for education, Patrick Hillery, officially agreed to the study and appointed a team to carry out a survey on Irish secondary education which was expected ‘to assess the educational needs of our expanding economy as well as the economic implications of ever increasing demand for education.’ The survey team appointed by Hillery consisted of Patrick Lynch, lecturer in economics at University College, Dublin; William J. Hyland, of the Statistics Office, United Nations; Martin O'Donoghue, lecturer in economics at Trinity College, Dublin; and Pádraig Ó Nualláin, inspector of secondary schools. Cathal Mac Gabhann of the Department of Education was appointed secretary.Footnote 35 The report, which became known as Investment in education, was completed in 1965 and highlighted the importance of the role which education would and should play in government economic policy in the future. But even before Investment in Education was finalised, the anticipated findings of the report were influencing government decisions around education and reform in the sector.

II

George Colley was appointed minister for education in April 1965.Footnote 36 Like his predecessor, Patrick Hillery, Colley's term in office was influenced by the anticipated findings of the government's Investment in education report which was expected to recommend increased educational opportunity for all children and greater educational planning in the post-primary sector.Footnote 37 In December 1965, Colley released a document which outlined the Department of Education's policy in relation to the future of post-primary education in Ireland which included raising the school leaving age to fifteen by 1970 and provision of up to three years post-primary education.Footnote 38 However, it was his policy on increased educational opportunity which received the most attention and was considered by many as more far-reaching than any programme previously implemented by the Department of Education. Colley's policy centred around the creation of a comprehensive school system within the post-primary sector. Colley's aim was that ‘secondary and vocational schools, by the exchange of facilities and by other forms of collaboration, should make available a curriculum broad enough to serve the individual needs of all their students, and thereby to provide the basis of a comprehensive system in each locality’.Footnote 39 These aims were to be facilitated by a 6 per cent increase in state funding during the year 1965–6, which brought the total allocation for education to £30 million.Footnote 40 However, financial support from the government alone would not guarantee change within the sector. Colley clearly understood that central to achieving a comprehensive post-primary system was securing support from existing secondary and vocational schools.

In an unprecedented move, Minister Colley issued a direct circular to the school authorities in early January 1966. For the first time in the history of the state, the Department of Education were openly engaging with secondary school authorities in negotiations surrounding reform in the education sector. The tone was personal, with Colley stating: ‘I write accordingly to you because I look to you to accord me your full co-operation in the effort to provide for every pupil, to the greatest extent which our resources will allow, an education suited to his needs and aptitudes.’ He praised educational authorities for all they had achieved to date in post-primary education:

I wish to record my appreciation and admiration of the initiative and enterprise displayed by the school authorities, secondary and vocational. As a result of their efforts there are at present in this country some 600 secondary schools and some 300 vocational schools, so that it is now possible to envisage as a practical proposition in the near future the provision of post-primary education for all the children of the country.Footnote 41

Outlining the future of post-primary education in a personal letter, as opposed to announcing it in the Dáil or through the media, was, according to Randles, a ‘tactical move which helped to win a willing response to the requests made by the minister’.Footnote 42 Colley's letter also provided details on the substantive issue of the proposed reforms for post-primary education:

While the time has come when the operation of two rigidly separated post-primary systems can no longer be maintained, this is not to say that secondary or the vocational school need lose its distinctive character. What I have in mind is that there should be a pooling of forces so that the shortcomings of one will be met from the resources of the other, thus making available to the student in either school the post-primary education best suited to him.Footnote 43

In short, Colley hoped to introduce a system of co-operation in the post-primary sector, whereby accommodation and facilities would be shared by secondary and vocational schools in order to provide the broadest possible curriculum and, thus, create a national comprehensive system.

The initial reaction to Colley's co-operation scheme was positive. On 15 January 1966, the Nenagh Guardian expressed the opinion that Colley's proposal was ‘a sensible course for a small nation like ours which needs to get the best value from its resources’.Footnote 44 Charles McCarthy, general secretary of the Vocational Teachers’ Association, said ‘that the Minister's request for local co-operation was most valuable and timely’, while the vice-president of the Protestant Headmasters’ Association, Dr Rex Cathcart, stated that ‘the plan was indeed very creditable and there was nothing about it they could criticise’.Footnote 45 The Irish Press hoped there would be an ‘early and enthusiastic response’ from the managers of secondary and vocational schools to Colley's ‘appeal’ for greater co-operation at post-primary level.Footnote 46 But others, such as the (Catholic) Episcopal Commission for Post-primary Education, were more cautious in their response.

On 3 February 1966, representatives of the Episcopal Commission for Post-primary Education met with Minister Colley in Leinster House to discuss his proposal. In response to the minister's call for increased participation in the post-primary sector, the Episcopal Commission ‘heartily approved the ideal of a suitable post-primary education for all’.Footnote 47 However, a report on the matter noted that, ‘in regard to the Minister's recent circular on collaboration between secondary and vocational schools … the Commission expressed approval in principle but drew attention to many of the problems this collaboration would raise’.Footnote 48 The report did not detail the anticipated problems. However, Randles suggests that these would include practical difficulties, such as the distance pupils would be expected to travel between secondary and vocational schools which would ultimately entail a loss of teaching hours.Footnote 49 Furthermore, the honourable secretary of the Federation of Lay Catholic Secondary Schools, Vincent Russell, predicted that ‘in the case of students attending two schools there would be difficulties regarding discipline’ and travel.Footnote 50 Other issues which would undoubtedly emerge as a result of co-operation included time-tabling difficulties, confusion regarding identification with a specific school community, and co-education.Footnote 51

III

Although there were legitimate practical issues associated with Colley's co-operation scheme, the Minister believed that they could be overcome if careful consideration was given to individual school circumstances. He proposed that ‘in each locality the authorities of the secondary schools … and the vocational schools should confer and formulate proposals on the utilisation of existing accommodation or facilities and, where necessary, the provision of additional facilities’.Footnote 52 Almost immediately following the minister's announcement, the authorities of the secondary and vocational schools in Carlow town met to discuss the possibility of implementing the co-operation scheme. The annals of the Presentation Convent, Carlow, provide an account of that first meeting:

This month brought a letter from the Minister [for] Education [to] all the heads of secondary and vocational schools to meet and discuss such things as accommodation and the interchange of staff and pupils where such interchange was necessary. A preliminary meeting was held in the Parochial House, at which the following schools were represented; Knockbeg College [a Catholic boys’ boarding school outside Carlow], the Christian Brothers, the Mercy Convent, the Vocational school and the Presentation Convent [all in Carlow town]. The talks revealed that there was no ‘spare’ teacher and no spare room in any school, as each was full to its capacity. So handicapped are the vocational authorities for space, that since September 1965, the girls from same have been having their classes in the old school in Tullow Street. The CEO, Mr. A. Waldron, had literally ‘begged’ us to rent the school to them for a term of two years pending the building of a new technical school. It was pointed out that the Presentation Sisters had anticipated the Minister's wishes regarding this co-operation by renting the old school to the vocational authorities for day, evening and night classes. The date for the meeting with the Department's official was not fixed but we were told that it would be in the near future.Footnote 53

This initial meeting in Carlow indicates issues with staff and accommodation shortages but there appears to have been no attempt to make any genuine decisions regarding co-operation. Although the Presentation Sisters indicated that post-primary school authorities were expected to meet to discuss elements of co-operation such as the ‘interchange of staff and pupils’, no such discussions took place in Carlow.

It is worth noting at this point that the idea of co-operation between schools was not unknown to the religious orders involved in the delivery of education. As early as October 1965, the Catholic Church, during the course of the Second Vatican Council (1962‒5), had encouraged co-operation and collaboration among various religious run secondary schools. In Declaration on Christian education, it was stipulated that:

At a diocesan, national and international level, the spirit of co-operation grows daily more urgent and effective. Since this same spirit is most necessary in educational work, every effort should be made to see that suitable co-ordination is fostered between various Catholic schools and that between these schools and others that kind of collaboration develops which the wellbeing of the whole human family demands.Footnote 54

It may be that the Presentation Sisters in Carlow believed they were fulfilling ‘the spirit of co-operation’ by leasing their old school building to the vocational authorities. However, the renting of additional classroom space to a competing post-primary school was not entirely what Colley had envisioned when he announced his co-operation scheme which was intended to be implemented by means of both ‘sharing’ and ‘pooling’ resources.

In order to aid local discussions and to clarify his vision for how co-operation could be achieved, the minister included in his letter of 4 January 1966 a number of suggestions for consideration. Among the main points for discussion were whether all classrooms in the area were being fully utilised and if ad hoc arrangements could be made to provide additional accommodation where needed. The minister also queried if it would be possible to allow for the interchange of teachers and /or pupils between different schools in order to better utilise teaching resources and provide a broader, more comprehensive curriculum to students. He also suggested the possibility of introducing new subjects — not already taught — and employing suitably qualified teachers to provide instruction in their respective specialised subjects; these teachers would not be employed by any one school but would serve all schools in the locality. Finally, where instruction in a particular subject could not be justified because of low pupil uptake in an individual school, the minister invited school authorities to consider forming mixed classes with pupils from both the secondary and vocational schools. This, he believed, would make the teaching of all subjects on the curriculum viable and feasible.Footnote 55

In addition to the programme outlined above, Colley also appointed Pádraig Ó Nualláin, a member of the Department of Education's inspectorate, to oversee negotiations and to act as a mediator between the school authorities and the department.Footnote 56 The first meeting to take place with Ó Nualláin was held in Carlow on Wednesday, 9 March 1966, approximately two months after the first meeting between the school authorities in the town. The annalist from the Presentation Convent, Carlow, recorded:

At 7:00pm we met again in the Parochial House. The main thing that emerged from the meeting was that staff in each school was working full-time and that with accommodation as it was in the technical school, their problem of providing classes for apprentices was great indeed and the need to expedite operations on the plans for the new school was urgent in the extreme.Footnote 57

It would seem that Ó Nualláin's appointment to preside over the meetings in Carlow did little to expedite negotiations between the secondary and vocational authorities. The Presentation Sisters appeared to be of the opinion that the main problem was lack of accommodation in the vocational school. It is possible that the Presentation Sisters in Carlow believed that if a new vocational school was built then the prospect of having to implement the department's co-operation scheme would recede.

The apparent lack of action to implement any concrete co-operation measures was evident not just in Carlow. A similar meeting between the department official, Mr Coyle, and the teaching staff of the post-primary schools in Hospital, County Limerick, was held in the Presentation Convent in the village in March 1968.Footnote 58 In attendance at the meeting were Mr Rushe, Vocational Education Committee (V.E.C.) C.E.O., and a representative of the Association of Secondary Teachers of Ireland (A.S.T.I.) and the Vocational Teachers Association. Two Presentation Sisters, Reverend Mother M. Loreto and Mother M. Immanuel, representative of the Conference of Catholic Secondary Schools (C.C.S.S.), travelled from Thurles, County Tipperary, to attend the negotiations. The annalist of the Presentation Convent, Hospital noted that ‘The object of the meeting was to encourage and foster closer co-operation between the three post-primary schools and to share equipment and teaching facilities. No definite programme of integration was drawn up.’Footnote 59

In both Carlow and Hospital, these initial meetings proved fruitless. The focus of attention in Carlow was not on co-operation but on the need for a larger vocational school in the town. In Hospital, no definite plans regarding co-operation were agreed upon. It would appear that secondary school authorities in general were slow to accept co-operation as a necessary step towards improving the existing post-primary education system. As suggested by Randles, during many of these meetings, ‘conversation tended to be guarded and rather vague … managers and principals … were reluctant to come to firm decisions … discussions became protracted and, in many cases, aimless’.Footnote 60 But while school authorities were attempting to evade any genuine commitment to collaboration, the Department of Education was utilising its resources to make the prospects of co-operation a more tenable option.

IV

In 1967, the move towards implementing co-operation at post-primary level became ever more pressing following the publication of a series of reports carried out by the Department of Education. As early as October 1965, during the course of a Fianna Fáil meeting in County Limerick, Minster Colley announced his intention to establish a ‘Development Branch’ in his department to ‘examine and advise on present and future post-primary accommodation needs’.Footnote 61 Between 1965 and 1967, the Development Branch compiled a study of existing secondary school facilities and accommodation. The survey was carried out on a county-by-county basis, taking consideration of the size, location and distribution of each secondary and vocational school in the country. The Development Branch was required by the minister to formulate a plan whereby a comprehensive type education could be achieved through the existing structures of the post-primary school system. By April 1967, the Development Branch had completed the survey, whose results were expected to alter considerably the provision of post-primary education.

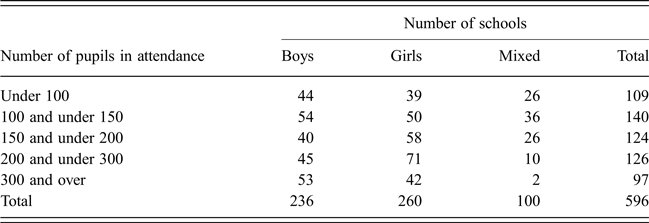

Henceforth, second-level education would be provided in one of two types of school centres: a major or senior centre which provided post-primary education to leaving certificate level and a junior centre which catered for pupils to intermediate certificate only.Footnote 62 In order to qualify as a senior centre, the minimum annual intake of pupils into the junior cycle had to range between 80 and 100.Footnote 63 According to the Department of Education, ‘a major educational centre in a County would … have available, as a minimum, accommodation for 320 to 400 pupils’.Footnote 64 In 1967, there were approximately 596 secondary schools in operation in Ireland providing second-level education to 118,807 pupils.Footnote 65

As can be seen from table 1, during the school year 1967–8, only ninety-seven secondary schools had more than 300 pupils in attendance. The remaining 499 schools had 299 pupils or fewer, thus not qualifying as senior centres under the Development Branch's requirements. According to the Development Branch, all schools which failed to qualify as a senior centre would be accorded junior centre status. A junior centre, as outlined by the Department of Education, ‘would be one which would have a potential of about fifty [pupils] and would provide more post-primary education to the intermediate certificate only’.Footnote 66 The Development Branch expected that ‘the average-sized County should have three or four major centres, depending on the school population.’Footnote 67 In County Limerick for example, Limerick city, Newcastle West, Abbeyfeale, Hospital and Kilfnane-Kilmallock were selected by the Development Branch as major centres.Footnote 68 A further fourteen locations throughout the county, including Adare, Castleconnell and Cappamore, were listed as junior centres.Footnote 69 In relation to junior centres, Seán O'Connor, assistant secretary of the Department of Education, stated that:

Many of the schools were small, and while the raising of the school-leaving age and the provision of transport would increase enrolments, it did not seem possible in many cases to bring all the existing schools up to a viable size. In all such centres where there were two or more schools the aim should be common entry, providing for the maximum inter-school co-operation.Footnote 70

As such, under the scheme proposed by the Development Branch, in areas where two or more schools provided second-level education but did not qualify as major centres in their own right, senior status could be achieved through the process of co-operation.

Table 1: Classification of schools according to number of pupils in attendance at the beginning of the school year, 1967–8

Source: D.E., Annual report, 1967–8.

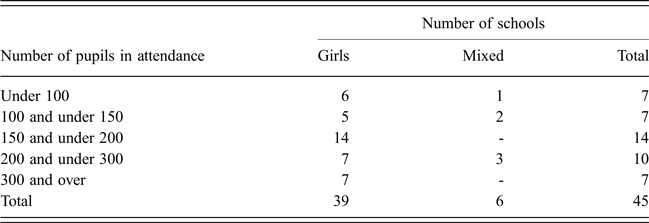

As can been seen from table 2, by the school year 1967–8, the Presentation Sisters were providing post-primary education in approximately forty-five recognised secondary schools. They had just seven schools with 300 pupils or more in attendance, located in Kilkenny city, Cork city, Tuam, Mountmellick, Drogheda, Limerick city and Thurles.Footnote 71 The requirements proposed by the Development Branch suggested that these Presentation secondary schools would be granted senior centre status under their own merit. However, the future of the remaining thirty-eight Presentation schools that did not qualify as senior centres was somewhat less clear.

Table 2: Classification of recognised Presentation secondary schools, according to numbers of pupils in attendance at the beginning of the school year, 1967–8

Source: D.E., Data on individual secondary schools, 1967–8.

The perceived threat to existing secondary and vocational schools caused by the findings of the survey report carried out by the Development Branch became a major concern for many secondary school authorities. The possibility of being demoted to a junior centre or worse, forced to close, was worrying for many, not least the Presentation Sisters in Ballingarry, in rural south County Tipperary. In 1967–8, the Presentation secondary school in Ballingarry was providing post-primary education to 223 pupils — thirty-one boys and 192 girls.Footnote 72 Prior to the publication of the results of the county surveys on post-primary education, the superior of the Presentation Convent, Ballingarry, Sister Madeleine, wrote to Tarlach Ó Raifeartaigh, secretary of the Department of Education, outlining her concerns regarding the future of the school:

Apparently there are to be three or four major centres in each County. As our location is removed from any large town we could hardly expect to be one of these. Hence we conclude we shall rank as a Junior Centre only, eligible for pupils up to intermediate certificate. If this happens our very existence is threatened, as we could not live here without our boarding school. But no parents would send us boarders if they would have to transfer them to another school after inter cert.Footnote 73

While the survey report for County Tipperary had not yet been released by the Development Branch, the reverend mother was under no illusions as to the danger which the findings of such a report would reveal about the circumstances surrounding the secondary school in Ballingarry. The report for other counties, including Kilkenny, which borders Ballingarry, had at the time of the Sister Madeleine's communication to the department, been publicised. The reverend mother was, thus, acutely aware of the demotion of other similar rural, convent-run secondary schools to junior centres. In light of this threat, Sister Madeleine outlined to Ó Raifeartaigh reasons for retaining a major secondary school centre in Ballingarry:

Last September at the request of the parish priest, and with the blessing of the Archbishop, we started co-education … the parents of the parish were very pleased as it opened our secondary school to many boys whose parents could not afford to send them away to college … We are prepared to enrol more boys in September as well as increasing our intake of day-girls and boarders.Footnote 74

According to her, the sisters in Ballingarry would admit additional pupils, both boys and girls, to their school from September 1967 onwards as they had built ‘within the last year, a very fine assembly hall, a block of classrooms and modern cloakrooms and toilet accommodation’. This was the second extension carried out by the Presentation Sisters within a six-year period, the earlier construction comprising a block of classrooms and toilet facilities. The reverend mother indicated that the extensions were ‘built at the expense of the community and we did not ask for any grant from the Department of Education’.Footnote 75 This statement was undoubtedly an attempt by the reverend mother to highlight the self-sufficiency and independence of the Presentation Sisters in Ballingarry.

In a final effort to gain support from Ó Raifeartaigh, Sister Madeleine summarised her reasons for securing the future of the Presentation secondary school in Ballingarry: low fees, the existing extensions, an expanded curriculum (‘We plan to start science in September to help the boys’ future’), modern teaching methods in French, and a range of extracurricular activities (‘We employ teachers for speech-training, music, gymnastics and games, Irish and modern dancing and ballet’). Sister Madeleine pledged that her community and colleagues were ‘prepared to do anything the Department wishes to improve our curriculum’. Moreover, she indicated that the sisters were not opposed to some level of co-operation, if it would guarantee that the school would not be demoted to a junior centre. However, the technical school in the parish was ‘unfortunately … one mile from our school, otherwise the two could combine to provide a comprehensive education for our parish and surroundings’. Faced with the threat of closure, the reverend mother claimed willingness to co-operate with the department and suggested that ‘perhaps the department could think out some plan’ which would enable co-operation in Ballingarry.Footnote 76 There is no doubt from the above correspondence that the survey carried out by the Development Branch caused major concerns for school authorities. Sister Madeleine presented Ó Raifeartaigh with a strong case in relation to the viability of her school. However, it remained to be seen whether she had done enough to secure the future of second-level education in the village.

Within a week, the survey results for County Tipperary were made known by the Development Branch, concluding that there was room for only one post-primary school in Ballingarry.Footnote 77 Ó Raifeartaigh wrote to Sister Madeleine, noting that, ‘the annual potential for the district is only fifty [pupils] and normally this is sufficient to sustain only a junior level school’. However, he acknowledged that the Presentation school in Ballingarry was ‘a boarding school and this will have to be taken into account when the question of determining senior cycle centres comes to be settled’. Ó Raifeartaigh informed her that ‘the County report will be discussed at a meeting in Thurles shortly, to which representatives of your school will be invited’ and assured her that ‘no decision will be made without full discussion with you beforehand and that we will deal with your situation as sympathetically as possible’.Footnote 78

This correspondence reveals that the Development Branch's recommendations for post-primary provision were not definite. Secondary schools would not be demoted to junior centres based on pupil numbers alone. Consideration would also have to be given to the location and whether or not a school offered boarding facilities to their pupils. While it is clear from that the secretary for the Department of Education wished to reassure the Presentation Sisters that there was no immediate threat to their school, there can be no doubt that the community in Ballingarry entered a period of uncertainty regarding their future in the provision of post-primary education.

From April 1967 onwards, the preliminary reports prepared by the Development Branch of the Department of Education on post-primary facilities in Ireland were made public and county-level meetings were organised by the department to give ‘interested parties’ an opportunity to discuss the findings. On 26 and 27 April 1967, a meeting to discuss post-primary education facilities in County Cork took place in the Lecture Theatre, Crawford Municipal School of Art, Emmet Place.Footnote 79 A similar meeting to discuss post-primary facilities in County Limerick was held in the School of Commerce, Mulgrave Street, Limerick on Tuesday, 9 May 1967. A meeting was also scheduled to take place in the Confraternity Hall, Thurles, County Tipperary on Thursday, 11 May 1967.Footnote 80 According to the annals of the Presentation Convent, Ballingarry:

The Department of Education has planned to amalgamate schools … this will require great organisation and for that reason the existing schools must know exactly where they stand and foresee their best chances of survival. Meetings will be held in Thurles where all ideas will be pooled and hints given where they are needed.Footnote 81

A further meeting was held in Thurles in November 1967:

A very large County meeting was held in the Confraternity Hall, Thurles at which Department of Education officials presided and all post-primary schools in County Tipperary were represented. Accommodation available and all school facilities provided had to be furnished by the school authorities. Transport to and from school was discussed in detail.Footnote 82

The County Kerry meeting was organised for Friday, 12 May 1967 in the Central Technical School in Tralee.Footnote 83 The meeting for County Galway took place in the Presentation Convent, Newcastle Road, Galway on Thursday, 18 May 1967.Footnote 84

While the Department of Education deliberately and actively involved the authorities of secondary schools in the development of post-primary school policy, there were those who felt that the county meetings provided little opportunity to express genuine opinion. According to Michael Sheedy, president of the A.S.T.I.:

The Development Branch of the Department of Education chose to give the shortest notice of date of vital rationalisation meetings to my association, the Association of Secondary Teachers in Ireland. A bare two weeks notice and a lack of full agenda in some cases, for meetings in Kilrush, Tipperary, Roscrea, cannot be regarded as helpful. The shorter notice still (May 13) regarding meetings in Castletownbere, Ballyvourney, Dunmanway, Clonakilty, Passage West and Youghal to be held on May 19, 20, 21 and 22 forces me to concern for my members in these areas and forces me to raise a question. Is the Department of Education deliberately trying to rush these meetings in order to forestall full consideration of the plans by management and teachers? Footnote 85

Furthermore, Sheedy believed there were many problems which needed to be discussed:

Will rural areas and small country towns and villages find their young schoolgoers forced to travel to large towns and cities for all or part of their schooling? If so, will the future depopulation of the countryside have begun? Are long bus journeys, morning and evening, to become a feature of life for many schoolgoers? Are schools which have served local communities over many years to be closed? Will the most highly qualified teachers find that their talents are not extended in the junior cycle schools and gravitate to the senior cycle schools? Are teachers who have planted roots in the areas where they work and when have entered into financial and housing commitments to these areas to be … disturbed and that without compensation?Footnote 86

Although Sheedy presented a number of problems that would undeniably arise should Colley's co-operation scheme be implemented on a national scale, it seems that the concerns of individual school authorities lay elsewhere. Following the publication of the Development Branch reports, the biggest threat to religious-run schools was the possible closure of small secondary schools, no longer deemed viable according to Department of Education criteria. Seán O'Connor, assistant secretary of the Department of Education, stipulated in May 1967 at a conference on post-primary education in Limerick city that:

The minimum requirement would be a two-form entry, about fifty pupils, making an enrolment of 150 pupils in six classes in the junior cycle. Areas that could not provide an entry of this size would be best served by transport to another centre … Existing schools that were not viable by these standards should be closed.Footnote 87

With the very existence of individual secondary schools threatened, many school authorities were less concerned with the distance a pupil was expected to travel to avail of second-level education or teachers’ grievances.

V

From April 1967 onwards, a number of post-primary schools received information from the Department of Education regarding the viability of their institutions. One example was from Fethard, County Tipperary, where there were two separate secondary schools. The Presentation Sisters had first come to Fethard in 1862.Footnote 88 In 1916, they established a secondary school in the town and by 1940 it had been awarded state recognition.Footnote 89 By the school year 1966–7, there were ninety-four girls in attendance.Footnote 90 The Patrician Brothers arrived in Fethard in 1873. An intermediate school for boys was established upon their arrival to the town but closed due to insufficient numbers in 1890. Until the 1940s, there were no secondary school facilities for boys in the town. However, in 1941, at the request of Most Reverend Doctor Harty, archbishop of Cashel, the Patrician Brothers once again ventured into the field of post-primary education.Footnote 91 They were awarded state recognition for their secondary school during the school year 1941–2.Footnote 92 By 1966–7, the Patrician Brothers were providing second-level education to approximately eighty boys.Footnote 93 In 1967, following the publication of the Development Branch survey reports on post-primary education, the managers of both the Presentation and Patrician secondary schools in Fethard were informed by the Department of Education that there ‘is room for only one school’ in the town.Footnote 94 They now faced having to accept co-operation or risk closure of one or the other of their schools. Following negotiations, the Presentation Sisters and the Patrician Brothers provisionally agreed to implement co-operation. On 18 June 1967, the authorities of both secondary schools informed the Department of Education:

Arising out of the preliminary report on secondary schools in the south-eastern corner of County Tipperary, and to the fact that there is room for only one school in Fethard; we wish to let you know, as promised, of our proposals for close co-operation between the two existing schools.Footnote 95

According to the memorandum, an agreement had been reached between the mother superior of the Presentation Convent, Fethard and the brother superior of the Patrician Monastery, Fethard. Under the terms of the agreement, the superiors of the convent and monastery would collectively act as a committee of management. The schools would operate under the governance of joint head-teachers with a Presentation sister acting as headmistress and a Patrician brother as headmaster. It was stipulated that common enrolment would be applied as of the October list 1967. Co-education at senior cycle level was to be implemented in the core subjects of Irish, English and history, while at intermediate level instruction in French, art, music, shorthand and type-writing were to be conducted as mixed classes. The religious superiors jointly agreed to adhere to the particulars of the co-operation scheme for an initial period of five years, ‘after which time it will be subject to review’.Footnote 96

This action in Fethard suggests that co-operation was only achieved following the Department of Education's communication stating that there was only room for one secondary school in the town and region. While the Department of Education organised public meetings to help formulate localised policies in relation to co-operation, it would seem that some school authorities, such as those in Carlow and Hospital, did not feel under any duress to co-operate. As a result, negotiations between the Department of Education's officials and school managers often proved futile. A number of secondary schools, particularly those owned and managed by religious congregations, were undoubtedly apprehensive about the co-operation scheme as it was likely perceived as a threat to the traditional autonomy enjoyed by independent teaching orders. The implementation of co-operation would require not only the sharing of facilities and resources but also the sharing of responsibility and decision-making, a practice not previously associated with the Irish secondary school system. Only following an official communication from the Department of Education regarding the viability of individual secondary schools were the authorities prepared to enter into an agreement in relation to co-operation. A similar situation occurred in Hospital, County Limerick where the possibility of introducing co-operation was first suggested in March 1968.Footnote 97 However, by September 1969, no agreement had been reached between the post-primary school authorities in the town. The annals of the Presentation Convent, Hospital noted that: ‘New arrangements for the rationalisation of post-primary education has been mooted; the status of our secondary school has not yet been determined; we have been urged to co-operate with the other post-primary schools in the town.’Footnote 98 Clearly, the school managers in Hospital were waiting for confirmation regarding the status of their school and, like Fethard, the school authorities in Hospital were unwilling to negotiate a policy of co-operation until the Department of Education gave them no other alternative but to comply with the minister's scheme. Despite the apparent initial reluctance of the school authorities in Hospital, co-operation was finally introduced between the Presentation and De La Salle secondary schools in the village in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

By degree, co-operation was implemented throughout the country where two or more post-primary schools existed in relatively close proximity to one another. Randles indicates that co-operation was most evident in the interchange of teachers as opposed to pupils. This system of collaboration caused the least disruption to the students’ daily routine while enabling the schools to provide a comprehensive curriculum.Footnote 99 Sister Martina, a teacher in a Presentation secondary school in County Galway between 1967 and 1976, recalls that ‘I had a class down in the tech, what we used to call the tech[nical school] then, and I was teaching religion down there and a teacher [from the technical school] was up here teaching science.’Footnote 100 However, the interchange of staff was not without its complications, particularly in relation to school timetables. Sister Imelda, who had been appointed principal of a Presentation secondary school in rural County Limerick shortly after Colley's co-operation scheme announcement, recalls:

Now what became a real nightmare was the timetable because you had to try and work out the timetable to accommodate all this movement and to try and create the least possible movement for everybody. Now everybody I think had a bad day, a day where they [the teachers] had to go up and down a few times but as long as it wasn't every day, they accepted it as reality.Footnote 101

Similarly, Sister Grace, who was teaching in a Presentation secondary school in County Kerry, remembers the difficulty of trying to manage the school timetable after co-operation had been introduced in her school. She noted that:

It was difficult from the point of view that the convent secondary school … was at one end of the village and the vocational school was way down about three-quarters of a mile with the result I found myself flying down the village … You'd find yourself maybe timetabled from nine to twenty-to-ten in the convent secondary school and timetabled for quarter-to-[ten] down below in the vocational school … a half a mile or maybe three-quarters at the other end of the village.Footnote 102

While the main form of co-operation was an exchange of staff, that is not to say that some schools did not opt for the alternative interchange of pupils. Sister Genevieve, who was teaching in County Waterford, explains that:

There was an arrangement between the vocational school which was very near and the convent school where the boys went to the woodwork room in the vocational school and the vocational students came up to the convent … I can't remember for what now, maybe it was French … There was an exchange system and as the schools were quite close it was very good.Footnote 103

Sister Imelda likewise recalls that for a brief period, it was the pupils who travelled between the Presentation school, where she was principal, and the corresponding boys school in the town: ‘the boys had been coming down to the convent … for whatever subject they might want and the girls went up to the Brothers for … something in the sciences.’Footnote 104 Similar to the timetable issues associated with the interchange of staff, the movement of pupils between two post-primary schools also had its limitations, as Sister Genevieve explains: ‘We all complained madly because we lost five minutes at the beginning of class waiting for the students to come back from wherever they were, whether you were in the vocational or the secondary.’Footnote 105

Of course, not all existing secondary schools were expected to engage in co-operation. Many of the larger post-primary schools continued to provide second-level education as completely autonomous institutions. Presentation secondary schools in locations such as Thurles, County Tipperary, Kilkenny town and Tuam, County Galway where pupil numbers had never been sparse, entered a new decade practically unaltered by the reforms of the late 1960s.

VI

In theory, Colley's plan to rationalise resources and implement co-operation between existing second-level institutions was practical. By the late 1950s, the Irish post-primary school system was in need of major reform. The vast majority of secondary schools were small, catering for fewer than 300 pupils which in turn impacted the range of subjects offered and the quality of education provided. Pooling resources and sharing expertise was a practical solution and a relatively cheap way of extending educational provisions without the need for major financial investment from the government. However, there were shortcomings within Colley's scheme, not least around how co-operation would work in practice. Although departmental officials were appointed to oversee negotiations, most school authorities were expected to develop their own strategies and approaches to co-operation. In some localities, this resulted in the interchange of staff, while in others students were expected to move between schools for various subjects. The movement of students and staff between schools undoubtedly caused further complications for school authorities including loss of teaching time and timetabling issues. These problems were neither predicted nor addressed by the department, and school authorities were largely left to their own devices to devise workable arrangements with the least disruption to their students and staff.

Due to the practical difficulties associated with accepting Colley's proposals, it is not surprising that some school authorities were reluctant to enter into co-operation agreements. Furthermore, it should be noted that many religious-run secondary schools were founded voluntarily, built and maintained by funds from within their own communities with little or no support from the government. There might, thus, be some reluctance to enter into a departmental scheme which ultimately threatened traditions of independence that, in some cases, had existed for more than a century. It is possible that many religious orders were also wary of the potential loss of autonomy if they entered into co-operation agreements with other schools. Given the scale of Catholic religious orders’ involvement in the provision and delivery of education in the 1960s, it is unlikely that the Presentation Sisters were alone in their initial reluctance to implement co-operation or rationalise resources. As evidenced above, schools such as the Patrician Brothers in Fethard and the V.E.C. in Carlow also showed some hesitation in their willingness to co-operate. Clearly, there is a need for further case studies of this kind to provide a more complete understanding of how co-operation was received by school authorities and how, in turn, rationalisation was implemented in practice.

Colley's initiative was also, perhaps, a little premature. Although a number of school authorities were initially reluctant to rationalise and enter into co-operation agreements, in time full-scale amalgamation of existing resources and facilities became inevitable. With the introduction of subsequent reforming measures, most notably the Free Education Scheme in 1967 and the development of community schools from the early 1970s, increasing numbers of second-level school authorities came under pressure to provide a comprehensive curriculum to their pupils. Colley's co-operation scheme and plans for rationalisation set in motion a period of major change in the Irish post-primary school sector. Regrettably, for Colley, much of this change could only be fully realised when other reforming measures in the sector were introduced. Colley's term as minister for education was also short-lived and he was succeeded to the office by Donagh O'Malley in 1966. At the time of Colley's departure, the Development Branch had not finalised their survey on post-primary facilities and accommodation, and so he was not involved in the subsequent rollout of their findings. It is also possible that O'Malley's free education announcement in September 1966 overshadowed much of the work which had been started under Colley's direction.

The interactions between departmental officials and individual school authorities provide a unique insight into Colley's plans for co-operation and rationalisation in the Irish post-primary school sector. Although the broader political narrative of these initiatives has been accorded some significance in histories of the Irish education system, few have addressed the role played by individual school authorities, and even less have considered the place of congregations of teaching sisters within the discourse surrounding the reform period of the 1960s. By the mid twentieth century, the Presentation Sisters were the second largest cohort of female religious involved in the provision and delivery on girls’ second-level education and yet little is known about the role they played in Irish education or how they managed and organised their schools. The same can be said for the many other religious orders, both male and female, who voluntarily established and operated the majority of secondary schools in Ireland at this time. Although this article has attempted to fill a void in traditional histories of the reform era, there remains a need for further exploration. Historians need to go beyond the official narrative and consider the many strands and complexities of what characterised the Irish education system during the long 1960s.