Introduction

At the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, 202 Rohingya refugees boarded a wooden boat and departed from temporary shelters in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh in search of better livelihoods free from violence and persecution. After several months at sea, the boat finally reached Malaysia’s popular tourist island of Langkawi in April 2020, shortly after the Covid-19 border closure. Around the same time, a Rohingya community leader who had been residing in Malaysia for almost three decades called for better living conditions and access to state services for the Rohingya population. His remark was exaggerated by fake news, which swiftly circulated ‘reports’ that the leader demanded equal citizenship rights and hence was ungrateful to the host community in Malaysia.Footnote 1 It subsequently triggered a widespread feeling of resentment towards the Rohingya community, urging the Rohingya to be eradicated and returned to Bangladesh and Myanmar. Such demands marked a stark contrast to Malaysia’s relatively tolerant attitude towards the Rohingya settlement since the early 1980s.Footnote 2 Yet the online remarks did not only mobilise hateful rhetoric against the refugees but also galvanised into radically challenging refugee protection norms, civil society solidarity, humanitarian and cosmopolitan principles, and the United Nations (UN) agencies. This paved a way for the locals to re-envisage a Malaysian society in reaction to the perceived ‘undeserving’ position of Rohingya refugees during the global health crisis.

The above anecdote captures how intense emotions such as resentment prompt a collective contestation of international norms that extends to attacking actors, international institutions, and the wider normative order which reinforce the foundation of refugee protection. Norms research in International Relations (IR) has produced a vibrant programme which examines norm contestation that targets norm robustness and legitimacy.Footnote 3 However, such literature only captures a partial picture of norm contestation as it mainly studies the impact of contestation on a particular norm. It overlooks the form and effect of radical contestation on the wider actors, institutions, and normative order that underpin the norm in question. Furthermore, existing norms scholarship largely ignores the role of emotions in driving contestatory practices. As Rohingya refugees themselves assert, the Covid-19 period saw ‘unprecedented negative sentiments’ towards their community.Footnote 4 These shortcomings pose important blind spots in norms research and create an impetus for scholars to broaden the intellectual horizon to interrogate radical contestation and take emotions seriously in studying international norms and politics.

To offer a more complete account of norm contestation, this article charts new territory in norms research by directing our attention to radical contestation. Taking inspiration from the study of populism and emotions from sociology, law, psychology, and IR, I argue that radical contestation is a disruptive challenge to norms, which seeks an overhaul and reorganisation of societal and normative order.Footnote 5 This form of contestation embodies intractable differencesFootnote 6 and represents a critique of an existing order as opposed to a corrective to improve the current order.Footnote 7 Radical contestation can further be distinguished by (1) the extensive scope of contestation, which not only attacks a specific norm but also a wider normative order, including broader principles, institutions, and actors sympathetic to the norm in question; and (2) the high intensity of emotions in animating the challenge to both norms and normative order. Viewed in this light, radical contestation is extensive and emotionally driven and aims at undermining the legitimacy of norms and the normative order altogether. In encapsulating these two features, this article enriches norms research by advancing the study of radical contestation, which has not gained sufficient scholarly attention.Footnote 8

Furthermore, while the aforementioned two features can explain what radical contestation is, they alone do not elucidate how radical contestation plays out and to what effect. Thus, to bring together the features of radical contestation and explicate the process and effect of radical contestation, I advance a new framework, called ‘emotional backlash’. My emotional backlash framework integrates the scholarships on emotions and backlash movements and conceptualises radical contestation into three analytical components: construction, mobilisation, and outcome. This framework is then applied to scrutinise the emotional backlash against the Rohingya refugees during Covid-19. In doing so, this article contributes to norms research and IR by deepening the knowledge of radical normative change that is not readily captured in the existing norm contestation approaches.

The argument unfolds over six sections . The first section conceptualises radical contestation as distinguished from other norm contestation approaches. The second section presents the emotional backlash framework to conceptually explain the construction, mobilisation and outcome of radical contestation. The third section outlines research methods before analysing Malaysia’s treatment of refugees and the emotional backlash against Rohingya refugees in the fourth and fifth sections. The final section concludes by suggesting future research agendas and the implication of such emotional backlash for the international refugee regime.

The ‘radical’ in norm contestation

Radical contestation is understood as a disruptive challenge that seeks to overhaul and reorganise an existing normative order. It represents a critique to an existing order where differences and disagreements are intractable, as opposed to a corrective that rectifies an order.Footnote 9 Using insights from the study of populist and far-right movements and emotions from sociology, law, psychology, and IR, I develop the two key features of radical contestation: (1) the extensive scope of contestation that attacks a specific norm and a wider normative order, including broader principles, institutions, and actors related to the norm in question; and (2) the high intensity of emotions in driving the assault on both norms and normative order. In doing so, I demonstrate how radical contestation is distinguished from other types of norm contestation that mainly target the robustness and legitimacy of a particular norm, thus addressing the limitations of the existing norms scholarship.

The first feature of radical contestation is defined by its scope. Radical contestation has an extensive scope of attacking both norms and a larger normative order, including wider principles, institutions, and actors sympathetic to norms. As Madsen et al. find in the study of international courts, radical challenge is different from mere opposition to courts in the sense that it does not solely target the specific content of a law or court ruling.Footnote 10 Instead, radical contestation pursues the wider goal of dismantling the overall authority of international tribunals. Similarly, Philip Alston examines radical populist movements during the Trump administration and asserts that such movements are ‘fundamentally different from much of what has gone before’.Footnote 11 Radical populist movements, as Alston observes, do not simply target human rights and democratic norms but spill over to attack civil society space, solidarity for ethnic minorities, international rule of law, and international institutions. In this sense, the extensive attack means that radical movements oppose human rights and democratic norms and expand to shut down the legitimacy of the proponents of such norms, including the multilateral institutions and international liberal order which uphold human rights and democracy.Footnote 12 Further, populist movements ubiquitously display reactionary tendencies, seeking to destroy an existing normative status quo and propounding a nostalgic longing for the return of a glorious past in order to rediscover the traditional values and state-oriented order against the globalised liberal order.Footnote 13 As such, radical contestation is a fundamental challenge to norms and normative order, rendering it a disruptive kind of contestation.

Second, radical contestation involves a high intensity of emotions. Such understanding follows Van Rythoven’s argument that radical contestation is ‘a distinctively emotional phenomenon’ due to ‘an irreducible embodied intensity’.Footnote 14 It is differentiated from banal disagreements, disputes, or opposition because the emotional intensity cannot be reduced to plain speech acts. It signals situations that transgress from mundane debates to more acute moments of hostility, marking the limit of tolerance among radical contesters towards a particular issue or claim. The hostility entails profound emotional and political reactions, including ‘anger, shame, or disgust [which] are best conceived of as the body’s klaxon alarm alerting audiences to claims which appear especially dubious and grotesque’.Footnote 15 The highly emotional and hostile opposition among the contesters also makes the differences among them intracFootnote table 16 and can also be captured as ‘a politics of disgust’, which ‘is the most intense kind of politics, and the combustible feelings tied to it are sources of potential violence’.Footnote 17 For instance, the early advances of marriage equality in the US in the 1990s sparked a feeling of disgust among religious community and legislatures. They responded by shutting down the recognition of gay and lesbian marriage through the legal redefinition of marriage specifically as a union of a man and woman and requiring officials whose spouse supported the cause to recuse themselves from decision-making.Footnote 18 Connecting to the first feature of radical contestation, the high emotional intensity drove the attack not only on the marriage equality norm but also on the larger principle of good governance, because officials’ recusal excluded the gay and lesbian community from participatory and democratic debates.

These two features of radical contestation have not been sufficiently studied in norms research in IR. Norms scholars rightly offer insights into the study of norm erosion through validity or reactive contestation.Footnote 19 But radical contestation, with its first feature, does not only aim at norm erosion. To elaborate, in comparison to ‘norm antipreneurs’ who defend the entrenched normative status quo by resisting normative change,Footnote 20 radical contesters challenge the normative status quo by undermining partially or fully established norms. Moreover, radical contesters go beyond norm antipreneurs with their larger scope of attacking not only a specific norm but also a broader normative order, institutions, and actors that sympathise with the norm in question. This makes radical contestation unique. It is a dangerous form of contestation that can overturn the existing system (see further below). In Wolff and Zimmermann’s critique of the existing norms scholarship, radical contestation with the view of seeking fundamental change has not received sufficient attention in norms research in IR.Footnote 21

In addition, the norm contestation literature has scarcely engaged with emotions. Scholars who adopt the lens of contestation and emotions have largely done so by examining the contestation of emotions in resolving which emotions actors should feel as socially appropriate.Footnote 22 This body of literature overlooks the contestation of norms as influenced by emotions. This is an important oversight, as Koschut rightly points out the emotional underpinning of norm contestation: actors who disagree with norms can be ‘shamed’ (a negative social feeling) into norm compliance.Footnote 23 Finnemore and Sikkink further contend that ‘to pretend that affect and empathy do not exist is to miss fundamental dynamics of political life’, and that the analysis of emotions can improve our understanding of international norms dynamics.Footnote 24 Moreover, despite the recent effort to rectify such shortcomings by Alter and Zürn, who understand emotions as a ‘frequent companion’ to backlash movements, their study remains under-specified in explicating specifically the role and influence of emotions in radical contestation.Footnote 25 Thus, existing studies have not fully addressed the two features of radical contestation. Such knowledge gaps warrant a new study that can better grasp the dynamics of radical contestation, presented in the following section.

Emotional backlash

While the previous section discusses the form of radical contestation which involves the extensive contestation scope and high emotional intensity, this section conceptualises the process and effect of radical contestation. To do so, it presents the new ‘emotional backlash’ framework, which advances the three analytical components of radical contestation: construction, mobilisation, and outcome. The emotional backlash enriches norms research by extending the analytical focus beyond mere norm contestation and allowing scholars to better comprehend fundamental challenges to international norms, institutions, and normative order.

My framework follows Hutchison and Bleiker’s assertion that it is more fruitful to move away from the traditional notions of causality and instead to focus on understanding the political influence of emotions.Footnote 26 This enables scholars to trace how emotions challenge or reinforce the boundaries of what is thinkable and unthinkable, and accepted and not, thus offering a fuller picture of radical contestation that is emotionally driven. My framework therefore does not argue for the causality between different components. Rather, it conceptualises the constitution of a particular form of radical politics: emotional backlash politics. To do so, I bring disjointed academic discussions on emotions and backlash movements from law, sociology, psychology, and IR into conversation with empirical observations. Such dialogues synergise and fine-tune the existing theoretical knowledge on radical contestation, hence providing a valuable framework for scholars of norm contestation, emotions, and backlash politics.

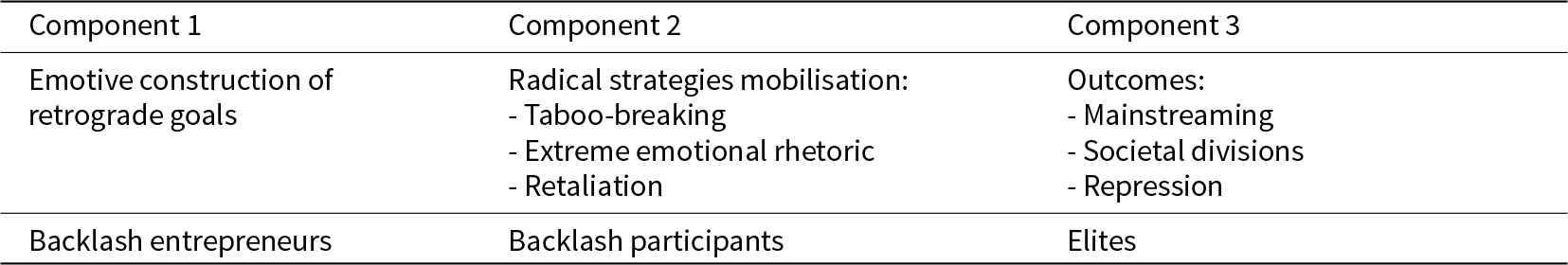

The emotional backlash framework has three components (see Table 1). Component 1 concerns the construction of retrograde goals by backlash entrepreneurs who cultivate emotions to create such goals. Component 2 deals with the mobilisation by backlash participants who deploy radical strategies to achieve backlash goals. Borrowing insights from the social movement literature, the first and second components of construction and mobilisation consider the supply and demand of protests.Footnote 27 The supply focuses on goal-setting, offering opportunities for sympathisers to join a movement, while the demand relates to a mobilisation potential and societal groups sympathetic to the cause. Although analytically separate, these two components acknowledge the possibility of critical mass mobilisation, where the supply and demand of radical contestation converge and become mutually reinforcing in reality. Lastly, Component 3 captures the outcome of emotional backlash from the ruling elite. The framework that I present does not intend to depict a linear picture of emotional backlash because movements, as with emotions, can rise and subside, especially if there is a supply of opportunities but no demand, and vice versa.Footnote 28 Importantly, in distinguishing the processes of backlash construction and mobilisation (Components 1 and 2) from outcome (Component 3), the framework is agnostic to the result, thus giving analytical value for scholars to scrutinise radical contestation regardless of success or failure.

Table 1. Emotional backlash framework.

Component 1: Emotive construction of retrograde goals

The first component shows the activities of backlash entrepreneurs who perform emotions to formulate a goal of backlash movement by (1) shaping interpretation of events and (2) consolidating moral conviction. Emotions are understood as ‘conscious manifestations of bodily feelings’ as well as a cognitive representation and appraisal of a concrete object, thus offering the social and collective dimensions of normative judgement.Footnote 29 Emotions are distinguished from affect, with the latter being non-conscious, non-cognitive, and amorphous phenomena which remain politically insignificant until they are represented through discourse.Footnote 30 This understanding of emotions is relevant to the creation of backlash goals, as backlash entrepreneurs cultivate collective emotions to create feeling rules that prescribe certain emotions as appropriate and others as inappropriate in responding to an issue or event.Footnote 31 This distinguishes emotional backlash from a more spontaneous affective response.

Backlash entrepreneurs initiate backlash by problematising their encounter with emotions-inducing objects. In doing so, they create an emotive representation of an object as dubious. Gustafsson and Hall assert that ‘we have no direct access to the internal emotional experiences of others, only the expressions, discourse, and practices representing those [emotional] states’.Footnote 32 The emotive representation of objects is therefore essential. It involves how emotions are ‘invoked in the abstract, hypothesized in conjectured scenarios, attributed to amorphous collectives, or elevated as politically meaningful’.Footnote 33 Representation can range from political speeches to visual images, making it possible for individual, embodied emotions to have collective dimensions.Footnote 34 This puts emotions into context and time and cultivates socially accepted norms.Footnote 35 Representation thus renders emotions intelligible, shaping social and political interpretation.

Understanding how emotions-inducing objects are represented is crucial to comprehend the construction of collective and emotive backlash goals. This is relevant to engagements on social media and in rallies because interactions have the potential to expose us to emotions-inducing stories and symbols.Footnote 36 Repetitions and reiterations in social interactions can also sustain particular emotions among actors who encounter the same object, generating shared emotions.Footnote 37 This is important for backlash entrepreneurs because the performance of emotions has the socially prescriptive and purposive function. It regulates an ‘appropriate’ emotion and behaviour and forms a normative hierarchy and beliefs.Footnote 38 To be concrete, backlash entrepreneurs problematise an object, for example a refugee, to induce a specific set of feeling rules such as anger as an ‘appropriate’ response to refugee arrivals while precluding other emotions such as empathy for refugees as inappropriate.

Backlash entrepreneurs cultivate resentment towards external objects to create a backlash target. Resentment is a common emotion in both left- and right-wing populism.Footnote 39 It comprises three broad groups of emotions: first, fear associated with alienation, insecurity, and feelings of powerlessness; second, anger over perceived injustice or unfair treatment; and third, hate as an intensification of resentment.Footnote 40 When extreme, resentment ‘becomes an obsessive, smoldering, simmering and festering sense of wounded self-esteem and a desire for revenge’.Footnote 41 It facilitates the dehumanisation of the backlash target, especially when coupled with the use of dehumanising rhetoric and slurs (discussed below). This undermines the human dignity of the target and normalises the view of the target as being inferior and even violence against them.Footnote 42 Thus, an actor can perform resentment in relation to another actor’s undeserving status, offence, indifference towards the former. Such emotional display entails the disapproval of a wrongdoer considered to be responsible for causing harm. This sense of built-in justice encompasses a moral assessment and makes resentment a ‘moral anger’Footnote 43 because an act of wrongdoing is considered to fall under the responsibility of the wrongdoer, who subsequently becomes a target of backlash.

Resenting a common target, backlash entrepreneurs can construct a movement goal. Backlash goals are retrograde, challenging the status quo in order to revert to prior social conditions where the values, norms, statuses, or privileges of backlash actors are reinstated vis-à-vis those of the ‘undeserving’ target.Footnote 44 The retrograde goal can refer to an actual past or an imagined past. This nostalgic vision in turn becomes normatively ‘appropriate’. As such, the retrograde goal does not only target a common enemy but also creates a belief that an alternative normative and societal order consistent with the morals of backlash actors is possible. Viewed in this light, to secure the nostalgic re-envisioning of a society, backlash movements attack the normative status quo associated with existing norms and backlash targets, paving the way for the reinstitution of norms affiliated with real or imagined prior conditions. As such, radical backlash entails both backward-looking and future-oriented elements to reorganise a normative and societal order based on nostalgia.Footnote 45

Emotions produce not only the retrograde goal of backlash but also a moral conviction or certainty in the interpretation of events. Mercer asserts that emotions strengthen beliefs, generating a ‘certainty beyond evidence [and] the stronger the feelings the more compelling the evidence for one’s beliefs’.Footnote 46 The clarity generated by emotions such as resentment resembles ‘a moral conviction [which] is grounded in core beliefs about fundamental right and wrong’.Footnote 47 Van Rythoven contends that it produces ‘an acute confidence among audiences that such practices were far beyond the realm of moral conduct’.Footnote 48 Consequently, a moral conviction is akin to facts about the world, forming a position that is considered universally valid. In this sense, emotions act as a heuristic tool which guide attention, perception, and judgement in cementing an interpretation of objects and the prioritisation of particular norms. It structures how actors feel, legitimise, and enact particular political views, norms, and attachments over the others.Footnote 49 Mapping onto emotional backlash, a moral conviction distinguishes what is ‘right’ (prior social conditions) and ‘wrong’ (status quo) and further offers motivational forces for group members to promote norms, deemed morally compatible with backlash movements, in order to challenge other norms and interpretations that clash with backlash objectives. The moral conviction is important. Without it, there would be no opportunities for mobilisation because backlash entrepreneurs and supporters would be uncertain whether their actions are worth the risks. A moral conviction, shaped by resentment, can motivate backlash participants to pursue the retrograde goal by deploying three radical strategies, discussed in Component 2.

Component 2: Radical strategies mobilisation

The second component of emotional backlash focuses on the activities of backlash participants and recognises the potential where the moral conviction reaches a critical mass and transforms into mobilisation. Backlash participants can deploy three radical strategies – taboo-breaking, extreme emotional rhetoric, retaliation – to achieve a retrograde goal. Through the three radical strategies, backlash movements seek to redress perceived grievances, crystallised through resentment, by replacing dominant norms associated with the status quo and to rediscover a normative order consistent with the retrograde goal.

First, backlash supporters deploy taboo-breaking. Taboo-breaking is supposed to violate socially acceptable lines in order to outright reject existing norms and principles.Footnote 50 It aims to transgress widely accepted boundaries with the goal of changing what are deemed ‘acceptable’ and ‘unacceptable’ discussions and behaviours. While taboo-breaking may be adopted by other actors, such as norm entrepreneurs who seek to invent new norms, such a practice also fits into backlash. This is because by rejecting dominant norms, backlash participants can advocate for the norms and principles that reinforce their retrograde goal. In doing so, they can undermine norms associated with the status quo and justify other norms associated with the return of the past as morally superior. For instance, the backlash against global gender equality norms in Iraq labels same sex relations as ‘sexual deviancy’. While the majority of states globally have decriminalised same-sex relations, this taboo-breaking is used to justify a legislation, imposing 10- to 15-year prison terms on LGBTQI+ persons with the objective of ‘protecting’ children from ‘moral depravity and homosexuality’ and rediscovering ‘the value structure of society’.Footnote 51 Taboo-breaking is therefore intended to be disruptive in uprooting existing norms and principles in order to secure the retrograde goal.

Taboo-breaking can go hand in hand with the second strategy of extreme emotional rhetoric. According to Koschut, emotions can be expressed through discourse with the use of emotion terms, emotional connotations, and emotion metaphors.Footnote 52 In using emotion terms, backlash participants convey their feelings with a direct reference to specific emotions, for example, by stating they are angry with incoming migrants. Backlash supporters can also use emotional connotations to indicate both an opinion and emotional attitude of the speaker.Footnote 53 This entails the use of loaded language to invoke emotions. For instance, one may express that migrants are too demanding and ungrateful to host communities. Such a statement does not only reveal the emotional attitude of the speaker but also generates additional feelings such as uneasiness, worries, and resentment towards backlash objects. Lastly, backlash supporters can utilise emotion metaphors to encode emotional performance and illustrate the emotional state of the speaker.Footnote 54 For example, backlash supporters may compare migrants to rabbits that multiply quickly or Covid-19 disease carriers. As asserted by Rousseau and Baele, extreme rhetoric such as dehumanised language and slurs are ‘performative utterances’ which are not mere descriptions of a reality but rather are truth claims which seek to shape reality.Footnote 55 Slurs sharpen the alleged differences between the backlash participants and the insulted target, ‘homogenizing the former as a positive entity and the latter as a negative one’.Footnote 56 Extreme emotional rhetoric thus serves the purpose of consolidating and mobilising backlash ingroups while destabilising backlash targets.

The third radical strategy is retaliation. Retaliatory actions are by nature reactive, thus consistent with backlash. Retaliation aims to more broadly challenge persons, institutions, norms, and principles that are related to the backlash target. It feeds into backlash because any actors or institutions considered sympathetic to the backlash target are viewed as threatening backlash actors’ standing, society, and more fundamentally existence. In retaliating against backlash target sympathisers, backlash participants are not so much interested in seeking a compromise but instead are driven by a moral conviction (discussed above) to advance their norms and principles as universally valid. Retaliation reinforces backlash actors’ moral position by destabilising other actors, ideas, and institutions that challenge backlash goals. It imposes costs on backlash target sympathisers – for instance, by increasing risks to their personal safety, advocacy, and legitimacy – and prevents them from speaking up or continuing their opposition to backlash movements.Footnote 57 Recalling right-wing populism, populist supporters attack not only individual human rights and democratic norms but also civil society organisations, multilateral institutions, the principle of the international rule of law, and the liberal international order. Through this wider attack, retaliation reinforces what Lipset and Raab discuss as ‘the closing down of the ideational market place’, because the heightened risks for the target sympathisers can suppress pluralism in ideas and institutions that makes it possible for diverse actors with clashing interests to reach a compromise and coexist.Footnote 58 Retaliation can therefore increase the salience of backlash goals and grievances by downplaying competing ideas and actors that challenge backlash movements. Emotional backlash can lead to three possible outcomes, discussed below.

Component 3: Outcomes

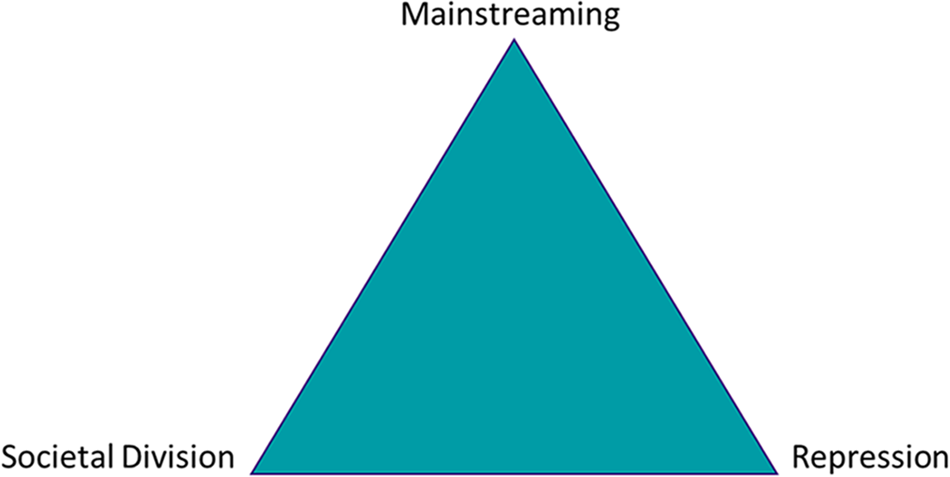

The third component of emotional backlash captures the outcome of emotional backlash through elites’ reaction. As explained by Alter and Zürn, backlash can produce mainstream discourse and policy, societal division, and repression.Footnote 59 The outcomes are presented in a triad (Figure 1), which shows the distinction of each outcome while also implying the possibility that they may co-appear (discussed below). It represents a range of possible outcomes that allows scholars to examine backlash movements even if backlash fails.

Figure 1. Backlash outcome.

Backlash movements can yield three outcomes. First, backlash can garner enough support and generate political dynamics to the extent that backlash claims reflect a mainstream discourse and policy.Footnote 60 The normative congruence between backlash actors and ruling elites can also increase the chances for backlash claims to infiltrate mainstream discourse and policy. After becoming public discourse, backlash movements are understood to have reached a threshold of becoming a full-fledged backlash politics that fulfils the retrograde goal.Footnote 61 The first outcome represents a successful movement where policymaking serves backlash demands. However, if backlash does not succeed, it can lead to two other outcomes. In the second outcome, the ruling elites can suppress the movement. The repression of the backlash movement results in no fundamental change, and thus the failure of backlash. In the third outcome, backlash actors are unable to achieve their retrograde objective but manage to create societal divisions among different pockets of populations.Footnote 62 This means backlash movements may be tolerated within a democratic space where political expressions are possible.Footnote 63 To be sure, like the previous two components of backlash, the separation of the three outcomes serves analytical purposes. In reality, authorities’ responses may simultaneously result in all three outcomes to a certain degree. For instance, in the backlash against the 2020 election in the US, there was a mainstreaming of electoral fraud claims alongside societal division and repression with the arrest of more than 725 individuals after the January 6 insurrection.Footnote 64 With the elaboration of emotional backlash in this section, the following sections discuss research methods and the emotional backlash against Rohingya refugees.

Data and method

To assess sentiments towards Rohingya refugees during the pandemic, I performed a keyword search ‘Rohingya’ on a public Facebook group, ‘Friends of Immigration’, and on public Facebook pages of the Malaysiakini and Star news outlets between April 2020 and January 2021. The Friends of Immigration page is run by current and former immigration officials in an unofficial capacity and has attracted 96,000 followers. It regularly posts materials with anti-migrant tendencies, including news, pictures, and videos of migrant arrests in Malay language. In contrast, Malaysiakini is an independent newspaper, established in 1999, and publishes news critical of the government and societal issues in English, Malay, and Chinese. Its Facebook page has 1.8 million followers with average daily visits from 15,000 to 313,385.Footnote 65 The third source, The Star, is a mainstream media outlet, owned by the Malaysian Chinese Association, a political party within the Barisan Nasional coalition that ruled from 1957 until 2018.Footnote 66 It has the largest English-language circulation, with 1.7 million followers on Facebook. The Star reports a mix of official sources, refugees’ plight, and UN agencies’ pleas on behalf of refugees. The three sources are suitable for assessing virtual contestation among stakeholders of diverse normative stances. The range of sources facilitates data triangulation across the political spectrum and yet reveals the overwhelmingly xenophobic sentiments towards refugees.

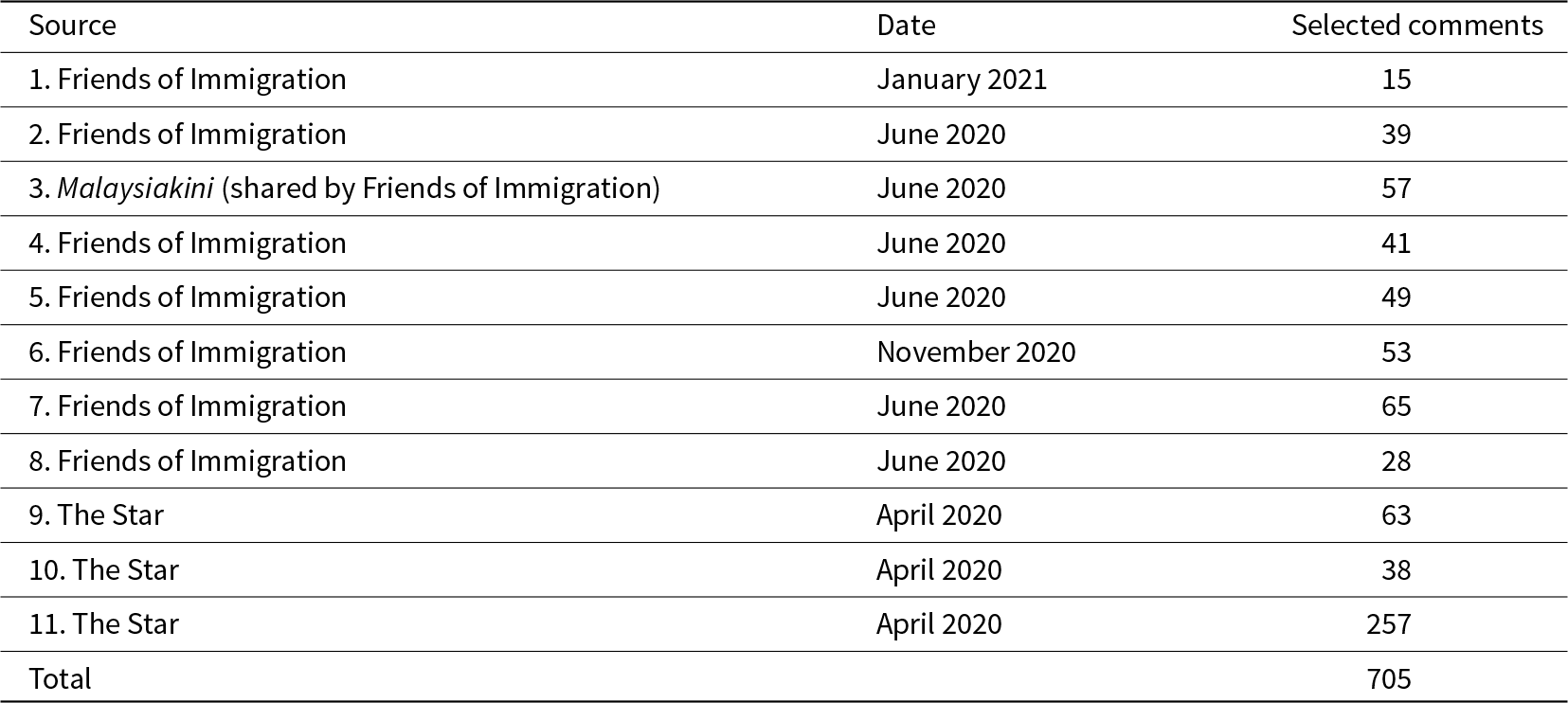

The sampling of online remarks follows the purposive approach based on the research focus that aims to explore how actors perform emotions to contest norms and produce a form of radical politics, namely emotional backlash. To ensure the adequacy of interpretation, I deployed the strategy of immersion in the data through repeated readings of online remarks as ‘these repeated forays into the data ultimately lead the investigator to a deep understanding of all that comprises the data corpus (body of data) and how its parts interrelate’.Footnote 67 I used translation tools for comments in Malay.Footnote 68 Translated comments that lacked clarity were validated by a native speaker and, if they remained unclear, were discarded from the text corpus to guarantee data trustworthiness. For relevance and feasibility, I selected 347 comments from the Facebook group and 358 comments from the news posts (see Table 2). To safeguard privacy of users, this study anonymises and stores data with the author under the data protection plan (Ethics Protocol HEC24185). One shortcoming of the data is that the online profiles do not disclose users’ demographics. Contacting each account would not only be infeasible but would also entail asking intrusive and sensitive questions. To address this limitation, the online remarks are considered as truth claims that purport to represent public discourses and sentiments in order to influence how the locals should feel and act in response to refugees’ arrivals. Thus, the online discourses are crucial for understanding the construction of social reality in the environment of online disinformation against Rohingya refugees.

Table 2. Text corpus.

This study deploys qualitative coding strategies to categorise the salient attributes and patterns of online comments in qualitative data analysis software, NVIVO. Given the research focus on unpacking radical contestation of norms, the main categories of ‘goals’, ‘strategies’, ‘norms’, and ‘target of contestation’ were created and substantiated with data-driven codes: for example, a specific norm of non-refoulement under the ‘norms’ category. In addition, concept-driven codes commonly discussed in academic literature were incorporated: for example, emotion terms, emotional connotation, emotion metaphor were codes under the main category of ‘strategies’. The use of a data-driven and concept-driven coding technique facilitates the theory-building exercise by ensuring methodological rigour and synergies between new empirical data and existing studies. For coding reliability, the researcher reviewed the categories and codes and recoded the online remarks in the second coding cycle.

Furthermore, critical discourse analysis is used to shed light on how the codes and categories interrelate. Critical discourse analysis aids the researcher by putting the patterns that emerged from the coded online remarks into context, illuminating how online claims to collective representation, emotions, and norms interact in social and political relations.Footnote 69 This entails viewing online comments as a discursive manifestation and exercise of power relations that shape emotions, norms, and beliefs. It elucidates the social processes of hierarchy building, exclusion, and subordination, especially of Rohingya refugees.Footnote 70 This method is further aligned with the discursive approach to the study of political emotions, which views the role of language as sites through which emotions are constituted and experienced in shaping perceptions and actions of both individuals and groups.Footnote 71 Critical discourse analysis is therefore suitable for reconstructing the emotional backlash against Rohingya refugees, as well as refining the theoretical knowledge on radical contestation.

Malaysia’s treatment of refugees

Malaysia has a mixed record on refugee treatment. Its immigration law does not distinguish irregular migrants from refugees, subjecting them to whipping, fine, and/or detention before deportation.Footnote 72 Malaysia is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention and lacks a domestic legal framework to process a refugee status. However, consistent with Article 31 of the Refugee Convention, the 2005 Attorney General’s Circulation instructed that refugees registered by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) should be exempt from immigration-related prosecution in court and released from charges pertaining to unauthorised entry. Further, although Malaysia has not ratified the Refugee Convention, the non-refoulement norm – the prohibition of returning refugees to risk of irreparable harm – has been widely recognised as customary international law by opinio juris (state practice and belief amounting to legal obligation), legal scholars, and the UNHCR.Footnote 73 Thus, the norm is implicitly binding on all states, imposing a de facto obligation on states to admit refugees and grant access to safeguards, regardless of ratification.

Rohingya refugees, as with other Muslim refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia, and Bosnia, are in a more tolerated position in Malaysia than refugees from Africa or the Indian subcontinent, due to the country’s appeal to the ‘Muslim brotherhood’.Footnote 74 The country hosts approximately 100,000 Rohingya refugees, with the first Rohingya settlement dating back to the early 1980s.Footnote 75 Malaysia’s compassionate reception of the Rohingya was facilitated by the shared religious affiliation between the impoverished community of Muslim refugees and most Muslim Malaysians. It offers the Rohingya a relatively sheltered environment without having to undergo official resettlement processes.Footnote 76 To be sure, this is not to deny instances of the exploitation of refugees and undocumented migrants, such as official arrests and extortion for bribes, among others.Footnote 77

The toleration of the Rohingya was also influenced by Malaysia’s ‘global Muslim solidarity agenda’ during the Najib Razak’s administration (2009–18).Footnote 78 Najib publicly criticised the Myanmar government for committing violence against the Rohingya. The subsequent administration of Mahathir Mohammad (2018–20) also retained the Rohingya solidarity. Speaking at the UN General Assembly a few months before the Covid-19 outbreak, Mahathir condemned the Suu Kyi government and the UN for their inaction in protecting the Rohingya.Footnote 79 His newly formed coalition government, Pakatan Harapan, initiated the Malaysian Rohingya Council as a consultative platform for the collective representation of Rohingya refugees. At the peak of the solidarity movement, the Rohingya community enjoyed broad access to policymakers, the royal families, and local and international media.Footnote 80 This suggests a favourable view of the Rohingya among the Malaysian public.

A critical turning point in the perception of the Rohingya came with two interrelated incidents at the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. The first incident involved the arrival of the first refugee vessels on 5 April 2020 shortly after the lockdown. In the second incident, the leader of Myanmar Ethnic Rohingya Human Rights Organisation Malaysia (Merhorm), Zafar Ahmad Abdul Ghani, was contacted by domestic and international media to make comments regarding the refugee boat arrivals. On 21 April 2020, Merhorm issued a statement, requesting world leaders to protect Rohingya refugees. However, online disinformation singled out Zafar, asserting he demanded the Malaysian government grant citizenship to the Rohingya community.Footnote 81 These two incidents triggered immense feelings of resentment towards the Rohingya, which morphed into the call to eradicate the Rohingya refugees’ presence and the radical challenge to civil society solidarity, wider humanitarian and cosmopolitan principles, and UN agencies, discussed below.

Emotional backlash against Rohingya refugees

Resentment-driven goal of restoring Malaysia without refugees

To initiate a backlash, social media users problematised the arrival of refugee boats and the Rohingya activist Zafar. The UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights Defenders identified two unknown individual Facebook accounts that instigated the campaign against Zafar and the Rohingya community.Footnote 82 The first Facebook user posted on the same day as Zafar’s statement, urging the Malaysian government to be stern with the Rohingya group and fellow citizens to attack Zafar’s Facebook account. The second Facebook account posted a picture of Zafar, claiming that he was demanding full citizenship rights. Within 24 hours, Zafar’s Facebook received almost 20,000 comments, including insults and death threats. Moreover, in response to the refugee boats, online discourses purported that the Rohingya ‘came here and [became] disrespectful towards Malaysian[s]’. Through negative representation, social media users claimed Rohingya refugees were an affront to Malaysian citizens.

Facebook users cultivated resentment towards Rohingya refugees in Malaysia. Digital discourses articulated resentment through the feelings of insecurity, anger, and hatred. To illustrate, the following comment captures the local insecurity in ethnic terms when reacting to the refugee vessels: ‘Please have enough ethnicities in Malaysia … if you want to add … just take the orangutan … don’t take the foreigners.’Footnote 83 Other Facebook users propagated the feeling of anxiety in political terms: ‘We are afraid that we will get worse and more ethnic Rohingya [will have] power in Malaysia.’Footnote 84 The resentment was also framed as ‘people’s anger’ at the Rohingya, who were perceived as arrogant for making their demands to the Malaysian government.Footnote 85 The disgust at the Rohingya’s perceived unworthy position in Malaysia was succinctly captured in the following hateful remark: ‘This illegal garbage race doesn’t deserve to live in Malaysia’s land.’

Resenting a mutual target paved the way for advancing the goal to restore a ‘pure’ Malaysia without Rohingya refugees. Social media users promoted the nativist vision of ‘Malaysia for Malaysians’,Footnote 86 which aimed to consolidate the social standing of ethnic Malay, Chinese, and Indian citizens who fought for Malaysia’s independence in 1957 vis-à-vis the refugees. Such a vision called for the return of the perceived harmonious coexistence between the three ethnic groups without the disturbance by the Rohingya. Cultivating both the resentment and backlash goal, this online remark traced the idealised social condition to Malaysia’s independence:

You [Rohingya refugees] have overstayed. We, Malaysians do not want your presence in our country … Don’t let the sacrifices of our forefathers, our parents who fought for the independence of Malaysia be in vain. Rohingyas are not welcome [in] Malaysia.

Other Facebook users reaffirmed: ‘Worried, Fear, Threat, uneasy with their [refugees’] presence. Where we live used to be harmony and pleasant.’ The retrograde goal juxtaposed the destabilisation of Malaysia by ‘unwelcome’ Rohingya refugees with the imagined harmony in the past. Resenting Rohingya refugees was thus crucial to depict both the refugees’ undeserving status and an alternative society prior to their entry. It also signified the challenge to the normative status quo and the demand for an alternative ‘harmonious’ normative and societal order in Malaysia based on nativism.

The resentment towards the Rohingya consolidated a moral conviction, entrenching the negative interpretation of the refugees beyond evidence. For instance, the UNHCR publicly denied the false claims made by two Facebook posts, which were shared more than 900 times, that UNHCR-registered refugees received RM35 ($7.50) per day.Footnote 87 Despite the UNHCR’s public denial, social media users directly responded to the UNHCR’s statement: ‘Why are they [Rohingya refugees] still here for 30 years. And do you know how many cases of crime and illegal business they have done? Who [are the] victim[s]? Malaysian Citizens.’ By claiming citizens to be the victims in a collective sense, such remarks did not present any evidence but further conveyed the resentment towards the refugees’ unworthy position. It demonstrated the negative beliefs of the Rohingya in committing wrongdoings against citizens, thus reaffirming the Rohingya’s presence in Malaysia as morally wrong. As asserted by the director of a Malaysian human rights NGO called North South Initiative, Adrian Pereira, many who lent support to anti-Rohingya campaigns ‘did not bother to verify the claims’.Footnote 88 This suggests individuals who opposed refugees had already made up their mind regardless of the facts. The moral conviction provided mobilisation opportunities for backlash supporters to engage in the three radical strategies below.

Radical strategies against refugees and sympathisers

The backlash against Rohingya refugees gained support from the middle and upper classes. A Malaysian analyst who researches online disinformation, Harris Zainul, asserted that backlash participants were ‘undoubtedly normal social media users responsible for spreading and perpetuating the anti-Rohingya rhetoric’.Footnote 89 They deployed the three radical strategies to mobilise for the goal of eliminating refugees from Malaysia.

Taboo-breaking. Backlash supporters broke the taboo by seeking to strip the Rohingya of their recognised refugee status and demanding deportation. The claim rejected both the international recognition of the Rohingya as being the world’s most persecuted minority and the non-refoulement norm. This is in stark contrast to the UNHCR’s stance that reaffirms the global validity of non-refoulement. As observed in the UNHCR’s approach to the issue of Malaysia’s status as non-signatory to the Refugee Convention, the organisation argued:

The customary international law principle of non-refoulement … is binding for all states, regardless of whether they have signed the 1951 Convention … [Therefore, Malaysia] has a responsibility to not forcibly return refugees to a situation where their lives or freedoms may be at risk.Footnote 90

The UNHCR further contended that the UNHCR registration card serves the purpose of recognising UNHCR-registered refugees’ need for international protection and safeguards against deportation. However, backlash participants challenged both the refugee status and the non-refoulment norm by extraordinarily asserting the Rohingya were not genuine refugees and lacked legal personhood and entitlement to human rights protection, thus being deserving of forced repatriation. Countless social media users used the label ‘PATI’ (Pendatang Asing Tanpa Izin, or ‘illegal immigrants’ in English) to portray the illegality of Rohingya refugees, while other Facebook users alleged that the refugees were in fact economic migrants who abused the migratory processes and should be returned:

How many times do you want to say that Rohingya is not a refugee but an economic migrant because … Cox[’s] Bazar is not a place of war … [It] is the shelter of Rohingya … so the Malaysian government should firmly send back the Rohingya economic migrant to Bangladesh.

Such discursive utterance excluded the Rohingya from the ‘refugee’ category and international protection. In this circumstance, the totality of the personhood of irregular migrants is reduced to being PATI or ‘illegal aliens’. These labels portrayed refugees as being dishonest, threatening, and unwelcome. In invoking such discourses, backlash supporters rendered the deportation of refugees thinkable through the language of illegality that voided their refugee status and asylum claims. The remarks further facilitated the violation of the non-refoulement norm and, in turn, contributed to the goal of cleansing Malaysia.

Extreme emotional rhetoric. Taboo-breaking was used together with extreme emotional rhetoric, involving emotive and dehumanising discourses. Backlash participants commonly used negative emotion terms when discussing Rohingya refugees’ arrivals. For instance, ‘I’m sick of seeing it … Get rid of everything without leftover of the garbage race to Cox[’s] Bazar’.Footnote 91 This statement explicitly expresses the feeling of sickness, inciting disgust at the Rohingya’s presence. Moreover, the combined use of emotional connotations and metaphors advanced an extraordinary claim that Rohingya refugees were not humans: ‘Dammm … no wonder mymr [Myanmar] killed them [the Rohingya] because [of] their behaviour and they are giving birth like cats [that] don’t have control.’ Such rhetoric showed the attitude of the speaker, alleging it should not be surprising that the Rohingya were massacred because of animal-like behaviours. Backlash supporters also propounded resentment and invoked racial grounds for eliminating the Rohingya while calling for collective action among citizens:

Malaysians are getting more and more unbearable. Better to upgrade the defense system as soon as possible, and get rid of ALL races from Bumi [native] Malaysia. Before all Malaysians [are] raging, before all Malaysians act […] on their own.

Countless emotional metaphors display contempt at Rohingya refugees by using dehumanising labels such as ‘illegal garbage race’, ‘dogs’, ‘parasites’, ‘disease carriers’, and ‘evils’. Like the PATI label, dehumanising language reduces empathy for refugees and denies them personhood and entitlement to human rights protection. Similar to taboo-breaking, extremely emotional rhetoric also paved a way to the goal of deporting refugees in order to rescue Malaysia by creating feeling rules that left little to no room for compassion for the Rohingya.

Retaliation. Consistent with restoring a harmonious Malaysia without refugees, social media users retaliated against refugee sympathisers, specifically human rights advocates, UN agencies, and the broader principles of humanitarianism and cosmopolitanism that underpin non-refoulement. Their response to NGO and UN pleas to safeguard the Rohingya at sea and against deportation suggests the awareness of Malaysia’s obligation under customary international law and represents the challenge to norms, principles, and actors that defend refugee protection. To elaborate, a vocal Malaysian NGO, Tenaganita, was singled out for not being truly Malaysian and betraying the motherland after it appealed to the government to accept refugee boats. The director of Tenaganita was targeted and had her pictures publicly circulated online. Backlash participants conveyed:

Why is this ‘Tenaganita’ what she [the director] said, all the news must be concerned about? Just ignore it, it’s not pure Malaysia either … not [her] ancestors struggled for independence, even school may not be mixed with other races … what is [her] patriotic spirit in the country??Footnote 92

Repeating the reference of a racially ‘pure’ Malaysia in the above remark, other backlash supporters used racial insults to further their goal of removing any impure elements by attacking Tenaganita’s director: ‘This strong NGO person looks like an immigrant face. No wonder.’ Other activists were subject to rape threats and doxing, where their identity card number, phone number, car licence plate, and pictures of activists’ young family members were distributed online.Footnote 93 One Facebook post that attacked activists was shared more than 18,000 times, suggesting a public endorsement of such attacks. A coalition of 69 NGOs described the attacks as ‘mobilising support online … with the objective of terrorising and silencing critical voices and opinions that are often in defense of justice and the human rights of people facing multiple discrimination’.Footnote 94 Such retaliation can create long-lasting effects in weakening solidarity and refugee protection by raising the cost for human rights advocates to continue their operations and shutting down ideas that stood in contrast to the backlash goal of restoring the idealised harmony among citizens.

The retaliation expanded to target UN agencies. Backlash participants aimed to eliminate the influence and legitimacy of the UNHCR. The UNHCR is the custodian of the 1951 Refugee Convention, which sets the global normative standards on refugee protection, including the non-refoulement norm. It is bestowed with the supervisory mandate of monitoring and ensuring state compliance with refugee protection norms. As the UNHCR explains, its operation reinforces and is underpinned by the humanitarian principle, the crucial foundation that facilitates the protection of refugee.Footnote 95 Certainly, retaliating against the UNHCR symbolises an attack on the legitimacy of the humanitarian principle and international institutions in both regulatory and organisational sense.

The retaliation against the UNHCR is demonstrated in backlash participants’ rejection of the UNHCR and its refugee card. As articulated by a Facebook user: ‘By just issuing refugee cards [it] doesn’t give one the authority to demand equal rights in any country … UNHCR instead of barking do play your role … No one wants them [refugees]. It’s bloody business of UNHCR to protect and feed them.’ Similarly, after the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights spokesperson Rupert Colville urged Malaysia to rescue refugee vessels adrift at sea, social media users responded by demanding that the agency ‘shut up and resign’ and that the refugees be deported to Colville’s home. The opposition extended to calls for the eviction of UN institutions and refugees altogether:

UNHCR office needs to be closed. This is our motherland. We need to protest & combat before rice becomes porridge for the sake of people, land & generations of great grandchildren will come. Please send them all back to their home country before giving birth to many more children & many problems. Prevent it before it’s too late.

The above statement illustrated extraordinary claims which opposed the specific non-refoulement norm while seeking to roll back the influence of any persons and organisations which defended refugee rights.

Besides targeting NGOs and UN agencies, backlash participants further retaliated against the humanitarian and cosmopolitan principles which underpin refugee protection. Barnett asserts that humanitarianism facilitated the rise of global concerns on refugee protection, and both the humanitarian principle and refugee protection norms are intertwined.Footnote 96 Humanitarianism signifies a desire to reduce the suffering of strangers and preserve their life. It also relates to the equality norm in human protection regardless of nationality, race, religion, gender, or political opinion. Equality further bolsters the cosmopolitan outlook on humanitarianism to protect strangers regardless of cultural difference. This is central to upholding the dignity and rights of refugees.Footnote 97 However, backlash supporters redefined the humanitarian principle by precluding refugees from humanitarian assistance and alternatively promoted an exclusionary and discriminatory form of humanitarianism. The following comment rejected humanitarianism extended to the Rohingya: ‘Humanitarianess start[s] from home … Msia [Malaysia] is not a free breeding country for refugees and do not use race and religion to enter msia.’ Reaffirming the resentment at the humanitarian protection of Rohingya refugees, another Facebook post asserted: ‘We, Malaysians have suffered long enough of these people’s [refugees’] existence. They have to go, period.’ Contradicting the non-discriminatory basis in human protection, such resentful assertions excluded the suffering of refugees from the community of those who deserved humanitarian assistance.

In promoting the exclusionary form of humanitarianism, backlash participants aimed to restructure Malaysian society based on discrimination and racism in contrast to cosmopolitan societies that embraced diversity, differences, and inclusivity of strangers. The following comment succinctly captures the wide-reaching discriminatory attitude: ‘Let this boat sink with this creature [Rohingya refugees] … I am really racist for the benefit of my own nation.’ Discrimination against refugees was broadly welcomed, as observed by a social media user who presents as being an ethnic Chinese citizen: ‘It’s pleasing to see now that even the Muslims in Malaysia are turning against them [the Rohingya]. Finally everyone is in the middle ground. They have undoubtedly created too many problems for us.’ Such claims did not only portray a consensus among the locals but also viewed discrimination against refugees as normatively desirable for uniting citizens to protect Malaysian society. Moreover, the promotion of racism appeared to be deliberate and justified even in violating the Islamic code of sadaqah (the voluntary act of charity and compassion extended to other beings):

I ask Allah [for] forgiveness … You know who else says this [xenophobic hate speech] to minorities? Nazis … Chinese gov[ernment] on Uighur Muslims, Trump. Muslim minorities were considered vermin/rats … Hopefully Allah forgives you.Footnote 98

Such remarks revealed the consideration that Malaysia was grouped together with the conservative, racist, and far right as part of the broader xenophobic backlash overseas. The rising xenophobia against refugees represents a stark contrast to the country’s famous tagline of ‘Malaysia Truly Asia’, which ‘resonates with Malaysia’s cosmopolitanism that has attracted diaspora from Asia and beyond to call this land their home’.Footnote 99 By rejecting the humanitarian and cosmopolitan principles, backlash supporters therefore prioritised discrimination and racism as a ‘normal’ organising principle for their society.

The three radical strategies – taboo-breaking, extreme emotional rhetoric, retaliation – were used by backlash supporters to secure the nativist goal of reverting Malaysian society to a perceived harmonious state for citizens along ethnic lines. These strategies became the tools used to eliminate any unwanted influence of refugees, human rights defenders, and UN agencies who obstructed the backlash goal. Furthermore, in attacking the existing societal and normative order, social media users instead promoted discrimination and racism as a ‘normal’ organising principle in Malaysia. Such negative sentiments and backlash demands pervaded official responses, shown in the next section.

Outcome of refugee deportation and entry prevention

The Perikatan Nasional government (2020–1) did not suppress the online hatred towards the Rohingya nor did it bring individuals responsible for inciting attacks on the refugees to account.Footnote 100 Rather, authorities affected solidarity with the Rohingya by delegitimating Rohingya refugees and the UNHCR, and implementing the policy of refugee deportation and entry prevention. Without condemning the backlash against the Rohingya, the official response can be interpreted as giving a tacit endorsement of the backlash demand. It represents further backlash against the refugees, feeding into the resentment and backlash goal.

After the first refugee boat arrival on 5 April 2020 and the disinformation against the Rohingya activist on 21 April 2020, Malaysian home minister Hamzah Zainudin issued a statement on 30 April 2020, dismissing the recognition of UNHCR-registered refugee status and reaffirming the illegality of Rohingya refugees:

Any organisation that claims to represent the Rohingya ethnic group is illegal under the RoS [Registration of Societies] Act, and legal action can be taken … Therefore, Rohingya nationals who are holders of the [UNHCR] card have no status, rights or basis to make any claims on the government … The government does not recognise their status as refugees but as illegal immigrants.Footnote 101

The official remarks reinforced the popular PATI label used by backlash supporters to categorise any refugees as ‘illegal migrants’. This also portrayed the refugees as having committed punishable immigration offences. Importantly, head of the National Security Council Rodzi Md Saad released a draft plan to close down the UNHCR office so that Malaysia could manage refugees ‘without foreign interference’, while also describing the UNHCR mandate of issuing refugee cards without consulting the government as ‘unfair’ and ‘disrespectful’ to Malaysia.Footnote 102 While this plan has yet to be fully implemented in February 2025, the policy illustrated authorities’ shared resentment towards international institutions sympathetic to refugee rights. As such, the official stance could be viewed as downplaying UN agencies’ legitimacy and, in turn, legitimising backlash demands. It also fostered the environment that made backlash possible. This is significant because the dismissal of the UNHCR would cause the Rohingya population and other refugees from 50 different countries in Malaysia to lose their refugee status. Instead, refugee ‘management’ would come under the purview of the National Security Council, making it about Malaysia’s national security as opposed to a humanitarian or human rights issue.

Authorities also implemented the policy of preventing refugee entry, consistent with backlash demands. In June 2020, Malaysian defence minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob indicated that Malaysia planned to return Rohingya refugees detained on the vessel to Bangladesh.Footnote 103 Further reaffirming the ruling coalition’s stance, UMNO (United Malays National Organization) deputy president Mohamad Hasan indicated that: ‘Receiving the Rohingya at times like this could open the floodgates for more foreign nationals and vessels to approach the Malaysian border.’Footnote 104 By June 2020, authorities had already prevented the arrival of 22 boats carrying Rohingya refugees and possibly other migrants.Footnote 105 Consequently, the ruling elites’ action appeared to meet the popular demand of prohibiting the Rohingya refugees’ entry.

The government also conducted a series of immigration raids from May 2020 onwards. Closely tied to the nostalgic vision of a ‘pure’ Malaysian nation, these raids did not only target the Rohingya community but also any undocumented migrants. Home Minister Hamzah stated authorities would ‘round up’ undocumented migrants to ‘protect Malaysians’.Footnote 106 The raids were officially introduced as ‘Op Benteng’ (Operation Fortress), a nationwide campaign with a concerted effort from the armed forces, police, the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency, and the Malaysian Border Security Agency. By the end of 2020, the government had deported more than 31,000 migrants from Indonesia, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand, and China.Footnote 107 The army commander explicitly acknowledged that ‘the locals’ contributed to the success of the operation by actively reporting information to the National Task Force.Footnote 108 This represents evidence of local demands feeding into the authorities’ response, whose combined effort was officially recognised as success. Authorities also stated that, because of integrated actions by state agencies and the locals, Op Bengteng should continue its implementation.Footnote 109 Home Minister Hamzah, who would lead the operation from June 2022 onwards, encouraged further actions from Malaysian citizens: ‘The problem of illegal immigrants can only be stopped if everyone, regardless of employers, ordinary people or anyone … can work with us.’Footnote 110 Thus, it can be observed that the government’s responses were aligned with the resentful backlash goal and radical strategies to reinstate the idealised harmonious society where ‘undeserving’ migrants and refugees did not disrupt the communal peace among citizens of the three ethnic groups. As asserted by Ding, the raids, deportation, and turning back of refugee boats ‘played into the xenophobic backlash against undocumented migrants’.Footnote 111 Consequently, the government’s action and popular backlash demands appeared to be mutually reinforcing.

Conclusion

This article has examined a distinctive form of contestation that is radical. It has illustrated that radical contestation is disruptive as it involves intractable disagreements and seeks to overhaul an existing normative order. To summarise, radical contestation is distinguished by two features. First, it has an extensive scope that challenges norms and wider normative order, principles, institutions, and actors sympathetic to the norm. Second, it involves a high level of emotional intensity in driving contestation. Moving beyond merely discussing the form of radical contestation in this article, I have also brought together the two features of radical contestation and explained the process and effect of radical contestation. To do so, I have advanced the new ‘emotional backlash’ framework to explicate the construction, mobilisation, and outcome of radical contestation. My emotional backlash framework offers added value for scholars of norms and IR to appraise radical contestation more systematically.

By analysing the emotional backlash against Rohingya refugees, I have demonstrated not only the utility of my framework but also the intricate relationship between radical contestation and emotional backlash. I have shown that the form of radical contestation with extensive scope and emotional intensity is embodied in the process and outcome of radical contestation as presented in the emotional backlash framework. In the construction (Component 1 of emotional backlash), backlash entrepreneurs challenged the non-refoulement norm by cultivating resentment at Rohingya refugees, generating the goal of refugee removal and return to the idealised harmonious Malaysian society. The aim to restore harmony without refugees particularly facilitated imaginaries of an alternative normative and societal order based on nostalgia, thus illustrating the extensive scope of the attack on the normative status quo associated with refugee protection. In addition, the intensity of emotions can be observed with the cultivated resentment. Resentment offered moral judgement by depicting the Rohingya as committing wrongdoings against Malaysians, and hence, being undeserving of staying in Malaysia. It cemented the differences between backlash actors and refugees by affirming the negative interpretation of the Rohingya and moral conviction that Rohingya refugees’ presence was morally wrong.

In the mobilisation (Component 2 of emotional backlash), the direct assault on the norm of non-refoulement was facilitated by the radical strategies of taboo-breaking and extreme emotional rhetoric. Using both radical strategies, together with dehumanising slurs, backlash participants dismissed the Rohingya’s refugee status by portraying the latter as ‘illegals’ (PATI) or ‘non-humans’. This served to exclude Rohingya refugees from protection against deportation. Furthermore, with backlash participants’ radical strategy of retaliation, the contestation scope extended to attack the wider humanitarian and cosmopolitan principles, the UNHCR, and human rights defenders. Such retaliation sought to deny Rohingya refugees humanitarian assistance and shut down the ideational space for refugee protection. It in turn led backlash supporters to promote the exclusionary form of humanitarianism as well as racism and discrimination against refugees as a ‘normal’ organising principle in reconstituting the normative and societal order in Malaysia without refugees and refugee sympathisers. Such a nativist vision of Malaysian society stands in stark contrast to the equality in humanitarian protection and cosmopolitanism, targeting the normative foundation which embraces cultural differences and diversity, and which makes the protection of strangers – refugees – possible.

In the outcome (Component 3 of emotional backlash), the official responses to Rohingya refugees also exhibited both the extensive scope and emotional intensity of radical contestation. In challenging non-refoulment, authorities refused asylum to refugees stranded at sea and deported irregular migrants and refugees from Malaysia. In terms of emotional intensity, authorities conveyed resentment at the UNHCR by describing the organisation’s refugee protection activities underpinned by the humanitarian principle and Refugee Convention as ‘unfair’ and ‘disrespectful’ to Malaysia. With such resentment, authorities planned to close the UNHCR office, thus extending the contestation scope to international institutions in the regulatory (Refugee Convention) and organisational (UN agencies) sense. Without suppressing the widespread hatred towards Rohingya refugees, such official responses could be considered as tacitly feeding into the backlash demands to restructure Malaysian society without refugees and their sympathisers. Taken together, the alignment of construction and mobilisation of emotional backlash with the outcome of mainstreaming backlash demands by the elites exemplifies radical contestation – the resentful attack not only on the specific norm of non-refoulement but also on the existing normative order associated with refugee protection.

Building on the above findings, this article steers norms scholarship towards a new research agenda on radical contestation. Emotional backlash seems to be rising globally, therefore giving opportunities for scholars to test the broader applicability of the emotional backlash framework. For instance, scholars are invited to investigate the influence of emotions in US president Donald Trump’s reinstatement of the Global Gag Rule in January 2025. The rule refuses US foreign funding to any organisations that give services in or advocate for sexual and reproductive health, thus not only rolling back women’s rights but also seeking to shut down the ideational space for debates and actors who support the issue on a global scale. In addition, scholars can use the framework to appraise the growing discontent and anger among farmers and coal miners across the European Union, which has been capitalised on by extreme right-wing political parties attempting to imperil climate change governance. These suggestions are by no means exhaustive, and future studies can fine-tune the emotional backlash framework. The task, however, is beyond the scope of this article

Lastly, the radical contestation of refugee protection in Malaysia underlines the broader backlash against the international refugee regime. In Southeast Asia, in February 2025, Thailand deported Uyghur refugees to China, where there is a high risk of torture and enforced disappearance.Footnote 112 The hostility against the international refugee regime can also be observed with the crackdown on migration in Europe and the Unites States. Such hostility fuels resentment and far-right movements to oppose migrant and refugee protection in seeking to rediscover ‘traditional’ values and advance an exclusionary, ethno-nationalist, xenophobic, and anti-immigration society. Consequently, the backlash against refugees in Malaysia, as a non-signatory to the Refugee Convention, represents the contestation exogenous to the international refugee regime. This reinforces the contestation endogenous to the refugee regime by signatory states. The convergence of exogenous and endogenous contestation puts the international refugee regime under duress globally. Contrary to liberal norms and order, the assault on the international refugee regime fosters a culture of moral ‘indifference … unsettling bonds of solidarity and humanity’.Footnote 113 The transformation will be radical, determining whether the international order will become an increasingly equal or racist one.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the RIS editors and anonymous reviewers for their very constructive comments. I would like to extend my deep gratitude to Cecilia Jacob, Bina D’Costa, George Lawson, Janne Mende, Mariam Salehi, Richard Georgi, Joseph MacKay, Jasmine-Kim Westendorf, and Carly Gordyn for their insightful feedback on the previous drafts. Any mistake is solely the author’s.

Funding statement

The research was funded by the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, Government of Switzerland.