Among the many letters, treatises, poems, and histories generated during the sixty or so years that marked the tumultuous period of ecclesiastical reform preceding the Concordat of Worms in 1122, the letter of Archbishop Manasses of Reims (c. 1069–1080) to the papal legate Hugh of Die (bishop of Die, 1073–1082; archbishop of Lyon, 1082–1106), explaining Manasses’s reasons for refusing Hugh’s summons to a council in Lyon in the opening weeks of 1080, stands out for its impassioned defense of archiepiscopal juridical prerogative in the face of Hugh’s legatine privilege. This letter is the last known missive of Manasses.Footnote 1 He was deposed by Gregory VII a few months later and soon disappears from the historical record.Footnote 2 The archbishop’s bitter fight with Hugh and spectacular fall were well known to contemporaries. Indeed, Manasses was the most prominent churchman to be evicted from office during Gregory’s pontificate, certainly in Francia and arguably in Europe as a whole. As I have argued elsewhere, Manasses’s epistolary exchanges with Gregory also held some interest for later generations of canonists and polemicists.Footnote 3

Manasses’s final letter to Hugh has been known to scholars since the seventeenth century.Footnote 4 First dubbed the ‘Apologia’ by Jean Mabillon in 1687—an identification I will adopt here for convenience’s sake—the missive offers a lengthy explanation and defense, on both practical and canonical grounds, for Manasses’s absence from Hugh’s Lyon council, and does so in language that reveals, in equal measures, the legal acumen and caustic wit of its author. But the Apologia, as transmitted by Mabillon and others over the centuries and long a staple source for studies of the reform process in northern France, is not, in fact, the letter that Manasses sent to Hugh of Die in the early weeks of 1080. It is, rather, a longer, reworked recension of the letter that the archbishop originally sent, whose value as a tool for resistance to Gregory’s reform initiatives of the later 1070s became apparent to Manasses’s contemporaries and led to its eventual incorporation into a dossier of texts presumably prepared in anticipation of further confrontations with the pope’s legates. This opposition dossier, regrettably dismantled in the seventeenth century and not heretofore discussed in toto, holds considerable interest for our understanding of how legal sources were deployed and circulated locally to resist the papacy’s attacks on clerical traditions and long-standing practices. The recensions of Manasses’s Apologia likewise reveal a legal community of clergy active in the province of Reims in the last decades of the eleventh century and one form of its learned resistance to Gregory VII’s initiatives. The textual changes introduced into the letter’s second recension are thus key to understanding its later value to contemporaries. Following a discussion of the Apologia’s publication history, I will discuss the background to its composition and speculate as to the reasons for its incorporation in the opposition dossier. In the Appendix, I present a new edition of the recensions of Manasses’s letter to Hugh.

The Apologia: A Textual History

As the denouement in Manasses’s relationship with Gregory, the archbishop’s missive to Hugh has repeatedly drawn the attention of scholars, particularly German academics.Footnote 5 In 1949, John R. Williams (1897–1988) of Dartmouth College published an exemplary study of Manasses and Gregory’s relationship in The American Historical Review, which included the first detailed discussion of the archbishop’s letter in English.Footnote 6 Every one of these authors utilized the version of Manasses’s letter that was first published by Jean Mabillon (1632–1707) and Michel Germain (1645–1694) in their Museum Italicum (1687).Footnote 7 Mabillon, as it happens, was not the first to discover the letter. That distinction belongs to one of two people: either the French royal historian André Duchesne (1584–1640), or, more likely, his older contemporary, the learned Jesuit scholar Jacques Sirmond (1559–1651). Duchesne and Sirmond both encountered the letter among the manuscripts in the collection of the French bibliophile Paul Pétau (1568–1614) and made copies.Footnote 8 Sirmond’s copy is now missing, though it was eventually published, as we shall see, by Benedetto Tromby. Duchesne’s copy is now found in his notebooks, archived in the Bibliothèque nationale de France.Footnote 9

It is difficult to know precisely when Duchesne and Sirmond first came across the letter. It is not mentioned in the Annales ecclesiastici of Caesare Baronio (1538–1607), with whom Sirmond collaborated during his time in Rome.Footnote 10 Baronio, who was a cardinal and bibliothecarius at the Vatican from 1597 until his death in 1607, makes note of Manasses’s summons to Lyon and Gregory’s deposition of the archbishop.Footnote 11 One assumes, had Baronio been made aware of the letter’s existence by Sirmond, he would have made reference to it. The publication of volume 11 of Baronio’s Annales, which covers Gregory VII’s pontificate, may thus provide us with a terminus post quem for the letter’s discovery by Sirmond. Upon Paul Pétau’s death in 1614, Manasses’s letter passed to his son, Alexandre (1610–1672), who eventually sold his father’s collection in 1650 to the celebrated patroness of arts and letters (and Catholic convert) Queen Christina of Sweden (1626–1689), for 40000 livres. On Christina’s death in 1689, her friend, the Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni, later Pope Alexander VIII (1689–1691), acquired her manuscript collection and added it to the Vatican Archive. By the time Duchesne saw the medieval copy in the early 1600s it had been fragmented into two parts, whereas Sirmond, as we shall see below, seems to have viewed the letter while it was still intact. This would indicate that the manuscript leaves preserving the Apologia became separated before Duchesne’s death in 1640 and thus before Alexandre Pétau sold the collection to Christina a decade later. The letter was eventually rebound into two different codices, both of which also contain material originally belonging to the abbey of Saint-Maur des Fossés.Footnote 12 Today, the twelfth-century copy of Manasses’s letter to Hugh first identified and transcribed by Duchesne and Sirmond abides in the Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana under the shelfmarks Vat. Reg. lat. 566 and 863 (= V in the apparatus).Footnote 13

Sirmond was quick to share copies of the letter with his professional contacts.Footnote 14 One of these was the Grand Prior of Saint-Nicaise of Reims, Guillaume Marlot (1596–1667), who published a handful of brief extracts in the second volume of his massive Metropolis Remensis historia, which appeared posthumously in 1679, eight years before Mabillon and Germain published the letter in full in the Museum. Footnote 15 Another was the learned monk Dom Severo Tarfaglioni (d. 1643) of the Carthusian abbey of San Martino in Naples, with whom Sirmond enjoyed a long correspondence.Footnote 16 Benedetto Tromby reported this conveyance, which would have occurred after Tarfaglione’s profession at San Martino in 1616, in a footnote in the first volume of his Storia critico-cronologica diplomatica, which was published in Naples in 1773.Footnote 17 The connection of Manasses’s letter to Naples via Sirmond may seem surprising until we remember that Bruno of Cologne, the schoolmaster at Reims and the founder of the Carthusian order, was one of Manasses’s staunchest opponents, and the Apologia mentions Bruno explicitly.Footnote 18 According to Tromby, it was at San Martino that Mabillon found Sirmond’s copy of the letter, which Tromby also published.Footnote 19 Somewhat confusingly, however, Mabillon would claim that Sirmond had known about only one of the fragments of the letter, not both, and from it had sent excerpts to Marlot.Footnote 20

In ensuing years, two French bibliophiles, Bernard de Montfaucon (1655–1741) and Jean-Baptiste de la Curne de Sainte-Palaye (1697–1781) further publicized the existence of Manasses’s letter in the Vatican archive, as did the Benedictines of Saint-Maur, who noted it in the eighth volume of their monumental Histoire littéraire. Footnote 21 In 1806, the letter was again printed, utilizing Mabillon’s edition, in volume 14 of the Recueil des historiens des Gaules et de la France, edited by Dom Michel-Jean-Joseph Brial, by which point it could hardly have been considered obscure.Footnote 22 Most recently, Patrick Demouy re-edited Manasses’s letter in his 1982 thèse for the Université de Nancy II among the charters of the archbishops of Reims.Footnote 23 Demouy, who at the time presumably lacked direct access to Vat. Reg. lat. MSS 566 and 863, relied on Duchesne’s copy of the letter in the BnF and the editions of Mabillon and Brial.

As I noted above, every one of these erudite scholars utilized the twelfth-century copy of Manasses’s letter found in the Vatican manuscripts formerly belonging to Paul Pétau and Christina of Sweden. This is not, however, the only version of the archbishop’s missive that exists. A shorter recension of the letter—the letter Manasses actually sent to Hugh—survives today in a sixteenth-century copy at the August-Herzog Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel, under the shelfmark MS 27. 9. Aug. It escaped scholars’ notice that the Wolfenbüttel copy of the letter differed from the version found in Reg. lat. 566 and 863, until Martina Hartmann publicized it in her 2001 study of the sixteenth-century Croatian Lutheran scholar Matija Vlačić, otherwise known as Matthias Flacius Illyricus (1520–1575), and his collaborators.Footnote 24 Flacius was the director of the Magdeburg Centuriators, who famously assembled and published historical texts that, they believed, undermined Catholic doctrine and theology. His Flemish colleague, Cornelius Wouters (1512–1555), discovered in 1554 a group of eleventh- and twelfth-century letters contained in a now-lost codex belonging to Siegburg Abbey near Cologne.Footnote 25 Among the nineteen letters, which include correspondence related to the archbishop of Cologne, Rainald of Dassel, Frederick Barbarossa, and the abbey of Siegburg, as well as a series of letters connected to the election of Ivo as bishop of Chartres in 1090, is a clutch of three epistles concerning the archbishop of Reims: Gregory VII’s letter of 22 August 1078 to Manasses (Reg. 6.2); a letter of Hugh of Die (1079) summoning the archbishop to Lyon; and the shorter recension of Manasses’s Apologia. Footnote 26 Already in 1939, the Berlin-based historian Otto Meyer (1906–2000) had examined these letters at length and offered a detailed analysis of their legal arguments concerning the archbishop’s metropolitan privilege, which were central to the exchange between Manasses, Hugh, and Gregory VII. But Meyer seemingly did not notice, or chose to ignore, that the version of the Apologia in the Siegburg collection differed from that published by Mabillon, Tromby, Brial, and the rest.Footnote 27 Carl Erdmann, who published his famous study of eleventh-century German letters the year before Meyer’s article appeared, was likewise fooled.Footnote 28 As we shall see, the assumption that the letters in the Wolfenbüttel and Vatican manuscripts were one and the same has been an easy one to make. Hartmann nonetheless alertly identified the alternative ending of the Siegburg recension of the Apologia and published it in a footnote, arguing that it was a later, abbreviated version of the longer, widely-known recension, an assumption that Meyer may also have shared.Footnote 29 Meyer and Hartmann both astutely observed that the three letters from Siegburg in the Wolfenbüttel codex had likely been assembled for propagandistic purposes, a finding with which I am in agreement.Footnote 30

I believe, however, that the ordering of the recensions should be reversed. That is, the Vat. Reg. copy from the twelfth century, despite its greater length and longer textual tradition, represents a second, augmented version of Manasses’s original letter to Hugh, now preserved in a unique copy in the Wolfenbüttel codex. There are several reasons to think this. The first argument rests on the fact that the epistolary exchanges between Hugh and Manasses over the latter’s summonses to Lyon occurred in a compressed period of time, a matter of a few weeks, which favors the shorter letter as the one first sent. Second, the Wolfenbüttel letter possesses a closing salutation lacking in the Vat. Reg. copy, which ends abruptly and in mid-argument, as it were. Moreover, the additional text in the Vat. Reg. letter, amounting to 380 words, extends an invitation to Hugh, “on our part and that of our king” (ex parte nostra et regis nostri) to attend a meeting in France—information newly introduced only there—and includes four additional canons, adduced to suggest that Hugh’s summonses of Manasses had been both unmeasured and without merit. These final canons and the king’s apparent participation in the archbishop’s invitation read as an afterthought, as Manasses had already presented several legal arguments for why he should not go to Lyon earlier in the letter and no precise mention had been made of an alternate venue for the council. The Siegburg recension, by contrast, ends on a grudgingly conciliatory note, stating that, should a place worthy of both Manasses and Hugh’s dignity be proposed, he would proceed there “calmly” (si loci oportunitas expeteret digno mei vestrique modo responsuri, vobis obviam intrepide procederemus). But the most persuasive reason to identify the Vatican copy as the second recension of Manasses’s letter is because the manuscripts Vat. Reg. lat. 566 and 863 preserve two other letters, both originating in the province of Reims, to which the reworked letter of Manasses was intentionally joined to form what may be reasonably described as a legal dossier defending clerical traditions of marriage and archiepiscopal prerogative in the province of Reims. Let us examine each of these arguments in turn.

The Letter and its Background

Manasses wrote his lengthy, self-justifying, and obstreperous letter to Hugh of Die shortly after Christmas 1079. He had by this point already received two summonses from Hugh, a mere three weeks apart, to attend the council in Lyon. Lyon had not been the first location set for the assembly. That had been Troyes, quite close to Reims, with the council scheduled for that autumn, likely in October or early November. Hugh had, however, canceled the Troyes meeting.Footnote 31 Following his receipt of the summonses, the archbishop embarked on a multi-pronged strategy to avoid going to Lyon. He quickly wrote to Gregory, a letter that has unfortunately been lost, but to which Gregory responded in a reply of 3 January 1080.Footnote 32 He also sent nuncios directly to Hugh, who had been ill and was then convalescing at Vienne. The messengers’ goal, according to a later, hostile report composed by Hugh of Flavigny, was to ply the legate with gifts and pleas in order to win exemption for the archbishop from having to produce six fellow bishops—a condition stipulated by the pope—to serve as witnesses to his innocence and as compurgators of the charges that had been brought against him.Footnote 33 It is possible, perhaps likely, that Manasses sent his letter to Hugh, which in any event he composed after 24 December 1079, with the envoys.Footnote 34

Neither the messengers bearing gifts nor the archbishop’s letter produced the desired effect. The council took place as planned, probably in late January. While we do not know its precise date, Manasses had complained bitterly in his letter to Hugh that by the time the summonses had reached him at Reims, they allowed for a mere twenty days to assemble the six bishops who would swear on his behalf, plus fifteen days’ travel, to reach Lyon at the appointed hour.Footnote 35 Whether or not the archbishop’s timetable can be trusted, Manasses had heard from Hugh by late November or early December (the first summons, which prompted him to write to Gregory), before the second letter from the legate, also unfortunately lost, arrived in mid- to late December. Thus, the communications between Manasses and Hugh took place in a compressed period of perhaps one month during the busy liturgical season of Advent.

This leads us to the contents of Manasses’s post-Christmas letter to Hugh and the different endings of the two recensions. As the letter’s arguments against his attendance have been discussed elsewhere, I will not dwell on them here, except to note that Manasses had been wrangling with Hugh of Die over his presence at Hugh’s legatine councils since 1077. He raised several objections to the legate’s summonses, basing them on his earlier agreement with Gregory about the conditions of any hearing to which he should be called, and on other legal precedents.Footnote 36 A key sticking point for Manasses was that the council could not be legitimately called unless Hugh, the abbot of Cluny, were present at the hearing.Footnote 37 He holds firmly to this in the letter’s conclusion, on the strength of the pope’s apparent earlier agreement to this stipulation. And should the bishop of Die insist on judging Manasses without the abbot present—thereby contravening Gregory’s wishes—then that reason alone, by the archbishop’s reckoning, should furnish sufficient proof that he was exempt from attending.Footnote 38

Manasses does not end his letter on this note, however. He instead simultaneously displays his magnanimity and his contempt for the whole affair—and here his final words, captured in the Siegburg manuscript, deserve to be reproduced in full (the asterisk indicates the point at which the content common to both recensions of the letter ends):

But indeed, although we have been persecuted in this way, which you ought to concede because it is an observable truth, and although we should not respond to you on account of the aforesaid rationale—nevertheless, out of reverence for the lord pope*, an advantageous place should be sought out so that we might proceed out to meet you calmly and render a response worthy of us both. And finally, so that with this ending the office of your legation may be concluded, and the unjust(?) inundations and flood of words, which are neither useful to, nor, if you please, of service to the dignity of the church of Reims or our own, may be vanquished. Farewell, that you may hasten to wish us well.Footnote 39

Here the penultimate sentence follows logically from the one preceding it, and the archbishop closes his letter with a salutation both appropriate for the epistolary genre and—in keeping with his scarcely veiled disdain for Hugh—conditional, if not backhanded. In the longer second recension, however, the phrase “out of reverence for the lord pope” (tamen propter reuerentiam domni papae) is followed somewhat awkwardly with, “it seemed [fitting] to us to show to you even now another reason” (aliam uobis adhuc rationem ostendere nobis uisum est) why Manasses should ignore the summonses. For nearly 400 more words, the alternate ending in the Vat. Reg. recension then goes on to propose different times for Hugh’s council—perhaps in Lent or after Easter—and more suitable locales, closer to Manasses, such as Reims, Soissons, Senlis, or Compiègne, all places where the French king might also assist.Footnote 40 The archbishop pledges to conduct Hugh safe and sound into his chambers and to offer him “useful counsel” (consilium utile uobis damus), providing that the legate treat him with moderation rather than impose a heavy burden that neither he nor his predecessors were accustomed to bear. Should Hugh “persist in his obstinacy” (in pertinacia uestra … permanere) and consider excommunicating or suspending Manasses, the Vatican recension ends by offering a series of four canonical counterarguments, pressing for moderation in judgment on the one hand and stressing the limits of Hugh’s authority on the other. With the concluding words of the fourth canon (Manet Petri priuilegium, ubicumque ex eius aequitate non fertur iudicium), the extended letter abruptly ends.

We do not know precisely when the longer ending was added, by whom, nor to whom this version of the letter was sent, if anyone. Manasses himself, or one of his clerks, is the likeliest author. The Vatican copy has been roughly dated, on paleographical grounds, to the early twelfth century, and of course by then Manasses and Gregory were long gone.Footnote 41 Given the explicit reference to a royal role in any putative council (rege quoque nostro cooperante), the augmented letter may have been either composed in consultation with King Philip or destined for the king and the other bishops of the province whose presence would have been expected at any council. Gregory’s letter to Manasses of 17 April 1080, sharing news that Hugh’s deposition of the prelate at Lyon had been confirmed in the Roman synod, gives no indication that he had seen either version of the archbishop’s letter.Footnote 42 While we may not know for certain the second recension’s intended recipient(s), its value to contemporaries, and perhaps the reason for its composition, are made clearer upon inspection of its codicological setting.

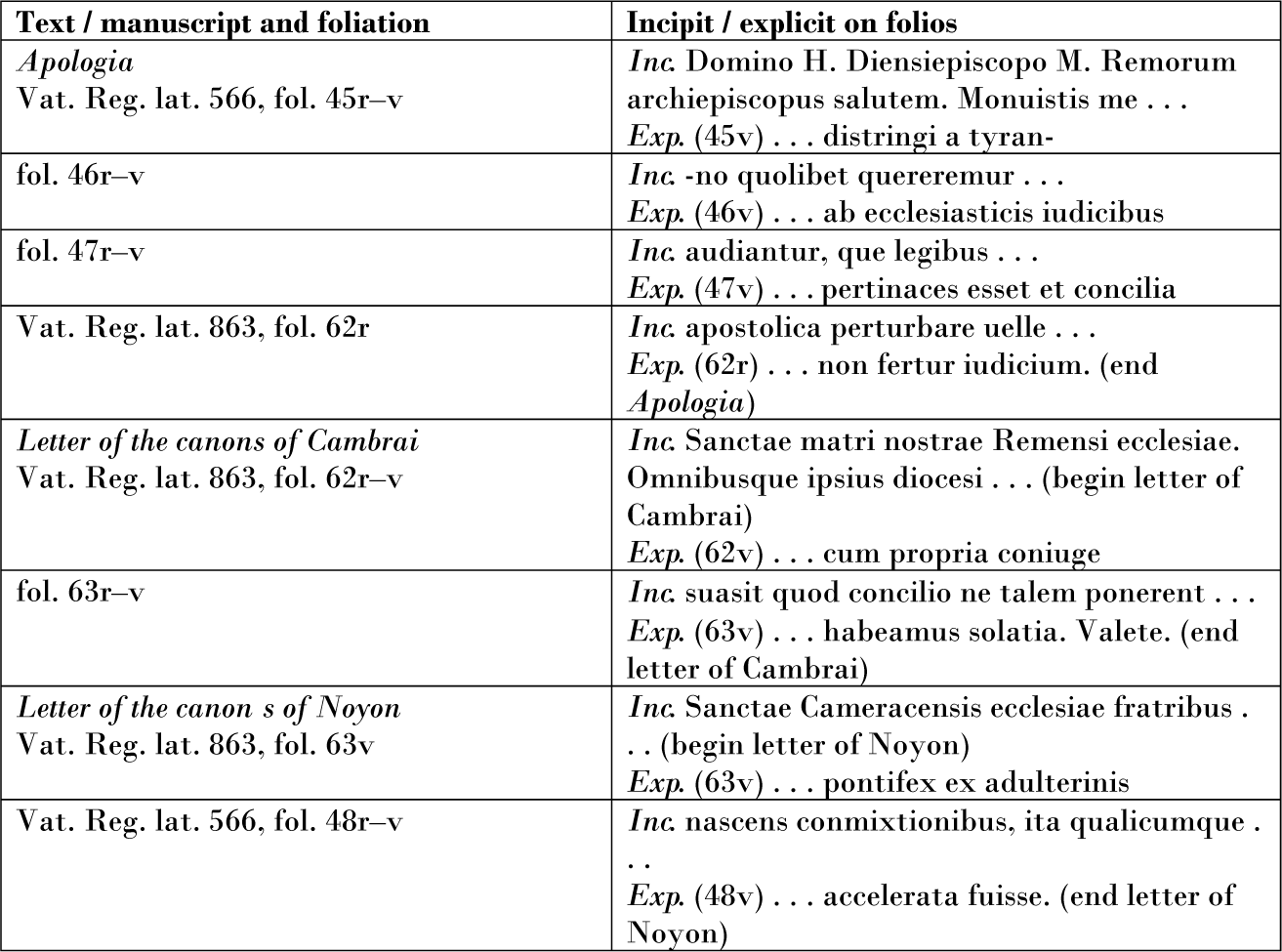

As I stated earlier, the sole medieval copy of Manasses’s letter is, in its current state, divided between two manuscripts, Vat. Reg. lat. 566 and 863. The majority of the letter occupies fols. 45r–47v of Vat. Reg. lat. 566; the conclusion, however, is found on fol. 62r of Vat. Reg. lat. 863. Immediately following the letter’s final words (non fertur iudicium), the copyist has added two additional letters, well known to historians of the debate on clerical marriage that erupted in the 1070s: a letter by the canons of Cambrai, complaining to their fellow canons in the province of Reims about the recent legislation enacted by Hugh of Die at the council of Poitiers in January 1078, and a response to that letter by their fellow canons of Noyon. All three letters were copied in the same hand. As with the Apologia, the letters of Cambrai and Noyon were fragmented and rebound out of order so that the ending of the Noyon letter is “missing” from MS 863; its concluding folio appears immediately after Manasses’s letter to Hugh on fol. 48r–v of MS 566 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Ordering of the Three Letters Across Both Manuscripts.

The disjoined state of the letters, as well as their early publication history, has caused their modern editors no small amount of confusion. It has also obscured the connection of the three letters to one another. Like the Apologia, the existence of the canons’ letters was known to Mabillon, who clarified in the Museum Italicum that the letter of Noyon followed the Apologia in the manuscript, that the Apologia was fragmented (as was also true with the letter of Noyon), and that the manuscript had belonged to Pétau and Christina of Sweden.Footnote 43 He then proceeded to print the complete text of the Noyon letter only, which he could only have done if he knew of both the Vatican codices containing the fragments or if perhaps Sirmond had sent a full copy of those letters to Naples along with the Apologia. Footnote 44 Curiously, and with implications for modern editions of the letters, Mabillon elected not to print the Cambrai letter in the Museum. It had to wait until the publication of the fifth volume of Mabillon’s Annales ordinis Sancti Benedicti, which did not appear for another fifty-three years, and then posthumously, in 1740.Footnote 45

It fell to Dom Brial to tidy things up. Brial was the first to publish the letters of Cambrai and Noyon together, and the first to join them with the Apologia. They appear consecutively in volume 14 of the Recueil des historiens des Gaules et de la France, which was published in 1806.Footnote 46 Indeed, Brial’s edition of all three letters in the RHGF remains the only one to have published them as they once appeared in the Pétau collection; scholars have thus repeatedly and with justification turned to it.Footnote 47 The letters’ partitioning between the two Vat. Reg. lat. manuscripts continued to sow confusion, however. When Heinrich Böhmer edited the canons’ letters anew in volume 3 of the MGH Libelli de lite (1897), he indicated in his preface that he had utilized only Vat. Reg. lat. 863, which lacks the ending to the Noyon letter (Figure 1, above), and so drew on the earlier editions of Mabillon and Brial. Erwin Frauenknecht more recently followed suit.Footnote 48 Happily, we are now in a position to consider all three letters in relation to one another, and it is to this task that we now turn.

Ramparts of Resistance: An Opposition Dossier in the Age of Reform

Although written in response to different circumstances, the Apologia and the canons’ letters have several features in common, a fact that likely explains their coexistence in the Vatican manuscripts. First, Hugh of Die and Manasses figure in all of them, and the letters complain loudly about the intrusion and overreach of Roman legates into local practices, traditions, and privileges. The letter of the canons of Noyon, for instance, mentions Hugh of Die’s first suspension of Manasses at the council of Autun in September 1077, describing it as stemming from “envy rather than [a place of] justice” (per inuidiam, quam per iustitiam), while the letter of the canons of Cambrai strikes a tone sharply similar to that of the Apologia. The Cambrai canons bemoan “Roman” legates, who were:

calling endless councils and bringing to us foreign judgments. And all this through certain imposters, for whom everything has its price and whose ‘right hand is always filled with bribes’ (Ps. 26:10)—namely Hugh [the bishop] of Langres, whose life and habits are well enough known to everyone, and Hugh, the bishop, so they say, of Die, of whom, beyond his name, nothing is known to us.Footnote 49

Although they professed ignorance of Hugh of Die, the canons of Cambrai were clearly familiar with his judgments at Autun, including his sentence over Manasses, whom the legate had termed, in his follow-up report on the council to Gregory, a “heresiarch.”Footnote 50 The cambrésien canons’ own bishop, Gerard II (1076/77–1092), had just been consecrated by Hugh at Autun after Manasses had initially refused to anoint him, and only after he had first purged himself of the sin of simony before Gregory VII.Footnote 51 Gerard had since returned to Cambrai and, having been transformed into an advocate of the Gregorian cause, busied himself with fulfilling the reform measures pronounced at the council of Poitiers, including barring priests’ sons from the choir.Footnote 52 The canons’ grievances concerning the bishop of Langres, who had assisted Hugh of Die at Autun, echo closely Manasses’s complaints in his own letter to Gregory, written soon after the council.Footnote 53 Moreover, in their letter the canons acknowledge their desire to seek an audience with Manasses, whom they likely saw as a potential ally in their fight with Gerard.Footnote 54 For his part, the archbishop resented what he saw as Hugh’s cavalier trampling of Reims’ own prerogative, established by local tradition, to be summoned and judged by the pope, and the pope alone. These were not idle claims to privilege.Footnote 55 That the metropolitan should have to countenance the authority of a legate of lesser clerical rank, and a non-Roman at that, was insulting. On these points, the Apologia and letter of the canons of Cambrai align closely.

The three letters, then, are united in their disdain of external interference and “Roman insolence.”Footnote 56 This alone may account for their presence together in Vat. Reg. lat. 566 and 863. As the canons of Noyon state, however, they wrote in solidarity with their fellow canons’ concerns, and to furnish their brethren with “weapons readied on the ramparts in defense of liberty” (ad defendam libertatem parata sunt arma in propugnaculis), that is, legal texts assembled in defense of their traditions. As we have already seen, this is a feature shared by the second recension of Manasses’s letter to Hugh. Indeed, the second version of the Apologia and the response of the canons of Noyon have an analogous structure: they serve as legal appendices to an initial letter. Thus, to the Cambrai canons’ mustering of four, primarily patristic, sources in defense of their positions, the Noyon clergy added a further seven, drawn heavily from Pseudo-Isidore. To the handful of allusions and direct citations of legal sources in Manasses’s initial letter, which consisted of Roman and Pseudo-Isidorian material, the second recension adds four additional canons drawn from patristic and biblical texts. Both the Noyon letter and second recension of the Apologia thus not only multiply the number of sources, but they also include texts from different fonts of authority, creating, individually and collectively, a legal repository for those who would resist the papal reforms around clerical marriage and the ordination of clerical sons, or who sought legal grounds on which to debate the parameters of the legatine authority or its involvement in provincial affairs.Footnote 57

The audiences and afterlife of this small corpus of texts remain a tantalizing puzzle. Maurice Prou’s analysis of the contents of Vat. Reg. lat. 863 declared that the fragments therein were of French origin, an identification with which I agree.Footnote 58 Unfortunately, we cannot discern the provenance of the copy of the letters any more precisely from examining the other contents of the manuscript, because those fragments’ origins are diverse. We do know that Manasses’s letters, including the Apologia, held interest for readers further to the east.Footnote 59 Strikingly, all four of the canons introduced in the second recension of Manasses’s letter are also found, in precisely the same sequence, in two canonical collections produced in Arras in the 1090s.Footnote 60 These collections, the Atrebatensis and the Sangermanensis (Collectio in 9 volumina, or 9L), are closely related. Atrebatensis is the earlier of the two and likely drew the canons from a source it shared in common with the second recension of Manasses’s letter, as there are enough variants between the two series to make a direct borrowing by Atrebatensis from the Apologia unlikely.Footnote 61 The compiler of Sangermanensis, working a short time later, then incorporated the same canons directly from Atrebatensis. Footnote 62

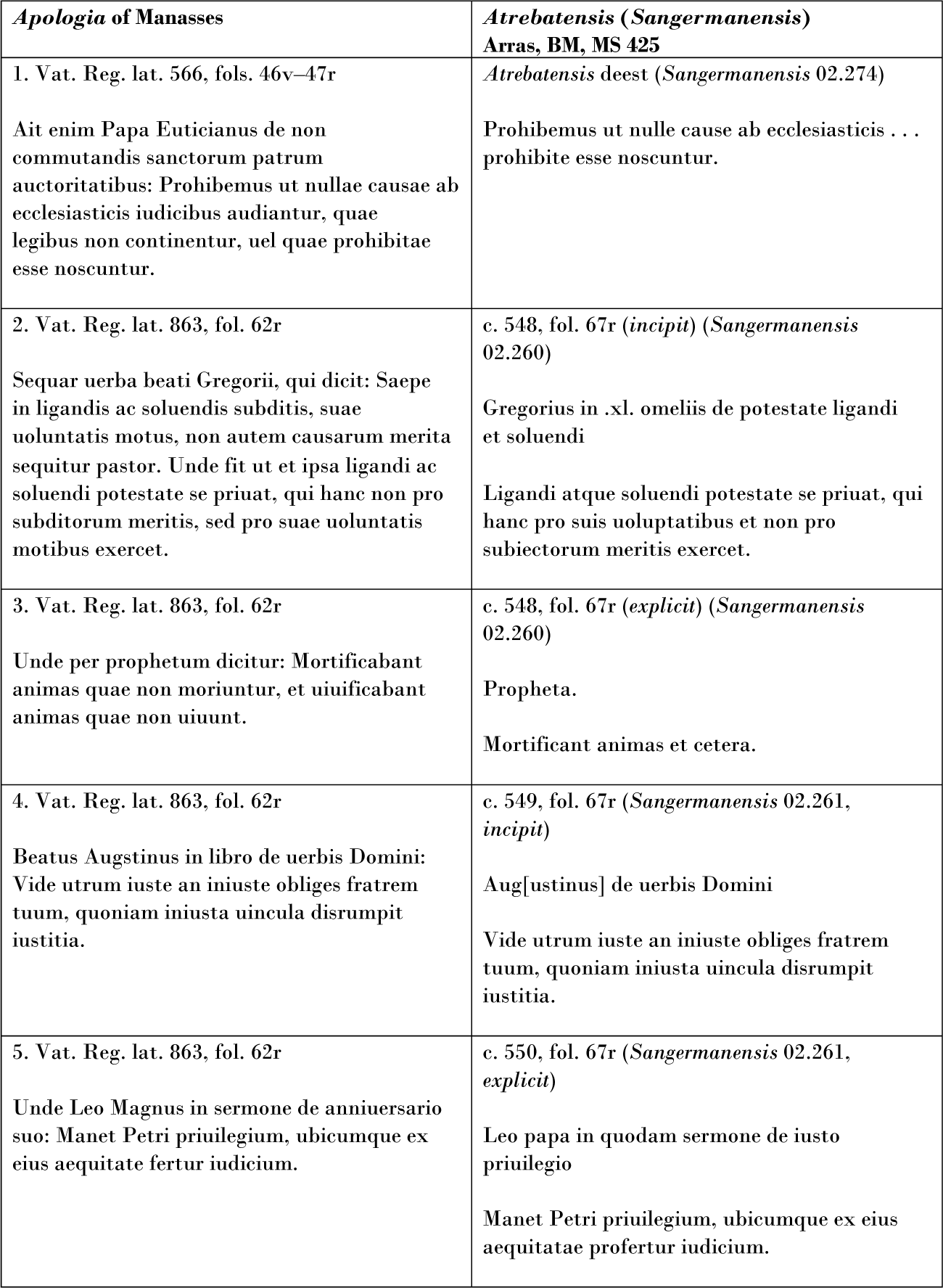

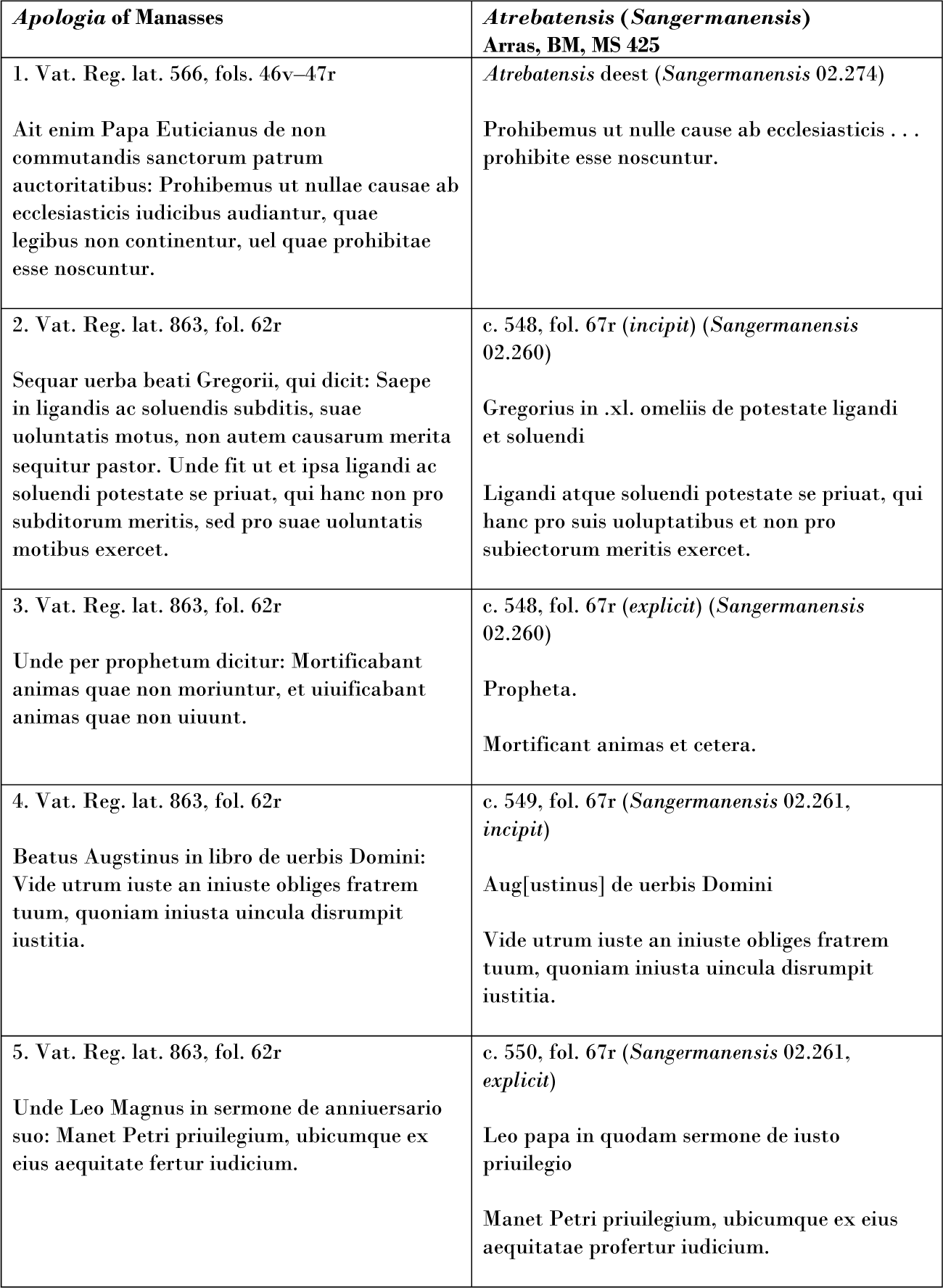

The Apologia’s first recension contains two full quotations from Pseudo-Isidore together with an allusion to a third, plus two paraphrases of Roman law. Of these, only the Pseudo-Isidorian decretal of Pope Eutician (Prohibemus ut nullae causae ab ecclesiasticis iudicibus … prohibitae esse noscuntur) also appears in Sangermanensis (02.274). Unfortunately, we cannot know for certain if that canon’s formal source was Atrebatensis, because the sole manuscript copy of that collection, Arras, Bibliothèque municipale MS 425, is missing the folios on which it would have appeared. For reasons discussed below, it is nevertheless probable. Of the five common canons, the first and fourth are identical in the Apologia and Atrebatensis and/or Sangermanensis; the fifth nearly so (fertur/profertur being the only the variant) (Figure 2). Indeed, of the nine or so canons inventoried in the Clavis Canonum with similar incipits to the Pseudo-Eutician canon on remaining faithful to the decrees of the holy fathers (canon no. 1, below), only the version in Sangermanensis has an identical explicit, thus establishing a strong connection to the Apologia or a shared source. The second and third canons in the table below have been combined and truncated in Atrebatensis, while the second/third and fourth/fifth are combined in Sangermanensis.

Figure 2: The Five Canons Appearing in Common in the Recensions of the Apologia and Atrebatensis/Sangermanensis.

If this material was not incorporated into the Arras collection directly from the archbishop’s letter, then their common source was almost certainly available in the province. But where? Arras-Cambrai offers one possibility, and several factors support this hypothesis. The first has already been mentioned: the canons of Cambrai had a vested interest in Manasses’s fortunes, and they saw him as a powerful ally against the interventions of papal legates such as Hugh of Die. The archbishop’s Apologia, copied down and added to their own letters, would have supplied them with additional ammunition in their complaint against the imposition of new or (as they saw it) unjust legislation, particularly the four new canons of the second recension and the two Pseudo-Isidorian canons common to both recensions.Footnote 63 Second, all six of these canons, focused as they are on mercy, equity, and justice, could be readily included in collections with divergent aims, that is, they could be mustered in defense of tradition and against legatine powers as well as used on behalf of clerical reform or in the service of pastoral oversight.

This fact may explain why five of the six appear in Atrebatensis and Sangermanensis, collections connected with two powerful, reform-minded bishops, Lambert of Arras (1094–1115) and John of Thérouanne (1099–1130). Atrebatensis has been associated with Lambert, the first bishop of the newly-reestablished diocese of Arras, which was uncoupled from Cambrai in 1094.Footnote 64 Lambert’s interest in church reform and canon law is well established, and his register attests to his diligence in recording conciliar proceedings from the first years of his pontificate.Footnote 65 John, attested as archdeacon of Arras from 1095–1099, seems to have had a hand in the creation of the Sangermanensis and perhaps the slightly later Collectio X partium (10P).Footnote 66 Apart from being friends and collaborators, both Lambert and John were from the diocese of Arras-Cambrai, Lambert having served as cantor among the secular canons of Saint-Pierre of Lille, while John was a secular canon at Lille before joining the regular canons at Mont-Saint-Eloi, a few kilometers northwest of Arras.Footnote 67 It is conceivable that Manasses’s letter would have held great interest for the canons of Saint-Pierre of Lille, some of whom no doubt were personally affected by the legislation at Poitiers; perhaps a copy found its way there. While bishop, Lambert also intervened directly in the affairs of Cambrai, which was torn by schism for most of the 1090s between two claimants to the episcopal throne.Footnote 68

Our dossier may also have originated in Reims. The canons’ letters were addressed to their brethren in the province. That naturally included the cathedral chapter at Reims, where a copy of Manasses’s letter(s) to Hugh also, presumably, resided. The legal materials cited in the Apologia’s recensions, namely Pseudo-Isidore and Roman law, were unquestionably available in the archdiocesan archives.Footnote 69 Until or unless other fragments of the Pétau manuscript into which the three letters were copied come to light, their greater codicological setting and the uses to which they were put must remain uncertain. What is clear is that Manasses’s first draft, written in some haste against a compressed timeline, was later reworked to strengthen the legal case for his refusal to attend Hugh’s council at Lyon and at some still later date was joined with the letters of Cambrai and Noyon to form a dossier presenting various legal arguments against the legatine interventions of Hugh of Die and the papal reform agenda as it pertained to clerical marriage. It was not the only such dossier in circulation at the time.

Clerical Textual Networks and Opposition to Rome

In May 1077, Pope Gregory, fresh from his humbling of Henry IV at Canossa, sent Hugh of Die a lengthy letter that has been characterized as a “clarion call” to pursue and stamp out simony in northern France.Footnote 70 Hugh’s councils at Autun, Poitiers, and Lyon followed in short order. The Vat. Reg. dossier sheds valuable light on one network of clerical resistance to Hugh’s legatine activity, spurred by the legislation and summary judgments against prelates issuing from his councils.Footnote 71 Our dossier is by no means the only example of resistance to Gregory’s attacks on simony, clerical fornication, and lay investiture.Footnote 72 The pope’s supporters and opponents alike relied heavily on texts circulated among networks of like-minded allies. With respect to Gregory VII’s ambitions, such networks, linked by friendships and centers of learning, have been repeatedly shown as instrumental to the promulgation of the reform agenda.Footnote 73 Papal letters and other reformist texts were often gathered together in small collections, then distributed among the clerical circles of Gregory’s supporters, propagandizing his vision for the church.Footnote 74 It is no surprise that many of these collections emerged from German circles, though Uta-Renate Blumenthal has shown that interest in the clash between regnum and sacerdotium was not limited to Germany but extended also into the heart of France.Footnote 75 For example, a canonical collection in nine books, formerly belonging to the regular canons of Saint-Victor (Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, MS 721, fols. 165r–250v) and dating from about 1125, contains liturgical texts, papal letters, decrees, and an admonition directed at Henry IV, unattested in other sources, to do penance and be restored to the church.Footnote 76 The legal material, Blumenthal shows, is heavily derived from Burchard of Worms’s Decretum, the Pseudo-Isidorian decretals, and the Collection in 74 Titles, among other texts. Such compendia, which often included episcopal letters, were both morally edifying and furnished useful prooftexts and testaments to papal authority.Footnote 77

Less well-known and decidedly rarer are those dossiers assembled to resist elements of the papal agenda. It seems likely that the letters from the canons of Cambrai and Noyon defending clerical marriage, rather than the archbishop’s missive, were the real draw of our dossier; the Apologia’s canons could be readily coopted for use in the canons’ defense of marriage, whereas the reverse was improbable.Footnote 78 Nevertheless, the compiler of the three letters saw utility in combining them. Manasses—educated at Bec, an ally of the king, accomplished in the study of law (or the patron of those who were)—cut a formidable figure. The letters in the opposition dossier also harken to a wider web of resistance: the canons of Cambrai had been inspired to take up their pens and write to their fellow canons in the province in response to “wise words of [our] neighbors” (finitimorum litteris probabilibus ad resistendum incitati) against the “new dogma” (noui dogmatis) attacking clerical marriage.Footnote 79

The “wise words” to which they referred are found in a work known to scholars as the Tractatus pro clericorum conubio. Brigitte Meijns has argued a strong circumstantial case that its author was the archdeacon and later bishop of the neighboring diocese of Thérouanne, Hubert (1078–1081).Footnote 80 The Tractatus compiles an impressive array of legal and patristic sources in defense of clerical conubium and the ability of priests’ sons to assume holy orders, key concerns for the clergy of Cambrai and which the eighth canon of the 1078 council of Poitiers had explicitly banned. Like the letters of the canons of Cambrai and Noyon, the Tractatus survives in a single copy of around 1100, and, instructively for our purposes, also formed part of a dossier seemingly assembled in defense of clerical marriage, now in the Berlin Staatsbibliothek, Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Theol. lat. qu. 313.Footnote 81 The Berlin manuscript is of broadly similar date and provenance to the materials in Reg. lat. MSS 566 and 863. We find in it, in addition to the anonymous Tractatus in defense of clerical marriage, a copy of the so-called “Rescript” of Pseudo-Udalric (dated by Erwin Frauenknecht to the second half of 1075, originating perhaps in Constance), as well as several groupings of legal material, including extracts from Pseudo-Isidore, a separate, brief collection of five further Pseudo-Isidorian canons (on fols. 39v–40v) that saw distribution in northern Francia, excerpts from a penitential (fols. 41r–42v), and a third compilation of canons (all of which are found in the Polycarpus of Cardinal-priest Gregory of San Grisogono), which collectively argue for moderation in judgment and punishment.Footnote 82 Frauenknecht has argued that the Rescript and Tractatus were transmitted together and thus copied into the Berlin manuscript (where the latter immediately precedes the former on fols. 34r–39r) at the same time.Footnote 83

While the Tractatus pro clericorum conubio and the letters of Noyon and Cambrai survive in unique manuscript copies, the letter of Pseudo-Udalric circulated far more widely.Footnote 84 Other manuscripts of northern French provenance transmit it, including Palermo, Archivio della Cattedrale MS 14, from the late eleventh or early twelfth century. According to Frauenknecht’s analysis, the Palermo manuscript contains an earlier form of the text than that of the Berlin manuscript. But like the Berlin manuscript, the letter was copied into a text consisting of letters—in this case six written by Fulbert of Chartres, together with Gregory VII’s 1077 letter announcing the legation of Amatus of Oloron to the prelates and rulers of southwestern France, Gascony, and Spain—and other conciliar and canonical material.Footnote 85 Pseudo-Udalric’s letter is also found in the manuscript Uppsala, Universitetsbibliothek C 147. The second part (B) of the manuscript is from the twelfth century; there the Rescript is located amidst other canonical excerpts, among which is a letter of 1106 of Pope Paschal II to Bishop Gebehard III of Constance, Bishop Odalric of Passau, and other German clergy and laity (Pro religionis vestrae fervore gaudemus … ab omnibus peccatis absolvat, at fol. 146ra–va).Footnote 86 Pseudo-Udalric was also transmitted through German epistolary collections, including several copies of the famous letter-collection known as the Codex Udalrici, compiled in Bamberg around 1125, and the first codex of the Hanoverian letter collection, preserved today in a sixteenth-century copy in Niedersächsische Landesbibliothek XI. 671.Footnote 87

The foregoing discussion of the circulation of the Tractatus and Pseudo-Udalric is meant to be suggestive rather than conclusive; I aim only to point out that tractates and letters defending clerical marriage frequently circulated with other canonical material, often shorter compendia or extracts. Like these materials, Manasses’s Apologia found a common cause with writings that defended tradition or exhorted moderation in judgment by church authorities. The existence of the Apologia’s two recensions, and its transmission alongside the letters of Noyon and Cambrai in Vat. Reg. lat. 566 and 863, illuminates, with other such collections, a learned, albeit largely anonymous, network of clerical scholars, dominated by canons attached to the great cathedrals of northern France, who drew on their collective legal acumen and a shared legal culture to stage a coordinated resistance to the initiatives of Pope Gregory VII and his legates. A handful of textual remnants bear witness to it, and they must be ferreted out of sometimes complex codicological surroundings. As the textual genealogies of the letters of Manasses and the canons of Noyon and Cambrai testify, editorial choices made centuries ago can obscure the codicological relationships between these texts. Our inherited assumptions about—or blindness to—these relationships were not shared by their medieval authors and copyists, who often found value in the legal material conveyed by otherwise seemingly disparate texts. Because so much of this material does not rise to the level of formal “collections,” it tends to be overshadowed, and consequently its relevance to contemporary audiences overlooked. A more sustained study of such dossiers would almost certainly flesh out the outlines of clerical resistance sketched out here.

As for the beleaguered archbishop of Reims and the canons of Noyon and Cambrai, I cannot help but think they sincerely believed in the strength and legitimacy of their legal arguments. Marriage was an honorable estate, so argued the Tractatus and canons of Noyon and Cambrai. No less honorable was the historically privileged relationship with Rome asserted by Reims’s metropolitans. In defending his jurisdictional prerogatives, Manasses could claim with some justification to be following, as Otto Meyer long ago observed, in the distinguished footsteps of his predecessor, Hincmar. The authority of the law upon which the canons’ and archbishop’s claims rested was, they believed, both established and self-evident. Yet, any solace they may have taken in the validity of their claims proved brittle. A generation later, in the embittered and archly ironic Gesta pontificum Cameracensium (Deeds of the Pontiffs of Cambrai), an anonymous canon of Cambrai authored the Vita Galcheri, a verse narrative of the ill-starred bishop Galcherus of Cambrai (1093–1095). Describing Galcherus’s deposition by Urban II at the council of Clermont in 1095, the Vita’s author has the pope proclaim: “Let the canons cease.” For, the text continues, “all of their [the canons’] laws depend upon [papal] authority.”Footnote 88 This ironic line captures a harsh reality: papal authority, or papal whim, abrogated “the law,” whose waxen nose could only be bent so far in defense of long-held practices and prerogatives. Manasses and the married canons were destined to lose their respective battles. The fragmented dossier now found in Vat. Reg. lat. MSS 566 and 863 nevertheless offers testimony of their contribution to a coordinated, determined—if fleeting—resistance.

Edition

For the edition of the Apologia’s first recension below, I have relied on W, with reference to V and the editions of Demouy (D) and Mabillon’s Museum Italicum (M). Generally speaking, M and D follow V. Occasionally, though, they depart from it, and where Mabillon (M) veered from V, Demouy (D) typically follows. The copies V 1 and V 2 were made from V, and have not been collated here, although I referred to V 1 (Duchesne’s copy) in preparing the edition. It must be said at the outset that neither Wouters (W) nor the anonymous scribe of V were always careful copyists. In some places I have followed the reading offered by V where it made more sense than that provided by W; this is indicated in the apparatus and wherever bracketed words or punctuation appear in the text. I have also included here the added text of the Apologia’s second recension found in VDM and the later copies. The point at which this occurs is indicated with an asterisk (*).

Original: lost

Manuscript copies

First recension:

W = Wolfenbüttel, Herzog-August-Bibliothek MS 27.9. Aug. fol., fols. 469v–473v; sixteenth century (after 1554).

Second recension:

V = Vatican City, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana, Reg. lat. MS 566, fols. 45r–47v, and Reg. lat. MS 863, fol. 62r; early twelfth century.

V 1 = Paris, BnF, Collection Duchesne, vol. 22, fols. 194r–198r; early seventeenth century.

V 2 = Vatican City, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. Lat. MS 9867, fols. 218r–225r; eighteenth century.

Editions:

M = Museum Italicum, seu Collectio veterum scriptorum ex bibliothecis Italicis, Tomus 1: Pars altera, ed. Jean Mabillon and Michel Germain (Paris, 1687), 119–27.

D = Patrick Demouy, “Actes des archevêques de Reims d’Arnoul à Renaud II (997–1139),” 2 vols. (Ph.D. diss., Université de Nancy II, 1982), 2.1:187–97 (no. 60).

Storia critico-cronologica diplomatica del patriarca S. Brunone e del suo ordine Cartusiano, ed. Benedetto Tromby, 10 vols. (Naples, 1773–1779), 1:xviii–xxii (appendix).

Recueil des historiens des Gaules et de la France, ed. Michel-Jean-Joseph Brial et al., 24 vols. (Paris, 1738–1904), 14:781–86.

[Apologia Manassae archiepiscopi Remensis]

(fol. 469v) Domino Hugoni diensi episcopo, Manasses remorum archiepiscopus salutem in domino.Footnote 89 Monuistis me Lugduni ad concilium vobis occurrere; ad quod quare non veniam dignum duxi litteris vobis et omni concilio designare,Footnote 90 ne quis forte vel in secreto vel in publico sit qui nos pro hac causa merito possit (fol. 470r) inculpare. Et hocFootnote 91 non solum per omnes fere gallias, verum etFootnote 92 Italiae etFootnote 93 Romae notum estFootnote 94 qualiter ante hoc biennium in eadem provincia a vobis et aliis quibusdam in nos violenter res gesta est ac iniuste,Footnote 95 et ego vim etFootnote 96 praeiudicium passus Romam processi, ibique super hoc Romanum et apostolicum iudicium appellavi. Quia vero vos aberatis iussu dominiFootnote 97 apostolici in ipsa regione remansi, et adventum vestrum per xiFootnote 98 fere hebdomadas expectavi. Cumque non veniretis, tandem in presentia dominiFootnote 99 apostolici et in concilio generali inter nos et eos qui ibi loco vestro utpote a vobis directi aderant[,] altercatio de vobisFootnote 100 habita est et ex eorum accusatione ac nostra defensione, quodFootnote 101 passi eramus temere etFootnote 102 violenter actum esse et constare non debere iudicatum atque correctum est. Tum ego dominoFootnote 103 apostolico renunciavi audientibus cunctisFootnote 104 quia non me ultra in iudiciis ecclesiasticis si nollemFootnote 105 committerem manibus vestris, et quia vobis ultra subici non deberem iureFootnote 106 congruam in ipsius romani conventus audientia reddidi rationem. Ipso autem dominoFootnote 107 apostolico subsequentur interrogante[,] cuius potius in conciliis infra gallias iudicium vellem subire[,] meque in hoc protinus abbatem cluniacensemFootnote 108 eligente. Statutum est ut in conciliis gallicanis sicut iam diximus, aliorum causas censura vestra tractaret, porro abbas cluniacensis de nobis iudicaret. Deinde etFootnote 109 instititFootnote 110 idem dominusFootnote 111 apostolicus ut sibi huiusmodi facerem sponsionem, quiaFootnote 112 si ad concilium in partibus galliarum vel nuntio vel litteris sedis apostolicae vocatus essem[,] non omitteremFootnote 113 venire nisi canonica excusatione impeditusFootnote 114 essem, sed hoc non addidit ut si contra mandaretur a profectione desisterem. Qua propter cum nuper concilium apud Trecas monitum est a vobisFootnote 115 in qua monitione nomen cluniacensis abbatisFootnote 116 pariter insertum est, ego illuc incunctanter cum abbatibus meis et clericis et beneficarisFootnote 117 ecclesiae meae processi, quia ut superius iamFootnote 118 dixi nullam a domno apostolico in iam dicta sponsione contra mandationis mentionem audivi, et quia cluniacensem abbatem qui me iudicare debeatFootnote 119 affuturum accepi[,] et quia in ipsa contra mandationeFootnote 120 a vobis facta nec impedimentum ullum quo fieri non posset vos habere comperi, nec litter[a]s ut par erat in conciliis contra mandantisFootnote 121 a vestraFootnote 122 parte vel predicti abbatis habui. Unde illuc ut dictum est proficiscens quamvis vos non veniretis, ego (fol. 470v) tamen ipsius partemFootnote 123 concilii quae ad me attinebat implevi, et me a predicta sponsione secundum propositae rationis consequentiam liberavi. Ad istud vero lugdunense concilium ideo non venimus quia non unam sed plures excusationes canonicas cur venire non debeamus habemus. Primo quiaFootnote 124 in eius monitione nullam vel mentionem domni abbatis cluniacensis, qui nos iussu domni apostolici iudicare debeat accepi.Footnote 125 DeindeFootnote 126 quia in eis galliarum partibusFootnote 127 non geritur, ubi eius iudicium subireFootnote 128 iussi sumus[,] sicut in consequentibusFootnote 129 explanabimus. Tertio quiaFootnote 130 regio ipsa inter nos et Lugdunum adiacensFootnote 131 ex captione comitis NivernensisFootnote 132 et episcopi autisiodorensis et militum eorum adeo bellorum tempestate turbatur, ut nulli ex regno francorum liber transitus per eamFootnote 133 concedatur. Cum enim ipsi propter dominumFootnote 134 nostrum regem francorumFootnote 135 capti et trusi ergastulo teneantur, nos procul dubioFootnote 136 similiter propter regem[,] eo quod regis episcopi sumus[,] ab hominibus ipsius provinciae captioneFootnote 137 et ergastulo traderemur. Et ideo secundum legem iustinianam in secundo libro codicum legitimam excusationem habemus, quoniamFootnote 138 salutis periculum et corporis cruciatum in eundo pertimescimus.Footnote 139 Preterea cum hoc concilium in eadem provincia [et] ab eisdem ipsis celebrari noscamus[,] ubi et a quibus in altero concilio violenter et inhumane tractati sumus[,] et tam iniuste ut Romae totum illud destructum videremusFootnote 140 pro qua re etFootnote 141 in generali et romano concilio de horumFootnote 142 manibus ablati sumus, consequenter nec nos deinceps iudicium eorum habemus subire[,] nec ipsi super nos manum habent ponere.Footnote 143 Super haec omnia sacris auctoritatibus edocemur, quia si vim temerariae multitudinis metuimus, locum eligere debemusFootnote 144 nobis proximum, in quo non sit difficile testes producere et causam finire. Vim temerariae multitudinis illos vocamus, a quibusFootnote 145 in eadem provincia, sed in altero concilio tale quid in nos violenter ac temereFootnote 146 actum est, quod Romae non firmatum sed potius infirmatum est. Locus ipse profecto nec nobisFootnote 147 proximus nec testibus producendis facilis est quia itinere xv dierum fereFootnote 148 a nobis abest. Quia vero de hoc uno concilio infra tres hebdomadasFootnote 149 duas monitionesFootnote 150 sibi valde dissimilesFootnote 151 a vobis accepimus, primo de prima, deinde de secunda tractabimus. In prima dixistis ut accusatoribus nostris scilicet Manasse et sociis suisFootnote 152 responsuri ad concilium veniremus, et ego vobis dico, quia ego et Manasses pro omnibus sociis suis concordiam fecimus (fol. 471r) exceptis duobus, quorum unus scilicet Bruno nec noster clericus nec noster natus aut renatus est, sed Sancti CunibertiFootnote 153 coloniensis in regno theutonicorum positi canonicus est, cuiusFootnote 154 societatem non magnopere affectamus utpote de cuius vita et libertate penitus ignoramus, et quia quando apud nos fuit multis beneficiis in eum collatis a nobis,Footnote 155 male et nequiter ab eoFootnote 156 tractacti sumus. Alter vero id est Pontius in Romano concilio nobis presentibus est falsatus, et ideo nec uni nec alteri in ecclesiastico iudicio respondere aut volumus aut debemus. Dixistis vos etiamFootnote 157 in Lugduno loci aptitudinem elegisse[,] eo quod predicti clerici non ausi venire Trecas, illic non timerent adesse. Nos e contra dicimus, quia nos multomagisFootnote 158 timemus Lugdunum procedere quam illi Trecas venire, quia quanto illis maiores et ditiores videmur, tanto et citius capi et gravius pro ampliori redemptioneFootnote 159 distringi a tyranno quolibet quaereremur. Iam veroFootnote 160 ex abundantiaFootnote 161 iniquitatis in consuetudinem versum esse videmus[,] ut de die in diem episcopos capi et trudi ergastulo doleamus, sicut in eo de quo supra diximus episcopoFootnote 162 autisiodorensi cernitur factum, sicut etFootnote 163 in episcopo leodiensi quem nuper in vigilia natalis domini novimus captum, sicut vos ipsi nostis domnum apostolicum in nocte natalis domini in ipsa missae celebratione nondum peracta ab altari perFootnote 164 summum scelus abstractum.Footnote 165 Unde quia sicut vulgo dicitur, levius ex aliorum quam ex nostris periculis castigamur, satis apparet nullam nobis apud Lugdunum, loci esse aptitudinem et nullam nobis esse sine periculo ad illumFootnote 166 processionem, et ideo secundum prememoratae Justiniane legis sententiamFootnote 167 et iuxta perpetratam olim in nosFootnote 168 temeritatem in ea provincia[,]Footnote 169 legitimam super hoc habere excusationem. De secunda monitione subsequenteFootnote 170 hoc dicimus quia dixistis ut si accusatores deessent, ad concilium venirem, paratus cum sex episcopisFootnote 171 quorum vita non notetur infamia me expurgare. Et nos econtra respondemus, quia si accusatoresFootnote 172 desunt, nos ex hoc cuiquam respondereFootnote 173 non debemus. SiFootnote 174 vero adsunt[,] non nisi illis qui se presentialiter vel audisse vel vidisseFootnote 175 affirment nos respondere debere probamus. Quod et in sacris autoritatibusFootnote 176 est statutum et in saepedicto romano concilio nobisFootnote 177 a domno apostolico sub hac eadem rationeFootnote 178 laudatum est. Cuius rei etaim testes idoneos qui interfuerunt habemus et per eos de rationeFootnote 179 (fol. 471v) valemus, quamvisFootnote 180 nullam a predicto Manasse et sociis eius speremus accusationem, eo quod ipsi nisi forte pro huius concilii [occasione] ad vomitum redeunt, nobiscum fecerunt concordiae compositionem, exceptis duobus ut dixi, Brunone et Pontio [,] quibus iuxta predictamFootnote 181 rationem nec respondere volo nec debeo.Footnote 182 Et si aliqui ex illisFootnote 183 quos concordare per Manasse legationem diximus, illuc rupta pace profecti sunt[,] et contra nosFootnote 184 quippiam dicere volunt, recipiendum non est quia tunc temporeFootnote 185 nec familiares mei erant nec canonici[,] ita ut de vita mea testimonium ferre possent. Ceterum quod me paratum cum sex episcopis ire monuistis in tanta nobis hoc temporis angustia constringitis,Footnote 186 ut soli xx dies numerenturFootnote 187 ab illo die quo mihi delataeFootnote 188 sunt littere vestrae usque ad illum quoFootnote 189 si proficisceremur debeamus movere. In sacris vero autoritatibusFootnote 190 fixum habetur, quod si quis inferioris ordinis clericus nedum episcopus de aliquo crimine pulsatur, aut annum integrum aut dimidium aut simul integrum et dimidium induciarum habere debeat quoFootnote 191 sibi in tanto spacio providere autFootnote 192 prospicereFootnote 193 valeat. Vos autemFootnote 194 vel maiori vel minori induciarum spatio intermisso, hoc a nobis exigitis etFootnote 195 in xx dierum tantum spatio,Footnote 196 cum nostri episcopatus non sicut circa Romam vel in quibusdam regionibus intra septimum vel decimum miliarium coarctentur, sed plures ex eis xl et l vel etiam lxFootnote 197 miliariis et eo amplius ab invicem separentur. Ut ergo de anno vel dimidio taceatur, quo quibuslibet pulsatis crimine legitimae induciae ex sacra autoritateFootnote 198 donantur[,] quomodo in xxFootnote 199 diebus sex episcopi patriae nostrae et maxime qui non notentur infamia valeant colligi cum in totidem diebus de uno ad alium vix queat ambulari[?] Iam vero de ipsis epicopis quorum vita non notetur infamia quid dicemus, cum [etiam] ipsum dominum nostrum Jesum Christum voracem et potatorem vini, et publicanorumFootnote 200 et peccatorum amicum et demonium habentem appellatum fuisse noverimus[?] Quis unquamFootnote 201 tam sanctus fuit tamque perfectus qui non ab aliquo maledicoFootnote 202 alicuius infamiae nota appetitus sit?Footnote 203 Non possumus animadvertere quo pacto huius sanctitatis sex episcopos valeamus colligereFootnote 204 nisi sanctos patres Remigium, Martinum, Iulianum, Germanum, Hilarium, Dionisium contingat a sepulchris resurgere.Footnote 205 Si iusta [monitio]Footnote 206 esset, et plane sex tantumFootnote 207 episcopos quales apud nos habemus adhiberi exposceret, omninoFootnote 208 eos in tam breviFootnote 209 tempore congregari (fol. 472r) impossibileFootnote 210 esset. Et quid dicemus de illa impossibilitate, qua non nisi ab omni nota infamiae alienos iubenturFootnote 211 exquirere[?] Pro certo dicimus et firmamus quiaFootnote 212 haec monitio vestra, quae talia nobis iniungit, eadem pro sui impossibilitate canonicam excusationem nobis adducit. Non enim impossibilitatem tantum predicta monitio sed etiam quiddam stuppendum nobis ingerit, dum primo si accusatores desint, deinde sex episcopos tum qui non notentur infamia, ut exhibeamus imponit. Si enim absentibus accusatoribus sex clericos solummodo adhibere querantur,Footnote 213 inauditum est.Footnote 214 Si sex episcopos mirabile dictu est. Si etFootnote 215 sex episcopos et tales qui non notentur infamia et sine excusatoribusFootnote 216 a nobis exposcatis sicut facitis, hoc a seculis auditum non est. Quod vero dicitis infamiam nostram Galliam Italiamque replesse et propter hocFootnote 217 cum sex episcopis qui non notentur infamia me ad purgandum paratum esse debere,Footnote 218 omnino dicimus quod accusatores quidem nostri et illi qui tam temere nosFootnote 219 tractaverunt, ipsi Galliam et Italiam infamia nobis iniuste imposita replere voluerunt.Footnote 220 Sed nos Romam pergendo et quod temere actum fuerat destruendo, Galliam et Italiam vacuavimus infamia,Footnote 221 et quidquid ab eis infamatum fuerat annullando penitus ne hoc infamia vel esset vel dici veraciter potuissetFootnote 222 domino iuvante effecimus. Quod inquam dicitis ut et siFootnote 223 accusatores desint me debeam cum tot et talibus et tam brevi spatio perquisitis testibus purgare,Footnote 224 quod ego siFootnote 225 infamia esset,Footnote 226 cum re vera non sit, hoc absentibus accusatoribus debeam agere? Nonne docemur in canonibus et decretis nullam causam criminalem inter episcopos et clericos sine legitimis accusatoribus debere diffiniri?Footnote 227 Quid fiet de illo decreto sancti papae et martyris Evaristi,Footnote 228 ut mala audita nullum moveant nec passim dicta absque certa probatione, quisquam credat unquam?Footnote 229 Quid quod dominus Judam furem sciebat,Footnote 230 et quia non est accusatus, ideo non est eiectus sed permansit in apostolatu[?] Ait etiam beatissimus Euticianus papaFootnote 231 de non commutandis sanctorum patrum autoritatibus,Footnote 232 Prohibemus ut nullae causae ab ecclesiasticis iudicibus audiantur quae legibus non continentur, vel quae prohibitae esse noscuntur. Footnote 233 Est et alia ratio excusationis, quaFootnote 234 etiam si iustum esset istud sex episcoporum testimonium in tam brevi spatio adhiberi, et hoc ab aliis archiepiscopis vel episcopis (fol. 472v) quereretis a me autemFootnote 235 querere non debeatis,Footnote 236 pro eo quod plures ex suffraganeis meisFootnote 237 episcopis tunc temporis vellent nollent interfuerunt [in illa]Footnote 238 violentia quae in nos tunc Romae gestaFootnote 239 fuit ut diximus infirmata. De quibus et si certum est quod nobis ad testimonium presto essent, si eos et ratio canonum adhiberi exposceret et temporis plenitudo ad congregandum sufficeret, tamen et vobis et multis disconveniens esse videturFootnote 240 eosdem nunc et socios hicFootnote 241 et testes adiungere, quos tunc vobiscum illicFootnote 242 quomodocumque contigitFootnote 243 interfuisse. Sed iam plusquamFootnote 244 satis de hisFootnote 245 pro tempore diximus, dignum est ut ad sponsionem quam domno apostolico supra nos fecisseFootnote 246 diximus redeamus. Ea fuit huiusmodi quod ego ad concilium in partibus galliarum vel nuncioFootnote 247 vel litteris sedis apostolicae vocatus venirem nisi canonica excusatione prepeditus essem, et quod in ipsis partibus concilia apostolica fieri non perturbar-[em].Footnote 248 Quod dictum est in partibus galliarum, nullus estimare debet de omni parte citra montes alpium esseFootnote 249 dictum. Hoc enim satis potestis conijcere quia ubi de non perturbandis conciliis in partibus galliarumFootnote 250 quesitum est non nisi de illis partibus in quibus vel iuvare vel nocere posseFootnote 251 dictum est. Ubi autem nos iuvare vel nocere posse creditisFootnote 252 nisi in regno franciae? Quid enim vel apud Lugdunum vel alibi extra francorum regnum perturbatio nostra posset, ubi nec regis nostri, nec nostra cognitio aut reverentia ulla viget[?] Quapropter si vultis, satis cognoscitis quod de illis galliarum partibus dictum est, ubi regnum francorumFootnote 253 situm est. Quod vero nos ad concilium venire nisi canonica excusatione prepeditos [pro]misimus,Footnote 254 porroFootnote 255 superius diximus quod ad hocFootnote 256 non unam sed plures excusationes canonicas haberemus[,] iam hocFootnote 257 quasi recapitulando probabimus. QuandoFootnote 258 quidem enim ipsum concil[ium] in ipsa provincia et ab ipsis geritur ubi et a quibusdam quond[am] in nos violenter etFootnote 259 temere res gesta est, sicut etiam romana aequitasFootnote 260 testata est, ne ad illud eamus canonica excusatio est. Quoniam locus ipse nec nobis proximus nec testibus producendis idoneus velFootnote 261 facilis est, canonica excusatio est. Quoniam idem locus propter bellorum tempestatesFootnote 262 sine periculo salutis et libertatis adiri non potest,Footnote 263 canonica excusatio est. Quoniam domnus abbas cluniacensis qui nos post domnum apostolicum iudicare debet abest, canonica excusatio est. Quoniam eosdemFootnote 264 episcopos etiamsi accusatores desint habereFootnote 265 precipimur[,] quod nusquam in sanctisFootnote 266 autoritatibusFootnote 267 invenitur, canonica excusatio [est]. Quoniam infra xxFootnote 268 dies sex episcopos congregare et nobiscum (fol. 473r) ducere iubemur[,] quod in tam brevi temporeFootnote 269 impossibile est, canonica excusatio est. Quoniam eos tales quorum vita non notetur infamia quo nihil impossibilius est adhibere monemur, canonica excusatio est.Footnote 270 Constat ergo si ad concilium LugdunenseFootnote 271 non venimus in nullo predictae sponsionisFootnote 272 prevaricatores existimus, dum tot canonicas excusationesFootnote 273 habemus. Ceterum scire vos volumus, quiaFootnote 274 si quis sophisticeFootnote 275 loquens aliqua ex his excusationibusFootnote 276 voluerit infirmare, noveritis pro certoFootnote 277 nos illas quae maioris autoritatisFootnote 278 sunt et infirmari non possunt etFootnote 279 admittimus et tenemus, quamvis apud vosFootnote 280 canonice excusaverimus nos, quasi vobis subiectionisFootnote 281 debitores simus, tamen evidenti ratione ostendere possumus quia etiamsi canonic[a]eFootnote 282 excusationes aliter nobis non adessent non tamen ad vestrum placitum proficisci ullatenus debemus.Footnote 283 Quod etiamFootnote 284 nobisFootnote 285 pace vestra dicere liceat, et si aliis nuntius sedis apostolicaeFootnote 286 estis, nobis tamen non estis, propter quod neque vos habetis nos ad concilium evocare, neque nos ad vocationem vestram si nolumus,Footnote 287 habemus venire. Quod etiamFootnote 288 subsequenti declarabitur ratione, postFootnote 289 diffinitam enim Romae placitiFootnote 290 nostri questionem audientibus et videntibus archiepiscopis et episcopis et clericis franciae, presentibus etiam clericis qui hic presentes habentur. Domnus papa laudavit ut vobis in nullo amplius si nollemFootnote 291 subiectus essem.Footnote 292 Sed domno abbatiFootnote 293 Cluniacensi per omnia subditus essem. Postea mihi precepit et etiam vellem nollem sibi spopondi, quatenusFootnote 294 si nuncio suo vocatus essem, nisi canonica praepeditus essem excusationeFootnote 295 pro hac causa ad concilium irem.Footnote 296 Et quoniam in nostra promissione de nuncio suo quasi indiffinite mentionem fecit et ad nostram vocationem faciendam vos non excipit,Footnote 297 quando prius quam promissio fieret prelationem nostram a vestraFootnote 298 subiectione removit,Footnote 299 putatis ad eandem vocationem faciendam vosFootnote 300 ea de causa inter alios nuntios debere computari. Quod non procedit.Footnote 301 Nam si nos ut supra dixi, priusquam promissio fieret, domnus papa a vestra subiectione removit, iterum vos admittere non potuit, quoniam si sic fieret profecto seipsum impugnaret, et quod audiente concilio laudavit iniusteFootnote 302 destrueret, et ut amplius loquar, iniuste quod absit iudicaret. Etenim in decretis pontificum legitur quod si aliquis legatus ut (fol. 473v) Zacharias et Rodoaldus[,]Footnote 303 ut Vitalis et Misenus super aliquem iniusteFootnote 304 iudicaverint,Footnote 305 praeiudicatus praeiudicantis amplius non debet subdi iudicio, et vocatioFootnote 306 qua domnus papa seipsum impugnet, qua falsitatis, temeritatis, et inconstantiae possit argui, possit etiam falso,Footnote 307 quod absit, iudicio notariFootnote 308 nec laudanda nec recipienda est. Et ideo quamdiu domnus abbas cluniacensis defuerit et quamdiu domnus papa ut vobis obediamFootnote 309 nec mihi loquendo nec litteris praecipiendo iusserit, et siFootnote 310 canonica excusatio sicut superius multis modis est ostensaFootnote 311 deficeret, tamen haec ratio sola sufficere deberet, et ut altius loquar, debetFootnote 312 sufficere tum pro reverentia summi pontificis, tum pro honore eius,Footnote 313 si eum diligitis. Nam scriptum est, Servus nec diligit nec reveretur dominum quem facitFootnote 314 contemptibilem in conspectu omnium. At vero quamvis ita persecutiFootnote 315 simusFootnote 316 quod vobisFootnote 317 causa observataeFootnote 318 veritatis concedendumFootnote 319 licet iuxta predictam rationem vobis respondere non debeamus, tamen proFootnote 320 reverentia domni papae* si loci oportunitas expeteret digno mei vestrique modo responsuri vobis obviam intrepide procederemus. Tandem ut hoc fine peroratum sit legationis vestrae preconia sic valeant ut iniustae(?) inundationes et verborum flumina Remensis ecclesiae dignitati et nostrae nec prosint si placet nec officiant. Valete ut nos valere contenditis.

[Alternate ending of the letter in Vat. Reg. lat. MSS 566 and 863]

*aliam vobis adhucFootnote 321 rationem ostendere nobis visum est. Etenim ne forte iudicia ecclesiastica diffugere videamur, ne forte pertinaces esse, et conciliaFootnote 322 apostolica perturbare velle putemur, sciatis quorum non pertinaces in hoc existimus, nonFootnote 323 concilia fieri perturbamus,Footnote 324 sed potius ut in franciam concilium celebrare nobis cooperantibus veniatis offerimus, et locum nobis proximum sicut a sacra auctoritate iubemur eligimus. Offerimus inquamFootnote 325 hoc ex parte nostra et regis nostri, vel per .xla.Footnote 326 vel post pascha in franciam veniatis causa concilii, et ego et coepiscopi nostri vobis occurrentes sanum et incolumen vos deducemus in domibus et cameris nostris [et]Footnote 327 cum honore legatis sedis apostolicae congruente suscipiemus, et cum omni habundantiaFootnote 328 procurabimus. Locum nobis proximum eligimus si vultis apud nos remis, si vultis suessionis, vel compendii, vel silvanectis, et in quocumque horum vobis videbitur concilium vosFootnote 329 tenere, rege quoque nostro cooperante iuvabimus,Footnote 330 et quod vobis debebimus facere faciemus. Ecce coram isto concilio cum caritate et humilitate vos precamur, et si attendere vultis consilium utile vobis damus, ut libram moderaminis erga nos teneatis, nec modum ac rationem excedere affectantes, pondus quod nec nos nec patres nostri portare consuevimus, super nos imponere appetatis. Melius est ut mitius agendo et iusticiam non excedendo romanae ecclesiae commodum et honorem, per franciam adquiratis,Footnote 331 quam exasperando franciam eius iustitiam et subiectionem romanae ecclesiae impediatis. Quod si in pertinatia vestra sicuti domno pape hisdemFootnote 332 verbis mandavimus permanere disposueritis, et pro sola voluntate vestra nos vel suspendere vel excommunicare volueritis, ostensa est nobis via quam sequamur, apposita forma cui inprimamur.Footnote 333 Sequar verba beati GREGORII, qui dicit, Sepe Footnote 334 in ligandis ac solvendis subditis suae voluntatis motus, non autem causarum merita sequitur pastor. Unde fit ut et ipsa ligandi ac solvendi potestate se privet, qui hanc non pro subditorum meritis sed pro suae voluntatis motibus exercet. Footnote 335 Unde per prophetam dicitur, Mortificabant animas quae non moriuntur, et vivificabant animas quae non vivunt. Footnote 336 Ait etiam beatus AUGUSTINUS, in libro de verbis domini, Vide utrum iuste an iniuste obliges fratrem tuum, quoniam iniusta vincula disrumpit iustitia. Footnote 337 Asseram etiam quod si me excommunicaveritis, deerit privilegium petri et domni pape, id est, potestas ligandi etFootnote 338 solvendi. Unde leo magnus in sermone de anniversario suo sic dicit,Footnote 339 Manet petri privilegium ubicumque ex eius aequitate fertur iudicium. Footnote 340 Ex quibus verbis aperte colligitur, quia non manet petri privilegium, ubicumque ex eius aequitate non fertur iudicium.