Introduction

There is a seeming contradiction in the literature on electoral authoritarianism. One set of researchers argues that the holding of multiparty elections stabilises authoritarian regimes, whereas others see it as a threat. Before getting into the details of this debate in the next section, we note that both cannot be true unless their impact is mediated by some other factor. This article argues that the ability of authoritarian regimes to effectively institutionalise electoral uncertainty will determine their impact on survival.

We examine the ability of authoritarian regimes to survive regular reiterated elections. We stress ‘reiteration’ because it addresses an under‐appreciated facet of authoritarian development – how low levels of incumbent uncertainty over re‐election are institutionalised in a multiparty environment. Specifically, our main contribution is to focus on how incumbents overcome the risks of losing multiparty elections and then demonstrate its centrality to understanding the durability of electoral authoritarianism. We do so by placing electoral sequencing and competitiveness at the centre of our conceptualisation of how authoritarian regimes cope with the uncertainty of electoral outcomes.

While multiparty elections expose incumbents to a risk of removal from power at regularised intervals, we theorise that the risks are not uniform over time. This is because, with reiteration, multiparty elections can increase ruler legitimacy with both the public and within the regime coalition, as well as demonstrate regime strength. Thus, while we argue that democratic emulation strategies are dangerous for authoritarian rulers, especially at the onset, overcoming that initial risk is essential to building long‐term stability.

We next discuss the contending literatures on electoral authoritarianism and present our theory of institutionalisation. We then test the impact of reiterated elections on regime outcomes, taking into account their degree of competitiveness. Using a sample of 262 authoritarian regimes from 1946 to 2010, we find differing effects for multiparty elections held under hegemonic and competitive conditions. In hegemonic electoral authoritarian regimes, the institutionalisation of elections may enhance survival, but this finding is not robust to various model specifications. In contrast, in competitive electoral authoritarian regimes, the first three elections substantially increase the hazard of failure and democratisation; thereafter the risk diminishes. The fact that only a small number of authoritarian regimes survive as competitive beyond the first few elections suggests that autocrats rarely benefit from the institutionalisation of high levels of electoral competition. We show that party competition is critical to whether institutionalising elections is a risky or effective strategy, thus finding some truth in both literatures by clarifying how and when democratic emulation is (de)stabilising.

The debate over democratic emulation

Beginning in the 1970s and with growing intensity following the Cold War, authoritarian regimes have faced two kinds of pressure to democratise: internal pressures originating from domestic grievances, and external pressures based on international standards.Footnote 1 Some regimes quickly transformed into electoral democracies, but many deflected the impetus by only emulating the electoral trappings of democracy. Today, electoral autocracy has become the modal type of dictatorship in the world (Lührmann & Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019).

In contrast to the showcase elections commonly staged by dictators in the past (Hermet et al. Reference Hermet, Rose and Rouquié1978), the ramifications of elections under electoral authoritarianism are subject to robust debate. The ‘stabilisation hypothesis’ argues that authoritarian incumbents deflect internal and external pressures by liberalising without fully submitting to the uncertainty of democracy (Levitsky & Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010; Schedler Reference Schedler2013). One set of theories is predicated on the cooptation of the political opposition or the voting public. For Gandhi and Przeworski (Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2007: 1280) the existence of ‘nominally democratic’ partisan legislatures expands the social support for dictatorship and diffuses opposition through patronage and policy concessions. Lust‐Okar (Reference Lust‐Okar and Lindberg2009) suggests that elections can forge a ‘competitive clientelism’ keeping opposition fragmented. Greene (Reference Greene2010) shows how dominant parties can use patronage to win elections. In contrast, another set of theories argue that elections and authoritarian legislatures serve to enhance intra‐elite loyalty and coherence, and cement ‘credible commitments’ about the division of resources (Magaloni Reference Magaloni2008; Svolik Reference Svolik2012; Boix & Svolik Reference Boix and Svolik2013; Wright & Escribà‐Folch Reference Wright and Escribà‐Folch2012).

Conversely, many studies demonstrate the destabilising potential of multiparty elections on authoritarian regimes. The colour revolutions inspired a wide‐ranging literature focused on how particular oppositional tactics (e.g., poll monitoring, civil society mobilisation and unified oppositional electoral coalitions) promote liberalisation and even democratisation (Howard & Roessler Reference Howard and Roessler2006; Beissinger Reference Beissinger2007; Bunce & Wolchik Reference Bunce and Wolchik2011; McFaul Reference McFaul2002). Others such as Tucker (Reference Tucker2007) and Knutsen et al. (Reference Knutsen, Nygård and Wig2017) also observe that the opposition is more likely to resolve collective action problems around elections and this increases the probability of regime change. While the latter address the same ostensible paradox in the literature as we do, their approach focuses on when regime‐challenging collective action is more likely to take place (i.e., just before or after elections rather than between them) – not on the process of authoritarian institutionalisation.

The theory of the democratising power of elections (Di Palma Reference Di Palma1990; Lindberg Reference Lindberg2006) argues that the introduction and repetition of multiparty elections leads to improvements in democratic quality via social learning. Lindberg (Reference Lindberg2006, Reference Lindberg2009) presents consistent evidence in Africa. However, tests in other regions, including Latin America, the Middle East and postcommunist Eurasia suggest that this could be a case of African exceptionalism (McCoy & Hartlyn Reference McCoy, Hartlyn and Lindberg2009; Lust‐Okar Reference Lust‐Okar and Lindberg2009; Kaya & Bernhard Reference Kaya and Bernhard2013). Morse (Reference Morse2017) even challenges whether the change in Africa is durable because of the embedded clientelism associated with strong presidentialism.

In global tests, Teorell and Hadenius (Reference Teorell, Hadenius and Lindberg2009) find support for the democratisation‐by‐elections theory, but the magnitude is quite small. Brownlee (Reference Brownlee2007: 31) finds that electoral authoritarian regimes are not more prone to breakdown, but when they do fail, electoral authoritarian regimes are more likely to democratise (Brownlee Reference Brownlee2009). In a study spanning the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Miller (Reference Miller2015) finds that higher levels of electoral competition have a robust impact on both democratic transition and the subsequent survival of democracy. Knutsen and Nygård (Reference Knutsen and Nygård2015) show that ‘semi‐democratic’ regimes are more likely to perish than democracies or autocracies, even when controlling for past instability. Edgell et al. (Reference Edgell, Mechkova, Altman, Bernhard and Lindberg2017) look at the general impact of competitive multiparty elections on democratic quality in the period 1900–2010 and find a democratising effect for the sample as a whole, but most sharply during the third wave in 1974–2010 and in certain regions.

Therefore, while electoral authoritarianism has become widespread, there is still no consensus on how multiparty elections affect the durability of authoritarian regimes. In the next section we outline our theory of the authoritarian institutionalisation of electoral uncertainty as a way to make sense of these conflicting claims.

The uncertainty problem and the authoritarian institutionalisation of multiparty elections

The innovation of electoral authoritarianism lies in its ability to simulate democratic electoral procedures while reducing (though not fully eliminating) uncertainty about outcomes (Schedler Reference Schedler and Lindberg2009). Incumbents do this by creating ‘an uneven playing field’ (Levitsky & Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010: 8) using a ‘menu of manipulation’ (Schedler Reference Schedler2002). Electoral authoritarian regimes only reduce uncertainty; they never fully eliminate it. Yet, given the manifold uncertainties inherent in any dictatorship (Svolik Reference Svolik2012), it is not surprising that incumbent dictators are willing to experiment with elections given the potential benefits.

To the extent that elections are perceived as reasonably fair, authoritarian incumbents can enhance legitimacy domestically and internationally. But fair elections risk increasing competitiveness and thereby incumbents’ hold on power. Yet, if they engage in too much repression or procedural manipulation, they risk alienating supporters (Schedler Reference Schedler and Lindberg2009). Thus, the degree to which elections are competitive enhances their legitimising potential but at the same time increases their riskiness. This trade‐off illustrates the potential benefits and risks that electoral authoritarian regimes incur. If successful, this yields what Przeworski (Reference Przeworski1991: 61) calls a ‘broadened dictatorship’. This differs from democracy, under which elections are not mechanisms to minimise uncertainty, but the very embodiment of uncertainty over who rules.

The successful institutionalisation of an electoral authoritarian regime begins with a liberalisation fraught with the same uncertainty for incumbents described in classic discussions of democratic transition (e.g., O'Donnell & Schmitter Reference O'Donnell, Schmitter, O'Donnell, Schmitter and Whitehead1986; Przeworski Reference Przeworski1991), and proceeds to multiparty electoral competition. The ideal result for the incumbent is a broadened and stable dictatorship, but should a democratic opposition effectively mobilise, liberalisation can lead to democratic transition or the replacement of the extant incumbent by a more hardline faction that rejects liberalisation. Herein lays the root of the debate over whether democratic emulation undermines or stabilises authoritarian rule. Stabilisation entails navigating a period of high uncertainty and potential failure in the hope of reducing future uncertainty.

Given an opening, the media, judiciary and civil society as well as political opposition can mobilise and push for greater change. The opposition may well learn to contest elections more effectively, leverage international support and/or use contentious politics to dislodge the incumbent. Depending on the nature and ingenuity of the opposition, this can lead to democratisation. Such democratisations are not necessarily fatal for the authoritarian incumbent or ruling party if they can adapt to democratic politics. They may relaunch themselves as democrats with the hope of staying in power, such as Jerry J. Rawlings in Ghana (Morrison Reference Morrison2004) or Mathieu Kérékou in Benin (Gisselquist Reference Gisselquist2008), or they may remain competitive as in the case of several communist successor parties (Grzymala‐Busse Reference Grzymala‐Busse2002).

In many cases, however, the fate for the incumbent is harsh, as was the case of Slobodan Milošević whose rule was short‐circuited by an attempt to manipulate the elections in Serbia/Yugoslavia in 2000. Milošević had been twice elected President in relatively free elections. His rule was marked by destructive, costly wars with other Yugoslav successor states and harsh domestic repression, including disappearance of opposition leaders and censorship, to remain in power. The unpopular nature of his rule led to increased civil society activity and cooperation between opposition parties, who presented a united front in the electoral campaign of 2000. When Milošević and his supporters in the Federal Election Commission inflated his vote totals to deny his opponent, Vojislav Koštunica, a first‐round majority victory, strikes and a campaign of peaceful protest compelled Milošević to resign (Bunce & Wolchik Reference Bunce and Wolchik2011: Chapter 4). The menu of manipulation failed Milošević at this stage, leading to democratisation.

In contrast, electoral openings can lead to the institutionalisation of stable electoral authoritarian regimes. This is well illustrated by the liberalisation of Russia following the failure of the Soviet Union. It emerges in our sample as a personalistic regime from 1993 to 2010. In 1996, incumbent Boris Yeltsin's second‐round victory over Communist Party leader Gennady Zyganov had all the hallmarks of low‐level manipulation without the commission of outright fraud, including the overwhelming pro‐Yeltsin bias of the state media and oligarchic‐controlled outlets, as well as campaign spending that exceeded legal limits. An ailing Yeltsin stepped down in favour of his prime minister, Vladimir Putin, who then used his popularity from the pacification of a rebellion in Chechnya after a series of suspicious bombings in Russia attributed to Chechens, and the existing state media advantage to secure election in 2000. In all subsequent elections, Putin (or his 2008 proxy due to term limits, Dmitry Medvedev) have handily defeated multiple opponents, while exercising strong control over the media, increasingly restricting the space available to Russian civil society and tying the country's main resource‐extractive economic interests to the regime through a system of presidential patrimonialism. They have effectively used these resources and the legitimising power of elections to create strong support for the president and the system (Fish Reference Fish2005; Hale Reference Hale2015; Greene & Robertson Reference Greene and Robertson2019).

Liberalisation can also lead to authoritarian replacement. Facing an increasing risk of losing power, elements within the ruling coalition sometimes defect and close down political reform or remove an unpopular leader. The incumbent can be replaced either by a conventional or electoral authoritarian successor. The former occurred in Haiti when General Henri Namphy overthrew Leslie Manigat, the winner of the presidential elections in 1988, after the new president tried to remove the general from the command of the army (Laguerre Reference Laguerre1993: chapter 8). The latter occurred in Georgia in 1992 when Edward Shevarnadze was drafted to replace Zviad Gamsakhurdia as president (Bunce & Wolchik Reference Bunce and Wolchik2011: Chapter 6).

We believe that electoral openings follow no inevitable a priori logic and lead to no preordained end. In this we agree with the concerns raised over the teleological bias in some accounts of liberalisation (Carothers Reference Carothers2002). Electoral openings are fraught with contingency. Will failing authoritarian regimes open, seeing no alternative, or will they resort to repression? And why do some stable authoritarian regimes convoke multiparty elections and subject themselves to higher levels of uncertainty? Is it because they stand a good chance of winning elections precisely because their rule is not under threat? Those who claim that the act of electoral opening is itself a sign of weakness or strength forget that even a competent dictatorship operates on only partially reliable information and its antecedent expectations often prove flawed (Kamiński Reference Kamiński1999; Magaloni Reference Magaloni2006: 236),Footnote 2 making it hard to argue that the ultimate outcome is endogenous. Furthermore, if the decision to open is a diffusion or external pressure effect, then it is effectively an exogenous shock (Levitsky & Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010: 16–20). For now, we put endogeneity questions aside, but we will return to them later (via a control function model that confirms our main findings).

Ultimately, outcomes of electoral openings are a product of struggles between incumbents seeking to attract new support and shore up their rule, opponents leveraging expanded political space to challenge for power, and hardliners believing their interests are threatened by change. The uncertainty in this process has a temporal component. Our expectation is that the first few elections after the opening are riskier and more likely to lead to regime change, but that such odds will diminish with successive incumbent electoral successes. If the ruling elite can strike the right balance of perceived fairness, repression and cooptation to weather this early phase, the level of risk associated with each reiteration of elections should diminish given the legitimacy and demonstration effects of electoral victories.

This ability of autocrats to defeat their opponents and accrue the legitimacy benefits of competition is the essence of the institutionalisation of stable electoral authoritarianism. If an increasing number of citizens bandwagon on the winning side, incumbents should again gain more latitude to use state institutions for their purposes, distribute personal and club goods selectively, and restrict non‐state actors when necessary. Under those circumstances, the opposition becomes less dangerous. In realising that they cannot displace the incumbents, they may settle for limited concessions such as policy concessions, payoffs and the perquisites of sharing power (Weghorst Reference Weghorst2015). Such institutionalisation should also help to reinforce credible commitments within the authoritarian elite through more formal public representation of their interests, and thus prevent internal dissent.

This theoretical understanding leads to two hypotheses about electoral openings by authoritarian regimes. The first, the ‘double‐edged sword hypothesis’, is based on our understanding of the uncertainty in the movement from closed authoritarianism through electoral opening to electoral authoritarianism or its failure. We expect authoritarian regimes to be most vulnerable early on in an electoral sequence (H1a), whereas after a certain inflection point, the reiteration of authoritarian elections should enhance their prospects for survival (H1b). The second, the ‘competition hypothesis’, grows out of the theory that the balance of power between domestic political actors is essential to understanding the prospects for the trade‐off between stabilisation of authoritarianism, democratic transition and authoritarian replacement as potential outcomes. We expect an enhanced prospect for democratisation when the opposition is able to maintain its electoral competitiveness across repeated elections (H2). The strength of the opposition as well as the mobilisation of pro‐democratic actors in the media, judiciary, civil society and other bodies are critical in this process. Electoral competitiveness is thus not something which the regime sets when it decides to open, but a contingent product of struggle. The outcome of the struggle will determine whether an electoral authoritarian regime is competitive or hegemonic in nature. An incumbent should be expected to prefer hegemonic party control after an opening. Competitive elections are thus an indicator of effective opposition and pro‐democratic pressures – not an authoritarian policy choice. We explicitly model differences between competitive and hegemonic multiparty electoral sequences as a critical factor in understanding the outcome of authoritarian electoral openings.

Empirical strategy

To test the two hypotheses, we construct a categorical dependent variable measuring three (mutually‐exclusive) regime‐year outcomes: (0) authoritarian survival, (1) democratic transition and (2) authoritarian replacement based on the Autocratic Regimes dataset compiled by Geddes et al. (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014). Dichotomous coding schemes with ‘a single, continuous period of authoritarianism – or spell – can conceal multiple, consecutive autocratic regimes’ (Geddes et al. Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014: 316). Modeling failure as a binary outcome obscures the difference between failures that resulted in democratisation and those that produced a new authoritarian regime. Only a tripartite measure allows us to adjudicate between theories of stabilisation and democratisation as we have conceptualised it.

We treat democratic transition and authoritarian replacement as distinct, competing failure events using multinomial logistic regression models for discrete‐time event history analysis.Footnote 3 The estimation sample includes 262 regimes from 1946 to 2010, with 98 democratic transitions and 110 authoritarian replacements for a total of 208 failure events out of 4,232 country‐years.Footnote 4 Nearly 80 per cent of the authoritarian regimes in our sample fail during the observation period. The model calculates separate sets of coefficients for each predictor for each pair of outcomes. We report relative risk ratios expressing the predicted change in the odds of one outcome over another.Footnote 5 We incorporate a cubic polynomial of time and limit the sample to an authoritarian risk set (Carter & Signorino Reference Carter and Signorino2010). Because individual countries experience multiple regimes within the sample, we report country‐clustered standard errors and control for the number of previous regime changes.Footnote 6

This estimation strategy has two benefits over traditional duration models for competing risks. First, because reiterated elections are themselves a direct function of time, meaning that they typically come at regularly spaced time intervals, estimating the effects of elections on the duration to failure poses an endogeneity issue. Second, traditional competing risks models using proportional subhazards focus on the subdistribution of the event of interest while accounting for competing risks (Fine & Grey Reference Fine and Grey1999). This does not allow for a straightforward interpretation of the competing risks. The multinomial logit, by contrast, calculates separate coefficients for each type of event making it easy to interpret the effects of elections (and other explanatory variables) on the probability of survival, democratic transition and authoritarian replacement.

Measuring reiterated elections

We use the Varieties of Democracy (V‐Dem, v8) dataset to count the number of reiterated elections (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge2018a, Reference Coppedgeb).Footnote 7 Our sampling procedure means that our categorisation of electoral authoritarian regimes is somewhat more expansive than some other studies (Levitsky & Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010; Schedler Reference Schedler2013) by the inclusion of the handful of remaining monarchies in the world. This is in line with other large‐n studies on electoral authoritarianism (Miller Reference Miller2015; Knutsen et al. Reference Knutsen, Nygård and Wig2017; Brownlee Reference Brownlee2007, Reference Brownlee2009). We also differentiate these regimes on the basis of whether they hold multiparty and competitive legislative elections (e.g., Morocco and Jordan versus Saudi Arabia).Footnote 8

Where the executive is directly elected, we assume that executive elections will attract more attention and have greater repercussions for regime stability.Footnote 9 When executive and legislative elections are concurrent, the choice is inconsequential. We ignore midterm elections in presidential systems and by‐elections. For each country‐year, we count the number of previous such elections the regime has held without interruption.Footnote 10 An interruption in an electoral sequence occurs when there is a change in the type of electoral regime (i.e., a shift from single party to multiparty), an extralegal suspension of the elections and/or the extralegal dissolution or replacement of a sitting legislature or removal of an executive.Footnote 11

To account for the double‐edged sword hypothesis (H1a, H1b), we test for linear, quadratic and cubic functional forms. The linear estimation assumes a constant effect over elections, whereas the quadratic and cubic specifications allow us gauge changing levels of risk as elections become institutionalised. Through the reported specification checks (Table A1 in the Online Appendix), we find empirical evidence that there are important differences in the functional form for our sample of regimes contingent upon the nature of the elections being institutionalised. In the main models, we report the best fitting form.Footnote 12

To test the competition hypothesis (H2), we allow for differing effects depending on the nature of the elections being institutionalised. To do so, we classify elections within the V‐Dem dataset based on three criteria: (1) de facto inclusion of multiple political parties; (2) minimal suffrage in practice; and (3) minimal competitiveness in practice. The first criterion distinguishes single‐party elections from multiparty ones. In single‐party elections, opposition parties or all parties are barred from participating.Footnote 13 This includes non‐competitive elections, those in which multiple candidates participate as part of a single ruling party, as independents and/or via satellite parties controlled by the ruling party. This classification allows us to test contentions about the relative stability of institutionalised one‐party regimes when compared to other forms of dictatorship (Geddes Reference Geddes1999; Geddes et al. Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014). By contrast, multiparty elections include at least one real opposition party.Footnote 14 Comparisons between the effects of reiterated single‐party and multiparty elections generally test for whether enhanced party competition affects the prospects for democratisation.

Nevertheless, an extant literature shows that the quality of party competition varies not only based on the presence of opposition parties, but also the degree to which election outcomes are free from interference by the regime. Therefore, we utilise the final two criteria to differentiate sequences of hegemonic and competitive multiparty elections.Footnote 15 Hegemonic multiparty elections experience significant irregularities that affect the outcome of the election and/or do not allow at least 25 per cent of the adult population to vote.Footnote 16 Meanwhile, competitive multiparty elections allow for substantial competition, freedom of participation and at least 25 per cent suffrage for adult citizens. Significant irregularities may still occur, but there is not clear evidence that they directly affected the outcome.Footnote 17 To capture the institutionalisation of these different electoral regimes, we count reiterated elections (as outlined above) until a different type of election occurs (i.e., a change in the party, suffrage or competitiveness criteria) or there is a general interruption of elections, at which point, a new sequence begins at zero.

Control variables

We include a variety of control variables.Footnote 18 Both economic development and growth are consistently correlated with regime survival. There is a substantial debate over whether development promotes democratisation (Boix & Stokes Reference Boix and Stokes2003; Przeworski & Limongi Reference Przeworski and Limongi1997). We measure economic development as the natural log of real gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and economic performance as per capita GDP growth. Estimates of GDP and GDP growth are measured in constant 2011 US dollars and lagged by one year (Bolt et al. Reference Bolt, Inklaar, De Jong and Van Zanden2018).

The ability of regimes to ensure their survival via repression is a function of their state capacity (Hanson Reference Hanson2018; Van Ham & Seim Reference Van Ham and Seim2017; Seeberg Reference Seeberg2014). Therefore, we include the Composite Index of National Capability (CINC) among our controls (Greig & Enterline Reference Greig and Enterline2010). Rents can be used to enhance repressive capacities or secure compliance by patronage. We thus include a measure of oil production per capita.Footnote 19

Ethnic polarisation can have detrimental effects for stability, governability and the prospects for democracy (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1993). To control for its potential effects, we include a measure of ethnic fractionalisation (Alesina et al. Reference Alesina, Devleeschauwer, Easterly, Kurlat and Wacziarg2003). We calculate this score based on the Composition of Religious and Ethnic Groups (CREG) data (Nardulli et al. Reference Nardulli, Wong, Singh, Peyton and Bajjaleih2012).

The degree to which civil society is capable of mobilising to press demands against the incumbent regime may also affect the likelihood of authoritarian failure and subsequent regime outcomes (Bunce & Wolchik Reference Bunce and Wolchik2011; Kaya & Bernhard Reference Kaya and Bernhard2013). We include a five‐year rolling average of the V‐Dem Civil Society Participation Index (v2x_cspart). We average over time to capture civil society capacity as a form of social capital that is acquired over time (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge2018a: 47).Footnote 20

Finally, we control for potential diffusion effects based on time and geography (Boix Reference Boix2011; Weyland Reference Weyland2014). As the post‐Cold War period heralded the rise of electoral authoritarian regimes, we include a post‐1988 dummy variable. To control for neighbourhood effects, we include the average V‐Dem electoral democracy score (v2x_polyarchy) for all other countries in the region (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge2018a, Reference Coppedgeb; Teorell et al. Reference Teorell, Coppedge, Skaaning and Lindberg2016).

Results

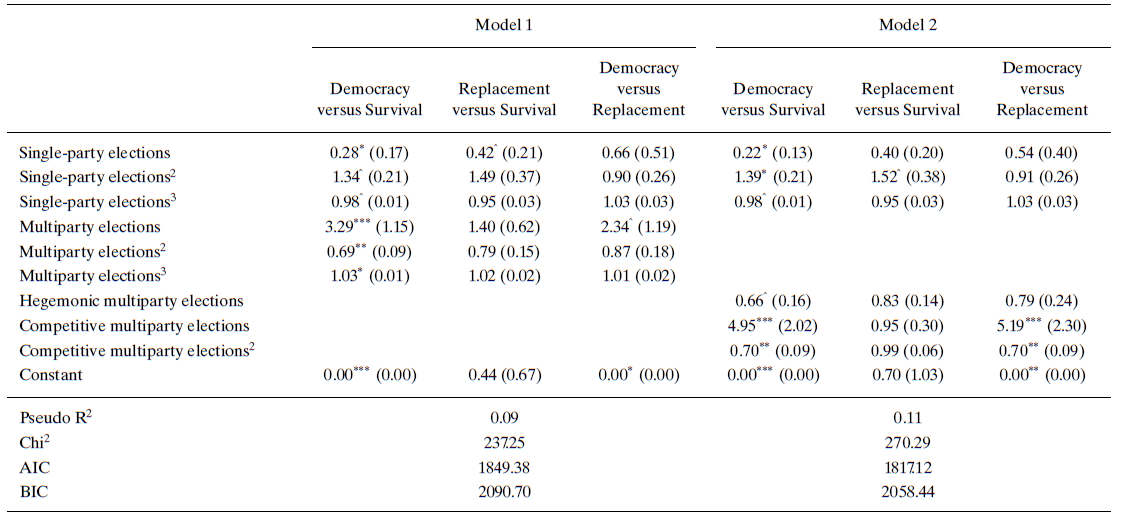

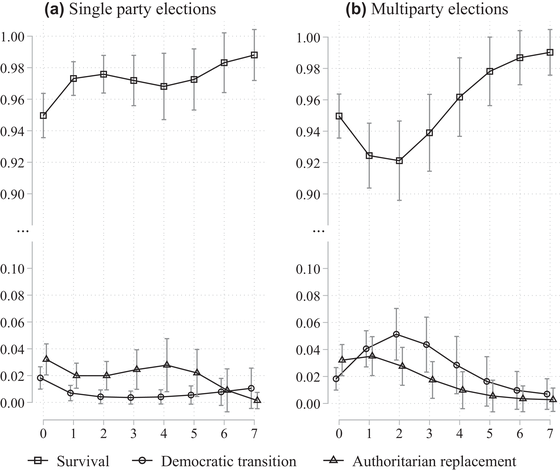

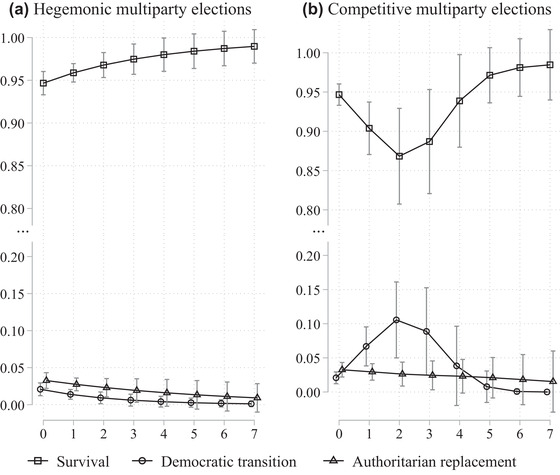

Our main models are presented in Table 1.Footnote 21 To aid in interpretation, we also provide adjusted predicted probabilities for different kinds of reiterated elections in Figures 1 and 2.Footnote 22 Model 1 compares the effects of reiterated single‐party and multiparty elections, and model 2 further differentiates hegemonic and competitive multiparty elections. In both models, observed regime‐years with zero on all election counts represent cases of closed authoritarianism. This acts as a baseline for comparison. All else equal, the models predict that closed authoritarian regimes have a 94–96 per cent probability of survival in a given year and low chances of democratic transition (0.99–2.65 per cent) and authoritarian replacement (2.05–4.37 per cent).

Table 1 Multiparty elections and authoritarian outcomes

Notes: Relative risks and country‐clustered robust standard errors from multinomial logistic regression. Dependent variable is regime outcome from Geddes et al. (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014). All models also control for GDP per capita (ln, t‐1), GDP per capita growth (t‐1), oil production per capita (t‐1), state capability (t‐1), ethnic fractionalisation (t‐1), civil society participation (five‐year average), post‐Cold War, previous authoritarian failures, regional democracy score and a cubic polynomial of time (t, t2, t3). Results for control variables are reported in Table A2 in the Online Appendix. N = 4,232; Regimes = 262; Countries = 110.

^p < 0.10

*p < 0.05

**p < 0.01

***p < 0.001.

Figure 1. Adjusted predicted margins and 95% confidence intervals for single‐party and multiparty elections.

Figure 2. Adjusted predicted margins and 95% confidence intervals for hegemonic and competitive multiparty elections.

The results in model 1 generally support earlier claims about the stability of single‐party regimes. As Figure 1 illustrates, for the first two reiterated single‐party elections, regimes are expected to experience increasing odds of survival. This corresponds with declining relative odds of democratisation. The third and fourth reiterated single‐party elections are associated with a slightly increased risk of failure, but the probability of survival remains above that found in closed regimes. During this same period, there is a slight increase in the probability of democratic transition. After four reiterated single‐party elections, the institutionalisation of the regime becomes apparent, with a fairly steady upward trend in the probably of survival with each subsequent election. The probability of democratic transition also falls off sharply, approaching zero by seven reiterated single‐party elections.

This suggests that reiterated single‐party elections entrench rather than threaten the regime. However, this finding is less relevant today given that single‐party regimes have become increasingly rare since the 1990s. The post‐Cold War international democratic consensus made de jure bans on opposition parties difficult to impose. Therefore, we read these findings as historically informative but less relevant for understanding contemporary authoritarianism.

The results for multiparty elections are consistent with our double‐edged sword hypothesis. As Figure 1 illustrates, for the first two multiparty elections, the odds of survival decline relative to democratisation. In addition, the first three reiterated election cycles see lower predicted odds of survival, when compared to closed regimes. The increased odds of failure during these first three reiterated elections are predominately explained by an increased propensity for democratisation. This suggests that the convoking of multiparty elections is indeed risky for autocrats in the short run.

However, in the long‐run, we see an upward turn in the odds of survival and a downward turn in the odds of democratic transition. After about three reiterated multiparty elections, electoral authoritarian regimes appear to have institutionalised, reaping legitimation benefits from each iteration of elections. By the seventh election there is little difference in survival probabilities for reiterated single‐party and multiparty elections. Again, we find no significant effect of reiterated multiparty elections on the relative risk of democratic transition over authoritarian replacement, and overall, we see a decline in the predicted probability of authoritarian replacement over iterative multiparty election cycles.

Model 2 tests for the institutionalisation of hegemonic and competitive authoritarian elections. Our previous findings for single‐party regimes remain robust. Early elections pose a slight threat, but overall dictators stand to benefit from holding non‐competitive elections. The institutionalisation of hegemonic multiparty elections appears to provide similar benefits. With each reiterated hegemonic multiparty election, we generally see an increasing probability of survival and decreasing probabilities of democratic transition and authoritarian replacement. This suggests that incumbents who are able to successfully institutionalise hegemonic multiparty elections may reap similar benefits as single‐party environments while paying lip service to multipartism. This has important implications for democratic proponents in hegemonic electoral authoritarian regimes. With each reiterated election, the ability to effect regime change becomes less likely. Nevertheless, this finding is only significant at the 90 per cent confidence level and is not robust to alternative model specifications presented in the Online Appendix.

Model 2 also suggests that the democratising effects of multiparty elections are driven by competitive electoral sequences. As Figure 2 illustrates, we see radically different effects for reiterated hegemonic and competitive elections, with the latter driving the shape of the findings in Figure 1. The first two competitive cycles yield decreasing odds of survival and increasing odds of democratic transition. However, for those regimes that manage to institutionalise competition, the odds of democratic transition begin to decrease starting on average with the third or fourth competitive election. Still, the overall survival probability for competitive electoral regimes only approaches that of the hegemonic electoral regimes after five or six elections.

Robustness checks

In the Online Appendix we present several robustness checks. First, we provide a set of binary logistic models testing whether reiterated elections make authoritarian regimes more prone to democratise (Table A6). The democratic transition models include both the full sample and a sample restricted to failure events, allowing us to compare our main results for authoritarian replacement.Footnote 23 These models are congruent with our findings for multiparty and competitive multiparty elections from the discrete‐time competing risks models. In Table A7 we control for monarchy, personalist and military regimes, with party‐based regimes as the reference category (Geddes et al. Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014). The results for reiterated multiparty and competitive elections remain robust; although the single‐party election counts lose some significance (but remain robust at the 90 per cent level), and hegemonic multiparty elections lose significance altogether. This suggests that the party‐based category may be soaking up the effects of reiterated elections in single‐party and hegemonic multiparty regimes, but that multiparty elections within monarchies (e.g., Morocco and Jordan) are not substantively affecting our results.

Second, electoral authoritarian regimes sometimes move from hegemonic and competitive episodes without experiencing an electoral interruption. In our sample, 18 regimes shift from competitive to hegemonic, 31 from hegemonic to competitive, and six move in both directions. Our main models ignore this nuance, resetting the count to zero whenever a regime shifts between hegemonic and competitive. If prior sequences of more or less competitive multiparty elections influence the effects of subsequent sequences, this could bias our results. However, it is likely to work against our findings by reducing the estimated effects of reiterated elections occurring in a sequence in which the level of electoral competitiveness changes. In Table A9, we take this into account by controlling for the number of hegemonic or competitive elections preceding the current sequence. We also include dummy variables controlling for whether the current sequence of elections was immediately preceded, without an electoral break, by a sequence that was more or less competitive. Again, our main results substantively hold, but hegemonic multiparty elections lose significance.

Third, it is possible that our findings are the result of endogenous frailty and/or ongoing liberalisation processes. If weaker authoritarian regimes are more likely to open electorally, the estimated effects of competitive elections could be driven by a predisposition to collapse rather than protracted struggle and democratic learning. Likewise, if hidden democratic actors within an authoritarian regime are able to push for competitive elections as part of a gradual process of democratisation from within, our conclusions about the effects of electoral institutionalisation would also be endogenously driven. This is particularly the case given our findings regarding the differential effects of elections at earlier and later periods of institutionalisation.

To address this concern, we employ a control function (CF) model to partial out the exogenous effects of competitive multiparty elections. CF models offer a flexible instrumental variables (IVs) approach when the dependent variable and/or endogenous predictor is non‐continuous. This involves three steps: estimating a first‐stage model regressing the endogenous predictor on the instrument(s) and other covariates; obtainingthe residuals from this model; and controlling for these residuals in a second‐stage explanatory model for the outcome of interest. Classic two‐stage IV models present a particular challenge in our case because the dependent variable is nominal, the potentially endogenous predictor is measured as a count and the relationship between the potentially endogenous predictor and the outcome is nonlinear. As Wooldridge (Reference Wooldridge2015: 429) explains: ‘In models with multiple, nonlinear functions of the [endogenous explanatory variables], the CF approach parsimoniously handles endogeneity and provides simple exogeneity tests.’

We follow this estimation strategy using the V‐Dem party institutionalisation index (v2xps_party) as an instrument for the number of reiterated competitive multiparty elections (Bizarro et al. Reference Bizarro, Hicken and Self2017; Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge2018a: 243). A valid instrument meets two criteria: (1) it is sufficiently correlated with the endogenous predictor; and (2) it does not directly affect the outcome variable – its effect only occurs through the mediating (i.e., endogenous) predictor. The party institutionalisation index accounts for whether parties have permanent national organisations (v2psorgs) and local branches (v2psprbrch), how they link up with their constituents (v2psprlnks), the extent to which they have distinct party platforms (v2psplats) and their degree of legislative party cohesion (v2pscohesv). It captures the average for all parties in the system. The assumption that party institutionalisation is a fairly good predictor of the number of competitive elections an authoritarian regime has held, satisfying the first criterion, is verified empirically and reported in the results in Table A10 in the Online Appendix.

With regard to the second criterion – the exclusion restriction – we do not expect that the party institutionalisation index has a direct effect on regime outcomes because it gauges the average level of political party institutionalisation, irrespective of the number of parties in the system. Countries with high rankings on this indicator include party systems that are more likely (many competitive well‐organised parties) and less likely (one highly organised ruling party) to experience regime change. Therefore, scores on this indicator are unlikely to have any direct causal impact on regime change because it does not reflect the balance of power between political forces critical to understanding regime outcomes. Theoretically, then, the instrument should satisfy the second criteria (though it cannot be empirically tested).Footnote 24

In our first‐stage model, we regress the reiterated competitive multiparty elections count on the IV and the control variables from our main models using a negative binomial regression model.Footnote 25 The results suggest that party system institutionalisation is highly correlated with the competitive multiparty election count (Table A10, Model A20a in the Online Appendix), satisfying the first criterion for a valid IV. In the second stage, we estimate the exogenous effect of reiterated competitive multiparty elections by including Pearson residuals from the first‐stage model. The estimated parameter for the residuals represents the endogenous effect of competitive elections. The added benefit of this IV strategy is that a single control function suffices for all nonlinear functions of the endogenous predictor.Footnote 26

The results reported in Model A20b suggest that our previous findings are fairly robust when controlling for endogeneity. Overall, the use of the CF model enhances the significance of single‐party elections and hegemonic multiparty elections. For the first time, we also find a significant effect of reiterated competitive multiparty elections on the relative odds of replacement over survival. The control function coefficient is also significant for this pair of outcomes, suggesting that the endogeneity concerns are greatest when it comes to questions about elite splits in the authoritarian regime and/or other processes that replace incumbents with new sets of autocratic actors and rules.

Discussion

Multiparty elections exhibit the kind of double‐edged effect we hypothesised. Electoral openings in authoritarian regimes produce a period of enhanced threat, primarily of democratisation, followed by a period of reduced threat and stabilisation. However, this effect on regime outcomes diminishes as the level of electoral competition weakens. Hegemonic multiparty elections with lower levels of competition may have a stabilising effect, reinforcing the status quo, perhaps providing support for arguments that elections help incumbents maintain their position in power by revealing important information, building credible commitments within the ruling coalition, or providing popular legitimation. However, caution is in order due to inconsistency in the robustness tests presented in the Online Appendices.

By contrast, competitive multipartism under authoritarianism conforms to the double‐edged sword hypothesis. The conduct of elections under competitive conditions is dangerous for autocratic incumbents, at least in the early stages making them more prone to democratic transition. Autocrats face the highest threat of democratisation during the first two or three competitive elections. Following that, the threat posed by competitive elections diminishes with each iteration, indicating that authoritarians who master the challenge of competitive elections can construct durable electoral regimes. Still, even beyond the period of heightened threat, the overall chances of regime failure are higher than those for hegemonic electoral and closed authoritarian regimes providing confirming evidence of the competitiveness hypothesis generally.

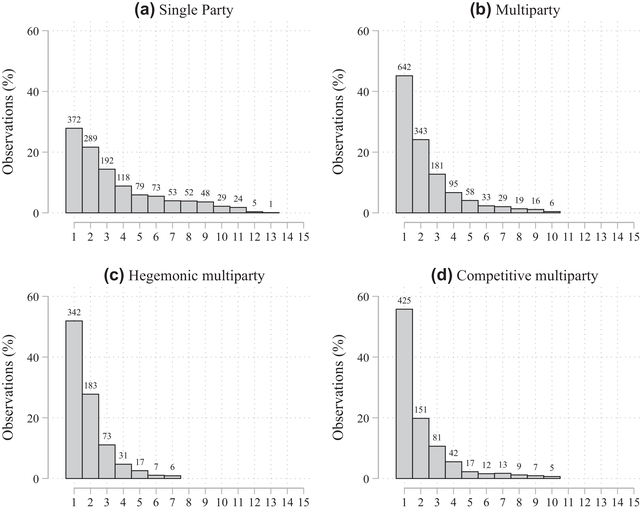

How often do authoritarian regimes actually survive past two or four competitive elections? Figure 3 plots the number of reiterated elections observed within our sample. About 36 per cent of the regime‐years occur under closed authoritarianism. The average single‐party regime in our sample experienced three to four elections. On average, both hegemonic and competitive electoral authoritarian regimes experienced about two elections.

Figure 3. Distribution of observations for election count variables.

This could suggest that the long‐run stabilising benefits of multiparty elections are relatively rare. Most of the cases coded as electoral authoritarian have experienced fewer than three elections. Electoral authoritarian regimes may not have managed to safely institutionalise electoral mechanisms and reap their potential benefits. Did they fail before they could institutionalise? If this is the case, our double‐edged sword finding could be driven by a few highly institutionalised cases (e.g., Botswana and Singapore).

We do not know the ultimate fates of the right‐censored cases in our data, but if these are cases that have institutionalised, our descriptive analysis in Figure 3 may underestimate the role of elections in establishing authoritarian stability. While we cannot be certain whether an ongoing case of electoral authoritarianism has ultimately consolidated, we can compare the average number of reiterated elections observed in censored and uncensored regimes. As Table A11 in the Online Appendix demonstrates, our uncensored observations (those which have already failed by 2010) tend to have experienced significantly fewer reiterated multiparty and competitive elections when compared to the censored observations. This suggests that the censored observations are more durable.Footnote 27 This implies that low numbers in the descriptive statistics presented here are a function of the novelty of electoral authoritarianism as a regime type and that future tests with temporally expanded data will allow us to confirm this.

Conclusion

The collapse of a large number of conventional authoritarian regimes in the last quartile of the twentieth century did not lead to the universalisation of democracy. The number of democracies did expand, but of equal importance was the incorporation of multiparty elections into the framework of authoritarianism. The development of electoral authoritarianism was seen by some comparativists as a solution to the problem of authoritarian survival in an age of democracy and by others as the introduction of a subversive element which increased authoritarianism's vulnerability to regime change.

These two logically contradictory claims could not be valid without some sort of meditating factor. This article addresses this conundrum in a novel fashion by analysing the ability of authoritarian regimes to institutionalise elections. We pinpoint two critical factors for understanding this process. First, electoral authoritarian openings entail much higher levels of uncertainty in their initial stages, but with reiteration and political learning this diminishes. Second, the results of such openings are contingent on the balance of power between regime incumbents and the opposition. Such an approach requires three modelling features: gauging the differential impact of elections within reiterated sequences; distinguishing between more and less competitive elections under authoritarianism; and looking at two alternatives to incumbent regime survival – democratisation and authoritarian replacement.

Generally, our tests show that higher levels of electoral competition are more dangerous for authoritarian regimes, but most alarmingly in the short term during the first three elections following an opening. However, those regimes that manage to survive past the first few competitive electoral cycles – that is, those which successfully institutionalise elections – face diminishing risks. This initial danger is reduced when authoritarian regimes find effective ways to cope with political opposition and democracy activism to win competitive elections.

Our exploration of different forms of authoritarian failure provides a set of nuanced results as well. For those authoritarian regimes that do fail, the holding of reiterated competitive elections makes them more likely to transition to democracy than a new form of authoritarianism (confirming Brownlee Reference Brownlee2009). The effect is enhanced in the early stages of the electoral sequence but diminishes after the first few iterations. In general, our models addressing the trade‐off between authoritarian replacement and survival suggest that elections have little effect. Those findings are driven by economic performance.

In contrast to the double‐edged sword of competitive elections, there is some evidence that authoritarian regimes that hold multiparty elections with limited competition may be more durable. However, the results do not quite reach conventional levels of significance and these findings are not durable in our robustness tests. Given the relative novelty of electoral authoritarian regimes, we believe it would be prudent to return to this question with an expanded temporal sample in the near future given the suggestive nature of what we have found here.

Given these findings on competitive elections and multiparty elections, our ultimate conclusion is that dictators who stage elections in the hope that democratic emulation will make their rule more durable are playing a somewhat dangerous game. In the earliest stages of this process they place their rule at enhanced risk of failure, especially if the opposition can mount early competitive challenges. If the regime can navigate this risky period, they may extend their time horizons. For those authoritarian regimes that are able to manage pressures for democratisation by keeping competition in check, elections should help them to re‐establish their power on a secure footing. But all in all, unless they can devise effective strategies for mastering electoral competition, dictators who stake their future on democratic emulation are more like gamblers than contemporary Machiavellis.

Acknowledgements

This research project was supported by European Research Council, Grant 724191, PI: Staffan I. Lindberg, V‐Dem Institute, University of Gothenburg, Sweden; Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, Grant M13‐0559:1, PI: Staffan I. Lindberg, V‐Dem Institute, University of Gothenburg, Sweden; by Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation to Wallenberg Academy Fellow Staffan I. Lindberg, Grant 2013.0166, V‐Dem Institute, University of Gothenburg, Sweden; as well as by internal grants from the Vice‐Chancellor's office, the Dean of the College of Social Sciences, the Department of Political Science at University of Gothenburg; and the University of Florida Foundation in support of the Miriam and Raymond Ehrlich Eminent Scholar Chair in Political Science. We performed simulations and other computational tasks using resources provided by the Swedish National Infrastructure for Computing (SNIC) at the National Supercomputer Centre in Sweden. Earlier versions of this article were presented at seminars at the political science departments of University of California‐Berkeley, Aarhus University, the Leuphana University of Lüneburg and Gothenburg University. We are grateful for the opportunity and the feedback that we received.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting informationmay be found in theOnlineAppendix section at the end of the article:

Replication Data Codebook

Online Appendix