1. Introduction

Generations of competition law scholars and practitioners have been moulded in a version of competition law that prioritizes economic objectives. Over the past half century, welfare and the safeguarding of the competitive process became the predominant goals of competition law as they emerged through a dialogue between the world’s most influential antitrust jurisdictions – the United Stated (US) and the European Union (EU).Footnote 1 On the one hand, the hegemony of the Chicago School – born in the US and exported to the rest of the world partly by means of academic brute force and partly as a reflection of the Washington consensus in the process of globalisation –Footnote 2 pushed for consumer welfare as the ultimate goal of antitrust law.Footnote 3 Meanwhile, the EU, caught between the influence of the Chicago SchoolFootnote 4 and a more Ordoliberal tradition reflecting a concern for the freedom to compete,Footnote 5 gave special regard to the preservation of the competitive process and undistorted competition too.Footnote 6 Other related goals, such as economic efficiency and the creation of a level playing field in the market, also infiltrated EU competition law, adding to its economic-oriented analysis and enforcement.Footnote 7

Yet, despite the broad acceptance of the economic focus so far, cracks have started to emerge. Foundational tenets of the economic thinking that characterised competition law began to be challenged (as, for instance, whether increased output or innovation are always desirable),Footnote 8 and social, environmental and technological considerations became common items of the discourse.Footnote 9 This is particularly true in EU competition law, because competition sits alongside other policies in the Treaties and some conflict and cross-pollination is inevitable.Footnote 10 The financial crisis of 2008, changed perceptions as to the role of governments in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, the increasing urgency of the climate and environment crisis, and the new economic crisis caused by increasing energy prices and cost of living in major economies, have created a fertile ground for questioning the soundness of neoclassical economics and neoliberal economic policies. Trickle-down economics have proven chimericFootnote 11 ; inequality is on the riseFootnote 12 ; market concentration is increasing too.Footnote 13 BigTech is seen as eroding privacy and as wielding too much political power.Footnote 14 Powerful undertakings keep precipitating ecological disaster despite knowing the effects of their actions,Footnote 15 casting into doubt their ability and incentives to provide innovative solutions to the problems they have helped create. Against this backdrop of questioning the obsession with economic goals inspired by the Chicago school, and as competition law and policy are the general horizontal backstop mechanism of market discipline, competition lawyers, practitioners, academics, and policy makers are having to reconsider what competition policy is for.

In this cornucopia of modern challenges and corresponding opinions on the role of EU competition law, we attempted to provide some initial much needed data-driven clarity in an earlier study published in 2022.Footnote 16 It was the first comprehensive empirical investigation into the goals of EU competition law as revealed through the entirety of the case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU or the Court), the decisions of the European Commission, the Opinions of Advocate Generals (AGs) of the CJEU, and speeches of EU Commissioners for Competition from 1960 to 2021 (3,749 documents). In that study, we focused on the more traditional (economic) goals of EU competition lawFootnote 17 and we offered several insights – some confirming and some debunking theories on the role of EU competition law, both historically and today.

But as the debate continued and evolved, and as EU integration progressed, it became imperative to investigate additional goals and objectives of EU competition law that corresponded to the various, more recent, challenges and considerations mentioned earlier. Similarly to our first study, we wanted to uncover not whether EU competition law should encompass additional goals (there is ample literature on that, which we cover in Section 3), but whether as a matter of the practice of EU institutions it actually does. Additionally, we wanted to do so not through anecdotal evidence but by examining the entire body of EU’s decisional practice in competition law plus the public statements of Commissioners for Competition.

In this article, we present the results of this expanded empirical research (4,048 documents from 1960 to 2022). We chose to focus on the three additional goals of sustainability, labour rights, and privacy, having identified them through our methodology as the most promising and consequential ones. They reflect not only areas that have experienced elevated policy activity in the EU, but also areas that EU competition law has struggled to make sense of.Footnote 18 Our findings inject data into the debate of EU competition law’s role, provide insights that can derive only from a comprehensive overview of all available EU institution sources, and help dispel misconceptions that might arise by overly focusing on cherry-picked high-profile decisions while overlooking the rest of the EU’s institutional practice. This is not to suggest that there is a large number of relevant sources on the goals we study; in fact, it becomes apparent from our results that the competition aspects of sustainability, labour rights, and privacy have remained somewhat muted in the practice of EU institutions. But this in itself is a telling insight, which we analyse.Footnote 19 More importantly, this and the rest of our results can only emerge through a look at the totality of EU’s decisional practice. In that sense, we do not criticize existing approaches or methodologies; we complement them.

Overall, we find that sustainability is partially recognised as a goal of EU competition law in the caselaw whereas privacy and labour rights are not. This reflects the confusion in the literature on the role of EU competition law in protecting or promoting sustainability, labour rights, and privacy: although numerous academics, commentators and practitioners think these goals should be pursued by competition rules,Footnote 20 those views are far from universal. At the same time, our research enables us to understand why things are the way they are. We show that all three goals are (to the extent recognised) more recent than classic goals, which makes them less central to the competition law system, and we examine how they infiltrate the competition law system through the lens of the history of European integration and the EU economic constitution, as well as the nature of the relevant EU competences. We further show that the rhetoric of the Commission is in contrast to the actual decisional practice and that, thematically, the EU institutions have not had to engage with them much in their work. These key results are examined through the lens of the history of EU integration and of the EU’s economic constitution, and the nature of the relevant EU competences in each of the three goals to offer possible explanations. Moreover, we identify trends in the cases, decisions, and speeches that may bode for change in the coming years, particularly when it comes to possible entry points for these goals to be considered and eventually fully recognised by the Court and the Commission as goals of EU competition law. Examining the past in such detail enables us to understand the present, and aspirationally to provide the community with fresh insights to anticipate the future.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we present our methodology, which is important to understand in order to correctly appreciate the results in Section 4 and be able to draw safe conclusions from them. Moreover, the extensive explanation of the method enables other researchers to conduct similar searches for other contemporary goals of competition policy, such as gender or racial equality. In Section 3, we undertake an extensive literature review to explain why we decided to focus on the three aforementioned goals and how we chose the keywords that we searched for. In Section 4, we present the results of the search for keywords associated with the three goals in the case law of the CJEU, Commission decisions, Opinions of Advocates General, speeches of Commissioner’s for competition, for the years 1960–2022, in antitrust and merger control and we comment on those results. In Section 5, we conclude.

2. Methodology

The methodology followed in this study has been adapted from the one used in the original study on the goals of EU competition law published in Legal Studies.Footnote 21 Due to important differences that have been introduced compared to the original methodology and because familiarity with it is indispensable to understanding the results, the full methodology employed in this study is summarized herein.

As a first matter, we note that our methodology is data driven, meaning that we did not set out to test a particular hypothesis nor did we anticipate specific results. This is key for an investigation of this type because the question of whether sustainability, labour rights protection, and privacy are goals of competition law is highly contested, and a neutral methodology is necessary in capturing the true state of EU institutions’ decisional practice.

The investigation was based on full text keyword search, meaning that we assigned keywords to each of the three goals under investigation and searched the source documents for these keywords. The first step was to compile the list of candidate goals as well as the list of corresponding keywords that denote reference of those goals. We define goals as the objectives that competition law seeks to safeguard by outlawing conduct that undermines them.Footnote 22 When conduct is found unlawful by courts or enforcers it is because it contravenes what competition law was tasked to protect (ie any of its goals). Sometimes, this is stated explicitly. For instance, AG Cosmas opined in Diego Calí that ‘the case-law of the Court clearly indicates that protection of the environment is recognised by the Court itself as an objective ‘in the general interest’ justifying the restrictions on freedom of trade and freedom of competition.’Footnote 23 Other times a (putative) goal is rejected explicitly, which helps place limits around what can be considered a goal of competition law. For instance, the Commission in the Facebook/WhatsApp acquisition ruled that ‘any privacy-related concerns flowing from the increased concentration of data within the control of Facebook as a result of the Transaction do not fall within the scope of the EU competition law rules but within the scope of the EU data protection rules.’Footnote 24 The flip side of identifying goals by looking at conduct that undermines them is identifying goals when they are referred to as justification why conduct does not violate competition law. For instance, the Commission in Assurpol found that an agreement does not violate competition law because it served the protection of the environment, which the Commission accepted as an art 101(3) TFEU justification, alongside economic efficiencies, one of the more traditional goals of competition law.Footnote 25 Assurpol also well exemplifies our understanding of goals as those that are subsumed under other, often more established, goals (see also Rule 3 further down). For instance, in Assurpol the Commission directly linked environmental protection to efficiencies and used it to justify (ie declare that it does not violate competition law and its goals) the agreement in question.

In all these cases, the reasoning why conduct is compliant or not with competition law was linked to a goal of competition law. This focus on recognising as goals only objectives that are linked strictly to what competition law recognises as lawful or unlawful helped us steer away from broader open-ended discussions around competition law’s role in society and economy, something that often came up in speeches of Commissioners for Competition. For instance, Vestager has asserted that ‘competition policy remains a tool that serves the needs of European citizens … as workers who benefit from a vibrant labour market’,Footnote 26 but such statements were not sufficient for us to be used as evidence that labour rights are a goal of competition law, because they are uncoupled from competition law’s main function of finding conduct (un)lawful based on the goals it endorses.

The question then becomes how to identify candidate ‘new’ goals of competition law. After all, because competition law is a horizontal backstop system, it can, in theory, be called to fix any perceived market distortion, no matter its cause. For that, we had to identify goals (on top of the ones identified in the previous study)Footnote 27 which on the one hand are analysed in the literature as relevant goals, but also on the other hand enjoy some recognition in the EU institutions’ decisional practice, which was what this study measures. The second condition was what really set the boundaries of our investigation, because some of the goals identified in the literature, such as the safeguarding of the democratic process,Footnote 28 culture,Footnote 29 or gender equality,Footnote 30 returned no results in the decisional practice and so were unsuitable for our methodology. We settled on sustainability, labour rights protection, and privacy, because, as documented in the literature review below, there is sizeable or at least growing support for those goals, and the keyword search at the core of our methodology returned enough results to perform meaningful analysis. What binds them together is that they are not seen as traditional goals of competition law, but are nevertheless commonly discussed as potential new goals, which is precisely what we sought out to investigate empirically. In the end, the selected goals reflect an organic evolution of competition law, rather than an externally imposed research choice.

The identification of the keywords corresponding to each goal was done initially through the literature review and the relevant caselaw that was cited within as representative of discussing the candidate goal. Upon a first selection of keywords, we then ran iterative rounds of search through CJEU decisions to ensure the keywords were both exhaustive and correctly assigned to the investigated goals. In total, we catalogued 53 keywords assigned to the three new goals selected (Table 1).

Table 1. The new goals of EU competition law and corresponding goals

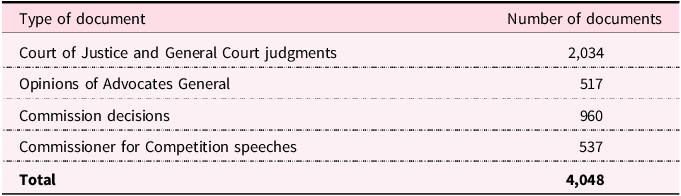

We then constructed the list of sources to search through. Our sources included CJEU decisions (to include both Court of Justice and General Court decisions), AG opinions, Commission decisions, and Commissioner for Competition speeches from 1964 to 2022. For CJEU decisions and AG opinions we used the Curia database, which allows full-text search. In total, we searched through 2,034 CJEU decisions and 517 AG opinions.

For Commission decisions, we relied on the DB-COMP database,Footnote 31 since the Commission’s own online database does not allow full-text search and does not include decisions prior to 1998. The DB-COMP database lists all Commission decisions with substantive discussion of law, which was sufficient for our purposes, because these are the only decisions that are likely to include a discussion on the (new) goals. In detail, the Commission decisions we searched through are as follows: (a) for articles 101 and 102 TFEU: commitments decisions, interim measures, prohibitions, and (reasoned) rejection of complaints decisions, as well as article 106(3) TFEU decisions only in so far as they included a discussion as to an infringement of article 102 TFEU; (b) for concentrations decisions, we reviewed Phase II decisions under the same rationale that they are the most likely to include a discussion on the goals of EU competition law as opposed to the more superficial analysis conducted in Phase I scrutiny. In total we searched through 960 Commission decisions.

For public speeches delivered by Commissioners for Competition we relied on the Commission’s online archives, both the compressed archive up to 2020 and the newer speeches delivered by Commissioner Vestager in 2021–22.Footnote 32 In total, we searched through 537 speeches. We chose to consider speeches in the investigation as well, even though they do not represent binding jurisprudence, because they still constitute a platform by which the Commission disseminates its thinking. Being more informal, they can help us calibrate and interpret our results. The grand total of the number of sources we searched through was 4,048 documents.

From the result lists as per above we went into each document, searched for all keywords in Table 2, decided whether they relate to one of the selected new goals of EU competition law (based on our methodology further below), and if so, we recorded the metadata in Table 3:

Table 2. Types and numbers of sources searched

Table 3. Recorded metadata for each documented source

Table 4. Rules of inclusion/exclusion of sources in results

We treated all text in decisions and opinions as equal (ie, we did not differentiate between legal reasoning, obiter, etc), under the assumption that the whole text of decisions and opinions contributes to their outcome (but see Rule 2d below). Attempting to treat some parts of decisions and opinions as more influential or authoritative than others would introduce an unmanageable degree of subjectivity. We also treated all sources as equal. This being primarily a quantitative analysis, the focus was to derive insights from a collective look at institutional practice rather than dissect specific decisions, opinions or speeches. We acknowledge that not all sources can in reality be equal. Crucially, speeches do not have the same standing as decisions and opinions and rulings of the CJEU sitting in Grand Chamber carry more weight. We make sure to present our findings in a way that allows readers to detect which institution the sources are affiliated with and we do highlight those differences in our result analysis. Considering further differences, such as date of issuance, type of decision (eg preliminary ruling or appeal) etc, and assigning differential weight based on such differences, would introduce subjectivity incompatible with the quantitative analysis undertaken here. For instance, while one can reasonably assign more weight to recent decisions as more pertinent to current practice, an opposing view can consider older decisions that are still cited today more influential as pioneering the endorsement of the relevant goal. The literature we review below provides this kind of qualitative analysis; our analysis complements it with insights that can only emerge from a high-level comprehensive quantitative view.

To decide whether the use of the chosen keywords denotes a statement on the goals and purposes of EU competition law we distinguished between three possibilities as follows:

To account for the difference in how ‘valid’ NY results compare to Y results, we have prepared two sets of results, one counting only Y results and one counting both NY and Y results. For the purposes of our analysis in Section 4 we relied on Y and NY results, unless otherwise indicated. This is a point of departure from the methodology followed in our previous study, where we relied only on Y results. This is because in the previous study NY results expressed instances where the keyword was used ‘in a context that signifies a statement on the goals of EU competition law, but the context in which it appears is a verbatim or only slightly paraphrased excerpt from primary or secondary EU competition law source …, such that it makes it impossible to tell whether the keyword was used as a conscious choice of words to signify a goal of competition law or because it appears in the black letter of the law’.Footnote 36 While these results could not be completely excluded (N), they also did not reflect a conscious choice of words denoting the endorsement of a competition law goal. Therefore, we opted to not base our analysis on them. However, in this study, NY results do denote endorsement (rule 3), just indirect, and therefore it is appropriate that the analysis is based both on Y and NY results.

We also applied the following rules:

-

Rule 4: Cases that have advanced through different instances (eg, a Commission case which was appealed to the GC and then to the CJ) are counted separately, because a new decision is issued at every instance, unless Rule 2d applies.

-

Rule 5: The same quote can contain keywords that refer to different goals and may be counted separately for each goal.

-

Rule 6: Multiple keywords grouped under the same goal are counted once, because they all signify the same goal. If some keywords are counted as NY or N and some as Y, Y prevails.

Further, because the goals of sustainability, labour rights protection, and privacy are specialised, and therefore would not come up in cases that do not concern those areas, we also had to identify the sources that fell within those areas. For instance, privacy became more relevant in the digital era, labour rights were mostly referred to in cases that involve collective agreements or, more recently, the precarious working conditions in the gig economy. Sustainability and environmental protection were more likely to be discussed in the context of highly polluting consumer-facing industries (eg, diesel cars) or when companies are large and influential enough to affect key parameters of the Earth system, such as biodiversity (eg, large agrochemical companies). This thematic identification of sources allowed us to situate the relevant hits within the population of sources wherein they could indeed arise, rather than within the general population of all sources.

-

Rule 7: A case is considered to thematically fall within sustainability, labour rights protection, or privacy, when these topics, as expressed through the corresponding keywords in Table 1, arise in the legal reasoning of the issuing institution as part of the theory of harm. In 101 TFEU cases, this would be the discussion of why the agreement is anticompetitive; in 102 TFEU cases, this would be the theory of harm in establishing abuse of dominance; and in concentrations, this would be the competitive assessment of the concentration. We considered it highly unlikely (and we did not encounter any disproving example) that a case would situate competition law in the context of sustainability, labour rights protection, or privacy without this coming up in the core part of the case as defined above, which concerns itself with why and how competition law was potentially violated. One example of a case where keywords linked to an investigated goal did come up but not in the context of the theory of harm, and accordingly not counted as thematically relevant, is IMS Health (COMP D3/38.04). In that case, data protection (a keyword linked to privacy) came up frequently because the ‘brick structure’ of IMS’s data was chosen ‘mainly so to create segments with equal sales potential, and to comply with data protection law’ (para 17). While data protection was discussed as feeding into IMS’ data choices, it did not matter for the issue of IMS’ potential anticompetitive conduct, and therefore we did not consider that the case was thematically within data protection and privacy. We also excluded, by extension of Rule 2a, instances where the keyword was irrelevant to the theme of the investigated goals; for instance, in Dow/DuPont (M.7932), the keyword ‘data protection’ appears often but in the literal sense of the protection of the companies’ data as a matter of security or intellectual/industrial property.

A last note on methodology is due. It is likely that conduct in certain areas of economic activity or certain competition law offences are prosecuted more often than others. This can affect the occurrence frequency of the keywords encountered in the respective sources and can skew results in favour of those types of cases. There are two ways to approach this concern. Firstly, if certain types of conduct involving sustainability, labour, rights, or privacy, are more common, and this in turn results in more cases around said conduct, then an argument can be made that competition law does indeed serve the relevant goals associated with the conduct to a greater extent, and we would want to document that. Secondly, this concern only affects results that rely on the total number of cases in each area; the rest of our insights are not sensitive to this kind of bias.

3. Literature review

The last few years have seen a resurgence of the competition law and public policy debate and concomitantly of possible new goals for competition law. We present in this Section the state of the literature on the three new goals of EU competition law that we selected, namely sustainability, workers’ rights and labour protections, and privacy. We do so both to establish that there is theoretical support for these three goals, thereby justifying our focus on those goals, and to contextualize them particularly as regards our choice of keywords.

A. Sustainability

Given the ubiquity of the topic of the climate and environmental emergency,Footnote 37 it is not surprising that there is currently a lot of talk about the relation of sustainability with competition law. Public and private initiatives on this matter are undertaken on all levels of competition law governance. Industry is increasingly calling for clearer guidance as to how undertakings can collaborate on sustainability projects without risk of breaching antitrust rules.Footnote 38 On a political level, the Commission has recognised that competition policy can be used supportively of the Green DealFootnote 39 and so has the European Parliament.Footnote 40 On the enforcement level, the Commission’s Directorate General for Competition (DG COMP) initiated a public consultation on the matter in 2020Footnote 41 and presented certain initiatives for taking into account sustainability in competition law enforcement in relation to agreements, mergers, and state aid in 2021.Footnote 42 It has also included a specific chapter on sustainability agreements into its revised Horizontal Guidelines, thereby introducing certain clarifications and modifications in the way it sees sustainability benefits within the Article 101(3) TFEU efficiency justification.Footnote 43 Several European national competition authorities (NCAs) have also taken initiatives related to sustainability, with the DutchFootnote 44 and GreekFootnote 45 authorities taking the lead followed by the Austrian,Footnote 46 Belgian,Footnote 47 FrenchFootnote 48 and United KingdomFootnote 49 ones, while the European Competition Network (ECN) launched a specific project on the topic in an effort to provide DG COMP with common EU NCA suggestions.Footnote 50 On the international level, discussions on the matter have been undertaken at the OECDFootnote 51 and at the International Competition Network (ICN).Footnote 52

In light of these developments, sustainability and environmental protection was an obvious contemporary goal for us to empirically test with our research. As with the other goals, we went through relevant literature, case law, and decisional practice, to see whether the goal is indeed considered one for competition law and to identify keywords to search for.

Historically, and in line with the EU’s gradual development of an environmental policy, the debate on the relation between competition policy and sustainability started mostly concerning environmental protection specifically, rather than sustainability in general, with the 1999 CECED decision providing some impetus.Footnote 53 The Commission also included a specific chapter in the old horizontal guidelines on the exemption of agreements seeking to achieve ‘pollution abatement, as defined in environmental law, or environmental objectives’, as defined by the EU’s environmental policy.Footnote 54 The debate took off in earnest with the entering into force of the Lisbon Treaty, which introduced horizontal provisions of general application to the TFEU. One of those is Article 11 TFEU, which requires environmental protection to be integrated into the definition and implementation of the EU’s policies and activities, in particular with a view to promoting sustainable development.Footnote 55 Some relatively early representative works exploring the integration of environmental protection into competition policy required by Article 11 TFEU are those of KingstonFootnote 56 and Nowag.Footnote 57 This early decisional practice, soft law, and research focused mostly on finding ways for EU competition policy not to interfere with agreements between undertakings that pursued environmental goals, explaining the emphasis on Article 101(3) TFEU. Hence, environmental protection must have been seen as a goal of competition policy itself only to the extent it could be ‘subsumed’ in the existing analytical framework and the accepted goals, such as welfare and efficiency. Simply, the environmental benefit had to be ‘translated’ into an efficiency or quality improvement that would be appreciated by consumers for it to be relevant for competition law.Footnote 58

In the last few years, the debate has intensified as a result of climate change and the increase in efforts to tackle the climate and environment emergency, not least through the European Green Deal.Footnote 59 As the EU’s ambitious goals of transforming the economy require every policy area to do its part, research on competition law and sustainability has flourished and its scope has expanded beyond environmental protection.

Contemporary literature on the topic explores various aspects of the interface between sustainability and competition policy. First, some authors have directly tackled the question of whether sustainability is or should be a goal of competition policy and they have focused on exploring arguments and legal bases for that. Holmes’s work has been influential in this regard, revisiting the arguments about the effect of Article 11 TFEU and combining other legal bases such as Article 7 TFEU and provisions from the Charter of Fundamental Rights (the Charter).Footnote 60 Iacovides and Vrettos make the same argument even more forcefully, considering it a constitutional requirement to see sustainability as a goal of competition law and framing it in terms of ‘mainstreaming’ theories of human rights protection.Footnote 61 According to them, this entails that the Commission’s enforcement of competition rules must not only not interfere with sustainability and environmental protection, but must positively pursue them and integrate them in its goals, as a matter of EU constitutional law. For them, this means that ‘the enforcement of the rules ought to promote conduct that furthers sustainability and at the same time prevent conduct that leads to environmental degradation and social injustice’.Footnote 62 Moreover, they explicitly reject the proposition that sustainability is not an independent goal of EU competition law and argue that an abuse of dominance can be found even if the unsustainable practice cannot be ‘translated’ into classic types of abuse.Footnote 63

Second, a large part of the relevant literature does not explore so much the issue of goals, but rather focuses on how a more permissive application of antitrust rules could encourage undertakings to act more sustainably. The focus of this strand of research is Article 101(3) TFEU, drawing on the earlier cases, soft law and research mentioned above. Authors have explored and debated how the application of the four criteria in the exception – most importantly the ‘fair share’ criterion – could encourage agreements between undertakings that promote sustainability and solve market failures collectively.Footnote 64 Competition economists are also exploring practical ways to measure sustainability benefits, in order for them to be taken into account in effects analyses.Footnote 65 Overall, these authors take EU competition law’s role in, at least, not interfering with sustainability as granted and focus on finding ways to operationalise it. Monti provides an overview background piece that explores the different options EU competition law has for becoming ‘greener’ in this particular, limited, way.Footnote 66 Beyond Article 101 TFEU, Mauboussin and Iacovides have explored how a similar approach to that proposed for Article 101(3) TFEU could be applied for exemptions from abuses of dominance and Article 102 TFEU,Footnote 67 whereas Makris and Deutscher focus on how the Commission’s merger control can be conducive to sustainability by taking it into account in innovation theories of harm,Footnote 68 and Buhart and Henry synthetise arguments regarding efficiencies in general, whether they relate to agreements or merger control.Footnote 69

Third, more radical proposals have started to appear in the literature, seeking to shift the focus from competition law only being asked to be permissive as to conduct that promotes sustainability towards a more interventionist competition law that would actively further a sustainability goal, by striking down conduct, whether unilateral or coordinated, that is unsustainable. Iacovides and VrettosFootnote 70 (regarding abuse of dominance) and HolmesFootnote 71 and MeagherFootnote 72 (for antitrust in general) are the most representative of this research strand. FernandoFootnote 73 and YasarFootnote 74 make similar points specifically for the right to food. For our purposes, what is of interest from this strand of research is that for these authors, the goals of competition law should not only relate to matters of environmental protection, biodiversity and the climate emergency, but should include more broadly matters of social justice, (for instance, income inequalityFootnote 75 ) just transition, and addressing exploitation.Footnote 76 This explains our choice for some of the keywords in this goal.

Finally, some commentators are outright critical of incorporating sustainability considerations in competition law enforcement and think it should not be done. Loozen, for instance, argues that ‘EU competition law constitutes single purpose law that prioritizes the public competition interest over the general sustainability interest, and the Commission’s task to define competition policy does not include the competence to balance competition and non-competition interests like sustainability.’Footnote 77 Peeperkorn claims that furthering sustainability through the enforcement of EU competition law would make its application more complex, costlier, slower and less certain.Footnote 78 Others think that even if sustainability is relevant for competition law, taking it into account may be counterproductive.Footnote 79 Certain EU NCAs and researchers are concerned that incorporating sustainability considerations into competition law enforcement may lead to ‘greenwashing’ and may operate as a licence to undertakings to enter into cartels or otherwise compete less fiercely, with negative effects on both sustainability and competition.Footnote 80

In sum, sustainability is accepted by some to be a direct goal of EU competition law, while others only consider it to have indirect significance, and some reject its relevance altogether. The Court has not settled the matter and DG COMP’s stance remains ambiguous. While accepting that EU competition law can act supportively of sustainability goals, in practice it has largely rejected the idea that sustainability should be directly relevant for the analysis of welfare effects of market conduct.Footnote 81 Thus, it maintains its old line of accepting the relevance of sustainability only when it can be subsumed into parameters of competition such as choice, quality, innovation, etc.

B. Labour rights and protection of workers

Labour rights and the protection of workers have for the most part been absent both from the debate on competition law’s goals and from the practice.Footnote 82 In the EU, this seems to be the result of the Court’s case law. First, in the Albany line of cases, the Court established an exception from the application of competition rules for collective agreements between management and the labour force that are intended to improve working conditions, including pay.Footnote 83 The rationale was that certain restrictions of competition are inherent in collective agreements and as collective agreements are encouraged by the Treaties, competition law should not apply to them to avoid internal conflict. Secondly, the Court also introduced a distinction between workers and non-workers, or employees and self-employed, for the purposes of competition law in its case law. As workers/employees do not fall within competition law’s definition of ‘undertaking’, any agreements between them and an undertaking’s management are not caught by the Article 101(1) TFEU prohibition.Footnote 84 To the contrary, freelancers and atypical workers are not seen as employees, at least if they are genuinely self-employed.Footnote 85 Thus, the exception does not apply vis-à-vis them, creating a risk that their agreements with employers can fall foul of the competition rules, even where they are intended to ensure better pay and working conditions for them.Footnote 86

With the rise of the gig economy and the corresponding increase of freelancers, who, despite their self-employed capacity, are strongly dependent on the platforms they use to match their service offering to potential clients, this binary distinction has appeared increasingly untenable.Footnote 87 Thus, Countouris et al have suggested maintaining the distinction, while making the definition of workers broader to include most self-employed persons.Footnote 88

Another source for the increased debate on the relation between competition law and workers’ rightsFootnote 89 is the proliferating research from the US showing that concentrated labour markets, or monopsony, can lead to anticompetitive conduct. The work of Azar et al,Footnote 90 Eeckhout,Footnote 91 and PosnerFootnote 92 has been quite influential in this regard. The OECD, too, has been active in this area, holding a hearing on the topic.Footnote 93

What has this debate meant for the question of goals? Monti notes that in labour markets, harm to competition can be shown either as reduction in consumer welfare or harm to the competitive process.Footnote 94 This suggests that the goal of protecting workers can be subsumed in the classic goals of EU competition law. Dimick on the other hand sees tackling monopsony power as connected to an efficiency goal, although he accepts that it could be viewed from the perspective of a goal of tackling inequality.Footnote 95

Daskalova notes that the issue of goals remains normatively controversial, as it is difficult to reconcile with the more economic approach.Footnote 96 Discussing the application of Article 102 TFEU to the gig economy, she notes that the logic of exploitative abuse is that competition law exists not only to protect the dominant undertaking’s competitors but also its weaker contractual partners.Footnote 97 Thus, Article 102 can be applied when powerful online platforms impose unfair prices or terms on the self-employed. According to her, ‘there can be no question that EU competition law aims to protect the victims of monopolists and monopsonists’.Footnote 98 In other words, it has the goal to protect workers or weak self-employed persons.

Lianos et al have argued that changes brought about by the Lisbon Treaty and the binding effect of the Charter mean that competition law ought to stop being antagonistic to labour law and instead be used as a tool to strengthen the protection of labour.Footnote 99 This would entail an active application of EU competition law to protect labourFootnote 100 by striking down monopsony conduct that harms labour, such as non-poaching agreements, supplier wage suppression, or the monopsonist orchestrating cartels between supplies to reduce wages.Footnote 101 Marinescu and Posner have also suggested that competition law can be used to tackle practices that harm workers.Footnote 102 Although they do not address the issue of goals directly, this seems to be implied in their approach.

Responding to these developments, the Commission adopted new Guidelines on the application of EU competition rules to self-employed persons.Footnote 103 Broadly, the increased concern for the protection of workers through the application of competition law coincides with a general increase of social protections offered through EU law.Footnote 104 Thus, it seems the Commission’s increasing focus on social rights is slowly translating into a reorientation of the relation between labour law and workers’ rights with EU competition law.

Finally, the literature review revealed an interesting overlap between the discussion of labour rights and workers’ protection with sustainability. For those that understand sustainability in a broad way, the interface between sustainability and competition law includes issues that pertain to labour rights, eg, safe working conditions, fair wages, and elimination of child and prison labour.Footnote 105 This is also now the Commission’s approach in the new Horizontal Guidelines in the special chapter on sustainability agreements.Footnote 106 As we included keywords on labour protections and inequality under this goal, we did not also include them in the sustainability goal.

C. Privacy

With the rise of the data-driven digital economy and the concomitant increase in antitrust enforcement in the sector, privacy and data protection considerations also gradually came to the fore. What is interesting about the role of privacy as a consumer interest in competition law is how unambiguously it was initially rejected by authorities and courts. In the Asnef-Equifax case, where the issue was whether sharing customer data among financial institutions had the effect of restricting competition, the Court declared that ‘since any possible issues relating to the sensitivity of personal data are not, as such, a matter for competition law, they may be resolved on the basis of the relevant provisions governing data protection,’Footnote 107 thereby excluding the protection of personal data from the goals of competition law. Similarly, in the Facebook/WhatsApp merger, the Commission clearly rejected privacy as a goal of competition law stating that ‘any privacy-related concerns flowing from the increased concentration of data within the control of Facebook as a result of the Transaction do not fall within the scope of the EU competition law rules’.Footnote 108 In the US, in the early case of the Google/DoubleClick merger, the FTC also declined to intervene for the sake of privacy grouping it together with other ‘reasons unrelated to antitrust concerns.’Footnote 109

Some of the academic commentary has also taken a negative stance toward bringing privacy under the scope of competition law. Manne and Sperry note that ‘for a product characteristic to be relevant to a competitive analysis, the characteristic itself must be relevant – and it must be logically affected by monopoly in ways that may harm consumers.’Footnote 110 Rejecting the notion that privacy can be linked to competition harm, and lamenting the lack of tools for competition law to address privacy concerns, they conclude that privacy should fall outside the scope of competition law. Kimmelman et al also reserve a very limited role for competition law to play in safeguarding privacy noting again that the antitrust toolbox is not well-suited to tackle privacy concerns.Footnote 111 Alexander, writing for the American Antitrust Institute, sees an even more limited role for antitrust in preserving privacy: she only acknowledges that to the extent that consumers care about privacy, antitrust law can help by preserving the competitive process, so that consumers have more choices, among which choices that preserve privacy.Footnote 112 Differently put, Alexander sees the goal of antitrust as that of safeguarding the competitive process, which will ultimately result in privacy-respecting options.

Another scholarly strand was more accommodating of privacy even though the general message remained that privacy per se should not be a relevant goal. Within this group, the safeguarding of privacy is not recognised separately as a goal of competition law but is linked to other main goals of competition law – notably efficiency and welfare. In an influential contribution, then FTC Commissioner Ohlhausen and then Attorney Advisor Okuliar argued that privacy considerations can be brought under competition law ‘where the potential harm is grounded in the actual or potential diminution of economic efficiency.’Footnote 113 Ohlhausen and Okuliar acknowledge that privacy infringements can harm consumers in different ways, but this only becomes an antitrust law matter when the harm resulting from the privacy intrusion is linked to a reduction of economic efficiency, since the safeguarding of economic efficiency is the main goal of antitrust law. In other words, they subsume privacy under economic efficiency.

Along similar lines, Colangelo and Maggiolino argue that ‘privacy issues may find their way into the antitrust discourse only by verifying that, in some specific markets, consumer welfare strongly depends on goods’ quality and, in turn, this last strongly depends on the levels of privacy guaranteed to users.’Footnote 114 If Ohlhausen and Okuliar’s approach expresses a Chicago School conception of antitrust law (focus on efficiency), Colangelo and Maggiolino’s approach links privacy with the broader goal of consumer welfare, while still, however, maintaining that competition law is not the most appropriate tool.

A more positive line of scholarship openly argues for privacy to be included as a goal of competition law. Interestingly, it often is under the same rationales that other authors have rejected when considering privacy as a proper goal for competition law. As early as 2008, Lande made a similar argument to Alexander, that ‘antitrust is actually about consumer choice, and price is only one type of choice … but consumers also want an optimal level of variety, innovation, quality, and other forms of nonprice competition. Including privacy protection.’Footnote 115 This conception of privacy as a nonprice parameter of competition has been echoed by numerous other authors. Stucke and Grunes acknowledge ‘privacy as an antitrust concern’ noting that it ‘has been recognized as a non-price dimension of competition in the sense that firms can compete to offer greater or lesser degrees,.Footnote 116 This is similar to the approaches of NazziniFootnote 117 and MacCathy.Footnote 118 Meanwhile, Swire, as early as 2007, had subsumed privacy under the ‘principal goal of modern antitrust analysis,’ ie, welfare, and called for it to be considered in at least merger control.Footnote 119

The German Facebook case, whereby the Bundeskartellamt found that Facebook abused its dominant position by combining user personal data it collected across its services, and the subsequent favourable decision by the CJEU responding to the relevant preliminary ruling request, provided new impetus in support of the role of privacy and data protection in competition law. If, up until recently, privacy was mostly considered, at best, as a secondary goal of competition subsumed under welfare or as a non-price parameter, the Facebook case renewed calls for a more ‘integrative’ approach whereby competition law can guarantee ‘a minimum standard of choice for consumers with respect to their decisions about the collection and use of their personal data vis-a-vis firms with market or gatekeeper power.’Footnote 120 We come back to the Facebook case in the next section.

4. Results and analysis

A. Privacy and labour rights are not endorsed as goals; sustainability only partly endorsed as a goal

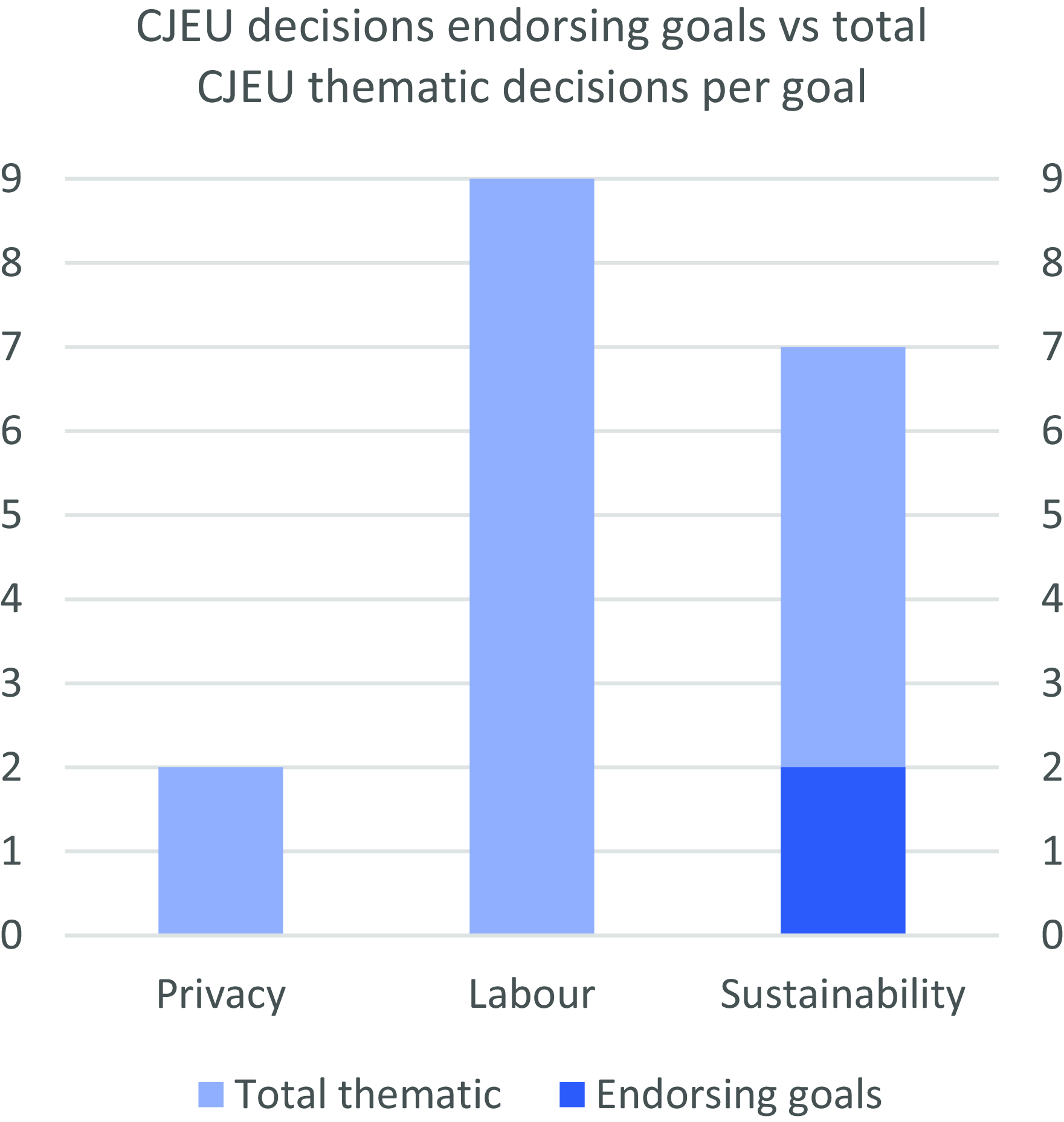

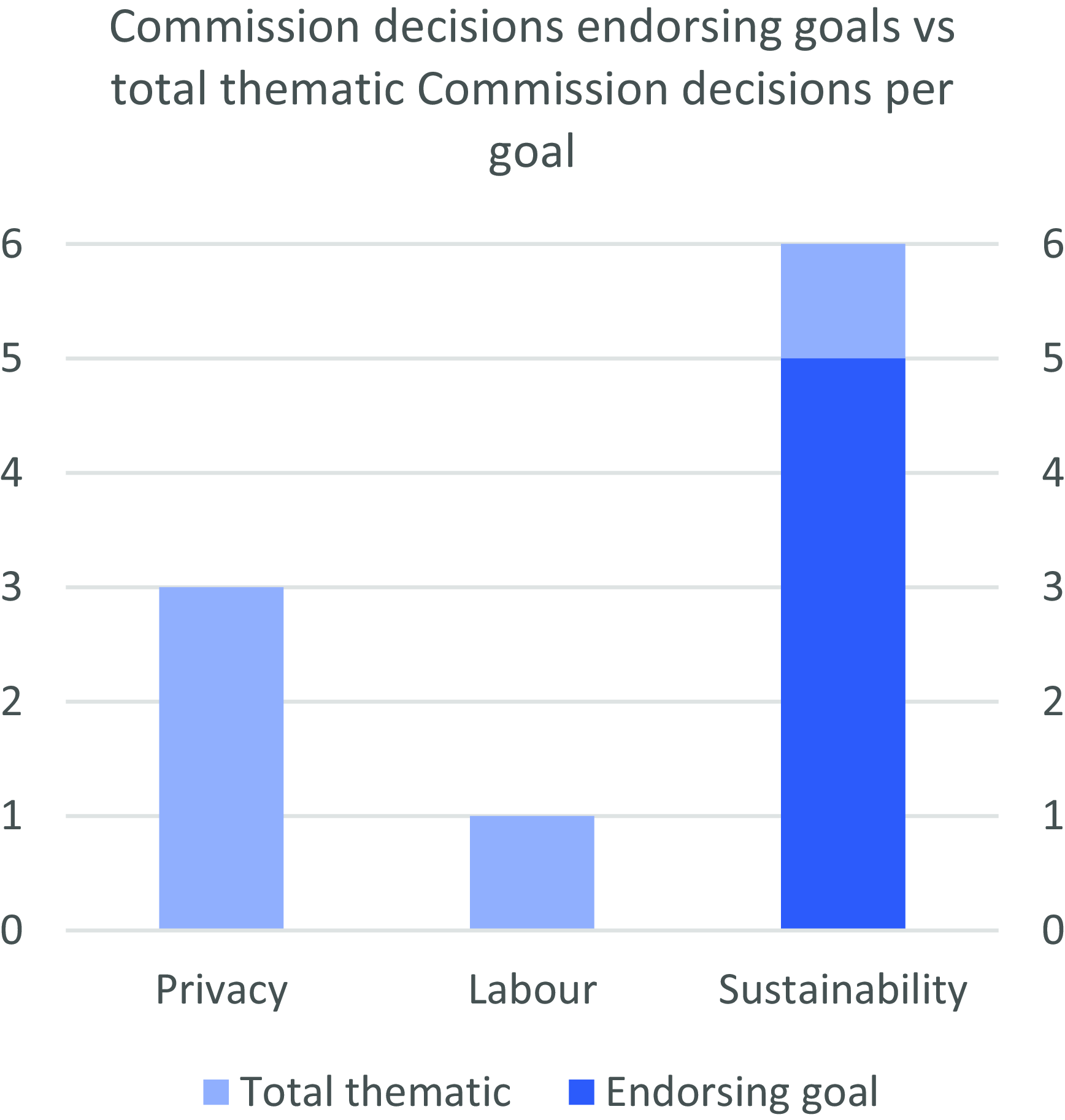

The flagship result from our research is that privacy and labour rights are not recognised as goals of competition law by the Court, AGs, or the Commission, while sustainability is recognised by the Commission and to a lesser extent by the Court and AGs. We base those results on the ratio of decisions and opinions that recognise these as goals of competition law to the total decisions and opinions that thematically fall within those areas (see Rule 7). Rule 7 requires us to identify the population of sources wherein the studied goals could indeed arise, not within the general population of all sources, because that would not be instructive. In detail, as it appears in Figures 1–3, we did not identify a single CJEU decision, AG opinion or Commission decision (respectively) that recognises privacy or labour rights as goals of competition law among decisions and opinions in which these thematic areas come up.Footnote 121 On the other hand, when it comes to sustainability, the Commission took almost every opportunity to endorse it as a goal (83 per cent), whereas the CJEU and AGs endorsed it at a rate of 29 per cent and 57 per cent respectively. Evidently, only sustainability can be said to be a new goal of EU competition law, and even that not fully accepted by the CJEU and AGs.

Figure 1. Stacked view of CJEU decisions touching on privacy, labour, and sustainability (light blue), and CJEU decisions that endorse those areas as goals of competition law (dark blue).

Figure 2. Stacked view of AG opinions touching on privacy, labour, and sustainability (light blue), and AG opinions that endorse those areas as goals of competition law (dark blue).

Figure 3. Stacked view of Commission decisions touching on privacy, labour and sustainability (light blue), and Commission decisions that endorse those areas as goals of competition law (dark blue).

The discrepancy between sustainability on the one hand and labour rights and privacy on the other hand might be explicable based on their different status under the Treaties. Currently, the relevant horizontal provisions on sustainability, labour, and privacy policies are found inter alia in Part 1, Title II of the TFEU which contains ‘Provisions of general application’ and in the individual Chapters that deal with each EU competence respectively. For labour rights, the relevant provision is Article 9 TFEU, which holds that ‘[i]n defining and implementing its policies and activities, the Union shall take into account requirements linked to the promotion of a high level of employment, the guarantee of adequate social protection, [and] the fight against social exclusion…’ Article 16 TFEU concerns the protection of personal data. Its first paragraph holds that ‘[e]veryone has the right to the protection of personal data concerning them’ whereas the second paragraph tasks the European Parliament (EP) and the Council with legislating to protect the processing of individuals’ personal data.

For environmental protection, Article 11 TFEU holds that ‘[e]nvironmental protection requirements must be integrated into the definition and implementation of the Union’s policies and activities, in particular with a view to promoting sustainable development.’ Considering Article 11 TFEU together with the similarly phrased Article 37 of the Charter and with Articles 7, 8, and 191 TFEU as well as Article 3(3) TEU, Iacovides and Vrettos have argued that ‘EU primary law sets forth a constitutional imperative on the EU to integrate environmental protection and sustainability in all its policies. The consequence of that is that not only can EU competition policy enforcement not pursue goals that are inconsistent with sustainability goals, but must also, as a matter of EU constitutional law, positively pursue them and integrate them in its goals.’Footnote 122 Their argument is based on the idea that primary EU law imposes a so-called ‘mainstreaming obligation’ on EU institutions, that is to say a duty to promote compliance with the relevant fundamental right obligation derived from the Charter.Footnote 123

One can contrast the sustainability provisions with those on labour and privacy, which may explain the difference in treatment of the goals by the CJEU and the Commission. Regarding requirements relating to a high level of employment, social inclusion, and adequate social protection, Article 9 TFEU only instructs the Union to ‘take them into account’. This can be contrasted to Article 11 TFEU which asks requirements relating to environmental protection to be integrated into the definition and implementation of the Union’s policies and activities. When it comes to privacy, Article 16(1) TFEU is an iteration of a right conferred on individuals and, thus, does not correspond to Article 11 TFEU, whereas Article 16(2) TFEU is programmatic in nature instead of self-executing, instructing the legislator to adopt legislation to protect privacy.

The above explanation is consistent historically too. While the provisions on environmental protection and sustainable development have remained practically unchanged,Footnote 124 the same cannot be said about provisions on labour rights and privacy, which were even weaker in the past. For one thing, there was no equivalent of Article 9 TFEU in previous versions of the Treaty. Even the policy on ‘Social provisions’ in the Single European Act of 1986, which touches on labour rights and conditions was a coordinating one, ie, neither exclusive nor shared.Footnote 125 That said, the policy has included since the SEA an article instructing the Commission to endeavour to develop the dialogue between management and labour at European level, which could lead to relations based on agreement.Footnote 126 This article was referred to in the seminal Albany case, both by AG Jacobs and the CJEU, as demonstrating that the conclusion of collective agreements is encouraged by EU law and therefore there is an assumption that they are in principle legal.Footnote 127 The existence of the article was also one of the arguments for why collective agreements should fall outside the scope of Article 101(1) TFEU.Footnote 128 At the same time, regarding privacy, the previous version of Article 16 TFEU bears almost no resemblance to the current one, as it only extended the applicability of acts of the European Community (EC) on the protection of individuals regarding the processing of personal data to the institutions set up by the TEC. No other provisions in the TEC and the EC accorded any specific competence to legislate in data protection and privacy.

B. Sustainability, labour rights, and privacy are not frequent topics/themes in the competition law work of EU institutions

Both the total number of decisions and opinions that thematically relate to the new goals (see Rule 7), and the total number of decisions, opinions, and speeches that endorse new goals are low as a matter of absolute numbers. This shows that the thematic areas of sustainability, labour rights and privacy are not widely discussed in EU competition law. Strikingly, even when they do emerge, it is most often in speeches, not in the decisional practice. The low number of occurrences is a valuable insight in itself, as it can be interpreted either as lack of competition law enforcement in these areas, or that these areas do not give rise to competition law issues. Either way, the academic community’s fascination with competition law’s role in these areas seems to be out of pace with actual practice.

In total, there were 48 CJEU decisions, Commission decisions, and AG opinions in the thematic areas of sustainability, labour rights, and privacy. We did not count speeches by thematic area as speeches are inherently less focused than decisions and opinions and transcend themes making their thematic classification too subjective. Considering that the total number of CJEU decisions, Commission decisions, and AG opinions that we searched was 3,511 sources, it is evident that the themes of the new goals are rather marginal.

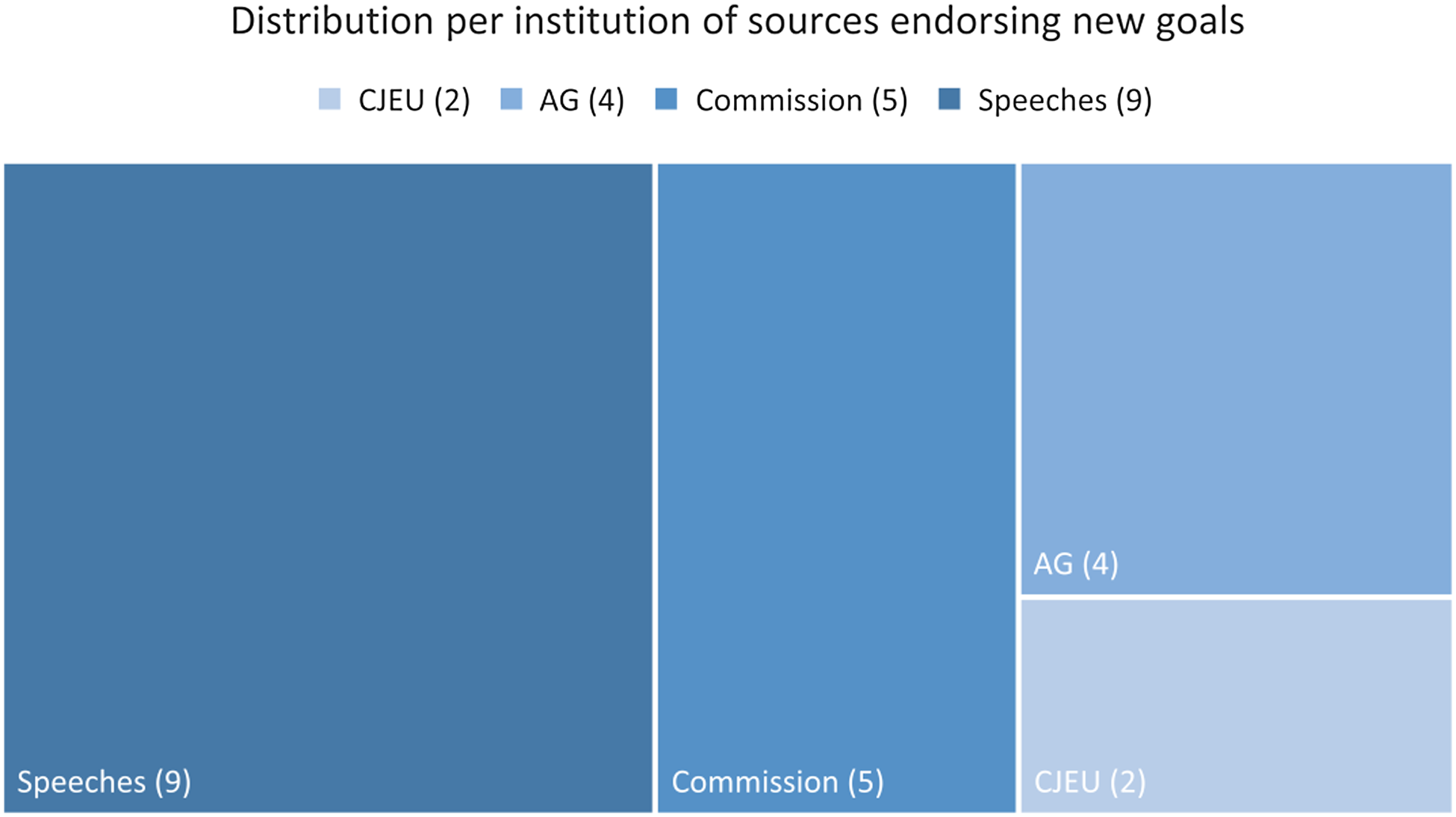

We then turned to the sources endorsing sustainability, labour rights, and privacy as goals (as opposed to simply being in the relevant thematic area). We identified a total of 20 sources, including speeches (Figure 4). In fact, of that total number, almost half (9 out of 20) are speeches, and of the remaining ones, five are Commission decisions, four are AG opinions, and two are CJEU decisions (Figure 5). Of those, 18 related to sustainability, one related to labour rights, and one related to privacy (Figure 6). Excluding speeches and AG opinions and focusing only on the binding decisional practice of the CJEU and the Commission, there are only seven cases that endorse sustainability as a goal of EU competition law, and none that endorses labour rights or privacy. In all, similar to the low numbers of sources falling in the thematic area of the new goals, there is accordingly an even smaller number of sources that endorse the new goals (but see also Section 4.C) on a potentially increasing trend).

Figure 4. Combined yearly distribution of decisions, opinions, and speeches endorsing the new goals 1964–2022.

Figure 5. Distribution of decisions, opinions, and speeches endorsing new goals by institution.

Figure 6. Distribution of decisions, opinions, and speeches endorsing new goals by goal (across institutions).

C. Sustainability, labour rights, and privacy, either as themes or as goals, are new, as they are concentrated in the post-2000s era

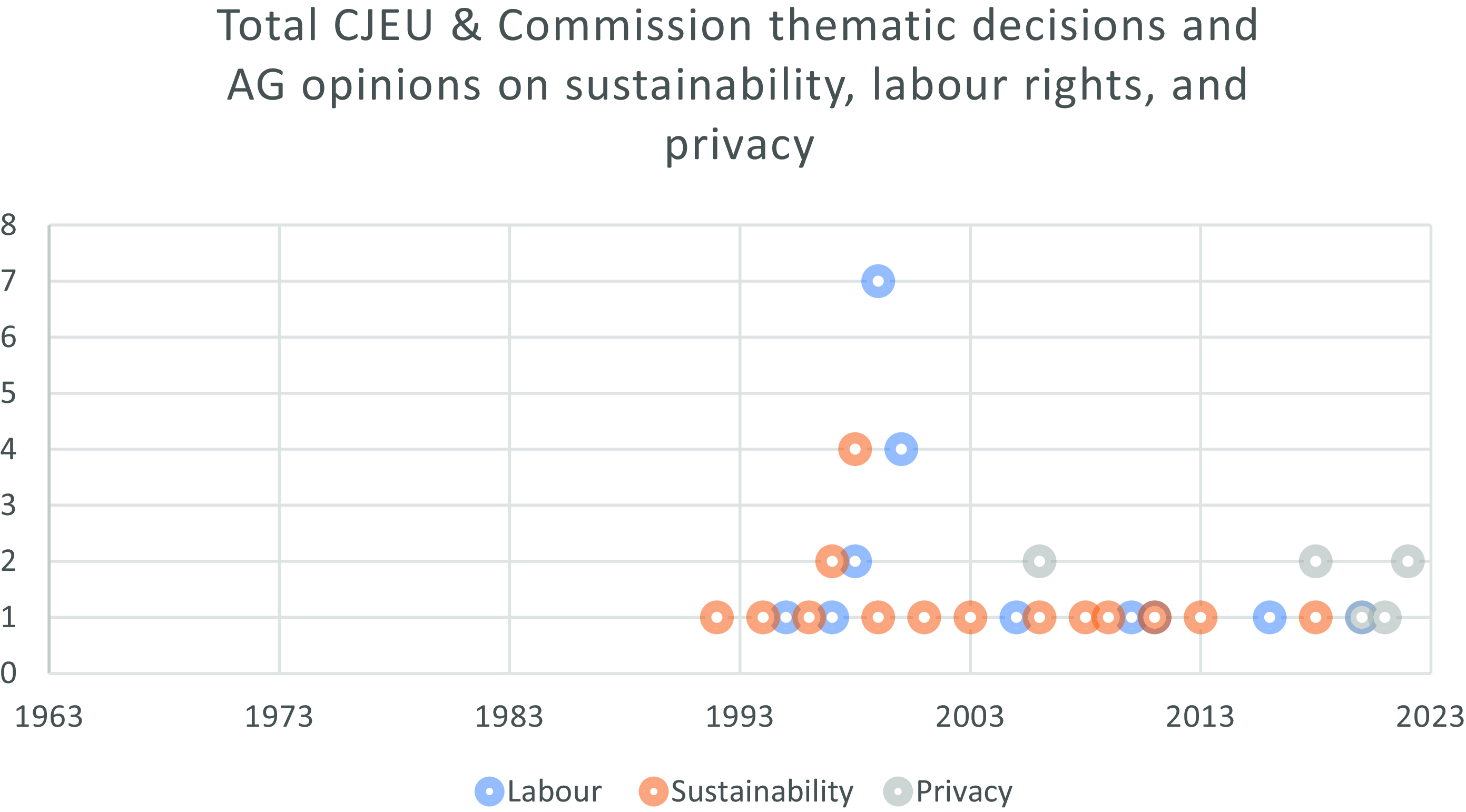

Putting aside their limited endorsement as relevant goals of competition law, a clear observation is that sustainability, labour rights, and privacy emerge as truly recent in EU competition law’s evolution. Our first result appears in 1992, and results occur more frequently after 2005 (Figure 8). This mostly applies to sustainability and seems to point to a shift in the last 30 years of EU competition law practice. In our previous study, we showed a historical stability of references to the more traditional EU competition law goals from the early years to 2021.Footnote 129 Based on the fact that the three new goals investigated here show a concentration in the last two decades, an argument can be made that they are indeed a feature of more modern competition law. While we suspected this may have been the case, early decisions (eg Assurpol in sustainability)Footnote 130 and opinions (eg Bosman in labour rights, Diego Calí in sustainability)Footnote 131 reasonably raised expectations that the three studied goals extend further back historically than commonly assumed. Because our methodology was data-driven, ie we did not set out to test a specific hypothesis, including as to how recently the three studied goals emerged, searching from the beginning of EU institutional practice was necessary to ascertain if and when the studied goals emerged.

The temporal concentration of the new goals in the last two decades is somewhat at odds with the prevailing narrative that the post 2000s era is characterized by the ‘more economic approach’ to EU competition law, which emphasizes economic analysis of competition law, and as a corollary de-prioritizes alternative goals that deviate from the economically-oriented protection of the competitive process.Footnote 132 One might have expected alternative goals (such as sustainability, labour rights, and privacy) to feature either more prominently before the switch to the more economic approach or at least at the same rate after the switch. However, recall that the EU did not have specific social or environmental policies until the SEA Treaty (1987) and still does not have a specific policy on privacy. Without a solid claim of competence in these areas, it would be difficult for EU institutions to assert that the purpose of competition law was to safeguard them. Moreover, horizontal provisions on these areas were introduced even later, with the one on the environment coming into force with the Treaty of Amsterdam (1997) and the ones on privacy and labour with the Lisbon Treaty (2009).

Additionally, endorsements of sustainability, labour rights, and privacy could not have arisen earlier anyway, because the cases that concerned these areas thematically are also concentrated in the last 25 years. As it can be seen in Figures 7 and 8, most cases touching on sustainability are concentrated between 1995 and 2004, labour rights between 1996 and 1999, and privacy even more recently between 2005 and 2022. It is possible that societal awareness at least as regards the importance of sustainability and privacy and how these infiltrated economic activity, and therefore the extent to which they could arise in competition law cases, were not as developed until about 30 years ago. Hence, the possibility that they could have informed the very goals and purposes of competition law before seems unrealistic.

Figure 7. Annual distribution of combined CJEU decisions, AG opinions, and Commission decisions concerning (not necessarily endorsing) sustainability, labour rights, and privacy 1964–2022.

Figure 8. Annual distribution of total number of CJEU decisions, AG opinions, and Commission decisions concerning (not necessarily endorsing) sustainability, labour rights, and privacy 1964–2022.

D. There appears to be a disconnect between rhetoric (speeches) and decisional practice (CJEU & Commission decisions, AG opinions)

Comparing speeches and decisions/opinions, there does not seem to be much alignment. As regards sustainability, the Commission has issued five decisions and seven speeches endorsing it (a seeming alignment), but the decisions predate the speeches, with most decisions concentrated between 1998 and 2003, and most speeches concentrated between 2016 and 2021 (ie, delivered by Commissioner Vestager) (Figure 9). Therefore, it cannot be said that the Commission’s rhetoric on sustainability has led to a change in institutional practice, whether its own or of the CJEU or AGs. The opposite cannot be said either, considering the large 10+ year time difference. If the CJEU or AGs came out in support of sustainability as a goal, one would expect the Commission to jump on the opportunity to publicize (through speeches) the endorsement as soon as possible. We are bound to conclude that Commissioner speeches and CJEU/AG workings moved independently from each other.

Figure 9. Five-year increment of Commission decisions and speeches endorsing sustainability as a goal. Decisions are concentrated before 2003, whereas speeches are concentrated after 2016, and therefore do not seem interconnected.

This finding is reminiscent of the push for fairness as a goal of competition law by Commissioner Vestager, which, according to our previous study, was also not reflected in the decisional practice, despite frequent mentions in her speeches.Footnote 133 That said, we make this latter juxtaposition cautiously; due to sustainability’s more recent emergence compared to fairness, perhaps going forward sustainability will be met with greater approval as a goal than fairness.Footnote 134 Relevant here is also a conclusion from the previous study that prior decisional practice and external forces such as academic commentary do not seem to have consistent influence on future cases.Footnote 135 If one is inclined to consider speeches as external influence, then it is not surprising that public facing rhetoric does not trickle down to institutional practice.

Regarding privacy and labour rights, only tentative suggestions can be made due to the limited results. With only one speech endorsing privacy and one labour rights as goals of competition law (both after 2016), but no CJEU decisions, AG opinions, or Commission decisions endorsing them, there is again a mismatch between (the admittedly minimal) rhetoric and practice.

E. Sustainability, labour rights, and privacy are entering competition law through different back doors

Despite their limited role so far, sustainability, labour rights, and privacy are gradually infiltrating competition law – but each in a different way. The perusal of the entirety of EU’s decisional practice and rhetoric on competition law allowed us to detect patterns of how sustainability, labour rights, and privacy develop claims as relevant goals of competition law, even if they have not yet found widespread acceptance. We make no evaluative judgements on these patterns. We merely expose them because, if these goals are to find greater acceptance, it is likely that they will do so through the patterns we reveal.

When it comes to sustainability, in one strand of the case law, protecting the environment is seen as a State task that is not of an economic nature, and therefore excludes the application of competition rules, similarly to workers’ rights.Footnote 136 In another strand of the case law, sustainable development is considered an EU goal that connects to the creation of the internal market and cuts across policies and must, thus, be pursued by competition law. The bridging provision is Article 3(3) TEU, which is referred in the cases as support for internal market law, including competition law, to promote sustainable development.Footnote 137 No conflict is identified between sustainable development and competition policy in this regard.Footnote 138 Notably, Article 3(3) TFEU does not only refer to the EU having to ‘work for the sustainable development of Europe’. It adds that it should aim at, inter alia ‘a high level of protection and improvement of the quality of the environment’. Thus, the logic that connects competition policy to sustainability could have been applied to environmental protection too. What does the distinction in the case law rest upon then? In our view, it must be a belief that whereas sustainability can be (also) delivered by markets, environmental protection is an outcome to be delivered by States (or the EU) through regulation. As put by AG Maduro in FENIN, the Court has ‘exclude[ed] from the scope of competition law tasks in the public interest such as … the protection of the environment, as those activities are considered to form part of the essential functions of the State. More generally, all cases which involve the exercise of official authority for the purpose of regulating the market and not with a view to participating in it fall outside the scope of competition law’.Footnote 139

This distinction between environmental protection and sustainability at large is however not present in the Commission’s decisions or speeches from Commissioners for Competition. In its decisional practice, the Commission accepts that environmental protection can be achieved by undertakings in ways relevant to competition law. The link is innovation,Footnote 140 or even conformity with legislative requirements through otherwise anti-competitive practices.Footnote 141 In the speeches, environmentally friendly products, sustainability, and addressing climate change are all invariably seen as outcomes of green innovation, efficiency, propelled by consumer demand.Footnote 142 Thus, there is no necessity to connect the goal to the EU’s goals, as the Court has done. Interestingly, the Commission’s approach is more recent than the Court’s. We identify this as the seeds of an emerging motif, subject to the Court’s endorsement, in how sustainability may enter competition law as a goal. Indeed, this approach seems to be gaining further traction on the policy side, most prominently in the new Guidelines on horizontal agreements, where the Commission clarifies that it considers sustainability goals – which include environmental protection – to justify exceptions from competition rules even in the presence of State regulation.Footnote 143

Labour rights present two motifs. First, numerous CJEU and Commission decisions and AG opinions note that since the Treaty encourages collective bargaining, competition law does not apply in such situations because if it did, it would create an obstacle to the realisation of the Treaty mandates. In the words of AG Jacobs ‘[t]he authors of the Treaty either were not aware of the problem or could not agree on a solution. The Treaty therefore does not give clear guidance. … Since both sets of rules are Treaty provisions of the same rank, one set of rules should not take absolute precedence over the other and neither set of rules should be emptied of its entire content. … Accordingly, collective agreements between management and labour on wages and working conditions should enjoy automatic immunity from antitrust scrutiny.’Footnote 144 Therefore, as regards labour rights, competition law helps through forbearance, not through active recognition. Labour rights are not goals of competition law, but of the Treaty, and competition law supports them by declaring itself inapplicable when its applicability would result in their curtailment.

But there is an additional emerging motif as well. In various speeches, labour rights are linked to fairness, and it is through that lens that they are brought within the protective scope of competition law. In one of her 2022 speeches, Commissioner Vestager mentioned ‘the concept of fairness as applied to competition policy is well recognised … Fairness is what motivated us to take a look at the working conditions of the solo self-employed’. In another speech from 2016 she said ‘inequality between the poorest and richest in our societies is growing … As competition authorities, we do not have magic solutions. But we can do our bit: to help create fair conditions in markets.’ It is clear that such public statements do not suffice to declare that labour protections are a goal of competition law, but they do give an indication of how they might eventually come into the picture: through fairness, at the very least where inequality or worker exploitation are involved. Whether fairness is a goal of competition law itself is a separate question, which we investigated in our previous study.Footnote 145

As regards privacy, the indications are even more muted, but they hint towards treating privacy as a non-price parameter of competition, and therefore consumer welfare. Until very recently, privacy and data protection considerations were expressly reserved for bodies of law other than competition law, chiefly data protection legislation like the GDPR.Footnote 146 But in the Google Android case, the Court treated the protection of privacy as a qualitative parameter of competition that concerns consumer welfare, a well-recognised goal of competition law.Footnote 147 Interestingly, Commissioner speeches hinted to this eventuality in a gradual manner. Commissioner Almunia first made a reserved statement in 2012 that ‘DG Competition has yet to handle a case in which personal data were used to breach EU competition law. But we cannot rule out this eventuality.’Footnote 148 Then, Commissioner Vestager mirrored that approach in 2016: ‘So I don’t think we need to look to competition enforcement to fix privacy problems. But that doesn’t mean I will ignore genuine competition issues just because they have a link to data.’Footnote 149 She followed up with a more direct endorsement in 2019: ‘The point of competition is to give consumers the power to insist on the kind of service they want. And if privacy is something that’s important to consumers, competition should drive companies to offer better protection.’Footnote 150 While none of the statements make privacy a goal of competition law today, they signal a gradual warming up of competition law toward it, and how it may eventually find greater acceptance as an objective that competition law seeks to protect.Footnote 151

In a major recent development, the Facebook decision by the CJEU has been widely seen as bringing privacy under the scope of competition law. The decision is not included in our study, because it is outside the temporal scope and because it is not a competition law decision. The case is classified under ‘Principles of EU’ in the Curia database, and correctly so since the preliminary ruling questions referred to the Court were on the interpretation of Article 4(3) TEU and the GDPR, not on competition law.Footnote 152 In the relevant part of the decision the Court ruled that ‘Article 51 et seq. of the GDPR and Article 4(3) TEU must be interpreted as meaning that … a competition authority of a Member State can find, in the context of the examination of an abuse of a dominant position by an undertaking within the meaning of Article 102 TFEU, that that undertaking’s general terms of use relating to the processing of personal data and the implementation thereof are not consistent with that regulation, where that finding is necessary to establish the existence of such an abuse.’Footnote 153 In other words, the decision authorises competition authorities to make a finding of violation of the GDPR if that is necessary to ascertain abuse of dominance and clarifies that holding a dominant position is an important factor when deciding whether consent to the processing of certain data can be given freely by consumers within the meaning of the GDPR. It does not concern itself with the role of privacy in competition law, let alone recognize it as a goal.

5. Conclusion

In their day-to-day work, practicing competition lawyers need seldom reflect on what competition law and policy is really for. In the times that followed the ‘end of history’Footnote 154 and under the hegemony of the Chicago school in US antitrust, the predominant way in which competition law has been applied the last few decades in most major jurisdictions, including the EU, has not invited deep philosophical musings. The bread and butter of competition lawyers – whether they work for competition enforcers, law firms, or companies – is prices, outputs, quality, innovation; in short what we have come to call ‘consumer welfare’. It is the norm for competition lawyers to think of competition law and policy as a tool that can be applied objectively based on economics, instrumental to achieving certain market outcomes that are considered positive but devoid of exogenous interferences. Yet, as we showed already in our previous research, competition law and policy pursue a multitude of goals in parallel, meaning that it is always possible to adapt the application of the policy to the needs of the times (eg, a push to complete the internal market) or to current perceptions of what is just, or what are acceptable ways to compete on markets.

The research we undertook for the purposes of this paper reinforces that idea, as we zoomed in on goals that are new and, thus, aligned with current debates, legal and political, as to how markets deliver, or fail to deliver, outcomes that are considered important: sustainability, protection of labour vis-à-vis digital giants, privacy. Overall, looking at the data that has come out of this comprehensive empirical research and the five major conclusions stemming from our analysis of that data, the key takeaway is that sustainability is partially recognised as a goal of EU competition law in cases and decisions whereas privacy and labour rights are not. Yet, as all three goals are more recent than classic goals, we can expect the frequency of cases that have to deal with them to increase and the rhetoric and political discourse to translate into more engagement with the goals in the binding legal sources. In that regard, our analysis of the cases reveals certain motifs that would allow for these three values to be recognised as competition law goals, either because they are seen as non-price-based competition parameters, or because they relate to broader Treaty goals that are themselves currently under significant development, for instance fairness or sustainability.

Explicitly recognising these goals as competition law goals would have significant implications for competition law and policy. It would mean at the very least that any market behaviour and potential mergers and joint ventures could potentially be scrutinised – to the extent relevant – as to how they affect, positively or negatively, sustainability, labour rights, and privacy. These actual or potential effects would have to be weighed up against effects on more traditional goals of EU competition law such as consumer welfare, efficiency, and internal market integration. This, in turn, would require the right kind of human resources and competencies at the Commission, NCAs, and eventually courts. Given competition law’s normative force and grave repercussions for breaching it, companies would have to adjust their behaviour accordingly.Footnote 155 A competition policy that explicitly accepts sustainability, labour rights, and privacy as goals to be pursued through it, would also better align with EU legislation on these matters, such as Green Deal related legislation, the DMAFootnote 156 and the GDPR,Footnote 157 filling in gaps in enforcement and further shaping business conduct.

Competition policy is one of a select few policies where the EU has exclusive competence.Footnote 158 The EU’s powers in enforcing the policy are significant. What happens in competition policy matters, even though generations of EU lawyers have learned to examine the nature of the EU and its economic constitution mostly through internal market and more specifically free movement law. Thus, although our conclusions may seem modest, they are nonetheless tremendously important, as they reveal the tectonic shifts that are happening not only in competition law but in EU law in general. They confirm first and foremost how the EU of today is not the free trade project of the past. They also demonstrate that the EU has the capacity to respond to crises of our time through the application of generalist tools, like competition policy, for regulating the conduct of market participants to achieve outcomes that are desirable by its citizens.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank two anonymous reviewers, participants at the ASCOLA annual conference in Athens in July 2023, and David Stewart (Towerhouse LLP) for feedback and useful comments on drafts of this paper. All errors and omissions remain the authors’.

Funding statement

None.

Competing interests

The author has no conflicting interests to declare.