In Representation at Risk, Håkansson and Lajevardi investigate the levels and consequences of violence against immigrant-background politicians in Sweden. Using a large-scale survey of Swedish elected officials, they find that politicians with immigrant backgrounds face higher rates of violence than their counterparts without immigrant backgrounds. This violence occurs both online and offline. Moreover, it has political consequences: those targeted are more likely to consider leaving politics, threatening the democratic representation of an already underrepresented group. These findings raise urgent concerns about political inclusion, highlighting how violence may serve as an additional barrier for minorities in elected office.

Håkansson and Lajevardi begin by engaging with multiple strands of research. Previous work has demonstrated that politicians face violence at levels comparable to or exceeding those found in other high-risk occupations. Scholarship has also emphasized that women politicians are disproportionately targeted, particularly with online harassment and threats. However, while we know much about violence against women politicians, much less is known about violence against immigrant-background politicians. Theoretically, the authors build on intersectionality theory, which suggests that individuals with multiple marginalized identities such as women of color will face heightened risks of discrimination and exclusion. They also draw from research on minority political representation, which has shown that immigrant-background politicians are often viewed as outsiders, making them more vulnerable to violence.

The authors focus on Sweden. Despite its reputation for egalitarian politics, immigrants remain underrepresented in elected office and often face barriers to political participation. Additionally, Sweden is similar to other Western democracies with growing immigrant populations and rising anti-immigrant rhetoric. The authors rely on survey data that captures experiences of political violence among Swedish municipal politicians, covering various forms of violence:

-

• Bodily violence (e.g., physical attacks)

-

• Property damage (e.g., vandalism, arson)

-

• Threats (e.g., death threats, threats to family)

-

• Harassment (e.g., stalking, online abuse)

-

• Character assassination (e.g., spreading false or defamatory information)

Notably, the survey includes all elected officials in Sweden. The authors define “immigrant-background politicians” as those who are either foreign-born or have at least one foreign-born parent, and compare the experiences of immigrant-background politicians to their non-immigrant counterparts while accounting for other factors like gender, age, political experience, and party affiliation.

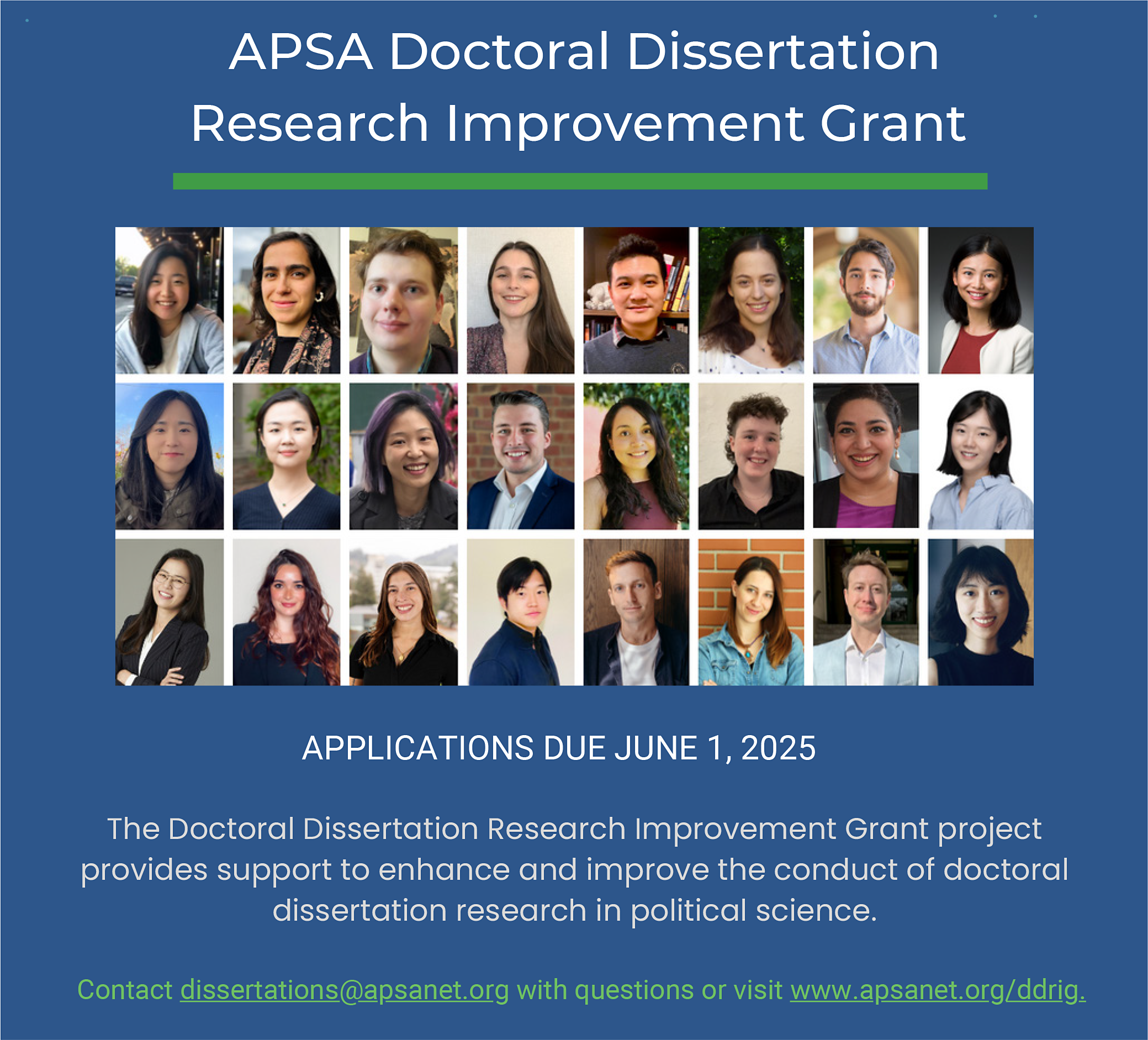

Mihajlo Maricic/Getty Images

Across all forms of violence examined, immigrant-background politicians report higher levels of victimization, with the largest gaps found for threats and harassment. Notably, immigrant-background politicians are also more likely to experience multiple types of violence simultaneously, making their political careers even more precarious. However, no significant difference is observed between first-generation and second-generation immigrants in levels of violence, which suggests both are perceived as political outsiders. Secondly, regarding gender variation, while both men and women with immigrant backgrounds face more violence than non-immigrant counterparts, the patterns differ. Men with immigrant backgrounds are more likely to experience property damage, threats, and character assassination than non-immigrant men. Meanwhile, women with immigrant backgrounds are more likely to experience harassment and threats than non-immigrant women. An additional and particularly troubling finding is that violence seems to have a chilling effect. Immigrant politicians are more likely to consider leaving politics due to violence than their non-immigrant peers, and this effect is even stronger among those who have already experienced violence and, again, women with immigrant backgrounds face the highest risks.

What, then, do these findings mean for our ideas of democracy and representation? Political violence disproportionately targeting immigrant-background politicians increases existing barriers to representation. Even after overcoming hurdles to gain political office, these politicians face ongoing threats that make it harder for them to remain in power. As minority politicians already face discrimination in candidate selection processes, the additional burden of violence means that even those who secure elected office may be pushed out, further marginalizing their communities. Moreover, research has shown that minority politicians often champion policies that benefit marginalized groups. If they are disproportionately driven out by violence, entire communities may lose political voice and influence. That women with immigrant backgrounds face the greatest pressure suggests these attacks and their effects may compound other disadvantaged groups in tandem and may deter future candidates from running.

Together, Håkansson and Lajevardi’s study underscores a critical but often overlooked reality: political violence is not just a problem of security, but a threat to democracy and democratic representation itself. As immigrant-background politicians enter political institutions, ensuring their safety is paramount, not only for individual well-being but for the health of democracy as a whole. ■