INTRODUCTION

When the world experiences its largest democratic experiment in over 50 years, there are bound to be some surprises. If India was the biggest new democratic surprise of the post-World War II era—both demographically and theoretically speaking—that status in the post-Cold War era belongs to Indonesia. It has now been nearly 20 years since Suharto's long-ruling dictatorship (1966–98) fell from power, and his presidential successor B. J. Habibie began laying the groundwork for the largest democracy in the Muslim world, and the third-largest democracy on Earth. Indonesia has literally changed the map of the democratic world.

The sheer scale of Indonesia's experience invites us both to look for new answers to old questions about democracy, and to ask new questions about democracy altogether. This essay asks three interrelated questions that are rarely asked in political science, but that the Indonesian case suggests we might need to ask with greater frequency and urgency. First, how does opposition emerge as a political process in newly democratic settings? Second, how do democratically elected presidents share power and build ruling coalitions? And third, how might new political rules reshape those power-sharing practices? These three questions—the questions of 1) opposition emergence, 2) presidential power-sharing, and 3) institutional effects—might at first appear unrelated. But they have converged in Indonesia in an unanticipated manner, making them amenable to simultaneous engagement through a single, theoretically motivated case-study.

In brief, I argue that the development of a clearly identifiable political opposition in democratic Indonesia has been hindered by promiscuous power-sharing: “an especially flexible coalition-building practice in which parties express or reveal a willingness to share executive power with any and all other significant parties after an election takes place, even across a country's most important political cleavages” (Slater and Simmons, Reference Slater and Simmons2013).Footnote 1 Promiscuous power-sharing lies at the heart of an enduring democratic dysfunction that I call party cartelization, Indonesian-style.Footnote 2 If parties share power much more widely and promiscuously than expected, the emergence of democratic opposition becomes much more contingent than expected. This scuttling of opposition has deleterious implications for “vertical accountability” and policy responsiveness between voters and politicians (O'Donnell Reference O'Donnell1994; Slater Reference Slater2004; Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2007; Gottlieb Reference Gottlieb2014).

The analysis to follow will be much more focused on the “how” of promiscuous power-sharing and opposition failure than the “why.” Explaining why this outcome came about in Indonesia runs smack into a fundamental obstacle of causal inference: the degrees-of-freedom problem. Not only is Indonesian party cartelization a single outcome that plausibly could be explained by multiple causes, and is thus “overdetermined” (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2013, 286). Party cartelization itself is a rare outcome, especially at the extreme levels sometimes witnessed in Indonesia, leaving little potential for gaining cross-case comparative leverage.Footnote 3

Instead of explaining the outcome of opposition failure, therefore, I aim to explain its surprising persistence—while also charting its undeniable evolution—by specifying why it constitutes a strategic (if shaky) equilibrium. Promiscuous power-sharing is strategically optimal for political parties in Indonesia's parliament because it allows them to maintain privileged access to state patronage, even when they fare miserably in national parliamentary elections (Slater Reference Slater2004). This is the much less surprising half of the power-sharing bargain. The more puzzling half is that presidents persistently find strategic advantage in building coalitions that are not just oversized, but at times include every single significant party, wiping out party opposition entirely in the process. This essay's conclusion offers some preliminary thoughts on why Indonesian presidents do not adopt anything remotely resembling a “minimum winning coalition” logic (Riker Reference Riker1962). To foreshadow: the core intuition is that building wider coalitions does not mean presidents have to share more of their own power or resources. It means each party in the coalition has to share more of theirs. Power-sharing may make directly elected presidents relatively stronger, not weaker absolutely.

Where the singular case of Indonesia offers the greatest opportunity for explanatory leverage is in assessing the importance of formal political institutions in shaping opposition failure. Party cartelization originated in Indonesia under a particular and somewhat peculiar set of rules. Most importantly, parliament rather than the people selected the president in Indonesia's founding national elections of 1999, as well as in the parliamentary impeachment of Indonesia's first democratically elected president in 2001. Since Presidents Abdurrahman Wahid (1999–2001) and Megawati Sukarnoputri (2001–04) were both appointed by parties in parliament, those parties enjoyed golden opportunities to impose power-sharing quid pro quos.

The introduction of direct presidential elections in 2004 seemed likely to produce a variety of pronounced institutional effects. One would be encouraging a new model of presidential power-sharing. If presidents are selected directly by the people, parties should have less leverage, ceteris paribus,Footnote 4 for extracting cabinet seats and other power-sharing concessions from the chief executive. In principal-agent terms, direct elections make voters rather than parliamentarians the primary principal, even when presidential candidates must strive to secure a party nomination, as they do in Indonesia. This implies that presidents should act more like the agent of voters than of parliamentarians when selected by the people instead of by fellow elites (Samuels and Shugart, Reference Samuels and Shugart2010).Footnote 5 For promiscuous power-sharing to persist under pure presidentialism, it would not be enough for patronage-hungry parties in parliament to demand it. Newly empowered presidents would need to desire it.

Twelve years and three direct presidential elections later, can we conclude that new rules have produced a new democratic power-sharing game in Indonesia? This is the core causal question that animates this article. We should indeed conclude that the power-sharing game has changed if presidents are 1) sharing power selectively with parties that share their general ideology, background, or worldview; 2) forging coalitions before presidential elections and maintaining them once the electorate has chosen one coalition over another; 3) retrospectively expressing the will of Indonesia's electorate by sidelining parties with plummeting popularity at the stage of government formation; while also 4) prospectively accepting that a viable party opposition should exist to replace the government in future elections if it performs badly, by leaving at least one major party outside of government. Conversely, we should decipher more continuity in the power-sharing game if presidents are still expressing openness to pursuing alliances across the board, regardless of compatibility considerations; sharing power with parties that voters have just punished at the ballot box; and more generally casting aside their coalitional commitments once the electoral dust has settled.

Assessing Indonesian power-sharing dynamics along these dimensions is far from straightforward, and has been subject to competing interpretations. How we assess these dynamics holds serious implications for whether we see party cartelization as a temporary aberration that predictably went away once Indonesian democracy gained its footing (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2013);Footnote 6 as a concept that has never done justice to the competitive, fractious, and hurly-burly world of Indonesian party politics (Mietzner Reference Mietzner2013, Reference Mietzner2015, Reference Mietzner2016); or as a framework with enduring value for making sense of Indonesia's fledgling democracy and for bringing Indonesia into wider theoretical conversations (Slater Reference Slater2004, Reference Slater2014a; Ambardi Reference Ambardi2008; Muhtadi Reference Burhanuddin2015, Reference Burhanuddin2016).

This article brings detailed evidence from Indonesia's seven presidential cabinets since democratization in 1999 to bear on these debates.Footnote 7 It aims, first and foremost, to establish that a form of party cartelization has indeed long afflicted coalitional politics in democratic Indonesia. What has transpired in Indonesia looks very different from canonical cases of party cartelization in Europe (Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair1995), as Mietzner (Reference Mietzner2013) has convincingly demonstrated. But it still qualifies as party cartelization because it has produced the same troubling outcome for democratic accountability that motivated cartelization theory in the first place: the stunting and scuttling of clearly identifiable party opposition. The introduction of direct presidential elections in 2004 has gradually and haltingly led to a sharpening of the government–opposition divide. This suggests that, in a causal sense, rules clearly matter for the emergence of democratic opposition. But evidence from cabinet formation, including negotiations over cabinet portfolios, suggests that this critical shift for democratic accountability is neither complete nor irreversible. Accountability relations between voters and parties remain surprisingly tenuous in Indonesia, nearly 20 years after democracy started taking root.

In the next two sections, I outline how promiscuous power-sharing can forestall opposition formation in a new democracy through party cartelization. Neither single-party dominance nor insurmountable barriers to new party entry are necessary for opposition to fail in a democratic setting. I then introduce two distinctive power-sharing games: Victory and Reciprocity. Which power-sharing game emerges depends on what power-sharing strategy presidents use. When presidents strategically refuse to share power with parties that opposed them in the election, they make power-sharing a Victory game. When they strategically express openness to sharing power with parties that opposed them, they make power-sharing a Reciprocity game. While Victory-style power-sharing makes opposition inevitable in presidential systems, Reciprocity-style power-sharing makes opposition vulnerable to neutralization and even outright disappearance at any time. When Reciprocity is the dominant power-sharing game, the fate of opposition hangs entirely in the balance of elite bargaining rather than voter preferences.

Section III opens the empirical discussion by locating the origins of promiscuous power-sharing in the parliamentary procedures that anointed Abdurrahman Wahid and Megawati Sukarnoputri as president in 1999 and 2001 respectively. The article's fourth section traces the evolution of Indonesian party coalitions since the formal parameters of Indonesia's power-sharing game were shifted by the pivotal 2004 rule change: the introduction of direct presidential elections. It demonstrates that promiscuous power-sharing has remained remarkably rampant. Opposition has only emerged through contingent bargaining failure rather than any definitive shift toward a Victory game and away from the Reciprocity game that underpins party cartelization as a strategic (albeit shifting) equilibrium. In conclusion, I propose that we reconsider the reasons presidents might be inclined to share power promiscuously in the first place. Perhaps it is really the parties—and not presidents—who see their share of power diminished when coalitions expand.

PARTY CARTELIZATION AND THE OPPOSITION OPTION

Democracy and opposition are supposed to go hand in hand. If authoritarianism is to end, government repression and manipulation of opposition parties must end along with it, allowing them to flourish. Furthermore, democratic accountability between electors and elected requires that voters possess a clearly identifiable opposition option. Absent opposition parties that can threaten to replace incumbents, voters have nowhere to go when governments perform badly; and governments surely know it, thus reinforcing their bad behavior (Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2007; Gottlieb Reference Gottlieb2014). The emergence of viable and identifiable opposition parties is so essential for making democracy work that we seem to assume that it happens as a natural byproduct of democratic transition, and not as a contingent political process following it.

Indonesia's experience with democracy gives us new reason to question this old assumption. Although democratic transition immediately presented Indonesian voters with a plethora of electoral options, it has much less clearly offered them any opposition options. This is not because 1) opposition has been repressed, 2) ruling parties are so dominant that opposition parties find it impossible to generate support, 3) restrictions on new party entry have prevented the emergence of viable opposition parties, or 4) oppositional actors have failed to overcome the collective-action problems that always plague party formation. Democracy did not automatically generate a viable and identifiable party opposition because no parties immediately went into opposition. Even more surprisingly, Indonesia's four democratically elected presidents have all shown an inclination to share power with all significant parties after securing victory. Power-seeking by parliamentary parties takes place under a broader system of presidential power-sharing. Indonesia has not experienced party failure, but opposition failure.Footnote 8

This was theoretically unanticipated. Opposition failure is common under electoral authoritarianism, but not in an electoral democracy like Indonesia. When opposition fails in electoral authoritarian settings, it is typically because vast ideological incompatibilities and disadvantages in accessing patronage resources make opposition coordination too difficult (Greene Reference Greene2006; Arriola Reference Arriola2013). The Indonesian story is intriguingly quite the opposite. There, opposition falters not because parties coordinate too little, but too much—jointly huddling in government ministries to avoid going into opposition. Patronage links Indonesia's presidents with their erstwhile competitors through promiscuous power-sharing deals, rather than clearly and sharply dividing the political system into government parties that enjoy direct access to state resources and opposition parties that do not.

To the extent that a viable opposition fails to emerge in a democratic context, comparative scholars of party politics have chalked it up either to the utter dominance of a single ruling party (Scheiner Reference Scheiner2005), or to restrictive rules on new party entry that prevent oppositional forces in society from assuming viable party form (Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair1995). But in Indonesia, the problem has not been that identifiable opposition groups have failed to become viable parties; it is that viable parties have failed to become an identifiable opposition. Opposition party failure in Indonesia is a failure of opposition, not of parties.

As Table 1 indicates, Indonesia's chronic struggle to develop a clear opposition option has neither been because any single party is dominant or because new parties have been strangled before they could gain strength. The parties above the dividing line were the main players upon democratization in 1999. The only times that a party has even surpassed 20 percent of the vote—PDIP in 1999, Golkar in 2004, and PD in 2009—they saw their support plummet in subsequent national elections. Ruling party dominance is thus not the source of opposition weakness.

Table 1 Neither Party Dominance nor Party Failure (parliamentary vote shares, all + 5% parties)

Nor is any outright failure or marginalization of new parties, as indicated by the multiple parties below the dividing line in Table 1. Especially since the introduction of direct presidential elections in 2004, a series of new parties has emerged and become leading players in Indonesian national politics: mostly as presidential vehicles for retired generals (Mietzner Reference Mietzner2013). To be sure, requirements that parties meet relatively demanding electoral thresholds and build branches across the breadth of the Indonesian archipelago to gain national parliamentary representation bolster party cartelization to some degree (and by design).Footnote 9 But this is not the source of opposition failure. Indonesia has plenty of viable parties that could serve as opposition. Rules like electoral thresholds hinder new viable parties from emerging, but clearly without much success in the Indonesian case. And they do nothing to hinder existing viable parties from going into opposition.

Democracy without identifiable opposition is both paradoxical and problematic. If democracy is to deliver public goods and improved responsiveness to ordinary citizens, it is largely due to party competition and the threat of replacement. Competitive elections are only the beginning; if a president can induce all parties to share power and go into government rather than opposition, then elections will have removed literally no parties from office. This is especially troublesome from an accountability perspective when presidents offer generous power-sharing deals to parties whose popularity is plummeting at the ballot box.

As we shall see in the empirical discussion below, Indonesia's voters have repeatedly hammered unpopular parties in parliamentary elections, but overwhelmingly failed to remove these unpopular parties from office. Even when those parties’ vote shares decline precipitously, Indonesian presidents have actively sought to share executive power with them, especially through cabinet portfolios. Promiscuous power-sharing thus hinders vertical accountability both retrospectively by failing to sideline parties that voters have just rejected, and prospectively by failing to offer voters a clear opposition option in the elections to come.

But does this mean that Indonesia's party system qualifies as cartelized? To be sure, Indonesia's parties are far from monolithic, disciplined, single-minded in their pursuit of patronage, or devoid of either ideological leanings or social linkages. As Mietzner (Reference Mietzner2013) has convincingly detailed, Indonesian parties are internally undisciplined, mutually uncooperative, at least intermittently driven by purposes besides seeking patronage, and more strongly socially rooted than parties in many other countries. For Mietzner, this means that Katz and Mair's (Reference Katz and Mair1995) “cartel party” model is wholly inapplicable to Indonesia. By contrast, this article insists that the concept of cartelization still sheds valuable light, so long as we do not apply it so strictly as “to impose a European straitjacket on the analysis of Indonesian politics” (Slater Reference Slater2004, 66).

Adopting the cartelization concept in Indonesia naturally means adapting it. For Katz and Mair, cartel parties have been a syndrome of highly mature European democracies in which generous public financing helps parties centralize power in their top leaderships and divorce themselves from their historic social constituencies, most notably labor. Indonesia does not match these specifics or their causal interactions. One would thus do well to distinguish Katz and Mair's cartelization theory from their cartelization concept. To apply and adapt an existing concept to a new context is not to embrace, whole cloth, the existing causal theory underpinning it.

Even if the causal interconnections Katz and Mair hypothesize among intraparty relations, interparty relations, party–state relations, and party–society relations do not hold up in Indonesia, that does not mean that cartelization cannot exist. It merely means that party cartelization, Indonesian-style is a very different beast from party cartelization, European-style. Where it accords most closely with European-style cartelization—and what makes the conceptual traveling worthwhile—is in the failure of identifiable party opposition to emerge as a direct result of power-sharing practices.Footnote 10 In fact, the occasional existence and chronic specter of 100 percent government coalitions makes party cartelization in some sense even more extreme in Indonesia than in Europe, where even the grandest of grand coalitions never encompasses all viable parties.

But how do we know a cartelized party system when we see one? It cannot be one in which political elites have neither personal rivalries nor ideological differences, nor one in which all parties are perfectly disciplined both in their internal relations and external interactions, since no such party system has ever existed anywhere. It is one where such rivalries and differences, intense as they may be, do not compel elites to join identifiably and consistently distinctive and competing political coalitions. It is one where every significant party expresses openness to sharing power with every other, even when those parties have profound ideological differences. It is one where parties with plummeting electoral support suffer little to no consequences from their setbacks, because stronger parties remain willing to share power with them, their growing unpopularity—and by logical extension, the voters themselves—be damned. Neither decisive electoral defeats nor cavernous ideological distance preclude a party from being invited to join a coalition under conditions of promiscuous power-sharing.

Once those coalitional partnerships are formed, parties may undermine, betray, and backstab each other. But so long as they stay in the same ruling coalition, they cannot, by definition, serve as opposition, because they cannot offer voters an electoral alternative to the incumbent government. The undisciplined and inconsistent cooperation that Mietzner deftly chronicles in Indonesian governing coalitions is not a substitute for disciplined and consistent opposition: it is its antithesis. Even at its most ruthless, this “very peculiar, quasi-anarchical form of accountability” (Mietzner Reference Mietzner2013, 157) can only produce horizontal accountability between political elites, and the essence of a cartel is that it stifles vertical accountability between politicians and voters (O'Donnell Reference O'Donnell1994).Footnote 11 A cartelized party system is one that repeatedly fails to usher losing parties into opposition. This makes it surprisingly difficult for democratic voters to hold incumbent parties accountable through their electoral removal.

This is not to say that Indonesian voters cannot hold individual incumbents accountable for bad performance. Since direct executive elections were introduced in 2004, Indonesia's voters have thrown out countless incumbent executives with apparent relish if not abandon. To reject and remove individual candidates is a meaningful form of vertical accountability. But it is a lesser one than removing unpopular parties entirely. This is most vividly seen when individuals who have been thoroughly and repeatedly trounced in presidential polls—such as Megawati Sukarnoputri, Jusuf Kalla, and Wiranto—have managed to remain among the most powerful figures in presidential coalitions despite their overwhelming and repeated repudiation by voters.

Nevertheless, the fact that direct executive elections give voters the power to “throw out the bums” (Pop-Eleches 2011) is one of the major reasons I argue that party cartelization has abated since 2004, as I explicitly embraced as a likely possibility on the eve of the first direct executive elections (Slater Reference Slater2004). The cabinet data in the next section will make this abatement of cartelization under pure presidentialism relatively clear. My primary descriptive purpose is to gauge cartelization as a contingent, piecemeal, and reversible process, and not just to determine its presence or absence as a fixed and final equilibrium outcome.Footnote 12 Cartelization evolves even as it persists.

This attentiveness to process will be crucial in the empirical sections below. Even when presidential power-sharing yields less than a 100 percent coalition, this does not necessarily prove that a president has strategically attempted to build a limited coalition, or that some parties actually prefer to be in opposition. It could simply mean that negotiations over the terms of admission into a presidential coalition have failed. At the end of the day, Indonesian parties do not seem as interested in defeating each other as in outcompeting each other. The distinction is subtle but vital. Democratic accountability demands that winning parties carry out the will of the voters and sideline defeated parties from office. It is not enough to outcompete and then embrace one's rivals. Democratic elections in Indonesia have not been competitions to destroy the party cartel, but to lead it.

RECIPROCITY VS. VICTORY: ALTERNATIVE GAMES OF PRESIDENTIAL POWER-SHARING

Power-sharing is a strategic political game. It is shaped, accordingly, by political institutions. Of particular importance are the rules governing selection of the chief executive (in Indonesia's case, always a president). If a president is elected by parliament, he (or she) is an agent of parliament. He can be expected to share power, roughly proportionally, with the parties resident there that selected him. If the people elect the president, he is an agent of the people, and should face less imperative to share power with parties in parliament that not only played no role in putting him there, but in many cases directly opposed his candidacy.

Yet in both instances, the same implicit assumption underpins our expectations. We assume that a president will share power with whichever parties helped put him in power, and not with those who played no role or even tried to prevent his election. This is what I call Victory: a power-sharing game predicated upon the unwritten rule that presidents will share power only with parties that supported him during his election campaign. To the extent that Victory is the power-sharing game, identifiable party opposition arises automatically. Someone must lose, so someone must go into opposition.

But what if Victory is not the game presidents play? Either in the presence or absence of direct presidential elections, a president might offer to share power with any and all parties that promise to support the presidency, even if they earlier opposed the presidential candidate. Instead of Victory, I call this power-sharing game Reciprocity. If a president prefers or is pressured to play Reciprocity, the emergence of identifiable party opposition becomes contingent rather than automatic. So long as post-electoral Reciprocity bargains can be struck with all parties, all parties can join the executive. Identifiable party opposition may thus vanish, even in a perfectly functional and democratic electoral system. Someone must lose the election, but no one has to lose power.

This allows us to recast Indonesia's struggle to generate an identifiable opposition in straightforward theoretical language. Party cartelization, Indonesian-style rests upon the power-sharing game of Reciprocity. Direct presidential elections will only disrupt or dismantle the cartelized party system if presidents build coalitions comprised of parties that supported them as well as nonparty allies of their own choosing, through the game of Victory.

Yet there are two critical wrinkles to consider. The first is that presidents make strategic choices not only about whom to share power with, but about how much power each partner will receive. Power-sharing games involve distributional conflict among coalition partners, not just between government insiders and outsiders. This means that presidents can strategically provide bonuses to existing supporters through a super-proportional share of cabinet seats, while relegating previous opponents to a sub-proportional share: what President SBY's spokesman, Andi Mallarangeng, called “just a little discount.”Footnote 13 Hence in the cabinet data to follow, we will be attentive not only to whether presidents are sharing power with parties that opposed them during the election (i.e. playing a Reciprocity game), but also to deviations from “Gamson's Law”: the principle that cabinet seats should be distributed proportionally to coalition partners (Gamson Reference Gamson1961; Carroll and Cox Reference Carroll and Cox2007). This should indicate whether presidents have always strategically offered bonuses to electoral backers and imposed discounts on electoral opponents, and whether they are doing so more often since direct presidential elections were introduced. The more willing Indonesian presidents are to sideline erstwhile opponents, the more they shift from a Reciprocity game toward a Victory game, and the better the prospects become for identifiable opposition to emerge and strengthen in Indonesia.

The second caveat is perhaps even more important. It is that presidential coalitions are not necessarily faithful reflections of a president's strategic preferences. Although presidents can choose to play a Victory game by fiat, Reciprocity is a resolutely two-sided game. In other words, Victory games only require a directly elected president to exclude electoral opponents from power as a unilateral strategy,Footnote 14 while Reciprocity demands that they engage those former opponents in a more complicated, multilateral bargaining process. Whether a president seeking to play Reciprocity can actually find willing coalition partners at a price the president is ready to pay depends not on executive decree, but on hard political bargaining. Hence even when we see a coalitional outcome that seems to reflect a Victory game, we must examine whether the absence of Reciprocity arose from a president's strategic decision to play Victory, or from his contingent failure to “seal the deal” with active negotiating partners in an ongoing Reciprocity game.

The implications of this seemingly minor distinction are quite major. If direct presidential elections have emboldened presidents since 2004 to start pursuing Victory rather than playing Reciprocity, then the strategic underpinning of party cartelization is seriously weakening. This would mean that recent moves toward more identifiable opposition, as detailed below, are unlikely to be reversed. But if directly elected presidents are still playing Reciprocity, but simply failing to strike bargains, then the game of power-sharing remains unchanged, even as the final outcome has shifted. This implies that a return to the full party cartelization of the 1999–2004 period remains a meaningful specter, even more than a decade after direct presidential elections were introduced and the party cartel was first disrupted.

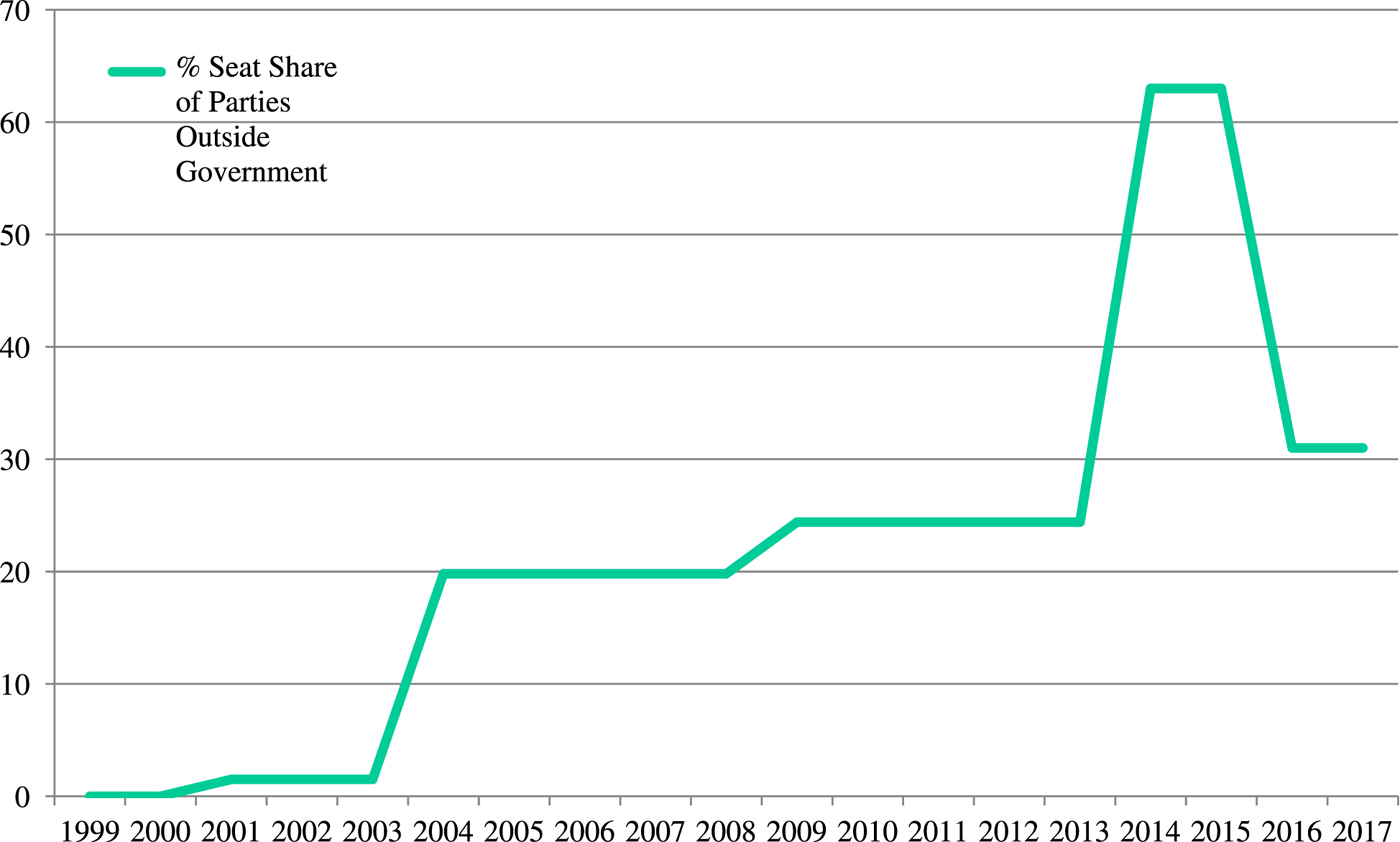

As the following data and narrative show, presidential power-sharing in Indonesia has gradually drifted, but not definitively shifted, from a Reciprocity game toward a Victory game. In raw quantitative terms, the data in Figure 1 unmistakably show that parties have increasingly positioned themselves outside of government since 2004. Yet the numbers obscure much of what the qualitative assessment to follow should reveal. The lingering importance of Reciprocity can still be seen in vigorous efforts by both President SBY (2004–14) and President Joko Widodo (or Jokowi, 2014–present) to forge alliances across the full range of Indonesian parties. Promiscuous bargaining has continued almost unabated since 2004, but it has not always been consummated in power-sharing bargains. In sum, promiscuous power-sharing primarily arose from 1999–2004 because parliamentary parties had the power to demand it; it has persisted since 2004, even while evolving and abating, because strengthened presidents have had a strategic interest in maintaining it.

Figure 1 The Evolution and Abatement of Party Cartelization

Continued attempts at promiscuous power-sharing strongly suggest that Reciprocity remains the dominant game. Party cartelization has abated in Indonesia, but not vanished. And it could still easily come back in its most extreme form. Even if it does not, the public willingness of all parties to consider power-sharing alliances with all other parties means that Indonesia's voters can never be confident that a vote for one party means a vote against any other. Under conditions of promiscuous power-sharing, objectionable and unpopular parties and individuals can only be removed from office by elites, not by the voters. Vertical accountability is thus structurally and severely attenuated.

THE ORIGINS OF PARTY CARTELIZATION: RECIPROCITY AND VICTORY UNDER INDIRECT ELECTIONS

From 1999–2004, there was not much empirical daylight between Victory and Reciprocity in Indonesia's presidential power-sharing. This is because, before the advent of direct presidential elections, vast party coalitions came together on two occasions to usher a consensus president to power. This made the parties that initially anointed the president and those that subsequently supported the presidency practically one and the same. The first occasion was parliament's indirect election of Abdurrahman Wahid of the PKB as Indonesian president in October 1999. The second was Wahid's impeachment and replacement by Megawati Sukarnoputri in June 2001. The origins of promiscuous power-sharing and party cartelization were severely overdetermined (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2013).

Before party elites could assemble presidential coalitions, Indonesia's voters would have their say in the June 1999 parliamentary election: the first free and fair national vote since 1955. This election was conducted under a closed-list PR system and produced no majority party. It did, however, deliver nearly 87 percent of the votes and just over 90 percent of the total parliamentary seats to five major parties. (See the first numerical column in Table 2.Footnote 15 ) The opposition party PDIP under Megawati Sukarnoputri gained approximately 33 percent of all seats, outperforming the old authoritarian vehicle, Golkar, which gained 26 percent thanks in part to regional malapportionment in its favor. Three Islam-oriented parties (the PPP, PKB, and PAN) secured roughly 10 percent each. Meanwhile, the Indonesian military, or TNI, retained nearly 8 percent of all parliamentary seats to protect its interests during the country's tumultuous, economic-crisis-wracked democratic transition.

Table 2 Power-Sharing in Wahid's “National Unity Cabinet,” 1999–2000

* Vice President (VP) included in % of Party Appointments count

# Coordinating Ministers are included in “Cabinet Ministers” count

Under semi-presidential rules, Indonesia would see its president selected indirectly by the parliament, at a special session in October 1999. Despite her advantage in seats, Megawati failed to build the coalition necessary to secure the presidency. Instead, Amien Rais of the PAN took the lead in forging an Islam-oriented coalition dubbed the “Central Axis,” which threw its support behind PKB leader Abdurrahman Wahid. Despite the fact that the PKB held only 11 percent of all parliamentary seats, Golkar and the military supported Wahid over Megawati and delivered him the presidency. After pro-Megawati riots broke out in outrage at her defeat, Megawati was offered the vice-presidency as a consolation prize. In the coalition formation process that followed, new President Wahid had little choice but to yield to the interests of the parties that had elected him. He duly constructed a “National Unity Cabinet” that distributed portfolios to every significant party and then some, including even the tiny PK—a member of the PAN-led Islamic “Central Axis”—despite holding only 1.5 percent of all parliamentary seats (see Table 2).

This initial bout of promiscuous power-sharing did not mean that ideology was irrelevant to Indonesian party politics. To the contrary, sharp differences over questions of religion and democratic reform had shaped both the 1999 election and the special parliamentary session at which Wahid was surprisingly elevated to the presidency (Slater Reference Slater2014a). Ideology was far from nonexistent, but it was also far from constraining when it came to building coalitions. As Table 2 indicates, Wahid clearly played Reciprocity, as literally all significant parties received cabinet portfolios in exchange for supporting Wahid's new presidency. But one could also glimpse signs of a strategic presidential willingness to distinguish electoral backers from opponents, as Wahid gave a disproportionate number of cabinet seats to his own PKB at the expense of the vanquished PDIP. Indeed, Indonesian presidents since Wahid have consistently departed from pure proportionality in portfolio allocation (or “Gamson's Law”) in ways that privilege previous backers and punish earlier opponents. Indonesian presidents have always been willing to play Victory in deciding who gets how much, even while playing Reciprocity in deciding who gets in.

It did not take long for the promiscuous power-sharing bargain of 1999 to break down. Within months of his inauguration, the power-sharing arrangement between President Wahid and the parliamentary parties that had elected him began to fray. Chafing at his parliamentary cabinet and tempted by his formal presidential powers, Wahid began in 2000 to expel from his cabinet representatives of PDIP and Golkar—Indonesia's two largest parties—and to bulk up his PKB's position in the executive (see Table 3). Even while taking care to preserve at least some portfolios for all members of the party cartel, Wahid set off a firestorm with what seemed to his initial parliamentary backers to be a wanton power grab. By 2001, every party except Wahid's own PKB had come together to impeach and remove Wahid from the presidency. This meant the promotion of Megawati to the presidency and of her PDIP to the coalition-building catbird seat.

Table 3 Power-Sharing in Wahid's “All the President's Men Cabinet,” 2000–01

* Vice President (VP) included in % of Party Appointments count

# Coordinating Ministers are included in “Cabinet Ministers” count

Like Wahid in 1999, Megawati honored her party backers in her 2001 cabinet, spreading portfolios in relatively proportional fashion across the full party cartel as her backers demanded (see Table 4). Even the PKB, the party of ousted President Wahid, retained a seat, by virtue of one PKB politician's expressed willingness to support the new Megawati-led government. The largest party left outside the cabinet—and thus placed below the dividing line in Table 4 –was the PK (soon to be renamed PKS), which held only 1.5 percent of all parliamentary seats, making it far from a credible contestant for national power in the upcoming 2004 elections. The Reciprocity game thus produced an absence of significant and identifiable party opposition.

Table 4 Power-Sharing in Megawati's “Mutual Assistance Cabinet,” 2001–04

* Vice President (VP) included in % of Party Appointments count

# Coordinating Ministers are included in “Cabinet Ministers” count

IV. THE EVOLUTION OF PARTY CARTELIZATION: RECIPROCITY AND VICTORY UNDER DIRECT ELECTIONS

Under Megawati from 2001 to 2004 as under Wahid from 1999 to 2001, Indonesia had zero significant parties in opposition and outside of government. Tables 2–4 should make this abundantly clear. Then a dramatic change in political rules threatened—but by no means promised—to upend this cozy elite arrangement. Demands from civil society groups for the introduction of direct elections for political executives from the national to the local level proved surprisingly fruitful with the electoral reforms of 2002 (King Reference King2004).

This formal shift would not necessarily sound the death knell for party cartelization, however. The two largest parties in parliament, PDIP and Golkar, had developed an extremely close working relationship during the Megawati years, anchored in the emerging political alliance between the president herself and Golkar chairman Akbar Tandjung. The most likely outcome of direct presidential elections in 2004 appeared to be a PDIP candidate (obviously Megawati) facing off against a Golkar candidate (not obviously the uncharismatic Akbar). Whoever prevailed in such a contest would be almost certain to preserve the party cartel by crafting another “rainbow cabinet,” perpetuating a situation in which no significant party opposition existed to check incumbent abuse and ensure voters an opposition option.

What disrupted the party cartel was not the introduction of direct presidential elections per se. Rather, it was disrupted by the vicissitudes of a highly contingent personality conflict that this rule shift had allowed to bubble to the surface. Long denied any hope for the presidency by his lack of party roots, the Coordinating Minister for Politics and Security, popular retired general Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY), rightly saw direct elections as his ticket to the top. When Megawati's husband publicly referred to him as “childish” in March 2004, SBY seized the opportunity to bolt Megawati's cabinet and commence his personal quest for the presidency. He made great political hay out of his “victimization” by his former boss, and adopted the barely breathing PD as the vehicle for his presidential ambitions. After the PD made a respectable showing in the April 2004 parliamentary elections, placing fifth in votes and third in seats, SBY teamed up with one of the other coordinating ministers in the Megawati cabinet—Golkar's Jusuf Kalla—as a presidential and vice-presidential ticket for the subsequent presidential vote. The former general easily surpassed his erstwhile coalition partners,Footnote 16 even though Golkar formally backed the PDIP's Megawati in an effort to salvage the party cartel in the face of the SBY challenge. While Megawati's reelection would have almost surely meant pure coalitional continuity, SBY's big win left elite politics in a state of uncertainty. Such disruption of the party cartel would have been highly unlikely to emerge had Indonesia not shifted to direct presidential elections.

Nevertheless, the politics to follow was characterized by political continuity more than political change. In forming his cabinet, SBY bent over backwards to bring every party on board after he was elected by the people, just as Wahid and Megawati had done after being chosen by the parliament (see Table 5).Footnote 17 Even after taking a super-proportional chunk of portfolios for his own party, and distributing similarly healthy chunks to smaller parties that had backed him against Megawati. such as the PAN, PKS, and PBB, new President SBY still played Reciprocity by dangling cabinet portfolios before all three of the parties that had opposed him: Golkar, the PDIP, and PPP (note the + sign in Table 5 denoting their opposition to SBY in the presidential campaign). The PPP took its bite first, claiming three portfolios in exchange for abandoning its short-lived oppositional stance. Then Golkar toppled its Chairman, Megawati ally Akbar Tandjung, who was insisting that Golkar would stick it out with Megawati's PDIP in opposition, and replaced him with SBY's new Vice President, Jusuf Kalla. The old authoritarian ruling party was duly rewarded with four cabinet seats.

Table 5 Power-Sharing in SBY's First “United Indonesia Cabinet,” 2004–09

+ Parties that directly opposed SBY in the 2004 presidential election

* Vice President (VP) included in % of Party Appointments count

# Coordinating Ministers are included in “Cabinet Ministers” count

That left Megawati, her PDIP, and its 20 percent of all parliamentary seats. Although SBY made repeated Reciprocity overtures to Megawati as well, the former president remained furious with her ex-deputy for bolting her cabinet and challenging her—and then trouncing her—in the inaugural direct presidential elections of 2004. Effectively cutting off her nose to spite her face, Megawati refused to bring her PDIP into the cabinet. A revolt thus erupted in PDIP as in Golkar, as figures with experience in Indonesia's cartelized cabinets attempted to topple Megawati, as Golkar had done to Akbar, and take control of the party to bring it back into the cabinet by accepting SBY's Reciprocity olive branch. Unlike Akbar, Megawati had ample popularity and inherited familial charisma to survive the internal party revolt, and PDIP remained outside the SBY government. For the first time since Indonesia's democratization, a political party of note had assumed the role of political opposition (and thus is positioned below Table 5’s dividing line). This was not because Reciprocity had ceased to be the presidential power-sharing game; it was because Megawati refused to join SBY's Reciprocity game despite the new president's tireless bargaining efforts (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2013). Opposition emerged not because the winning candidate played Victory, but because the vanquished candidate refused to play Reciprocity.Footnote 18

The 2009 presidential elections largely proved to be a replay of 2004, with SBY surpassing 60 percent of the popular vote in a tri-cornered contest against Megawati and his own incumbent vice-president, Golkar's Jusuf Kalla. Once again Megawati ignored internal party pressure and presidential Reciprocity entreaties to bring the PDIP into SBY's cabinet; once again Golkar's leader was toppled for his folly of opposing the presidential steamroller; and once again a new Golkar leader accepted SBY's Reciprocity offer and brought the party into the ruling coalition. The bigger shift was in the parliamentary elections, when the president's PD party more than doubled its seat share to surpass all five of the major parties that originally crafted the party cartel (see Table 6).

Table 6 Power-sharing in SBY's Second “United Indonesia Cabinet,” 2009–14

+ Parties that directly opposed SBY in the 2009 presidential election

# Coordinating Ministers are included in “Cabinet Ministers” count

With this bigger victory in hand, SBY's second cabinet unsurprisingly appeared somewhat more Victory-oriented than his first. The vice-presidency was offered to an economic technocrat instead of a party stalwart, and several small parties besides PDIP stood outside the ruling coalition. As seen in Table 6, the correlation between the “+” parties and those below the dividing line was becoming stronger, as a Victory game would produce. Party cartelization was clearly abating. Yet Indonesian democracy also clearly remained characterized by promiscuous power-sharing. Even an emphatically reelected president continued to offer cabinet seats to literally every party with more than a 5 percent share in parliament.

The 2014 elections would provide a third opportunity for direct presidential elections to deliver a shift from Reciprocity to Victory. Term-limited, SBY would need to step aside, and take his dogged commitment to playing the Reciprocity game along with him. And there was no prospect that SBY might manage to hand over power to one of his long-standing partners in his coalition. The only two political figures with a meaningful chance at winning direct presidential elections, based on opinion polls conducted throughout the year preceding the 2014 vote, were two non-participants in SBY's power-sharing arrangements: Jakarta Governor Joko Widodo (Jokowi), whose immense popularity eventually garnered him the presidential nomination of the PDIP despite the obvious trepidation of party leader Megawati; and Prabowo Subianto, the former general and Suharto son-in-law who had sufficiently overcome his stained authoritarian past to build his own Gerindra party into a vehicle for his presidential ambitions.

Jokowi's PDIP and Prabowo's Gerindra were the two big gainers in the April 2014 parliamentary polls (refer back to Table 1, final column). Considering that both had been positioned outside of government under SBY, this suggested that voters might have begun rewarding parties for assuming a more independent stance. According to a nationally representative Populi Center poll in March 2014, 34.0 percent of 1,492 respondents considered PDIP the most frequent critic of SBY's government, which had been racked with corruption scandals surrounding the PD party's leadership contest. Gerindra was portrayed as the most frequent critic by 4.9 percent of respondents: a lower total than Golkar (5.6 percent) and barely higher than PKS (4.5 percent), which had insisted on their right to serve as SBY's “critical partners” despite accepting his offer of cabinet seats. The government-opposition divide was thus becoming clearer, yet remained in important ways blurry.

The Jokowi–Prabowo faceoff in July 2014 proved to be Indonesia's most fiercely contested presidential election to date, with two clearly identifiable electoral coalitions clashing swords: the Great Indonesia Coalition (KIH) backing Jokowi, and the Red-and-White Coalition (KMP) stumping for Prabowo. To a greater extent than in past elections, both coalitions approximated a degree of cleavage consistency (Slater Reference Slater2014b). While Jokowi's KIH was identifiably a pluralist coalition, Prabowo's KMP arrayed all parties supporting a stronger role for Islam in Indonesia's political life. The election also offered a vivid choice in terms of deepening (or at least not dramatically reversing) democratic reform, as Prabowo's authoritarian track record and demagogic style contrasted sharply with Jokowi's outsider background and low-key, hands-on approach to popular politicking. Although Jokowi chose a consummate cartel insider as his running mate, former Golkar leader and vice-president Jusuf Kalla, and allied strongly with the Hanura party run by ex-General Wiranto, the democratic and pluralist credentials of his KIH remained strikingly stronger than those of Prabowo and his KMP.

It was by no means obvious that this coalitional sorting had proceeded as a product of design, however. From the parliamentary election in April until the finalization of the two electoral tickets in late May, both Jokowi and Prabowo expressed openness to coalescing with any parties that would support their candidacies, and engaged in repeated negotiations toward that end. Promiscuous power-sharing negotiations remained rampant. A remarkable top story in the national newspaper Media Indonesia on the day after the parliamentary elections spoke volumes in this respect. Instead of featuring a typical photo of voters accompanied with a headline declaring something to the effect of “The People Have Spoken,” the above-the-fold feature story sported the logos of all top 12 vote-getters in the parliamentary vote, with a headline declaring “Everyone Wants to Coalesce.”Footnote 19

The headline proved prescient. On multiple occasions, major parties such as Golkar, PPP, PAN, and PD appeared to be on the verge of signing on to Jokowi's KIH coalition, until power-sharing talks broke down. Jokowi ultimately proved less willing to offer cabinet seats than Prabowo, who made no bones about his transactional and promiscuous approach to assembling a coalition and a government. Yet even Jokowi explicitly expressed willingness to include all 10 Indonesian parties in his coalition if they backed his agenda, while insisting that he preferred not to dole out ministries in exchange for such support.Footnote 20

This presents us with a picture of partial change amid substantial continuity. Jokowi may ultimately have refused pre-electoral bids by Golkar and other major parties cabinet seats in exchange for their support (Mietzner Reference Mietzner2016), but he by no means refrained from entertaining them. This suggests that direct presidential elections are not producing a wholesale shift away from a Reciprocity game, but inspiring at least some (and by no means all) presidential candidates to drive harder bargains in the multilateral bargaining process. Hence in 2014 as in 2004 and 2009, parliamentary elections gave voters an opportunity to propose, but elites quickly assumed full power to dispose when it came to constructing presidential coalitions. In one particularly telling act of elitist hubris, the PD's spokesman boasted that his party would be the “real kingmaker”Footnote 21 in July's presidential election, despite the fact that the PD had been sharply rebuked and seen its vote share halved in April's parliamentary vote.

The July 2014 presidential vote saw Jokowi besting Prabowo in a nail-biter, 53 percent–47 percent. The testy atmosphere of campaign season spilled over uncharacteristically into governing season, as the KMP pushed a bill through the legislature that sought to ban direct local elections and thus seal off the path to power that Jokowi had just traveled. Prabowo's newborn opposition coalition also refused to let Jokowi's KIH parties assume leadership positions on parliamentary committees, in a sharp departure from the proportional power-sharing that had prevailed under the presidencies of Megawati and SBY. This emergent government–opposition divide found clear expression in Jokowi's first “Working Cabinet” (see Table 7), which looked more like a Victory cabinet than any yet seen since Indonesian democratization. Gerindra, PAN, and PKS had all opposed Jokowi, and Jokowi had left them all out of his cabinet.Footnote 22 Golkar had gained the vice-presidency and PPP was granted the prized Ministry of Religious Affairs, yet those parties’ leaderships stuck to their guns in supporting the Prabowo-led opposition coalition.

Table 7 Power-Sharing in Jokowi's First “Working Cabinet,” 2014–16

+ Parties that directly opposed Jokowi in the 2014 presidential election

* Vice President (VP) included in % of Party Appointments count

# Coordinating Ministers are included in “Cabinet Ministers” count

If this pattern of power-sharing had persisted, Indonesia would have finally had a clearly identifiable political opposition coalition in the form of the KMP—albeit one with worrisomely questionable democratic credentials—that promised to hold the president's feet to the fire with the credible threat of replacement in the 2019 elections to come. As Burhanuddin Muhtadi argued when surveying Jokowi's first cabinet, “there was evidence that the cartel system that has defined Indonesian politics since the onset of reformasi was finally dead” (2015, 351).

As it happened, the KIH–KMP divide neither lasted in its original form nor vanished entirely. Much like in 2004, when SBY gradually managed to bring Golkar and PPP onto his side after those leading parties backed Megawati against him in the presidential campaign (recall Table 5), Jokowi managed in the aftermath of the 2014 election to pull PPP, PAN, and Golkar out of Prabowo's KMP coalition and into his own KIH (see Table 8).Footnote 23 As Mietzner (Reference Mietzner2016) has argued, Jokowi used more strong-armed tactics than SBY had deployed in sweeping parties from opposition into government, especially by denying government recognition to the factions of divided parties that preferred to stick with Prabowo and his KMP coalition. Yet this only underscores the critical point that, since 2004, party cartelization is being upheld by strengthened presidents who prefer playing Reciprocity to countenancing party opposition.Footnote 24 It is not simply a product of patronage-hungry parties successfully jockeying for state access.

Table 8 Power-Sharing in Jokowi's Second “Working Cabinet,” 2016–

+ Parties that directly opposed Jokowi in the 2014 presidential election

* Vice President (VP) included in % of Party Appointments count

# Coordinating Ministers are included in “Cabinet Ministers” count

With his long-awaited cabinet reshuffle in July 2016, Jokowi shifted from playing pure Victory to playing a more familiar mix of Reciprocity as a way of deciding who gets in, and Victory to determine the formula for who gets what. As Leo Suryadinata and Siwage Dharma Negara (Reference Suryadinata and Dharma Negara2016) pithily depicted the return of a Reciprocity game in Jokowi's approach: “The custom in Indonesian politics is that parties who support the government expect to be rewarded with cabinet positions. Hence the recent reshuffle.” Barely a year after prematurely projecting that cartelization might finally be a thing of the past, Muhtadi (Reference Burhanuddin2016) concluded that Jokowi's reshuffle signaled “the renewed strength of the ruling cartel that has dominated politics since the end of the New Order.” Reciprocity thus made a comeback in Jokowi's 2016 cabinet reshuffle that is hard to fathom without cartelization theory.

The fuller picture is one of abatement in cartelization as much as continuity, however. The fact that Jokowi's original electoral partners (PKB, Hanura, and NasDem) remained overrepresented in his second “Working Cabinet” testified to the rising presidential willingness to play a Victory game in deciding seat proportions, as one would expect in a system of direct presidential elections. The underrepresentation of Golkar, PPP, and PAN exemplified Jokowi's willingness to play Victory when confronting his erstwhile opponents as well. It was also telling that two of Golkar's three representatives in the Jokowi administration (Jusuf Kalla as vice-president and Luhut Panjaitan as coordinating minister for political and security affairs) were embraced much more as personal allies of the president himself than as loyalists of Golkar per se. The upshot was that the three erstwhile opponents all gained singular cabinet seats (suffering a “discount” in proportional terms), while the electoral supporters all secured super-proportional shares (securing a “bonus” for their earlier electoral services rendered).

Yet even these meager concessions sufficed for Jokowi to ensnare Golkar, PPP, and PAN in the executive, and prevent them from serving as a clearly identifiable opposition in the years to come. By the same token, the continued positioning of Gerindra and PKS in opposition should give Indonesian voters every reason to suspect that those two parties will serve as the main challengers to Jokowi's reelection bid in 2019.Footnote 25 The abatement of cartelization in Indonesia is thus considerable indeed, as opposition has become more clearly identifiable since 2004 and especially since 2014—even if the precise shape of the government–opposition divide remains a contingent byproduct of elite negotiations and not a reliable response to voter preferences.

Still, the detailed longitudinal cabinet data offered here suggest that this recent abatement in cartelization is very much partial, tenuous, and reversible. It is partial because most major parties have once again been drawn from opposition into government, and hence are not in position to hold elected leaders accountable. The leading “opposition” party after the 2014 campaign, Golkar, was already promising to endorse Jokowi for reelection in 2019 by the time it joined his government in 2016. It thus remains the case that Indonesia has failed to produce a robust opposition coalition from democratization in 1999 until the present day. The abatement in cartelization is also tenuous because it is entirely dependent upon the power-sharing game—Victory or Reciprocity—that presidents and their negotiating partners choose to play. Voters have no reason to believe that parties who underperform in parliamentary elections will be punished or marginalized accordingly when it comes to forming presidential coalitions. The upshot is that cartelization's recent abatement is utterly reversible; and Jokowi has already substantially reversed it. So long as presidents seem ill-disposed toward accepting opposition in any solid form, and parties seem primarily disposed toward joining government rather than holding it accountable as an opposition option, Indonesian voters have only one form of protection against the reestablishment of a full-blown party cartel: Indonesian politicians’ incapacity to negotiate its terms.

CONCLUSION

If the democratization of the fourth-largest country on Earth did not deliver some surprises for democratization theory in comparative politics, it could only be from not paying close enough attention. Among the many surprises that have attended Indonesia's nearly two decades of democracy—including the surprise that democracy has consolidated at all—one of the greatest is that opposition has largely failed to emerge. This is despite the absence of the two factors most often seen as hindering opposition in democratic settings: 1) the existence of a dominant single party, and 2) the failure of new parties to overcome barriers to entry. Indonesia has no dominant party, and no shortage of parties that could readily serve as an identifiable political opposition if they were so inclined. Leading parties have tried to limit the entry of new parties in various ways, but with precious little success. While most democracies have a clear opposition but a small number of opposition parties to choose from, Indonesia has a great many party options, but none of them have proven willing to act in a consistently oppositional manner.

Looking forward, future research should attend to the most fundamental puzzle that this article could not adequately address or systematically answer: why might directly elected presidents find benefit in building coalitions that are much wider than necessary for passing legislation, avoiding impeachment, and achieving communal peace? Recent theoretical literature on presidential coalitions puts great stress on the need to pass legislation under what Scott Mainwaring (1993) famously dubbed the “difficult combination” of multiparty presidentialism.Footnote 26 This is surely part of the story, but almost certainly not all. Coalitions that entirely remove parties from opposition are a qualitatively different phenomenon than ones that simply reduce the number to a surprisingly small size. Whether we need different theories for this, or whether coalitions may simply grow to 100 percent through an additive logic of multiple power-sharing logics that have already been theorized, is an open question. The case of Indonesia certainly suggests that scholars should be attending to the informal politics of power-sharing as well as the formal rules that give it relatively predictable shape.

The most intriguing implication of Indonesia's experience with democratic power-sharing may be this: Presidents may sometimes see broad coalitions as a source of instead of a drain on their power and resources. Oversized coalitions are typically seen as being more expensive to maintain. As Chaisty, Cheeseman, and Power (Reference Chaisty, Cheeseman and Power2014, 83) put it, expanding the number of parties in a cabinet “dilutes the executive's ability to monopolize resources and policy influence.” But this may not be how presidents see things at all, at least under certain conditions. Oversized coalitions may be better conceived as ways for presidents to spread the same amount of resources across more claimants, thus ensuring that no single partner can become too strong as a rival. If nothing else, the persistence and evolution of party cartelization, Indonesian-style suggests that power-sharing should not be seen as occasions for presidents simply to give. Political scientists should look more carefully to see what presidents may sometimes take away in exchange.