Introduction

The Aramaic onomasticon found in Babylonian sources linguistically belongs to the West Semitic languages while it is written in cuneiform script used to express Late Babylonian Akkadian, an East Semitic language (see Figure 8.1). Among the languages classified as West Semitic, four are recognisable in the Late Babylonian onomasticon: Arabic names, generally viewed as representing the Central Semitic branch; Phoenician; Hebrew (or Canaanite); and Aramaic names representing its Northwest Semitic subgroup.Footnote 1

Figure 8.1 A family tree model of Semitic languages.

Aramaic names make up the largest part of the West Semitic onomasticon in the Neo- and Late Babylonian documentation. They will be the focus of this chapter. Chapter 9 deals with Hebrew names, Chapter 10 with Phoenician names, and Chapter 11 with Arabic names from this period. The Aramaic onomasticon of the preceding Neo-Assyrian era, which has been researched by Fales, is not included here.Footnote 2 A given name may be recognised as Aramaic on the basis of patterns and trends regarding patronym, the occurrence of an Aramaic deity, and the socio-economic context of the attestation. Despite the fact that these factors provide valuable background information (see section on ‘Aramaic Names in Babylonian Sources’), the most secure way of deciding on the Aramaic nature of a name is based on linguistic criteria:

- phonological: phonemes of Semitic roots are represented in a way specific for Aramaic;

- lexical: words are created from roots that solely appear in Aramaic;

- morphological: forms and patterns used are peculiar for Aramaic;

- structural: names are constructed with, for instance, Aramaic verbal components.Footnote 3

Opinions differ as regards the nature of the Aramaic language in Babylonia during the Neo-Babylonian era. Aramaic attestations from this timeframe are – together with those from the preceding Neo-Assyrian period – variously evaluated as belonging to Old Aramaic as found in sources from Aramaean city states, as manifestations of local and independent dialects, or as (precursors of) Achaemenid Imperial (or Official) Aramaic.Footnote 4

Defining the variety of Aramaic used in Babylonia is hindered by the fact that direct evidence from this area is generally scarce and textual witnesses from its state administration, which presumably was bilingual Akkadian–Aramaic, are non-extant. Aramaic texts mainly appear as brief epigraphs written on cuneiform clay tablets.Footnote 5 Moreover, a small number of alphabetic texts were impressed into bricks by those working on royal buildings in Babylon.Footnote 6

Chronologically, the major part of the Aramaic onomasticon appears in cuneiform texts dating to the latter half of the fifth century – a period in which the use of Aramaic as chancellery language of the Achaemenid Empire seems to have been established in all parts of its vast territory. Achaemenid Imperial Aramaic is attested in a large variety of literary genres across socio-economic domains and is written in alphabetic script on various media, such as papyri, ostraca, funerary stones, and coins.Footnote 7 Overall, the orthography of this language variety is marked by consistency (especially in administrative letters), its syntax displays influences from Persian and Akkadian, and its lexicon contains an abundance of loanwords from various languages.Footnote 8

Aramaic Names in Babylonian Sources

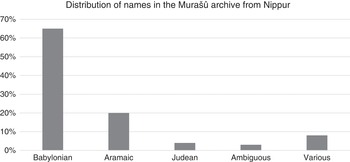

Aramaic names can be found in cuneiform economic documents from all over Babylonia, but they appear most frequently in texts from the villages Yāhūdu, Našar, and Bīt-Abī-râm, dating to the sixth and early fifth centuries,Footnote 9 and in the extensive Murašû archive originating from the southern town of Nippur and its surroundings, which covers the second half of the fifth century.Footnote 10 By contrast, the proportion of West Semitic names in city-based cuneiform archives is relatively marginal: about 2 per cent of the c. 50,000 individuals appearing in this text corpus bear an Aramaic name if the Murašû documentation is disregarded; this amounts to 2.5 per cent if the latter archive is included.Footnote 11 The proportion of Aramaic names in the Murašû archive is ten times higher than the norm (see Figure 8.2).Footnote 12

One of the reasons behind the marked difference in the proportion of non-Babylonian names between the rural archives and the Babylonian sources in general is the fact that the former are characterised by less formative influence – and thus representation – of Babylonian elites, who formed a relatively homogenous social group. They lived in the city; were directly or indirectly connected to its institutions, most notably the temples; and virtually always bore Babylonian personal names, patronyms, and family names (see Chapter 1).Footnote 13 Unsurprisingly, they appear as protagonists in the urban documentation, while individuals with non-Babylonian names tend to have the passive role of witnesses.Footnote 14

Onomastic diversity thus correlates with a decidedly rural setting. This is underlined by the fact that Murašû documents not written up in Nippur, but in settlements located in its vicinity, display larger proportions of both parties and witnesses with non-Babylonian names.Footnote 15 Likewise, texts from the rural settlements of Yāhūdu, Našar, and Bīt-Abī-râm contain a substantive amount of West Semitic names. Indeed, the multilingual situation in Babylonia’s south-central (or possibly south-eastern) region, whence these two cuneiform corpora originate,Footnote 16 already stood out during earlier centuries. Letters in the archive of Nippur’s ‘governor’ written between c. 755 and 732 BCE attest to the connections between powerful leaders of Aramaean tribes and feature many Aramaic-named individuals, as well as Aramaisms.Footnote 17 Moreover, a letter dated to king Assurbanipal’s reign (seventh century BCE) mentions speakers of multiple different languages living in the Nippur area (roughly indicated by the brackets in Figure 8.3).Footnote 18

Figure 8.3 Nippur and its hinterland.

Various forms of migration contributed to the multi-ethnic character of the population in this region. First, non-Babylonian sections – among which were Aramaean groups – migrated into the territory east of the Tigris (the area indicated by the arrows in Figure 8.3).Footnote 19 Second, the diverse populace was a result of forced migration. For instance, the Babylonian king Nabopolassar (626–605 BCE) took many prisoners of war – most of them Aramaeans – from settlements in upper Mesopotamia and the middle Euphrates region and relocated them to the Nippur area in 616 BCE. Not long before, Nippur itself had been an Assyrian town where a garrison was stationed; it was only besieged and conquered between 623 and 621 BCE. Campaigns led by subsequent kings, most notably Nebuchadnezzar II (604–562 BCE), resulted in deportations of communities from Syria and the Levant and their resettlement in the same region around Nippur.Footnote 20 The state provided the deportees with fields and in return levied taxes and/or rents and conscripted the landholders as troops. The process is documented in its early stages in the cuneiform texts from Yāhūdu and its environs. Also, the Murašû archive depicts individuals active in this so-called land-for-service system.Footnote 21 Due to these migratory flows, not only the onomasticon is diverse: many toponyms in this region are non-Akkadian or Akkadian – West Semitic hybrids as well. They may refer to Aramaean tribes, eponymous forefathers, or places of origins in Syria or the Levant.Footnote 22 Finally, Aramaic epigraphs are quite well-attested in these archives.

During the Achaemenid period, the southern region functioned as a passageway between the Persian heartland and the Empire’s western provinces. Through the Kabaru Canal the Babylonian waterways were directly connected with Susa, the Persian capital in Elam. Except for thus being of geopolitical importance, this area hosted travellers from Babylonia and far beyond who began the last stage of their trip to the capital here, upon changing boats in the settlement of Bāb-Nār-Kabari.Footnote 23

Spelling and Normalisation

The normalisation of West Semitic names written in Babylonian Akkadian, for which no academic standard has been formulated, is challenging. First, it is not always straightforward whether a name is Akkadian or Aramaic; for instance, Iba-ni-a can be read as Akkadian Bānia and as West Semitic Banī, a hypocoristic form of the sentence name ‘DN-established’. Second, there are many ways to approach the transcription of Aramaic names, based on the question of whether an attempt should be made to reconstruct the characteristics of an Aramaic name and, if so, to what extent. This could pertain to relatively straightforward issues, such as phonemes not represented in Akkadian (for instance, the gutturals) or those rendered differently (for instance, /w/ written /m/, as visible in the Judean theophoric element Yāma). However, it also relates to features such as vowel quality, vowel length, and stress, which are often not easy – or are downright impossible – to reconstruct due to incongruity of the writing systems and the inconsistency in which Aramaic names are converted into Akkadian.Footnote 24 Therefore, taking the Akkadian spelling as a point of departure and including only the most basic features rendered by it in a relatively consistent manner is my preferred modus operandi for transcription.

At the same time, some degree of harmonisation is necessary as, for instance, the spelling of the perfect in the Aramaic name DN-natan shows: IDN-na-tan-nu/-ni/-na (the final CV-sign merely indicates that the previous syllable is stressed). Abstraction on the basis of the Aramaic verbal form avoids a plethora of names that are in fact orthographic varieties. Moreover, although vowel length is not included in transcription when uncertain, a frequent and clear trend is taken into account: as the final long vowel of the perfect 3.sg. m. of verbs ending in ˀ/y/h is nearly always represented, the transcription of, for example, IDN-ba-na-ˀ is DN-banā. These examples demonstrate that there will always be a margin of error and that a hybrid transcription is inevitable – something that does not seem unfitting in view of the sources.Footnote 25

Typology of Aramaic Names

The Theophoric Element

Besides the general theophoric element, this section deals with specific Aramaean deities. When these occur with Akkadian complements, the names are viewed as hybrids; in order to qualify as an Aramaic name, the linguistic criterion is decisive.

ˀl and ˀlh

The most frequently attested theophoric element is ˀl (ˀil) ‘god’. In cuneiform script, this element is written DINGIR, the logogram and determinative for the Babylonian word ilu ‘god’, which also has the phonetic value an.Footnote 26 It is broadly acknowledged that the (plural) logogram DINGIR.MEŠ is employed for the same purpose in the Late Babylonian period.Footnote 27 In other words, a name like Barik-il ‘God’s blessed one’ can be rendered Iba-ri(k)-ki-DINGIR as well as Iba-ri(k)-ki-DINGIR.MEŠ. Similarly, Raḫim-il ‘God’s loved one’ is spelled both Ira-ḫi-im-DINGIR and Ira-ḫi-im-DINGIR.MEŠ. The same orthographic variation applies to the element ˀl in the name of the deity Bīt-il: for example, Bīt-il-ḫanna ‘Bīt-il is gracious’ (IÉ-DINGIR-ḫa-an-na) and Bīt-il-adar ‘Bīt-il has helped’ (IÉ-DINGIR.MEŠ-a-dar-ri).Footnote 28

The element ˀlh (ˀilah) is less frequently attested. Examples are Abī-ilah and Ilah-abī ‘God is my father’ (IAD-ìl-a and Iìl-a-AD).Footnote 29 It tends to appear as final component, followed by possessive suffix 1.sg. -ī, for example, in the names Mannu-kî-ilaḫī ‘Who is like my god?’ (Iman-nu-ki-i-i-la-ḫi-ˀ) and Abī-ilaḫī ‘My father is my god’ (IAD-la-ḫi-ˀ; IAD-i-la-ḫi-ˀ).Footnote 30

Aramaean Deities

A common theophoric element in Aramaic names is Addu or Adad, the storm god, written dad-du and dIŠKUR respectively:Footnote 31 Addu-rapā ‘Addu has healed’ (Idad-du-ra-pa-ˀ), Adad-natan ‘Adad has given’ (IdIŠKUR-na-tan-nu). Despite being a Mesopotamian god, the epicentre of Adad’s veneration remained northern Syria. Here, he took the primary place among the Aramaean deities. The fact that Adad has a strong familial association with the deities Apladda and Būr is visible in father – son pairings Būr-Adad or Adad-Būr in the corpus from Yāhūdu, Našar, and surrounding settlements.Footnote 32 Adgi, a West Semitic form of Adad, is attested with an Aramaic predicate in the Murašû archive.Footnote 33

Tammeš, whose Akkadian equivalent is Šamaš, is attested with a wide variety of Aramaic complements, especially in Nippur, one of which is Zaraḫ-Tammeš ‘Tammeš has shone’ (Iza-ra-aḫ-dtam-meš). Although various phonetic cuneiform spellings are employed to render the initial West Semitic consonant /s/, dtam-meš is the most current orthography in Neo- and Late Babylonian sources.Footnote 34

The name of the moon god Iltehr (based on ˀil and *sahr) is akin to Akkadian Sîn. This is visible in tablets from the village of Neirab, a settlement of deportees originating from the like-named ‘centre of the moon’ cult in Syria.Footnote 35 In those tablets, we find the name of the same person Iltehr-idrī ‘Iltehr is my help’ spelled both Idše-e-ri-id-ri-ˀ and Id30-er-id-ri-ˀ. However, typically Iltehr is written dil-te-(eḫ-)ri in cuneiform texts.Footnote 36

Another Aramaean deity from the heavenly realm is ˁAttar (ˁttr), with cognates in a range of Semitic languages. In Akkadian this is Ištar, which has the variant form Iltar:Footnote 37 Attar-ramât ‘Attar is exalted’ (Idat-tar-ra-mat), Iltar-gadā ‘Iltar is a fortune’ (Iìl-ta-ri-ga-da-ˀ). The Neo-Assyrian sources show that the consonantal cluster -lt- often shifted to -ss-, which was pronounced -šš-. Although these examples show that this shift did not carry through consistently in Babylonia, it may be visible in the name Iššar-tarībi ‘Iššar replaced’.Footnote 38

Amurru is a popular theophoric element in Aramaic names from the sixth and fifth centuries, although the deity had a low status in the Mesopotamian pantheon. From the late third until the middle of the second millennium it was used as a device by Sumerians and Babylonians to identify Amorites whose distinct linguistic and cultural presence was becoming more prominent. As the Amorites started to assimilate, the need of othering disappeared and groups of West Semitic origins adopted Amurru in name-giving practice as a way to self-identify.Footnote 39 Amurru being the most frequent West Semitic theophoric element in the onomasticon from Našar and neighbouring villages is a manifestation of this trend.Footnote 40 Also attested in these villages is the deity Bīt-il, who was venerated in an area close to Judah and whose name-bearers may have been deported simultaneously.Footnote 41

Other West Semitic deities that appear with Aramaic complements are Našuh or Nusku (for instance, in the Neirab documentation),Footnote 42 Qōs,Footnote 43 Rammān,Footnote 44 and Šēˀ.Footnote 45 Šamê, ‘Heaven’, also appears with various Aramaic complements.Footnote 46 Attestations of the Aramaean deity ˁAttā are scarce and ambiguous. It may be linked to ˁAnat in a similar way as Nabê is connected with Nabû and Sē with Sîn.Footnote 47

Verbal Sentence Names

Most frequent is the sentence name that has a perfect verbal form, also referred to as the suffix conjugation, as its predicate. The subject, which is a theophoric element, often appears as initial component. Generally, the verbal forms are in the G-stem. Some examples are Nabû-zabad ‘Nabû has given’ (IdAG-za-bad-du), Sîn-banā ‘Sîn has established’ (Id30-ba-na-ˀ), Aqab-il ‘God has protected’ (Ia-qab-bi-DINGIR.MEŠ), and Yadā-il ‘God has known’ (Iia-da-ˀ-ìl).Footnote 48

Names in which a deity is addressed by means of a perfect 2.sg. m. (indicated by the suffix -tā) are specific for the Late Babylonian period. They are followed by the object suffix 1.sg. (-nī): Dalatānī ‘You have saved me’ (Ida-la-ta-ni-ˀ), Ḫannatānī ‘You have favoured me’ (Iḫa-an-na-ta-ni-ˀ).

Other predicates have the form of an imperfect, which is also referred to as the prefix conjugation:Footnote 49 Addu-yatin ‘May Adad give’ (Idad-du-ia-at-tin), Idā-Nabû ‘May Nabû know’ (Iid-da-ḫu-dAG), Aḫu-lakun ‘May the brother be firm’ (IŠEŠ-la-kun), Tammeš-linṭar ‘May Tammeš guard’ (Idtam-meš-li-in-ṭár).Footnote 50

Finally, verbal sentence names can contain an imperative: Adad-šikinī ‘Adad, watch over me!’ (IdIŠKUR-ši-ki-in-ni-ˀ), Nabû-dilinī ‘Nabû, save me!’ (IdAG-di-li-in-ni-ˀ).

Sentence names that consist of three elements sporadically occur. They are influenced by Akkadian fashion and even may incorporate an Akkadian element. An example hereof is the first element of the following name, which contains an Aramaic predicate with a G-stem imperfect 2.sg. m.:Footnote 51 Ša-Nabû-taqum ‘(By help?) of Nabû you will rise’ (Išá-dAG-ta-qu-um-mu).

Nominal Sentence Names

In nominal sentence names the subject generally takes the initial position. The object is often followed by the possessive suffix 1.sg. -ī; sometimes 2.sg. -ka:Footnote 52 Abu-lētī ‘The father is my strength’ (IAD-li-ti-ˀ), Abī-ilaḫī ‘My father is my god’ (IAD-i-la-ḫi-ˀ),Footnote 53 Tammeš-ilka ‘Tammeš is your god’ (Idtam-meš-ìl-ka), Nanāya-dūrī ‘Nanāya is my bulwark’ (Idna-na-a-du-ri-ˀ),Footnote 54 Iltehr-naqī ‘Iltehr is pure’ (Idil-te-eḫ-ri-na-aq-qí-ˀ), and Nusku-rapē ‘Nusku is a healer’ (IdPA.KU-ra-pi-e).

Sentence names that form a question are of nominal nature as well. They either start out with the interrogative pronoun ˁayya ‘where?’ or with man ‘who?’Footnote 55: Aya-abū ‘Where is his father?’ (Ia-a-bu-ú), Mannu-kî-ḫāl ‘Who is like the maternal uncle?’ (Iman-nu-ki-i-ḫa-la).

Compound Names

This type of name consists of two nominal components in a genitive construction. Nominal components can be regular nouns, kinship terms, deities, or passive participles:Footnote 56 Abdi-Iššar ‘Servant of Iššar’ (Iab-du-diš-šar), Aḫi-abū ‘His father’s brother’ (IŠEŠ-a-bu-ú), and Barik-Bēl ‘Bēl’s blessed one’ (Iba-ri-ki-dEN).

Hypocoristica

The hypocoristic suffix -ā, written -ˀ or -h in Aramaic and -Ca-a/ˀ in Akkadian, is added to most nominal sentence names and compound names. It may be like the Aramaic definite article that is of similar form and is suffixed to nouns as well. Hypocoristic -ā became so popular during the first millennium BCE that it replaced other hypocoristic suffixes common during the previous millennium. Moreover, it started to be attached to Arabian and Akkadian names as well.Footnote 57 Aramaic examples – with a translation of their nominal bases – are: Abdā ‘Servant’ (Iab-da-ˀ), fBissā ‘Cat’ (fbi-is-sa-a), Ḫarimā ‘Consecrated’ (Iḫa-ri-im-ma-ˀ), Zabudā ‘Given’ (Iza-bu-da-a), and Iltar-gadā (Iltar + fortune; Iil-tar-ga-da-ˀ).

Hypocoristic names with suffix -ī tend to be Aramaic. It may be based on the gentilic or suffix 1.sg. and is written -y in Aramaic, which is rendered -Ci-i/ia/iá or -Ci(-ˀ) in Akkadian:Footnote 58 Abnī ‘Stone’ (Iab-ni-i), Namarī ‘Leopard’ (Ina-ma-ri-ˀ), Raḫimī ‘Beloved’ (Ira-ḫi-mì-i), and Barikī ‘Blessed’ (Iba-ri-ki-ia). Its phonological variant is -ē.

One of the hypocoristic suffixes partly replaced by -ā is -ān, written -Ca-an(-nu/ni), -Ca-(a-)nu/ni:Footnote 59 Nabān ‘Nabû’ (Ina-ba-an-nu), Binān ‘Son’ (Ibi-na-nu).

A great deal of variety is achieved by adding combinations of two of these suffixes to nominal formations.Footnote 60

One-Word Names

Nearly all names that consist of one word are affixed with a hypocoristic marker. Exceptions are attested in various formations, which often are hard to distinguish due to inconsistent Babylonian spelling.Footnote 61

Naming Practices

As regards naming practice, it is striking that Babylonian theophoric elements appearing in the Aramaic onomasticon are not the ones prominent in contemporaneous Babylonian names. For instance, hardly any Aramaic names in the Murašû documentation contain the theophoric element Enlil, while this Babylonian deity enjoyed immense popularity in the Nippur area at the time.Footnote 62 This also is the case for Enlil’s son Ninurta (attested only once) and for Marduk, Nergal, and Sîn. Babylonian gods that are found in greater numbers in Aramaic names are Nabû, who takes second position after Tammeš in Nippur’s Aramaic onomasticon, as well as Bēl and Nanāya. Interestingly, Nabû primarily appears in patronyms, which indicates a decline of his prevalence.Footnote 63

In feminine names, a tendency of different order stands out. Although suffixes -t, -at, -īt, and -ī/ē are attested, there seems to have been a strong preference for feminine names ending in -ā:Footnote 64 fBarukā ‘Blessed’ (fba-ru-ka-ˀ), fGubbā ‘Cistern’ (fgu-ub-ba-a), fḪannā ‘Gracious’ (fḫa-an-na-a), fNasikat ‘Chieftess’ (fna-si-ka-tu4), fDidīt ‘Favourite’ (fdi-di-ti), and fḪinnī ‘Gracious’ (fḫi-in-ni-ia).

Tools for Identifying Aramaic Names in Cuneiform Sources

Various Aramaic verbs have surfaced in the examples. A more extensive – although not exhaustive – overview of verbs commonly attested in Aramaic names is presented in Table 8.1.

| Regular verbs | Irregular verbs | |

|---|---|---|

| brk – to bless | ˀmr – to say | ngh – to shine |

| gbr – to be strong | ˀty – to come | nṭr – to guard |

| zbd – to give, grant | bny – to build, create | nsˀ – to raise |

| zbn – to redeem | brˀ – to create | nṣb – to place |

| zrḥ – to shine | gˀy – to be exalted | ntn – to give |

| sgb – to be exalted | gbh – to be exalted | ˁny – to answer |

| smk – to support, sustain | ḥwr – to see | pdy – to ransom, redeem |

| srḥ – to be known | ḥzy – to see | ṣwḥ – to shout |

| ˁdr – to help, support | ḥnn – to be gracious, favour | qwm – to rise |

| ˁqb – to protect | ḥṣy – to seek refuge | qny – to get, create, build |

| rḥm – to love, have mercy | ybb – to weep | rwm – to be high |

| rkš – to bind, harness, tie up | ydˁ – to know | rˁy – to be pleased, content |

| šlḥ – to send | yhb – to give | rpˀ – to heal |

| šlm – to be well | ypˁ – to be brilliant | šly – to be tranquil |

| šmˁ – to hear | yqr – to be esteemed | šˁl – to ask |

| tmk – to support | mny – to count | šry – to release |

Nouns that regularly appear in nominal sentence names are presented in Table 8.2.Footnote 65

Nouns that typically appear in compound names are given in Table 8.3.

Table 8.3 Nouns attested in Aramaic compound names from the Neo- and Late Babylonian periods

| *ˀab | father | ˀb |

| *ˀaḥ | brother | ˀḥ |

| *ˀamat | female servant | ˀmt |

| *bVr | son | br |

| *bitt | daughter | brt |

| *gē/īr | patron, client | gr |

| *naˁr | servant, young man | nˁr |

| *ˁabd | servant | ˁbd |

The outline of elements of which Aramaic names may consist (presented in the section ‘Typology of Aramaic Names’) and these tables may give a taste of what such names could look like. If one suspects a name to be Aramaic, either the indices of Reference ZadokRan Zadok (1977, 339–81) may be checked, or Reference Zadok, Stökl and WaerzeggersZadok 2014, which includes attestations from later publications as well (the latter in a searchable PDF). As names have not been transcribed, use the Akkadian spelling for a search.