With ample evidence demonstrating the negative effects of student loan debt on young Americans’ long-term financial outlook, career choices, family-formation potential, and mental well-being, the electoral consequences of this increasingly prevalent financial burden merit examination (Chapman Reference Chapman2016; Cooper and Wang Reference Cooper and Wang2014; Walsemann, Gee, and Gentile Reference Walsemann, Gee and Gentile2015). The average level of student debt at graduation is at a record high of $37,650 (US Department of Education 2024). Even adjusting for inflation, the average level of student debt at graduation has increased substantially during the past several decades (Hanson Reference Hanson2024a). In addition, a strong majority (approximately 59% in 2023) of individuals earning a bachelor’s degree graduate with student loan debt (Wood Reference Wood2024). The scale and rapid growth of this debt burden underscores its potential impact on voter behavior, particularly among undergraduates who are new to both voting and living with student debt.

Meanwhile, student debt relief programs have become increasingly commonplace in recent years. After the Trump administration paused loan payments and interest accrual during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Biden administration temporarily extended that pause through September 2023 and successfully approved approximately $32 billion in targeted student debt forgiveness programs. The Biden administration also attempted to enact a more sweeping student debt forgiveness program under the Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions (HEROES) Act, which would have forgiven up to $20,000 in debt in loans disbursed by June 30, 2022, for certain borrowers and reduced the debt of about 30 million borrowers. However, this plan was struck down by the US Supreme Court in Biden v. Nebraska in June 2023 (Claremont McKenna College N.D.; Knott Reference Knott2023). In the following 16 months leading up to the 2024 presidential election, the Biden administration repeatedly held that it intended to implement another program of similar scope under the Higher Education Act of 1965. In light of the failure to implement this sweeping debt relief program before the 2024 election, we leveraged a representative survey of undergraduates at a large private university in the Northeast that was conducted when Joe Biden was still seeking the Democratic nomination. The purposes of the survey were to examine how (1) undergraduates’ support for Biden’s executive actions relating to student debt correlated with their support for him in the 2024 election; and (2) additional debt relief would have affected the voting behavior of undergraduates with student loan debt in November 2024 if Biden had remained in the presidential race.

EXISTING STUDIES AND EXPECTATIONS

Many researchers have explored the impacts of student debt on the behavior of college students as well as the broader influence of relief programs on voting decisions. The literature suggests that student debt places significant stress on students and substantially alters their daily behaviors. Given that such stress tends to remain with those who continue to hold debt long after graduation, it is no surprise that the political behavioral implications of debt relief have been shown to be wide reaching—influencing voter attitudes, political engagement, and overall public-policy preferences. This section reviews the current literature on these related topics, focusing on how student debt and related relief proposals impact undergraduate behavior, voter support, and broader societal attitudes.

Research consistently shows that student debt influences a range of daily behaviors and academic decisions among undergraduates. Students who face high levels of debt frequently engage in cost-cutting behaviors such as skipping meals, forgoing required textbooks, and avoiding medical care, with the most severe strain reported among those from a lower-income background (Norvilitis and Linn 2021). Higher student loan debt also is associated with an increased likelihood of reducing course loads or temporarily withdrawing from school, particularly among first-year students who often report greater emotional strain from borrowing (Robb, Moody, and Abdel-Ghany Reference Robb, Moody and Abdel-Ghany2012). Although extremely high debt levels are not consistently predictive of higher dropout rates, the psychological impact of debt is evident across a wide range of students. These patterns underscore how debt—in both its financial and emotional dimensions—can disrupt academic persistence and well-being.

Unsurprisingly, evidence also reveals that student debt affects political engagement among undergraduates. One qualitative study of 70 students revealed the ways in which student debt influences their political actions and participation in public life (Nissen Reference Nissen2018). Although the study was conducted in New Zealand, it nevertheless generally revealed important political behavioral consequences of student debt, finding that it often divides students and entrenches inequality, affecting their ability to engage politically (Nissen Reference Nissen2018).

Whereas student debt clearly shapes the daily lives and academic decisions of undergraduates, its impact obviously extends far beyond college campuses. Debt burdens influence political attitudes and engagement among all borrowers, making debt-relief policies a significant factor in broader electoral and policy debates. Many researchers have explored these political implications.

Understanding the specific details of student debt relief proposals is important in anticipating how they might affect voter attitudes and behavior. There is a clear partisan divide in support for debt forgiveness and candidates who back such proposals. However, plans that offer higher amounts of debt forgiveness and broader eligibility criteria generally have been shown to garner greater voter backing (Manion Reference Manion2023; SoRelle and Laws Reference SoRelle and Laws2023). In addition, the political impact of eligibility criteria has relevance beyond the broadness or narrowness of debt-relief policies: voters’ perceptions of the deservingness of recipient groups greatly impacts their support or opposition to proposals (SoRelle and Laws Reference SoRelle and Laws2024). Among Democratic-leaning voters, support for debt forgiveness tends to be influenced by sympathetic perceptions of borrowers’ financial need and histories of consistently repaying their loans over time (SoRelle and Laws Reference SoRelle and Laws2024). The Biden administration’s informally proposed debt-relief plan—which likely would have included income caps and additional benefits for Pell Grant recipients—aligned with perceptions of need and reciprocity among potential Democratic voters (SoRelle and Laws Reference SoRelle and Laws2024). This evidence suggests that executive actions on student debt, such as those that were floated by the Biden administration, have the potential to bolster Democratic electoral chances in upcoming elections because they would appeal to the values and concerns of the Democratic voter base (SoRelle and Laws Reference SoRelle and Laws2023, Reference SoRelle and Laws2024).

In addition to voters’ self-reported support for hypothetical student debt relief proposals, other research reveals the substantive impact that such relief has on the lives of recipients. One study shows that higher levels of forgiveness affect financial behaviors, such as paying down other debts, saving for emergencies, and making large purchases (Roll, Jabbari, and Grinstein-Weiss Reference Roll, Jabbari and Grinstein-Weiss2021). During the COVID-19 payment pause, those with paused student debt felt more optimistic about their financial future compared to before the pause (Bright and Barany Reference Bright, Barany, Damşa and Barany2023). Thus, debt relief enhances financial freedom and hopefulness, potentially influencing political behavior as individuals hold officeholders accountable for improving their lives (Bright and Barany Reference Bright, Barany, Damşa and Barany2023; Roll, Jabbari, and Grinstein-Weiss Reference Roll, Jabbari and Grinstein-Weiss2021). These benefits are especially consequential for young adults with student debt, who are significantly more likely than their peers without such debt to struggle with credit constraints, late bill payments, and a lack of emergency savings (Bricker and Thompson Reference Bricker and Thompson2016; Gicheva et al. Reference Gicheva, Thompson, Hershbein, Hollenbeck, Hollenbeck and Hershbein2015). They also are less likely to own a home or vehicles, and they face long-term losses in retirement savings and wealth accumulation (Hiltonsmith Reference Hiltonsmith2013; Houle and Berger Reference Houle and Berger2015). For these borrowers, debt-relief policies do more than simply ease financial strain—they also can provide a critical pathway toward economic stability, long-term planning, and greater political empowerment.

Drawing on this existing literature, we expected that support for student debt relief would cause students to view Joe Biden more favorably and would have made them more willing to indicate support for his candidacy. Thus, our hypotheses were as follows:

H1: Support for Joe Biden in the 2024 election was substantially higher among undergraduates who believe his actions relating to student loan debt have been adequate when compared with students who believe he has done too little or too much.

H2: Students with debt who indicated that Biden was not their first choice for president would have been significantly more likely to vote for him if some of their debt had been canceled before the November election, had he stayed in the race.

H2a: Among this group of students, those who ranked Biden lower in a hypothetical ranked-choice scenario would have been less persuaded by additional debt forgiveness to vote for him than would those who ranked him more highly.

DATA

To test H1, we examined the extent to which views on the Biden administration’s actions on student loan relief translated to expected vote choice in the 2024 election by leveraging an original survey of students conducted between March 13 and March 21, 2024, at a large private university in the Northeast (see Harrison and Smith Reference Harrison and Jacob2025). We distributed the survey via email through a Qualtrics link to a random sample of students. We used the random-number generator available at www.random.org to select which 20% of the undergraduate student body to email and sent the survey to 1,952 students. We followed up with a reminder email several days after the initial invitation to participate in the survey. Students were told that those who participated had the option of providing an email address at a different link to be entered into a survey to win one of five $100 Amazon gift cards. Approximately 20% of those who were randomly selected to participate ultimately responded, resulting in a total sample of 472 students.Footnote 1 Our subsample decreased to 336 students when we considered only those students who were registered voters.Footnote 2 The sample was broadly representative of the student population at this university, although 32.4% of respondents identified as male compared to approximately 39.7% of the student body.Footnote 3

The racial and ethnic composition of the sample also closely mirrored that of the university and was relatively similar to the broader US undergraduate population. Specifically, there were slightly fewer undergraduate students who identified as Black and slightly more who identified as Asian compared to the overall US undergraduate student body. Among registered voters in our sample, 44.9% identified as only white non-Hispanic, compared to 52.3% of all college students in 2022 using data compiled by the Education Data Initiative (Hanson Reference Hanson2024b). In our sample, 19.9% of students identified as Hispanic/Latine—a percentage similar to the 21.5% of all college students. Our sample had a higher percentage of students who identified as only Asian (i.e., 13.1% compared to 7.4% nationally) and a lower percentage of students who identified as only Black (i.e., 7% compared to 13.2% nationally) relative to the overall undergraduate student population. These percentages that reflect the racial and ethnic composition of our sample were similarly aligned with those of non-international students at the university, with slightly fewer white non-Hispanic students in the sample (i.e., approximately 45% compared to approximately 51% of the non-international student body). Notably, 36.2% of the respondents were commuter students; this percentage was lower than the percentage of the US student population that are commuters but higher than the percentage at most selective private universities (Jacoby Reference Jacoby2020; U.S. News and World Report 2024).

Approximately 53% of respondents who were registered voters had some level of debt; 35% did not have debt; and 12% did not respond to the questions necessary to determine whether they had debt. Among those students who indicated that they had taken out student loans, their median debt was between $20,000 and $30,000. This range is broadly reflective of the typical debt level at this particular university, which is somewhat lower than the national average debt of approximately $40,000 (Hanson Reference Hanson2024a). The typical debt amount in our survey also was likely lower because many of our respondents were earlier in their studies and may have taken on only a relatively small amount of debt or so far had none at all. Whereas first-years, sophomores, and seniors each represented slightly less than 25% of our sample, our data for registered voters overrepresented juniors (29.5%). In total, our sample was broadly representative of the populations at this university. Although some populations at this university differ from the overall US population, the relative diversity of the sample allowed us to make tentative conclusions that translated to some extent to the undergraduate student body more broadly.

METHODS

We began by considering whether students in our sample indicated that they planned to support Joe Biden in November. To conduct this analysis, we ran several logistic regression models using a series of dependent variables. First, we examined whether a student planned to vote for President Biden or another candidate in the 2024 election. Students could indicate support for President Joe Biden, former President Donald Trump, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the Libertarian nominee, the Green Party nominee, or an “Other” option. For “Other,” students could write-in who they planned to support; notably, some students wrote in that they did not plan to vote. We also included two other models, one in which the dependent variable examined support for Biden compared to Trump among students who selected one of the two major-party nominees and the other variable that compared support for Biden to support for Kennedy among students who selected one of those two options. Trump and Kennedy were the two most common non-Biden selections among students.

We constructed our focal independent variable from a question that examined views about the Biden administration’s actions on student loan debt relief. Specifically, we included two dummy variables, one for respondents who believed that the Biden administration had done enough to address the needs of those with student debt and the second for those who believed that it had done too much. A third variable indicating that the respondent believed that the Biden administration had done too little was left out as the baseline option. We used two dummy variables rather than a single ordinal measure to account for the possibility that those who thought Biden had done too much as well as those who thought he had done too little might be disinclined to support his candidacy. These three options provided an option for respondents to express dissatisfaction in either direction (i.e., too much or too little) or to indicate that they were generally satisfied with the actions of the Biden administration to help the needs of those with student debt.Footnote 4 We also included a series of control variables: a dummy variable indicating whether respondents were Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC); a five-point indicator of party (from very liberal to very conservative); a three-point measure of party (Democrat to Republican); two gender dummy variables (male and non-binary/other, with female left out as the baseline option); and an ordinal measure of a student’s class year (first-year to senior).

RESULTS

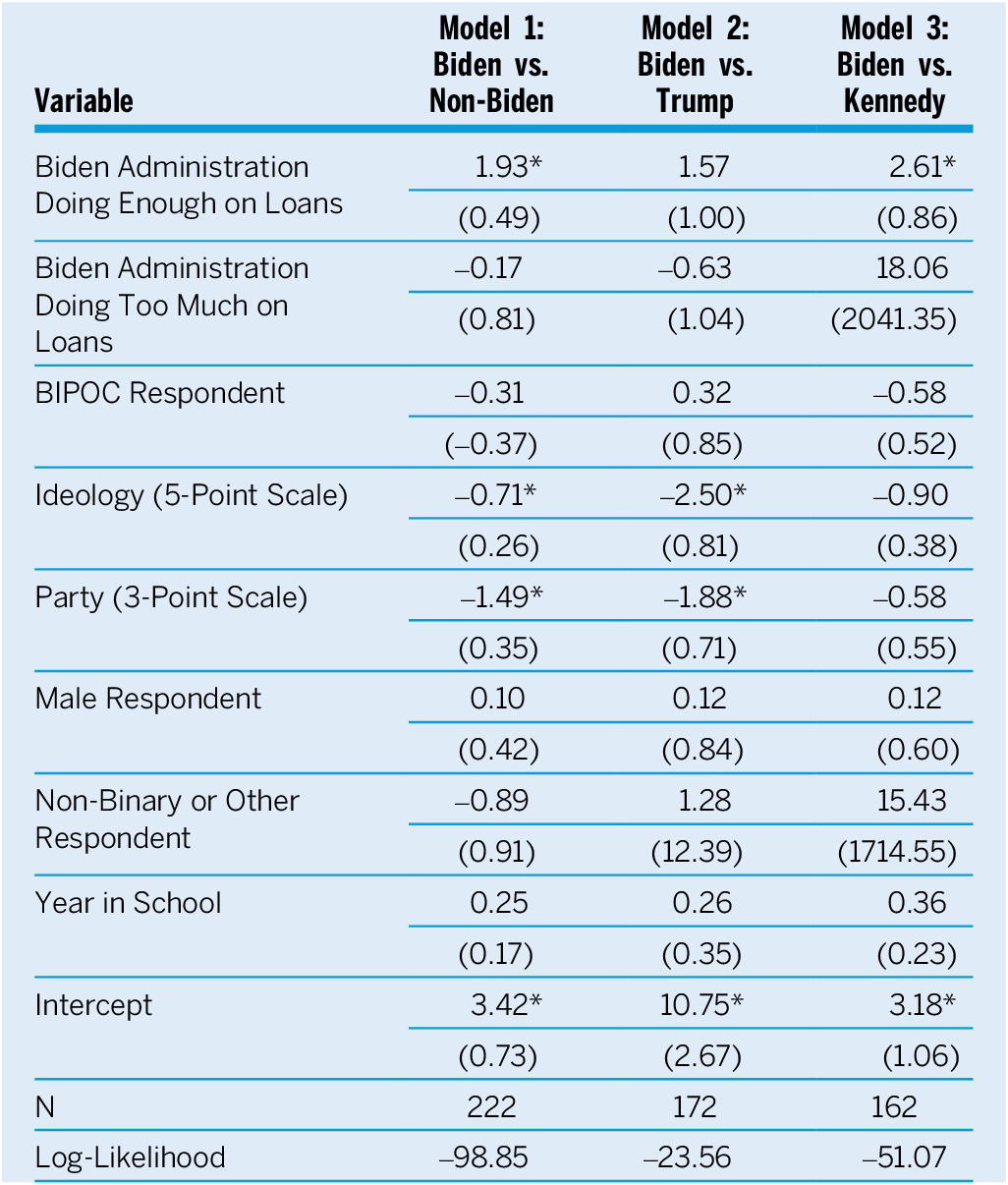

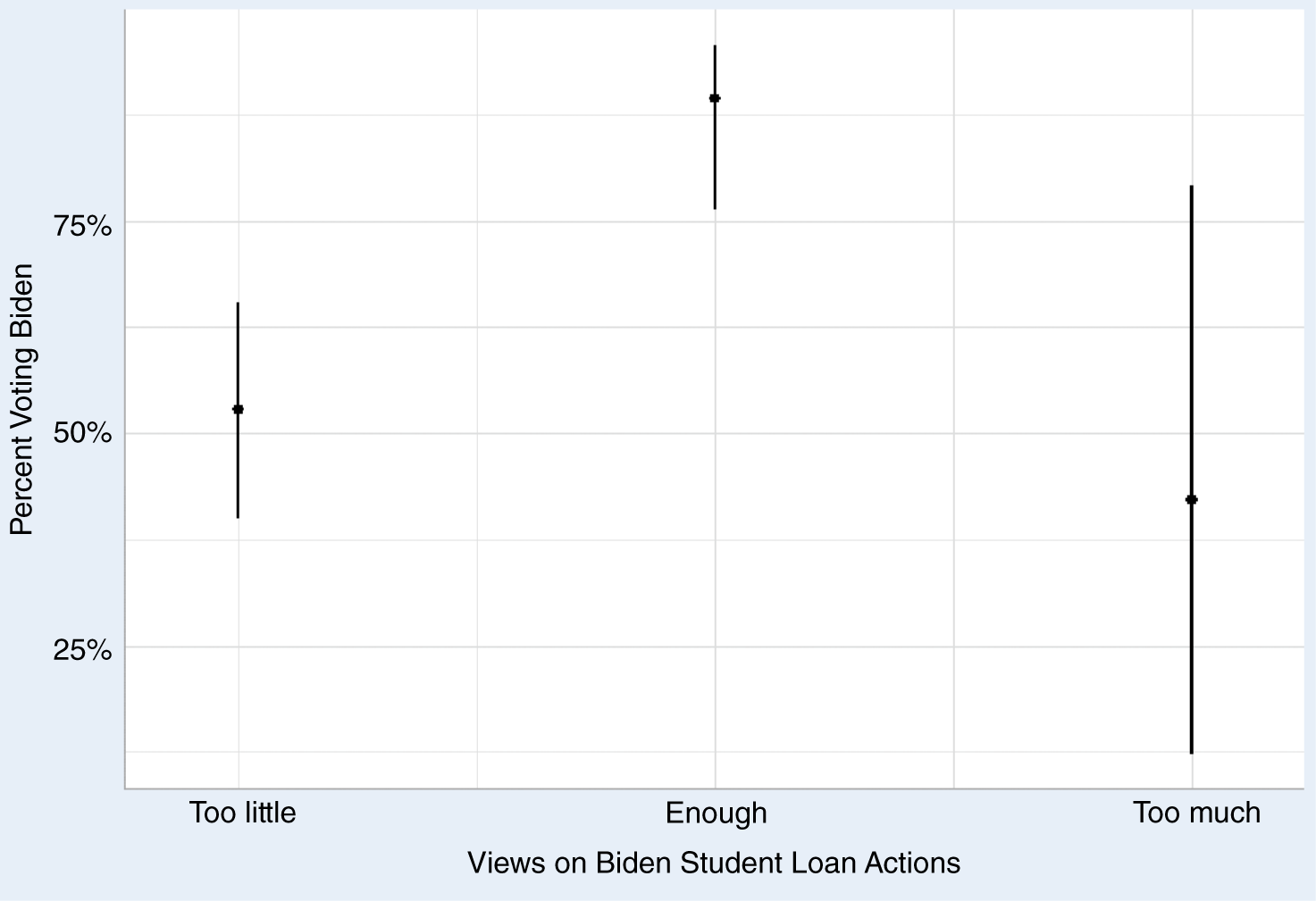

Table 1 displays our results. In our first model, in which the dependent variable measures support for Joe Biden compared to all other options, the focal independent dummy variable indicating that a respondent believed that the Biden administration had done enough on student loan relief attained statistical significance at the 95% confidence level. This result indicates that students who believe that the Biden administration had done enough on student loan relief were more likely than those who disagreed to state that they planned to support Biden compared to all other options (including not voting). There was no statistical difference in support for Biden when we compared those who believed that the administration had done too much and those who believed that it had not done enough. There also was a notable substantive difference in support for Biden when we compared the “enough” and “not enough” groups (figure 1). Specifically, when ordinal control variables are set at their mean value and other control variables are set at their modal value, support for Biden increased from 54% among those who believed that his administration was not doing enough on student loan relief to 89% among those who thought that it was doing enough on student loans.Footnote 5 Among our control variables, only party and ideology attained significance; not surprisingly, conservatives and Republicans were less likely to indicate support for Biden.

This result indicates that students who believe that the Biden administration had done enough on student loan relief were more likely than those who disagreed to state that they planned to support Biden compared to all other options (including not voting).

Table 1 Views on Biden 2024 Election Results and Support for Biden in 2024

Notes: *p<0.05. The dependent variable measures support for Joe Biden in several scenarios.

Figure 1 Predicted Probability of Voting for Joe Biden

Variables are set at mean or modal value.

We also ran models that examined only major-party voters (Biden versus Trump) and those who indicated that they supported Biden or Kennedy. Given the Trump administration’s policies on student loans, it did not follow that believing that the Biden administration had not done enough on student loans would lead a student to support Donald Trump. Consistent with this logic, the dummy variable for stating that the Biden administration had done enough, albeit positive, did not attain statistical significance in this model. In contrast, this measure did reach significance in the Biden/Kennedy model. Kennedy has relatively heterodox views on student loan debt that, in theory, could have caused an increase in support, but his specific views may not have been especially well known.Footnote 6 In the Trump model, party identification and ideology again attained significance. It is interesting—and perhaps because of the long-standing association of the Kennedys with the Democratic Party—that neither party nor ideology attained significance at the 0.05 level in the Kennedy model (although ideology reached significance at a less-strict 0.1 standard).

Findings on Race and Ethnicity

A somewhat surprising finding from our survey was the null result for the race and ethnicity variables. The dichotomous variable indicating whether a respondent was BIPOC did not reach significance in any of the three models. Furthermore, when we ran models with separate race and ethnicity categories, none of these variables attained significance.Footnote 7 Our findings contrast with a long history of research demonstrating strong support among BIPOC voters (in particular, Black voters) for Democratic candidates. Although our sample as a whole was diverse, our results for Black voters in part may be a result of their small number in our sample. For example, in Model 1, only 17 respondents were Black (of 222 total) and that number decreased to 10 (of 172 total) and 11 (of 162 total) in Models 2 and 3, respectively. At the same time, an analysis of AP VoteCast data by the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (2024) revealed that Trump won almost 25% of 18- to 29-year-old Black voters, a higher percentage than the 16% of all Black voters the VoteCast survey estimated that he won nationally (Lodhi et al. Reference Lodhi, Cheng, Kaufmann, Urenda and Fox2024). Vice President Kamala Harris also won a slightly higher percentage of white 18- to 29-year-olds than white voters in general. In particular, white voters attending a private university in the Northeast were likely to be more progressive than a typical white 18- to 29-year-old. Nevertheless, the small number of students of color (in particular, Black students) requires caution when we consider the generalizability of our results.

Does It Matter If a Student Has Debt?

Our survey included a question that allowed us to determine whether a student currently had debt. If our sample had been larger, a logical next step would have been to run separate models based on current student-debt status. However, the relatively small number of students who fell into subgroups, such as whether they currently had debt, made including separate models inadvisable. Nevertheless, a closer examination of support for Biden among those who thought his administration was not doing enough on student loans suggests that student-loan status might be an important factor to consider in future research. Among those who thought that Biden was doing too little on student debt but currently did not have student loans, 65.3% supported him over another candidate (32 of 49 respondents). In contrast, among those who thought that Biden was doing too little on student debt but currently did have student loans, Biden received 53.8% (43 of 80 respondents). Nevertheless, support among all respondents who thought that the Biden administration was doing too little on student loans was lower than support among those who thought that it was doing enough: 84% of respondents (53 of 63 respondents) indicated support for Biden. Even among those who had loans but thought that the Biden administration was doing enough to address student debt, support remained relatively high at 78.6% (33 of 42 respondents). The relatively low support for Biden among those who thought that his administration was not doing enough on student loans but currently did not have loans could be a result of anticipating a need for student loans in the future, solidarity with friends or classmates who had loans, or a stand-in for broader frustrations with the Biden administration.

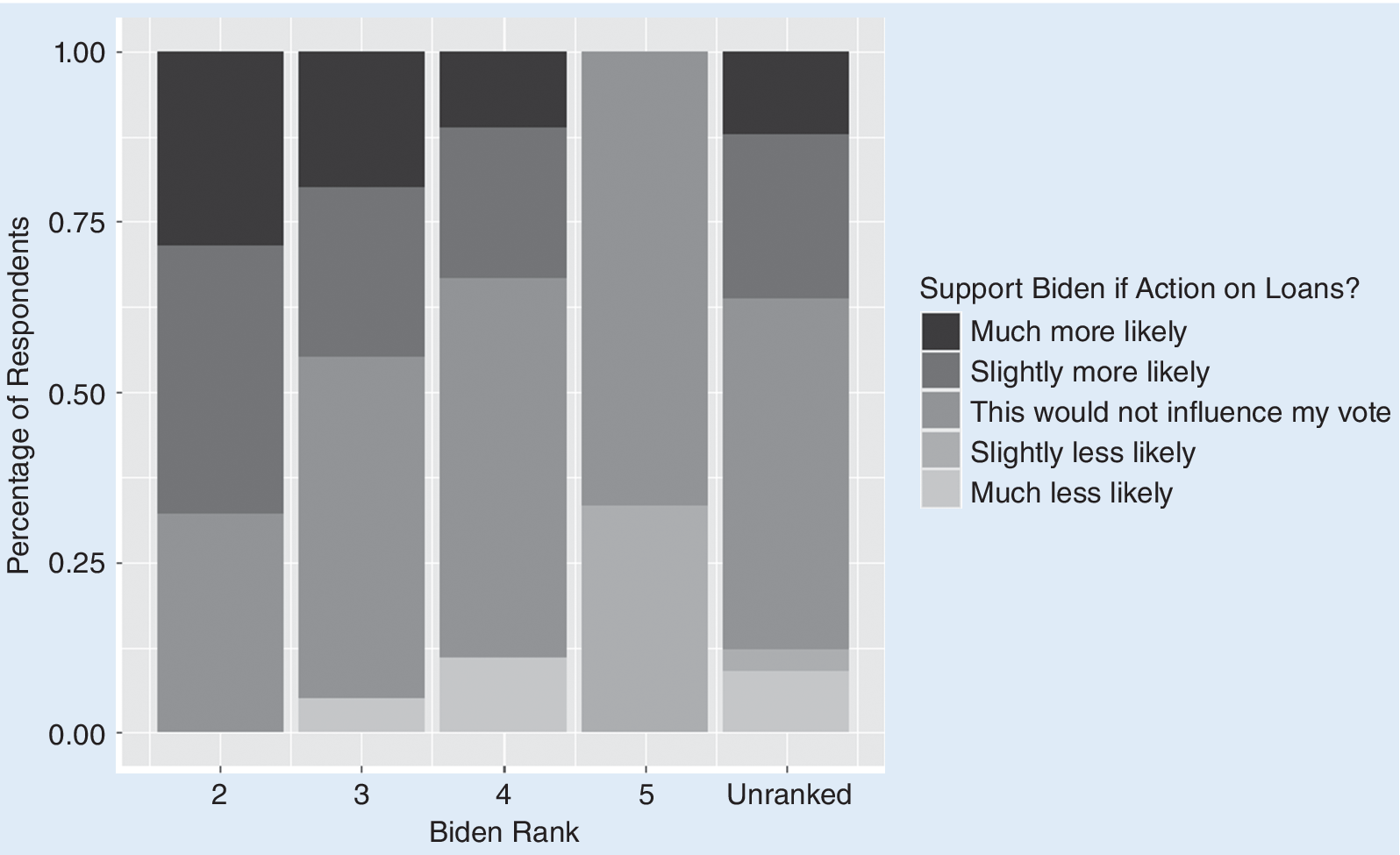

Are the Voters Who Did Not Rank Biden First Persuadable?

The next question we asked was whether the Biden campaign could have won the support of those voters with student debt who indicated that they did not plan to support him by taking additional actions on student loans. The survey also included a question asking respondents to rank their top five candidates under the hypothetical scenario that the election used rank-choice voting like the system in New York City. Separately, students also were asked if they would be more or less likely to support Joe Biden if the administration took additional actions on student loans. Figure 2 examines the second through fifth choices of respondents alongside their answer to the question about support for Biden based on action on student loans. Consistent with H2, voters who did not rank Biden first stated that they would have been more likely to if there were to be additional action on student-loan forgiveness. For second-choice Biden voters with debt, 28.6% indicated that additional action on student loans would make them much more likely to support him; 39.3% indicated that further action would make them slightly more likely. At the same time, slightly less than 33% of second-choice Biden respondents with debt stated that it would not impact their vote; none stated that it would make them less likely to support him. The majority of second-choice Biden voters with debt ranked either Kennedy (50%) or the Green Party candidate (21.4%) first. Among Kennedy voters, 50% stated that they did not think the Biden administration was doing enough on student loans and 100% of Green Party supporters who answered this question also believed that it was not doing enough. For those voters with debt who ranked Biden third, 20% of respondents indicated that additional action on student loans would make them much more likely to support him; 25% indicated that additional action would make them slightly more likely. However, 50% of third-choice Biden voters stated that such action would not impact their vote. These results suggest that among voters who would have considered Biden but did not rank him first, there was dissatisfaction with his administration about student-loan policy and that additional action potentially could have won the support of some of them.

Figure 2 Rank and Support for Biden Based on Action on Loans

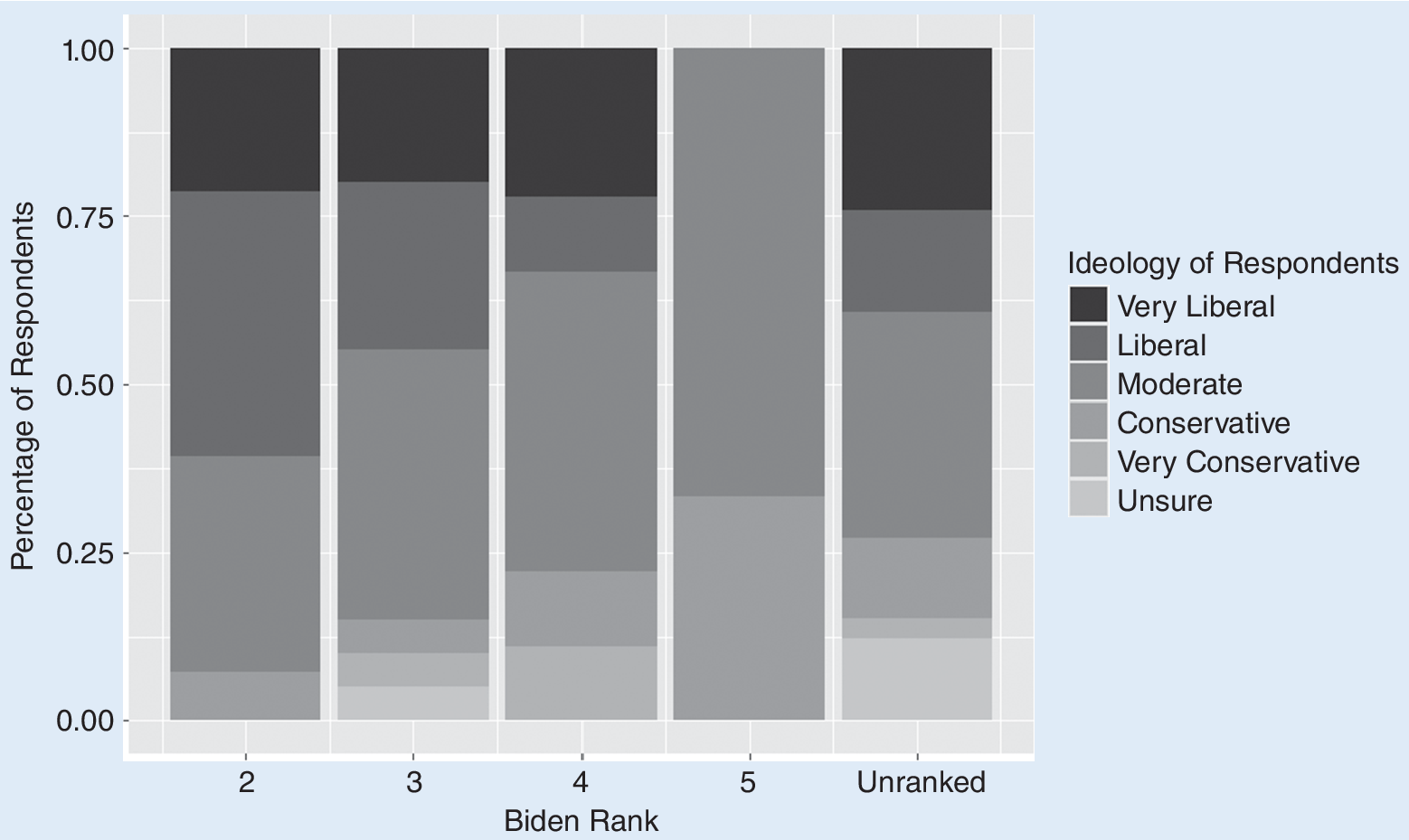

In keeping with H2a, these results demonstrate that voters with debt for whom Biden was a second and third choice were relatively more likely to state that they were more likely to support Biden if there were to be additional action on student loans than those who ranked him lower. Additionally, second- and third-choice Biden voters were relatively more liberal than those who ranked him fourth or fifth. However, as shown in figure 3, there was a small group of very liberal respondents with debt who did not rank Biden at all, indicating that a small group of those on the left were likely impossible to win over based only on action on student loans. The percentage of very liberal respondents was relatively steady at the second, third, and fourth rankings, even as the percentage of liberals decreased (i.e., liberals were particularly likely to rank Biden second if they did not already rank him first). Indeed, when considering the persuadability of voters who did not rank Biden first, 58.3% of very liberal voters indicated that further action by his administration on student loans would not affect their vote in 2024 compared to 27.3% of liberals who stated the same. The remaining respondents stated that additional action would make them either somewhat or much more likely to support Biden.

Figure 3. Ideology and Biden Rank

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Among undergraduate students in our survey, support for the executive actions of President Joe Biden relating to student debt shared a strong correlation with support for him in the 2024 presidential election. Additionally, although believing that Biden had done “too little” on student debt did not correlate with a heightened probability of support for his main opponent, Donald Trump, it did correlate with regard to Robert F. Kennedy Jr. We found support for H1 in our data. Whereas the exact extent to which Biden’s electoral support among undergraduate students was motivated by his actions related to student debt is unclear, our research along with other polling data indicates that fluctuations in support for Biden among young people closely followed his history of acting on this issue.

Whereas the exact extent to which Biden’s electoral support among undergraduate students was motivated by his actions related to student debt is unclear, our research along with other polling data indicates that fluctuations in support for Biden among young people closely followed his history of acting on this issue.

When the Biden administration announced its plan in August 2022 to forgive up to $20,000 in student loans for individual borrowers, polling data showed that he received a considerable 6.6-point increase in approval among younger Americans (Graham Reference Graham2022).Footnote 8 Because that plan was delayed in the legal system before eventually being struck down, Biden’s approval among young people decreased by 9 points and declined further until the end of his presidency (Cilluffo Reference Cilluffo2019; Pew Research Center 2024). One poll indicated that Biden held only a 9-point lead over Trump among eligible voters younger than 30 before leaving the race. This was a substantially smaller margin than in 2020, when exit polls showed that Biden won with a 24-point margin over Trump with the same demographic (Harvard Kennedy School, Institute of Politics 2024; Lenski, Webster, and Brown Reference Lenski, Webster and Brown2021).

Despite Biden’s significant loss of support among young people, our data show that he may have been able to reclaim the backing of many young voters who had student debt by taking executive action to forgive some of their loans before November. This finding supports H2 and H2a. The potential increase in support was most notable among liberal and—to a slightly lesser extent—very liberal young voters. Polling data indicate that the youngest demographic of potential voters held overwhelmingly negative views toward President Biden’s handling of the Israel–Hamas War, whereas his age was a rising concern more generally among Americans (Harvard Kennedy School, Institute of Politics 2024; Jackson, Newall, and Rollason Reference Jackson, Newall and Rollason2024). Regarding the former issue, left-leaning young people comprised the most likely group to hold the view that Biden had been too supportive of Israel in the conflict, manifesting in nationwide pro-Palestinian campus protests in April 2024 (Bump Reference Bump2024). Our analysis reveals that student-debt relief could have incentivized many of these young progressives with student debt to vote for Biden in November. Because we conducted this survey in March 2024 before the protests took place, we did not include questions about the war. However, Pew Research Center survey data show that negative feelings toward the Biden administration regarding this issue had begun to intensify among young voters in early 2024 (Silver Reference Silver2024).

Despite Biden’s significant loss of support among young people, our data show that he may have been able to reclaim the backing of many young voters who had student debt by taking executive action to forgive some of their loans before November.

When assessing the potential voting behavior of young people more generally, it is difficult to determine whether the polling increase that Biden experienced after he announced his first sweeping debt-forgiveness plan in August 2022 would have been replicated by a successful similar executive action before November. Given the ongoing Israel–Hamas War and rising concerns about Biden’s age, among other issues, the precise extent to which additional debt relief could have benefited him electorally with regard to young voters is unclear based on our data. Our evidence certainly suggests, however, that an increased focus on student debt relief policies could have motivated many more to vote for Biden in November—even as external factors added uncertainty to his electoral prospects among the demographic on which this study focuses and, of course, more broadly. We recommend that future research explore more broadly the potential electoral impact of student debt relief policies because we examined only a small subsection of a large group of voters who share this financial burden in the United States.

Finally, given that the Democratic Party switched to a new General Election candidate in Vice President Kamala Harris, we encourage researchers to examine how additional student-debt relief from the Biden administration before November may have impacted her electoral chances. Because we conducted our survey well before the switch, any conclusions are only tentative. However, surveys conducted after the switch demonstrated increased enthusiasm for Vice President Harris compared to when President Biden was the likely Democratic nominee (Paz Reference Paz2024). Nevertheless, Harris still lost and, in particular, lost ground with young voters compared to Biden’s 2020 performance. Harris’s 54% of the vote with young voters fell short of the at least 60% that recent Democratic nominees received with 18- to 29-year-olds (Moore Reference Moore2024). Youth turnout also declined in 2024 (Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement 2024). An increased focus on student-loan policy by the Harris campaign, combined with action from the Biden administration, may have prevented such a sharp decline. We also encourage researchers to examine the political behavioral consequences of policies that achieve the inverse of student-loan forgiveness, such as those implemented by the Trump administration through actions including blocking income-driven repayment plans and narrowing eligibility for public service loan forgiveness (Salam Reference Salam2025). With many borrowers’ monthly payments increasing substantially under the Trump administration, the impact of such policies on the voting behavior of those with debt merits examination.

Our survey is only one sample of a specific group of young voters: those pursuing a college degree at a private university in the Northeast. Nevertheless, our sample includes a relatively diverse group of students in terms of race, gender, commuter status, year in school, and debt burden. Thus, although we cannot make conclusions about every young person or even every college student in America, our survey provides insight about the role of student-debt policy as students prepared to vote in their first or second presidential election. In summary, our research indicates that at least in our sample, (1) support for President Biden among undergraduates with student debt in the United States correlated strongly with support for his actions relating to student debt; and (2) he (or Vice President Harris) potentially could have regained significant electoral support among undergraduate students with student debt by taking executive action to forgive student debt, especially from liberal voters.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096525101236.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for support from a Fordham Undergraduate Research Grant. We also thank audience members at the 2024 Fordham Undergraduate Research Symposium and our reviewers at PS for helpful feedback on this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/II0JJ9.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.