Normative arguments supporting the election of more women to political office maintain that women are uniquely positioned to advocate for the interests of women more broadly through acts of substantive representation, such as passing bills that reduce gender inequities, and symbolic representation, such as speaking on behalf of women and girls’ interests on the House or Senate floor (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge2003; Dovi Reference Dovi2002; Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler Reference Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler2005). Political pundits and media commentators reinforce the notion that women bring a distinct and unique voice to politics. As Martha MacCallum aptly put it in 2018 on her namesake show on Fox News:

Women candidates have been so successful because they do bring a perspective that people can relate to. They are good at building consensus, working across the aisle, and they understand those issues because women are often the ones who make those economic decisions for our families…I think it would be something that American voters are eager to see.

Past research finds that women legislatorsFootnote 1 build consensus around shared interests, compromise on legislation, and represent women’s interests through the bills they sponsor and co-sponsor (Volden, Wiseman, and Wittmer Reference Volden, Wiseman and Wittmer2013; Barnes Reference Barnes2016; Holman, Mahoney, and Hurler Reference Holman, Mahoney and Hurler2022; Holman and Mahoney Reference Holman and Mahoney2019) and through symbolic acts such as floor speeches that focus on women and girls (Dietrich, Hayes, and O’Brien Reference Dietrich, Hayes and O’Brien2019; Pearson and Dancey Reference Pearson and Dancey2011a, Reference Pearson and Dancey2011b). Women, however, do not always support women’s issues in Congress (Cowell-Meyers and Langbein Reference Cowell-Meyers and Langbein2009; Dodson Reference Dodson2006). Existing work suggests that voters hold legislators accountable for their legislative outputs (Grimmer, Westwood, and Messing Reference Grimmer, Westwood and Messing2014), and that voters evaluate women legislators positively when those legislators behave in ways that match the policy interests of their districts (Kaslovsky and Rogoswki Reference Kaslovsky and Rogoswki2022). Yet, it is not clear how voters respond when women fail to act in accordance with these gendered expectations about their legislative priorities. This is the question we aim to answer in this paper.

We use an original content analysis of cable news coverage and two unique survey experiments to track whether voters hold gendered expectations for women leaders. We find three key patterns. First, the media set a clear narrative that leads to the expectation that women in political office will substantively represent women’s interests as a group. Second, voters reward both women and men who vote in favour of legislation thought to influence and benefit women as a group. Third, women voters punish both women and men legislators who fail to support women’s interests. Our research has powerful implications for understanding the links between descriptive and substantive representation, women’s political interests, and the way voters evaluate women in office. We show that voters care about the substantive representation of women’s political interests, but they care less about who supports these interests. We argue that this means that legislators have strategic opportunities to advance women’s substantive representation regardless of their gender.

Gender and Electoral Accountability

Women in Congress bring home more federal dollars to their districts (Anzia and Berry Reference Anzia and Berry2011) and pass more legislation relative to men legislators (Volden, Wiseman, and Wittmer Reference Volden, Wiseman and Wittmer2013; Barnes Reference Barnes2016; Holman, Mahoney, and Hurler Reference Holman, Mahoney and Hurler2022; Holman and Mahoney Reference Holman and Mahoney2019). Much of the legislation authored and co-authored by women, as well as the types of speeches made by women, focus on issues that disproportionately affect women as a group or highlight the gendered aspects of issues that do not appear to be ‘women’s issues’ (Swers Reference Swers1998; Dietrich, Hayes, and O’Brien Reference Dietrich, Hayes and O’Brien2019; Pearson and Dancey Reference Pearson and Dancey2011a, Reference Pearson and Dancey2011b; Swers Reference Swers2013; Atkinson and Windett Reference Atkinson and Windett2019). Outside the U.S. Congress, women in elected state and local political offices have strong records of securing economic benefits for their cities and prioritizing issues that disproportionately affect women (Holman Reference Holman2014; Funk and Phillips Reference Funk and Phillips2019; Osborn Reference Osborn2012).

Research on electoral accountability suggests that what legislators do in office matters for voter decision making and the impressions formed of legislators more broadly. Much of this work looks at accountability for legislators without regard to their personal characteristics (that is, gender; Canes-Wrone, Brady, and Cogan Reference Canes-Wrone, Brady and Cogan2002; Ansolabehere and Kuriwaki Reference Ansolabehere and Kuriwaki2022; Ansolabehere and Jones Reference Ansolabehere and Jones2010; Fenno Reference Fenno1978; Highton Reference Highton2019). New research on accountability and gender, using observational data, finds that women receive favourable evaluations as long as their votes and public positions on issues match constituent preferences (Kaslovsky and Rogoswki Reference Kaslovsky and Rogoswki2022; Payson, Fouirnaies, and Hall Reference Payson, Fouirnaies and Hall2023) and that women voters are particularly likely to reward women legislators with congruent policy positions (Jones Reference Jones2014). This scholarship, however, does not account for whether a woman leader took a position that benefited, or failed to benefit, women as a group. As the ideological and partisan diversity of the women serving in elected office increases (Reingold et al. Reference Reingold, Kreitzer, Osborn and Swers2021; Reingold et al. Reference Reingold, Kreitzer, Osborn and Swers2015; Matthews, Kreitzer, and Schilling Reference Matthews, Kreitzer and Schilling2020; Osborn et al. Reference Osborn, Kreitzer, Schilling and Clark2019), it is reasonable to expect that some women legislators may not support policies designed to advance women’s interests.

The literature on women’s legislative support for women’s issues does not always distinguish between the types of women’s issues women support. Stereotypic women’s issues can fall into two categories; issues that are thought to require feminine traits (Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993) and equity issues (Osborn Reference Osborn2012; Wolbrecht Reference Wolbrecht2000). Trait-based women’s issues are associated with women because these issues reflect the communal and caregiving roles that reinforce broader stereotypes about women. For example, education falls into this category because voters see these issues as requiring traits like being caring and warm, both feminine traits, and these issues are community-oriented, which also reflects the conventional caregiving social roles held by women. Equity issues disproportionately and directly affect women as a group (Osborn Reference Osborn2012; Celis et al. Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Mona Lena Krook2014), including pay equity, sexual harassment, and reproductive rights. Women are more likely to suffer negative effects from the policies advanced, or not, around these types of issues (Mandel and Semyonov Reference Mandel and Semyonov2014). While positions on stereotypic issues are important, positions on equity issues are those that normalize treating women as ‘autonomous, rights-bearing’ individuals (Caminotti and Piscopo Reference Caminotti and Piscopo2019), and understanding whether voters punish and/or reward women legislators for this kind of advocacy matters.

Both trait-based and equity-based women’s issues are most often associated with the Democratic Party (Petrocik, Benoit, and Hansen Reference Petrocik, Benoit and Hansen2003), though both Democrats and Republicans emphasize these issues during elections and in their legislative agendas (Sulkin Reference Sulkin2005). Indeed, Wineinger (Reference Wineinger2022) finds that many Republican congresswomen prioritize the same types of women’s issues as Democrats, but Republican women take different positions or focus on different facets of these issues. For example, Democrats typically advocate for more education funding, while Republican women often advocate for more parental control over children’s educations. Past research has yet to examine how voters might respond to Democratic women who vote against women’s interests, which is also a vote against a partisan-owned issue, or how voters respond to Republican women who use language about supporting women to vote against the interests of women as a group. We examine these dynamics.

Our research makes several key contributions to the literature on gender, descriptive representation, and substantive representation. First, we examine whether legislators have incentives to engage in the substantive representation of marginalized groups. Second, we examine whether voters who share characteristics with a legislator, shared gender in this case, provide incentives for that legislator to support the interests of their group. More specifically, do women voters reward women legislators who support the interests of women in their policy decisions? Finally, we highlight which lawmakers have incentives for supporting marginalized group interests as both women and men legislators often engage in the substantive representation of women’s interests.

Incentives, Sanctions, and Support for Women’s Interests

Theories of descriptive and substantive representation argue that members of underrepresented groups, such as women, are best positioned to advocate for the policy interests of those groups due to a set of shared experiences (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge2003; Dovi Reference Dovi2002; Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler Reference Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler2005). Bryant and Hellwege (Reference Bryant and Hellwege2018) found evidence of this shared identity effect in their research showing that when there are more mothers with small children in Congress, legislation designed to address children’s health is more likely to be sponsored by these women. Following this logic, women legislators should not only be those most likely to advocate for women’s interests, but if voters expect women to advocate for women’s interests, then women legislators should be rewarded for representing those interests.

Here, we suggest that voters’ expectations for women legislators encompass both women’s issues and women’s interests. Existing research conceptualizes women’s issues as a broad policy category encompassing two main areas: (1) areas traditionally associated with women due to gender stereotypes, like education and healthcare (Swers Reference Swers1998; Taylor-Robinson and Heath Reference Taylor-Robinson and Heath2003); and (2) matters directly related to advancing women’s rights, such as reproductive freedom, pay equity, and combating gender-based violence (Wängnerud Reference Wängnerud2000; Weldon Reference Weldon2002). Women’s interests, on the other hand, are defined primarily as ‘women’s access or protection within each of these policy areas’ (Celis et al. Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Mona Lena Krook2014, 163). We assume that voters expect women legislators to not only address women’s issues, but also advocate for expanded access and rights in policy areas considered highly relevant to women’s lives.

We argue that both women and men should reward women legislators who act in the interests of women. Research suggests that women’s inclusion in legislative bodies enhances men’s and women’s political trust and efficacy by sending signals about the system’s openness to diverse views as well as its institutional legitimacy (Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Jennifer Piscopo2019; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2010; Stauffer Reference Stauffer2021). Voters, regardless of their gender, share the expectation that women legislators will and should act in the interests of women as a group, and doing so ensures the inclusiveness and the legitimacy of legislative bodies (Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Jennifer Piscopo2019). We argue that, while shared party identification is a consistent and reliable predictor of voter approval (Gerber and Green Reference Gerber and Green2000; Giger and Lefkofridi Reference Giger and Lefkofridi2014), the extent to which legislators act in accordance with the issue interests of voters also matters (Ansolabehere and Kuriwaki Reference Ansolabehere and Kuriwaki2022; Kaslovsky and Rogoswki Reference Kaslovsky and Rogoswki2022). This logic leads to our first hypothesis.

Gendered Expectations Prediction: Co-partisan women legislators who support women’s interests will receive more favourable evaluations relative to co-partisan women legislators who vote against women’s interests, and more favourable evaluations relative to co-partisan men who also support women’s interests.

We expect two key patterns as evidence of gendered expectations. First, we expect that women will receive a boost when they vote in a way perceived to match women’s interests relative to when they vote on legislation perceived as being against women’s interests. Second, we expect that women’s rewards for supporting women’s interests will be greater than any boost a man receives for supporting women’s interests.

While we expect women and men in the electorate to reward women legislators who advance women’s interests, we also expect gender differences in which voters punish women for failing to support women’s interests. Past work finds a gender affinity effect between women voters and women legislators (Plutzer and Zipp Reference Plutzer and Zipp1996; Zipp and Plutzer Reference Zipp and Plutzer1985; Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2002), even if women often do not behave as a homogenous group (Conover Reference Conover1988; Cook and Wilcox Reference Cook and Wilcox1991). Underlying this gender affinity effect among women voters is the expectation that women representatives will provide substantive representation for women and advance women’s collective interests through their legislative activity (Swers Reference Swers2005; Thomas Reference Thomas1991). Further, women’s campaign strategies reinforce voters’ gendered expectations. Women candidates often campaign on women’s issues, highlighting their competence in and commitment to the advancement of women’s interests (Dabelko and Herrnson Reference Dabelko and Herrnson1997; Herrnson, Lay, and Stokes Reference Herrnson, Celeste Lay and Stokes2003).

The expectations women constituents hold for women representatives – namely, that they will substantively represent women’s interests – can activate ‘gendered accountability’ (Mechkova and Carlitz Reference Mechkova and Carlitz2021, 4). Feeling empowered by the presence of women legislators, women pay greater attention to women legislators’ policy records and hold these legislators accountable even when those legislators vote against their preferred policy positions (Jones Reference Jones2014). This gendered accountability will also be more likely to manifest when women legislators do not act for women’s interests, failing to live up to the expectations of substantive representation. As such, our second hypothesis posits that women voters will rate women legislators who do not support women’s interests more negatively compared to men voters.

Gendered Sanctions Prediction: Women voters will evaluate co-partisan women legislators more negatively when that legislator does not support women’s interests relative to co-partisan men voters.

Many issues classified as ‘women’s issues’ are issues owned by the Democratic Party (Petrocik, Benoit, and Hansen Reference Petrocik, Benoit and Hansen2003; Wolbrecht Reference Wolbrecht2000). We expect that Democratic voters will be more likely to reward women legislators who vote on women’s issues that advance women’s group interests because these issue positions match partisan expectations. We operationalize advancing women’s interests as taking a position on legislation that actively expands women’s abilities to engage in social, economic, or political activities (Celis et al. Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Mona Lena Krook2014). This definition taps into dynamics of partisan ownership that we think will affect how voters evaluate. On an issue such as abortion, we expect Democratic participants will be more likely to support legislators who support expanding access to abortion. Republican legislators frequently use language about protecting and supporting women even when they vote against legislation designed to remedy gender inequities (Wineinger Reference Wineinger2022; Schreiber Reference Schreiber2008; Deckman Reference Deckman2016; Roberti Reference Roberti2021a, Reference Roberti2021b). Our last hypothesis predicts partisan differences in how voters react to legislators supporting or failing to support women’s interests.

Partisan Differences Prediction: Democratic voters will evaluate co-partisan legislators more positively for supporting women’s interests relative to Republican voters evaluating co-partisan legislators.

We test three predictions. First, our gendered accountability prediction argues that women who support women’s interests should receive more positive ratings than men for meeting this gendered expectation. Second, our gendered sanction prediction argues that women voters will be the most likely voters to hold women accountable for their votes on women’s interests. Third, Democrats should be more likely than Republicans to positively rate women who act in the interest of women. Before testing these three predictions, we first test a key premise of our arguments about the electorate’s gendered expectation that women legislators should and will act in the interests of women. We do so by revealing a plausible source of this gendered expectation – the news media – through an analysis of television news coverage.

Public Narratives about Women’s Representation: A Content Analysis

We have set forth a theory to explain when the public’s expectations of women legislators are gendered, and the effects of these patterns. We do not know where these gendered expectations come from or, in other words, where the public gets the message that women are uniquely suited to advocate for women’s interests. One potential source of information regarding the uniqueness of women as political leaders is the news media. The news is the primary way people learn about politics, and it is likely that the perception that women in politics behave differently than men can be traced to news coverage. Indeed, anecdotal data – such as the Martha MacCullum quote from our introduction – suggest that news coverage commonly underscores the distinctive voice women are thought to bring to political office, and consequently, their unique women legislating.

We argue that the news media will use what we term a women-as-unique frame to characterize women political leaders. This frame comes from gender stereotypes. Gender stereotypes about women’s areas of issue expertise certainly shape voter expectations about the types of issues women will advocate for in office, whether women will act in the interests of women as a group (Schneider Reference Schneider2014; Bauer Reference Bauer2021), and whether women will engage in behaviours that fit feminine stereotypes set as promoting compromise and consensus (Barnes Reference Barnes2016; Volden, Wiseman, and Wittmer Reference Volden, Wiseman and Wittmer2013). These stereotypes affect how journalists report on women political leaders during political campaigns (Meeks Reference Meeks2013; Bauer and Taylor Reference Bauer and Taylor2023; Bauer Reference Bauer2022). We expect these stereotypes will also shape how the news media report on women political leaders both during and beyond a campaign context (Aaldering and van der Pas Reference Aaldering and van der Pas2020).

Gender stereotypes manifest in the use of the women-as-unique frame, which leads to news coverage that highlights women leaders as different, underscores support of women as ‘other’, and emphasizes women’s issues. The ‘women-as-unique’ frame is a useful tool for journalists reporting on politics as it meets the newsworthiness criterion which privileges reporting on ‘unusual’ stories (Galtung and Ruge Reference Galtung and Ruge1965). Hayes and Lawless (Reference Hayes and Lawless2016) argue that women are no longer seen as distinct and novel political actors when they run for office – but the narratives surrounding Hilary Clinton’s presidential campaign in 2016 and the coverage of women as political actors in 2018 and 2020 suggest otherwise (Cassese et al. Reference Cassese, Conroy, Mehta and Nestor2022; Jones Reference Jones2016). For journalists, any deviation from the status quo – a bias in news making – is likely to be seen as novel (Lewis Reference Lewis2001). Novelty frames help journalists report on politics while crafting a narrative that is likely to be of interest to the audience. By using the women-as-unique frame, the news media create and disseminate gender stereotypic news coverage of women, and this coverage offers one explanation for why the public expects that women politicians are well suited to act in the interests of women as a group.

To understand the extent to which news narratives use a women-as-unique frame in political coverage, we conduct a content analysis of news coverage focusing on women candidates. These analyses enable us to check our assumption regarding the presence of gendered expectations, with the added benefit of grounding our theory in the real world. As noted above, we conceptualize the women-as-unique frame as coverage that distinguishes women by either saying explicitly that they are different, describing support for them based on their gender (for example, ‘people are supporting women candidates in droves’), or by highlighting women’s issues. Our operational definition necessitates that coverage include discussion of women leaders as a group. This specification is important for measurement, but it is also substantively important, as we argue that this focus on the collective – one that we never see in the reverse (for example, ‘people are turning out for male candidates’), is one way the media sets a narrative that creates the expectation that women will act for women’s substantive interests. Coverage of an individual woman candidate may use this frame, (for example, ‘Congresswoman Chrissy Houlahan’s election is part of a pink wave’), though not all candidate coverage includes such discussion.

Once narrowed to coverage of women candidates, we additionally capture other dimensions of this coverage: discussion of 1) the public supporting women (for example, ‘people are targeting their campaign donations to women candidates’); 2) women voters supporting women (for example, ‘women are mobilized by the potential for a pink tide’); 3) women candidates as different or unique from candidates who are men (for example, ‘women can reach across the aisle’); and, finally, 4) mention of women’s issues. Each of these elements contributes to positioning women politicians as unique. More details on our operational definitions and coding procedures can be found in Appendix 1, Table A1. Given the exploratory nature of this analysis, we use an expansive definition of women’s issues for coding based on Fox (Reference Fox, Carroll and Fox2006), including issues such as reproductive rights, equal pay, sexual harassment, sexism, caregiving, education, and domestic violence. We developed our codebook based on expert feedback and refined it through an iterative training process that involved two coders. Coders trained for a minimum of three hours; intercoder reliability was calculated with a random sample of 10% of the coverage (n=20) and met the a priori threshold of K=0.7 (Grant, Button, and Snook Reference Grant, Button and Snook2017).

We first pulled the aggregated monthly cable news coverage that aired on CNN, Fox News, and MSNBC that mentions ‘women candidates’ from January 1, 2010, to January 23, 2023, using the Stanford Cable News Analyzer (Hong et al. Reference Hong, Crichton, Zhang, Fu, Ritchie, Barenholtz, Hannel, Yao, Murray, Moriba, Maneesh and Fatahalian2021). We make several choices about this data collection. First, we focus on cable news because these outlets have the incentive and time to discuss candidates more broadly, as in women candidates as a group. Second, we use the phrase ‘women candidates’ because we want to understand how the news covers women candidates as a group, rather than individual women candidates. Moreover, several iterative searches and validity checks illustrate this query performs better than alternatives such as ‘women in politics’. Finally, we use these dates, spanning nearly 157 months, to define our period of interest as they represent the first day of coverage available on the Analyzer and the date of data collection. From this period, we randomly selected twenty months of coverage to analyze, with an additional purposive sample of four additional months that occurred during election years (n=24 months).

The Analyzer uses data provided by the Internet Archive and, based on a keyword hit, pulls text windows up to 3-minute intervals around the query of interest with matching video aligned using an algorithm (less time is excerpted if there is a commercial). This process yields a total of 160 video excerpts, some of which are duplicates. We retain duplicate videos as it is common for cable news outlets to re-air segments and, as such, their inclusion is necessary for understanding the frequency of women-as-unique political coverage. The unit of analysis is transcript excerpts with approximately three minutes of coverage around the search term, ‘women candidates’.

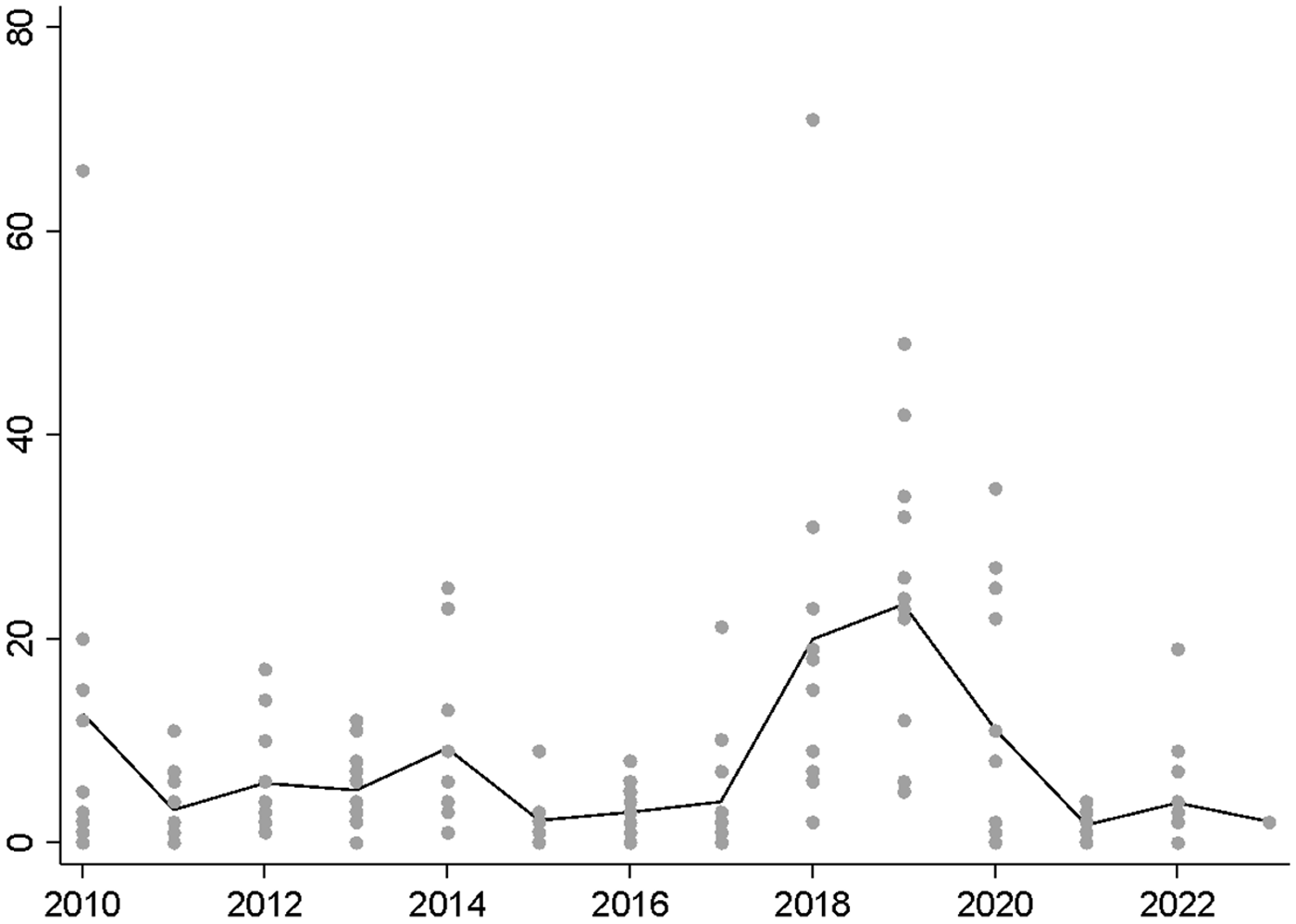

We start with descriptive data of news coverage. Figure 1 shows the average number of seconds of ‘women candidates’ coverage on cable news outlets during our time period by year, aggregated by month. As the figure shows, coverage of women candidates spikes during election years.Footnote 2 Women candidates made up 8.02 seconds of coverage monthly on average (SD=11.41, range from 0–71).

Figure 1. Average duration of ‘Women Candidates’ cable news coverage, by year.

The analysis shows that when the news covers women candidates, they often characterize them as unique (in 10% of coverage), aligning with our expectation that women in politics coverage often uses a women-as-unique frame. This coverage also emphasized stereotypically feminine issues (in 25.63% of coverage) such as abortion and equal pay. As we noted above, frames shape the information journalists include in a story, and it seems that – as we expected – women candidate coverage emphasizes women-as-unique, and discusses women’s issues. Next, we identify which electoral stakeholders are discussed in coverage as being uniquely supportive of women candidates. First, 14.38% of all video excerpts that mention women candidates discuss the public’s support of women, while women voters were discussed in 7.5% of video excerpts.Footnote 3 This initial analysis lends support to a key premise of our argument, that there is a general expectation that women in elected political office will act for and advocate for women. We next turn to track how voters evaluate women candidates who fulfill gendered expectations to uniquely advocate for women as a group in two experimental studies.

Experimental Tests of Gendered Expectations

We use experiments because this approach has the high level of internal validity necessary to isolate the causal mechanisms behind the evaluations facing women legislators when they vote on women’s issues (Mutz Reference Mutz2011). It would be ideal to have polling data from voters before and after legislators cast votes on women’s issue bills to see how evaluations change. Such data is not possible to obtain without losing internal validity (Morton and Williams Reference Morton and Williams2010). Even if such data were easily obtained, there would be no way for us to control for other characteristics of legislators, such as the type of district they represent, their past records on women’s issues, or the extent to which a legislator is credit-claiming on a specific issue. Given the constraints of obtaining observational public opinion data, experiments are the best method for testing the dynamics of gendered accountability.

Our two studies use similar designs. We describe the treatments and our samples together and then present our results. Our first study uses the issue of abortion and took place in spring 2021 and the second study uses equal pay and took part in fall 2021. Both studies use a 2x2 design that manipulates legislator gender (man or woman) and varies the position a legislator takes on abortion and equal pay. We embedded the treatment in a short vignette.

In the abortion study, we used state legislators as the representatives supporting or opposing abortion access. Abortion is a very partisan issue at the federal level. At the state level, there is more partisan and ideological diversity in the legislators who oppose or support abortion, and this choice increases the ecological validity of our treatment. We matched participants into conditions to read about a co-partisan legislator: Democratic participants read about a Democratic woman or a Democratic man and Republican participants read about a Republican woman or a Republican man. We asked those who identified as independents to indicate a party they leaned more closely toward and used those responses to match participants into partisan conditions.Footnote 4 Our full abortion study vignette is below with manipulations in italics, with the design and sample sizes described in Table 1. We included text that said the bill was designed to ‘protect women’ and we also indicated that women’s groups supported the legislation. We kept the language about protecting women in the condition where the abortion bill limited access to the procedure to reflect how legislators of both political parties discuss this issue (Roberti Reference Roberti2021a, Reference Roberti2021b).

On Monday, state legislators passed a bill that would limit/expand access to abortion. Democratic/Republican legislator Carol/Chris Hartley, a key sponsor of the bill, emphasized that this measure will protect women and children.

The bill received support from liberal/conservative women’s groups who said it ‘will promote women’s health and ability to access abortion care/save unborn children.’ Liberal/Conservative women’s groups oppose this measure criticizing that it will restrict women’s rights and ability to access abortion care.

Democratic/Republican state legislator Carol/Chris Hartley sponsored the bill and played a critical role in ensuring its passage. State legislator Carol/Chris Hartley will hold a press conference later today to discuss the importance of the bill.

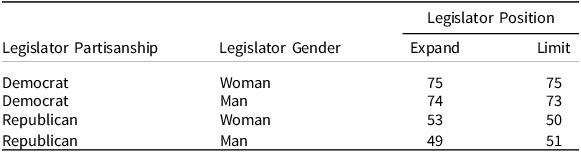

Table 1. Abortion Study Design, N=500

For the equal pay study, we used Congress as the legislative body, and we provided instructions indicating that the legislator belonged to the same party as the participant taking the study but we did not explicitly cue partisanship (Bauer, Kalmoe, and Russell Reference Bauer, Kalmoe and Russell2022). We set up our conditions to have a legislator support or oppose an equal pay bill. The treatment characterizes the woman or man as being responsible for ensuring the bill’s passage or failure either through sponsorship or being an opponent of the bill. Our language in the anti-equal pay condition may soften the extent to which the legislator was directly responsible for the bill’s passage, which offers a more conservative estimate of any sanctions the legislator may face. The equal pay study design details and sample sizes are in Table 2, with the vignette listed below and manipulations in italics:

On Monday, Congress passed/failed to pass a bill that would mandate equal pay between women and men. Senator Carol/Chris Hartley, a key sponsor/opponent of the bill, emphasized that this measure will/will not protect women from discrimination.

The bill received support from women’s groups who said, ‘it will promote women’s economic prosperity and will be good for families.’ Business groups opposed this measure criticizing that it will be bad for the economy.

Senator Carol/Chris sponsored/opposed the bill and played a critical role in ensuring its passage/failure. Senator Carol/Chris will hold a press conference later today to discuss the importance of the bill.

Table 2. Equal Pay Study Design, N=1000

We selected abortion and equal pay as our issues because we expect to see voters hold women legislators to particularly high expectations regarding their behaviour advancing women’s interests. The lack of abortion access can adversely affect women and people who can or do become pregnant by limiting the ability of these individuals to seek health care before and during a pregnancy (Kreitzer et al. Reference Kreitzer, Smith, Kane and Saunders2021; Manian Reference Manian2014). Equal pay is also an issue where women are more likely to suffer economic harm relative to cis-gender white men (Mandel and Semyonov Reference Mandel and Semyonov2014). Both issues are owned by the Democratic Party (Petrocik, Benoit, and Hansen Reference Petrocik, Benoit and Hansen2003). However, Republican and right-wing politicians in many countries frequently frame abortion restrictions as acting on behalf of women’s interests (O’Brien Reference O’Brien2018). While expanding abortion access is a position that aligns more with Democrats compared to Republicans, there are legislators of both parties at the state level who hold positions on abortion that do not align with their party. For example, one of the trigger laws passed in Louisiana was a bill sponsored by a Black Democratic woman in the state legislature. At the same time, three Republican women in the South Carolina legislature stood firm against abortion restrictions in their states.Footnote 5

We used two different samples for our experiments. The abortion study used Lucid, an online platform that recruits and maintains a sample of adult participants to take part in online studies. Lucid uses an adult convenience sample. We conducted this study in the Spring of 2021 before the Supreme Court issued the Dobbs decision, which states that pregnant people have no federal constitutional right to seek an abortion. This timing is important as any negative effects we see are likely to be conservative estimates given that public opinion moved sharply in favour of abortion rights post-Dobbs. Footnote 6 The equal pay study used the 2021 Cooperative Election Study, which recruits samples designed to resemble the US population. The CES was administered by YouGov in the fall of 2021 and is also an online adult sample. Table A2 includes the full demographic characteristics of our two samples, and we compare these characteristics to the 2020 Census.

Our sample size in both studies gives us enough statistical power to detect the main effects across conditions for our gendered expectations prediction. In the abortion study, we have approximately 120 people total in each condition combining Democrats and Republicans, and in the equal pay study, we have approximately 250 people in each condition. For the abortion study, our statistical power is reduced for testing our gendered sanction and partisan predictions. When we break our samples in the abortion study down by gender and party, we have 50 to 60 participants in each group. A power analysis suggests that this level of statistical power should be sufficient to detect group differences, but it should be noted that this is the bare minimum number of participants we need. The equal pay study has about 125 participants in each condition when we break our sample down by gender and party, and this is a large enough sample size to detect group differences. We include a breakdown of our sample by party and gender in Appendix 1, Table A3.

We use two outcome questions: favourability and vote support. Participants rated favourability on a 0 to 100 scale with higher values indicating more positive evaluations. Our vote support question asks how likely a participant was to support the legislator in the next election. This question can overestimate support for a legislator’s candidacy in the context of a study about gender due to social desirability biases (Krupnikov, Piston, and Bauer Reference Krupnikov, Piston and Bauer2016). We structured the question in a way that limits the potential for social desirability biases by excluding a ‘neither’ option in the response categories, which included ‘very likely’, ‘somewhat likely’, ‘somewhat unlikely’, and ‘very unlikely’ as the outcomes. We include our full question wordings with response options in Appendix 4. We scaled the outcomes to range from 0 to 1.

Do Voters Hold Women Accountable for Their Votes on Women’s Issues?

Tests of the Gendered Expectations Prediction

Our first prediction argues that women legislators will receive more favourable evaluations when they support women’s interests relative to women who do not vote in a way that advances women’s group interests. We also predict that women who support women’s interests will receive more favourable evaluations relative to men who also support women’s interests. First, we use two-tailed t-tests to compare across the two conditions in each study for women and then separately for men (for example, comparing evaluations of the woman legislator when she votes to expand abortion to the woman legislator when she votes to limit abortion). Second, we compare across candidate gender (for example, woman in the expand abortion access condition vs. the man in the expand abortion access condition). We expect that the woman who votes to expand abortion access and the woman who votes in favour of equal pay will receive a more favourable evaluation than the man in comparable conditions.

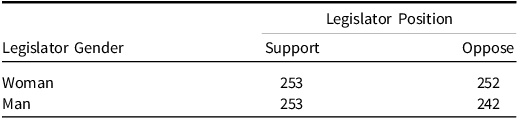

We start with favourability (see Figure 2). In the abortion study,Footnote 7 we find that a woman gets more support when she votes to expand abortion access relative to when she limits abortion access: her rating improves by 0.0767 points (SE=0.040), or 7.67 percentage points, p = 0.0596 (left side of Figure 2). There are no differences in the evaluations of men who expand or limit abortion access, p = 0.6550. We expected, following our gendered expectations prediction, that the woman would receive a larger reward than the man, but we found null effects, p = 0.6089.

Figure 2. Evaluations of legislator favourability.

Note: 95% confidence intervals included.

The right side of Figure 2 shows the results for equal pay. The pro-equal pay woman has a higher favourability rating relative to the anti-equal pay woman by 0.084 (SE = 0.030) points or 8.4 percentage points, p = 0.0057. This mirrors the abortion study. The pro-equal pay man also receives a boost over the anti-equal pay man of 0.109 (SE = 0.030) points or 10.9 percentage points, p = 0.0003. This differs from the abortion study where there were no differences for the man across the two conditions. The differences in the pro-equal pay conditions across legislator genders are not statistically distinguishable from one another, p = 0.9462, again reflecting our abortion study. Women and men who support equal pay receive similar ratings. We also find no differences in the ratings across gender in the anti-equal pay conditions, p = 0.3959. Across our two studies, the lack of gender differences for legislators who support abortion and equal pay suggests that voters may not be more likely to reward women who make good on gendered expectations about representation.

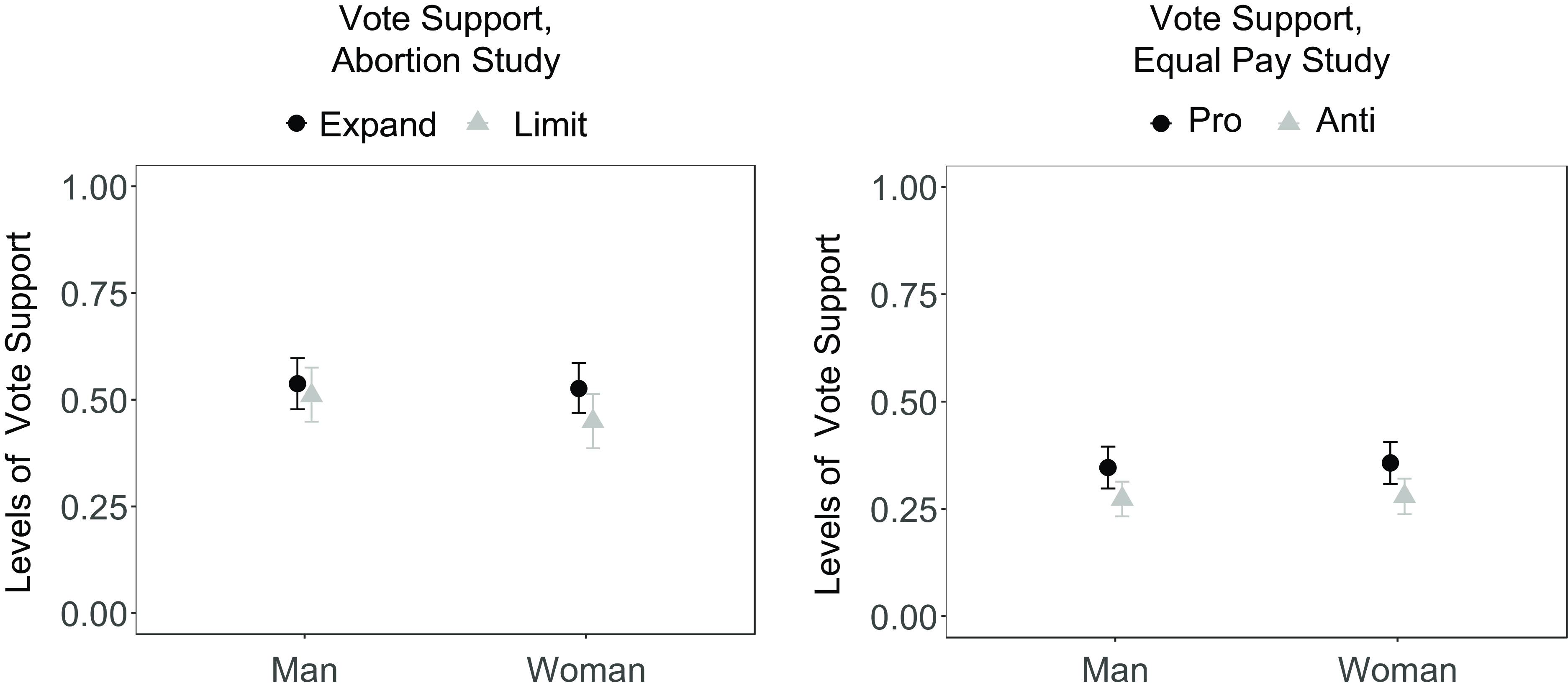

Figure 3 displays ratings on vote support. The woman who votes to expand abortion access receives more electoral support at a level of about 0.078 (SE = 0.348), or 7.8 percentage points, p = 0.0749, compared to the woman who votes to limit abortion access. We find no differences in the conditions to expand and limit abortion access for the man on vote support, p = 0.5619. The positive rating for the pro-abortion woman is comparable to the rating for the pro-abortion man, p = 0.8009. The woman does not receive a more favourable rating than the man, and this does not support our prediction. The ratings for the woman and man in the limit abortion access condition are also not statistically different from one another, p = 0.8009.

Figure 3. Candidate vote support.

Note: 95% confidence intervals included.

In the equal pay study, we find that both the pro-equal pay woman and pro-equal pay man receive more support relative to their anti-equal pay counterparts (right side of Figure 3). The pro-equal pay woman receives a rating of 0.0780 (SE = 0.033), or 7.8 percentage points, higher than the anti-equal pay woman, p = 0.0179. There is a similarly sized effect for the pro-equal pay man whose vote support is 0.073 (SE = 0.032), 7.3 percentage points higher than in the anti-equal pay conditions, p = 0.0239. Comparing the pro-equal pay woman and the pro-equal pay man shows no significant differences in their levels of support, p = 0.7572. We find no differences across gender in the anti-equal pay conditions, p = 0.8382. Across our two studies and two outcome variables, we find no support for our gendered expectations prediction.

Tests of the Gendered Sanction Prediction

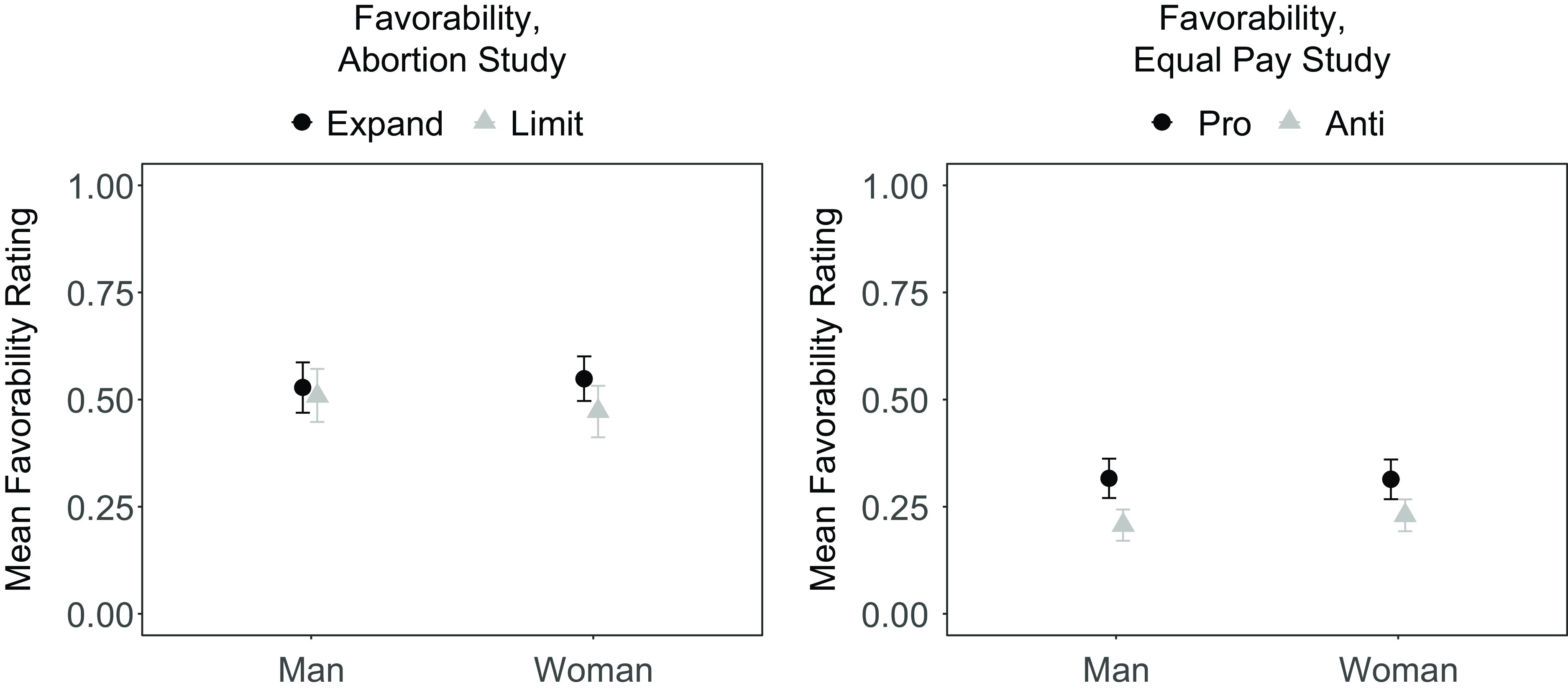

Our second prediction argues that women voters, compared to men voters, will levy a larger punishment against women legislators when women legislators do not support women’s interests. We again conduct our analyses in two sets of comparisons. First, we use two-tailed t-tests to compare women and men respondents within each condition. Second, we conduct comparisons within participant gender across conditions, and we expect that women voters will rate the woman who votes to expand abortion access and in favour of pro-equal pay higher than similarly situated men. We display these results in Figure 4.

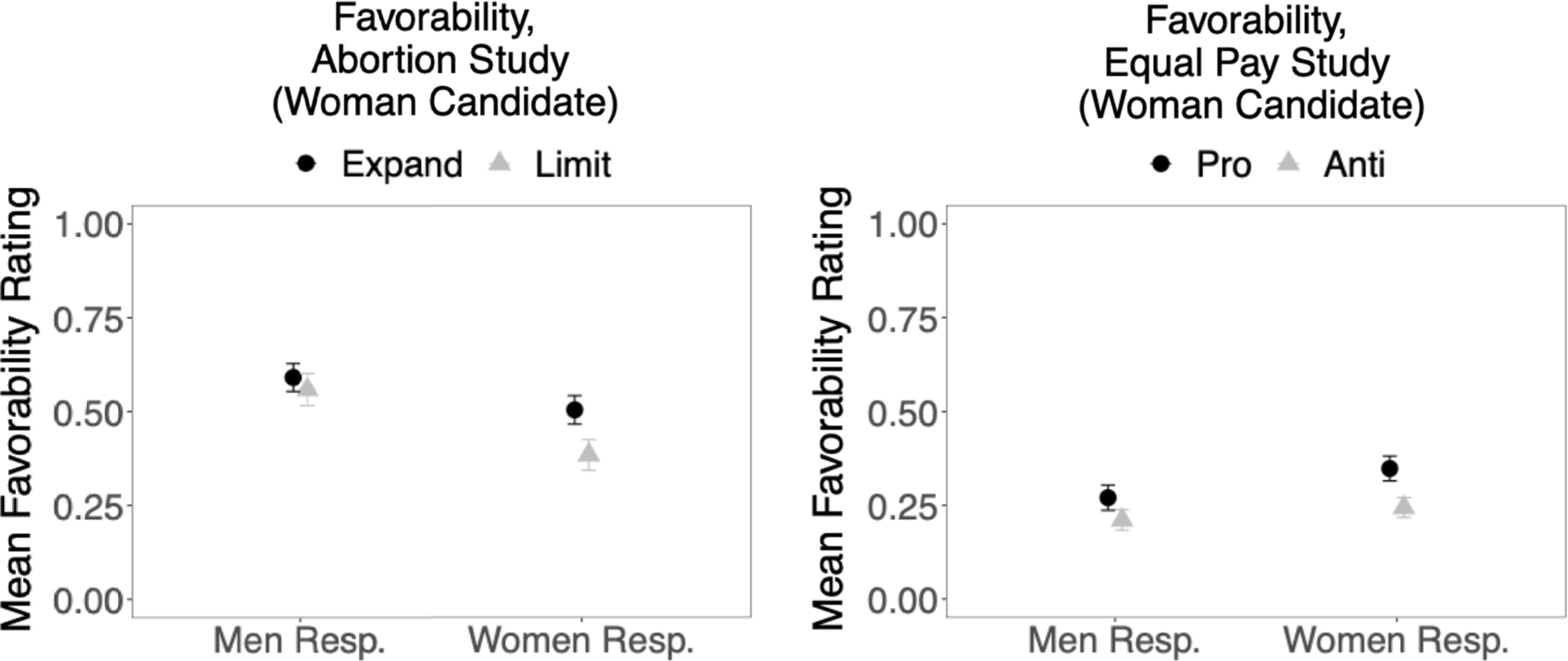

Figure 4. Evaluation of legislative favourability across participant gender.

Note: 95% confidence intervals included.

Women participants rate the anti-abortion woman 0.121 (SE = 0.056), or 12.1 percentage points less favourably than the pro-abortion woman, p = 0.0317. By contrast, men participants do not rate the anti-abortion woman less favourably than the pro-abortion woman, p = 0.5716. Women participants rate the anti-abortion woman 0.1746 (SE = 0.0592), or 17.46 percentage points less favourably relative to men participants in the study, p = 0.0038.

At the same time, we find that women participants rated the anti-abortion man 0.2407 (SE = 0.0596), or 24.07 percentage points less positively than men participants. We expect women participants to rate the anti-abortion woman more negatively than the anti-abortion man based on gendered expectations but we find no differences, p = 0.8991. These findings suggest that women voters negatively evaluate both women and men legislators who vote against abortion more than men voters.

In our equal pay study (Figure 4, right panel), we find no differences between women and men participants in the negative ratings of women legislators, p=0.3910, and men legislators, p=0.2183, who voted against equal pay legislation. This pattern differs from the abortion study where we found that women participants rated the woman and man more negatively when they voted to limit abortion access relative to men participants. We also find no differences in how women participants evaluated the anti-equal pay woman relative to the anti-equal pay man, p = 0.1165.

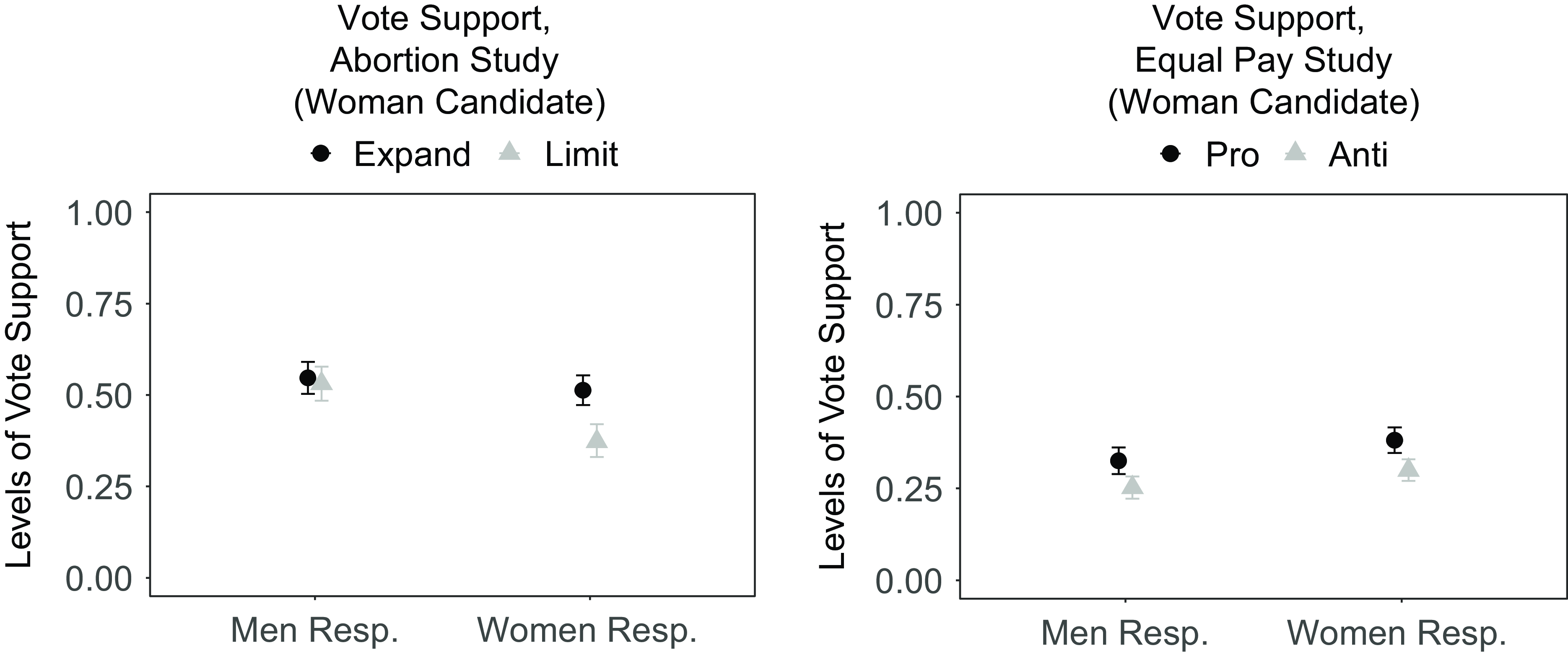

The left panel of Figure 5 shows our findings on vote support, In the abortion study (left panel), our findings match those on favourability. We find that women participants rate the woman legislator who votes to limit abortion access more negatively than men participants, p = 0.0167. Women participants also rate the man in the limit abortion access condition more negatively than men, p = 0.0002. We compared differences across legislator gender within the condition to limit abortion access among women participants and found no differences, p = 0.6872. Women compared to men are more likely to sanction both women and men who vote to restrict access to abortion.

Figure 5. Candidate Vote Support across Participant Gender.

Note: 95% confidence intervals included.

The right panel of Figure 5 shows the results of vote support for the equal pay study. There are no differences in how women and men participants rate the anti-equal pay woman, p = 0.2662, and the anti-equal pay man, p = 0.1360. We also find no differences in how women participants rated the anti-equal pay woman relative to the anti-equal pay man, p = 0.1821. These findings differ from the abortion study, where women participants responded much more negatively to both the women and men who voted to limit abortion access relative to men participating in the study. In the equal pay study, these differences evaporate.

Our abortion study supports the gendered sanction hypothesis, but this pattern is not replicated in our equal pay study. What explains this difference? One potential explanation is that women may perceive abortion rights as more directly relevant to their lives than equal pay. Thus, women may hold women representatives more accountable than men for their positions on abortion, but this gendered difference weakens when holding them accountable for their positions on other issues like equal pay.

Tests of the Partisan Differences Prediction

Finally, we test the partisan differences prediction. We display the full means and comparisons for each condition across partisanship in our appendix (Appendix 3, Table A6, and Table A10). We summarize key patterns here. We find that Democratic participants evaluate the Democratic woman more positively when she supports access to abortion, but Republican participants rate the Republican woman negatively when she supports access to abortion. Instead, Republican participants rate the Republican woman, and man, higher in the condition where they limit access to abortion. We only find these significant effects in the abortion study and the results across our outcome variables are largely insignificant in the equal pay study.Footnote 8

Results Summary

Our studies uncovered several key results. First, we find that women and men legislators who support women’s interests receive comparable ratings when they act in women’s interests – this suggests no support for our gendered expectations prediction. Second, we find that women participants rate women legislators more negatively than men participants when they vote against women’s perceived interests, but women voters also punish men politicians. This does not support the gendered sanction prediction. Third, our partisan differences prediction finds that the positive ratings that women receive for supporting women’s interests are largely isolated to Democratic voters.

Discussion and Implications

We show that voters do not view women legislators as uniquely responsible for delivering women’s substantive representation. Voters view representing women’s interests as a responsibility shared by all legislators, regardless of their gender. We defined and operationalized women’s interests as those positions that disproportionately affect women, relative to men, as a group. Our findings make a crucial contribution to the literature on how voters employ gendered evaluations. While previous studies find little evidence of gender bias in candidate evaluations (Hargrave and Smith Reference Hargrave and Smith2024; Hayes and Lawless Reference Hayes and Lawless2016; McLaughlin Reference McLaughlin2023; Teele, Kalla, and Rosenbluth Reference Teele, Kalla and Rosenbluth2018; Schwarz and Coppock Reference Schwarz and Coppock2020), other work shows that voters still hold gendered expectations regarding policy representation or constituency services (Butler, Naurin, and Öhberg Reference Butler, Naurin and Öhberg2022; Kaslovsky and Rogoswki Reference Kaslovsky and Rogoswki2022). Our findings show that voters expect women legislators to represent women’s interests and hold them accountable when they fail to do so, but not necessarily any more than they do for men.

The null findings for our gendered expectations prediction may be due to ceiling effects. Our two studies included questions about opinions on abortion and equal pay. We find that the majority of participants in both studies support these issues: 90% of participants support some level of access to abortion, though participants were almost evenly split between supporting all legal access to abortion and supporting some legal access to abortion, and 89% support equal pay laws. The broad support for these issues coupled with our findings suggests that participants care about legislators’ support of these women’s interests issues rather than caring about who supports these issues.

Our research has broad implications for the social, political, and economic status of women, especially at the state level where women’s issues, such as abortion, dominate policy making. State legislatures are increasingly making decisions that have important ramifications on the health of women and children including but not limited to paid family leave, women’s deaths by gun violence, equal pay laws, and abortion access (Neil et al. Reference Neil, Bhatia, Riano, de Faria, Catapano-Friedman, Ravven, Weissman, Nzodom, Alexander, Budde and Mangurian2020; Coombs et al. Reference Coombs, Theobald, Allison, Ortiz, Lim, Perrotte, Smith and Winston2022; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Gunderson, Lane and Bauer2023). Our findings suggest that voters care about legislators’ policy positions, and voters especially care about supporting women’s equity interests. Yet, women who fail to support equity issues may face harsh sanctions from women voters. A next step for future research is to test how voters respond to legislators who act in women’s interests or frame their behaviour as women’s interests, on issues that are not strictly women’s issues.

What do these findings mean for other marginalized groups? Where there is public consensus, legislators may have incentives to involve and advocate for marginalized groups like the LGBTQ+ community, immigrants, and minorities (Bratton, Haynie, and Reingold Reference Bratton, Haynie and Reingold2007; Fraga et al. Reference Fraga, Lopez, Martinez-Ebers and Ricardo Ramirez2006; Brown Reference Brown2014; Bergersen, Klar, and Schmitt Reference Bergersen, Klar and Schmitt2018). Our results suggest that legislators who support these groups will reap the benefits even if they are not themselves members of that group, particularly among Democrats if the equity lens functions in a manner like how it does for women’s issues. Substantive representation does not need descriptive representation of a group to occur.

These findings have critical consequences for understanding the links between descriptive and substantive representation and the collective representation of women’s political interests. Voters simply want their policy views to be represented, but they do not necessarily care who represents them – a man or a woman. However, our findings must be considered in context with other gender and politics work showing that women are more effective in office than men (Anzia and Berry Reference Anzia and Berry2011) and pass more legislation often through collaborative networks (Volden, Wiseman, and Wittmer Reference Volden, Wiseman and Wittmer2013), along with the increased feelings of political efficacy and trust (Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Jennifer Piscopo2019). It is good news that voters will reward men and women for pursuing a policy that promotes women’s equity. However, if those types of bills are more likely to be introduced by women and to advance through the political process, then the presence of women in legislatures remains a critical component of advancing women’s issues.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123424001017

Data availability statement

Replication data are available on the Harvard Dataverse website at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/XDEKBT.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kate Bratton for providing partial funding for this project.

Financial support

This research was supposed through funds from the LSU Political Science department, the Louisiana Board of Regents grant number LEQSF(2020-23)-RD-A-34, and the Remal Das and Lachmi Devi Bhatia Memorial Professorship.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests.