Introduction

Gonorrhea is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae [Reference Unemo1]. Infection usually presents as urethritis in males and cervicitis in females, but extragenital infections of the pharynx and rectum are also common. If infection is not detected and appropriately treated, N. gonorrhoeae may progress and cause severe complications such as pelvic inflammatory disease, chronic pelvic pain, infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and life-threatening disseminated gonococcal infections [Reference Unemo1, Reference Sawatzky2]. Additionally, N. gonorrhoeae infection increases the risk of HIV acquisition and transmission [Reference Pathela3–Reference Sadiq5].

Globally in 2020, an estimated 82.4 million new gonorrhea cases were diagnosed among people aged 14-49 years [6]. In Canada, gonorrhea is currently the second-most reported STI, with the highest rates per 100 000 people reported in Alberta, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan [7].

The distribution of gonorrhea cases varies by sex, sexual orientation, socioeconomic conditions, ethnicity, and access to sex education and health services [Reference Unemo1]. Worldwide, certain groups such as ethnic minorities, gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (gbMSM), and transgender persons are overrepresented in the higher gonorrhea incidence rates [Reference Kirkcaldy8]. In addition, these groups might also face barriers in access to health care, which may increase their risk of severe complications.

Effective antimicrobial treatment is key to control the infection, but antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in N. gonorrhoeae is a concerning public health challenge [Reference Unemo and Shafer9]. Although some N. gonorrhoeae strains remain susceptible, resistance has been reported to every antimicrobial recommended for its treatment over the past 80 to 90 years. During the 2010s, combination therapy of a cephalosporin and azithromycin was introduced as the recommended treatment for gonorrhea in Canada and globally to address frequent C. trachomatis co-infections and to hinder the emergence of N. gonorrhoeae strains with decreased susceptibility to cephalosporins, considered last-resort antimicrobials [10, Reference Workowski and Berman11].

In recent years, however, treatment failures with combination therapy have been reported worldwide due to the emergence of multidrug-resistant N. gonorrhoeae (MDR-GC) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR-GC) isolates [Reference Fifer12–14]. MDR-GC is defined as an isolate with either decreased susceptibility to cephalosporins or resistance to azithromycin plus resistance to at least two other antimicrobials (penicillin, tetracycline, erythromycin, ciprofloxacin) [Reference Martin15]. XDR-GC refers to an isolate with decreased susceptibility to cephalosporins and resistance to azithromycin plus resistance to at least two more antimicrobials [Reference Martin15]. Treatment failures due to AMR compromise control of the infection and increase the prevalence of complications [Reference Tapsall16].

Although gonorrhea has been a nationally notifiable disease in Canada since 1924, monitoring of antimicrobial-resistant gonorrhea did not start until 1985 with the Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Program – Canada (GASP-Canada) [17, Reference Sawatzky18]. GASP-Canada is a passive surveillance system that performs antimicrobial susceptibility testing in all submitted isolates [Reference Sawatzky18]. Submission of isolates from provinces and territories is voluntary and not standardized nationwide [Reference Thorington19]. Moreover, GASP-Canada does not collect comprehensive epidemiological information, limiting the ability to understand AMR trends within particular subpopulations according to their sexual orientation and additional risk factors [17]. To fill these gaps, the Enhanced Surveillance of Antimicrobial-Resistant Gonorrhea (ESAG) program was launched in 2013 to link epidemiological and clinical data to improve the understanding of AMR trends in Canada and identify risk factors for AMR in gonorrhea in the population [17, 20]. Understanding resistance trends is key to control gonorrhea infection by modifying treatment guidelines [21]. According to World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations, if more than 5% of isolates are resistant to a recommended antimicrobial or if unexpected AMR increases are observed in key populations, steps should be taken to review and modify treatment guidelines [21]. Considering that the Prairie provinces have the highest rates of gonorrhea in Canada, our goal was to identify the trends of gonorrhea infection in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba compared to Canada from 1980 to 2022, and to assess how resistance patterns have evolved.

Methods

Study design and settings

We conducted an ecological study of all annual gonorrhea diagnoses from publicly available STI reports from Canada and the provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba from 1980 to 2022. These three provinces are geographically contiguous and collectively represent the Canadian Prairies region [22]. In 2021, the population of Canada was 36 991 981, with 4 262 635 people living in Alberta, 1 132 505 in Saskatchewan, and 1 342 153 in Manitoba [23]. In Canada and Alberta, more than 80% of the population lives in urban areas [24], 66% in Saskatchewan, and 72% in Manitoba. Regarding income, according to the Census Family Low Income Measure [25], 15.5% of Canadians, 13.6% in Alberta, 18.4% in Saskatchewan, and 18.8% in Manitoba are considered to be in low income.

Data sources

Seven co-authors conducted a systematic search of all publicly available federal and provincial surveillance reports that provided the number of gonorrhea cases for a given year on the websites of the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) and that of the governments of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba between 1980 and 2022. To supplement government sources, we also performed a systematic search in Google Scholar using the keywords ‘Gonorrhea’ and ‘Canada’, ‘Alberta’, ‘Manitoba’, or ‘Saskatchewan’. If multiple reports covered the same year, we selected those with more detailed sociodemographic information on the cases. We collected data on AMR trends for gonorrhea isolates from PHAC reports, including the Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System and ESAG. Additional reports referred by colleagues were reviewed and data extracted. Detailed sources for the included reports can be found in Supplementary Table S1, and all data extracted can be found in Supplementary Tables S2–S6. All reports included were downloaded, and all extracted data are also available for download at https://osf.io/qwfgj/files/42dkc.

When gonorrhea rates per 100 000 population were not provided in reports, they were calculated using the number of cases reported and the overall and by sex and age group population estimates for Canada, Alberta, Manitoba, or Saskatchewan as reported by Statistics Canada [26] for the corresponding year.

Variables collected

We extracted the following information from all reports: Number of gonorrhea cases per year; rate of cases per 100 000 population; distribution of cases by sex, age, ethnicity, sexual orientation; injection drug use; and other self-reported risk factors. Data on the proportion of cases with a culture available, proportion of clinical isolates resistant or with decreased susceptibility to tested antibiotics, MDR-GC, and XDR-GC were also collected.

Diagnostic methods over time

Diagnosis of gonococcal infections before 1997 in Canada relied primarily on Gram stain observation of infected fluids or selective bacterial culture [Reference Barbee and Dombrowski27]. In 1997, nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) was introduced in Canada and became the preferred diagnostic method over time [28].

Interpretation criteria for minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) to guide therapy evolved during the studied period. From 2005 to 2008, a clinical isolate was considered to exhibit decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone (CRO-DS) or cefixime (CFM-DS) if the MIC was greater than 0.25 mg/L [29]. In 2011, MIC breakpoints in Canada were updated to greater than or equal to 0.125 mg/L for CRO-DS, and greater than or equal to 0.25 mg/L for CFM-DS, following the WHO’s global action plan to control the spread and impact of AMR in Neisseria gonorrhoeae [21, 30]. Azithromycin MIC interpretations did not change from 2005 through to 2019 [29, 31].

Antibiotic therapy changes over time

The preferred treatment for gonococcal cases has evolved in response to emerging AMR patterns. In the 1940s, penicillin and its derivatives were used to treat gonorrhea in Canada [Reference MacDougall32]. However, in the early 1990s, recommendations changed to third-generation cephalosporins and ciprofloxacin due to rising resistance to penicillin [Reference Squires and Doherty33]. The Canadian guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections from 1998 and 2006 recommended single-dose regimens of cefixime 400 mg orally, ciprofloxacin 500 mg orally, or ceftriaxone 125 mg intramuscularly for uncomplicated urethral, endocervical, rectal, or pharyngeal infection [34, 35]. In 2011, PHAC removed ciprofloxacin from its recommendations due to rising quinolone resistance, and increased cephalosporin doses to 800 mg for cefixime and 250 mg for ceftriaxone [36]. In 2013, treatment recommendations were updated to dual therapy, consisting of a cephalosporin plus 1g of azithromycin orally, which remained in effect through 2022 [10].

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report the gonorrhea rates per 100 000 people, and the percentage of diagnoses by sex in Canada, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba from 1980 to 2022. The percentage of cases by age group for females and males, and by ethnicity was available for Manitoba and Alberta in some years. We performed an age–cohort–period analysis for Canada, Alberta, and Manitoba using a negative binomial regression model with a log link to identify the effects of age, cohort, and period on the incidence rates of gonorrhea. We did not include Saskatchewan in this analysis because gonorrhea cases by age group for females and males were not available.

We also depicted the percentage of cases with available cultures, the percentage of isolates exhibiting resistance or decreased susceptibility to tested antibiotics, and the Canadian percentage of cultured clinical isolates considered MDR-GC or XDR-GC. To calculate the percentage of clinical isolates exhibiting resistance or decreased susceptibility to tested antibiotics in each province, we divided the number of such isolates by the total number of cultured isolates for that province as reported to the National Microbiology Laboratory. All figures were generated using RStudio (Version 2024.12.0+467).

Ethics statement

This research uses publicly available aggregated data, and therefore ethics board approval was not required. This work was conducted in accordance with the Tri-Council policy statement-ethical conduct of research involving humans [37].

Results

Gonorrhea rates in Canada, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba

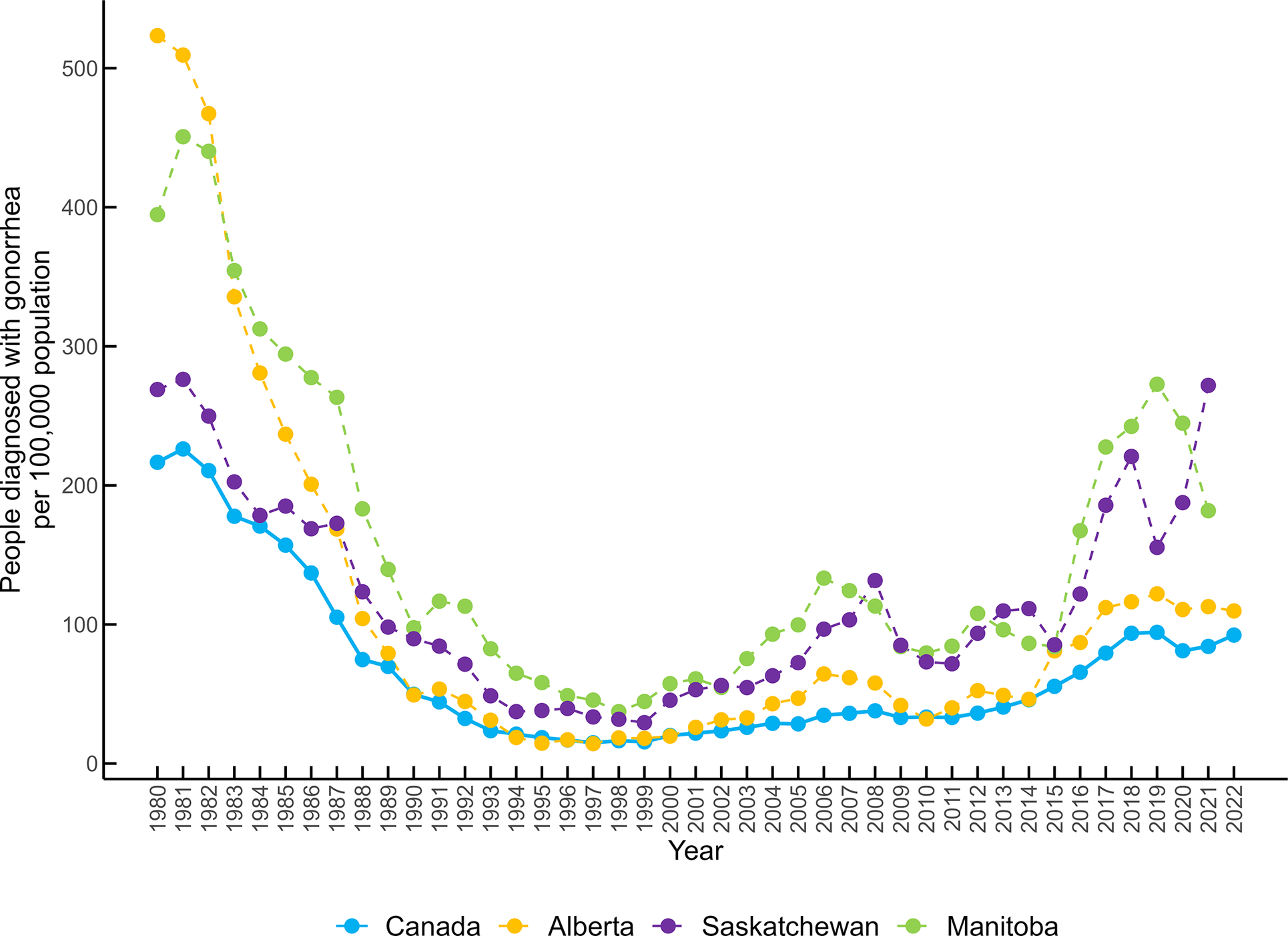

Gonorrhea rates in Canada decreased from 1980 until the late 1990s. Canada and Alberta reported their lowest rate in 1997 (14.9 diagnoses/100 000 population and 14.3/100 000 respectively), while Manitoba had its lowest rate in 1998 (37.3/100 000), and Saskatchewan in 1999 (29.4/100 000). Since then, rates have increased four- to five-fold, to the highest rates in the past 30 years between 2019 and 2022 (Canada: 94.31/100 000, Alberta: 122.0/100 000, Manitoba: 272.7/100 000, and Saskatchewan: 271.9/100 000) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. People newly diagnosed with gonorrhea/100 000 population in Canada, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba from 1980 to 2022.

Gonorrhea rates by sex, age, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and associated risk factors

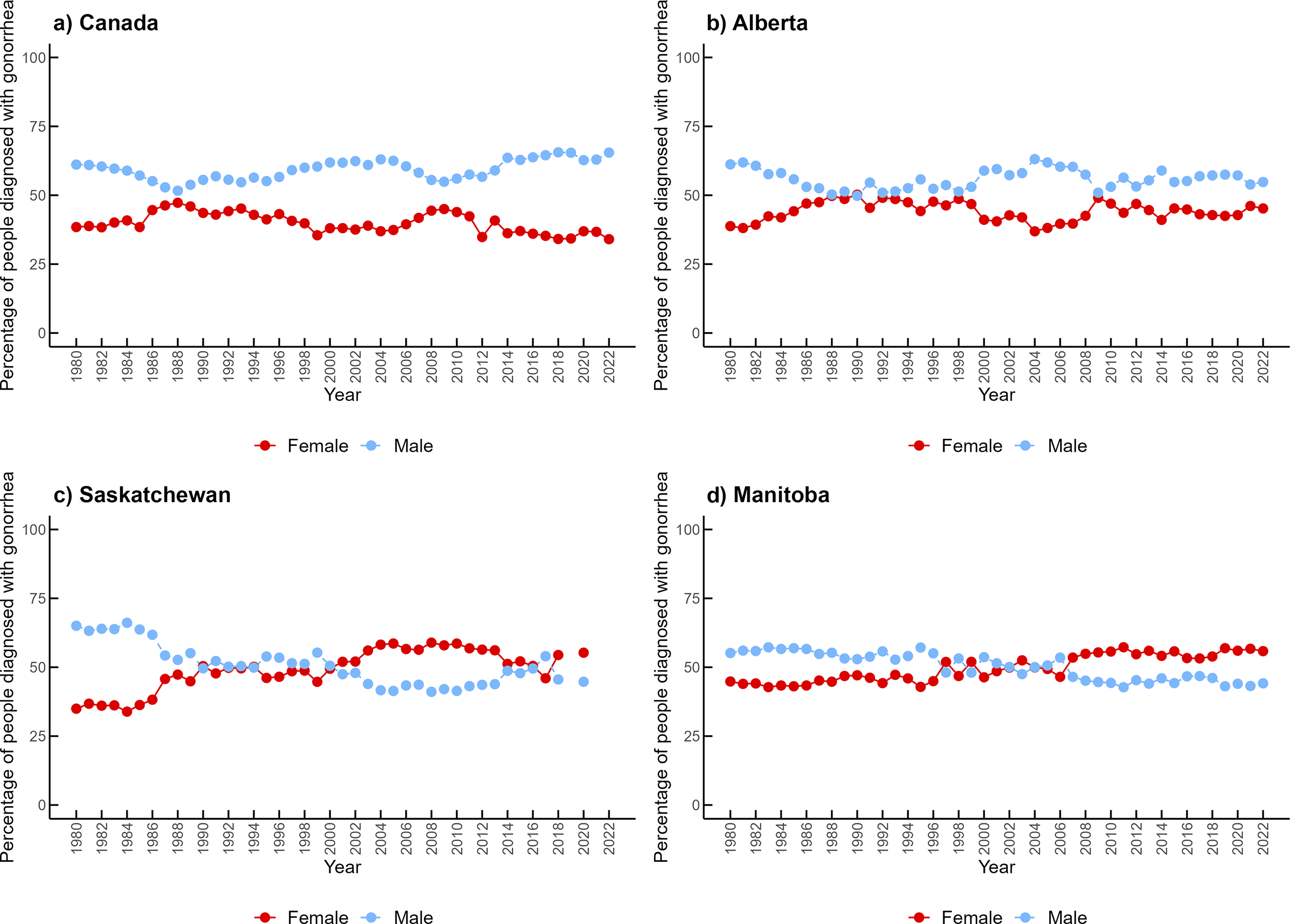

In Canada and Alberta, males accounted for approximately 60% of cases over time (1.50 male-to-female ratio in Canada and 1.28 in Alberta). However, Alberta had periods of similar distribution of cases between females and males between 1987 and 1994, as well as in 2009 (Figure 2). In contrast, Manitoba and Saskatchewan have reported a higher proportion of infection among females (approximately 55%) since the early 2000s (0.89 male-to-female ratio in Manitoba and 0.85 in Saskatchewan). The male-to-female ratio of reported gonorrhea cases over the period studied is available in Supplementary Figure S1.

Figure 2. Percentage of gonorrhea cases by females and males in (a) Canada, (b) Alberta, (c) Saskatchewan, and (d) Manitoba from 1980 to 2022.

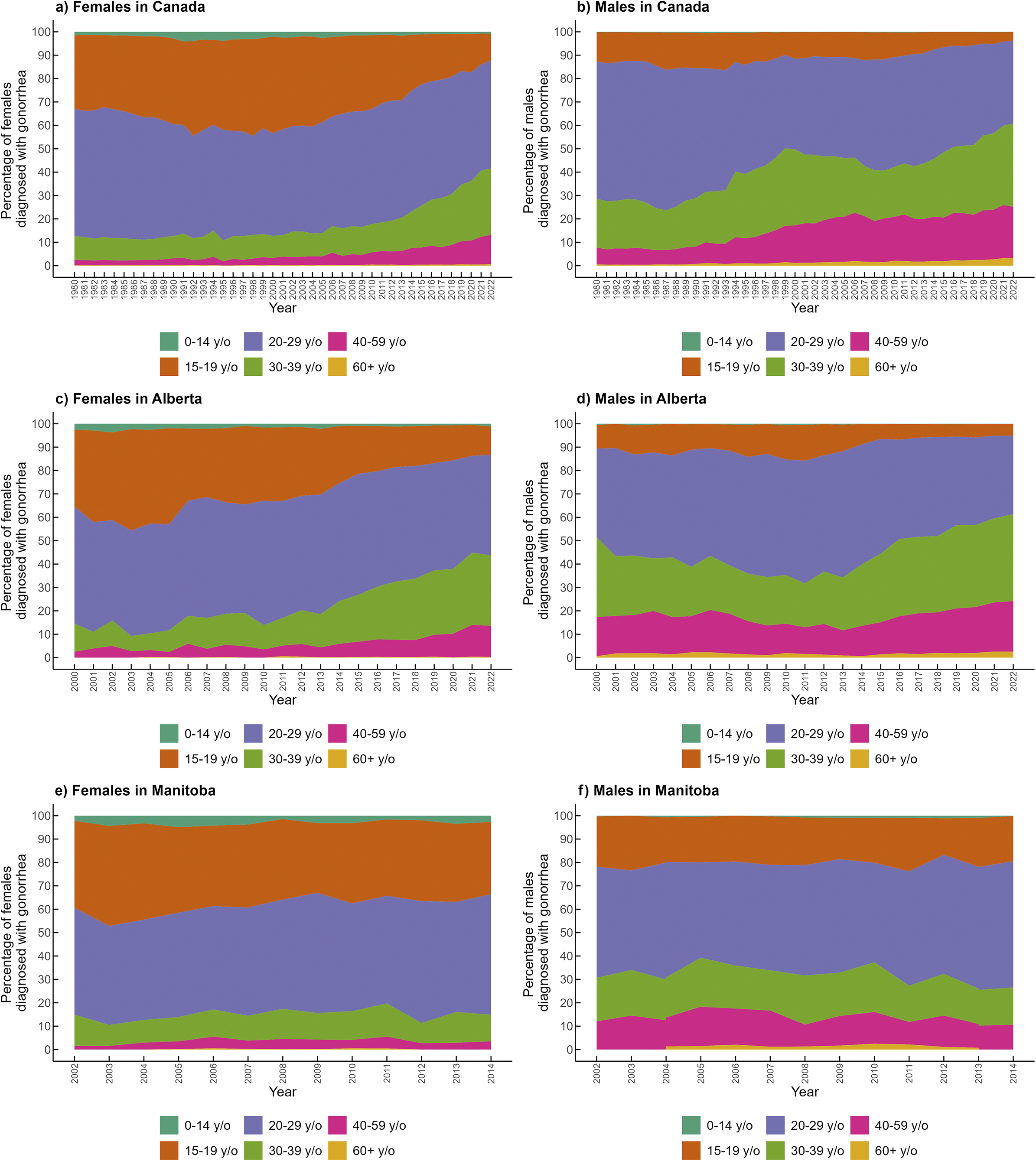

Overall, the most affected age group in females and males in Canada was 20-29-year-olds (Figure 3a,b). However, the proportion of cases in this age group has decreased among males, from 60% in the 1980s to less than 40% after 2018. In females, individuals aged 20-29 years accounted for approximately half of the cases over the period studied. Females aged 15-19 were the second-most affected group over time, but this has sharply decreased, currently representing around 10% of cases. The percentage of cases among females and males 30-39 and 40-59-years-old has increased over time. The rate of cases in Canada among people aged 15-59 years was 143.92/100 000 population (n = 30 779 cases) in 2021. We found in the age–period–cohort analysis that the highest rates of gonorrhea were in the age groups of 20 to 29, followed by 15 to 19, 30 to 39, and 40 to 59 for Canada and Alberta, and in Manitoba, the highest rates were in the age groups of 15 to 19, followed by 20 to 29, 30 to 39, and 40 to 59 (Supplementary Table S7). Saskatchewan was not included in the analysis because this province did not report gonorrhea cases by age group.

Figure 3. Percentage of gonorrhea cases by age group and sex in Canada (1980–2022), Alberta (2000–2022), and Manitoba (2002–2014). Panels: (a) Females in Canada, (b) Males in Canada, (c) Females in Alberta, (d) Males in Alberta, (e) Females in Manitoba, (f) Males in Manitoba. *In Manitoba, for the years 2002, 2003, and 2014, the 40–59-year-old age group includes all cases reported among individuals older than 40 years.

In Alberta, the age distribution of cases was available from 2000 to 2022, showing a similar distribution of cases by age compared to Canada (Figure 3c,d). In Manitoba, age-specific data by sex was only available from 2002 to 2014 (Figure 3e,f). The age distribution of female cases in Manitoba was similar to that of Canada, but among males, those aged 15–19 years accounted for twice the proportion of cases compared to males of the same age group in Canada. No reports on the age distribution of cases were available for Saskatchewan.

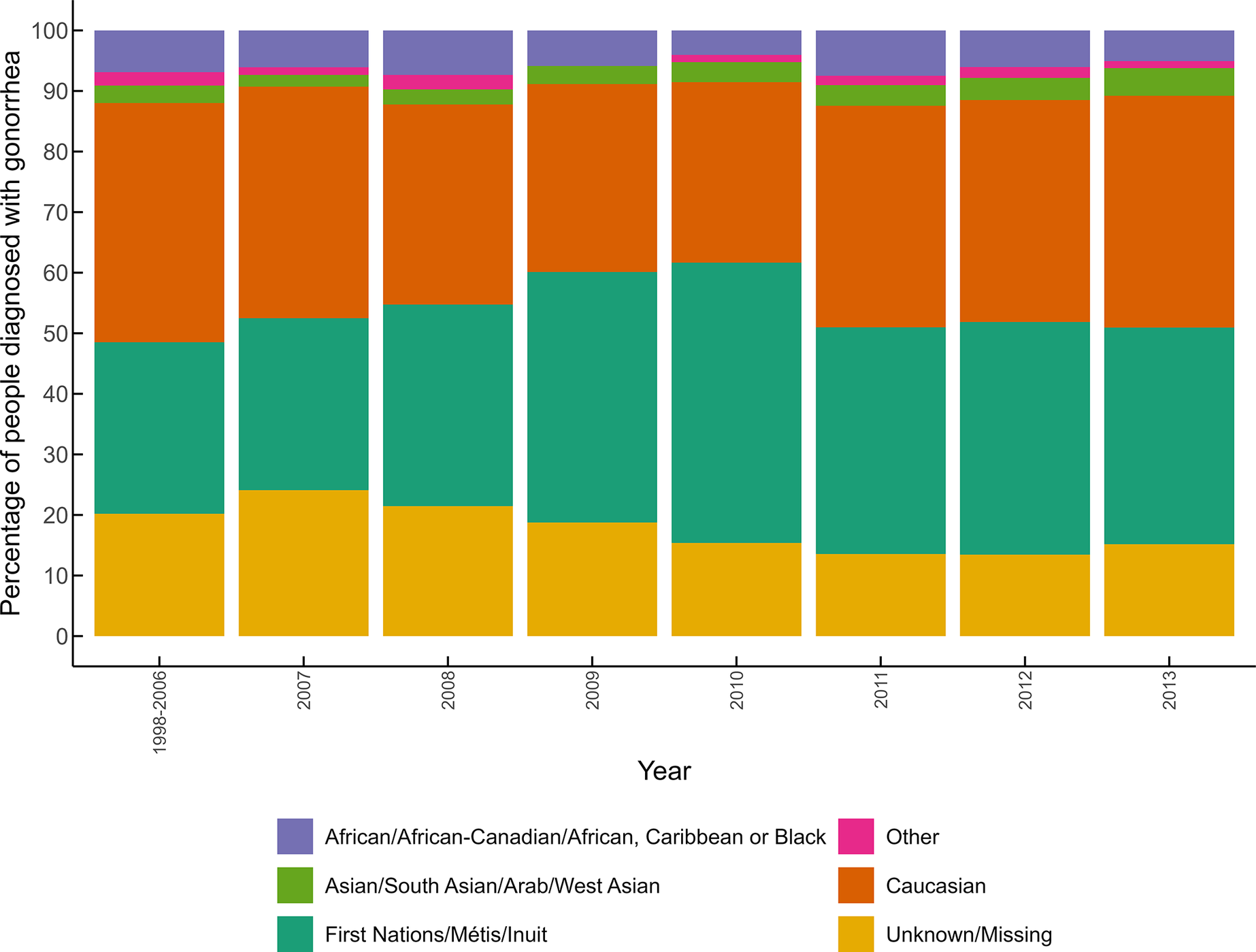

Canada and Saskatchewan did not report the rates of gonorrhea by ethnicity. In Alberta, available data from 1998 to 2013 show that although Indigenous people only represented between 4.6% and 6.2% of the population [38–41], this group accounted for 30% to 40% of all reported cases during that period (Figure 4). In Manitoba, Indigenous peoples represented around 15% of the population between 2001 and 2006 [Reference O’Donnell and Ballardin39, 40]. However, data from 2002 and 2003 reported that 49.1% and 29.5% of gonorrhea cases, respectively, had been diagnosed among this group. Information on other groups is only available for Alberta, where individuals identified as Caucasian accounted for 30% to 40% of cases from 1998 to 2013. Black and Asian groups represented together around 10% of cases over time, and 15% to 25% of cases had missing ethnicity data.

Figure 4. Percentage of people diagnosed with gonorrhea by ethnicities in Alberta from 1998 to 2013.

Data on sexual orientation, or associated risk factors for gonorrhea acquisition, have not been reported in Canada or the three provinces outside of ESAG data.

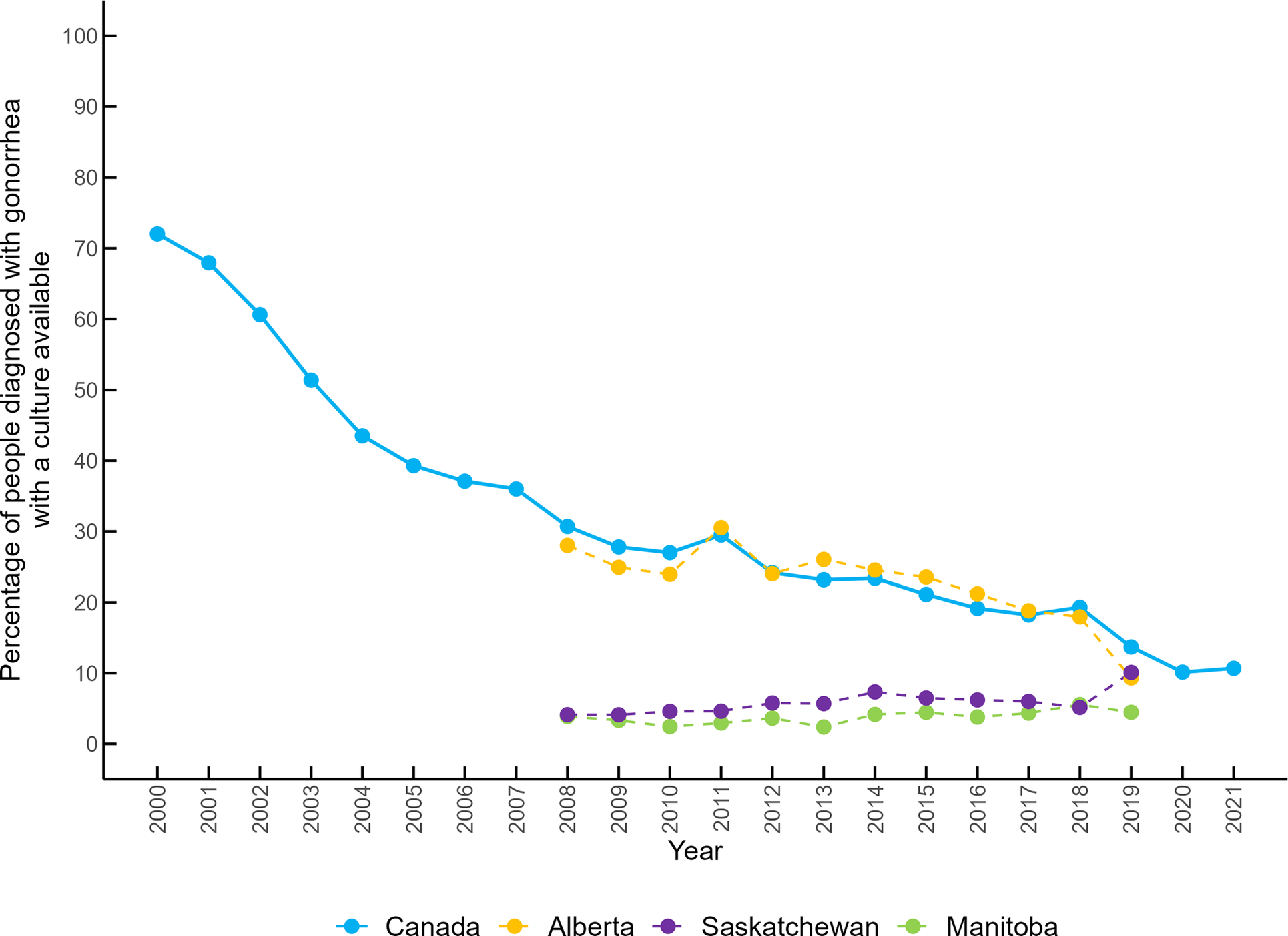

Gonorrhea diagnosed by culture

Overall, the percentage of cases with bacterial culture available has consistently decreased in Canada. In the early 2000s, approximately 60% to 70% of cases were culture-confirmed, but this proportion decreased to less than 20% after 2016 and to 10% in 2020 and 2021 (Figure 5). Alberta has a similar trend, with 28.02% of cases diagnosed by culture in 2008, and 9.32% in 2019. Available data from Manitoba and Saskatchewan show that the percentage of cases with a culture available was less than 10% from 2008 to 2019.

Figure 5. Percentage of gonorrhea cases with a culture available in Canada, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba from 2000 to 2021.

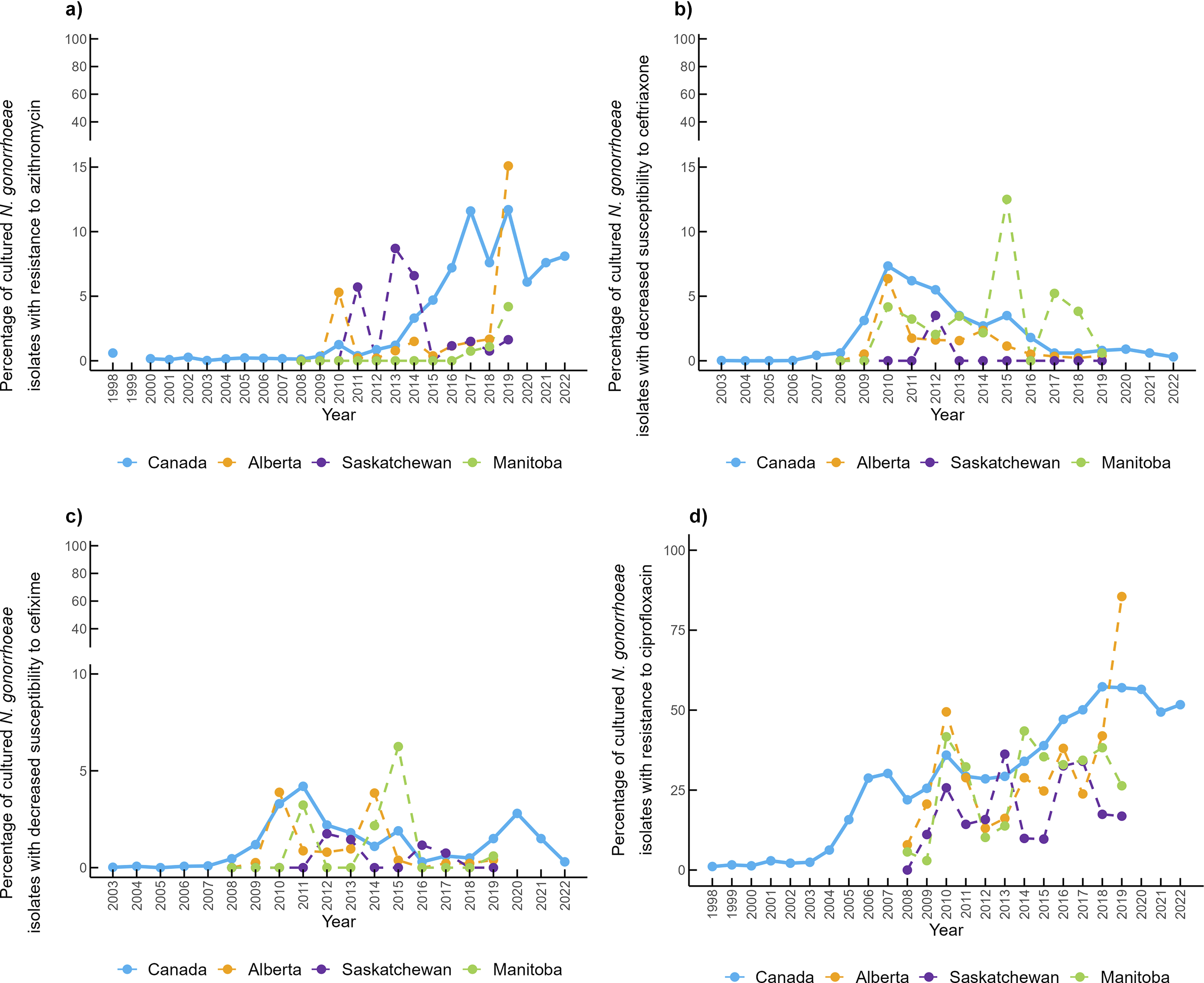

Antimicrobial resistance in gonorrhea cases

Provincial antimicrobial susceptibility data were available from 2008 to 2019 (Figure 6a). In Alberta, in 2010, 5.3% of clinical isolates were resistant to azithromycin (AZI-R), then dropped to <2% in subsequent years, before increasing to 15% in 2019. In Saskatchewan, AZI-R has also been below 2%, except for 2010, 2013, and 2014, where the percentage of resistant isolates increased to 5.71%, 8.7%, and 6.59%, respectively. In Manitoba, no resistance to azithromycin was reported between 2008 and 2016, but it has gradually increased to 4.19% in 2019. In Canada, azithromycin-resistant isolates accounted for <1% of cases before 2012. However, the percentage of resistant isolates has been increasing since 2013, to 11.6% in 2017 and 11.7% in 2019. After 2015, the percentage of azithromycin-resistant isolates consistently exceeded the WHO’s recommended 5% resistance cut-off and has remained above this level.

Figure 6. Percentage of Neisseria gonorrhoeae clinical isolates exhibiting (a) azithromycin resistance, (b) ceftriaxone decreased susceptibility, (c) cefixime decreased susceptibility, and (d) ciprofloxacin resistance.

In Alberta, 6.4% of clinical isolates in 2010 exhibited CRO-DS, but this decreased to around 2% between 2011 and 2014, and to 1% or less between 2014 and 2019 (Figure 6b). In Manitoba, between 2% and 4% of clinical isolates were CRO-DS, with notable peaks in 2015 and 2017 (12.5% and 5.2%, respectively). However, there were some years when no CRO-DS was reported in Manitoba. In Saskatchewan, CRO-DS was only reported in 2012 (3.5%). In Canada, CRO-DS gradually increased until 2010 to 7.34%, then declined to less than 1% from 2017 to 2022. CFM-DS has followed similar patterns to CRO-DS in Canada and the three provinces (Figure 6c). However, CFM-DS has only exceeded the 5% cut-off in Manitoba in 2015.

Ciprofloxacin resistance has consistently increased over time with some fluctuations in the three provinces (Figure 6d). Overall, Saskatchewan reported the lowest resistance to ciprofloxacin, while trends are similar between Manitoba and Alberta.

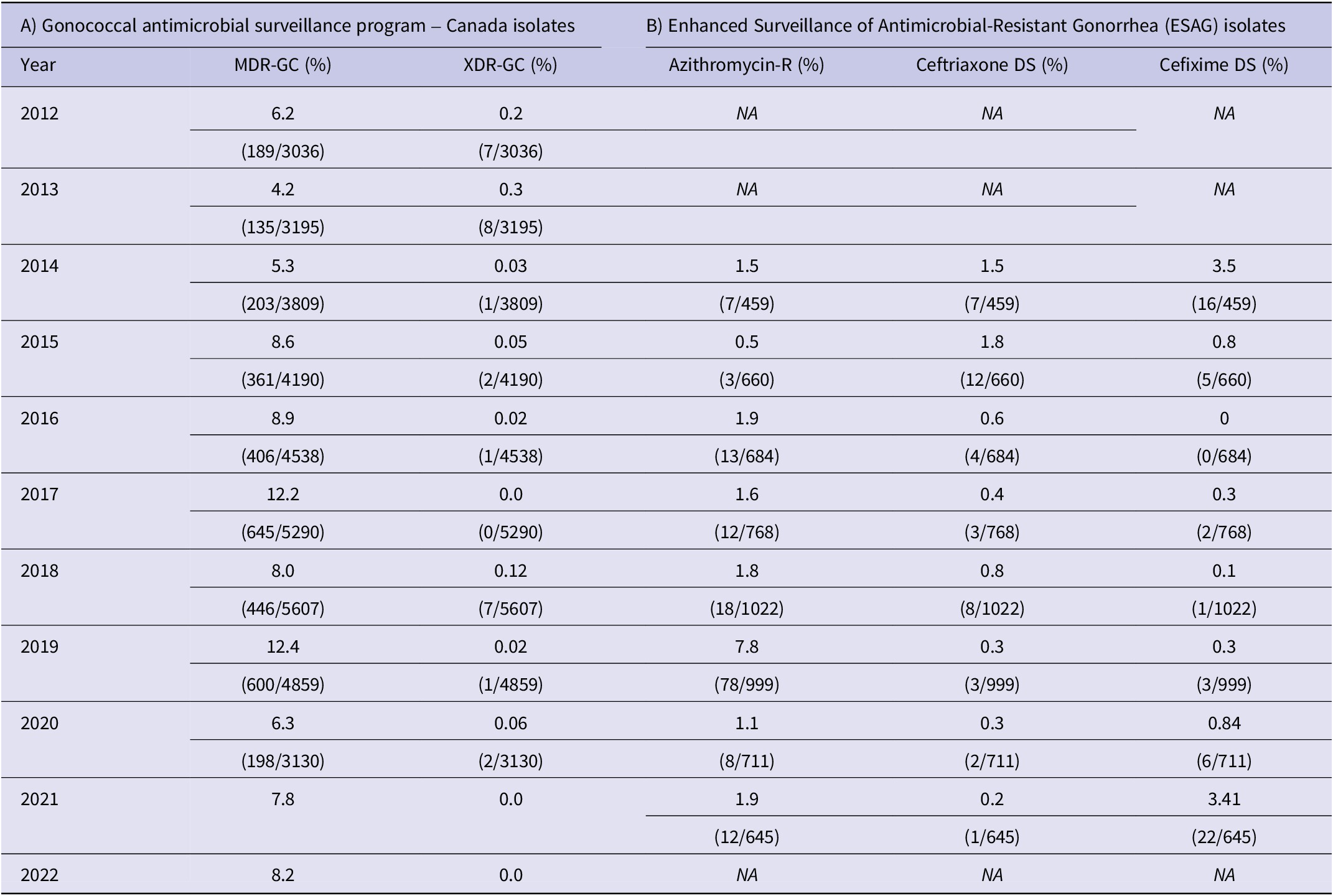

Data on other antimicrobials such as penicillin, tetracycline, and erythromycin are available for Canada (Supplementary Figure S2). The percentage of clinical isolates considered MDR-GC has fluctuated between 4% and 12%, and XDR-GC have ranged between 0% and 0.3% (Table 1).

Table 1. (A) Percentage of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant N. gonorrhoeae in Canada and (B) Enhanced Surveillance of Antimicrobial-Resistant Gonorrhea isolates resistant to azithromycin, ceftriaxone, and cefixime

Enhanced surveillance of antimicrobial-resistant Gonorrhea system data

Between 2014 to 2021, 80% to 90% of clinical isolates received by ESAG were submitted from sentinel sites in Alberta (Supplementary Figure S3). Submissions from Manitoba varied widely, ranging from 1.04% to 17.03% of the total number of ESAG cases. To date, Saskatchewan has not submitted clinical isolates to ESAG. More than 80% of submitted cultures were collected from males, with similar trends were observed in sentinel sites from Alberta and Manitoba. However, data were only available for sentinel sites between 2014 and 2017. Ethnicity was only reported for ESAG cases in 2014, showing that more than 90% of ESAG cases came from non-Indigenous populations. Caucasians accounted for 70.61% of cases in Alberta and 64.4% in Canada. Other ethnic groups accounted for approximately 16% of cases. No ethnicity records were available for 2.7% of isolates submitted from Alberta and 10.8% of all submitted isolates. Data on ethnicity were not reported for Manitoba. More than 70% of ESAG cases were individuals 20–29 and 30–39 years old. Province-specific age group data were only reported in 2014.

Data on sexual orientation and sex work status were also recorded for ESAG cases throughout 2014-2021. Approximately half of all ESAG cases were gbMSM, and 4% of cases engaged in sex work. HIV status of those who knew their status was only recorded in 2014 (2.4% diagnosed with HIV).

In ESAG cases, azithromycin resistance ranged from 0.5% to 1.9%, except in 2019 (7.9%) (Table 1). CFM-DS of ESAG cases remained less than 1%, except for 2014 (3.5%) and 2017 (3.41%). CRO-DS of ESAG cases ranged between 1.5% and 1.8% in 2014 and 2015 but remained less than 1% since then. Data for other antimicrobials (penicillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, and ciprofloxacin) were also available (Supplementary Figure S4).

Discussion

This study highlights the dramatic resurgence of gonorrhea in Canada and the Prairies, imitating the pre-1990s rates. A similar phenomenon has been described in other countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia, where the number of cases has been rising to rates not previously seen in decades [42–44]. This increase could reflect an increase in the incidence of gonorrhea, and in screening and testing practices [Reference Kirkcaldy8]. After its introduction in 1997 and full implementation in 2005-2008, NAATs replaced culture as the preferred diagnostic technique in Canada and was used to diagnose 90% of cases in 2020 [Reference Sawatzky45]. NAATs improved screening by allowing less stringent specimen-management conditions and enabling the use of non-invasive specimen-collection options, such as urine [Reference Bennett, Dolin and Blaser46]. Screening of extragenital sites of infection is emphasized in Canadian STI guidelines over recent years, which might have improved screening practices and therefore increased detection rates [Reference Choudhri47]. In addition, the list of individuals at increased risk in screening guidelines has expanded to include partners of sex workers, people older than 25 years with multiple sexual partners, and individuals with a history of STIs [10].

In Canada, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba have consistently reported rates above the national average from 1980 to 2022. Although these provinces represent only 18% of the Canadian population, by 2017 one of every three gonorrhea cases was reported in this region. Manitoba and Saskatchewan have been the most-affected provinces in the country, consistently reporting rates two to three times higher than the national average. After the early 2000s, females represented the majority of cases in these two provinces, changing the historical distribution by sex of gonorrhea in Canada.

A similar pattern is reported for HIV, where there is a 1:1 ratio between females and males, and in some years, even higher proportions of females newly diagnosed with HIV in Manitoba and Saskatchewan [Reference Rueda48]. A recent study found that 64.1% of females and 44.8% of males newly diagnosed with HIV had a prior sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBIs) diagnosis (gonorrhea was diagnosed in 42% and 23.3%, respectively) [Reference Sorokopud-Jones49]. Females newly diagnosed with HIV also face a disproportionate prevalence of substance use (86.2% vs. 74.9% in males), houselessness (43.1% vs. 28.7%), and mental health conditions (46.4% vs. 35.4%) [Reference Sharp50]. The intersection of these conditions has been linked to the rise in HIV cases in Saskatchewan and Manitoba compared to the rest of Canada [Reference Rueda48], highlighting the possibility of overlapping syndemics of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, such as gonorrhea. However, the lack of data on housing status, substance use, and other factors for gonorrhea cases limits the ability to identify the social and structural barriers that people diagnosed with gonorrhea are facing. Surveillance systems may benefit from collecting these data to demonstrate which populations are at higher risk of infection, thereby supporting targeted public health interventions and stronger advocacy for policy change. Some ideas may be to collect and report additional data to disaggregate gonorrhea cases by gender, sexual orientation, substance use (substance, frequency and patterns), race/ethnicity, and place of residence at enhanced gonococcal surveillance sites in STI clinics.

The proportion of cases among females and males aged 30-59 and in males older than 60 years is increasing and showing an upward trend. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), rates of gonorrhea diagnoses per 100 000 people among adults aged 35–44 and 45–54 in the United States increased threefold from 80.6 and 27.4 in 2000, to 217.1 and 83.3 in 2023, respectively [51]. Possible explanations for this include decreased testing due to decreased concerns for pregnancy in older adults, increased availability of drugs to manage sexual health problems, and a perceived lower risk for STIs among older adults, both by healthcare providers and patients [Reference Kaldy52]. At the provincial level, the limited availability of disaggregated data hampers the ability to compare trends between provinces and with Canada. Nonetheless, data from Manitoba highlight a regional disparity, as males aged 15–19 years accounted for double the proportion of cases observed in Canada between 2002 and 2014.

Our results also found that Indigenous peoples in Alberta and Manitoba are disproportionately affected by gonorrhea. In Alberta, Indigenous peoples were the most-affected group by ethnicity. The proportion of cases in this population was 6.2 times higher than their representation in the population. In Manitoba, the proportion was 2.8 times higher, although data were available for only two years. These findings are similar to those reported by Kirkcaldy et al. who reviewed the global data on gonorrhea among ethnic minorities across the world and found disproportionately high gonorrhea rates among Indigenous peoples in both the United States and Australia [Reference Kirkcaldy8]. In their review, gonorrhea rates among American Indian and Alaska Native populations were approximately five times higher than those among White individuals in the United States in 2017 [53]. Similarly in Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experienced rates seven times higher than non-Indigenous persons [54]. An increased burden of other STIs, such as HIV, chlamydia, and syphilis, compared to the general population, has also been described among Indigenous populations worldwide [Reference Minichiello, Rahman and Hussain55]. Several authors have explained that ethnic disparities in infectious disease rates can stem from historic institutional racism, displacement from ancestral lands and communities, and ongoing social and economic inequities, including differences in income, education, housing, healthcare access, and incarceration rates, which in turn collectively contribute to substance use and adverse sexual health outcomes in these communities [Reference Kirkcaldy8, Reference Adimora and Schoenbach56–Reference King, Smith and Gracey59].

As gonorrhea infection rates continue to rise, several public health strategies need to be strengthened to curb transmission. Expanded screening among populations at higher risk, timely identification and treatment of sexual partners, consistent use of test-of-cure practices, and the promotion of safe sex (including increased condom use) remain essential [Reference Unemo1, Reference Ewers, Curtin and Ganesan60]. Finally, emerging interventions such as doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis and doxycycline pre-exposure prophylaxis represent promising complementary approaches that may play a role in future prevention programs [Reference Boschiero61].

One of the most concerning findings of our study is the absence of publicly available reports that consistently publish data for every year in each province and across Canada, disaggregated on variables such as age, ethnicity, sexual orientation, housing status, coinfections with other STBBIs, and risk factors like substance use. Improving the collection and monitoring of comprehensive STBBI data is a key priority in the Government of Canada’s action plan to reduce the health impacts of STBBIs in Canada by 2030 and meet global commitments [62]. The availability of this information would help to facilitate more tailored public health interventions, especially for the most affected groups. As our data demonstrate, these groups vary by geographic area in Canada, underscoring the need for region-specific approaches.

Notably, as the proportion of cases with a gonococcal culture declines, comprehensive AMR surveillance in Canada is affected. Current recommendations prompt culture collection in specific populations such as those presenting symptoms compatible with gonococcal infection, pregnant females, asymptomatic sexual contacts of a diagnosed individual, and when sexual assault is suspected [63]. This approach might overestimate or underestimate AMR prevalence in certain groups, ultimately influencing the estimated prevalence in the general population. In fact, in 2021, 84.1% of cultures were collected exclusively from males, likely because urethral infection in males is more often symptomatic than in females [Reference Sawatzky45, Reference Bodie64]. Additionally, as submission of clinical isolates from provinces is voluntary and criteria for submission are not standardized across the country, available data may not be representative of nationwide AMR prevalence and are likely biased towards cases involving treatment failure and isolates from higher-risk individuals seeking care at clinics that specialize in sexual health and harm-reduction activities. AMR surveillance would likely be improved by the implementation of culture-independent methods for the detection of AMR [Reference Peterson65–Reference Pilkie67].

AZI-R in N. gonorrhoeae has been increasing worldwide. In the United States, the percentage of clinical isolates considered resistant to azithromycin has increased from 0.6% in 2013 to 5.8% in 2020 [68, 69], in Australia increased from 1.3% in 2012 to 3.9% in 2022, with a peak in 2017 (9.3%) [Reference Lahra70], and in Europe, reached 25.6% in 2022 [71]. Due to this rising azithromycin resistance, the CDC changed its recommendations for gonorrhea treatment in 2020, removing azithromycin as an adjunct first-line treatment option alongside cephalosporins, leaving monotherapy with ceftriaxone 500 mg intramuscularly as the only preferred therapy for urogenital, anorectal, and pharyngeal infections [Reference St Cyr72]. Some jurisdictions in Canada have updated their treatment guidelines to reflect these recommendations [73, 74], but dual therapy is still recommended in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba [75–77]. A review of the recommended therapies for gonorrhea in Canada is underway, but in 2024, the National Advisory Committee on Sexually Transmitted and Blood-Borne Infections issued an interim guideline recommending Ceftriaxone 500 mg intramuscularly in a single dose as the preferred option [78, 79]. Worldwide, the proportion of isolates exhibiting CRO-DS and CFM-DS has been decreasing since the early 2010s. By 2022, the prevalence of CRO-DS and CFM-DS remained low, recorded at ≤0.1% for both in the United States, 0.05% and 0.3%, respectively, in the European Union, and CRO-DS was reported at 0.51% in Australia [69–71]. Several factors have been hypothesized to contribute to the rise of gonorrhea AMR in Canada, including reduced capacity to monitor these infections, importation of antimicrobial-resistant strains through international travel, and the competitive advantage of resistant over susceptible strains [Reference Bodie64].

ESAG’s overall goal is to integrate epidemiological and laboratory data to improve the understanding of AMR trends for N. gonorrhoeae in Canada and to provide evidence to guide treatment guidelines and public health interventions [28]. Our results show that currently, most ESAG cases have been submitted from sentinel sites in Alberta, and available data from 2014 to 2017 show that the epidemiology of ESAG cases is different from the epidemiology of the population diagnosed with gonorrhea in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. ESAG cases are predominantly male (80%), whereas males accounted for approximately 56% of cases in Alberta and 45% in Manitoba during the same period. Province-specific age and sex data for the period during which ESAG has been active are lacking. Ethnicity and HIV status were available only in 2014 for ESAG cases, documenting that around 10% of ESAG cases were Indigenous, a proportion that is 3-4 times less than the proportion represented in the total number of cases in Alberta between 1998 and 2006, and 3-5 times less than proportions reported in Manitoba between 2002 and 2003. As ESAG included only four jurisdictions during the study period, AMR rates observed in ESAG cases have generally been lower than those reported nationally by GASP-Canada. Notably, azithromycin resistance was approximately three times lower between 2014 and 2021 (Supplementary Figure S5A-C). However, when ESAG data are compared exclusively with Alberta (the source of 89% of ESAG cases), AMR trends align more closely (Supplementary Figure S5D-F). There was no data regarding gender, sexual orientation, sex work status, housing status, substance use, among other important equity indicators of gonorrhea cases. Expanding data collection to include these variables and reporting disaggregated data could strengthen ESAG results, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of AMR trends both locally and nationally, and supporting more informed treatment guidelines and public health recommendations.

The main limitation of our study is the exclusive reliance on publicly available data from published reports. We did not have access to individual data from people diagnosed with gonorrhea, which means that the trends reported in this paper may be underestimated.

Conclusions

Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba bear a disproportionate burden of gonorrhea compared to Canada. Our findings demonstrate differences by sex and age between the three provinces and Canada. There is a decline in laboratory specimens submitted for gonorrhea culture, which limits surveillance for N. gonorrheae AMR. Available data reveal a sharp increase in azithromycin resistance over the past decade, thus supporting the removal of azithromycin from national gonorrhea treatment guidelines in Canada. Strengthening surveillance systems and expanding the collection of epidemiological data are crucial steps to better understand current infection and AMR trends. This timely surveillance system can inform targeted strategies and update clinical guidelines to address these growing concerns.

Abbreviations

- AMR

-

Antimicrobial resistance

- AZI-R

-

Azithromycin resistance

- CDC

-

Center for disease control and prevention

- CFM-DS

-

Cefixime decreased susceptibility

- CRO-DS

-

Ceftriaxone decreased susceptibility

- ESAG

-

Enhanced surveillance of antimicrobial-resistant gonorrhea

- GASP-Canada

-

Gonococcal antimicrobial surveillance program – Canada

- gbMSM

-

Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men

- MDR-GC

-

Multidrug-resistant N. gonorrhoeae

- MIC

-

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- NAAT

-

Nucleic acid amplification testing

- PHAC

-

Public Health Agency of Canada

- STBBIs

-

Sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections

- STI

-

Sexually transmitted infection

- WHO

-

World health organization

- XDR-GC

-

Extensively drug-resistant N. gonorrhoeae

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268825100885.

Data availability statement

The raw data extracted and used for our analysis are publicly available in Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/qwfgj/files/42dkc and the supplementary tables and figures.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: C.S.-A., Z.V.R. and Y.K.; methodology: Z.V.R.; writing—original draft preparation: C.S.-A.; formal analysis and data curation: C.S.-A., Z.G., M.A.-U., M.H., C.O., A.C. R.K., D.M., and L.L.; writing—review and editing: Z.G., M.A.-U., M.H., C.O., A.C. and R.K., A.E.S., S.S., C.S., L.J.M., K.K., L.I., I.M., J.B., D.A., D.M., L.L., M.H.-B., Y.K., Z.V.R.; funding acquisition and supervision: Z.V.R. and Y.K.; validation: D.M., L.L., and Z.V.R.; project administration: Z.V.R.

Funding statement

This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant numbers: PJH-185724, OS3-190782, PJT-195685). This research was also supported, in part, by the Canada Research Chairs (CRC) Programme for ZVR (Award # 950-232963). CS-A was awarded the scholarship “University of Manitoba Graduate Fellowship”, the “Graduate Enhancement of Tri-Agency Stipends (GETS) Program”, and the “International Graduate Student Entrance Scholarship”, all by the University of Manitoba, and receives an additional studentship from Dr. Rueda’s CRC funds. ZG was awarded a scholarship by the Canadian International Development Scholarships 2030 (BCDI 2030) program (www.bcdi2030.com) funded by Global Affairs Canada (GAC), and receives an additional studentship from Dr. Rueda’s CRC funds. MH received the CIHR Research Excellence, Diversity, and Independence (REDI) Early Career Transition Award (CIHR: ED6-190717).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.