Investigations of birth and population cohorts have found that people who develop schizophrenia are at increased risk (compared with the general population) of non-violent offending, and are at even higher risk of violent offending (Reference Arseneault, Moffitt and CaspiArseneault et al, 2000; Reference Brennan, Mednick and HodginsBrennan et al, 2000; Reference Mullen, Burgess and WallaceMullen et al, 2000) and of homicide (Reference Erb, Hodgins and FreeseErb et al, 2001). The proportion of people who have or who are developing schizophrenia who are convicted of crimes varies by country, and parallels but exceeds the proportions of criminals in the general population (Reference Mullen, Burgess and WallaceMullen et al, 2000; Reference Hodgins and JansonHodgins & Janson, 2002). In order to incorporate interventions designed to reduce offending into mental health services, it is necessary to know when offending begins, when such individuals first contact psychiatric services, and the problems that they present at first contact.

METHOD

Our study compared patients being discharged from forensic psychiatric hospitals in four countries – Canada, Finland, Germany and Sweden – with patients with the same primary diagnosis, gender and age being discharged from general psychiatric services in the same geographic region as the forensic hospitals. Consistent with findings from the epidemiological investigations cited above, almost all of the patients from the forensic hospitals were men and almost all had a principal diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or schizophreniform disorder. Consequently, the present study included only those men with these three diagnoses. Three questions were addressed.

-

(a) Were men with schizophrenia who committed serious violent offences that led to treatment in forensic settings previously in general psychiatric care?

-

(b) What proportion of men with schizophrenia treated by general psychiatric services have a record of criminality?

-

(c) Were problems present at the time of admission to general psychiatric care that indicated the need for treatments and services designed to prevent criminality?

Study procedure

Within each study site, each patient with a diagnosis of a major mental disorder about to be discharged from the forensic hospital was invited to participate in the study. If the patient formally consented to take part, a structured diagnostic interview was completed. If the diagnosis of a major mental disorder was confirmed, the participant was included in the study; the other interviews and assessments were completed and information was collected from patient records and family members. For each forensic patient recruited, a patient from a general psychiatric hospital in the same geographical region of the same gender and age (±5 years) and with the same principal diagnosis was identified and invited to participate. The same information was then collected from both sets of patients. Participants were asked for permission to contact their mother or an older sibling to collect family and childhood histories of them and their families. If the participant agreed, the relative was invited to participate.

Participants

The sample consisted of 158 consecutively discharged male patients with diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizophreniform and schizo-affective disorder who had received inpatient care from the forensic psychiatric hospital in one of the four sites. The study sites were selected because almost all – if not all – people with mental illness who are accused of crimes in these catchment areas are assessed prior to trial and sentenced to psychiatric treatment if the court is convinced that the person has committed the crime (Reference Hodgins, Tengström and ÖstermannHodgins et al, 2004). Seventy-four men with the same primary diagnosis and age were recruited from general psychiatric hospitals in the same geographical regions as the forensic hospitals. In total 232 patients consented (Canada, n=90; Germany, n=63; Finland, n=57; Sweden, n=22), representing, 72.8% of the male forensic patients and 57.8% of the male general psychiatric patients who were invited to participate in the study. All participants gave written informed consent to be interviewed at study entry and on five occasions during the 24 months after discharge, authorised access to medical and criminal records, and named a family member to provide information about them.

Information collected at discharge

Information on socio-demographic characteristics, mental disorders, criminality and substance misuse among parents and siblings, and problems and academic performance during childhood and adolescence was collected from the patient, his family, and from his school, medical and social service files. Information about all previous psychiatric treatment was extracted from hospital files. Information on criminality was extracted from official criminal files; crimes included both those that led to convictions and those leading to judgments of non-responsibility due to mental illness or diminished responsibility. Violent crimes were defined as all offences causing physical harm, threats of violence or harassment, all types of sexual aggression, illegal possession of firearms or explosives, all types of forcible confinement, arson and robbery. All other crimes were defined as non-violent.

Primary, secondary and tertiary diagnoses, lifetime and current, were made using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV (SCID) for both Axis I and Axis II disorders (Reference Spitzer, Williams and GibbonSpitzer et al, 1992). The SCID interview was administered by experienced psychiatrists trained to use this diagnostic interview protocol by those who developed the instrument.

Once all of the information had been collected from files, relatives and participants, the psychiatrist who had administered the SCID and assessed symptoms rated the case using the Psychopathy Checklist – Revised (PCL–R; Reference HareHare, 1991). Upon completion of training to use this instrument, psychiatrists were examined by rating English-language videotapes of interviews and case vignettes. The PCL–R includes 20 items, each rated 0, 1 or 2. Factor analyses have indicated that psychopathy is composed of two personality traits and an impulsive and irresponsible lifestyle (Reference Cooke and MichieCooke & Michie, 2001). The two personality traits are presumed to emerge early in life and to be stable over time (Reference BlairBlair, 2003). In our study only the score for Deficient Affective Experience was used, our hypothesis being that it is associated with repetitive violence. The Deficient Affective Experience score is the total score for four items: ‘lack of remorse or guilt’, ‘shallow affect’, ‘callous/lack of empathy’ and ‘failure to accept responsibility for own actions’.

RESULTS

History of prior treatment in general psychiatry

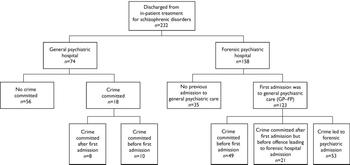

Of the 158 patients recruited from the forensic psychiatric hospitals, 123 (77.8%) had been admitted to a general psychiatric service at least once before committing the offence that led to admission to forensic psychiatric care (Fig. 1), with a mean of 5.6 admissions (s.d.=6.6). These 123 patients (GP–FP group) did not differ from the 35 patients with no prior admission to general psychiatric care with respect to age (GP–FP group: mean 40.0 years, s.d.=11.6; no prior admission group: mean=38.1 years, s.d.=10.01; t(156)=-0.902, P=0.368) and the proportion born outside the site country (10.6% v. 17.1%; χ2(1)=1.113, P=0.291).

Fig. 1 Profile of study sample.

Criminal records of general psychiatric patients

Of the 74 general psychiatric patients, 18 (24%) had a record of at least one criminal offence.

Offending prior to first general psychiatric admission

Ten of the general psychiatric patients (13%) had committed at least one offence before their first admission to general psychiatric care and another 8 (11%) had committed their first offence after their first admission. Among the 123 GP–FP patients, 49 (39.8%) had committed their first offence before their first admission to a general psychiatric ward; 21 (17.1%) had committed their first offence after their first admission to general psychiatric care but before the crime that led to admission to a forensic hospital; and the remaining 53 (43.1%) committed their first criminal offence some time after their first admission to general psychiatry, and the commission of this offence led to admission to a forensic hospital.

Ten general psychiatric patients and 49 GP–FP patients had a record of criminal offending before their first admission to general psychiatric services. We examined their criminal activities during the period when they were in and out of general psychiatric care (for the GP–FP group, we excluded the offence that led to admission to the forensic hospital). After their first admission to general psychiatric care, these 59 patients had committed 195 non-violent and 59 violent offences. In the GP–FP group, 70 patients had committed at least one crime before the offence that led to their admission to a forensic psychiatric hospital. Before committing the crime that led to this admission, these 70 patients had committed 270 non-violent crimes and 75 violent crimes. In addition to the offences counted above, the GP–FP patients committed on average 2.5 violent and 2.7 non-violent offences and those treated only in forensic psychiatric care committed 2.7 violent and 8.1 non-violent offences that gained them admission to a forensic hospital. Twenty-seven of the GP–FP group (22%) and 9 (26%) of the forensic care only group were admitted to forensic hospital following the commission of murder or attempted murder.

Were problems present at first general psychiatric admission that indicated needs for specific anti-crime interventions?

Table 1 presents comparisons between the group of participants (general psychiatric and GP–FP patients) who had committed crimes before their first admission to general psychiatric services and those with no criminal record. Patients in the former group were, on average, 5 years older at study entry than those with no record of criminal offending, and were also older at first admission. Proportionately more of those who had committed one or more offences before their first admission to general psychiatric care compared with the non-offenders were characterised by behavioural problems during childhood and adolescence, substance misuse before age 18 years, a diagnosis of alcohol abuse or dependence at first admission, and anti-social personality disorder. These characteristics would have been present at the time of first admission. A logistic regression equation was calculated to predict crime v. no crime, including the general psychiatry and GP–FP patients who had committed a crime before first admission to general psychiatry and the non-offenders. The predictors included only characteristics that would have been present and measurable at the time of first admission and that distinguished crime/no crime groups in univariate analyses. Three categorical variables were entered as predictors: antisocial personality disorder, being institutionalised before age 18 years and a diagnosis of alcohol abuse or dependence at first admission. Age at study entry was used as a control variable. A diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder increased the risk of offending 6.05 times (95% CI 1.92–19.04), having been institutionalised before age 18 years increased it 2.89 times (95% CI 1.05–10.84) and a diagnosis of alcohol dependence at first admission, 4.06 times (95% CI 1.52–10.82). Of the 59 patients who had offended before their first admission, 14 (23.7%) were not characterised by any of the four predictors, 19 (32.2%) were characterised by one predictor, 23 (39.0%) by two predictors and 3 (5.1%) by three predictors. The model could not be improved upon to a statistically significant degree by the addition of any further variables and yielded an overall likelihood ratio of 35.38 (P<0.001).

Table 1 Comparisons of men with schizophrenia who had or had not committed a criminal offence before first admission to general psychiatric services

| Crime before first admission (n=59) | No crime (n=56) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at data collection (years): mean (s.d.) | 41.2 (11.79) | 35.1 (10.62) | t(1, 113)=-2.935 P=0.004 |

| Characteristics at time of first admission | |||

| Born outside site country, % | 8.5 | 14.3 | χ2=0.968 (n=115) P=0.325 |

| Age at first hospitalisation (years): mean (s.d.) | 27.2 (8.24) | 24.0 (7.42) | t(1, 112)=-2.147 P=0.034 |

| Age at onset of prodrome (years): mean (s.d.) | 21.4 (5.13) | 20.0 (6.14) | t(1, 42)=-0.841 P=0.405 |

| Age at onset of schizophrenia (years): mean (s.d.) | 24.7 (7.60) | 22.90 (7.09) | t(1, 96)=-1.231 P=0.228 |

| Diagnosis of alcohol abuse/dependence, % | 49.2 | 14.3 | χ2=16.005 (n=115) P<0.001 |

| Problems present before age 18 years | |||

| Behaviour problems at home, % | 57.6 | 28.6 | χ2=9.870 (n=115) P=0.002 |

| Behaviour problems at school, % | 54.2 | 33.9 | χ2=4.801 (n=115) P=0.030 |

| Behaviour problems in the community, % | 49.2 | 16.1 | χ2=14.211 (n=115) P<0.001 |

| Substance misuse, % | 60.3 | 39.3 | χ2=5.5054 (n=114) P=0.025 |

| Institutionalised, % | 39.7 | 17.9 | χ2=6.582 (n=114) P=0.010 |

| Poor parenting, % | 28.8 | 12.7 | χ2=6.881 (n=114) P=0.032 |

| Diagnosis of conduct disorder, % | 37.3 | 10.7 | χ2=11.015 (n=115) P=0.001 |

| Characteristics at study entry | |||

| Antisocial personality disorder, % | 39.0 | 8.9 | χ2=14.089 (n=115) P<0.001 |

| Drug abuse/dependence, % | 59.3 | 26.8 | χ2=12.376 (n=115) P<0.001 |

| Deficient Affective Experience score: mean (s.d.) | 4.3 (2.04) | 2.63 (2.08) | t(1, 112)=-4.376 P<0.001 |

Patients who had committed crimes before their first admission to general psychiatric care differed from those with no history of crime at study entry as to their score on the PCL–R for the trait of Deficient Affective Experience (Table 1). It is likely that this trait would have been present at the time of first admission. The data do not permit us to establish the dates when patients first met diagnostic criteria for drug misuse and/or dependence.

Were problems present during general psychiatric in-patient treatment that indicated needs for specific anti-crime interventions?

A regression equation similar to that described above was calculated. Included in these analyses were the general psychiatric and GP–FP patients who had a record of criminality beginning after their first admission to general psychiatric care but (for the GP–FP group) before the crime that led to admission to a forensic hospital, and the general psychiatric patients who had committed no crime. The predictors included only characteristics that would have been present and measurable at the time of treatment in general psychiatry and that distinguished crime/no crime groups in univariate analyses at P=0.25 or less. Only two factors entered the model. The model could not be improved upon to a statistically significant degree by the addition of any further variables and yielded an overall likelihood ratio statistic of 17.41 (P=0.001). Behaviour problems in the community before age 18 years increased the risk of criminality 5.8 times (95% CI 1.79–18.99) and a diagnosis of alcohol abuse or dependence at first admission increased the risk 4.3 times (95% CI 1.27–14.53).

DISCUSSION

The study recruited men with schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder or schizoaffective disorder at discharge from forensic and general psychiatric hospitals in four countries. Seventy-eight per cent of the forensic patients had been admitted to general psychiatric wards before committing the offence that led to their admission to a forensic hospital. Twenty-four per cent of the general psychiatric patients had a record of criminal activity. Although 14% of the general psychiatric patients had committed an offence before their first admission to general psychiatry, 40% of the forensic patients admitted to general psychiatry had done so. The number of offences committed by these men during the period when they were receiving care from general psychiatric services is notable. These findings compel us to develop policies and procedures to identify patients engaging in antisocial and criminal behaviours and to provide them with interventions to prevent such behaviours. The human and financial costs of waiting to intervene until they commit a serious, violent offence are too high to tolerate.

Patients who have committed an offence before their first admission to general psychiatric services can be easily identified, either by asking them about their history of crime in a sympathetic yet challenging manner or by consulting official criminal records. As past criminality is the best predictor of future criminality (Reference Bonta, Law and HansonBonta et al, 1998), this information should signal a need for additional assessment, and for treatment, supervision and community placements designed to reduce antisocial behaviours. Failing to collect information on prior offending leads to the unacceptable situation described above, in which the complexity of the disorders presented by such individuals is not recognised and the necessary treatments and services are not provided.

Univariate comparisons indicated differences between patients offending before first admission to general psychiatric care and non-offending general psychiatric patients on problems present before age 18 years, alcohol abuse or dependence at first admission, antisocial personality disorder and Deficient Affective Experience score. A multivariate model of factors associated with criminal offending before first admission to general psychiatry services identified predictors that index antisocial behaviour (including substance misuse) that emerges in childhood and escalates in severity culminating in criminal offending. The diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder is given when an individual presents a ‘pervasive pattern of disregard for and violation of the rights of others occurring since age 15 years’ (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) and behaviours present before age 15 years that meet criteria for a diagnosis of conduct disorder as indicated by ‘repetitive and persistent pattern of behaviour in which the rights of others or major age-appropriate societal norms or rules are violated’ (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Prospective, longitudinal investigations conducted in several different countries have observed that approximately 5% of males display anti-social behaviour from early childhood which escalates in severity with age, until criminal offending begins during adolescence (Reference MoffittMoffitt, 1993). Such men commit most of the crimes that are committed (Reference Kratzer and HodginsKratzer & Hodgins, 1999). Even at young ages, the antisocial behaviour is accompanied by personality traits, callousness and insensitivity to others, novelty-seeking and cognitive deficits (Reference Moffitt and CaspiMoffitt & Caspi, 2002). These men meet criteria for conduct disorder in childhood and/or adolescence and for anti-social personality disorder in adulthood. For reasons that are currently not understood, both antisocial personality disorder – and by definition conduct disorder – are much more prevalent among men who develop schizophrenia than among men in the general population (Reference Robins, Tipp, Przybeck, Robins and ReigerRobins et al, 1991; Reference Kim-Cohen, Caspi and MoffittKim-Cohen et al, 2003).

At first admission, once the acute symptoms of psychosis have been reduced, assessment of childhood, adolescent and adult patterns of antisocial behaviour, attitudes and the personality traits associated with these patterns of behaviour is indicated. In our study, such an assessment would have demonstrated that patients who had already offended before their first admission presented needs for specific treatments aimed at reducing antisocial behaviours and attitudes, and increasing pro-social skills. Cognitive–behavioural programmes targeting these attitudes and behaviours have been shown to be effective in offenders who are not mentally ill (Reference McGuireMcGuire, 1995), and are being adapted and tested with offenders with schizophrenia. These patients also require an intervention aimed at ending misuse of alcohol, adapted both to the presence of schizophrenia and to antisocial attitudes and behaviours. Furthermore, once discharged to the community, these patients require more intense supervision to ensure that they take their medications and comply with other forms of treatment. Also, they need to be housed in neighbourhoods where they can neither easily associate with other offenders, nor access drugs and weapons (Reference SilverSilver, 2000).

Most general psychiatric services do not – and could not, at present – provide the kinds of treatments described above. General psychiatric services in most places would not have sufficient staff who are trained to conduct the type of assessments and implement the cognitive–behavioural programmes described, nor to provide the intense supervision required once patients are discharged to the community. Naturalistic follow-up studies indicate that court-ordered community treatment (Reference Heilbrun, Peters and HodginsHeilbrun & Peters, 2000; Reference Swanson, Swartz and WagnerSwanson et al, 2000) and legal powers to admit patients for short periods, involuntarily if necessary, contribute to reducing recidivism and prolonging safe community tenure (Reference Hodgins, Lapalme and ToupinHodgins et al, 1999). Such legal powers are useless, however, if in-patient beds are unavailable when needed. Further, general psychiatric services are often geographically based, so that patients are discharged to the neighbourhoods where they lived prior to admission, areas characterised by high rates of crime and drug use and low rates of employment.

The association of a stable pattern of antisocial behaviour with substance misuse is important. Children and adolescents who display conduct problems are exposed to alcohol and drugs earlier than others and an earlier onset of substance misuse is associated with persistence (Reference Armstrong and CostelloArmstrong & Costello, 2002). Even among people who do not have schizophrenia, the presence of antisocial personality disorder is associated with failure to benefit from substance misuse treatment (Reference King, Kidorf and StollerKing et al, 2001). Thus, intervening as early as possible with programmes specifically adapted to the needs of the patients is imperative. Furthermore, among children at genetic risk of schizophrenia, prospectively collected data indicate that high doses of cannabis in adolescence significantly increase the risk of developing schizophrenia (Reference Arseneault, Cannon and WittonArseneault et al, 2004). In addition, evidence suggests that men with schizophrenia sustain damage to specific neural structures from lower amounts of alcohol compared with men with no mental disorder (Reference Mathalon, Pfefferbaum and LimMathalon et al, 2002). Again, intervening early to reduce substance misuse is indicated.

Using comorbid diagnoses of conduct disorder and antisocial personality disorder is helpful in characterising a subgroup of patients with schizophrenia. These disorders, currently defined, index a stable pattern of antisocial behaviour that emerges early in life and remains stable well into adulthood (Reference Simonoff, Elander and HolmshawSimonoff et al, 2004). Men with schizophrenia who have displayed a stable pattern of antisocial behaviour from childhood have been shown to be similar to men with this behaviour pattern who do not develop schizophrenia, with respect to age at first crime and types and frequencies of crimes (Reference Hodgins and CôtéHodgins & Côté, 1993). Although there is little research examining the differences between individuals with conduct disorder who do and who do not develop a schizophrenic disorder, such differences are likely to be important, both for the development of effective treatments for antisocial behaviour and schizophrenia, and for advancing our understanding of aetiological factors. The repeated finding that it is more common for men who develop schizophrenia (compared with those who do not) to display an early-onset, stable pattern of antisocial behaviour suggests that there is a link between the two. This link and its determinants are poorly understood. Most importantly, there is no evidence, to our knowledge, about the response to early intervention programmes designed to reduce conduct problems among children who are at risk of later schizophrenia. If such childhood interventions were effective, they could reduce substance misuse in adolescence and thereby, perhaps, reduce the risk of schizophrenia. If schizophrenia developed, pro-social skills learned in a childhood intervention programme, along with the absence of antisocial behaviour and substance misuse, could have a positive impact on compliance with medication and the course of schizophrenia.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

Clinical Implications

-

▪ Men experiencing their first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder should be assessed for conduct disorder in childhood (prior to age 15 years) and for antisocial personality disorder and substance use disorders.

-

▪ Once psychotic symptoms are reduced, patients with a history of antisocial behaviour require cognitive–behavioural interventions aimed at changing antisocial behaviours and the associated attitudes and ways of thinking.

-

▪ These men require long-term care in communities that limit access to drugs and offenders and that support newly learned pro-social behaviours, attitudes and ways of thinking.

Limitations

-

▪ The forensic sample included only patients who had been discharged.

-

▪ Patients with schizophrenia and a childhood history of antisocial behaviour had a higher rate of refusal to participate than did patients with the same primary diagnosis but without a history of antisocial behaviour.

-

▪ Information on childhood and adolescence was obtained retrospectively.

Acknowledgements

The Comparative Study of the Prevention of Crime and Violence by Mentally Ill Persons is being conducted by S. Hodgins, PhD, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College, London, UK; D. Eaves, MD, Vancouver, Canada; S. Hart, PhD, Simon Fraser University, Canada; R. Kronstrand, PhD, Rättsmedicinalverket and Linköping University, Sweden; R. Müller-Isberner, Drmed, Klinik für forensische Psychiatrie Haina, Germany; C. D. Webster, PhD, Simon Fraser University and McMaster University, Canada; R. Freese, MD, Klinik für forensische Psychiatrie Haina, Germany; A. Grabovac, MD, Riverview Hospital, Vancouver, Canada; D. Jöckel, Drmed, Klinik für forensische Psychiatrie Haina, Germany; A. Levin, MD, Forensic. Psychiatric Hospital, British Columbia, Canada; E. Repo-Tiihonen, MD, PhD, Niuvanniemi Hospital, Finland; D. Ross, MSc, Riverview Hospital, Vancouver, Canada; P. Toivonen, MD, Vanha Vaasa Hospital, Finland; H. Vartiainen, MD, PhD, Helsinki Central University Hospital, Finland; A. Vokkolainen, Vanha Vaasa Hospital, Finland; Jean-Francois Allaire, MSc, Institut Philippe Pinel de Montréal, Canada; A. Tengström, PhD, Maria-Ungdom Research Centre, Karolinska Institute, Sweden.

Grants to support this study have been awarded by the BIO-MED-II programme of the European Union; in Canada, by the Forensic Psychiatric Services. Commission of British Columbia, the Mental Health, Law and Policy Institute, Simon Fraser University, Riverview Hospital; in Finland, by the Niuvanniemi and Vanha Vaasa State Mental Hospitals; in Germany, by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Institut für forensische Psychiatrie Haina; in Sweden, by the Medicinska Forskningrådet, Vårdatstiftelsen, National Board of Forensic Medicine, Forensic Science Centre, Linköping University, and Linköping University.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.