Introduction

Hip fractures, which are often a result of low energy trauma, are serious injuries commonly experienced by older people (Magaziner et al., Reference Magaziner2000; Marks et al., Reference Marks, Allegrante, Ronald MacKenzie and Lane2003). Worldwide, about 1.5 million hip fractures occur each year (Hernlund et al., Reference Hernlund2013). These injuries have a major impact not only on the person's long-term health, but also on informal carers, health services, and the community (Hirsch et al., Reference Hirsch, Sommers, Olsen, Mullen and Winograd1990). Globally, the 30-day mortality after a neck of femur fracture is between 7% and 9% and the one-year mortality ranges from 22% to 30% (Moran et al., Reference Moran, Wenn, Sikand and Taylor2005; Rae et al., Reference Rae, Harris, McEvoy and Todorova2007). Hip fractures also place a considerable burden upon the healthcare system because of the associated increase in morbidity. According to The REFReSH study group, total annual hospital costs associated with incident hip fractures in United Kindom were estimated at £1.1 billion (Leal et al., Reference Leal2016).

During hospital admissions, these people are at risk of developing complications including functional, physical, and cognitive impairments (Hirsch et al., Reference Hirsch, Sommers, Olsen, Mullen and Winograd1990). Poor general health, older age, cognitive impairment, and decreased activity level increase the risk of complications associated with hip fractures (Svensson et al., Reference Svensson, Stromberg, Ohlen and Lindgren1996; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhu, Chen, Sun, Cheng and Zhang2015). Studies have identified delirium as the most frequent complication among hospitalized older people and delirium is particularly common following a hip fracture (Gustafson et al., Reference Gustafson1988; Brauer et al., Reference Brauer, Morrison, Silberzweig and Siu2000; Edlund et al., Reference Edlund, Lundstrom, Brannstrom, Bucht and Gustafson2001). Delirium is a complex neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by acute and fluctuating course, inattention, altered level of consciousness, and evidence of disorganized thinking (Marcantonio, Reference Marcantonio2011). Marcantonio et al. (Reference Marcantonio, Flacker, Wright and Resnick2001) reported that 35–65% of patients who have undergone surgery for a neck of femur fracture repair suffered delirium post-operatively. A systematic review published in 2016 reported on risk factors for post-operative delirium following hip fracture repair. The results of a recent meta-analysis examining risk factors for delirium showed that patients with existing cognitive impairment, advancing age, living in an institution, heart failure, total hip arthroplasty, multiple comorbidities, and morphine use were more likely to experience delirium after hip surgery (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Zhao, Dong, Yang, Zhang and Zhang2017). Several studies have observed that patients presenting with delirium during the hospital stay have a worse prognosis, stay longer in the hospital, and have higher mortality rates, worse functional recovery, and higher institutionalization rates after hospital discharge (Francis et al., Reference Francis, Martin and Kapoor1990; Rockwood et al., Reference Rockwood, Cosway, Carver, Jarrett, Stadnyk and Fisk1999; McCusker et al., Reference McCusker, Cole, Dendukuri, Belzile and Primeau2001). Although delirium is known to be associated with poor clinical outcomes, health service planners and practitioners have largely accepted delirium as a common presentation (Inouye et al., Reference Inouye, Schlesinger and Lydon1999).

A number of studies have investigated interventions to prevent delirium, which can be grouped into multicomponent therapies and single interventions (Kalisvaart et al., Reference Kalisvaart, Vreeswijk, de Jonghe and Milisen2005; Overshott et al., Reference Overshott, Karim and Burns2008; Bjorkelund et al., Reference Bjorkelund, Hommel, Thorngren, Gustafson, Larsson and Lundberg2010; de Jonghe et al., Reference de Jonghe2014). The majority of single intervention studies focus on the impact of pharmacological interventions (Kalisvaart et al., Reference Kalisvaart, Vreeswijk, de Jonghe and Milisen2005; Overshott et al., Reference Overshott, Karim and Burns2008; de Jonghe et al., Reference de Jonghe2014). Effectiveness studies on the use of pharmacological interventions for delirium prevention show mixed results (Kalisvaart et al., Reference Kalisvaart, Vreeswijk, de Jonghe and Milisen2005; Overshott et al., Reference Overshott, Karim and Burns2008; de Jonghe et al., Reference de Jonghe2014). Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the effectiveness of drugs such as haloperidol and melatonin for prevention of delirium in hip fracture patients have been conducted (Kalisvaart et al., Reference Kalisvaart, Vreeswijk, de Jonghe and Milisen2005) but so far have failed to change the incidence of delirium (Kalisvaart et al., Reference Kalisvaart, Vreeswijk, de Jonghe and Milisen2005; de Jonghe et al., Reference de Jonghe2014). On the other hand, studies exploring the effect of multicomponent interventions have shown promising results (Bjorkelund et al., Reference Bjorkelund, Hommel, Thorngren, Gustafson, Larsson and Lundberg2010). Multicomponent interventions refer to more than one strategy to address the range of risk factors associated with delirium that can include pharmacological as well as non-pharmacological interventions; a number of studies suggest this approach is effective (Kalisvaart et al., Reference Kalisvaart, Vreeswijk, de Jonghe and Milisen2005; Bjorkelund et al., Reference Bjorkelund, Hommel, Thorngren, Gustafson, Larsson and Lundberg2010).

A Cochrane review published in 2007 examined interventions for preventing delirium in various older patients. Only one of the included studies involved people following hip fracture repair; in this study it was suggested that proactive geriatric consultation can reduce incidence and severity of delirium (Siddiqi et al., Reference Siddiqi, Stockdale, Britton and Holmes2007). In 2013, Thomas et al. published a systematic review regarding the effectiveness of non-pharmacological multicomponent interventions for delirium prevention; participants in the study comprised any elderly patient admitted to a non-intensive care unit. The findings of this review suggested that multicomponent interventions have a potential to reduce risk of delirium (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Smith, Forrester, Heider, Jadotte and Holly2014). More recently, two systematic reviews were undertaken on the same interventions but this time involving elderly patients with various medical conditions. As none of the reviews are specific to hip fracture population, a systematic review investigating effect of multicomponent interventions on incidence of delirium is warranted (Martinez et al., Reference Martinez, Tobar and Hill2015; Hshieh et al., Reference Hshieh2015).

Methods

Inclusion criteria

Types of participants

This review considered studies that included hospitalized patients aged 65 years and over, who sustained a hip fracture, irrespective of the mechanism of injury or method of treatment.

Types of intervention

Studies were included if they evaluated the effect of multicomponent interventions on incidence of delirium. A multicomponent intervention refers to the use of more than one strategy which can include but is not limited to: the use of specialized clinical staff/volunteers, geriatric/psychiatric consultation, staff education, patient orientation, addressing visual and hearing needs, sleep enhancement, medication review, hydration and nutrition, early mobilization, pain management, addressing bowel and bladder functions and prevention, and treatment of medical complications. This review did not exclude studies based on the dose of (e.g. intensity, frequency, and duration), or who delivered, the intervention.

Types of comparators

This review considered studies where multicomponent interventions had been compared to single interventions or usual care or no intervention.

Types of outcomes

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they measured incidence of delirium as a primary outcome. Only studies which determined the presence of delirium using standardized criteria or a validated tool (such as but not limited to Confusion Assessment Method (CAM), Mental Status Questionnaires, and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)) were included. Where reported, data regarding other outcomes such as discharge destination, length of stay, cognitive function, functional ability, and readmission were also extracted and presented in this review.

Types of studies

This review considered experimental studies, which presented information on an intervention group and information from a control group. This included RCTs, non- RCTs, and before and after intervention studies. This review also included observational studies such as prospective and retrospective cohort studies and case control studies as long as there was a control group.

Search strategy

The search strategy was designed to find both published and unpublished studies. A three-step search strategy was utilized in this review. An initial limited search of MEDLINE and CINAHL was undertaken followed by analysis of the text words contained in the title and abstract, and of the index terms used to describe the article. A second search using all identified keywords and index terms was then undertaken across all included databases. Third, the reference list of all identified articles was searched for additional studies. Only studies published in the English language were considered for inclusion in this review. The search was limited to studies published between 1999 to the present as multicomponent intervention strategies for the prevention of delirium began to appear in the published literature during this time (Morency, Reference Morency1990; Zimberg and Berenson, Reference Zimberg and Berenson1990; Wanich et al., Reference Wanich, Sullivan-Marx, Gottlieb and Johnson1992; Holt, Reference Holt1993; Bleasdale and George, Reference Bleasdale and George1996).

The databases searched via EBSCO and OVID platforms included MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Embase, and Web of science. Please refer to Supplemental File 1 for complete results and search terms used.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The initial search yielded 2,247 titles and abstracts from electronic searches (Figure 1). After duplicates were removed, 1,176 articles were reviewed for initial screening and 176 for next stage of screening. After inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, nine full text articles were included in the review.

Figure 1. Schema of the stages of searching and inclusion/exclusion of studies for the review.

Assessment of quality

The methodological quality of the studies was assessed by two independent reviewers (TO and LL) using standardized critical appraisal instruments from the Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-MAStARI). Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved through discussion.

Data extraction

Data was extracted from papers included in the review using the standardized data extraction tool from JBI-MAStARI. The data extracted included specific details about the populations, interventions (e.g. type, intensity, and duration), outcomes, and study methods. Data extraction was carried out by one reviewer with verification by another reviewer to minimize bias and potential errors in data extraction. Pooling of results was not possible due to methodological differences hence the findings have been presented in narrative form.

Results

Description of the studies

Nine studies met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Out of the nine studies, three were RCTs (Marcantonio et al., 2001; Lundstrom et al., Reference Lundstrom2007; Watne et al., Reference Watne2014). The total number of participants in the nine included studies were 1,889; 874 in the intervention group; and 1,015 in the control groups. Participants in the studies comprised of 75% females and 25% males. The average age of the participants in all the included studies ranged from 78 to 85 years. All the patients sustained various forms of proximal hip fracture. The studies originated from different parts of the world, including North America, Europe, and Australia. The patients included in the studies were mostly treated in orthopedic or geriatric ward settings. Bjorkelund et al. (Reference Bjorkelund, Hommel, Thorngren, Gustafson, Larsson and Lundberg2010) did not include patients who had prevalent delirium on admission. Characteristics of included studies are described in more detail in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies

The multicomponent interventions in the studies included common themes (Table 2) and four studies implemented consultation/assessment by a geriatrician. Marcantonio et al. (2001) implemented multicomponent interventions following proactive geriatric consultation of individuals in intervention group which began pre-operatively or within 24 h of surgery. Wong et al. Reference Wong, Niam, Bruce and Bruce(2005), Watne et al. (Reference Watne2014) and Deschodt et al. (Reference Deschodt2012) used the same model where recommendations were based on work done by Marcantonio et al. following a consultation by a geriatric registrar that formed a basis of treatment planning. The team consisted of geriatrician, nurse, physiotherapist, and occupational therapist. Milisen et al. (Reference Milisen2001) and Lundstrom et al. (Reference Lundstrom2007) focused their interventions not only on team work but also on staff education. Milisen et al. (Reference Milisen2001) implemented a nurse-led interdisciplinary intervention program where nurses were educated on early recognition and diagnosing delirium as they considered it essential for proper treatment. Consultative services were provided by a delirium resource nurse, a geriatric nurse specialist or a psychogeratrician and the model of care was based on work done by Inouye and colleagues. Inouye et al. (Reference Inouye, Wagner, Acampora, Horwitz, Cooney and Tinetii1993) Bjorkelund et al. (Reference Bjorkelund, Hommel, Thorngren, Gustafson, Larsson and Lundberg2010) implemented a new program including pre-hospital, perioperative treatment and care. Lundstrom et al. (Reference Lundstrom, Edlund, Lundstrom and Gustafson1999) conducted another study which also focused on staff education in caring, rehabilitation, teamwork, knowledge about delirium, risk factors prevention, and treatment. Holroyd-Leduc et al. (Reference Holroyd-Leduc2010) studied the application of a clinical decision support system that included an enhanced version of the hip fracture order set. The order set included elements of the multicomponent interventions followed in the studies by Marcantonio et al. (2001) and Lundstrom et al. (Reference Lundstrom2007)

Table 2. Themes of multicomponent interventions

Outcomes examined included incidence of delirium, duration and severity of delirium, cognitive function, activities of daily living, length of hospital stay, institutionalization at discharge and mortality. Although, all studies examined incidence of delirium, there was heterogeneity in both the statistical measures of frequency and diagnostic methods used.

Risk of bias in included studies

Studies varied in their methodological quality. RCTs were considered high quality for all items although participants and personnel were not blinded. All three RCTs (Marcantonio et al., 2001; Lundstrom et al., Reference Lundstrom2007; Watne et al., Reference Watne2014) included blinded assessment of outcomes. The three non-randomized trials (Milisen et al., Reference Milisen2001; Bjorkelund et al., Reference Bjorkelund, Hommel, Thorngren, Gustafson, Larsson and Lundberg2010; Deschodt et al., Reference Deschodt2012) were also considered high quality as all the items were reported on with the exception of multiple measurements pre- and post-exposure. It was not possible to comment on the quality of the two studies (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Niam, Bruce and Bruce2005; Holroyd-Leduc et al., Reference Holroyd-Leduc2010) as the methodology used in these studies has been poorly described.

Effect of interventions

We only considered randomized controlled studies for inclusion in a meta-analysis. We were able to conduct meta-analysis for one outcome (incidence of delirium) as other outcomes were not reported in a way that is appropriate for pooling. The impact of multicomponent interventions on outcomes is described in Table 3.

Table 3. Effect of interventions

Primary outcome

Incidence of delirium

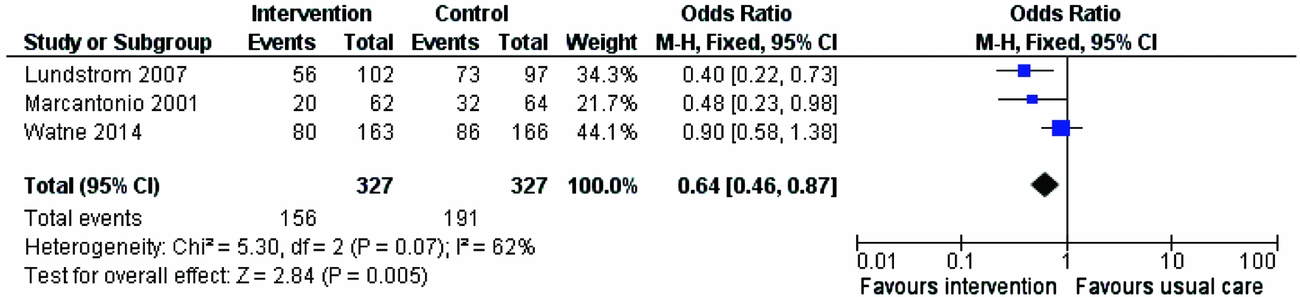

We pooled data regarding incidence of delirium from the three RCTs (Lundstrom et al., Reference Lundstrom2007; Marcantonio et al., 2001; Watne et al., Reference Watne2014). The effect was in favor of the intervention group (odds ratio 0.64, 95% CI 0.46–0.87) (see Figure 2). The remaining six studies all reported that incidence of delirium was reduced in the intervention group; the difference in incidence of delirium between groups ranged from only 2% in one study (Holroyd-Leduc et al., Reference Holroyd-Leduc2010) to 31% in another (Lundstrom et al., Reference Lundstrom, Edlund, Lundstrom and Gustafson1999).

Figure 2. Multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium vs. usual care: effect on incidence of delirium.

Duration of delirium

Six studies reported on duration of delirium (Lundstrom et al., Reference Lundstrom, Edlund, Lundstrom and Gustafson1999; Milisen et al., Reference Milisen2001; Marcantonio et al., 2001; Lundstrom et al., Reference Lundstrom2007; Deschodt et al., Reference Deschodt2012; Watne et al., Reference Watne2014). All three randomized trials reported that the duration of delirium was shorter in the intervention group than in the usual care group (mean 2.9 vs. mean 3.1 days(Marcantonio et al., 2001); median 3 vs. 4 days (Watne et al., Reference Watne2014); median 5.0 vs. 10.2 days) (Lundstrom et al., Reference Lundstrom2007). Data from these three studies could not be pooled due to the way in which they were reported. The other three/four studies reported on the duration of delirium with Milisen and colleagues (Reference Milisen2001) reporting statistically significantly shorter duration of delirium within the intervention group (median = 1 day, IQR = 1) compared with the non-intervention cohort) median = 4 days, IQR = 5.5). Two other studies (Bjorkelund et al., Reference Bjorkelund, Hommel, Thorngren, Gustafson, Larsson and Lundberg2010 and Lundstrom et al., Reference Lundstrom, Edlund, Lundstrom and Gustafson1999) reported that participants in the control group had longer lasting delirium than those in the intervention group however the differences between groups were not found to be statistically significant. Deschodt and colleagues found no differences between groups.

Severity of delirium

Four studies reported on severity of delirium (Milisen et al., Reference Milisen2001; Marcantonio et al., 2001; Deschodt et al., Reference Deschodt2012; Watne et al., Reference Watne2014). Marcantonio and colleagues reported that a smaller proportion of participants within their intervention group experienced severe delirium (12% vs. 29%), whereas Watne et al. (Reference Watne2014) did not find a statistically significant difference between groups. Milisen and colleagues (Reference Milisen2001) reported less severe symptoms of delirium were experienced by participants within the intervention group (ranges from 3.82 to 1.91 vs. 6.92 to 5.0) and Bjorkelund et al. (Reference Bjorkelund, Hommel, Thorngren, Gustafson, Larsson and Lundberg2010) failed to detect a statistically significant difference between groups.

Secondary outcomes

Discharge destination

Participant discharge destination was reported in five studies (Lundstrom et al., Reference Lundstrom, Edlund, Lundstrom and Gustafson1999; Marcantonio et al., 2001; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Niam, Bruce and Bruce2005; Holroyd-Leduc et al., Reference Holroyd-Leduc2010; Watne et al., Reference Watne2014). None of the studies were able to show a significant improvement in outcome in terms of more desirable discharge destination. Methods of reporting on this outcome varied across the studies. Four studies reported whether or not the person was discharged to a care institution while Lundstrom and colleagues (Reference Lundstrom, Edlund, Lundstrom and Gustafson1999) reported on the patients who were discharged to independent living. The difference between intervention and control group participants who were discharged to institutionalized care ranged from only 1% in one study (Watne et al., Reference Watne2014) to 7% in another study (Holroyd-Leduc et al., Reference Holroyd-Leduc2010)

Length of hospital stay

Length of hospital stay was reported in seven studies (Milisen et al., Reference Milisen2001; Marcantonio et al., 2001; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Niam, Bruce and Bruce2005; Lundstrom et al., Reference Lundstrom2007; Holroyd-Leduc et al., Reference Holroyd-Leduc2010; Watne et al., Reference Watne2014). Two (Marcantonio et al., 2001; Watne et al., Reference Watne2014) of the randomized trials reported no significant differences between groups whereas Lundstrom and colleagues (Reference Lundstrom2007) found significantly shorter length of stay in the intervention group (mean 28 (SD 17.9) vs. mean 38 (40.6) days). Of the remaining studies, three reported no significant differences, whereas Lundstrom et al. (Reference Lundstrom, Edlund, Lundstrom and Gustafson1999) found significant shorter post-operative hospitalization was experienced by the patients in the intervention group (12.5 days including rehabilitation time vs. length of stay excluding the rehabilitation time in patients of control group 1 and control group 2 was 17.4 and 11.6 days (Lundstrom et al., Reference Lundstrom, Edlund, Lundstrom and Gustafson1999). Interestingly, Watne et al. (Reference Watne2014) reported that the patients in the intervention group within their RCT had longer length of stay by three days, however, this was not statistically significant.

Cognitive function

Cognitive function was reported in three studies (Milisen et al., Reference Milisen2001; Deschodt et al., Reference Deschodt2012; Watne et al., Reference Watne2014) with only one (non-randomized) study (Deschodt et al., Reference Deschodt2012) demonstrating significantly higher proportion of participants experiencing cognitive decline at discharge within the control group than those allocated to intervention group (38.7% vs. 22.6%).

Functional and mobility status

Only three studies (Lundstrom et al., Reference Lundstrom, Edlund, Lundstrom and Gustafson1999; Milisen et al., Reference Milisen2001; Watne et al., Reference Watne2014) reported on functional or mobility status of the patients. Only Lundstrom and colleagues (Reference Lundstrom, Edlund, Lundstrom and Gustafson1999) suggested that a significantly higher number of participants were walking independently with walking aids on discharge (83.8% within the intervention group and 58.3% & 60.2% within Control group 1 and control group 2, respectively).

Discussion

This review included nine studies with evidence that multicomponent intervention strategies have positive effects on delirium in patients with hip fracture. Benefits appear to be predominantly in reduced incidence. Only two studies (Milisen et al., Reference Milisen2001; Lundstrom et al., Reference Lundstrom2007) suggested shorter duration of delirium and one study suggested less severe symptoms of delirium. One study (Lundstrom et al., Reference Lundstrom, Edlund, Lundstrom and Gustafson1999) demonstrated reduced length of hospital stay and a larger proportion of the participants returning to their previous living conditions. The same study also reported a higher proportion of patients were walking independently with a walking aid on discharge. Only one study (Deschodt et al., Reference Deschodt2012) demonstrated a significant difference in cognitive decline at discharge in between the intervention and control group.

All included studies initiated assessment/ consultation within 24 h of admission which then formed the basis for early care planning. Once delirium had developed, the multicomponent interventions did not appear to make a significant difference to the duration or severity of delirium.

All of the studies provided information about the multidisciplinary teamwork or clinical leadership in implementing the interventions. The common theme appears to be of early diagnosis and early management by specialist geriatric clinical staff. In general early assessment by geriatricians is associated with better outcomes and many national guidelines now include this as best practice (city Australian guideline and UK NICE guideline (Chesser et al., Reference Chesser, Handley and Swift2011; Chehade and Taylor, Reference Chehade and Taylor2014). Besides this, clinical staff consistently implemented targeted protocols/guidelines/electronic care pathways that addressed cognition, mobility, sleep/rest, hydration, nutrition, pain management, bowel and bladder function, along with prevention and management of any post-operative complications. The multicomponent interventions were varied and involved multiple strategies and disciplines but all the strategies addressed the significant risk factors in development of delirium in hip fracture population. A variety of clinical staff were involved, including doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapist, and social workers. All studies included components such as proactive consultation with a geriatrician and individual care planning.

The limited number of studies (including only three randomized trials) means that it is difficult to draw conclusions about which participant group may benefit most from multicomponent intervention. In the subgroup analyses conducted by Marcantonio and colleagues, interventions were more effective in reducing delirium among patients without prefracture dementia or activities of daily living impairment. Interventions may have been more effective within this subgroup because of timely diagnosis whereas delay in diagnosis of the underlying cause may contribute to the poorer outcomes in patients experiencing delirium superimposed on dementia (Fick and Foreman, Reference Fick and Foreman2000). The delay in diagnosis is maybe due to lack of clarity whether delirium just uncovers a previously unrecognized dementia or if leads to cognitive decline that increases the risk of developing dementia (Fick et al., Reference Fick, Agostini and Inouye2002). Some medications like benzodiazepines have been associated with cause of delirium in persons with dementia (Lerner et al., Reference Lerner, Hedera, Koss, Stuckey and Friedland1997) and both delirium and dementia have been known to have several common pathophysiological features (Eikelenboom and Hoogendijk, Reference Eikelenboom and Hoogendijk1999). Given these complexities, it possibly further delays the timely diagnosis of delirium superimposed on dementia. In our systematic review due to the relatively small sample size within these subgroups, these effects were not statistically significant. Another study (Lundstrom et al., Reference Lundstrom2007) demonstrated significant difference in duration of post-operative delirium in patients with dementia in the intervention group patients.

None of the studies assessed the economic impact of shorter length of hospital stay. We believe that if economic evaluations were performed in the studies that reported on shorter length of hospital stay this could have added up to significant figure as acute care hospital environment is highly expensive. Study conducted by REFReSH group reported that the hospitalization costs associated with each admission for hip fracture were £8663. Only one study (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Niam, Bruce and Bruce2005) reported that expense of the intervention as the registrars (of geriatric specialty) spent considerably more time (estimated at an extra of 3 h per day) with the patients than they had before the project started.

This review supports the findings of other reviews that multicomponent interventions are effective in reducing incidence of delirium. However, none of these reviews are specific to hip fracture patients and given that this patient group has a higher level of risk and a different set of precipitating risk factors for delirium and may therefore require a distinct set of interventions compared to other older patient groups, this systematic review will add value to the existing literature.

Within this review, most of the included studies were at risk of bias due to lack of randomization and blinding. Although most studies reported the benefits of multicomponent intervention, it is difficult to make assumptions about which particular approach is most beneficial. For example, which components are most likely to be beneficial or whether one particular multicomponent approach is superior to others. Additionally, the variability in the components of the programs means that there is a limitation for accurate replication.

Implications for practice

Early diagnosis is the most effective strategy to prevent delirium. To decrease the incidence of delirium, all hip fracture patients admitted to acute care setting should have preventative interventions, including review by geriatricians initiated as soon as soon as possible. Once delirium develops the multicomponent intervention strategies have limited efficacy in minimizing duration and severity of delirium. Prevention of delirium before its onset is of high importance in order to keep patients with hip fracture physically, functionally, cognitively independent as well as safely discharge them to their pre-injury place of residence. Educating staff on the importance of early screening for delirium is a valuable exercise as screening will prompt early management of risk factors.

Implications for research

More translational evidence on the best way to implement use of delirium prevention protocols is needed to assist clinicians. In addition, economic evaluations conducted alongside randomized trials would provide useful information which may convince clinical staff and policy-makers to invest more in delirium prevention.

Conclusion

In summary, early engagement of multidisciplinary staff particularly geriatricians who address the risk factors of delirium as soon as the patient present to the acute care environment is the key element of a successful delirium prevention program. The studies do not address which components within a program provide the most benefit for delirium prevention or management yet this systematic review reveals that people with hip fracture who received multicomponent interventions had a significantly lower risk of developing delirium as compared to those who did not.

Conflict of interest

None.

Description of author's roles

T. Oberai – designed the review, followed PRISMA guidelines completed the review, wrote the paper. K. Laver – assisted with data extraction, meta-analysis, narrative synthesis, and writing the paper. M. Killington – assisted with narrative synthesis of the studies. M. Crotty – clinical expertise in geriatrics and assistance with writing the paper. R. Jaarsma – designing the review and providing orthopedic clinical expertise.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Dr Lucylynn Lizarondo, who was the second reviewer in the critical appraisal process.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610217002782