In recent years scholars of the medieval Near East have increasingly turned to the vast and understudied literature, visual culture, and material remains of Eastern Christian communities and sought to incorporate their voices into new research (Fig. 1.1). Across the history of the medieval Near East we have witnessed a veritable “rediscovery of Middle Eastern Christianity.”Footnote 1 This rediscovery entails the incorporation of Sasanian Persia, Rabbinic Judaism, and early Islam in a more holistic way, rather than their being siloed in their own disciplines as in traditional scholarship. The spate of publications stemming from this rediscovery has come at an increasing speed, and this new scholarship has led not only to an expansion of the traditional canon of sources but also to a fundamental change in the narratives we tell about these periods. These narratives reflect a wide variety of issues. For instance, medieval Near Eastern history is no longer simply the history of Islam; Byzantine history and literary study is more than the history of Greek and Latin speakers; Byzantine visual culture is recognized as more than the visual production of Greek and Latin churches; the Qur’ān cannot be understood without a knowledge of early Byzantine Jewish and Christian traditions of biblical exegesis. These shifts partly stem from the growing recognition that Near Eastern Christian communities represented very significant populations in the eastern Mediterranean and Near East and that any attempt to understand these regions in the late antique or medieval period that does not take into account their presence and importance is incomplete and inadequate. In turn, and partly due to this rediscovery, Eastern Christian Studies – especially in the languages of Syriac, Coptic, Armenian (Fig. 1.2), and (Christian) Arabic – has experienced a renaissance and is entering something of a golden age, akin to the great flourishing it experienced in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

This book seeks to draw attention to these fundamental shifts but also to provide a vision for what future study might look like. We contend that Byzantine Studies is in the process of metamorphosing into something both grander and more inclusive. This book, while at times polemical, is ultimately hopeful for a longstanding field that we as authors and editors find to be a crossroads of world history. We argue for the incorporation of a broader list of cultures, languages, and scholarly traditions into the repertoire of Byzantinists and their students. The Roman Empire is only one piece of a larger nexus of powers, and its lifespan cannot serve as the single vein of history without distorting the cultural map. The detailed and often very specific histories presented in this book should find a place in an overarching perspective that gives new life and further impetus – indeed, increased vigor – to the entire history of the Near East. The challenge for this volume is that, of necessity, it has to be a collaborative effort. No single scholar has the competence to speak to all of the critical voices that are now part of the conversation. Because of this it is our contention that, to date, none of the received historiographical narratives are satisfactory. Our hope is to begin the process of retelling the story of Byzantium, collectively, and to contribute our own vision for what the story could be.

What of the relationship between Near Eastern Christian communities and the study of Byzantium as a mature academic discipline? In its attitude toward Eastern Christianity, Byzantine Studies can in some respects be seen as decades ahead of other fields. In 1980 Dumbarton Oaks hosted the famous “East of Byzantium” Symposium, which subsequently became an era-defining collected volume for researchers in many affiliated disciplines (see below). For many years now, it has been in the field of Byzantine Studies that students and scholars of Eastern Christianity have traditionally felt most at home among mainstream areas of research. Dumbarton Oaks has regularly offered fellowships to scholars working on Eastern Christian topics. And seminal journals, such as Byzantinische Zeitschrift, Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, and Dumbarton Oaks Papers, have published articles from fields that were previously considered auxiliary.

At the same time, however, the relationship between Byzantine Studies and Eastern Christian Studies has been characterized by a certain ambiguity: is the study of Byzantine history the study of only those parts of the eastern Mediterranean that were under the political control of Constantinople? Or, in the case of areas that were under the political control of Constantinople – like late antique Egypt (Fig. 1.3) or Syria – does Byzantine art history only include objects and monuments associated with Hellenic traditions? In some cases, institutional historiography has shaped the parameters of what is deemed legitimate, and as one example, art historians have largely left early Byzantine Egypt out of the discussion. If Byzantinists are open to the existence of a “Byzantine Commonwealth” (see below), does this commonwealth only include Slavic-speaking Chalcedonian Orthodoxies to the north of Byzantium and not the Greek, Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, Georgian, Ethiopian, Makurian (Nubian), Caucasian Albanian, South Arabian, and Arabic-speaking Christian groups to the south and east of the Byzantine Empire? We understand that comprehensiveness is impossible, including in the present book, but the acknowledgment of this broader continuum may, we hope, reorient expectations about what Byzantine Studies is and can achieve.

The tensions in this relationship can be highlighted by a few well-known examples: why should one regard centers such as the monasteries of St. Catherine or Mar Saba, most of whose medieval history was not spent under the political authority of Constantinople, as Byzantine, and at the same time relegate the Red Monastery of Egypt, or St. Antony’s (Fig. 1.4) and St. Paul’s monasteries, or the Monastery of the Syrians – all also in Egypt but belonging, confessionally, to the non-Chalcedonian world – to secondary or non-Byzantine status?Footnote 2 Why should John of Damascus, a Christian Arab who never set foot in the Byzantine Empire, be regarded as a major subject of study for Byzantinists, but Jacob of Edessa – his Syriac-speaking, non-Chalcedonian Syrian contemporary, who was likewise fluent in Greek – not similarly be central to Byzantine Studies?Footnote 3

1.4. Monastery of St. Antony at the Red Sea, general view of interior.

To reconsider the relationship between Greek-speaking, Chalcedonian Byzantium and the communities of the eastern Mediterranean and Near East (including those who were likewise Greek-speaking and Chalcedonian) is, in fact, to query the purview of Byzantine Studies. Is Byzantium something that is defined politically and linguistically? What has been the role of modern ethnic nationalism – Greek, Slavic, Arab – or religious sectarianism – (Chalcedonian) Orthodox, Catholic, Islamic – in giving shape to the field and determining, explicitly or implicitly, who and what are included or excluded?Footnote 4 Is Byzantium to be identified with the imperial church (the Greek Orthodox Church) or should it include all Christian (and non-Christian) confessions originally a part of the Eastern Roman Empire?Footnote 5 To what degree is East Rome itself, before or after the Arab conquests, too restrictive a matrix for eastern groups that continued to claim some affiliation with the Byzantine Empire, politically, confessionally, or notionally?

The purpose of the present volume, Worlds of Byzantium, is to call upon the field of Byzantine Studies to course-correct in the direction of a “Big Tent Byzantium,” that is, a conception of Byzantium that could incorporate more thoroughly the successes of Eastern Christian Studies. The volume is, in its core, based on papers given at the 2016 Dumbarton Oaks Symposium held in Washington, DC. Entitled “Worlds of Byzantium,” the Symposium was conceived of as a successor to the “East of Byzantium” Symposium and was meant to invigorate a fresh and expanded vision of what a broad-minded and inclusive Byzantine Studies could look like for the twenty-first century.Footnote 6

Our answer to the question of how these two fields relate to one another is a simple but powerful one: they are deeply and intimately related, so much so that one cannot be understood without the other. When speaking of Byzantium, we invert a longstanding practice and argue that cultural rather than political considerations should be privileged.Footnote 7 Implicit nationalist agendas (Greek, Slavic, Arab, Orthodox, Islamic) that have defined and policed the borders of Byzantine Studies, traditionally conceived, and that have at times led to the exclusion of scholars and topics not working in certain areas or primarily in certain languages, have distorted the field and have, we suggest, impoverished it, particularly in light of the intensive research devoted to what we often refer to in this volume as the “Byzantine Near East” in recent decades.

Against such views we advance the idea of an open and decentered Byzantium: this “Big Tent” Eastern Roman Empire included a variety of languages, confessions, and people groups and was not always coterminous with its political borders. Byzantine Studies can represent and indeed showcase this diversity. Constantinople was a center, but so were Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem, and Edessa; even a less familiar place like Panopolis could generate outstanding artistic and literary production, as could other kinds of centers, such as monasteries (Fig. 1.5) and pilgrimage centers.Footnote 8 The identity of these dynamic places and the cultural traditions associated with them were the result of interaction and exchange. What this means is that one cannot fully and properly understand the dynamics of artistic production in Constantinople without knowing about what was being created in Upper Egypt or Syria, much as, in reverse, one cannot understand the thought of Cyril of Alexandria or John of Damascus without an awareness of theological ideas in Constantinople.

1.5. White Monastery general view. Laser scan drawing by Pietro Gasparri. This image is used courtesy of the Yale Monastic Archaeology Project (YMAP; Stephen J. Davis, executive director). The terrestrial laser scanning of the White Monastery site was sponsored by YMAP and conducted in 2019 by Pietro Gasparri and his team from CPT Studio in Rome. The work was funded by a grant from the Antiquities Endowment Fund (AEF) administered through the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE).

Our approach emphasizes the insight that political boundaries and linguistic boundaries do not always constitute cultural boundaries. The Arab conquests of the seventh century led to a situation in formerly Roman territories of Byzance après Byzance, Byzantium after Byzantium, many centuries before and in contexts quite different from where this notion is commonly employed (for late Byzantium).Footnote 9 Christian missionary activity from within the Roman Empire meant that Roman forms of religious communal organization, Roman patterns of thought, and Roman traditions of visual representation spread well beyond the limits of Roman rule and continued to exist, develop, and flourish in places where Roman rule had been replaced or never in fact existed. Confronting Byzantine Studies with a robust field of Eastern Christian Studies brings to the center the issue of Byzantium after Byzantium as well as Byzance dehors Byzance, Byzantium outside of Byzantium.Footnote 10 This confrontation holds out the prospect of tremendously fruitful and profitable developments in Byzantine Studies.

The implications for the study of Byzantium of our alternative, expanded perspective are broad: approaches which privilege Greek, Chalcedonian Orthodoxy, Constantinople, imperial history, and the perspective of the metropole more generally, will be undermined and seen as incomplete and, indeed, as potentially elitist and exclusionary.Footnote 11 In their place, we offer a multicentric, polyglot, multi-confessional alternative whose geographical expanse includes all of the languages, traditions, and peoples of the Roman-ruled lands of the eastern Mediterranean and Near East, as well as areas and communities (such as the Sasanian Empire (Fig. 1.6), Georgia, or the Christian kingdom of Ethiopia) that were engaged with ideas that spread from within the Roman world. By emphasizing cultural connections, the mobility and transfer of people, objects, texts, ideas, and patterns of communal organization across linguistic and political boundaries, we put at the center of Byzantine Studies a world ripe for comparative study and we attempt to inject an enormously rich new set of materials and texts for study into the Byzantine canon.

While Worlds of Byzantium includes core papers from the 2016 Dumbarton Oaks Symposium, the present volume, in its scope, argument, and level of detail, has gone considerably beyond the material presented at that event. Many chapters were added in an effort to offer a more complete picture, while also putting our argument forward in the most robust fashion possible. The chapters are presented in three parts: I. Patterns, Paradigms, Scholarship; II. Images, Objects, Archaeology; III. Languages, Confessions, Empire. The nineteen chapters of this book offer a sustained, cumulative, and collaborative argument for the exciting and fruitful directions Byzantine Studies can take if it explicitly defines its relationship to non-Greek, non-Chalcedonian Eastern Christian texts and visual culture – and their communities and traditions – in inclusive and non-nationalistic manners. In the same way that the study of Late Antiquity, the medieval Near East, and the Qur’ān have been enormously enriched by embracing and incorporating the texts and traditions of Eastern Christianity into their remit, we argue, Byzantine Studies can profitably do the same. Indeed, since the various Eastern Christian traditions have their roots in the late antique world of the Eastern Roman Empire, Byzantine Studies is perhaps their natural home. Our goal has been to both parochialize traditionally dominant approaches and to offer a broad alternative that can attract the interest of scholars (and, crucially, new generations of students) to Byzantine Studies in the coming years.

In what follows, I will attempt to present some of the definitional problems that immediately occur when one tries to enunciate a new vision for Byzantine Studies. The “rediscovery of Middle Eastern Christianity,” as framed above, is really only the beginning. While first we must pose the questions, ideally, broad outlines of a new narrative will result. The problems provide a frame for what is ultimately an enormous canvas. Our solution, to look forward in the argument, is to seek granularity and precision in specific topics of research that can combine to form a larger picture. On a grand scale and over many centuries, I would suggest that this is ultimately the basis of a unity – a unity of vision as much as a unity in realia – in the Byzantine Near East. At the risk of oversimplifying before the argument is laid out, I will claim below that the Byzantine Near East was a notional confederation based upon an inherited Christian vision that asserted the perennial idea that God had worked through the Roman Empire to bring about the triumph of Christianity. There are, however, other voices, especially non-Christian ones, that have a say in that definition, and those will be brought forward in due course. Yet, to return to the beginning, the fundamental question before all questions is, in constructing the framework, what words do we use to describe it? As we will see, assumptions – about time, language, space – mean a great deal and definitions are important. I attempt below to lay out the assumptions of specific scholars and specific schools of thought, explaining how they relate to our enterprise as much as to one another. Their definitions of key terms, events, and institutions provide opportunities to refine and reorient the Byzantine Near East.

The phrase Byzantine Near East may, at first blush, suggest that its terminology is accepted and stable, but this is far from the truth. That said, the label “Near East” is somewhat easier to manage than “Byzantine,” so we can begin there. Traditionally, Near East has been associated with pre-Hellenistic history in Mesopotamia and the eastern Mediterranean (i.e. pre-Alexander the Great, d. 323 bce). Areas often enclosed by this label include the Levant, Iraq, Iran, Asia Minor, and Egypt.Footnote 12 The region covered is necessarily broad and ill-defined; in the words of an authoritative textbook on the ancient Near East, “It is important to be aware that the Near East has never been a neatly definable, coherent entity, but rather represents a series of overlapping economic, political, and cultural systems.”Footnote 13 In later periods this label includes the Caucasus, particularly for the Persian connections in Armenia and Georgia, as well as Central Asia to some degree (Fig. 1.7). In this book we have extended the inquiry south, to Nubia (Makuria), Ethiopia, Arabia, and the Red Sea littoral more generally. The benefit of the term Near East, even though it has its own baggage, is that it avoids the connotations of the term “Middle East,” which in modern shorthand implies the predominance of Arabic and Islam as well as including, accurately or not, Muslim North Africa.Footnote 14 Neither label typically includes the Black Sea steppe or Slavic languages and peoples. Several chapters in this book discuss these geographical boundaries, which are fluid by necessity. Kevin T. van Bladel’s chapter offers “Classical Near East” as an alternative, with a specific focus on the periodization of the Sasanian Empire. This is an important reorientation which helps center the contextualization of the Near East with regard to non-Byzantine frameworks.

1.7. A child’s coat with ducks in pearl medallions and a child’s pants, eighth century ce. Iran or Central Asia, Sogdiana. Silk: weft-faced compound twill, samit.

The term “Byzantine” is, in the context of this volume, much more difficult to define. Indeed, as noted, the attempted redefinition of such is the remit of this volume, so we begin with an assertion of the flexibility of the term. We argue that Byzantine Studies entails and affects more of the Near East, over a longer period of time, than typically recognized. This concerns the notional continuation of the Roman Empire according to those both inside and outside of Byzantium. Recent studies of what Roman means (versus Byzantine) in this period, in addition to Empire – and, indeed, whether Byzantium was truly an empire – are useful in a broad rethink of the medieval Mediterranean, but they largely ignore what those outside of Byzantium in the East considered it to be.Footnote 15 The shifting boundaries of the Byzantine Empire certainly affected this conception – for example, the reconquest of Antioch in 969 and related military maneuvers – but the political boundaries, whatever they may be at a given moment, seem not to have affected various allegiances (theological, political) on the ground, at least after a certain date.Footnote 16 The Balkan case is significantly different in this regard, as shown in detail by Christian Raffensperger’s chapter.

Thus, Byzantium is hardly coterminous with Eastern Christianity, even though the old label “Byzantine Orient” traditionally implicates the Christian population only.Footnote 17 Demographics of the ancient and medieval worlds are very difficult due to the lack of documentary sources and archives, especially in the Near East. Nevertheless, there is general agreement that Christians remained the majority population for many centuries after the Arab conquests in the seventh century.Footnote 18 Some have placed the tipping point from majority Christian to majority Muslim as late as the thirteenth century in certain locales.Footnote 19 Was there a felt connection to a notional Byzantium among the peoples of the East? How long did the collective memory of the Byzantine Empire or the cultural legacy of the Christian Roman world survive the conquests? Certainly, as will be seen repeatedly in this volume, collective memory of Rome was not limited to Christians alone, but the Christians naturally held different sympathies and antipathies toward Rome than did Muslims.Footnote 20 Moreover, each Christian confession had a different relationship with notional Byzantium based upon their history and linguistic and theological commitments.Footnote 21

What we have, therefore, are “worlds” of Byzantium. Each group in the Byzantine Near East represents its own microcosm of larger structural interactions that ultimately defined the region, up to the present day.Footnote 22 Doubtless, the question of power is intimately involved in these microcosms. Marriage and intermarriage, taxation, law and punishment, violence and conscription, forced conversion – these are just some of the structures that are evidenced by both micro- and macro-interactions.Footnote 23 In certain instances, religious communities also existed in the context of polities whose rulers identified with those communities both linguistically and (notionally, at least) doctrinally: such as, at times, the Ethiopians, the Armenians, and the Georgians. However, except in minor cases, Jews, along with Syriac and Coptic-speaking Christians, though collectively representing massive populations, did not share this political advantage. And so, in many regions of the Near East and over a long stretch of time, the numerical majority had no power or secular authority. Bishops and rabbis, rather than kings and courtiers, were diplomats and communal leaders. This reality leads to the remarkable realization that it was a Muslim caliph who was, at any given time in the medieval period, the ruler of the largest Christian polity, demographically speaking, in the world.Footnote 24 To put it a different way, “diversity” in the Near East does not imply minority: that is, the existence of numerous individual Christian confessions under Islamic rule must be coupled with their majority influence on the ground.Footnote 25

Is, therefore, Byzantium a notional or a political entity? I argue here for a notional definition. The scope of a political Byzantium is rather easy to define: it refers, simply put, to the activities – cultural, political, economic, and otherwise – that took place in territories under the political control of Constantinople, at least for most of the history of the Byzantine Empire.Footnote 26 A notional Byzantium is more complicated but is all the more powerful a concept as a result. A notional Byzantium is one in which cultural activities, social practices, forms of life, and habits of thought – whose beginnings and classical articulation took place in, and indeed were made possible by, the uniquely cosmopolitan context of the later Roman Empire – continued to be employed and developed. This book concentrates on the early and middle periods of the Byzantine Empire – that is, the Empire at its largest territorially – but the chronological scope dealt with here comes mostly after the Arab conquests and thus hardly touches at all territory governed by East Rome in this period. Nevertheless, there are good reasons for considering the Near East to continue to be Byzantine after the seventh century.Footnote 27 As will become clear, chronology is very much secondary to the issues represented in this volume.Footnote 28 Our emphasis is understandably cultural in that regard, yet, as noted, the political context is interwoven with the cultural and religious situation. Trade, communication, institutions, travel, and exchange – the fabric of any cultural grouping or polity – connected the Byzantine Empire proper with the Byzantine Near East with strong ties that perpetuated long entrenched attitudes toward the Roman Empire, even though these patterns had become outdated after the seventh century so far as political reality was concerned. Direct interaction was significant for the maintenance of notional community, one that transcended political borders – say, through trade or continued ecclesiastical encounters across borders – but more significant for our purposes is the fact that such interactions fueled a notional Byzantium long after recovering and reconstituting the late Roman Empire’s full political reality was impossible.

While the question is undoubtedly fraught, it is worth asking: What is an empire anyway? In his history of the Holy Roman Empire, Heart of Europe (2016), Peter Wilson offers three metrics for empire and rates their varying usefulness for his purposes.Footnote 29 The least useful, he suggests, is geographical size. Canada covers nearly 10 million square miles – larger than the empire of Alexander the Great – but no one considers Canada an empire. It is, rather, historical assumptions about geography that are more significant: “absolute refusal [in an empire] to define limits to either its physical extent or its power pretensions,” he notes. Geographical extent, therefore, is not unimportant, but its value is conceptual before actual. Was, for instance, the much diminished Palaiologan Byzantium still an empire? Byzantines in this period certainly thought it was.Footnote 30

A second metric, longevity, is often too relative to be of good use, but it does have the benefit of explaining how empires can outlive their founders, and it draws attention to the agency of social and environmental factors that perpetuate the empire.Footnote 31 Third and most useful, according to Wilson, is the metric of hegemony. Empires throughout history are universally tied to conquest and resistance, and it is this fact which makes them comparable. Focusing on hegemony, however, has the problem of perpetuating the “rimless wheel” model of empire, in which the peripheries connect to the center but not to each other. On this last point, one tangible effect of treating Eastern Christianity, which was by its nature interconnected, in the context of the Byzantine Empire is that it decenters Byzantium, in certain cases even parochializing Constantinople itself, insofar as the putative metropole becomes just one hub among many.Footnote 32 With all this said, regardless of the question of its center, Byzantium certainly qualifies as an empire.Footnote 33

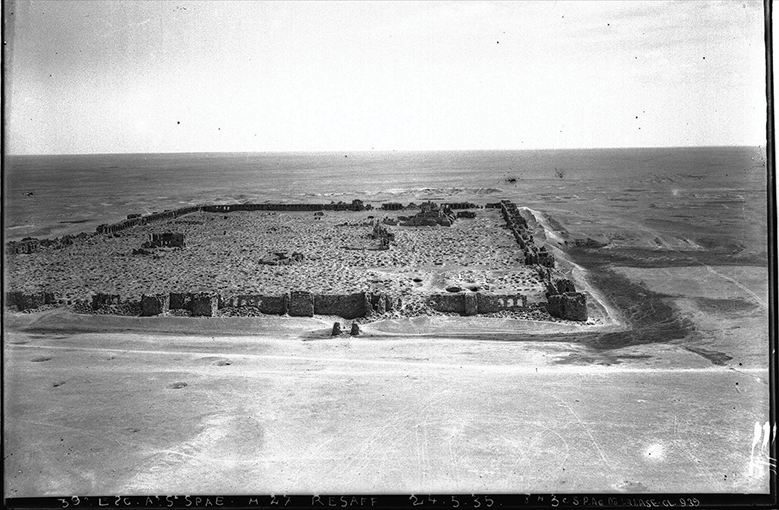

But the issue remains: if we were to conceive of Byzantium as larger – indeed, much larger – than its territorial borders and, within that notional space, exercising a kind of imperial, ideological hegemony among Eastern Christians, how does such a view work? What are the ties binding these worlds of Byzantium together? The model of center and frontier, or center and periphery, has long been a commonplace in Byzantine Studies and it continues to find many adherents.Footnote 34 Others have imported a kind of nebulous concept of “the provinces” – as opposed to administrative realities – for Byzantium via similar sloppy conceptualizations in Roman history.Footnote 35 The perspective of this book largely rejects the center–periphery model because it privileges the center of Constantinople above all – which, as it is traditionally invoked, is monoglot, monocultural, and politically monolithic, that is, everything that the Byzantine Near East is not.Footnote 36 Instead, this book foregrounds regional nodes (Fig. 1.8) with their own gravitational pull and influence, without of course ignoring the same pull of the imperial capital.

1.8. Raqqa, Resafa, aerial view. Taken May 25, 1935. Dry plate. Institut français du Proche-Orient – ALIPH.

The term “Commonwealth” has frequently been invoked in discussions about the limits of Byzantium, as a way of moving beyond (and indeed, escaping) what I have termed here the rimless wheel model. In this putative Byzantine Commonwealth, Constantinople was still the engine of unity but the spokes and the rim of the wheel, to break the metaphor, developed a kind of interlocked confederacy between themselves which became constitutive, in some measure, of their own identities and which they used to their mutual advantage. In 1971 the Byzantine historian Dimitri Obolensky published The Byzantine Commonwealth: Eastern Europe, 500–1453, an important study that has become the touchstone for modern thinking about the spread of Byzantium in eastern Europe (with a focus on the Balkans and what are today Russia and Ukraine).Footnote 37 The book’s periodization fit the history of the Byzantine Empire very well, beginning just before the reign of Justinian I and closing precisely with the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks. This periodization notwithstanding, the lead actors in Obolensky’s narrative were not the Greek-speaking Byzantines, but rather non-Greek-speaking Slavs.

Obolensky told the history of Slavic formation, development, and emergence as independent polities all in the sphere of Byzantium. The autocephalous status of the Slavic groups – the Bulgarians, the Serbians, the Rus’ – was always constrained by their dependence on Constantinople for higher education, patronage, and religious self-definition, not to mention the ubiquitous memory that it was Byzantine missionaries, Saints Constantine and Methodius, who converted the Slavs. Obolensky thus depicted a web of interlocking social and cultural nodes that became inseparably connected over time. However, in Obolensky’s web, ethnic identity was not the only material that knit the Slavic peoples together; instead, it was the dominant, even imperialist qualities of Byzantine society, language, and religion, beyond the boundaries of the Byzantine Empire itself, which provided the cultural semantics of the Balkan region during the medieval period. Thus, the central gravitational pull was still a force of unity.

One crucial difference between Balkan national, Orthodox identities and those among Eastern Christians poses a difficult problem for commonwealth as a concept. This is that, as noted, the majority of confessional and linguistic communities in the Byzantine Near East did not have states of their own. For Syriac and Coptic-speaking Christians – as much as for the Jews – the problem with commonwealth is, therefore, fundamentally political. How can a people united above all by a church or a language be part of a commonwealth with an imperial power if they are not political agents and have no state that acts on their behalf? In that case, commonwealth would be merely a metaphor and, even then, perhaps not of much explanatory value.

The closest analogue to the present volume is not, therefore, The Byzantine Commonwealth but, rather, East of Byzantium, the seminal collection published in 1982 that took its impetus from the 1980 Dumbarton Oaks symposium mentioned above. East of Byzantium focused specifically on Eastern Christian groups on their own terms. Its subtitle, “Syria and Armenia in the Formative Period,” signals an intentional demarcation of their subject. From its preface:

It was understood that the formative period in the Christian traditions in Syria and Armenia would be a subject of special interest to Byzantinists; Syria and Armenia were ever a stimulus and a thorn in the side of the Byzantine Empire. Nevertheless, our focus has not been on their impact on Byzantine culture, but on the distinctive traditions of their geographical area in and for themselves. Taking the ninth century as a later limit, we proposed to explore some of the forces that formed these early Christian cultures, the special symbiotic relationships among them, and their extraordinary accomplishment and maturity.Footnote 38

The book sought to treat various eastern traditions on their own terms and in their own “worlds,” even as they recognized that the overarching project would be of “special interest” to Byzantinists. But that special interest was intentionally kept separate, almost as coincidental, and there was no question of seeking to redefine what counted as “Byzantine.” This is despite the fact that East of Byzantium began as a symposium at Dumbarton Oaks, the bastion of Byzantine Studies in the United States, and was published by the same. It was without doubt a forerunner and highly influential but did not venture to question accepted categories of study.

Our volume differs from East of Byzantium in three main ways. First, as already noted, we are interested in the interactions between Byzantium (both real and notional) and the Eastern Christian populations which were, after the seventh century, beyond the political reach of the Byzantine Empire. We are also interested in Eastern Christian communities – Ethiopian (Fig. 1.9), for instance, and Nubian – which were never under the political control of Constantinople, but which nevertheless were, by virtue of their Christianity, connected to traditions and practices whose ultimate origins lay within the Empire. Secondly, among these eastern communities we include not just Eastern Christian groups but also Judaism, Islam, and Sasanian Persia. While we do not address these extra-Christian topics at the same length that we address Christian communities, we see them as central to how Eastern Christians created and protected their collective identities and voices in the late Roman and early Islamic Near East. Our remit demands this breadth. In addition, like the Eastern Christians, Judaism and Islam reached a classical articulation, in some measure, in relation to a broader Byzantium. Third, and more programmatically, we focus on communication, trade, and the transmission of ideas, recognizing the lesson of global history that geography cannot alone define the study of the Byzantine Near East.

These three points of difference are enmeshed with new concepts of chronology and problems of periodization. It could not be otherwise. For the definition of Byzantium itself is constrained by scholarly conventions of chronology – with the late Roman Empire on one end and the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople on the other. Dating Byzantium by the lifespan of Constantinople under Roman Christian rule (330–1453) only exacerbates the problem of impermeability. Thus, when Byzantium was is as debatable as what it was. East of Byzantium claimed the ninth century as the end of its investigation. We have purposefully chosen to offer a terminus that is rather more fuzzy: certain topics (e.g. pre-Coptic Egyptian art and architecture) are fixed in Late Antiquity or early Byzantium, while others (e.g. the history of Ethiopia) reach into the thirteenth century.Footnote 39 The subjects themselves determine the course of events, and, as with geography, chronological barriers are permeable.

If the turn to the East in Late Antiquity – especially in its incorporation of a broader range of languages and artistic centers – has taught us anything methodologically, it is that very real contact was happening across boundaries of language, polity, and confession. Sometimes the linguistic boundaries matched political and religious boundaries, but often they did not. Peter Burke, in his book Languages and Communities in Early Modern Europe, demonstrated in compelling detail how the interaction between language and community – whether national, confessional, or other – over time is highly complex: as he says, “every language has its own chronology.”Footnote 40 Burke asserted that language shapes the texts and meanings underlying cultural history. Sprachkulturen, or “language cultures,” demand understanding texts on their own terms as well as, at a basic level, valuing language communities that one is less familiar with. Alongside the considerations of periodization and methodology in our attempt to reconsider the category of Byzantium is the impulse to create a more inclusive discipline: that is, to develop and maintain sympathy for a breadth of cultures on their own terms.Footnote 41 Rather than placing the emphasis on chronology in demarcating a field of study, or even categories of expertise, an alternative and more useful metric to use would be concentrating on how widely structural entities in the period, both political and notional, extended geographically, culturally, and linguistically: that is, focusing not on the boundaries but the content. If Sprachkulturen have their own chronology, maybe we should let them run their course, and redefine our disciplines on the terms they set.

Late Antiquity as a defined subject has received criticism from some Byzantinists inasmuch as it threatens to subsume Byzantium. Anthony Kaldellis in an essay from 2015, “Late Antiquity Dissolves,” frames the problem as not primarily chronological but methodological. In his view, the varied emergent patterns of late antique studies – an emphasis on discourse analysis, for example, or gender studies – are potential problems and have supported, in turn, the heedless chronological expansion.Footnote 42 Kaldellis bluntly describes late antique studies as “imperialist.” Byzantium, he contends, has its own received modes of scholarship, with boundaries that should be respected. In a book review from 2020, he puts the argument as follows: “Late Antiquity purposely flouts the barriers and priorities of formerly different disciplines in order to create a common pool of discussion that is dominated by its own interests and skill-sets. That was (and still is) a great experiment, but it does come at the expense of, say, philology, paleography, intellectual history, theology, institutional history, political narrative, and the like.”Footnote 43 These latter modes of scholarship and expertise are staples of traditional Byzantine Studies.

Some of Kaldellis’s concern comes from Late Antiquity’s jettisoning of the Roman Empire as the lodestone of discussion. Fifty years ago, Peter Brown’s World of Late Antiquity already suggested vectors alternative to the Roman Empire, but, to grant Kaldellis’s point, the absence of Roman history in much of late antique scholarship today signals a remarkably different pedagogy in the background, a sea change which Brown could not have foreseen. It is increasingly the case, in the United States at least, that scholars of Late Antiquity are trained not in Classics or History but in Religious Studies, which tends to encourage the study of identity and gender, certainly more than political history, a field which their training eschews.Footnote 44 Traditionally, of course, if one is a Byzantinist, then one is studying East Rome, which lasted all the way until 1453.Footnote 45 In that schema the Roman Empire, as a political entity, is the justification not just for the periodization but for the discipline itself. The editors of the present volume are scholars of both Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages who find an exciting home in the Byzantine Near East as conceived in this book. As such, we resist Kaldellis’s vision of Byzantine Studies. We do this not as advocates of “Late Antiquity creep” but out of a desire to redraw the boundaries of what counts as “Greco-Roman,” “Mediterranean,” and “Byzantine.” We contend there are alternate, more profitable ways of thinking about our models and expectations.

As one example, a recent standalone volume of Past and Present, The Global Middle Ages, edited by Catherine Holmes and Naomi Standen – has brought to the fore the role that global history can play in advancing medieval research. As the chapters in The Global Middle Ages make clear, scholars are employing very different modes of global history and are theorizing it in different ways, but the exciting nature of the research and the enormous potential productivity of the paradigm are undeniable. Nevertheless, very little scholarship on “globalization” has taken up the theme for Roman and Byzantine history in comparison to other disciplines, something which makes their volume all the more valuable.Footnote 46 The present volume, in league with The Global Middle Ages, can be seen as fitting squarely within the developing field of premodern global history. The broader application comes from collecting somewhat disparate fields and topics under the same umbrella and emphasizing connectivity and shared change.Footnote 47 This enterprise is not merely comparative, however, since very real contacts were made across borders that some scholars would deem impermeable.Footnote 48 These studies bring to the fore long-distance interaction and exchange – trade, travel, imperialism, and networks of artistic and intellectual life – subjects that tend not to obey the traditional periodizations based on political borders.

This approach is often explained through what it is not. Thus, we find that global history is not “total history,” not “world history,” not “planetary history,” not even “macro-history,” at least not macro-history alone.Footnote 49 Global history does not propose to tell traditional narrative history across all parts of the globe simultaneously.Footnote 50 However, given that it is not total history, geographical frameworks become necessary: geography is not assumed, but it is part of the puzzle.Footnote 51 As François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar has explained in his book The Golden Rhinoceros: Histories of the African Middle Ages, the African Middle Ages can more profitably be defined by types of sources than chronology, or even the African continent itself: in terms of narrative texts, medieval Africa depends almost entirely on Arabic writers, mostly Islamic travelers or ambassadors from elsewhere.Footnote 52 Likewise, scholars of medieval Africa have problematized the familiar ecologies of Mediterranean history: the “Mediterranean Sahara” has received attention as a no-man’s-land which nonetheless facilitated the exchange of goods and ideas across language, empire, and religion.Footnote 53 How does one do medieval African history when it is difficult even to place cities on a map?Footnote 54 When each geographical region or time period requires different training and methodology, how can we reasonably impose such limits and coherence on history? Global history begins with the recognition that it must be multilateral in terms of discipline as much as in historiography itself.Footnote 55

While the present volume seeks to participate in the dynamic and evolving conversation about global history, our primary goal is to offer a specific argument about the definition of Byzantium.Footnote 56 The political centers, entrepôts, monasteries, and pilgrimage sites of the Near East were crucial nodes of connection between Byzantium and the larger network of medieval worlds. These external worlds were equally “worlds of Byzantium” both because of communications back and forth and also because Byzantium continued to hold a notional value throughout the Near East. The dual pulls of diffusion and attraction are forces within a larger matrix of mobility.Footnote 57 A “Big Tent Byzantium” is a very wide space in which to tell a story about the Middle Ages. The story cannot be told without identifying the actors and framing the grand questions around the specific peoples, texts, and art that individual locales represent. The chapters in this book seek to offer localized perspectives on Byzantium that collectively deterritorialize the received problems of Byzantine Studies.

In the first part, Patterns, Paradigms, Scholarship, the chapters approach the definition of a bigger Byzantium from several different, sometimes conflicting, angles. This section considers in detail how the development of Byzantine Studies relates to changing approaches to the Christian East and to paradigms drawn from related fields. Columba Stewart looks back at the seminal 1982 East of Byzantium volume, which became a catalyst for much later work but which was also very much of its period: it lacked a vision for the full integration of Byzantium, Islam, and the Christian East. Stewart offers a retrospective account of the rise of Eastern Christian Studies, with special attention to the biography of two important manuscripts, and then points forward to opportunities for new combinative scholarship. Averil Cameron draws attention to the “tectonic shifts” in Byzantine Studies between 1982 and the present, emphasizing the burgeoning number of publications and the shoring up of fields like Syriac. That said, as more is written on the Byzantine Near East, more controversies arise, not least of which is how to incorporate Islam. Cameron utters a word of caution, however: with the turn to the East we are in danger of losing the patterns of knowledge characteristic of Byzantine Studies. The long Late Antiquity puts Byzantium under threat. Kevin T. van Bladel in his chapter tries on the model of the “Classical Near East” as a means of overcoming disciplinary and institutional borders. He critiques the accepted definitional terminology of the Near East and explores how this transnational region could serve as an intellectual space transcending the barriers of previous generations. The Sasanian Empire could potentially serve as a better metric for the periodization of Late Antiquity than Rome, and, in any case, early Islamic Persia later became a significant center within the Byzantine Near East via, in part, the eastward push of Christian groups carrying Byzantine ideas and manuscripts. Christian Raffensperger suggests alternatives to the paradigm of commonwealth, which has dominated traditional views of Byzantium’s relationships with its Christian neighbors. He suggests that the core–periphery model discussed above needs to be modified in favor of local relationships, replacing an older model where the perceived unity of the commonwealth comes from Constantinople. Raffensperger raises critical questions of definition: can you have Eastern Christianity without an emperor? Conversely, is the Empire itself, in the end, a universal Christian construction? He suggests we think harder about Byzantium’s role in “world systems.”

The second part of the book, Images, Objects, Archaeology, turns to visual and material culture as a means of expressing the role and nature of Byzantium in the medieval Near East. A number of chapters in this section underline what has been called a “globalizing koinē” through the images, objects, buildings, and physical survivals of the greater Byzantine world.Footnote 58 This diverse set of studies considers large-scale exchange of images and artistic concepts while also rooting the history in highly specific individual cases, even down to a single object or monastery. Elizabeth S. Bolman’s chapter opens the discussion with a wide-ranging reinterpretation of “provincial” Byzantine visual culture in Egypt (Fig. 1.10), and expands to problematize the question of centers of artistic production throughout the empire. Rather than being derivative and peripheral, Egyptian art and architecture participated fully, and in many cases directly affected, styles and themes across the Near East. Her evidence within and far beyond Egypt shatters the traditional paradigm that the best art is always illusionistic, and that it was “naturally” made in Constantinople. The movement of objects and styles would suggest this was, in a way, a Mediterranean society, yet Bolman notes that the eastern Mediterranean is a fraught concept in terms of visual culture: what about Egyptian Christian art is Mediterranean? Alicia Walker reinscribes the place of Middle Byzantine art in the Near East through the example of pseudo-Kufic Arabic script. She challenges the center–periphery model by advancing a “pluritropic” framework of artistic connections, extending across the Mediterranean and fueling both the real and imaginative connections between cultural worlds. It may seem strange to ask, but what is the role of Arabic in non-Arabic Christian communities? A “Byzantium without Borders” allows for fluid adaptations of such foreign elements. Michael J. Decker considers northern Syria as it relates to the concept of the so-called “Dark Ages” of the seventh and eighth centuries, particularly in terms of economic continuity evidenced by archaeology (Fig. 1.11). Relatively little has been done on the demography and population of the Byzantine Near East, but Decker’s comparative work between regional centers suggests significant material continuity through the Dark Ages, a shift of perspective in recent scholarship, with far-reaching implications for agency and wealth among populations formerly belonging to the Byzantine Empire. Cecily J. Hilsdale demonstrates how style, “the look of something,” worked with language and ritual to help construct and solidify community. She analyzes the ars sacra of liturgical rhipidia (fans) from different confessions and eras of Eastern Christianity to break down and re-form the label Byzantine. The sharing of instruments of Christian worship across time and geography begs the question of what “foreign” even means in Byzantium. Objects carried cultural meaning and were markers of affiliation, yet they were often symbols of harmony and continuity as much as difference.

This second part continues with a chapter by Karel C. Innemée, Lucas Van Rompay, and Dobrochna Zielińska, who explain how the enormously important Monastery of the Syrians in Wadi al-Natrun, Egypt, can be studied as a “microcosmos” of the Eastern Christian world. Their chapter explores the complex and significant visual culture of the monastery, which sat alongside a vibrant manuscript tradition that had lasting effects on the history of Syriac literature and its modern study. Of particular significance is the engagement of Coptic and Syriac traditions, all within the context of a late Roman, early Byzantine, and Muslim Egypt that still held a kind of cultural and religious hegemony throughout the Near East. Christina Maranci examines the entanglements of Armenia and Byzantium through Armenia’s specific art history, one that was clearly within the Byzantine sphere, yet held close, definitive ties with Persia. This chapter focuses on the question of agency in visual culture while reveling in the mobile, fluid, and shared nature of artistic relations across Armenia and the Byzantine Empire. Localization and interconnectedness are not, for Maranci, mutually exclusive. Włodzimierz Godlewski calls the middle kingdom of Nubia, Makuria, an “African version of Byzantium” where direct connections between Makuria and the Byzantine Empire – including the extensive liturgical use of Greek – shaped local practice. In particular, architecture and wall paintings show how flourishing local art could depict a sophisticated and complex society, with its royal court, monastic communities, and substantial artistic and architectural remains, in touch with, and transforming, Byzantine traditions. As with Ethiopia, Makuria offers evidence that these kingdoms in Africa, which were never a part of the territorial Byzantine Empire, show just as much interconnectedness as more traditionally Byzantine societies in the Near East. Godlewski reminds us that once traditional, vague ideas of influence are discarded, a clearer picture of Byzantine relations comes through and agency is far more broadly distributed.

In the third and final part, Languages, Confessions, Empire, the chapters consider the textual and linguistic cultures that emerged in and around the Byzantine Empire, with special emphasis on what was left to these worlds of Byzantium after they found themselves under a new imperial power, the Islamic Caliphate. Jack Tannous details the history of Melkite (i.e. Chalcedonian) Syriac, an understudied topic that has direct bearing on what we call “Byzantine” in the medieval Near East. Although in communion with Constantinople, the Melkites nevertheless lived completely outside the Empire. The phrases “Byzantine Syriac” and “Byzantine Arabic” get right to the heart of how religious or political allegiance does not necessarily capture the experience on the ground in the Near East. Christians of the Muslim-ruled Near East were just as much heirs to Byzantium as those living under the Byzantine Empire in Anatolia or the Balkans. Hieromonk Justin of Sinai demonstrates how Greek remained a touchstone of St. Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai even as the monastery developed a remarkably international and multilingual population. The history of monastic practice, exemplified by the Ladder of Divine Ascent by John Climacus, kept the Sinaite monks linked to their Chalcedonian coreligionists throughout the Mediterranean. Monks and monastic practice crossed borders not only through travel and communication but through a shared repertoire rooted in Greek texts. On the basis of this evidence, he asks: was Sinai Byzantine? was Jerusalem? Can holy centers help us understand such labels? He points to a very specific locus of transnational community: the Justinianic altar at Sinai with its Greek inscription is still in daily use today. Daniel Galadza’s chapter continues the theme of Chalcedonian linkages by exploring the “Byzantinization” of the Jerusalem liturgy (Fig. 1.12), meaning the gradual homologation of the worship of the Holy City with that of Constantinople. This occurred in phases but, significantly, is often primarily evidenced through Georgian liturgical calendars. In this sense, a para-Byzantine culture became a conduit for Hagiopolite Byzantinization, all happening outside of the Empire. This world was intensely interconnected: Jerusalem looked to Constantinople for financial support but, equally, received the same from the East Syrians. All this was going on while Palestinian monks, including Georgians and Syrians, were traveling back and forth to Sinai carrying liturgical manuscripts of varying confessions. Eve Krakowski explains how the Jewish yeshiva became a symbol of Rabbinic Judaism in its most transnational guise under early Islam. Up to the new developments that came in under the Abbasids, late antique yeshivot maintained a consistent profile. In many ways, however, the move of the Caliphate to Baghdad shifted allegiance away from Palestine and toward a more global conception of Rabbinic-Byzantine Judaism. Jewish Palestine’s authority over the calendar, for instance, was only claimed because it was Palestine, the putative authority over Jewish pedagogy and worship. Yet, at the same time, we know now that so-called “Palestinian” and “Iraqi” Jewish texts may actually have had nothing to do with national or regional borders, suggesting a highly mobile and flexible Byzantine Judaism (Fig. 1.13) in the Near East.

Three Christian kingdoms in the Byzantine era – Ethiopia (Fig. 1.14), Armenia, and Georgia – round out the volume and offer an important retrospective view of the role of nationhood and conversion within the Byzantine sphere. George Hatke tells the long history of Ethiopian Christianity through the lens of its connections to the broader Byzantine network of cultural and political resonance. The problems associated with the concept of “frontiers” become acute when one of the earliest Christian polities in the Near East is persistently left out of Byzantine history. In addition, the close involvement of Ethiopia with Arabia just before the rise of Islam (at the same time the Axumites were negotiating with Constantinople) offers a completely different vantage point for the role of Eastern Christianity and Byzantium in Islam’s formation. This chapter further questions the definition of Byzantium as coextensive with that of Christianity in the Near East: did Ethiopia only preserve Byzantine traditions because of the unique circumstances of its isolation on the highlands of sub-Saharan Africa? Robin Darling Young explores the early centuries of relations between the newly converted Armenians – crucially at that time under self-rule – and the Byzantine Empire to their west. Most clearly associated with their neighbor and rival Sasanian Persia, the Armenians nevertheless developed a keen sense of affiliation with Byzantium, not least through the centrality of Jerusalem in the shared imaginary of Near Eastern Christians. Kinship, dynastic rule, and Armenia’s role as buffer state between Rome and Persia all contributed to Armenia’s distinctive Christian culture and relationship to Byzantium, which was crucial for the medieval Caucasus in general. Language, exegesis, and translation combined with unique political factors to create an independent Christian kingdom deeply entangled with the greater Byzantine remit. Stephen Rapp’s chapter on Georgia brings Caucasia squarely into the center of the Byzantine Near East, showing how, over the entire Middle Ages, Georgia maintained connections both west and east (Fig. 1.15), with Byzantium and the Persian-Islamic world in equal measure. Nevertheless, models of Georgia as, on the one hand, pro-Western or, on the other, exotic and Eastern cannot account for the complexities of Georgia’s relationships with all the regional powers, including, importantly, Armenia, from the very beginning. This “tangled geo-political web” becomes in many ways the perfect test case for applying global history to the worlds of Byzantium, wherein ethnicity, confession, and political self-definition were always concerns on the periphery of Byzantine control. Many different “commonwealths” overlapped in Byzantine Caucasia.

1.15. East facade, Svetitskhoveli Cathedral, Mtskheta, Georgia, eleventh century.

A handful of sentences on each chapter can hardly do justice to the diverse studies presented in this volume. Each author speaks from a depth of local knowledge but also with the overarching goal in mind of tying Byzantium more firmly to its Near Eastern context. At the same time, the imprint of the Roman Empire on the Near East, even in memory, is indelible. Byzantine authority was linked to emperor and patriarch throughout, and we lose something if we ignore the role played by the Byzantine Empire and the Orthodox Church in Europe and the Near East alike.Footnote 59 That said, the notion of “Byzantium,” in its fullest sense, is a moving target. The Roman legacy is only one part of its role in shaping the Near East, both Christian and not. Highly diverse topics – yeshivot, Egyptian monasteries, liturgical objects, Jerusalem liturgy, Islamic origins – all fall under the purview of Byzantine Studies precisely because they depend, in part, on Byzantine categories for their existence and preservation and, crucially, for their study today.

To repeat the basic conclusion offered proleptically at the beginning of this chapter: the Byzantine Near East was a notional confederation based upon an inherited Christian vision that asserted the perennial idea that God had worked through the Roman Empire to bring about the triumph of Christianity. That said, regardless of how any individual or group might believe the vision was playing itself out or might play itself out in the future, the history of Byzantium was much bigger than the Byzantine Empire. The goal of this chapter has been, at root, to challenge the paradigm of Byzantium as a container. The territorial borders of the Empire are non-determinative for this story, even as they are implicit in the concept of Byzance dehors Byzance. That is, Byzantium, both political and not, continued to mean something to Eastern Christians under Islam, just as it meant something to Islam itself. Our task is to understand with more sophistication, and more sympathy, the wealth of evidence for what amounts to, in the end, much less fragmentation in the Byzantine Near East than has been previously assumed, and much more value for Byzantine Studies as a discipline. Our task is to reintegrate territorial Byzantium with the Near East however possible, with the goal of sustaining and rejuvenating Byzantine Studies, at the same time as we might help redefine it for a new generation.