Introduction

Gout is the most common type of inflammatory arthritis in many developed countries worldwide and is linked with multiple serious comorbidities (Khanna et al., Reference Khanna, Fitzgerald and Khanna2012a,b; Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Grainge and Zhang2015). Prior to the 1980s, gout was regarded as a rare disease in China (Fang et al., Reference Fang, Zeng and Li2006). Alongside, with the rapid development of China’s economy, the prevalence of gout has increased markedly over the past three decades (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Zhang and Zhu2021). Three large cross-sectional studies conducted in coastal areas reported gout rates between 0.15% and 1.14%, with a 5:2 ratio of men to women (Nan et al., Reference Nan, Qiao and Dong2006; Zeng et al., Reference Zeng, Wang and Chen2003; Miao et al., Reference Miao, Li and Chen2008).

Gout is caused by the crystallization of uric acid in the joints. The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines emphasize that the treatment of gout requires both nonpharmacological and pharmacological modalities (Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Fang, Zhang, Sha and Zeng2017). It is recommended that all patients should receive counseling on appropriate lifestyle changes including weight loss, dietary modifications, and reduction of alcohol consumption. Urate-lowing therapy (ULT) is indicated in patients with an overload of uric acid such as tophi, recurrent acute attacks, or arthropathy (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Doherty and Bardin2006). The goal of ULT is to achieve a serum uric acid (sUA) level target of a minimum of 6mg/dL or lower (Khanna et al., Reference Khanna, Khanna and Fitzgerald2012a,b). This strategy is known as “treat-to-target.”

Suboptimal management of gout could be attributed partially to poor patient compliance (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Doherty and Bardin2006; Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Fang, Zhang, Sha and Zeng2017). Patient education could improve disease management (Li et al., Reference Li, Dai and Li2013; Rees et al., Reference Rees, Jenkins and Doherty2013). With the improvement of people’s living conditions and the extension of life expectancy, gout and hyperuricemia have increasingly become common chronic diseases in the daily clinical practice of doctors, not only rheumatologists but also general practitioners and primary care doctors (Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Grainge and Zhang2015). Rheumatologists are generally well-informed (Li et al., Reference Li, Dai and Li2013), but physicians who are not rheumatologists have demonstrated a poor understanding about the management of gout. Several studies have evidenced that general practitioners poorly manage gout (Xiong et al., Reference Xiong, Li and Zhang2019). Less than 50% of patients in these studies were prescribed ULT and only 38% of patients on ULT had their urate levels monitored (Jeyaruban et al., Reference Jeyaruban, Larkins and Soden2015). In China, when the condition of patients with gout worsens, they often consulted rheumatologists or general practitioners who are responsible for patient education.

CME is intended to update the professional knowledge, skills, and performance of medical providers (Bloom, Reference Bloom2005). Appropriate, adequate, and comprehensive CME is becoming increasingly necessary to maintain professional standards and fulfil the licensing requirements of general practitioners (Holm, Reference Holm1998). In the past 2 decades, CME requirements for its 2 million physicians have been implemented in China (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Chen and Srivastava2015). CME is a welcomed step to improving the diagnosis and management of chronic conditions by general practitioners.

Questions that merit investigation are whether general practitioners in China possess an adequate understanding about gout. This study was designed to evaluate general practitioners’ management of gout at community health service clinics in the Tongzhou district of Beijing and identify the factors that contributed to the best medical decisions for patients.

Methods

Subjects

A convenience sampling strategy was used to recruit general practitioners for this study. General practitioners were recruited from ten different community health service clinics in the Tongzhou district of Beijing. And a snowballing recruitment strategy was used, where participants were asked to provide contact details of other general practitioners who might be interested in participating (Noy, Reference Noy2008). Practitioners who were listed as retired or in training were excluded. The Social Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee of Beijing Chaoyang Hospital, Capital Medical University, reviewed and approved this study.

Questionnaire

The self-administered questionnaire was designed to assess clinical knowledge and management of gout in practitioners. Questions were developed from current guidelines for the assessment and management of gout as well as the current European, American, and Chinese gout treatment recommendations (Khanna et al., Reference Khanna, Khanna and Fitzgerald2012a,b; Richette et al., Reference Richette, Doherty and Pascual2017; Chinese Rheumatology Association, 2016). Between September 2018 and June 2019, an online survey was available and participants were sampled. The survey was distributed through WeChat, and data were collected on a platform called ‘Wenjuanwang’.

The structured questionnaire included broad demographic data to maintain anonymity and ten items (Q1–10) related to gout. The demographic data included gender, age, years that the doctors have practiced medicine, professional title, the number of gout patients seen per month, and previous CME on gout. Additionally, the questions examined familiarity with CME lectures or journal articles on gout, as well as awareness of gout quality of care indicators and treatment recommendations. The ten items were divided between knowledge of basic gout concepts (Q1–3) and diagnosis and treatment criteria (Q4–10). Correct responses to the first three questions were used as an indicator that the general practitioners possessed knowledge of basic gout concepts. Correct responses to questions 4 through 10 indicated a solid understanding of gout diagnosis and treatment criteria. The contents of the items were the following: etiology (Q1), gout attack symptoms (Q2), causes of gout attacks (Q3), management of acute attacks (Q4), urate-lowering drugs (Q5), optimal serum uric acid (sUA) levels (Q6), nonpharmacological treatment (Q7), duration of ULT (Q8), the prevention of attacks caused by ULT (Q9), and complications (Q10). The general practitioners needed an average of five minutes to finish the questionnaire. Each item was scored with 1 point for each correct response and 0 for incorrect responses. The participant was defined as having gout-related knowledge if he or she correctly answered seven or more items. Higher scores indicated a greater awareness.

The questionnaire was pre-tested with ten general practitioners and revised according to their feedback. Before sending out the questionnaire online, we invited five experts in rheumatology and five experts in general practice to evaluate the rationality of the content of the questionnaire and revised it according to their suggestions again. Furthermore, we tested the validity of the questionnaire, the reliability of the questionnaire was 0.87, and the retest reliability was 0.91. No personal information was collected from the respondents to assure confidentiality. The administration language was Chinese.

Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 19.0 software. Initial analyses were performed using descriptive statistics. For categorical variables, proportions were calculated. We used χ 2 or Fisher’s exact tests for discrete variables. The demographic characteristics were defined as predictor variables, which were included in the model if P < 0.05 and removed if P > 0.10, in accordance with the forward selection technique. The statistically significant level was 0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

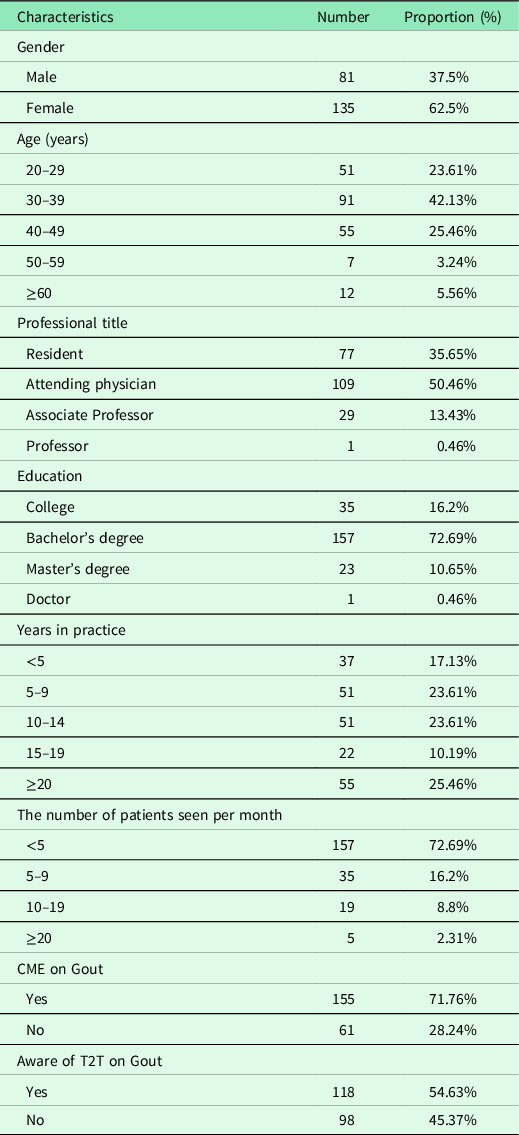

A total of 245 general practitioners from the ten community health service clinics in the Tongzhou district of Beijing agreed to participate. In total, 216 practitioners completed the self- administered questionnaire. The response rate was 88.2%.The demographics and baseline characteristics for the respondents are shown in Table 1. The majority of the participants were female (62.5%) and held a professional title of resident or attending (86.1%). Approximately one-quarter (25.5%) of the general practitioners had been practicing for more than 20 years in a community health service clinic. About three-quarters of the participants (71.8%) indicated that they had received CME about gout. More than half (54.6%) reported a familiarity with gout-related T2T.

Table 1. Basic information of 216 general practitioners

* CME, continuing medication education; T2T, treat-to-target.

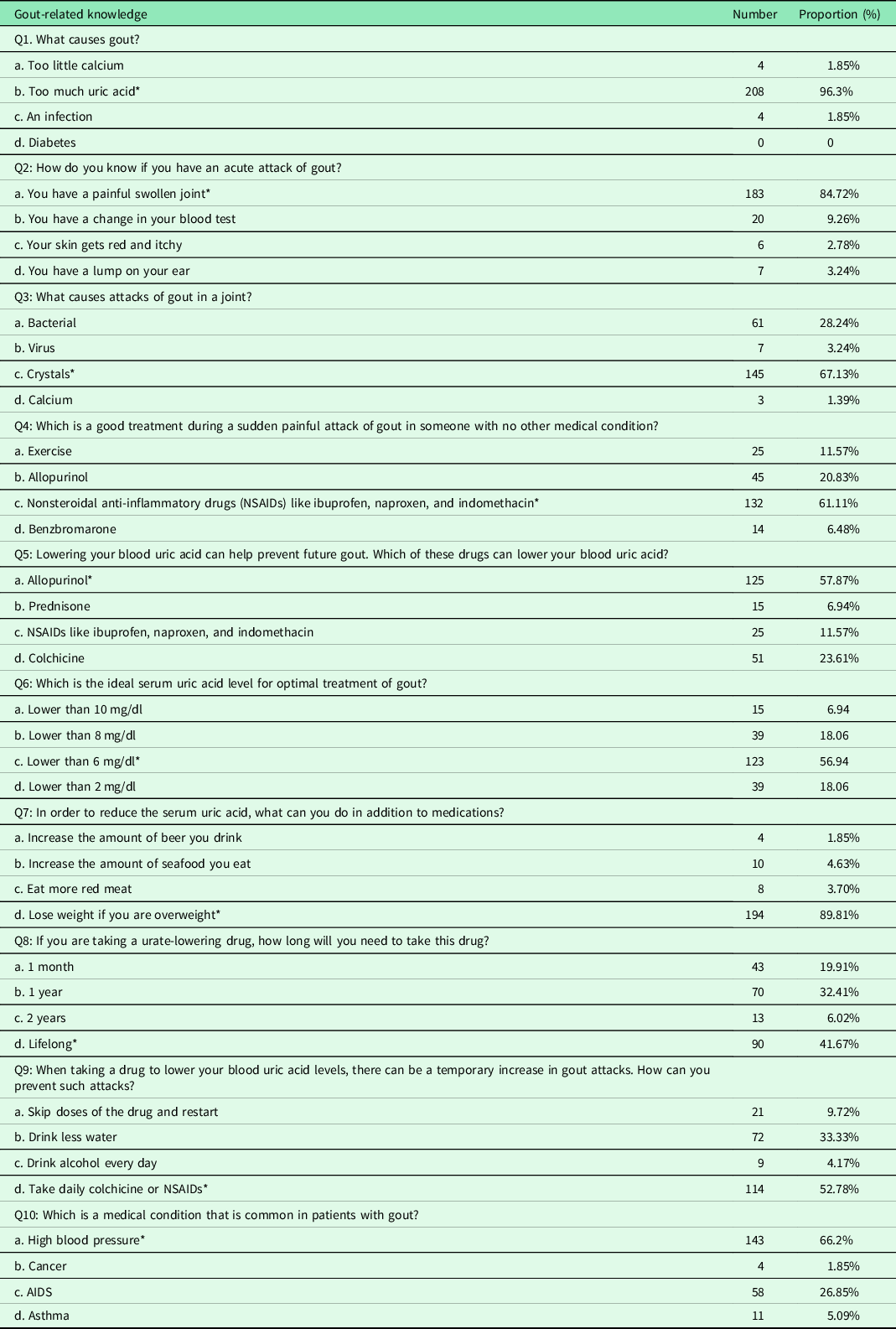

Only 6.5% (14/216) of practitioners demonstrated a good understanding of gout, derived by participants answering all questions correctly. Approximately half (55.6%) of the participants demonstrated a basic knowledge of gout, whereas only 11.1% (24/216) were aware of the criteria for diagnosis. The mean score of correct responses was 7.07 ± 1.89. The responses for each item are illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2. General practitioners understandings of gout

* Correct answer.

The vast majority (96.3%) of the general practitioners chose excessively high levels of uric acid as the cause of gout (Q1). A total of 84.7% noted that painful swollen joints represented an acute symptom of gout (Q2). Two-thirds (67.1%) of the practitioners chose crystals as the cause of gout attacks (Q3).

For the management of an acute attack (Q4), most general practitioners (61.1%) indicated using NSAIDs in patients with no other medical condition as their preferred choice. Exercise was chosen by 11.6% of the general practitioners. 20.8% chose allopurinol, and 6.5% selected benzbromarone as their first line of treatment.

For the management of urate-lowering drugs (Q5), optimal serum uric acid (sUA) levels (Q6), and duration of ULT (Q8), the percentages of correct responses were 57.9%, 56.94%, and 41.7%, respectively. General practitioners were not well informed about the duration of ULT.

Totally, 52.8% of the general practitioners correctly indicated that daily colchicine or NSAIDs would be appropriate for the prevention of attacks induced by ULT (Q9).

A total of 89.8% of the participants responded correctly to the question on non-pharmacological treatment (Q7) and 66.2% responded correctly to the question on complications (Q10).

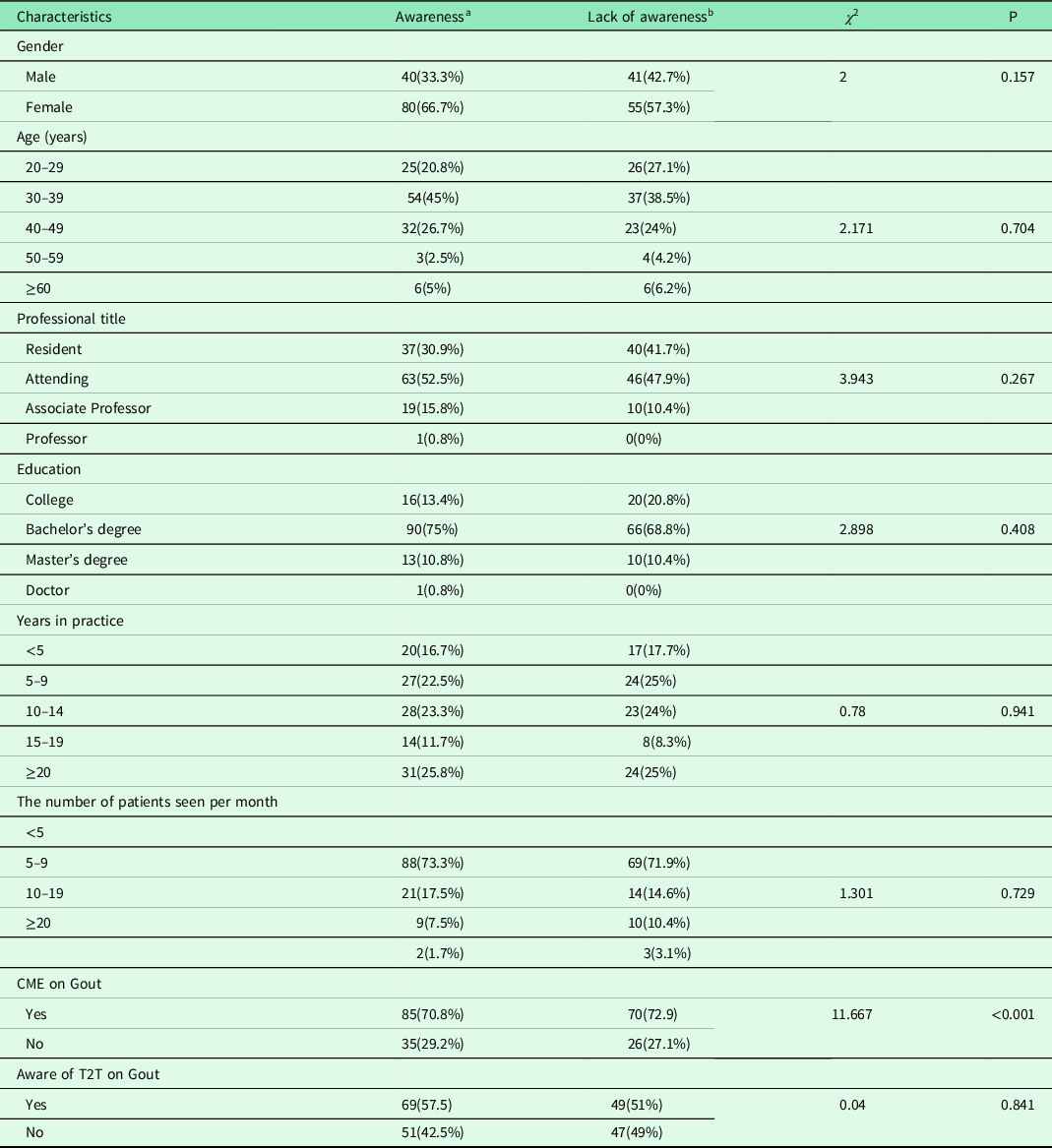

An examination of the general practitioners’ familiarity with gout basic concepts demonstrated that CME could improve their knowledge. Women scored higher than men (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of general practitioners’ awareness rate of gout: basic concepts knowledge

* CME, continuing medication education; T2T, treat-to-target.

a Correct responses to the first three questions(Q1−3).

b The responses to the first three questions(Q1−3) are not entirely correct.

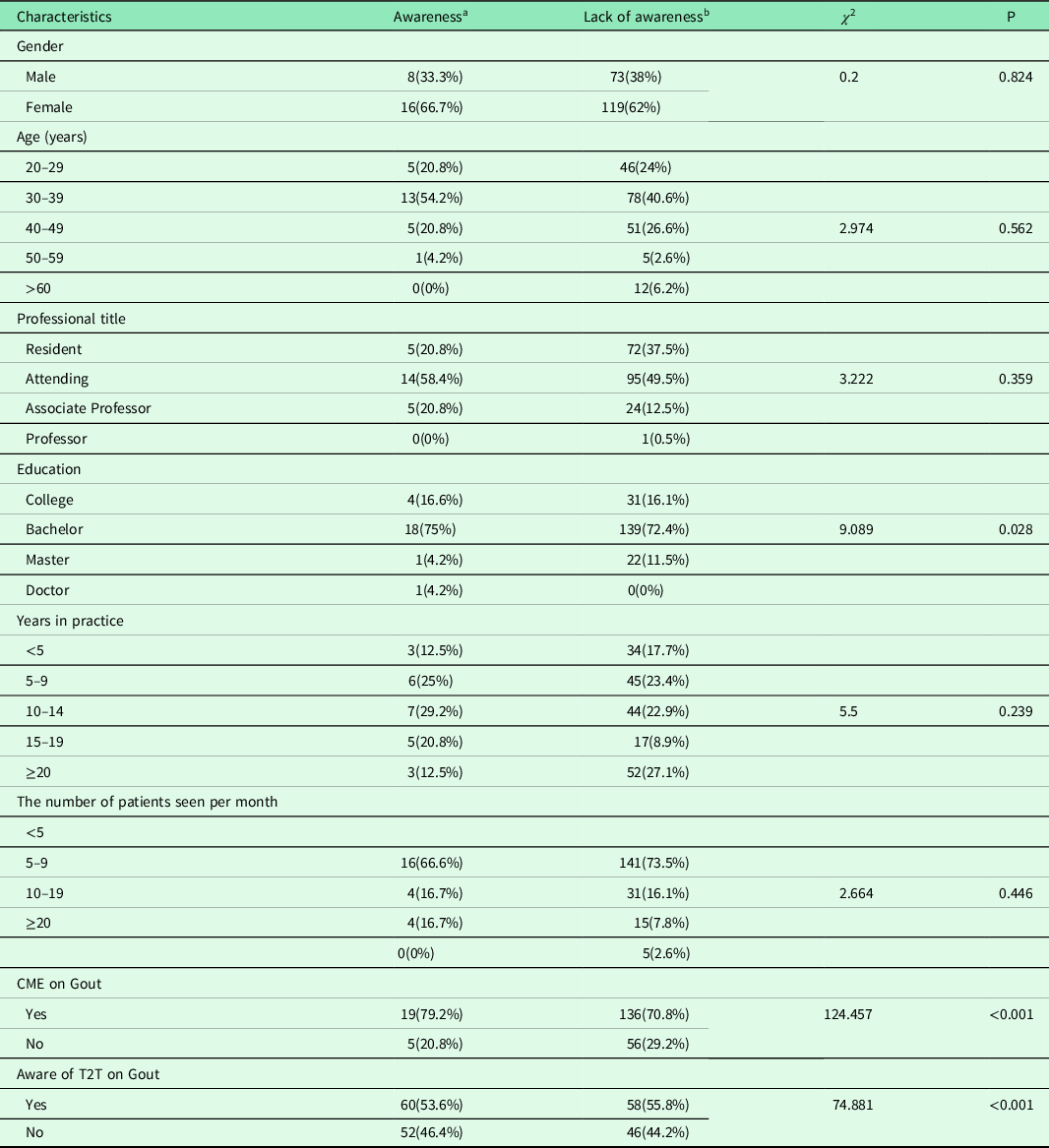

An examination of general practitioners’ understandings of gout diagnosis and treatment indicated that their level of education, experience with CME, and awareness of T2T could improve their knowledge of these areas. Women scored higher than men (Table 4).

Table 4. Comparison of general practitioners’ awareness rate of gout: diagnosis and treatment criteria knowledge

* CME, continuing medication education; T2T, treat-to-target.

a Correct responses to questions 4 through 10.

b The responses to questions 4 through 10 are not entirely correct.

Discussion

With the development of economy and the improvement of medical standard, the living standards of the residents in China have been increasing constantly. The prevalence and morbidity of gout have also been changing (Zhai et al., Reference Zhai, He and Ma2005). Although the incidence of gout has increased, gout has high priority in CME for rheumatology doctors, but not yet for non-rheumatology doctors (Li et al., Reference Li, Dai and Li2013; Ogdie et al., Reference Ogdie, Hoch and Dunham2010). Despite the fact that general practitioners have been in the front lines of the diagnosis and management of the disease, previous studies on gout included low numbers of general practitioner respondents (Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Jansen and Nuki2012). General practitioners’ knowledge of gout had not previously been examined in China (Fang et al., Reference Fang, Zeng and Li2006).To our knowledge, in the Tongzhou district of Beijing, China, our study was the first to examine general practitioners’ knowledge and management of gout in community health service clinics.

Comparison with other studies

In our survey, the overall knowledge of gout among general practitioners was 6.5%, indicating 6.5% participants answered all questions correctly. The overall rate of basic understandings about gout was 55.6%, and the overall rate of knowledge about how to manage gout was only 11.1%. Our findings are consistent with other studies that have indicated that gout has not been optimally managed by general practitioners (Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Healy and Harrison2016).

General practitioners were more knowledgeable about the etiology of gout (96.3%) than about the symptoms of attacks (84.7%) or the causes of those attacks (67.1%). Our findings are consistent with one other study that indicated that acute and chronic gout were not optimally managed by primary care doctors (Spaetgens et al., Reference Spaetgens, Pustjens and Scheepers2016).

A lack of understanding was demonstrated in the responses to the questions related to gout diagnosis and treatment criteria. Although guidelines represented a good starting point to improve the quality of care, doctors did not always adhere to or comply with established recommendations. The survey showed that 57.9% knew about urate-lowering drugs, 56.9% knew the optimal serum uric acid level, and 41.67% correctly believed that patients should remain on ULT for the rest of their lives.

Low levels of understandings about the treatment of gout in general practitioners were almost universal. A previous study demonstrated that only 9.6% of general practitioners in the United States were aware of the guidelines; they adhered to recommended treatment for acute, intercritical, and tophaceous gout in only 47%, 3.4%, and 12.5% of the cases, respectively (Harrold et al., Reference Harrold, Mazor and Negron2013).

Many gout patients have been attended to by general practitioners at community health service clinics. Numerous studies have demonstrated that only 25% to 33% of primary care physicians monitored serum urate levels in patients receiving ULTs (Owens et al., Reference Owens, Whelan and McCarthy2008; Nasser-Ghodsi and Harrold, Reference Nasser-Ghodsi and Harrold2015). Therefore, it would be unlikely that general practitioners treated to a target serum urate level as recommended by the guidelines (Spaetgens et al., Reference Spaetgens, Pustjens and Scheepers2016; Jeyaruban et al., Reference Jeyaruban, Soden and Larkins2016).

Serum urate elevations of >6.8 mg/dL under normal physiologic conditions could lead to monosodium urate crystallization (Rees et al., Reference Rees, Jenkins and Doherty2013). Evidence has suggested that patients who were never on ULT, or on doses that were inappropriately low, would be at a greater risk of flares, tophi, and structural damage, and functional limitations (Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Grainge and Zhang2015). Our survey showed that 56.9% of the practitioners were familiar with the optimal serum uric acid level.

In our survey, education, CME, and awareness of T2T may improve gout diagnosis and treatment. One previous study indicated that patient’s perception of gout was related to patient education (Edwards, Reference Edwards2011). Providing patients with education about gout has shown to enhance medication adherence and self-management, but needs improvement (Fields and Batterman, Reference Fields and Batterman2018).

Study implications

CME is a requirement for practising professionals in many countries including China to maintain medical knowledge and skills (Tang and Ma, Reference Tang and Ma2010). In China, due to the short history of primary care development, the education levels of general practitioner differ (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Zhu and Ong2017). Although China’s general practice education system has been established, there are still a series of problems, such as imperfect personnel training system, low quality of CME, and imbalance of personnel training structure (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Wu and Li2021). Due to the support of national policy and the shortage of general practitioners in China, general practitioners are more likely to obtain professional titles than specialists (Lian et al., Reference Lian, Chen and Yao2019).

Appropriate CME on ULTs and T2T could better prepare and inform general practitioners for the management of gout and leading to better patient outcomes. However, only half of the participants believed there was a need for T2T in gout management, coupled with the evidence that existed of patients’ failure to comply (Neogi and Dalbeth, Reference Neogi and Dalbeth2018; Perez-Ruiz et al., Reference Perez-Ruiz, Moreno-Lledó and Urionagüena2018), represents an area that demands greater attention. Community doctors are in great need of high quality CME.

Limitations and strengths

Certain biases in our study should be noted. The study only included general practitioners; a broader range of health professionals and patients could have provided more comprehensive findings. Furthermore, there were more female than male general practitioners in China; however, the rate of awareness could not be explained by gender differences. The level of community health care clinics is different in Beijing. Because this method of convenience sampling cannot be used in every study, the ability to extend and apply the findings to other settings and populations could be limited. To our knowledge, in the Tongzhou district of Beijing, our study was the first to examine general practitioners’ knowledge and management of gout in community health service clinics.

Conclusion

Our study evaluated general practitioners’ knowledge and management of gout at community health service clinics in the Tongzhou district of Beijing. The results indicated a poor understanding of the diagnosis and treatment of gout. This lack of understanding likely resulted in inadequate clinical decisions. In particular, there was little understanding regarding the duration of ULT. Further education should focus on general practitioners and emphasize the use of urate-lowering drugs, treatment duration, the target sUA level, and prophylaxis against acute attacks. More education is needed to improve the awareness of gout, promote change, and better control and manage gout.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge all the participants for their patience and understanding during the data collection.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guidelines on human experimentation of the ethical of Beijing Chaoyang Hospital, Capital Medical University, and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.