Introduction

The link between opinion and policy has long been considered central to the functioning of representative democracy (e.g., Dahl, Reference Dahl1971; Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1972). ‘Democratic responsiveness’ only exists if public opinion can influence the policy output of governments (Powell, Reference Powell2004). Research on the opinion‐policy link is multifaceted and has made great progress in recent years; however, less is known about the specific mechanisms that inject public preferences on particular policy issues into politics and that eventually lead to policy change (e.g., Elsässer et al., Reference Elsässer, Hense and Schäfer2020; Seeberg, Reference Seeberg2022). This article examines blame games as venues of democratic responsiveness to get a more comprehensive understanding of the opinion‐policy link in policy‐heavy, conflictual democracies. Modern democracies formulate ever more policies to address problems and manage crises, and the political conflict surrounding many of these policies has become more intense (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2019; Orren & Skowronek, Reference Orren and Skowronek2017; Weaver, Reference Weaver2018). I argue that these developments lead to an increase in political blame games about policy controversies, and that blame games represent an important but hitherto neglected venue of democratic responsiveness.

The heart of the argument is that through the media, the public is confronted with a never‐ending succession of (real or constructed) policy controversies that develop into political blame games. As spectators of blame games, citizens form an opinion on whether and how the government should address a controversy. Blame game interactions between the political opposition and the government process public feedback to a controversy. Political institutions, conceptualized as ‘blame channelers’ that help to diffuse blame or to concentrate it in one spot, influence whether the political system is responsive to public opinion during blame games. Governments that are well protected because institutions diffuse blame have little incentive to address controversial policy issues during blame games while governments exposed to concentrated blame pressure are more willing to do so. The study of blame games as venues of democratic responsiveness adds to our understanding of the opinion‐policy link in more conflictual times and provides a new conceptual tool for assessing the health of representative democracies. The analysis suggests that an important, yet neglected, expression of democratic quality of political systems is their ability to translate blame game interactions into policy responses by the government. Democracies that are responsive during blame games should be better able to address their citizens’ concerns in more conflictual times than democracies whose blame games produce only hot air or, worse, contribute to norm erosion and democratic disaffection.

I illustrate my argument with a comparative‐historical analysis (Mahoney & Thelen, Reference Mahoney and Thelen2015) of nine blame games about policy controversies that occurred in the United Kingdom, Germany and Switzerland. For each country, I analyze and compare three blame games that vary in the strength of their public feedback. For each blame game, I examine how institutions influence the interactions between the opposition and the government. Within‐unit and cross‐unit comparisons reveal how institutions configure the opinion‐policy link during blame games. The analysis reveals important differences in the proportionality between the strength of public feedback and a political system's responsiveness during blame games. In the analyzed cases, UK institutions muffle public feedback, Swiss institutions reproduce it and German institutions amplify it. The comparative analysis provides an initial overview of blame games as venues of democratic responsiveness and institutions’ role as ‘blame channelers’. Analysing institutions as blame channelers creates novel insights into democracies’ responsiveness in more conflictual times and casts light on the importance of hitherto neglected institutions, which have thus far not influenced our comparative thinking on the performance and legitimacy of democracy (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012).

The next section reviews the existing literature on democratic responsiveness to argue that blame games constitute an important version of the opinion‐policy link in today's policy‐heavy and conflict‐ridden democracies. The third section conceptualizes political blame games as venues of democratic responsiveness and zooms in on the influence of institutions. The fourth section introduces the research design, and the fifth section presents the empirical analysis. The final sections compare the findings and discuss their implications.

Democratic responsiveness in conflictual times

Democratic responsiveness ‘is what occurs when the democratic process induces the government to form and implement policies that the citizens want’ (Powell, Reference Powell2004, p. 91). A working opinion‐policy link is thus an important indicator of the quality of representative democracy. A great deal of the research on the opinion‐policy link centres on elections as the primary transmission device of citizen preferences (Powell, Reference Powell2004). Citizens aggregate their preferences on a number of policy issues into vote choices, which lead to a selection of policy makers, who, in turn, adopt and implement policies in line with citizens’ preferences (Wlezien & Soroka, Reference Wlezien and Soroka2016).

There is also important research on policy‐specific responsiveness that examines whether and how governments react to public preferences regarding specific policy issues such as abortion or welfare state spending. One way that inter‐election policy adaptation works is through issue politicization. Abou‐Chadi (Reference Abou‐Chadi2016), for example, shows that niche parties that successfully politicize an issue can prompt governing parties to adapt their policy positions. In a related vein, Seeberg (Reference Seeberg2013, Reference Seeberg2022) demonstrates that opposition parties can compel the government to make policy in line with their interests if they manage to prominently put an issue on the political agenda. This line of research suggests that public preferences on a policy issue can lead to policy change if opposition actors somehow manage to ‘inject’ these preferences into politics and put the incumbent government under pressure.

In the following, I will argue that blame games constitute an increasingly important, though largely neglected, mechanism through which democratic political systems (fail to) secure responsiveness to public opinion on specific policy issues. Blame games about policy controversies have become increasingly important in advanced democracies due to three current interrelated developments: policy accumulation, the mediatization of politics and intensified partisan conflict. As governments undertake more over a broader range of issues, policies accumulate (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2019). Increased policy activity automatically implies that a greater number of governmental interventions will not work out as planned, thus triggering controversies. As Bovens and ‘t Hart (Reference Bovens and Hart2016, p. 654) remark, only ‘a part of this myriad of ambitions and activities unfolds as hoped, expected and planned for by policymakers. Another part throws up surprises, complications, delays, disappointments and unintended consequences’.

Many of these policy controversies are likely to be scandalized as media actors report on ‘yet another government blunder’ (King & Crewe, Reference King and Crewe2014). Research shows that the modern media not only acts as a ‘watchdog’ of political developments, it also acts as a ‘scandalization machine’ driven by profit motives (Allern & von Sikorski, Reference Allern and von Sikorski2018). As citizens are presented with a steady stream of mediatized controversies, it is unlikely that they will let all of them ‘float by’ without forming an opinion on whether and how the government should address them.

Mediatized controversies are likely to trigger political conflicts given that political parties are called on to address them. This is even more likely in times where overall political conflict is already intense (Weaver, Reference Weaver2018). Intensified political conflict increases the likelihood that parties will clash on a great variety of issues, even on those where disagreement is actually low and could be solved more peacefully (Lee, Reference Lee2016).

Collectively, these developments suggest that modern democracies experience a great number of policy controversies, many of which are not processed through elections but during political blame games. It is thus necessary to ask whether democracies are responsive to their citizens during blame games. In the next section, I conceptualize blame games as venues of democratic responsiveness to address this question.

Blame games as venues of democratic responsiveness

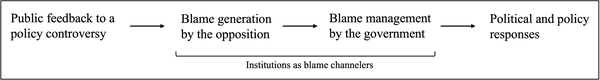

Blame games can be imagined as conflictual – and more or less effective – conversion processes of communicative power into administrative power (Habermas, Reference Habermas1994): Political actors convert public feedback to a policy controversy into blame game interactions, which in turn lead to political and policy responses by the government. By structuring blame game interactions, institutions crucially influence whether these responses are in line with public feedback (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Opinion‐policy Link During Blame Games

Like Hood (Reference Hood2011), I define blame games as a series of interactions between blame makers and blame takers on the occasion of a controversial issue. Blame games are a peculiar subset of political contestation because they revolve around rather obvious failures or scandals that no one seeks to take credit for. I focus on blame games triggered by policy controversies.Footnote 1 Policy controversies may be caused by unanticipated policy developments, complications, delays, disappointments or unintended consequences (Bovens & ‘t Hart, Reference Bovens and Hart2016). Political actors experience them unexpectedly and their occurrence is thus largely exogenous to political competition.

In representative democracies, blame makers and blame takers usually match the political opposition and the government. While organized interests often take the lead in politicizing a controversy, political parties and individual politicians ‘represent’ public interests during blame games. Parties and politicians possess the necessary resources to play a blame game, like access to the media, speaking time in parliament, or the ability to launch inquiries (Hinterleitner & Sager, Reference Hinterleitner and Sager2017).

For the opposition, a blame game about a policy controversy is an occasion to damage the reputation of the government and to win the ‘prize of policy’ (Hacker & Pierson, Reference Hacker and Pierson2014), that is, to force the government to change the underlying policy in accordance with the opposition's and its supporters’ policy goals. Depending on the policy issue at the root of a blame game, these goals can range from minor adjustments to major policy change. In order to reach these goals, the opposition will direct blame at the government by emphasizing (and possibly exaggerating) the supposed damage revealed by the controversy and the government's responsibility for it (Hood, Reference Hood2011; Weaver, Reference Weaver2018). Moreover, the opposition will present its (supporters’) policy goals as representative of public preferences and pressure the government to give in to its demands.

For the government, a policy controversy is a risky affair. The minister that bears responsibility for the policy area in which a controversy occurred will be under intense public scrutiny, and the opposition is likely to blame them no matter what. The government therefore seeks to limit damage by engaging in blame management. It does so by employing a range of presentational blame management strategies (Hood, Reference Hood2011), such as deflecting blame to bureaucratic actors or to previous governments, reframing a controversy as less bad than insinuated by the opposition, and/or exhibiting forms of activism like launching an inquiry or presenting remedies (Sulitzeanu‐Kenan, Reference Sulitzeanu‐Kenan2010). Moreover, government actors (like ministers or top‐level public managers) are usually keen to exhibit a nonverbal attitude during a blame game, which ranges from a self‐confident stance to a humble and committed one (Hansson, Reference Hansson2018).

Blame game interactions between the opposition and the government can produce political and policy responses if the government cannot afford to simply shrug off blame pressure. The spectrum of possible political responses runs from mere (and often only temporary) reputational damage for the government to the resignation of bureaucratic actors or even top‐level politicians. The spectrum of possible policy responses typically ranges from quick fixes and cosmetic changes to major policy change. Blame games may thus represent mere hiccups in the trajectory of policies but may also significantly alter them.

It is important to note that blame games do not occur in a vacuum but play out in front of an audience (Hinterleitner, Reference Hinterleitner2020). Citizens watch them in their role as media consumers. One can imagine citizens performing two stylized roles when confronted with a mediatized controversy. Citizens can either let it float by as if it were just another mass‐mediated event or attentively watch the ensuing blame game and form an opinion about the controversy's severity. Following research on policy feedback and problem construction (Rochefort & Cobb, Reference Rochefort and Cobb1994), it is possible to conceptualize citizens’ responses to a mediatized controversy as a form of public feedback. The strength of public feedback should be determined primarily by the salience and proximity of the controversy (Soss & Schram, Reference Soss and Schram2007). These interpretive characteristics determine citizens’ answers to two crucial questions regarding a controversy. First, do they emotionally care about the controversy because it touches on core values that they hold dear (Brändström & Kuipers, Reference Brändström and Kuipers2003), or are they largely indifferent because the issue is technical, complicated or occurs repeatedly? Second, are citizens directly affected by the controversy (usually financially or through limitations in their daily lives), or only become aware of it through the media? Because salience triggers emotions and proximity triggers considerations of self‐interest (Soss & Schram, Reference Soss and Schram2007), policy controversies that possess these interpretive characteristics should trigger stronger public feedback than non‐salient and/or distant controversies.Footnote 2

While salience and proximity are to a certain extent manipulable, I expect that they also limit (re)framing attempts in important ways. In other words, the opposition and the government try to accentuate or downplay the interpretive characteristics of policy controversies, but they are also constrained by them. For example, opposition actors that intend to scandalize a controversy are unlikely to do so if the public is emotionally indifferent because the issue is technical or recurring. Likewise, the government will have difficulties framing an issue as distant when there are evident direct repercussions for citizens.Footnote 3

The conversion of public feedback into blame pressure and eventually into political and/or policy responses depends on political institutions. Institutions prompt the opposition and the government, understood here as rational, goal‐oriented actors, to employ certain strategies while avoiding others (Parsons, Reference Parsons2007). I conceptualize institutions as blame channelers that either allow the opposition to concentrate blame on the government or diffuse it within the political system. Institutions thereby influence whether and how opponents can hold government actors accountable for a controversy during a blame game, and whether, and to what degree, government actors are responsive to the demands of the opposition. Given these qualities, institutions can be expected to either muffle public feedback, reproduce it or amplify it. I expect that the most important institutional blame channelers are (1) the degree of consolidation of the opposition, (2) institutional conventions of personal responsibility and resignation, and (3) the ‘institutional distance’ between the government and a policy controversy. These three institutional variables capture the idea that both the political context in which blame games play out and the controversy's policy context influence blame game interactions.

First, whether incumbents confront a small or large number of opposition parties during a blame game is relevant. Unlike in two‐party systems, where the government usually confronts one major opposition party during a blame game, the opposition in multiparty systems most likely consists of a larger number of parties. It is easier for a small number of parties to coordinate their blame attacks and forge a coherent narrative about a controversy than for a larger number of parties to do so. I expect that a consolidated opposition can better transform public feedback into a coherent blame generation approach and put the government under pressure more than an unconsolidated opposition. Likewise, it should be harder for governments to remain unresponsive when they face a consolidated opposition than when they face an unconsolidated one.

Second, democracies contain more or less extensive conventions of accountability that determine the events government actors have to take (personal) responsibility for and, crucially, which they are expected to resign for (Hinterleitner & Sager, Reference Hinterleitner and Sager2015). I assume that extensive conventions of responsibility and resignation aid the opposition in transforming public feedback into personalized blame while restricted conventions exacerbate the personalization of a blame game ‘at the top’. Accordingly, governments that have to comply with extensive conventions should be more responsive during blame games than governments facing restricted conventions.

Third, driven by New Public Management reforms, a large variety of public and private actors currently carry out policy tasks, many of which operate ‘at arm's length’ from the government (Mortensen, Reference Mortensen2016). Complex governance structures have centrifugal blame diffusing qualities that make it harder for the opposition to assign political responsibility for policy controversies (Bache et al., Reference Bache, Bartle, Flinders and Marsden2015). I expect that the more institutional distance there is between a controversy and the government, the harder it will be for opponents to effectively transform public feedback into blame pressure directed at the government and the easier it will be for the government to remain unresponsive to the demands of the opposition.

Overall, I expect that systems whose institutions diffuse blame are less democratically responsive during blame games than systems whose institutions concentrate blame at the top. The reason is that blame‐diffusing institutions make it harder for opponents to make the government receptive to public feedback. In the following sections, I illustrate my argument through a comparative‐historical analysis of nine blame games in the United Kingdom, Germany and Switzerland.

Data and method

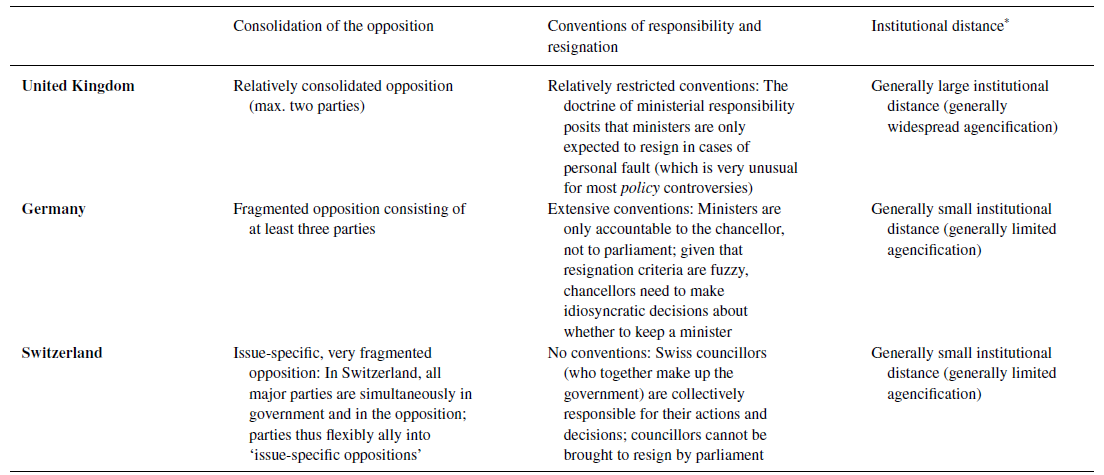

I chose cases based on the independent variables (strength of public feedback, configuration of institutions). The nine blame games (cases) selected for analysis occurred within three political systems (units) between 1999 and 2014. I selected the United Kingdom, Germany and Switzerland because their relevant institutional dimensions vary greatly (see Table 1 for a systematic overview). Moreover, examining cases situated in three countries allows for comparative insights into the proportionality between the strength of public feedback and the government's response, that is, whether political systems muffle, reproduce or amplify public feedback. Within each political system, I analyzed three blame games about policy controversies with weak, moderate and strong public feedback (which correspond to blame games triggered by distant‐non‐salient, proximate‐non‐salient and distant‐salient controversies).Footnote 4

Table 1. Institutional blame channelers in the United Kingdom, German and Swiss political systems

* Given that institutional distance is primarily a policy area‐specific factor, the empirical analysis will assess it on a case‐by‐case basis. Nevertheless, tendencies can be observed at the system level due to country‐specific reform trajectories in recent decades.

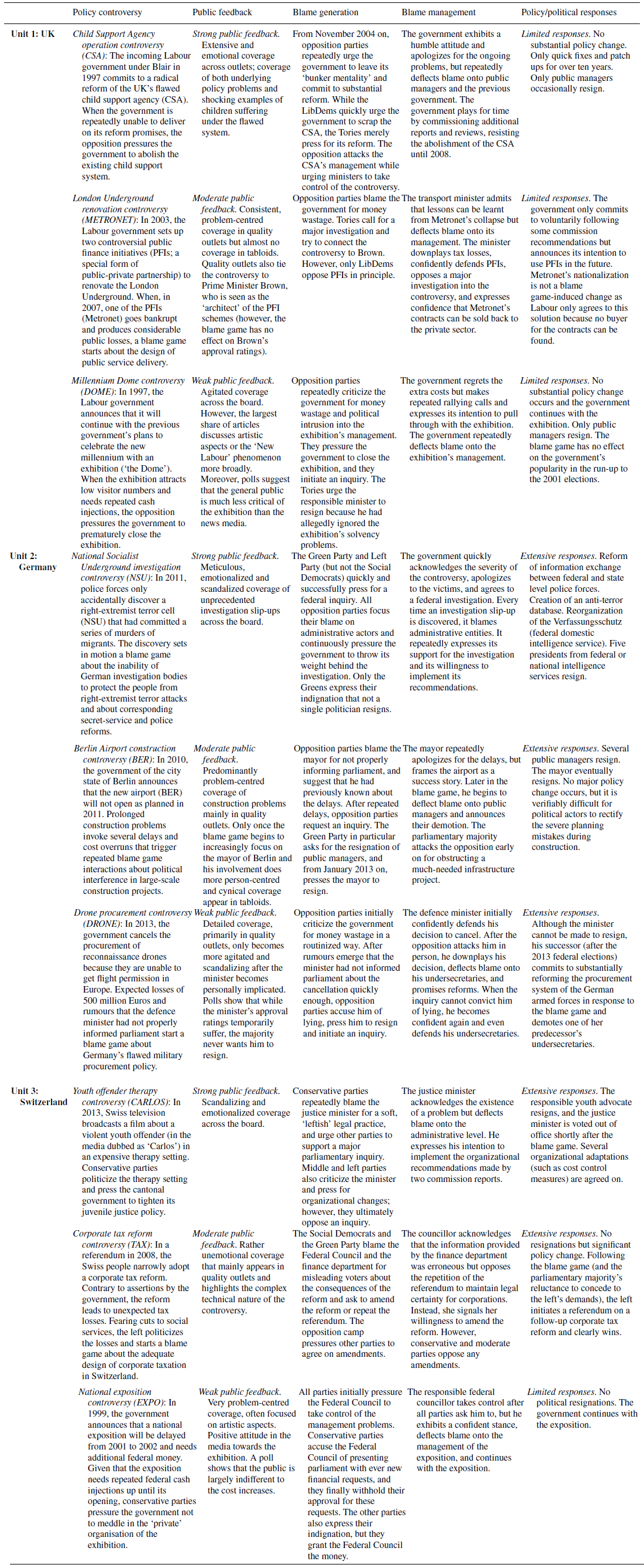

I conducted a comparative‐historical analysis (CHA) of the nine blame games and their consequences (Mahoney & Thelen, Reference Mahoney and Thelen2015). CHA has two distinct advantages for the analysis and systematic comparison of complex phenomena like blame games, which often span considerable time periods and consist of several rounds of interactions between the opposition and the government. First, CHA allows one to identify how institutions determine the broad contours of blame game interactions while controlling for unique aspects of single cases. Second, CHA provides the deep case knowledge necessary to reliably measure and compare key concepts (such as political/policy responses) across often very idiosyncratic cases.Footnote 5 An unavoidable shortcoming of such a multi‐case approach is that ‘the explication of theory comes at the expense of descriptively rich case narratives’ (Moynihan, Reference Moynihan2009, 900). To mediate this problem, Table 2 presents concise case summaries that focus on the concepts of interest (strength of public feedback, blame generation approach of the opposition, blame management approach by the government, political/policy responses). Moreover, Supporting Information Part C contains explanations and illustrations of comparative statements (marked as Supporting Information Appendix Annotations (OAAs) in the subsequent section) to provide readers with additional case details.

Table 2. Overview of the nine blame games

Due to their public nature, blame games leave a ‘paper trail’ that mainly consists of newspaper articles, transcripts of parliamentary debates, and inquiry reports (see Supporting Information Part A for a description of the data categories and their primary uses). I used NVivo 11Footnote 6 to obtain detailed case knowledge and to systematically measure the concepts of interest (see Supporting Information Part A for detailed information on the measurements). This software allows for the extraction of information from large quantities of text, and arranges it in research‐specific ‘nodes’ (that match the concepts of interest presented in Table 2). The coding process combines inductive and deductive elements of analysis. An unavoidable side effect of this approach is that inferences obtained through the systematic analysis of large amounts of textual information cannot easily be traced back to individual primary sources (Moynihan, Reference Moynihan2009). To enhance the evaluation of the findings of the CHA, Part B of the Supporting Information lists key sources for each blame game. Key sources allow readers to efficiently reconstruct and critique the empirical analysis.

Empirical analysis

This section presents detailed analyses on how institutions configure the opinion‐policy link during blame games in the United Kingdom, Germany and Switzerland.

Blame games in the United Kingdom

A striking commonality across the three UK blame games is that they only led to negligible policy and political responses by the government. Even during the blame game about the CSA controversy, where public feedback was strong and emotional, the government could afford to stay passive for many years and only apply quick fixes to the flawed child support system. This commonality occurs because institutions in the United Kingdom make it very difficult for the opposition to concentrate blame ‘at the top’.

How UK institutions influence blame generation

Although the United Kingdom hosts the most consolidated opposition among the analyzed countries, the cases reveal that only two parties that focus on different issues during a blame game can already lead to incoherent attacks on the government. In the cases analyzed, Tories and Liberal Democrats did not usually consolidate their blame attacks, focusing instead on different policy goals (OAA1). Moreover, in the three cases, the much smaller Liberal Democrats were very vocal and managed to ‘punch above their weight’, as evident by their frequent statements in the media. This suggests that unlike routine times when the number of seats largely determines a party's influence, smaller opposition parties can also play a prominent and distinct role during a blame game due to the media's interest in poignant statements.

Another commonality across the three cases is that the opposition heavily focused its blame attacks on administrative actors like public managers (OAA2). Blame attacks directed at responsible ministers were much less frequent. The opposition only called for the resignation of ministers during the blame game about the DOME controversy, where the opposition accused the responsible minister of covering up the financial performance of the exhibition. Several institutional factors account for the opposition's focus on the administrative level. First, the doctrine of ministerial responsibility, which states that ministers are only expected to resign in cases of personal wrongdoings, makes ministers unpromising blame targets for the opposition. Since policy controversies cannot usually be tied to the actions of a single minister, personalized attacks have a low chance of implicating top‐level politicians. Second, frequent ministerial reshufflings, which can be observed in all three cases, reinforce this dynamic (OAA3). Given that most policy controversies take time to unfold, the politicians originally responsible for them are often no longer in office, making it unlikely that sitting ministers can be personally implicated.

Third, the institutional distance between a policy controversy and top‐level politicians exacerbates the opposition's attempts to generate blame directed at the government. Both the CSA and the METRONET controversies occurred ‘at arm's length’ from the government, with the effect that the media focused its coverage on administrative faults rather than on policy design aspects for which politicians would be more directly responsible. Finally, inquiry commissions and the reports they produce usually focus on controversial occurrences and implementation issues rather than criticizing and questioning a policy itself (OAA4). When the opposition uses the work of inquiry commissions as an informational basis for its blame attacks, administrative actors automatically come into sharper focus than responsible ministers. Taken together, these institutional characteristics of the UK system explain why it is exceedingly difficult for the opposition to put heavy and personalized blame pressure on top‐level government actors.

How UK institutions influence blame management

Institutions thus create a comfortable situation for the government. The opposition's focus on different policy goals creates room for the government to stick to its own policy goals because there is no clear policy alternative on the table. Moreover, the opposition's and the media's focus on administrative actors and their wrongdoings imply less personalized blame for ministers, allowing them to portray themselves as committed but confident crisis managers in charge of an administrative problem. Frequent ministerial reshufflings also allow the government to buy time during a blame game by appointing a new minister to oversee the management of a controversy. Incoming ministers usually enjoy a ‘honeymoon period’ during which they are granted the time to acquaint themselves with a controversy, often by commissioning ‘yet another report’ (OAA5).

Against this background, it is not surprising that ministers’ incentives to respond to the demands of the opposition and address a complex policy controversy (like fixing the CSA) or enact comprehensive policy change (like refraining from using PFIs) remain low. The blame generated by the opposition cannot easily change ministers’ inclinations to kick a controversy into the long grass and ride out the blame game surrounding it. This interpretation seems to apply to both blame games with strong public feedback (CSA) and to blame games where incumbents face more personalized attacks (DOME), and ultimately explains why the UK political system is unresponsive during blame games.

Blame games in Germany

In stark contrast to the UK cases, the three German blame games led to considerable policy and/or political responses by the government, even when public feedback was weak (DRONE) or moderate (BER). As a comparison of the three cases suggests, institutions in the German political system are conducive to producing very heated, often person‐centred, blame games during which governments come under considerable pressure to address a controversy.

How German institutions influence blame generation

Even more than in the UK political system, an unconsolidated opposition exacerbates the generation of blame pressure. In the cases analyzed, the opposition parties usually focused on different policy goals and blamed the government for different aspects of a controversy and to varying degrees (OAA6). Nevertheless, extensive conventions of resignation give the opposition the opportunity to put the government under direct pressure. In the German system, the reasons for ministerial resignations are not nearly as clearly defined as in the United Kingdom and calls for resignation can accordingly be made for a large variety of controversial issues and actions. This helps to explain the frequent claims for resignations in the DRONE and BER cases (OAA7). Extensive conventions of resignation allow the opposition to quickly personalize a blame game at the top and force responsible ministers into heated blame game interactions. Inquiry commissions help the opposition to voice convincing claims for resignation. In Germany, unlike in the United Kingdom, these commissions can be relatively easily appointed by opposition parties. In the three cases analyzed, the opposition parties quickly requested inquiries into the respective controversies (OAA8). An inquiry into a controversy allows the opposition to keep a blame game on the political agenda. Moreover, an inquiry promises the retrieval of additional information about a minister's personal involvement and thus may create a basis for requests for resignations. These considerations are particularly relevant in the DRONE case where the opposition explicitly pondered whether an inquiry would reveal additional insights into what (and when) the minister had known about the procurement problems.

How German institutions influence blame management

In Germany, the opposition's incoherent blame generation approach and often diverging policy goals play into the hands of the government, allowing it to stick to its policy goals and granting it with the flexibility to address the opposition's accusations (OAA9). Moreover, and unlike in the United Kingdom, where members of the government party sometimes joined the opposition in its criticism of the government, the parliamentary majority in Germany vocally supported the implicated ministers when necessary. An active and vocal parliamentary majority provides ministers with distinct advantages. In the BER and DRONE cases, it allowed them to (at least initially) duck away and stall for time to get an overview of the controversy. During this time, the parliamentary majority had already started to refute the opposition's allegations and reminded it of its prior involvement in the controversy.

While the option to appoint an inquiry commission is an opportunity for the opposition to drag a blame game on and to implicate top‐level politicians, the cases also suggest that doing so comes at a cost. An inquiry commission channels a blame game into a different, often more slow‐moving, arena where opponents have to comply with specific rules. This allows the government to avoid playing the blame game during parliamentary debates. In the BER and DRONE cases, the government explicitly reminded the opposition that it had to wait with its allegations until unequivocal results were in and to not judge before the trial (OAA10).

Nevertheless, the evidence suggests that governments quickly come under considerable pressure if the opposition can make credible claims of personal wrongdoings (OAA11). It thus seems that institutional distance is an important mediating factor that influences whether a German blame game takes on a heated and person‐centred dynamic. We can observe such a dynamic in the DRONE and BER cases where the government's involvement was evident from the beginning, while in the NSU case, considerable institutional distance coincided with a much less aggressive and personalized blame game.

Overall, governments in the German political system are much more responsive to blame pressure than their UK counterparts. Even in cases where feedback is weak (DRONE) or moderate (BER), the German system yields considerable policy and/or political responses during blame games. This is primarily because of the relative ease with which the opposition can personalize a blame game at the top and thereby force the government into heated blame game interactions. Strong blame pressure forces incumbents to adopt an active stance during a blame game and take a controversy seriously. The responsiveness of the German political system during blame games is reinforced by a look at the NSU case where strong feedback resulted in significant policy responses even in the absence of personalized pressure on ministers.

Blame games in Switzerland

The three Swiss blame games led to political and policy responses that are comparatively most in line with the strength of public feedback. While the blame games about the CARLOS and TAX controversies, which were accompanied by strong and moderate public feedback, led to significant policy responses, the blame game about the EXPO controversy, which was accompanied by weak feedback, did not lead to any notable responses. The institutional characteristics of the Swiss political system produce very distinct, party‐centred blame game interactions that explain this pattern.

How Swiss institutions influence blame generation

The most notable aspect of the blame generation attempts by ‘opposition’ parties in the three blame games is that they are much more focused on other political parties than on the collective executive government (OAA12). In fact, blame games in the Swiss political system exhibit a basic configuration that is very different from the blame game interactions between the opposition and the government in the UK and German political systems. In the Swiss system, the collective executive government (the Federal Council), which consists of seven councillors in charge of their respective departments, represents all major parties. On the occasion of a controversy, one or more parties form an ‘opposition camp’ that pressures the Federal Council to respond to the controversy in a specific way. The opposition camp usually confronts one or more parties that rigorously oppose policy change and one or more middle parties that (at least initially) are undecided about which actions to take regarding a controversy (OAA13). Because the government represents all major parties, its legitimacy during a blame game rests on its responsiveness to as many parties as possible. A ‘pressure majority’ in parliament thus sharply increases the opposition camp's chances of having the government adapt policy according to its interests, even though its consolidation is usually fragile because its members do not necessarily focus on the same issue(s). This peculiar constellation explains why the opposition camp in the three cases primarily tried to pressure other parties to go along with its policy demands rather than directly attacking the federal councillors.

However, federal councillors are also unattractive blame targets in themselves because they are collectively responsible for their decisions and there are no conventions of responsibility and resignation. This implies that, unlike in the German and UK political systems, where political, or at least administrative resignations are within the opposition's reach, the opposition camp in the Swiss system has little incentive to personalize a blame game. This dynamic is only slightly different at the cantonal level where personalized attacks are more promising because cantonal councillors are directly elected by the population and not by parliament. This brings political responses within reach of the opposition camp (OAA14).

How Swiss institutions influence blame management

The opposition's focus on other parties and its comparative neglect of the executive create a comfortable position for federal councillors. They can largely keep out of blame game interactions between parties and act as committed and neutral crisis managers that wait until parties have argued out how to address a controversy before becoming responsive to the parliamentary majority. For example, in the blame game about the TAX controversy, the responsible councillor repeatedly told parliament that she would be willing to amend the reform if parties demanded to do so (OAA15). Given this absence of direct pressure, institutional distance between a controversy and the government does not seem to be a decisive factor.

Overall, the very peculiar, party‐centred form of Swiss blame games reveals a specific pattern of democratic responsiveness. If the opposition camp successfully forms a parliamentary majority for policy change, the government faces considerable pressure to be responsive. Given that public feedback increases the prospect of forming such a majority, it is clear why the strength of public feedback and the policy response by the government are more congruent in the Swiss system than in the UK or German systems.

Discussion

The empirical analysis reveals important commonalities but also interesting differences across the nine cases and three countries. The tendency shows that the stronger the feedback to a controversy, the higher the likelihood that blame game interactions result in policy and/or political responses by the government. This finding is in line with election‐centred research on the opinion‐policy link, which shows that politicians are more responsive to salient policy issues than non‐salient ones (Wlezien & Soroka, Reference Wlezien and Soroka2016). However, the analysis also reveals that institutions define the concrete relationship between the strength of public feedback to a controversy and the extent and type of responses by the government. The UK, German and Swiss political systems structure blame game interactions in distinct ways. Their institutions influence the goals that the opposition can realistically pursue during blame games and how difficult it is to achieve them.

The United Kingdom's political system exhibits blame‐diffusing institutions that protect responsible ministers from blame and make it exceedingly difficult to personalize a blame game ‘at the top’. Consequently, the opposition is unlikely to achieve its policy goals or provoke political resignations. The UK political system even muffles strong public feedback and is thus unresponsive during blame games. The German political system features a different blame game dynamic. The relative ease with which the opposition can put ministers under blame pressure explains why it has good chances of achieving its policy goals and provoking political resignations. The German political system even amplifies weak public feedback and is thus very responsive during blame games. The Swiss political system exhibits yet another blame game dynamic. Given that political resignations (especially at the federal level) are beyond the reach of the opposition camp, it concentrates its efforts on forging a parliamentary majority for policy change. Since the odds of forging a majority increase with the strength of public feedback, the relationship between feedback strength and policy responses is the most congruent in comparison with the UK and German systems. The Swiss system reproduces public feedback and is thus responsive during blame games.

Importantly, it is the combination of institutional factors that configures a country's specific blame game style and its democratic responsiveness. Within these combinations, most institutional factors channel blame game interactions as expected, but their relative importance varies from country to country. For example, the consolidation of the opposition generally seems to be less decisive than conventions of responsibility and resignation. Likewise, institutional distance helps to explain the government's policy response in the United Kingdom, while its influence in Germany is limited, and it is almost absent in Switzerland. Moreover, the analysis identified additional institutional characteristics that configure each country's blame game style, such as frequent ministerial reshufflings in the United Kingdom and the relative ease with which the opposition in Germany can appoint an inquiry commission.

The cross‐country analysis suggests that there are important differences in the proportionality between the strength of public feedback and a political system's responsiveness during blame games. Political systems can ignore public feedback during blame games or respond to it. They can also ‘overshoot’ their response to public feedback in cases where citizens do not see the need for policy responses or altogether oppose them. However, while the three institutional aspects considered in the analysis allow to explain the extent and type of the government's response (political and/or policy‐centred), the government's concrete attempts to address the underlying policy issues should depend on additional factors. For example, even a government that intends to address a policy problem exposed by a blame game may struggle to do so if it has a limited policy capacity (Peters, Reference Peters2015) or if it is under high fiscal pressure (Elsässer & Haffert, Reference Elsässer and Haffert2021). Likewise, the quality of the policy response might also depend on a country's ‘policy style’, that is, its typical way of addressing problems through policy interventions (Richardson, Reference Richardson2014). For example, some countries may include a variety of actors in the development of the policy response, while the policy response in other countries may be more ‘top‐down’. Moreover, it should also make a difference whether the opposition presses for radical policy change or for minor, primarily symbolic adjustments. Governments determined not to lose the ‘prize of policy’ (Hacker & Pierson, Reference Hacker and Pierson2014) during a blame game should be more willing to accommodate minor adjustments than radical change.

In any case, the institutions that configure the blame game styles identified above are not the ‘usual suspects’ at the centre of institutionalist research on democracy (Bernauer & Vatter, Reference Bernauer and Vatter2019; Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012). Conventions of accountability and resignation, the outsourcing of governing activities, or the modalities of appointing an inquiry do not form part of the traditional ‘patterns of democracy’ that structure our comparative thinking and that are often used to explain differences in the performance and legitimacy of democracy. Accordingly, this study suggests that research on democratic responsiveness in more conflictual times should study institutions from a distinct and novel perspective and examine how they channel, diffuse and concentrate blame within a political system.

These findings stem from the comparative analysis of nine cases in three countries. More research is evidently needed to gain a deeper understanding of the blame game styles of advanced democracies. I only examined the broad contours of blame game interactions and did not engage in causal process tracing, which may reveal other (institutional) factors that influence blame game interactions in important ways. Moreover, while the three cases per country were selected with the intention of covering the majority of blame games that occur in democracies on a regular basis, blame games are highly complex and infinitely idiosyncratic, leaving open the possibility that other blame games may exhibit dynamics not studied here. The analysis presented above therefore provides an initial overview of blame games as venues of democratic responsiveness rather than a definitive, causal account of the mechanisms connecting public feedback to blame game consequences.

Conclusion

This article reveals novel insights into the opinion‐policy link in conflictual, policy‐heavy democracies. Blame games about policy controversies can be venues of democratic responsiveness if they convert public feedback into policy and political responses by the government. The comparative analysis of nine blame games in the United Kingdom, Germany and Switzerland suggests that the proportionality of this conversion process depends on institutions. Institutions can muffle, reproduce or even amplify public feedback, leading to political and/or policy responses that are more or less in line with what the public wants during blame games.

This finding not only demonstrates the analytical gains that can be had from studying institutions as ‘blame channelers’; it also has important implications for our understanding of democratic responsiveness in more conflictual times. Blame games allow citizens to observe a political system's typical way of ‘bargaining and arguing’ (Elster, Reference Elster, Malnes and Underdal1991) under the burning glass. Observing a certain blame game style on a regular basis may thus influence citizens’ opinions in important ways. For example, citizens who frequently watch blame games that involve a lot of norm bending might get used to it and expect a rougher governing style from politicians in the future. Moreover, and especially in political systems that are unresponsive during blame games, watching blame games could exacerbate citizens’ resignation and democratic disaffection, as they learn that their government is unable or unwilling to address issues they care about. Blame game styles may thus be important determinants of citizens’ resentment of democratic institutions and political elites (Hay, Reference Hay2007; Norris, Reference Norris2011). On a more optimistic note, blame games may also lead to a learning effect among citizens. During blame games, citizens can learn about and form preferences on very specific issues (such as corporate taxation or unmanned warfare), which might influence their stance on related issues or even have an impact on their future voting behaviour.

In sum, while this study is an early step along the way to a more comprehensive understanding of the opinion‐policy link in conflictual, policy‐heavy democracies, its findings, and the implications that result therefrom, indicate that this is a potentially fruitful way forward for future research. I thus propose using the study of blame games as venues of democratic responsiveness as a new conceptual tool for assessing the health of representative democracies in conflictual times. Democracies that manage to address their citizens’ concerns when politics get rough should be better equipped for more conflictual times than democracies that only offer bread and circuses on the occasion of policy controversies.

Acknowledgements

I thank Fritz Sager and the three anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments and suggestions.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supplementary information