Introduction

Pegmatites at Wiperaminga Hill, Boolcoomatta Reserve, Olary Province, South Australia, Australia were exploited for feldspar, beryl and muscovite between 1957 and 1980 (Olliver and Steveson, Reference Olliver and B.G1982). Four pegmatites were worked in two operations, Wiperaminga Hill West and Wiperaminga Hill East. Phosphate minerals were first identified from Wiperaminga Hill by King (Reference King1954) who reported dufrénite and florencite and later Hiern (Reference M.N1966) reported apatite, triplite, dickinsonite, and barbosalite. The eastern-most pegmatite at Wiperaminga Hill West contains large masses of triplite–zwieselite and hydrothermal alteration has led to the development of a suite of secondary, microcrystalline phosphate minerals. Recent studies of specimens collected in the 1980s and in 2017 have identified 20 additional phosphate minerals including the new species jahnsite-(NaMnMn) (Elliott and Kampf, Reference Elliott and A.R2023b), plumboperloffite (Elliott and Kampf, Reference Elliott and A.R2024) and the subject of this paper, wiperamingaite. The new mineral and its name have been approved by the Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification of the IMA (IMA2023-023, Elliott and Kampf, Reference Elliott and A.R2023a). The name is for the locality. The holotype specimen is housed in the mineralogical collection of the South Australian Museum, Adelaide, South Australia (registration number G35314).

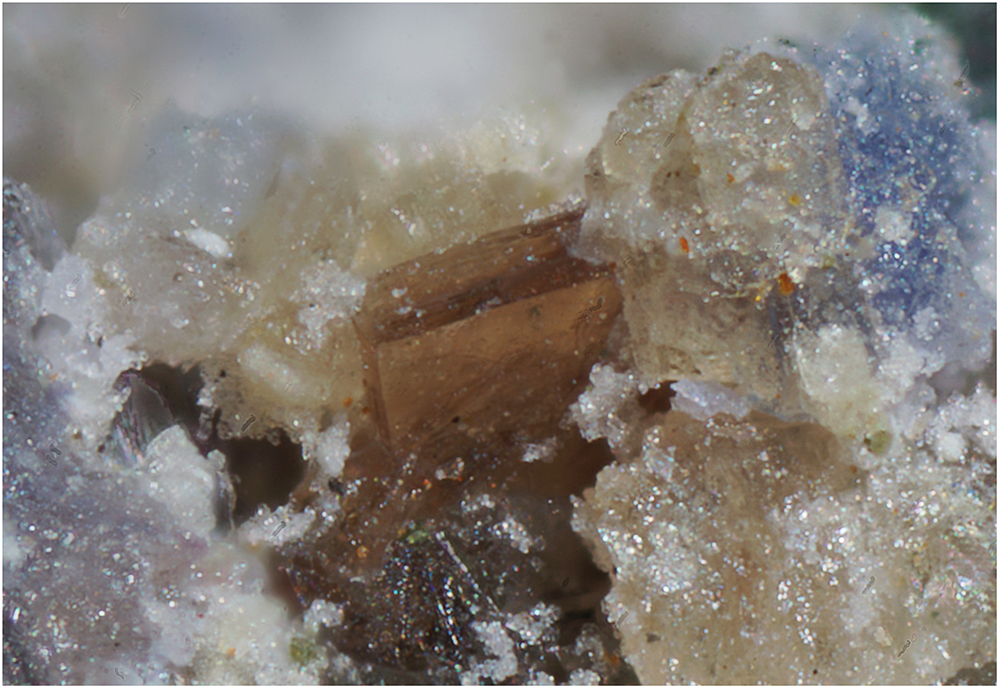

Figure 1. Crystal of wiperamingaite, 0.25 mm across, associated with fluorite (white), leucophosphite (pink) and phosphosiderite (blue) (specimen in private collection).

Occurrence

More than 70 pegmatite bodies are known to occur in the Olary Province of South Australia (Lottermoser and Lu, Reference Lottermoser and Lu1997). The pegmatites are usually small lenticular bodies varying from 6 to 30 m in length and from 1 to 3 m in width (Hiern, Reference M.N1966) and have intruded into Early Middle Proterozoic age Willyama Complex rocks. The Willyama Supergroup consists of upper-greenschist to amphibolite-grade metamorphosed sedimentary and minor igneous rocks interpreted to have formed in an intracontinental rift setting. The sequence is dominated by clastic and chemical sediments, including evaporites and exhalites (Cook and Ashley, Reference N.D.J and P.M1992). The pegmatites at Wiperaminga Hill occur near the base of a prominent range of hills, which comprise banded quartz-mica gneiss and schists. The pegmatites are mineralogically zoned and comprise an outer border zone of fine- to medium-grained microcline, quartz, plagioclase and muscovite, an intermediate zone of coarse-grained muscovite, quartz, microcline, plagioclase, beryl and apatite (and triplite), and an inner quartz core or cores (Lottermoser and Lu, Reference Lottermoser and Lu1997). The Wiperaminga Hill pegmatites belong to the beryl–columbite phosphate-rare-element type in the classification of Černý (Reference Černý1991). Triplite–zwieselite, formed by metasomatic alteration of magmatic fluorapatite, has been transformed by hydrothermal alteration and weathering, in an oxidising, low-temperature, low-pH environment, to give a complex, microcrystalline intergrowth of secondary phosphate minerals (Lottermoser and Lu, Reference Lottermoser and Lu1997). Besides secondary phosphates, the triplite–zwieselite also contains minor columbite-(Fe), pyrite, sphalerite, chalcopyrite and galena.

Appearance and physical properties

Wiperamingaite forms individual tabular crystals to 0.25 mm across (Fig. 1). The colour is brownish-orange to brownish pink and the streak is white. Crystals are transparent and the lustre is vitreous. A cleavage on {001} is expected based on the structure. The fracture is splintery and the tenacity is brittle. Fluorescence under ultraviolet illumination is not observed. The density was not measured because of the scarcity of available material. Based on the empirical formula and the unit-cell volume obtained from single-crystal data, the density of wiperamingaite is calculated to be 3.11 g/cm3. Optically, wiperamingaite is biaxial (–) with α = 1.538(2), β = 1.599(2), γ = 1.614(2) (white light), 2V = 52(2)° (measured directly on a spindle stage) and 2V (calc.) = 51.1°. The dispersion is r > v, distinct. The optical orientation is X = a, Y = b, Z = c and pleochroism is X colourless, Y brown yellow, Z yellow; Y > Z > X. The compatibility index, 1 – (KP/KC), is 0.03 (excellent) based upon the empirical formula, density calculated using the single-crystal cell, and the measured indices of refraction (Mandarino, Reference J.A1981).

Chemical composition

Chemical analyses of wiperamingaite (12) were performed using a Cameca SXFive electron microprobe operated in wavelength dispersive mode at 15 kV and 20 nA with a 5 μm beam diameter. The data were corrected for matrix effects with a φ(ρZ) algorithm (Armstrong, Reference J.T and Newbury1988). As insufficient material is available for the direct determination of H2O, it has been calculated based on the results of the structure refinement and is confirmed by IR spectroscopy. Analytical data are given in Table 1. The empirical formula calculated on the basis of 11 anions per formula unit, with OH calculated to maintain charge balance is Na0.97Ca1.01Fe3+0.92Al1.11(PO4)0.97F4.85(OH)1.32·0.95H2O. The ideal formula is NaCaFe3+Al(PO4)F5(OH)·H2O, which requires Na2O 8.36, CaO 15.12, Fe2O3 21.53, Al2O3 13.74, P2O5 19.13, F 25.61 H2O 7.29, –O=F –10.78, total 100 wt.%.

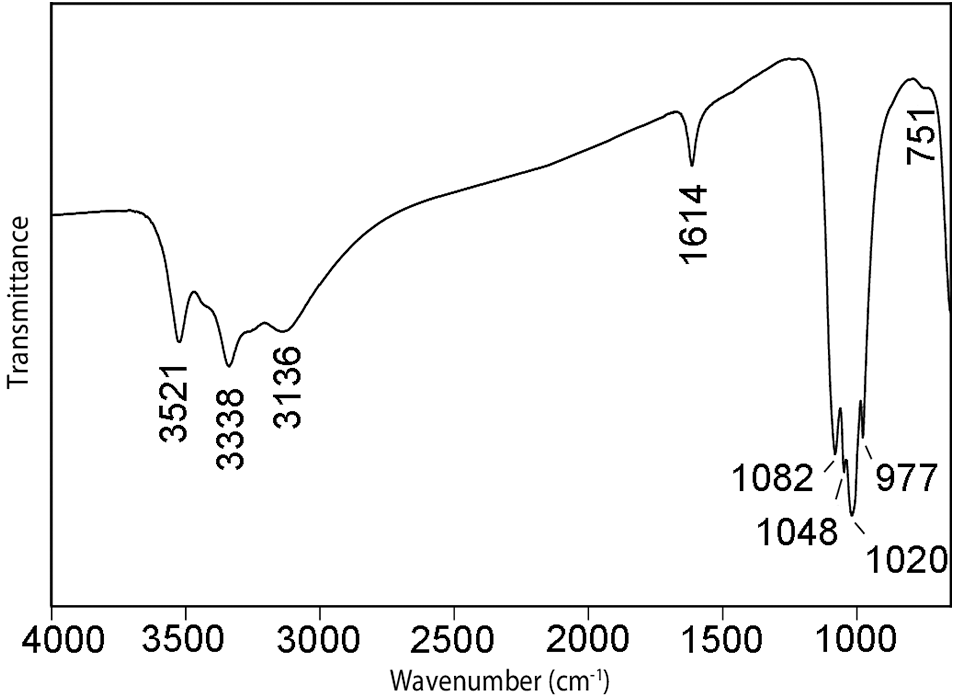

Table 1. Compositional data for wiperamingaite

* Based on the structure with O+F = 11. S.D. – standard deviation

Infrared spectroscopy

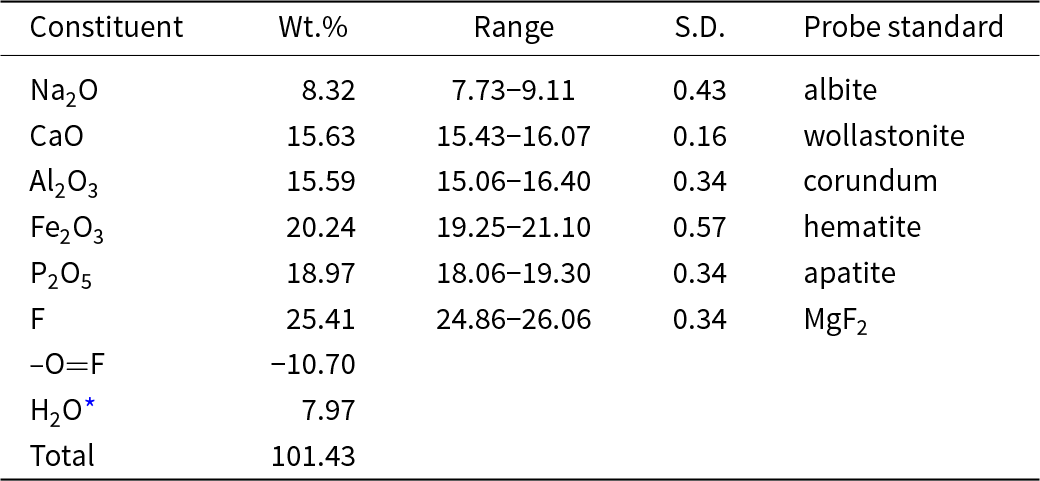

The infrared spectrum of wiperamingaite (Fig. 2) was recorded using a Nicolet 5700 FTIR spectrometer equipped with a Nicolet Continuμm IR microscope and a diamond-anvil cell. Data were acquired from a powdered sample during 50 scans in the wavenumber range 4000 to 700 cm–1. The spectrum shows bands at 3521, 3338 and 3136 cm–1 that correspond to O–H-stretching vibrations of OH and H2O groups forming weak hydrogen bonds (Libowitzky, Reference Libowitzky1999). The band at 1614 cm–1 is assigned to H–O–H bending vibrations of H2O molecules. Bands at 1082, 1048, 1020 and 977 cm–1 are assigned to υ3 antisymmetric stretching vibrations of PO4 tetrahedra and the band at 751 cm–1 to the υ1 vibration of PO4 tetrahedra (Farmer, Reference V.C1974; Frost et al. Reference Frost, Martens, Williams and Kloprogge2002; Hatert, Reference Hatert2008).

Figure 2. The Fourier-transform infrared spectrum of powdered wiperamingaite.

Crystallography

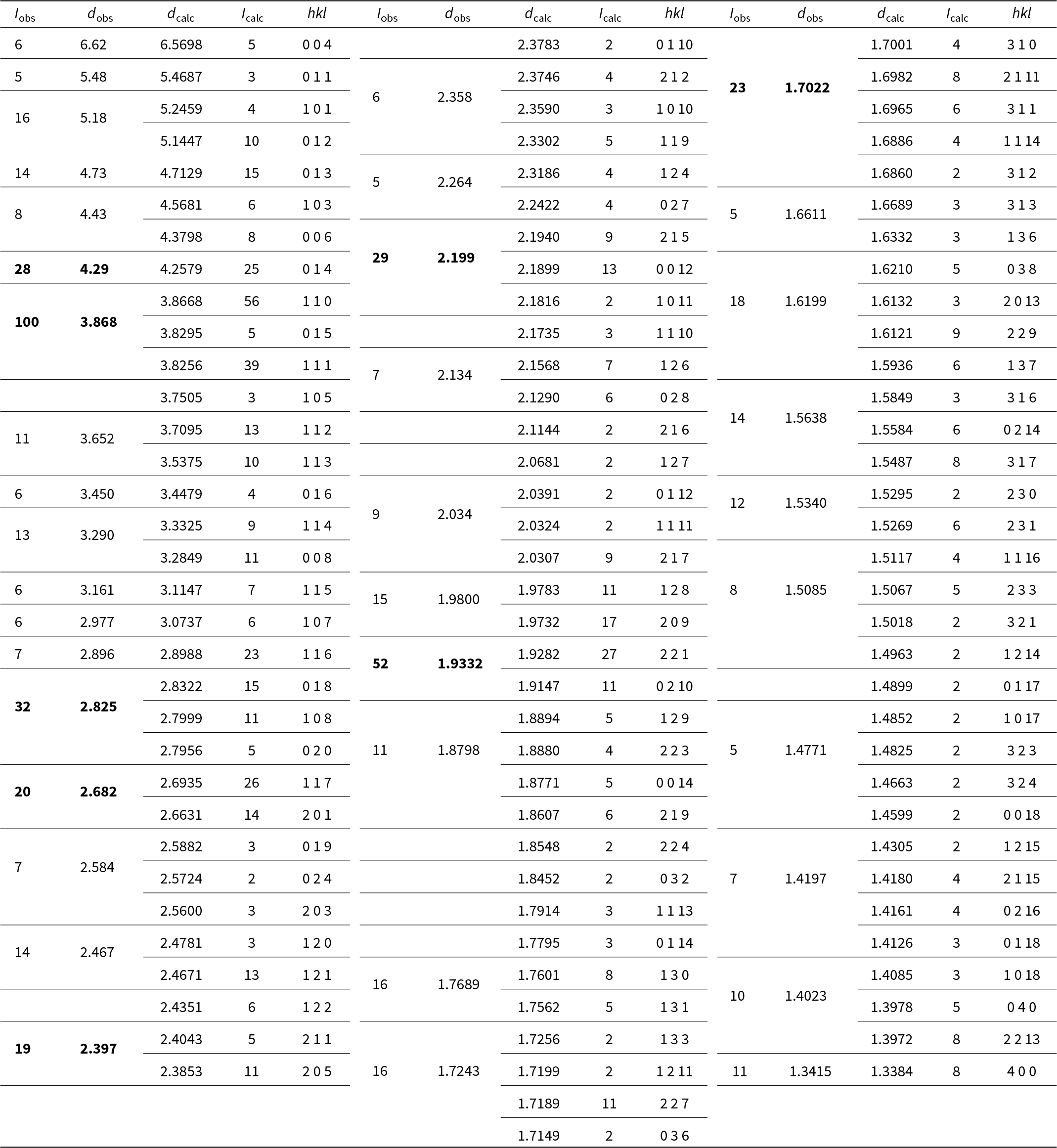

Powder X-ray diffraction data for wiperamingaite were obtained using a Rigaku R-AXIS Rapid II curved-imaging-plate microdiffractometer, with monochromatised MoKα radiation (50 kV, 40 mA). A Gandolfi-like motion on the φ and ω axes was used to randomise the sample. Observed d values and intensities were derived by profile fitting using JADE Pro software (Materials Data, Inc.). Data (in Å for MoKα) are given in Table 2. Unit-cell parameters refined from the powder data using JADE Pro with whole-pattern fitting are a = 5.391(4), b = 5.632(4), c = 26.449(17) Å, V = 803.1(9) Å3 and Z = 4.

Table 2. Powder X-ray data for wiperamingaite. The calculated intensities have been normalised so that the three reflections contributing to the largest observed peak have a combined intensity of 100. Only calculated reflections with normalised intensities of 1.5 or greater are listed

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data were collected with an Oxford Diffraction Xcalibur diffractometer equipped with an Eos CCD detector. Data were processed using CrysAlisPro (Rigaku Oxford Diffraction, 2018) and the measured intensities were corrected for Lorentz, background, polarisation and absorption effects. The reflection statistics and systematic absences were found to be consistent with space group P212121. A structure solution was obtained using SHELXT (Sheldrick, Reference G.M2015a) and the structure was refined using SHELXL-2018 (Sheldrick, Reference G.M2015b) as implemented in the WinGX suite (Farrugia, Reference L.J1999). Wiperamingaite was refined as an inversion twin, with the two twin domains present in a 0.48:0.52 ratio. The final R 1 was 8.33% for 1508 observed reflections with I > 2σI. The relatively high R factor is attributed to the twinning. Attempts to refine all atoms anisotropically resulted in non-positive definite displacement parameters for five of the six O atoms, so these were refined isotropically. Attempts were made to refine the structure in the subgroups and supergroups of P212121. This was only successful in the non-centrosymmetric space group P21 but did not improve the results in of P212121, with a similar number of atoms with non-positive definite displacement parameters and R 1 = 9.47%. Details regarding the data collection and refinement are given in Table 3. Final atom coordinates, isotropic displacement parameters, and occupancies are listed in Table 4, selected interatomic distances are given in Table 5, and bond-valence values, calculated using the parameters of Gagné and Hawthorne (Reference Gagné and F.C2015) for cation–oxygen pairs and from Brown and Altermatt (Reference Brown and Altermatt1985) for cation–fluorine pairs, are given in Table 6. The crystallographic information files have been deposited with the Principal Editor of Mineralogical Magazine and are available as Supplementary material (see below).

Table 3. Crystal data, data collection and refinement details

† wR2 = Σw(|Fo|2–|Fc|2)2/Σw|Fo|2)1/2; w = 1/[σ2(Fo2) + (0.0581 P)2 + 32.6592 P]; P = ([max of (0 or F 02)] + 2Fc2)/ 3

Table 4. Atom coordinates, occupancy factors and equivalent-isotropic or isotropic (*) displacement parameters (in Å2) for wiperamingaite

Table 5. Selected interatomic distances (Å) and possible hydrogen bonds (Å) for wiperamingaite

Refined site-scattering values (Table 4) are compatible with ordering of Na and Ca into two distinct sites which is also strongly supported by the bond-valence analysis (Table 6). The Na site is coordinated by 12 F atoms with Na–F distances in the range 2.334 to 3.065 Å (mean 2.675 Å). The Ca site is coordinated by five F atoms and three O atoms with Ca–O distances in the range 2.241 to 2.567 Å (mean 2.386 Å). Bond distances and refined site-scattering show that the octahedrally-coordinated cations are also ordered into distinct sites. The Al site has almost regular octahedral coordination, whereas the Fe site shows greater angular distortion (O–Fe–O angles range from 76.2 to 106.2°).

Table 6. Bond-valence (in vu) analysis for wiperamingaite

Notes: Bond-valence parameters used are from Gagné and Hawthorne (Reference Gagné and F.C2015) for cation–oxygen pairs and from Brown and Altermatt (Reference Brown and Altermatt1985) for cation–fluorine pairs. The bond-valence sum for the Fe site is based on an occupancy of Fe0.92,Al0.08.

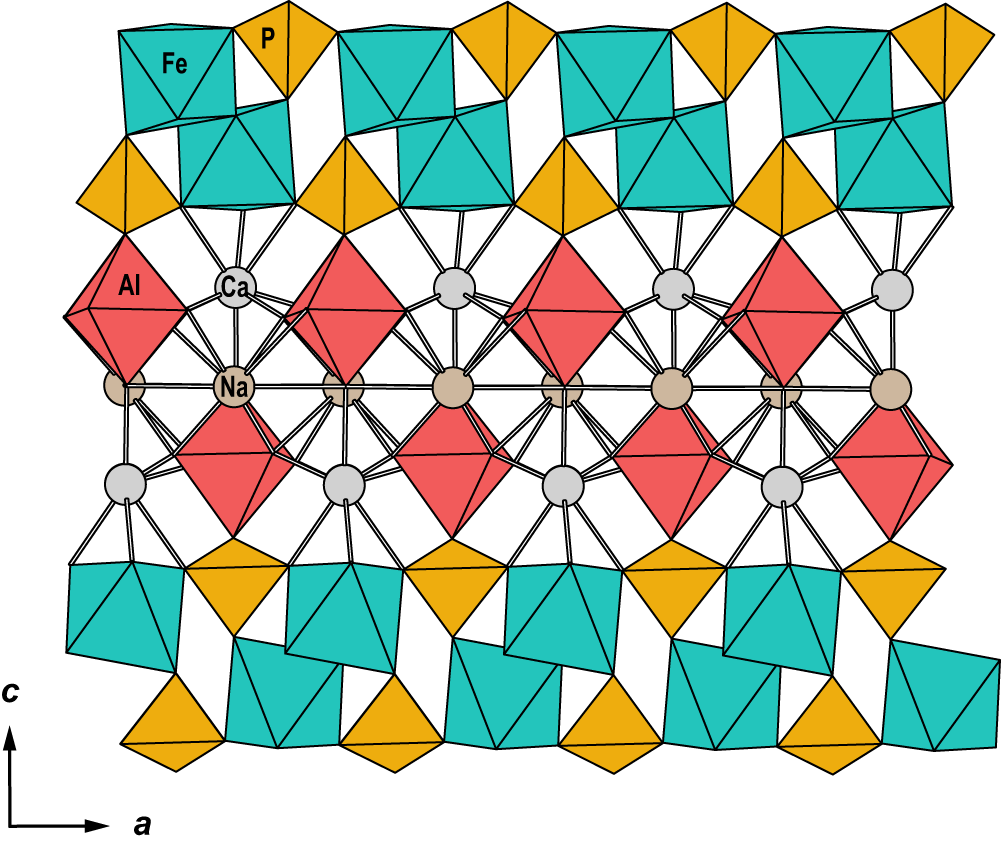

The structure of wiperamingaite is based on kinked chains of cis-corner-connected Feφ6 octahedra (φ = O, OH and H2O) that are running parallel to [010]. Chains are linked along [100] via corner-sharing with PO4 tetrahedra to form sheets parallel to (001) (Fig. 3). Alφ6 octahedra (φ = O and F) are attached to both sides of the sheets via corner-sharing with PO4 tetrahedra. Sheets are flanked on either side by Ca polyhedra, which share faces with Fe octahedra and corners with Al octahedra and P tetrahedra. Two Ca layers link via face-sharing with Na polyhedra (Fig. 4).

Figure 3. The sheet of Fe[O3,H2O,(OH)2] octahedra and PO4 tetrahedra in the crystal structure of wiperamingaite. All structure drawings were completed using ATOMS (Dowty, Reference Dowty1999).

Figure 4. The crystal structure of wiperamingaite viewed along [010].

The structure contains one OH group and one H2O molecule. Although the H atoms could not be located during the refinement, there are four possible hydrogen bonds as summarised in Table 5. Under this scheme, OH5 provides a hydrogen bond to O1 and OW6 provides hydrogen bonds to O2, F2 and F4.

Corner-sharing octahedral–tetrahedral sheets are the basic structural unit of many phosphate minerals. Wiperamingaite is the first phosphate mineral structure with sheets that contain cis-corner-connected octahedral chains. Structures of the laueite-supergroup minerals (Mills and Grey, Reference Mills and I.E2015) contain laueite-type heteropolyhedral sheets (Moore,Reference P.B1975) comprising kinked chains of trans-corner-connected octahedra that run along [001] with adjacent chains linking along [100] by corner connection with XO4 tetrahedra (X = P5+ or As5+) to form sheets parallel to (010). Stewartite (Moore and Araki, Reference Moore and Araki1974) and kastningite (Adiwidjaja et al., Reference Adiwidjaja, Friese, Klaska and Schlüter1999) contain sheets that are geometric isomers of the laueite-type sheets and differ in the orientation of the PO4 groups (Moore, Reference P.B1970, Reference P.B1975; Krivovichev, Reference S.V2004). Pseudolaueite (Baur, Reference W.H1969), metavauxite (Baur and Rama Rao, Reference Baur and Rama Rao1967) and strunzite (Fanfani et al., Reference Fanfani, Tomassini, Zanazzi and Zanzari1978) contain sheets that are topological isomers of the laueite-type sheets that have different connectivity between the octahedra and tetrahedra.

Minerals of the calcioferrite group (Grey et al., Reference Grey, Kampf, Smith, Williams and MacRae2019) and vauxite (Baur and Rama Rao, Reference Baur and Rama Rao1968) have a layer structure based on zig-zag chains of corner-connected octahedra in which the shared corners are alternately in cis and trans configuration that are linked along [010] via corner-sharing with PO4 tetrahedra.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1180/mgm.2025.10102.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ben Wade for assistance with the microprobe analysis. We acknowledge the instruments and expertise of Microscopy Australia (ROR: 042mm0k03) at Adelaide Microscopy, University of Adelaide, enabled by NCRIS, university, and state government support. The infrared spectrum was acquired with the assistance of the Forensic Science Centre, Adelaide.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.