Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused an unparalleled and prolonged economic recession in Latin America. In 2020, the level of activity contracted by 6.8 per cent, as reported by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), and by 7 per cent according to estimates from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). ECLAC has characterised this as the greatest economic crisis the entire region has faced since the early twentieth century, when statistical records began. For example, during the so-called ‘debt crisis’ in 1983, the GDP of the region contracted by 2.6 per cent, while the fall due to international financial turbulence in 2009 was 1.8 per cent. Additionally, the drop in aggregate production in the region in 2020 exceeded declines recorded in other regions, more than doubling the worldwide decline of 3.2 per cent and surpassing even the fall in the Eurozone economies (6.5 per cent). This economic downturn occurred despite the positive impact of public policies to support labour and household incomes implemented across most Latin American economies.Footnote 1

Before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the region was already experiencing a period of economic slowdown together with a reversal of the improvements seen in the labour market performance in preceding years. At the same time, a high incidence of labour informality, low average incomes, significant wage gaps, and weaknesses in social protection continued to be the most prominent structural characteristics of the region. It is therefore not surprising that, notwithstanding the implementation of a wide spectrum of response policies, the economic collapse had a disproportionate impact on certain population groups, exacerbating the region's already high levels of inequality.

While economic recovery began in the second half of 2020, with regional GDP growing by an average of 6.2 per cent in 2021, this rebound did not sufficiently improve labour indicators. In particular, two years into the pandemic, in the fourth quarter of 2021 regional employment and economic participation rates were still below 2019 levels, while the unemployment rate remained higher.Footnote 2

The pattern of a partial recovery to 2019 employment levels observed at the regional level is reflected in nearly all the countries analysed in this paper, except for Argentina. Moreover, the informality rate either remained the same or increased in 2021 compared to 2019, except in Argentina and Uruguay. The evolution of total family incomes was even less promising, as none of these countries have returned to pre-pandemic levels. However, it is worth noting that, in most of these countries, income inequality did not exceed that of 2019.

The main aim of this paper is to assess the distributive impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on different income sources and on total family incomes in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Peru and Uruguay. In particular, the study emphasises the behaviour of informal employment and labour incomes derived from informality, highlighting their close association with the evolution of total labour incomes and their distribution during the period under analysis. The distributive effects of cash transfer programmes implemented during the pandemic are also assessed.

While there is empirical evidence on the impact of COVID-19 on the labour market, incomes and inequality in Latin America, this paper makes several new contributions in this regard. Firstly, to our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the evolution of income distribution until the end of 2021, two years from the onset of the pandemic. Secondly, by using data from six countries – which collectively account for more than 50 per cent of the total population in the region – this study offers a comprehensive understanding of the impacts of COVID-19 in Latin America. Thirdly, unlike some previous studies, this paper evaluates the actual distributive changes without resorting to assumptions or simulations. Finally, this study pays particular attention to the evolution of labour informality and its impacts on inequality, taking into account the atypical behaviour of informal employment during this crisis.

The selection of countries is based, on the one hand, on the availability of comparable data throughout the period analysed, in light of the fact that some countries in the region discontinued household surveys during the most critical period of the pandemic. On the other hand, we aimed to include countries with different labour and distributive structures and policy responses to the pandemic. For example, by the end of 2019, the share of informal employment ranged from 25 per cent in Uruguay to 71 per cent in Peru. Similar disparities were seen in household income inequality, with Gini coefficients of 0.411 in Uruguay and 0.548 in Brazil. Finally, these countries also varied in their policy responses during the pandemic: while some adapted existing mechanisms to better support formal workers, others introduced temporary measures to help firms avoid layoffs. Additionally, although most countries implemented some form of cash transfers, coverage and adequacy also differed widely between them.

The paper proceeds as follows. The next section contains a review of the literature; the subsequent section details our sources of information and the measurement of labour informality. Following that, a brief overview of the magnitude and extent of the economic and labour crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic in the region is provided. Subsequently, the heterogenous impacts of the initial massive loss of jobs and the successive partial employment recovery are analysed. The following section details policies supporting employment and family incomes, especially for those households living in informality. Then, the paper examines the behaviour of total household income inequality and assesses the contribution of different income sources. The final section offers conclusions.

Existing Evidence on the Immediate Distributive Impacts of the Pandemic

The significant progress witnessed by Latin America regarding income distribution from the early 2000s began to slow down by the beginning of the 2010s and came to a complete halt with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote 3 The policies implemented to address the health crisis, in particular lockdown and social-distancing measures, had a profound impact on economic activity and employment, as previously noted, subsequently affecting labour and household incomes.

There is evidence – estimating expected impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic using, generally, microsimulation methodologies – of generalised reductions in aggregate labour incomes in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Mexico,Footnote 4 and also in Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru.Footnote 5

Previous studies also support the view that these expected reductions in aggregate incomes would be accompanied by increasing inequality, as is the case with the above-mentioned contributions. Significant increases in the Gini coefficient were reported in Argentina (2.6 points), Brazil (0.8 points), Colombia (1.2 points) and Mexico (1.5 points).Footnote 6 The most pronounced negative impact of this crisis was concentrated among individuals and households placed in the middle of the income distribution, rather than among the poorest. Similarly, a potential shrinking of the middle class is found in Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru. For these countries, an increase in the poverty rate, from 26 per cent before the pandemic to 29.3 per cent during the first months of the crisis, was also projected.Footnote 7 A potential negative influence on income distribution was also estimated for Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Mexico and Panama,Footnote 8 where the incomes of the low-income middle class (referred to as the ‘vulnerable middle class’) and of the first percentiles of the ‘non-vulnerable middle class’ would have been the most affected by the crisis. This evolution would mean an increase in income inequality. Another contribution also found a potential increase in poverty and labour income inequality in most Latin American countries due to social distancing measures.Footnote 9

There is also evidence suggesting that cash transfer programmes may have mitigated income losses and the rise in income inequality, though the impact varied across countries due to differences in coverage and benefit amounts. These programmes fully offset the decline in labour income in Brazil. Social assistance schemes, though to a lesser extent, were also significant in mitigating the increase in the Gini coefficient in Argentina and Colombia.Footnote 10 An analysis of ten Latin American countries estimated that more than 75 per cent of households of the first tercile received cash transfers. In the case of Brazil and Peru, this percentage was even higher, ranging between 98 per cent and 100 per cent, but it was substantially lower in Uruguay and Chile (52 per cent and 35 per cent, respectively). The estimated value of cash transfers as a proportion of monthly labour income during the pandemic varied between less than 25 per cent and more than 50 per cent in the most vulnerable households, depending on the country under consideration.Footnote 11

Increasing income inequality has been also shown in the few studies that have evaluated the actual distributive impacts of the pandemic. They found that negative trends in the labour market and disruption of education and training programmes were the main channels through which COVID-19 exacerbated pre-existing inequalities in some Latin American and Caribbean countries. Women, low-skilled individuals and young people suffered the most pronounced fall in labour participation.Footnote 12 In a larger sample of countries, an average increase in inequality of 2 per cent between 2019 and 2020 – with notable variations across gender, urban and rural areas, and sectors of activity – was estimated. Minor impacts on remittances were found and, conversely, a significant effect of public cash transfers in partially offsetting the negative distributive impacts of the pandemic on labour incomes.Footnote 13

Finally, it was found that the recovery phase (from the second to the third quarters of 2020) was unequal, both within and between the countries of the region. However, although the employment recovery was uneven and partial compared to for the most affected groups – such as women, younger individuals, urban workers and those without university education – it contributed to a reduction in the incidence of food insecurity from 13 per cent to 9 per cent of the population.Footnote 14

This paper contributes to the analysis of the distributive influence of the pandemic by estimating the actual (not potential) behaviour of income distribution in six Latin American countries. Moreover, unlike existing studies, it considers a broader period of analysis, extending until the end of 2021. Therefore, it covers both the contractionary phase and the recovery phase, which began by mid-2020. The study evaluates the role of different income sources in a more disaggregated manner by differentiating the effect of the evolution of formal and informal employment, as well as studying the role of cash transfers.

Data and Measurement of Informality

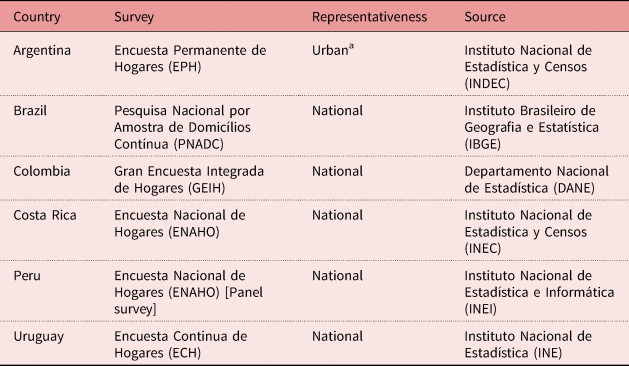

Data used in this paper come from regular household surveys carried out by the national statistical institutes of each of the six selected countries. The analysis covers the period from the fourth quarter of 2019 to the fourth quarter of 2021 in Argentina, Brazil and Peru; in Colombia, the period from the fourth quarter of 2019 to the third quarter of 2021, while in Uruguay it extends from the fourth quarter of 2019 to the second quarter of 2021.Footnote 15 In Costa Rica, the Encuesta Nacional de Hogares (National Household Survey, ENAHO), which surveys all sources of total household incomes, provides information only for June of each year. Table 1 provides information on the surveys used for each of the countries under consideration. In almost all cases, these surveys have national coverage, except for the Encuesta Permanente de Hogares (Permanent Household Survey, EPH) survey for Argentina, which covers only urban areas. All surveys provide quarterly information, with the exception of Costa Rica, as noted above.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Household Surveys

Notes:

a Argentina's survey covers 31 urban centres.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on household surveys.

During enforcement of the lockdown and social-distancing measures prompted by the pandemic, the statistical offices of the countries analysed (as was the case with most statistical offices around the world) shifted their household survey methodology from face-to-face to telephone interviews. It is reasonable to presume that this adjustment could have affected the quality of the information gathered and, consequently, the comparability of estimations derived from the two methodologies. However, despite acknowledging this aspect when releasing the data, these official agencies continued to compute the temporal evolution of several labour and income indicators derived from these surveys during the COVID-19 period. Furthermore, a survey conducted by the International Labour Organization (ILO) of the statistical offices of 110 countries worldwide – including 24 American countries – regarding the implications of household survey measurements during the pandemic concluded that ‘Despite all the challenges, countries also, by and large, did not believe there was a significant increase in bias in published information during 2020.’Footnote 16 Therefore, all the evidence suggests that the impact of the pandemic on the comparability of the country-level data series used in this paper appears to have been minimal, thus providing robustness to the estimations included.

One of the key dimensions analysed in this paper is labour informality. The definition of informal employment is based on recommendations by the ILO's International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS). Accordingly, informal employees are those whose jobs are not subject to national labour laws or to laws concerning taxes or social security regulations. Non-wage workers are considered informal if they – or their production units – are not registered with certain institutions.Footnote 17 To implement this approach to informality in the countries considered, the statistical criteria of the ILO's Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean were adhered to.Footnote 18 This ensured the attainment of comparable data, considering the availability of information in each of the surveys used.

In most countries, informal wage earners are defined as those whose employers do not contribute to the social security system (pensions and/or health). The exception is Brazil, where informal wage earners are those without a labour contract. For informal non-wage earners, informality is generally determined by the absence of enterprise registration with social security or tax agencies, along with the lack of bookkeeping. Two exceptions are Uruguay, where non-wage earners are classified as informal if they do not contribute to social security, and Argentina, where criteria such as the location of the activities (e.g. on the streets) and/or the size of the establishment are used. Thus, while empirical definitions vary slightly across countries, they all follow a similar approach to identifying informality.

Regarding incomes, all household surveys gather data on all monetary components received by household members.

While most of these surveys also inquire about the value of in-kind components, this paper considers only monetary components. Lastly, the information on incomes used corresponds directly to that reported in the household surveys, without resorting to imputations.

An Overview of the Economic and Labour Market Evolution: Going through an Unprecedented Crisis

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered an economic recession of unprecedented magnitude and scope in Latin America, with regional GDP contracting by 7 per cent in 2020. This decline was more than double that of the world as a whole and stood as the most substantial among all regions.Footnote 19

In addition to its depth and scope, a salient feature of this crisis – even for a region characterised by recurring macroeconomic shocks – was the speed of the impact resulting from an immediate supply shock, associated with lockdown and social-distancing measures, and the consequent sharp decline in aggregate demand. The most significant effects on activity occurred in the second quarter of 2020, when GDP fell 14 per cent. In Peru, for example, the decline in the level of activity reached 30 per cent.Footnote 20

The drastic reduction in GDP had an also rapid impact on employment with an intensity that is also unprecedented in the region: it declined by 15 per cent between the first and second quarters of 2020.Footnote 21

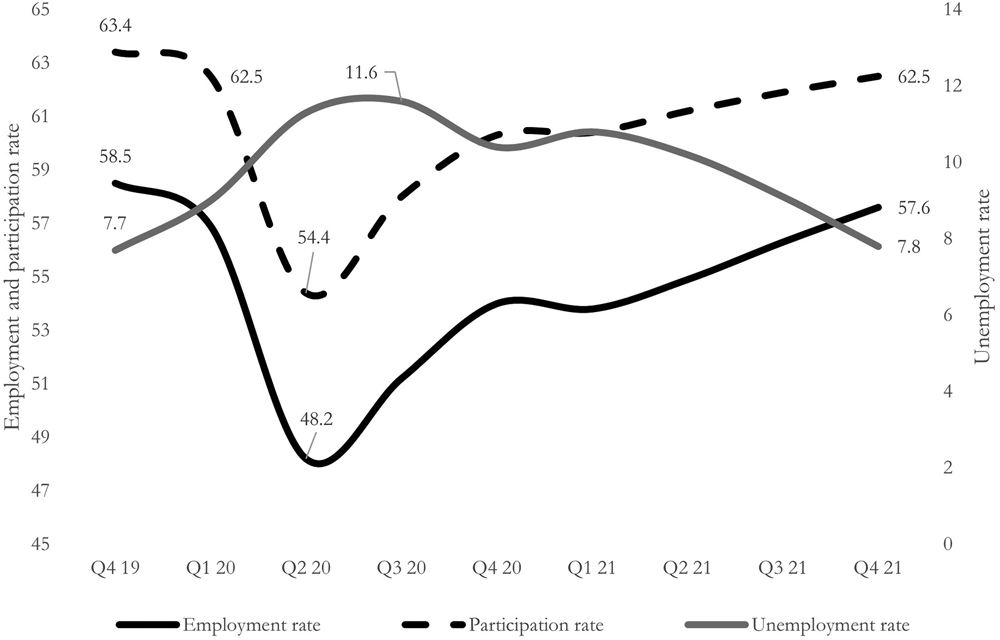

During the period from the outbreak of the pandemic to the fourth quarter of 2021, four well-defined phases can be identified in the evolution of Latin American labour markets, as observed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Latin America: Quarterly Evolution of Labour Market Indicators (%): Q4 2019 – Q4 2021.

Note: Weighted average for Latin America and the Caribbean includes data from Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Jamaica, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, Trinidad and Tobago, and Uruguay.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on ILO, 2021 Labour Overview.

During the first phase (between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2020) the regional average employment rate dropped abruptly by 0.3 percentage points (pp). The sharp contraction in the volume of employment led to transits into unemployment, but mostly to strong outflows from the labour force. During the same phase, the labour force participation rate declined by 9 pp; such reduction significantly curbed the impact of job losses on the unemployment rate. Consequently, compared with previous crises, this indicator only partially reflected the magnitude of the region's labour market difficulties during the initial phase of the pandemic.Footnote 22

Towards mid-2020, the region began to go through a second phase associated with a process of partial recovery of employment hand in hand with the reactivation of economic activity. The employment rate increased by 3 pp in the third quarter and 2.8 pp in the fourth quarter of 2020. In parallel to this, the gradual lessening of mobility restrictions during the second half of 2020 caused some of the people who were out of the labour force to go directly to work, but also others who had lost their jobs at the beginning of the pandemic began an active search.

However, the pathway of partial recovery of regional labour indicators stopped in the first months of 2021, during the third phase. The new waves of infection and the measures to contain them in the face of a slow rate of vaccination, uncertainty regarding macroeconomic and sectoral trends, the greater increase in working hours than in the creation of jobs, and the complex situation experienced by a significant group of companies, particularly micro and small enterprises, were some of the factors associated with the weak labour demand experienced in those months.Footnote 23

The fourth phase began by mid-2021 (depending on the country) to the extent that the region resumed the path of economic recovery on the back of a higher vaccination rate and better control of the health situation. Labour indicators again showed positive variations during the second and, more intensely, during the third and fourth quarters of 2021. However, this recovery was not intense enough to return the region's employment to pre-pandemic values.

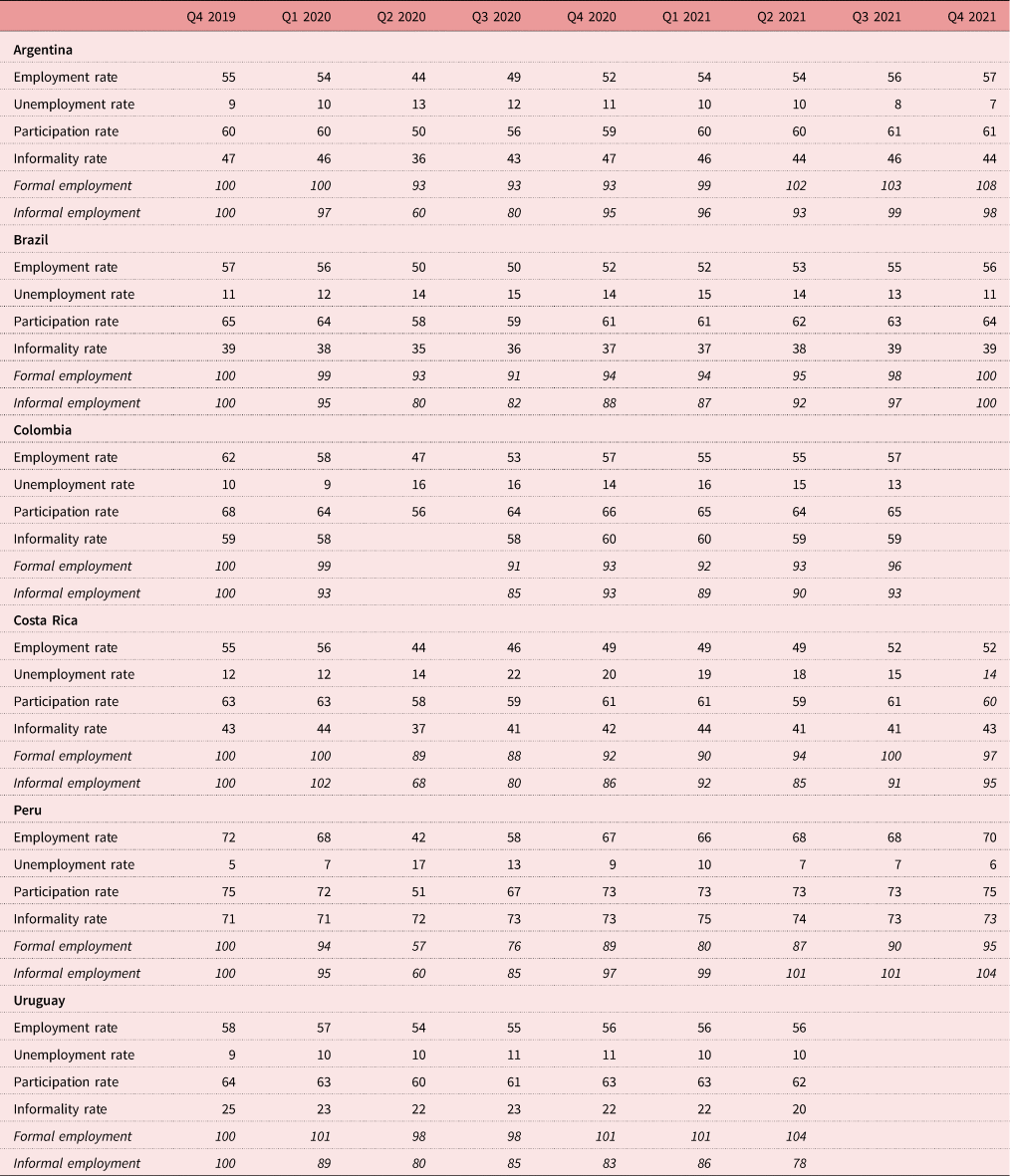

These different phases observed at the regional level in the evolution of the labour indicators are replicated in the countries under analysis, although with varying intensity, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2. Quarterly Evolution of Employment, Unemployment, Participation and Informality Rates (%), and of Formal and Informal Employment, Q4 2019 – Q4 2021

Note: Formal and informal employment are expressed as an index with base Q4 2019 = 100. Informal wage earners are those who lack a labour contract or whose employers do not make contributions to the social security system (pensions and/or health benefits). Informal non-wage earners are those who work for enterprises not registered with specific public institutions or tax agencies and do not maintain bookkeeping records.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on household surveys.

Heterogenous Effects of the Widespread Job Losses and the Partial Recovery Process

The significant reduction in the level of occupation that took place immediately after the outbreak of the pandemic differed between types of employment. In the six countries under analysis, both informal and formal employment experienced pronounced contractions, but with the sole exception of Peru, this fall was greater in informal employment. This meant that the rate of informality dropped (temporarily) between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2020 in these countries.Footnote 24 The only exception was Peru, where there was a slight increase in the informality rate as formal employment fell somewhat more than informal employment. While the formal employment reduction was 2 per cent in Uruguay, 7 per cent in Argentina and Brazil, and 11 per cent in Costa Rica, it soared to 43 per cent in Peru. No data for the second quarter of 2020 is available for Colombia (Table 2).

There are two potential factors that may account for the greater contraction of formal employment in Peru than in the other five countries analysed. On the one hand, Peru did not deploy measures to sustain these types of occupations with the intensity seen in other countries.Footnote 25 On the other, an important characteristic of the labour market in Peru is the high percentage of temporary formal occupations, which leads to a stronger reaction to the economic cycle than in the other countries under consideration.Footnote 26 For comparison, in 2019 the percentage of temporary employment among formal salaried workers was around 1 per cent in Brazil, 2 per cent in Costa Rica, 4 per cent in Argentina, 27 per cent in Colombia, and 63 per cent in Peru.Footnote 27

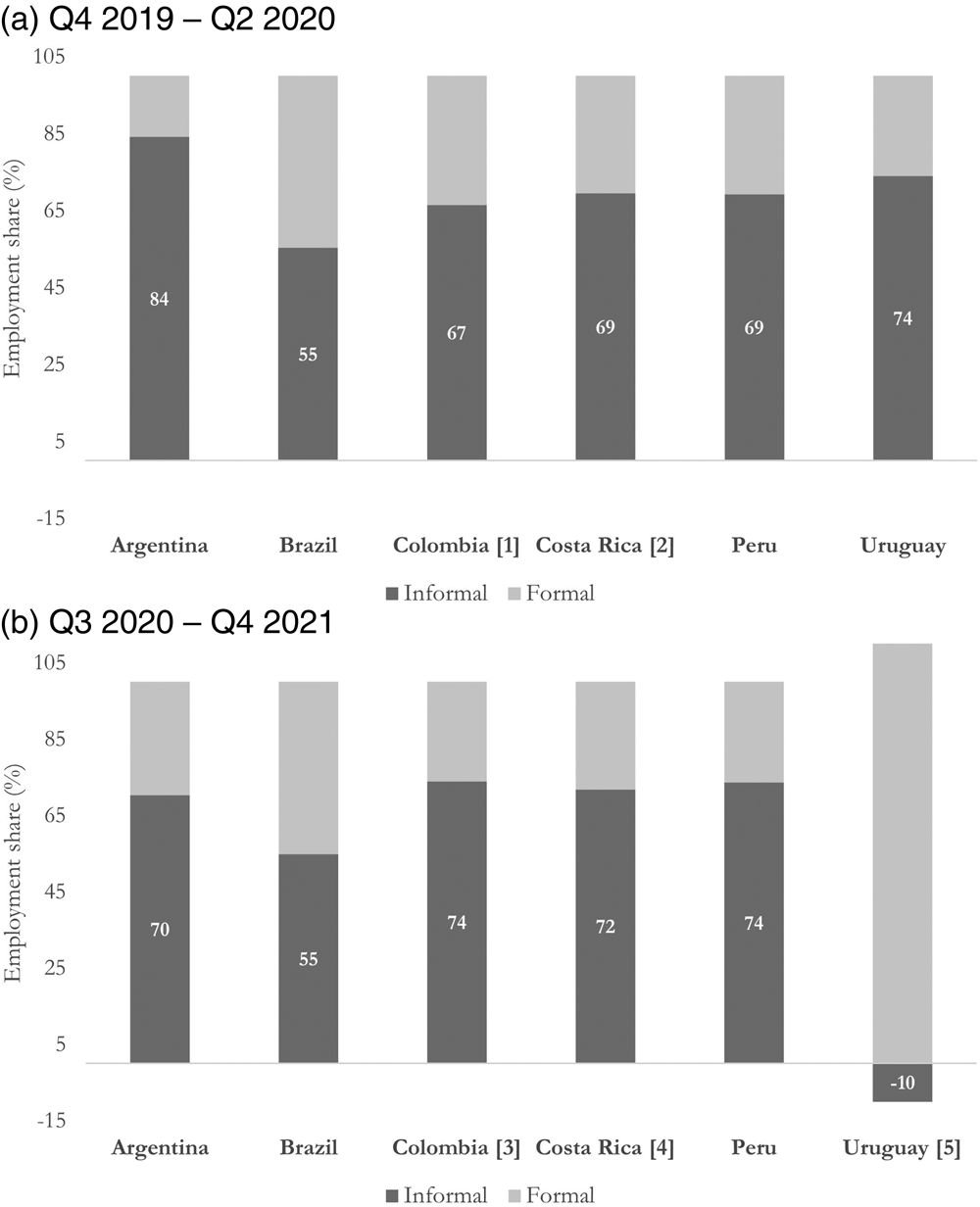

The characteristics of the dynamic of informal employment in the initial phase of the crisis, which explain part of the aggregate evolution described above, differ from those of previous economic crises. In Latin America, and other developing countries, it is usual for informal jobs to play a countercyclical role: they tend to grow when formal employment decreases. However, this ‘adjustment mechanism’ that traditionally comes into play in the region during economic crises was greatly weakened in the context of COVID-19. That is, own-account occupations and, to a certain extent, informal salaried jobs, which typically moderate change in total employment, exacerbated the total employment fall. Consequently, the reduction in informal employment between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2020 (Figure 2a) accounts for between 55 per cent and 84 per cent of the net reduction in overall employment.

Figure 2. Latin America: Contribution of Formal and Informal Employment to Total Employment (%): Q4 2019 – Q2 2020 and Q3 2020 – Q4 2021.

Notes:

[1] Q4 2019 – Q3 2020

[2] June 2019 – June 2020

[3] Q3 2020 – Q3 2021

[4] June 2020 – June 2021

[5] Q2 2020 – Q2 2021

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on household surveys.

Several factors can explain the different evolution of formal and informal employment during this crisis. In 2020, the number of self-employed workers plummeted due to a significant portion of their activities being suspended as a result of lockdown and social-distancing measures. For many of them homeworking was not an option. In 2019, only between 5 per cent and 8 per cent of the total workforce – and only 2 per cent or less of wage earners – in Latin America worked from home. The pandemic abruptly changed this landscape. By the second quarter of 2020, 70 per cent or more of those working from home were wage earners, accounting for nearly all of the increase in workers under this employment modality in the countries under consideration.Footnote 28

Another reason behind the larger fall in informal employment could be the lower costs and fewer restrictions associated with firing informal wage earners. This assertion is based on three pieces of evidence. Firstly, across all six countries considered, as is generally the case throughout the region, labour regulations impose costs on employers for the majority of dismissal types.Footnote 29 Secondly, these lower (or even null) firing costs are one of the factors associated with the greater instability of these occupations and a stronger reaction to economic downturns.Footnote 30 Finally, higher adjustment costs in the demand for formal employment may lead to a decline in hours worked by these wage earners during the early stages of a recessionary phase rather than an increase in layoffs. Indeed, while in 2019 the percentage of wage earners not working a single hour in the reference week was practically insignificant, this increased sharply among formal wage earners during the early months of 2020. For instance, in Argentina, 26 per cent of formal wage earners reported zero working hours compared to 18 per cent of informal workers. These percentages were 8 per cent and 5 per cent in Costa Rica, and 18 per cent and 5 per cent in Peru, respectively.Footnote 31

Furthermore, informal workers are mainly concentrated in smaller enterprises, which found it more difficult to manage long periods without activity. In particular, in 2019, the percentage of informal employment in firms with up to five employees was 54 per cent in Uruguay, around 70 per cent in Brazil and Costa Rica, 75 per cent in Argentina, 84 per cent in Colombia, and 89 per cent in Peru. Total employment in micro and small establishments dropped significantly more than in the rest of the firms in the early stage of the pandemic. In Argentina, this fall was 34 per cent compared to the almost negligible variation in employment in large firms. These figures were, respectively, 12 per cent and almost zero in Brazil, 12 per cent and 7 per cent in Colombia, 15 per cent and 10 per cent in Costa Rica, and 10 per cent and near zero in Uruguay. In Peru, the difference was smaller, 38 per cent and 37 per cent, respectively.Footnote 32

Additionally, sectoral changes in employment also account for the greater contraction of informal employment. Specifically, sectors such as domestic service, construction, trade, and hotels and restaurants were particularly affected during the lockdown stage, with employment declines exceeding the average. In these sectors, the informality rate is higher than the overall informality rate in all countries considered. For example, the informality rate in domestic service ranges from 38 per cent in Uruguay, 60 per cent in Brazil, around 80 per cent in Argentina, Colombia and Costa Rica to 94 per cent in Peru.Footnote 33

Moreover, the greater stability of formal employment compared to that experienced by informal occupations could reflect employers’ expectations that the crisis would be short-lived. Additionally, firms implemented strategies such as shorter working days, temporary suspensions, or teleworking, which increased the stability of formal labour contracts. As mentioned previously, formal salaried workers were most likely to continue working from home.Footnote 34 Lastly, the better performance of formal employment could be associated with the effectiveness of policies implemented to protect it.Footnote 35

The employment recovery phase that began by mid-2020 was mostly driven by growth in informal occupations, except in Uruguay. As depicted in Figure 2, these positions accounted for approximately 70 per cent of net job creation between the second quarter of 2020 and the last observation of 2021 in Argentina, Costa Rica and Peru. A slightly lower contribution was observed in Brazil, around 55 per cent. In each of these countries, this figure exceeded the percentage of informal workers in total employment in 2019, and the informality rate grew during the recovery phase (Table 2). However, this was not the case in Peru and Uruguay. In the former, the informality rate remained relatively constant during the recovery phase. In Uruguay, on the other hand, the contribution of informal employment was, in fact, negative due to the decline in absolute values of this type of employment. Finally, in Colombia, although the contribution of informal positions also exceeded the initial informality rate, it remained relatively constant during this phase of the pandemic.

The faster recovery of informal workers may reflect, on the one hand, that the increase in activity levels did not necessarily require hiring new formal workers; instead, companies might have handled the growing production levels by increasing working hours, including bringing back furloughed employees and those who had been temporarily absent. This is suggested by the fact that just as the decline was more intense in hours worked than in employment during the first two quarters of 2020, so too was the recovery in the subsequent quarters.Footnote 36 On the other hand, it could also indicate that at least some own-account workers, many of whom were informal, were able to resume activities that had been interrupted by the restrictions. The increase in the number of informal salaried jobs can also be partly attributed to the reopening of small businesses, which, as previously shown, have higher rates of informality. During this phase, employment in micro and small enterprises recovered by 48 per cent in Argentina, around 8 per cent in Brazil and Colombia, 18 per cent in Costa Rica, 72 per cent in Peru, and 1 per cent in Uruguay, surpassing the increase among larger firms.Footnote 37

When considering the net effect of both the contraction and recovery phases, different scenarios emerge. Specifically, the informality rate remained unchanged between 2019 and 2021 in Brazil, Colombia and Costa Rica. Argentina and Uruguay experienced a decrease while Peru exhibited the opposite trend.

Country Income Protection Policies Implemented during the Pandemic

The response to the pandemic-induced economic crisis in Latin America resulted in a variety of direct actions aimed at supporting enterprises, protecting jobs and compensating for household income losses.Footnote 38 Particularly significant were the strategies and policies designed to offset, at least partially, the loss of incomes for families in vulnerable situations, especially those whose incomes mainly derived from informal jobs.

Formal workers experienced, on average, smaller reductions in income due to their eligibility for standard labour protection mechanisms, such as unemployment insurance and severance payments. Additionally, many countries implemented specific programmes to reduce layoffs and subsidise firms to cover part of payroll costs. For households with informal employment, non-contributory cash transfer programmes were either expanded or newly introduced. It is well known that a large share of low-wage workers is employed informally, either as wage earners or self-employed, and are consequently part of predominantly low-income households. Although there is significant overlap between low income and informality, this is not absolute, as some households in the lower income deciles rely primarily on income from formal employment. In fact, in some countries, both pre-existing cash transfer programmes and those introduced during the pandemic also targeted low-income families in general.

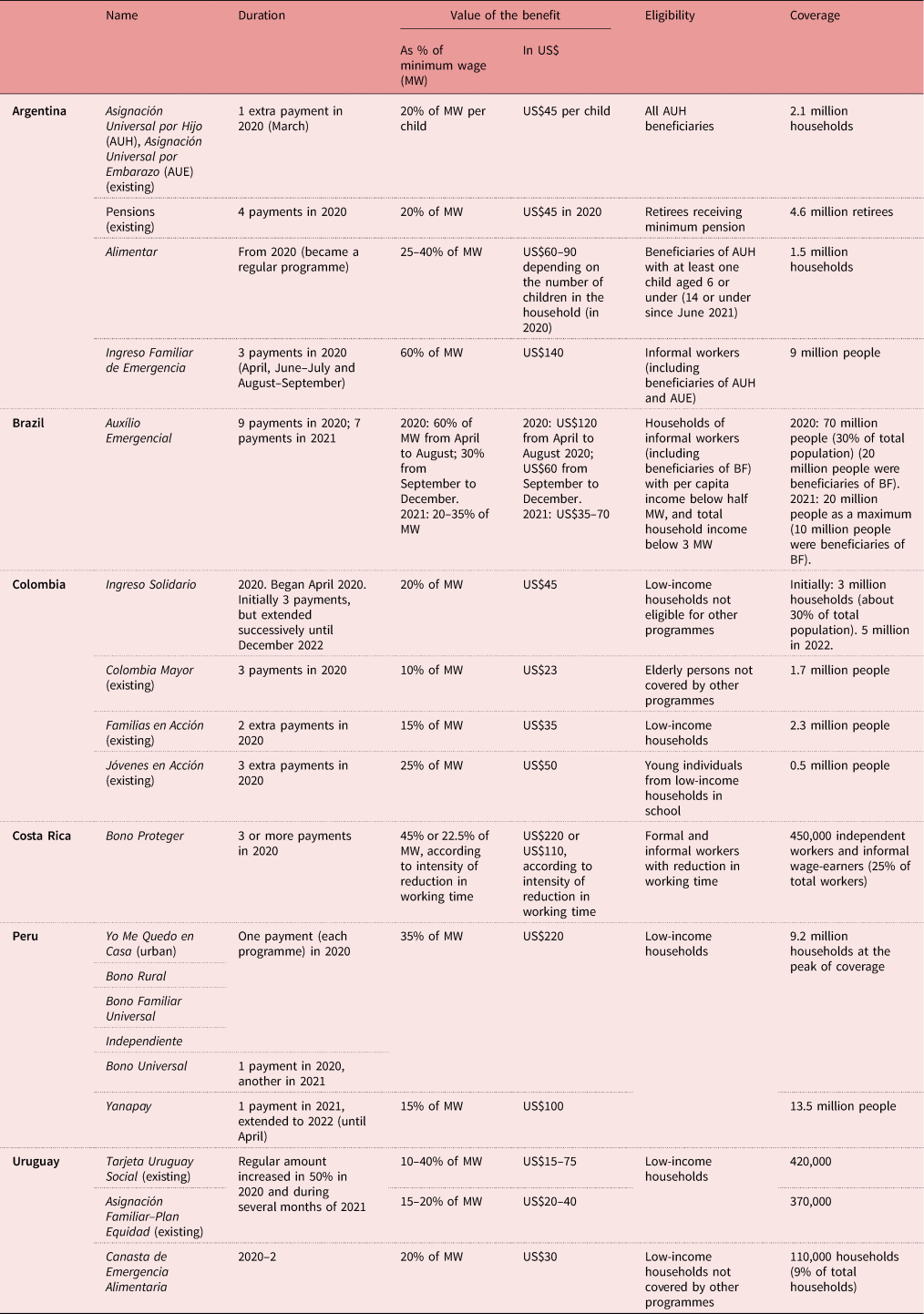

The key features of these public transfer programmes are summarised in Table 3, and a brief description of each is provided below.

Table 3. Public Transfer Programmes Implemented or in Effect during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Note: BF = Bolsa Família

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on official information

In Argentina, recipients of both the Asignación Universal por Hijo (Universal Child Allowance, AUH) and the Asignación Universal por Embarazo (Universal Pregnancy Allowance, AUE) received an additional extraordinary payment of these benefits in March 2020. Additionally, a bonus was granted to retirees in receipt of a single pension benefit during this month. However, the most significant income transfer measure was the Ingreso Familiar de Emergencia (Emergency Family Income), established at the end of March 2020, which consisted of three payments. It targeted informal workers, domestic workers and low-income formal own-account workers. The beneficiaries of the AUH and the AUE were the first groups to be included in this new benefit. Another significant initiative during the pandemic was the Alimentar (Food) programme, which augmented transfers to AUH beneficiaries with children up to six years of age for purchasing food. Initially launched in January 2020, it rapidly expanded in response to the pandemic outbreak and has since become a permanent transfer programme that remains in effect today.

Brazil implemented Auxílio Emergencial (Emergency Aid), a cash transfer programme targeting informal workers, individual microentrepreneurs, self-employed workers and the unemployed, all of whom are in the low-income families category. Households benefiting from the existing Bolsa Família programme received the benefit automatically. The programme provided 16 payments in 2020 and 2021. The transfer was reintroduced from April to October 2021.

Colombia already had three conditional transfer programmes in place: Familias en Acción (Families in Action), Jóvenes en Acción (Youth in Action) and Colombia Mayor (Elder Colombia). The beneficiaries of the first programme received two extraordinary payments during the first months of the pandemic, while those enrolled in the other two programmes received three payments during the same period. At the same time, in April 2020, the Programa de Ingreso Solidario (Solidarity Income Programme) was created to support vulnerable families who were not beneficiaries of any of those three programmes. Initially, three monthly payments were planned, but the programme was successively extended until December 2022.

Costa Rica implemented the Bono Proteger (Protect Subsidy), a cash transfer programme aimed at assisting workers (both wage earners and independent workers) whose working days were reduced due to the pandemic. In 2020, three payments were made to individuals who experienced a reduction in their work hours of more than 50 per cent. Those whose work hours decreased less than 50 per cent also received three payments, but the amount was half that of the former group.

Different cash transfer programmes were implemented in Peru to assist the most vulnerable populations. During the initial months of the pandemic four bonuses were disbursed: Yo Me Quedo en Casa (I Stay at Home), Independiente (Independent), the Bono Rural (Rural Subsidy), and the Bono Familiar Universal (Universal Family Subsidy). A single transfer was provided to the beneficiaries of these programmes. Later in 2020, a new programme, the Bono Universal (Universal Bonus), offered another transfer of the same amount as the previous bonuses to beneficiaries, many of whom had previously received the four above-mentioned subsidies. This bonus was also extended into 2021. In August 2021 a new cash transfer programme, the Yanapay subsidy, was introduced to support vulnerable households. Only one disbursement was issued during that year.

Finally, the monthly value of two existing programmes in Uruguay – Tarjeta Uruguay Social (Uruguay Social Card) and Asignaciones Familiares–Plan Equidad (Family Allowances–Equity Plan) – were increased by 50 per cent for eight months in 2020 and for six months in 2021. In addition, at the onset of the pandemic, the Canasta de Emergencia Alimentaria (Emergency Food Basket) was established. This monthly voucher was provided to informal workers not covered by other protection mechanisms, specifically for purchasing food and hygienic products. It began in April 2020 and was discontinued in April 2022 (July 2022 for beneficiaries with children).

Given the critical role of public cash transfers in the context of the pandemic, they constitute a pivotal component in analysing the evolution of total family income and its distribution. The subsequent two sections delve into these issues.

Evolution of Total Labour and Family Incomes

An indicator that summarises the joint behaviour of employment and individual earnings is the total of all labour incomes received by the population during the period, expressed on a per-capita labour basis. This calculation includes workers who did not work a single hour in the reference week. Labour incomes comprise all monetary components earned in all occupations.

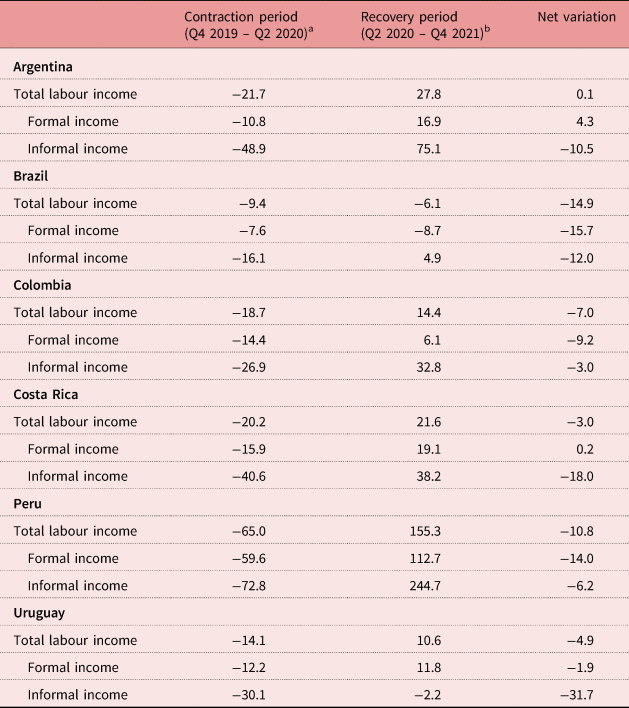

Between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2020, the contraction period, the average per-capita labour income dropped significantly in all the countries considered, with a notable reduction observed in Peru (Table 4). The magnitude of these contractions, which occurred in the space of two or three months, shows the depth of the crisis associated with the pandemic. The differences between countries are closely linked to those between the intensities of total employment reduction in the same period.

Table 4. Changes in Total Per-Capita Labour Incomes (%), Q4 2019 – Q4 2021

Notes:

a Colombia: Q4 2019 – Q3 2020; Costa Rica: June 2019 – June 2020

b Colombia: Q3 2020 – Q3 2021; Costa Rica: June 2020 – June 2021; Uruguay: Q2 2020 – Q2 2021

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on household surveys.

Such strong contractions in each country, in turn, derived from falls in total income from both formal and informal jobs. However, consistent with what was previously observed regarding the behaviour of occupations in each employment category, the fall in the contraction period was substantially higher among informal workers than formal workers, even in Peru.

The increase in employment during the recovery period (between the second quarter of 2020 and the fourth quarter of 2021) generated a positive variation (or reduced the fall) in the mass of per-capita labour incomes. Despite this, however, total labour income generated in 2021 was still below that of 2019, except in Argentina, where the recovery of incomes since mid-2020 represented a return to pre-pandemic levels. In Argentina, Costa Rica and Uruguay the income gap was particularly noticeable within informal jobs. In the former two countries, this occurred despite a greater creation of these types of occupations since mid-2020. In Uruguay, the continuous fall in labour incomes generated in informal jobs even during the recovery period reflects – at least partially – the fact that the informality rate maintained its downward path throughout this entire process. This was due to an increase in formal employment and a decrease in informal employment (Table 2). It is therefore possible to assume that there was a transition from informality to formality during this period.

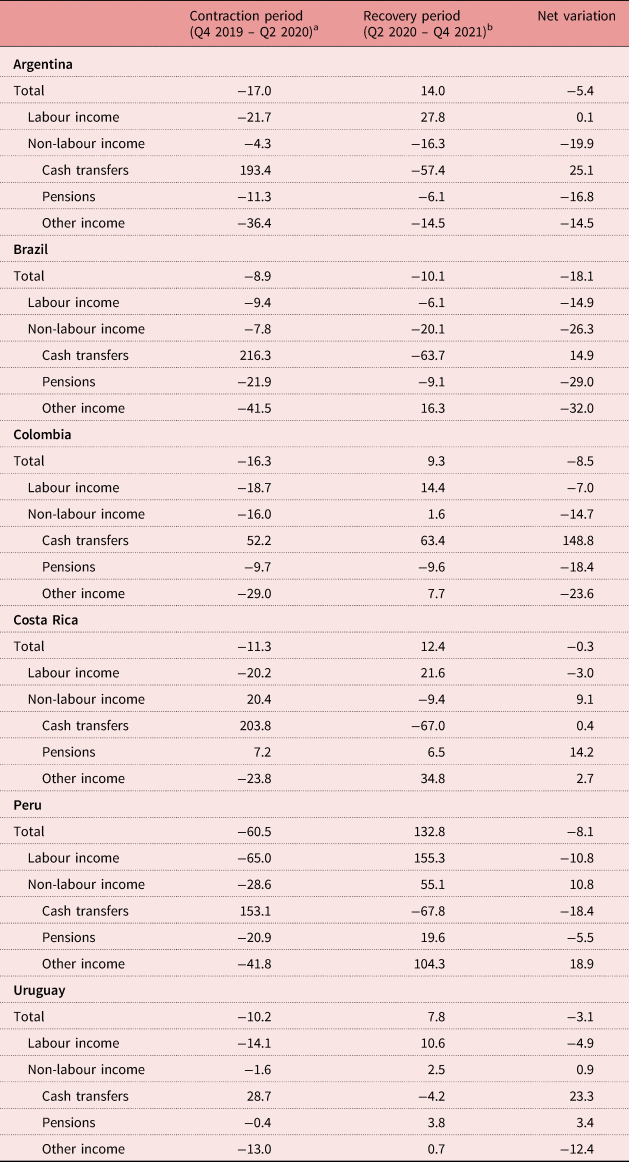

Since labour incomes constitute the largest portion of total family incomes, the latter closely followed the pathway of the former, albeit with varying intensity (Table 5). During the economic contraction period, total family incomes declined to a lesser degree than labour incomes, as non-labour components dropped less intensely (or even increased, in Costa Rica). The relatively better performance of total non-labour incomes was largely attributed to the cash transfer policies implemented at the onset of the pandemic, which helped offset reductions in labour incomes. Even when this compensation was partial, these transfers were relatively significant in Brazil (where the increase in per-capita transfers represented 65 per cent of the decline in labour incomes), Uruguay (35 per cent), Costa Rica (33 per cent) and Argentina (20 per cent). However, they were almost negligible in Peru and Colombia (1 per cent or 2 per cent). These differences reflect variations in the coverage and adequacy of the programmes. For instance, Brazil's main programme reached a large portion of the population, provided the highest monthly benefit (60 per cent of the minimum wage), and included nine monthly transfers in 2020, more than any of the other countries under scrutiny. In Colombia and Peru, the monthly transfers were significantly lower at 20 per cent and 35 per cent of the minimum wage, respectively.

Table 5. Changes in Total Per-Capita Family Incomes and their Sources (%), Q4 2019 – Q4 2021

Notes:

a Colombia: Q4 2019 – Q3 2020; Costa Rica: June 2019 – June 2020

b Colombia: Q3 2020 – Q3 2021; Costa Rica: June 2020 – June 2021; Uruguay: Q2 2020 – Q2 2021

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on household surveys.

The remaining non-labour income components experienced a decline, with the sole exception of contributory pensions in Costa Rica. Therefore, during the most critical period of the pandemic, the only source of income that increased (except in Costa Rica) was that which derived from non-contributory public transfers. As will be seen later, this had offsetting impacts not only on household incomes but also on income distribution.

Conversely, during the recovery period, labour incomes increased more (or fell less, as in Brazil) than total family incomes. In all the countries under examination except for Colombia, the value of cash transfers fell as these countries gradually reduced or discontinued those programmes while employment and, therefore, income from work, recovered. In Colombia, on the contrary, the value of cash transfers increased, in line with the information provided in Table 3 regarding the period during which they were in effect. In this country, as well as in Argentina and Brazil, contributory pensions contracted (Table 5).

The increase in per-capita family incomes during the recovery period fully offset the initial losses experienced by total family incomes only in Costa Rica. In the other countries under scrutiny, a loss of family income (between 3 per cent and 18 per cent) was still observed two years after the beginning of the pandemic. In nearly all the countries being examined, this is the net result of two opposing situations: the aforementioned partial recovery of labour incomes (with the exception of Argentina) compared to 2019 levels and a total value of transfers that exceeded those recorded in 2019 (except in Peru) but failed to fully compensate for the decline in labour incomes. Additionally, in most cases, pensions decreased between the two endpoints of the period considered (Table 5).

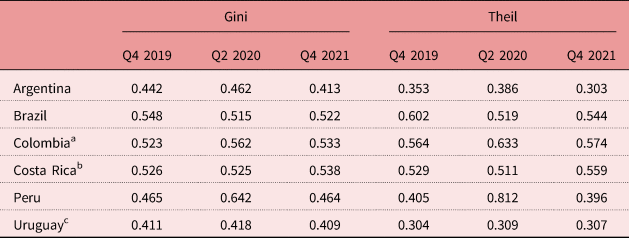

Evolution of Total Family Income Distribution and its Sources

Before assessing the distributive impact of these changes in different income sources, it is important to analyse the evolution of inequality indicators over the two periods considered in the previous section. Except in Brazil and Costa Rica, the inequality of per-capita household income increased between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the second of 2020 (Table 6). The rise was particularly intense in Peru. Subsequently, hand in hand with the recovery of employment, there was a distributive improvement in almost all countries, with the exception again of Brazil and Costa Rica. This positive trend in distribution fully offset its initial worsening in Argentina, Brazil, Peru and Uruguay and, therefore, the inequality indicators do not show a worsening compared to 2019. In Costa Rica and Colombia, the increase in the Gini index between that year and 2021 was not very abrupt, around one Gini point. These net results are unexpectedly positive considering the magnitude of the crisis. Hence, it is particularly valuable to assess the sources of income that underpin these changes.

Table 6. Inequality Indicators (Per-Capita Family Income), Q4 2019 – Q4 2021

Notes:

a In 2020 and 2021 corresponds to Q3.

b In all years corresponds to June.

c In 2021 corresponds to Q2.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on household surveys.

Given the significant disparity in the evolution of incomes from formal and informal jobs, as shown before, a distributive impact is expected, considering the traditionally larger share of informal occupations at the lower tail of the distribution. However, this effect could potentially be offset by the evolution of non-labour incomes. Therefore, the analysis also assessed the extent to which the aforementioned cash transfer schemes implemented by national governments played an equalising role. To accomplish this, two types of examination were carried out. Firstly, a descriptive analysis of changes in total per-capita family income and its sources by income quintiles was conducted. Following this, an econometric decomposition of Gini variation by income sources was performed.

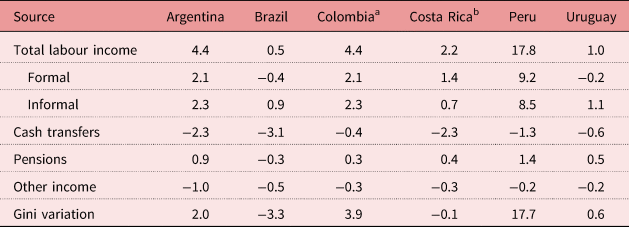

Figure 3 shows the change in per-capita household income of each source – labour income from a formal job, labour income from an informal job, public cash transfers, income from contributory pensions and other household incomes (interest, rent, etc.) – between the end of 2019 and the second quarter of 2020, across income quintiles. In particular, Figure 3 indicates the percentage variation in total per-capita income of each quintile due to the change experienced by each source; i.e. it shows the percentage of the variation of the per-capita total income of each source with respect to the total per-capita income of the initial period.Footnote 39

Figure 3. Changes in Total Per-Capita Family Incomes and their Sources by Income Quintiles (%), Contractionary Period: : Q4 2019 – Q2 2020.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on household surveys.

As was to be expected given the evolution of inequality indices, average household income by quintile fell with an intensity inversely related to income level, except in Brazil and Costa Rica. Such behaviour was mainly associated with that of labour incomes as their reduction affected households at the lower tail of distribution more intensively; the latter even occurred in those two countries whose overall inequality fell or remained constant.

In turn, the influence of labour incomes derived from the significant loss of informal jobs. In particular, in all the countries under analysis the reduction in incomes from informal positions suffered by the first 20 per cent of households was significantly stronger than in higher rungs of the income ladder. This result is explained, on the one hand, by the concentration of informal employment in the lowest quintiles; on the other hand, by the stronger reduction in the aggregate of labour incomes from informal jobs in lower quintiles than income from informal jobs in the mid/high quintiles.

The behaviour of incomes from formal jobs was different between the countries considered. In some of them the intensity of the fall was similar across quintiles while in others it was stronger in the middle part of distribution. This is the net result of the increasing proportion of formal workers along the distribution and a more intense reduction in their incomes at the bottom part of the distribution.

The unequalising effect of changes in labour income was fully offset by the equalising impact of cash transfers in Costa Rica. In Brazil, moreover, this second impact even surpassed the first. Those public policies were also important in Argentina and to a lesser extent in Uruguay. In all these cases, as mentioned, such subsidies reached an important aggregate figure and were targeted at low-income families, although in Costa Rica they were important even for those in the fourth quintile.

In Brazil, the increase in cash transfers led to a rise of 20 per cent of the total per-capita household income of the first quintile, surpassing the 16 per cent reduction in labour per-capita family incomes in this group of households. These transfers also almost fully offset the fall registered by total labour incomes in the second quintile. In Costa Rica, public cash transfers represented three-quarters of the fall in total per-capita labour incomes in the first quintile, and about 40 per cent in the following three. In Argentina, they compensated for about 30 per cent of the decline of labour per-capita household incomes of the first quintile, 35 per cent in the second quintile and 23 per cent in the third. In Uruguay, this proportion was 25 per cent for the first quintile. In Colombia and Peru it had a negligible redistributive effect during the first period of the crisis.

Contributory pensions reinforced the unequalising effect of labour incomes, except in Brazil. Other sources of non-labour incomes had an opposite behaviour in Argentina, Brazil and Colombia, while they were fairly neutral in Costa Rica and Uruguay. In Peru, however, they reinforced the increase in inequality as transfers from other households of the country fell in the first quintile and grew in the fifth.

The results from the exercises of decomposition of the increase in the Gini index by income source during the contractionary period are consistent with this descriptive analysis (Table 7). As mentioned before, the Gini coefficient increased the most in Peru (+0.18 Gini points), followed by Colombia and Argentina. It remained constant in Costa Rica and Uruguay, and actually decreased in Brazil.

Table 7. Decomposition of the Variation of the Gini Index of the Distribution of Per-Capita Family Incomes by Income Source, Contractionary Period: Q4 2019 – Q2 2020 (Gini points * 100)

Notes:

a Q4 2019 – Q3 2020

b June 2019 – June 2020

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on household surveys.

The strongly unequalising role of the labour market and, conversely, the equality-enhancing behaviour of cash transfers are evident in all cases. Regarding labour incomes, changes in incomes from both formal and informal jobs contributed to the increase in inequality in all the countries studied except for Brazil and Uruguay. The increase in cash transfers was the most equalising change among income sources. Indeed, in Brazil the reduction in inequality was almost completely explained by this income source. In Argentina, Costa Rica and Uruguay, both the absolute and relative contributions of this income component were significant as well.

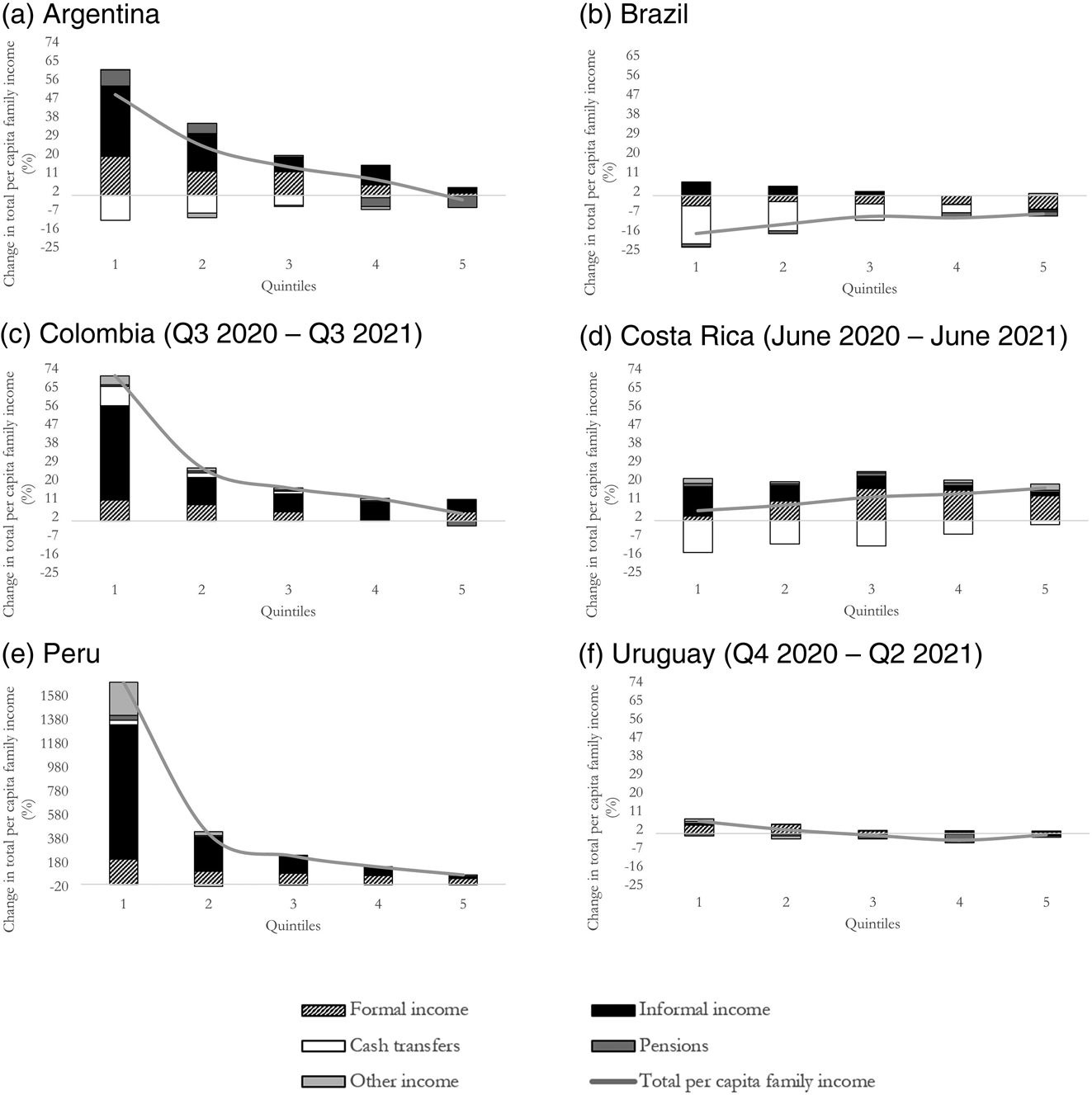

The above-mentioned improvement in income distribution (except in Brazil and Costa Rica) during the recovery period was explained by the steep increase in labour incomes at the bottom part of distribution (Figure 4). The main driver of this expansion was the incomes from informal jobs as these recovered intensively. Only in Uruguay was the growth of labour incomes in the first quintiles, which explains the reduction in overall inequality, associated almost entirely with the steep generation of incomes from formal jobs. In Brazil, labour income had an almost neutral effect as that derived from informal jobs led to a reduction in inequality, but the effect of formal occupations was the opposite.

Figure 4. Changes in Total Per-Capita Family Incomes and their Sources by Income Quintiles (%), Recovery Period: Q2 2020 – Q4 2021.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on household surveys.

Figure 4 also shows that cash transfers tended to have an unequalising effect in Argentina, Brazil and Costa Rica, since their value fell more for households in the first quintiles. On the other hand, they reinforced the equalising effect in Colombia as they added to the larger rise in incomes of those in the bottom part of the distribution. In Uruguay and Peru their role appears to be minimal.

Contributory pensions also led to a reduction in inequality in Argentina, Peru and Colombia as they contributed to increasing incomes at the bottom of the distribution. In Costa Rica, Brazil and Uruguay, the effects are less clear. Other incomes contributed to a fall in inequality in Colombia and Peru; in the latter case, this was mainly associated with the increase in the value of transfers between households in the first two quintiles.

The results of the Gini decomposition during the recovery period provided in Table 8 are, again, consistent with the descriptive analysis. They show that in all the countries the recovery of labour incomes played an equalising role. The results also confirm the negative impact of the evolution of cash transfers on distribution, except in Colombia. In Argentina, Peru and Uruguay, it partially offset the equalising impact of the recovery in labour incomes, while in Brazil and Costa Rica it surpassed this positive change, resulting in the previously mentioned increase in overall inequality during this period.

Table 8. Decomposition of the Variation of the Gini Index of the Distribution of Per-Capita Family Incomes by Income Source, Recovery Period: Q2 2020 – Q4 2021 (Gini Points * 100)

Notes:

a Q3 2020 – Q3 2021

b June 2020 – June 2021

c Q2 2020 – Q2 2021

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on household surveys.

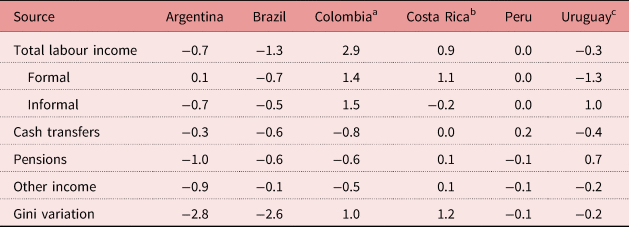

Finally, Table 9 presents the contribution of these income sources over the whole period to the variation in the Gini index. The net result of the contrasting behaviours experienced by labour incomes in the two periods was equalising in Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay, neutral in Peru, and inequality-enhancing in Colombia and Costa Rica. The net impact of cash transfers was also mixed: they contributed to a reduction in inequality in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Uruguay, while they had a null or negligible effect in Costa Rica and Peru.

Table 9. Decomposition of the Variation of the Gini Index of the Distribution of Per Capita Family Incomes by Income Source, Contractionary and Recovery Periods: Q4 2019 – Q4 2021 (Gini Points * 100)

Notes:

a Q4 2019 – Q3 2021

b June 2019 – June 2021

c Q4 2019 – Q2 2021

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on household surveys.

Final Remarks

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered an unparalleled economic, health, labour and social crisis in the world. Latin America and the Caribbean has emerged as one of the regions hardest hit by this crisis. The main aim of this paper was to assess the evolution of family income inequality and its components in six Latin American countries – Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Peru and Uruguay – since the onset of the pandemic.

The paper highlights a significant reduction in household incomes at the onset of the pandemic, leading to a rise in income inequality. This was primarily driven by the substantial loss of informal jobs, which predominantly affects the lower tail of the income distribution. These findings align with earlier predictions made in studies conducted during that period. Additionally, these studies suggested that cash transfer programmes might alleviate income losses for households at the lower end of the distribution. This result is supported by the paper's demonstration of the equalising impact of such measures. Detailed evidence is provided regarding the varying degrees of compensation provided by these programmes across different countries over the period considered.

The article also provides novel insights into the economic recovery period in the region, a timeframe for which studies on how income distribution evolved remain limited. The article reveals that all countries witnessed a reduction in income inequality attributed to rising employment, particularly in informal jobs. However, this positive trend was countered – contrary to the pandemic period – by the cessation or scaling back of cash transfer programmes.

Two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, income inequality in Argentina, Brazil, Peru and Uruguay either remained the same or decreased compared to 2019. This was verified despite the insufficient recovery of total family incomes across all the countries under examination. When considering the entire period, a positive role of cash transfers is observed both in the value of household incomes and in their distribution.

In relation to these transfers, it is possible to identify both progress and challenges. Rapid and timely intervention not only mitigated the immediate loss of income and access to basic goods and services, but also limited the spread of these shocks in the medium term. Previous experience in developing intervention mechanisms helped to reach the population affected by labour income losses more rapidly. However, the widespread impact of the crisis affected even the middle-income segments of the population, whose incomes were also severely affected. In managing the crisis, cash transfer schemes have thus faced the challenge of expanding and improving the registration of these newly vulnerable people and households.

Given the current critical context, it is imperative to sustain the policies put in place in the region in 2020 and 2021, while also embracing a broader agenda of comprehensive and far-reaching policies. This entails pursuing a trajectory of economic growth and stability that generates more and better jobs. Furthermore, it is essential to move towards strengthening income support policies and establishing enduring social protection schemes to reach the most vulnerable segments of the population.