Nutritional labels are designed to promote healthy food choices and serving sizes( Reference Neuhouser, Kristal and Patterson 1 ). However, 70 % of consumers routinely ignore these labels( Reference Campos, Doxey and Hammond 2 , Reference Kozup, Creyer and Burton 3 ), causing researchers to question to their effectiveness( Reference Ollberding, Wolf and Contento 4 ). This is particularly troubling for serving size. Although large serving sizes contribute to obesity( Reference Young and Nestle 5 ), consumers still tend to ignore serving size information and serve larger portions than recommended( Reference Schwartz and Byrd-Bredbenner 6 ). If labels do not drive serving sizes, what does?

Consumers are heavily influenced by external cues in their environment when deciding how much to eat( Reference Wansink 7 ): they are influenced by what they believe as convenient, attractive and normal to serve( Reference Wansink 8 ). What people consider a normal portion may be partly influenced by the manufacturer( Reference Antonuk and Block 9 ). One of the most salient cues is the size of packaging from which a person serves himself or herself. This effect is often referred to as the ‘pack size effect’ and is characterized by the fact that large packages cause consumers to consume more of a product they serve themselves or of a product for which an exaggerated portion has been provided( Reference Marchiori, Papies and Klein 10 , Reference Wansink, van Ittersum and Payne 11 ). The pack size effect has been demonstrated with both meal- and snack-related foods( Reference Wansink 12 ), and also with stale foods. In a study of moviegoers in a Philadelphia suburb, those who were given a large-sized bucket of stale, 2-week-old popcorn ate more than those who were given a medium-sized bucket. Combined with the fact that package and portion sizes have increased over the years( Reference Nestle 13 ), it is argued that the pack size effect significantly contributes to the growing obesity epidemic( Reference Chandon and Wansink 14 ).

The most parsimonious explanation for why large packages lead to increased consumption is that they suggest a larger consumption norm; they implicitly suggest that it is common to consume a larger amount of food than is appropriate( Reference Wansink 7 ). Although the majority of evidence in favour of this hypothesis has focused on manipulating the size of the package, pictures that appear on the package also have the potential to increase consumption norms. Studies reveal that food shown on packaging often exaggerates the recommended serving size which causes consumers to unknowingly overserve. When compared with the recommended serving size, the majority of ice cream containers display pictures of ice cream that are, on average, 130 % more( 15 ). Additionally, when these containers were shown to consumers, they served more ice cream than when shown ice cream containers that had been modified to reflect a single recommended portion.

If what is seen can be more powerful than what is said, these effects should be even stronger for what is seen and not said. This is the case with many of the extras that are depicted on packaging such as sauces on main dishes, syrup on pancakes, dips with chips, sprinkles on ice creams and frosting on cake. How might these extras exaggerate how many calories are pictured and do they lead consumers to eat more calories than they otherwise would? Such findings could have wide relevance to consumer welfare, company packaging policies and to policies from federal organizations that control labelling, such as the Food and Drug Administration. Depending on how widespread or significant the practices are and depending on how they influence consumers, it may mean that simply altering packaging pictures or clarifying the depicted calories could have an immediate impact on either what or how much consumers eat.

Exaggerating consumption norms may legitimize increased consumption by leading people to unsuspectingly follow the norm set out by the manufacturer( Reference Wansink 8 , Reference Antonuk and Block 9 ). Thus, when a consumer continuously perceives a high consumption norm, as in the case with exaggerated serving size food visuals, it may permanently bias the consumer to adopt a higher consumption norm than what is recommended. Given this, it is important to understand the components of food visuals that have the potential to lead consumers to perceive a larger serving size. To determine if pictured extras on a package have the potential to suggest a larger consumption norm, we first conducted an exploratory study that examined how the addition of frosting on cake packages increases the number of calories shown compared with the recommended calories based on the recommended serving size. If frosting exaggerates the number of calories shown then this could cause consumers to unknowingly overserve. In two follow-up studies, we tested this hypothesis by examining the effect that exaggerated frosting visuals has on single serving size calorie estimations and whether they cause consumers to serve more cake. In a final study, we examined the robustness of this effect by testing whether exaggerated frosting visuals cause food professionals to overserve. An increase in intended serving size in this population would demonstrate that even the most nutritionally savvy consumers are not immune to the effects of supplementary extras on how much a person serves.

Cornell University’s Institutional Review Board for Human Participants approved all studies reported in the present paper. For Studies 2, 3 and 4, participants provided informed written consent prior to participating. Study 1 is an observational study that did not involve human participants.

Study 1: Do the calories pictured on packaging exceed the calories stated on the nutrition label?

Method

Study 1 investigated how showing a supplementary product – frosting on a piece of cake – could potentially bias the serving size information that is found on the nutritional labelling. We identified cake brands and flavours by documenting the most common brands found at three US grocery retailers (Target, Walmart and Wegmans). These included cake mixes from Betty Crocker (n 20), Duncan Hines (n 18) and Pillsbury (n 13). Packages were restricted to only those with images of one slice from a round cake.

The dimensions of the slice of cake on the package were measured, including height, length and arc length. Arc length was measured by using a string to trace along the curve of the cake. Arc length was then calculated using the equation

![]() $\theta \,{\equals}\,(\pi \,/\,180){\times}r$

, where r is the radius of the arc. To determine actual arc length factoring in enlargement, we calculated an enlargement factor (EF) using the equation

$\theta \,{\equals}\,(\pi \,/\,180){\times}r$

, where r is the radius of the arc. To determine actual arc length factoring in enlargement, we calculated an enlargement factor (EF) using the equation

![]() $EF\,{\equals}\,1\,/\,(MSL\,/\,CSL)$

, where MSL is the measured slice length and CSL is the calculated slice length. In our calculation, we used a CSL of 4 inches based on the assumption that an 8 inch pan was used.Footnote * Circumference was calculated and divided by EF and serving size to determine the arc length of one serving.

$EF\,{\equals}\,1\,/\,(MSL\,/\,CSL)$

, where MSL is the measured slice length and CSL is the calculated slice length. In our calculation, we used a CSL of 4 inches based on the assumption that an 8 inch pan was used.Footnote * Circumference was calculated and divided by EF and serving size to determine the arc length of one serving.

We then determined how much frosting was pictured by calculating the surface area of the slice. We first measured the thickness of the frosting by measuring the side of the cake (A), the top (B) and in between the layers (C). Our measurements A, B and C were multiplied by EF to get estimated dimensions. Surface area was then calculated using the following equation:

![]() ${\rm surface \;area}\,{\equals}\,2\pi rhA{\plus}\pi r^{2} B{\plus}\pi r^{2} C$

, where h is height. The resulting value was multiplied by grams per square inch and multiplied by calories per gram to get total frosting calories pictured. The sum of the cake calories and frosting calories resulted in total calories pictured.

${\rm surface \;area}\,{\equals}\,2\pi rhA{\plus}\pi r^{2} B{\plus}\pi r^{2} C$

, where h is height. The resulting value was multiplied by grams per square inch and multiplied by calories per gram to get total frosting calories pictured. The sum of the cake calories and frosting calories resulted in total calories pictured.

Results and discussion

Study 1 results are shown in Table 1. When cake calculations were based solely on the cake, cake boxes did not display significantly more calories than what is recommended (t(51)=1·86, P=0·068), a decrease of 5·13 %. Breaking down by brand, only Duncan Hines exaggerated the number of calories shown, displaying 19·89 % more (t(17)=4·05, P<0·001). Both Betty Crocker and Pillsbury displayed fewer calories than what is recommended, 14·91 % and 19·00 %, respectively (t(19)=10·08, P<0·001) and t(12)=43·69, P<0·001).

Table 1 Mean calorie calculations for pictorial representations of cake only and cake with frosting pictured on the front of fifty-one cake packages in Study 1. Depicting frosting on the front of packaging adds 134% more calories than the serving size recommendation found on the nutritional labelling (‘calories’=kcal; 1 kcal=4·184 kJ)

***P<0·001.

In contrast, when frosting was included in the calculation, all cake mix boxes exaggerated the amount of calories associated with a serving size. On average, cake mix containers displayed 134·82 % more calories than what is recommended (t(50)=14·05, P<0·001). Duncan Hines brand displayed 209·17 % more calories (t(17)=12·93, P<0·001); Betty Crocker displayed 102·61 % more calories (t(19)=11·30, P<0·001); and Pillsbury depicted 87·31 % more calories (t(19)=9·31, P<0·001).

When the number of calories for a piece of cake was calculated without frosting, 5·13 % fewer calories were shown than what is recommended. However, when frosting was included, cake depictions displayed 134·82 % more calories than what is recommended. Although it is not surprising that the addition of a calorie-heavy supplement increases the number of calories shown, the addition of frosting as a supplementary product potentially suggests it is appropriate to consume a larger number of calories than what is recommended. Study 2 examined whether the perception of calories per serving is biased by the depictions of extras on packaging. If the addition of frosting suggests a larger consumption norm, then consumers will indicate that it is appropriate to consume a larger number of calories per serving.

Study 2: Do people take extra ingredient calories into account when determining serving size?

Method

Participants were forty-five undergraduates from Cornell University who received partial course credit for their participation. Undergraduates were provided with two types of cake mix boxes and asked to estimate the appropriate number of calories to consume in a single serving. Fifteen undergraduates in the information condition and fifteen undergraduates in the no information condition were presented with a Duncan Hines and a Betty Crocker cake mix box used in Study 1 (they displayed a picture of cake with frosting). Fifteen undergraduates in the control condition were presented with the same cake mix boxes with the exception that the cake image was altered so that it did not contain frosting (it displayed a picture of cake only). Undergraduates in the information condition were told that recommended serving size did not include frosting and were presented with the following text:

If you were to serve yourself a single serving of cake made from this mix, please estimate the number of calories you believe is an appropriate amount to consume. Please keep in mind, that the frosting shown on the front of the packaging is not included on the nutritional labeling.

Undergraduates in the no information condition were provided with the same text, with the exception that the frosting information was removed. Undergraduates in the control condition saw the same text as the no information group. Thus, there were a total of two estimations per person, one for each type of cake mix, and the order in which cake brand was shown was counterbalanced.

Results and discussion

Study 2 results are shown in Table 2. Group estimations were entered into a 3×2 mixed-model ANOVA. There was a significant main effect of condition. Calorie estimations were lowest for those who were shown a cake package with no frosting (F(2, 42)=3·75, P=0·041). There was no difference in calorie estimations between the cake mix brands (478·78 v. 478·53 kcal; F(2, 42)=0·001, P=0·994) and there was also no significant interaction between the groups (F(2, 42)=0·030, P=0·970). Planned comparisons showed that of the participants who were shown cake with frosting packages, the number of calories estimated by people who were told no additional information was higher than by those who were told that frosting was not included on the nutritional labelling (593·07 v. 435·67 kcal; t(28)=1·79, P=0·04). Interestingly, there was no difference in calorie estimations between those who were shown packages with cake and frosting, but told that frosting was not included, and those who were shown packages with cake only (407·23 v. 435·67 kcal; t(28)=0·37, P=0·710).

Table 2 Mean cake calorie estimations by participants (n 45) for each condition in Study 2. Calorie estimations were lower when participants were told that frosting was not included on the nutritional labelling (‘calories’=kcal; 1 kcal=4·184 kJ)

Note: There was neither a significant difference between cake brands, nor a significant interaction between cake brand and condition type.

* Calorie estimations for cake with frosting images were significantly lower when there was a corresponding message than not (P<0·001). There was no significant difference in calorie estimations between the control group and the text group.

In general, people do not take extra ingredients such as frosting into account when considering how many calories to serve. Specifically, there are two important findings from Study 2. The first is that compared with packages with both images of cake with frosting and serving size text information, participants who saw packages with only images of cake and frosting indicated that it is appropriate to consume more calories per serving. The second is that there was no significant difference in calorie estimations between participants who were shown packages with cake and frosting, but no serving size text information, and participants who were shown packages with cake, but no frosting. Together, this suggests that the addition of frosting that is not included on the nutritional labelling causes an increase in what people believe is an appropriate amount of calories to consume per serving. Study 3 tested whether exaggerated frosting visuals cause consumers to overserve.

Study 3: Would clear labelling about extra ingredients reduce serving size norms?

Method

Seventy-two undergraduates who did not participate in Study 2 received partial course credit for their participation. Participants were presented with an unmodified box of Duncan Hines cake mix (that included a picture of cake with frosting) and asked to indicate what they thought would be a normal serving size. To facilitate this, participants were shown cake slices (including frosting) that were pre-cut into individual portions that varied in size in approximate 100-kcal increments (100 to 1200 kcal). Twenty-four participants were presented with a package showing cake with frosting and twenty-four participants were presented with a package showing a cake with frosting with the words ‘frosting not included on the nutritional labeling’. In a control condition, twenty-four participants were shown a modified cake package that showed a piece of cake, with no frosting and no other text information present. All undergraduates were presented with the following text:

In front of you are pieces of cake that are made from the box cake mix that is directly in front of the cake slices. Please take a moment to look at the cake mix box. If you were to select a piece of cake to eat, please select the slice of cake that you believe is an appropriate single serving size.

Results and discussion

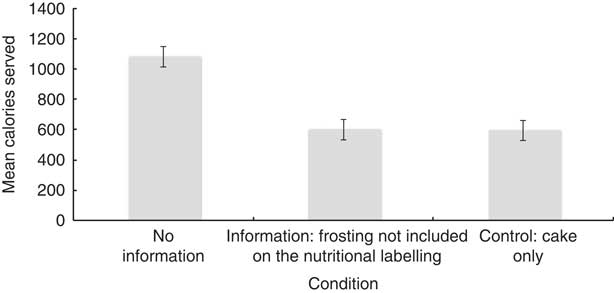

Results for Study 3 are shown in Fig. 1. There was a significant main effect of condition (F(2, 71)=48·48, P=0·001). Intended serving size was lowest for participants who were shown a cake box showing a piece of cake without frosting. t Tests showed that when participants were shown a piece of cake with frosting, intended serving size was lower if the packaging contained the message ‘frosting not included on the nutritional labeling’ (1083 v. 600 kcal; t(46)=8·43, P=0·001), an increase of approximately 483 kcal.

Fig. 1 Mean number of cake calories served by participants (n 74) for each condition in Study 3. Error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. Participants downsized portions when told frosting was not included on the nutritional labelling (‘calories’=kcal; 1 kcal=4·184 kJ)

Similar to Study 2, there was no significant difference in intended serving size between participants who saw cake with no frosting and participants who saw cake with frosting and the phrase ‘frosting not included on the nutritional labeling’ (595 v. 600 kcal; t(46)=0·942, P=0·907).

The results of Study 3 are consistent with our hypothesis that showing supplementary products causes an increase in serving size. However, the use of an undergraduate student sample limits are ability to generalize to all consumers. Thus, in Study 4, we investigated whether the showing of frosting causes food industry professionals to also serve more cake. If it does, then this would provide strong evidence that depiction of supplementary extras causes an increase in what people believe is an appropriate amount of food to consume during a single serving.

Study 4: Would labelling about extra ingredients reduce serving size norms in nutritionally savvy consumers?

Method

Participants were forty-four conference attendees in the food-service industry (aged 19–53 years; 80 % females) who volunteered their participation. All procedures were identical to Study 3, with the exception that there was no condition in which participants saw a cake package with only cake and no frosting. The control condition was removed because Studies 2 and 3 showed that the effect of exaggerated frosting visuals is not present in that condition. Participants were presented with a box of Duncan Hines cake mix and asked to indicate what they thought would be a normal serving size. Twenty-two participants were presented with a package showing cake with frosting and twenty-two participants were presented with package showing a cake with frosting and the words ‘frosting not included on the nutritional labeling’.

Results and discussion

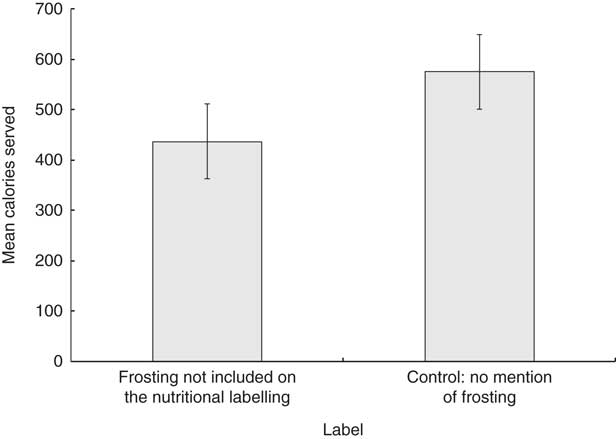

Results for Study 3 are shown Fig. 2. Serving sizes were higher when participants were not told about the addition of frosting than when they were (575 v. 453 kcal; t(42)=1·92, P=0·061), an increase of approximately 122 kcal. Study 3 is thus consistent with our hypothesis that showing supplementary products not listed on the nutritional labelling causes an increase in intended serving size.

Fig. 2 Mean number of cake calories served by food-service professionals (n 44) for each condition in Study 4. Error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. Participants downsized portions when told frosting was not included on the nutritional labelling (‘calories’=kcal; 1 kcal=4·184 kJ)

Even though participants in Study 4 were professional food-service workers, they were still influenced to overstate a serving size unless explicitly told that the supplementary extras are not included in what is stated on the label. This shows that these biases are strong enough to unconsciously influence even the most nutritionally savvy and vigilant consumers.

General discussion

Our four studies show that the addition of supplementary frosting to cake packaging causes an increase in serving size intention. Study 1 shows that pictures of cake shown on packaging correspond to the recommended serving size found on the nutritional labelling; however, the addition of frosting, which is not listed on the nutritional labelling, increases the number of calories shown by 134·82 %. Study 2 shows that perceived serving size calories is lower when participants are told that frosting is not included on nutritional labelling than when they are told nothing. Study 3 shows that intended serving size is also lower when packaging contains the message that frosting is not part of the nutritional information than when the packaging contains no message. Finally Study 4 shows that even food-service professionals overserve when not explicitly told that frosting is not included on the nutritional labelling, suggesting that even the most nutritionally educated consumers are affected by the showing of supplementary extras.

The present results are consistent with emerging literature demonstrating that a pictorial representation of products appearing on packaging affects serving size( 15 – Reference Versluis, Papies and Marchiori 17 ). Given the suggestion that increased portion sizes contribute to the obesity epidemic( Reference Young and Nestle 5 ), these results have important implications for policy officials. To date, policy officials have targeted serving size by referencing numerical labels; however, these interventions have shown limited effectiveness. The present results suggest that a more effective way to convey appropriate serving size information is to combine appropriate serving size depictions with a clear message about what is included on the nutritional labelling.

Relatedly, these findings also have important implications for food manufacturers that wish to promote healthy serving sizes. Recent efforts to promote appropriate serving sizes have focused on creating multipacks that contain premium-priced individualized portions( Reference Wansink, van Ittersum and Painter 18 , Reference Wansink and Chandon 19 ). However, the increased cost of producing this packaging is often passed on to the consumer. A potentially more cost-effective way to promote healthy serving sizes is to explicitly state what is included in the nutritional information. Although this proposition is supported by the present results, future research is needed to better understand how visually appropriate serving size images (and messages) interact with other factors that are known to influence how much a person serves (e.g. convenience).

There are several limitations that can be addressed with future research. First, the present work examined the effect of adding a calorie-heavy, complementary product on serving size. It might be interesting to examine how the perceived healthiness of a supplementary product influences serving size. Given the ubiquitous presence of halo effects( Reference Chandon and Wansink 20 ), it is possible that serving size of a particular product (e.g. a piece of carrot cake) is differentially affected by showing a healthy complementary product (e.g. a carrot) compared with an unhealthy complementary product (e.g. frosting). Second, we did not study consumption behaviour. Thus, it is possible that after overserving participants nevertheless do not consume all the food. However, we interpret this possibility as unlikely. Consumers consume approximately 92 % of what they serve( Reference Wansink and Johnson 21 ) and increased portion sizes lead to increased food consumption( Reference Rolls, Morris and Roe 22 ).

Conclusion

Given that the rise in obesity is associated with increased consumption that is partly due to increasing serving size, it is useful to understand what controllable factors influence how much a person serves. The studies reported here show that the addition of an extra or supplementary product – cake frosting – that is not included on the nutritional labelling causes people to serve more food. Fortunately, however, if people are alerted that such an extra is not included in the calorie count for the portion servings, they reduce how much they think is appropriate to eat.

Although demonstrated in the context of cake frosting, this misleading practice of picturing extra calories on packaging is relevant for sauces on foods, toppings and other supplemental extras. To be less misleading and to help consumers make more informed serving size decisions, manufacturers should explicitly state what is included in the nutritional information.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: J.B. and B.W. conceived of the study. A.C. identified the cake mix brands and calculated the associated calorie estimations for cake and frosting appearing on the front of packages in Study 1. J.B. wrote the first draft and analysed the data for Studies 2, 3 and 4; A.B. analysed the data in Study 1. A.C. and B.W. revised the manuscript for critical content. All authors approved the manuscript as submitted. Ethics of human subject participation: All studies reported in this manuscript were approved by Cornell University’s Institutional Review Board for Human Participants. One study was observational and did not involve human participants; participants provided informed written consent prior to participating in the other three.