Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter demonstrations have shone a light on the various forms of racism experienced by black people in the UK and many other countries. Now more than ever, it is impossible for cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) therapists, supervisors, services and commissioners to ignore the role that race and ethnicity plays in mental health disparities. Each of these overlapping groups need to reflect on their knowledge, skills and actions and consider their role in promoting equal access and outcomes for their patients.

This paper seeks to illustrate developments in improving under-representation of Black, Asian and other minority ethnic (BAME) access and engagement within Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services. It considers literature highlighting over-representation in secondary care and forensic services. We refer to a growing body of evidence exploring historical, current and societal related barriers to accessing primary care mental health for black minority ethnic (BME) populations. We begin to build on their recommendations to start to address these inequalities with a range of actions such as a funded formalised framework.

This paper cannot provide all the answers. The first part of the paper aims to discuss the historical and current societal impacts of systemic racism and funnel this down to the actions of mental health services and individual CBT therapists. Part 2 provides some suggestions on concrete actions that can be taken and demonstrates implementation of the IAPT BAME Positive Practice Guide (PPG) using Southwark IAPT as a case example (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Naz, Brooks and Jankowska2019).

Part 1: Understanding historical, current and societal related barriers to accessing primary care mental health for BME populations

Context

Historical context

Western mental health systems have historically exhibited racial bias. In January 2021, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) issued a formal apology to Black, Indigenous and people of colour, for its support of structural racism in psychiatry (American Psychiatric Association, 2021). With APA’s roots of racism dating back to the 1700s, mental health diagnosis and treatment aligned with the era’s racist social-political policies (American Psychiatric Association, 2021). This is evidenced in selective diagnostic criteria for mental illnesses to justify oppressive practices (Fernando, Reference Fernando2017). During this period, APA upheld racist beliefs regarding blacks being primitive and hostile, which had devastating consequences for their mental health ‘care’. Black patients were segregated from whites and enslaved blacks used as payment for psychological treatment of whites. Interpretive comparative biological differences between whites and blacks have been used to uphold beliefs about inferiority of blacks, where the false rhetoric of Eugenics implied that blacks had smaller brains and were psychologically adolescent (Medlock et al., Reference Medlock, Weissman, Wong and Carlo2016).

For example, the ‘Runaway slave syndrome’: drapetomania was a formal diagnosis provided by white psychiatrists to justify abuse inflicted on slaves who attempted to escape from abusive slave masters (Colman, Reference Colman2015). Severe beatings and toe amputations were medically prescribed to treat the ‘mania’: impulse to run away (Lipsedge and Littlewood, Reference Lipsedge and Littlewood2005). This was pathologised through beliefs that blacks lacked cognitive ability to desire or seek freedom and benefited from enslavement (Ruane, Reference Ruane2019). Rush proposed that black skin on black people was due to a form of leprosy, negritude (Hogarth, Reference Hogarth2019). Pro-slavery advocates were in agreement, although not all physicians were of this opinion (Dumas, Reference Dumas2016; Myers, Reference Myers2014). This evidences how scientific racism attempts to pathologise hypothesised constructions of race, which infer inferiority of racialised people and white superiority (Hogarth, Reference Hogarth2017).

Although there has been some progress from slavery to the modern day, to some extent health advantages have become accepted as intrinsic to ethnicity (Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Alexander, Khan, Nazroo and Shankley2020; Darlington et al., Reference Darlington, Norman, Ballas and Exeter2015; Fanon,Reference Fanon1952; Medlock et al., Reference Medlock, Weissman, Wong and Carlo2016). Blacks are at increased risk of common mental disorder (CMD), yet more likely to receive pharmacological treatment and detention than psychological therapy. This suggests some bias in expectations/beliefs that this can be addressed, stemming from perceptions of cultural or genetic weakness as opposed to disadvantages due to socioeconomic inequalities, and ethnic discrimination (Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Alexander, Khan, Nazroo and Shankley2020; Mason, Reference Mason2003).

Race as a social construct is designed to maintain oppression and dominance of people considered inferior, with white considered the gold standard (Witzig, Reference Witzig1996; Zevallos, Reference Zevallos2017). The dominance and assumed superiority of the social construct of Whiteness is illustrated through history (Frankenberg, Reference Frankenberg1993). Whiteness refers to invisible privileges and power which, via various ideological and cultural practices, systematically maintain structural, racialised and intersectional hierarchies and the oppression of people of colour (Carr, Reference Carr2017).

The Slavery Abolition Act was passed in British parliament in 1833, which allegedly freed slaves across most British owned colonies. The legacy of slavery was not eradicated with centuries of oppressive economic and social practices. This presents implications for intergenerational trauma within the BME population (Fernando, Reference Fernando2017). From 1833 up until 2015, slave traders were in receipt of compensation (up to 17 billion pounds) for loss of earnings; slaves were considered business assets (Olusoga, Reference Olusoga2018). Compensation records evidence that ancestors of David Cameron and George Orwell were among the beneficiaries (Jones, Reference Jones2013). There is evidence of the presence of African Romans in Britain, dating back to the third century (Olusoga, Reference Olusoga2016). Moreover, the famous Windrush marked the arrival of tens of thousands of individuals from the Caribbean in the late 1940s. Our government’s campaign for workers from Commonwealth countries saw increased immigration from 1948 to 1970. The British Nationality Act (1948) gave citizens of UK Colonies the right of settlement in the UK (Jones, Reference Jones1948), with working age adults and many children arriving, joining parents or grandparents in the UK, without their own passports.

Today systems and structures for marginalised groups can be oppressive. Understanding systemic forms of racialisation supports continued growth in equity of access and experience (McKenzie-Mavinga, Reference McKenzie-Mavinga2009). Improved alliance can be developed when CBT therapists understand and acknowledge the historical context of the treatment of black people in various contexts which include health and mental health.

Current societal context

The socio-political landscape can impact the mental health needs of a population, and this is evident in the current COVID-19 pandemic. The devastating impact of discrimination was a correlating factor for higher risk of COVID-19 in BME people (Elwell-Sutton et al., Reference Elwell-Sutton, Deeny and Stafford2020). The service of those on the frontline of health services is impeded by inequalities, which were an issue prior to COVID-19 (Kings Fund, 2020; Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2020). The phrase institutional racism was initially coined by Carmichael et al. (Reference Carmichael, Ture and Hamilton1992), referenced also in the Stephen Lawrence MacPherson report (MacPherson, Reference MacPherson1999). This can be described as routine processes and procedures that translate into actions that negatively shape experiences of racialised groups within institutions (Nazroo et al., Reference Nazroo, Bhui and Rhodes2020). Disproportionality in BAME COVID-19-related deaths have highlighted these disparities.

Furthermore, both Brexit and the Windrush scandal have emphasised the effects of the ‘hostile environment policy’. In 2018, the Home Office was exposed as failing to keep records of the legal status of British Caribbeans, and this led to mass evictions and deportation (BBC News, 2020; Gayle et al., Reference Gayle, Taylor and Gentleman2020). This was met with public protests and pushback which resulted in a commitment to support and compensate those who have been affected (Quille, Reference Quille2018). The commitment has not been upheld.

Public health experts have considered several explanations for the unequal disease burden for the UK BAME population. Razai and colleagues provided explanatory factors as socio-economic, underlying co-morbidity, cultural and epigenetic vulnerability, and occupational inequities (Razai et al., Reference Razai, Kankam, Majeed, Esmail and Williams2021). Williams concluded that racism and poverty could cause biological weathering and increase risk of chronic disease; he noted the implications for BME communities in poorer paid frontline, essential worker roles, statistically more likely to live in crowded accommodation and in deprived areas (Williams, Reference Williams2020a). The ecological analysis of Nazroo and Becares of COVID-19-related mortality rates and ethnic composition of the population accounted for age, population density, area deprivation and pollution; their findings concluded that entrenched systemic and institutional racism were root causes in higher prevalence of BAME COVID-related deaths (Nazroo and Becares, Reference Nazroo and Becares2020).

These data expose the effects of structural inequalities with the potential for increased prevalence of traumatised and disenfranchised BME communities. As CBT therapists we need to consider societal context in the provision of culturally congruent clinical practice.

Current mental health service context

The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (McManus et al., Reference McManus, Bebbington, Jenkins and Brugha2016) indicated that BME communities are less likely to voluntarily seek support for mental health problems. Individuals from a BME background are four times more likely to be detained under the Mental Health Act and diagnosed with severe and enduring mental illness, compared with the white population (Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Mackay, Matthews, Gate, Greenwood, Ariyo and Smith2019). BME groups are broadly perceived as hard to reach and engage with, within the mental health system. A weakness with this argument is that institutional barriers affecting attrition and access for this group are not considered (Joint Commissioning Panel on Mental Health, 2014; Naz et al., Reference Naz, Gregory and Bahu2019; Nazroo et al., Reference Nazroo, Bhui and Rhodes2020).

Memon and colleagues’ qualitative study (Memon et al., Reference Memon, Taylor, Mohebati, Sundin, Cooper, Scanlon and de Visser2016), identified barriers to BME access of mental health provision, which included lack of cultural humility, discrimination and mistrust.

Psycho-social factors affect mental health, whether individuals are asylum seekers who have no recourse to public funds, or second or third generation BME communities. In the literature BME refugees are pre-disposed to common mental disorders through exposure to trauma through pre-displacement, displacement, and post-displacement processes (Schlaudt et al., Reference Schlaudt, Bosson, Williams, German, Hooper, Frazier and Ramirez2020). The South East London Community Health Study (SELCoH) using diverse population samples evidence links between discrimination, ethnicity and migration status (Hatch et al., Reference Hatch, Gazard, Williams, Frissa, Goodwin and Hotopf2016). Hatch and colleagues noted this causality for mental illness within BME populations, with indications that the Caribbean population were at highest risk (Hatch et al., Reference Hatch, Frissa, Verdecchia, Stewart, Fear, Reichenberg and Hotopf2011; Singh, Reference Singh2019). A significant percentage of BME individuals are within low-income families where lack of information, opportunity and support networks will influence life choices and equity of access (Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2018).

Service users who experience themselves as the ‘stigmatised other’ tend to conceal their illness and experience a deleterious effect on the process of their recovery (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Collins, Cerully, Seelam and Roth2017). For some service users, related to the perception of social stigma is low self-esteem, poor employment prospects, lack of money and altered behaviour from others (Corrigan et al., Reference Corrigan, Bink, Fokuo and Schmidt2015). Cross-cultural studies have identified social stigma against mental illness in Eastern Asian societies; for example, Japan has a tendency to delay accessing services (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Sun, Jatchavala, Koh, Chia, Bose and Ho2020). Service users’ self-concept and sense of social identity may be influenced by broader social factors. This may impede rejection of unhelpful labels, denoting negative stereotype, whilst acknowledging their own mental distress (Stuart, Reference Stuart2016).

In order to address low rates of engagement and improve outcomes, service providers need to develop a good understanding of why there is the discrepancy for this population (Whittington and Grey, 2013). It is not enough to identify the existence of inequality for BME populations. This has been illustrated through literature over many years, with common themes consistently conveyed, yet little visible change following on from government strategies as indicated by the data in the Race Disparity Audit (Audit, Reference Audit2018) and Equality and Human Rights Commission (2018). There is a necessity to move forward and address the differing barriers (Memon et al., Reference Memon, Taylor, Mohebati, Sundin, Cooper, Scanlon and de Visser2016).

Over-representation in secondary care

In the last two decades numerous papers have examined the race disparities between under-representation of BAME communities in primary care and the over-representation in secondary adult mental health and forensic services. The Lammy Review (Lammy, Reference Lammy2017) estimated the cost of £309 million for over-representation in the Criminal Justice Courts. The Joint Commissioning Panel on Mental Health (2014) approximated the cost of race inequalities within in-patient and community mental health services at over £100 million. This was attributed to high BME prevalence and re-admissions on both psychiatric intensive care units (PICU) and medium secure care units. Therefore, the comparative individual service-user costs for BME were 58% higher than white service users.

The report provides commissioners with useful guidance in tackling this. However, formal frameworks to resolve longstanding inequalities have not been nationally disseminated within IAPT. Despite specific recommendations for funding via Payments by Results (PBR) to be based on improved access for BAME populations in 2018, this was not implemented widely (NHS England, 2018).

BME people born in the UK are diagnosed with psychosis at a rate nine times higher than white British people (Kirkbride et al., Reference Kirkbride, Coid, Morgan, Fearon, Dazzan, Yang and Jones2010). This occurrence is related to social (isolation, alienation) and environmental factors rather than having a biological basis (Tortelli et al., Reference Tortelli, Errazuriz, Croudace, Morgan, Murray, Jones, Szoke and Kirkbride2015). Perkins and Repper (Reference Perkins and Repper2020) argued that black people were more likely to be detained involuntarily under the Mental Health Act (1983) than other ethnic groups. Understandably, coercion fuels a perception that one will be intentionally harmed by others and may lead service users to mistrust health care providers so that working collaboratively to engage them in psychological therapies becomes an almost impossible task (Mercer et al., Reference Mercer, Evans, Turton and Beck2019). Clearly there is a need to promote cultural awareness within organisations to prevent people from minority ethnic groups being caught in a cycle of relapse and readmission under the provisions of the Mental Health Act (1983).

According to Gordon (Reference Gordon2007), black service user and carer participants described the careful consideration of cultural diversity as essential to the provision of an acceptable service. When they perceived poor communication, with a lack of information sharing between carers and the mental health team, they found those factors affected their engagement. According to black service user participants, when there was a high perceived ‘clash of interests’ between mental health professionals and carers in relation to differences in culturally diverse beliefs and values, this was a barrier to accessing psychological therapies. Mental health professionals and service users in the study spoke about the importance of examining the process of engagement with carers. A service was considered ‘hostile’ when cultural sensitivity was low, and when it did not engage carers in a culturally congruent manner. In contrast, where there was a demonstration of adequate efforts to value cultural diversity, minoritised ethnic groups reported they would be more likely to engage.

Under-representation in primary care mental health

The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (2014) survey found that 14.5% of white British aged 16 and over were receiving treatment for mental health compared with only 6.5% of BME. Data presented within the briefing paper by Carl Baker on Mental Health Statistics for England (Baker, Reference Baker2020) appears to support this view of lower treatment rate. The paper highlighted that 23% BME reported a common mental disorder compared with 17% white British. Yet they are not represented in primary care and are over-represented in psychiatric care (Mercer et al., Reference Mercer, Evans, Turton and Beck2019). In IAPT BME have high attrition rates and lower percentage of referrals, with 86% of self-reported referrals made to IAPT from white British backgrounds. Although there is no evidence that increasing BME access in IAPT will address over-representation in secure settings, studies indicate that social disadvantage and linguistic distance can create pre-disposition to psychosis (Jongsma et al., Reference Jongsma, Gayer-Anderson, Tarricone, Velthorst, van der Ven, Quattrone and Lasalvia2020). This is an area for further research; poor mental health correlates with less access to opportunity in education, community and employment (Haque et al., Reference Haque, Becares and Treloar2020).

The English IAPT is a country-wide initiative delivering psychological therapies recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for mild, moderate and severe common mental disorders (CMDs) in primary care (Clark, Reference Clark2011; Clark, Reference Clark2018). Although CBT is the primary treatment offered, therapy is not limited to CBT. Therapy is accessible using a stepped care model, based on severity of symptoms. IAPT pioneers ongoing transparency in recording of mental health outcomes and demographics of service users, which includes data on ethnicity (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Canvin, Green, Layard, Pilling and Janecka2018). However, equitable access by ethnic populations is not currently set as a key performance indicator by the NHS.

IAPT has been demonstratively responsive to remote working and should commit further to learning and implementation of adaptations for increased access. IAPT is strategically placed to contribute to the working solutions in improving access and engagement for the BME population, which may be further compromised due to experiences relating to COVID-19 and accumulative racial injustices (Royal College of Psychiatry, 2020; Murray, Reference Murray2020).

National ethnic differences in access and recovery rates

NHS England (2020b) have national data on numbers accessing services but not rates relating to ethnicity and the population within areas. Data on access by ethnicity are examined by some individual services and we will report on that in the next section.

The IAPT recovery rate of 50% was met by the white population averaging at 52.4%, compared with black British Caribbean and black British African 49.4 and 48.3%, respectively. However, there are substantial discrepancies between the rates of white British and BME communities in accessing IAPT. Invariably distinctions differentiating ethnic groups are not always recorded or lack specificity (Loewenthal et al., Reference Loewenthal, Mohamed, Mukhopadhyay, Ganesh and Thomas2012). This indicates that BME retention, and numbers accessing and recovered at completion of treatment may be proportionately lower.

The individual context: CBT therapist and patient

The British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP) does not explicitly refer to cultural competence within their Standards of Conduct Performance and Ethics (BABCP, 2018), although several health professional associations reference this (Haarhoff et al., Reference Haarhoff, Thwaites and Haarhoff2016).

An excerpt from their current standards is limited to: ‘You must not allow your views about a service user’s sex, age, colour, race, disability, sexuality, social or economic status, lifestyle, culture, religion or beliefs to affect the way you treat them or the advice you give. You must treat service users with respect and dignity. If you are providing are, you must work in partnership with your service users and involve them in their care as appropriate.’ (p. 6).

A recent BABCP Diversity and Inclusion audit made recommendations for inclusive policy, procedure, campaigns and research including cultural competence training as accreditation criteria for CBT therapists, which would benefit the BME community (Murray, Reference Murray2020). It is of note that BABCP’s revision of training standards are currently at consultation stages.

Understanding microaggressions in CBT

The therapeutic alliance has been heralded as a key component for successful psychotherapy where emphasis is placed on the merits of unconditional positive regard (Okamoto et al., Reference Okamoto, Dattilio, Dobson and Kazantzis2019; Rogers, Reference Rogers1957). The therapeutic alliance can impact access and retention of service users in mental health provision (Hartley et al., Reference Hartley, Raphael, Lovell and Berry2020). Implicit or explicit bias and microaggressions may threaten this (Sue et al., Reference Sue, Capodilupo, Torino, Bucceri, Holder, Nadal and Esquilin2007). Microaggressions are intentional or unintentional racial slights or derogatory comments, and as therapists we need to be aware of our own assumptions, prejudices and stereotypes. The absence of this risks repetition and reinforcement of daily discrimination experiences for BME service users in the therapy room (Lago, Reference Lago2011).

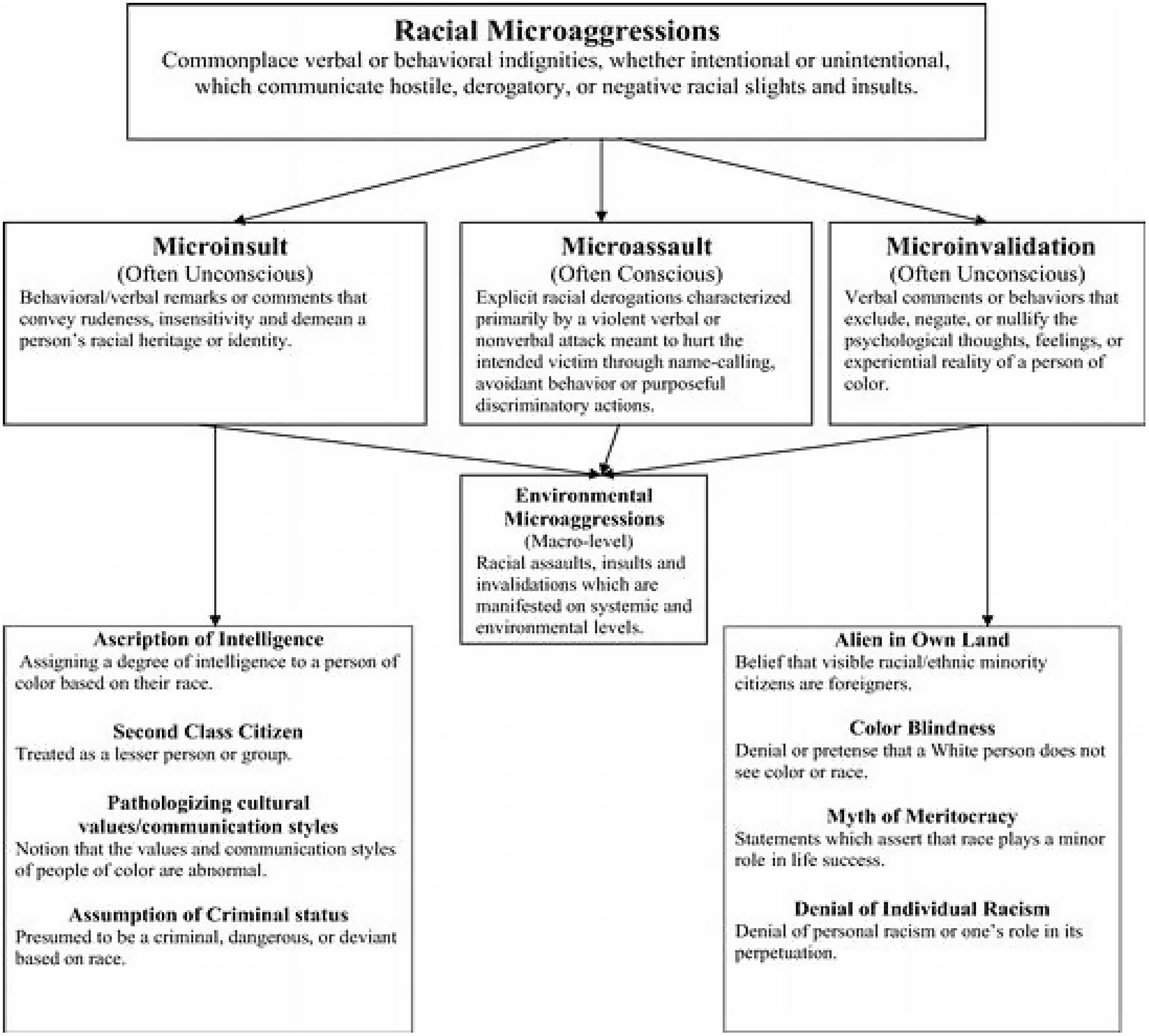

A review by Sue (Reference Sue2010a,b) provided a taxonomy of aversive racism. These were identified as microassault, microinsult and microinvalidation, as illustrated and explained in Fig. 1 (Sue et al., Reference Sue, Capodilupo, Torino, Bucceri, Holder, Nadal and Esquilin2007; Sue, Reference Sue2010a,b).

Figure 1. Racial microaggression categories and their relationships (Sue, Reference Sue2010b; p. 29). Copyright © 2010 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduced with permission.

In summary, microassault and microinvalidations are deemed unconscious (and thus unintentional) and microinsult as conscious. Microinsults are characterised primarily by a verbal or non-verbal attack meant to hurt the intended victim through name-calling, avoidant behaviour, or purposeful discriminatory actions. Terms intended to belittle and lead to questioning of one’s identity effects motivation, causes low self-esteem and internalised prejudice (Saleem et al., Reference Saleem, Anderson and Williams2020).

It is important to consider power dynamics between BME therapists and white patients, in addition to white therapists with BME service users and BME staff with white staff (Constantine and Sue, Reference Constantine and Sue2007). White therapists as members of the larger society may not be immune from inheriting the racial biases of their forebears (Burkard and Knox, Reference Burkard and Knox2004). A systematic review has evidenced how racism, prejudice and stereotype can impact on BME service user psychological safety (FitzGerald and Hurst, Reference FitzGerald and Hurst2017).

Several papers have defined and conceptualised the impact of microaggressions (MA) on BME and BAME service users (Saleem et al., Reference Saleem, Anderson and Williams2020; Solorzano et al., Reference Solorzano, Ceja and Yosso2000; Sue et al., Reference Sue, Capodilupo, Torino, Bucceri, Holder, Nadal and Esquilin2007; Williams and Halstead, Reference Williams and Halstead2019; Williams, 2020; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Rouleau, La Torre and Sharif2020). Kanter and colleagues’ randomised controlled trial indicated that therapists had difficulties acknowledging microaggressions or may be defensive; however, defiance may imply bias and in practice may pose demonstrative detrimental effects on emotional rapport and empathy (Kanter et al., Reference Kanter, Rosen, Manbeck, Branstetter, Kuczynski, Corey, Maitland and Williams2020). The trial evidenced how workshops on cultural competence mindfulness in inter-racial interaction improved white therapists’ emotional rapport and responsiveness towards BAME patients (Kanter et al., Reference Kanter, Rosen, Manbeck, Branstetter, Kuczynski, Corey, Maitland and Williams2020). Williams and colleagues’ Racial Harmony study evidenced ways of reducing microaggressions and improving inter-racial connections (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Rouleau, La Torre and Sharif2020). Both Beck (Reference Beck2016) and Carter (Reference Carter1995) have suggested that transcultural therapy is more successful when white therapists are comfortable with difference and discussions on discrimination. We reference specific clinical examples in the next section of this paper.

The individual context: CBT therapists and service users

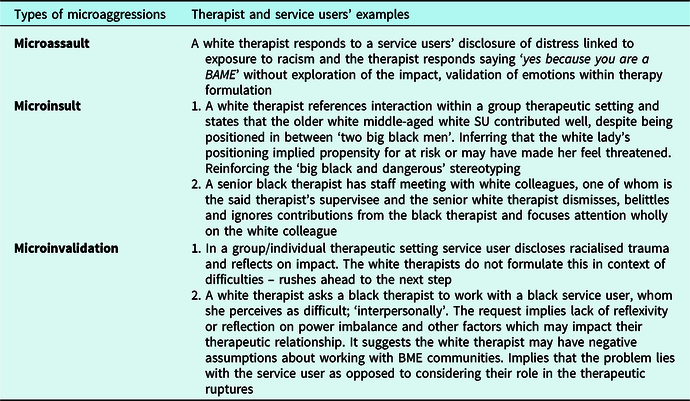

Beck (Reference Beck2019; p. 2) noted that many CBT therapists ‘may steer away from discussions on race’ and the impact of racism on the service users’ mental health. A 2016 qualitative study found that BME service users felt that therapists may not understand their presenting problem within their psycho-social context (Memon et al., Reference Memon, Taylor, Mohebati, Sundin, Cooper, Scanlon and de Visser2016). The last few decades have seen recognition, identification and understanding of microaggressions within therapeutic settings. Therapists from all backgrounds need to bring this to their consciousness within their work. Table 1 illustrates examples that help explore subtle nuanced behaviour that can cause harm in relationships between both BME and white therapists and white therapists and BME service users. Whist we cannot assume that there would not be potential for therapeutic ruptures between people from similar backgrounds, this depicts specific examples and implications of bias and prejudice.

Table 1. Examples of microaggressions in clinical practice

Intended or not, in whatever form verbal indignities, unintentional physical responses of fear or disgust may occur, these frequent racialised slights serve only as a reinforcement that BME people do not belong, perpetuating negative stereotypes (Forrest-Bank, Reference Forrest-Bank2016). These examples are not there to shame or degrade, rather to educate and aid healthy discussion in safe spaces to explore issues within the therapeutic setting. There is much to learn about inclusive working and no one group, or person, has the monopoly on cultural competence (a concept difficult to measure; in relation to attainment, this is indeed a lifelong pursuit for us all). A recent literature review of related terms by Curtis et al. (Reference Curtis, Jones, Tipene-Leach, Walker, Loring, Paine and Reid2019) found definitions of cultural safety more helpful: ‘a focus for the delivery of quality care through changes in thinking about power relationships and patients’ rights’. This suggests that challenging our own culture and cultural systems engenders cultural protection (Curtis et al., Reference Curtis, Jones, Tipene-Leach, Walker, Loring, Paine and Reid2019; p.12). We are in this together, no one person is immune to prejudice on a range of dimensions. These frameworks on issues of race may transfer to consideration of discrimination on other intersectional domains. As CBT therapists we all need to navigate towards more inclusive practice.

Barriers to implementation of formal frameworks for equitable access to psychological therapies

It has taken a global pandemic for calls for better funding and research for mental health (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, O’Connor, Perry, Tracey, Wessely, Arseneault, Ballard, Christensen, Silver, Everall, Ford and Bullmore2020). Prevalence of common mental disorder within BME communities, linked to inequalities, is not a new phenomenon (Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2016). The absence of key performance indicators (KPI) on diversity and inclusion, within IAPT services, suggests that addressing inequities in access are not IAPT core business. Funding to implement the pioneering BAME PPG guide (2019) has not materialised.

There is a need for local commissioning bodies to support a standardised formal framework, with related KPIs, otherwise services may struggle to implement the audit tool. At a recent Public Health England webinar, Williams gave examples of communities of opportunity (Williams, 2020). This included provision of care that addresses the societal context. As CBT therapists, supervisors and clinical leads, our work is greatly assisted by partnership working with both statutory and non-statutory organisations (Beck and Naz, Reference Beck and Naz2019; Fountain et al., Reference Fountain, Patel and Buffin2007).

Formal frameworks for integrated BME access

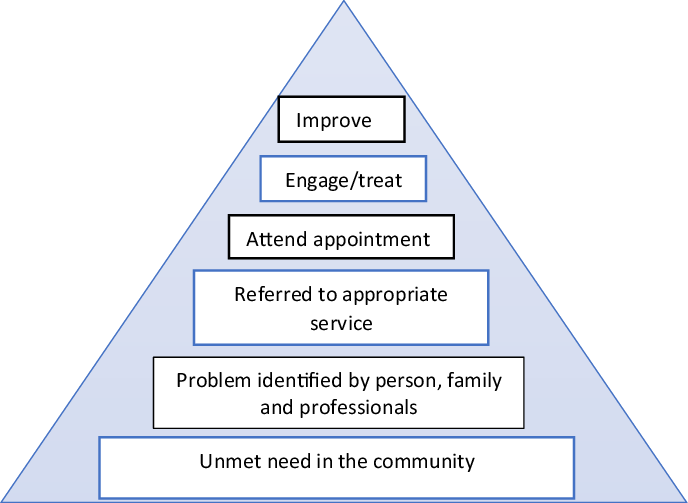

The model of Beck and Naz (Reference Beck and Naz2019) illustrates unmet need in the community and steps to address this. The bottom-up pyramid (see Fig. 2) displays a baseline of unmet need, with the peak representing recovery. It demonstrates barriers that BAME populations encounter at each level of the pyramid (Beck and Naz, Reference Beck and Naz2019).

Figure 2. The journey from having unmet need to successful treatment (Beck and Naz, Reference Beck and Naz2019). Reproduced with permission.

The diagram highlights the barriers to successful treatment from community to recovery stages. The narrowing of the pyramid is a visual representation of reduction in numbers before and after the assessment and treatment phase. The research of Beck and Naz (Reference Beck and Naz2019) indicated that poor conceptualisation impacted on drop-out rates, where there is an absence of formulation of racialised contexts. Several papers support the need for this, which we discuss below (Beck, Reference Beck2019; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Metzger, Leins and DeLapp2018).

Their findings highlight how retention of service users can be improved from referral through to completion of treatment, by co-location of therapists (Fountain et al., Reference Fountain, Patel and Buffin2007). To address unmet need access, attrition and recovery rates, we suggest co-location of CBT therapists within representative community groups. The presence of an IAPT therapist in these settings can evidence the value IAPT services place on the community. Statutory services within the community destigmatise mental health provision. With opportunities for reciprocal learning (Fountain et al., Reference Fountain, Patel and Buffin2007) this may support IAPT services’ ability to recognise, appropriately assess and treat CMDs across cultures. This infrastructure supports the development of representative research within these communities, which IAPT services are well positioned to support (Hakim et al., Reference Hakim, Thompson and Coleman-Oluwabusola2019).

Where therapists may lack the necessary skills to engage and successfully treat BME service users, mandatory training on cultural safety, cultural humility and white privilege may support this (Naz et al., Reference Naz, Gregory and Bahu2019). This also poses implications for diversity training in CBT training programmes, of which we do not have the scope to review within this article. Although CBT models are idiosyncratic in nature, the CBT evidence base may not always be generalisable to BME or BAME populations. This is due to majority white homogeneity in research samples. Culturally congruent approaches need to be implemented and embedded within assessment and treatment formulation (Beck, Reference Beck2019). IAPT may consider collaborative research and learning from experts in Afrocentric psychology approaches, to build a representative evidence base (Majors et al., Reference Majors, Carberry and Ransaw2020). A growing body of literature endorses service change and outreach work, evidencing improved access, experience and outcomes for BAME communities (Kada, Reference Kada2019; Naz and Beck, Reference Beck2019). The structure of CBT services has a role to play in assisting CBT therapists to address these needs.

Part 2: Example of implementing the BABCP BAME Positive Practice Guide audit tool

The 2019 BAME PPG audit tool aims to support services and clinicians to develop anti-racist practice. It covers four key areas: improving access, cultural adaptations, community engagement, and workforce and local population demographic.

There are numerous examples of good practice in inclusion work at Talking Therapies Southwark (TTS); a few will be elaborated upon in the next section. It is important to add that demanding IAPT targets and current commissioning equate to constraints in dissemination and development of some ideas. TTS staff members were inspired by the 2019 launch of the BAME PPG which sparked mobilisation of a BAME Positive Practice Initiative. TTS has set up a Positive Practice BAME working group with the following objectives:

-

(1) Share good practice and strategic ideas for implementation in increasing access for the representative Southwark populations.

-

(2) Share knowledge and methods on use of cultural adaptative/sensitive therapy.

-

(3) Provide reflective safe space to consider intersectional identities in the context of reflexivity and power imbalance in the therapy room.

The audit tool supports practical implementation of such initiatives. Services may consider identifying champions to lead in each of the four key areas. The time to develop this work requires recognition within core work targets. This section refers to findings of a review using this audit tool for TTS. Local Trust approvals were not required as data required was extracted from the national IAPT database.

Southwark demographics

Southwark is a richly diverse inner London Borough. Both deprivation and affluence are represented in neighbourhood wards. Just over half (54%) of Southwark’s population is of white ethnicity, a quarter (25%) BME and a third of Asian (11%) or other (10%) ethnicities. This differs from the rest of London where a considerably smaller proportion (13%) identify as black, and a considerably larger proportion identify as Asian (21%). The ethnic diversity of the borough varies markedly across age groups and the population under 20 is much more diverse than other age groups, with a similar proportion of young people from white and black ethnic backgrounds (Council, 2019).

Talking Therapies Southwark review

The review (using the audit tool) identified robust screening policies and procedures where ethnicity is recorded of nearly 97% of open cases on the Southwark IAPT data set, allowing for a small percentage of service users who choose to not disclose their ethnicity. It was identified that providing a rationale for monitoring may support disclosure of ethnicity. Although data on ethnicity of referrals that do not reach screening stage are not captured, this implies the need to refine processes to obtain ethnicity recording on referral forms.

Reports demonstrate mapping of ethnicity of the population. Local authority Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA) data are consulted as they provide detailed analysis of local demographics, which was compared with TTS data.

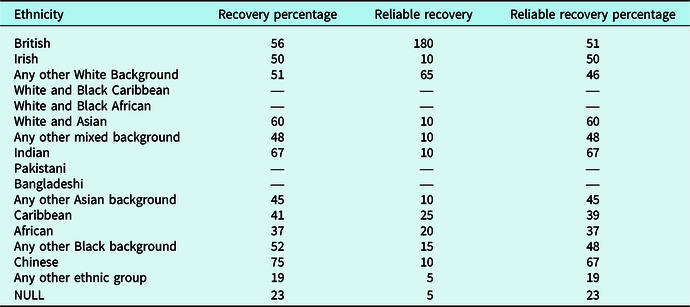

The review confirmed that BME service users have a lower recovery rate than white British service users. The mean recovery rate for BME population was 48%. The Bangladesh community has the only lower recovery rate compared with other ethnicities. Access rates are illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2. Talking Therapies Southwark 3rd quarter dataset (2019/20): recovery by ethnicity

With 25% of the Southwark population from BME backgrounds, this equates to 78,500 people of the total population of 314,200. 2955 referrals were made to Southwark IAPT for the 3rd quarter IAPT data set 2019/20, 630 of those were BME: 285 African, 180 Caribbean and 75 of mixed heritage, either White British and African or White British and Caribbean, with 90 any other Black background. This equates to 21% of total referrals (JSNA, 2018/19). What is significant is the difference in number of BME accessing services to number completing treatment and recovering; only 145 of 630 referrals completed treatment, less than 20%. Recovery rates for Caribbean were 41%, African 37% and 52% of any other black background. This evidences that at least 80% of BME people drop out of therapy between referral, assessment and into treatment stages.

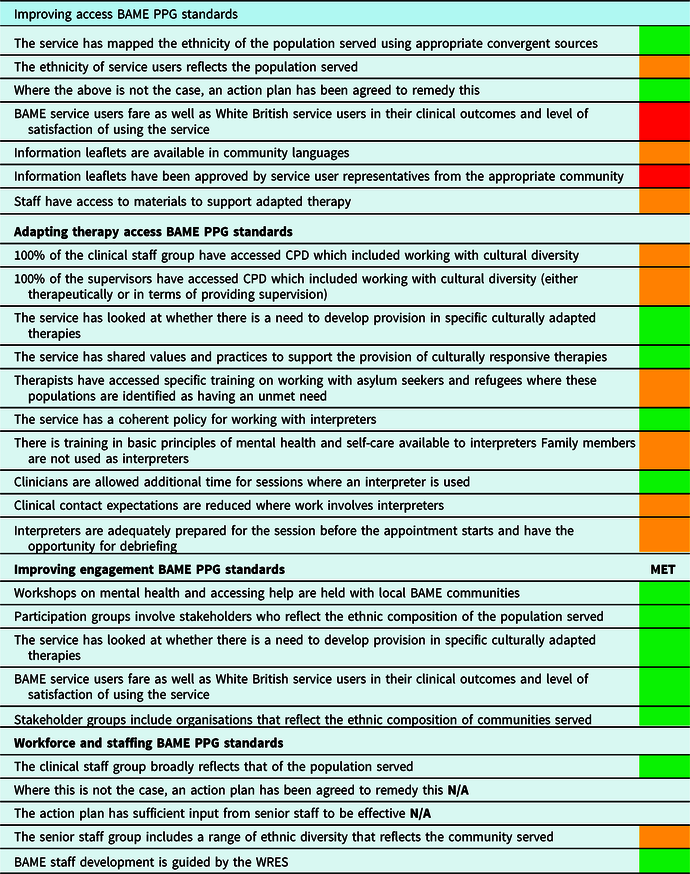

The most recent IAPT dataset confirmed that TTS do not currently have people accessing the service and completing treatment who fully reflect the population served. Action to remedy this is evidenced by the BAME Initiative working group, QI project targeted at BME communities, engagement with our South London and Maudsley (SLaM) Trust wide IAG (Independent Advisory Group) meetings, and development of an online Race Identity & Me group. Table 3 displays the results of the BAME PPG audit tool for TTS.

Table 3. BAME PPG standards 2019: improving access, adapting therapy, improving engagement, and workforce and staffing

Some materials in representative languages have been sourced from the Royal College of Psychiatry. Southwark work closely with the Multi-Ethnic Counselling service to provide service users the option of support in their first language, in addition to provision of interpreters where required within the service, although training has been delivered on depression and anxiety across cultures to CBT therapists within the SLaM trust within the last two years. This needs to be mandatory and delivered annually. TTS arranged further training which included cognitive behavioural therapists, counsellors, clinical psychologists, dynamic interpersonal therapists (DIT), eye movement desensitisation (EMDR) therapists, interpersonal therapists, and psychological wellbeing practitioners (PWPs).

The present context provides opportunities for virtual co-location, co-production and delivery. TTS therapists are usually co-located in GP services and Childrens’ Centres. Mummies Republic (MR) is an example of integrated community provision of psychological therapies. It is a partnership with the South London Mission church in Bermondsey, providing support for BAME mothers, many with no recourse to public funds and seeking asylum, hence being less likely to access traditional mental health provision, despite increased vulnerability to forms of abuse. Moving forward, services may need to consider development and delivery of digital therapies in partnership with community groups in the current absence of physical co-location, with potential virtual co-location and consultation with community groups, and co-production of materials with therapists and community representatives.

In TTS overall, there is good BAME representation in the workforce and the team broadly reflect the population served. BAME staff have equal access as white staff to continued professional development (CPD). The BAME network circulates information on the Workforce Race Equality Standards (WRES) courses for BAME staff (Chatwood, Reference Chatwood2015). There is BAME representation in the workforce at senior level with three out of eight in the leadership team being from BAME backgrounds, although there is more BAME representation at administrative and PWP levels than within Step 3 therapists. We need to consider broader implications for anti-racist practice in recruitment processes and clinical training. There is potential for conformity and confirmation bias (the tendency of people to favour information that confirms their existing beliefs or hypotheses) affecting employment diversity, through senior staff pre-conceived ideas about different social groups which may introduce discrimination (unconscious or otherwise) and impact the recruitment process (Agarwal, Reference Agarwal2018).

If there are less BAME voices in senior positions, diversity of thought in decision making processes may be lacking and there is a distinct lack of power to implement inclusive practices. This is an example of systemic racism. SLaM NHS trust are committed to addressing this. The Psychology and Psychotherapy (P&P) Race Equity working group aims to support projects that involve collaborative working with local community organisations and create an infrastructure for embedding anti-racist practice within the P&P workforce. The group has asked to pool resources with the Patient Carer Race Equality Framework (PCREF) and the Trust BAME Network to ensure that its ambitions are continually informed by the needs and ideas of network members, patients, carers, and the community. Provision of resource and infrastructure from the Chief Executive Officer is imperative to ensure implementation. This would also evidence the commitment SLaM have made to reduce ethnic inequalities in mental health (NHS England, 2020c; Synergi Collaborative Centre, 2020).

Services could consider localised agreements on audit-review frequency, dependent on demonstrative progress towards the BAME PPG required standards. We suggest a traffic light system as a measure, where points allocated to each standard are collated and ranked from red (not met) to amber (working towards) and green (met), for clear identification of gaps to support agreed action plans.

Conclusions

The burden of inequalities is astronomical, and the potential societal, service and individual benefits surpass any investment (NHS England, 2020a). The devastating impact of inequalities caused by racism have been far reaching (Nazroo and Becares Reference Nazroo and Becares2020; Nazroo et al., Reference Nazroo, Bhui and Rhodes2020), highlighting longstanding legacies of oppression within systems. We cannot right the wrongs of the past, but we can work to address the ongoing impact.

The demands of a target driven IAPT service mean it may be difficult to prioritise increasing access for BME communities without appropriate funding. Commissioning bodies have a responsibility to support services by funding frameworks which enable implementation of the BAME PPG 2019, principles of which are mirrored in the recent Advancing Mental Health Equalities strategy (NHS England, 2020c). This is the foundation for the provision of steps forward towards progressive change. This can only be obtained if the recommendations are enforced, learning recorded and next steps implemented. With considerable pressures on aspects of service delivery, a formal integrated framework would support this.

Representation of BAME staff and service users is imperative as we start to address the imbalance in mental health systems (BAME PPG, 2019; BPS, 2020). Targeted inclusive research for people from non-majority populations in the UK context is imperative in informing clinical practice. This also requires decolonisation of clinical curriculums to include teaching on both historical context and the social construct of race in black and white identities, where the re-accreditation process requires teaching programmes to evidence how they embed anti-racist practice throughout all training modules.

This is a call for action for the BABCP membership to step up in development of different strands of work for relevant representative communities that they serve, in support of cultivating community relationships and reciprocal learning. Where there is a shared commitment to be part of the solution, promoting individual and systems growth in development of cultural safety, humility, and intelligence is key. Our boldness in moving into uncomfortable territory will literally save lives. Understanding and accepting the need for anti-racist clinical practice may improve BME service users’ experiences and outcomes in mental health.

Key practice points

-

(1) The evidence presented suggests that NHS England should fund, monitor, and hold commissioning bodies accountable for providing equitable access and outcomes for BME communities.

-

(2) Training on cultural safety and white fragility should be included within clinical courses and NHS mandatory training for all staff including CBT therapists.

-

(3) The use of the BAME PPG audit tool and service Positive Practice BAME working groups should be made compulsory within IAPT services (and equivalent within secondary care mental healthcare) to ensure regular review and assessment.

-

(4) Services should ensure diversity in all recruitment process (e.g. shortlisting panels, interview panel members) in order to support representative workforce recruitment.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

No financial support was received.

Conflicts of interest

Leila Lawton and Melissa McRae are both members of the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies, Equality & Culture Special Interest Group.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not needed for this paper.

Author contributions

Leila Lawton: Conceptualization (Lead), Resources (Lead), Validation (Lead), Visualization (Equal), Writing-original draft (Equal), Writing-review & editing (Lead); Melissa McRae: Conceptualization (Supporting), Resources (Supporting), Validation (Equal), Visualization (Equal), Writing-original draft (Equal), Writing-review & editing (Supporting); Lorraine Gordon: Conceptualization (Supporting), Resources (Supporting), Validation (Supporting), Visualization (Supporting), Writing-original draft (Supporting), Writing-review & editing (Supporting).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.