Introduction

Suicide accounts for an estimated 1.5% of the global burden of disease, with psychiatric disorders contributing to approximately 90% of suicides; mood disorders (primarily major depressive disorder [MDD]) account for approximately 60% of suicides.Reference Mann, Apter and Bertolote 1 A Canadian Community Health Study survey found that in respondents who had MDD, the 12-month prevalence of suicidal ideation, suicide plan, and suicide attempt was 26.9%, 12.0%, and 6.6%, respectively.Reference Patten, Williams and Lavorato 2 Similar estimates were found in the United States (US) National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) study, which reported a 12-month prevalence of suicidal ideation of 26.3% in adults with MDD.Reference Han, McKeon and Gfroerer 3 The 12-month prevalence of suicide attempt among MDD respondents in the NSDUH study varied based on whether they had prior ideation without a suicide plan (4.4%) or with a suicide plan (32.9%).Reference Han, Compton, Gfroerer and McKeon 4 Findings from the NSDUH study were consistent with other studies that found prior suicidal ideation to be strong predictors of subsequent suicide attempt.Reference Oquendo, Galfalvy and Russo 5 – Reference Mundt, Greist and Jefferson 7

In patients who have suicidal ideation or behavior as part of their MDD symptomatology, antidepressants can help to reduce these symptoms. However, there is ongoing concern about the emergence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors as an adverse effect of treatment. For example, although antidepressant clinical trials typically exclude patients who may be at risk for suicide, suicide-related events still occur, albeit at very low incidences.Reference Acharya, Rosen and Polzer 8 – Reference Baldwin, Chrones and Florea 10 Based on meta-analyses of clinical trials conducted in pediatric populations and younger adults (18–24 years of age),Reference Hammad, Laughren and Racoosin 11 , Reference Stone, Laughren and Jones 12 a black-box warning for increased risk of suicidal ideation and behavior in these populations is now required by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for all approved antidepressants. The relationship between antidepressants and treatment-emergent suicidality in older adults is less clear. Some meta-analyses have found an increased risk of suicidality with antidepressants, particularly with older serotonin reuptake inhibitors,Reference Fergusson, Doucette and Glass 13 – Reference Rubino, Roskell and Tennis 15 while other meta-analyses found no increased risk of suicide-related events in older adults.Reference Stone, Laughren and Jones 12 , Reference Khan, Khan, Kolts and Brown 16 Nonetheless, prescribing information for FDA-approved antidepressants generally recommends that all patients treated with these medications continue to be monitored for the emergence of suicidal thoughts or behaviors.

Despite the understandable desire to warn clinicians, patients, and the general public about the serious possibility of treatment-related suicidality, the FDA black-box warning may have had some unintended consequences. A study using data from 11 geographically distributed US healthcare organizations found that in the second year following implementation of the FDA warning, the relative decrease in antidepressant use was 24.3% in young adults (18–29 years of ages) and 14.5% in adults (30–64 years).Reference Lu, Zhang and Lakoma 17 In the same time frame, the relative increase in suicide attempts (as measured by nonfatal drug poisoning) was 33.7% in young adults and 5.2% in adults, which may have been an underestimate since other suicidal behaviors were not included in the analysis. The results of this study suggest that media coverage of the FDA warning may have had unforeseen negative effects, and as the authors of the study conclude, more research and better education are needed to clarify both the risks and benefits of antidepressant treatment in patients who require such therapy.

One such effort has been the development of an FDA consensus statement that emphasizes the importance of differentiating between suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior in pharmacotherapy clinical trials.Reference Meyer, Salzman and Youngstrom 18 The consensus statement adheres to recommendations of the Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA) and endorses use of the validated Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) in clinical trials. The C-SSRS was specifically developed to quantify the severity of suicidal ideation and behavior following C-CASA guidelines.Reference Posner, Oquendo and Gould 19 , Reference Posner, Brown and Stanley 20 As recommended, the C-SSRS was used in addition to adverse event (AE) reporting to monitor suicidal ideation and behavior in 4 US clinical trials of levomilnacipran extended-release (ER),Reference Asnis, Bose and Gommoll 21 – Reference Sambunaris, Bose and Gommoll 24 a selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that is approved for the treatment of MDD in adults. Since it is difficult to ascertain the effects of any medication on relatively uncommon events such as suicidal ideation or behavior,Reference Stone, Laughren and Jones 12 the AE and C-SSRS data from these trials were pooled to examine suicidality from a larger sample of patients. Post hoc analyses of these pooled data were conducted to investigate the emergence of treatment-related suicidal ideation and behavior in adults with MDD.

Methods

Clinical studies

Post hoc analyses were conducted using data from 4 short-term trials and 1 long-term, open-label extension study of levomilnacipran ER in adults with MDD. Methods for these studies have been previously reported.Reference Asnis, Bose and Gommoll 21 – Reference Mago, Forero and Greenberg 25

The 4 short-term, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies were conducted at multiple study sites throughout the US. They included 2 fixed-dose trials (40, 80, or 120 mg/d [NCT00969709Reference Asnis, Bose and Gommoll 21 ]; 40 or 80 mg/d [NCT01377194Reference Bakish, Bose and Gommoll 22 ]) and 2 flexible-dose trials (40-120 mg/d [NCT00969150Reference Gommoll, Greenberg and Chen 23 and NCT01034462Reference Sambunaris, Bose and Gommoll 24 ]) in which patients received 8 weeks of double-blind treatment. Eligible patients from 3 of these studiesReference Asnis, Bose and Gommoll 21 , Reference Gommoll, Greenberg and Chen 23 , Reference Sambunaris, Bose and Gommoll 24 participated in the long-term, open-label extension study (NCT01034267Reference Mago, Forero and Greenberg 25 ) in which they received 48 weeks of flexible-dose treatment with levomilnacipran ER (40–120 mg/d).

All of the short-term studies included men and women, ages 18 to 80 years, who met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria for MDD. All patients were required to have a current major depressive episode and a Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total sore≥30Reference Asnis, Bose and Gommoll 21 , Reference Gommoll, Greenberg and Chen 23 , Reference Sambunaris, Bose and Gommoll 24 or≥26.Reference Bakish, Bose and Gommoll 22 Patients with a DSM-IV-TR–based diagnosis of an Axis I disorder other than MDD within 6 months prior to screening were ineligible for study entry. Other key exclusion criteria were history of nonresponse to ≥2 antidepressants after adequate treatment duration at recommended dosages and current suicide risk, based on suicide attempt within the past year, score≥5 on MADRS suicidal thoughts item, C-SSRS responses, and/or investigator judgment.

Post hoc analyses

Post hoc analyses of the short-term studies were conducted in the pooled safety population, defined as all randomized patients who received≥1 dose of double-blind study medication. All levomilnacipran ER dosage groups were pooled for these analyses, with no inferential statistics conducted for comparisons between levomilnacipran ER and placebo. Some analyses were also conducted in the long-term safety population, which included all patients in the extension study who received≥1 dose of open-label treatment.

The incidence of suicidal ideation and behavior was summarized for the pooled and long-term safety populations. For suicide-related treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), incidence was analyzed based on the following Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA)–preferred terms: completed suicide, depression suicidal, intentional overdose (or overdose), intentional self-injury, multiple drug overdose intentional, poisoning deliberate, self-injurious behavior, self-injurious ideation, suicidal behavior, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt. For C-SSRS–based incidences, suicidal ideation was defined as a “yes” response in any ideation category (C-SSRS score of 1–5); suicidal behavior was defined as a “yes” response in any behavior category (C-SSRS score of 6–10). The incidence of suicidal ideation or behavior was based on each patient’s maximum C-SSRS score during treatment (ie, at any study visit). In addition to overall incidence, C-SSRS suicidal ideation in the short-term studies was summarized at all double-blind study visits in patients with available assessments at each respective visit; this analysis was conducted in the pooled safety population and in a subgroup of younger adult patients (≤24 years of age).

C-SSRS shifts were analyzed in the pooled safety population and in younger adults based on each patient’s C-SSRS score at baseline and maximum C-SSRS score during double-blind treatment. The shifts were classified as follows: no change (eg, no suicidal ideation/behavior [score of 0] at baseline and throughout treatment); worsening (eg, shift from suicidal ideation [score of 1–5] at baseline to suicidal behavior [score of 6–10]); and improvement (eg, shift from suicidal ideation at baseline [score of 1–5] to no ideation/behavior [score of 0]). Analyses were also conducted using 2 definitions from the C-SSRS Scoring and Data Analysis Guide (C-SSRS Guide)Reference Nilsson, Suryawanshi and Gassmann-Mayer 26 : (1) treatment-emergent suicidal ideation, defined as any suicidal ideation score during double-blind treatment that was greater than the baseline C-SSRS score; and (2) emergence of serious suicidal ideation, defined as an increase from a baseline score of 0 to a maximum score of 4–5 at any time during treatment. The C-SSRS shift and C-SSRS Guide analyses were limited to patients whose baseline scores were based on recent history (ie, not lifetime history).

Results

Patients

In the pooled safety population, patient demographics were generally similar between the placebo and levomilnacipran ER groups (Table 1). Based on self-reported psychiatric history, 13.0% (268/2066) of patients had attempted suicide at some point in their lifetime; no patient had attempted suicide for at least 1 year prior to study entry. C-SSRS assessments at screening indicated that 50.3% (1039/2066) had a lifetime history of suicidal ideation and 19.2% (396/2066) had a lifetime history of suicidal behavior, which was consistent with the high percentage of patients (>80%) with recurrent depressive episodes.

Table 1 Patient demographics and baseline characteristics (pooled safety population)

a Range reflects the minimum and maximum ages of patients in this pooled study population.

C-SSRS, Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale; ER, extended-release; MDD, major depressive disorder; SD, standard deviation.

Incidence of suicidal ideation and behavior

No suicide-related TEAE occurred in≥1% of patients who received placebo or levomilnacipran ER, either during short-term or long-term treatment (Table 2). Per investigator judgment, 4 patients with a TEAE of “suicidal ideation” (1 placebo, 3 levomilnacipran ER) and 1 patient with “suicidal behavior” (preparatory acts) were withdrawn from the short-term studies. One patient receiving levomilnacipran ER with TEAEs of “suicide attempt” and “intentional overdose” was also withdrawn. In the open-label extension study, 2 patients with a TEAE for “suicidal ideation” and 4 patients with “suicide attempt” (including 2 patients with “overdose”) were discontinued from the study.

Table 2 Incidence of suicidal ideation or behavior (pooled safety population and long-term safety population)

a Patients were only counted once within each MedDRA preferred term. None of the following preferred terms were reported by patients in either treatment group during double-blind treatment in the acute studies or during open-label treatment with levomilnacipran ER in the long-term extension study: completed suicide, depression suicidal, intentional self-injury, multiple drug overdose intentional, poisoning deliberate, self-injurious behavior, or self-injurious ideation.

b For the extension study, TEAEs included adverse events that were not present before the first dose of double-blind treatment in the lead-in study, or that were present before the first dose of double-blind treatment in the lead-in study, but that increased in intensity following the first dose of long-term, open-label treatment.

c Overdose not specified as intentional or accidental in the extension study.

d Only the most severe ideation type and the most severe suicidal behavior across all visits during the double-blind treatment period (randomized controlled trials) or open-label treatment period (extension study) were counted for each patient.

C-SSRS, Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale; ER, extended-release; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

The incidence of any C-SSRS suicidal ideation during double-blind treatment was similar between the placebo and levomilnacipran ER groups (22.2% and 23.9%, respectively); the incidence was not higher in the long-term open-label treatment with levomilnacipran ER (Table 2). The incidence of any suicidal behavior was <0.5% in all treatment groups, including long-term levomilnacipran ER. No completed suicides occurred during any of the studies.

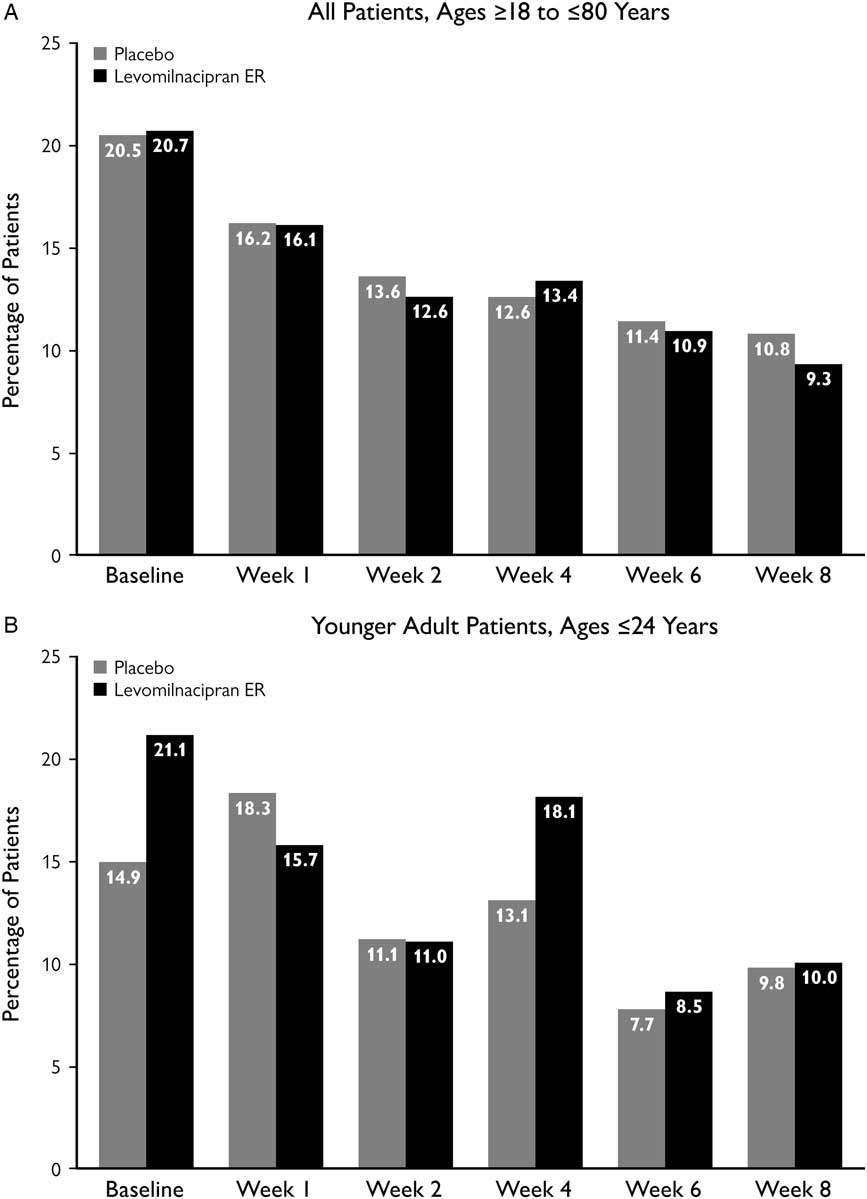

The incidence of C-SSRS suicidal ideation in the pooled safety population decreased steadily over the course of double-blind treatment with both levomilnacipran ER and placebo (Figure 1A). No similar pattern was detected in younger adult patients, although the incidence of suicidal ideation was lower at Week 8 than at baseline in both treatment groups (Figure 1B).

Figure 1 Incidence of C-SSRS suicidal ideation at study visits. Suicidal ideation was defined as a C-SSRS score of 1–5. Analyses were conducted in all patients from the pooled safety population and in a subset of younger adult patients, based on available C-SSRS assessments for each respective study visit. C-SSRS, Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale; ER, extended-release.

Analyses of C-SSRS category shifts

In both treatment groups of the pooled safety population, approximately 90% of patients who had a C-SSRS score of 0 at baseline continued to have no suicidal ideation/behavior throughout double-blind treatment (Table 3). Shifting from a baseline score of 0 to a maximum score of 1-5 during double-blind treatment (ie, worsening from no ideation/behavior to suicidal ideation) occurred less frequently in both treatment groups than shifting from a score of 1–5 to a score of 0 (ie, improvement from suicidal ideation to no ideation/behavior). A similar pattern of results was seen in the subset of younger adults (≤24 years).

Table 3 C-SSRS category shiftsFootnote a

a Categories defined as follows based on C-SSRS scores: no suicidal ideation/behavior (score=0); suicidal ideation (score=1–5); suicidal behavior (score=6–10).

b Number of patients with a relevant baseline C-SSRS score (based on recent history only) and≥1 available post-baseline C-SSRS assessment.

C-SSRS, Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale; ER, extended-release; n=number of patients with available baseline and≥1 post-baseline C-SSRS assessment.

One patient in each treatment group shifted from a baseline score of 0 to a maximum score of 6–10 during double-blind treatment (ie, worsening from no suicidal ideation to suicidal behavior). The levomilnacipran ER patient who met the criteria for this shift was in the younger age group; the placebo patient was not.

Analyses based on C-SSRS Guide definitions

In the pooled safety population, the incidence of treatment-emergent suicidal ideation (ie, any worsening in suicidal ideation score among patients with baseline C-SSRS score of 0–4) was 10.5% and 12.6% for placebo and levomilnacipran ER, respectively. In younger adults, the incidence for placebo and levomilnacipran ER was 13.4% and 15.6%, respectively.

The incidence of emergent serious suicidal ideation (ie, baseline C-SSRS score of 0 and maximum score of 4–5 during double-blind treatment) was 0.3% for both placebo and levomilnacipran ER. One of these patients (treated with levomilnacipran ER) was≤24 years old.

Discussion

Analyses of pooled data from 4 short-term, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials suggest that therapy with levomilnacipran ER was not associated with an increased risk of suicidal ideation or behavior in adults with MDD who were not at risk for suicide prior to treatment. The incidence of suicide-related TEAEs in the pooled safety population was low and similar between the placebo and levomilnacipran ER groups (<1% for any TEAE in both groups), although it is possible that suicide-related TEAEs were under-reported in all treatment groups. These results were consistent with findings from an FDA-sponsored meta-analysis that included 372 randomized and placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants from different classes.Reference Stone, Laughren and Jones 12 In this meta-analysis, any suicidal ideation or behavior (suicide preparation, attempt, or completion) was reported in <1% of patients with major depression (placebo, 0.8%; antidepressant, 0.7%), with the estimated odds ratio (OR) for these events indicating a lower risk with antidepressants, although the comparison was not statistically significant (OR=0.85; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.67–1.07; P=0.16). Statistical analyses were not conducted for the data presented in this report, but it would be surprising if there were any statistical differences between levomilnacipran ER and the placebo for the low incidences of suicide-related TEAEs found in these pooled studies (Table 2).

One issue raised by the FDA meta-analysis is that long-term antidepressant treatment may have a different effect on suicide-related events than acute treatment, with maintenance treatments potentially providing protective effects that would reduce the long-term risk of suicidal ideation and behavior.Reference Stone, Laughren and Jones 12 It is difficult to draw definitive conclusions based on data from a single open-label study, but the incidence of suicide-related TEAEs in patients who received 48 weeks of levomilnacipran ER at flexible doses (<1% for any TEAE) was similar to those found in patients who received acute treatment with either levomilnacipran ER or placebo. The results were also similar to those of other long-term antidepressants,Reference Baldessarini, Lau and Sim 27 but much more research is needed to better understand how medications used for relapse prevention or the treatment of chronic MDD may affect the risk of suicidal ideation or behavior.

In accordance with FDA safety guidelines,Reference Meyer, Salzman and Youngstrom 18 the C-SSRS was used along with AE reporting to monitor suicidality. To capture the most severe ideation or behavior experienced by each patient, incidence was based on the maximum C-SSRS score reported at any study visit during treatment. The incidence of C-SSRS suicidal ideation was similar between placebo and levomilnacipran ER (22.2% and 23.9%, respectively) in the short-term studies; a similar incidence for levomilnacipran ER (21.7%) was observed in the long-term study. In all of these treatment groups, however,>95% of the patients with suicidal ideation had C-SSRS scores of 1–3, representing a general wish to be dead, active but nonspecific suicidal thoughts, or active suicidal thoughts without methods or intent to act. Serious suicidal ideation (as defined in the C-SSRS GuideReference Nilsson, Suryawanshi and Gassmann-Mayer 26 as scores of 4-5) and suicidal behavior (C-SSRS scores of 6–10) were found in<1% of patients in the short-term studies (levomilnacipran ER or placebo) and in <1% of patients in the long-term study. Comparing the incidences of suicidal ideation and behavior based on C-SSRS responses and AE reporting points to the differences in these methodologies. As intended, the C-SSRS provided a more granular perspective on the types of suicidal thoughts and behaviors that patients experienced during antidepressant treatment. Especially for nonserious suicidal ideation, the C-SSRS was more sensitive in the levomilnacipran ER studies for detecting the suicide-related events, possibly due to patients being prompted to talk about suicidality in contrast to being asked a general question about adverse effects. From a clinical standpoint, these findings suggest that using explicit language to monitor suicidality may help increase awareness of nonspecific and nonintentional suicidal ideation before such thoughts become more severe and possibly develop into suicidal behaviors.

As there is an ongoing concern about increased risks of treatment-emergent suicidality in younger adults,Reference Stone, Laughren and Jones 12 we took a close look at C-SSRS results in patients who were≤24 years of age. The results from these analyses generally indicate that treatment with levomilnacipran ER did not pose a greater risk of suicidal ideation or behavior in younger adults. Over the course of double-blind treatment, younger adult patients in the levomilnacipran ER studies did not have the same pattern of steady decline in incidence of C-SSRS suicidal ideation as was seen in the overall pooled safety population (Figure 1). However, despite an increase at Week 4 with levomilnacipran ER (18.1%) in younger adults, the overall decline in incidence from baseline to Week 8 was somewhat larger in the levomilnacipran ER group (21.1% to 10.0%) than in the placebo group (14.9% to 9.8%). Given the relatively small number of younger patients (placebo, n=67; levomilnacipran ER, n=128), it is difficult to draw any strong conclusions about this subgroup. However, the increase at Week 4 with levomilnacipran ER suggests that clinicians may want to be especially vigilant during the first few weeks of treatment in their monitoring of suicidal ideation. Although the Week 4 increase in younger adults mostly represented patients with nonspecific and nonintentional suicidal thoughts (C-SSRS score of 1–3), it did include a few patients with active suicidal ideation (with intent and plan). Identifying such patients—even if relatively few in number—is extremely important, since those with a plan are much more likely to attempt suicide than those without a plan.Reference Han, Compton, Gfroerer and McKeon 4

Analyses based on C-SSRS category shifts also indicated that the risk of suicidal ideation and behavior was not greater with levomilnacipran ER than with placebo. In fact, a higher percentage of levomilnacipran ER–treated patients improved from suicidal ideation at baseline (C-SSRS score of 1–5) to no ideation/behavior (C-SSRS score of 0) during double-blind treatment, although the absence of statistical testing and the very small sample size in younger patients (n=37) needs to be considered when interpreting these results.

The analyses based on C-SSRS Guide definitions for treatment-emergent suicidal ideation and emergence of serious suicidal ideation were conducted to evaluate whether patients treated with levomilnacipran ER had a general worsening in suicidal thoughts or sudden development of active suicidal thoughts with intent and possible plan. The percentage of patients who met either of these definitions was similar between levomilnacipran ER and placebo in the pooled safety population and in the younger adult patients. The incident of emergent serious suicidal ideation was 0.3% in both treatment groups, which was consistent with AE reporting for suicidal ideation (also 0.3% of patients both treatment groups). Again, although these percentages only represent a small number of patients, they highlight the need to actively elicit information about suicidal thoughts and to pay attention to any voluntary information provided by patients regarding such thoughts. In these cases, a careful assessment of each patient’s individual situation is needed to decide upon an optimal course of action, such as adding or increasing behavioral therapy, changing dosage of the current medication, or switching to a different class of antidepressant drugs.

Limitations

Although pooling data from multiple studies allows for post hoc analysis of a bigger sample, assessing the risk of suicidality based on uncommon TEAEs such as suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior is challenging.Reference Stone, Laughren and Jones 12 , Reference Meyer, Salzman and Youngstrom 18 However, implementation of the C-SSRS in the levomilnacipran ER trials helped to provide a broader perspective on suicide-related events, mostly by helping to identify patients with nonspecific and nonintentional suicide ideation. Monitoring suicidal thoughts and behaviors with this instrument resulted in higher incidences of any suicidal ideation (C-SSRS score of 1–5) relative to AE reporting in both treatment groups, but the similarity between levomilnacipran ER and placebo for C-SSRS suicidal ideation supported the overall conclusion that suicide-related events were not more common with active treatment.

The findings presented in this report are also limited by the exclusion of patients who were judged to be at-risk for suicide at screening, patients with concurrent major psychiatric disorders, and patients with alcohol/substance abuse disorders. Therefore, no conclusions can be drawn regarding the effects of levomilnacipran ER on suicidal ideation or behavior in these types of patients. In addition, no adjustments were made for other factors that might affect suicidal risks, such as demographics (sex, age), MDD history (age of onset, number of major episodes, prior hospitalizations), socioeconomic status (income, employment, education), religion, family history, and childhood trauma.Reference Borges, Nock and Haro Abad 28 – Reference Lawrence, Oquendo and Stanley 32 Given the small number of reported suicide-related events in the levomilnacipran ER studies, adjusting for such factors would probably not have been meaningful. However, continued research in the general population or with much larger databases is warranted to better understand how these factors affect the relationship between antidepressant treatment and suicide, both in terms of risk and potential benefits.

Conclusions

Based on both AE reporting and C-SSRS scores from 4 short-term, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, the incidences of suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior were similar between levomilnacipran ER 40–120 mg/d and placebo in adults with MDD. Suicidal ideation and behavior did not occur more frequently in the long-term, open-label extension study of levomilnacipran ER 40–120 mg/d. Analyses based on shifts in C-SSRS scores and C-SSRS Guide definitions also indicated similar results between patients treated with short-term levomilnacipran ER and those who received placebo. Younger adult patients did not appear to have a greater risk of suicidal ideation or behavior as compared with the overall pooled safety population. However, regular monitoring of all patients, regardless of age, is recommended throughout treatment.

Disclosures

M. E. Thase has the following disclosures: Alkermes, consultant, personal fees; AstraZeneca, consultant, personal fees; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, consultant, personal fees; Eli Lilly & Co., consultant, grant recipient, grant/personal fees; Forest Laboratories, consultant, grant recipient, grant/personal fees; Gerson Lehman Group, consultant, personal fees; GlaxoSmithKline, consultant, personal fees; Guidepoint Global, consultant, personal fees; H. Lundbeck A/S, consultant, personal fees; MedAvante, consultant, personal fees, equity holdings; Merck and Co., consultant, personal fees; Neuronetics, Inc., consultant, personal fees; Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals, consultant, personal fees; Otsuka, consultant, grant recipient, grant/personal fees; Pfizer, consultant, personal fees; Roche, consultant, personal fees; Shire US, Inc., consultant, personal fees; Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., consultant, personal fees; Takeda, consultant, personal fees; American Psychiatric Foundation, royalties; Guilford Publications, royalties; Herald House, royalties; W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., royalties; Peloton Advantage, spouse’s employment; Cerecor, Inc., consultant, personal fees; Moksha8, consultant, personal fees; Pamlab, L.L.C. (Nestle), consultant, personal fees; Allergan, consultant, personal fees; Trius Therapeutical, Inc., consultant, personal fees; Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Inc., consultant, personal fees. A. Khan has been a principal investigator in more than 380 clinical trials sponsored by more than 65 pharmaceutical companies. He has not received any compensation as a consultant or speaker, nor does he own stock in any of these or other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Khan has not been compensated for his role as an author on this or any other publication. C. Gommoll, C. Chen, K. Kramer, and S. Durgam are full-time employees of Allergan. Forest Research Institute, an Allergan affiliate, sponsored the clinical studies that are included in this report.