Introduction

In the region of the Beskid Makowski Mountains, the Outer Western Carpathians, S Poland, biogenic archives of the landslide fens, small mires formed within landslide depressions, contain exceptionally long late glacial minerogenic-organic sequences, reaching up to 2.5–3.5 m of thickness (Margielewski et al. Reference Margielewski, Obidowicz, Zernitskaya and Korzeń2022a). In the Kotoń landslide fen, lithological, pollen, plant tissue and carpological analyses and radiocarbon dating carried out during the previous studies revealed a distinct lacustrine-mire record of the Bølling-Older Dryas-Allerød transition (Margielewski Reference Margielewski2001; Margielewski et al. Reference Margielewski, Obidowicz and Pelc2003). Palynologically-determined local chronozones could not be, however, validated due to the lack of a detailed calibrated age scale. The importance of accurate age-depth model for the palynological profiles in the Carpathians is thoroughly recognized (Michczyński et al. Reference Michczyński, Kołaczek, Margielewski and Michczyńska2013), also in respect to the possibility of conducting more extensive extraregional correlations (Margielewski et al. Reference Margielewski, Michczyńska, Buczek, Michczyński, Korzeń and Obidowicz2022b).

Traditionally, for the late glacial period Bølling and Allerød climate warmings are separated by a short (ca. 100–200 years) climate cooling of the Older Dryas, a succession based on biostratigraphic record of the Scandinavia region (Iversen Reference Iversen1954). Later these phases were also adopted as formal chronozones for this part of Europe, assigning to the Bølling Chronozone (including the Oldest Dryas interval) time boundaries from 13.0 to 12.0 k uncal BP, to the Older Dryas Chronozone from 12.0 to 11.8 k uncal BP and to the Allerød Chronozone from 11.8 to 11.0 k uncal BP (Mangerud et al. Reference Mangerud, Andersen, Berglund and Donner1974). The classical stratigraphic subdivision of the late glacial across different regions of Europe seems to be, however, strongly diverse and problematic (De Klerk Reference De Klerk2004; Van Raden et al. Reference Van Raden, Colombaroli, Gilli, Schwander, Bernasconi, van Leeuwen, Leuenberger and Eicher2013). For example, the Older Dryas climatic deterioration is very weak or absent in the palaeo-records from the British Isles, therefore Bølling and Allerød are considered there as a single interstadial whereas separation of the Older Dryas is questioned (Watts Reference Watts, Lowe, Gray and Robinson1980). Similar problem with the Older Dryas distinction was recognized for the Alps, where it could often only be registered at higher altitudes closer to ecotone (Lotter et al. Reference Lotter, Eicher, Siegenthaler and Birks1992; Welten Reference Welten1982).

For the North Atlantic region, GRIP Greenland ice core (event stratigraphy based on the oxygen isotope record) was suggested as a stratotype for the 22.0 to 11.5 k GRIP yr BP (ca. 19.0–10.0 k BP), with recommendation for replacing the classical terminology: “Bølling,” “Older Dryas,” “Allerød,” and “Younger Dryas” with a new scheme (Björck et al. Reference Björck, Walker, Cwynar, Johnsen, Knudsen, Lowe and Wohlfarth1998). In this scheme, the Bølling-Allerød interval seemed to correspond to the Greenland Interstadial 1 (GI-1), dated to 12.65–14.7 k GRIP yr BP, subdivided into three warmer episodes, GI-1a, 1c and 1e, separated by the colder ones, GI-1b and 1d. On the other hand, it was stressed that Greenland ice core chronology should not replace the regional terrestrial stratigraphic divisions but to be used as extraregional reference for them (Litt et al. Reference Litt, Brauer, Goslar, Merkt, Balaga, Müller, Ralska-Jasiewiczowa, Stebich and Negendank2001; Lowe et al. Reference Lowe, Rasmussen, Björck, Hoek, Steffensen, Walker and Yu2008; Van Raden et al. Reference Van Raden, Colombaroli, Gilli, Schwander, Bernasconi, van Leeuwen, Leuenberger and Eicher2013). Although the risk of potential miscorrelation with some other short-lasting late glacial climatic events of the high-resolution oxygen-isotope records from the Greenland ice cores is clearly emphasized (Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Bigler, Blockley, Blunier, Buchardt, Clausen, Cvijanovic, Dahl-Jensen, Johnsen, Fischer, Gkinis, Guillevic, Hoek, Lowe, Pedro, Popp, Seierstad, Steffensen, Svensson, Vallelonga, Vinther, Walker, Wheatley and Winstrup2014), commonly the Bølling climatic oscillation is correlated with GI-1e episode, Older Dryas with GI-1d, and early Allerød with GI-1c (Van Raden et al. Reference Van Raden, Colombaroli, Gilli, Schwander, Bernasconi, van Leeuwen, Leuenberger and Eicher2013). The requirement for such correlation between terrestrial records and Greenland ice core stratigraphy is an independent absolute chronology derived from radiocarbon dates (Lowe et al. Reference Lowe, Rasmussen, Björck, Hoek, Steffensen, Walker and Yu2008), as well as from other dating method e.g. varve chronology (Litt et al. Reference Litt, Brauer, Goslar, Merkt, Balaga, Müller, Ralska-Jasiewiczowa, Stebich and Negendank2001). There is a growing number of the late glacial studies investigating sequences which contain the Bølling-Older Dryas-Allerød transition and attempting to correlate these sequences with the Greenland event stratigraphy (Ammann et al. Reference Ammann, van Leeuwen, van der Knaap, Lischke, Heiri and Tinner2013; Bos et al. Reference Bos, Verbruggen, Engels and Crombé2013, Reference Bos, De Smedt, Demiddele, Hoek, Langohr, Marcelino, Van Asch, Van Damme, Van der Meeren, Verniers, Boeckx, Boudin, Court-Picon, Finke, Gelorini, Gobert, Heiri, Martens, Mostaert, Serbruyns, Van Strydonck and Crombé2017; Dzieduszyńska and Forysiak Reference Dzieduszyńska and Forysiak2019; Feurdean and Bennike Reference Feurdean and Bennike2004; Kołaczek et al. Reference Kołaczek, Gałka, Karpińska-Kołaczek and Lutyńska2015; Litt et al. Reference Litt, Brauer, Goslar, Merkt, Balaga, Müller, Ralska-Jasiewiczowa, Stebich and Negendank2001; Moska et al. Reference Moska, Sokołowski, Jary, Zieliński, Raczyk, Szymak, Krawczyk, Skurzyński, Poręba, Łopuch and Tudyka2022).

Palaeo-records with the Older Dryas climatic oscillation distinguished as a traditional biostratigraphic zone or chronozone (Iversen Reference Iversen1954; Mangerud et al. Reference Mangerud, Andersen, Berglund and Donner1974) based on pollen data are more numerous than those in which Older Dryas is correlated with GI-1d episode of the Greenland event stratigraphy based on absolute chronology. Frequently, in the flat areas of Europe, a former foreland of retreating ice-sheet, some distinct Older Dryas deposits were recorded at localities connected with late glacial aeolian activity, e.g. dunes, sand covers, loess areas (Wasylikowa Reference Wasylikowa1964). It was suggested that vegetation growing on these types of unstable ground may be more prone to climate deterioration (Burdukiewicz et al. Reference Burdukiewicz, Szynkiewicz, Malkiewicz, Kobusiewicz and Kabaciński2007; Latałowa and Nalepka Reference Latałowa and Nalepka1987) e.g. intense winds and give more pronounced response in palynological profiles.

Older Dryas deposits have been also documented in the lacustrine late glacial-Holocene sequences of the Polish Lowlands. In the Lake Gościąż, Older Dryas was marked (however not very distinctively) as a short-lasting cooling phase during which the opening of forest habitats occurred, probably intensifying a shore slumping process and sand deposition (Goslar et al. Reference Goslar, Ralska-Jasiewiczowa, Starkel, Demske, Kuc, Łącka, Szeroczyńska, Wicik, Więckowski, Ralska-Jasiewiczowa, Goslar, Madeyska and Starkel1998; Ralska-Jasiewiczowa et al. Reference Ralska-Jasiewiczowa, Demske, van Geel, Ralska-Jasiewiczowa, Goslar, Madeyska and Starkel1998). Older Dryas climatic oscillation was readily pronounced in palynological profiles of Osłonki palaeo-lake, both as a drop in abundance of tree pollen, an increase in abundance of shrubs and herbaceous plants, as well as a rising number of plant taxa representing wet and aquatic habitats (Nalepka Reference Nalepka2005).

Further toward the East European Plain, the Older Dryas deposits were identified in the bottom of the lacustrine sequences of a few Belarusian lakes (Novik et al. Reference Novik, Punning and Zernitskaya2010; Zernitskaya Reference Zernitskaya1997). In the eastern parts of Poland, in the area of today Puszcza Knyszyńska during the Older Dryas climatic phase high water table conditions prevailed, facilitating the onset of Taboły mire organic succession (Drzymulska Reference Drzymulska2010). For the Wolbrom peatland site located in the Silesian-Cracovian Upland, the influence of Older Dryas climate cooling was recognized, however, the interpretation of the resulting vegetation changes was ambiguous (Latałowa and Nalepka Reference Latałowa and Nalepka1987). In the adjacent region of the Sandomierz Basin, sites with peatland and alluvial deposits revealed only a few mm thick horizon of the Older Dryas phase, characterized by tundra vegetation with sparse tree stands (Nalepka Reference Nalepka1994).

Older Dryas was found in intermontane depressions of the Outer Western Carpathians. In Tarnowiec site (Jasło-Sanok Depression, SE Poland) it comprised several cm of sand-organic sediments, with low concentration of pollen in a bottom part and pollen diagrams suggesting the predominance of a park-woodland landscape and abundance of shrubs and herbs at that time (Harmata Reference Harmata1987). In the Nowy Targ Basin (S Poland), Older Dryas deposits were found within the profile of the raised bog Na Grelu (Koperowa Reference Koperowa1961). Here, it is represented by ca. 35 cm of mineral deposits with pollen assemblage interpreted as the treeless shrub tundra conditions.

Palaeoenvironmental studies of the landslide fen deposits of Klaklowo and Kotoń sites, located in the mid-altitudes of the Beskid Makowski Mountains (the Outer Western Carpathians) revealed the exceptionally thick, ca. 0.5 m, sequence of mineral deposits attributed to the Older Drays climatic phase (Margielewski Reference Margielewski2001; Margielewski et al. Reference Margielewski, Obidowicz and Pelc2003, Reference Margielewski, Michczyńska, Buczek, Michczyński, Korzeń and Obidowicz2022b). In the High Tatras (the Outer Carpathians, S Poland) sedimentological studies from Czarny Staw Gąsienicowy lakes revealed that the pre-Allerød mineral deposits characterized by a massive type of bedding may be attributed to the cooling phases of the Oldest Dryas and the Older Dryas stadials (Baumgart-Kotarba and Kotarba Reference Baumgart-Kotarba, Kotarba and Kotarba1993). The pre-Allerød section of the palynological diagrams exhibits an increase in non-arboreal pollen values connected with open, steppe-tundra conditions and probable occurrence of timberline below the altitude of the Czarny Staw Gąsienicowy lake at that time. With some uncertainty this section was interpreted as the Older Dryas Stadial (Obidowicz Reference Obidowicz and Kotarba1993, Reference Obidowicz1996). More ambiguous are pre-Allerød deposits from Żabie Oko (Baumgart-Kotarba et al. Reference Baumgart-Kotarba, Kotarba and Obidowicz1994), although pollen data also suggest the Older Dryas cooling as a probable time of their accumulation (Obidowicz Reference Obidowicz and Kotarba1993, Reference Obidowicz1996).

In this paper a part of a new multi-proxy results obtained from the Kotoń landslide fen deposits (the Beskid Makowski Mountains, the Outer Western Carpathians, S Poland), including loss on ignition analysis (LOI), plant macrofossil analysis and radiocarbon dating is presented. The aim of the study is:

-

1. to verify whether there is an agreement between reconstructed local palaeoecological stages of the Kotoń fen development (500–300 cm depth interval of the Kotoń sediment sequence) and the Bølling, Older Dryas and the Allerød climatic oscillations defined according to the previous pollen division of the Kotoń fen deposits (Margielewski et al. Reference Margielewski, Obidowicz and Pelc2003) and extraregional absolute chronology of the Greenland ice cores (Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Bigler, Blockley, Blunier, Buchardt, Clausen, Cvijanovic, Dahl-Jensen, Johnsen, Fischer, Gkinis, Guillevic, Hoek, Lowe, Pedro, Popp, Seierstad, Steffensen, Svensson, Vallelonga, Vinther, Walker, Wheatley and Winstrup2014).

-

2. to verify whether the short GI-1d/Older Dryas climate cooling occurring 13,904–14,025 yr BP (Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Bigler, Blockley, Blunier, Buchardt, Clausen, Cvijanovic, Dahl-Jensen, Johnsen, Fischer, Gkinis, Guillevic, Hoek, Lowe, Pedro, Popp, Seierstad, Steffensen, Svensson, Vallelonga, Vinther, Walker, Wheatley and Winstrup2014), being rarely recognised in late glacial sequences across Europe, affected also the regional and local palaeoecological record of the Kotoń landslide fen deposits. If confirmed, Kotoń locality would be considered as a unique and rare occurrence of the Older Dryas deposits not only in a scale of the Carpathians and Poland but also in the scale of Europe, contributing to the better understanding of the short climatic oscillations occurring throughout the late glacial period.

Materials and methods

Site description

Geological and geomorphological setting

The study site is located in the south of Poland, in the Outer Western Carpathians, a mountain group built of the Late Jurassic-Early Miocene flysch rocks (Książkiewicz Reference Książkiewicz and Pożaryski1972) (Figure 1A and 1B). The Kotoń landslide and the peatland filling the landslide’s sub-scarp depression, are situated in the southern slope of the Kotoń massif, belonging to the Beskid Makowski Mountains (Figure 1C). The entire landslide zone developed within the thick-bedded Magura sandstones of the Siary Subunit, Magura Unit (Książkiewicz et al. Reference Książkiewicz, Rączkowski and Wójcik2016; Wójcik and Rączkowski Reference Wójcik and Rączkowski1994). The landslide lies close to the massif crest (the pass between the Mt. Kotoń, 857 m a.s.l., and the Mt. Pękalówka, 835 m a.s.l.) and formed as a result of the development of the upper part of the Rusnaków stream (left tributary of the Krzczonówka stream) (Figure 1C and 1D) (Margielewski Reference Margielewski2001; Margielewski et al. Reference Margielewski, Obidowicz and Pelc2003). Landslide form has a shape of a broad wedge with two linear main scarps (ca. 15–30 m high) and a flat area of the landslide colluvium in between them (Figure 1D and 1E). A longitudinal depression formed at the foot of the western scarp of the Kotoń lanslide (Figure 1D and 1E), limited from the east by elongated colluvial rampart (Figure 1F and 1G). The depression is about 50 m wide, 100 m long and up to 5 m deep, filled up with organic-minerogenic sediments of the Kotoń landslide fen.

Figure 1. Location of the Kotoń landslide fen (purple circle) in Europe (A), the region of the Outer Western Carpathian (B) and the Beskid Makowski Mountains (C); (D) Kotoń landslide zone (outlined with the dotted line) with the position of the Kotoń landslide fen (green solid line), (E) present-day area (green solid line) of the fen with a drilling site (red star); (F) and (G) present-day vicinity of the Kotoń fen (photo by Włodzimierz Margielewski). Sources of basemaps: part (A) https://www.naturalearthdata.com/downloads/10m-cross-blend-hypso/cross-blended-hypso-with-relief-water-drains-and-ocean-bottom/); part (B) digital terrain model DTM https://download.gebco.net/ draped with the basemap of the part (A); part (C) DTM from WCS service https://mapy.geoportal.gov.pl/wss/service/PZGIK/NMT/GRID1/WCS/DigitalTerrainModelFormatTIFF.).

Climate, hydrology and vegetation

Climate of the Beskid Makowski Mountains is moderately warm (mean air temperature: 8.0–8.5°C) with significant amount of precipitation (mean annual sum: 800–1000 mm), influenced by mountainous land relief (Tomczyk and Bednorz Reference Tomczyk and Bednorz2022). Prevailing winds blow from the west to the east and the Kotoń site is located on the leeward slope. Similarly to the adjacent regions, temperature inversions occur in the river valleys. Beside the Rusnaków stream originating in the lower part of the Kotoń landslide, there are no permanent streams flowing down from the head scarp and slopes, although the temporary ones are likely (Figure 1E). Two altitudinal-climatic vegetation belts occur in this region: submontane (< 550 m a.s.l.), with the indicator forest community being the colline form of the Tilio-Carpinetum association, and nowadays covered by secondary grass-rich communities, the so-called oak-hornbeam meadows (Arrhenatherion alliance), and the lower montane vegetation belt (550–870 m a.s.l.), represented by the fertile Carpathian beech forest Dentario glandulosae-Fagetum and by the montane acidophilous beech forest, Luzulo luzuloides-Fagetum with secondary communities of seminatural meadows and pastures (Polygono-Trisetion alliance) (Mirek Reference Mirek, Obidowicz, Madeyska and Turner2013). Mean annual growing season lasts 220–230 days (Tomczyk and Bednorz Reference Tomczyk and Bednorz2022).

Coring and sampling

Sediment core was probed with the INSTORF Russian peat sampler (diameter: 8 cm) from the axial part of the Kotoń sub-scarp depression (49°46'5.12''N; 19°54'12.96''E, 739 m a.s.l., Fig. 1E). Drilling spot was close (0.5 m) to the site which was examined during earlier study (Margielewski Reference Margielewski2001; Margielewski et al. Reference Margielewski, Obidowicz and Pelc2003), however, this time the maximum reached length of the core was greater: 500 cm comparing to the previous 450 cm. Furtherly, the core was sliced into samples in the following scheme: 2.5 cm for the 500–300 cm depth interval and 5 cm for the 300–0 cm depth interval. Samples were subjected to the loss on ignition and plant macrofossil analyses and radiocarbon dating (other multi-proxy analyses will be presented in a separate paper). For the purpose of this study, the depth section of 500–300 cm comprising the Bølling-Older Dryas-Allerød transition was selected.

Radiocarbon dating and age-depth model

Material for Acceleration Mass Spectrometry (AMS) dating was collected during the plant macrofossil analysis from a depth section of 440–77 cm of the sediment core at sampling depths representative for changes in lithology. Below 440 cm botanical remains were insufficient for AMS dating, whereas the depth section above 77 cm (Holocene sediment) was not a target of the current study. For the depth range 440–77 cm well-preserved plant material was identified to species level and multiple macrofossil types were selected for dating, including plant fruits, seeds, leaves and needles.

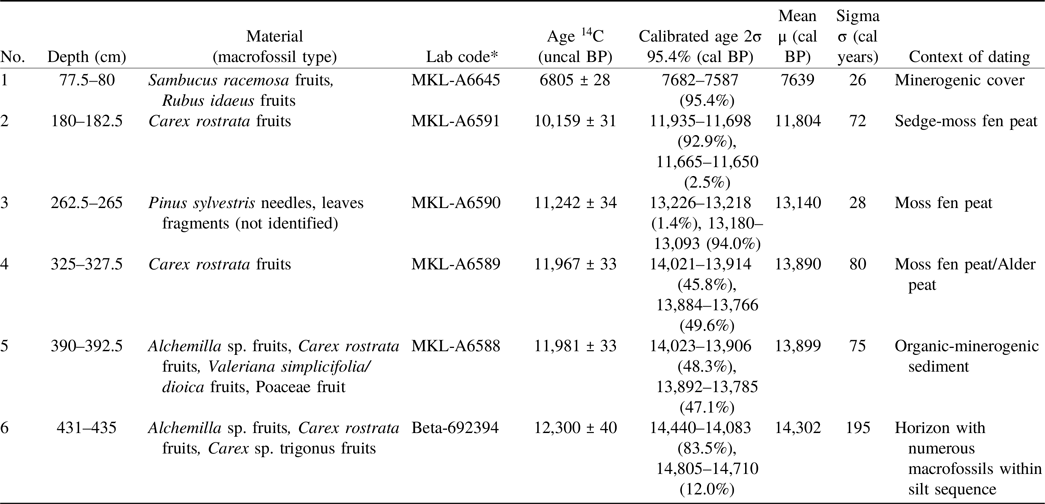

In total, six radiocarbon dates were obtained: five samples were submitted to the Laboratory of Absolute Dating in Kraków, Poland, in collaboration with the Center For Applied Isotope Studies, University of Georgia, U.S.A, whereas one sample of the smallest weight was submitted to Beta Analytic, Inc. Miami, Florida, U.S.A (sample 435–431 cm, Beta-692394). To standardize the calibrated results, the obtained 14C dates BP were further calibrated using the OxCal v. 4.4.4 software (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009, Reference Bronk Ramsey2021) and the IntCal20 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Austin, Bard, Bayliss, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Butzin, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Hajdas, Heaton, Hogg, Hughen, Kromer, Manning, Muscheler, Palmer, Pearson, Van Der Plicht, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Turney, Wacker, Adolphi, Büntgen, Capano, Fahrni, Fogtmann-Schulz, Friedrich, Köhler, Kudsk, Miyake, Olsen, Reinig, Sakamoto, Sookdeo and Talamo2020).

Based on six 14C AMS dates the Bayesian age-depth model was constructed for the Kotoń sediment sequence. The modelling of age-depth curve was conducted in the OxCal v. 4.4.4 software (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009, Reference Bronk Ramsey2021) using the P_sequence function, interpolation = 2 (0.5 cm), parameters k0 = 1 and log10(k/k0) = U(−1,1), with the IntCal20 calibration curve. At a depth of 120 cm a Boundary command was introduced to reflect a significant change in lithology (there is a sudden reduction in values on the loss on ignition curve associated with admixture of silt to sedge-moss fen peat accumulation) and plant macrofossil assemblages (macrofossil data from 300–0 cm are not presented in this paper). A mean (µ) value of the modelled age (values rounded to tens) expressed in cal BP and sedimentation rate expressed in mm year−1, were obtained.

Loss on ignition and peat type

During the loss on ignition analysis (LOI) sediment slices (2.5 cm thick) underwent the ignition process in a muffle furnace at 550°C according to the standard procedure of Heiri et al. (Reference Heiri, Lotter and Lemcke2001). After burning, samples were weighed again in order to determine the loss in organic matter content and the loss on ignition curve (weight loss expressed in %) was plotted. Peat type description was based on the earlier study (Margielewski Reference Margielewski2001; Margielewski et al. Reference Margielewski, Obidowicz and Pelc2003), in which it was carried out by plant tissue analysis and classification of Tołpa et al. (Reference Tołpa, Jasnowski and Pałczyński1967).

Macrofossil analysis and zonation

Disintegrated material was mildly washed with running water through mesh sieve of 200 μm diameter. Macrofossils identification was performed with ZEISS Stemi 508 stereomicroscope at 10–16× magnifications. Macrofossils of plants (fruits, seeds, needles, oospores etc.) and animals (ephippia, statoblasts, gemmules etc.) were recognized according to appropriate atlases, keys and publications (Aalto Reference Aalto1970; Anderberg Reference Anderberg1994; Berggren Reference Berggren1969, Reference Berggren1981; Birks Reference Birks, Elias and Mock2013; Cappers et al. Reference Cappers, Bekker and Jans2012; Kats et al. Reference Kats, Kats and Kipiani1965; Körber-Grohne Reference Körber-Grohne and Haarnagel1964, Reference Körber-Grohne1991; Kowalewski Reference Kowalewski2014; Mauquoy and van Geel Reference Mauquoy, van Geel and Elias2007; Velichkevich and Zastawniak Reference Velichkevich and Zastawniak2006, Reference Velichkevich and Zastawniak2008). Collection of modern diaspores and specimens of fossil flora from the National Biodiversity Collection of Recent and Fossil Organisms stored at W. Szafer Institute of Botany PAS in Kraków (herbarium KRAM) was also used for this purpose. Botanical nomenclature for vascular plants was based on Mirek et al. (Reference Mirek, Piękoś-Mirkowa, Zając and Zając2020) and for mosses (Bryopsida) on Lüth (Reference Lüth2019), phytosociological nomenclature was adopted after Pladias – Database of the Czech Flora and Vegetation, whereas ecological requirements of plants were based mostly on Zarzycki (Reference Zarzycki2002) and other references. Plant taxa representing trees, shrubs and dwarf shrubs were gathered into one group, whereas other vascular plants, Bryopsida and Characeae were grouped according to habitat moisture level (dry, fresh and moist, mire and aquatic), also in order to better present the terrestrial and aquatic vegetation successions. Taxa of animal and other remains were put into group named Others. All data were plotted on the macrofossil diagram using Tilia software (Grimm Reference Grimm1991) as absolute macrofossil counts per sample volume (8.0−24.0 cm3, mean: 15.80 cm3). In case of Bryopsida, relative abundances of identified species were expressed as percentage of the total amount of well-preserved moss stems and presented as Bryopsida composition in the sub-section of the macrofossil diagram.

Zonation of the Kotoń sediment sequence was carried out for macrofossil data (absolute counts standardized to the same volume 16 cm3, excluding Bryopsida species expressed in percentages), using constrained incremental sum of squares cluster analysis (CONISS, Grimm Reference Grimm1987). The broken stick model (Bennett Reference Bennett1996) was used to establish the number of statistically significant zones. Cluster analysis was conducted in R version 4.2.2 (R Core Team Reference Core Team2022) and using package Rioja (Juggins Reference Juggins2022). The final depth ranges of the palaeoecological stages of development were determined based on cluster analysis results and visual inspection of the macrofossil diagram.

Results and discussion

Absolute chronology and sedimentation rate

The obtained uncalibrated and calibrated AMS radiocarbon dates are presented in Table 1. The agreement index Amodel of the Kotoń age-depth model equals 91% and it is greater than the recommended minimum of 60% for the model robustness (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009), therefore the calculated age-depth model can be regarded as reliable (Figure 2). According to the obtained chronology, the accumulation of the Kotoń fen sediment sequence could begin some time before 12,300 ± 40 uncal BP or 14,805–14,083 cal BP (2σ)—this AMS date corresponds to the depth of 435–431 cm, whereas the age of the underlying deposits (down to 500 cm) cannot be established due to the lack of organic material for dating. The uppermost AMS sample is dated to 6805 ± 28 uncal BP or 7682–7587 cal BP (2σ), however, as in the current paper the investigated depth section is 500–300 cm, the “shallowest” considered sample is 325–327.5 cm and it is dated to 11,967 ± 33 uncal BP or 14,021–13,766 cal BP (2σ). Modelled mean date for a depth of ca. 432 cm (approximately the lowermost AMS date) is 14,240 ± 103 cal BP, whereas the modelled mean date for the depth 300 cm is 13,450 ± 115 cal BP. Taking these timeframes into consideration, the accumulation of deposits representing 500–300 cm depth interval lasted more than ca. 800 cal years. Uncertainty (σ) values of the Kotoń age-depth model are the following: 127–39 cal years in the lowest part (440–391 cm, clastic material accumulation), 38–76 cal years in the middle part (391–326 cm, moss fen peat accumulation) and 76–115 cal years in the uppermost part (326–300 cm, moss fen peat accumulation). The sedimentation rate varies throughout the abovementioned depth intervals from the medium 1.2–1.6 mm yr−1 in the lowest part, through the highest: 2.8–3.0 mm yr−1 in the middle part, to the lowest: ca. 1.0 mm yr−1 in the uppermost part (Figure 2).

Table 1. Results of radiocarbon dating of the Kotoń landslide fen deposits. * – MKL: Laboratory of Absolute Dating in Kraków, Poland, in collaboration with the Center For Applied Isotope Studies, University of Georgia, U.S.A.; Beta: Beta Analytic, Inc. Miami, Florida, U.S.A. Calibration conducted in OxCal v4.4.4 Bronk Ramsey (Reference Bronk Ramsey2021) with IntCal20 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Austin, Bard, Bayliss, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Butzin, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Hajdas, Heaton, Hogg, Hughen, Kromer, Manning, Muscheler, Palmer, Pearson, Van Der Plicht, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Turney, Wacker, Adolphi, Büntgen, Capano, Fahrni, Fogtmann-Schulz, Friedrich, Köhler, Kudsk, Miyake, Olsen, Reinig, Sakamoto, Sookdeo and Talamo2020). Selection and identification of plant macrofossils for AMS dating was done by Jolanta Pilch and Renata Stachowicz-Rybka

Figure 2. From left: core photo and lithological column of the Kotoń fen deposits, loss on ignition curve, uncalibrated 14C ages of sediment samples, age-depth model, mean (µ) value of the modeled 14C age and sedimentation rate. The shaded area shows time range of the GI-1d/Older Dryas (OD) climatic oscillation.

Loss on ignition and peat type

The results of the loss on ignition analysis and peat type descriptions are given in Figure 2 and Supplementary Material-Table 1. In general, the investigated section of the Kotoń profile consists of minerogenic material (silt with different admixtures) showing low LOI values (ca. <10%) in a depth interval of 500–405 cm and organic deposits (mostly moss fen peat) with LOI values growing up to ca. 85% in the 405–300 cm depth interval. The detail interpretation of the LOI and peat type results along with other proxies is given in Table 2 and Figure 4.

Table 2. Palaeoecological stages of the Kotoń landslide fen development

Macrofossil data and palaeoecological stages of the Kotoń landslide fen development

Four palaeoecological stages KT-1 to KT-4 (with two substages for stage 1 and 4) for the depth interval 500–300 cm of the Kotoń sediment sequence were eventually determined. Detail description of macrofossil assemblages of these zones is given in Supplementary Material-Table 1, whereas macrofossil diagram is presented in Figure 3. The detail palaeoecological interpretation of the stages is given in Table 2 and Figure 4.

Figure 3. Macrofossil diagram of the depth section 500–300 cm of the Kotoń landslide fen deposits divided into two lines. Values are absolute counts per sample (sample volumes presented on the left), except for the Bryopsida composition (percents). In case of Bryopsida stems fragments and Characeae oospores, due to their great abundancies, the total number presented in the diagram is a sum a number of stems/oospores counted in the uniform part of a sample and a number of stems/oospores estimated visually in remaining part of the sample. The shaded area shows time range of the GI-1d/Older Dryas (OD) climatic oscillation.

Figure 4. Stages of the palaeoecological development inferred for the Kotoń landslide fen deposits (500–300 cm depth interval) in correlation with previous pollen-based chronozones of Kotoń, Greenland ice cores event stratigraphy and stages of local and regional palaeoenvironmental development from various localities across Europe in which correlation with Greenland ice cores was used. The shaded area shows time range of the GI-1d/Older Dryas (OD) climatic oscillation.

Older dryas (GI-1d) in the Kotoń and other palaeo-records possessing absolute chronologies

In general, the Older Dryas climatic oscillation was related to the reappearance of cold and dry continental climate. In the Kotoń sediment sequence, during the stage KT-2 the inferred climatic conditions around the Kotoń waterbody seem to be arctic/alpine (Figure 3, Table 2). Within the Kotoń waterbody itself, development of the aquatic organisms’ successions with Bryopsida dominated by Sarmentypnum trichophyllum is indicative for the occurrence of littoral zone presumably resulting from the shallowing of the lake existing during the stage KT-1 (GI-1e/Bølling). On the other hand, if no deeper lake existed during the stage KT-1, the aquatic conditions of the stage KT-2 could be explained by low temperatures and related low evapotranspiration occurring under cold and dry conditions (low precipitation), which allowed a shallow waterbody to persist.

Stage KT-2 lasted from ca. 14,070 ± 72 to ca. 13,900 ± 56 cal BP (ca. 170 years), what also correspond well to a short GI-1d/Older Dryas climate cooling occurring 14,025–13,904 yr BP according to the Greenland ice cores event stratigraphy (Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Bigler, Blockley, Blunier, Buchardt, Clausen, Cvijanovic, Dahl-Jensen, Johnsen, Fischer, Gkinis, Guillevic, Hoek, Lowe, Pedro, Popp, Seierstad, Steffensen, Svensson, Vallelonga, Vinther, Walker, Wheatley and Winstrup2014). Plant formations of the Kotoń fen surrounding inferred for each of the palaeoecological stages (with some exception for KT-1 which probably records the local conditions of the landslide) stay in agreement with the earlier pollen-based chronozones (Margielewski et al. Reference Margielewski, Obidowicz and Pelc2003) (Figure 4): Bølling characterized by park tundra with Betula and Pinus corresponds to KT-1a and 1b, Older Dryas represented by grass-shrub tundra is related to KT-2 and KT-3, and Allerod-1 characterized by the immigration of Pinus and Betula forest corresponds to KT-4a and 4b. A slight discrepancy in the depth extent between pollen-based Older Dryas chronozone and macrofossil-based stage KT-2 (GI-1d/Older Dryas climate cooling according to NGRIP event stratigraphy) could be explained by the fact, that these two datasets were obtained from two different sediment cores, located however close to each other (0.5 m between drilling spots). Moreover, the specificity of macrofossil and pollen method must be taken into consideration, as they reflect the local and regional vegetation changes, respectively (Birks Reference Birks, Elias and Mock2013). In case of differences in time range between previously determined pollen-based chronozones for Kotoń (Margielewski et al. Reference Margielewski, Obidowicz and Pelc2003) and Greendland ices cores event stratigraphy (Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Bigler, Blockley, Blunier, Buchardt, Clausen, Cvijanovic, Dahl-Jensen, Johnsen, Fischer, Gkinis, Guillevic, Hoek, Lowe, Pedro, Popp, Seierstad, Steffensen, Svensson, Vallelonga, Vinther, Walker, Wheatley and Winstrup2014), it is important to stress that GI-1d /Older Drays climate cooling is clearly defined in term of time range (14,025–13,904 yr BP), whereas for many palaeo-records (including Kotoń site) the Older Drays climate cooling was recognized as based solely on pollen diagrams, without a reference to specific time boundaries defined within extraregional chronologies (Björck et al. Reference Björck, Walker, Cwynar, Johnsen, Knudsen, Lowe and Wohlfarth1998; Mangerud et al. Reference Mangerud, Andersen, Berglund and Donner1974; Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Bigler, Blockley, Blunier, Buchardt, Clausen, Cvijanovic, Dahl-Jensen, Johnsen, Fischer, Gkinis, Guillevic, Hoek, Lowe, Pedro, Popp, Seierstad, Steffensen, Svensson, Vallelonga, Vinther, Walker, Wheatley and Winstrup2014). Therefore, the discrepancies in the depth extent between pollen-based and chronology-based divisions of the sediment sequence are possible (Margielewski et al. Reference Margielewski, Obidowicz, Zernitskaya and Korzeń2022a).

Despite their rarity across Europe, localities with the late glacial deposits in which GI-1d/Older Dryas was distinguished based on absolute chronology and reflected in pollen and/or plant macrofossil data represent various topographical settings and palaeoenvironmental conditions. In the central-western part of the Polish Lowlands, GI-1d/Older Dryas was recognized as a time of the main dune formation stage, replacing the earlier pedogenic processes of GI-1e/ Bølling climate amelioration (Moska et al. Reference Moska, Sokołowski, Jary, Zieliński, Raczyk, Szymak, Krawczyk, Skurzyński, Poręba, Łopuch and Tudyka2022) (Figure 4). In the sediments of small depressions developed within cover sand ridge near Rieme (NW Belgium), the GI-1d /Older Dryas was characterized by ceasing of organic material deposition and inserts of sand overblown to the depressions by wind as a result of surface erosion in an open landscape (Bos et al. Reference Bos, Verbruggen, Engels and Crombé2013) (Figure 4). On the contrary, during GI-1e /Bølling and GI-1c /Allerød climatic oscillations these depressions experienced increase in the groundwater level probably related to permafrost thawing.

Bølling-Older Dryas-Allerød sequence (corresponding to GI-1e, GI-1d and GI-1c, respectively) was also distinctively recorded in the other NW Belgium site, Moervaart palaeo-lake (Bos et al. Reference Bos, De Smedt, Demiddele, Hoek, Langohr, Marcelino, Van Asch, Van Damme, Van der Meeren, Verniers, Boeckx, Boudin, Court-Picon, Finke, Gelorini, Gobert, Heiri, Martens, Mostaert, Serbruyns, Van Strydonck and Crombé2017) (Figure 4). In this sequence, Bølling was characterized by a development (due to rise in the groundwater level) of a calcareous and mesotrophic shallow lake fringed with swamps and surrounded by a dwarf shrub tundra. Older Dryas deposits revealed shallowing of the lake and a transition to a swamp, surrounded by a grass-steppe tundra landscape. Early Allerød lacustrine sediments of Moervaart lake documented a lake deepening, boreal birch forests development, soil formation and occurrence of more diverse vegetation and habitats.

In case of deposits of Gerzensee lake (603 m a.s.l.) located in the Swiss Plateau region, the chronology was based on the correlation of oxygen isotope record with those of NGRIP (Van Raden et al. Reference Van Raden, Colombaroli, Gilli, Schwander, Bernasconi, van Leeuwen, Leuenberger and Eicher2013) and assigned ages according to GICC-05 time scale, as years BP (Ammann et al. Reference Ammann, van Leeuwen, van der Knaap, Lischke, Heiri and Tinner2013). The Older Dryas (GI-1d) was reflected only as a minor increase on herb curves in pollen profiles, related to re-expansion of steppic conditions, and it was identified as the Aegelsee Oscillation (Ammann et al. Reference Ammann, van Leeuwen, van der Knaap, Lischke, Heiri and Tinner2013).

In the Carpathians in Romania, sites with calibrated age scales, pollen and macrofossil data have been available for correlation with the GRIP oxygen isotope profile (Feurdean et al. Reference Feurdean, Wohlfarth, Björkman, Tantau, Bennike, Willis, Farcas and Robertsson2007; Feurdean and Bennike Reference Feurdean and Bennike2004). For example, in Preluca Tiganului (730 m a.s.l.) (Feurdean and Bennike Reference Feurdean and Bennike2004), a small infilled former volcanic crater lake, during ca. 14,100–13,800 cal BP an episode of drying and cooling of the climate was recognised (Figure 4). At the beginning of this short oscillation, deposition of gyttja peat and later also peat (rise in organic matter content) and scarcity of telmatic plants macrofossils indicate a decrease in water table. Around ca. 14,000 cal BP, over the peat layer gyttja peat and later also peaty gyttja was accumulated, suggesting gradual re-flooding of the lake. Again, however, at ca. 13,900 cal BP the waterbody shallowed and became overgrown, resulting in carr peat formation (drier climatic conditions). In case of regional vegetation changes, during ca. 14,100–13,800 cal BP amount of arboreal pollen decreased, whereas non-arboreal increased, implying opening of the woodland and cooler climatic conditions (Figure 4). For the proceeding time interval, 13,800–12,900 cal BP (corresponding to the warm episode GI 1c-1a/Allerød), open boreal forests predominated, whereas locally, in Preluca Tiganului site, carr peat accumulation continued in the mire environment, however with developed open water pools (Feurdean and Bennike Reference Feurdean and Bennike2004).

The observed vegetation, palaeoclimatic and palaeohydrological changes recorded both in the Kotoń sediment sequence and the other sites of Europe possessing Bølling-Older Dryas-Allerød transition well correlated with Greenland ice cores, show distinct similarities but also differences. In case of all presented sites, during GI-1d/Older Dryas climatic oscillation vegetation of the surrounding areas was characterized by open-space habitats with herbs, shrubs and sparse tree stands, e.g. steppe-tundra, reflecting the cold and dry climatic conditions (Figure 4). There is also a consistency in occurrence of a shallowing process of the palaeo-lakes: during the Kotoń palaeoecological stage KT-2 an overgrowing of the waterbody was recognised, similarly to Moervaart palaeo-lake (transition to swamp) and Preluca Tiganului crater lake (decreasing water level, however with some episode of re-flooding) (Figure 4). Although for the other localities this process was attributed to the dry climatic conditions, in case of Kotoń site, the role of autogenic succession has to be considered as a main factor of the waterbody terrestralization. Another difference is that no influence from the aeolian activity was detected in the Kotoń deposits as it was established for the Leszczyca or Rieme sites (Figure 4), possibly due to substantially different depositional environments (dunes/sand ridges of the lowlands vs landslide lake/fen of the mountains). During the proceeding Allerød climatic warming (GI-1c) and establishment of the boreal forest dominated by Betula and conifers (Pinus, Larix, Picea), the evolution of the mentioned sites differs according to the local hydrological regime (Figure 4). In case of Rieme and Moervaart the stage of a deeper waterbody reappears, whereas in case of Kotoń and Preluca Tiganului the shallow waterbodies of the Older Dryas stage overgrow further with vegetation and turn into the mires, possibly with some open-water pools preserved.

To sum up, despite the fact that the influence of GI-1d/Older Dryas climate cooling on the surrounding and regional vegetation was recognised for the Kotoń KT-2 deposits, in case of local vegetation and palaeohydrological changes more detail multi-proxy research is necessary to distinguish the climatic impact from the autogenic succession.

Conclusions

-

1. Four palaeoecological stages of development were determined for the Kotoń landslide fen deposits between ca. 14,600–13,500 cal BP showing the agreement with the earlier pollen division of the Kotoń deposits and with the extraregional chronology of the Greenland ice cores. Stage KT-1 (from ca. 14,240 ± 103 to > ca. 14,070 ± 72 cal BP, > ca. 170 years; GI-1e/Bølling and possibly the GS-2/Oldest Dryas) was characterized by the occurrence of a poor-in-vegetation waterbody with prevailing clastic sedimentation in the presumably open-space surrounding (caused by local landslide conditions and/or cold climate). Stage KT-2 (from ca. 14,070 ± 72 to ca. 13,900 ± 56 cal BP, >ca. 170 years, the GI-1d/Older Dryas) was represented by a gyttja-like deposits of oligo-mesotrophic waterbody with vegetation dominated by Characeae meadows, Sarmentypnum trichophyllum and sedges, probably surrounded by the steppe-tundra habitats. Stage KT-3 (from ca. 13,900 ± 56 to ca. 13,820 ± 68 cal BP, ca. 80 years; the transition from the GI-1d /Older Dryas to GI-1c/Allerød) documented waterbody overgrowing as a result of natural autogenic succession and a change into (calcareous) extremely rich fen predominated by calciphilous Bryopsida species. Stage KT-4 (from ca. 13,820 ± 68 to ca. 13,500 ± 115, ca. 320 years; GI-1c/Allerød) documented the birch-pine boreal forest development caused by climate warming and the transition to the moderately rich fen probably due to moss fen peat accumulation (reduced access to the calcium-rich groundwater).

-

2. Despite their rarity across Europe, localities with the late glacial deposits in which GI-1d/Older Dryas was distinguished based on absolute chronology and reflected in pollen and/or plant macrofossil data represent various topographical settings and palaeoenvironmental conditions. In all presented sites, during the Older Dryas climatic oscillation vegetation of the surrounding areas was characterized by open-space habitats with herbs, shrubs and sparse tree stands, e.g. steppe-tundra, reflecting the cold and dry climatic conditions. Locally, some of the sites (including Kotoń) experienced a shallowing of the existing palaeo-waterbodies. Although for the other localities this process was attributed to the dry climatic conditions, in case of Kotoń site the role of autogenic succession has to be considered as a main factor of the waterbody terrestralization. Even though the influence of GI-1d/Older Dryas climate cooling on the surrounding and regional vegetation was recognised for the Kotoń KT-2 deposits, in case of local vegetation and palaeohydrological changes more detail multi-proxy research is necessary to distinguish the climatic impact from the autogenic succession.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2025.10122

Acknowledgments

This study was supported with funds from the National Science Centre, Poland, grant No. 2020/39/O/ST10/03504 (2021–2025). Bryopsida identification and interpretation conducted within this study was supported with funds from the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange within a NAWA Preludium Bis 2 foreign doctoral internship programme (BPN/PRE/2022/1/00033/U/00001). We are grateful to the Doctoral School of Natural and Agricultural Sciences in Kraków for the opportunity to conduct the research project as a PhD thesis. We thank Prof. Andrzej Obidowicz (W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences) for pollen analysis carried out during previous studies, MSc Eng. Andrzej Kalemba (Institute of Nature Conservation Polish Academy of Sciences) for his help with field works, as well as Prof. Krzysztof Lipka from the Agriculture University in Kraków, Poland, for peat type analysis. We thank also Dr. Lars Hedenäs (Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm, Sweden) for help in identification of Sarmentypnum trichophyllum and Doc. RNDr. Vítězslav Plášek (University of Ostrava, Czech Republic) for help in identification of Hygrohypnum molle s.lat., Hygrohypnum ochraceum and Kindbergia cf. praelonga. We sincerely thank the anonymous reviewers for their thorough and invaluable comments that led us to greatly improve our manuscript.

Declaration of competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.