1 Introduction

1.1 Free multiplicative Brownian motions and their Brown measures

In [Reference Biane4], Biane introduced the free multiplicative Brownian motion

![]() $b_t$

as an element of a tracial von Neumann algebra. As conjectured by Biane and proved by Kemp [Reference Kemp23],

$b_t$

as an element of a tracial von Neumann algebra. As conjectured by Biane and proved by Kemp [Reference Kemp23],

![]() $b_t$

is the limit in

$b_t$

is the limit in

![]() $*$

-distribution of the standard Brownian motion in the general linear group

$*$

-distribution of the standard Brownian motion in the general linear group

![]() $GL(N;\mathbb C)$

as

$GL(N;\mathbb C)$

as

![]() $N\rightarrow \infty $

. (See [Reference Banna, Capitaine and Cébron2] for a stronger version of Kemp’s result.) For a fixed

$N\rightarrow \infty $

. (See [Reference Banna, Capitaine and Cébron2] for a stronger version of Kemp’s result.) For a fixed

![]() $t>0$

, the element

$t>0$

, the element

![]() $b_t$

can be approximated by an element of the form:

$b_t$

can be approximated by an element of the form:

$$ \begin{align} b_t \sim \left(I+\sqrt{\frac{t}{k}}z_1\right)\ldots \left(I+\sqrt{\frac{t}{k}}z_k\right), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} b_t \sim \left(I+\sqrt{\frac{t}{k}}z_1\right)\ldots \left(I+\sqrt{\frac{t}{k}}z_k\right), \end{align} $$

where

![]() $z_1,\dots ,z_k$

are freely independent circular elements and k is large. More precisely,

$z_1,\dots ,z_k$

are freely independent circular elements and k is large. More precisely,

![]() $b_t$

is defined as the solution of a free Itô stochastic differential equation, as in Section 2.2 and then Theorem 1.14 in [Reference Driver, Hall, Ho, Kemp, Nemish, Nikitopoulos and Parraud11] shows that (1.1) approximates this solution.

$b_t$

is defined as the solution of a free Itô stochastic differential equation, as in Section 2.2 and then Theorem 1.14 in [Reference Driver, Hall, Ho, Kemp, Nemish, Nikitopoulos and Parraud11] shows that (1.1) approximates this solution.

There is also a “three-parameter” generalization

![]() $b_{s,\tau }$

of

$b_{s,\tau }$

of

![]() $b_t$

, labeled by a real variance parameter s and a complex covariance parameter

$b_t$

, labeled by a real variance parameter s and a complex covariance parameter

![]() $\tau $

. (The three parameters are s and the real and imaginary parts of

$\tau $

. (The three parameters are s and the real and imaginary parts of

![]() $\tau $

.) The original free multiplicative Brownian motion

$\tau $

.) The original free multiplicative Brownian motion

![]() $b_t$

corresponds to the case

$b_t$

corresponds to the case

![]() $s=\tau =t.$

The case in which

$s=\tau =t.$

The case in which

![]() $\tau =0$

gives Biane’s free unitary Brownian motion

$\tau =0$

gives Biane’s free unitary Brownian motion

![]() $u_s=b_{s,0}$

.

$u_s=b_{s,0}$

.

In the case that

![]() $\tau $

is real, the support of the Brown measure of the

$\tau $

is real, the support of the Brown measure of the

![]() $b_{s,\tau }$

was computed by Hall and Kemp [Reference Hall and Kemp19]. Then, Driver, Hall, and Kemp [Reference Driver, Hall and Kemp10] computed the actual Brown measure of

$b_{s,\tau }$

was computed by Hall and Kemp [Reference Hall and Kemp19]. Then, Driver, Hall, and Kemp [Reference Driver, Hall and Kemp10] computed the actual Brown measure of

![]() $b_t$

(not just its support). This result was then extended by Ho and Zhong [Reference Ho and Zhong21], who computed the Brown measure of

$b_t$

(not just its support). This result was then extended by Ho and Zhong [Reference Ho and Zhong21], who computed the Brown measure of

![]() $ub_t$

, where u is a unitary “initial condition,” assumed to be freely independent of

$ub_t$

, where u is a unitary “initial condition,” assumed to be freely independent of

![]() $b_t$

. Hall and Ho [Reference Hall and Ho17] then computed the Brown measure of

$b_t$

. Hall and Ho [Reference Hall and Ho17] then computed the Brown measure of

![]() $ub_{s,\tau }$

for arbitrary s and

$ub_{s,\tau }$

for arbitrary s and

![]() $\tau $

.

$\tau $

.

Finally, Demni and Hamdi [Reference Demni and Hamdi8] computed the support of the Brown measure of

![]() $pb_{s,0,}$

where p is a projection that is freely independent of

$pb_{s,0,}$

where p is a projection that is freely independent of

![]() $b_{s,0}$

. Although Demni and Hamdi extend many of the techniques used in [Reference Driver, Hall and Kemp10, Reference Hall and Ho17, Reference Ho and Zhong21] to their setting, the fact that the initial condition p is not unitary causes difficult technical issues that prevent them from computing the actual Brown measure of

$b_{s,0}$

. Although Demni and Hamdi extend many of the techniques used in [Reference Driver, Hall and Kemp10, Reference Hall and Ho17, Reference Ho and Zhong21] to their setting, the fact that the initial condition p is not unitary causes difficult technical issues that prevent them from computing the actual Brown measure of

![]() $pb_{s,0}$

.

$pb_{s,0}$

.

In this article, we study

![]() $xb_{s,\tau }$

, where the initial condition x is taken to be non-negative and freely independent of

$xb_{s,\tau }$

, where the initial condition x is taken to be non-negative and freely independent of

![]() $b_{s,\tau }$

. We will find a certain closed subset

$b_{s,\tau }$

. We will find a certain closed subset

![]() $D_{s,\tau }$

with the property that the Brown measure of

$D_{s,\tau }$

with the property that the Brown measure of

![]() $xb_{s,\tau }$

is zero outside

$xb_{s,\tau }$

is zero outside

![]() $D_{s,\tau }$

, except possibly at the origin. Simulations and analogous results for other cases strongly suggest that the closed support of the Brown measure of

$D_{s,\tau }$

, except possibly at the origin. Simulations and analogous results for other cases strongly suggest that the closed support of the Brown measure of

![]() $xb_{s,\tau }$

is precisely

$xb_{s,\tau }$

is precisely

![]() $D_{s,\tau }$

(or

$D_{s,\tau }$

(or

![]() $D_{s,\tau }\cup \{0\}$

).

$D_{s,\tau }\cup \{0\}$

).

One important aspect of the problem is to understand how the domains

![]() $D_{s,\tau }$

vary with respect to

$D_{s,\tau }$

vary with respect to

![]() $\tau $

with s fixed. (Compare Definition 2.5 and Section 3 in [Reference Hall and Ho17] in the case of a unitary initial condition.) For each s and

$\tau $

with s fixed. (Compare Definition 2.5 and Section 3 in [Reference Hall and Ho17] in the case of a unitary initial condition.) For each s and

![]() $\tau $

, we will construct a holomorphic map

$\tau $

, we will construct a holomorphic map

![]() $f_{s-\tau }$

defined on the complement of

$f_{s-\tau }$

defined on the complement of

![]() $D_{s,s}$

. We will show that this map is injective and tends to infinity at infinity. Then, the complement of

$D_{s,s}$

. We will show that this map is injective and tends to infinity at infinity. Then, the complement of

![]() $D_{s,\tau }$

will be the image of the complement of

$D_{s,\tau }$

will be the image of the complement of

![]() $D_{s,s}$

under

$D_{s,s}$

under

![]() $f_{s-\tau }$

. Thus, all the domains with a fixed value of s can be related to the domain

$f_{s-\tau }$

. Thus, all the domains with a fixed value of s can be related to the domain

![]() $D_{s,s}$

by means of

$D_{s,s}$

by means of

![]() $f_{s-\tau }$

. It then follows that the topology of the complement of

$f_{s-\tau }$

. It then follows that the topology of the complement of

![]() $D_{s,\tau }$

is the same for all

$D_{s,\tau }$

is the same for all

![]() $\tau $

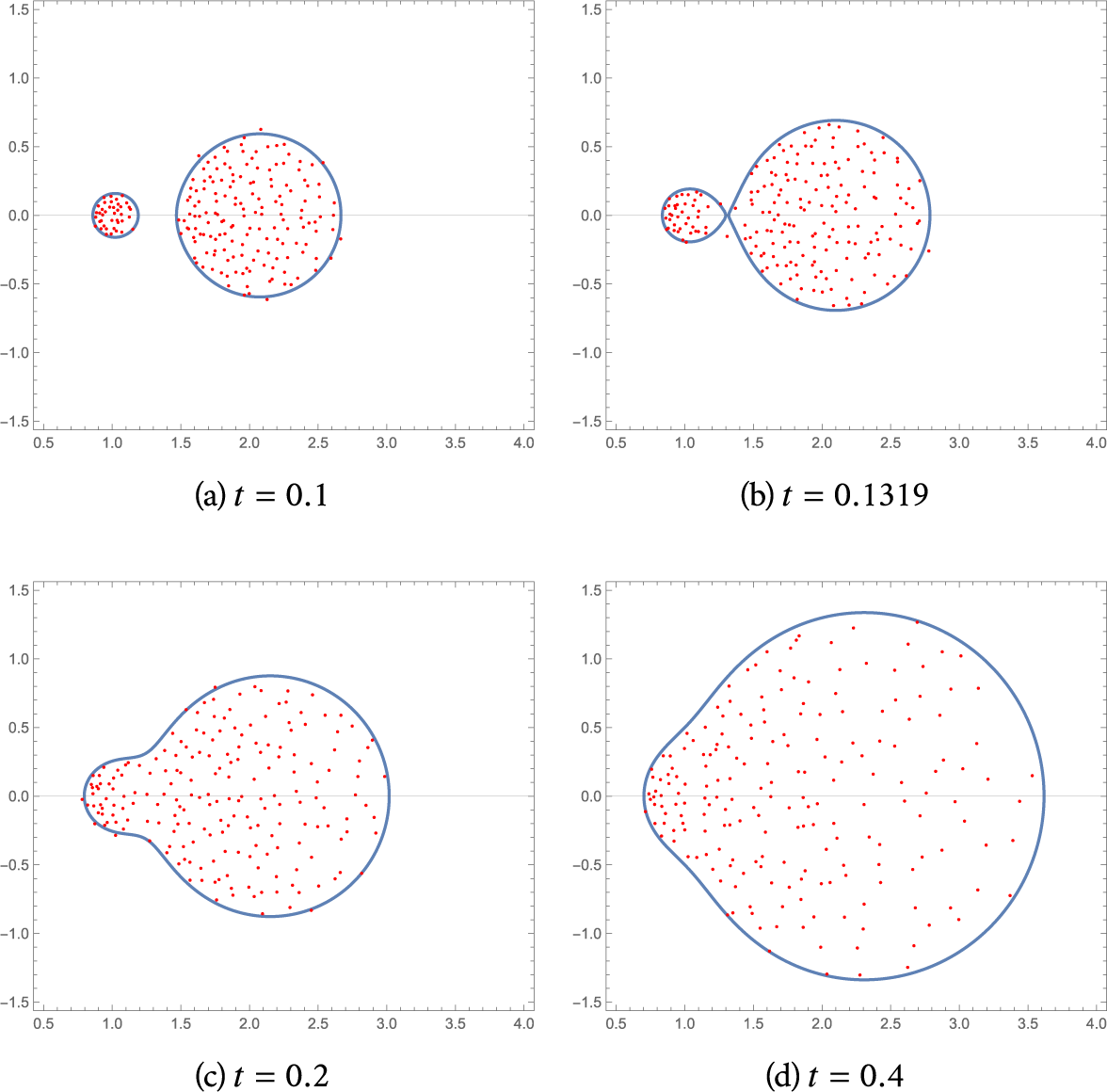

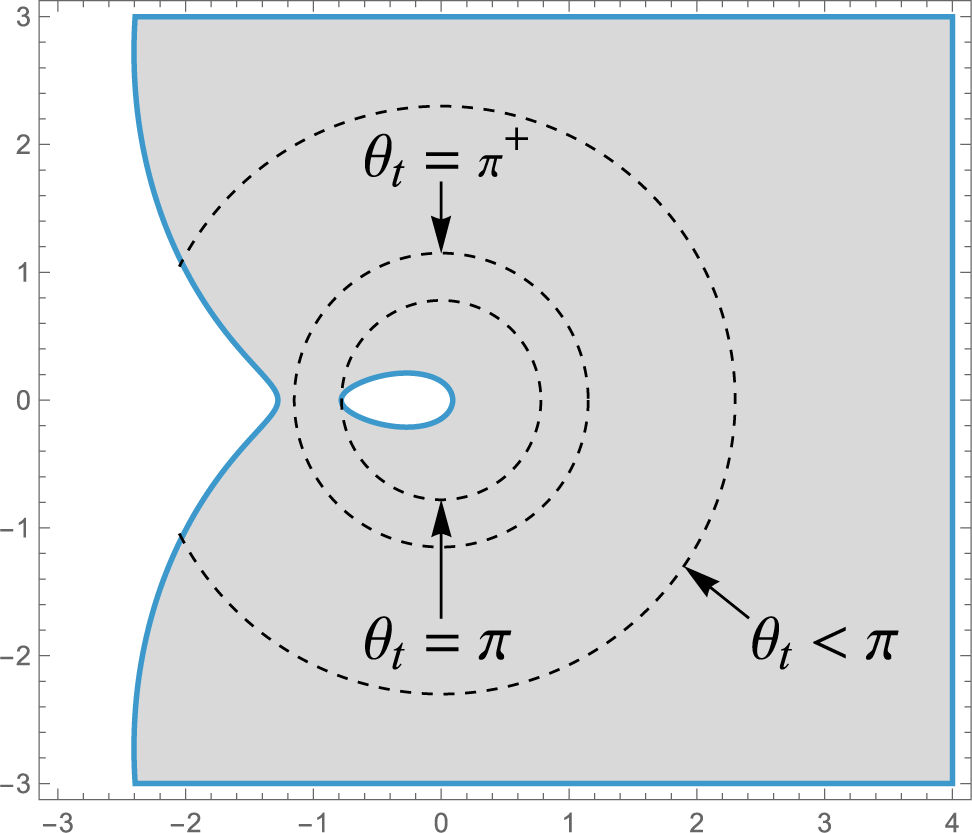

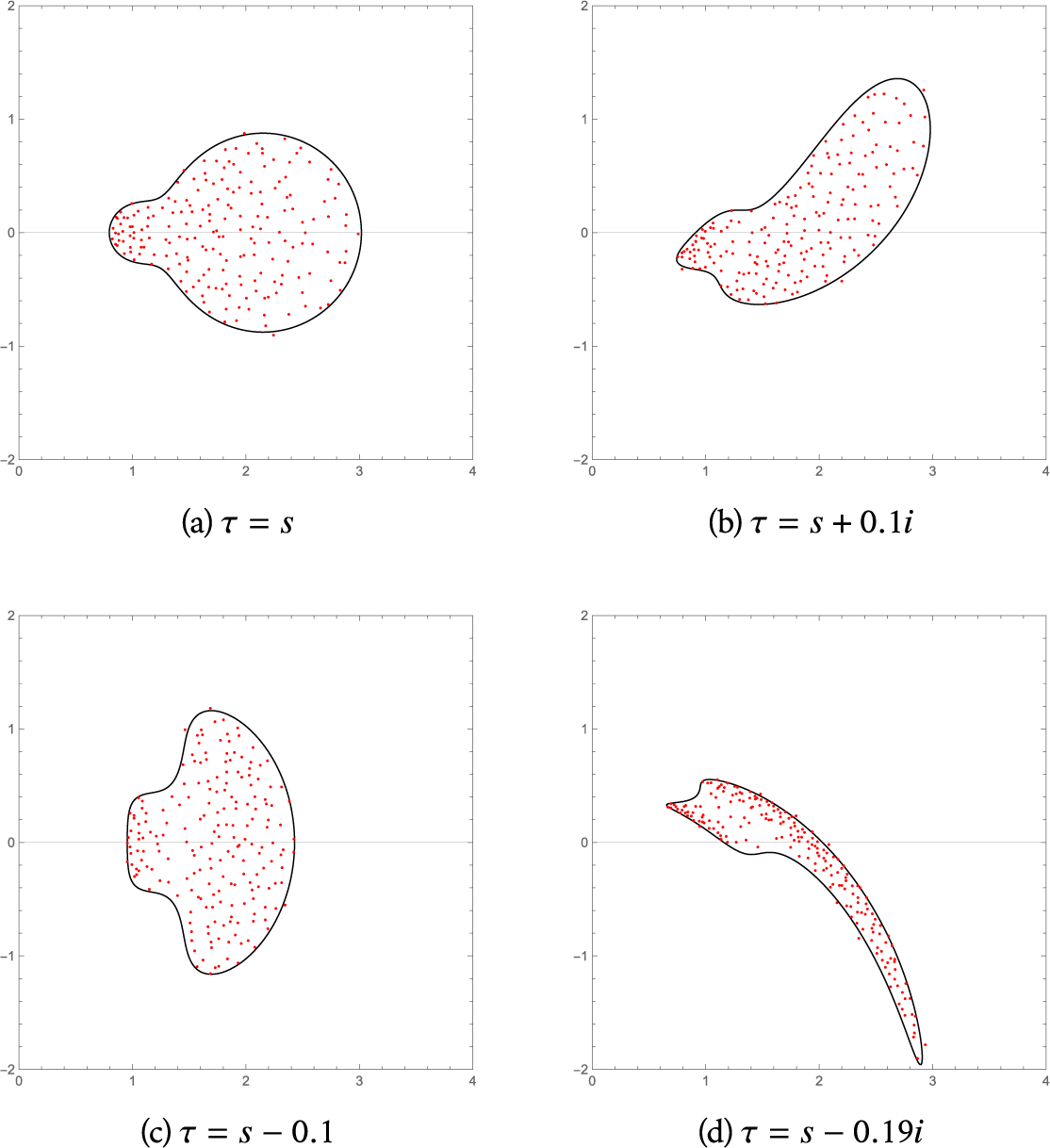

with s fixed. By contrast, Figure 1 shows that the topology of the complement of

$\tau $

with s fixed. By contrast, Figure 1 shows that the topology of the complement of

![]() $D_{s,\tau }$

can change when s changes (in this case, with

$D_{s,\tau }$

can change when s changes (in this case, with

![]() $\tau =s$

).

$\tau =s$

).

Figure 1: The domain

![]() $\overline {\Sigma }_t$

with the eigenvalues (red dots) of a random matrix approximation to

$\overline {\Sigma }_t$

with the eigenvalues (red dots) of a random matrix approximation to

![]() $xb_t$

, in the case

$xb_t$

, in the case

![]() $\mu =\frac {1}{5}\delta _{1} +\frac {4}{5}\delta _2$

.

$\mu =\frac {1}{5}\delta _{1} +\frac {4}{5}\delta _2$

.

When

![]() $\tau =0$

and x is a projection, our result reduces to the one obtained by Demni and Hamdi. Thus, our work generalizes [Reference Demni and Hamdi8] by allowing arbitrary values of

$\tau =0$

and x is a projection, our result reduces to the one obtained by Demni and Hamdi. Thus, our work generalizes [Reference Demni and Hamdi8] by allowing arbitrary values of

![]() $\tau $

and arbitrary non-negative initial conditions. The difficulties in computing the Brown measure in the setting of Demni and Hamdi persist in our setting and we do not address that problem here. See Remark 3.3 for an indication of why the case of a non-negative initial condition is harder than a unitary initial condition.

$\tau $

and arbitrary non-negative initial conditions. The difficulties in computing the Brown measure in the setting of Demni and Hamdi persist in our setting and we do not address that problem here. See Remark 3.3 for an indication of why the case of a non-negative initial condition is harder than a unitary initial condition.

1.2 The support of

$b_t$

with non-negative initial condition

$b_t$

with non-negative initial condition

In this section, we briefly describe how our results are obtained in the case

![]() $\tau =s$

. In the next section, we describe how the case of general

$\tau =s$

. In the next section, we describe how the case of general

![]() $\tau $

is reduced to the case

$\tau $

is reduced to the case

![]() $\tau =s.$

Let

$\tau =s.$

Let

![]() $ \mu $

be the law (or spectral distribution) of the non-negative initial condition x. That is,

$ \mu $

be the law (or spectral distribution) of the non-negative initial condition x. That is,

![]() $\mu $

is the unique probability measure on

$\mu $

is the unique probability measure on

![]() $[0, \infty )$

satisfying

$[0, \infty )$

satisfying

for all

![]() $k = 0,1,2,\dots $

, where

$k = 0,1,2,\dots $

, where

![]() $\operatorname {tr}$

is the trace on the relevant von Neumann algebra.

$\operatorname {tr}$

is the trace on the relevant von Neumann algebra.

We next define the regularized

![]() $\log $

potential function S as

$\log $

potential function S as

and its limit as

![]() $\varepsilon \rightarrow 0^+$

$\varepsilon \rightarrow 0^+$

Then, following Brown [Reference Brown6] (see also Chapter 11 of the monograph of Mingo and Speicher [Reference Mingo and Speicher24]), the Brown measure

![]() $\mu _t$

of

$\mu _t$

of

![]() $hb_t$

is the distributional Laplacian

$hb_t$

is the distributional Laplacian

According to Proposition 2.2, the function s is in

![]() $L^1_{\mathrm {loc}}$

and is subharmonic.

$L^1_{\mathrm {loc}}$

and is subharmonic.

The function S satisfies the following PDE, obtained similarly as in [Reference Ho and Zhong21], in logarithmic polar coordinates:

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\partial S}{\partial t} = \varepsilon\frac{\partial S}{\partial \varepsilon}\left(1+(|\lambda|^2-\varepsilon)\frac{\partial S}{\partial \varepsilon} - \frac{\partial S}{\partial \rho}\right), \quad \lambda = e^\rho e^{i\theta} = re^{i\theta} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\partial S}{\partial t} = \varepsilon\frac{\partial S}{\partial \varepsilon}\left(1+(|\lambda|^2-\varepsilon)\frac{\partial S}{\partial \varepsilon} - \frac{\partial S}{\partial \rho}\right), \quad \lambda = e^\rho e^{i\theta} = re^{i\theta} \end{align} $$

with initial condition

Following the PDE method given by [Reference Driver, Hall and Kemp10], we consider the following Hamiltonian, obtained by replacing each derivative on the right-hand side of (1.3) by a “momentum” variable, with an overall minus sign:

We then consider Hamilton’s equations, given as

$$ \begin{align}\frac{d\rho}{dt} = \frac{\partial H}{\partial p_\rho},\quad \frac{dp_\rho}{dt} = -\frac{\partial H}{\partial \rho},\end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align}\frac{d\rho}{dt} = \frac{\partial H}{\partial p_\rho},\quad \frac{dp_\rho}{dt} = -\frac{\partial H}{\partial \rho},\end{align} $$

and similarly for other pairs of variables. Given initial conditions for the “position” variables:

we take the initial conditions for the momentum variables to be

$$ \begin{align*} p_{\rho,0}(\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0) = \frac{\partial S(0,\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0)}{\partial \rho_0},\\ p_{\theta}(\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0) = \frac{\partial S(0,\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0)}{\partial \theta}, \\ p_{0}(\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0) = \frac{\partial S(0,\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0)}{\partial \varepsilon_0}. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} p_{\rho,0}(\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0) = \frac{\partial S(0,\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0)}{\partial \rho_0},\\ p_{\theta}(\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0) = \frac{\partial S(0,\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0)}{\partial \theta}, \\ p_{0}(\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0) = \frac{\partial S(0,\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0)}{\partial \varepsilon_0}. \end{align*} $$

Notation 1.1 In the above formulas, we follow [Reference Driver, Hall and Kemp10, Equation (5.4)] in using the expression

![]() $p_0$

(as opposed to

$p_0$

(as opposed to

![]() $p_{\varepsilon ,0}$

) to denote the value of

$p_{\varepsilon ,0}$

) to denote the value of

![]() $p_{\varepsilon }$

at

$p_{\varepsilon }$

at

![]() $t=0$

. This notation is consistent with the

$t=0$

. This notation is consistent with the

![]() $k=0$

case of the notation

$k=0$

case of the notation

![]() $p_k$

introduced below in (3.10).

$p_k$

introduced below in (3.10).

The solution S to the PDE (1.3) then satisfies the first Hamilton–Jacobi formula:

provided the solution to Hamilton’s equation exists up to time t (see [Reference Driver, Hall and Kemp10, Eqs (5.20) and (5.21)]). Since our aim is to compute

we want to choose good initial values

![]() $\varepsilon _0$

and

$\varepsilon _0$

and

![]() $\lambda _0$

so that

$\lambda _0$

so that

The next result says that we can achieve the goal in (1.8) by taking

![]() $\varepsilon _0$

approaching 0 and taking

$\varepsilon _0$

approaching 0 and taking

![]() $\lambda _0=\lambda $

, provided that the solution of Hamilton’s equations exists up to time t.

$\lambda _0=\lambda $

, provided that the solution of Hamilton’s equations exists up to time t.

Lemma 1.2 Assume that

![]() $\lambda _0$

is outside the support of

$\lambda _0$

is outside the support of

![]() $\mu $

. Then, in the limit as

$\mu $

. Then, in the limit as

![]() $\varepsilon _0\rightarrow 0$

, we have

$\varepsilon _0\rightarrow 0$

, we have

![]() $\varepsilon (t) \equiv 0$

and

$\varepsilon (t) \equiv 0$

and

![]() $\lambda (t) \equiv \lambda $

, for as long as the solution to Hamilton’s equations exists.

$\lambda (t) \equiv \lambda $

, for as long as the solution to Hamilton’s equations exists.

The proof is given on p. 19. If the lemma applies, the Hamilton–Jacobi formula (1.7) becomes

Furthermore, when

![]() $\varepsilon _0=0$

, we compute from (1.5) that

$\varepsilon _0=0$

, we compute from (1.5) that

![]() $H_0=0$

, so that we obtain

$H_0=0$

, so that we obtain

We emphasize, however, that this conclusion is valid only if the lifetime of the solution of Hamilton’s equations is greater than t when

![]() $\varepsilon _0 \rightarrow 0$

.

$\varepsilon _0 \rightarrow 0$

.

Now, we will compute that the limit of the lifetime of solutions to Hamilton’s equation, in the limit when

![]() $\varepsilon _0 \rightarrow 0$

, as

$\varepsilon _0 \rightarrow 0$

, as

$$\begin{align*}T(\lambda) = \frac{1}{{\tilde p}_2 - {\tilde p}_0r^2}\log\left(\frac{{\tilde p}_2}{{\tilde p}_0r^2}\right),\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}T(\lambda) = \frac{1}{{\tilde p}_2 - {\tilde p}_0r^2}\log\left(\frac{{\tilde p}_2}{{\tilde p}_0r^2}\right),\end{align*}$$

where

$$\begin{align*}{\tilde p}_k = \int_0^{\infty} \frac{\xi^k}{|\xi-\lambda|^2} \,d\mu(\xi).\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}{\tilde p}_k = \int_0^{\infty} \frac{\xi^k}{|\xi-\lambda|^2} \,d\mu(\xi).\end{align*}$$

Thus, we define a domain

![]() $\Sigma _t$

as follows:

$\Sigma _t$

as follows:

If we insert the initial condition (1.4) (at

![]() $\varepsilon =0$

) into the formula (1.9), we obtain the following result, whose proof has been outlined above.

$\varepsilon =0$

) into the formula (1.9), we obtain the following result, whose proof has been outlined above.

Theorem 1.3 (Free multiplicative Brownian motion with non-negative initial condition)

For all

![]() $(t,\lambda )$

with

$(t,\lambda )$

with

![]() $\lambda $

outside

$\lambda $

outside

![]() $\overline {\Sigma }_t$

, we have

$\overline {\Sigma }_t$

, we have

Since, as we will show, the closed support of

![]() $\mu $

is contained in

$\mu $

is contained in

![]() $\overline {\Sigma }_t\cup \{0\}$

, it follows that the Brown measure

$\overline {\Sigma }_t\cup \{0\}$

, it follows that the Brown measure

![]() $\mu _t$

is zero outside of

$\mu _t$

is zero outside of

![]() $\overline {\Sigma }_t$

, except possibly at the origin.

$\overline {\Sigma }_t$

, except possibly at the origin.

See Figure 1 for the domain

![]() $\overline {\Sigma }_t$

plotted with the eigenvalues (red dots) of a random matrix approximation to

$\overline {\Sigma }_t$

plotted with the eigenvalues (red dots) of a random matrix approximation to

![]() $xb_t$

, in the case

$xb_t$

, in the case

![]() $\mu =\frac {1}{5}\delta _{1} +\frac {4}{5}\delta _2$

.

$\mu =\frac {1}{5}\delta _{1} +\frac {4}{5}\delta _2$

.

1.3 The case of arbitrary

$\tau $

$\tau $

We now consider a family

![]() $b_{s,\tau }$

of free multiplicative Brownian motions, labeled by a positive real number s and a complex number

$b_{s,\tau }$

of free multiplicative Brownian motions, labeled by a positive real number s and a complex number

![]() $\tau $

satisfying

$\tau $

satisfying

These were introduced by Ho [Reference Ho20] when

![]() $\tau $

is real and by Hall and Ho [Reference Hall and Ho17] when

$\tau $

is real and by Hall and Ho [Reference Hall and Ho17] when

![]() $\tau $

is complex (see Section 2.2 for details). When

$\tau $

is complex (see Section 2.2 for details). When

![]() $\tau =s$

, the Brownian motion

$\tau =s$

, the Brownian motion

![]() $b_{s,s}$

has the same

$b_{s,s}$

has the same

![]() $*$

-distribution as

$*$

-distribution as

![]() $b_s$

and when

$b_s$

and when

![]() $\tau =0$

, the Brownian motion

$\tau =0$

, the Brownian motion

![]() $b_{s,0}$

has the same

$b_{s,0}$

has the same

![]() $*$

-distribution as Biane’s free unitary Brownian motion

$*$

-distribution as Biane’s free unitary Brownian motion

![]() $u_s$

.

$u_s$

.

When

![]() $\tau $

is real, the support of the Brown measure of

$\tau $

is real, the support of the Brown measure of

![]() $b_{s,\tau }$

was computed by Hall and Kemp [Reference Hall and Kemp19], using the large-N Segal–Bargmann transform developed by Driver–Hall–Kemp [Reference Driver, Hall and Kemp12] and Ho [Reference Ho20]. The Brown measure of

$b_{s,\tau }$

was computed by Hall and Kemp [Reference Hall and Kemp19], using the large-N Segal–Bargmann transform developed by Driver–Hall–Kemp [Reference Driver, Hall and Kemp12] and Ho [Reference Ho20]. The Brown measure of

![]() $ub_{s,\tau }$

when u is unitary and freely independent of

$ub_{s,\tau }$

when u is unitary and freely independent of

![]() $b_{s,\tau }$

was computed in [Reference Hall and Ho17]. In this article, we determine the support of the Brown measure of

$b_{s,\tau }$

was computed in [Reference Hall and Ho17]. In this article, we determine the support of the Brown measure of

![]() $xb_{s,\tau }$

when x is non-negative and freely independent of

$xb_{s,\tau }$

when x is non-negative and freely independent of

![]() $b_{s,\tau }$

.

$b_{s,\tau }$

.

To attack the problem for arbitrary

![]() $\tau $

, we will show that the regularized log potential of

$\tau $

, we will show that the regularized log potential of

![]() $xb_{s,\tau }$

satisfies a PDE with respect to

$xb_{s,\tau }$

satisfies a PDE with respect to

![]() $\tau $

with s fixed. We solve this PDE using as our initial condition the case

$\tau $

with s fixed. We solve this PDE using as our initial condition the case

![]() $\tau =s$

– which we have already analyzed, as in the previous section. To solve the PDE, we again use the Hamilton–Jacobi method and we again put

$\tau =s$

– which we have already analyzed, as in the previous section. To solve the PDE, we again use the Hamilton–Jacobi method and we again put

![]() $\varepsilon _0$

equal to 0. With

$\varepsilon _0$

equal to 0. With

![]() $\varepsilon _0=0$

, we again find that

$\varepsilon _0=0$

, we again find that

![]() $\varepsilon (t)$

is identically zero – but this time

$\varepsilon (t)$

is identically zero – but this time

![]() $\lambda (t)$

is not constant. Rather, for

$\lambda (t)$

is not constant. Rather, for

![]() $\lambda _0$

outside

$\lambda _0$

outside

![]() $\overline {\Sigma }_t$

, we find that with

$\overline {\Sigma }_t$

, we find that with

![]() $\varepsilon _0=0$

, we have

$\varepsilon _0=0$

, we have

where

![]() $f_{s-\tau }$

is a holomorphic function given by

$f_{s-\tau }$

is a holomorphic function given by

$$\begin{align*}f_{s-\tau}(z) = z\exp\left[\frac{s-\tau}{2}\int_0^{\infty} \frac{\xi+z}{\xi-z}\,d\mu(\xi)\right].\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}f_{s-\tau}(z) = z\exp\left[\frac{s-\tau}{2}\int_0^{\infty} \frac{\xi+z}{\xi-z}\,d\mu(\xi)\right].\end{align*}$$

The Hamilton–Jacobi method will then give a formula for the log potential of the Brown measure of

![]() $xb_{s,\tau }$

, valid at any nonzero point

$xb_{s,\tau }$

, valid at any nonzero point

![]() $\lambda $

of the form

$\lambda $

of the form

![]() $\lambda =f_{s-\tau }(\lambda _0)$

, with

$\lambda =f_{s-\tau }(\lambda _0)$

, with

![]() $\lambda _0$

outside

$\lambda _0$

outside

![]() $\overline {\Sigma }_t$

. This formula will show that the Brown measure of

$\overline {\Sigma }_t$

. This formula will show that the Brown measure of

![]() $xb_{s,\tau }$

is zero near

$xb_{s,\tau }$

is zero near

![]() $\lambda $

.

$\lambda $

.

We summarize the preceding discussion with the following definition and theorem.

Definition 1.1 For all

![]() $s>0$

and

$s>0$

and

![]() $\tau \in \mathbb {C}$

such that

$\tau \in \mathbb {C}$

such that

![]() $|\tau -s| \leq s$

, we define a closed domain

$|\tau -s| \leq s$

, we define a closed domain

![]() $D_{s,\tau }$

characterized by

$D_{s,\tau }$

characterized by

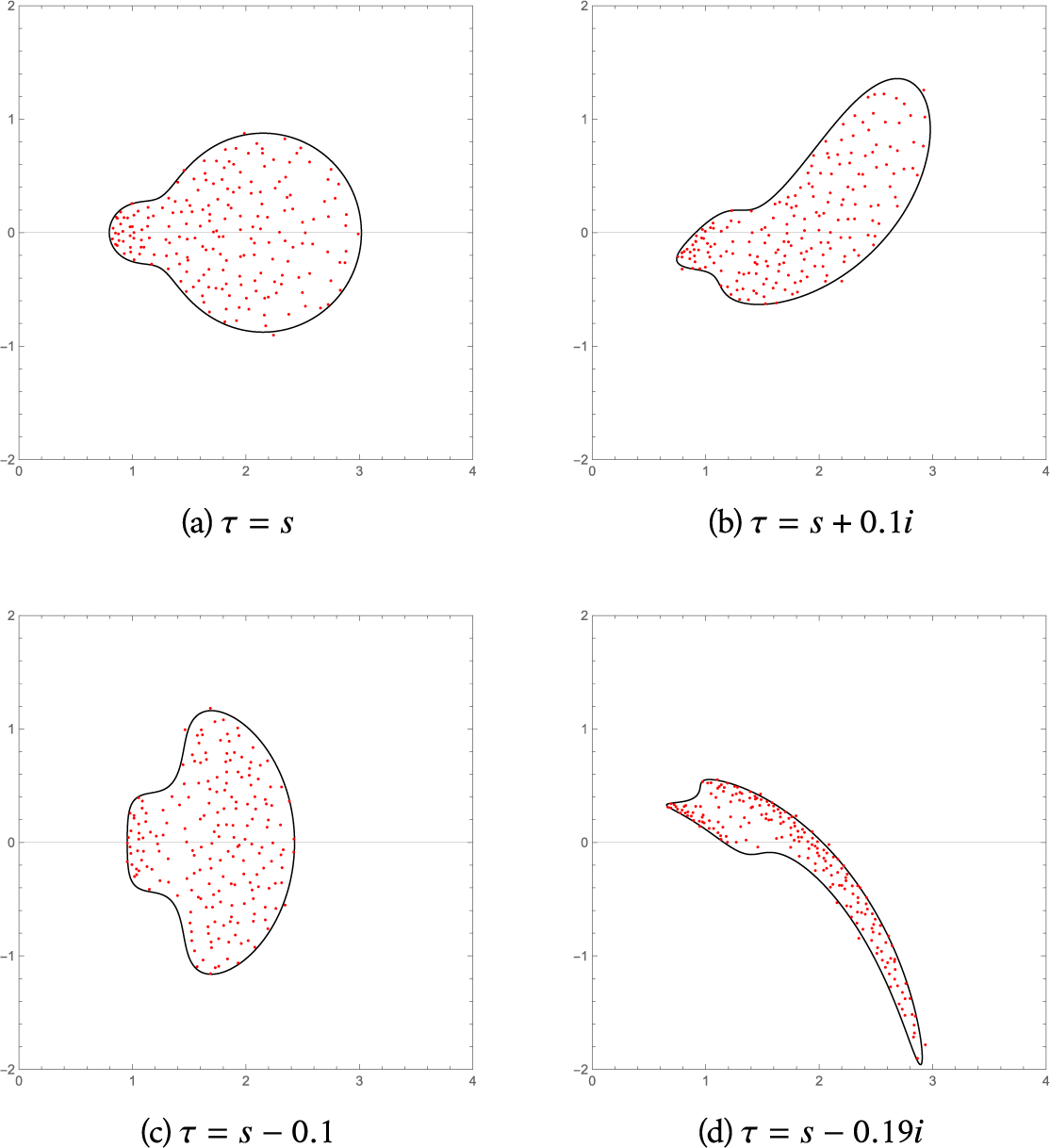

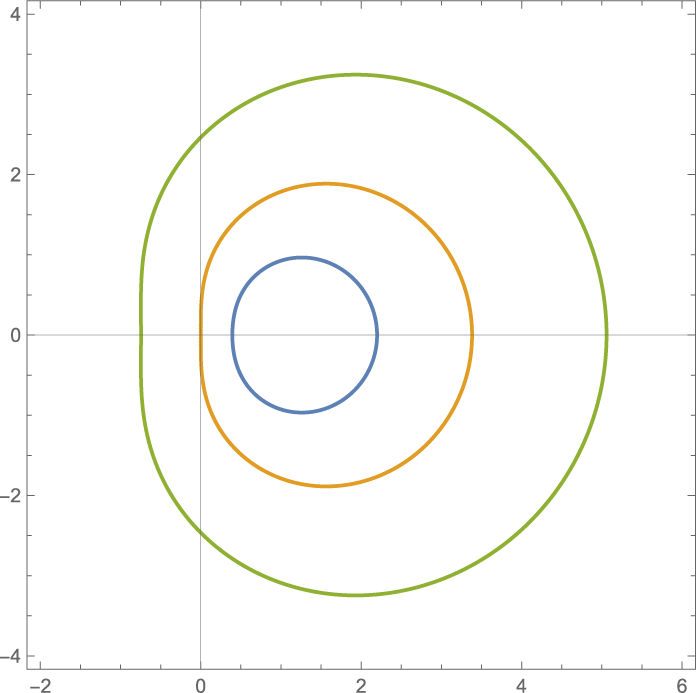

That is to say, the complement of

![]() $D_{s,\tau }$

is the image of the complement of

$D_{s,\tau }$

is the image of the complement of

![]() $\overline {\Sigma }_s$

under

$\overline {\Sigma }_s$

under

![]() $f_{s-\tau }$

(see Figure 2). When

$f_{s-\tau }$

(see Figure 2). When

![]() $\tau =s$

, we have that

$\tau =s$

, we have that

![]() $f_{s-\tau }(z)=z$

, so that

$f_{s-\tau }(z)=z$

, so that

![]() $D_{s,s}=\overline \Sigma _s$

.

$D_{s,s}=\overline \Sigma _s$

.

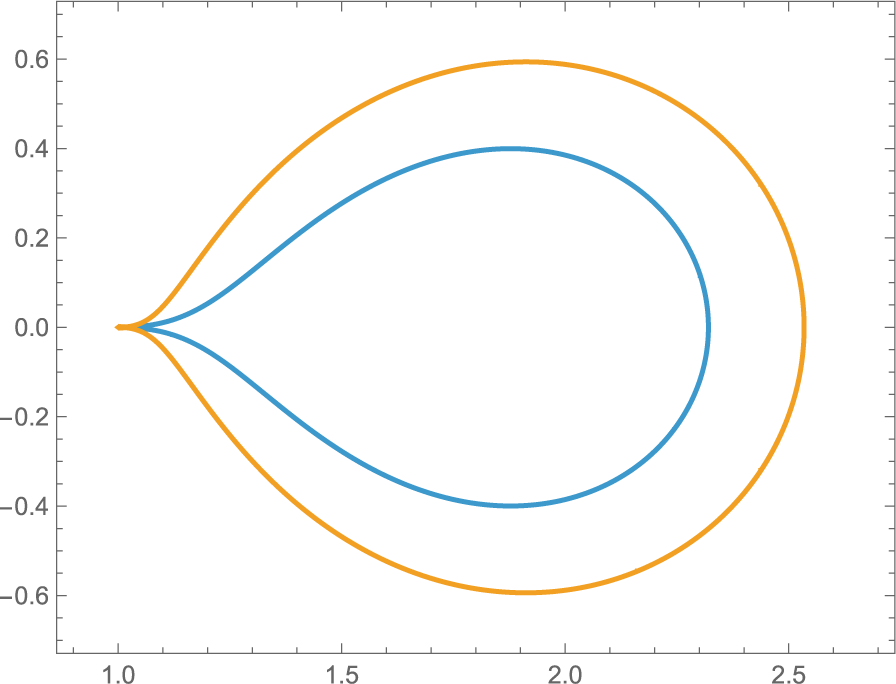

Figure 2: The domain

![]() $D_{s,\tau }$

along with the eigenvalues (red dots) of a random matrix approximation to

$D_{s,\tau }$

along with the eigenvalues (red dots) of a random matrix approximation to

![]() $xb_{s,\tau }$

, with

$xb_{s,\tau }$

, with

![]() $s=0.2$

and

$s=0.2$

and

![]() $\mu =\frac {1}{5}\delta _{1} +\frac {4}{5}\delta _2$

.

$\mu =\frac {1}{5}\delta _{1} +\frac {4}{5}\delta _2$

.

Theorem 1.4 For all

![]() $s>0$

and

$s>0$

and

![]() $\tau \in \mathbb {C}$

such that

$\tau \in \mathbb {C}$

such that

![]() $|\tau -s| \leq s$

, the Brown measure of

$|\tau -s| \leq s$

, the Brown measure of

![]() $xb_{s,\tau }$

is zero outside

$xb_{s,\tau }$

is zero outside

![]() $D_{s,\tau }$

, except possibly at the origin.

$D_{s,\tau }$

, except possibly at the origin.

When the origin is not in

![]() $D_{s,\tau }$

, we will, in addition, show that the mass of the Brown measure at the origin equals the mass of the measure

$D_{s,\tau }$

, we will, in addition, show that the mass of the Brown measure at the origin equals the mass of the measure

![]() $\mu $

at the origin.

$\mu $

at the origin.

Remark 1.5 Although this article uses the PDE method introduced in [Reference Driver, Hall and Kemp10], one could attempt to follow the method of Hall and Kemp in [Reference Hall and Kemp19], which computes the support of the Brown measure of

![]() $b_{s,\tau }$

(in the case

$b_{s,\tau }$

(in the case

![]() $\tau $

is real). The paper [Reference Hall and Kemp19] makes use of the free Segal–Bargmann transform introduced by Biane in [Reference Biane4] and extended by Ho [Reference Ho20]. This transform is the large-N limit of the Segal–Bargmann transform of the second author [Reference Hall14] for the unitary group

$\tau $

is real). The paper [Reference Hall and Kemp19] makes use of the free Segal–Bargmann transform introduced by Biane in [Reference Biane4] and extended by Ho [Reference Ho20]. This transform is the large-N limit of the Segal–Bargmann transform of the second author [Reference Hall14] for the unitary group

![]() $U(N)$

(see also [Reference Chan7, Reference Driver, Hall and Kemp12, Reference Hall15]).

$U(N)$

(see also [Reference Chan7, Reference Driver, Hall and Kemp12, Reference Hall15]).

One could then attempt to incorporate the non-negative element x into the analysis of [Reference Hall and Kemp19]. This would require extending the results of [Reference Biane4, Reference Hall14, Reference Ho20] to handle arbitrary (not necessarily unitary) initial conditions. Even if this extension were successful, one would still have to understand the support of the Brown measure of

![]() $xu_t$

, where

$xu_t$

, where

![]() $u_t$

is the free unitary Brownian motion, as the starting point for the analysis. But the only known method for computing this support is the PDE method, either in the form used in [Reference Demni and Hamdi8] or in the form used in the present article. At that point, it makes more sense to simply use the PDE method throughout.

$u_t$

is the free unitary Brownian motion, as the starting point for the analysis. But the only known method for computing this support is the PDE method, either in the form used in [Reference Demni and Hamdi8] or in the form used in the present article. At that point, it makes more sense to simply use the PDE method throughout.

Remark 1.6 Recent results of the second author with Ho [Reference Hall and Ho18] give information about the spectrum of

![]() $xb_{s,\tau }$

. Specifically, suppose z is a nonzero complex number outside

$xb_{s,\tau }$

. Specifically, suppose z is a nonzero complex number outside

![]() $D_{s,\tau }$

and suppose

$D_{s,\tau }$

and suppose

![]() $\lambda $

is the complex number outside

$\lambda $

is the complex number outside

![]() $\bar \Sigma _t$

such that

$\bar \Sigma _t$

such that

![]() $f_{s-\tau }(\lambda )=z$

. Then, if

$f_{s-\tau }(\lambda )=z$

. Then, if

![]() $T(\lambda )>t$

, [Reference Hall and Ho18, Theorem 5.10] shows that z is outside the spectrum of

$T(\lambda )>t$

, [Reference Hall and Ho18, Theorem 5.10] shows that z is outside the spectrum of

![]() $xb_{s,\tau }$

. By Lemma 3.14 below, the condition

$xb_{s,\tau }$

. By Lemma 3.14 below, the condition

![]() $T(\lambda )>t$

will be satisfied for all

$T(\lambda )>t$

will be satisfied for all

![]() $\lambda $

outside

$\lambda $

outside

![]() $\bar \Sigma _t$

, except possibly for certain points on the positive real axis.

$\bar \Sigma _t$

, except possibly for certain points on the positive real axis.

2 Preliminaries

2.1 Free probability

A tracial von Neumann algebra is a pair

![]() $(\mathcal {A},\operatorname {tr})$

, where

$(\mathcal {A},\operatorname {tr})$

, where

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

is a von Neumann algebra and

$\mathcal {A}$

is a von Neumann algebra and

![]() $\operatorname {tr}:\mathcal {A}\rightarrow \mathbb C$

is a faithful, normal, tracial state on

$\operatorname {tr}:\mathcal {A}\rightarrow \mathbb C$

is a faithful, normal, tracial state on

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

. Here, “tracial” means that

$\mathcal {A}$

. Here, “tracial” means that

![]() $\operatorname {tr}(ab)=\operatorname {tr}(ba)$

, “faithful” means that

$\operatorname {tr}(ab)=\operatorname {tr}(ba)$

, “faithful” means that

![]() $\operatorname {tr}(a^*a)>0$

for all nonzero a, and “normal” means that

$\operatorname {tr}(a^*a)>0$

for all nonzero a, and “normal” means that

![]() $\operatorname {tr}$

is continuous with respect to the weak operator topology. The elements in

$\operatorname {tr}$

is continuous with respect to the weak operator topology. The elements in

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

are called (noncommutative) random variables.

$\mathcal {A}$

are called (noncommutative) random variables.

Unital

![]() $\ast $

-subalgebras

$\ast $

-subalgebras

![]() $\mathcal {A}_1,\dots ,\mathcal {A}_n \subset \mathcal {A}$

are said to be freely independent if given any

$\mathcal {A}_1,\dots ,\mathcal {A}_n \subset \mathcal {A}$

are said to be freely independent if given any

![]() $i_1,\dots , i_m \in \{1,\dots ,n\}$

with

$i_1,\dots , i_m \in \{1,\dots ,n\}$

with

![]() $i_k \neq i_{k+1}$

and

$i_k \neq i_{k+1}$

and

![]() $a_{i_k} \in \mathcal {A}_{i_k}$

such that

$a_{i_k} \in \mathcal {A}_{i_k}$

such that

![]() $\operatorname {tr}(a_{i_k}) = 0$

for all

$\operatorname {tr}(a_{i_k}) = 0$

for all

![]() $1\leq k \leq m$

, we have

$1\leq k \leq m$

, we have

![]() $\operatorname {tr}(a_{i_1}\dots a_{i_m}) =0.$

Moreover, random variables

$\operatorname {tr}(a_{i_1}\dots a_{i_m}) =0.$

Moreover, random variables

![]() $a_1,\dots ,a_m$

are said to be freely independent if the unital

$a_1,\dots ,a_m$

are said to be freely independent if the unital

![]() $\ast $

-subalgebras generated by them are freely independent.

$\ast $

-subalgebras generated by them are freely independent.

For any self-adjoint random variable

![]() $a\in \mathcal {A}$

, the law or the distribution of a is the unique compactly supported probability measure on

$a\in \mathcal {A}$

, the law or the distribution of a is the unique compactly supported probability measure on

![]() $\mathbb {R}$

such that for any bounded continuous function f on

$\mathbb {R}$

such that for any bounded continuous function f on

![]() $\mathbb {R}$

, we have

$\mathbb {R}$

, we have

2.2 Free Brownian motions

In free probability, the semicircular law plays a role similar to the Gaussian distribution in classical probability. The semicircular law

![]() $\sigma _t$

with variance t is the probability measure supported in

$\sigma _t$

with variance t is the probability measure supported in

![]() $[-2\sqrt {t},2\sqrt {t}]$

with density there given by

$[-2\sqrt {t},2\sqrt {t}]$

with density there given by

Definition 2.1 A free semicircular Brownian motion

![]() $s_t$

in a tracial von Neumann algebra

$s_t$

in a tracial von Neumann algebra

![]() $(\mathcal {A},\operatorname {tr})$

is a weakly continuous free stochastic process

$(\mathcal {A},\operatorname {tr})$

is a weakly continuous free stochastic process

![]() $(s_t)_{t\geq 0}$

with freely independent increments and such that the law of

$(s_t)_{t\geq 0}$

with freely independent increments and such that the law of

![]() $s_{t_2}-s_{t_1}$

is semicircular with variance

$s_{t_2}-s_{t_1}$

is semicircular with variance

![]() $t_2-t_1$

for all

$t_2-t_1$

for all

![]() $0<t_1<t_2$

. A free circular Brownian motion

$0<t_1<t_2$

. A free circular Brownian motion

![]() $c_t$

has the form

$c_t$

has the form

![]() $\frac {1}{\sqrt {2}}(s_t+is_t')$

, where

$\frac {1}{\sqrt {2}}(s_t+is_t')$

, where

![]() $s_t$

and

$s_t$

and

![]() $s_t'$

are two freely independent free semicircular Brownian motions.

$s_t'$

are two freely independent free semicircular Brownian motions.

Definition 2.2 The free multiplicative Brownian motion

![]() $b_t$

is the solution of the free Itô stochastic differential equation

$b_t$

is the solution of the free Itô stochastic differential equation

where

![]() $c_t$

is a free circular Brownian motion.

$c_t$

is a free circular Brownian motion.

We refer to the work of Biane and Speicher [Reference Biane and Speicher5] and Nikitopoulos [Reference Nikitopoulos25] for information about free stochastic calculus and to [Reference Biane4, Section 4.2.1] for information about the free multiplicative Brownian motion (denoted there as

![]() $\Lambda _t$

). According to [Reference Biane4],

$\Lambda _t$

). According to [Reference Biane4],

![]() $b_t$

is invertible for all t. Then, the right increments of

$b_t$

is invertible for all t. Then, the right increments of

![]() $b_t$

are freely independent. That is for every

$b_t$

are freely independent. That is for every

![]() $0<t_1 <\dots <t_n$

in

$0<t_1 <\dots <t_n$

in

![]() $[0, \infty )$

, the random variables

$[0, \infty )$

, the random variables

are freely independent.

Now, to define free multiplicative

![]() $(s,\tau )$

-Brownian motion, we introduce a rotated elliptic element as follows.

$(s,\tau )$

-Brownian motion, we introduce a rotated elliptic element as follows.

Definition 2.3 A rotated elliptic element is an element Z of the following form:

where X and Y are freely independent semicircular elements,

![]() $a,b,$

and

$a,b,$

and

![]() $\theta $

are real numbers, and we assume that a and b are not both zero.

$\theta $

are real numbers, and we assume that a and b are not both zero.

As in Section 2.1 in [Reference Hall and Ho17], we then parameterize rotated elliptic elements by two parameters: a positive variance parameter s and a complex covariance parameter

![]() $\tau $

defined by

$\tau $

defined by

$$ \begin{align*} s &= \operatorname{tr}[Z^\ast Z]\\ \tau &= \operatorname{tr}[Z^\ast Z] - \operatorname{tr}[Z^2]. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} s &= \operatorname{tr}[Z^\ast Z]\\ \tau &= \operatorname{tr}[Z^\ast Z] - \operatorname{tr}[Z^2]. \end{align*} $$

By applying the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality to the inner product

![]() $\operatorname {tr}(A^\ast B),$

we see that any rotated elliptic element satisfies

$\operatorname {tr}(A^\ast B),$

we see that any rotated elliptic element satisfies

Conversely, if s and

![]() $\tau $

satisfy (2.2), we can construct a rotated elliptic element with those parameters by choosing

$\tau $

satisfy (2.2), we can construct a rotated elliptic element with those parameters by choosing

![]() $a, b,$

and

$a, b,$

and

![]() $\theta $

as

$\theta $

as

$$ \begin{align*} a &= \sqrt{\frac{1}{2}(s+|\tau-s|)}\\ b &= \sqrt{\frac{1}{2}(s-|\tau-s|)}\\ \theta &= \frac{1}{2}\arg(s-\tau). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} a &= \sqrt{\frac{1}{2}(s+|\tau-s|)}\\ b &= \sqrt{\frac{1}{2}(s-|\tau-s|)}\\ \theta &= \frac{1}{2}\arg(s-\tau). \end{align*} $$

Note that if

![]() $\tau = s$

, then we have

$\tau = s$

, then we have

![]() $a=b$

and Z is a circular element with variance s, having

$a=b$

and Z is a circular element with variance s, having

![]() $\ast $

-distribution independent of

$\ast $

-distribution independent of

![]() $\theta $

.

$\theta $

.

A free additive

![]() $(s,\tau )$

-Brownian motion is a continuous process

$(s,\tau )$

-Brownian motion is a continuous process

![]() $w_{s,\tau }(r)$

with

$w_{s,\tau }(r)$

with

![]() $w_{s,\tau }(0) = 0$

having freely independent increments such that for all

$w_{s,\tau }(0) = 0$

having freely independent increments such that for all

![]() $r_2>r_1$

,

$r_2>r_1$

,

$$\begin{align*}\frac{w_{s,\tau}(r_2)-w_{s,\tau}(r_1)}{\sqrt{r_2-r_1}}\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\frac{w_{s,\tau}(r_2)-w_{s,\tau}(r_1)}{\sqrt{r_2-r_1}}\end{align*}$$

is a rotated elliptic element with parameter s and

![]() $\tau $

. We can construct such an element as

$\tau $

. We can construct such an element as

where

![]() $X_r$

and

$X_r$

and

![]() $Y_r$

are freely independent semicircular Brownian motion and

$Y_r$

are freely independent semicircular Brownian motion and

![]() $a,b,$

and

$a,b,$

and

![]() $\theta $

are chosen as above.

$\theta $

are chosen as above.

Definition 2.4 A free multiplicative

![]() $(s,\tau )$

-Brownian motion

$(s,\tau )$

-Brownian motion

![]() $b_{s,\tau }(r)$

is the solution of the free stochastic differential equation

$b_{s,\tau }(r)$

is the solution of the free stochastic differential equation

with

The

![]() $dr$

term in (2.3) is an Itô correction. Since

$dr$

term in (2.3) is an Itô correction. Since

![]() $w_{s,\tau }(r)$

and

$w_{s,\tau }(r)$

and

![]() $w_{rs,r\tau }(1)$

have the same

$w_{rs,r\tau }(1)$

have the same

![]() $\ast $

-distribution, it follows that

$\ast $

-distribution, it follows that

![]() $b_{s,\tau }(r)$

and

$b_{s,\tau }(r)$

and

![]() $b_{rs,r\tau }(1)$

also have the same

$b_{rs,r\tau }(1)$

also have the same

![]() $\ast $

-distribution. Thus, without loss of generality, we may assume that

$\ast $

-distribution. Thus, without loss of generality, we may assume that

![]() $r=1$

and use the notation

$r=1$

and use the notation

When

![]() $\tau =s$

, the Itô correction vanishes and we find that

$\tau =s$

, the Itô correction vanishes and we find that

Furthermore, when

![]() $\tau =0,$

we have that

$\tau =0,$

we have that

![]() $a = s, b=0=\theta ,$

and

$a = s, b=0=\theta ,$

and

![]() $w_{s,0} = sX_r$

. Then, (2.3) becomes

$w_{s,0} = sX_r$

. Then, (2.3) becomes

This equation is the same SDE for the free unitary Brownian motion

![]() $U_s$

considered by Biane in Section 2.3 of [Reference Biane3]. Therefore, we can identify

$U_s$

considered by Biane in Section 2.3 of [Reference Biane3]. Therefore, we can identify

![]() $b_{s,0}$

with

$b_{s,0}$

with

![]() $U_s$

in [Reference Biane3].

$U_s$

in [Reference Biane3].

Remark 2.1 According to Proposition 6.10 in [Reference Banna, Capitaine and Cébron2], the

![]() $*$

-distribution of

$*$

-distribution of

![]() $b_{s,\tau }$

is unchanged if we reverse the order of the factors on the right-hand side of (2.3), that is, putting the increments on the left instead of the right of

$b_{s,\tau }$

is unchanged if we reverse the order of the factors on the right-hand side of (2.3), that is, putting the increments on the left instead of the right of

![]() $b_{s,\tau }$

. This result is proved by using a matrix approximation to

$b_{s,\tau }$

. This result is proved by using a matrix approximation to

![]() $b_{s,\tau }$

and appealing to a result of Driver [Reference Driver9, Theorem 2.7]. So far as we know, a general proof of this result in the free setting has not appeared. In the case

$b_{s,\tau }$

and appealing to a result of Driver [Reference Driver9, Theorem 2.7]. So far as we know, a general proof of this result in the free setting has not appeared. In the case

![]() $\tau =s$

, however, the result follows from [Reference Driver, Hall, Ho, Kemp, Nemish, Nikitopoulos and Parraud11, Theorem 1.14], using a discrete-time approximation to the SDE defining

$\tau =s$

, however, the result follows from [Reference Driver, Hall, Ho, Kemp, Nemish, Nikitopoulos and Parraud11, Theorem 1.14], using a discrete-time approximation to the SDE defining

![]() $b_{s,s}=b_s$

.

$b_{s,s}=b_s$

.

2.3 The Brown measure

For a normal random variable

![]() $x \in \mathcal {A}$

, we can define the law or distribution of x as a compactly supported probability measure on the plane as follows. The spectral theorem (e.g., [Reference Hall16, Section 10.3]) associates to x a unique projection-valued measure

$x \in \mathcal {A}$

, we can define the law or distribution of x as a compactly supported probability measure on the plane as follows. The spectral theorem (e.g., [Reference Hall16, Section 10.3]) associates to x a unique projection-valued measure

![]() $\nu ^x$

, supported on the spectrum of x, such that

$\nu ^x$

, supported on the spectrum of x, such that

Then, the law

![]() $\mu _x$

of x can be defined as

$\mu _x$

of x can be defined as

for each Borel set A.

If, however, x is not normal, the spectral theorem does not apply. Nevertheless, a candidate for the distribution of a non-normal operator was introduced by Brown [Reference Brown6]. For an operator a, we use the standard notation

![]() $|a|$

for the non-negative square root of

$|a|$

for the non-negative square root of

![]() $a^*a$

.

$a^*a$

.

Definition 2.5 For any

![]() $x\in \mathcal A$

, we define a function

$x\in \mathcal A$

, we define a function

![]() $S:\mathbb C\times (0, \infty )$

by

$S:\mathbb C\times (0, \infty )$

by

and a function

![]() $s:\mathbb C\rightarrow [-\infty , \infty )$

by

$s:\mathbb C\rightarrow [-\infty , \infty )$

by

The following result explains the sense in which the limit defining s should be understood. Although it is possible that the

![]() $L^1_{\mathrm {loc}}$

convergence is known, we have not seen such a result in the literature.

$L^1_{\mathrm {loc}}$

convergence is known, we have not seen such a result in the literature.

Proposition 2.2 Let x be an element of a tracial von Neumann algebra and define a function

![]() $S:\mathbb {C}\times (0, \infty )\rightarrow \mathbb {R}$

by

$S:\mathbb {C}\times (0, \infty )\rightarrow \mathbb {R}$

by

Then,

![]() $S(\lambda ,\varepsilon )$

decreases as

$S(\lambda ,\varepsilon )$

decreases as

![]() $\varepsilon $

decreases, so that

$\varepsilon $

decreases, so that

exists, possibly with the value

![]() $-\infty .$

Then, s is in

$-\infty .$

Then, s is in

![]() $L^1_{\mathrm {loc}}$

and is a subharmonic function. Furthermore, the convergence in (2.4) is

$L^1_{\mathrm {loc}}$

and is a subharmonic function. Furthermore, the convergence in (2.4) is

![]() $L_{\mathrm {loc}}^{1}$

and, therefore, in the distribution sense.

$L_{\mathrm {loc}}^{1}$

and, therefore, in the distribution sense.

The proof will be given after the following definition of the Brown measure (see Section 11.5 of the monograph of Mingo and Speicher [Reference Mingo and Speicher24]).

Definition 2.6 The Brown measure of an element

![]() $x\in \mathcal A$

is defined as the measure

$x\in \mathcal A$

is defined as the measure

![]() $\mu $

computed as

$\mu $

computed as

where

![]() $\Delta $

is the Laplacian in the distribution sense.

$\Delta $

is the Laplacian in the distribution sense.

Remark 2.3 Note that Definition 2.6 does not, by itself, guarantee that s is the log potential of

![]() $\mu $

– that is, the convolution of

$\mu $

– that is, the convolution of

![]() $\mu $

with the function

$\mu $

with the function

![]() $\log (|\lambda |^2)$

. Rather, (2.5) only directly tells us that s is the sum of the log potential of

$\log (|\lambda |^2)$

. Rather, (2.5) only directly tells us that s is the sum of the log potential of

![]() $\mu $

and a harmonic function h. Nevertheless, for large

$\mu $

and a harmonic function h. Nevertheless, for large

![]() $\lambda $

, we can write

$\lambda $

, we can write

![]() $s(\lambda )=\operatorname {tr}[\log (|x-\lambda |^2)]$

without ambiguity, since

$s(\lambda )=\operatorname {tr}[\log (|x-\lambda |^2)]$

without ambiguity, since

![]() $\lambda $

will be outside the spectrum of x. It is then not hard to see that

$\lambda $

will be outside the spectrum of x. It is then not hard to see that

![]() $s(\lambda )=\log (|\lambda |^2)+o(1)$

. The log potential of

$s(\lambda )=\log (|\lambda |^2)+o(1)$

. The log potential of

![]() $\mu $

has the same behavior at infinity, showing that h tends to zero at infinity and must therefore be identically zero. We conclude that s is, actually, the log potential of

$\mu $

has the same behavior at infinity, showing that h tends to zero at infinity and must therefore be identically zero. We conclude that s is, actually, the log potential of

![]() $\mu $

.

$\mu $

.

We now supply the proof of Proposition 2.2.

Proof Let U be a nonempty, open, connected subset of

![]() $\mathbb {R}^{n}.$

A function

$\mathbb {R}^{n}.$

A function

![]() $f:U\rightarrow \lbrack -\infty ,\infty )$

is said to be subharmonic if (1) f is not identically equal to

$f:U\rightarrow \lbrack -\infty ,\infty )$

is said to be subharmonic if (1) f is not identically equal to

![]() $-\infty ,$

(2) f is upper semicontinuous, and (3) the average of f over a sphere centered at

$-\infty ,$

(2) f is upper semicontinuous, and (3) the average of f over a sphere centered at

![]() $x\in U$

is greater than or equal to

$x\in U$

is greater than or equal to

![]() $f(x),$

whenever the sphere is contained in

$f(x),$

whenever the sphere is contained in

![]() $U.$

Such a function f is locally bounded above, because it is upper semicontinuous. Furthermore, f is in

$U.$

Such a function f is locally bounded above, because it is upper semicontinuous. Furthermore, f is in

![]() $L_{\mathrm {loc}}^{1}(U)$

and the distributional Laplacian of f is a non-negative distribution [Reference Hörmander22, Theorem 4.1.8]. If

$L_{\mathrm {loc}}^{1}(U)$

and the distributional Laplacian of f is a non-negative distribution [Reference Hörmander22, Theorem 4.1.8]. If

![]() $f_{n}$

is a weakly decreasing sequence of subharmonic functions on U, the pointwise limit f of

$f_{n}$

is a weakly decreasing sequence of subharmonic functions on U, the pointwise limit f of

![]() $f_{n}$

is easily seen to be subharmonic, provided f is not identically equal to

$f_{n}$

is easily seen to be subharmonic, provided f is not identically equal to

![]() $-\infty .$

(When computing the averages over spheres, apply monotone convergence to

$-\infty .$

(When computing the averages over spheres, apply monotone convergence to

![]() $f_{1}-f_{n}$

.) A smooth function

$f_{1}-f_{n}$

.) A smooth function

![]() $f:U\rightarrow \mathbb {R}$

is subharmonic if and only if the Laplacian of f is non-negative [Reference Azarin1, Theorem 2.6.4.2].

$f:U\rightarrow \mathbb {R}$

is subharmonic if and only if the Laplacian of f is non-negative [Reference Azarin1, Theorem 2.6.4.2].

We now specialize to the case

![]() $n=2$

with

$n=2$

with

![]() $U=\mathbb {C}.$

The function

$U=\mathbb {C}.$

The function

![]() $S(\lambda ,\varepsilon )$

is a smooth function of

$S(\lambda ,\varepsilon )$

is a smooth function of

![]() $\lambda $

for each

$\lambda $

for each

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

and the Laplacian of S with respect to

$\varepsilon>0$

and the Laplacian of S with respect to

![]() $\lambda $

with

$\lambda $

with

![]() $\varepsilon $

fixed is positive [Reference Mingo and Speicher24, Equation (11.8)]. Now, S can be computed as

$\varepsilon $

fixed is positive [Reference Mingo and Speicher24, Equation (11.8)]. Now, S can be computed as

where

![]() $\mu _{\left \vert x-\lambda \right \vert }$

denotes the law (or spectral distribution) of

$\mu _{\left \vert x-\lambda \right \vert }$

denotes the law (or spectral distribution) of

![]() $\left \vert x-\lambda \right \vert .$

After separating the log function into its positive and negative parts and applying monotone convergence to the negative part, we see that

$\left \vert x-\lambda \right \vert .$

After separating the log function into its positive and negative parts and applying monotone convergence to the negative part, we see that

![]() $s(\lambda )$

can be computed as

$s(\lambda )$

can be computed as

Here, the integral of the positive part of the logarithm is finite but the integral of the negative part can be infinite, meaning that the integral is well defined but can equal

![]() $-\infty .$

If

$-\infty .$

If

![]() $\lambda $

is outside the spectrum of

$\lambda $

is outside the spectrum of

![]() $x,$

then

$x,$

then

![]() $\left \vert x-\lambda \right \vert $

is invertible, so the support of

$\left \vert x-\lambda \right \vert $

is invertible, so the support of

![]() $\mu _{\left \vert x-\lambda \right \vert }$

of

$\mu _{\left \vert x-\lambda \right \vert }$

of

![]() $\left \vert x-\lambda \right \vert $

does not include 0. In that case, the integral in (2.6) is finite. We conclude that s is not identically equal to

$\left \vert x-\lambda \right \vert $

does not include 0. In that case, the integral in (2.6) is finite. We conclude that s is not identically equal to

![]() $-\infty $

and is the decreasing limit of subharmonic functions; therefore, s is subharmonic.

$-\infty $

and is the decreasing limit of subharmonic functions; therefore, s is subharmonic.

We now apply Theorem 4.1.9 in [Reference Hörmander22] to the sequence

![]() $f_{n}(\lambda )=S(\lambda ,\varepsilon _{n}),$

for any decreasing sequence

$f_{n}(\lambda )=S(\lambda ,\varepsilon _{n}),$

for any decreasing sequence

![]() $\varepsilon _{n}$

of positive numbers tending to 0. We note that (1)

$\varepsilon _{n}$

of positive numbers tending to 0. We note that (1)

![]() $f_{n}(\lambda )$

is bounded above by

$f_{n}(\lambda )$

is bounded above by

![]() $f_{1}(\lambda )$

and (2) when

$f_{1}(\lambda )$

and (2) when

![]() $\lambda $

is outside the spectrum of

$\lambda $

is outside the spectrum of

![]() $x,$

the sequence

$x,$

the sequence

![]() $f_{n}(\lambda )$

is not tending to

$f_{n}(\lambda )$

is not tending to

![]() $-\infty $

. Then, [Reference Hörmander22, Theorem 4.1.9(a)] tells us that

$-\infty $

. Then, [Reference Hörmander22, Theorem 4.1.9(a)] tells us that

![]() $f_{n}$

has a subsequence that converges in

$f_{n}$

has a subsequence that converges in

![]() $L_{\mathrm {loc}}^{1}$

to some function

$L_{\mathrm {loc}}^{1}$

to some function

![]() $g.$

Then, this subsequence has a sub-subsequence converging pointwise almost everywhere to

$g.$

Then, this subsequence has a sub-subsequence converging pointwise almost everywhere to

![]() $g.$

But the whole sequence

$g.$

But the whole sequence

![]() $f_{n}$

converges pointwise to

$f_{n}$

converges pointwise to

![]() $s,$

which means that

$s,$

which means that

![]() $g=s$

almost everywhere. Finally, we apply a standard argument to the sequence

$g=s$

almost everywhere. Finally, we apply a standard argument to the sequence

![]() $f_{n}$

in the metric space

$f_{n}$

in the metric space

![]() $L^{1}(K),$

for any compact subset K of

$L^{1}(K),$

for any compact subset K of

![]() $\mathbb {C}.$

Since every subsequence will have a convergent sub-subsequence and all the subsequential limits have the same value (namely, s), the entire sequence converges to s in

$\mathbb {C}.$

Since every subsequence will have a convergent sub-subsequence and all the subsequential limits have the same value (namely, s), the entire sequence converges to s in

![]() $L^{1}(K).$

It is then easily seen that

$L^{1}(K).$

It is then easily seen that

![]() $S(\lambda ,\varepsilon )$

converges to s in

$S(\lambda ,\varepsilon )$

converges to s in

![]() $L^{1}(K)$

for every compact set

$L^{1}(K)$

for every compact set

![]() $K.$

$K.$

3 The case

$\tau =s$

$\tau =s$

Recall that we consider the element

![]() $xb_{s,\tau }$

where

$xb_{s,\tau }$

where

![]() $b_{s,\tau }$

is as in Definition 2.4 and where x is non-negative and freely independent of x. We make the standing assumption that x is not the zero operator. We let

$b_{s,\tau }$

is as in Definition 2.4 and where x is non-negative and freely independent of x. We make the standing assumption that x is not the zero operator. We let

![]() $\mu $

denote the law of x as in (2.1). Since

$\mu $

denote the law of x as in (2.1). Since

![]() $x\neq 0$

, the measure

$x\neq 0$

, the measure

![]() $\mu $

will not be a

$\mu $

will not be a

![]() $\delta $

-measure at 0.

$\delta $

-measure at 0.

We begin by analyzing the case in which

![]() $\tau =s$

following the strategy outline in Section 1.2.

$\tau =s$

following the strategy outline in Section 1.2.

3.1 The PDE for the regularized log potential and its solution

Since it is more natural to use t instead of s as the time variable of a PDE, we let

![]() $b_t:= b_{t,t}$

be the free multiplicative Brownian motion as defined in Definitions 2.2 and 2.4. We then let x be a non-negative operator that is freely independent of

$b_t:= b_{t,t}$

be the free multiplicative Brownian motion as defined in Definitions 2.2 and 2.4. We then let x be a non-negative operator that is freely independent of

![]() $b_t$

. We then define

$b_t$

. We then define

Consider the functions S and

![]() $s_t$

defined by

$s_t$

defined by

and

Then, the density of the Brown measure

![]() $W(t,\lambda )$

of

$W(t,\lambda )$

of

![]() $x_t$

can be computed as

$x_t$

can be computed as

The function

![]() $s_t$

is the log potential of the Brown measure, and we refer to the function S as the “regularized log potential.”

$s_t$

is the log potential of the Brown measure, and we refer to the function S as the “regularized log potential.”

We use logarithmic polar coordinates

![]() $(\rho ,\theta )$

defined by

$(\rho ,\theta )$

defined by

so that

![]() $\rho $

is the logarithm of the usual polar radius r. In the case

$\rho $

is the logarithm of the usual polar radius r. In the case

![]() $x=1$

, a PDE for S was derived (in rectangular coordinates) in [Reference Driver, Hall and Kemp10, Theorem 2.7]. This derivation applies without change in our situation, as in [Reference Ho and Zhong21] in the case of a unitary initial condition. We record the result here.

$x=1$

, a PDE for S was derived (in rectangular coordinates) in [Reference Driver, Hall and Kemp10, Theorem 2.7]. This derivation applies without change in our situation, as in [Reference Ho and Zhong21] in the case of a unitary initial condition. We record the result here.

Theorem 3.1 (Driver–Hall–Kemp)

The function S satisfies the following PDE in logarithmic polar coordinates:

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\partial S}{\partial t} = \varepsilon\frac{\partial S}{\partial \varepsilon}\left(1+(|\lambda|^2-\varepsilon)\frac{\partial S}{\partial \varepsilon} - \frac{\partial S}{\partial \rho}\right), \quad \lambda = e^\rho e^{i\theta}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\partial S}{\partial t} = \varepsilon\frac{\partial S}{\partial \varepsilon}\left(1+(|\lambda|^2-\varepsilon)\frac{\partial S}{\partial \varepsilon} - \frac{\partial S}{\partial \rho}\right), \quad \lambda = e^\rho e^{i\theta}, \end{align} $$

with initial condition

where

![]() $\mu $

is the law of non-negative initial condition x.

$\mu $

is the law of non-negative initial condition x.

The PDE (3.2) is a first-order, nonlinear PDE of Hamilton–Jacobi type. We now analyze the solution using the method of characteristics. See Chapters 3 and 10 of the book of Evans [Reference Evans13] for more information. See also Section 5 of [Reference Driver, Hall and Kemp10] for a concise derivation of the formulas that are most relevant to the current problem.

We write

![]() $\lambda = e^\rho e^{i\theta } = r e^{i\theta }$

and define the Hamiltonian corresponding to (3.2) by replacing each derivative of S by a “momentum” variable, with an overall minus sign:

$\lambda = e^\rho e^{i\theta } = r e^{i\theta }$

and define the Hamiltonian corresponding to (3.2) by replacing each derivative of S by a “momentum” variable, with an overall minus sign:

Now, we consider Hamilton’s equations for this Hamiltonian:

$$ \begin{align} \frac{d\rho}{dt} &= \frac{\partial H}{\partial p_\rho},\quad \frac{d\theta}{dt} = \frac{\partial H}{\partial p_\theta},\quad \frac{d\varepsilon}{dt} = \frac{\partial H}{\partial p_\varepsilon}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{d\rho}{dt} &= \frac{\partial H}{\partial p_\rho},\quad \frac{d\theta}{dt} = \frac{\partial H}{\partial p_\theta},\quad \frac{d\varepsilon}{dt} = \frac{\partial H}{\partial p_\varepsilon}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{dp_\rho}{dt} &= -\frac{\partial H}{\partial \rho},\quad \frac{dp_\theta}{dt} = -\frac{\partial H}{\partial \theta},\quad \frac{dp_\varepsilon}{dt} = -\frac{\partial H}{\partial \varepsilon}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{dp_\rho}{dt} &= -\frac{\partial H}{\partial \rho},\quad \frac{dp_\theta}{dt} = -\frac{\partial H}{\partial \theta},\quad \frac{dp_\varepsilon}{dt} = -\frac{\partial H}{\partial \varepsilon}. \end{align} $$

Since the right-hand side of (3.3) is independent of

![]() $\theta $

and

$\theta $

and

![]() $p_\theta $

, it is obvious that

$p_\theta $

, it is obvious that

![]() $d\theta /dt = 0 = dp_\theta /dt.$

Thus,

$d\theta /dt = 0 = dp_\theta /dt.$

Thus,

![]() $\theta $

and

$\theta $

and

![]() $p_\theta $

are independent of t.

$p_\theta $

are independent of t.

To apply the Hamilton–Jacobi method, we take arbitrary initial conditions for the position variables:

Then, the initial conditions for momentum variables,

![]() $p_{\rho ,0} = p_\rho (0), p_\theta = p_\theta (0)$

, and

$p_{\rho ,0} = p_\rho (0), p_\theta = p_\theta (0)$

, and

![]() $ p_0 = p_\varepsilon (0) $

, are chosen as follows:

$ p_0 = p_\varepsilon (0) $

, are chosen as follows:

$$ \begin{align*} p_{\rho,0}(\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0) = \frac{\partial S(0,\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0)}{\partial \rho},\\ p_{\theta}(\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0) = \frac{\partial S(0,\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0)}{\partial \theta}, \\ p_{0}(\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0) = \frac{\partial S(0,\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0)}{\partial \varepsilon}. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} p_{\rho,0}(\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0) = \frac{\partial S(0,\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0)}{\partial \rho},\\ p_{\theta}(\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0) = \frac{\partial S(0,\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0)}{\partial \theta}, \\ p_{0}(\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0) = \frac{\partial S(0,\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0)}{\partial \varepsilon}. \end{align*} $$

Recalling that

![]() $\mu $

is the law of x, we can write the initial momenta explicitly as

$\mu $

is the law of x, we can write the initial momenta explicitly as

$$ \begin{align} p_{\rho,0}(\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0) &= \int_0^{\infty}\frac{2r^2_0 - 2\xi r_0\cos\theta}{|\xi-\lambda_0|^2+\varepsilon_0}\,d\mu(\xi) \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} p_{\rho,0}(\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0) &= \int_0^{\infty}\frac{2r^2_0 - 2\xi r_0\cos\theta}{|\xi-\lambda_0|^2+\varepsilon_0}\,d\mu(\xi) \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} p_{\theta,0}(\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0) &= \int_0^{\infty}\frac{2r_0\xi\sin(\theta)}{|\xi-\lambda_0|^2+\varepsilon_0}\,d\mu(\xi) \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} p_{\theta,0}(\lambda_0, \varepsilon_0) &= \int_0^{\infty}\frac{2r_0\xi\sin(\theta)}{|\xi-\lambda_0|^2+\varepsilon_0}\,d\mu(\xi) \end{align} $$

The following computations will be useful to us.

Lemma 3.2 The Hamiltonian H is a constant of motion for Hamilton’s equations and its value at

![]() $t=0$

may be computed as follows:

$t=0$

may be computed as follows:

where

$$ \begin{align} p_k = \int_0^{\infty}\frac{\xi^k}{|\xi-\lambda_0|^2+\varepsilon_0}\,d\mu(\xi),\quad k=0,2.\end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} p_k = \int_0^{\infty}\frac{\xi^k}{|\xi-\lambda_0|^2+\varepsilon_0}\,d\mu(\xi),\quad k=0,2.\end{align} $$

In the

![]() $k=0$

case of (3.10), we interpret

$k=0$

case of (3.10), we interpret

![]() $\xi ^0$

as being identically equal to 1, even at

$\xi ^0$

as being identically equal to 1, even at

![]() $\xi =0$

. Since we assume

$\xi =0$

. Since we assume

![]() $x\neq 0$

so that

$x\neq 0$

so that

![]() $\mu \neq \delta _0$

, neither

$\mu \neq \delta _0$

, neither

![]() $p_0$

nor

$p_0$

nor

![]() $p_2$

can equal 0.

$p_2$

can equal 0.

Remark 3.3 If

![]() $x=1$

, we find that

$x=1$

, we find that

![]() $p_2=p_0$

, in which case many of the formulas in the remainder of the article simplify greatly. (Observe, for example, the simplification in the formula for

$p_2=p_0$

, in which case many of the formulas in the remainder of the article simplify greatly. (Observe, for example, the simplification in the formula for

![]() $\delta $

in Theorem 3.6 or the formula for T in Definition 3.1 if

$\delta $

in Theorem 3.6 or the formula for T in Definition 3.1 if

![]() $p_2=p_0$

.) Meanwhile, if one considers

$p_2=p_0$

.) Meanwhile, if one considers

![]() $b_t$

with a unitary rather than non-negative initial condition, as in [Reference Ho and Zhong21], one again has

$b_t$

with a unitary rather than non-negative initial condition, as in [Reference Ho and Zhong21], one again has

![]() $p_2=p_0$

, because the quantity

$p_2=p_0$

, because the quantity

![]() $\xi ^2$

in the numerator in (3.10) is really

$\xi ^2$

in the numerator in (3.10) is really

![]() $|\xi |^2$

, which would equal

$|\xi |^2$

, which would equal

![]() $1$

in the unitary case. This observation helps explain why the case of a non-negative initial condition is so much more technically difficult than the case of a unitary initial condition.

$1$

in the unitary case. This observation helps explain why the case of a non-negative initial condition is so much more technically difficult than the case of a unitary initial condition.

Proof The Hamiltonian is easily seen to be a constant of motion for any Hamiltonian system. If

![]() $\lambda _0=r_0e^{i\theta }$

, we compute

$\lambda _0=r_0e^{i\theta }$

, we compute

$$ \begin{align*} (r_0^2 - \varepsilon_0)p_{\varepsilon,0} - p_{\rho,0} &= \int_0^{\infty}\frac{-r^2_0 + 2\xi r_0\cos\theta - \varepsilon_0}{\xi^2 +r_0^2 -2\xi r_0\cos\theta +\varepsilon_0}\,d\mu(\xi)\\ &= -1 + p_2. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} (r_0^2 - \varepsilon_0)p_{\varepsilon,0} - p_{\rho,0} &= \int_0^{\infty}\frac{-r^2_0 + 2\xi r_0\cos\theta - \varepsilon_0}{\xi^2 +r_0^2 -2\xi r_0\cos\theta +\varepsilon_0}\,d\mu(\xi)\\ &= -1 + p_2. \end{align*} $$

Then,

as claimed.

Now, we are ready to solve the PDE using arguments similar to those in [Reference Driver, Hall and Kemp10, Section 5].

Theorem 3.4 Assume

![]() $\lambda _0 \neq 0$

and

$\lambda _0 \neq 0$

and

![]() $\varepsilon _0> 0$

. Suppose a solution to the system (3.4)–(3.5) with initial conditions (3.6)–(3.8) exists with

$\varepsilon _0> 0$

. Suppose a solution to the system (3.4)–(3.5) with initial conditions (3.6)–(3.8) exists with

![]() $\varepsilon (t)> 0$

for

$\varepsilon (t)> 0$

for

![]() $0\leq t \leq T$

. Then,

$0\leq t \leq T$

. Then,

for all

![]() $ 0\leq t <T$

. Moreover, it also satisfies

$ 0\leq t <T$

. Moreover, it also satisfies

$$ \begin{align*} \frac{\partial S}{\partial \varepsilon}(t,\lambda(t),\varepsilon(t)) &= p_\varepsilon(t) \\ \frac{\partial S}{\partial \rho}(t,\lambda(t),\varepsilon(t)) &= p_\rho(t). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \frac{\partial S}{\partial \varepsilon}(t,\lambda(t),\varepsilon(t)) &= p_\varepsilon(t) \\ \frac{\partial S}{\partial \rho}(t,\lambda(t),\varepsilon(t)) &= p_\rho(t). \end{align*} $$

Proof We calculate

$$ \begin{align*} p_\rho\frac{d\rho}{dt} + p_\varepsilon\frac{d\varepsilon}{dt} &= p_\rho\frac{\partial H}{\partial p_\rho} + p_\varepsilon\frac{\partial H}{\partial p_\varepsilon} \\ &= \varepsilon p_\varepsilon - 2H = \varepsilon p_\varepsilon - 2H_0. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} p_\rho\frac{d\rho}{dt} + p_\varepsilon\frac{d\varepsilon}{dt} &= p_\rho\frac{\partial H}{\partial p_\rho} + p_\varepsilon\frac{\partial H}{\partial p_\varepsilon} \\ &= \varepsilon p_\varepsilon - 2H = \varepsilon p_\varepsilon - 2H_0. \end{align*} $$

By Proposition 5.3 in [Reference Driver, Hall and Kemp10], we have

Since

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{d\rho}{dt} = \frac{\partial H}{\partial p_\rho}= \varepsilon p_\varepsilon,\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{d\rho}{dt} = \frac{\partial H}{\partial p_\rho}= \varepsilon p_\varepsilon,\end{align*} $$

we have

Thus, we are done.

3.2 The lifetime of the solution and its

$\varepsilon _0\rightarrow 0$

limit

$\varepsilon _0\rightarrow 0$

limit

We wish to apply the Hamilton–Jacobi method using the strategy outlined in Section 1.2. Thus, we try to choose initial conditions

![]() $\lambda _0$

and

$\lambda _0$

and

![]() $\varepsilon _0$

for the Hamiltonian system (3.4)–(3.5) – with the initial momenta then be determined by (3.6) and (3.7) – so that

$\varepsilon _0$

for the Hamiltonian system (3.4)–(3.5) – with the initial momenta then be determined by (3.6) and (3.7) – so that

![]() $\lambda (t)$

equals

$\lambda (t)$

equals

![]() $\lambda $

and

$\lambda $

and

![]() $\varepsilon (t)$

equals 0. Our strategy for doing this is to choose

$\varepsilon (t)$

equals 0. Our strategy for doing this is to choose

![]() $\varepsilon _0=0$

and

$\varepsilon _0=0$

and

![]() $\lambda _0=\lambda $

, provided that the lifetime of the solution remains greater than t as

$\lambda _0=\lambda $

, provided that the lifetime of the solution remains greater than t as

![]() $\varepsilon $

approaches zero. Thus, we need to determine the lifetime and take its

$\varepsilon $

approaches zero. Thus, we need to determine the lifetime and take its

![]() $\varepsilon \rightarrow 0$

limit.

$\varepsilon \rightarrow 0$

limit.

We will eventually want to let

![]() $\varepsilon _0$

tend to zero in the Hamilton–Jacobi formula (3.11). We will then want to apply the inverse function theorem to solve for

$\varepsilon _0$

tend to zero in the Hamilton–Jacobi formula (3.11). We will then want to apply the inverse function theorem to solve for

![]() $\lambda _0$

and

$\lambda _0$

and

![]() $\varepsilon _0$

in terms of

$\varepsilon _0$

in terms of

![]() $\lambda $

and

$\lambda $

and

![]() $\varepsilon $

. To do this, we need to analyze solutions to the Hamiltonian system (3.4)–(3.5) with

$\varepsilon $

. To do this, we need to analyze solutions to the Hamiltonian system (3.4)–(3.5) with

![]() $\varepsilon _0$

in a neighborhood of 0. Thus, in this section, we allow

$\varepsilon _0$

in a neighborhood of 0. Thus, in this section, we allow

![]() $\varepsilon _0$

to be slightly negative. We emphasize that even though the Hamiltonian system makes sense for negative values of

$\varepsilon _0$

to be slightly negative. We emphasize that even though the Hamiltonian system makes sense for negative values of

![]() $\varepsilon ,$

the Hamilton–Jacobi formula (3.11) is only applicable when

$\varepsilon ,$

the Hamilton–Jacobi formula (3.11) is only applicable when

![]() $\varepsilon (s)>0$

for all

$\varepsilon (s)>0$

for all

![]() $s\leq t$

, because the regularized log potential S is only defined for

$s\leq t$

, because the regularized log potential S is only defined for

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

.

$\varepsilon>0$

.

Lemma 3.5 The quantity

is a constant of motion for the Hamiltonian system (3.4)–(3.5). Then, if we let

![]() $C=2\phi (0)-1$

, we have

$C=2\phi (0)-1$

, we have

for all t. The constant C may be computed as

where

![]() $p_0$

and

$p_0$

and

![]() $p_2$

are defined by (3.10).

$p_2$

are defined by (3.10).

Proof It is an easy computation to show, using (3.4) and (3.5), that

![]() $d\phi /dt=0$

and that

$d\phi /dt=0$

and that

Then, since

![]() $\phi $

is a constant of motion, we obtain the claimed formula for

$\phi $

is a constant of motion, we obtain the claimed formula for

![]() $\varepsilon p_{\varepsilon }^2$

. Meanwhile, we can compute that

$\varepsilon p_{\varepsilon }^2$

. Meanwhile, we can compute that

$$ \begin{align*} 2\phi(0)-1=\int_0^{\infty} \frac{2\varepsilon_0+(2r^2_0 - 2\xi r_0\cos(\theta))-(\xi^2 +r_0^2 -2\xi r_0\cos\theta +\varepsilon_0)}{\xi^2 +r_0^2 -2\xi r_0\cos\theta +\varepsilon_0}\,d\mu(\xi), \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} 2\phi(0)-1=\int_0^{\infty} \frac{2\varepsilon_0+(2r^2_0 - 2\xi r_0\cos(\theta))-(\xi^2 +r_0^2 -2\xi r_0\cos\theta +\varepsilon_0)}{\xi^2 +r_0^2 -2\xi r_0\cos\theta +\varepsilon_0}\,d\mu(\xi), \end{align*} $$

which simplifies to the claimed expression for C.

We are now ready to compute the blow-up time of the solutions to the Hamiltonian system. We recall the definition in (3.10) of the quantities

![]() $p_0$

and

$p_0$

and

![]() $p_2$

.

$p_2$

.

Theorem 3.6 Take

![]() $\lambda _0\neq 0$

with

$\lambda _0\neq 0$

with

![]() $\lambda _0$

outside

$\lambda _0$

outside

![]() $\operatorname {supp}(\mu )$

. As long as

$\operatorname {supp}(\mu )$

. As long as

![]() $\varepsilon _0$

is not too negative, the blow-up time

$\varepsilon _0$

is not too negative, the blow-up time

![]() $t_\ast $

of the system (3.4)–(3.5) is

$t_\ast $

of the system (3.4)–(3.5) is

$$ \begin{align*}t_{\ast} = \frac{1}{r_0\sqrt{p_2p_0} \sqrt{\delta^2-4}}\log\left(\frac{\delta + \sqrt{\delta^2-4}}{\delta - \sqrt{\delta^2-4}}\right),\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}t_{\ast} = \frac{1}{r_0\sqrt{p_2p_0} \sqrt{\delta^2-4}}\log\left(\frac{\delta + \sqrt{\delta^2-4}}{\delta - \sqrt{\delta^2-4}}\right),\end{align*} $$

where

$$ \begin{align} \delta = \frac{p_0r^2_0 + p_2 + p_0\varepsilon_0}{r_0\sqrt{p_2p_0}}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \delta = \frac{p_0r^2_0 + p_2 + p_0\varepsilon_0}{r_0\sqrt{p_2p_0}}. \end{align} $$

If

![]() $\varepsilon _0$

is positive,

$\varepsilon _0$

is positive,

![]() $\varepsilon (t)$

will remain positive for all

$\varepsilon (t)$

will remain positive for all

![]() $t<t_\ast $

.

$t<t_\ast $

.

The precise assumptions on

![]() $\varepsilon _0$

are given in the first paragraph of the proof.

$\varepsilon _0$