Introduction

Svornostite, K2Mg(UO2)2(SO4)4(H2O)8, was described by Plášil et al. (Reference Plášil, Hloušek, Kasatkin, Novák, Čejka and Lapčák2015) from Jáchymov, Czech Republic. They noted that its structure, characterised by [(UO2)(SO4)2(H2O)]2– uranyl-sulfate chains linked by MgO2(H2O)4 octahedra, was very similar to that of a group of synthetic compounds of general formula M2+(UO2)(SO4)2·5H2O (Serezhkin and Serezhkina, Reference Serezhkin and Serezhkina1978). Kampf et al. (Reference Kampf, Sejkora, Witzke, Plášil, Čejka, Nash and Marty2017) described the mineral rietveldite, Fe2+(UO2)(SO4)2(H2O)5, from three localities: the Giveaway–Simplot mine (Utah, USA), the Willi Agatz mine (Saxony, Germany) and Jáchymov. The structures of rietveldite and svornostite were noted to be almost equivalent except that one of the octahedrally coordinated Fe sites and two H2O sites present in the rietveldite structure are missing in the svornostite structure, being replaced by K sites. Kampf et al. (Reference Kampf, Sejkora, Witzke, Plášil, Čejka, Nash and Marty2017) also noted that the structures of rietveldite and the synthetic M2+(UO2)(SO4)2·5H2O compounds are polytypes, rietveldite having approximately double the a cell parameter of the synthetic compounds. Plášil et al. (Reference Plášil, Kampf, Ma and Desor2023) described oldsite, K2Fe2+(UO2)2(SO4)4(H2O)8, from the North Mesa mine group (Utah, USA), which they noted as being the Fe2+ analogue of svornostite. That same year, Kampf et al. (Reference Kampf, Olds, Plášil and Marty2023) described the Zn analogue of rietveldite, zincorietveldite, Zn(UO2)(SO4)2(H2O)5, from the Blue Lizard mine (Utah, USA).

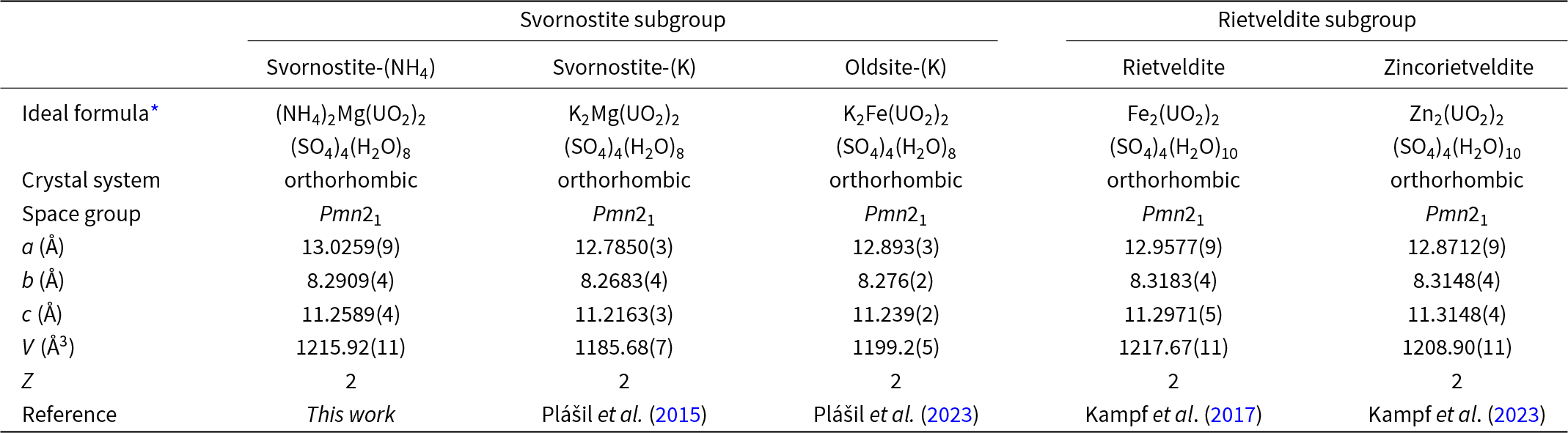

In the current paper, we describe the NH4 analogue of svornostite, (NH4)2Mg(UO2)2(SO4)4(H2O)8, which is named svornostite-(NH4) in line with a new group nomenclature scheme for these closely related minerals. This scheme also involves renaming the original svornostite to svornostite-(K) and the renaming of oldsite to oldsite-(K). The group is to be called the svornostite group and includes two subgroups: (1) the svornostite subgroup with general formula A+2M2+(UO2)2(SO4)4(H2O)8 (Z = 2) and (2) the rietveldite subgroup with general formula M2+(UO2)(SO4)2(H2O)5 (Z = 4), [or M2+2(UO2)2(SO4)4(H2O)10 (Z = 2)], where A is the dominant large monovalent cation and M is the dominant octahedrally coordinated divalent cation. The members of the svornostite subgroup are svornostite-(K), svornostite-(NH4) and oldsite-(K). The members of the rietveldite subgroup are rietveldite and zincorietveldite. The existing members of the group are listed in Table 1 with selected characteristics for comparison. Note that, to minimise changes in already established names, the naming approach for species in the two subgroups differs. For species in the svornostite subgroup, species with different dominant M cations require different root names and the dominant A cation (generally either K or NH4) is appended as a suffix. For species in the rietveldite subgroup, the dominant M cation (other than Fe) is indicated as a prefix to the rootname rietveldite.

Table 1. Comparison of selected data for minerals in the svornostite group

* Note that the formulas of rietveldite and zincorietveldite are given for Z = 2 instead of Z = 4 for the sake of comparison with the other svornostite-group minerals.

The new mineral svornostite-(NH4) and the new group nomenclature were approved by the Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification of the International Mineralogical Association (IMA2024-068, Bosi et al., Reference Bosi, Hatert, Pasero and Mills2025). The description of svornostite-(NH4) is based on four cotype specimens, all micromounts, deposited in the collections of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90007, USA, catalogue numbers 76445, 76446, 76447 and 76448.

Occurrence

Svornostite-(NH4) was first found in 2012 by one of the authors (JM) underground in the Blue Lizard mine (37°33’26”N 110°17’44”W), Red Canyon, White Canyon District, San Juan County, Utah, USA. The mineral was subsequently found at two other mines in the White Canyon district: in 2015 at the Markey mine in Red Canyon and in 2020 at the Scenic mine in Fry Canyon. The description of the mineral is based only on material from the Blue Lizard mine, which is considered the only type locality. The following information on the mine and its geology is taken largely from Chenoweth (Reference Chenoweth1993).

The deposit exploited by the Blue Lizard mine was first recognised in the summer of 1898 by John Wetherill, while leading an archaeological expedition into Red Canyon. He noted yellow stains around a petrified tree. At that spot, he built a rock monument, in which he placed a piece of paper to claim the minerals. Although he never officially recorded his claim, 45 years later, in 1943, he described the spot to Preston V. Redd of Blanding, Utah, who went to the site, found Wetherill’s monument and claimed the area as the Blue Lizzard claim (note alternate spelling). Underground workings to mine uranium were not developed until the 1950s.

The uranium deposits in Red Canyon occur within the Shinarump member of the Upper Triassic Chinle Formation, in channels incised into the reddish-brown siltstones of the underlying Lower Triassic Moenkopi Formation. The Shinarump member consists of medium- to coarse-grained sandstone, conglomeratic sandstone beds and thick siltstone lenses. Ore minerals were deposited as replacements of wood and other organic material and as disseminations in the enclosing sandstone. Since the mine closed in 1978, oxidation of primary ores in the humid underground environment has produced a variety of secondary minerals, mainly sulfates, as efflorescent crusts on the surfaces of mine walls.

Svornostite-(NH4) is a relatively rare mineral found in association with ammoniozippeite, blödite, boussingaultite, gypsum, hexahydrite, kröhnkite, plášilite and quartz. Uranyl sulfate minerals typically form by hydration–oxidation weathering of primary uranium minerals, mainly uraninite, by acidic solutions derived from the decomposition of associated sulfides (Finch and Murakami, Reference Finch, Murakami, P.C. and R.C1999; Krivovichev and Plášil, Reference Krivovichev, Plášil, Burns and Sigmon2013; Plášil, Reference Plášil2014). Svornostite-(NH4) and other secondary minerals occurring in the efflorescent crusts of the mines of Red Canyon have formed by such a process. The (NH4)+ is presumably derived from decaying organic matter and/or from bacterial activity related to the breakdown of the sulfides in the deposit.

Morphology, physical properties and optical properties

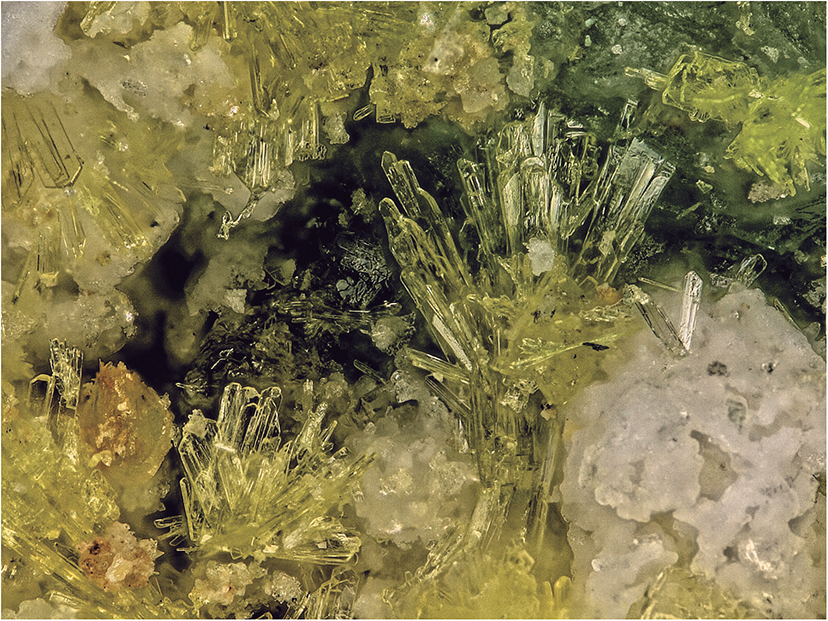

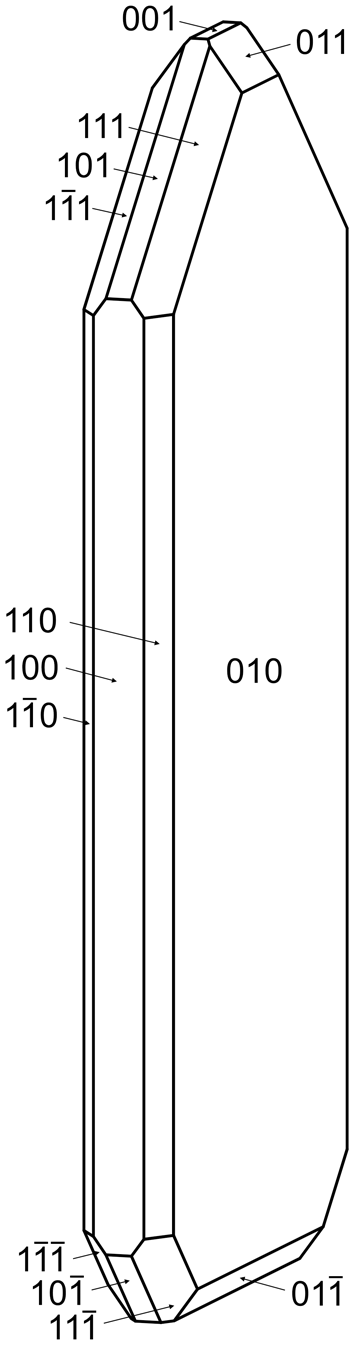

Svornostite-(NH4) occurs in sprays and subparallel groups of yellow blades, up to ∼0.5 mm long (Fig. 1). Blades are elongate on [001], flattened on {010} and exhibit the forms {100}, {010}, {001}, {![]() $00{\overline{1}}$}, {110}, {011}, {

$00{\overline{1}}$}, {110}, {011}, {![]() $01{\overline{1}}$}, {101}, {

$01{\overline{1}}$}, {101}, {![]() ${\overline{1}}0{\overline{1}}$}, {111} and {

${\overline{1}}0{\overline{1}}$}, {111} and {![]() $11{\overline{1}}$} (Fig. 2). Merohedral twinning is likely because of the noncentrosymmetric space group. The mineral does not fluoresce under 405 nm ultraviolet illumination. Crystals are transparent with vitreous lustre. The tenacity is brittle and the fracture is curved. The Mohs hardness is ∼2½ based on scratch tests. Cleavage is excellent on {010}, good on {100} and fair on {001}. The density measured by flotation in a mixture of methylene iodide and toluene is 3.06(2) g·cm–3. The calculated density based upon the empirical formula is 3.097 g·cm–3. The mineral is easily soluble in room-temperature H2O.

$11{\overline{1}}$} (Fig. 2). Merohedral twinning is likely because of the noncentrosymmetric space group. The mineral does not fluoresce under 405 nm ultraviolet illumination. Crystals are transparent with vitreous lustre. The tenacity is brittle and the fracture is curved. The Mohs hardness is ∼2½ based on scratch tests. Cleavage is excellent on {010}, good on {100} and fair on {001}. The density measured by flotation in a mixture of methylene iodide and toluene is 3.06(2) g·cm–3. The calculated density based upon the empirical formula is 3.097 g·cm–3. The mineral is easily soluble in room-temperature H2O.

Figure 1. Yellow blades of svornostite-(NH4) with hexahydrite (white) and plášilite (greenish yellow blades in upper right) on kröhnkite; cotype specimen #76445. The field of view is 1.14 mm across.

Figure 2. Crystal drawing of svornostite-(NH4); clinographic projection. The drawing was created using SHAPE, version 7.4 (Shape Software, Kingsport, Tennessee, USA).

Svornostite-(NH4) is optically biaxial (+) with α = 1.560(2), β = 1.564(2) and γ = 1.589(2) (measured in white light). The measured 2V is 43(1)° from extinction data analysed using EXCALIBRW (Gunter et al., Reference Gunter, Bandli, Bloss, Evans, Su and Weaver2004). The calculated 2V is 44.2°. Dispersion could not be observed. The optical orientation is X = a, Y = b and Z = c. The mineral is pleochroic with X colourless, Y and Z yellow; X < Y ≈ Z. The Gladstone–Dale compatibility (Mandarino, Reference Mandarino2007) 1 – (K p/K c) is –0.008 (superior) based on the empirical formula using k(UO3) = 0.118, as provided by Mandarino (Reference Mandarino1976).

Raman spectroscopy

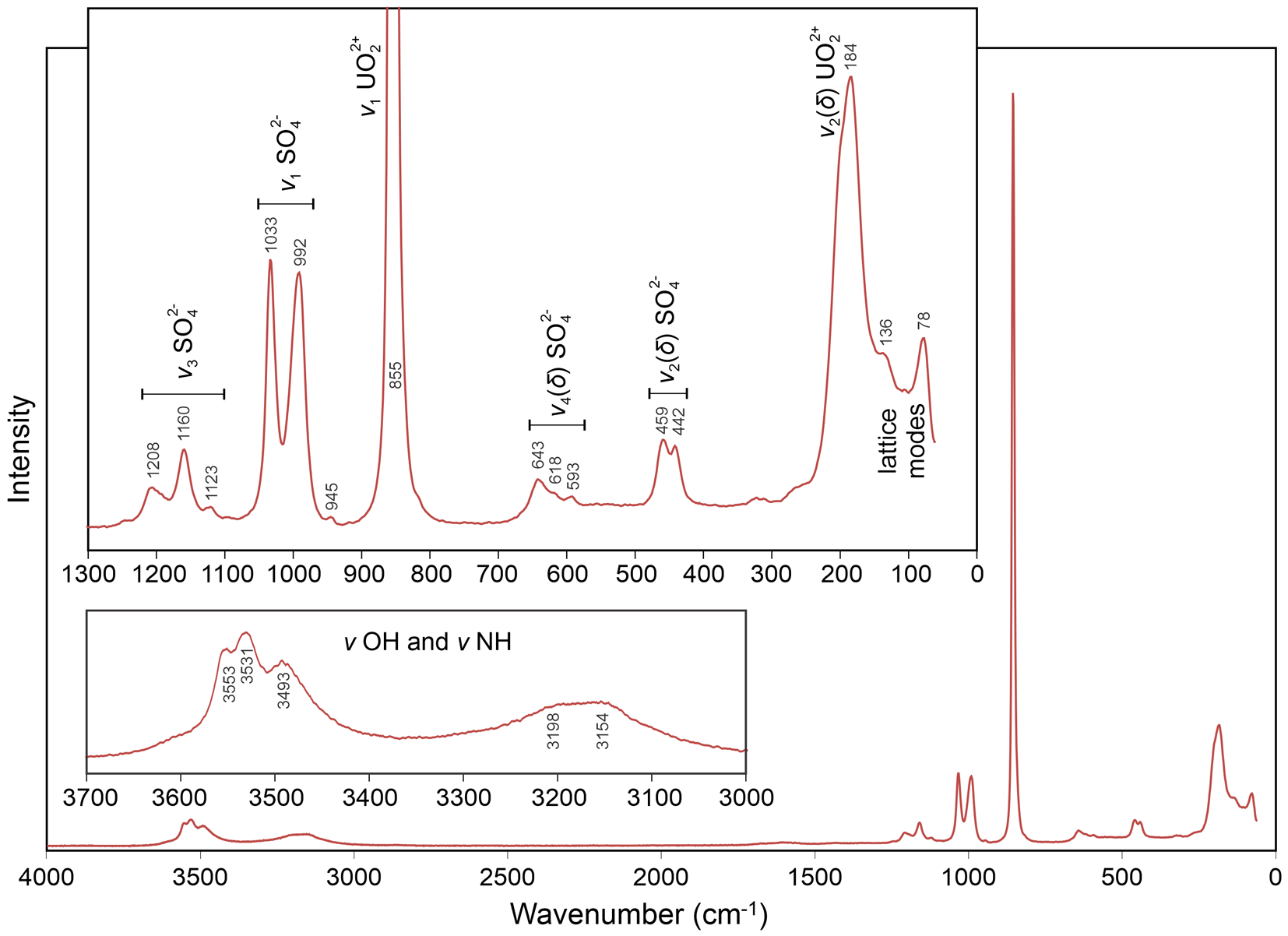

Raman spectroscopy was done on a Horiba XploRa PLUS micro-Raman spectrometer using an incident wavelength of 532 nm, laser slit of 100 μm, 1800 gr/mm diffraction grating and a 100× (0.9 NA) objective. The spectrum, recorded from 4000 to 60 cm–1, is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3. Raman spectrum of svornostite-(NH4).

The spectrum of svornostite-(NH4) is very similar to those of svornostite (Plášil et al., Reference Plášil, Hloušek, Kasatkin, Novák, Čejka and Lapčák2015), oldsite (Plášil et al., Reference Plášil, Kampf, Ma and Desor2023), rietveldite (Kampf et al., Reference Kampf, Sejkora, Witzke, Plášil, Čejka, Nash and Marty2017) and zincorietveldite (Kampf et al., Reference Kampf, Olds, Plášil and Marty2023). The band assignments indicated in Fig. 3 are the same as those previously proposed for svornostite-(K) and oldsite-(K), except that the bands in the 3700–3000 cm–1 range are attributed to both ν OH and ν NH. The broad features at 3198 and 3154 cm–1 are not observed in the spectra of svornostite-(K), oldsite-(K), rietveldite and zincorietveldite and it is likely that these features are related to (NH4)+, which is only found in the structure of svornostite-(NH4). Using the empirically derived equation of Libowitzky (Reference Libowitzky1999), the maxima at 3553, 3531 and 3493 cm–1 are consistent with hydrogen bond O···O distances in the range 2.88–3.00 Å. This matches well with our proposed hydrogen bonding scheme for which 8 of the 14 O···O distances are in the range 2.90 to 3.05 Å (see X-ray crystallography section below). According to the empirical relationship of Bartlett and Cooney (Reference Bartlett and Cooney1989), the ν1 (UO2)2+ band at 855 cm–1 corresponds to an approximate U–OUr bond length of 1.76 Å, in good agreement with U–OUr bond lengths from the X-ray data: 1.762(6) and 1.778(6) Å.

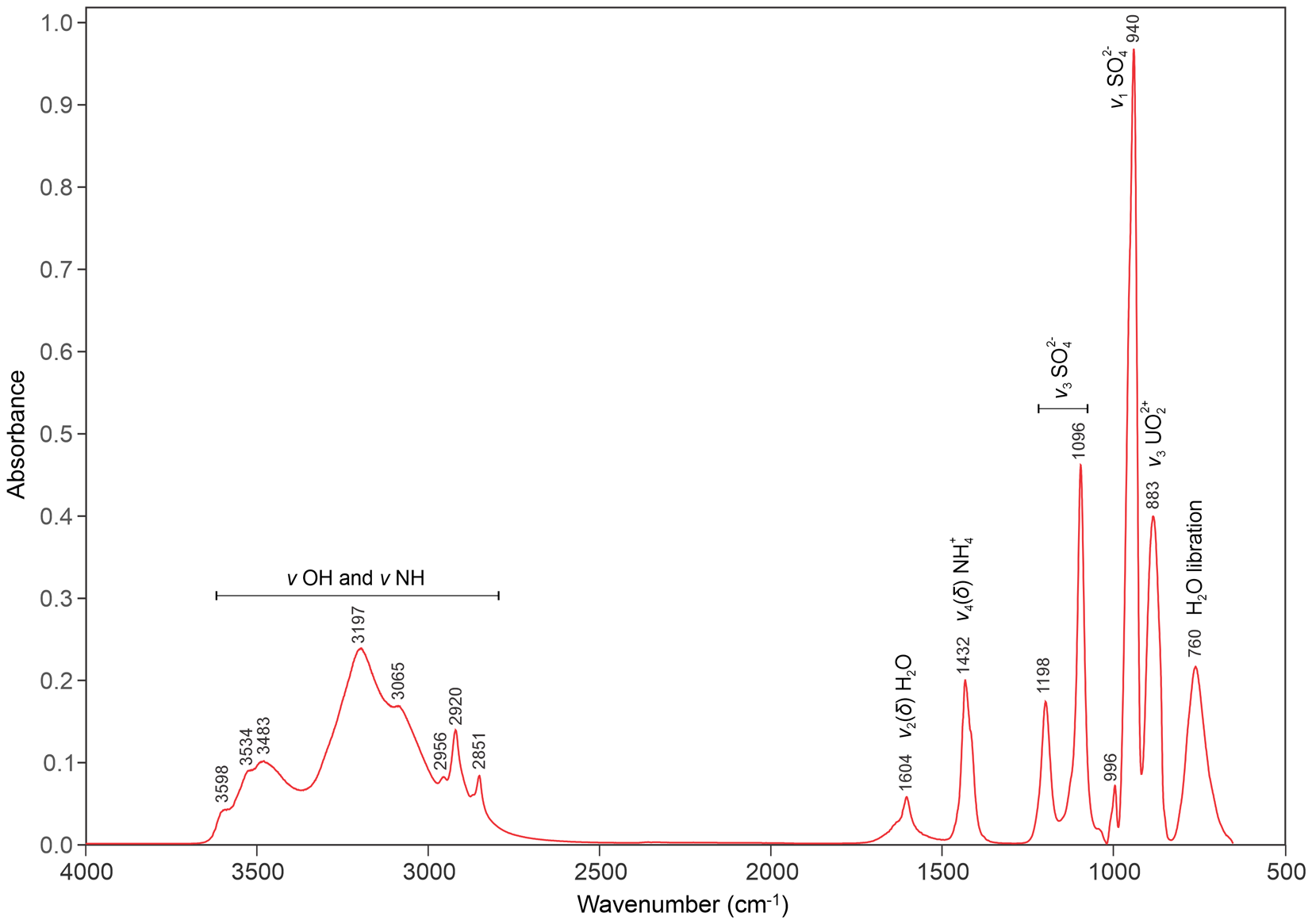

Infrared spectroscopy

Attenuated total reflectance (ATR) Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy for svornostite-(NH4) was done using a liquid N2-cooled SENSIR Technologies IlluminatIR mounted to an Olympus BX51 microscope. An ATR objective (ZnSe) was pressed into a crystal grouping and a spectrum measured from 4000 to 650 cm–1. Band assignments provided in Fig. 4 are based on those of Čejka (Reference Čejka, Burns and Finch1999), Gurzhiy et al. (Reference Gurzhiy, Kasatkin, Chukanov and Plášil2025) and Pekov et al. (Reference Pekov, Krivovichev, Yapaskurt, Chukanov and Belakovskiy2014). Note, in particular, the medium strong band at 1432 cm–1 that is assigned to the N–H bending vibration of (NH4)+ groups.

Figure 4. FTIR spectrum of svornostite-(NH4).

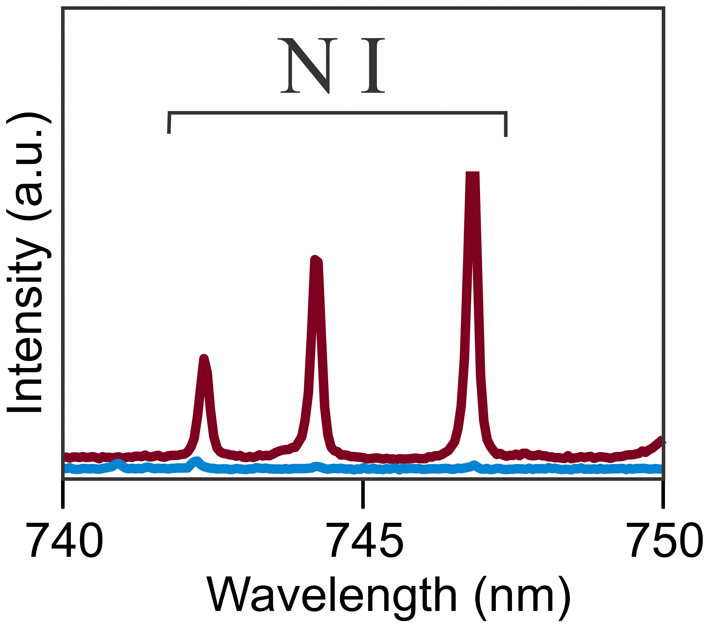

Laser induced breakdown spectroscopy

Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) was done under an argon atmosphere on an Applied Photonics LIBS 8 equipped with a Nitron 1064 nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser operating at 35 mJ and 10 Hz data acquisition. The spectrum was obtained on a tightly intergrown group of svornostite-(NH4) crystals ∼300 μm in diameter. The eight-channel spectrometer collected data from 180 nm to 1022 nm. Peak fitting and identification were performed using the Applied Photonics LIBS instrument software. The portion of the spectrum between 740 and 750 nm where the N I bands appear is shown in Fig. 5. Although quantitation was not attempted, a spectrum for ammoniomathesiusite, (NH4)5(UO2)4(SO4)4(VO5)·4H2O, was recorded for comparison. It was noted that the N I bands in the two spectra are in the same positions and are of similar intensity.

Figure 5. Portion of LIBS spectrum showing N I lines. The red curve is for svornostite-(NH4); the blue curve is the background.

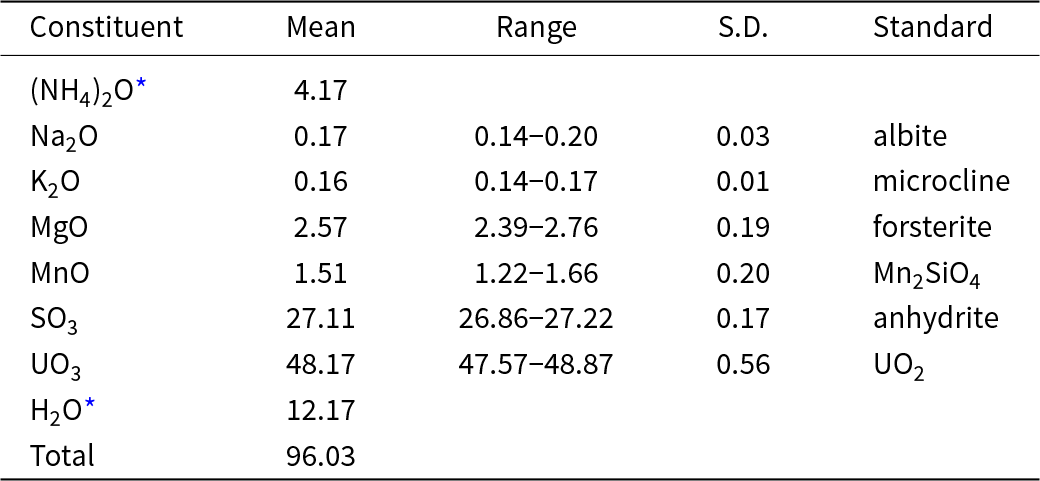

Chemical composition

Chemical analyses (6) were done at Caltech on a JXA-iHP200F electron microprobe in WDS mode. Analytical conditions were 15 kV accelerating voltage, 5 nA beam current and a beam diameter of 10 μm. Because the blades tend to fragment during polishing, analyses were done on unpolished crystal faces. Although all analyses showed a significant amount of NH4 to be present, (NH4)2O values obtained were highly variable and significantly lower than predicted by the structure determination (0.51–0.82 wt.%). The presence of significant amounts of N is strongly indicated by energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), FTIR and LIBS. The standardless EDS analyses were consistent with N:(Mg+Mn) ≈ 2. The structure indicates that NH4 and some of the H2O are relatively weakly bonded, so it is to be expected that much of these constituents are lost during the EPMA. Insufficient material is available for CHN analysis, so (NH4)2O and H2O are calculated based on the structure (U+S = 6 and O = 28 atoms per formula unit). The low analytical total can be attributed to the fact that the analyses were done on unpolished crystal faces, which exhibited some roughness and were not lying perfectly level. The analytical results are given in Table 2. It should be noted that the possible presence of H3O+ substituting for NH4+ was discounted because no hydronium-bearing phases have been found in any of the post-mining mineral assemblages in the Blue Lizard mine, or in any of the Red Canyon mines, for that matter.

Table 2. Analytical data (in wt.%) for svornostite-(NH4)

* Based on structure; S.D. – standard deviation

The empirical formula (based on 28 O apfu) is [(NH4)1.895Na0.065K0.040]Σ2.000(Mg0.755Mn0.252)Σ1.007(U0.996O2)2(S1.002O4)4(H1.998O)8. The simplified formula is [(NH4),Na,K]2(Mg,Mn)(UO2)(SO4)2(H2O)8. The ideal formula is (NH4)2Mg(UO2)2(SO4)4(H2O)8, which requires (NH4)2O 4.61, MgO 3.57, UO3 50.68, SO3 28.37, H2O 12.77, total 100 wt.%.

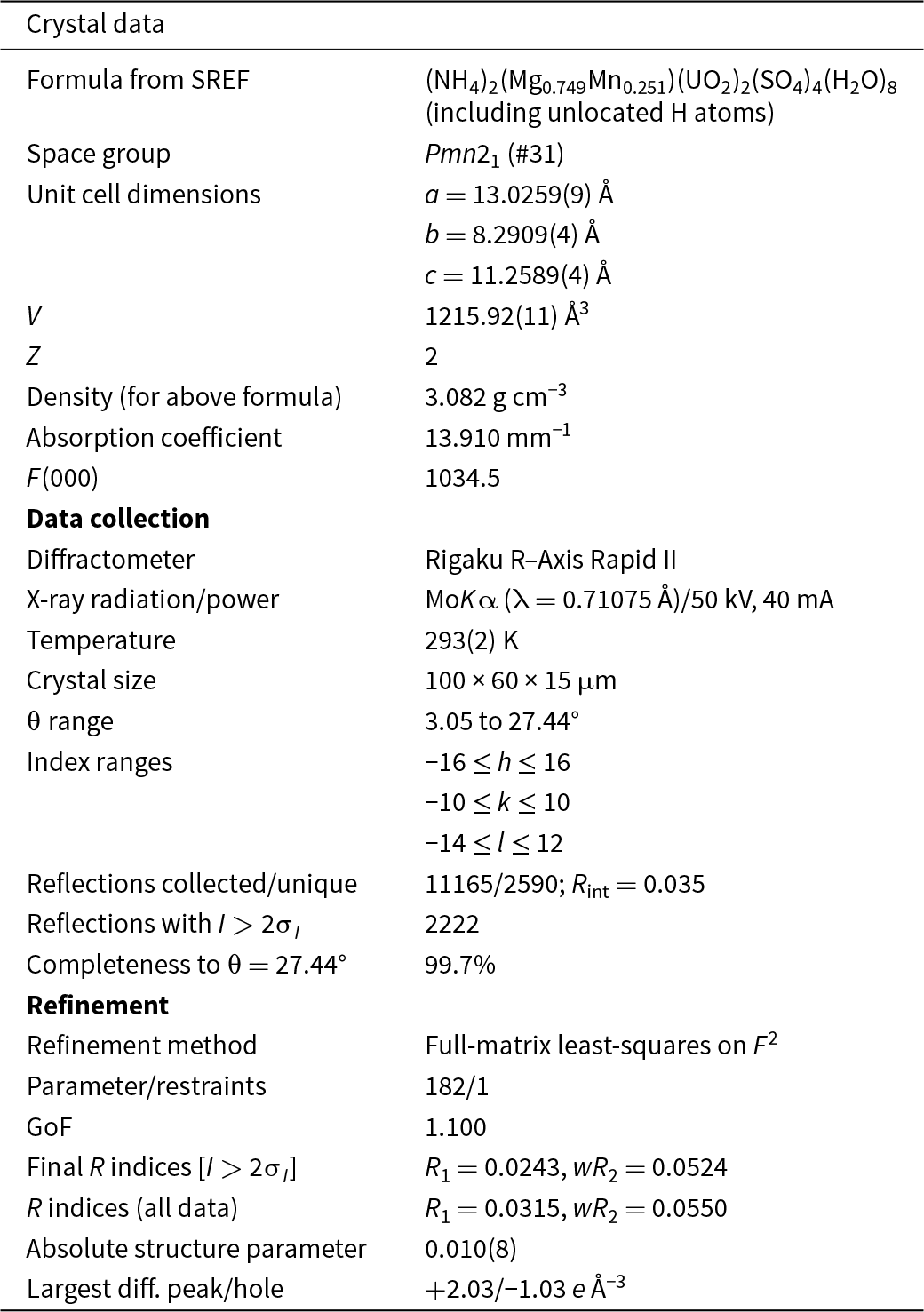

X-ray crystallography

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) data were recorded using a Rigaku R-Axis Rapid II curved imaging plate microdiffractometer with monochromatised MoKα radiation. A Gandolfi-like motion on the φ and ω axes was used to randomise the sample. Observed d values and intensities were derived by profile fitting using JADE Pro software (Materials Data, Inc.). The powder data are presented in Supplementary Table S1. The unit-cell parameters refined from the powder data using JADE Pro with whole pattern fitting are (space group Pmn21) a = 13.044(3), b = 8.2948(18), c = 11.259(2) Å and V = 1218.2(4) Å3.

The single-crystal structure data were collected at room temperature using the same diffractometer and radiation noted above. The Rigaku CrystalClear software package was used for processing the structure data, including the application of an empirical absorption correction using the multi-scan method with ABSCOR (Higashi, Reference Higashi2001). Systematic absences and E statistics indicated the noncentric space group Pmn21 (#31). The structure was solved using the intrinsic-phasing algorithm of SHELXT (Sheldrick, Reference Sheldrick2015a). SHELXL-2016 (Sheldrick, Reference Sheldrick2015b) was used for the refinement of the structure. The structure solution located all non-hydrogen atoms, which were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. The N1 and N2 sites were refined with full occupancies by N only. The Mg site was refined with joint occupancies by Mg and Mn yielding Mg0.749(16)Mn0.251(16), almost exactly matching the EPMA results: (Mg0.755Mn0.252). The H atom locations could not be found in the difference-Fourier maps. The two highest electron density residuals, 2.03 and 1.75 e Å–3, are at distances of 0.90 and 0.98 Å, respectively, from the U site, indicating that the absorption correction was not completely successful. Data collection and refinement details are given in Table 3, atom coordinates and displacement parameters in Table 4, selected bond distances in Table 5 and a bond-valence analysis in Table 6. The crystallographic information file has been deposited with the Principal Editor of Mineralogical Magazine and is available as Supplementary material (see below).

Table 3. Data collection and structure refinement details for svornostite-(NH4)

Notes: R int = Σ|F o2–F o2(mean)|/Σ[F o2]. GoF = S = {Σ[w(F o2–F c2)2]/(n–p)}1/2. R 1 = Σ||F o|–|F c||/Σ|F o|. wR 2 = {Σ[w(F o2–F c2)2]/Σ[w(F o2)2]}1/2; w = 1/[σ2(F o2)+(aP)2+bP] where a is 0.019, b is 2.134 and P is [2F c2+Max(F o2,0)]/3.

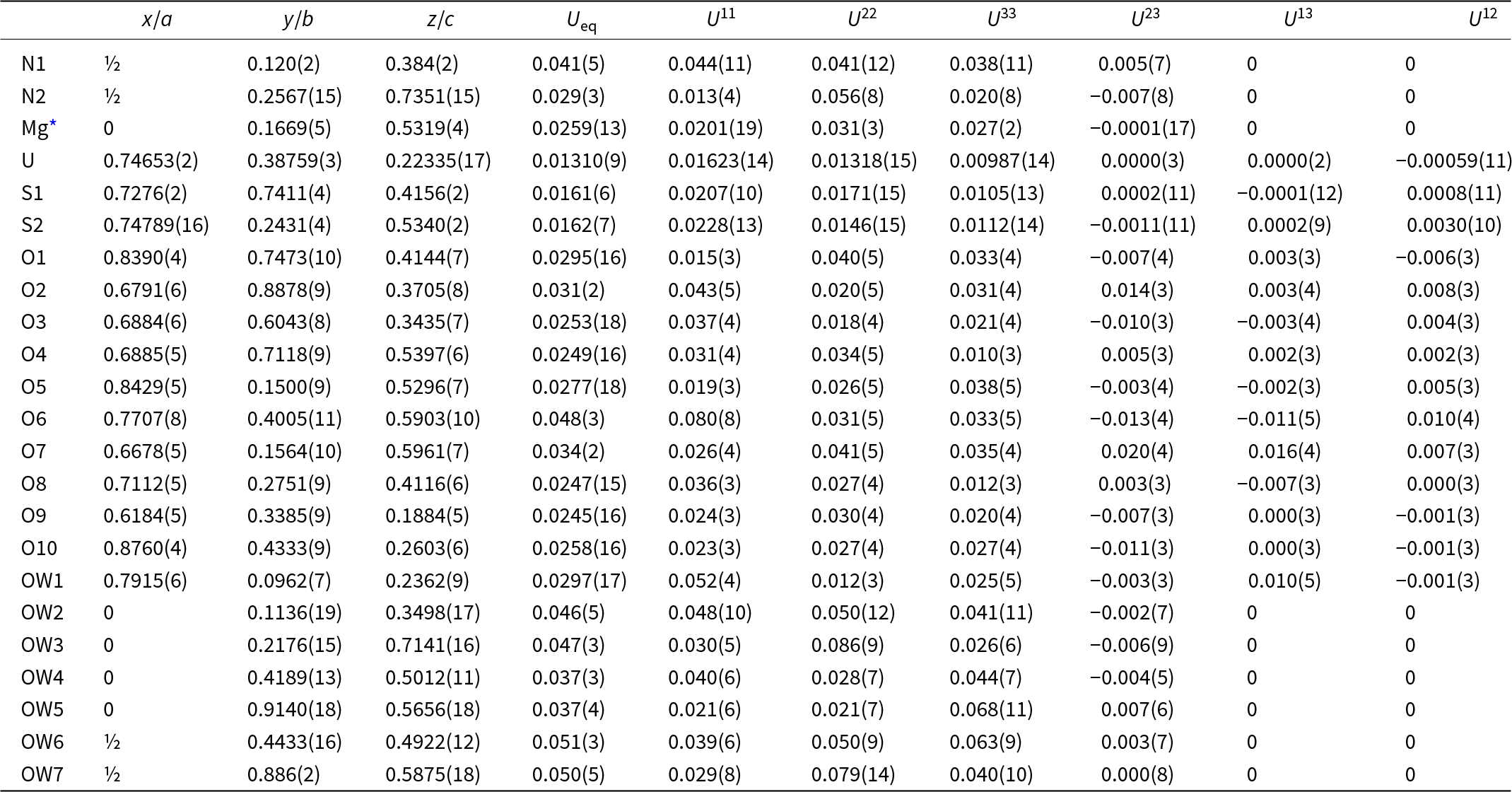

Table 4. Atom coordinates and displacement parameters (Å2) for svornostite-(NH4)

* Refined occupancy: Mg0.749(16)Mn0.251(16)

Table 5. Selected bond distances (Å) for svornostite-(NH4)

Table 6. Bond valence analysis for svornostite-(NH4). Values are expressed in valence units.*

* Multiplicity is indicated by ×→↓. NH4+–O bond–valence parameters from García-Rodríguez et al. (Reference García-Rodríguez, Á, Piñero and González–Silgo2000). Mg2+–O, U6+–O and S6+–O bond-valence parameters are from Gagné and Hawthorne (Reference Gagné and F.C2015). Hydrogen–bond strengths based on O–O bond lengths from Ferraris and Ivaldi (Reference Ferraris and Ivaldi1988).

Description of the structure

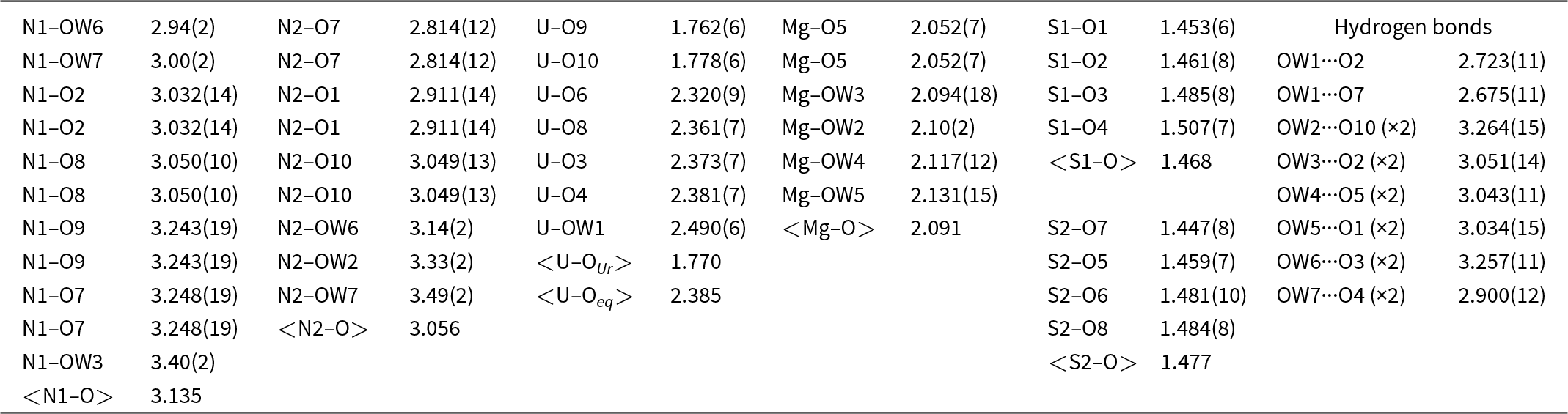

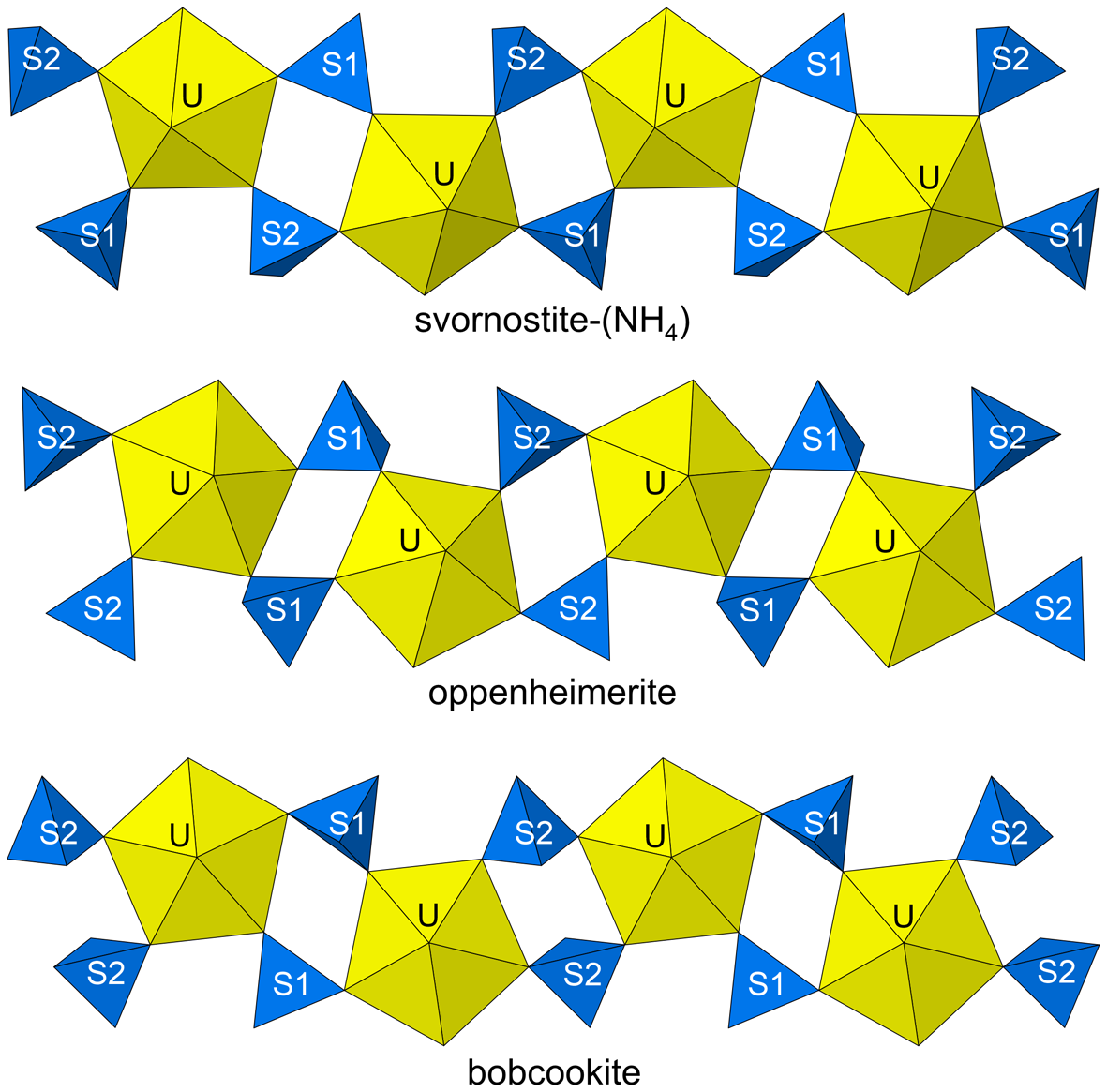

In the structure of svornostite-(NH4), the U site is surrounded by seven O atoms forming a squat UO7 pentagonal bipyramid. This is the most typical coordination for U6+, particularly in uranyl sulfates, where the two short apical bonds of the bipyramid constitute the uranyl group. Four of the five equatorial O atoms of the UO7 bipyramid participate in SO4 tetrahedra; the other is an H2O group. The linkages of pentagonal bipyramids and tetrahedra form an infinite [(UO2)(SO4)2(H2O)]2– chain along [001] (Fig. 6). The chains are linked in the [100] direction by MgO2(H2O)4 octahedra, which share O vertices with SO4 tetrahedra in the chains. A heteropolyhedral sheet parallel to {010} is thereby formed. Two (NH4)+ cations form bonds with O atoms in the chains and octahedra thereby linking the structure in three dimensions (Fig. 7). A network of hydrogen bonds further links the structure.

Figure 6. The uranyl sulfate chains in the structures of svornostite-(NH4), oppenheimerite and bobcookite.

Figure 7. The structures of svornostite-(NH4) and rietveldite viewed down [010]. The unit-cell outline is shown by dashed lines. The figures were created using ATOMS, version 6.5 (Shape Software, Kingsport, Tennessee, USA).

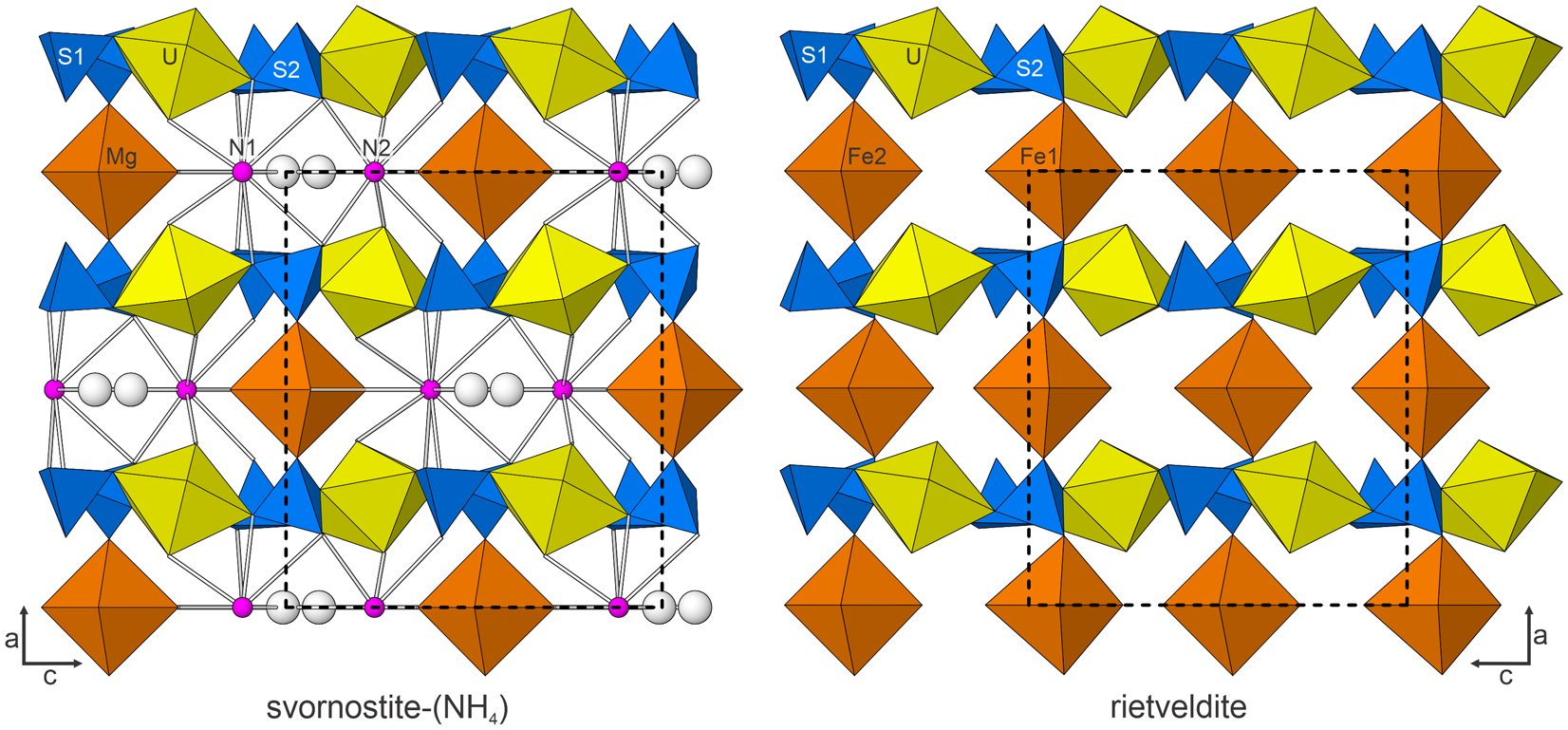

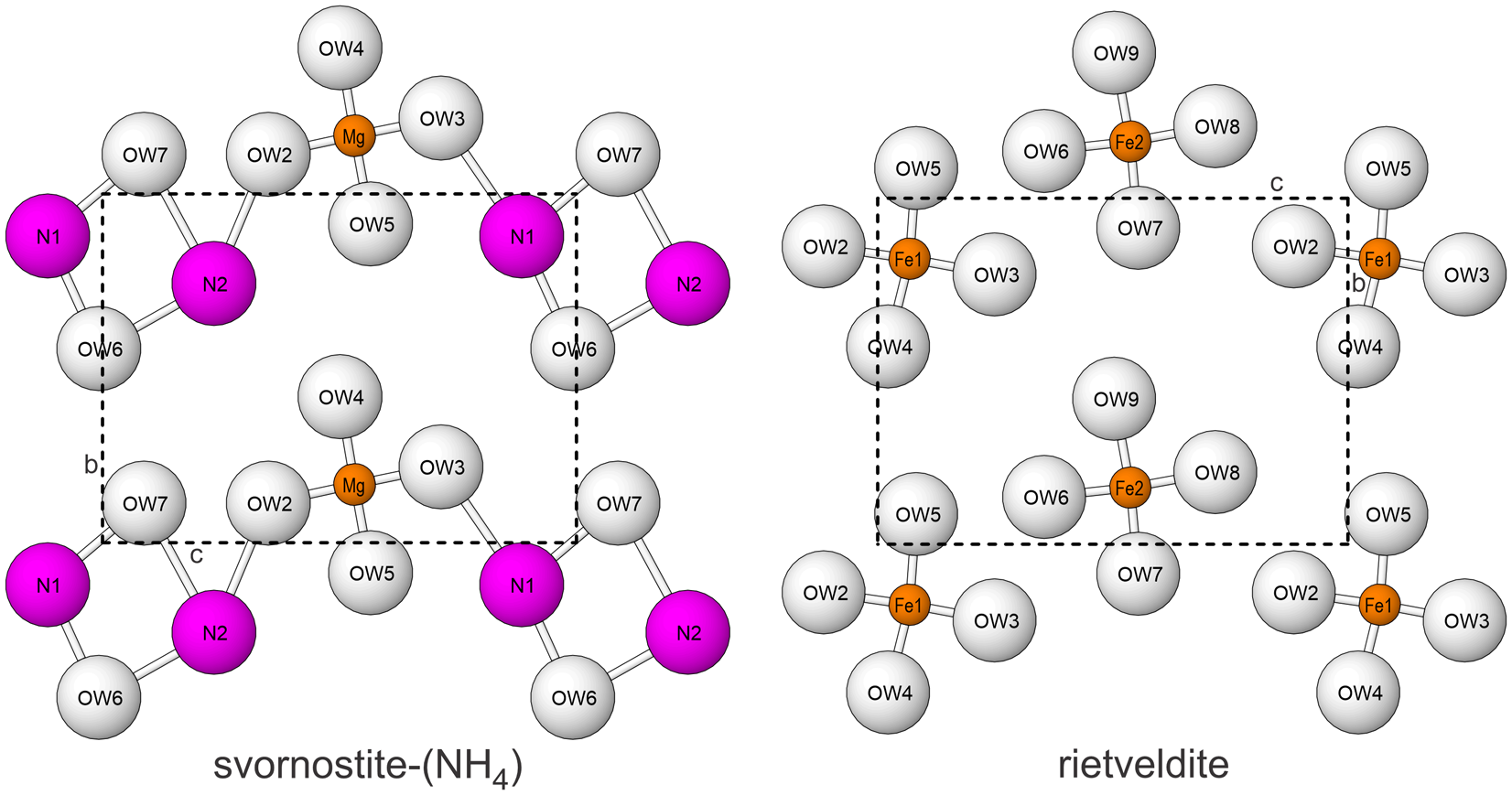

Svornostite-(NH4), is isostructural with svornostite-(K), K2Mg[(UO2)(SO4)2]2(H2O)8 (Plášil et al., Reference Plášil, Hloušek, Kasatkin, Novák, Čejka and Lapčák2015) and oldsite-(K), K2Fe2+[(UO2)(SO4)2]2(H2O)8 (Plášil et al., Reference Plášil, Kampf, Ma and Desor2023). The structures of these three minerals are almost the same as those of rietveldite, Fe2(UO2)2(SO4)4(H2O)10 (Kampf et al., Reference Kampf, Sejkora, Witzke, Plášil, Čejka, Nash and Marty2017), and zincorietveldite, Zn2(UO2)2(SO4)4(H2O)10 (Kampf et al., Reference Kampf, Olds, Plášil and Marty2023); however, there are two octahedrally coordinated divalent cation sites in the structures of rietveldite and zincorietveldite and only one in the structures of svornostite-(NH4), svornostite-(K) and oldsite-(K). Additionally, two H2O groups in the rietveldite and zincorietveldite structures are replaced with K or (NH4)+ cations in the svornostite-(NH4), svornostite-(K) and oldsite-(K) structures. The structures of rietveldite and svornostite-(NH4) are compared in Fig. 6, but the differences (and similarities) are more readily appreciated by comparing the x = 0 layers of the structures (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. The x = 0 layers in the structures of svornostite-(NH4) and rietveldite. Note that the N1 and N2 sites are depicted as large balls to represent the large size of the NH4 groups, which are in approximately the same locations as the K cations in the svornostite-(K) and oldsite-(K) structures. The unit-cell outlines are shown by dashed lines.

The [(UO2)(SO4)2(H2O)]2– chains are essentially identical in the svornostite-(NH4), svornostite-(K), oldsite-(K), rietveldite and zincorietveldite structures. Topologically identical chains are also found in the structures of bobcookite, Na(H2O)2Al(H2O)6[(UO2)2(SO4)4(H2O)2]·8H2O (Kampf et al., Reference Kampf, Plášil, Kasatkin and Marty2015a), oppenheimerite, Na2(H2O)2[(UO2)(SO4)2(H2O)] (Kampf et al., Reference Kampf, Plášil, Kasatkin, Marty and Čejka2015b), synthetic K2[(UO2)(SO4)2(H2O)](H2O) (Ling et al., Reference Ling, Sigmon, Ward, Roback and Burns2010) and synthetic Mn(UO2)(SO4)2(H2O)5 (Tabachenko et al., Reference Tabachenko, Serezhkin, Serezhkina and Kovba1979). The chains in oppenheimerite and bobcookite are geometrical isomers of the chain in the structures of the svornostite-(NH4), svornostite-(K), oldsite-(K), rietveldite and zincorietveldite (Fig. 6).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1180/mgm.2025.19.

Acknowledgements

Structures Editor Peter Leverett and two anonymous reviewers are thanked for their constructive comments on the manuscript.

Funding statement

The EPMA was carried out at the Caltech GPS Division Analytical Facility, which is supported, in part, by NSF Grant EAR-2117942. T.O. was supported by the Henry L. Hillman Foundation. This study was funded, in part, by the John Jago Trelawney Endowment to the Mineral Sciences Department of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.