There is a significant enchantment with the figure of the ‘peasant’ in modern Indian history. This enchantment continues its penetration into other ways of history writing, for example, urban history. Any study of the formation of colonial cities in India must also contend with the literature produced in the field of labour studies.Footnote 1 The emergence of colonial cities in India rested on the economic interests of the British empire. However, all such initiatives, being labour intensive, depended on substantial migration from other regions. This resulted in the mass arrival of skilled and unskilled labourers from nearby regions to the city. The city emerged as a place that offered employment away from the clutches of village landowners and the permanent exploitation of caste relations. Here, lucrative opportunities for transacting physical labour or artisanal skills were available, which directly generated a wage. It soon became the place of dwelling for migrant labour, where working-class neighbourhoods based on caste, religion and occupational lines formed and offered a space for belonging in the city. The factory served as a site for them to engage their labour and build social and political ties. Yet given the increasing interdependency of capital and labour in the colonial city, the context of the urban and notions of urbanity prioritized bourgeois civic sensibilities, which overwhelmingly shied away from acknowledging the resourcefulness of migrant workers and the neighbourhoods they inhabited.

This article engages with protracted worker agitation in the 1930s in Kanpur (often appearing as Cawnpore in colonial records), an industrial city in the United Provinces of British colonial India. This agitation is important because it snowballed into a broader militant action spread across factories in Kanpur city, mobilizing thousands of workers to go on strike and demand various rights. Kanpur became one of the main sites of worker activism in the United Provinces. Scholars have noted an increase of 31.2 per cent in the city’s total number of mill workers during 1930–37.Footnote 2 Therefore, the Kanpur agitation is crucial to understanding northern India’s labour and urban history in the early twentieth century. Workers’ militancy in Kanpur reveals that the urban environment in colonial India was discursive. Precarity led to the formation of a collective identity among workers. Worker grievances and their corresponding militant mobilization appeared prominently in newspaper reporting.

Workers in Kanpur transformed its atmosphere by making class interest the dominant public discourse, thus directly disrupting the existing power structures in the city. Scholars have noted that across cities in India, especially during the first quarter of the twentieth century, colonial administrations tended to criminalize the ‘urban poor’.Footnote 3 Working-class mobilization advanced a new plebeian political culture that undermined colonial expectations of a direct and disciplined wage–labour relationship and expanded the scope of worker politics beyond the confines of the factory. Kanpur agitation represented a militant possibility of inserting the demands of the urban poor into the socio-political and economic milieu of the city. It reconfigured the colonial aims and objectives of urban growth in India. The Kanpur confrontations allow us to focus on the potential of neighbourhoods to unmask the nature of political life in the city. Working-class neighbourhoods in Kanpur defied the separation between the local, regional and national and actively engaged in building community dynamics through a notion of class solidarity. The pressure of class politics in the United Provinces was such that the Congress Socialist Party was floated in May 1934 within the larger Congress Party to highlight the concerns of peasants and the working classes.

This article lays bare the precarious condition of workers and aims to recreate the cityscape of Kanpur in the 1930s in the context of municipal and provincial politics. Against tendencies that look at the city in limited and quantifiable terms only, scholars have insisted that space is a social dynamic in constant movement.Footnote 4 A historical approach can help comprehend the social, emotive and experiential associations of urban space by way of political mobilizations against the exploitative disciplinary urges of industry. Through the Kanpur example, this article highlights working-class strikes as a powerful mode of collective action. Strikes aimed to recalibrate everyday practices and perceptions, representations and the spatial imagination of time in the city by directly inserting workers’ demands for a dignified life, both inside and outside the factory, into the broader public discourse. It will show that urban proximity and precarity fostered labour militancy. The article uses newspaper reports and government records to track the agitation. It relies substantially on the reporting by The Leader, an influential English-language pro-Congress newspaper in late colonial India. It was founded by Madan Mohan Malviya in 1909 and was run by C.Y. Chintamani until 1934. Malviya was a Congress stalwart but had Hindu-nationalist tendencies. He hailed from Allahabad in the United Provinces and was elected as Congress president in 1909, 1918 and again in 1932. Chintamani, on the other hand, was a renowned journalist from Vizianagaram who also became a liberal politician duly recognized by the British colonial government in India. Chintamani was the editor-in-chief of The Leader from 1909 to 1934. He was the leader of the opposition in the United Provinces Legislative Council until the provincial elections of 1937 were declared. Chintamani sympathized with the Congress but pursued his editorial freedom vigorously, which is reflected in the coverage of the Kanpur protests. By using newspaper reports from The Leader, the article aims to reveal the complicated relationship between politics in the city of Kanpur and provincial politics after the arrival of the Government of India Act 1935.

This research engages with the question of the colonial city by reiterating the impossibility of a compartmentalized and sanitized notion of urbanity.Footnote 5 It positions itself within the scholarship that has revealed the constitution of colonial urbanity in India as contingent upon the countryside.Footnote 6 This observation is reinforced when we examine the urban–rural migration patterns in Indian colonial history.Footnote 7 Such a migration fuelled industrialization, urbanization and economic growth and was also perceived as a natural process of modernization in the colony. As the process unfolded across various stages, the ‘urban poor’ claimed their right to the city based on their understanding of their political and social rights in their ‘native’ villages. Scholars engaging with colonial urbanity in India have pointed to the connection between the precarious condition of labour and its subsequent impact on emergent nationalist politics in the 1920s and 1930s.Footnote 8 The political leanings and gradations (skilled/unskilled or permanent/casual worker) among the migrant workers became visible in the context of factory work. Workers increasingly perceived the city as a place generating precarity as a standard condition of existence, and the issue of permanent inequality was seen as a shared experience among the urban poor. Hence, the city became a site of everyday cultural and socio-political expression.

Within this colonial urban reality, the urban poor’s space of precarious dwelling, the basti (working-class settlement), is important to understanding the dynamic processes of political mobilization. It was a liminal space between home and the alienated city, generating a spatially immersed social life.Footnote 9 Given the context of urban proximity and precarity, this liminal space offered both assurance and anxiety, the possibility of both solidarity and marginalization. The basti became an urban ecological niche where issues of inequality and alienation created solidarity and triggered the cultivation of militancy among the urban poor. It was an enclave where strategies for their socio-political and economic survival in the city took shape. Yet the constitution of the basti as a space in urban conflicts is revealed initially in the context of peasant politics in the countryside of the United Provinces.

Kanpur: segregation and control in the colonial cityscape

Kanpur emerged as an urban and commercial centre of the East India Company after 1778 under the protective presence of British forces. Scholars have noted that the British ‘distorted Indian economic patterns by orienting trade to the metropolitan market’.Footnote 10 However, settlements inhabited by artisans and the labouring population were in evidence in Kanpur even before the arrival of the East India Company factories. The establishment of the cantonment in 1811 led to the further expansion of such settlements.Footnote 11 During the famine years of the 1830s, a large number of migrants arrived from Bundelkhand and were employed by the East India Company or other establishments as coolie labour. By the mid-nineteenth century, more than 16,000 artisans and workers were engaged in leather works, weaving, tailoring and other activities in Kanpur city and the surrounding cantonment. The cantonment was controlled and managed by the military. By 1848, it spread across 6,477 acres of land in Kanpur, in contrast to only 690 acres remaining under civil administration. The main business in the city revolved around fulfilling military demands or supplying cotton twists and yarn to weavers from northern India. Kanpur also rapidly emerged as a distribution point for cotton yarn, textiles, piece goods, grain, sugar, oil, oilseeds and animal hide skins. It was an important centre during the great uprisings of 1857 when a failed revolt occurred against British rule in India.Footnote 12 After 1857, the town was restructured. An expanded cantonment along with new civil boundaries and district offices were added to the city. Soon, Kanpur became an important manufacturing centre in the United Provinces. The cantonment rapidly emerged as the largest neighbourhood with an imposing imperial presence with the arrival of the railways in the 1860s.

The development of Kanpur as an urban centre was initiated by British merchants who were also owners of the mills and factories. However, it was catalysed by indigenous bankers (a slightly sophisticated form of traditional money lending primarily based on loans) who became small-scale industrial entrepreneurs during the nineteenth century.Footnote 13 Tirthankar Roy has observed that a ‘combination of family proprietorship and corporate identity…enabled some of the trading houses to use flexible strategies, conserve limited managerial resources, and mitigate transaction costs that remote management entailed’.Footnote 14 Formal legal identity, such as that of a firm or enterprise, made possible by the commercial laws of the British empire, enabled small businesses in towns and cities to venture in new directions where they were connected to the growing multinational trade. Chitra Joshi has noted that by the 1820s, Kanpur had around 50 banking houses, mostly drawn from other declining centres such as Farrukhabad in the United Provinces.Footnote 15 Among these, the Marwari banking family of Baijnath Ramnath was most prominent, and later went on to establish various mills in Kanpur under the name of Juggilal Kamlapat Enterprises. Tulsi Ram Jia Lal, Nihal Chand Baldeo Sahai and Janki Das Jagannath were indigenous banking families of Kanpur who also traded in grains.

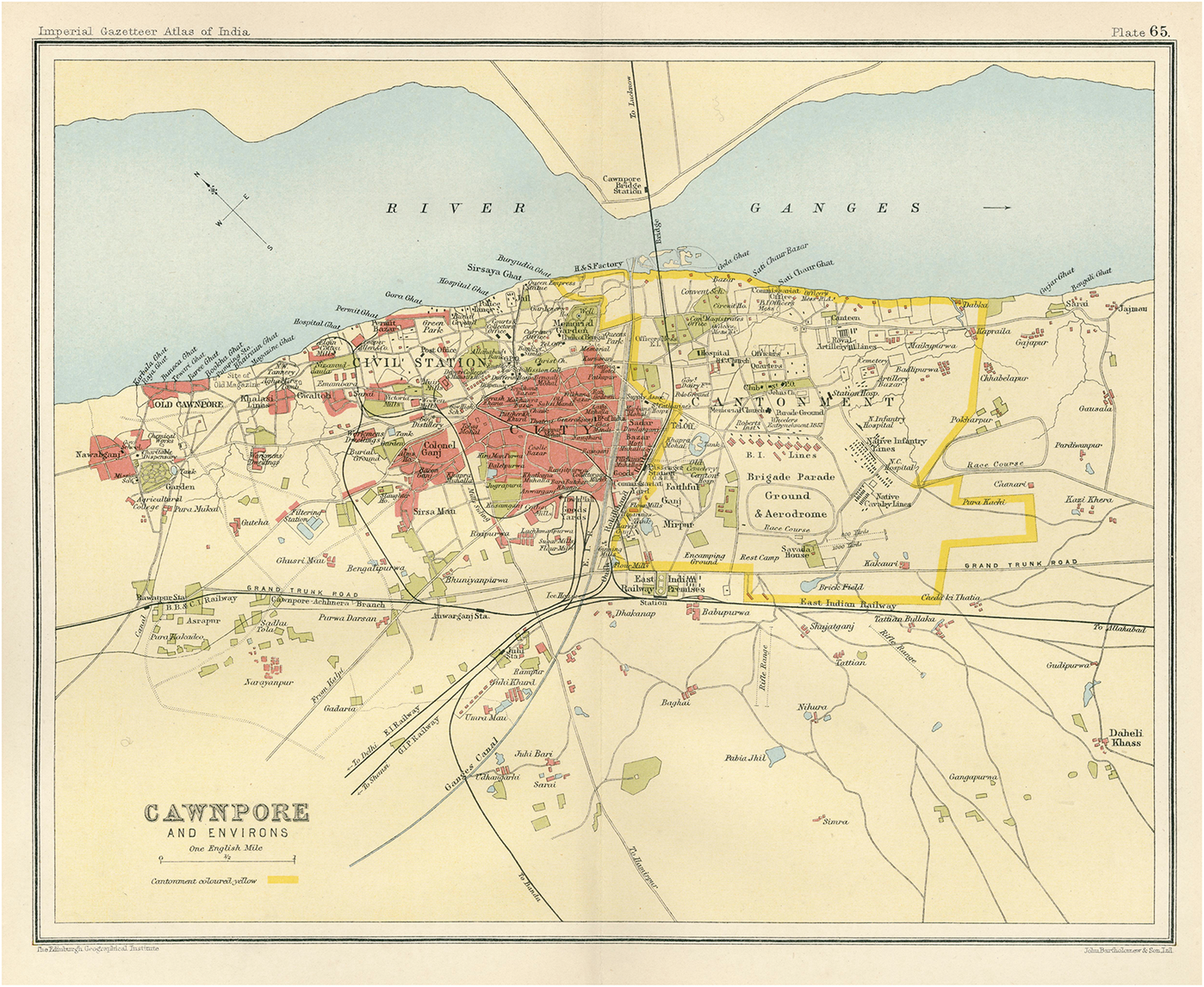

Many areas in Kanpur were named after these indigenous banking and trading families. The setting up of businesses by these elites resulted in the development of new settlements in the city. Neighbourhoods of Kanpur, such as Nawabganj and Etawah Bazar, for example, were named after the Nawab Mutumad-ud Daulah who was ex-minister of Awadh (Oudh), in the case of the former, while the latter was named after the wealthy merchants of Etawah in the United Provinces who had migrated to Kanpur. A map of the city published in The Imperial Gazetteer of India, Atlas (1931),Footnote 16 reveals that it developed as demarcated zones marked by imperial and native areas.Footnote 17 Garrisons, cantonment, administrative offices and European residences characterized the imperial zone. Native areas were divided into bazaars and settlements. Due to their trading significance, bazaars served as a buffer zone of transactional activity where Europeans and natives intermingled for business. Bastis emerged in the vicinity of railway godowns and production and industrial centres, that is, mills, factories and artisanal workshops, at a safe distance from the imperial zone. As Kanpur developed, the official language distinguished between ‘Civil Station’ and ‘City proper’. The former was fitted with sanitation infrastructure and commanded respectability, while the latter constituted crowded brick-built settlements and narrow lanes and carried pejorative connotations as an indigenous environment (Figure 1).Footnote 18

Figure 1. Cawnpore and environs, The Imperial Gazetteer of India, Atlas, vol. XXVI, published under the authority of The Government of India (Oxford, 1931), Plate 65.

To understand the constitution of the basti as a space in urban conflicts, such as the worker protests in Kanpur, a quick review of peasant politics in the countryside of the United Provinces is necessary. Most workers in Kanpur migrated from the rest of the Awadh and the nearby Bundelkhand region of the United Provinces. Scholars have noted the militant nature of peasant mobilization in these regions in the context of exploitative land relations and the subsequent emergence of Kisan Sabha in 1918. Kisan Sabha was a radical peasant organization that mobilized peasants against exploitative land relations and the colonial and feudal nexus in the countryside.Footnote 19 As a result, it was revolutionary in character and did not shy away from acts of violence and sabotage. By June 1919, Kisan Sabha had rapidly grown to almost 450 branches across the province and presented itself as a formidable political force in the villages. In contrast, the Congress Party was diametrically opposed to such political posturing and relied on positioning itself as the flagbearer of Gandhian politics of non-violence as a principle. Peasant distress in the countryside forced workers to move to cities in search of regular or casual work. The city served as a space of survival and an escape route from the exploitative land relations in the countryside. Most importantly, this migrant labour was exposed to the radical politics of Kisan Sabha.Footnote 20 The peasants had experienced political mobilization in their villages for cultivation rights against the landowners and against the unfair taxation practices of the colonial state.Footnote 21 The arrival of migrant labour in Kanpur and its haphazard settlement in the city populated it with radical political subjects who had great expectations but were conscious of the colonial state’s extractive tendencies due to the campaigns of Kisan Sabha.

The growth in trade and the subsequent requirements for an ever-ready workforce led to peasant migration to Kanpur from these hinterlands of the United Provinces, especially from the region of Awadh and Bundelkhand. Gawaltola and Khalsitola (the latter also known as Khalasi Lines) emerged as distinct, working-class areas comprising various bastis catering to the workforce needs of the trading and industrial centre of Kanpur. While individual bastis were more-or-less ethnically, socially or religiously homogeneous settlements, a group of bastis was referred to as a tola. Neighbourhood, therefore, had two connotations: first, tolas as larger working-class neighbourhoods within the broader urban territory of Kanpur and second, caste or ethnicity-based smaller settlements called bastis within the tolas. While Gawaltola and Khalasitola represented class identity in the city, bastis represented caste or ethnicity-based segregation inside the tolas. Gawaltola and Khalasitola were next to each other and developed in proximity to various leather factories, tanneries and cotton mills. Most of the industrial landscape of Kanpur was developed on the riverfront of the Ganges, where European bungalows had existed before the mutiny of 1857. Chitra Joshi, in her informative work revisiting workers’ militant mobilization in Kanpur, has recorded that Gawaltola was understood as a fortress of workers where various strikes began.Footnote 22 The Kanpur Mazdur Sabha office, the first trade union in Kanpur, was established in these working-class neighbourhoods.

Khalasitola and Gawaltola were dense, bustling areas in the 1930s. Scholars have noted that the 1930s witnessed drastic political change and urbanization, the rapid development of industry and challenges to the social lives of Indian workers.Footnote 23 The focus of colonial urban planning was geared more towards the imperial and business areas, while the rest of the city remained outside any active improvement efforts. Kanpur was a garrison area; therefore, the military zone was developed from the point of view of presence, power and control. It was situated next to some cotton, sugar and flour mills and was also nearer to the business area where banks and bazaars were located. The working-class bastis, on the other hand, were away from the bazaars and the cantonment. Due to the scarcity of resources and space, the workers constantly arriving from the countryside were accommodated in bastis across Gwaltola or Khalasitola. Urban proximity thus resulted in solidarity for a common cause. However, it did not diminish caste and religious differences. Bastis were formed on the basis of caste and religious identities that were perpetuated from source villages. Kanpur’s cityscape sustained two models of segregation and control. One was colonial in nature, where the separation between imperial and native zones occurred based on race and imperial governance, and the second was based on the native social hierarchy, which subdivided settlements based on caste.

Bastis reinforced community allegiances as a wider array of peasants made their way to the city.Footnote 24 Chitra Joshi has noted that the unskilled labour in Kanpur was drawn primarily from the Unnao district to its north across the Ganges in Awadh.Footnote 25 Gawaltola and Khalasitola were inhabited predominantly by migrants, mostly comprising artisans and retainers. Both neighbourhoods developed nearer to mills and leather works located next to the riverfront. As the city and its industry grew, other working-class labourers also crowded into this space. The continuation of rural social structures in the city allows us to see these nuances of urbanization.Footnote 26 More recent scholarship on Khatik bastis in the Colonel Ganj and Latouche Road area of Kanpur has argued that Dalit bastis were sites of silent protests that deployed multifarious subversive strategies to negotiate the everyday challenges of caste relations in the city.Footnote 27 Khatiks (traditionally considered butchers) were allocated lands by the colonial government, often in wastelands around railway stations and army cantonments, in the vicinity of railway stores, leather tanneries and bristle factories.Footnote 28 They were also used as construction labourers by the colonial state. Notably, Colonel Ganj and Latouche Road were in between Gwaltola and the Khalasitola and the Kanpur railway yard. Leatherworkers, scavengers and porters from lower castes were initially tolerated in the areas near the cantonment and continued living there even after the area came under civil control with the development of the mills. Workers from the Chamar community, associated with leather work, were dominant in tanneries and leather factories. They constituted almost 65 per cent of the workforce related to leather work. However, Chamars were also working in the cotton mills in large numbers by the 1930s and 1940s. In contrast, artisans and weavers also constituted a substantial percentage of workers in the city by the early twentieth century. For example, in 1906, Hindus of the Kori caste (traditional weavers) and Muslim Julahas (traditional handloom weavers) respectively constituted 21 per cent and 30 per cent of the workforce in Kanpur factories.

Working-class bastis became representative of urban precarity and marginalization. They became places of survival in the city rather than dignified dwellings. Wealthier inhabitants of the neighbourhoods gained prestige through the control of worker housing. Enclosed compounds of 10 to 12 tenements across the bastis became part of the evolving cityscape. Over time, these tenements were increasingly congested with the continuous arrival of migrants. A growing army of labourers awaiting permanent employment also squatted in these areas or joined their relatives who had permanent work at various factories. Tenants constructed mud huts with bamboo and tile roofs. The bastis became vastly overcrowded and devoid of sanitary and drainage facilities.

Urban precarity and permanent inequality in the colonial city

The changing demography of the city and resultant occupational relations had a significant impact on urban politics. Industrial work dynamics required a large workforce to be available on standby. However, the impermanence of work led to the emergence of an army of casual labour in the city. It set up a dynamic of precarity between industry and workers. Unlike permanent employees, the casual worker also had inadequate workplace patronage relations, that is, no mentorship or sustained membership within a workplace. The lack of a permanent and dignified place to stay, accompanied by efforts to tighten social control over the workforce, greatly aggravated worker politics. Scholars have noted that social control over workers’ lives included policies aimed at disciplining their living and working habits and habitat.Footnote 29 This was soon extended to ‘regulate their cultural expressions, public conduct and political behaviour’.Footnote 30 ‘Overt forms of discipline and social subordination’ accompanied the existing material deprivation of the urban poor.Footnote 31

These power dynamics and inequalities in Kanpur worsened in the 1930s. Workers felt an increasing sense of alienation from the city as well as from their workplaces. The Mazdur Sabha trade union campaigned in Gawaltola and Khalasitola over worker marginalization and discontent. As a result, workers across the bastis in these areas joined the cause of collective well-being, thus turning the basti into a site of militant solidarity. Militant mobilization by the Mazdur Sabha put the nationalist Congress Party directly in the line of fire of both labour and employers and changed the political dynamics in Kanpur. The colonial form of worker social subordination and discipline in Kanpur continued even when Congress formed a provincial government in the United Provinces after the high-voltage elections of 1937. These elections were conducted in the wake of the recently passed Government of India Act 1935, granting an opportunity for provincial representative politics to Indians. According to the 1935 Act, India was now administratively divided into a centre and provinces. However, the viceroy retained residual powers at the centre. Governors became heads of the provincial executive and retained special reserve powers despite the core provision of elected representatives and a Council of Ministers.

Peasant distress had caused Kisan Sabha to emerge as a militant organization across villages in the province. In response, the socialists within the Congress Party, which shared ideological similarities with Kisan Sabha, tilted towards peasant mobilization in the countryside. Their reach among the masses in the city and the countryside made them dominant in the provincial Congress organization.Footnote 32 While the socialists within the Congress organized workers at all levels, the socially conservative section of the party dominated the new United Province government and, like the colonial state, soon began to see worker strikes and protests as threatening disorder. Worker militancy in the form of industrial strikes challenged the governance policy of the Congress government. Congress resorted to banning protests and the use of public space in the city. Congress had campaigned on safeguarding the people’s freedoms against the repressive colonial legal system. Yet when presented with the opportunity to govern, its approach to public order in the city was reflected in its continuation of the use of section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) to control and prohibit strikes. This raises questions about the relationship between public order as a political paradigm and the response of anti-colonial political parties to similar challenges when in power.

The Kanpur labour strikes were the product of the difficulty of governing industrial towns where migrant workers became the majority of urban poor. As a result, the precarity of the labouring classes and their militant mobilization were both simultaneous and inevitable. The Kanpur agitation began when the Allen Cooper factory workers in Kanpur went on strike in November 1936. The Allen Cooper Company initially traded in raw cotton and later manufactured leather goods. The main reason for the strike was the cut in workers’ salaries and their demand that the Mazdur Sabha be recognized as the union for factory labour across Kanpur. Recognition of the Mazdur Sabha as a pan-Kanpur organization converged around the common representation of workers. This highlights two issues: first, issues of economic survival, and second, worker claims to power and the politics of representation in the city, as this article will reveal. Despite 15 representatives of workers having held a two-hour meeting with M.L. Carnegie, the managing director of the Allen Cooper factory, more than 3,000 workers did not show up for work on 5 December 1936.

Due to poverty and desperation, workers had little patience, nor did they fully trust the assurances of the mill management. Reports in the archives reveal that according to the agreement made during the meeting with the managing director of the factory, workers were to return to work at eight in the morning. When they did not appear, the management issued a notice halting further negotiations unless the workers resumed factory work. It hired 150 casual labourers to replace the striking workers and put up a poster at the factory gates contesting worker claims of a wage cut and refused to dismiss the replacement workers.Footnote 33 The striking workers formed picket lines at factory gates to prevent temporary labourers from entering through the gates. During the strikes, the parade ground near Gwaltola and Khalasitola served as the main venue for worker meetings.Footnote 34 The situation did not improve even after a few days. On 8 December, the local administration noticed the increasing momentum of worker mobilization and imposed section 144 CrPC around the premises of the factory, which prohibited the workers from assembling outside factory gates and their movement in the mill areas. Working-class inhabitants of the city faced internal complexities in social relations in their neighbourhoods. Migration to the city was not free from the burden of caste. The reality of caste was an essential feature of social space in India, whether colonial or otherwise. Inhabitants of bastis alternated between co-operation and competition or could assume the role of collaborators or opponents, depending on the local dynamic at a given point in time. The hiring of 150 workers, who were perceived by workers as strike-breakers, was one of the main points of contention. It was seen as victimization and penalization of striking workers.Footnote 35

The Congress Party began to face the heat of the walkouts. In light of the upcoming provincial elections, factional disagreements about labour strikes emerged within Congress ranks. For example, with B.P. Srivastava as the chairman, the Kanpur Municipal Board passed a resolution expressing sympathy for the workers’ cause. It appealed to the board to sanction 10,000 rupees for their immediate relief.Footnote 36 By this time, the workers had been out of work for three weeks. A committee led by Srivastava was also appointed to mediate a settlement between the workers and factory management.Footnote 37 Meanwhile, the factory’s legal advisor, Rai Bahadur Vikramjit, sent a legal notice to the striking workers asking them to vacate the quarters in the Allenganj settlement area. This worsened the conflict. The legal notice intended to exploit workers’ vulnerability and threatened to take away their residence in the city. As part of broader tactics by factory management, it aimed to threaten and discipline the working classes for adopting militant agitation.

When several formal efforts failed to convince workers to call off the strike, management took another approach. The European employees, who were the managerial and technical staff of the factory, visited the Allenganj settlement area to persuade people to return to their duties. However, they did so under a police escort. They were mostly British and stayed in the European quarters of the city which were conveniently placed near the bazaars as well as the cantonment area. Such efforts of outreach and pacification by the European employees did not yield the desired results. Meanwhile, factory management eventually dropped the replacement workers due to their lack of skills. Clearly, management felt threatened at the prospect of economic loss due to the strikes and militant posture of labour. The municipal administration was also threatened by the scale of mobilization and organization across the working-class bastis. During meetings, labour representatives categorically expressed their displeasure at repeated police intervention in factory matters.Footnote 38 The city administration also invoked public order laws, thus restricting the political mobilization of workers and their access to space inside and outside the factory. The Kanpur district magistrate extended the prohibition orders under section 144 CrPC to the entire city for the next two months.

Working-class bastis emerged as interactive networks providing political meaning to life in Kanpur. They became significant spaces of political deliberation and strikes, and expressions of political action. Newspapers reporting on the protests particularly noted the display of red flags and slogans advocating revolution, which disturbed trade and spread terror among peaceful citizens.Footnote 39 The entirety of the confrontations was meticulously reported by The Leader, given that the ongoing provincial elections occurred simultaneously with the protests across the city. Workers saw the arrival of provincial elections as a significant opportunity to amplify their grievances and imbue the election campaigns with their own cause.

We can observe the emergence of a grassroots, issue-based organization of the urban poor around the demand for recognition of the Mazdur Sabha trade union. Due to the shared experience of alienation, segregation, precarity and marginality, there were frequent occasions for class solidarity beyond religious or caste-based divisions. The political discourse transcended social and spatial boundaries.Footnote 40 Worker mobilization was often geared towards the dignity of labouring lives. Strikes in Kanpur emerged as a distinctive urban collective culture and, in many ways, reflected a civic affirmation of urban life. To claim their rightful access to urban space, protest marches, therefore, were defiant acts against the prohibitory orders of the city administration. For example, strike leaders were arrested for violating section 144 CrPC when a huge procession moved through major streets in Kanpur to protest the workers’ plight. Hindu and Muslim shopkeepers in the city also observed a shutdown on 20 December 1936 to express sympathy with the workers’ cause. The entirety of Gawaltola, Khalasitola as well as various other worker settlements mobilized to make their voices heard. City-wide protests demanded a claim to urban space along with having their difficulties heard.

Despite the vocal election campaigns, worker issues remained distant from the Congress Party’s platforms and revealed its lack of understanding of working-class poverty and marginality in Kanpur. However, the force of this urban collective movement pressured the Congress Party to seek their approval. Congress leaders began to appear at some of the protest meetings.Footnote 41 Across mills and factories in Kanpur, workers complained about their exploitation at the hands of low-level supervisors who worked in favour of the management rather than the workers.Footnote 42 Workers were disappointed with the management’s lackadaisical attitude towards their legitimate demands. As a result, mills across Kanpur joined the strike that had initially only concerned the Allen Cooper factory. Meanwhile, the provincial elections of February 1937 concluded, solidifying the Congress Party as a major political force in the United Provinces. G.B. Pant became the premier of the provincial government.

Workers realized that their precarious circumstances evaded any political traction in the nationalist discourse, and they were conveniently overlooked as potent stakeholders to claims of power in the city. They collectively intensified their demand for the recognition of the Mazdur Sabha as the workers’ main representative union across mills and factories in Kanpur. Their stress on a pan-Kanpur worker organization was not merely a case of negotiating workplace relations. It was also a vigorous effort to organize their social and political life both inside and outside the factory. By the end of July 1937, representatives of the Mazdur Sabha extended their assistance to mediate the conflict between the workers and the factory management. When the mill management declined their offer, two Mazdur Sabha representatives, Harihar Nath Shastri (Congress) and Sant Singh Yusuf (Communist), met the district magistrate and requested a meeting between the Mazdur Sabha and the mill management. Shastri had recently been nominated to the United Province Legislative Council by the Congress Party. At a meeting to congratulate Shastri on his nomination, workers exhorted him to appeal to the Congress government to withdraw section 144 CrPC orders and enable them to organize for their legitimate cause.Footnote 43

The labour militancy that emerged out of the bastis of Kanpur posed new challenges for the newly elected Congress Party. It had campaigned on an anti-colonial platform but soon was faced with a more complicated political reality. It gained control of governance but did not command wholesale authority nor ideological hegemony over matters of subaltern politics.Footnote 44 Workers refused to agree to a peaceful and co-operative relationship with the city administration and their employers unless their demands were considered. As a result, the newly elected provincial government continued with the colonial administrative response to invoke extraordinary laws when dealing with political unrest. Among diverse forms of anti-colonial agitation, labour militancy further consolidated the image of the urban poor as ‘lawless, disorderly, violent and criminal’ and ‘provided justification for their control and discipline through policing’.Footnote 45

Strikes and public order: the urban poor’s claims to power in the city

The colonial government had the tendency to see worker agitation as a local conflict that did not reflect the wider national picture. In response to the expanding politics of the Kanpur strike, the colonial government published a report highlighting the improvement of working circumstances over the years, if the broader picture was considered. However, it conveniently ignored the reasons for working-class marginalization in the city. With a myopic focus on raw material supplies, production and economic output, loss of working days, etc., the colonial government abnegated its responsibility towards resolving the precarious nature of urban life and affirming mechanisms of meaningful political representation.Footnote 46

The administration’s obsession with public order limited its understanding of such conflicts and contestations. The ability to reduce or control strikes and their economic impact was seen as an administrative success by the government. For example, in 1937, the colonial government published a report titled ‘Industrial disputes in India, 1926–36’ in which it observed the recent labour situation in industrial cities and suggested a drop in the loss of working days due to strikes. A newspaper editorial in The Leader noted that the improvement may have been attributable to the appointment of the Royal Commission of Labour in India.Footnote 47 It further observed that the commission had significant influence over the moderate labour leaders open to co-operation and, thus, had succeeded in convincing them of the futility of strikes and the positive impact of co-operation and peace between management and workers. It stressed that management’s meaningful engagement with workers’ legitimate grievances would weaken extremist leaders’ hold. It further highlighted that labour leaders had to understand that frequent strikes would worsen the workers’ plight. Sounding almost like government propaganda favouring industry, The Leader editorial advised the workers to choose their leaders carefully and save themselves misery and suffering. It further expressed hope for management’s positive response so that ‘extremist leaders’ would not gain further influence.Footnote 48 The workers in Kanpur paid little heed to this line of argument and continued with their strikes.

Workers had an acute awareness of law, space and politics in the city. Despite Harihar Nath Shastri’s nomination to the United Province Legislative Council and the possibility of a favourable solution by appeal to the premier, the workers went ahead and formed a 60-member committee to co-ordinate and organize a strike across factories in Kanpur. The committee drew its members from bastis across Gawaltola and Khalasitola. They demanded the removal of section 144 CrPC-related restrictions and requested the premier to open an enquiry to investigate the issue of wage cuts.Footnote 49 The labour unrest kept growing, with more factories joining the strike. Sant Singh Yusuf, a prominent leader of the strike, was arrested on the evening of 3 August 1937. The city administration drafted more police to deal with any violence that arose from his arrest. Congress sensed the increasing influence of communists over the workers in Kanpur and appointed the United Province minister for industries, K.N. Katju, to mediate between mill owners and workers.

Given the spread of unrest across the factories and bastis, these strikes became the dominant discourse in Kanpur’s cityscape. A cursory look at newspaper reports reveals that labour protests, sloganeering, picketing, meetings and marches became a common sight in Kanpur. Nationalist political conversations and civic life were deeply affected by the reporting and discussion around labour anguish and despair. Threatened by growing popular perceptions tilting towards the workers, the mill owners also formed an association called the ‘Northern Mill-Owners Association’ to safeguard their interests.Footnote 50 It aimed to demonstrate the unity of mill owners and to highlight their collective frustration with the losses the industry incurred due to frequent strikes. Unable to resolve the conflict, the city administration resorted to its prohibition tactics and issued fresh orders under section 144 CrPC to scuttle any effort by the Mazdur Sabha to call for large-scale protests in the form of a general strike.Footnote 51 In opposition to the bourgeois perception of public order, civic life in Kanpur was enriched by counterclaims by workers. Any belief that saw factory work as separate from workers’ life circumstances was severely undermined by the strikers. The workers challenged the prejudice, discrimination and oppression that underlay these bourgeois perceptions. When K.N. Katju arrived in the city on 5 August 1937, the workers conveyed to him their demands including recognition of the Mazdur Sabha, an investigative committee to look into wage cuts and assurance that workers would not be victimized for trade union activities. Across newspaper reports, it clearly emerged that the Mazdur Sabha was the political lifeline of working-class neighbourhoods in Kanpur. It provided political vision, direction and organizing strength for the working-class inhabitants of the city.

The mill management representatives, such as Sir Tracy Gavin Jones, Lala Padmapat Singhania, H.A. Wilkinson, C.W. Tosh, R. Menzies and T.I. Smith, also met the minister and expressed their inability to recognize the Mazdur Sabha. For them, it was neither sufficiently representative nor influential enough to impose its decision on workers. The Congress minister failed to resolve the dispute and returned to Lucknow. He could neither influence the workers nor the factory owners, and his visit ended in political embarrassment. Local Congress leaders such as Balakrishna Sharma deplored the mill owners’ refusal to recognize the Mazdur Sabha and anticipated a first-class labour crisis in Kanpur.Footnote 52 Workers had now begun criticizing the Congress provincial government and held it equally responsible as the mill owners. For them, if the government wished, it could recall prohibitory orders and immediately release arrested leaders. At workers’ meetings against the imposition of section 144 CrPC restrictions, resolutions were also passed against the arrest of Sant Singh Yusuf.Footnote 53

As the scope of the strike expanded, more workers from other factories joined the strike. Strikes, protest marches and picketing became important acts of resistance for the urban poor. Despite Kanpur administration’s prohibitory orders, workers protested on the streets and around mill areas. Such defiance was aimed at claiming urban space and marking it with a labour presence that was otherwise rendered invisible in the city. Strikes became a theatre of political resistance where raucous battles were fought on the streets against processes, institutions and perceptions that ignored worker marginalization, both inside and outside the factory. For example, on 6 August 1937, almost 20,000 workers from seven mills across Kanpur joined the strike. The sheer number of strikers reported in the newspapers highlighted worker solidarity in the city. It also draws our attention to marginal and crowded yet politically charged spaces like Gawaltola, Khalasitola and other working-class settlements in Kanpur. Out of frustration, swelling numbers of protesting workers now resorted to damaging industrial property and confronting police, resulting in baton charges and even police fire.Footnote 54 Many of the workers were arrested. In such a highly charged atmosphere, the basti reveals itself as a space of urban segregation that manifested practices of discrimination against the poor and the formation of stereotypes. However, the basti neighbourhood also became a space for mobilization and solidarity. This solidarity was not sentimental nor in vain but instilled an ability to argue for workers’ social and political rights and stake a claim to public space in the form of collective protests and riots.Footnote 55

Congress as a government made continuous efforts to seek support from the urban bourgeoisie while engaging with the workers’ cause. G.B. Pant sent Acharya Narendra Deo, the president of the United Province Provincial Congress Committee, to intervene and find possible solutions to the conflict.Footnote 56 Local Congress leaders met the Mill-Owners’ Association while proposals forwarded by the Mazdur Sabha were discussed. The mill owners passed a resolution expressing willingness to recognize the Mazdur Sabha, if workers across Kanpur would resume work on 9 August.Footnote 57 It added that the recognition of the Mazdur Sabha was contingent upon the assurance that no further strikes would take place in future without providing reasonable notice. A statement by the Congress minister for industries, Katju, reveals that Congress was stuck trying to secure a balance between worker and mill owner support. While recognizing the challenges facing workers, he criticized them for the strike and simultaneously recognized mill owners’ efforts for their contribution to the growth of industry in the province. He went as far as asserting that mill owners were ‘generous and sensible’ and not tyrannical.Footnote 58

The urban precarity of the workers was exacerbated during strikes due to the apathetic attitude of factory management and the city administration. Yet their movement created possibilities of resistance, an active contestation against the homogenizing tendencies of urban governance that stressed more efficiency and discipline and less welfare. Due to the campaigns of the Mazdur Sabha, bastis became spaces where workers organized outside the factory to pursue and achieve demands and negotiate control over work and residence. When the strikes showed no signs of abatement, the provincial government instituted an enquiry committee to investigate industrial relations and workers’ conditions in the city. It appealed to workers to facilitate the effort; however, it asserted the government’s right to maintain ‘peace and tranquillity’ and suggested that the district magistrate and the police were expected to act with impartiality while exercising restraint.Footnote 59 The Congress government indirectly justified the banning of city spaces for workers’ mobilization and affirmed its monopoly over the use of legitimate physical violence.

The context of the urban offered workers a distinct opportunity to magnify political confrontation, sharpen claims and embarrass political parties, local administration and the provincial government.Footnote 60 The provincial government’s repressive response to the workers’ protests drew immense criticism from the Congress Socialist Party.Footnote 61 It passed resolutions criticizing incidents of police lathi charges and firing on crowds, the use of prohibitory laws such as section 144 CrPC and denounced the imprisonment of their leaders. These resolutions passed at various meetings at Patna, Allahabad and Benares recounted Congress pledges on workers’ rights, a living wage, freedom of speech and association and the right to strike.Footnote 62 The city became a theatre of multifarious contestations where specific sites and institutions began to draw broader political attention. The strike broadened the scope of politics far beyond the territoriality of the city. As a result, the process of space-making and claim-making occurred simultaneously. The Leader consistently reported on all meetings, statements and resolutions related to the protests and strikes. Serving an important role, the paper gave space to all factions of the Congress Party. It acted as a mediator shaping the political morality of the city.Footnote 63 It appears that The Leader was sympathetic to the workers’ cause but cautious of its communist tendencies.

The urban poor rejected the makeshift redress of the reality shaped by their precarious living and working conditions. Even G.B. Pant’s efforts to intervene and bring about a settlement to the conflict proved unsustainable. The hasty settlement did not last long.Footnote 64 The continuation of strikes challenged the perceived notions of the urban that represented modernity, economic prosperity, discipline and entrepreneurship.Footnote 65 Ironically, nationalist leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi saw merit in police action against the protestors in Kanpur.Footnote 66 Initially, these leaders had vociferously protested against the colonial government’s prohibition orders and repressive measures. Now that Congress was at the helm of the provincial government, such measures became acceptable and gained rapid traction in its approach to managing protests. In addition to being an urban governance crisis for the administration, the immense economic pressure due to strikes brought industrial activity in Kanpur to a screeching halt. The urban poor’s protests began to be seen as ‘criminal’ and lawless.Footnote 67 Hence, such protests led to the extension of prohibitory and repressive orders.Footnote 68 In most of the newspaper reports, the protesting workers were described as violent, aggressive, defiant, unruly and threatening, and the police were reported always to have acted in self-defence.Footnote 69

When the findings of the enquiry committee were published, the report confirmed that worker class precarity across industry in Kanpur was true. It revealed the unco-operative behaviour of the mill owners in the investigation and exposed their hostility towards the protesting workers. It highlighted the difference between wages in Kanpur and those in the rest of India’s industrial centres and further revealed that the profits made by the mill owners and the wages of the workers did not correspond proportionally.Footnote 70 The mill owners rejected these findings, and the contestation continued without resolution, only to be distracted by the onset of World War II. Strikes became an ongoing crisis of public order and a new urban modality in Kanpur. Kanpur strikes in the 1930s offer significant insight into the challenges faced by the city’s urban poor. Against the normalization of a bourgeois colonial urbanity that expected one-sided discipline and responsibility, workers mobilized to articulate their legitimate rights and staked a claim to a dignified life in the city.

Conclusion

The Kanpur strikes of 1936–37 reveal the political dynamic activated by urban proximity. First, the peasant from the countryside who was entangled in feudal land relations in the village came face to face with the exploitative authority of the urban bourgeoisie. Hence, urban proximity triggered class consciousness and, therefore, class mobilization. Second, class politics and nationalist politics in the colonial context did not necessarily have the same goals. The contestation between the communists and the Congress Party is one such example. Third, urban proximity revealed the maintenance of public order as a political paradigm of governance, thus creating an intimate environment between the colonial subject, circuits of capital and the colonial state. The Congress Party, despite being the main nationalist organization, did not tolerate political others, much like the colonial state before the Government of India Act 1935. This dimension was singularly highlighted in the context of the urban due to the scale of mobilization and the political traction and challenges it generated. When Congress gained control of the provincial government, it saw itself as the only legitimate source of governing authority. It weakened its moral claim to politics and, as a result, derived legitimacy from repressive colonial measures.

The demands of the workers show that urban collective action was motivated by precarity that originated in working-class neighbourhoods in the city. Such precarity sometimes activated communal consciousness and, other times, class consciousness. Due to the concentration of workers networked via community and village in these neighbourhoods, their collective action was infused with rigour. Even so, the factions within the working-class movement were not homogeneous. Workers’ demands around wages, housing and social and political life converged around the city and its working-class basti neighbourhoods. Through collective action, workers claimed the city and derived a sense of belonging. Therefore, these neighbourhoods were not self-contained spaces but interactive networks infusing political meaning to life in the city.

Manifold spatial relations in the service of capital in a city like Kanpur were seen as expressions of colonial urbanity. Bastis disturbed this stable understanding and appeared as a dark underbelly of urbanity where destitution, exclusion and despair blunted the prosperity and entrepreneurship that exemplified the glory of the colonial enterprise. Workers’ collective action amplified the grammar of difference that colonial urbanity created. Issues of disjunction and connection in neighbourhoods, both geographic and ideological, become apparent in the Kanpur strikes. The city emerged as a site of fragmentation and alienation – a space which accelerated a crisis of legitimacy of capital, colonialism and the homogenizing tendencies of the nationalist discourse.

Competing interests

The author declares that there are no potential competing interests with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.