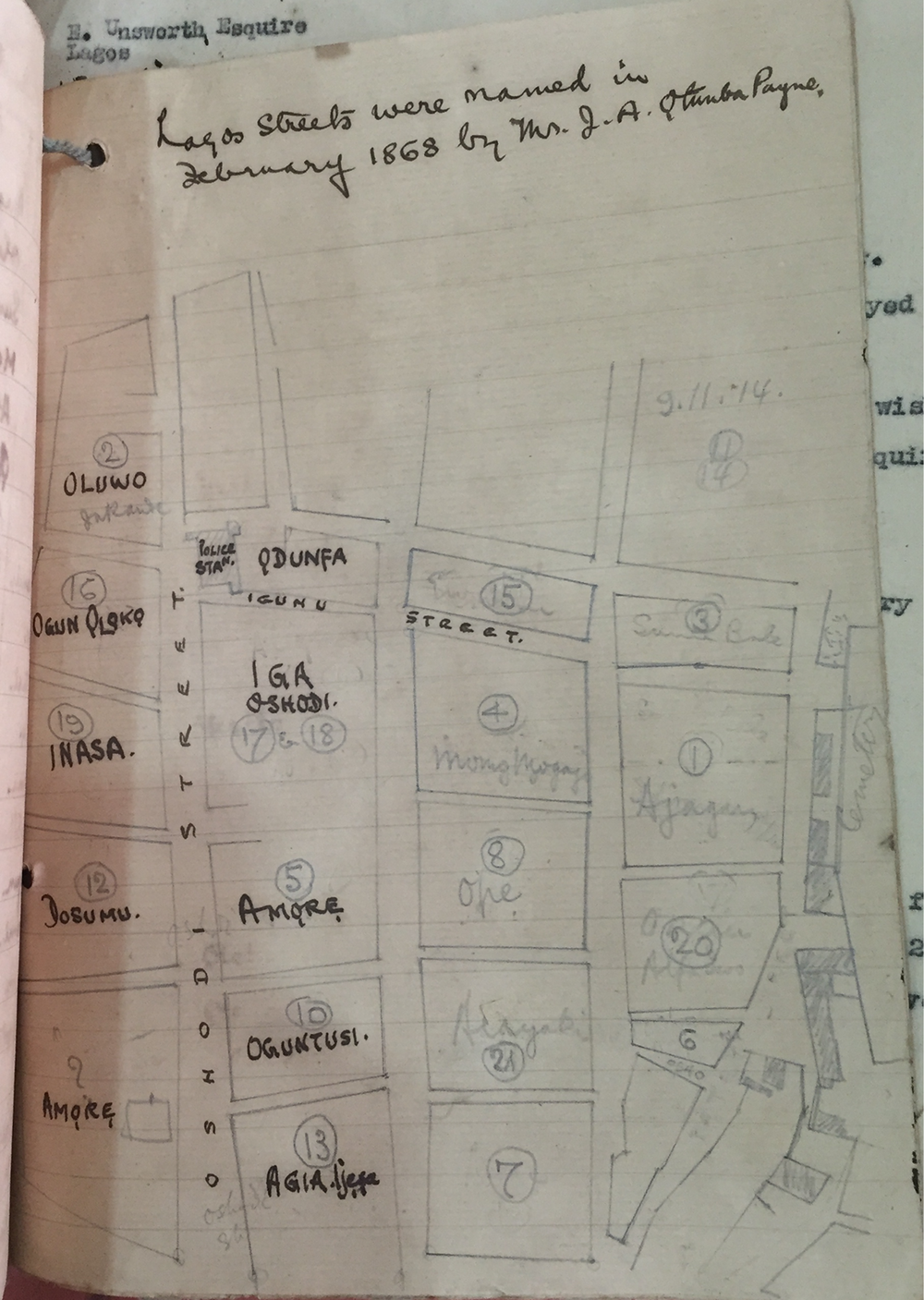

Beginning in the 1920s, the Lagos neighbourhood of Epetedo (Figure 1) – which translates to ‘the place where the Epe people settled’ – witnessed a wave of struggles, claim-making and activism around landownership. Descendants of the first settlers, who arrived in 1862, debated with each other over whose ancestors owned or could sell properties. The neighbourhood became embroiled in a long and contentious battle over landownership, which intensified after the British government acquired 1 of the 21 compounds (Figure 2) that comprised Epetedo. The Epetedo Union represented residents of 18 compounds, each comprising different families with ancestral claims to the first settlers. In contrast, the descendants of Oshodi Tapa, one of the first settlers, stood on the other side of the debate. While members of the Oshodi Family asserted that Tapa owned Epetedo, the Epetedo Union countered that the land was jointly owned by all the original settlers, including Tapa. The conflict spanned from 1927 to 1947, culminating in the British governor enacting land ordinances aimed at resolving this and other property disputes across Lagos. These battles over property rights spilled out of Epetedo into the English and bilingual press, and the British courts and administrative offices, where the disputants described their ancestors’ contributions to Epetedo’s development.

Figure 1. Epetedo. Map by Ademide Adelusi-Adeluyi, May 2020.

Figure 2. Illustration of Epetedo compounds by Herbert Macaulay.

Source: Ogedengbe Macaulay Papers, KDL Library, University of Ibadan Special Collections, Nigeria.

Property disputes intensified across West African towns and cities from the nineteenth century onwards. A confluence of factors – including the imposition of colonial rule, migrants’ growing demand for land and the transition from the slave trade to agricultural commodities’ exports – fuelled competing claims over property rights.Footnote 1 As colonial authorities’ appropriated land and property sales proliferated, indigenous landowners and newcomers alike vied for compensation and control over land distribution.Footnote 2 These struggles often pitted family members, neighbours and traditional rulers against each other in contests for power, belonging and profits from the real estate market.Footnote 3

The Epetedo case tells two stories. The first is about the tensions between colonial administrators and Africans over land tenure and competition among colonized subjects to determine property rights.Footnote 4 The second story is about neighbourhood transformation in colonial cities. Property dispute cases have rarely been used to reconstruct the history of residential areas or to explore the lived experiences of their inhabitants beyond the courtroom.Footnote 5 Yet, in their writings, the Epetedo Union and the Oshodi Family described how and why their ancestors initially acquired the land and built their compounds. They viewed their quarter as unique because its first settlers fought alongside indigenous rulers, fled Lagos after the British bombardment in 1851 and returned in 1862 to build their houses. These narratives were not solely crafted to resolve the question of who owned Epetedo. They also offer insights into how city dwellers perceived and classified the development of their neighbourhood. At the same time, the history recounted during the colonial period remains central to how Epetedo’s past is discussed today.Footnote 6 Urban inhabitants have long used historical narratives to define the configuration of their districts.Footnote 7 But Epetedo is distinct for how its residents leveraged divergent accounts of their past to shape their identity and influence property laws. Epetedo disputants not only differentiated their neighbourhood from others but also placed it at the heart of their conflicts. Their competing narratives were crucial for disseminating the quarter’s history and remain integral to the residents’ self-perception, socio-political relations and spatial engagements.

Residential areas in colonial cities have often been studied based on how they were classified and created by imperial administrators. In 1977, Maynard Swanson published the most cited essay in the Journal of African History, which underscored how colonial administrators segregated residential enclaves to control Africans’ labour and impose European planning schemes. In cities like Dakar, Europeans invoked racist medical ideas and the bubonic plague outbreak to justify separating African residential areas from European ones under the pretext of improving the city’s health.Footnote 8 In British colonies, administrators separated migrants’ quarters from the indigenous settlements to enact indirect rule policy, whereby ‘strangers’ and ‘natives’ would be governed under separate laws.Footnote 9 However, residents resisted these segregationist planning policies by crossing residential boundaries, settling in European districts and engaging in commercial and social relations across neighbourhoods.Footnote 10 Many also constructed houses and used public spaces in ways that defied official planning laws.Footnote 11 The historical accounts of Epetedo residents offer further evidence of how urban dwellers shaped the identity of their quarters beyond the British colonial administration’s division of urban enclaves by race, ethnicity and indigeneity. While the disputants did not always explicitly denounce colonial policies, they focused on defining Epetedo as a distinct settlement in Lagos. Epetedo’s inhabitants created historical texts to challenge colonial property laws, share their quarter’s history with multiple audiences and assert their belonging to the city. Although Epetedo’s residents developed these narratives to support their political activism, these texts also serve as valuable sources for understanding how urban inhabitants classified and forged identities for their residential areas.

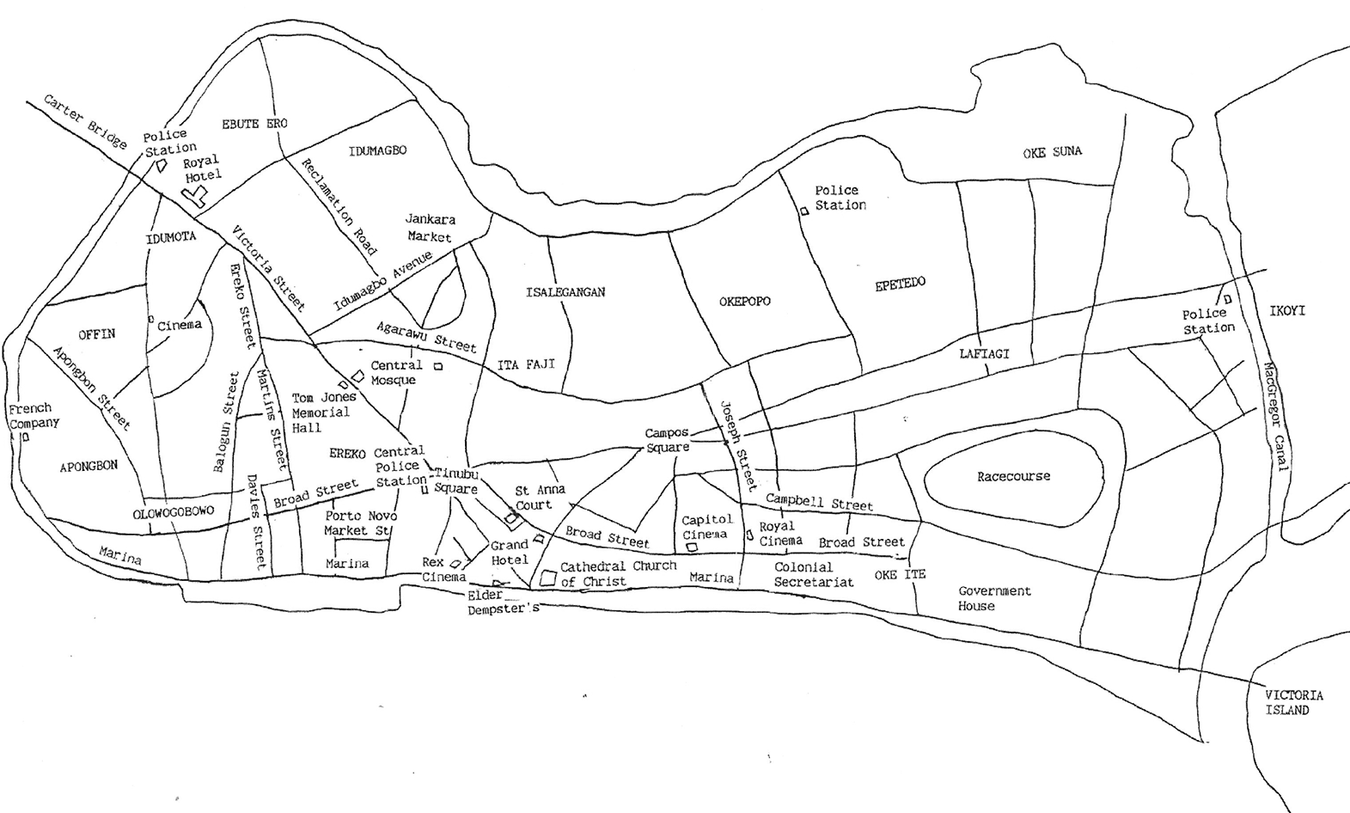

Epetedo disputants did not position their neighbourhood as sharing the same identity as the indigenous and oldest areas such as the Iga Idunganran, the site of the Oba’s palace on Lagos Island’s western area. Moreover, the residents did not consider themselves to occupy a migrant quarter in the same vein as the people in Olowogbowo or the Brazilian quarters, which were established after 1851 by African diasporic settlers. Instead, Epetedo people argued for their district’s unique status, claiming that their ancestors had lived in Lagos before 1851 but fled during the British bombardment of the city. While events such as the 1851 British invasion of Lagos that contributed to Epetedo’s founding also influenced the establishment of other areas, the historical accounts are not mere fabrications. Rather, they reveal how the inhabitants interpreted their past and sought to define their quarter’s identity and shape its future.

This article draws from records including petitions, pamphlets, letters, newspaper articles and court testimonies produced by Epetedo residents during their disputes over land rights between 1927 and 1947. These sources have been preserved at the Nigerian National Archives in Ibadan and the private papers of Black surveyor and political activist Herbert Macaulay at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria. Focusing on the competing accounts of Epetedo’s past by the Epetedo Union and Oshodi Chieftaincy Family, I demonstrate how residents framed their historical narratives to bolster legal claims and articulate their neighbourhood’s history. I argue that these narratives reveal the diverse elements Epetedo residents deemed central to the evolution and identity of their district. In their writings, disputants detailed the actors who built the compounds and houses that comprised Epetedo. These records highlight the residents’ contrasting interpretations of their area’s identity and spatial transformation.

The emergence of property disputes and neighbourhood activism in Epetedo

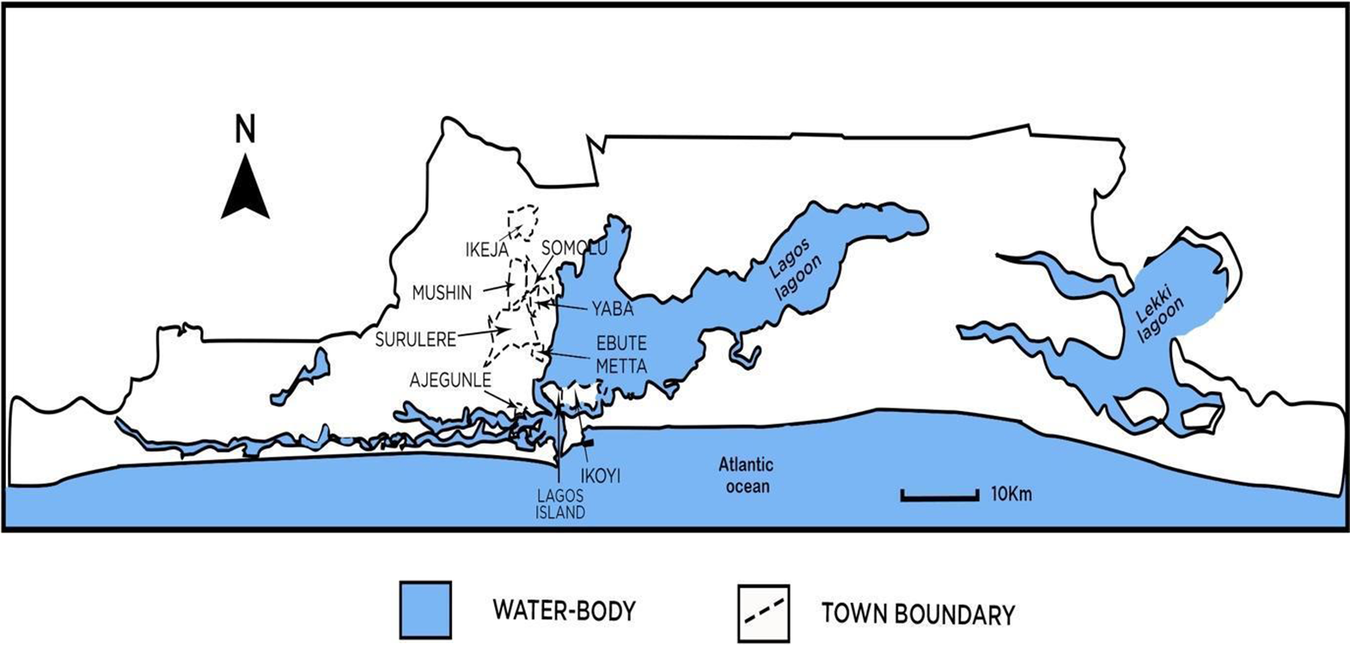

After Epetedo’s establishment in 1862, its residents, like those of many other colonial West African cities, clashed over property rights.Footnote 12 However, the British government’s acquisition of Alfa Iwo’s compound in March 1927 deepened division among Epetedo occupants from the 1920s until the 1940s.Footnote 13 The land seizure coincided with an era when an increasing number of migrants sought housing on Lagos Island.Footnote 14 Moreover, the British government sought to deal with the bubonic plague outbreak of 1924 by acquiring land for a housing estate on Lagos Mainland in Yaba (Figure 3).Footnote 15 By 1928, the Lagos Town Council had demolished the houses in Alfa Iwo’s compound, displacing about 80 people, to build an incinerator (Figure 4).Footnote 16 Instead of the occupants receiving remuneration, they became embroiled in court cases concerning which families owned Alfa Iwo’s compound, and more broadly, the Epetedo compounds that were reduced to 20. The Epetedo Union and the Oshodi Chieftaincy Family emerged as key rivals in these struggles over land rights and the quarter’s history. These disputes underscore the neighbourhood as an important unit of analysis for understanding socio-political relations in colonial cities.

Figure 3. Yaba, Ebute Metta and Ikoyi. Map prepared by Diya Ayobami, May 2020.

Figure 4. Lagos Town Council’s incinerator built on Alfa Iwo’s compound, c. 1956, Epetedo, Lagos Island. Photograph by Alhaji Baba Shettima.

Source: Eko Adele, 1949–1964: The City of Lagos under the Reign of Oba Musendiq Adeniji Adele II (Oba Adeniji Adele Foundation, Lagos, 2014).

The first phase of the conflict in determining the ownership of Epetedo began after Sakariyawo (Saka) Oshodi, Chief Tapa’s son, demanded compensation for Alfa Iwo’s compound. Saka claimed his father owned the land and that the occupants were Tapa’s arota (domestics).Footnote 17 Citing customary land tenure, Saka argued that the arotas held the land in trust for his family but could not sell or claim ownership over it. Saka’s stance reflected a version of customary land tenure, which positioned land as owned communally and allocated by chiefly elites.Footnote 18 As a result of the counter-claims, the British commissioner for lands asked the divisional court to decide who should be compensated. The case, known as Moriamo Dakolo and 15 others vs. Saka Oshodi, lasted from November 1927 to March 1928. Epetedo occupants alongside Lagos chiefs took the stand. British Judge Mervyn Tew ruled in favour of Dakolo and other defendants because Tapa’s descendants had not received rent or tribute on Alfa Iwo’s compound and it was not family-owned.Footnote 19 In 1930, Saka appealed to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London (JCPC), the final court of appeal in the British empire, and won. Saka’s victory was based on ‘reversionary law’, a component of customary land tenure, which stated that unused land reverted to the chief when abandoned by the occupier. The JCPC directed the land commissioner to allocate one fourth of the compensation to the Oshodi Family and three fourths to the defendants.Footnote 20

The JCPC upheld parts of the Full and Divisional Court ruling, affirming that Epetedo land was granted to Oshodi Tapa for himself and his household.Footnote 21 This decision strengthened Tapa’s family control over Epetedo lands and highlighted long-standing tensions between formerly enslaved people and their former masters over property rights. As Kristin Mann notes, the rising monetary value of land in Lagos during the second half of the nineteenth century led slaveholders to adopt strategies to prevent enslaved workers from owning properties. For enslaved individuals or dependants of landowning families, owning land was crucial for achieving freedom and redefining their identities. Some sued their masters in court to reclaim land, while others obtained colonial land documents like Crown Grants on properties bequeathed by their masters to assert private property rights. By the 1890s, the British courts supported the landowning chiefs’ claims that arotas and their descendants could use land to build houses but not sell or mortgage it. Therefore, the JCPC’s ruling on Epetedo reinforced the subordinate status of arotas and their dependence on former slaveholders for land and housing.Footnote 22

Despite the JCPC’s ruling, some Epetedo residents agitated for new land policies. Their historical narratives offer insights into how residents theorized a neighbourhood’s development. In September 1927, E.A. Akintan, editor of Eleti Ofe and a descendant of a first settler, collaborated with others to establish the Epetedo Union.Footnote 23 The group published accounts of Epetedo’s origin, demographic composition and spatial organization. By 1929, the organization claimed 300 members across 18 out of the quarter’s 20 compounds. A 1936 petition signed by 250 people highlighted the group’s diverse membership, including women who were petty traders and men who worked as bricklayers, tailors, Muslim priests, dyers, clerks, photographers and blacksmiths.Footnote 24 While Akintan described the Epetedo Union as created ‘for the mutual benefit of Epetedo people’, its main activity appeared to be challenging the Oshodi Family’s exclusive claim to the land.Footnote 25 Starting from 1929, Akintan served as the general secretary. He authored publications on behalf of the Epetedo Union directed at colonial officials and readers of the bilingual English and Yoruba newspapers. These writings argued that Epetedo belonged ‘equally’ to both their ancestors and Tapa.

In 1936, the Epetedo Union petitioned the British government to abolish customary land tenure. Referring to earlier judicial rulings, the Epetedo Union urged Governor Bernard Bourdillon to establish a commission of inquiry to investigate land titles in Lagos and ultimately abrogate customary land tenure due to its inconsistency with English law, which supported land sales.Footnote 26 Afterwards, the Epetedo Union exchanged letters, published pamphlets and held meetings with British administrative staff to push for government intervention in the ongoing land disputes.Footnote 27

The Oshodi Family actively defended its claim to Epetedo land. Like the Epetedo Union, the Oshodi had a representative who served as chief and head of the family. The Family Council created an executive committee that organized social events and managed the properties in Epetedo.Footnote 28 In 1939, the executive committee submitted a memorandum to the British government’s land commission detailing Epetedo’s history. This document urged the government to uphold British court rulings affirming Tapa’s ownership of Epetedo and to invalidate the Crown Grants that occupants of 18 compounds used to assert private property rights.Footnote 29

Epetedo people produced historical texts to promote their conflicting interests, but these writings should not be dismissed as mere fabrications. Instead, these accounts illustrate how historical actors presented issues that they deemed important to them.Footnote 30 The disputants can be seen as ‘homespun or homegrown historians’, a term coined by historians of East Africa Derek Peterson and Giacomo Macola to describe men and women in colonial Africa who wrote histories to forge new political communities and unite people with diverse histories. These actors, often with some Western education, undertook their intellectual projects while engaging in other professions like preaching or conducting litigation. Homespun historians often conducted interviews with elders, engaged in archival research and cross-checked their findings – sometimes using the press to amplify their causes.Footnote 31 Similarly, the representatives of the Epetedo Union and the Oshodi Family employed comparable methods by gathering data from oral interviews, newspapers, British administrative files and court records. Epetedo residents popularized their quarter’s history while also challenging misinformation. These texts not only reveal efforts to shape political outcomes but also provide valuable insights into how historical actors constructed knowledge about their quarter’s evolution, its defining events and their own identities.

The making of Epetedo in homespun histories, 1927–39

Epetedo residents narrated their quarter’s history as shaped by factors like enslavement, political strife among chiefly elites, soldiering, indigeneity and the British invasion of Lagos in 1851. These events, they believed, gave Epetedo its unique identity. From others’ perspectives, however, broader factors such as the British bombardment in 1851 and conflicts over the Obaship contributed to the creation or diminution of new quarters and later heightened tensions over land disputes.Footnote 32 But to the Epetedo occupants, these factors shaped their neighbourhood’s unique identity and sense of belonging to Lagos. The residents’ distinct perspectives influenced how they framed their quarter’s past.

Oba Kosoko’s resistance to the British invasion played a pivotal role in how Epetedo disputants explained their quarter’s origins. From 1845 to 1851, Kosoko ruled Lagos after overthrowing his uncle, Akitoye, in a civil war that elevated the Abagbon (war chiefs) over the Akarigbere (administrative) and Idejo (white-cap) chiefs. During his reign, Kosoko allocated land including areas like Olowogbowo (Figure 5) to his war chiefs, such as Tapa. In 1851, the British invasion forced Kosoko and his followers to flee to Epe, a coastal slave trading town. The British restored Akitoye to the throne, established a consul on Lagos Island and replaced the slave trade with the exportation of agricultural commodities, significantly reducing the Oba’s authority over Lagos.Footnote 33

Figure 5. Map of Lagos Island, c. 1950, Nigerian National Archives, Ibadan.

The Epetedo people invoked Kosoko’s battle with the British Navy to highlight their ancestors’ long-term settlement in Lagos. They discussed this history to show their founders’ long ties in Lagos, which gave them a distinct status. However, the Oshodi Family and the Epetedo Union presented their ancestors’ identities and relationship with Kosoko differently to support their competing claims. The Oshodi Family portrayed Tapa as Kosoko’s ‘prime minister’ while the Epetedo Union emphasized Tapa’s birth in Nupe Land (North Central Nigeria) and his former status as a domestic of Kosoko’s father, challenging the notion that their ancestors were merely Tapa’s slaves.Footnote 34 The Epetedo Union elaborated on this point by describing the quarter’s founders, including Tapa, as Kosoko’s followers or Epe repatriates. This framing underscored their ancestors’ shared ties to Kosoko both before 1851 and after 1862.

Akintan employed genealogy to trace the identities of Kosoko’s followers. In so doing, he sought to legitimize the identities of the landowners.Footnote 35 He emphasized that Kosoko’s followers were not strictly divided into slaveholders and enslaved people; many enslaved individuals also owned slaves who defended Kosoko’s interests. Enslaved people’s possession of their own slaves was common in the Bight of Benin. According to Kristin Mann, ‘slave/owners could employ their slaves in their own enterprises and also use them to fulfill obligations to others’.Footnote 36 Akintan described Epetedo’s first settlers as ‘comrades-in-arms and contemporaries’ who served under Kosoko’s leadership before establishing Epetedo.Footnote 37 He also acknowledged hierarchies among Kosoko’s followers, naming those that were war ministers (Balogun) or war captains (Oloko). In Akintan’s account, men like Tapa and Ajagun constituted war ministers who held their domestics, some of whom were war captains.Footnote 38 Like the war ministers, the war captains owned domestics too. Despite these distinctions, the Epetedo Union asserted that both war ministers and captains were warriors who ‘fought on the side of Kosoko, under their immediate Chiefs’.Footnote 39 Ultimately, the Epetedo Union maintained that Epetedo’s first settlers lived in Lagos before 1851, were Kosoko’s followers and were not Tapa’s slaves.

The British annexation of the island in 1861 paved the way for the return of Kosoko’s followers and that of Chief Tapa to Lagos in 1862. British officials decided to make Lagos a colony because the island was a strategic post for the expansion of commerce on the Niger. Oba Donsumu, under duress, signed a treaty ceding Lagos to the British crown. To promote trade in Lagos, the governor invited Kosoko, his warriors and their enslaved followers back to Lagos.Footnote 40 The circumstances under which the Epe returnees received land remained contentious, but the story illuminates how the litigants sought to explain their quarter’s uniqueness from other parts of Lagos. The competing narratives raised questions: who allocated the land to Kosoko’s followers and Chief Tapa? And did the allotment give the Epetedo settlers private property rights? Each group offered answers motivated by their quests to establish authority over the land.

Epetedo’s homespun historians saw their ancestors’ return as both a continuation of and a departure from their earlier settlement in Lagos. They did not always categorize their ancestors as first-comers or newcomers who paid tributes to the landowning chiefs.Footnote 41 Akintan acknowledged the Idejo chiefs as the main landowners whose ancestors settled in Lagos before the era of the slave trade. In a 1936 article, he stated ‘Epetedo lands, unlike other given lands in Lagos and the surrounding districts, stand on a different footing to those lands owned by the original owners of the Island of Lagos long before the coming of British Government who are known as the Idejos or the White Cap Chief…and a few others who are the direct descendants of Olofin.’Footnote 42 While Epetedo founders were not landowners like the Idejo chiefs, Akintan emphasized that their land access was facilitated by various figures.

In the Epetedo Union story, Chief Aromire, an Idejo chief, granted the land to Kosoko, who then distributed the land to his followers in 1862. Akintan concluded that Epe repatriates were given land ‘as a recompense for their faithful services, and as substitute for the properties which they had lost while at Epe’.Footnote 43 Additionally, the Epetedo Union mentioned that Governor Glover encouraged Epe repatriates’ return to Lagos and Chief Aromire to grant the land. This strategy exemplified disputants’ persuasive tactic of relying on an authority figure to validate the points.Footnote 44 Additionally, the group noted that Glover ‘took very great interest in their welfare and surveyed, as it were, plots of land belonging to each individual, in the form of a separate Compound or Court’.Footnote 45 The Epetedo Union cited their ancestors’ connections with Kosoko and Glover, along with the soldiers’ pre-1851 landownership as foundational to Epetedo’s settlement.

The Epetedo Union adopted many disputants’ justification for accessing land by describing its ancestors as autochthonous to Lagos.Footnote 46 The Epetedo Union sought to distinguish its founders from other Black diasporic migrants who settled in Lagos after 1851. These Black settlers from Sierra Leone and North and South America were formerly enslaved people, who moved to Lagos in search of land, trading opportunities and freedom. Adelusi-Adeluyi argues that the Black ‘returnees’ ‘reimagined and reinterpreted space in Lagos’ by creating new residential areas, claiming the land formerly occupied by Kosoko’s followers, and dividing land portioned for compounds and communal use into individual plots.Footnote 47

A comparison of the 1936 petition with the 1939 memorandum underscores how the Epetedo Union illustrated their ancestors’ indigenous identity. While one account enhanced the Epetedo settlers’ belonging to Lagos, the other categorized the Black settlers from the African diaspora as ‘foreigners’. In 1936, the Epetedo Union emphasized that after its ancestors’ return, they appealed first to Glover, who then requested Epetedo lands from Chief Aromire:

That on their arrival, and finding that their landed and other possessions in Lagos were being occupied by foreigners and other immigrants, representations were made to the Government, when lands at what is known as Epetedo, and which originally belonged to the Aromire Chieftaincy were through the good offices of the then Governor – Sir John Glover, of blessed memory – given as a substitute to your Petitioners’ ancestors, by Aromire Maya the then Head of the Aromire family.Footnote 48

This document suggests that Epetedo settlers lost their properties to the Black newcomers from the African diaspora and Akitoye’s followers. However, in its 1939 memorandum, the Epetedo Union presented a different version:

That before Kosoko and his people could consent to come back to Lagos, the question of settlement was obviously discussed since all those places where they had been living before they fled to Epe had been occupied by the people of Akitoye and other immigrants; and as they would have to become strangers in the land of their birth, they were assured before they left Epe for Lagos in 1862, that another plot would be provided for them for settlement in place of their original homes before their flight to Epe.Footnote 49

In contrast to the 1936 petition, the 1939 memorandum represented Kosoko’s followers as people who were born in Lagos and had realized their property loss to Akitoye’s followers and the Black migrants from the African diaspora before arriving in Lagos. The diverging accounts speak to the group’s insistence on their ancestors’ belonging to Lagos. In so doing, they reinforce the notion that land access constituted the bedrock of native identity.Footnote 50

Meanwhile, the Oshodi Family emphasized that Tapa’s diplomacy and bravery explained Aromire’s transfer of Epetedo lands solely to the Oshodi Family and its domestics. The family cited Tapa’s role in saving Akitoye’s life in 1845 during the latter’s conflict with Kosoko and a British official’s description of Tapa as Kosoko’s ‘prime minister’ in an official dispatch. These examples, according to the Oshodi Family, ascertained that Tapa ‘was in a position after the [cession of Lagos to the British] which entitled him to the grant of so large an area of land at Epetedo from Chief Aromire, the Idejo Chief of Lagos’.Footnote 51 The Oshodi Family justified Tapa’s stake to Epetedo because of his prior roles as a warrior, friend of the colonial administration and Kosoko’s spokesperson.

Despite their conflicting claims to Epetedo’s founding, the Oshodi Family and the Epetedo Union shared the same goals. Both groups developed historical accounts that would bolster their legal claims. Still, the account that they offered set their quarters’ identity apart as the domain of recent migrants in the same vein as Olowogbowo, which became primarily inhabited by Sierra Leonean migrants after 1851 or the Brazilian quarters, which was populated by Afro-Brazilian migrants. The Epetedo people framed their quarter’s identity as shaped by their ancestors’ settlement in Lagos before 1851, their status as soldiers and their connections to the chieftaincy elites. In so doing, the disputants illuminate a neighbourhood’s evolution from its inhabitants’ rendition of its past and struggles to shape its future.

The spatial politics of property disputes

Space played a central role in how the Epetedo Union and the Oshodi Family imagined and debated the ownership of Epetedo lands. People fought over properties not only to develop meanings of belonging, authority and power but also to protect access to the physical spaces that influenced their everyday activities.Footnote 52 Both factions’ writings highlighted stories of how the land, houses and compounds were used and changed.Footnote 53 These narratives provide insight into the residents’ lived experiences and spatial activities.

In their accounts of who owned the 21 compounds, Epetedo homespun historians represented the first settlers as not only landowners but also everyday building experts who transformed the land into a neighbourhood.Footnote 54 According to the Oshodi Family, the primary architect of Epetedo was Tapa. In the family’s 1939 memorandum, they stated that ‘Chief Oshodi Tapa divided the whole area, after clearing the bush, into twenty one [sic] Compounds and settled there with his own family and slaves as family lands.’Footnote 55 After settling in Epetedo, Tapa reserved one compound for himself and appointed a headman or arota to oversee the other compounds. For the Oshodi Family, tasks like clearing the bush and appointing a head man were fundamental to the development of Epetedo.

The Epetedo Union, however, attributed the construction of the quarter to various actors. In so doing, the group emphasized that the neighbourhood was the product of collective effort. Akintan noted that before the land was divided into 21 compounds, Kosoko’s war chiefs, including Aina Jakande and Tapa, stayed at Okepopo (Figure 5) for about a year. They then began clearing the ‘thick bush’ and constructing their huts around the districts. Later, they returned to Okepopo ‘to brush wood for their settlement’. By asserting that their ancestors cleared ‘unused’ land, both the Epetedo Union and the Oshodi Family sought to claim first-comers’ status.Footnote 56 While Akintan focused on the war chiefs’ building work, enslaved people who testified in the Moriamo Dakolo and 15 others vs. Saka Oshodi trial also discussed their contributions. Saka Alli Iwo, who was estimated to be 100 years old, recalled that he and other enslaved people first stayed at Okepopo. When they learned that their masters would be granted land, Saka and the others cleared the bush and made mud to build the houses.Footnote 57

Saka’s recollections resembled the communal process of house building in the nineteenth century, when landowners were assisted by their friends, relatives or enslaved people. Many used mud because it kept the house interior cooler and was more affordable than bricks or imported corrugated iron sheets. Builders sourced the mud from locations such as the lagoon, Iddo Island and Ebute Metta (Figure 3).Footnote 58 By referencing the construction materials and labourers, the Epetedo Union and the Oshodi Family reinforced their ancestors’ role in transforming the land into a permanent space for future generations.Footnote 59

The compounds were central to Epetedo’s identity and provide insight into the residents’ use of space. A typical Lagos compound consisted of houses arranged around an open courtyard with one or two entrances. It varied in length from 10 to 40 yards. While compound structures were common in West African towns, Epetedo’s division into 21 compounds set it apart from other Lagos quarters.Footnote 60 These areas consisted of a combination of compounds built next to two-floor and bungalow houses. By the 1930s, many Lagos compounds were divided to build dwellings that were leased to the migrants settling in the city and its outskirts.Footnote 61 Epetedo compounds remained intact, with the exception of Alfa Iwo’s compound, which the British government acquired in 1927.

Like many homeowners, Epetedo residents built one-to-two-floor houses within their compounds, which they leased to tenants or occupied with their families.Footnote 62 In 1942, Akintan estimated that each of the 20 compounds contained about 20 houses.Footnote 63 Some compounds in Epetedo included an Iga (palace) for the chief facing the entrance. The compounds were hubs for various activities, with spaces for cooking, sleeping, religious practices and recreation, as well as shops, a cinema, a police station, and one of two cemeteries reserved for Muslims (Figure 2).Footnote 64 In some cases, such as with the Oshodi Family, relatives were buried in their compounds as part of maintaining the pre-colonial home burial practice that enabled the dead’s transition into ancestors.Footnote 65

The land disputes made houses central to court cases and the residents’ mobilization for new property laws. The residents’ drive to protect their houses fuelled their activism. Both the Epetedo Union and the Oshodi Family strategized about how to regain control of their properties within their dwellings. The Oshodi Family regularly met at Oshodi’s compound on Oshodi Street (Figure 2) while the Epetedo Union, especially the executive committee, convened every Friday at Mr Kansumu Aweniya’s house at Oguntusi Court (Figure 2) until his death in 1936.Footnote 66 Akintan likely traversed the alleyways between the compounds and the streets to collect the signatures for the 1936 petition. These individuals’ inclusion of their home addresses in the petition underscores the importance of the residential spaces as part of the property disputes.

The struggle for a new land law led to internal conflicts within the quarter, exacerbating tensions among the residents. The rivalry between the Epetedo Union and the Oshodi Family strained neighbourly relations, almost resulting in street brawls. An anonymous 1931 letter to the editor of the Lagos Daily News recounted one such conflict. The author, who called himself ‘an interested member’, wanted to inform the public about some disturbances among young men in Epetedo, which he claimed was created by some ‘worthless elders who styled themselves the Arotas’. In 1930, about 100 young men formed the Epetedo Social Society to bring about ‘peace, unity, and concord’ and avoid the divisive court cases or disputes between the elders. This claim suggests that the struggle over Epetedo land was being fought among older people. The Epetedo Social Society partly achieved its goal by celebrating a member’s wedding in January 1931. However, the organization’s efforts to maintain peace ended abruptly after some members disapproved of Mr Badaru Oshodi’s election as president. Some members, whose fathers were not on good terms with Badaru, quit the Epetedo Social Society. The tension over Badaru’s election almost led to a physical brawl during one of the group’s meetings. Shortly after this incident, the Epetedo Social Society became inactive because of the older generation’s influence.Footnote 67

Despite the conflicts among Epetedo occupants, some evidence shows that the central figures in the Epetedo Union and the Oshodi Family collaborated before 1927. These interactions, though rarely mentioned in court battles or historical texts, played a significant role in the socio-political life of the quarter. In 1924, Akintan published two articles in Eleti Ofe to celebrate the election of Saka Oshodi as the chief and head of the Oshodi Family. One of the articles also shared that Akintan and Aweniya participated in a public celebration to mark Saka’s new title.Footnote 68 However, by 1927, when the Moriamo Dakolo and 15 others vs. Saka Oshodi began, Akintan had dissociated himself from the Oshodi Family, likely due to mounting tensions surrounding Epetedo lands. His ally Aweniya testified at the 1927 trial and served as one of the Epetedo Union’s presidents from 1927 to 1936.Footnote 69 Both men led the Epetedo Union’s campaign to weaken the Oshodi Family’s claims over the Epetedo properties.

The Epetedo land conflicts did not only surface in the British courts, newspapers and colonial administrative offices, but they also reshaped the residents’ interactions within the neighbourhood. The Epetedo Union and the Oshodi Family used these spaces to plan their defence strategies as they sought to create a new property law. The compounds, which were central to residents’ livelihoods and identities, became arenas for political manoeuvring, as both groups used their homes to advance their claims and mobilize support for their cause. At the same time, these disputes intensified social divisions among neighbours. The formation of the Epetedo Social Society in 1930 reflected the young men’s attempt to mitigate these tensions, but the society’s brief existence highlighted how deeply the land disputes affected interpersonal relations.

Conclusion

The Epetedo Union and the Oshodi Family’s activism sparked tension among neighbours and altered how residents exercised property rights. In 1939, the British government established a public inquiry into land titles, led by Mervyn Tew, the British judge, who had presided over the 1928 trial of Moriamo Dakolo and 15 others vs. Saka Oshodi. Initially, the Epetedo Union saw the inquiry as a response to its 1936 petition for a similar action.Footnote 70 However, the British administrators used the commission to suppress indigenous landowners challenging the crown’s claim over ‘unoccupied lands’.Footnote 71 The inquiry’s terms of reference aimed to solidify the British government’s control over land. The terms included asking the commission to specify the British crown’s power over land and declare all the highways, roads and lanes in public use as government properties.Footnote 72 Representatives from the Epetedo Union, the Oshodi Family and Lagos chiefs appeared before Tew and submitted memoranda to defend their claims.Footnote 73 In 1947, the British government passed four bills, which included the Epetedo Lands Ordinance.

While the British government hoped the bills would resolve land disputes, they instead created competition for property rights under new terms.Footnote 74 The bill supported the Oshodi Family’s claim that Tapa owned Epetedo. It also allowed occupants of 18 compounds to relinquish the Oshodi Family’s claim over the land by paying a fee that was two and a half times the value of the land and houses to gain enfranchisement. Shortly after the Epetedo land ordinance was approved, Akintan and some Epetedo Union members sought enfranchisement to sell their land without facing lawsuits. Meanwhile, the Oshodi Family condemned the enfranchisement clause, viewing it as a threat to their sole control over Epetedo.Footnote 75 The new bill reshaped the relationships among Epetedo residents, some of whom gained private property rights, while the Oshodi Family retained its claims of ownership.

The competing narratives of Epetedo’s history reveal how residents understood their past and used their spaces. The historical accounts defending property rights were crucial not only in legal disputes but also in shaping neighbourhood identity. In these writings, disputants highlighted the events, historical actors and construction practices that shaped the quarter’s evolution. The case of Epetedo deepens scholarly understanding about the diverse formation of residential enclaves. Epetedo people viewed their quarter as unique, claiming that their ancestors were given land there as compensation for properties lost when they fled Lagos in 1851, for serving their masters, and for holding political positions.

The spatial politics played a prominent role in the property disputes. Residents’ socio-political relations and everyday life often remain in the background in land conflict studies or are obscured in court testimonies. Akintan’s friendly exchanges with the Oshodi Family in 1924 and the formation of the Epetedo Social Society in 1930 illuminate how the residents sought to resolve neighbourly tensions. The disputants made the houses and compounds central to their conflicts, using these spaces to strategize their political goals. The history of land disputes in Epetedo provides insight into residents’ voices and initiatives in the transformation of their neighbourhood, recognizing their agency in the history of contested land and the ways in which they shaped and interpreted their own narratives.

Acknowledgments

No intellectual labour of this kind is complete without acknowledging the epistemic communities, colleagues, mentors and friends who made it possible. I am grateful to the residents of Epetedo – particularly Imam Mogaji, the Oshodi Chieftaincy Family Council, Alhaji Gboyega Oshodi and Alhaji Surakat Oshodi – for their generosity in sharing their records, stories and time. My deepest gratitude goes to the late Chief Adekunle Alli, whose mentorship and research informed this work. I also appreciate the critical insights of Ademide Adelusi-Adeluyi, Wes Alcenat, Mamadou Diouf, Delali Kumavie, Jimoh Mufutau Oriyomi, Kwame Otu and Gillian Steinberg, whose feedback helped refine the article. I would like to extend my appreciation to the anonymous reviewer and to the special issue editors, Norman Aselmeyer and Avner Ofrath, for their thoughtful comments and editorial guidance. Any errors in this article are my own.

Funding statement

The fieldwork research for this article was supported by funding from the Council on Library and Information Resources’ Mellon Fellowships for Dissertation Research in Original Sources.