Introduction

When Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promised that 2015 would be “the last federal election conducted under the first-past-the-post voting system,”Footnote 1 many advocates of electoral reform were optimistic that change was coming. However, once it became clear that the Liberal government had no intention of acting on the recommendations of the all-party House of Commons Special Committee on Electoral Reform,Footnote 2 it seemed as if the window of opportunity had closed, leaving many would-be reformers disappointed with the continuing use of the single-member plurality system (Stone, Reference Stone2017).

In the years since, there has been no discernable movement on the issue of electoral reform, at least at the federal level. The subnational level, however, is another story altogether. At the time of writing, the Yukon, for instance, is currently holding a citizens’ assembly to decide whether and how to reform their voting system.Footnote 3

Throughout the last hundred years, it is at the subnational level where most of Canada's electoral reform efforts have been focussed. This article examines those reforms. We draw on 68 attempted sub-national reforms since 1916, of which 54 succeeded. Our analysis considers both the nature of the (proposed) alternative and the means or process by which reform was attempted. In doing so, we identify three paradoxical trends.

The first trend relates to the actors and institutions whose support is necessary for reform to occur. Specifically, we find that although reduced constraints and lower stakes at the municipal level should encourage more frequent electoral experimentation, changes to provincial legislation have left many local governments without the authority to alter their own electoral rules.

The second paradox relates to the role of public input. Despite the fact that public engagement has become a key aspect of modern reform efforts, and although governments have developed new and innovative means of public engagement, those same governments have also introduced new obstacles that effectively dilute or impede the direct impact of majority opinion on the reform process. As a result, while the academic literature now considers public input to be essential, plebiscites today are subject to additional constraints such as turnout and supermajority requirements that were not present in the past.

Finally, the third paradox relates to the enduring power of political tradition. Theoretically, some of the most entrenched barriers to reform ought to remain consistent regardless of the proposed alternative. That is, the parties that benefit from the existing rules will be the ones to decide whether or not to pursue reform, irrespective of the system by which that government was elected. In practice, however, we find that sub-national governments often employ different processes when attempting reform, depending on the nature of the proposed change. As a result, reforms aiming to (re)introduce plurality are generally subject to fewer hurdles.

This article proceeds as follows. After explaining our focus on the subnational level, we proceed with a general discussion of the barriers to reform at all levels, elaborating on the aforementioned paradoxes in the context of the wider academic literature. From there, we introduce our data and discuss questions of coding and operationalization. Our analysis, organized by time period, is followed by a discussion that explores each of the three paradoxes in turn. We conclude with a brief consideration of wider implications.

Why the Subnational Level?

Electoral reform is rare. Globally, depending on one's precise definition, the number of major reforms at the national level ranges between 6 and 19 between 1945 and 2017 (see Colomer, Reference Colomer and Colomer2004; Katz, Reference Katz2005; Renwick, Reference Renwick2010). At the subnational level, however, reform occurs much more frequently. This is explained (at least in part) by an increase in the number of observations by several orders of magnitude. Thus, in focusing on the subnational level in Canada, we follow the advice of Gerring (Reference Gerring2004) to move down one (or more) level(s) of analysis in order to expand the range of available data from 0 attempted reforms (federal level)Footnote 4 to 14 (provincial) to 68 (municipal and provincial).

As Katz (Reference Katz2005) notes, subnational changes to the electoral system can be just as profound as national reforms. This is especially true in a federal context such as Canada, where provinces have constitutional dominion over key policy areas. By the same token, because citizens engage most frequently with municipal governments, which have a direct impact on their daily lives, changes to municipal electoral systems are also likely to have a pronounced effect.

That being said, it is likely that the dynamics that affect reform work differently at different levels, for instance, due to the absence of parties in many municipal councils. Notwithstanding any such differences, however, stasis remains the norm at all levels of government. Inertia is difficult to overcome.

Barriers to Reform

The rarity of electoral reform can be explained by political, cultural and institutional barriers to changing the rules of the game. Rahat and Hazan (Reference Rahat and Hazan2011) distinguish between at least seven distinct types of barriers: a) the procedural advantage of the status quo as default; b) political tradition; c) the relationship between a society and its institutions (that is, the compatibility of consensus institutions for heterogeneous societies and majoritarian rules for more homogenous societies); d) system-level rationale (or, the degree to which an extant system continues to function as expected); e) the vested interests of political actors; f) coalition politics; and g) disagreement over the design of an alternative.

We find evidence of most of these barriers within our sample.Footnote 5 In fact, such barriers are often overlapping and mutually reinforcing. Thus, we have clustered them into three broad categories. Our first category, level of government (that is, municipal vs. provincial), includes consideration of both vested interests (e) and veto players (f). A second category is focused on the reform process and incorporates the barriers of inertia (a) and veto players (f). The third category, the nature of the proposed alternative, involves aspects of political tradition (b), the relationship between a society and its institutions (c), and, to a lesser extent, the degree to which the existing system continues to function as expected (d). Below, we explain why each factor is likely to matter, drawing on Rahat and Hazan (Reference Rahat and Hazan2011) and grounding our expectations in the wider academic literature on electoral system change.

Level of government

In a democratic context, major changes to the electoral system can only be implemented by governments. However, once in government, actors who benefit from the existing system have little incentive to change the rules that allowed them to win. Bol and Pilet (Reference Bol and Pilet2011), for example, show that parties that have been in power for a long time are much less likely to support reform than those that win only some of the time. Rahat and Hazan (Reference Rahat and Hazan2011) describe this as a problem of vested interests. Following Benoit (Reference Benoit2004), they argue we should only expect electoral reform to succeed where the political parties with the power to change the existing system expect to benefit by doing so.

Political institutions can exacerbate this problem, especially where the reform process requires the support of multiple veto players, all or most of whom may have a vested electoral interest in preserving the status quo. Hooghe and Deschouwer (Reference Hooghe and Deschouwer2011), for instance, argue that this dynamic helps to explain the endurance of proportional representation in Belgium. Other authors have made similar arguments in the cases of the Netherlands (Van der Kolk, Reference Van der Kolk2007) and Slovenia, Czechia and Romania (Nikolenyi, Reference Nikolenyi2001). Taken together, Rahat and Hazan (Reference Rahat and Hazan2011) argue that veto players and vested interests are two of the most difficult barriers to overcome.

For our purposes, we expect these dynamics to affect the reform process (see below) and to play out differently depending on the level of government. Unlike provincial legislatures, most Canadian municipalities do not have political parties.Footnote 6 This matters because parties play an important role in the reform process by coordinating interests. Whether a party benefits from existing (dis)proportionality or expects to do so in the future is likely to influence its stance on reform. This seems especially relevant at the provincial level.

In the absence of political parties, municipal reforms are not subject to the same partisan barriers to reform. In theory, this should make reforms more likely to succeed at the municipal level. That is not to suggest that established municipal actors have no interest in maintaining the status quo, which they clearly do. However, we expect these interests to be more of an obstacle at the provincial level.

Reform process

As political institutions go, electoral systems are particularly sticky. Per Rahat and Hazan (Reference Rahat and Hazan2011), this creates an inherent bias in favour of the status quo, requiring reformers to overcome procedural obstacles. In the case of electoral reform, these obstacles are often more demanding than the mere passage of legislation.

As the next section elaborates, our analysis distinguishes between three distinct processes through which Canadian provinces and municipalities have attempted electoral reform: plebiscites, municipal ordinance and provincial legislation. Importantly, following the logic of Rahat and Hazan (Reference Rahat and Hazan2011), each process requires the support of a different coalition of actors, which is likely to affect the outcome.

Provincial legislation requires simple majority support to pass. In Canada, provincial politics is dominated by political parties. Whether those parties benefit from the existing rules, and whether the governing party is dependent on the support of one or more (tacit) coalition partners are likely to affect the outcome.

At the municipal level, legislation also requires the support of a simple majority. Without parties to coordinate interests and actions, city councillors have considerable latitude when it comes to supporting (or blocking) reform. In theory, if their constituents demand change, councillors have less incentive to vote against it. Even so, it is important to keep in mind that while councillors may not be affiliated with a political party, they still benefit from the existing rules. Thus, the issue of inertia remains.

Importantly, city councils must also have the legal authority to pass such legislation in the first place. While provinces have constitutional authority over the design and change of their own voting systems, municipalities do not. This effectively introduces another veto player at the municipal level: the province.

In addition to municipal and provincial legislation, plebiscites constitute a third path to reform. Perhaps in response to the self-interest-based hurdles noted by Benoit (Reference Benoit2004) and others, Renwick (Reference Renwick2010: 251–54) observes a growing trend that emphasizes the need for greater public involvement in electoral reform, as voters increasingly distrust political parties and suspect that reforms might be driven by self-serving interests. We therefore expect to find an increase in public engagement over time.

The nature of the alternative

If veto players and vested interests were the only barriers to electoral reform, the nature of the proposed alternative would be irrelevant. That is because they apply equally irrespective of the existing system and the proposed alternative, creating an inherent bias towards stasis. Thus, even in cases where a new system has been introduced, the parties that benefit from the (new) rules will be the ones to decide whether to retain them (per Hooghe and Deschouwer, Reference Hooghe and Deschouwer2011).

However, the literature is clear that political culture and context also matter. Rahat and Hazan (Reference Rahat and Hazan2011) therefore emphasize the importance of both political tradition and the relationship between a society and its political institutions. In Canada and other Anglo-American democracies, Lijphart (Reference Lijphart1994, Reference Lijphart1999) and others have noted a culturally ingrained bias in favour of the adversarial nature of majoritarianism (see Finer, Reference Finer1975), while Continental democracies favour the more consensual approach of proportional representation.

In the absence of anomalous outcomes that are inconsistent with expectations about how a system is meant to function, Rahat and Hazan (Reference Rahat and Hazan2011) suggest that electoral reform is unlikely. In a majoritarian context, such outcomes could include events like plurality reversals (Shugart, Reference Shugart and Blais2008) or a significant increase in the number of parties (Colomer, Reference Colomer2005). However, as Siaroff (Reference Siaroff2003) shows, anomalous outcomes do not always lead to electoral change.

Taken together, these factors effectively place the onus on proponents of reform to prove that the proposed alternative system represents an improvement over the status quo—unless that alternative involves reverting back to plurality rule, in which case no such argument is necessary.

This logic is reflected in the general tendency in the existing literature to dismiss the short-lived use of non-plurality electoral systems as failed experiments. It also leads us to expect that non-plurality alternatives are likely to be subject to additional scrutiny—and perhaps even additional barriers—when it comes to the design of the reform process.

Data and Operationalization

Data

Our dataset includes 68 observations, each representing an attempt to change the existing electoral system at either the municipal or provincial level. Our analysis covers the period from 1916 to 2023. To our knowledge, this includes all subnational reforms that have been attempted in Canada. Our data come from a wide variety of primary and secondary sources. For easy reference, each observation is summarized in the Appendix.

Electoral reform

We define electoral reform as the switch from any plurality system (including the block vote, limited vote, single member plurality, or some combination thereof) to any alternative that uses ranked ballots (for example, alternative vote) or proportional representation (for example, list proportional representation, mixed-member proportional), or some combination thereof (for example, single transferable vote). Or, vice versa.

This slightly unorthodox definition breaks with accepted practice in the academic literature, where, following Lijphart (Reference Lijphart1994), major electoral system reform is typically defined more narrowly as the switch from one system to another, even if that system remains in the same broad family. Although subtle distinctions between electoral systems have real meaning for political scientists, we must be conscious of the fact that practitioners attempting reform and members of the voting public have not always viewed the issue of electoral reform as academics do today. Thus, our operationalization follows a different logic, outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. Operationalization of Attempted Electoral Reform

While the trend in the contemporary academic literature is to differentiate between electoral systems within the plurality/majority family, many electoral districts in Canada have historically employed different methods of counting and voting that cannot be accurately described as single member plurality (SMP). For example, the block vote (BV), in which voters cast as many votes as there are seats to be filled, has been widely used in municipal elections across the country. Even at the provincial level, the use of multimember districts persisted from confederation until well into the twentieth century. In British Columbia, for example, multimember districts were not eliminated until 1991, when the province passed the Electoral Districts Act, SBC 1990 c. 39. Thus, our “plurality” category (left) is meant to capture the surprisingly diverse range of electoral systems that were in use at both the municipal and provincial levels prior to (attempted) reform.

If we were to apply the conventional academic definition of electoral reform to the study of subnational electoral reform in Canada, the number of cases in our dataset would increase dramatically. This is due to the historical prevalence of multimember plurality districts in subnational elections. At the municipal level, such methods of at-large voting were commonplace, typically using a variation of BV or limited vote (LV). At the provincial level, historically speaking, it was not uncommon for provinces to use some combination of SMP (in rural districts) and at-large voting (BV, LV) in more populous, urban districts.

For example, in British Columbia's first provincial election in 1871, 25 MLAs were elected from just 12 districts, only one of which used SMP (Elections BC, 1988: 535). Similarly, between 1885 and 1893, Ontario used the LV in multimember districts in Toronto and SMP in rural areas elsewhere. Both Alberta and Manitoba introduced the use of the plurality BV in urban areas in 1909 and 1914, respectively, while retaining SMP in rural districts.

Notwithstanding this, using the operationalization outlined in Table 1, these cases are not captured in our definition of electoral reform, as the LV, BV, and urban/rural hybrid systems combining SMP with either all fall under the same family of “plurality” systems.

Of course, this operationalization of reform does raise an interesting question: why not count the switch from the BV to SMP as a reform in its own right? Our answer is based on the use of historical data in the proceeding analysis, which requires us to think about reform in a different light. While this differentiation between systems makes sense given the tendency to focus on the postwar period, it does not capture the diversity of examples in our study. In fact, we argue that the switch between one plurality system to another has not historically been understood as constituting major electoral system reform in Canada: not by politicians, nor the voting public, nor even the courts.

This logic reflects a growing tendency in the academic literature to re-evaluate what constitutes major electoral reform. As Katz (Reference Katz2005: 69) concludes, there is “no clear dividing line between major and minor reforms; even more, there is no clear dividing line between reforms that might be considered minor, and those that might be called trivial, technical or no reform at all.” Acting on the advice of Jacobs and Leyenaar (Reference Jacobs and Leyenaar2011), our distinction between major and minor reform is based on context, perception and case-specific expertise. We argue that the switch from one of the “plurality” systems in the left column of Table 1 to another plurality system would constitute a relatively minor or technical reform more akin to redistricting. Only the switch from “plurality” system to an “other” system (or vice versa) would represent a major reform worthy of serious public debate/engagement.

Why not simply distinguish between plurality/majority systems and proportional ones? Our answer is that while the switch between, say, the BV and SMP would not have been understood by Canadian politicians and voters as a major change, the same cannot be said of the switch between SMP and the alternative vote (AV). Despite being members of the same broad (non-proportional) family, both the AV and the two-round system (TRS) use a different logic than SMP, requiring a majority winner, rather than the “most votes wins” logic common to plurality systems like BV or SMP. These differences—in particular, the use of a second round (TRS), or a ranked ballot/instant runoff (AV)—are sufficiently fundamental that they would be understood as major changes by Canadian voters and politicians both past and present.

Thus, our “plurality” category is restricted to systems employing a “most votes wins” logic, while the “other” category includes majoritarian, mixed and proportional systems (as well as a few others, such as the Borda count that have never been seriously debated for use in Canada).

Attempted reform

We define an attempted reform as a process that has the potential to result in a legally binding change to the existing electoral system. While there have been some notable recent attempts to involve the courts in electoral reform,Footnote 7 in Canada such processes are almost always government initiated. We identify three distinct reform processes in the data: plebiscites (both provincial and municipal), municipal ordinance and provincial legislation. These processes are summarized in Table 2

Table 2. Attempted Reforms by Process and Level of Government

It is worth noting that the range of possible reform processes differs depending on the level of government. For instance, it is simply not possible for municipalities to change the provincial electoral system by any means. Conversely, however, provinces are well within their constitutional authority to modify municipal electoral systems with an act of provincial legislation, with or without support from the local level (cf Freeman, Reference Freeman2020).

In some cases, successive reforms occurred within a very short timeframe. In Victoria, for example, STV was introduced by plebiscite in 1920, and repealed the following year by the same process. There is a general tendency in the existing literature to dismiss the short-lived use of alternative electoral systems as failed experiments. However, we count these “experiments” as genuine attempts to reform the electoral system, as this provides a clearer picture of the relative popularity and rate of success of various processes/alternatives. This also helps us to understand the conditions under which municipalities may be free (or not) to engage in this type of “experimentation” in the first place.

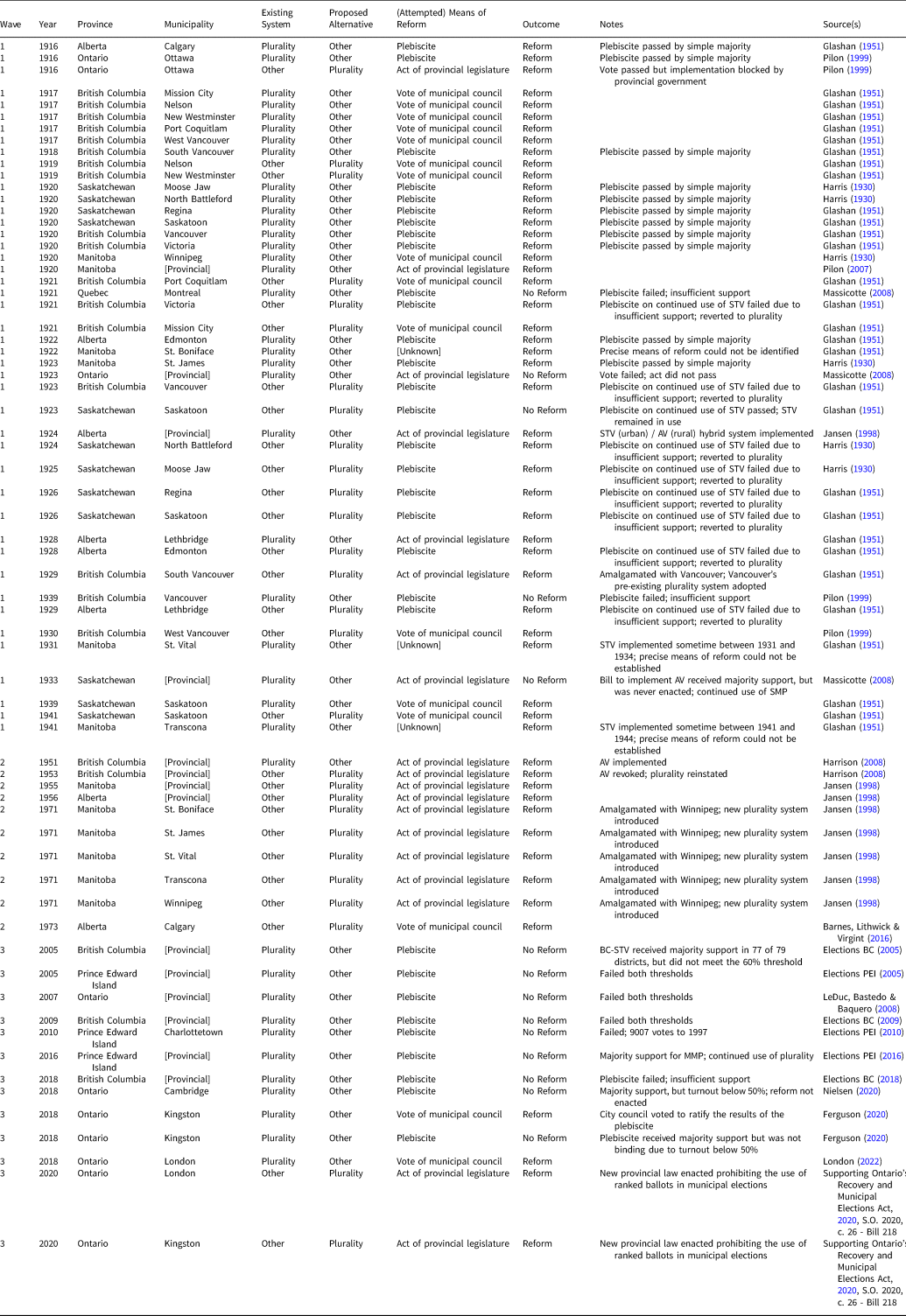

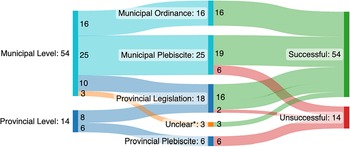

The Sankey diagrams below illustrate our dataset. Of 68 attempted reforms, 54 succeeded while the remaining 14 failed. In total, 14 attempted reforms occurred at the provincial level, of which only 6 were successful. The remaining 54 cases represent (attempted) changes to municipal electoral systems. All but 6 of those succeeded. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. Attempted Electoral Reforms, Municipal vs. Provincial Level, by Outcome

Figure 2 further distinguishes between the most common reform processes at the various levels of government. Again, it is important to keep in mind that Canadian municipalities are creatures of the provinces, and their ability to act independently, especially on the issue of electoral reform, varies across time and space. Thus, while it is the prerogative of the provinces to intervene directly in municipal affairs (for example, to impose a new electoral system via provincial legislation), individual municipalities may or may not have the necessary authority to hold plebiscites or pass ordinances at any given time.

Figure 2. Attempted Electoral Reforms by Level, Process and Outcome

At the municipal level, plebiscites have historically been the most common means of attempted reform (25 out of 54 attempts, of which 19 succeeded). However, it is worth noting these votes have a much lower success rate than other means, including the passage of municipal ordinance (16 attempts, all successful) or provincial legislation (10 attempts, all successful). In the remaining three municipal cases, the precise means of reform could not be established.

At the provincial level, reliance on legislation has been the most common means of reform, used in 8 out of 14 attempts, of which 6 succeeded. Plebiscites were used in the remaining 6 attempts. While the provincial use of plebiscites is comparable to the municipal level (43% and 46%, respectively), the success rate is markedly different. No provincial plebiscite on electoral reform has been successful in Canada. This suggests the level of government and the reform process are both important when it comes to explaining subnational electoral reform in Canada.

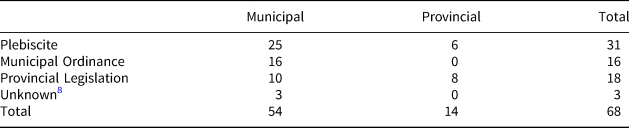

Figure 3 illustrates the outcome of attempted reforms based on the nature of the proposed alternative electoral system. Using the distinction between plurality and other systems described above, our dataset includes 40 attempts to switch from plurality to other, and 28 attempted conversions from other to plurality. Interestingly, as Figure 3 shows, while attempts to change an existing plurality system usually succeeded (27 out of 40 attempts), attempts to change back to plurality (that is, from an “other” system) were almost always successful (27 out of 28 attempts).

Figure 3. Attempted Electoral Reforms by Proposed Alternative and Outcome

Figure 4 also shows the breakdown of attempted reforms by the nature of the proposed alternative system, but further distinguishes by the process via which reform was attempted. Of 40 attempts to replace an existing plurality with an alternative from the “other” family, most (22 or 55%) involved plebiscites at either the municipal or provincial level. By contrast, most attempts to revert back to plurality from an other system relied on legislation (19 out of 28). Attempts to reintroduce plurality systems were also much more likely to succeed (27 out of 28 attempts) than attempts to introduce other systems (27 out of 40 attempts).

Figure 4. Attempted Electoral Reforms by Proposed Alternative, Process and Outcome

Figure 5 is a timeline of subnational electoral reform in Canada. Reforms entailing a switch from plurality to other are indicated above the horizontal line. Reforms from other to plurality are depicted below the line. The different colours represent different processes of (attempted) reform (see the legend in the lower right corner). Reforms involving a municipal plebiscite are indicated in orange. Reforms involving municipal ordinance are in green. Reforms via provincial legislation are in blue. Yellow signifies reforms via provincial plebiscite. For each of the aforementioned methods, darker shades of the same colour indicate successful reform, while lighter shades indicate failed attempts. In the three cases in grey, the precise means of reform could not be determined.

Figure 5. Timeline of Attempted Electoral Reforms in Canadian Provinces and Municipalities

Time period

Although our focus is on the subnational level in Canada, it is worth noting that national and even international trends can influence developments at the local and regional levels. Carstairs (Reference Carstairs1980), for example, documents the considerable degree of international cross-pollination involved in the dissemination of proportional representation in Western Europe. Bol, Pilet and Riera (Reference Bol, Pilet and Riera2015) similarly find evidence of a cross-national diffusion effect, whereby national legislators are more likely to engage in electoral reform when a large number of peer countries have made similar choices within the last two or three years.

In the next section, we identify several historical periods or waves of reform, which are evident on the timeline. We argue that each wave is characterized by both the (proposed) alternative and the method of (attempted) reform.

The First Wave of Reform, between 1916 and 1941, was dominated by a push to introduce the single transferable vote, especially in large, urban areas, and was primarily concentrated in the Western provinces. During this period, plebiscites were the most common means of implementing reform (and undoing it). As Figure 5 illustrates, this First Wave accounts for 45 of 68 attempts.

The Second Wave of Reform, characterized by a return to plurality from the mid-1950s to the late 1970s, largely undid the few remaining reforms from the First Wave. Of the 10 reforms attempted during this period, 9 were initiated by provincial governments. Notably, all succeeded.

Finally, a Third Wave of Reform in the 2000s saw renewed interest in public consultation and proportional or semi-proportional systems. During this period, 9 out of 13 attempts were conducted via plebiscite. However, despite a clear trend in favour of increased public input, only 4 out of 13 attempts were successful, all of which occurred at the municipal level and none of which involved a plebiscite.

First Wave of Reform, 1916 to 1941

In Canada in 1915, every electoral system used by every level of government was a variation of plurality rule. That is not to suggest that every electoral district at every level of government used precisely the same variation. As noted above, the use of multimember districts was quite common, historically speaking, especially at the subnational level. However, prior to 1915, no multimember district in Canada could accurately be described as using proportional representation (PR) or ranked ballots.

Ashtabula, Ohio, became the first North American city to implement PR in 1915, sparking a trend that would spread to dozens of other cities on both sides of the border. The earliest attempts to introduce PR to Canada occurred in 1916. In that year, plebiscites were held in Calgary and Ottawa. Both votes passed with a simple majority, although in the latter case the provincial government subsequently intervened to prevent the introduction of PR.

Between 1916 and 1920, 23 cities and four provinces—primarily in Western Canada—attempted to introduce the single transferable vote, or some variation thereof.Footnote 9 In total, we identify 45 attempted reforms during the First Wave: 40 at the municipal level and 4 at the provincial level. Of those 45 attempts, 28 sought to replace a plurality system with an alternative from the other family (Figure 6), while the remainder represent reversions to plurality (Figure 7).

Figure 6. Reform Process and Outcome (First Wave of Reform 1916–1941, Plurality to Other)

Figure 7. Reform Process and Outcome (First Wave of Reform 1916–1941, Other to Plurality)

Of the 28 attempts to replace existing plurality systems, most (24 or 86%) succeeded. Of the 4 failed attempts, 2 occurred at the provincial level and involved the (attempted) passage of legislation, while the other 2 occurred at the municipal level and involved plebiscites.

Note that the 24 attempts in which other systems were successfully implemented in Figure 6 are, in fact, precisely the same 24 other attempts on the lefthand side in Figure 7. In this way, Figure 7 can be read as a continuation of the “Other Implemented” branch on the right side of Figure 6.

Neither of the two provinces (Alberta and Manitoba) that implemented other systems reverted to plurality during the First Wave. In addition, 6 municipalitiesFootnote 10 that introduced other systems retained their use through the end of the period. However, in most cities that implemented PR during the First Wave, the use of other systems was short-lived. In Victoria, Vancouver, North Battleford, Moose Jaw, Regina and Edmonton, for instance, PR was in use for less than 10 years, and in Ottawa a plebiscite to implement PR was blocked by the province within a matter of days.

Interestingly, however, as the timeline in Figure 5 shows, the push to implement other systems largely overlapped with the reversion to plurality, suggesting that new municipalities became interested in PR even as early adopters switched back. Thus, Figures 6 and 7 should be understood as occurring simultaneously.

A comparison of Figures 6 and 7 suggests that during the First Wave, municipal plebiscites were the most common means of implementing PR (13 out of 28 attempts) and of repealing it (9 out of 17 attempts). All plebiscites during this period were held at the municipal level. Several municipalities held multiple votes on the issue, including Saskatoon, which voted at least four separate times on the use of PR.Footnote 11

Of the 13 plebiscites on implementing a non-plurality system (Figure 6), 11 received majority support (85% success rate). Of the 9 plebiscites proposing a return to plurality, 8 succeeded (89% success rate). These high success rates can be explained in part by the fact that plebiscites from this era required a simple majority to pass, and voter turnout was often low.

A further 13 municipal reforms were implemented via municipal ordinance (7 plurality to other; 6 other to plurality). All four attempts to implement reform at the provincial level—in Alberta, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Ontario—involved acts of the provincial legislature, although only two succeeded (Alberta 1924 and Manitoba 1920).Footnote 12, Footnote 13, Footnote 14 The provinces directly intervened in municipal reforms only three times during the First Wave: in Ottawa in 1916 (referendum results overturned by provincial intervention), in Lethbridge in 1928 (other implemented) and in South Vancouver in 1929 (plurality restored).Footnote 15

As Pilon (Reference Pilon and Milner1999) shows, the primary impetus for reform during the First Wave of Reform came from large, urban areas, where social upheaval in the aftermath of WWI exacerbated existing political cleavages (for example, English-French) and heralded a chorus of new political voices (for example, women, returning soldiers, organized labour and Western farmers), effectively disrupting the barriers of political tradition and social structures identified by Rahat and Hazan (Reference Rahat and Hazan2010).

Seen in this light, it is not surprising that the first Canadian districts to make the switch to PR were Western municipalities, where working-class parties and progressive movements were strongest (see Pilon, Reference Pilon and Milner1999). This is evident in large number of (Western) municipalities that attempted reform (23 in total), including all four Western provincial capitals and four of Canada's 10 largest cities at the time (Johnston and Koene, Reference Johnston, Koene, Bowler and Grofman2000: 205).

At the provincial level, in Ontario and in the West, this period witnessed the collapse of the two-party system that had existed since confederation (Massicotte, Reference Massicotte and Blais2008: 112). In that sense, the shift to adopt STV in Winnipeg can also partly be understood as a response to the electoral threat posed by these newcomer parties. In Manitoba, for example, Labour, which formed in 1918, went on to take 9 of 55 seats in the 1920 election with 17.7 per cent of the vote, while the Farmers (UFM) took 12 seats with 14.1 per cent. Both Labour and the UFM were ideologically committed to urban STV, ensuring that the new system met with little opposition even after the Liberals were reduced to a minority following the 1920 election. In these cases, sudden changes to the established party system helped reformers to overcome Rahat and Hazan's (Reference Rahat and Hazan2011) system-level barrier.

As this analysis suggests, the First Wave of electoral reform in Canada was largely motivated by grassroots, bottom-up pressure originating at the municipal level. In response, provinces felt compelled to implement PR in districts that already used STV in municipal elections.

The importance of pressure from the municipal level is clear in the design of the urban/rural STV/AV hybrid system that was ultimately introduced in Alberta and Manitoba (and proposed in Ontario). Also evident is the provincial response to developments at the local level, including Ontario's decision to overturn the results of a municipal plebiscite that would have introduced PR in the city of Ottawa in 1916. While counterfactuals are always tricky, one cannot help but wonder what might have happened had the province not intervened. Would Toronto have followed suit? Or Kingston? It is impossible to know for certain, although Ontario's immediate response to the first and only municipal reform attempt in the province during this period surely put the brakes on reform advocacy in other cities.

Second Wave of Reform, 1950 to 1977

In contrast to the explosion of reform activity during the First Wave, only 10 reforms were attempted during the Second Wave. Eight involved reversions to plurality in the few cases where other systems existed after the end of the First Wave. The remaining two involved the introduction and subsequent repeal of the Alternative Vote in British Columbia in 1951 and 1953, respectively.

Two important trends distinguish the Second Wave from the First. In terms of the nature of the proposed alternative system, the tendency towards the restoration of plurality is clear. As Figure 8 suggests, by the end of the Second Wave in 1977, no province or municipality in Canada used an electoral system from the other family. Additionally, there is a second trend in terms of the method of reform. Of 10 attempted reforms, none was conducted via plebiscite (0% compared with 50% in the First Wave). Nine out of 10 attempts involved acts of the provincial legislature (compared with 13.6% in the First Wave). Only one attempt out of 10 occurred via municipal ordinance (versus 29.5% in the First Wave), despite the fact that 6 out of 10 attempts during this period pertained to the municipal level.

Figure 8. Methods of Reform and Outcome (Second Wave of Reform 1950–1977, All Reforms)

Our analysis of the Second Wave suggests that reform during this period was largely top-down, with limited opportunity for public input. In Manitoba, Winnipeg and the surrounding boroughs of St. Boniface, St. James, St. Vital and Transcona were unilaterally merged by the province in a 1971 move that simultaneously replaced the use of STV in those municipalities with a plurality alternative. In Alberta, Jansen (Reference Jansen1998: 225) argues that there was considerable opposition to the abolition of urban/rural STV/AV in 1956. And in British Columbia, the short-lived introduction of a variation of the AV that used multimember districts with separate ballots has been widely criticized as a self-interested attempt by the incumbent government to undermine support for the CCF (Massicotte, Reference Massicotte and Blais2008: 114). However, it was not the Liberals or the Conservatives that benefitted most from the new system, but the newcomer Social Credit party, which had not participated in the 1949 election but took 19 of 48 seats in 1952. This unexpected result helps to explain why the new AV system was quickly replaced.

The return to plurality can also be explained by the persistent barriers of political tradition and the perceived mismatch between other systems and Canadian political culture. In Alberta, for instance, Jansen (Reference Jansen1998: 226–27) shows that the Social Credit government presented the return to plurality as fulfilling a need to be consistent with other Canadian jurisdictions.

Third Wave of Reform, 2004 to 2023

The Third Wave of subnational electoral reform in Canada began in British Columbia with the 2004 Citizens’ Assembly and the subsequent referendum on STV in 2005.Footnote 16 The citizens’ assembly model heralded a new mode of public engagement, replicated in Ontario in 2006. It was a fuse that lit the flame of both broad public engagement, as the means of reform, and a move away from plurality in favour of a more proportional alternative.

Of the 13 reforms attempted during the Third Wave, 9 were conducted via plebiscite. All 9 votes proposed a switch from plurality to an other system (Figure 9). Two attempts (London Reference London2018 and Kingston 2018) occurred via municipal by-laws. These reforms were later reversed by provincial legislation, marking the only reversions to plurality during the period and the only instances in which reform occurred via provincial intervention and without public input.

Figure 9. Methods of Reform and Outcome (Third Wave)

Six of the 13 attempted reforms occurred at the provincial level, all of which were conducted via plebiscite, and all of which failed. In British Columbia (2005), this was due to the implementation of an unprecedented double supermajority requirement, which required that the proposed STV system be endorsed by 60 per cent of the valid votes cast across the province and receive a simple majority (50%+1) in at least 60 per cent of all electoral districts. The proposal met one of these supermajority requirements but not the other; while it did receive a majority in 97 per cent of electoral districts, it was endorsed province-wide by 57 per cent of voters. Thus, despite receiving majority support, it failed. An identical supermajority requirement was applied to the 2009 BC referendum on STV, which also failed.

In a clear example of diffusion, both the citizens’ assembly format and the double supermajority referendum design were also implemented in Ontario, and to similar effect, effectively establishing a new standard for Third-wave reforms.

Despite the resurgent interest in proportional representation and the revival of the plebiscite during the Third Wave, this period looked markedly different from the First Wave in several key respects. Firstly, it is worth noting that only 4 reforms (out of 13 attempts) succeeded during the Third Wave: a success rate of just 31 per cent, which pales compared to the 89 per cent success rate of the First Wave (40 out of 45 attempts) and the 100 pr cent success rate of the Second Wave.

In at least one attempt (BC 2005), this failure can be attributed to the use of a double supermajority threshold: another marked difference when compared to the simple majority requirements of the First Wave.

The citizens’ assembly format was also new to the Third Wave, providing a novel platform for public input into the process. However, despite including multiple opportunities for public input, provincial reform initiatives during this period were largely directed from the top, with the province initiating the process and then soliciting input.

Patterns and Paradoxes of Subnational Electoral Reform in Canada

One particularly noteworthy trend in the data, illustrated in Figure 10, is a sharp decline in the number of electoral reform attempts in the Second (10 attempts) and Third Waves of Reform (13) relative to the First Wave (45). A secondary trend, also evident in Figure 10, reveals a steep decline in the rate of success. While 89 per cent of First Wave reforms and 100 per cent of Second Wave reforms succeeded, that figure fell to 31 per cent in the Third Wave.

Figure 10. Reform Attempts by Time Period and Outcome

Our examination of the history of subnational electoral reform in Canada also reveals several paradoxical trends pertaining to both the nature and process of reform initiatives.

The public engagement paradox

Contrary to our initial expectations, we find that the method of reform follows a U-shaped trend in public engagement that is at odds with the prevailing narrative from the Third Wave of Reform (see Figure 11). While the citizens’ assembly model, pioneered in British Columbia in 2004, was indeed a significant innovation, broad citizen engagement was not—it had merely fallen out of favour.

Figure 11. Method of Reform by Time Period

This U-shaped pattern of public engagement is evident in Figure 11, which depicts the proportion of attempted reforms that involved a plebiscite, whether municipal or provincial (black line). It is at odds with the pattern identified by LeDuc (Reference LeDuc2003: 20–22) and Scarrow (Reference Scarrow, Cain, Dalton and Scarrow2003: 47–54), who examine the growing use of referendums and paint a long-term picture of steady, linear growth in public participation (especially via plebiscite). Our findings align better with Renwick's (2010: 251–54) expectation that electoral reforms are increasingly subject to public approval requirements in the form of referendums, and the corresponding expectation that this may, in turn, make reform attempts less likely to succeed. Hence, the procedural bias in favour of the status quo identified by Rahat and Hazan (Reference Rahat and Hazan2011). However, we disagree with the assertion that the trend toward public engagement is in any way new.

The U-shaped pattern in Figure 11 also conceals the fact that plebiscites in the Third Wave look markedly different from their First-wave counterparts. All plebiscites from the First Wave occurred at the municipal level, while a majority of Third-wave referendums (6 out of 9) occurred at the provincial level.

Looking at the older plebiscites in our dataset, most used a simple majority threshold to define the level of public support necessary to pass. However, there is a discernable trend toward the incorporation of more complex thresholds based on turnout (for example, Kingston 2018) and geography (for example, BC 2005). The political decision to abandon simple majority rules in favour of new supermajority thresholds and turnout requirements dramatically decreased the success rate of Third-wave plebiscites. If First-wave plebiscites had been held to the same standard, few if any would have passed. Similarly, if Third-wave plebiscites had been held under the same rules as the First Wave, at least three (BC 2005, Kingston 2018, and Cambridge 2018) would have passed.

Hence, the paradox. On the one hand, there is clear evidence of increased citizen involvement in the consultative phase, especially around the creation of citizens’ assemblies (BC and Ontario) or citizens’ commissions (New Brunswick) to study the issue. On the other hand, this increase of consultative input has been coupled with onerous supermajority and turnout requirements that have effectively muted the impact of citizens’ voices (BC and Ontario) by adding unprecedented procedural barriers.

This leads us to conclude that not all forms of public engagement are created equal. The recommendations of citizens’ assemblies, for example, are advisory. Similarly, plebiscites do not carry legal weight but have the power of public legitimacy. Thus, when governments do solicit direct public input, they retain control over when and how to engage, as well as whether to act on the recommendations they receive. While we agree that public engagement has become an important feature of contemporary reform attempts in Canada, leading governments to develop new and innovative methods of public input, this effect has been tempered by the corresponding invention of new barriers that make reform via plebiscite more difficult today than it was in the past.

The paradox of interests versus tradition

What happens when two barriers to reform appear to be at odds? This is the case of the second paradox, which seemingly pits the barrier of vested interests against the barrier of political tradition. In theory, the introduction of new voting systems ought to have shifted the interests of the new winners almost immediately. And yet, most of these reforms were quickly undone, many by the very actors that introduced them. We argue this is a reflection of the importance of tradition in Canadian political culture and the enduring power of plurality.

The result is a collective tendency to perceive plurality systems as the default, and is evident in the relationship between the reform process and the nature of the proposed alternative. In the data, it is clear that the degree of public engagement (plebiscite versus legislation) is strongly correlated with the nature of the proposed alternative (plurality versus other). In other words, it would appear that public consultation is more likely when the proposed alternative is not (a return to) a plurality system.

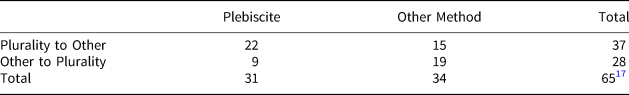

Table 3. Proposed Alternative vs. Method of Reform

Out of 31 subnational plebiscites on electoral reform in Canada, 22 (71%) have proposed the implementation of an electoral system from the other family. All occurred during the First and Third Waves of Reform. During the Second Wave, characterized by a reversion to plurality, not a single plebiscite was held.

What is particularly interesting, however, is the fact that all of the First-wave plebiscites that resulted in a return to plurality were actually framed in terms of keeping STV, with questions that asked about the continued use of PR rather than a return to plurality. Using our coding frame (Table 1), these are coded as attempts to reintroduce plurality, as that is the logical (if implied) alternative in questions that ask about the continued use of STV. However, if we take the question wording literally and consider these as plebiscites on the (continued) use of STV, there has never been a plebiscite that specifically asked about the reintroduction of plurality rule.

This raises several interesting questions. Why do governments, especially provincial governments, feel the need to gather public input when implementing other systems, but not when reverting to plurality?

In Canada, there are no special constitutional protections for plurality rule, especially at the subnational level. And yet, it is clear that attempted reforms that seek to introduce other systems have faced greater obstacles than attempts to reintroduce plurality.

We suggest that this is because plurality systems are seen by politicians and the voting public as the “default” electoral method in Canada. That would certainly be consistent with the political tradition and societal barriers identified by Rahat and Hazan (Reference Rahat and Hazan2011). But if that is the case, it apparently ignores the fact that has there been considerable variation in the implementation of plurality systems in Canada, as shown in this article.

Even if we characterize the short-lived use of other systems during the First Wave as failed experiments, this overlooks the prolonged use of other systems in cities like Calgary and Winnipeg, as well as at the provincial level in Alberta and Manitoba. The persistence of multimember plurality districts well past the end of the Second Wave of Reform also suggests that arguments by governments about the need for consistency and uniformity within and across provinces do not appear to apply within the context of plurality rules.

While it may be the case that one or two election cycles were not sufficient to entrench the other systems in municipalities that went on to repeal STV relatively quickly, expectations derived from the academic literature suggest that the extended use of alternative systems in some locations ought to have resulted in a corresponding change to the interests of the parties that won under these rules. Thus, during the Second Wave in Alberta and Manitoba, for example, the barriers of tradition and vested interests appear to have been at odds. In these cases, however, we find that tradition and societal factors ultimately trumped vested interests. This strongly suggests that some barriers to reform are more difficult to overcome than others. In the Canadian context, the importance of tradition cannot be overstated.

The paradox of the two-level game

The final paradox we observe relates to the different actors and institutions whose support is necessary for reform to occur at different levels of government. In that sense, it is clearly connected to the barrier of coalition politics identified by Rahat and Hazan (Reference Rahat and Hazan2011).

Returning to Figure 11, we observe a clear trend regarding the decline of electoral reform attempts via municipal by-laws (light blue). This may seem surprising, given the fact that Canada's urban-rural cleavage is alive and well. However, the factors driving municipal politics today do not appear to have resulted in the same social upheaval and party system realignment as evidenced in the First Wave. (Upheaval that very likely helped reformers to overcome Rahat and Hazan's (Reference Rahat and Hazan2011) societal barrier during the First Wave.)

However, we argue that there may be a second explanation for this decline, which speaks to the differences between national and subnational electoral reform. While studies of national-level reforms take for granted the fact that, in a democratic context, national parliaments have the constitutional authority to modify the system through which their members are (s)elected, this is not necessarily true of subnational governments. In the Canadian context, this is evident in the way in which provincial governments have, at different times, placed limits on municipal autonomy.

We argue the First Wave of subnational reform in Canada was made possible by the fact that municipalities in Western Canada had the authority to hold plebiscites and modify their voting systems as they saw fit. During the Second Wave, however, this authority was rescinded in places such as Manitoba. Today, some of Canada's largest cities lack the legislative authority to amend their own voting procedures. This effectively forecloses the bottom-up avenue of reform. It also accounts for the sharp decline in reform at the municipal level illustrated in Figure 11.

Provincial governments have an interest in keeping a close eye on developments in their major municipalities, as local reforms can spark demand for change at the provincial level. The result is a two-level game involving both provinces and municipalities. While a loosening of constraints and lowering of stakes at the municipal level should make electoral reform more frequent, changes to provincial legislation mean that, today, local governments in many jurisdictions lack the authority necessary to modify their own electoral rules—a power they held a century ago. This combination of the barriers of tradition and procedural bias has helped to cement the contemporary dominance of plurality as the status quo. Thus, despite a recent resurgence in public engagement when it comes to electoral reform, this increased public input has also been accompanied by additional hurdles such as supermajority thresholds and curtailed municipal autonomy.

To understand how all three paradoxes interact, consider the attempted reforms in the cities of Kingston, Cambridge and London, which together account for almost half of the 13 attempts in the Third Wave. In 2016, the Ontario government passed the Municipal Elections Modernization Act, 2016, which allowed cities the option to use ranked ballots in local elections beginning in 2018. Prior to the passage of the act, municipalities in the province were not permitted to engage in electoral reform. Indeed, our data show that no city in Ontario had done so since Ottawa's attempt was blocked by the province a century earlier.

Kingston, Cambridge and London all attempted to implement ranked ballots in 2018. In London, this was accomplished with vote of the local council, while Kingston and Cambridge held plebiscites. Unlike plebiscites from the First Wave, many of which passed by relatively narrow margins and with comparatively low voter turnout, both votes were subject to additional turnout requirements. Thus, while both proposals received majority support, the results were not binding due to low turnout (below 50%). Kingston, however, continued to push for reform. Its city council eventually voted to ratify the results of the plebiscite and implement ranked ballots for the next municipal election.

Before that could happen, however, the province reversed course, passing the Supporting Ontario's Recovery Act, 2020. In addition to a host of public health measures related to the COVID-19 pandemic, the act also changed the Municipal Elections Act, 1996, removing the option to use ranked ballots for municipal council elections. With the passage of the act, the province effectively repealed the reforms in Kingston and London without public input or consultation, and in direct opposition to local leaders who spoke out against the provincial intervention (see Lupton, Reference Lupton2020). In doing so, the provincial government argued that the use of ranked ballots was prohibitively expensive and unfair. As Ontario Premier Doug Ford explained at the time, “Well first of all, we've been voting this way since 1867. We don't need any more complications on ranked ballots and we're just gonna do the same way as we've been doing since 1867, first past the post” (quoted in Freeman, Reference Freeman2020).

These reforms raise a number of important questions that underscore the paradoxes identified here. Why the decision to implement turnout requirements for the plebiscites in Kingston and Cambridge? This was not a requirement of the Municipal Elections Modernization Act, 2016. Why the lack of public engagement around the reintroduction of plurality? And why would provinces such as Ontario and British Columbia prevent municipalities from modifying their own electoral systems, even as they attempted to engage the public on the issue at the provincial level?

We argue that the three paradoxes developed here reflect the two-level game that is inherent to subnational electoral reform in Canada. Provincial governments—particularly in the Western provinces, which experienced the brunt of pressure from urban centres to implement reform during the First Wave—then moved to insulate themselves from similar grassroots demands for change during the Second Wave of Reform. By curtailing the authority of municipalities, provincial governments had much more latitude to implement (or repeal) systems that were either beneficial or detrimental to their interests. This explains BC's short-lived use of AV, for example.

Subsequent reform attempts during the Third Wave show similar evidence of reluctance on the part of provincial governments to cede control to municipalities, suggesting that provincial governments continue to be wary of the possible consequences of vertical diffusion. This, coupled with the insistence on the use of supermajority thresholds, paints a picture of attempted reform that is largely top-down rather than bottom-up, despite renewed interest in public engagement.

Conclusions

In re-examining subnational electoral reforms in Canada, we have identified three distinct waves of electoral reform. Drawing on the larger academic literature and, in particular, on the barriers to reform identified by Rahat and Hazan (Reference Rahat and Hazan2011), we have also identified three paradoxical trends pertaining to both the nature of the proposed alternative system and the process by which reform was attempted.

The First Wave of Reform, between 1916 and 1941, was dominated by a push for the single transferable vote, especially in large, urban areas and was primarily concentrated in the Western provinces. During this period, plebiscites were the most common means of implementing reform (and undoing it). The Second Wave of Reform, from the mid-1950s to the late 1970s, undid the few remaining reforms from the First Wave. During this period, the overwhelming majority of reversions to plurality were imposed by provincial governments. A Third Wave of Reform in the 2000s saw renewed interest in proportional systems—at least at the provincial level. During this period, widespread public consultation (in the form of referendums) was once again the norm. And the advent of citizens’ assembly in BC set the bar for meaningful public engagement in reform.

Our analysis points to three interconnected paradoxes in the Canadian case. The two-level paradox suggests that although reduced constraints and lower stakes at the municipal level should encourage more frequent electoral experimentation, in fact changes to provincial legislation have left many local governments without the authority to alter their own electoral rules. We argue that this is because major municipalities have historically acted as incubators for reform movements that went on to influence the provincial level during the First Wave. By foreclosing the possibility of municipal reform, provinces have effectively prevented bottom-up reform initiatives from having a similar effect today.

The public engagement paradox reveals that although public consultation has become a key aspect of modern reform efforts, governments at both the provincial and municipal levels have introduced new obstacles that effectively dilute or impede the direct impact of majority opinion on the reform process. Thus, public engagement occurs selectively and can be used to legitimate procedural hurdles to reform.

Finally, the paradox of vested interests versus tradition reveals a significant bias in favour of plurality as the status quo. In addition, governments often employ different processes depending on the nature of the proposed change, subjecting reforms aiming to (re)introduce plurality to fewer procedural hurdles. We argue that the perception of plurality as the natural default is so deeply engrained that it is effectively able to overcome other barriers to reform such as changes to the vested interests of winners who benefit from the adoption of alternative systems. This leads us to conclude that in the Canadian context, the barriers of political tradition is among the strongest obstacle to reform.

Taken together, these paradoxical findings suggests that even as governments recognize the increased need for public engagement in the reform process (per Renwick, Reference Renwick2010), they have also devised new and selectively-applied obstacles that create a bias in favour of plurality rule.

Our findings raise several interesting questions for future research. Why has there been comparatively little interest in electoral reform in Eastern Canada? And are the paradoxes we identify unique to Canada, or are they evident in other parts of the world? We leave these important questions to future studies.

Appendix A: Coding

Electoral reform can be a complex process. Often, what we deem a formal attempt to change the electoral system may be the result of years of investigation, discussion, campaign promises and so forth. In principle, we try to avoid double-counting cases wherever possible. However, in some instances, multiple reform attempts occur in the same location within a short period of time. The table below explains how we coded some of the more ambiguous cases in the dataset.

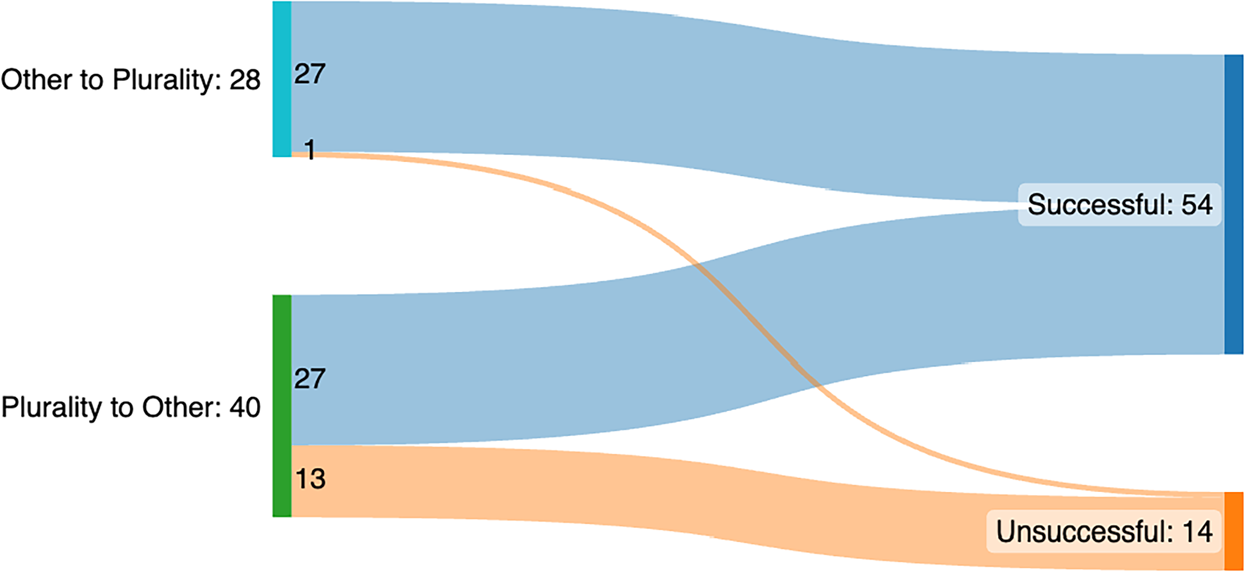

Appendix B: Observations

The table below provides a brief overview of the cases used in the preceding analysis. Each row corresponds with one observation and includes basic information on the date, location, proposal and outcome. The sources listed in the rightmost column are not exhaustive; rather, they should provide interested readers with a place to turn for further information.